Mark Schaefer's Blog

March 7, 2022

The Casualties of War

Russians doubling down on the rightness of their country’s actions in Ukraine are not doing so because of any objective evaluation of the facts or weighing of the sources; they’re doing so because it’s too painful not to.

The post The Casualties of War appeared first on The Certainty of Uncertainty.

January 11, 2021

The Capitol Insurrection, Qanon, and Absolute Certainty

The violent insurrection at the Capitol on January 6 is the consequence of many things, but at its heart is the need for absolute certainty. On January 6, a crowd of rioters stormed the United States Capitol, intent on disrupting the ceremonial tally of Electoral College votes by a Joint Session of Congress. They were […]

The post The Capitol Insurrection, Qanon, and Absolute Certainty appeared first on The Certainty of Uncertainty.

October 26, 2020

Embrace the Uncertainty

When we are unable to embrace the uncertainty of the world around us, particularly in matters of great personal and public concern, we often retreat into the safe havens of projected certainty.

The post Embrace the Uncertainty appeared first on The Certainty of Uncertainty.

October 12, 2020

Indigenous Peoples, Colonialism, and Metaphor

Embracing metaphor is a powerful way to reject the legacy of colonialism and to affirm the value of indigenous peoples and cultures. It is a way to embrace both the diversity of different cultural expressions and a greater unity across cultural differences.

The post Indigenous Peoples, Colonialism, and Metaphor appeared first on The Certainty of Uncertainty.

July 10, 2020

Faith, Doubt, and Inspiration

Rev. Mark Schaefer, author of The Certainty of Uncertainty, is featured on the most recent episode of Rev. Dr. Robert LeFavi’s podcast: Inspirational Sermons: Insights from America’s Best Preachers. Rev. Schaefer was invited on the program to talk about his sermon on uncertainty and doubt—“Am I Lost If I Have Doubt?”—the latest version of the sermon that gave rise to the The Certainty of Uncertainty.

Visit the podcast website to read the transcript and listen to this and other episodes. You can also listen to the podcast episode on the Spotify player below.

April 25, 2020

The One Thing Certain: Why We Desire Certainty

By the time you finish reading this book, you could be dead.

It’s not that long a book, but even so, a car accident, a slip and fall, a random crime, a plane crash, a sudden and devastating disease, a heart attack, a brain aneurysm, or any other random lethal misfortune could claim your life before you get to the final page. Or not. The problem is that you don’t know which fate awaits you.

The post The One Thing Certain: Why We Desire Certainty appeared first on The Certainty of Uncertainty.

The One Thing Certain

By the time you finish reading this book, you could be dead.

It’s not that long a book, but even so, a car accident, a slip and fall, a random crime, a plane crash, a sudden and devastating disease, a heart attack, a brain aneurysm, or any other random lethal misfortune could claim your life before you get to the final page. Or not. The problem is that you don’t know which fate awaits you.

We, perhaps alone among the creatures that inhabit the globe with us, can contemplate our own mortality. We are aware of the basic fact that one day we will cease to exist. We are conscious of the reality of our inevitable deaths, but we don’t know what it all means or what, if anything, lies beyond death.

Miguel de Unamuno, Agence de presse Meurisse

The Spanish philosopher and writer Miguel de Unamuno wrote that our fears and anxieties around death drove us to try to figure out what would become of us when we die. Would we “die utterly” and cease to exist? That would lead us to despair. Would we live on in some way? That would lead us to become resigned to our fate. But the fact that we can never really know one way or the other leads us to an uncomfortable in-between: a “resigned despair.” [1]

Unamuno refers to this “resigned despair” as “the tragic sense of life.” For Unamuno, this tragic sense of life created a drive to understand the “whys and wherefores” of existence, to understand the causes, but also the purposes, of life. The terror of extinction pushes us to try to make a name for ourselves and to seek glory as the only way to “escape being nothing.” [2]

There is an additional consequence to our mortality beyond this “resigned despair” and the “tragic sense of life.” Our awareness of our own mortality also creates a great deal of anxiety. Because we know neither the date nor the manner of our own deaths, we are left with unknowing and uncertainty, and are plagued by angst on an existential level.

