Stewart Brand's Blog

March 28, 2024

Members of Long Now

With thousands of members from across the globe, the Long Now community has a wide range of perspectives, stories, and experiences to share. We're delighted to showcase this curated set of Ignite Talks, created and given by the Long Now members themselves. Presenting on the subjects of their choice, our speakers have precisely 5 minutes to amuse, educate, enlighten, or inspire the audience!

We're opening talk submissions to all members in early April and will send via email; we can accept both in-person and recorded talks.

And save the date of May 29 to join us in-person and online for a fun and fast-paced evening of Long Now Ignite Talks full of surprising and thoughtful ideas.

March 20, 2024

Stumbling Towards First Light

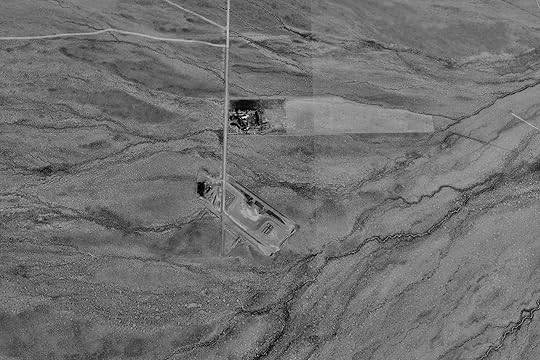

A satellite capturing high-resolution images of Chile on the afternoon of October 18, 02019, would have detected at least two signs of unusual human activity.

Pictures taken over Santiago, Chile’s capital city, would have shown numerous plumes of smoke slanting away from buses, subway stations and commercial buildings that had been torched by rioters. October 18 marked the start of the Estallido Social (Social Explosion), a months-long series of violent protests that pitched this South American country of 19 million people into a crisis from which it has yet to fully emerge.

On the same day, the satellite would also have recorded a fresh disturbance on Cerro Las Campanas, a mountain in the Atacama Desert some 300 miles north of Santiago. A deep circular trench, 200 feet in diameter, had recently been drilled into the rock on the flattened summit. The trench will eventually hold the concrete foundations of the Giant Magellan Telescope, a $2 billion instrument that will have 10 times the resolving power of the Hubble Space Telescope. But on October 18 the excavation looked like one of the cryptic shapes that surround the Atacama Giant, an humanoid geoglyph constructed by the indigenous people of the Andes that has been staring up at the desert sky since long before Ferdinand Magellan set sail in 01519.

I see the riots and the unfinished telescope as markers at the temporal extremes of human agency. At one end, the twitchy impatience of politics seduces us with the illusion that a Molotov cocktail, an election or a military coup will set the world to rights. At the opposite point of the spectrum, the slow, painstaking and often-inconclusive work of cosmology attempts to fathom the origins of time itself.

That both pursuits should take place in Chile is not in itself remarkable: leading-edge science coexists with political chaos in countries as varied as Russia and the United States. Yet in Chile, a so-called “emerging economy,” the juxtaposition of first-world astronomy with third-world grievances raises questions about planning, progress, and the distribution of one of humanity’s rarest assets.

Extremely patient risk capitalThe next era of astronomy will depend on instruments so complicated and costly that no single nation can build them. A list of contributors to the James Webb Space Telescope, for example, includes 35 universities and 280 public agencies and private companies in 14 countries. This aggregation of design, engineering, construction and software talent from around the planet is a hallmark of “big science” projects. But large telescopes are also emblematic of the outsized timescales of “long science.” They depend on a fragile amalgam of trust, loyalty, institutional prestige and sheer endurance that must sustain a project for two or three decades before “first light,” or the moment when a telescope actually begins to gather data.

“It takes a generation to build a telescope,” Charles Alcock, director of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and a member of Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) board, said some years ago. Consider the logistics involved in a single segment of the GMT’s construction: the process of fabricating its seven primary mirrors, each measuring 27 feet in diameter and using 17 metric tons of specialized Japanese glass. The only facility capable of casting mirrors this large (by melting the glass inside a clam-shaped oven at 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit) is situated deep beneath University of Arizona football stadium. It takes three months for the molten glass to cool. Over the next four years, the mirror will be mounted, ground and slowly polished to a precision of around one millionth of an inch. The GMT’s first mirror was cast in 02005; its seventh will be finished sometime in 02027. Building the 1,800-ton steel structure that will hold these mirrors, shipping the enormous parts by sea, assembling the telescope atop Cerro Las Campanas, and then testing and calibrating its incommunicably delicate instruments will take several more years.

Not surprisingly, these projects don’t even attempt to raise their full budgets up front. Instead, they operate on a kind of faith, scraping together private grants and partial transfers from governments and universities to make incremental progress, while constantly lobbying for additional funding. At each stage, they must defend nebulous objectives (“understanding the nature of dark matter”) against the claims of disciplines with more tangible and near-term goals, such as fusion energy. And given the very real possibility that they will not be completed, big telescopes require what private equity investors might describe as the world’s most patient risk capital.

Few countries have been more successful at attracting this kind of capital than Chile. The GMT is one of three colossal observatories currently under construction in the Atacama Desert. The $1.6 billion Extremely Large Telescope, which will house a 128-foot main mirror inside a dome nearly as tall as the Statue of Liberty, will be able to directly image and study the atmospheres of potentially habitable exoplanets. The $1.9 billion Vera T. Rubin Telescope will use a 3.500 megapixel digital camera to map the entire night sky every three days, creating the first 3-D virtual map of the visible cosmos while recording changes in stars and events like supernovas. Two other comparatively smaller projects, the Fred Young Sub-millimeter Telescope and the Cherenkov Telescope Array, are also in the works.

Chile is already home to the $1.4 billion Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), a complex of 66 huge dish antennas some 16,000 feet above sea level that used to be described as the world’s largest and most expensive land-based astronomical project. And over the last half-century, enormous observatories at Cerro Tololo, Cerro Pachon, Cerro Paranal, and Cerro La Silla have deployed hundreds of the world’s most sophisticated telescopes and instruments to obtain foundational evidence in every branch of astronomy and astrophysics.

By the early 02030s, a staggering 70 percent of the world’s entire land-based astronomical data gathering capacity is expected to be concentrated in an swath of Chilean desert about the size of Oregon.

A map of major telescopes and astronomical sites in Northern Chile. Map by Jacob Sujin KuppermannBlurring imaginary borders

A map of major telescopes and astronomical sites in Northern Chile. Map by Jacob Sujin KuppermannBlurring imaginary bordersCollectively, this cluster of observatories represents expenditures and collaboration on a scale similar to “big science” landmarks such as the Large Hadron Collider or the Manhattan Project. Those enterprises were the product of ambitious, long-term strategies conceived and executed by a succession of visionary leaders. But according to Barbara Silva, a historian of science at Chile’s Universidad Alberto Hurtado, there has been no grand plan, and no one can legitimately take credit for turning Chile into the global capital of astronomy.

In several papers she has published on the subject, Silva describes a decentralized and largely uncoordinated 175-year process driven by relationships—at times competitive, at times collaborative—between scientists and institutions that were trying to solve specific problems that required observations from the Southern Hemisphere.

In 01849, for example, the U.S. Navy sent Lieutenant James Melville Gillis to Chile to obtain measurements that would contribute to an international effort to calculate the earth’s orbit. Gillis built a modest observatory on Santa Lucía Hill, in what is now central Santiago, and trained several local assistants. Three years later, when Gillis completed his assignment, the Chilean government purchased the facility and its instruments and used them to establish the Observatorio Astronómico Nacional—one of the first in Latin America.

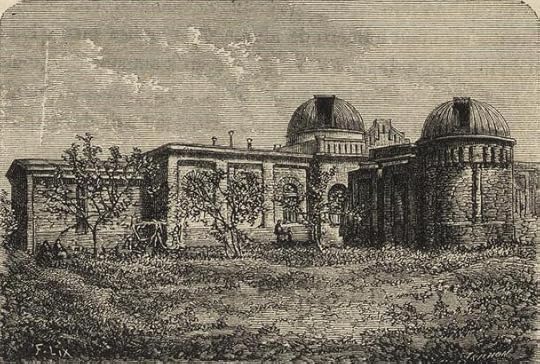

An 01872 illustration by Recaredo Santos Tornero of the Observatorio Astronómico Nacional in Santiago de Chile.

An 01872 illustration by Recaredo Santos Tornero of the Observatorio Astronómico Nacional in Santiago de Chile.Half a century later, representatives from another American institution, the University of California’s Lick Observatory, built a second observatory in Chile and began exploring locations in the mountains of the Atacama Desert. They were among the first to document the conditions that would eventually turn Chile into an astronomy mecca: high altitude, extremely low humidity, stable weather and enormous stretches of uninhabited land with minimal light pollution.

