Tracy Cooper-Posey's Blog

November 16, 2025

Celtic Women in Command? DNA Says They Called the Shots

We romance readers—and writers—have always known women were the real backbone of society. Now archaeology is finally catching up. This month, a tantalizing discovery in England’s Dorset region has added new weight to the idea that Iron-Age Celtic tribes might have been far more woman-centered than historians (and most fiction) have dared admit.

And I am so here for it.

The Dorset Dig that Turned HeadsArchaeologists recently unearthed a teenage girl buried near the Iron Age settlement of Winterborne Kingston. She was buried alone in a crouched position and appears to have died violently, possibly as a ritual sacrifice. (We’re not going to dwell on that. It’s awful, it happened, we’re moving on.)

What really got everyone’s attention wasn’t just her grave, but what was discovered across the whole site: dozens of skeletons, all part of a settlement linked to the Celtic Durotriges tribe.

And once scientists pulled DNA from those bones, everything changed.

Matrilocal, Matrilineal, and Maybe… Matriarchal?Let’s unpack this without the academic hand-waving.

Matrilocal means when a couple marries, the husband moves in with the wife’s family or tribe. She stays put. Her world doesn’t revolve around his.Matrilineal means inheritance or family ties are traced through the mother’s line. Your identity is shaped by your mother, not your father.Matriarchal? That’s the golden word. It means women hold the power—social, political, and economic. Think queens, priestesses, and clan heads.Now, this Dorset site doesn’t give us solid proof of full-blown matriarchy. But what it does show is that women were the anchor of the community.

DNA analysis revealed that the majority of people buried there shared the same maternal haplotype. Translation: these people were born of the same maternal line—and they stayed together. Women lived and died in the same place. Meanwhile, the Y-chromosome data (that’s the male line) was wildly diverse. Meaning? The men came from somewhere else.

Hello, matrilocality.

So, What Does This Mean for Celtic Women?It means that Iron Age women in this tribe didn’t leave their families behind when they married. The men moved in with them.

That one detail flips so many common assumptions. In most ancient societies (especially in Europe), women were “married out” to strengthen alliances or produce heirs somewhere else. They left everything they knew behind.

Not here.

In this community, women stayed rooted. Their daughters stayed, too. That creates incredibly strong kinship networks, with women at the center of daily life, family decisions, and—let’s be real—probably a whole lot of informal governance. And the men? They came in as guests. (Some likely made themselves at home. Others may have been reminded who ran the show.)

And if that doesn’t sound like the start of half the great romance plots we all love, I don’t know what does.

Why This is Such a Big DealThis isn’t just a quaint tribal quirk. This kind of female-centered structure is rare in prehistoric Europe. Patrilocal and patrilineal systems (where women marry out and men hold power) were the norm across most of the ancient world.

To find solid, DNA-confirmed evidence of a society where women didn’t just survive but held their ground—literally—is like finding a matriarchal unicorn.

Even the researchers were surprised. One called it “an unusual but robustly supported case.” Which in science-speak means: “We didn’t expect this, but the data slapped us in the face.”

Your Favorite Celtic Heroines? They Were Closer to the Truth Than We Thought

Your Favorite Celtic Heroines? They Were Closer to the Truth Than We ThoughtIf you’ve been reading the Once and Future Hearts series (and judging by the emails I get, many of you have), then you know I’ve always leaned into the idea that Celtic women were fierce, powerful, and far more central to society than the Roman chroniclers liked to admit.

Turns out, I might’ve been too cautious.

I reined in the matriarchal elements to stay within the boundaries of what historians “allowed.” But now? Now we have genomic receipts. Women weren’t just the fierce battle queens or tragic sacrifices. They were the glue holding everything together. The land belonged to them. The family was theirs. And the men—bless them—were often just trying to find their place in the women’s world.

What This Means for StorytellingFrom a writer’s perspective, this changes everything. It gives us permission to reimagine Iron-Age Britain not just with strong female characters, but with entire systems built around women’s roles, power, and presence.

Imagine a heroine who doesn’t have to “fight for her place in a man’s world” because the world is already hers.

Imagine her dealing with incoming husbands (plural?), property disputes among sisters, or external threats from patriarchal neighbors who don’t understand that “she” isn’t just a girl—she’s the whole damn foundation.

The story possibilities explode.

One Last Caveat (Because You Know I Love Those)This doesn’t mean every Celtic tribe was matrilocal. Or that all women had equal power. Even in this female-centered structure, violence against women still happened—like our tragic teenage girl in Dorset.

But it does mean that the default assumption of male-dominated societies needs to be reexamined. It gives us a new lens to see the past—and our heroines—in sharper, stronger relief.

Final ThoughtSo the next time someone tries to tell you Celtic women were just mythic exceptions—warrior queens, noble sacrifices, or tragic love interests—you can point to Dorset and say, “Actually, they were the rule.”

And you’ve got the science to back it up.

Now available for preorder:

The Grail and Glory

Latest releases:

Breaking Point

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

October 26, 2025

Claddagh Rings and Older Symbols

Once upon a time — actually, back in 2011 — I wrote a post about Claddagh rings as part of a book tour for Blood Knot. That post has since vanished into the digital void, possibly dragged down by dead image links and too many steamy references from an era when Ellora’s Cave still roamed the earth.

The “traditional” modern Claddagh ring. But variations on this range from even more simple, to wildly elaborate.

The “traditional” modern Claddagh ring. But variations on this range from even more simple, to wildly elaborate.The ring I wrote about then even made the cover of the first edition. (Let’s just say that version of the cover is now extremely NSFW, and leave it at that.) The Claddagh ring is no longer part of the design, but its symbolism still sits at the heart of that story — and it deserves a bit of a resurrection here on the blog.

Because Claddagh rings? They’re fascinating. Not just pretty tokens of Celtic pride or sentimental knickknacks picked up on a trip to Ireland. These rings are old, complicated, and steeped in stories — both historical and wildly speculative. The latter is where I come in.

But let’s start with the facts.

A Heart, Two Hands, and a CrownIf you’ve ever seen a Claddagh ring, you’ll recognize the parts: a heart held by two hands, topped with a crown. Love, friendship, loyalty — in that order. The three essential ingredients of a healthy relationship, though not necessarily a chronological checklist. Some of us meet loyalty before love. Some find friendship after marriage. Some are still looking.

The way the ring is worn is supposed to signal your relationship status to the world, which was very handy before dating apps and Instagram overshares.