There are two basic responses to that anxiety: acceptance and resistance. We could accept the reality of death, given that the mortality rate has remained unchanged at exactly one per person regardless of our attitudes toward death or attempts to deny it. But we seem to prefer resistance. This is not surprising; we have too many millions of years of evolutionary survival programming in us to surrender to non-existence without at least putting up something of a fight, even if we cannot ultimately win that fight. And when death does come, we bury and keep our dead, as if refusing to hand them over to the indifferent ground without one last act of defiant resistance. [3]

Some psychologists maintain that practically everything we do is a kind of resistance in reaction to our awareness of our mortality. [4] This terror management theory posits that our desire for self-preservation coupled with our cognitive awareness of our inevitable deaths leads to a “terror” that can only be mitigated in two ways. First, we mitigate this terror with self-esteem—the belief that each of us is an object of primary value in a meaningful universe. Second, we mitigate our terror by placing a good deal of faith in our cultural worldview. The faith we put in a cultural worldview gives us a feeling of calm in the midst of dread. Our commitment to an understanding of the world around us makes us feel safe and secure in the face of our looming mortality.

However, when those same worldviews are threatened, so too is that feeling of calm. For that reason, we have to defend our worldviews at all cost because they protect us from facing the terror of our mortal lives. [5] Preserving our worldviews is so central to staving off our existential dread that it turns out that the more we think about death and oblivion, the more invested we become in preserving those worldviews. [6]

It seems that one of our preferred methods of defending our worldviews and fending off this core terror is the attempt to establish as many certainties as possible, to know that there is something we can be certain of. In an effort to deny our mortality and the recognition that we are not ultimately in control of our own destinies, we try to control our world and one another and we seek to cling to as many certain truths as we can along the way.

We might be comfortable with uncertainties when they are restricted to trivial concerns or are unthreatening: the uncertainty of the solution to a crossword puzzle, or a sudoku, or a mystery novel are acceptable, and the resolution of those uncertainties with the solution to the puzzle or mystery brings a measure of emotional satisfaction. However, when the uncertainties involved deal with “real world” issues—whether we’ll have a long and healthy life, whether our beloved will be faithful to us, whether we’ll have job security, or whether we’ll find or maintain happiness—we are not as comfortable. In fact, we are more inclined to anxiety. [7]

This is especially true for the anxiety we feel about any of what psychotherapist Irvin Yalom calls the “four ultimate concerns”: death, freedom, existential isolation, and meaninglessness. [8] We’re anxious about death. We’re anxious about the choices we have to make. We’re anxious about the fact that we enter and leave the world alone. And we’re anxious because we fear that life has no intrinsic meaning. All of this creates in us a desire to obtain as much control and certainty as we can. We become increasingly concerned with getting “closure” and resolving our uncertainty. [9]

Even when we’re not consciously looking for certainty to resolve our anxieties, we seek it out. It’s not that we’re even always consciously aware of our need for certainty; much of the drive to be certain is deep in our psychology. We are driven to be certain as a consequence of the fact that our thought processes are divided into two basic domains. As psychologist Daniel Kahneman argues, there is a fast-moving, automatic “system” that we’re barely aware of (System 1), and a slower, effort-filled process that includes deliberative thought and complex calculation (System 2). [10] System 1 is designed for quick thinking and does not keep track of alternatives; conscious doubt is not a part of its functioning. System 2, on the other hand, embraces uncertainty and doubt, challenges assumptions, and is the source of critical thinking and the testing of hypotheses. However, System 2 requires a great deal more processing power and energy, and it can easily be derailed by distraction or competing demands on our brain power. Kahneman writes:

System 1 is not prone to doubt. It suppresses ambiguity and spontaneously constructs stories that are as coherent as possible. . . . System 2 is capable of doubt, because it can maintain incompatible possibilities at the same time. However, sustaining doubt is harder work than sliding into certainty. [11]

In short, certainty is easier on the brain than uncertainty is; uncertainty requires more mental effort.

Even beyond this function of the way our brains work, the human need to be certain is reinforced by the expectations of others. Experts are not paid high salaries and speaking fees to be unsure. Physicians are expected to give diagnoses that are certain even when that certainty is counterproductive to their effectiveness. Even when a little uncertainty might be life-saving in many cases—for example, ICU clinicians who were completely certain of their diagnoses in cases where the patient died were wrong 40 percent of the time—it is generally considered a weakness for clinicians and other experts to appear uncertain or unsure. [12] Thus, expectations from others often drive us to be more certain than we have cause to be.

