Kevin Patrick's Blog

January 6, 2022

Norman Clifford's Aerial Adventures

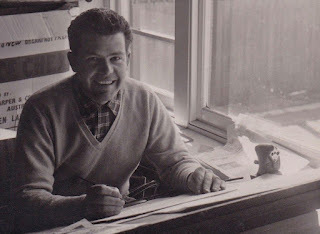

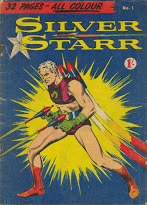

Above: Norman Clifford, Melbourne 1959Norman Clifford was one of many talented and enterprising Australian artists who created opportunities for themselves in a competitive comic book market in the 1950s by creating stories which resonated with local audiences, and stood out among the American and British comics which crowded newsagents' shelves at the time. His passion for aircraft and aviation history inspired him to create a string of successful air combat-themed comics that capitalised on the Royal Australian Air Force's then-current involvement in Korean War (1950-53), and the postwar fascination with breakthroughs in aviation technology.

Above: Norman Clifford, Melbourne 1959Norman Clifford was one of many talented and enterprising Australian artists who created opportunities for themselves in a competitive comic book market in the 1950s by creating stories which resonated with local audiences, and stood out among the American and British comics which crowded newsagents' shelves at the time. His passion for aircraft and aviation history inspired him to create a string of successful air combat-themed comics that capitalised on the Royal Australian Air Force's then-current involvement in Korean War (1950-53), and the postwar fascination with breakthroughs in aviation technology.The following is Norman's own recollections of this exciting early phase in his decades-long career as a cartoonist and commercial artist. It is reprinted here by arrangement with his daughter, Vicki Sach (editor and journalist at OneHorse Media). Unless otherwise indicated, all images are taken from the official Facebook page for Norman Clifford Aviation Artist (Special thanks to Jeff Batista for originally sharing the following material via the Facebook page for Old Australian Pre-Decimal Comics up to 1966).

- Kevin Patrick

Born in Footscray in 1927, Norman Clifford attended Tottenham State School. He completed one year of a three-year art course at RMIT before deciding to quit.

He worked at the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) at Fisherman’s Bend for three years, assembling Boomerang and Mustang airplanes.

Above: Norman Clifford (third from right) on the CAC "Boomerang" assembly, circa late 1940s

Above: Norman Clifford (third from right) on the CAC "Boomerang" assembly, circa late 1940s

He applied to train as a pilot with the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), but the CAC wouldn’t release him (and he also failed the arithmetic part of assessment!)

He grew up devouring comics and developing his talent as a self-taught artist, focusing mostly on airplanes, finally illustrating a full-length comic which he pitched to Southdown Press. He drew the artwork…making the story up as he went…with his new bride, Shirley doing all the speech lettering.

The comics were a huge success, their relevant war topic and military aviation theme capturing public’s imagination, with their sales eclipsing the popular Disney and Marvel comics of the time.

Norman Clifford recalls …

When I was 24 years old and with no qualifications, line drawings were about all I could do, but at that stage they still lacked light and shade. I knew nothing about printing and very little about design.

I started work with John Warlow, who ran a photographic studio in Collins Street. His staple was weddings, but he did everything from portraits to industrial photography. It was there I learned all aspects of photography…developing, printing, retouching and print colouring, done in an era before colour photos (Note: The Melbourne Argus newspaper published an interview with John Warlow about amateur photography in August 1953, which can be viewed here).

Above: John Warlow, 1953Warlow’s studio had an area large enough to photograph complete wedding parties or anything else requiring specific lighting. Clients came up by lift and entered the waiting room.

Above: John Warlow, 1953Warlow’s studio had an area large enough to photograph complete wedding parties or anything else requiring specific lighting. Clients came up by lift and entered the waiting room.

I hand coloured large photographic prints for Trans Australian Airlines (TAA) and mine were better than the other girls employed there because I knew the civil transport aircraft…the white roofs, natural metal and reflected light. I changed the TAA hand lettering to blue with a black outline, and coloured the concrete tarmac a light shade of fawn.

John Warlow nearly had a fit when he saw the contrast between my work to the girls, and was within an ace of having them redone but the TAA rep loved them!

It was an interesting place to work but my heart was still firmly fixated on comic books. I liked reading but the comics always interested me more because they were illustrated stories.

Could I do one?

Maybe.

------

I’d already had three goes, but conked out when I reached the limits of my ability.

Was I up to attempting a fourth? After all, they were only illustrated stories!

So away I went. When it came accurately drawing characters, I knew enough about cameras and film developing to ask friends to model the characters’ poses for me, which I then drew into the artwork.

My room at home was a combination of bedroom and art studio, while the family washhouse my darkroom. My parents were very patient, but my brothers thought it resembled a dump.

I slaved away, working at Warlows during the day, and on my art in the evenings and weekends (when I wasn’t doing Saturday weddings).

195I was a key year for me.

------

Working from my bedroom/studio, I created complete art for a 24-page comic book containing two action stories: Korea, and an air racing epic titled Speed Demons.

Working from my bedroom/studio, I created complete art for a 24-page comic book containing two action stories: Korea, and an air racing epic titled Speed Demons.

In both stories, airplanes featured as much as the cast. The artwork was a bit rough around the edges, but I offered it to Southdown Press [publisher of New Idea] in North Melbourne.

There were very few comic books that featured airplanes and those that did were done in typical American style with the flying secondary to the action. Mine were just the opposite… airplanes were the main focus with human characters a distant second. I didn’t know any other way to do it!

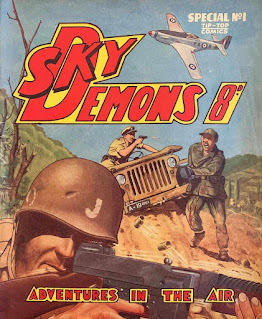

I was surprised when Bill Bednall from Southdown Press took it up with the only request being that the title be changed from “The Air Strip” to “Sky Demons”.

I was proud of “The Air Strip” title, which I thought was a rather clever play on words with air landing strip/comic strip. But Bill and his sales chief wanted something more flamboyant and outranked me. And so it was that “Sky Demons” was added to Southdown Press library under their ‘Tip Top Comics’ banner.

Bill Bednall had been a journalist in his younger days and wrote a spirited foreword for the No.1 Special, adding a few flourishes to jazz it up a bit. For example:

“Great pains have been taken by the artists to ensure that technical details are as accurate as can be…” and “…the artists are well versed in flying.”

That was a laugh, there was only me!

My work was based more on enthusiasm than anything else.

American comic books were in every newspaper shop and mine looked a bit rustic by comparison.

Sky Demons came to life on Southdown’s big flatbed printing press, and I heard nothing more about it while it was being distributed to newsagents Australia-wide.

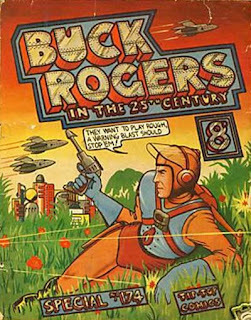

During this era, television was still in the distant future and comic books were a popular form of entertainment. Over 100 titles were distributed monthly but very few were Australian and none exclusively featured airplanes. Hot competition from other sources included Micky Mouse, Donald Duck, Captain Marvel, Red Ryder, Hurricane Hawk, Buck Rogers and many others. If I’d done mine with this competition in mind I mightn’t have even started! I was completely naïve, and it shows in every illustration.

------

After Sky Demons had been distributed for a while, Bill called me in to Southdown Press to share some sales details. He revealed that my one comic effort had out-sold everything on the market, including Disney and Marvel Comics.

It was hard to believe!

Did my singular effort win on artistic merit?

I think there’s a few factors to consider: The story line, action and reasonably drawn adventure about airplanes (No. 77 Squadron, RAAF) and above all, pilots fighting in the Korean War was a topical subject.

As a beginner artist, I’d kicked a goal.

The Australian Mustang flying pilot hero ‘model’ in the first story was none other than my boss, John Warlow. In real life he was a portly photographer.

The story lines were mostly plotted on the go… in other words, I drew panels as I made up the story (which fortunately concluded at the finish-line!) I didn’t know you were supposed write the story, then do a storyboard to guide the layout. I didn’t even know what a storyboard was!

I knew nothing about the American technique for creating comics, which was to have a trio of writers, artists and speech letterers working on the strips.

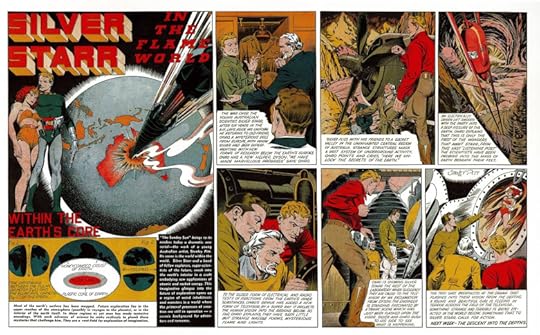

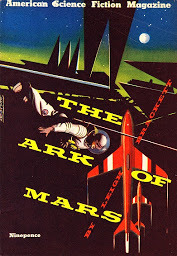

Most of my comics waved the airplane flag against a backdrop of Europe and the Southwest Pacific… the Allies against enemy. Just to be different, one story was on air racing, while another was about a flying circus. Two of six comics I drew were a space fantasy.

The first comic, Sky Demons, smacked of inexperience but I gave it my all and the aircraft depicted were as accurate as I could draw them. When I compare my first comic to my last, I can see a vast difference between them, a change fired by my enthusiasm and experience.