During the Cold War, the director of Chile’s Observatorio Astronómico Nacional, Federico Ruttland, saw an opportunity to exploit the growing scientific competition among industrialized powers by fostering a host of cooperation agreements with astronomers and universities in the Northern Hemisphere. Delegations of astronomers from the U.S., Europe and the Soviet Union began visiting Chile to explore locations for large observatories. Germany, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Sweden pooled resources to form the European Southern Observatory. By the late 1960s, several parallel but independent projects were underway to build the first generation of world-class observatories in Chile. Each of them involved so many partners they tended to “blur the imaginary borders of nations,” Silva writes.

The historical record provides few clues as to why these partners thought Chile would be a safe place to situate priceless instruments that are meant to be operated for a half-century or longer. Silva has found some accounts indicating that Chile was seen as “somehow trustworthy, with a reputation… of being different from the rest of Latin America.” That perception, Silva writes, may have been a self-serving “discourse construct” based largely on the accounts of British and American business interests that dominated the mining of Chilean saltpeter and copper over the previous century.

Anyone looking closely at Chile’s political history would have seen a tumultuous pattern not very different from that of neighboring countries such as Argentina, Peru or Brazil. In the century and a half following its declaration of independence from Spain in 01810, Chile adopted nine different constitutions. A small, landed oligarchy controlled extractive industries and did little to improve the lot of agricultural and mining workers. By the middle of the century, Chile had half a dozen major political parties ranging from communists to Catholic nationalists, and a generation of increasingly radicalized voters was clamoring for change.

In 01970 Salvador Allende became the first Marxist president elected in a liberal democracy in Latin America. His ambitious program to build a socialist society was cut short by a U.S.-supported military coup in 01973. Gen. Augusto Pinochet ruled Chile for next 17 years, brutally suppressing any opposition while deregulating and privatizing the economy along lines recommended by the “Chicago Boys”— a group of economists trained under Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago.

Soviet astronomers left Chile immediately after the coup. American and European scientists continued to work at facilities such as the Inter-American Observatory at Cerro Tololo throughout this period, but no new observatories were announced during the dictatorship.

Negotiating access to timeWith the return of democracy in 01990, Chile entered a period of growth and stability that would last for three decades. A succession of center-left and center-right administrations carried out social and economic reforms, foreign investment poured in, and Chile came to be seen as a model of market-oriented development. Poverty, which had affected more than 50 percent of the population in 01980s, dropped to single digits by the 02010s.

Foreign astronomers quickly returned to Chile and began negotiating bilateral agreements to build the next generation of large telescopes. This time, Chilean researchers urged the government to introduce a new requirement: in exchange for land and tax exemptions, any new international observatory built in the country would need to reserve 10 percent of observation time for Chilean astronomers. It was a bold move, because access to these instruments is fiercely contested.

Bárbara Rojas-Ayala, an astrophysicist at Chile’s University of Tarapacá, belongs to a generation of young astronomers who attribute their careers directly to this decision. She says that although the new observatories agreed to the “10 percent rule,” it was initially not enforced—in part because there were not enough qualified Chilean astronomers in the mid-01990s. She credits two distinguished Chilean astronomers, Mónica Rubio and María Teresa Ruiz, with convincing government officials that only by enforcing the rule would Chile begin to cultivate national astronomy talent.

Maria Teresa Ruiz (Left) alongside two of the four Auxiliary Telescopes of the ESO’s Very Large Telescope at the Paranal Observatory in the Atacama Region of Chile. Photo by the International Astronomical Union, released under the

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Maria Teresa Ruiz (Left) alongside two of the four Auxiliary Telescopes of the ESO’s Very Large Telescope at the Paranal Observatory in the Atacama Region of Chile. Photo by the International Astronomical Union, released under the

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

The strategy worked. Rojas-Ayala was one of hundreds of Chilean college students who began completing graduate studies at leading universities in the Global North and then returning to teach and conduct research, knowing they would have access to the most coveted instruments. Between the mid-01990s and the present, the number of Chilean universities with astronomy or astrophysics departments jumped from 5 to 24. The community of professional Chilean astronomers has grown ten-fold, to nearly 300, and some 800 undergraduate and post-graduate students are now studying astronomy or related fields in Chilean universities. Chilean firms are also now allowed to compete for the specialized services that are needed to maintain and operate these observatories, creating a growing ecosystem of companies and institutions such as the Center for Astrophysics and Related Technologies.

By the 02010s, Chile could legitimately boast to have leapfrogged a century of scientific development to join the vanguard of a discipline historically dominated by the richest industrial powers—something very few countries in the Global South have ever achieved.

From 30 pesos to 30 yearsThe Estallido Social of 02019 opened a wide crack in this narrative. The riots were triggered by a 30-peso increase (around $0.25) in the basic fare for Santiago’s metro system. But the rioters quickly embraced a slogan, “No son 30 pesos ¡son 30 años!,” which torpedoed the notion that the post-Pinochet era has been good for most Chileans. Protesters denounced the poor quality of public schools, unaffordable healthcare and a privatized pension system that barely covers the needs of many retirees. Never mind that Chile is objectively in better shape that most of its neighboring countries—the riots showed that Chileans now measure themselves against the living standards of the countries where the GMT and other telescopes were designed. And many of them question whether democracy and neo-liberal economics can ever reverse the country’s persistent wealth inequality.

Protestors at Plaza Baquedano, Santiago, Chile in October 02019. Photos by Carlos Figueroa, CC Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Protestors at Plaza Baquedano, Santiago, Chile in October 02019. Photos by Carlos Figueroa, CC Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 InternationalWhen Gabriel Boric, a 35-year-old left-wing former student leader, won a run-off election for president against a right-wing candidate in 2021, many young Chileans were jubilant. They hoped that a referendum to adopt a new, progressive constitution (to replace the one drafted by the Pinochet regime) would finally set Chile on a more promising path. These hopes were soon disappointed: in 02022 the new constitution was rejected by voters, who considered it far too radical. A year later, a more conservative draft constitution also failed to garner enough votes.

The impasse has left Chile in the grip of a political malaise that will be sadly familiar to people in Europe and the United States. Chileans seemingly can’t agree on how to govern themselves, and their visions of the future appear to be irreconcilable.

For astronomers like Rojas-Ayala, the Estallido Social and its aftermath are a painful reminder of an incongruity that they experience every day. “I feel so privileged to be able to work in these extraordinary facilities,” she said. “My colleagues and I have these amazing careers; and yet we live in a country where there is still a lot of poverty.” Since poverty in Chile has what she calls a “predominantly female face,” Rojas-Ayala frequently speaks at schools and volunteers for initiatives that encourage girls and young women to choose science careers.

Rojas-Ayala has seen a gradual increase in the proportion of women in her field, and she is also encouraged by signs that astronomy is permeating Chilean culture in positive ways. A recent conference on “astrotourism” gathered educators and tour operators who cater to the thousands of stargazers who arrive in Chile each year, eager to experience its peerless viewing conditions at night and then visit the monumental Atacama observatories during the day. José Masa, one Chile’s most celebrated astronomers, has filled small soccer stadiums with multi-generational audiences for non-technical talks on solar eclipses and related phenomena. And a growing list of community organizations is helping to protect Chile’s dark skies from light pollution.

Astronomy is also enriching the work of Chilean novelists and film-makers. “Nostalgia for the Light,” a documentary by Pedro Guzmán, intertwines the story of the growth of Chilean observatories with testimonies from the relatives of political prisoners who were murdered and buried in the Atacama Desert during the Pinochet regime. The graves were unmarked, and many relatives have spent years looking for these remains. Guzman, in the words of the critic Peter Bradshaw, sees astronomy “not simply an ingenious metaphor for political issues, or a way of anesthetizing the pain by claiming that it is all tiny, relative to the reaches of space. Astronomy is a mental discipline, a way of thinking, feeling and clarifying, and a way of insisting on humanity in the face of barbarism.”

Despite their frustration with democracy and their pessimism about the immediate future, Chileans are creating a haven for this way of thinking. Much of what we hope to learn about the universe in the coming decades will depend on their willingness to maintain this uneasy balance.

February 7, 2024

On Exactitude in Climate Science

In July 02023, climate scientist Bjorn Stevens paused in the middle of a virtual talk about data and modeling to quote a short story by Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges. Borges’ work does not often come up in the context of climate modeling — but Stevens invoked him for a reason beyond idle literary fascination. Referencing “On Exactitude in Science,” Borges’ single-paragraph story in which an empire creates maps of ever-increasing size, until they perfectly match the territory they are mapping, Stevens warned of a looming crisis of scale occurring in the field of climate science. In Borges’ story, the map becomes useless in its magnitude; in climate science, the mad dash to reach kilometer scale climate simulations could make climate models too large to matter to the world outside of academia. How much data is too much data? What will it really mean to model the climate on 1-km scales?