We are creatures seeking meaning in an unpredictable world of unclear choices and random, seemingly meaningless happenstance; we crave certainty. We want to be certain about something. And so, we find that in the meaning-making areas of our lives, such as religion or politics, we are tempted to edge closer and closer to absolute certainty in doctrine, belief, and ideology.

But is such certainty even possible? Can we really know anything with certainty?

Even when we are certain that we know something, do we really know it or just think we do? Imagine I say to you, “I am certain that Lisa will say yes to our business offer.” What am I certain of, really? That Lisa will, in fact, say yes or the fact that I believe she will say yes?

This conundrum is complicated by the fact that there is a sensation known as the feeling of knowing that can fool us into unmerited certainty. The feeling of knowing is best illustrated by that feeling of satisfaction you receive when you’ve figured out a crossword puzzle, suddenly understood the point your teacher was trying to make, or have had some other insight in which you finally “get” something. However, this feeling of knowing turns out to be just that—a feeling; it’s independent of any actual knowledge. It’s similar to the feeling associated with mystical states and religious experiences, which can often feel like having come to know something without actually having any specific knowledge. People who have had a mystical experience will testify to having “understanding” or “knowing” but often cannot tell you what it is they have come to know. These experiences make it clear that there are instances of the experience of the feeling of knowing that don’t involve any actual thought or knowledge. There has been no thought, no deliberation, no thought process; there is only that feeling you know something. Thus, the feeling of knowing is what cognitive psychologists refer to as a primary mental state—a basic emotional state like fear or anger—that is not dependent on any underlying state of knowledge. [13]

Now, the feeling of knowing may be an important part of how we learn—it’s that boost of dopamine we get when we’ve learned something. Without this pleasant feeling, our drive to learn and comprehend might not be as strong. The problem is, because it is a mechanism of encouragement—it’s a real confidence booster—it can drive us to rush to conclusions in our thinking, even before those thoughts have been worked out. We may be in such a rush to get that burst of good feeling that we ignore the fact that we haven’t actually come to learn anything beyond our own belief. This feeling, as physician and author Dr. Robert Burton puts it, is “essential for both confirming our thoughts and for motivating those thoughts that either haven’t yet or can’t be proven.” [14]

We human beings are often hindered in our ability to distinguish actually knowing something from the feeling of knowing something. We have a troublesome combination of a highly fallible memory and an overconfidence about our knowledge. [15] We frequently fail to understand the limits of what we can know. We often imagine that our conclusions are the result of deliberate, reasoned mental processes when the reality is that our feelings of certainty come not from rational, objective thought, but from an inner emotional state. As Burton concludes: “Feelings of knowing, correctness, conviction, and certainty aren’t deliberate conclusions and conscious choices. They are mental sensations that happen to us.” [16]

If this weren’t bad enough, we’re often blind to our ignorance because our brain likes covering the gaps in our knowledge. For example, you may not realize it, but you have blind spots in your visual field, which you can spot with a simple trick. If you hold your hands out with your index fingers pointing up, close your right eye and look at your right finger with your left eye, while you slowly move your left hand to the left—at a certain point the tip of your left index finger will just disappear. Keep moving your hand and the fingertip will reappear. We don’t normally notice this blind spot because our brain is really good at patching the holes in our sensory inputs and does so with our visual blind spot.

In the same way that our brain glosses over the blind spots in our visual field, it may be that we likewise cover the blind spots in our knowledge. When we are conscious and perceiving things, inconsistencies are more detrimental than inaccuracies, and so the holes in our knowledge are more troubling than the fact that the holes are filled with erroneous information. [17] As Kahneman noted above, System 1 of our mental processes is inclined to smooth over gaps in our understanding; it is a coherence-seeking machine designed for “jumping to conclusions.” [18]

The reality is, then, that very often our feelings of certainty are not grounded in any reality that is certain, but simply in our belief that we have truly come to know something. Our certainty often comes merely from feeling that we are certain.

Perhaps this false sense of certainty is a function of our human nature. As human beings, we often find a measure of ambiguity to be a motivator toward productivity in order to resolve the ambiguity, but we are uncomfortable with prolonged uncertainty and unknowing. And perhaps our desire for certainty arises out of a deeper desire to believe that things can, in fact, be known.

