Mark Piesing's Blog

October 12, 2025

My latest for History.com: 7 Brilliant Acts of Psychological Warfare in History

Read my latest piece for The History Channel’s history.com website (only available in the USA or by using a VPN) in full below – or the original here.

Long before the term “psychological operations”—or “psyops”—entered modern military jargon, the art of manipulating perception to influence enemy behavior has shaped the course of history. From the famed Trojan Horse ruse to Gulf War leaflets and covert broadcasts, psyops have played a vital, often hidden role in warfare. These tactics aim not to wound the body but to unnerve the mind—demoralizing, confusing or coercing without firing a shot.

The most effective psyops have weaponized the universal and timeless levers of human behavior—fear, faith, illusion, disinformation, the desire to belong—to undermine, deceive or destabilize an opponent. But some psyops have proven more ingenious than others. Here are seven:

Mongol warriors, shown in an illustration to ‘Jami al-tawarikh,’ a 14th-century world history that includes the Mongol conquests. Bilbiotheque Nationale, Paris.

1.

Alexander the Great (336-323 B.C.)Alexander the Great was a master of battlefield strategy—but the Macedonian king also wielded psychological warfare to intimidate enemies long before swords were drawn. His most effective tool? Exploiting local superstitions to portray himself as a godlike, unstoppable conqueror. “Alexander the Great used myth-making and identity-sharing by absorbing the culture of the lands he conquered,” says psychological warfare historian Dr. James Crossland, author of Rogue Agent. That way, he could “present himself as the embodiment of local gods or the local beliefs.”

In Persia, he adopted the royal customs and divine titles of the Achaemenid kings, calling himself “King of Kings” and dressing in traditional Persian royal attire. In Egypt, priests portrayed him as pharaoh, an incarnate god.

He reinforced his image with kinship myths, claiming descent from Herakles and Achilles, paragons of strength and warrior prowess. Egyptian priests even declared him the son of Zeus-Ammon, the hybrid Greek-Egyptian deity, cementing his role as a spiritual bridge between empires.

The cult of personality he created made his soldiers believe the gods favored him—and terrified his enemies. Ancient accounts say some foes threw themselves from cliffs rather than face him in battle.

Alexander’s psyops proved remarkably effective. Though Macedonia lacked the wealth or cultural clout of Mediterranean city-states like Athens, he conquered the mighty Persian Empire, and forged a vast dominion stretching to modern-day Pakistan. “’I am the person you have been waiting for’ is a very effective narrative,” says Crossland, “because it plays to the human need to have a simple explanation for why this person has laid waste to everything in his path.”

Alexander the Great

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

2.

Genghis Khan (1206-1227)Genghis Khan wielded terror as a calculated weapon, turning psychological warfare into a cornerstone of his conquests. “Like Attila the Hun before him and Vlad the Impaler after him, Genghis Khan used rumor to inflate his reputation ahead of whatever military operation is to come,” says Crossland.

He instilled fear in his opponents with mass killings—slaughtering nearly everyone in a city, but deliberately sparing a few. These survivors would then spread word of Mongol brutality, helping convince the next city to surrender without a fight.

On the battlefield, he unleashed sensory overload. Synchronized drums, horns and bloodcurdling battle cries created a deafening wall of sound to disorient and terrify his enemies. He attacked from multiple directions to keep an opposing army, or city defenders, tense and off-balance, unable to anticipate his next move.

His strategies were remarkably effective. Genghis Khan conquered more territory in 25 years than Rome did in 400—largely through fear. “These are classic examples of psyops, and the fundamentals have not changed since then,” says Crossland. “Genghis Khan used the marketplace to spread his rumors. We use social media.”

Mongol warriors, shown in an illustration to ‘Jami al-tawarikh,’ a 14th-century world history that includes the Mongol conquests. Bilbiotheque Nationale, Paris.

Photo12/Universal Images Group v

3.

‘Der Chef’ (1941-43)During World War II, many Germans unknowingly tuned in to bogus British-run radio stations created by the country’s Political Warfare Executive, a clandestine body that produced war propaganda. Their mission: to manipulate public opinion, sap morale and erode faith in Hitler’s regime from within. One of its most popular voices was “Der Chef,” a fictional insider who seemed to speak with authority from within the Third Reich.

Der Chef was a fictional Nazi officer broadcast on a fake radio station called Gustav Siegfried Eins (GS1). Posing as an old-school Prussian general, he used supposed insider knowledge to rail against Nazi leaders—accusing them of corruption, buffoonery and sexual deviancy—all while claiming allegiance to the regime.

In 1945, the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor to the CIA) took the deception further with Operation Cornflake—a bold plan to infiltrate Hitler’s mail system by air-dropping fake anti-Nazi newspapers and letters addressed to ordinary Germans. The effort fizzled in the war’s final chaos, but it remains one of the most audacious psychological stunts of the conflict.

Joseph Goebbels, the Nazis’ propaganda chief, certainly thought the fake broadcasts and newspapers were effective. “People believed it was real,” says Crossland. “Der Chef’s ability to speak German, knowledge of German culture, knowledge of the Nazis, created a convincing figure that people believed in. “He’s asking questions that ordinary folks in Germany in 1942–43 are starting to ask.”

4.

Operation Mincemeat (1943)In 1943, the Spanish authorities found the body of “Major William Martin” of the Royal Marines off the coast of Spain. He carried theater ticket stubs, love letters, a photograph of his fiancée—and classified documents suggesting the Allies would invade Greece, not Sicily.

The British pleaded for the documents’ return. Convinced by the deception, the Germans redeployed troops from Sicily to Greece.

But “Major Martin” never existed. The body was that of Glyndwr Michael, a homeless man who had died from rat poison. The scheme—Operation Mincemeat—helped the Allies conquer Sicily in just a month and paved the way for the invasion of Italy.

Operation Mincemeat—devised, in part, by future James Bond creator Ian Fleming, then a British Naval Intelligence Officer—was a highly successful “act of misdirection, using one of the cleverest ploys ever devised,” says Crossland. “It worked because it made sense to the Germans at the time that the body was found by the Spanish, and with all the evidence suggesting he would have had access to these plans.”

5.

Operation Fortitude (1944)In 1944, Adolf Hitler knew the Allies would invade France—but not where. He suspected the Pas-de-Calais, the English Channel’s narrowest point. Normandy and Norway were also options. The Allies decided to convince Hitler that he was right.

As part of Operation Fortitude, they staged a massive hoax: Hundreds of inflatable tanks were set up in Kent, across the Channel from Calais, alongside the fictional First U.S. Army Group, allegedly led by General George S. Patton. Fake radio chatter completed the illusion.