Researchers are actively pursuing the answers to these questions, and CMIP7, the latest phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project and the state-of-the-art for global climate models, will continue a trend of increasing resolution and dataset size. As new developments in computing and data storage advance the capabilities of the field to capture more detailed understandings of Earth systems, climate models like those comprising CMIP7 have the potential to become even larger leviathans: petabytes of data, tens of millions of lines of code, years of constantly running simulations, all to model one future pathway. Stevens’ reference makes clear a countercurrent running through the field, as urgency to measure, simulate, and respond to climate change compounds, while traditional methods to increase resolution offer diminishing returns. It’s a current that seeks to move climate science out of the stuffy halls of academia and into the hands of policymakers, businesses, journalists, and laypeople. Climate science goes public. But these changes to the field surface new entanglements with social and political forces that mark it as a contested discipline in which present developments will greatly influence future collective decision making.

Climate science is notoriously complex, with models containing upwards of the equivalent of 18,000 printed pages of code and consuming the energy equivalent of over 6,000 households per year to complete. CMIP7, the largest coordinated modeling project to date, consists of a multi-year effort to standardize, document, and coordinate across research areas including cloud patterns, various regional phenomena, land use scenarios, paleoclimate, and geoengineering — just to name a few. The data that scientists, researchers, and technicians feed into climate models adds up to quantities at the order of millions of gigabytes, costing hundreds of millions of dollars.

As a researcher of climate models without formal training in climate science, this means that I’ve spent months poring over the minutiae of atmospheric halocarbon concentrations, upwelling longwave radiation, climate reanalysis, and much more in order to grapple with the sheer volume and dizzying depth of the Earth System Models (ESMs) I work with every day. Increasingly, as data about the behavior of Earth systems increases and advances in the methods for synthesizing said data add nuance, it takes teams of experts to explain the details of how we know the extent to which climate change is occurring. Due to ESMs’ substantial run time and the limited availability of supercomputers in modeling centers, ESMs are typically only used to model a particular set of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), so as to be most useful for IPCC reports. But SSPs only account for a narrow view of potential societal and demographic changes, and ESMs typically do not include aspects of climate science such as pre-1850 anthropogenic experiments and methane emissions from thawing permafrost.

In July 02023, leaders and experts from the fields of climate science, technology, and sustainability convened in Berlin to address these issues, among others, for the Earth Virtualization Engines (EVE) Summit. It is EVE, a new international initiative coordinating and governing a digital commons of climate data and projects, that Stevens was positing as a solution to the crisis of scale in climate science, illuminated by his reference to Borges. Technology providers are interested, too, with Nvidia offering to integrate efforts by scientists and research institutions into their product Earth-2: an ambitious attempt to create digital twins of the planet. Digital twins virtually re-create a process or object such that its behavior can be simulated. Typically used to simulate consumer products or components of infrastructural systems, the digital twin ascends to new heights with Earth-2, a constantly running simulation of Earth systems distilled down into a single, unified data product.

These twins would differ from standard climate models in a few ways. The primary mode of interaction with a digital twin is via a graphical interface, rather than a code editor, utilizing personal computers rather than supercomputers. Only a few clicks on a digital twin interface, as previewed by Nvidia, will simulate weather conditions at 1.25km resolution on a global scale — a level of granularity rarely found outside regional climate models and ensembles. What’s more, Nvidia proposes to dynamically simulate Earth systems on temporal resolutions from the daily to the hourly, as opposed to the scenario-based modeling that shows up in the IPCC reports of today. In theory, an Earth digital twin will capture the entirety of interconnected atmospheric, oceanic, and geologic systems for ongoing manipulation and visualization — an ultimate simulation of our planet.

Climate change is everyone’s problem; a planetary conundrum rather than a scientific issue.

The lofty goals outlined in the EVE Summit statement offer an appealing view of a more public climate science. A dynamic visualization of the planet like the one showcased by Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang at the summit takes the immense complexity of climate data and makes it into something more intuitive to those not already steeped in the field. Whereas previously the user of climate modeling outputs might be a professor, graduate student, or author of an IPCC report, supporters of Earth digital twins purport that non-experts may soon be able to interact with and explore changes to the climate system, “on your PC, your tablet, or your phone.” The implication here is a deprofessionalization of climate science, a technological corollary to the idea that climate change is everyone’s problem; a planetary conundrum rather than a scientific issue.

Floating in a Sea of DataA day in the life of a climate scientist differs depending on the person, but generally it looks like data: millions of rows of spreadsheets, Jupyter notebooks galore. It makes my head spin each time I encounter a new massive and inscrutable dataset, and learn how essential it is to making our models a little bit better. One colleague of mine described their work as “floating in a sea of data.” They meant it both metaphorically and literally, as they split their time between doing data analysis and studying the historical climate record by collecting sediment cores from the ocean floor. But opening up climate science to a broader audience means moving the visual interfaces of the field from the spreadsheet closer to the sci-fi interface — from staid rows and columns to an interactive, dynamic globe. This was on full display during the EVE Summit, when Huang demonstrated the capabilities of Earth-2 without displaying a line of code or spreadsheet entry. Instead, the high-production visuals showed swirling wind currents over satellite imagery of the earth. Then, they zoomed into Berlin, to show how those same wind currents flowed within a three-dimensional model of the city’s urban landscape. The sea of data is still there, of course. It’s going to take an immense amount of data and code written by climate scientists to power the sleek interfaces of an Earth digital twin, not to mention teams of designers and product managers to make the simulations come to life. But it’s obscured now; and in that obfuscation, the spinning globes of Earth-2 indicate a change in who climate science is for.

With developments such as Earth-2, the “user” of a climate simulation no longer needs a training in atmospheric physics or ocean currents, but can instead direct their attention towards implications for policy, urban planning, or infrastructure development. More public climate science means tools like Earth-2 that serve as a tool for action, for making decisions about where to build a direct-air capture plant, how to reduce emissions from public transportation, and when to anticipate the “unprecedented” weather that characterizes living in the midst of climate crisis. This move to deprofessionalize climate science, whether through a digital twin or otherwise, is a welcome one, as it signals an understanding that positioning ourselves as planetary inhabitants is an essential part of making responsible decisions on collective scales, from the local to the regional to the global.

It also matters what worlds make up our simulations, and what simulations shape how we live in our world.

Earth digital twins signal a future in which climate models become infrastructure for our collective knowledge — simulations serving as not just scientific tools but essential components of how we understand ourselves and act together. Said infrastructure will not only inform global challenges; local, regional and state decision making will rely upon simulations to ensure that the planetary system remains in homeostasis. Yet this shift in paradigm is far from a given. The EVE proposal will only succeed with billions of dollars of funding and an unprecedented level of international cooperation, bringing together industrial titans like NVIDIA and multiple national governments. Where the money comes from and which actors will step up to provide support is still unclear — EVE may very well turn out to be another failed proposal on the long road to understanding climate change. Regardless of whether or not EVE in particular succeeds, the ambition towards deprofessionalized climate science feels like something of a fait accompli — a socio-technological shift that promises to become the bedrock upon which we stand as planetary inhabitants.

But that’s exactly what this is: a promise. Becoming infrastructure marks a shift for climate science: from a particular and limited field within earth science to an increasingly contested zone of planetary knowledge-creation and knowledge-instantiation. Following feminist technoscientific philosopher Donna Haraway, “it matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.” It also matters what worlds make up our simulations, and what simulations shape how we live in our world.

Agreements over what constitutes our world rarely come easily. The ways that we collectively resolve conflicts over emissions data, geopolitically-sensitive data, and statements of culpability will dictate whose Earth is being twinned, and who gets a say in the future of global decision making. Who gets to model the Earth? And what is done to resolve disagreements when governments refuse to release verifiable emissions information? What happens when the climate impact of running these simulations continues to grow? What will make an Earth digital twin spur more action than an already-constrained IPCC?

A Dance of Competing ModelsThere’s no easy answer to these questions, but the consequences of them will influence how we understand ourselves within a planetary system throughout the long now. To understand these potential consequences and the tensions we face now to resolve them, I posit three experiments in thinking about climate modeling: adversarial modeling, recursive modeling, and actionable modeling. In response to the contested nature of an expanded climate science, thinking through these experiments means pre-emptively addressing what will become dominant questions in how we know what we know about climate change.

Adversarial modeling questions how competing simulations of Earth systems change the dynamics of climate science. Climate science becoming the infrastructure of collective decision making means that governments and geopolitical entities have differing incentives to share or obfuscate data about their climate actions. Certain elements of assembling a climate model are outside the purview of state actors: carbon dioxide levels, remote sensing. But considering the economic benefits of obfuscating a coal power plant, for instance, from an aerial view, means considering that the factual basis upon which an Earth digital twin is constructed may never be assured. Sources of climate data range from ostensibly-neutral remote sensing datasets to highly-biased private sector disclosures to often-questionable state emissions numbers, all of which contain their own uncertainties and possibilities for obfuscation. As such, we can anticipate a future of adversarial climate modeling, in which differences in measurement are leveraged to de-legitimize other climate models, for the sake of avoiding culpability.