Traditionally:

Right hand, heart pointing away from you: single.Right hand, heart pointing toward you: spoken for.Left hand, heart out: engaged.Left hand, heart in: married.Of course, that’s the theory. In practice, people wear it however they like — or however it fits that day. There’s also the added complication of global interpretations and variations, especially now that Claddagh rings are worn all over the world. But the general idea still holds: love, friendship, loyalty. In whatever order works for you.

My mother-in-law is half-Irish on her mother’s side; she wears a gold Claddagh ring as both a wedding and engagement ring…but the way she wears it (heart up, heart down) varies. I’ve seen her wearing it both ways. So for her, the position of the heart doesn’t matter. And that’s the beauty of these rings. They mean what you want them to mean.

The Curious History of the Claddagh

The Curious History of the CladdaghYou’d be forgiven for assuming Claddagh rings are ancient, possibly passed down from bronze-clad druids or flung into the bog with offerings to the gods. In fact, the design we recognize today doesn’t show up until the early 1700s — relatively recent, as far as historical jewellery goes.

The name “Claddagh” itself wasn’t even used until the mid-1800s, and it’s named after a small fishing village just outside Galway, which has now been absorbed by the city but was once its own distinct little enclave. A place of boats and nets and tight-knit traditions, the kind of place where a handmade ring could quietly become a symbol for generations.

There’s a romantic (and possibly true) story about a man named Richard Joyce; captured by pirates, sold into slavery, trained as a goldsmith in North Africa, and eventually returned to Galway, where he crafted the first Claddagh ring for the sweetheart who had waited faithfully for him. That tale has everything: swashbuckling, love, captivity, artistic genius, and an Irishman beating the odds. No wonder it stuck.

But like most origin stories, it’s probably too perfect to be entirely factual. Historians have found early rings with Joyce’s maker’s mark, but also others from the same time made by different goldsmiths. The truth is likely messier — and therefore, more interesting.

Whoever created the Claddagh ring wasn’t working in a vacuum, either.

Even Older Symbols: The Roman ConnectionLong before Claddagh rings, there were fede rings. These were Roman in origin, and the name comes from the Italian mani in fede — “hands in faith.” They featured two hands clasped together, a symbol of trust, faith, and plighted troth. (That’s an old-fashioned way of saying “I promise you my heart,” not a typo.)

The Claddagh ring took that visual and added an Irish twist: a heart between the hands, and a crown atop the heart. It layered meaning upon meaning, turned a universal gesture into a localized message.

It’s entirely possible the creator of the Claddagh ring saw a fede ring — or its echo — and adapted it. Or maybe they were just Irish enough to think, “This needs more symbolism and possibly a crown.”

When I discovered this Roman connection to Claddagh rings, when I was researching Blood Knot, I leapt upon it. Nail is Roman to the core, and Sebastian is Irish…I knew that if I didn’t use a Claddagh ring somewhere in the book, I was missing a huge symbolic connector….

In reality, if Claddagh rings are an echo of the Roman fede rings, or not, the bones of the design go back much further than Galway. Which brings me to…

The Fictional TurnIn Blood Knot, I took full advantage of this historical murkiness and handed the ring’s creation to a shadowy Irish father with a gift for emotionally resonant jewellery. Was it historically accurate? Not even a little. But it made a great story, and the ring became a powerful symbol throughout the novel — not just as a romantic token, but as a touchstone for memory, grief, and connection across time.

That’s what old symbols do best. They carry more than their surface meanings. They remember things we’ve forgotten. They tie us to people we’ve never met. Sometimes they haunt us, sometimes they heal.

Even if they no longer make it onto the cover of the book.

Why We Still Wear ThemCladdagh rings are still given and worn today — not just in Ireland, not just by the Irish diaspora, but by people who respond to what the ring means. Sometimes it’s a promise. Sometimes it’s a reminder. Sometimes it’s just beautiful, and that’s enough.

There are modern versions in titanium and tungsten, adorned with gemstones or etched with Celtic knotwork. They’re given as engagement rings, or friendship rings, or family heirlooms. Some are passed down through generations. Others are picked up in a gift shop and loved into legend.

That’s the magic of symbols. We give them meaning, and somehow, they give something back.

A Quick PS, Because Someone Will Ask…If a woman is already wearing a Claddagh ring in the “engaged” position — left hand, heart facing out — what happens during the wedding ceremony? Does the groom take the ring off and turn it? Does she do it herself?

There’s no single answer, but the most romantic version is this: during the ring exchange, the groom gently removes her Claddagh ring, turns the heart inward, and slides it back on — symbolizing that her heart is now fully given.

In other versions, the bride turns it herself after the ceremony as a quiet, personal gesture. I really like this idea: The woman is controlling her own destiny and making her own decisions about claimed/unclaimed etc.

Some couples choose new wedding bands, and the Claddagh is worn elsewhere or retired. Others keep it as the ring, and the turning becomes part of the ceremony. There’s no hard rule — just story potential.

And yes — men absolutely wear Claddagh rings too. In fact, they were originally more common as men’s rings in Ireland, often passed from father to son. These days they’re worn by men as engagement or wedding bands, heritage pieces, or simply for the meaning. The design might be chunkier or more stylized, but the message — love, loyalty, friendship — stays the same.

Now available for preorder:

The Grail and Glory

Latest releases:

Breaking Point

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

October 19, 2025

Sybil Ludington: Teenage Girl vs. the British Empire (Sort Of)

You know how sometimes, you read about some long-lost woman from history and you find yourself thinking, “How in the name of history class did I never hear about her?” That was me when I first stumbled across Sybil Ludington—allegedly the teenage girl who rode further than Paul Revere to save a town from the British during the American Revolution.

I say “allegedly” because her story (like King Arthur’s) is one of those wonderfully murky ones that historians love to squabble over. Which, of course, only makes it more interesting.

So let’s go back to 1777. Sixteen-year-old Sybil—who, frankly, already had enough on her plate as the eldest of twelve kids—was the daughter of Colonel Henry Ludington, a militia commander in New York. One rainy April night, a messenger thundered up to their farm with news: British troops had attacked Danbury, Connecticut, burning supplies and generally doing their British thing. The local militia needed rallying, and fast.

Enter Sybil.

Or so the story goes.

Her father, tied up with his duties and possibly overwhelmed by the logistics of managing 400 scattered militiamen, is said to have turned to his teenage daughter and asked her to ride out and summon the troops. And she did—covering roughly 40 miles through dark, muddy countryside, knocking on doors, rousing farmers, and yelling warnings. One version even has her fending off a highwayman with a stick. In the pouring rain. At night. On horseback.

Which makes Paul Revere’s much-celebrated 12-mile jog look a bit… small, doesn’t it?

The trouble is, we don’t really know if it happened.