Sherlock Holmes, Juhanson / CC BY-SA

It was Arthur Conan Doyle who said, “Any truth is better than indefinite doubt.” In so doing, he articulated an attitude that has recently become an object of study. Scientific research into our reactions to ambiguity and uncertainty in the last decade has identified something known as the need for closure. This need for closure is a person’s measurable desire to have a definite answer on some topic—“any answer as opposed to confusion and ambiguity.” This impulse to resolve the tensions of uncertainty and ambiguity can be strong and may be what makes some people susceptible to extremism and claims of absolute certainty. [19] Even in those who are not tempted into extremism, there is nevertheless a discomfort with not knowing, with uncertainty.

It may also be the case that the desire for certainty is borne out of a feeling of powerlessness. We live in a time of increasing alienation and an increasing sense of disenfranchisement. As a result of technology and an ever more interconnected world, the world that people knew growing up is rapidly disappearing: the homogenous, ethnically privileged, culturally distinct society that many people knew is yielding to a diverse, multiethnic, multicultural society that no longer operates on the same assumptions as its predecessor. In addition, a predominantly rural way of life is yielding to a predominantly urban one. There is nothing inherently wrong with any of these changes but they can be unnerving to many. And many who find global changes terrifying feel powerless and out of control in their ability to stop them or at least to slow them to a comfortable pace. Being in command of the truth is at least being in command of something.

What does this all mean, then, for our quest for certainty as a way of coping with the anxieties of existence? Have we simply been going about the quest for certainty in the wrong way, relying too much on cognitive illusions and feelings instead of a more certain foundation, or should we abandon the quest for certainty altogether?

To answer that question, we must first undertake a journey, through our world, the language we use to communicate about the world and our experiences in it, and the great systems we construct that help us to give meaning to the experiences we have.

This passage is an excerpt from The Certainty of Uncertainty: The Way of Inescapable Doubt and Its Virtue by Mark Schaefer. © 2018 Mark Schaefer. All Rights Reserved.

Learn more about the book or learn about purchasing the book.

Notes

19. Holmes,Nonsense,11–12.

March 16, 2020

A Plague of Uncertainty

A simple glance at your social media newsfeeds today will tell you that all anyone is thinking about is the novel coronavirus and its associated disease COVID-19.

The reaction you’re probably witnessing on those same feeds ranges from indifference to calm cautiousness to outright buy-up-all-the-toilet-paper panic. On the latter end are people acting like we’re in the opening scenes of The Walking Dead or Contagion. And on the former end are those who seem utterly unconcerned about the coronavirus or its effects. They’ll say things like, “The flu kills way more people a year than this virus has but we don’t close down March Madness for the flu!” Or they’ll point out that the mortality rate is low, at most 3%, which means that most people will suffer the disease with low impact.

But what goes unrecognized in such an analysis is that it’s not the disease that’s frightening; it’s the uncertainty.

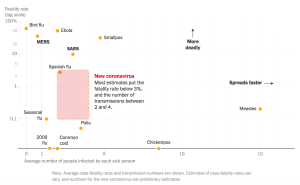

The large area indicated for the potential mortality rate of the novel coronavirus is an example of the uncertainty this virus presents

We don’t really know what the mortality rate is for the coronavirus because we don’t actually know how many people have it. Further, ever were we to know what the mortality rate was, could we be absolutely sure that we wouldn’t be among those it encompassed?

See, the main difference between the novel coronavirus and the flu is not any feature of either virus or disease. The main differences is a lack of familiarity with the novel coronavirus. The flu is familiar. Yes, people die of the flu. But we know that. We factor it in to our regular lives. We decided to get flu shots (or not) based on the odds we think we are facing.

But we don’t know this new virus. We don’t really know what it’s doing. And that creates uncertainty. And uncertainty creates unease. Especially when it revolves around questions of mortality:

Some psychologists maintain that practically everything we do is a kind of resistance in reaction to our awareness of our mortality. This terror management theory posits that our desire for self-preservation coupled with our cognitive awareness of our inevitable deaths leads to a “terror” that can only be mitigated in two ways. First, we mitigate this terror with self-esteem—the belief that each of us is an object of primary value in a meaningful universe. Second, we mitigate our terror by placing a good deal of faith in our cultural worldview. The faith we put in a cultural worldview gives us a feeling of calm in the midst of dread. Our commitment to an understanding of the world around us makes us feel safe and secure in the face of our looming mortality.