In this dance of competing models, a singular source of truth appears unattainable. A public, infrastructural climate science must contend with information asymmetries and contested sources of data. Identifying and verifying the data of climate science is sometimes possible, as coalitions such as Climate TRACE demonstrate, but it is never guaranteed and always ongoing. As STS scholar Bruno Latour has argued, we now live on different planets, and these changes are unlikely to reverse themselves. Earth digital twins will only be successful in becoming a trusted infrastructure of collective decision making if they allow for and clearly describe the differences in sources of data that undergird their simulations. Interpretability is paramount; for climate science to make the leap to a more public sphere, it must address the ambiguous nature of its data sources and uses. Adversarial climate modeling guides us as we consider what form(s) future knowledge on climate change will take, and as we address the challenge of tackling a planetary crisis with asymmetrical impacts.

But climate science is not a map, and this is no fantastical speculation.

Increasing the scope of climate science means increasing the resources the field consumes. As such, future climate models will encounter a challenge of recursive modeling — simulating the climate impacts of the model itself. Climate scientists gathering data on such a scale as to induce recursive modeling resemble the cartographers in “On Exactitude in Science”. But climate science is not a map, and this is no fantastical speculation. Digital technologies already have a growing carbon footprint larger than the airline industry. Water usage for cooling data centers threatens already-constrained ecosystems. In becoming infrastructure, climate science must contend with its own climate impact, which includes modeling the model itself. As a climate model simulates the world, it must simulate itself; an ongoing dynamic model, such as the one discussed at the EVE conference, must continually undergo this recursive action. This is an issue for complex systems of all sorts, as seen in a recent uptick in emissions as a result of the boom in large language models (LLMs).

While some recent developments in climate modeling, such as emulators, may serve to reduce the resource guzzling computational needs of a massive climate model, initiatives such as EVE must address their climate impact or risk further adding to the problem they hope to solve. Thinking through recursive modeling means considering how an infrastructural climate science will need to take measures to address its own climate impact even as it supports actions to decarbonize.

Moving climate science outside of academia and towards more public stakeholders presents a third proposition of actionable modeling. In this case, climate modeling undergoes a slight shift as it focuses more on the actions that are facilitated by a model, rather than the overall understanding of the system. While these goals are far from incompatible, a more actionable climate modeling is one in which outcomes of specific actions, such as the building of a new direct-air capture plant or an expansion of a city’s public transportation network, are expressly integrated into the system and interface. Huang notes that EVE “envisions a world where everyone knows how climate and climate change affect them, and where this knowledge empowers them to act.” But how does a climate model become empowering? The more a simulation is altered to become actionable, the more it reflects the desires and biases of its creators. Will an actionable climate model project the benefits of solar geoengineering, or will it demonstrate how reduced meat consumption would alter the air quality of a region? Of course, a climate model can do both, but the developers behind an Earth digital twin must contend with the fact that each design decision will have effects in how the product influences action. Actionable climate models have the power to expand the science behind a wider array of potential climate actions, but will always carry with them a bias in how and for whom the actions they model are displayed.

Simulating the deeply entangled Earth systems that comprise climate entails a gargantuan effort of coordination and computation. The warning of Borges’ overzealous cartographers and the promise of Huang’s Earth digital twins both speak to a tension in contemporary climate science. As urgency to take action on climate change accumulates, climate modeling will play an essential role in collective decision making. Considering how a deprofessionalization of climate science presents new provocations for adversarial, recursive, and actionable modeling entails an intentional contemplation of the future of our entanglement with Earth systems.

Like many of my colleagues, I was drawn to work in climate science by the urgency and immensity of these provocations. I don’t want to end up like one of Borges’ cartographers, pursuing something grandiose and ultimately ineffectual. Instead, I want a climate science that anticipates geopolitical differences, refuses to pursue scale for the sake of scale, and that facilitates more ambitious climate actions. The future of climate simulations is entangled with the future of our species’ relationship to Earth systems. Let this be an opportunity to take that entanglement seriously.

January 24, 2024

To Save It, Eat It

An early victim of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the genetic riches of one of the traditional breadbaskets of humanity. In the first months of the conflict, Russian shells hit the Plant Genetic Resources Bank in Kharkiv. Founded in 01908, the gene bank preserved the seeds of 160,000 varieties of crops and plant seeds from around the world, and was the repository for many unique cultivars of Ukrainian barley, peas, and wheat. Tens of thousands of samples, some of them centuries old, were reduced to ash.

“Under Hitler’s Germany, when the whole of Ukraine was under occupation, the Germans did not destroy this collection,” a lead researcher at the institute told the online newspaper The Insider. “They knew their descendants might need it. After all, every country’s food security depends on such banks of genetic resources.”

A similar fate befell one of the world’s most important collections of wheat landraces, as varieties that have adapted to local conditions, often over thousands of years of cultivation, are known. Located in Aleppo, the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) kept tens of thousands of varieties of wheat and other food plants, from 128 countries, in cold storage. When the Syrian civil war began in 02011, staff set to work loading 20,000 precious samples of crop varieties, not duplicated in other gene banks, across the borders to Turkey and Lebanon.

“It was looted,” Ahmed Amri, the director of ICARDA, told me on a video call from the gene bank’s new location in Morocco. “The latest news is that it was completely destroyed.”

Genetic samples from Ukraine's Plant Genetic Resources Bank. Photograph by Tetyana Brivko, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Genetic samples from Ukraine's Plant Genetic Resources Bank. Photograph by Tetyana Brivko, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United NationsGene banks are a crucial resource for ensuring the world’s food security. They provide back-up specimens of the seeds of the plants, as well as the eggs and semen of the livestock, that nourish humanity. Like public lending libraries, they then distribute these genetic riches free of charge to just anybody who asks. There are 1,750 such institutions around the world, safeguarding everything from yeasts, to olive cultivars, to pig breeds. (My personal favorite is the Puratos Sourdough Library in St-Vith, Belgium, which keeps more than a hundred sourdough starters from around the world, some of them over a century old, bubbling and alive with regular feedings.) But, like nuclear power plants, they are vulnerable to natural disaster, and — as in Ukraine and Syria — can become targets in times of war.

The “Backup of the Backups” is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, located on an island halfway between the Norwegian mainland and the North Pole. Svalbard stores seeds of hundreds of thousands of crop varieties, including 150,000 samples of wheat and rice, in a setting where the average winter lows hover around -4 degrees Fahrenheit. But Svalbard Island is also one of the most rapidly warming places in the world. In 02017, melting permafrost caused the vault’s entrance to flood, though fortunately there was no permanent damage to the collection.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Photograph by Frode Ramon (CC BY 2.0 DEED)

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Photograph by Frode Ramon (CC BY 2.0 DEED)Which means that keeping copies of the earth’s genetic riches on ice is, at best, cold comfort. Seeds need to be removed from storage and germinated on a regular basis to remain viable. But in our era of soil degradation, rapidly-evolving pests and pathogens, and a fast-changing climate, there is no guarantee that frozen germplasm will be able to thrive to feed future generations. That’s why we need to foster living diversity in fields and farms. The best we can do for endangered wildlife, from Bengal tigers to sperm whales, is to give them the space to live — in other words, to leave them alone. The best we can do for ancestral grains and forgotten livestock breeds, in contrast, is to cultivate them, and yes, to eat them.

The background to this is the global biodiversity crisis; the rate of species loss, which is hundreds of times faster than it has been in the last 10 million years, has led some to declare we are in the midst of a “sixth extinction.” But few are aware that agrobiodiversity — the range of plants and livestock that feed us — is also in rapid decline. Nearly a tenth of the world’s estimated 8,800 livestock breeds are already extinct. Every month, a half dozen more are lost forever. The same phenomenon afflicts traditional crop varieties. Since 01900, it is estimated that three-quarters of the genetic diversity once stored in farmers’ fields has been lost. The way we farm today, raising vast acreages of crops, many of them genetically modified or scientifically hybridized to maximize yield, leaves them vulnerable to such diseases as wheat rust and corn smut.

While researching my book The Lost Supper, I traveled to Puglia, the bootheel of Italy, where farmers have come to rely on a few varieties of olive to produce extra virgin oil. But now these trees, some of them over 2,000 years old, are succumbing to a bacterium, imported on ornamental coffee plants from Costa Rica, known as Xylella fastidiosa. Much of the region is now a spooky landscape of skeleton forests. The most promising cure comes from wild olive varieties found growing in farmers’ fields, which can be grafted onto trees, to save them from infection. I’ve been to the Olive World Germplasm Bank in Córdoba, Spain, and it is a crucial institution, run by dedicated scientists and technicians. But Puglia’s olive oil industry is being saved not by germplasm, but by the natural variety preserved in fields, orchards, and farms.