The first written account of her legendary ride didn’t show up until over a hundred years later—in a memoir published by her grandchildren, no less, who may have been just a smidge enthusiastic in polishing the family legend. The newspapers of the time? Silent. Military records? Nada. It wasn’t until the early 20th century that Sybil’s story started getting airtime, and it blossomed beautifully during the patriotic nostalgia fest that was the American Bicentennial.

But even if the finer details are fuzzy (or invented), there’s still something deliciously powerful about the image: a girl on a horse, alone in the dark, trying to rally an army. Whether the ride happened exactly as described—or was closer to a local dash between farms—doesn’t change the fact that Sybil was real, the war was real, and the need for women and girls to step up in times of crisis was very, very real.

And it makes you wonder how many other Sybils are tucked away in the footnotes of history. Girls and women who did what needed to be done—not for glory, but because it had to be done. And then they got up the next day and made breakfast for twelve siblings.

Sybil Ludington lived a full life after the war. She married, had a child, and quietly faded into the background—until the 1900s rolled around and her descendants reminded the world of the girl who may or may not have saved a town one rainy night.

Was she a patriot on horseback or a family legend that galloped into myth? Maybe a bit of both.

And honestly, I think she’d be fine with that.

Now available for preorder:

The Grail and Glory

Latest releases:

Breaking Point

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

October 5, 2025

Mary Anning: She Sells Sea Shells… and Revolutionized Science

An interpretation of the real Mary Anning.

An interpretation of the real Mary Anning.A few weeks ago, I mentioned Grace O’Malley — pirate, politician, and woman with more guts than a cannon broadside. The response was immediate and loud: more forgotten women, please!

So here we go.

Let me introduce you to Mary Anning, a woman you’ve probably never heard of — unless you’re a geologist, a fossil nerd, or possibly British. Which is a shame, because Mary helped build the entire field of paleontology… and got nearly zero credit for it during her lifetime. Of course she didn’t. She was poor. She was a woman. And worst of all, she was right.

The Girl on the CliffsMary was born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, a damp little seaside town on England’s Jurassic Coast. You know the rhyme “She sells seashells by the seashore”? That’s probably about her, although no one can say for sure. What we do know is that Mary and her brother were combing those seashores for more than just shells — they were hunting fossils.

And not the “oh look, a trilobite” kind, either.

When she was just twelve, Mary dug out the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton — a marine reptile that looked like a cross between a dolphin and a sea monster. It was longer than a horse and a good deal toothier. The experts at the time thought it was a deformed crocodile. Mary, of course, knew better.

She kept digging. And finding. And digging some more.

The Dragon Lady of DorsetBy the time she was in her twenties, Mary had pulled plesiosaurs out of the cliffs (think Loch Ness Monster, but real), and even a pterosaur, the first one ever found outside Germany. That’s a flying reptile, by the way. Not a dinosaur, technically — I’ve learned to make that distinction or risk the wrath of dinosaur enthusiasts everywhere.

And here’s where the story starts to twist.

Despite her discoveries, Mary wasn’t allowed into scientific societies. She wasn’t given credit in journals. The fossils she unearthed? Named, classified, and written up by men — men who’d often bought them from her or, in some cases, just heard about them. She did the work. They got the glory.

Even worse? Many of them knew she was brilliant. They consulted her. Quoted her in letters. Sometimes even admitted she knew more about fossil anatomy than they did. But still, she was “just” a woman. A shopkeeper’s daughter. Someone who sold fossils to tourists when she needed bread money.

Sound familiar?

From Invisible to Immortal (Almost)Mary died at 47, still poor, still mostly unrecognized. It wasn’t until years after her death that the scientific community started muttering “Oops…” and giving her the credit she deserved.

These days, her name’s on museum plaques, and her likeness is on statues — finally. There’s a movie about her (sort of — they took dramatic liberties, as movies do). She’s become a quiet icon for women in science, particularly the ones who don’t get invited to the keynote talks or the cover of Nature.

But here’s the part I keep coming back to: she didn’t do it for the fame. She couldn’t. Fame wasn’t an option. She did it because she loved it. Because the cliff called to her. Because she wanted to understand the bones in the rocks.

And isn’t that kind of fire the thing we admire most?

So Why Tell Her Story Now?Because you asked for more posts like this. Because I’m elbow-deep in historical rabbit holes anyway. And because Mary Anning is exactly the kind of woman I love reading and writing about — smart, driven, passionate, and conveniently overlooked by the official record.

There’s something satisfying about digging up these stories. Almost like hunting fossils. Except instead of bones, it’s truth we’re pulling out of the rock.

Shall we keep going?

Now available for preorder:

Breaking Point

Latest releases:

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

Captain Santiago and the Sky Dome Waitress (  Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

September 28, 2025

What’s on Tracy’s Desk? (2025 Edition)

A truly inspiring home office. If only….

A truly inspiring home office. If only….Waaaay back in 2011, I did a guest post on Alternative Read, where I revealed my desk and what is on it and around it. It was a super-popular post, and I linked to it from my blog, here.

That was what my desk looked like then. That was April 2011, and I had been 100% indie for less than a month.

If you check the photos out carefully, you’ll spot a land-line phone on my desk (that’s gone now), and only one monitor. Also the CPU was sitting on my desk, instead of beside it.

I’m still writing at that desk. But things look a bit different now.

In particular, the mournful note in the original post, asking where are Merry, Pippin and Strider? struck me as ironic, as Merry and Pippin have both gone now (along with Sam, who was a ball python). Only Strider is left, and you’ve met him before. But hold on a moment.

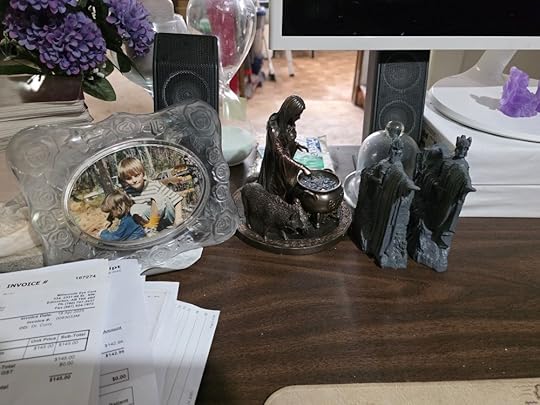

Here’s how my desk looks today;

This is the whole desk area. Not terribly glamorous, is it? A staged and pristine influencer

True story: I asked MidJourney to create images of a “fantasy author’s office that would inspire story-writing” and what MJ came up with was just as cluttered and chaotic as mine (and just as dusty):

MJ’s version of an “inspiring author’s office”

MJ’s version of an “inspiring author’s office”Going back to my office;

This is a closer shot of the desk itself. (With Strider sniffing around, wondering what I’m doing — I just noticed him in the bottom corner!)