Meanwhile, double agent Juan Pujol García (codename: Garbo) fed Berlin a steady stream of false intelligence from a network of entirely fictional spies.

The ruse worked. The 150,000 German forces stayed pinned at Calais even after D-Day, letting the Allies establish their beachhead in Normandy. According to Crossland, Operation Fortitude worked on several levels. “There was deception; the inflatables were a neat trick. It was also playing on Hitler’s pre-existing belief that the Allies would invade in the Pas-de-Calais, and then inflated that belief, and distorted reality around it.”

Inflatable dummy tanks like this were used during World War II’s Operation Fortitude in 1944 in two ways—to make Germans think the Allies had more tanks than they did; and to divert attention from the location of their real tanks.

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

6.

‘Vampire’ Monster (early 1950s)During the communist Huk rebellion in the Philippines, the Filipino army—assisted by America’s Central Intelligence Agency—weaponized folk superstition in one of history’s bloodiest psyops.

To exploit local fears of the asuang, a vampire-like shapeshifting monster from Filipino folklore, army “psywar” squads spread rumors that one was stalking the hills controlled by Huk rebels. They gave the tale five days to take root in nearby villages and mountain camps.

Then, under cover of night, they set an ambush. As the Huk patrol passed by, the squad silently snatched the last man. They punctured his neck with fang-like wounds, drained his blood and left his body on the path for his comrades to discover—evidence, it seemed, of a supernatural predator.

The vampire psyop appeared to work. When the Huks found the bloodless corpse, they abandoned the area—unsure whether the threat was an asuang or violent American operatives.

Though it appears to have been just a single operation, the Huk rebellion became a “laboratory” for psychological warfare. Other tactics included flying over rebel territory while broadcasting curses at farmers suspected of aiding fighters, and painting ominous symbols—like “the eye of God”—on the homes of suspected sympathizers. In the end, it was more traditional tactics, and mounting fatigue, that finally brought the conflict to a close in 1954.

A Viet Cong guerrilla surrenders to Republic of Vietnam soldiers after seeing psychological warfare leaflets dropped by U.S. Air Force commandos, Nha Trang, Vietnam, February 16, 1966.

Underwood Archives/Getty Images

7.

Operation Wandering Soul (1969–1970)During the night of February 10, 1970, eerie cries and shrieks echoed through the jungle surrounding a U.S. Army base in Hau Nghia Province, South Vietnam. Hidden loudspeakers projected ghostly voices sobbing in Vietnamese, “My friends, I have come back to let you know that I am dead… I am dead! It’s hell… I’m in hell!”

This was the Wandering Soul tape, a psychological weapon designed to exploit Vietnamese spiritual beliefs about death and burial. Many Viet Cong fighting in the Vietnam War feared dying far from home and becoming cursed “wandering souls,” forever trapped in the jungle without proper rites.

The tape’s effectiveness is hard to measure. “It certainly exploited the Vietnamese’s pre-existing beliefs about the importance of a proper burial and combined it with the reality of that war and used audio recordings to enhance it,” says Crossland. “There were some instances of Viet Cong sending out burial parties, or defecting.” Around 150 Viet Cong fighters defected one night when the psyops unit mixed the ghost tape with the sounds of tigers from Bangkok zoo.

Wandering Soul may have rattled nerves and stirred superstitions—but, as Crossland points out, “by itself, it didn’t win America the war.”

Read my first piece for The Royal Aeronautical Society’s AEROSPACE magazine…DEJA DRONE…

I am chuffed to bits to have my 4-page feature article Deja Drone published in the fantastic Royal Aeronautical Society AEROSPACE magazine this month!

Eighty years after the US first used attack drones in the Pacific, the idea is back on the agenda for the South China Sea.

Download the magazine here. Read it in full below. The text follows at the end.

This feature was inspired by my Aerospace Media Awards 2025 award-winning feature, The Secret History of Drones, which I wrote for The Smithsonian’s Air and Space Quarterly.

This was in turn inspired by my feature for BBC Future The robot aircraft with a nightmarish nuclear mission, which was an Aerospace Media Awards finalist 2024.

Off the back of these articles I was asked to write this for The History Channel’s website History.com (accessible only from within USA or via VPN connected to a US server) How Drones Have Upended Warfare.

Eighty years after the US military first used drones in the Pacific, the idea is back on the table for any future operations in the South China Sea. MARK PIESING asks what lessons can be learned from the past.

According to US intelligence, President Xi Jinping has called on China’s People’s Liberation Army to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. If so, the US military will have its work cut out to defend an island a long way from home against the country with probably the largest navy on Earth, the largest number of military aircraft in the region and what is likely to be a formidable arsenal of combat drones.

China’s impressive industrial base means Chinese manufacturers currently control around 90% of the global commercial drone market and its components have been found in UAVs built for the US military.

In 2024, the commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Samuel Paparo, declared that the US military’s plan to ensure that the Chinese invasion does not succeed depends on its ability to turn the Taiwan Strait into an “unmanned hellscape.”

Replicator

This plan seems to depend on the US’ ability to rapidly build and deploy thousands of disposable AI-enabled attack drones that can operate either independently or as loyal wingmen to buy the US some time. In turn, this seems to hang on the success of the US Department of Defense’s directive to unleash “US military drone dominance” and initiatives, such as the Replicator programme.

Replicator’s goal is ‘rapid innovation’ by using existing commercial technology to produce drones cheaply, quickly and in large numbers – all while bypassing the Pentagon’s slow and bureaucratic acquisition process.

At a recent Pentagon event to demonstrate the results of these initiatives, 18 autonomous prototypes were revealed that, it is claimed, had been developed over 18 months rather than the usual four to five years. These included aerial systems, a 36ft span long-endurance uncrewed aerial system dubbed Vanilla, as well as surface and sub-surface systems.

“The affordability of drones is something that is very attractive to the US military, [given] the need for a lot of munitions and platforms to fight China,” says Stacie L Pettyjohn, Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security, a Washington, DC think tank and co-author of the report Swarms over the Strait: Drone Warfare in a Future Fight to Defend Taiwan. “Some people argue they have been decisive in Ukraine and can offer a cheap form of standoff strike that the US just doesn’t have right now.”

However, she warns that “they just don’t have the money in the near term. So, it is more aspirational than anything and, in reality, right now, most US combat power would still come from traditional, crewed platforms, whether it is B-52s or B-2s and short-range fighter aircraft early in the fight.”