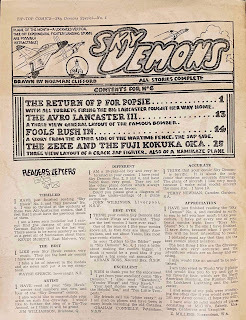

Above: Readers' Letters, Sky Demons, no.6Bill and his sales chief thought they had struck gold… a local artist with the right touch.

Above: Readers' Letters, Sky Demons, no.6Bill and his sales chief thought they had struck gold… a local artist with the right touch.I was amazed at the success, but quickly recovered when they paid me £100 and the prospect of more comics (and money) to come.

------

Back in my early days with Southdown Press, Bill would occasionally mention the number of letters rolling in applauding my strips. He’d scratch his head and mutter that it was the first time in his experience, that readers had ever been moved to write to the publisher about comic material. Their new ‘local artist’ reeled in surprise… even my own family (who weren’t the least bit interested in aviation) couldn’t figure out how I’d done it!

------

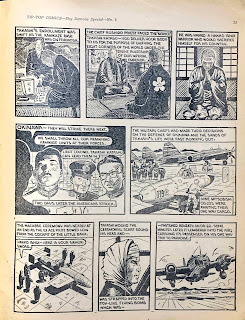

Above: 'Fools Rush In' (Excerpt)One boy who liked aeroplanes as much as I did was Ian Baker, who was so impressed, he kept a particular story called “Fools Rush In” from Sky Demons No 6.

Above: 'Fools Rush In' (Excerpt)One boy who liked aeroplanes as much as I did was Ian Baker, who was so impressed, he kept a particular story called “Fools Rush In” from Sky Demons No 6.

The storyline depicted a Japanese fighter pilot fresh from his graduation, bidding farewell to his beloved 'kanojou' (girlfriend) before leaving for the South-Eastern Pacific Theatre of war to fight against American and Australian air forces. When American’s bombed Japan and his lady friend was killed, he volunteered for duty as a kamikaze pilot and was one of many who flew a one man powered rocket, ‘Baka’, against advancing American aircraft carriers. He, too, was killed. Baka, the name given the rocket, meant ‘fool’…hence “Fools Rush In” to their death.

Ian went on to become a member of the Australian Society of Australian Artists (ASAA) and sent me an eleven-page photocopy extract of this story. His personal comment is embarrassing (but nice!) to read:

“In contrast to tedious repetitiveness of comic book super-heroes, Norm’s work embodied an intrinsic honesty in its approach”.

I wish I had known that when I was creating my comics, because the truth is that as a relative newcomer, I always felt I was making a fool of myself!

------

One morning the Warlow Studio staff were on a tea break in the colourist room when in walked a young girl recently employed as a wedding print colourist. He introduced her to everyone including me… and I was smitten. She was nearly 18 years old and dressed for summer in a sleeveless pale blue dress, nicely styled hair, pretty sun-tanned face, arms and shoulders.

Her name was Shirley, and we were married 12 months later.

Early on in our marriage, I was working from an ancient holiday house at the foot of Arthurs Seat in Dromana. To get to Southdown Press and with my wares under my arm, I had to either catch a bus to Frankston, then the train to Melbourne, or thumb a ride.

I converted one room into my ‘studio’, installed all my books and drawing equipment and set about creating comics.

Covers were in colour but inside pages were black and white. Strangely enough, working exclusively in black outline shading made for steady and controlled rendering of the story illustration later, but one thing I discovered…I was a dud at speech lettering! It was the Achilles heel of my comic career.

Shirley got sick of me complaining about it and volunteered to have a go. Shock and surprise, her rendering of the words was unbelievably good from the outset… neat and clean… she reckoned it was easy! She wasn’t an artist (although could have been) her lettering was very nearly typeset standard. She was a natural.

------

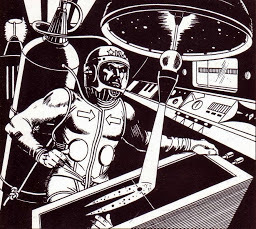

While all my this was going on, Southdown Press informed me they had rights to post-war Buck Rogers material, minus covers and Bill Bednall gave me the job of doing about five colour Buck Rogers covers. I’d been reading Buck Rogers since I was a kid, so I was thrilled to be doing it for the money AND the privilege!

Above: Cover art by Norman CliffordHowever, pressure was mounting and the incessant application to continually produce artwork for my storylines was starting to tell, but they represented my bread and butter so there wasn’t much I could do but hang in there.

Above: Cover art by Norman CliffordHowever, pressure was mounting and the incessant application to continually produce artwork for my storylines was starting to tell, but they represented my bread and butter so there wasn’t much I could do but hang in there.

Then the worst happened… TELEVISION!

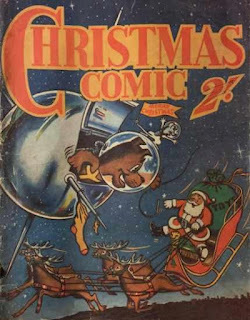

TV entered the scene [in 1956] and almost overnight the bottom dropped out of Australian and American comic sales. Southdown Press needed to keep the presses rolling and Bill Bednall didn’t want to give up without a fight. He decided to scrap further issues of Sky Demons and asked me to do my comics under individual titles, so I dreamt up various comics; Daredevil Comics, Wonder Wings, Billy Battle, Thrilling Space Adventures, and… with a last roll of the dice… the Christmas Comic, featuring a coloured cover depicting the Russian space dog ‘Sputnik’ circling the world.

Above: Christmas Comic, 1958Comic prices dropped to sixpence and finally the last few issue covers were reduced from full colour to two-colour to save money. But with moving pictures now in many lounge rooms, television won out. All the new Southdown titles were scrapped and sadly, so was I, leaving me wondering where my next quid was coming from.

Above: Christmas Comic, 1958Comic prices dropped to sixpence and finally the last few issue covers were reduced from full colour to two-colour to save money. But with moving pictures now in many lounge rooms, television won out. All the new Southdown titles were scrapped and sadly, so was I, leaving me wondering where my next quid was coming from.------

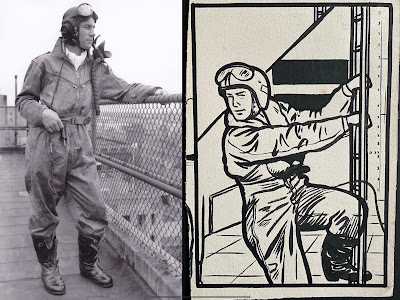

One of the friends I asked to model for me was my best mate, Mike Dunbar.

To my delight, he’d joined the air force and was in 3rd Course (1950-53) at the RAAF College, Point Cook. I was envious of [him], but had to be content with drawing the flying machine rather than actually flying them. Mike thought it was a great joke and quite an achievement to make the grade turning out comics.

After the success of Sky Demons No. 1 and anticipating further comics, I [sought] assistance from Cadet Mike. Some of his 3rd Course Cadet friends would visit me in uniform at the Warlow Studio on their Saturday off and we’d visit a coffee shop, exhibition, or anything else worth looking at around Melbourne on a Saturday.

I already had a Type C leather flying helmet from a disposal store, but asked Mike another RAAF College Cadet, Ron Green, 4th Course, if they could possibly scrounge a loan of a flight overall and flying boots and bring them on a Saturday visit as I wanted to know what gear a pilot wore. They obliged and I photographed them in costume on the roof of Howey Place Arcade in Collins Street.

Above: Mike Dunbar (left) posing in RAAF flight gearI’d kept in touch with Mike right up to the time he graduated, gained his wings and after a tour with 77 Squadron, RAAF, in Korea, he was posted abroad for a three-year stint in Germany with the Royal Air Force, then back to RAAF Base East Sale for duties as instructor in the early-sixties.

Above: Mike Dunbar (left) posing in RAAF flight gearI’d kept in touch with Mike right up to the time he graduated, gained his wings and after a tour with 77 Squadron, RAAF, in Korea, he was posted abroad for a three-year stint in Germany with the Royal Air Force, then back to RAAF Base East Sale for duties as instructor in the early-sixties.We were great friends, and I asked him to be godfather to my son, also named Michael.

I'd been with the agency for four years when in 1962, Flight Lieutenant Michael Dunbar was killed in a terrible accent that wiped out four Vampire T33 two-seat trainers at the RAAF base in East Sale.

They were rehearsing as part of the “Red Sales” aerobatic team when they crashed, killing all four pilots and two crew members. It was a terrible shock, and I was unable to go to work the next day.

Notes from Vicki Sach: (Daughter of Norm Clifford)

After his career as a comic artist ground to a halt and with a young family to support, Norm began work as a commercial artist (known these days as a graphic designer). This was during an era when all products for print advertising were illustrated by hand. He worked for major Melbourne advertising agencies before going freelance, setting up his drawing board in the lounge room of the family home in Glen Waverley during the 1970’s.

One of his first major freelance jobs was as advertising illustrator for the first Kmart store to open in Melbourne, located in Burwood.

Military aviation remained his passion, and he became known for his accuracy and attention to detail when it came to illustrating vintage aircraft. He was asked to work for the Aviation Safety Digest, and was commissioned to illustrate multiple magazine and book covers as well as air show posters.

Above: Norman Clifford (left) in his studio, 1988In 1995, he was commissioned by Australia Post to paint a series of Australian military aviation stamps.

Above: Norman Clifford (left) in his studio, 1988In 1995, he was commissioned by Australia Post to paint a series of Australian military aviation stamps.

He completed many commissioned paintings for the RAAF and his artwork can be found at the Point Cook museum, Australian air bases, the Australian War Memorial and in many private and corporate collections world-wide.