My monitors have super-prosaic stands: Photocopy paper. Which is another irony, because we never print anything anymore, so I’ve had the same stack of printer paper under the monitors for years. My son Terry got so sick of seeing them, that he bought me a proper double-monitor stand that means I can remove the legs. I just haven’t got around to installing it. (Time, time time!!)

Note under the main monitor are my two purple happy Buddhas. They’re supposed to bring luck and fortune.

Just to the left of them are my Argonath (“Pillars of Kings”) from the Lord of the Rings movie.

In closer detail.

The glass picture frame holds a picture of my son and daughter taken in the bush outside of Perth, Western Australia, only a few weeks before we moved to Canada, in 1996. Both kids are taller than me now.

Also among the keepsakes is this statuette of Cerridwen, that my daughter gave to me. Ceridwen is the Celtic goddess and muse of creatives.

I wrote a litany that calls to Cerridwen that I sometimes cite when I’m about to start writing for the day:

O Divine Cerridwen

Goddess protector of poets,

Sustain for me

This song of the various-minded man.

Make the tale live for us

In all its many bearings,

O Muse.

It’s based upon a much more ancient prayer to gods and muses — and I can’t remember which one.

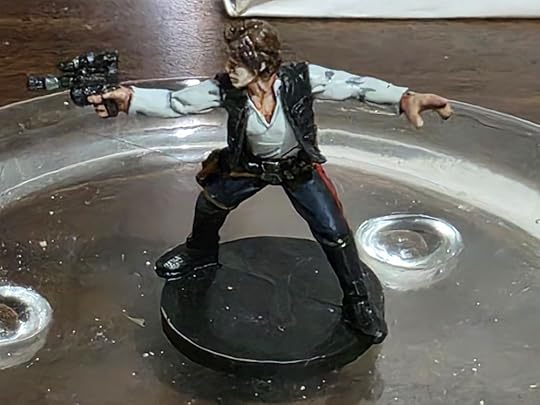

The image on the right shows my teeny tiny Han Solo figure, under a bell jar.

My son hand painted him and gave him to me for Christmas one year.

Han Solo was one of the major inspirations that got me into writing fiction — particularly romance novels.

Here he is in detail.

Below is a jar holding about a pound of beach sand and sea shells that I picked up off the beach the last time I was in Australia. On the right inside the jar is a cuttlefish bone.

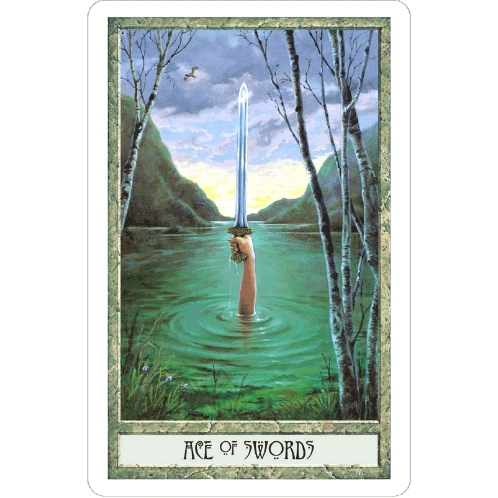

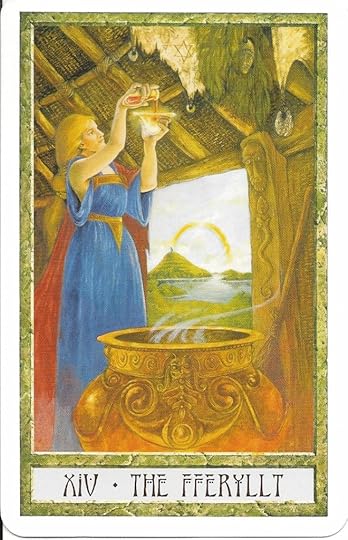

Sitting on top of the jar, just inside the frame of the photo, are my Tarot cards. Just like the original post, I have Tarot cards still. But I’ve moved on from the original Ryder-Waite-Smith deck. When you first start working with Tarot cards, you’re encouraged to “try on” different decks, to see which ones appeal to you, or speak to you.

I hunted around for many years, looking for a deck that “clicked” with me. I felt very comfortable with the Ryder-Waite-Smith deck (the traditional deck) that you can see in the photos from 2011.

Then I found the Druid Craft Tarot deck, and fell in love. Just look at these two cards:

The classic image of Excalibur being returned to the Lady of the Lake….

Cerridwen again!  And through the door is Glastonbury Tor…reputedly, Avalon.

And through the door is Glastonbury Tor…reputedly, Avalon.

Can you see why I grabbed this deck and hung onto it?

And I would be remiss to not include the other tool/desk decoration/distraction that sometimes invades my desk:

Strider got in front of the camera as I was taking photos, almost demanding I take one of him. Then he wouldn’t stay still while I tried to take it! This is the best shot of all of them, and it’s still a bit blurry.

My second desk.I would be remiss if I didn’t include my second desk. It’s where I’m writing this post at the moment:

As you likely know already, Multiple Myeloma ate away four of my vertebrae before they figured out I had cancer (it also destroyed nine ribs). So for the longest time, I lived in this chair. I even slept in it, when it hurt too much to lie down.

The vertebrae have probably fused back together again now (it’s been a while since they were x-rayed), although I’m also four inches shorter than I used to be, too. Despite the spine no longer being fragile, the muscles still have to learn how to deal with my altered structure, and how to work again (I’ve been on the low end of active for years now). So even sitting at a desk with a high-tech chair leaves my back screaming after a few hours, and I have to head upstairs to the recliner to work.

The recliner stops the pain dead. It can take a few minutes, but the total support the recliner gives me takes away the pain and lets me avoid painkillers.

The recliner was only ever meant to be a temporary solution while I recovered (hence the extension cords and the mobile trolley). But that temporary phase is now into year…four.

For the longest time, this was the only place I could work. But now, bit by bit, I’m able to stay sitting at the desk for longer periods.

So there you go. That’s what my desk looks like, fourteen years later.

Now available for preorder:

Breaking Point

Latest releases:

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

Captain Santiago and the Sky Dome Waitress (  Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

September 21, 2025

Grace O’Malley: Ireland’s Pirate Queen Who Refused to Stay in Her Lane

Some women in history slip quietly between the pages. Others take a dagger to the margins and carve themselves a space. Grace O’Malley—known in Gaelic as Gráinne Mhaol—was absolutely the second kind.