Project Option

However, this is not the first time that the US military has not had air supremacy, lacked an industrial base and turned to cheap, uncrewed platforms for a way to try to create a so-called ‘unmanned hellscape’ to defeat a formidable opponent.

In the first half of 1942, the US faced a precarious situation in the Pacific. The Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor had crippled its Pacific fleet, in the Philippines it had suffered

one of the worst military defeats in its history and Japan now seemed to be threatening Australia, the Solomon Islands and even Hawaii with invasion.

Moreover, the mobilisation of its industrial muscle and its population had only just begun, and the US lacked the pilots and aircraft needed to fight the Japanese. On 22 May 1942, less than two weeks before the Battle of Midway, Fleet Admiral Ernest King, Chief of US Navy Operations, launched Project Option, ordering the deployment of assault drones “at the earliest practical date.”

Project Option was first envisaged to be a billion-dollar programme involving the construction of 5,000 remotely piloted assault drones. Their mission would be to overwhelm the Japanese defences in the Pacific for ‘maximum impact’ before countermeasures were launched against them.

King’s order for 5,000 assault drones was reduced to 500 and, of these, only around 300 were eventually delivered. Their effectiveness is still a matter for debate 80 years later.

“Project Option was, in reality, literally that – an option on the table,” says Roger Connor, curator in the National Air and Space Museum’s aeronautics department. “It was a point of exploration. It was an experiment.”

Lessons from the past

What then are the lessons from the past for the Pacific drone war of the future?

In 1939, anti-aircraft gunners of the battleship USS Utah had their first chance to try to shoot down the US Navy’s latest piece of high-tech kit – uncrewed target drones.

These were in fact obsolete aircraft, such as Curtiss N2C Fledgling trainers, that had been “droned’ by turning them into radio-controlled aircraft flown from an aircraft nearby. The Utah had recently been reclassified as a target ship and re-equipped with anti-aircraft guns for training gunners to shoot down the new generation of faster-turning aircraft. Two years later it would be sunk by Japanese torpedo bombers during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

However, in 1939, it immediately became clear that the US Navy had a problem. “During the gunnery trials in 1939 [in Guantanamo Bay], it was clear that the gunners were struggling to hit these manoeuvring drones,” says Connor, “and the realisation dawned on those present that the ships themselves might be vulnerable to drones armed with a large explosive payload.”

“It was then, even before Pearl Harbor, that the idea of the attack drone really starts to gain traction in the higher echelons of the US Navy,” he says.

“That they might be a useful contingency for when they are in a situation where they do not have air superiority and must attack an enemy battleship without needlessly risking a valuable aircraft and crew.”

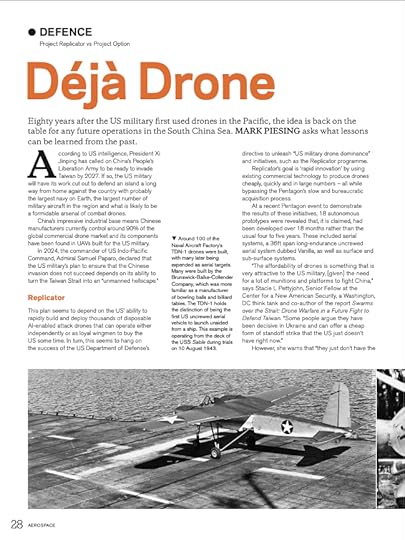

First-person view in the ‘40s

The fact that attack drones were even technologically possible was due to convergence with another new technology: television. What is today known as first-person view (FPV) technology is traced back to this innovation, which then allowed the pilot a remote ‘inside out view’, as though they were flying the drone itself – albeit on a 7in screen.

It was perhaps no wonder that King seemed at first to envisage Project Option involving thousands of attack drones, formed into 18 operational squadrons, with a workforce of 10,000 civilian and military personnel. However, the admiral’s vision hit the hard reality of a nation mobilising for war and conflicted with the need to maintain a supply of new aircraft and trained pilots, particularly after the battles of Midway and the Coral Sea.

Non-strategic materials

The US Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics persuaded King to scale back the order of drones to 500, using non-strategic materials and manufactured by suppliers with little experience of making aircraft, such as the Wurlitzer musical instrument company and the Schwinn Bicycle Company.

“The programme was a challenge,” says Connor. “It needed to use non-strategic materials, like wood, and the assumption was that if you do that, it should also be probably easy to build, which was not really the case. It took a long time to iron the bugs out. Additionally, the corporate infrastructure for this project was such that it was not really well suited to mass production of military aircraft in a wartime environment. Some of it was using manufacturers that had little aircraft experience, so that the aircraft were really slow to roll out.”

The production run was split almost equally between two main types, those built by the Naval Aircraft Factory (designated TDN-1s) and the Interstate Aircraft and Engineering Corporation (known as TDR-1s). The two assault drones looked similar, although with its streamlined dihedral low wings the TDR-1 looked more the part compared to its rival’s more conventional shoulder-mounted overhead wings.

Both were equipped with a pair of low- performance six-cylinder Lycoming engines, yet could carry a 2,000lb bomb or torpedo and were controlled from a converted Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bomber with the drone pilot and radar operator squeezed into the rear cockpit hunched over a black- and-white TV screen.

The drones came catapult-ready for carrier deployment and jettisoned their landing gear before heading for their target. There was a rudimentary cockpit for a human pilot – for testing and ferrying – which was replaced by a fairing flush with the fuselage to reduce drag when operational.

The first were delivered at the end of 1942, but delays meant that only around 300 were built (195 TDR-1s and around 100 TDN-1s) by the time the programme was abruptly cancelled in August 1944 at the apparent insistence of the Bureau of Aeronautics.

By then the US had achieved air superiority over the Japanese but opposition to the cancellation from the US Marine Corps meant that an estimated 50 TDR-1s did see action for evaluation purposes. During September and October 1944, Special Task Air Group One (STAG-1) operated TDR-1s from Banika on the Russell Islands, in combat action against enemy targets in the Solomon’s area. They were launched against Japanese anti-aircraft positions, bridges and airfields around bases with a total of 31 striking their targets. A further 19 were downed by radio interference or mechanical faults. If they reached their target, it appears that the

drones were often flown directly into the positions, bombs and all. In other cases, they dropped their bombs and – if they did not crash or were not shot down – crashed intentionally into the same, or secondary, target.

Too little, too late

“I think the story of Project Option is speaking to this moment,” says Roger Connor. “One lesson with the TDN and TDR is that they were far too late to justify their places. If it had been earlier, when US air supremacy was nowhere in sight, there might have been a lot more interest in that kind of capability.”