He was obsessed with authenticity…his airplanes had to be as accurate as he could possibly paint them! Ditto pilots and personnel, and he would frequently dress his long-suffering family in vintage RAAF gear and photograph them in his back yard to use for painting reference. If he couldn’t buy or borrow what he needed, he would source specifications and make it himself, once mocking up two life-size machine guns made from wood, just so he could photograph a family member dressed in full WW1 pilot gear complete with helmet and goggles, sitting on a kitchen chair taking “aim” at the enemy.

Now 93 years old, Norm is no longer able to paint after a minor stroke left him with balance issues. But his passion for all things military aviation remains as strong as ever!

The following images were sourced from these websites: Photo of John Warlow (Trove-National Library of Australia); Buck Rogers in the 25th Century Special, no.174 & Christmas Comic (AusReprints); Sky Demons Special, no.1 & excerpt from 'Fools Rush In' (Old Australian Pre-Decimal Comics up to 1966/Facebook). All other images from Norman Clifford Aviation Artist and/or courtesy of Vicki Sach/One Horse Media)

October 2, 2021

Antipodean Currents: Comic Art in Australia and New Zealand (Part 2)

I originally wrote 'Antipodean Currents' in 2016, after being commissioned to write a brief "layman's history" of comic art in Australian and New Zealand from the late 19th century to the present day. It was originally intended for an academic essay collection, but the project was eventually cancelled, and it never saw print. I subsequently made an illustrated PDF version of this essay available on my Academia page, but this was only available to Academia.edu subscribers. As I've had numerous academics and comic fans/historians ask me to send them copies over the years, I've decided to publish it over several instalments on the Comics Down Under blog and make it available to a wider audience (You can read the first instalment here)

I hope you'll enjoy reading the second installment of "Antipodean Currents".

- Kevin Patrick

Comic Strips and the Popular Press

Fig.1When Great Britain granted political independence to the newly proclaimed Commonwealth of Australia in 1901, there followed an outpouring of patriotic magazines, some of which made extensive use of cartoons and comic strips to comment on the vices and virtues of the young nation. Chief amongst these was The Comic Australian (1911-1913), the first magazine to print coloured comic strips illustrated by Australian artists. Oddly enough, it was the poet Hugh McCrae (1876-1958), who drew a pioneering series of comic strips for the magazine, featuring a bushland retinue of kangaroos and koalas, which made the then-innovative use of speech balloons enclosed within formally separated panels (Figure 1) (Note #1). The adoption of Australia’s exotic fauna as anthropomorphic characters would become a recurring motif in Australian comics from this period onwards.

Fig.1When Great Britain granted political independence to the newly proclaimed Commonwealth of Australia in 1901, there followed an outpouring of patriotic magazines, some of which made extensive use of cartoons and comic strips to comment on the vices and virtues of the young nation. Chief amongst these was The Comic Australian (1911-1913), the first magazine to print coloured comic strips illustrated by Australian artists. Oddly enough, it was the poet Hugh McCrae (1876-1958), who drew a pioneering series of comic strips for the magazine, featuring a bushland retinue of kangaroos and koalas, which made the then-innovative use of speech balloons enclosed within formally separated panels (Figure 1) (Note #1). The adoption of Australia’s exotic fauna as anthropomorphic characters would become a recurring motif in Australian comics from this period onwards.The growth of Australia’s suburbs throughout the 1920s, serviced by public transport networks, created a new commuter audience for newspapers and periodicals (Note #2). Newspapers became a more visual medium, subscribing to what historian K.S. Inglis called the ‘law of increasing brightness’, whereby ‘the headlines [grew] higher …the display advertisements more seductive … [and] the photographs larger and more vivid’ (Note #3). Comic strips stood poised to become a vital component in newspapers’ growing emphasis on graphic design and layout, yet some Australian newspapers were slow to embrace the medium. Sydney’s Sunday Times, a self-styled “family newspaper”, published Australia’s first comic-strip supplement for children on 14 August 1921 (Note #4). The austere and conservative Sydney Morning Herald, however, steadfastly refused to print any comic strips until 1945, when it published C.S. Gould’s comic-strip canine, Shaggy (Note #5).

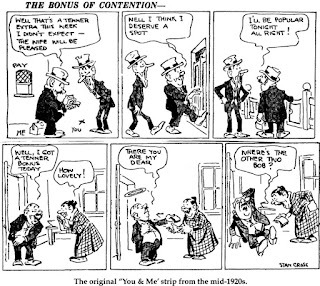

Fig.2Smith's Weekly was a staunchly nationalistic newspaper which traded on its working-class appeal and boasted an impressive roster of cartoonists whose work was considered a cornerstone of the newspaper’s popularity throughout the 1920s (Note #6). Their leading cartoonist was the American-born Stan Cross (1888-1977), who was given samples of the American comic strip, The Gumps, and instructed to devise a similar feature for Smith’s Weekly. Cross responded with You & Me, which became Australia’s first weekly newspaper comic strip upon its debut in August 1920 (Fig.2). The series focused on the portly Mr Pott and his lanky mate, “Whalesteeth”, whose barroom bonhomie frequently degenerated into violent arguments over politics, religion, and other topical issues. Cross ably transferred the domestic situation-comedy premise of The Gumps to a recognisably Australian setting, filtered through a distinctive “Aussie” vernacular, which saw the strip become a mainstay of Smith’s Weekly for twenty years.

Fig.2Smith's Weekly was a staunchly nationalistic newspaper which traded on its working-class appeal and boasted an impressive roster of cartoonists whose work was considered a cornerstone of the newspaper’s popularity throughout the 1920s (Note #6). Their leading cartoonist was the American-born Stan Cross (1888-1977), who was given samples of the American comic strip, The Gumps, and instructed to devise a similar feature for Smith’s Weekly. Cross responded with You & Me, which became Australia’s first weekly newspaper comic strip upon its debut in August 1920 (Fig.2). The series focused on the portly Mr Pott and his lanky mate, “Whalesteeth”, whose barroom bonhomie frequently degenerated into violent arguments over politics, religion, and other topical issues. Cross ably transferred the domestic situation-comedy premise of The Gumps to a recognisably Australian setting, filtered through a distinctive “Aussie” vernacular, which saw the strip become a mainstay of Smith’s Weekly for twenty years.

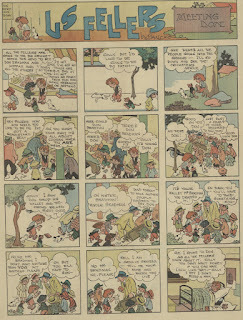

Fig.3It took a red-haired urchin named Ginger Meggs to prove beyond doubt comic strips’ potential value to Australian newspapers. Ginger Meggs was a minor character in Us Fellers, created by James Bancks (1889-1952) for Sydney’s Sunday Sun in November 1921. Meggs, who shirked homework in favour of racing billycarts and getting into fights, gradually became the leading character. Us Fellers (subsequently renamed

Ginger Meggs

) captured the everyday argot of Australian children, but its successful placement with newspapers in Britain, Europe, and the United States during the 1920s suggested that the series’ appeal was universal (Fig.3). Ginger Meggs became the undisputed star of Australian comics, appearing in the annual Sunbeams Book series (1924-1951), and on cinema screens in Those Terrible Twins (1925) (Note #7).

Fig.3It took a red-haired urchin named Ginger Meggs to prove beyond doubt comic strips’ potential value to Australian newspapers. Ginger Meggs was a minor character in Us Fellers, created by James Bancks (1889-1952) for Sydney’s Sunday Sun in November 1921. Meggs, who shirked homework in favour of racing billycarts and getting into fights, gradually became the leading character. Us Fellers (subsequently renamed

Ginger Meggs

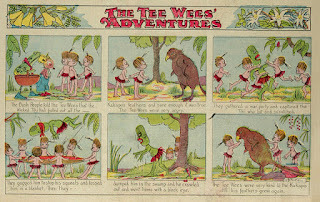

) captured the everyday argot of Australian children, but its successful placement with newspapers in Britain, Europe, and the United States during the 1920s suggested that the series’ appeal was universal (Fig.3). Ginger Meggs became the undisputed star of Australian comics, appearing in the annual Sunbeams Book series (1924-1951), and on cinema screens in Those Terrible Twins (1925) (Note #7).In 1927, the Auckland Star published one of New Zealand’s first comic strips, The Tee Wees’ Adventures, a charming “bush fairy” serial by D. Price (Fig.4). This was followed in the early 1930s by two comparable series, each illustrated by female artists: Jocelyn Harrison-Smith’s Ngaio and her Magic Paddle and Avis Acres’ The Adventures of Tink and Wink, the Star Babies (Note #8). Their frequent use of Maori language and iconography demonstrated how Australasian cartoonists frequently drew on indigenous cultures to differentiate their work from British and American comic strips.

Fig.4

Fig.4

New Zealand’s relatively small publishing industry forced many local cartoonists to cross the Tasman Sea to Australia in search of work, where some would make an indelible contribution to Australian comics throughout the 1920s and 1930s. One notable expatriate artist was Noel Cook (1896-1980), who drew cartoons for the New Zealand Observer, before migrating to Sydney, where he contributed illustrations to The Bulletin and Smith’s Weekly. In 1923, Cook produced Peter and all the Roving Folk for Sydney’s Sunday Times, considered by some to be the world’s first science-fiction comic strip (Note #9).

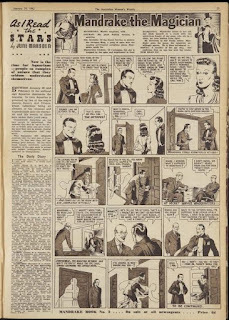

Fig.5Women’s magazines played a pivotal role in cultivating the public’s taste for adventure-serial comic strips.