She ruled the waves off the west coast of Ireland at a time when women were meant to embroider cushions, not command warships. She was born into a world that expected her to marry well, produce heirs, and fade dutifully into the background. Instead, she built a pirate empire, challenged a queen, and outlasted the men sent to break her.

A Queen of Clans, Not CourtsGrace was born around 1530 into the powerful O’Malley clan, lords of the sea who dominated trade and piracy along the Irish coast. When her father died, she didn’t wait for anyone to hand her a title. She claimed leadership of the clan, learned the intricate dance of alliances and betrayals, and became a political force in a world where women were often used as pawns—but rarely seen as players.

Twice married, she strategically leveraged both unions to amass ships, castles, and influence. One husband died (she kept the fleet), the other she divorced (she kept the castle). Somehow, she also kept his loyalty. Grace had a habit of rewriting the rules.

Of Babies and BlunderbussesHer legend is as wild as the Atlantic she ruled. One story goes that just a day after giving birth on board her ship, she leapt up—bedraggled, bloodied, and furious—to repel a Turkish pirate attack with pistols in both hands. Honestly, I’ve had bad hair days that were more debilitating.

This is a woman who gave no quarter. At the height of her power, she commanded hundreds of men and dozens of ships, collecting “tolls” from any vessel daring to pass her stronghold at Clew Bay.

Crossing Swords With Elizabeth IBut if you think her biggest threat came from rival pirates or stormy seas, think again. Enter stage left: Queen Elizabeth I of England.

Two women. Two power centers. One very inconvenient ocean between them.

Elizabeth sought to tighten her grip on Ireland. Grace wasn’t having it. While English fleets clashed with O’Malley’s ships in guerrilla-style sea skirmishes, it was Governor Richard Bingham who truly brought the hammer down. He killed one of her sons, imprisoned another, and seized her lands and strongholds.

What did Grace do? She didn’t write angry letters or retreat into obscurity. She sailed straight into the lioness’s den.

The Pirate Queen Meets the Virgin QueenIn 1593, Grace requested an audience with Queen Elizabeth herself. The two women—both hardened leaders in their own right—met at Greenwich Palace. The details are gloriously murky: Grace supposedly refused to bow, possibly carried a dagger, and definitely refused Elizabeth’s offer of noble titles on the grounds that equals don’t confer titles on each other.

What’s not murky? She walked away with the release of her son, restoration of her lands, and a nod of reluctant respect from one of the most powerful monarchs in history.

Why Grace O’Malley Still MattersGrace O’Malley wasn’t an anomaly. She was proof that women were always capable of power, strategy, leadership—and more importantly, the audacity to claim it.

She died in 1603, the same year as Elizabeth I. A fitting bookend for two women who defined their eras in very different ways.

History tends to file women like Grace under “colorful side characters” or “folk legend,” when really, she was the main event. She didn’t wait for history to hand her a role—she wrote herself into it, daggers drawn and sails high.

Now available for preorder:

Breaking Point

Latest releases:

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

Captain Santiago and the Sky Dome Waitress (  Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

September 14, 2025

The Truth About Writers’ Lives (It’s Not What You Think)

I really wish my writing life looked like this. Even just every now and then….

I really wish my writing life looked like this. Even just every now and then….I had an interesting conversation with my mother recently.

Scratch that.

I’ve had this conversation with my mother more than a few times, in various ways and forms.

But generally, the conversation goes:

Mum: “What did you do today?”

Me: “Oh, I wrote, worked on the magazine and on my business.”

Mum: “Nothing else?”

Me: “That was the whole day.”

Mum: “That sounds…boring.”

Note: She doesn’t always say boring, but the word or tone she uses implies “I would die if my days were like yours.” She can make “interesting” sound like the world is about to implode from lack of leisure. “Oh, that’s…interesting.”

Actually, this makes my mother sound judgmental. She is anything but that. The problem is, I figured out, there is a huge mismatch between what she thinks a writer does and what a writer actually does.

Even though she knows me.

It occurs to me that you might also think that a writer’s life is glamourous and adventure-filled. After all, we must experience everything that we put into our novels, right?

Side note (but not really): For several years I wrote ultra-spicy erotic romance for a now long-gone publisher who dictated the amount and type of sex we had to put into our novels, including at least one explicit sex scene before the 10% mark of the story. And for many years after, I continued to include a great deal of (somewhat toned-down) sex scenes in my romances. Guess what the most common question was I got from (sadly, mostly male) readers about my life? Yep. “So, you do all your own research for these scenes, right?”

It’s not just my mother who has a skewed view of what a writer does with their days. Most non-writers don’t have writer friends and therefore form their impressions about how a writer lives their days from TV and movies, from hints in the novels they read. (For instance, Stephen King has a lot of writer characters in his novels, and you might think you’re getting a glimpse of how writers typically live from those novels. You’re not. Trust me.)

If my mother, who has an insider’s viewpoint on how a writer lives, still thinks that I’m not living the proper writer’s life, then readers who do not know any writers at all are just as likely to have wildly incorrect ideas about how a writer lives.

So why should you care about how writers really live?The myth of the writer’s life is attractive. It looks glamorous. Lots of royalties, book launch parties, book tours around the world, interviews and TV show appearances.

Then there’s the research trips. Six months in Peru. A year in Europe, with three months living in the Latin Quarter in Paris, and dining at salons each evening.

Plus, a writer is surrounded by interesting people. Their friends are Names. The parties they throw are legendary. They ski in Switzerland and water ski in the Caribbean.

Are your eyes rolling yet?

Yes, I’ve exaggerated just a tad. But even a slightly more modest version of that life might still be stuck in your mind, because you are exposed to so many badly exaggerated and unrealistic versions of how writers live, that it seeps in and settles in the back of your brain.

So, who cares what you think?Well, I do. That’s why I’m writing this post.

And it isn’t just because I want you to know The Truth About Writers.

Sometimes, the erroneous beliefs you have about writers and their lives can actually hurt writers.

Huh, you say?

Here’s an example. A true one, as it happens. When our kids were still in school, the schools at the time charged parents a “lunch fee” that was supposed to offset the costs of supervising our children during the lunch break.

Families who were struggling financially could be excused from the fees, and as we had only one adult working at the time (me), we applied and were exempted from paying.

Then, six months later, we got a bill in the mail for six months’ worth of fees, plus interest, processing fees, and a fee that I think was simply there because they wanted to make us pay for lying to them about our financial situation. The bottom line was more than double what the fees alone should have been. We had three days to pay it or it would be handed off to a collection agency.

When I contacted the school to ask, “what the hell?” in the politest terms I could manage, the response was: “Well, you published a book. We saw it on Amazon. You can pay the fees and it’s dishonest of you to say you can’t.”