Scroll forward 80 years, and two US companies are working on drones that could also turn Paparo’s plan into a reality as part of the USAF’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) programme. The sleek, shark-like and appropriately named YFQ-44A Fury is under development by Anduril Industries, while another is General Atomic’s YFQ- 42A prototype which flew for the first time on 27 August, just 16 months after the contract was awarded.

Another lesson, Connor believes, is the necessity for speed in innovation and production.

“I think the ability to shorten the production tail, using 3D printing techniques and the kind of rapid prototyping ability, that the Ukrainians have shown, is vital,” he says, “as well as the ability to modify a whole existing array of technologies in the field and deploy them within days or weeks.”

These kinds of fast production capabilities are something the US has always struggled with. “We produce good stuff, but also, we spend a long time doing it right,” Connor says. “The Ukrainians have shown that the ability to have something that is low- cost, easy to produce and easy to update, and able to adapt to changing conditions is crucial.”

This lesson may be evidenced in the Replicator programme itself. “If you talk to folks who ran early parts of the programme, it was as much about breaking the process, as [designing] the drones themselves,” says Pettyjohn. “It was intended to establish the procedures and norms for buying things that you don’t tend to keep for a long time.”

“Most of the stuff the US military buys is around for decades and is built to last, and the Replicator programme was about trying to short-circuit this long arduous process and get Congress and the services used to spending money on things that probably would be obsolete within a few years.”

According to Pettyjohn, this caused a great deal of consternation on the part of congressional appropriators. “Even though the dollar amounts were really, really small for the DoD, because it was being spent in a more flexible way … I think senior defence officials, including former Deputy Secretary Hicks, were on the Hill [Congress] four or five times a month justifying what they were doing.”

Cultural resistance among the military to attack drones was a problem 80 years ago and remains a problem now. “There is a developing culture of resistance to drones in the USAF, because CCAs are seen as more of a replacement for a crewed fighter,” she says. “But for smaller drones I think the cultural resistance among the ground forces to drone dominance is more down to hubris on the part of the US and Western NATO countries that their ground forces fight differently than the Ukrainians or Russians and their sophisticated combined-arm manoeuvres would restrict the drones’ acitivities.”

However, this cultural resistance extends, conversely, to the threat posed by drones to US forces themselves. “I do not think they grasp the scale of the threat that they are going to face from these drones, which can be bought very cheaply and are very useful,” adds Pettyjohn. “When you deal with a couple at a time, it is one problem but when you deal with dozens or hundreds, it becomes a very different problem, and it is much more difficult to defend yourself.”

High above visitors to the US Navy’s National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida hangs the sole surviving TDR-1. In the end, the similarities in the challenges faced by the US in fighting Japan in the Pacific in 1942 and China in 2025 mean that the US military has turned to the assault drone as the solution in both situations.

However, the feasibility of Poparo’s vision of a ‘hellscape’ remains in doubt and, with the future

of the Replicator programme uncertain, it is clear that the Pentagon has not fully taken on board the lessons learned from Project Option.

August 11, 2025

Published by BBC Future, translated into Spanish for BBC Mundo and widely syndicated, and translated into Portuguese by Brazilian newspaper Correio Braziliense… My latest feature…The upstart company that wants to build the wor

Read my latest piece for BBC Future online here

Or in Spanish on BBC Mundo here which was syndicated to sites like Yahoo.com and MSN.com.

Or into Portuguese by the daily Brazilian newspaper Correio Braziliense here.

Read my latest for BBC Future: The upstart company that wants to build the world’s largest aircraft

Read my latest piece for BBC Future online here

Or in Spanish on BBC Mundo here which was syndicated to sites like Yahoo.com and MSN.com.

Or into Portuguese by the daily Brazilian newspaper Correio Braziliense here.

July 12, 2025

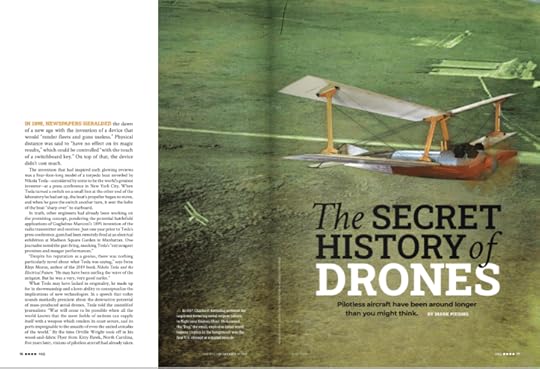

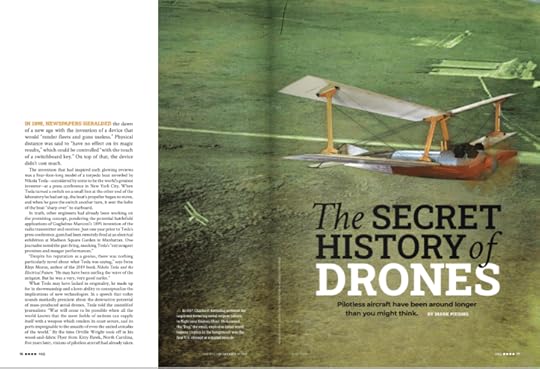

Check out my Aerospace Media Award winning article for The Smithsonian’s Air and Space magazine: The Secret History of Drones

Pilotless aircraft have been around longer than you might think.

Pilotless aircraft have been around longer than you might think.I wrote this long read for The Smithsonian/ National Air and Space Museum and it won an Aerospace Media Award for The Best Un-Manned Systems Submission (sponsored by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems).

I will publish the article in full below soon, but in the meantime, please read my four double-page features (and see the fantastic historical photographs) by…

Clicking here for the complete article

Clicking here for the digital edition of the magazine

With another feature waiting for a pub date and still another just completed, it is great to be described in my bio as “a frequent contributor” to the magazine.

It was great to write this for Publishers Weekly…U.K. Publishing in 2025: Harnessing the Power of AI

I was delighted to write this piece for Publishers Weekly in the States.

It felt great to be writing about publishing again.

Read the original here – or in full below.

Check out my comment pieces for The Bookseller here.

Check out my writing for Publishing Perspectives here.

Artificial intelligence continues to insinuate itself into various aspects of publishing worldwide, and the scale and speed at which the technology is evolving can be daunting even to experts. The sea change has some in the U.K. publishing scene looking at U.S. domination of the AI market and worried about falling behind.

“What we’ve seen is a period of real concern about the impact of the technology, but the mood now seems to be more pragmatic,” says George Walkley, a U.K. consultant focused on AI and publishing who previously spent 15 years at Hachette. “I think there are really interesting things happening in the U.K. book scene.”