The Australian Women's Weekly

unveiled a new American series, Mandrake the Magician, in December 1934 (Fig.5).

The Australian Woman’s Mirror

followed suit with its equivalent American comic-strip hero, The Phantom, in September 1936. Both series, created by author Lee Falk (1911-1999), were sold throughout Australasia by the Sydney-based Yaffa Syndicate, which, as the regional representative for King Features Syndicate (US), offered back-dated American comic strips to local clients at artificially low prices (The company sold Mandrake the Magician to the Women’s Weekly for just A£5.00 per full-page episode) (Note #10). Coupled with the perceived dearth of equivalent local content, this pricing strategy allowed American comic strips to gradually dominate the Australasian newspaper market by the late 1930s.

Fig.5Women’s magazines played a pivotal role in cultivating the public’s taste for adventure-serial comic strips.

The Australian Women's Weekly

unveiled a new American series, Mandrake the Magician, in December 1934 (Fig.5).

The Australian Woman’s Mirror

followed suit with its equivalent American comic-strip hero, The Phantom, in September 1936. Both series, created by author Lee Falk (1911-1999), were sold throughout Australasia by the Sydney-based Yaffa Syndicate, which, as the regional representative for King Features Syndicate (US), offered back-dated American comic strips to local clients at artificially low prices (The company sold Mandrake the Magician to the Women’s Weekly for just A£5.00 per full-page episode) (Note #10). Coupled with the perceived dearth of equivalent local content, this pricing strategy allowed American comic strips to gradually dominate the Australasian newspaper market by the late 1930s.To be continued in 'Antipodean Currents', Part 3

Image Sources: Fig.1: (Pikitia Press) ; Fig.2: (The LaTrobe Journal); Fig.3: (20th Century Danny Boy); Fig.4: (From Earth's End); Fig.5: (Trove/National Library of Australia, via Pinterest)

Note #1: John Ryan, Panel by Panel: A History of Australian Comics (Stanmore, NSW: Cassell Australia, 1979), p.13.

Note #2: Ian Gordon, ‘From The Bulletin to Comics: Comic Art in Australia 1890-1950’, Bonzer: Australian Comics 1900-1990s, Annette Shiell, Ed. (Redhill South, VIC: Elgua Media, 1998), pp.2-3.

Note #3: K.S Inglis, ‘The Daily Papers’, Australian Civilization: A Symposium, Peter Coleman, Ed. (Melbourne: F.W. Cheshire, 1962), p.152.

Note #4: R.B. Walker, Yesterday’s News: A History of the Newspaper Press in New South Wales from 1920 to 1945 (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 1980), p.36.

Note #5: Ryan, Panel by Panel, p.57

Note #6: George Blaikie, Remember Smith’s Weekly? (Adelaide: Rigby Limited, 1966), pp.3, 55.

Note #7: Lindsay Foyle, The Most Important Boy in Australia: 75 Years of Ginger Meggs (Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Black & White Artists’ Club).

Note #8: Adrian Kinnaird, From Earth’s End: The Best of New Zealand Comics (Auckland: Godwit Books/Random House New Zealand, 2013), p.13.

Note #9: Tim Bollinger, ‘Comics and Graphic Novels – Early Years of Comics, 1900s to 1940s’, Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand (4 March 2014) .

Note #10: Denis O’Brien, The Weekly (Ringwood, VIC: Penguin Books Australia, 1982), p.55.

June 3, 2021

Antipodean Currents: Comic Art in Australia and New Zealand (Part 1)

I originally wrote 'Antipodean Currents' in 2016, after being commissioned to write a brief "layman's history" of comic art in Australian and New Zealand from the late 19th century to the present day. It was originally intended for an academic essay collection, but the project was eventually cancelled, and it never saw print. I subsequently made an illustrated PDF version of this essay available on my Academia.edu page, but this was only available to Academia.edu subscribers. As I've had numerous academics and comic fans/historians ask me to send them copies over the years, I've decided to publish it over several installments on the Comics Down Under blog and make it available to a wider audience.

I hope you'll enjoy reading the first installment of "Antipodean Currents".

- Kevin Patrick

Introduction

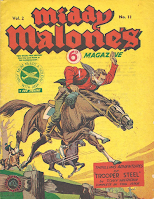

In 1949, the Australian cartoonist Syd Nicholls (1896-1977) exhorted booksellers and newsagents to ‘give preference’ to his company’s range of ‘all-Australian comics’. Nicholls’ publications, including Middy Malone’s Magazine (Fig.1) and Fatty Finn’s Comic, were, he claimed, ‘clean, wholesome books free from foreign slang and idiom … written and produced by Australian craftsmen’ (Note #1). Nicholls’ plea distilled the considerable challenges that confronted generations of cartoonists from Australian and New Zealand, who have strived to create distinctively “antipodean” comic strips and comic magazines, often in the face of overwhelming competition from their foreign counterparts. Figure 1

Figure 1Despite being situated on the geographic periphery of international comics culture, Australia and New Zealand have been historically exposed to first British, then American traditions and trends in comic art. The cultural and economic dominance of Anglo-American comics was achieved through the widespread circulation of imported comic magazines and syndicated comic strips throughout Australasia, where comparatively small populations have inhibited the development of indigenous comics industries.

Nevertheless, Australian and New Zealand cartoonists have jointly forged a unique regional comics idiom, which duly acknowledges their international influences, while reflecting their respective national cultures. To outside observers, neither Australian nor New Zealand comics seem to convey a distinctive national “style” in the same way that Franco-Belgian bande dessinée or Japanese mangaclearly do – a situation which has been exacerbated by their relatively limited international exposure. But to dismiss comics from Australia and New Zealand as pale imitations of their Anglo-American counterparts is to overlook their distinctive, yet subtle, graphic inflection, and the unique historical circumstances which informed their creation.

Cartoon Art in the Colonial EraThroughout the nineteenth century, Australia and New Zealand remained wedded to “British” notions of art, literature, music, and theatre, which helped bind these nations together under the aegis of empire. British magazines, with their mixture of news, stories, illustrations, and advertisements, played a key role in this process of cultural transmission. They also provided models for the earliest Australasian magazines that made extensive use of cartoons and antecedents of the modern comic strip.

Figure.2Melbourne Punch, launched in 1855, was, as its name suggests, strongly indebted to the London Punch, which pioneered the satirical illustrated magazine format a decade earlier. The colonial version’s graphic tone was set by the Russian-born artist, Nicholas Chevalier (1828-1902), hailed as the first ‘comic artist’ to work in Australia (Fig.2) (Note #2). However, Chevalier’s work was more illustrative than comical, and rarely engaged in the kind of gross exaggeration and caricature commonly associated with modern-day cartoonists.

Figure.2Melbourne Punch, launched in 1855, was, as its name suggests, strongly indebted to the London Punch, which pioneered the satirical illustrated magazine format a decade earlier. The colonial version’s graphic tone was set by the Russian-born artist, Nicholas Chevalier (1828-1902), hailed as the first ‘comic artist’ to work in Australia (Fig.2) (Note #2). However, Chevalier’s work was more illustrative than comical, and rarely engaged in the kind of gross exaggeration and caricature commonly associated with modern-day cartoonists. His successor, the London-born Thomas Carrington (1843-1918), had a far greater facility for humorous illustration and excelled at political caricature. He began drawing chiaroscuro-styled comic strips for Melbourne Punch in the 1870s, which juxtaposed dialogue and illustrations within each panel. While this approach brought them closer to present-day comic strip narrative techniques, Carrington’s illustrations still relied on typeset captions and dialogue beneath each panel to fully convey the story (Note #3).

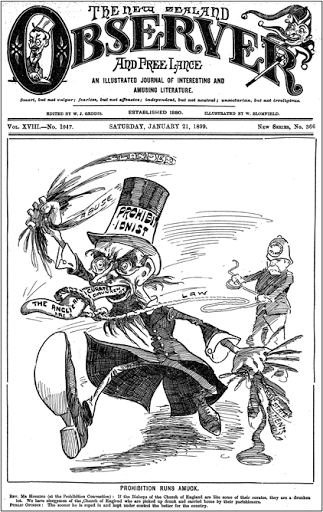

Figure 3By the 1890s, the costly and laborious wood-block engraving process used to prepare artwork for publication gradually gave way to photo-engraving techniques, thus allowing newspapers to give greater prominence to cartoons and comic strips, which could be reproduced with greater clarity in a variety of sizes. The New Zealand Graphic and Ladies’ Journal began running front-page cartoons in 1892, many of them penned by Ashley Hunter (1854-1932). The New Zealand Observer and Free Lance followed suit in 1893, capitalising on the bustling, energetic style of its resident cartoonist, William (“Blo”) Blomfield (1866-1938), considered by some to be the harbinger of modern political cartooning in New Zealand (Fig.3) (Note #4).

Figure 3By the 1890s, the costly and laborious wood-block engraving process used to prepare artwork for publication gradually gave way to photo-engraving techniques, thus allowing newspapers to give greater prominence to cartoons and comic strips, which could be reproduced with greater clarity in a variety of sizes. The New Zealand Graphic and Ladies’ Journal began running front-page cartoons in 1892, many of them penned by Ashley Hunter (1854-1932). The New Zealand Observer and Free Lance followed suit in 1893, capitalising on the bustling, energetic style of its resident cartoonist, William (“Blo”) Blomfield (1866-1938), considered by some to be the harbinger of modern political cartooning in New Zealand (Fig.3) (Note #4).