However, when those same worldviews are threatened, so too is that feeling of calm. For that reason, we have to defend our worldviews at all cost because they protect us from facing the terror of our mortal lives. Preserving our worldviews is so central to staving off our existential dread that it turns out that the more we think about death and oblivion, the more invested we become in preserving those worldviews.

It seems that one of our preferred methods of defending our worldviews and fending off this core terror is the attempt to establish as many certainties as possible, to know that there is something we can be certain of. In an effort to deny our mortality and the recognition that we are not ultimately in control of our own destinies, we try to control our world and one another and we seek to cling to as many certain truths as we can along the way.

—The Certainty of Uncertainty, p. 4

This explains both the toilet-paper hoarders and the people crowding bars and restaurants: each is trying to demonstrate some control over their environment in the midst of uncertainty. Each is trying to say, ultimately, “I’m in control of my life and my destiny, not some random virus!” But then each is prone to making a costly error: in the former, denying others resources by one’s own hoarding; in the second, contributing to the spread of contagion.

In the end, there are really only two ways to combat uncertainty: (1) by the acquisition of more, reliable data, such as that being shared by respected public health officials where such data exists, and (2) by living faithfully with hope. We don’t know whether we as individuals will contract the disease, and we don’t know what will happen to us with certainty if we do. But we can live our lives not out of fear of uncertainty, but by acknowledging our uncertainty and living prudently in the meantime, neither panicking nor engaging in reckless behavior.

In the end, it will likely be our fear of uncertainty that will take a greater toll on us than the virus would have on its own. If we do not name that uncertainty and own it, our fear of it will continue to take that toll on us.

The best we can do in the meantime, then, is to acknowledge our unknowing, learn what we can, behave prudently, and take care of one another, even if that care is at a distance. And, of course, wash our hands.

June 24, 2019

You Have Permission…

…to listen to a great podcast.

Mark Schaefer appeared on Dan Koch’s excellent podcast You Have Permission, a podcast for anyone asking those deep and timeless questions that humans can’t seem to stop asking. Dan wants to make clear that you have permission to take both Christianity and the modern world very seriously, and hopes to facilitate that by introducing you to people seeking God across the whole Christian spectrum, engaging these hard questions in a multitude of ways.

Mark Schaefer appeared on Dan Koch’s excellent podcast You Have Permission, a podcast for anyone asking those deep and timeless questions that humans can’t seem to stop asking. Dan wants to make clear that you have permission to take both Christianity and the modern world very seriously, and hopes to facilitate that by introducing you to people seeking God across the whole Christian spectrum, engaging these hard questions in a multitude of ways.

Dan and Mark talked about faith, doubt, our need for closure and certainty, and the importance of embracing uncertainty in faith.

December 29, 2018

When What You Say Isn’t What You Mean

One of the main sources of uncertainty in our lives is the medium we use to communicate about that world: our language. There are many pitfalls to clear communication among which is the problem of implied meaning and subtext. Below is an excerpt from a chapter of The Certainty of Uncertainty entitled “The Slipperiness of Language” reflecting on this very point:

Implied Meaning and Subtext

As I sit here writing this chapter, there is a young college student across the table. It’s that time of year when colds are making their rounds and this young man is sniffling. Repeatedly. I reach into my bag and pull out one of those travel packets of tissues. “You need a Kleenex?” I ask him. “No, thanks. I’m good,” he responds. He has misunderstood my statement; it wasn’t a question. It was a face-saving declaration to him that he needed a Kleenex. He understood the text of my question but neither the subtext (your constant sniffling is driving me crazy) nor the implied meaning (please blow your nose).

This kind of miscommunication happens all the time, and the difference in the perception of a subtext between two speakers can make the dynamics of conversation very different. Consider these two different exchanges:

1.

Alex: What are you doing tonight?

Pat: I’m going to the movies with my friend Chris.

Alex: That sounds like fun.

2.

Alex: What are you doing tonight?

Pat: Nothing. Probably just sitting around and watching TV.

Alex: (Dejectedly) Oh.