Diversity, simply put, is the key to resiliency. That’s true of the microorganisms in the soil beneath our feet, in the microbiome in our guts, and in the variety of foods we eat. In our 300,000 or so years of existence as a species, we have nourished ourselves on a minimum of 10,000 distinct plant species. Today, fewer than 150 are cultivated for consumption. The latest science says that people who consume at least thirty species of plants a week in their diet — most of us get half that number or less — tend to be as disease-free as those who follow a completely vegan diet. Our monocultures, which rob us of the polyphenols, omega-3 fatty acids, and other micronutrients essential for good health, are making us sick. The antidote is to pursue diversity in our diet, and support those food producers who work hard to keep less common varieties alive.

“In Canada and the United States, diversity is largely gone from the field,” says Colin Khoury, a director at the San Diego Botanic Garden who has published extensively on crop biodiversity. “When a farmer grows something, saves the seed, and plants in the next year, you have ongoing evolution. And that gives you the diversity you need for unforeseen issues in the future. The hubris of putting everything in a seed bank — basically freezing diversity — is that you believe you have everything you need for the present and the future.”

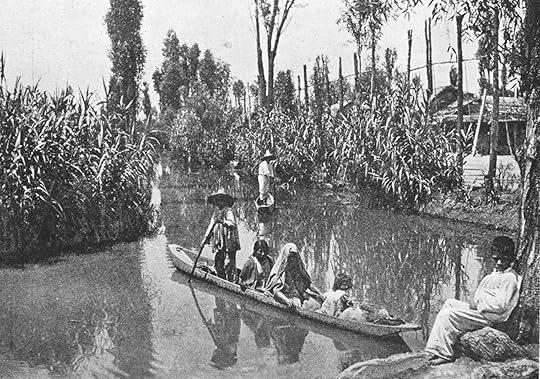

In my research, I’ve encountered many good examples of solutions to our diversity and sustainability crisis, most of them rooted in pre-industrial agricultural practices. In Europe and North America, for example, mixed farms practice an age-old form of what is now known as regenerative agriculture or permaculture: pigs, chickens, cattle and other breeds of heritage livestock provide the manure that boosts soil fertility and replaces synthetic fertilizers. An increasing number of farmers in the United States, Canada, and Britain are embracing “no-till” farming, a plough-free method which reduces the amount of synthetic fertilizers and water needed to raise crops, while preserving biodiversity in the field. In Central America, I saw the milpas, or cornfields, where ancient varieties are interplanted with squash and beans, infusing the soil with nitrogen. In Mexico City, chinampas, or “floating gardens,” a form of raised bed agriculture that used to feed millions in Aztec times, continue to allow for several harvests a year. Indigenous communities around the world are storehouses of such traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), from the controlled burns once used in the Americas to manage game and edible plant populations and limit the fuel for wildfires, to the ancient agroforestry methods that have shaped the Amazon basin. All provide startling amounts of calories on limited acreage, while encouraging, rather than detracting from, biodiversity.

The Aztec-originating chinampas, or "floating gardens." Photograph by Karl Weule, Leitfaden der Voelkerkunde, Leipzig 01912

The Aztec-originating chinampas, or "floating gardens." Photograph by Karl Weule, Leitfaden der Voelkerkunde, Leipzig 01912There is a happy conclusion to the story of Kharkiv’s gene bank, one summed up in a proverb common among my own Ukrainian ancestors: “They tried to bury us. But they didn’t know we were seeds.” Late last spring, the parts of the collection untouched by the attack were moved to an undisclosed location in the western part of the country, as far as possible from Putin’s reach. This is an important win, but the true riches of Ukraine lie in the chernozem, the nation’s dark, humus-rich loam, where varieties of beets, barley, potatoes, rye, and bread wheat will continue to evolve — conflict permitting — in an ever-changing environment.

The same is true of every other food-producing region in the world. The soil beneath our feet is the ultimate source of agrobiodiversity, nutrition, and flavor. That soil is now being impoverished by the chemicals needed to bring monocultures to harvest. Don’t get me wrong: gene banks are an essential insurance policy for future food security. But the real way forward is to take the seeds and eggs out of the cold, and get them into the soil, the farms, and the pastures — and, in good time, onto our plates.

—

Taras Grescoe is the author of The Lost Supper: Searching for the Future of Food in the Flavors of the Past (Greystone, 02023).

December 21, 2023

Alicia Escott and Heidi Quante

The Bureau of Linguistical Reality is a participatory artwork facilitated by artist Alicia Escott and Heidi Quante which collaborates with the public to create new words for feelings and experiences for which no words yet exist. Recognizing the climate crisis is causing new feelings and experiences that have yet to be named, the project was created with a deep focus on these and other Anthropocenic phenomena. The Bureau views the words created in this process as also serving as points of connectivity: advancing understanding, dialogue, and conversations about the greater concepts these words seek to codify.

This evening will include an intimate sharing of our findings from our decade long social art practice as well as a Word Making Field Session where Escott and Quante will collaborate with participants to collectively coin a term together.

Participants are encouraged to consider in advance their personal unnamed experience(s) of our changing world as well as their unique feelings for which they wish there was a word. Participants are encouraged to bring the diversity of their linguistic backgrounds to this conversation as the Bureau creates neologisms in all languages.

December 7, 2023

The Enduring Trajectory of Jewish Fashion

Tops cut out of jacquard tapestry and edged with thick fringe. A capsule of modest house dresses in Laura Ashley prints. The ubiquitous flip-flop. These garments dominate the fashion trends of 02023. Yet they also share an unlikely precedent – one that my time in Jewish day school perhaps should have helped me anticipate: the Torah.

Understanding the history of Jewish fashion is essential not only for the Jewish community but for anyone interested in the dynamics of cultural preservation, adaptation, and the broader impact of religious culture on fashion. Even those who simply want to stay on top of the seemingly inscrutable ebbs and flows of contemporary style might find answers in the sartorial trajectory in Jewish culture.

Jewish fashion offers a unique lens through which to explore the enduring power of religious and ethnic aesthetics without defaulting to caricaturization. These pieces of distinctly Torah-informed fashion do not utilize religious iconography in obvious or over-played ways. Instead, they find their potency in utilitarian design choices, materials steeped in the patterns of a globe-traversing diaspora, and details that carry the weight of sacred signification into even the most secular use cases.

Growing up in a fairly religious Jewish household and focusing more on memorizing my Bat Mitzvah portion than on the aesthetics of Abraham, I never considered the Torah as a potential source of style inspiration. In the contemporary fashion world, though, designers often pull from sources as diverse as horror movies, copies of National Geographic, or retro video games in their search for aesthetic goldmines. Fresh-feeling sartorial semiotics are often sublimated into a “-core,” a shorthand for a coherent aesthetic code centered around anything from ballet to Ivy League schools that originated with the staid “Normcore” in 02014. In response to the oft-asked question “Is nothing sacred?”, the 02010s said “Not in fashion!” with a wave of “Catholic-core” dressing that germinated on Tumblr, largely thanks to a resurgence of the 01999 film adaptation of The Virgin Suicides.

This trend’s zenith was the 02018 Met Gala, themed “Heavenly Bodies” and packed with celebrities festooned in papal gear, Virgin Mary blue, and, of course, omnipresent crucifixes. Catholic-core has had about 2000 years to ferment in the collective consciousness, but most of its manifestations have a distinctly 01980s, Madonna-sountracked ethos to them, perhaps due to that decade’s mainstreaming of a sexy, almost secular side of Christianity — a visual breakdown of the Madonna (original variety)-whore dichotomy.

Yet the connections informing Catholic-core have deeper roots than 02014 or 01989. The religion’s spiritual and operational center being in Italy, where hyper-recognizable ateliers like Gucci, Versace, and Armani were founded in the 20th century, contributed to the coevolution of haute couture and the Catholic power structure. The Pope himself is now outfitted in vestments tailored by Fillipo Sorcinelli, a “hipster” in the purest sense of the word, his tattoos of sacred geometries and high-end perfume making signaling that the “cool factor” of Christianity has permeated to its very core in a way that never struck me in the case of Judaism while surveying the outfits of fellow worshippers in synagogue as a kid.

My own faith’s path to the heights of fashion was a more tangled one. This partly results from the religion’s long-held resistance toward depicting its key figures, and partly from the long history of anti-semitic marginalization of Jews in Europe. Yet while these factors may have prevented Jewish style from becoming an obvious bastion of elite taste, it's precisely why it has gained broad and appreciated influence. The special features that make Ashkenazi Jewish clothing stand out historically can be turned into everyday clothes that capture the magic of garments tied to a sacred tradition. Without resorting to costumey, inappropriate appropriation, Jewish fashion situates contemporary, secular style in a much stronger throughline to Biblical fashion than one might expect.