Vicky Hartley, deputy managing director at Watkins Media, the parent company of fiction and nonfiction publisher Collective Ink, is using software from AI startup Storywise to automate submission workflows in an effort to ensure that editors don’t lose good queries in crowded inboxes. Storywise claims its software can match the taste of individual editors with manuscripts and summarize key information, create synopses, provide comp titles, and even offer critiques. But it doesn’t decide what to publish—that remains a human decision.

Hartley praises the software as helping the company “reject fewer books at the wrong stage”—i.e., after several rounds of resource-consuming human assessment. “And the books that make it through are better suited to the publisher and more likely to result in a contract.”

Entrepreneur Georgia Kirke has developed Clio, an AI-enabled writing platform that allows authors to speak their business books into existence rather than type them out. As writers respond to prompts about business objectives, target audience, and key topics, the software functions as a technological ghostwriter, editing and structuring the book. It speeds up the creation of the first draft, after which, “we have a human editing team, human proofreaders, human book designers, and human marketers,” Kirke says. “It’s an AI-human collaboration.”

It helps that Clio primarily produces business and self-help books, which are relatively formulaic. “We distilled the key qualities of a good nonfiction book together into a formula that could be repeated by anybody with a strong message at any point in their career,” Kirke says. “They don’t even have to have writing skill.”

Clio Books currently has more than 200 clients writing books with the software. Some of the books are still in draft form, some are moving through the editing process, and others are nearly ready for production, “There is a stereotype that publishing somehow isn’t innovative or doesn’t embrace new things,” Kirke says. “I haven’t found that to be true.”

Library and academic communities have been among the first to embrace new technologies in publishing. Looking to shake up those markets in the U.K. is subscription-based digital library Perlego, which holds a collection of more than one million books covering 1,000 topics. The challenge is that users can get lost in a sea of information, which is often presented without appropriate sourcing or citations. Here, AI has come to the rescue via Perlego’s SmartSearch technology, which allows semantic-language searches that also deliver citations. “You will know exactly where all the information is from because you will have all the sources,” says Perlego cofounder Gauthier Van Malderen. “You can search for a book. You can highlight and annotate it. You can create all your references.”

Oxford University Press also employs AI to help users navigate its digital law library of 600 books and 10,000 journal articles. The service, dubbed Oxford Law Pro, is an AI-driven “research assistant” that aims to expedite how attorneys search case law for precedents. Still, says John Campbell, product strategy director for OUP’s academic division, while the AI is impressive, it can’t yet replace traditional research.

Looking at the big picture, Walkley is upbeat about the future of innovation in digital publishing in the U.K. “The technology isn’t perfect,” he says, “but it isn’t going away either, and people are seeing use cases where they can get some good things from AI.”

Mark Piesing is a freelance journalist and author in Oxford, U.K.

A version of this article appeared in the 06/09/2025 issue of Publishers Weeklyunder the headline: The Power of AI

Check out my Aerospace Media Award winning article for The Smithsonian’s Air and Space magazine: The Secret History of Drones

Pilotless aircraft have been around longer than you might think.

Pilotless aircraft have been around longer than you might think.I wrote this long read for The Smithsonian/ National Air and Space Museum and it won an Aerospace Media Award for The Best Un-Manned Systems Submission (sponsored by General Atomics Aeronautical Systems).

Read it in full below or by click on the links below

Clicking here for the complete article

Clicking here for the digital edition of the magazine

Pilotless aircraft have been around longer than you might think.

In 1898, newspapers heralded the dawn of a new age with the invention of a device that would “render fleets and guns useless.” Physical distance was said to “have no effect on its magic results,” which could be controlled “with the touch of a switchboard key.” On top of that, the device didn’t cost much.

The invention that had inspired such glowing reviews was a four-foot-long model of a torpedo boat unveiled by Nikola Tesla—considered by some to be the world’s greatest inventor—at a press conference in New York City. When Tesla turned a switch on a small box at the other end of the laboratory he had set up, the boat’s propeller began to move, and when he gave the switch another turn, it sent the helm of the boat “sharp over” to starboard.

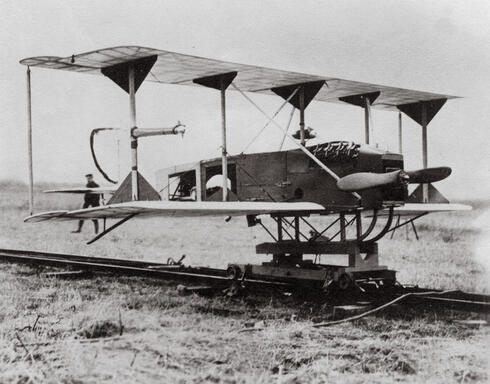

The Bug was launched from a four-wheeled dolly that ran on a portable track.

The Bug was launched from a four-wheeled dolly that ran on a portable track.In truth, other engineers had already been working on the promising concept, pondering the potential battlefield applications of Guglielmo Marconi’s 1895 invention of the radio transmitter and receiver. Just one year prior to Tesla’s press conference, guns had been remotely fired at an electrical exhibition at Madison Square Garden in Manhattan. One journalist noted the gun firing, mocking Tesla’s “extravagant promises and meager performances.”

“Despite his reputation as a genius, there was nothing particularly novel about what Tesla was saying,” says Iwan Rhys Morus, author of the 2019 book Nikola Tesla and the Electrical Future. “He may have been surfing the wave of the zeitgeist. But he was a very, very good surfer.”

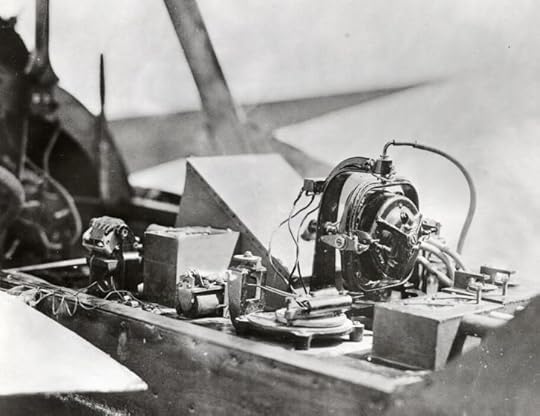

The Bug relied on pneumatic and electrical controls to reach its target.