Figure 4The Bulletin became Australia’s first national magazine to use photo-engraving to enliven its visual presentation, especially in its use of cartoons and illustrations. Although The Bulletin prided itself on publishing distinctively “rustic” Australian authors, such as Henry Lawson and A.B “Banjo” Paterson, its editor William Traill (1843-1902) turned instead to American journals like Puck and Judge for the latest trends in graphic design and illustration. In 1882, Traill recruited Livingston (“Hop”) Hopkins (1846-1927), then working for The New York Daily Graphic, to join The Bulletin (Fig.4). Traill subsequently induced Philip May (1864-1903), a freelance London cartoonist, to make the trip to Sydney, where he worked for The Bulletin from 1886-89 (Note #5).

Figure 4The Bulletin became Australia’s first national magazine to use photo-engraving to enliven its visual presentation, especially in its use of cartoons and illustrations. Although The Bulletin prided itself on publishing distinctively “rustic” Australian authors, such as Henry Lawson and A.B “Banjo” Paterson, its editor William Traill (1843-1902) turned instead to American journals like Puck and Judge for the latest trends in graphic design and illustration. In 1882, Traill recruited Livingston (“Hop”) Hopkins (1846-1927), then working for The New York Daily Graphic, to join The Bulletin (Fig.4). Traill subsequently induced Philip May (1864-1903), a freelance London cartoonist, to make the trip to Sydney, where he worked for The Bulletin from 1886-89 (Note #5). Ironically, these two émigré cartoonists created many of the visual tropes that would define Australian “bush humour” cartoons and comic strips for decades to come – the slow-witted farmhands, the itinerant workers (“swaggies”) and the horse-and-buggy parsons who inhabited the stark, treeless Australian outback of the popular imagination. May developed an innovative series of ‘pantomime’ cartoons, which relayed a humorous story (without using dialogue) through a sequential series of images, enclosed in a single panel (Note #6). Between them, Hopkins and May set new standards for cartooning in Australia and cemented the magazine's reputation for producing some of the world’s best “black & white” illustrators.

As the 1890s drew to a close, Australasian cartoonists were confidently developing a distinctive, regional approach to graphic humour. While their editorial focus on domestic politics and social issues was undeniably “local”, their storytelling techniques brought them into alignment with international trends in comic-strip illustration. The creative, cultural, and economic nexus between Australasian comics, and their British and American counterparts was by now firmly established, and would only grow stronger in the opening decades of the twentieth century.

To be continued in 'Antipodean Currents', Part 2

Image Sources: Fig.1 (AusReprints); Fig.2 (Sebra Prints); Fig.3 (Papers Past/National Library of New Zealand); Fig.4 (The Bulletin Covers)

Note #1: Fatty Finn Publications (advt.), ‘Mr. Newsagent – Why not give preference to all Australian comics’, Ideas – For Stationers, Booksellers, Newsagents, Libraries, Fancy Goods, 29 (15 September 1949), 802.

Note #2: Vane Lindesay, The Inked-in Image: A Social and Historical Survey of Australian Comic Art (Richmond, VIC: Hutchinson Group Australia, 1979), p.3.

Note #3: John Ryan, Panel by Panel: A History of Australian Comics (Stanmore, NSW: Cassell Australia, 1979), p.11.

Note #4: Ian F. Grant, ‘Drawing the Line: A Short History of Editorial Cartooning in New Zealand’, Turnbull Library Record, 29 (2006), 8.

Note #5: Patricia Rolfe, The Journalistic Javelin: An Illustrated History of The Bulletin (Sydney: Wildcat Press, 1979), pp.44-48.

Note #6: Ryan, ibid, p.11.

May 30, 2021

Recent Writings About Australian Comics (2017-2021)

One of the reasons why I have only made infrequent blog posts during the last 12-18 months is that I have been preoccupied with various academic/scholarly writing projects. "Publish or perish" is the commonly heard mantra repeated to "early career researchers" like myself, as your chances of securing postdoctoral research grants and/or semi-secure full-time employment is based in part on your academic writing output. Well, that's the theory, anyway - the reality, for me at least, has been far from encouraging. Despite being told on numerous occasions that I have produced an impressive body of work (relative to opportunity) - spanning academic monographs, scholarly book chapters and peer-reviewed journal articles - I am no closer to achieving these career goals since I completed my doctoral thesis at Monash University nearly seven years ago. But this is the professional reality confronting even the best and brightest scholars in the arts & humanities disciplines, both here in the United States (where I currently live and presently teach at Fordham University), and in Australia, where I worked as a sessional university tutor for several years before moving abroad.

Nevertheless, I am proud of the work I've done in the emerging field of "comics studies" in the last five years, so I'd like to take this opportunity to share news and information about my recent writings on Australian comics, which I will hope interest readers of this blog.

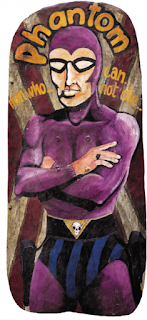

Man Who Cannot Die: Phantom Shields of the New Guinea Highlands (Jonathan Fogel, Ed., Boylan & Philips, 2021) is a beautifully presented art book, which documents the representation of the Phantom on ceremonial and tribal war shields in the Western Highlands of Papua New Guinea. This American comic strip character, created by author Lee Falk and illustrator Ray Moore in 1936, has always had a devoted following throughout Australia and the Oceanic region, but this remarkable phenomenon of Phantom as a tribal art icon may come as a surprise to even the most ardent Phantom "phan". I contributed a chapter to this book, titled "The Phantom's Oceanic Odyssey", which explains how Papuan audiences were first exposed to The Phantom comic strip in the 1970s through the pages of Wantok, a fortnightly Catholic newspaper printed in Tok Pisin, a widely-spoken dialect that is one of Papua New Guinea's three official languages, alongside English and Hiri Motu. Copies can be ordered directly from the publisher via the website link listed above, but Australian readers can also order copies via Frew Publications, which publishes the Australian edition of The Phantom comic book.

Graphic Indigeneity: Comics in the Americas and Australasia

(Frederick Luis

Graphic Indigeneity: Comics in the Americas and Australasia

(Frederick LuisAldama, Ed., University Press of Mississippi, 2020) is a collection of scholarly essays which examines how mainstream (American) comics have portrayed indigenous peoples in the Americas, and how present-day indigenous storytellers are using comics to reclaim their narrative, through documenting the complexities of their shared histories, and conveying the realities of their present-day existence. My contribution to this collection, titled "The Wisdom of the Phantom: The Secret Life of Australia's Indigenous Superhero", looks at how Australian government agencies (such as the Australian Electoral Commission and Family Court of Australia) have capitalised on the Phantom's popularity among indigenous Australian audiences by using the character in a range of educational comics and other materials devoted to such topics as voting registration, divorce and family custody disputes, and sexually transmitted diseases.

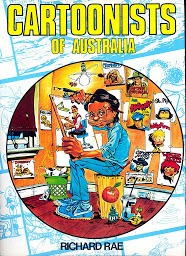

The Oxford Handbook of Comic Book Studies

(Frederick Luis Aldama, Ed., Oxford University Press, 2020) is surely proof positive that comic books have now acquired academic legitimacy, even if there is residual & institutional uncertainty about whether comics should be studied as either a form of literature, or as a visual artform - or both, for that matter. This wide-ranging collection of essays considers the formal/aesthetic parameters of the comic book medium, the formation and evolution of the comics studies discipline, media and merchandise adaptations of comic book characters, and broader political/social issues addressed in comic books and graphic novels, past and present. My contribution to this volume, titled "Radical Graphics: Australia's Second-Phase Comics", briefly recounts the history of academic studies of comic books in Australia (beginning at the height of the "anti-comic book" outcry of the late 1940s/early 1950s), before charting the evolution of the so-called "underground comix" and "small press/alternative comics" movements of the 1970s and 1980s. It also discusses the formation of organised Australian comics fandom throughout this period, and how the emerging network of comic fanzines, specialty comics retailers and comic-book conventions facilitated the growth of "New Wave" Australian comics.

The Oxford Handbook of Comic Book Studies

(Frederick Luis Aldama, Ed., Oxford University Press, 2020) is surely proof positive that comic books have now acquired academic legitimacy, even if there is residual & institutional uncertainty about whether comics should be studied as either a form of literature, or as a visual artform - or both, for that matter. This wide-ranging collection of essays considers the formal/aesthetic parameters of the comic book medium, the formation and evolution of the comics studies discipline, media and merchandise adaptations of comic book characters, and broader political/social issues addressed in comic books and graphic novels, past and present. My contribution to this volume, titled "Radical Graphics: Australia's Second-Phase Comics", briefly recounts the history of academic studies of comic books in Australia (beginning at the height of the "anti-comic book" outcry of the late 1940s/early 1950s), before charting the evolution of the so-called "underground comix" and "small press/alternative comics" movements of the 1970s and 1980s. It also discusses the formation of organised Australian comics fandom throughout this period, and how the emerging network of comic fanzines, specialty comics retailers and comic-book conventions facilitated the growth of "New Wave" Australian comics.

The Superhero Symbol: Media, Culture & Politics

(Liam Burke, Ian Gordon & Angela Ndalianis, Eds., Rutgers University Press, 2019) is a multidisciplinary collection of essays which examines different facets of the superhero genre that has come to dominate both the American comics industry and television/film sectors in recent decades. The comic book medium, at least within the Anglo-American, English-speaking world, is inextricably linked to the superhero genre. This volume features scholarly essays, as well as interviews with leading comics practitioners, that examine the commercial exploitation of superheroes in other media, the symbolic and ideological dimensions of the superhero genre, and how superheroes have articulated aspects of national identity throughout the world. My essay, titled "Age of the Atoman: Australian Superhero Comics and Cold War Modernity", looks at how Australian cartoonists promoted their superheroes as American, rather than Australian characters. This tactic that acknowledged the commercial realities of Australia's post-war comics industry, and reflected the enduring legacy of Australia's "cultural cringe" - the ingrained belief that Australia's cultural achievements were inherently inferior to their British or American equivalents.