Early depictions of what Hebraic peoples wore were mainly created by their conquerors. According to Rabbi Dr. David Moster, the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (a Neo-Assyrian king who reigned in the 9th century BCE) might be the oldest recovered artifact to depict a figure from Old Testament lore: Jehu, King of Israel (of Book of Kings Part Two fame) and his attendants are engraved into the limestone, offering tributes and bowing in supplication to Shalmaneser III himself.

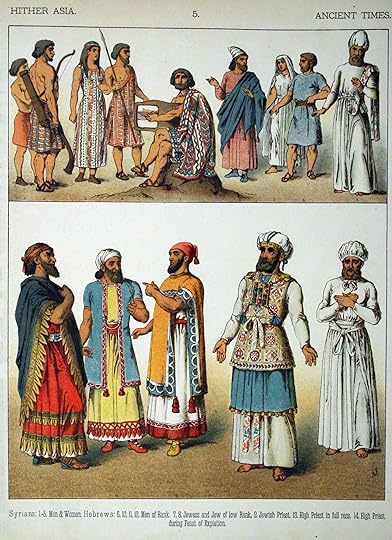

A panel from the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III depicting Israelites carrying tribute. Note the fringes on their garments.

A panel from the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III depicting Israelites carrying tribute. Note the fringes on their garments.Like a catwalk, the line of Northern Kingdom Israelites wrapping around the obelisk seems designed to show off not only the offerings they had in tow, but their code of style as well. The traditional outfitting of people of Hebraic descent in the Levant and West Asia, from at least a thousand years BCE until the 01920s, mainly consisted of cloaks, tunics, and caps.

FromCostumes of All Nations (01882), illustrated by by Albert Kretschmer, painters and costumer to the Royal Court Theatre, Berin, and Dr. Carl Rohrbach

FromCostumes of All Nations (01882), illustrated by by Albert Kretschmer, painters and costumer to the Royal Court Theatre, Berin, and Dr. Carl RohrbachA cloak, or mantle, was used not only for coverage and warmth but as a blanket to sleep within. Women typically wore a cloak-like headdress that extended down to their ankles and was used for the same purposes (and, famously, for accidentally inventing the unleavened Matzah eaten on Passover: “So the people took their dough before it was leavened, their kneading bowls being bound up in their cloaks on their shoulders.” [Exodus 12:34]).

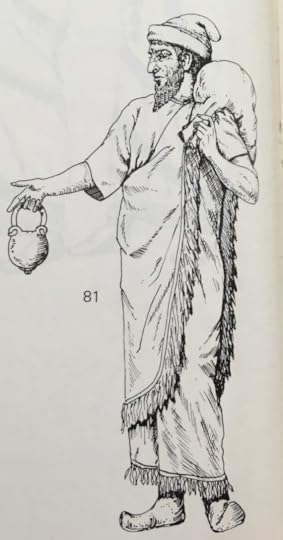

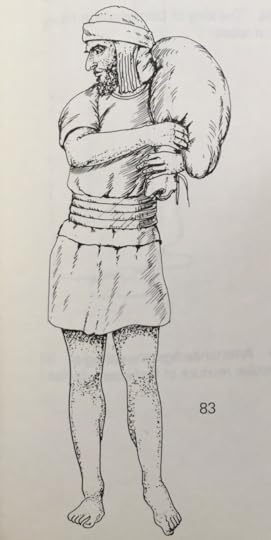

Source:

Costume of Old Testament Peoples

by Philip J. Watson

Source:

Costume of Old Testament Peoples

by Philip J. WatsonUnder that top layer and against the skin, people of all genders wore long, simple, short-sleeve tunics akin to housedresses. The famous “Technicolor Dream Coat” bestowed upon Joseph by his ever-loving father was more likely one of these tunics, heavily ornamented with expensive embroidery.

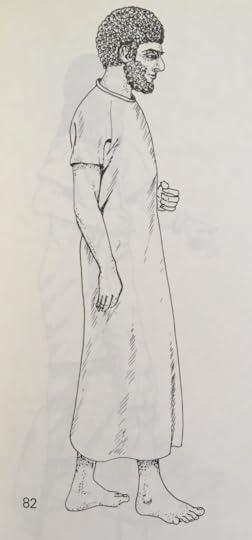

Source:

Costume of Old Testament Peoples

by Philip J. Watson

Source:

Costume of Old Testament Peoples

by Philip J. WatsonLastly, the distinctive caps worn by the men on the Shalmaneser obelisk resemble a modern-day beanie. They likely evolved into the kippah, a recognizable symbol of Jewish identity and public commitment to the faith.

The most notable aspect of the Shalmaneser obelisk outfits is that every exposed hemline of the Israelites drips with thick fringe, or tzitzit. In Numbers 15:38-39, God instructs Moses to “Speak to the people of Israel, and tell them to make fringes on the corners of their garments throughout their generations…And it shall be a fringe for you to look at and remember all the commandments of the Lord, to do them, not to follow after your own heart and your own eyes…” The first real ornamentation we’ve encountered in Jewish clothing is one that customs instruct people to gather in their hands, kiss, and wrap around their fingers — an intimate reification of connection to god and fellow humans.

The cloak, the tunic, and the cap are all Torah-era garments that have traversed thousands of years, manifesting in Jewish wardrobes in ways both traditional and oblique. According to Rabbi Moster, until the 01920s, many Jewish and Bedouin descendants of Israelites in Ottoman and British Palestine dressed with the exact same formula as was biblically sanctioned.

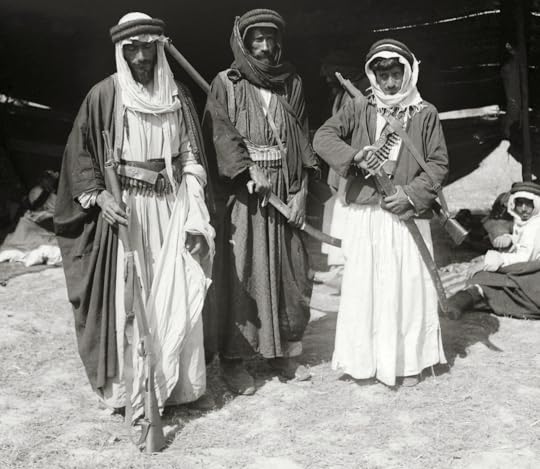

A group of Bedouin men circa 01900 in Jerusalem. Photo from the G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

A group of Bedouin men circa 01900 in Jerusalem. Photo from the G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.Of course, the dress in biblical times was not nearly uniform, with much room for variation in materials and accessories. In a Torah passage describing an ideal woman: “All her household are clothed in scarlet…her clothing is fine linen and purple…She makes linen garments and sells them; she delivers girdles to the merchant” (Proverbs 31:21-24). Linen was the material of choice for almost every garment due to its breathability in extremely hot weather, and could be dyed to signify status and wealth. Girdles are wide cloth belts often used to “gird,” or fasten into a shorter skirt for mobility, the aforementioned tunic (hence the phrase “gird your loins”).

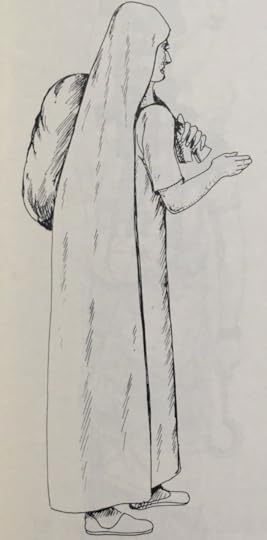

Source:

Costume of Old Testament Peoples

by Philip J. Watson

Source:

Costume of Old Testament Peoples

by Philip J. WatsonAnother facet of adornment in Jewish fashion is the lack of iconographic garments. In Judaism, the depiction of sacred entities is explicitly prohibited. “You shall not make for yourself a carved image,” the Torah’s God says, “or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (Exodus 20:4). While Christianity has its crucifix, ichthys fish, images of the Virgin Mary weeping, and more to incorporate into its sartorial canon, Jewish fashion steers clear of any such embellishment, thus creating a trend of adorning garments and accessories with symbols that cannot be taken as profane. A popular tack is the use of florals, fruit, and vegetables as design elements, which has a precedent in the biblical description of high priestly garments, with the sacred apron, or ephod, as the most obvious example: “You shall make pomegranates of blue and purple and scarlet yarns, around its hem, with bells of gold between them” (Exodus 28:33).