I’ve already told you about the most frequent questions I got (and still sometimes get) from non-writers about the spicy content of my novels. I sometimes wish I had the moxy to answer “Well, of course I research everything! I have to keep it toned down for the novels, though….”

Here are more examples.Overcharging Based on Assumed WealthA writer books a home repair or renovation, and the contractor “just assumes” they’re loaded because they’ve published books. Quotes come back mysteriously higher than expected, sometimes with jokes like, “Well, you’ve got bestsellers, right?” Real result: inflated quotes, or worse, refusal to negotiate or offer standard rates.

True story: We arranged a deal with neighbours of ours who work in the roofing industry to replace our shingles. One of them, during a break, laughed and said they should probably be using $100 notes instead of shingles. Us being writers and all….

Expecting Free Work — or Exposure as PaymentExample: Friends or acquaintances assume that because the writer’s “made it,” they should be willing to write blurbs, bios, speeches, or entire articles for free — “It’s just writing, after all.” Often, this comes with: “It’ll be great exposure!” (As if exposure pays the power bill.) Also, readers expect free books. Always.

True story: I was showing my author copy of one of my books to the family at a dinner. My sister-in-law tucked the book into her handbag. “Well, you’ve got more, right?”

Another true story: The exposure thing is huge. What’s even more insidious is that now many literary magazines charge the author just to submit their work. Because the magazine feels they shouldn’t have to bear the costs of reading stories submitted by authors. And no, they don’t pay the author to publish the work.

Guilt-Tripped for Not Donating Books or TimeSchools, libraries, and community organizations ask for free books “because you’re a published author and you can afford it.” If the author says no (or asks for a discount rate), they’re seen as stingy — when in truth, each free book is a cost to them.

True story: For indie authors (of which I am one), there is no publisher who sends a carton of paperbacks to the author. I’m not sure that traditional publishers do this anymore, either. But the only way I can get my indie published books into my local library is to donate the copies. They refuse to buy them. And they will only take hardcover editions, which I can “write off as a tax deduction.”

Assumptions at Tax TimeAccountants or even friends think the author’s downplaying their income when they say they made under $20,000. “Come on, but you’ve got all those books!”

True story: The Canadian Revenue Agency questions the legitimacy of a writing career when the income is low — which is deeply ironic. If the CRA considers you’re “not really a writer” you can’t claim any tax deductions for expenses and the costs of publishing.

The endless leisure hoursI’ve saved this one for last, because it’s the one that baffles me the most. The belief seeps through conversations and comments from friends and family, readers, strangers and the media.

The belief seems to be that writers spend their days making up stories, and in between, lolling around dreaming up stories or having adventures they can use to fill the pages of their novels.

Stated baldly, like that, it sounds ridiculous. But the myth persists, anyway.

Here’s the mathThis is where the myth falls apart.

The rate at which a writer writes can vary wildly. Some writers can only get 200 words an hour written, while others have trained themselves to get 2,000 words an hour down.

So, let’s go with a very average 1,000 words an hour (and I know plenty of writers who would turn pale, if they were expected to write at that rate).

The average novel is around 80,000 words.

So that’s 80 hours just to write the first draft of the novel.

Most writers (including me) have secondary and tertiary revenue streams they have to take care of. Day jobs, side jobs, side gigs, contract work, teaching, lecturing, non-fiction writing. There are a lot of ways writers work to pay the bills. But that takes time. So, let’s say that the average author can spend two hours a day, seven days a week, on their novels.

I’m closer to three hours a day, but that’s only because I’m so bloody-minded about getting the novels done, that I will sacrifice just about anything else first, except sleep.

80 hours stretched across two hours a day means 40 days to write the first draft of the novel. Presuming that nothing knocks the writer off their daily schedule and they faithfully write every single day.

But before the first draft gets written, the book must be researched, the concept built, and the book must be plotted.

Yes, some writers don’t plot. They write by the seat of their pants. But their per-hour writing rate is lower, right out of the gate. So, drop their hourly rate down to around 750 words/hour.

Once the first draft is written, the book must be “cleaned up” — for me, this is a multi-hour process with an 80-point checklist I must work though, tackling weaknesses in the prose.

This happens before I hand off to an editor.

If the book has structural flaws I have to clean them up first.

So, let’s add a meagre 10 days to plot the book and five days to clean it up. If the writer is a “seat of the pants” writer who doesn’t plot, the clean up time should be doubled or tripled.

Another true story: Dictating – text-to-speech—sounds like a no-brainer that every writer in the world should adopt. As I explained here, by the time I clean up the mess that dictated prose leaves behind, it ends up that I write faster with just a keyboard.

That’s 95 days to create a manuscript that is ready to be edited.

The editor does their bit, and the manuscript comes back to the writer. Cleaning up the edited manuscript can take anywhere from hours to days (and sometimes, weeks).

Let’s say one week, at 2 hours per day of writing time. That’s modest.

We’re up to 102 days to a completed novel.

Then the author must either start submitting to agents and publishers, or else self-publish.

I won’t calculate how long that process takes, because it varies too much and that isn’t the point I’m trying to make with this math. Both types of post-writing processes take weeks.

Writing takes time.The point I’m trying to make is that writing takes time.

A writer who is dedicated to finishing a book must find the time to write it. Usually, that means giving up some other activities. Social events, parties, watching TV, doom scrolling, exercise (often!), sleep (not advised, but writers still try it). All of them go out the window if a writer really wants to finish a book.

How we get books written is by structuring our days and making them as boring as possible. The same day, day in and day out. This minimizes the stress of having to deal with unusual and “interesting” events and saves our executive brain processing budget for the writing of scenes.

Boring is good. But there still isn’t enough time to write. Ever.

And I can just hear someone out there saying, “Well, if you want to finish a book, just spend more time each day writing it.”

Which seems to make sense.

My scheduleAnd here is where we reach the point that got me to write this post in the first place.

Here’s an average day for me:

4:30 am: Get up, breakfast, quick round of emails to put out any fires, answer anyone screaming at me.

6:00 am: Down to my desk, a few pre-writing tasks, then into writing fiction.

9:00 am: Make myself stop writing fiction and turn to my side gig that pays most of the bills: I’m the managing editor of two magazines and their associated sites and newsletters.

I’m fortunate that the cook in our household is not me. So, lunch is gobbled down at the kitchen counter, and I get back to my desk.

2:00 pm: Stop working on the magazines and switch over to the “everything else” of my fiction writing business: cleaning up manuscripts, marketing, writing emails and blog posts, social media, formatting books, organizing covers, coordinating editing. There are a lot of moving parts. Just writing blog posts and emails takes up to two hours each day.