The Bug relied on pneumatic and electrical controls to reach its target.What Tesla may have lacked in originality, he made up for in showmanship and a keen ability to conceptualize the implications of new technologies. In a speech that today sounds markedly prescient about the destructive potential of mass-produced aerial drones, Tesla told the assembled journalists: “War will cease to be possible when all the world knows that the most feeble of nations can supply itself with a weapon which renders its coast secure, and its ports impregnable to the assaults of even the united armadas of the world.” By the time Orville Wright took off in his wood-and-fabric Flyer from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, five years later, visions of pilotless aircraft had already taken hold within the fledgling aviation community.

“The growth of unpiloted aviation and radio went hand in hand,” says Roger D. Connor, a curator in the National Air and Space Museum’s aeronautics department. “In World War I, the ability to direct artillery by radio drives the development of aircraft. The growth of unpiloted aviation is no different.”

Staff at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Ohio built a full-size replica.Dull, Dirty, and Dangerous

Staff at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Ohio built a full-size replica.Dull, Dirty, and DangerousElmer Sperry was an American inventor whose wide-ranging interests included the development of gyroscopic stabilizers to reduce the lurching of U.S. Navy ships at sea. He became intrigued with the idea of radio-controlled aircraft, but recognized that stabilization during flight would be essential to make it work. With the assistance of the Navy, Sperry and his son Lawrence developed an automatic gyrostabilizer in 1913, which enabled a Curtiss flying boat to fly straight and level without input from the human pilot on board. On June 18, 1914, Lawrence Sperry and his French assistant Emil Cachin demonstrated the invention at the Aero Club of France’s airplane safety competition. As Sperry stood on one wing of his pilotless flying craft, Cachin on the other, one of the judges on the ground cried out: “Mais, c’est inoui!” (“But that’s unheard of!”). Needless to say, Sperry won the competition’s first prize—50,000 francs ($10,000)—and became famous overnight.

In the 1930s, the British converted biplanes into radio-controlled target drones, beginning with the Fairey Queen IIIF Mk.IIIB (on the aft deck of a Royal Navy vessel).

In the 1930s, the British converted biplanes into radio-controlled target drones, beginning with the Fairey Queen IIIF Mk.IIIB (on the aft deck of a Royal Navy vessel).Wars accelerate the development of technology, and the drone is no exception. After World War I erupted and the Western Front descended into stalemate, the British decided to take advantage of Sperry’s breakthrough and build a top-secret facility to design the first generation of drones. British engineer, inventor, and television pioneer Archibald Low was given the job, and the Germans considered him to be so capable, they attempted to kill him twice (the second time by a poisoned cigarette).

Low entered the history books with his engineering project known as “Aerial Target.” Intended to be an aerial torpedo to be used against Zeppelin bombers and U-boats, it had been named Aerial Target to fool the Germans into thinking it was just fodder for testing anti-aircraft weapons. Low’s flying torpedo took off for the first time under radio control in March 1917, a feat that later saw him recognized as the “father of radio guidance systems” and, more recently, “father of the drone.” The initial demonstration was far from perfect—it ended with a spectacular crash landing.

“A great number of the pieces are in place for remotely piloted aircraft pretty early, by the beginning of World War I,” says Connor. “But what was really lacking was the ability to control the drones effectively, and this was down to the reliability of the radio signals. In so many cases, like the United States’ Kettering aerial torpedo, these projects just devolve into what might be considered a flying bomb. Even Low demonstrated only a degree of control with his Aerial Target: He nearly killed observers on the ground when it crashed during its demonstration flight.”

Indeed, a similar misfortune befell the aforementioned Kettering aerial torpedo—known as the “Bug”—during its demonstration flight at a secluded airfield near Dayton, Ohio, where a group of U.S. Army VIPs had gathered to see the first U.S. “guided missile” in action. The miniature wood biplane—named for its inventor Charles F. Kettering—was packed with explosives. A gyro helped maintain the stability of the craft, and a barometer sent signals to small flight controls that were moved by a system of cranks and a bellows (from a player piano) for altitude control. But after taking off, the Bug pivoted off course, at which point it swooped down and headed straight for the reviewing stands, causing officials to dive for cover under the bleachers. Fewer than 50 Bugs were manufactured, and they never saw combat.

Despite these somewhat disappointing initial outcomes, the development of drones continued after the war, while tech nerds of the era remained captivated by radio’s potential. In 1922, Hugo Gernsback, editor of the first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, published a book, Radio for All, which had a “really amazing frontispiece,” says Rhys Morus. “It’s a picture of a man of the future, sitting in the future office…and through the window, there is a flying machine in the sky labeled ‘radio-controlled aeroplane.’ ”

Prior to the end of World War I, French engineers had succeeded in launching a radio-controlled Voisin biplane that stayed aloft for 51 minutes, traveling more than 60 miles. The tricky business of takeoff and landing, however, was still handled by pilots on board. That changed in 1923, when engineer Maurice Percheron and pilot Captain Max Boucher designed, built, and remotely piloted a Voisin Type 10—a two-seat bomber—from takeoff to landing. The feat had been made possible through the ongoing augmentation of Sperry’s autopilot design and the introduction of a tactile land sensor to flatten out the rate of descent. Despite this accomplishment, the French canceled the project.

The Curtiss-built Hewitt-Sperry automatic airplane (“Flying Bomb”) sits on its launch catapult in 1918. The aircraft crashed after flying only 100 yards, and the design was discontinued.

The Curtiss-built Hewitt-Sperry automatic airplane (“Flying Bomb”) sits on its launch catapult in 1918. The aircraft crashed after flying only 100 yards, and the design was discontinued.Pilotless aircraft, flying slow and straight, hardly seemed like a viable weapon. It would fall to Great Britain in the ensuing decade to figure out a practical military application for the technology. In the 1930s, British military leaders realized that naval anti-aircraft gunners were having a tough time hitting fast-turning aircraft from a warship that was also maneuvering. The solution was the de Havilland Queen Bee drone. “It’s this requirement for anti-aircraft training that really drives the drone industry and establishes it as a viable aerospace niche during the ’30s,” says Connor.

Researchers at Britain’s Royal Aircraft Establishment had continued Low’s work after the war, culminating in the development of the Queen Bee, which resembled the legendary de Havilland Tiger Moth trainer, albeit without a pilot. The enclosed rear cockpit was fitted with radio-control gear that included pneumatically operated servo units linked to the elevator controls and rudder. Engineers also replaced the Tiger Moth’s metal-frame fuselage with a less expensive one made of spruce and plywood, which also made the drone buoyant if it had to ditch in the ocean.

The McDonnell Aircraft TD2D Katydid target drone had a similar configuration. During the war, Germany used pulse jets to power V-1 flying bombs.

The McDonnell Aircraft TD2D Katydid target drone had a similar configuration. During the war, Germany used pulse jets to power V-1 flying bombs.