A Jewish High Priest depicted in ceremonial robes and breastplate

A Jewish High Priest depicted in ceremonial robes and breastplateAbout 2,000 years after Shalmaneser III’s Black Obelisk captured the Israelite fashion of the time, Jewish culture recentered to the north, as Jews in the Levant and West Asia began to immigrate – first to Southern Europe and then to Eastern Europe, many to Poland and other central and eastern European countries. In Poland, Jews faced a jarring pendulum swinging between othering and attempts to force assimilation. Even under regimes not actively attempting to kill or expel Jewish populations, legislation alternately followed the West European practice of requiring Jews to wear distinctive clothing, such as yellow headgear as mandated by Polish authorities in 01538, and tried to abolish distinctively “Jewish” dress, as the Russian government did in 01804. The general poverty and cultural insulation of Jewish villages, or shtetls, created a new standard for utilitarianism in Jewish wardrobes, producing what is recognizable as an Ashkenazi Jewish style. Mantles became mantl cloaks; animal skins, fur, silk, and satin replaced linen as choice materials to bulwark against the harsh Eastern European winters; the cylindrical, furry shtrayml overtook the beanie-like caps as the go-to headwear; men largely adopted pants, while womens’ tunics morphed into what we would now consider house dresses — still decorated, if printed, with the produce and florals that allowed for idolatry-free adornment.

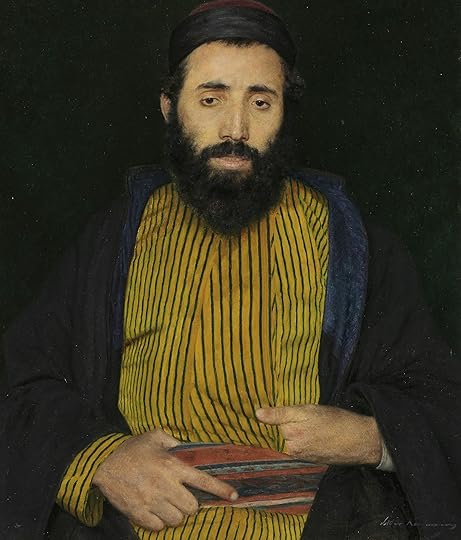

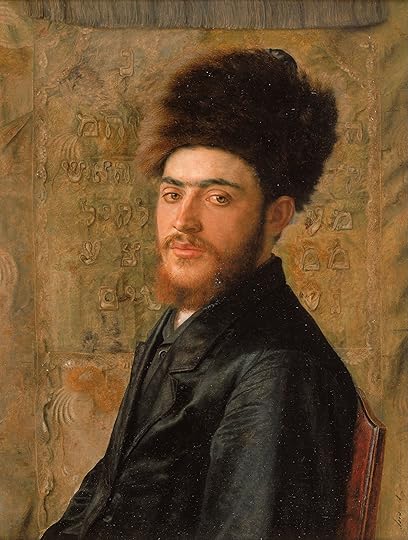

Isidor Kaufmann's Man With Fur Hat depicts the traditional clothing of Eastern European Jewry in the early modern period.

Isidor Kaufmann's Man With Fur Hat depicts the traditional clothing of Eastern European Jewry in the early modern period.Two unique accessories to come out of the 600-some years after the bulk of Jewish immigration to Poland were the apron (though it could be argued that the priestly ephod set a precedent for apron-as-statement-piece), worn by women to evoke domesticity and handiness but also to “protect” the world from their sinister reproductive organs; and the harband, a hairband to which was attached fake or real hair, often braided or otherwise ornamented, to be worn over womens’ real hair, a practice that continues to this day in Orthodox communities, where married women cover their hair with wigs, or sheitls.

In the 01880-01920 rush of Jewish immigration to the United States, most immigrants were funneled through New York City, marking it as the Jewish hub of the country. By way of the common immigrant professions of fabrication and garment work, Jewish people filtered into the sphere of fashion design. In the early 01900s, a cohort of Jewish leftist radicals emerged within the fashion world, their presence emblematic of the era's socio-political ferment. Many were influenced by broader movements advocating for workers' rights and progressive ideologies.

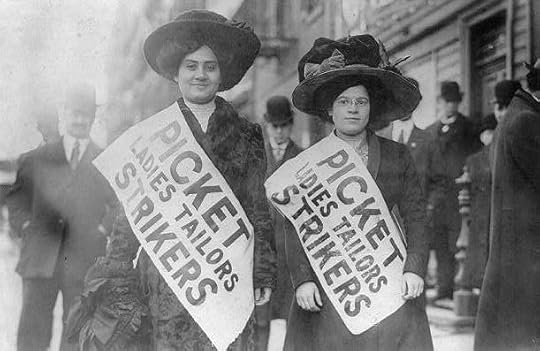

Two women strikers on picket line during the February 01910 "Uprising of the 20,000", garment workers strike, New York City.

Two women strikers on picket line during the February 01910 "Uprising of the 20,000", garment workers strike, New York City.This convergence of political and sartorial activism found expression in the clothing industry, where Jewish leftist radicals engaged in initiatives such as workers' strikes and labor organizing to address issues of exploitation and unfair labor practices. In November 01909, over 20,000 predominantly Jewish women employed in the garment industry orchestrated an 11-week-long strike that is credited with initiating a five-year period of upheaval, rendering the garment industry one of the most well-organized trades in the United States. The Lower East Side of New York City, a hub for both Jewish immigrants and the garment industry, served as a crucible for these developments and became a mecca of cutting-edge style that continually churned out the most thoughtful, progressive fashion on the scene. Jews such as Calvin Klein, Tory Burch, and Isaac Mizrahi dominated the fashion world of the 90s and into the aughts, but it was in the 02010s when designers’ Judaism started to make a more apparent emergence in their work.

Batsheva Hay founded her eponymous brand in 02016, bringing the silhouette of the house dress into the realm of cutting-edge fashion, its lineage from the tunics of ancient Jewish dress and its play on Talmudic ideals of modesty, or tznius, setting a new standard for casual dress-wearing that favored high necks, loose cuts, and materials that recalled centuries-old Eastern European garb — moiré, liberty prints, and satin are recurring standbys. Carly Mark’s Puppets and Puppets released its first commercial collection in 02021, with a standout accessory: a leather purse stretched into the ruby sphere of a patinated pomegranate. The brand has since released a series of food-related handbags, one of its most popular referencing a more contemporary, New Yorkian Jewish food, the black and white cookie.

Source: Vogue

Source: VogueAs is made obvious by the success of these two brands’ ventures into garments with strong connections to the historical trajectory of Jewish fashion, the secularization of Jewish motifs is inevitable in the 02020s style sphere. Brands such as Marland Backus have delved into the creation of hair accessories made out of faux hair, much like the above-mentioned harbands. Fringe was declared an across-the-board trend in 02022, while skullcaps have dominated the commercial sphere for the past year or so.Even the flip-flops that seemed omnipresent this past summer can be traced back to leather thongs, the footwear of choice in biblical times.

This continuity in Jewish clothing styles has been influenced by a historical interplay between high and low culture materials and silhouettes, originally stemming from fluctuations in the economic and social status of Jewish communities. Over time, it evolved into something of a tradition, passed down from generation to generation among the Jewish Diaspora. The media's portrayal of Jews as both wealthy and frugal, when wielded negatively, can be damaging and violent. However, within Jewish communities and families, there is often a recognition of the humorous juxtaposition of styles that seems to embody this stereotype. It's a common sight to find a Jewish grandmother who staunchly refuses to part with her well-worn sandals from the 01960s, paired incongruously with a designer handbag. These stylistic contradictions serve as a testament to the endurance of cultural quirks and inside jokes, becoming an aesthetic unto itself.

Recently, the fashion industry has been actively moving away from appropriating overtly racial aesthetics in light of the broader discussions about racial inequality. Many white fashion enthusiasts have become more conscious of the need to scrutinize the roots of the latest trends, recognizing that the cultural appeal of a trend often originates in a context that may exclude them from fully embracing it. While some trends remain free from racially charged associations, they may also lack the distinctive element that tends to drive appropriation in the first place: a visual link to something sacred or bearing a rich history.

Unlike some trends that rely on eye-catching, easily recognizable (and usually holy, thus not appropriate for day-to-day wear by someone not in the community) symbols, such as the rosary with crucifix worn by Madonna on many an 80s red carpet, Jewish fashion draws its strength from a deeper, more subtle well of tradition and history. Its beauty lies in its ability to bridge the gap between the sacred and the secular, creating garments that resonate with timeless allure and without the need to caricaturize or parody the culture in question.