Dinner: Also gobbled down at the counter. I’ll sometimes stop to do the dishes, but I often ask my daughter to do them instead.

After dinner I transfer to the recliner and work on my laptop, while Mark watches TV. I sort-of watch from the corner of my eye, but if the work I’m doing requires anything other than superficial thought, I have to focus on the laptop instead.

8:00 to 8:30 pm: Stop working. Stretch. Go to bed.

+++++++++

This is every day of the week, including weekends and public holidays. Yes, that’s a 14-hour day. Every day.

And notice that working out and healthy things like taking time to walk or meditate and any sort of cleaning and general house maintenance are not on there.

And here’s why I’m writing the post. Friends of ours emailed us this morning and said, “Hey, we’re in town on Saturday. We’ll stop by for coffee mid-morning. Can’t wait to see you! It’s been so long!”

That email has completely derailed my schedule, because someone has to clean the house before our guests arrive.

I’m facing a familiar decision. Do I cut down the fiction writing time in order to squeeze in the cleaning?

And yes, I had to give up writing time to get the cleaning onto the schedule (which sounds all formal and corporate-speak, but honestly, without my calendar and my task manager, my entire life would implode because I forgot to do something small, invisible to everyone else, easily overlooked, but critical to keeping my life on the rails.)

The daily workouts, cleaning and gardening that are NOT on my schedule? I keep trying to find the time to do them but cannot bring myself to give up even more fiction writing.

Usually, I do what I will be doing this weekend: I clear decks, and temporarily off-load fiction writing and as much of my formal, contractual obligations as I can, and use that time to take care of cleaning, gardening, maintenance or simply to have time off because I need a break.

So no, just “spend more time writing each day” isn’t possible. I’m fighting tooth and nail to keep the hours I have.

The Real Writer’s LifeI’ve spoken to enough writers to know that I am not unusual. This maxed out life is the reality.

Burnout is a real thing for many writers these days.

The endless leisure hours to think up stories? That happens in the shower, sometimes. Or when I’m falling asleep at night.

The research trips? Parties? The Parisian bohemian lifestyle? Myths. They always have been.

Even Hemingway, whom non-writers seem to feel spent his life in Parisian cafés or hunting ivory in Africa, or fishing off the Florida coast, actually had a rigorous writing schedule that included taking the phone off the hook and ignoring everyone. True fact: He built one of the first standing desk. (I believe Churchill liked to work standing up, too, so he might be the first.)

J.K. Rowling checked into remote Scottish hotels and locked herself in her hotel room for weeks in order to get books finished.

The fabulously wealthy writers like Rowling are only 1% of all published writers. The rest of us have to juggle our days because we can’t afford to off-load everything else onto staff or contractors, or hole up in hotels.

__________

The myths about writers will probably never die — they’re far too romantic to give up. But if you take anything away from this, let it be that behind every book you love is a writer who has fought hard for the hours to create it.

It isn’t champagne and Paris cafés. It’s persistence. It’s sacrifice. And it’s a kind of stubborn joy that keeps us showing up at the desk, day after day, even when the rest of life crowds in.

That’s the truth about writers. And honestly? I wouldn’t trade it for Paris.

(Except maybe for a weekend…!)

Now available for preorder:

Breaking Point

Latest releases:

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

Captain Santiago and the Sky Dome Waitress (  Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

September 7, 2025

The Real Ladies of Waterloo Bridge

I was this close to giving the history posts a break. Honestly. I’ve been knee-deep in the past for a while now, and I figured I should let the dust settle a bit. But then I got an inbox full of emails—many of you asking for more stories about women in history. Especially the hidden ones. The overlooked, underpaid, quietly brilliant ones.

So… okay. You asked for it. And this one? It’s a doozy.

Let’s talk about Waterloo Bridge—and the women who built it.

No, not metaphorically. I mean actually built it.

During World War II, while the men were off fighting, a lot of women stepped into their boots. That part, you’ve probably heard. What you might not know is that one of the things they built, with their own hands, was Waterloo Bridge in London.

I know. It sounds like something your grandmother might say at the dinner table and everyone nods and smiles and assumes she’s exaggerating.

Except it’s true.

Waterloo Bridge as it is today.

Waterloo Bridge as it is today.More than 350 women worked on the bridge—welding, riveting, pouring concrete, doing night shifts under blackout conditions while German bombs fell. They did the job because it needed doing.

And, naturally, they were paid less than the men had been.

Because of course they were. To quote that wise philosopher Iago from Aladdin, “I’m gonna die of not-surprise!”

And just to keep things on brand: once the war ended, the women disappeared from the story. Not physically—but from the records, the ceremonies, the official tellings. When Waterloo Bridge was finally completed in 1945, there was no mention of the women who’d kept it going. No plaque. No names.

It wasn’t until decades later that someone (a historian named Christine Wall) uncovered old photos of women working on the bridge—one welder in particular, known only as Dorothy. And suddenly, the stories the boatmen on the Thames had whispered for years about the “Ladies’ Bridge” weren’t just urban legend.

They were fact.

It’s the sort of story that makes you want to cheer and gnash your teeth at the same time. Women building a literal bridge in wartime? Heroic. The world conveniently forgetting they did it? Maddening.

But now, at least, we know. And I had a little fun this week imagining what those days might’ve looked like. I asked MidJourney to conjure up a couple of images—tributes, really—to those women in overalls and headscarves, shaping steel while the world burned overhead.

You’ll find one at the top of this post, and the other just below . They’re not photographs (the real photographs are strictly controlled), and it’s not history—but it’s inspired by both.

P.S. If you’re feeling cinematic, there’s a classic film called Waterloo Bridge starring Vivien Leigh and Robert Taylor. It’s set during WWI and has absolutely nothing to do with the women who built the real bridge—but it is a gorgeous old-school tearjerker. You can stream it on HBO Max, the Roku Channel, or rent it on Amazon. Popcorn recommended.

Now available for preorder:

Breaking Point

Latest releases:

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

Captain Santiago and the Sky Dome Waitress (  Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

August 31, 2025

Spies, Secrets, and the Romance of Espionage: A Love Letter to X Company

Some stories cling to you.

Years—literal years after I first watched X Company (I found the entry in my journal this morning), I still remember entire episodes, sharp scenes, aching betrayals, and characters so vivid I can still hear their voices. That’s not hyperbole. That’s rare, honest-to-goodness storytelling that deserves more attention than it ever got.

If you haven’t heard of it (and you’re not Canadian), that’s forgivable. It’s a CBC production, after all, and Canadian shows about spies set in World War II aren’t exactly Netflix front page fodder. But X Company? It should be.