After World War II, the Radioplane Company began experimenting with pulse jets, mounting them on the backs of drones to replace propellers.

After World War II, the Radioplane Company began experimenting with pulse jets, mounting them on the backs of drones to replace propellers.“Projects like the Queen Bee should get the credit for being the first viable application of drones, which up to that point had been more or less laboratory work,” says Connor. Drones had begun to develop the reputation—repeated as a mantra throughout the 20th century—as the workhorses for missions that were too dull, dirty, and dangerous for piloted aircraft.

The U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, William Standley, saw the Queen Bee drone at work and concluded there was an “urgent need in the fleet” to have one of their own. It was Commander Delmer Fahrney’s job to get them one, even if the British refused to share their remote-control technology with their overseas cousins.

A TDR-1 is prepped for an attack against an enemy target in Rabaul during World War II. Controlled from a TBM-1C Avenger aircraft, the Edna III carried a 1,000-pound bomb.

A TDR-1 is prepped for an attack against an enemy target in Rabaul during World War II. Controlled from a TBM-1C Avenger aircraft, the Edna III carried a 1,000-pound bomb.Fahrney turned full-scale obsolete aircraft like the Curtiss N2C Fledgling trainers into drones for aerial targets, controlled by pilots in other airplanes. In 1939, one squadron was deployed for the Navy on the West Coast, and two years later on the East.

But there were complications. “Many of these aerial targets were unreliable because they were obsolete and poorly maintained,” says Connor. “They would make a pass of a battleship during gunnery practice and sustain damage but remain in the air.” If this happened, the crew of the control airplane had Tommy guns, and they were expected to fly alongside the compromised drone and shoot it down.

![Yank magazine photo (color version) of Marilyn Monroe as Norma Jeane Dougherty with a RP-5 prop. [edit]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1752373056i/37058736._SY540_.jpg) Norma Jeane Dougherty—later known as Marilyn Monroe—was discovered by a photographer while she worked at Radioplane (seen here assembling an OQ-3 drone).

Norma Jeane Dougherty—later known as Marilyn Monroe—was discovered by a photographer while she worked at Radioplane (seen here assembling an OQ-3 drone).Army anti-aircraft gunnery was less complex than the Navy’s in that the gunners were stationary when they were shooting. Army gunners wanted their own smaller target drones, and at that time, there was only one man to talk to about this in the U.S. Reginald Denny had been a Royal Air Force pilot at the end of World War I, when he emigrated to the U.S. and became a successful Hollywood actor. But he continued to be fascinated with aviation, and he went into business manufacturing model aircraft for the hobbyist market.

In 1935, Denny decided to add radio control to his model aircraft despite the challenge of finding equipment light and small enough to fit on his airplanes. His success in doing so soon attracted the attention of the Army. By 1937, Denny was developing his Radioplane for them, and two years later, the Radioplane OQ-2 became the first mass-produced UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) in the U.S. The next model, the OQ-3, became the most widely used target drone by U.S. forces, with more than 9,400 built during World War II.

But the existence of drones was still a secret and would remain so for a few more years. “It had not filtered into public consciousness because its potential as a weapon system was still driving a high level of secrecy, and the fear that the Germans might employ this technology against us,” says Connor.

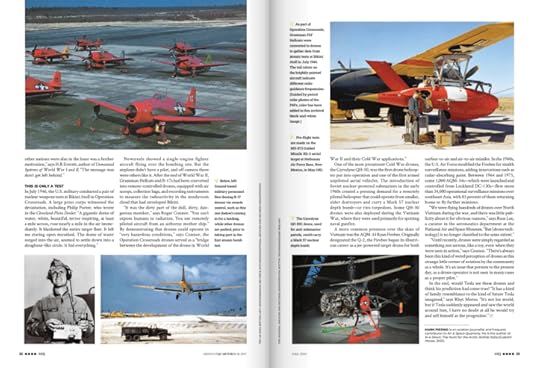

As part of Operation Crossroads, Grumman F6F Hellcats were converted to drones to gather data from atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in July 1946. The tail colors on the brightly painted aircraft indicate different radio guidance frequencies. (Guided by period color photos of the F6Fs, color has been added to this archival black-and-white image.)

As part of Operation Crossroads, Grumman F6F Hellcats were converted to drones to gather data from atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in July 1946. The tail colors on the brightly painted aircraft indicate different radio guidance frequencies. (Guided by period color photos of the F6Fs, color has been added to this archival black-and-white image.)Meanwhile, the U.S. had made progress militarizing the technology against Germany. The Anvil and Aphrodite projects turned war-weary Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses (for the Army) and Consolidated B-24s (for the Navy) into flying bombs by filling them with 20,000 pounds of explosives and then flying into heavily defended or very hard targets, such as Germany’s U-boat pens and long-range artillery sites. At the start of these programs, a human pilot had to do the hazardous job of flying these lumbering machines off the runway, and then parachute out. By the end, a pilot could perform the whole operation remotely.

Boeing B-17 drones flew via remote control, such as this one coming in for a landing, while other drones are parked, prior to taking part in the first atomic bomb test.

Boeing B-17 drones flew via remote control, such as this one coming in for a landing, while other drones are parked, prior to taking part in the first atomic bomb test.

Ground-based military personnel flew Boeing B-17 drones via remote control.

Ground-based military personnel flew Boeing B-17 drones via remote control.The U.S. Navy then planned to build 5,000 of their own kamikaze drones. The TDR-1 was a large, modern-looking, twin-engine wood-and-metal unpiloted aircraft capable of carrying a 2,000-pound bomb or torpedo and hitting a target 425 miles away. It was controlled from a Grumman Avenger torpedo bomber flying nearby. Around 190 TDR-1s were built and, before the project was cancelled, 50 of the drones saw action, with 31 hits on ships, airfields, and bridges. “They may sound impressive, but they were largely unsuccessful,” says Connor. “They didn’t cause much damage, and the results were pretty disappointing for most of these programs compared to the amount of resources put into them.” However, one of the really important things about these drone programs is the development of television to fly them. The controller of the TDR-1 had a five-inch screen to guide the aircraft to its target.

That’s why, despite their underwhelming performance in the field, “drones and their ever-improving supporting technology continued to show great promise—and the knowledge that other nations were also in the hunt was a further motivation,” says H.R Everett, author of Unmanned Systems of World War I and II. “The message was don’t get left behind.”