This renaissance of Jewish-inspired fashion highlights the enduring pull of garments deeply rooted in tradition. Jewish fashion's historical trajectory, from the Israelite people's ancient clothing to its evolution in Eastern Europe and subsequent migration to the United States, paints a vivid picture of cultural adaptation and preservation. It is a testament to the resilience of traditions that have endured through millennia, while also embracing new elements and influences. As Jewish fashion continues its under-the-radar influence on the contemporary fashion world, it serves as a reminder that clothing can be more than just a form of self-expression. It can be a bridge connecting past and present, tradition and innovation, and faith and fashion. In a world often focused on trends and novelty, Jewish-inspired fashion stands as a symbol of the enduring power of culture in the ever-evolving realm of style.

December 6, 2023

Jonathan Cordero

This talk won't be livestreamed on February 6, but the video and podcast will be released shortly after the event.

Alternative visions for social change rooted in the frameworks of capitalism and colonialism only reproduce contemporary structures of power. How can indigenous perspectives and knowledge inform the structural transformation necessary to improve the health of the natural world and of human communities?

Dr. Cordero will discuss how indigenous epistemologies challenge the ideas and practices related to capitalism and colonialism and how the enhancement of indigeneity and sovereignty are critical to the maintenance of indigenous epistemologies. Insights drawn from the discourses on decolonization, settler colonialism, and epistemicide will be revealed throughout the presentation. Last, Dr. Cordero will share how indigenous perspectives and knowledge inspire work of the Association of Ramaytush Ohlone.

November 30, 2023

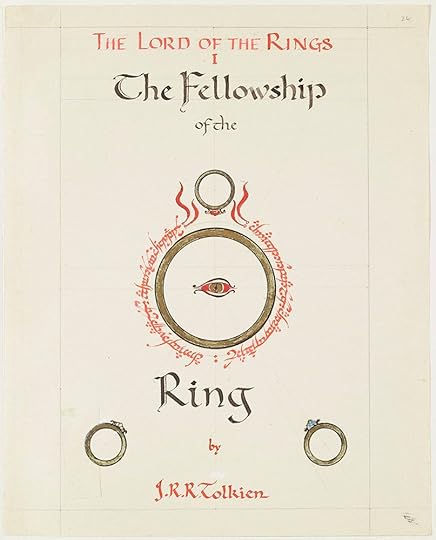

The Work that Lasts

The blessing of art is that we can all do it. Our lives are better when we take the time to make things, with our hands or voices or imaginations. Building an artistic practice into our daily routines as working adults makes us better friends, lovers, parents, people. As a hobby, a routine, a practice, art is something which connects us to our own spirits and those spirits that came before and will come after.

But to be an artist — to then take that practice and make it what each day depends on, and revolves around — requires a greater amount of commitment to a lifestyle and a purpose than most of us are able to muster. Not all of us are capable of that kind of commitment for an individual project, let alone across a career-length span of time.

As someone who is pretty permanently scattered, with piles of unfinished projects littering my past, what I admire most about artists who consistently produce original work is just that — their ability to conceive of and complete a piece, any piece, at all. During quarantine I started a draft for a novel that I still genuinely feel passionately about, but after less than a week of achingly slow progress I threw up my hands and gave up.

Sometimes I imagine, though: what if I kept going — and going, and going, and going? I have an especial level of fascination and respect reserved for projects that take a long time. I mean, a really long time. I can hardly commit to a career, or a unifying aesthetic for my tiny apartment, and yet there are artists out there spending ten years on a painting, twenty years on a sculpture, forty years on a film.

Gazing Into the InfiniteThe contemporary art world was abuzz last year with the news that Michael Heizer’s massive City project was finally being unveiled. It had been in the works since the 01970s, when Heizer was a feted young artist in the New York City scene, hanging out at Max’s Kansas City and leading the charge, alongside artists like Robert Smithson, of the nascent land-art movement.

Michael Heizer's City, as captured by aerial and satellite imagery in 01999, 02006, and 02020, respectively. Imagery from Google Earth Pro.

Michael Heizer's City, as captured by aerial and satellite imagery in 01999, 02006, and 02020, respectively. Imagery from Google Earth Pro.Located on a property in Garden Valley, Nevada, which Heizer purchased before beginning the project, City is the largest piece of land art ever completed, at a-mile-and-a-half long by a half-mile wide. Inspired by Mesoamerican monumental architecture and contemporary urban landscapes, City’s construction relied on Heizer’s idiosyncratic, perfectionist approach: concrete curbs, sculpted planes, oblong mounds all made out of locally sourced materials.

He completed other works during the forty years it took to finish City to his satisfaction, including the iconic Levitated Mass at LACMA, but City was his main preoccupation. Though Heizer can be dismissive, even self-deprecating at times about his work, just reading about it fills me with awe: “You’re meant to suffer its distances, its depressions and swells, and hear the crunch of gravel — to give yourself over to the peace and quiet, which itself takes on a sculptural presence.”

It reminds me of how I felt witnessing Marcel Duchamp’s final work, the elusive Étant donnés: 1. La chute d'eau, 2. Le gaz d'éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas). Towards the end of his career Duchamp went into seclusion, absorbing himself for over twenty years in the production of a single sculptural work. Many people believed that he had retired, or moved over entirely to competitive chess. Yet in his Greenwich Village studio between 01946 and 01966 he secretly completed Étant donnés, a sculptural work carefully constructed to be viewed only through a peephole.

The exterior of Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo by Regan Vercruysse,

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

The exterior of Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo by Regan Vercruysse,

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

Installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art after his death according to a detailed manual he left behind, the assemblage of wood, plastic, twigs, glass, and even human hair forms a striking image of a naked woman, her legs spread and her arm outstretched, holding a lamp, against a forested landscape. There is almost infinite meaning there, infinite detail: one can easily imagine Duchamp spending twenty years living inside the world of the piece, adjusting it, one twig at a time. It’s like spying on a crime scene, a YouTube commenter says on a POV video of the work. I could’ve spent years just looking at it.

Works like John Cage’s As Slow As Possible were intended and promoted as durational from the start. But a project which merely starts and keeps going and going can, if it is worked on in private, become inherently interesting because of the combination of duration and secrecy. The self-control to keep something under one’s belt as it is slowly completed adds to the eventual mystique of the piece once finally revealed. Henry Darger, the legendary outsider artist, showed nobody at all the monumental paintings and manuscripts he carefully collaged in his tiny Chicago apartment for decades while he worked as a janitor. It was only once he moved to a nursing home that his landlord, an art dealer, caught a glimpse of his stacks of watercolors and collages and realized their importance.

Conversely, some long-term projects are worked in public, in plain sight — not blessed with the remoteness of Heizer’s ranch or the hermitage of Darger’s lonely bedsit. Antoní Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia is a world-famous visual of the unfinished opus, with a succession of architects carrying on work on the cathedral in the century after its original designer’s death. The Watts Towers of southern Los Angeles, built in the backyard of Italian construction worker Sabato Rodia, went up in full view of the neighborhood over the course of 33 years, beginning in 01921. The concrete and rebar complex, adorned with mosaics of porcelain and glass, has become a world-famous landmark.

Sabato Rodia's Watts Towers in Los Angeles (L) were constructed in public view for more than three decades; Antoní Gaudí's Sagrada Familia in Barcelona (R) is still under construction and has been a major tourist site for more than a century. Left photo by Wikipedia user BenFrantzDale, CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED. Right photo by JB aus Siegen, CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED

Sabato Rodia's Watts Towers in Los Angeles (L) were constructed in public view for more than three decades; Antoní Gaudí's Sagrada Familia in Barcelona (R) is still under construction and has been a major tourist site for more than a century. Left photo by Wikipedia user BenFrantzDale, CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED. Right photo by JB aus Siegen, CC BY-SA 4.0 DEEDFrom world-renowned high-art sculptors to lonely janitors, the call to a life’s work does not discriminate. Is there a unifying factor between all the different kinds of people who are able to turn one vision into a lifelong project? It seems clear to me in my attempts at starting projects that I personally don’t have whatever gene or tendency is necessary for such commitment. What moves a person onto this path? Is it any different from a more conventional artistic life? Maybe that movement could still come later, when the right project comes along.

“Are you sure you want to do this?”To find out how exactly an artist gets started on a long-term project, I spoke to the only person I know who has committed to an endeavor like this. Through my abiding interest in Antarctica, I befriended Sarah Airriess, a Canadian animator and illustrator who left behind a successful career at Disney in Los Angeles in order to move to the UK and devote her time entirely to adapting Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s classic travelog, The Worst Journey In The World. To turn the book about Robert F. Scott’s last expedition into a series of graphic novels, she would have to commit to a project which might take her decades. Polar explorers like Scott journeyed into the unknown interior of Antarctica in order to pursue scientific and geographic truths, in a life’s work of exploration; artists embark on great projects for purposes a little more obscure, at least to onlookers.

Airriess acknowledges that the dedication which accompanies a lifelong artistic endeavor can be confusing and sometimes a point of concern. “People ask me, are you sure you want to do this? It’s going to take forever. But they never ask people who get married or have children if they're sure they want to do that.”