The Superhero Symbol: Media, Culture & Politics

(Liam Burke, Ian Gordon & Angela Ndalianis, Eds., Rutgers University Press, 2019) is a multidisciplinary collection of essays which examines different facets of the superhero genre that has come to dominate both the American comics industry and television/film sectors in recent decades. The comic book medium, at least within the Anglo-American, English-speaking world, is inextricably linked to the superhero genre. This volume features scholarly essays, as well as interviews with leading comics practitioners, that examine the commercial exploitation of superheroes in other media, the symbolic and ideological dimensions of the superhero genre, and how superheroes have articulated aspects of national identity throughout the world. My essay, titled "Age of the Atoman: Australian Superhero Comics and Cold War Modernity", looks at how Australian cartoonists promoted their superheroes as American, rather than Australian characters. This tactic that acknowledged the commercial realities of Australia's post-war comics industry, and reflected the enduring legacy of Australia's "cultural cringe" - the ingrained belief that Australia's cultural achievements were inherently inferior to their British or American equivalents.

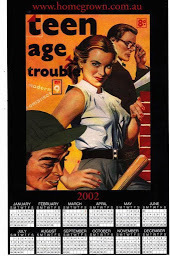

The Popular Culture of Romantic Love in Australia (Hsu-Ming Teo, Ed., Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2017). This volume examines the rituals and representations of romantic love in Australian society, from the mid-19th century to the present day. There is extensive discussion about the portrayal of romantic love in Australian cinema, television, paperback novels, and popular music. My essay, titled "Intimate Confessions: The Rise and Fall of Romance Comic Books in Australia", charts the controversial history of romance comic books in Australia, a field dominated by licensed reprints of American titles, but which also provided openings for local creators, including Moira Bertram, one of the few women to enjoy a lengthy and successful career in Australian comics. I am especially proud of this chapter, because it really does break new ground in documenting the history of Australian comics, by focusing on the neglected romance comics genre, which was responsible for broadening the historically juvenile audience for comics, by addressing such topics as romantic love, courtship, sexual intimacy and marriage that appealed to teenage girls and young women alike, who made these comics bestsellers.

The Popular Culture of Romantic Love in Australia (Hsu-Ming Teo, Ed., Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2017). This volume examines the rituals and representations of romantic love in Australian society, from the mid-19th century to the present day. There is extensive discussion about the portrayal of romantic love in Australian cinema, television, paperback novels, and popular music. My essay, titled "Intimate Confessions: The Rise and Fall of Romance Comic Books in Australia", charts the controversial history of romance comic books in Australia, a field dominated by licensed reprints of American titles, but which also provided openings for local creators, including Moira Bertram, one of the few women to enjoy a lengthy and successful career in Australian comics. I am especially proud of this chapter, because it really does break new ground in documenting the history of Australian comics, by focusing on the neglected romance comics genre, which was responsible for broadening the historically juvenile audience for comics, by addressing such topics as romantic love, courtship, sexual intimacy and marriage that appealed to teenage girls and young women alike, who made these comics bestsellers.

The Phantom Unmasked: America's First Superhero

(University of Iowa Press, 2017) was my first academic monograph, and the first book-length academic study of the Phantom, the American comic-strip character which provided the visual template for comic-book superheroes, and who predates the 1938 debut of Superman by two years. The Phantom Unmasked is based on my doctoral thesis (Monash University, 2014), which charted the production and dissemination of The Phantom comic strip (and subsequent comic magazines) in three international markets - Australia, Sweden and India - where the character has remained incredibly popular with generations of readers in each of these countries since the 1930s. This book features insights from key creative personnel associated with The Phantom comics franchise, and uses findings from an international survey of nearly 600 Phantom "phans" to explain why America's first superhero, largely forgotten or ignored by American audiences, has enjoyed unrivalled levels of international popularity. Don't believe me? Then check out the video interview I recorded for Fordham News back in 2018, and I'll 'give you the drum' about The Ghost Who Walks myself!

The Phantom Unmasked: America's First Superhero

(University of Iowa Press, 2017) was my first academic monograph, and the first book-length academic study of the Phantom, the American comic-strip character which provided the visual template for comic-book superheroes, and who predates the 1938 debut of Superman by two years. The Phantom Unmasked is based on my doctoral thesis (Monash University, 2014), which charted the production and dissemination of The Phantom comic strip (and subsequent comic magazines) in three international markets - Australia, Sweden and India - where the character has remained incredibly popular with generations of readers in each of these countries since the 1930s. This book features insights from key creative personnel associated with The Phantom comics franchise, and uses findings from an international survey of nearly 600 Phantom "phans" to explain why America's first superhero, largely forgotten or ignored by American audiences, has enjoyed unrivalled levels of international popularity. Don't believe me? Then check out the video interview I recorded for Fordham News back in 2018, and I'll 'give you the drum' about The Ghost Who Walks myself!Even though I remain (justifiably) pessimistic about my long-term academic employment prospects, I still enjoy teaching, especially now that I've had the chance to design and deliver my own course, Comic Books and American Culture, at Fordham University for the last two years. And there are still other topics about Australian comics history that I hope to explore in different academia outlets in years to come, which I will share here as well.

November 30, 2020

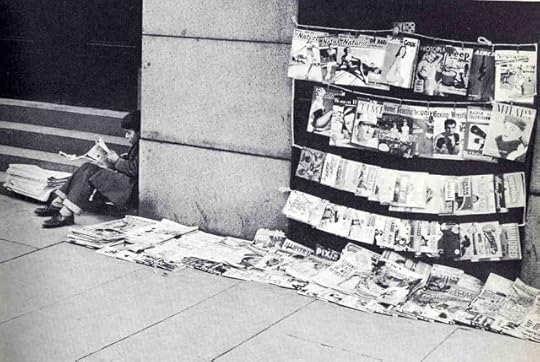

Paperboy, Collins Street, Melbourne 1957

This is a portrait of a paperboy in Collins Street, Melbourne, taken by photographer Mark Strizic. It was reproduced in a book of Strizic's photographs, "Melbourne: A Portrait", published by Georgian House in 1960. Mark Strizic (pictured below in 1958) was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1928, but following Hitler's rise to power in 1933, his family fled to Zagreb, Yugoslavia (now Croatia) the following year. He subsequently made his way to Austria at the end of the war to escape the Communist regime in Yugoslavia, and emigrated to Australia in 1950.

After working as a clerk for Victorian Railways, and studying physics part-time at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, he embarked on a full-time career as a photographer in 1957, working for institutions like the National Gallery of Victoria, as well as corporate clients, including BHP and the McPherson's confectionery firm.

After working as a clerk for Victorian Railways, and studying physics part-time at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, he embarked on a full-time career as a photographer in 1957, working for institutions like the National Gallery of Victoria, as well as corporate clients, including BHP and the McPherson's confectionery firm. This photo is of special interest to Australian comic book fans, collectors and historians, and to anyone interested in Australian media history, as it provides a fascinating snapshot of the range of magazines and books that Australians were reading and buying in the late 1950s.

You'll need to download this image to examine it properly, but in the bottom right-hand corner of the boy's makeshift newsstand, you can see copies of several Australian-drawn comics. Close examination of the photo reveals there are copies of the third issue of "The Panther" (drawn by Paul Wheelahan), which indicates this photo was taken around July 1957. Also visible in this photo are copies of "Sir Falcon" (drawn by Peter Chapman) and "Smoky Dawson" (drawn Andrea Bresciani), displayed on the footpath, which are held in place on the ground by paperback books.I uploaded this image to the Old Australian Pre-Decimal Comics up to 1966 Facebook group on 25 October, and invited members to see if they could identify any of the other comics visible in this photograph. My fellow comic-book sleuths tapped their collective memory banks and trawled the furthest reaches of the internet, and managed to successfully identify most of the comics displayed on this young boy's makeshift newsstand. The fact that they could do so, based on nothing more than a partial glimpse of a cover, is testimony to their dedication, knowledge and expertise.

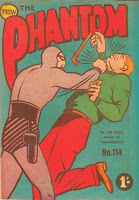

You'll need to download this image to examine it properly, but in the bottom right-hand corner of the boy's makeshift newsstand, you can see copies of several Australian-drawn comics. Close examination of the photo reveals there are copies of the third issue of "The Panther" (drawn by Paul Wheelahan), which indicates this photo was taken around July 1957. Also visible in this photo are copies of "Sir Falcon" (drawn by Peter Chapman) and "Smoky Dawson" (drawn Andrea Bresciani), displayed on the footpath, which are held in place on the ground by paperback books.I uploaded this image to the Old Australian Pre-Decimal Comics up to 1966 Facebook group on 25 October, and invited members to see if they could identify any of the other comics visible in this photograph. My fellow comic-book sleuths tapped their collective memory banks and trawled the furthest reaches of the internet, and managed to successfully identify most of the comics displayed on this young boy's makeshift newsstand. The fact that they could do so, based on nothing more than a partial glimpse of a cover, is testimony to their dedication, knowledge and expertise. A copy of "The Phantom" no.114 is displayed to the right of "The Panther", while a copy of "Felix the Cat" no.13 is partly visible above the (as yet unidentified) edition of "Sir Falcon". Visible directly above "The Panther" is a copy of Horwitz Publications' US-reprint crime title, "Tales of Justice" no.4. It's also been suggested that the comic seen directly above "Sir Falcon" and "Felix the Cat" is "Popular Pictorial" no.11, featuring 'Ben Bowie and his Mountain Men'.