What Is X Company?At first glance, it might look like another war drama. There’s the period setting, the uniforms, the serious faces, and yes, a rosy-cheeked promo poster that lies. Ignore it. Push past it. That pastel packaging hides something dark, clever, and gut-wrenching.

The show centers around Camp X, the real-life top-secret spy training facility on Lake Ontario’s shores, where Canada trained agents for the Allied war effort. The series follows five young recruits as they parachute behind enemy lines into occupied France.

It’s smart. It’s intense. It’s heart-breaking in the way only stories about spies and war can be—filled with moral grey zones, impossible choices, and the constant, relentless tension of “What if we’re caught?”

The Drama Is There—But So Is the RomanceI’m baffled by the idea I’ve heard lately that espionage stories aren’t “romantic.”

Have we watched the same genre? Because espionage is made for romantic tension. High stakes. Secrets. Desperate decisions. The ticking clock. The longing glance that might be the last. It’s rich soil for emotional upheaval and oh-so-human connection.

X Company plays that card beautifully. The central partnership between the two leads practically aches with unspoken affection and unfulfilled longing. Would they have made a great couple? Absolutely. Do they? Well, I won’t spoil that.

But if you’re into romantic thrillers, this show scratches that itch. It does it quietly, subtly—no melodrama, just raw, real chemistry made all the more poignant because it has to simmer in the background while the world explodes around them.

And the Germans? Fascinating.Credit where it’s due: the German characters aren’t one-dimensional villains. They are layered, complex, even sympathetic in places—just as torn, just as trapped. The show doesn’t flinch from horror or humanity, and it’s better for it.

Season Three’s finale? Hold onto your heart. That’s all I’ll say.

Where to WatchIf you’re Canadian, X Company is available on CBC Gem. If you’re not, a VPN can help you access it, or you can purchase the series on platforms like Apple TV or Google Play. U.S. viewers—Apple TV has you covered.

And truly, it’s worth the effort.

A Genre That Still ThrillsRomantic thrillers—especially ones steeped in history—deserve more space. X Company proves how powerful the genre can be when it’s done well. If you love Dead Again, Hunting the Kobra, or Vistaria Has Fallen, or any of my other romantic thrillers, and that twist of emotion in a high-drama setting, you’ll find echoes of it here.

So don’t let the pastel poster fool you. This is not a soft, safe drama.

This is a brutal, brilliant, beautiful story.

And I still miss those characters.

Now available for preorder:

Breaking Point

Latest releases:

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

Captain Santiago and the Sky Dome Waitress (  Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

August 24, 2025

August 24, 410: The Day the World Changed (And Most People Missed It)

One thousand, six hundred and fifteen years ago today, the Visigoths marched into the city of Rome.

Not metaphorically. Literally. Swords out, torches lit, looting and pillaging their way through the Eternal City under the not-so-watchful eye of Emperor Honorius (who, incidentally, was holed up in Ravenna raising chickens—also not a euphemism; he was reportedly very fond of poultry).

It was the first time in 800 years that Rome had fallen to a foreign enemy. And while the city would stagger on for a few more decades, this was the end of Western Rome as it had been known. Rome—the Rome—was sacked. And nothing would ever be the same.

The emperor would eventually pack up shop and settle in Constantinople. The Roman Empire lived on in the East for another thousand years, yes—but it was never Rome again. Not the heart-pounding, empire-spanning, marble-columned colossus that had once ruled the western world.

Today marks that pivot point. The moment when the world shifted.

But Here’s the Real Story: Rome Lasted Over a Thousand YearsThink about that.

Rome was founded (according to legend) in 753 BC.

It was sacked in 410 AD.

That’s over a millennium of unbroken civilization.

When you say a millennium out loud, it sounds…vague. Abstract. Almost fluffy. Like a stat from a fantasy novel. But let’s make it real.

A Century of Change—Then Multiply by TenImagine life in 1925. Only 100 years ago.

We had just begun to recover from the First World War. Women had only just gained the right to vote. There was no penicillin. Tuberculosis was still a deadly, daily threat. Most houses didn’t have electricity or telephones. Your grandmother wore a corset, and the average woman spent most of her life either pregnant, breastfeeding, or cooking over a wood-burning stove. She couldn’t open a bank account, and depending on where she lived, she might not legally own property.

That’s what 100 years of change looks like.

Now multiply it by ten.

Ten Centuries of Roman InnovationIn those thousand years, Rome went from a muddy settlement on the Tiber to a globe-spanning empire. And they brought with them changes that improved life immeasurably:

Aqueducts that brought fresh water into cities from miles away.Sewers and underground drainage—unheard of luxuries in most of the ancient world.Concrete that we still can’t replicate today—Roman sea concrete gets stronger over time.Dentistry that included fillings, bridges, and gold crowns.Roads so straight and well-built that some are still in use.Central heating, indoor plumbing, public toilets, hot baths, libraries, and even shopping malls.And don’t forget law, architecture, and the deliciously complicated concept of citizenship.All that, and they kept it going for over a thousand years—even with emperors who were, at times, more soap opera than sovereign.

And the Women? They Changed TooIn early Rome, women weren’t even given real names—just a feminized version of their father’s family name. If you were the daughter of Agrippa, you were called Agrippina. If he had two daughters, you might be Agrippina Major and Agrippina Minor. Creative, right?

Women couldn’t vote, couldn’t hold office, and were legally under male guardianship for most of their lives.

But by the later Empire?

Women owned property, ran businesses, influenced politics, and in some cases, ruled entire regions. They had names. They had wills. They had social power. (Galla Placidia, for one, ran the Western Empire as regent—and she was taken during that 410 sack, only to return and become empress.)

One thousand years of change didn’t just build aqueducts. It built possibilities.

August 24: The Fall of Something GloriousThere’s something both awe-inspiring and tragic about the fall of Rome. To last that long, to shape so much of the world—and to finally falter.

But perhaps the greater story is not that Rome fell.

It’s that it endured for so long.

That it took over a thousand years for the world’s greatest superpower to finally lose its grip. And when it did, the world didn’t just lose a city. It lost indoor plumbing, public sanitation, written bureaucracy, widespread literacy, mass trade, and a shared identity.

We’re still chasing Roman engineering. Still borrowing from their legal system. Still marveling at their roads.

So today, take a moment to marvel—not just at the fall—but at the astonishing stretch of time before it.

Rome wasn’t built in a day. And when it fell, the echo took centuries to fade.

Latest releases:

Blackmont Bitters

Beltane Curse

Captain Santiago and the Sky Dome Waitress (  Aurealis Award Finalist!!)

Aurealis Award Finalist!!)