In the first example, there is little subtext other than Alex’s interest in information. When the information is received, Alex feels satisfied. In the second example, Alex is disappointed with this exchange, even though, on its sur- face, the question is identical to the one in the first example. In theory, Alex should feel the same satisfaction felt in the first example.

However, as you’ve probably already figured out, the question “What are you doing tonight?” was not a request for information in the second case. It was a prompt for invitation and, unlike a neutral request for information, this question has a right answer. The question really means “Why don’t we do something tonight if you’re not busy?” and the exchange is expected to go like this:

Alex: What are you doing tonight?

Pat: Nothing. Why don’t we go get some dinner and see a movie?

Alex: That would be great.

This is a satisfactory exchange from Alex’s point of view because the implied meaning of the question has been addressed. Individuals get into trouble when they fail to perceive the hidden question behind the question, as did a former student of mine who upon being asked to “come over and see” the new apartment of a female friend, did exactly that: he went over, looked around, commented approvingly, and left. He did not, as his friend expect- ed, hang out, stay for dinner, watch a movie, and then go home. He wound up in the doghouse for a few days—never understanding why.

Sometimes, the error lies in imagining there to be an implied meaning that isn’t there. That too happens all the time, occasionally with dire consequences.

In the middle of the twelfth century, Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury, found himself in a feud with the reigning king of England, Henry II. After serving a brief time in exile abroad, Becket returned to England at the king’s invitation. After his return, he excommunicated a bishop loyal to the king. Frustrated, Henry stalked the halls of his palace and lamented out loud. According to one tradition, he said, “Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” [8] Or, according to other historians, “What miser- able drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric.” [9] In either case, a group of knights understood the king’s ranting to be giving them a command and immediately rode to Canterbury, where they brutally and very publicly murdered Becket in the cathedral. In this instance, the knights interpreted the king’s statement as having an implied meaning: go kill the archbishop.

In the middle of the twelfth century, Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury, found himself in a feud with the reigning king of England, Henry II. After serving a brief time in exile abroad, Becket returned to England at the king’s invitation. After his return, he excommunicated a bishop loyal to the king. Frustrated, Henry stalked the halls of his palace and lamented out loud. According to one tradition, he said, “Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” [8] Or, according to other historians, “What miser- able drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric.” [9] In either case, a group of knights understood the king’s ranting to be giving them a command and immediately rode to Canterbury, where they brutally and very publicly murdered Becket in the cathedral. In this instance, the knights interpreted the king’s statement as having an implied meaning: go kill the archbishop.

The question of subtext and implied meaning is present in another very common kind of speech: indirect speech. In an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, Larry David and his wife, Cheryl, have gone to an exclusive restaurant where the wait for a table is nearly an hour. Larry approaches the maître d’:

Larry: I’m curious; about how long is the wait?

Maître d’: I’m afraid it looks like forty-five minutes to an hour.

Larry: Forty-five minutes . . . no way to get in—

Maître d’: No, we’re very crowded this evening, sir.

Larry: Nothing else can be done?

Maître d’: Nothing that I can think of, sir.

Larry: Things are done, right? I hear things are done.

Maître d’: From time to time.

Larry: (Surreptitiously sliding his palm across the host stand and dropping something in the maître d’s hand) Anything you can do…

Maître d’: Actually, I think we can accommodate you right now. Would you like to follow me? [10]

The entire content of this conversation is taking place on an indirect, im- plied level. Larry does not approach the maître d’ and ask whether he can bribe him for a table. Nor does the maître d’ ever directly suggest that he try. [11] The reasons for indirect speech are complex and frequently involve all manner of social implications, particularly the desire for all parties involved to save face. [12] What is clear is that there are not only utterances that depend on reading the subtext, there are also entire conversations that require careful attention to subtext and implied meaning. Misunderstanding can occur when one party or the other to a conversation is oblivious to the implied subtext or supplies subtext when none exists.

Notes

8. Ibeji, “Becket, the Church and Henry II.”

9. Caris, “10 Tiny Miscommunications.”

10. Gordon, “Affirmative Action.”

11. It turns out in any event that Larry slipped the maître d’ his wife’s prescription for skin cream, rather than the $20 bill he had stashed in the same pocket.

12. Pinker, Language, Cognition, 304.