A copy of "The Phantom" no.114 is displayed to the right of "The Panther", while a copy of "Felix the Cat" no.13 is partly visible above the (as yet unidentified) edition of "Sir Falcon". Visible directly above "The Panther" is a copy of Horwitz Publications' US-reprint crime title, "Tales of Justice" no.4. It's also been suggested that the comic seen directly above "Sir Falcon" and "Felix the Cat" is "Popular Pictorial" no.11, featuring 'Ben Bowie and his Mountain Men'.Just above the footpath display, there is a group of comic books draped over a rope strung across a display board. To date, the Pre-Decimal Comics group members have identified copies of K.G. Murray's "Hundred Comic Monthly" no.9, "Century Comic Monthly" no.13, and the debut issue of "Magic Moment Romances" series.

There are several editions of the "Classics Illustrated" series, issued by Strato Publications (UK), on the bottom row of the upright board display. These include issues #5 ("Moby Dick"), #8 ("The Odyssey"), and #46 ("Kidnapped"). There is also a copy of the Young's Merchandising title, "The Fighting Army and Navy Comic", visible on the far left of the row of magazines directly above the "Classics Illustrated" titles. There may be other comics on this same row of magazines, but I can't make out any further titles.

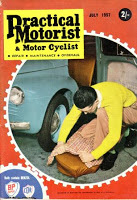

The photo also shows a fascinating variety of imported and locally-published magazines, including several issues of the nudist/sunbather magazine, "The Naturist", "Practical Motorist and Motor Cyclist", "Radio Television and Hobbies", "Motor Racing and Motor Rally", and three local pin-up magazines, "Peep - For Men Only", "Gals and Gags", and "Man Junior". Imported copies of "Time" and "Newsweek' magazine are also clearly visible in this photograph. Many of the Australian magazines identified by the group's members bore a July 1957 cover date, which suggests this photo may have been taken sometime in mid/late June 1957.

James Zanotto, curator of the AusReprints website, has created a dedicated page listing all the identified comics and magazines featured in this photograph, which can be viewed here. This list will be updated as more titles are identified - and readers of this blog are definitely encouraged to try their hand at spotting some of the titles missing from the AusReprints list.

Makeshift newsstands like one this dotted the busy intersections and side-streets of Melbourne during the 1950s, offering commuters a rich variety of reading material to choose from to help alleviate the tedium of long train, tram or bus trips home during the weekday rush-hour. Even small street corner newsstands like the one captured in this photograph offered newspapers, magazines and paperback novels that catered for a wide variety of tastes and interests, from aviation and home decoration, to movie stars and professional sports.

Strizic's photographs of Melbourne's skyline, streetscapes, everyday people and prominent public figures capture the city during a period of controversial renovation and renewal, with many older, Victorian & Edwardian-era buildings being demolished to make way for more modern, contemporary structures and public places. In 2007, the State Library of Victoria acquired Strizic's entire archive of 5,000 photographic negatives, slides and transparencies (You can search for many of these images on the State Library of Victoria's online catalogue) He died in Wallan, Victoria, in 2012.You can view a selection of Strizic's photographs of Melbourne's streetscapes, and portraits of notable artists, at the National Gallery of Victoria's online collection

Strizic's photographs of Melbourne's skyline, streetscapes, everyday people and prominent public figures capture the city during a period of controversial renovation and renewal, with many older, Victorian & Edwardian-era buildings being demolished to make way for more modern, contemporary structures and public places. In 2007, the State Library of Victoria acquired Strizic's entire archive of 5,000 photographic negatives, slides and transparencies (You can search for many of these images on the State Library of Victoria's online catalogue) He died in Wallan, Victoria, in 2012.You can view a selection of Strizic's photographs of Melbourne's streetscapes, and portraits of notable artists, at the National Gallery of Victoria's online collection

November 25, 2020

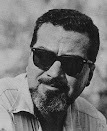

Vale - Yaroslav Horak (1927-2020)

The Australian Cartoonists' Association announced on 25 November 2020 that acclaimed Australian comic-strip artist, Yaroslav Horak, had passed away after a decade-long struggle with Alzheimer's Disease. The following blog post is a revised and expanded of my article on Horak's life and work, which was published as 'Yaroslav Horak: The Man Behind the Masks', in Giant Size Phantom, no.9 (May 2019).

The Australian Cartoonists' Association announced on 25 November 2020 that acclaimed Australian comic-strip artist, Yaroslav Horak, had passed away after a decade-long struggle with Alzheimer's Disease. The following blog post is a revised and expanded of my article on Horak's life and work, which was published as 'Yaroslav Horak: The Man Behind the Masks', in Giant Size Phantom, no.9 (May 2019).Yaroslav Horak’s childhood reads like the dramatic scenario for one of the countless comic-book adventures he went on to draw for most of his adult life. He was born on 12 June 1927, in Harbin, Manchuria, where his father, Joseph, a Czech-born engineer, owned a successful manufacturing business. Joseph and his Russian wife, Zinaida, eventually joined the growing throng of European refugees who fled Harbin following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931. Disturbed by the brutality of the occupying Japanese army, the Horak family left Manchuria on a steamship bound for Australia in July 1939.

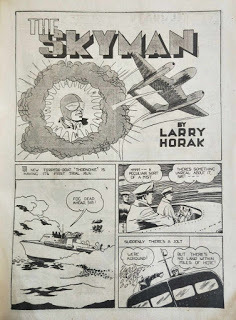

They settled in Sydney, where Yaroslav attended high school and subsequently took evening art classes at Sydney Technical College (You can read the Sydney News' 1944 profile about the youthful Yaroslav Horak - pictured at left - here). He soon turned his artistic flair to drawing comic-book features for Sydney’s thriving comic-magazine market. His first published work, “Grey Thorne, Counter Espionage Agent”, appeared in Frank Johnson Publications’ Gem Comics in 1947. Horak created his first recurring character, “Rick Davis, Special Correspondent”, as a supporting feature in H.J. Edwards’ top-selling Action Comic title. This was followed by “The Skyman”, which ran in both Action Comic and John Dixon’s Tim Valour Comic. This aviation-themed series was the first comic to carry the artist’s Anglicized by-line, “Larry Horak”.

They settled in Sydney, where Yaroslav attended high school and subsequently took evening art classes at Sydney Technical College (You can read the Sydney News' 1944 profile about the youthful Yaroslav Horak - pictured at left - here). He soon turned his artistic flair to drawing comic-book features for Sydney’s thriving comic-magazine market. His first published work, “Grey Thorne, Counter Espionage Agent”, appeared in Frank Johnson Publications’ Gem Comics in 1947. Horak created his first recurring character, “Rick Davis, Special Correspondent”, as a supporting feature in H.J. Edwards’ top-selling Action Comic title. This was followed by “The Skyman”, which ran in both Action Comic and John Dixon’s Tim Valour Comic. This aviation-themed series was the first comic to carry the artist’s Anglicized by-line, “Larry Horak”.

Syd Nicholls (1896-1977), creator of the much-loved Fatty Finnnewspaper comic strip, recruited Australia’s best young cartoonists to work on his small, but expansive range of “All-Australian” comic magazines. Horak joined their ranks in 1948, producing “Bob Arlen”, a motor-racing feature, together with the science-fiction serial, “Ripon – The Man Out of Space”, for Nicholls’ flagship title, Middy Malone Magazine. The latter series showcased some of Horak’s best work to date, but it was brought to a premature end following Nicholls’ decision to quit the comic-book field by the end of 1949.

Nevertheless, Sydney’s bustling comics industry continued to new offer outlets for talented, ambitious cartoonists keen to ply their skills in this lucrative market. Horak produced his first solo comic book, Mr Combat, for Elmsdale Publications in 1950, but his “globetrotting crime-buster” was cancelled after just three issues. He subsequently created “Chandor, Jungle Doctor” as a supporting feature for the Yarmak – Jungle King comic published by Young’s Merchandising.

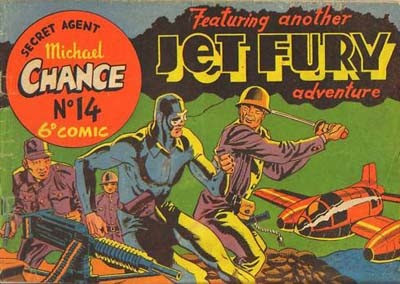

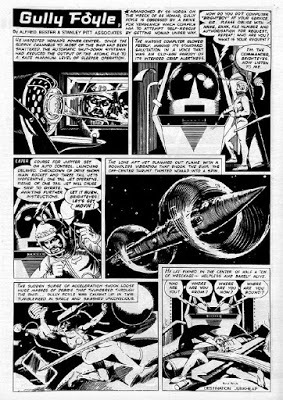

Horak’s next venture established beyond doubt his reputation as an accomplished visual storyteller. Jet Fury was a masked aviator, who flew to global trouble-spots aboard the Comet, an “anti-gravity” jet that surpassed any other aircraft in the sky. The series, which began as a supporting feature in Michael Chance Comic, was in many respects a streamlined, updated version of Horak’s earlier “Skyman” strip. But the series’ emphasis on hi-tech action, beautifully realized by Horak’s dynamic artwork, proved so popular that Pyramid Publications rechristened the magazine Jet Fury Comic with its 16th issue in 1951.

Horak relocated to Melbourne in 1953, and began working for Atlas Publications, which had acquired the comic-book rights to the American newspaper strip, Brenda Starr, Reporter, created by Dale Messick (1906-2005). However, the company handed the artistic reins to Horak with the 14th issue, who drew most of the lead stories until the series ceased publication in 1954. Horak’s art on Brenda Starr was already showing signs of the brisk, energetic style that would become his trademark “look” in decades to come, brilliantly complemented by his cinematic panel compositions.

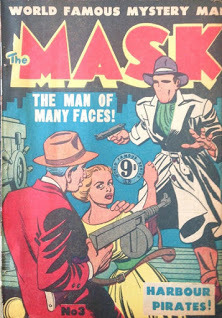

Horak’s final series for Atlas Publications proved to be his most controversial. The Mask – The Man of Many Faces starred a mysterious, elusive crimefighter, who could alter his blank, skull-like face to resemble any man, living or dead, which allowed him to penetrate the secretive worlds of organized crime and international espionage in his pursuit of justice. The comic was an immediate success, but it ran afoul of Queensland’s Literature Board of Review, which objected to the character’s full-face mask, and imposed a state-wide sales ban on the comic, thus forcing Atlas Publications to reluctantly cancel the title with its third issue in 1954.

Disillusioned by the experience, Horak gradually withdrew from the comic-book industry and began focusing his energies on the more lucrative newspaper comic-strip field. Horak created history with his debut newspaper feature, "Captain Fortune", which became the first Australian comic strip to be adapted from a local television program. Captain Fortune was a children’s variety program, hosted by a fictitious mariner played by veteran stage and radio actor, Alan Herbert (1913-1966), which aired on ATN-7 between 1956-1961. Horak turned "Captain Fortune" into a suspenseful adventure comic aimed at adult readers, which appeared in Sydney’s Sun-Heraldnewspaper from December 1957 until July 1962.

Emboldened by this success, Horak created a new adventure comic strip, "Mike Steel, Desert Rider", for Woman’s Day magazine. The protagonist, Mike Steel, was a mounted trooper who brought law and order to the desert wilderness of Central Australia. The series, written by Woman’s Day editor Keith Findlay (under the pseudonym “Roger Rowe”), made its debut as a full-colour strip in August 1962, but was shortly converted into the black-and-white format that was retained until the series’ conclusion in January 1969.

Horak moved to England in 1963, and began drawing strips for D.C. Thompson’s weekly adventure comic, The Victor. One of Horak's earliest known serials was 'Johny Hop', which chronicled the adventures of Constable Bill Lennox and his Aboriginal tracker companion, Wally Omes, in Outback Australia, and appeared in The Victor throughout July-September 1964. His subsequent serial, "The Bent Copper", was about ex-Scotland Yard detective John Bright, who sought revenge against the criminal who framed him for a crime he did not commit. "The Bent Copper" appeared in The Victor throughout July-August 1965.

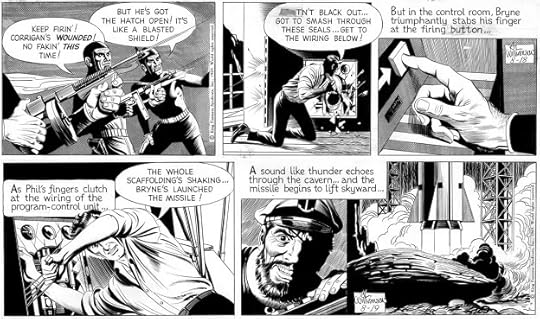

Horak moved to England in 1963, and began drawing strips for D.C. Thompson’s weekly adventure comic, The Victor. One of Horak's earliest known serials was 'Johny Hop', which chronicled the adventures of Constable Bill Lennox and his Aboriginal tracker companion, Wally Omes, in Outback Australia, and appeared in The Victor throughout July-September 1964. His subsequent serial, "The Bent Copper", was about ex-Scotland Yard detective John Bright, who sought revenge against the criminal who framed him for a crime he did not commit. "The Bent Copper" appeared in The Victor throughout July-August 1965.Horak’s bold, dramatic style lent itself beautifully to the pocket-sized war comics that were captivating a new generation of British readers, who’d grown up in the shadow of World War Two. Between 1963-66, Horak drew nearly a dozen stories for the War Picture Library and Battle Picture Library series published by Fleetway Publications. These gritty, action-packed war stories – which were exported to Australia and New Zealand and published in translation throughout Western Europe – were in many ways the perfect subject for Horak, who displayed his command of black and white illustrative technique to brilliant effect. His final, belated contribution to the War Picture Library series – published as “The Curse” – appeared in 1971.

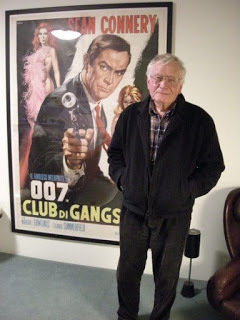

By this time, Horak had rented a studio above the El Vino wine bar in London’s Fleet Street, home to many of England’s leading newspapers, which became a magnet for countless journalists, writers and artists. Horak worked in the same building as the British author Peter O’Donnell (1920-2010), who wrote the comic-strip adaptation of Ian Fleming’s spy novel, Dr. No, for the Daily Express newspaper in 1958. O’Donnell, who later achieved worldwide fame as the creator of comic-strip heroine Modesty Blaise, nominated Horak to replace John McClusky (1925-2006) as the permanent artist on the James Bond comic strip, which had resumed publication in the Daily Expressin 1964 (The series recommenced after a two-year hiatus following the resolution of a contractual dispute between Ian Fleming and the British newspaper magnate, Lord Beaverbrook).

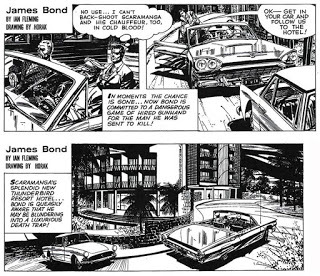

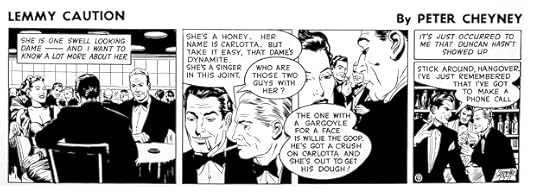

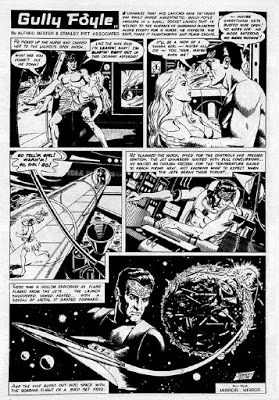

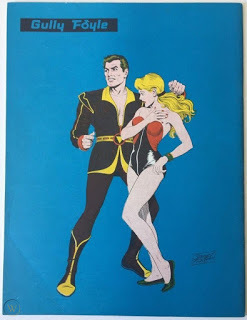

The American novelist and journalist Jim Lawrence (1918-1994) and Horak (pictured right, circa 1960s) made their joint debut on James Bond with their adaptation of “The Man with the Golden Gun”, which appeared in the Daily Expressthroughout 1966 (Two episodes are reproduced below). This marked the start of their decade-long collaboration, which saw them recast James Bond as a tough antihero, completely at odds with Roger Moore’s droll screen portrayal of the character, but who was in many ways closer to the spirit of Ian Fleming’s earliest “Bond” novels (There is an interesting discussion/analysis of Horak's work on the "James Bond" comic strip to be found on the Dave Karlen Original Art Blog, dating from August 2008).

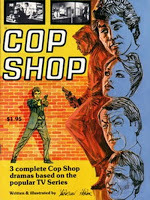

Horak worked and travelled throughout Europe for several years, before eventually returning to Sydney in 1975. Even after the Daily Express dropped the James Bondcomic strip in 1977, Horak and Lawrence continued to produce new James Bond stories for the Scandinavian market, where it continued to appear in newspapers and comic magazines until the mid-1980s. Ironically, a new Australian television show brought Horak back to the pages of Sydney’s Sun-Heraldnewspaper in 1980. Cop Shop was a popular police drama, produced by Crawford Productions, which aired on the Seven Network between 1977 and 1984. Horak was commissioned to write and illustrate a comic-strip adaptation of the series for the Sun-Herald, where it appeared as a half-page comic strip throughout 1980-83. Three complete stories from Horak’s series were reprinted in a spin-off Cop Shop comic magazine, which was released nationwide in 1983.

Horak’s last published work fulfilled his lifelong ambition to create his own comic strip. Andea was a science-fiction serial about a glamorous female extra-terrestrial who travelled to Australia from the distant planet Xavax. The Daily Mirrorlaunched Andea as a weekend comic strip in September 1980, no doubt hoping it would prove a worthy match to Roger Fletcher’s science-fiction strip, Staria, which had been a popular mainstay at the Daily Telegraph since 1977. Andeashowcased Horak’s storytelling skills to brilliant effect, with his intricate plots, fantastic characters, and exquisite artwork demonstrating his complete mastery of the medium throughout the series’ seven-year run. It was a fitting end to Yaroslav Horak’s incomparable career as one of Australia’s great comic artists.

Yaroslav Horak was subsequently awarded the Ledger of Honour in recognition of his contributions to Australian comics, as part of the Ledger Awards for 2018 (He was a joint recipient with fellow Australian comic artists, Kathleen and Moira Bertram. Readers can download the 2018 Ledger Awards Annual, which also features a profile on Horak's life and work). The Australian Cartoonists' Association published a lengthy interview with Horak in their Inkspot journal (No.59, 2009), which can be viewed online here. Horak is survived by his Jacie, and his children, Anton, Damon and Natascha.

Images reproduced here were sourced from the following websites: Ausreprints.net; Dave Karlen Original Art Blog; Pikitia Press; The Victor-Hornet Comics; Qwizzeria; Tebeosfera;