This is only a testIn July 1946, the U.S. military conducted a pair of nuclear weapons tests at Bikini Atoll in Operation Crossroads. A large press corps witnessed the devastation, including Philip Porter, who wrote in the Cleveland Plain Dealer:“A gigantic dome of water, white, beautiful, terror inspiring, at least a mile across, rose nearly a mile in the air immediately. It blanketed the entire target fleet. It left me staring open mouthed. The dome of water surged into the air, seemed to settle down into a doughnut-like circle. It hid everything.”

Newsreels showed a single-engine fighter aircraft flying over the bombing site. But the airplane didn’t have a pilot, and off camera there were others like it. After the end of World War II, Grumman Hellcats and B-17s had been converted into remote-controlled drones, equipped with air scoops, collection bags, and recording instruments to measure the radioactivity in the mushroom cloud that had enveloped Bikini.

Pre-flight tests are made on the MX‑873 Guided Missile XQ-2 aerial target at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, in May 1951.

Pre-flight tests are made on the MX‑873 Guided Missile XQ-2 aerial target at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, in May 1951.“It was the dirty part of the dull, dirty, dangerous moniker,” says Roger Connor. “You can’t expose humans to radiation. You use remotely piloted aircraft from an airborne mother ship.” By demonstrating that drones could operate in “very hazardous conditions,” says Connor, the Operation Crossroads drones served as a “bridge between the development of the drone in World War II and their Cold War applications.”

One of the most prominent Cold War drones, the Gyrodyne QH-50, was the first drone helicopter put into operation and one of the first armed unpiloted aerial vehicles. The introduction of Soviet nuclear-powered submarines in the early 1960s created a pressing demand for a remotely piloted helicopter that could operate from smaller, older destroyers and carry a Mark 57 nuclear depth bomb—or two torpedoes. Some QH-50 drones were also deployed during the Vietnam War, where they were used primarily for spotting naval gunfire.

A more common presence over the skies of Vietnam was the AQM-34 Ryan Firebee. Originally designated the Q-2, the Firebee began its illustrious career as a jet-powered target drone for both surface-to-air and air-to-air missiles. In the 1960s, the U.S. Air Force modified the Firebee for stealth surveillance missions, adding innovations such as radar-absorbing paint. Between 1964 and 1975, some 1,000 AQM-34s—which were launched and controlled from Lockheed DC-130s—flew more than 34,000 operational surveillance missions over southeast Asia, with 83 percent of them returning home to fly further missions.

“We were flying hundreds of drones over North Vietnam during the war, and there was little publicity about it for obvious reasons,” says Russ Lee, a curator in the aeronautics department at the National Air and Space Museum. “But [drone technology] is no longer classified to the same extent.”

The Gyrodyne QH-50C drone, used for anti-submarine patrols, could carry a Mark 57 nuclear depth bomb.

The Gyrodyne QH-50C drone, used for anti-submarine patrols, could carry a Mark 57 nuclear depth bomb.“Until recently, drones were simply regarded as something not serious, like a toy, even when they were seen in action,” says Connor. “There’s always been this kind of weird perception of drones as this strange little corner of aviation by the community as a whole. It’s an issue that persists to the present day, as a drone operator is not seen in many cases as a proper pilot.”

In the end, would Tesla see these drones and think his prediction had come true? “It has a kind of family resemblance to the kind of future Tesla imagined,” says Rhys Morus. “It’s not his world, but if Tesla suddenly appeared and saw the world around him, I have no doubt at all he would try and sell himself as the progenitor.”

July 9, 2025

I wrote this for History.com in the USA to mark the 75th anniversary of the Korean War : How the Korean War Supercharged Aerial Dogfighting

National Archives/Interim Archives/Getty Images

National Archives/Interim Archives/Getty ImagesAmerican Sabres and Soviet MiGs screamed through the skies, ushering in the jet age of warfare. Soviet pilots, who weren’t supposed to be there, fought covertly.

Read it in full below, or by reading the original here on History.com, the standalone website of The History Channel (USA only. VPN needed. Otherwise UK readers directed to Sky TV’s History.co.uk).

On December 17, 1950, six months into the Korean War, American F-86 Sabres and Soviet-built MiG-15s clashed in the skies over northwest Korea. It was the first known dogfight between swept-wing jet fighters, and it unfolded in an airspace soon to earn the ominous nickname “MiG Alley.”

The encounter would revolutionize aerial combat—and usher in the jet age of warfare.

“MiG Alley was the scene of the first large-scale, jet-on-jet combat in history,” says aviation historian Michael Napier, author of Korean Air War. These dogfights—waged in powerful new jet aircraft—took place at much higher altitudes and at far greater speeds than any aerial battles before. The rapid acceleration subjected pilots, many of them veterans of World War II, to much more disorienting G-forces. “It represented a dramatic break from [that conflict’s] piston-engine dogfights.”

U.S. Jetfighter Ace of KoreaGet to know Colonel Ralph Parr, whose three-decade Air Force career encompassed three wars and five combat tours.0:00

MiG Alley, a wedge-shaped mountainous area stretching along the Yalu River, traced North Korea’s border with Chinese Manchuria. It earned its name from the great number of the North’s MiG-15 fighters (often piloted covertly by Soviet airmen) that lurked in the area, sweeping down to ambush American aircraft in the battle for air supremacy over the Korean Peninsula.

Although the Soviet Union was not a named combatant in the Korean War, these secretive Soviet flyers played a pivotal role. Their presence raised the conflict from a regional showdown to a perilous Cold Warflashpoint—one that saw superpowers shadow-boxing for dominance in the skies.

Dogfighting Goes Jet SpeedThe iconic fighter aircraft of MiG Alley were the F-86 Sabreand the MiG-15. According to Napier, “they looked so similar in a dogfight that there is more than one case of pilots on either side shooting down their own wing man by mistake.”

The Sabre and the MiG, both single-seat, single-engine fighter jets, were among the first fighters to take advantage of a revolutionary aerodynamic breakthroughpioneered by the Nazis: swept wings. Angled rearward from the fuselage rather than extending straight out, these wings dramatically improved high-speed performance, especially as aircraft approached the sound barrier.

Re-defining Air Combat to Become “Jet Ace”In the skies above North Korea, a new kind of air war is raging at 500mph. Jet vs. jet dogfighting for the first time in history.0:00

While generally well matched, the two machines differed in a few significant ways. The MiG-15 was smaller, lighter and had a better rate of climb and higher acceleration. Its three relatively slow-firing cannons “could take a wing off a Sabre,” says Napier, and it performed better at altitudes above 30,000 feet. “If a MiG pilot was ever in trouble in a dogfight, all they had to do was to fly up on full power.” The Sabre didn’t have that option.

Below 30,000 feet, however, the tables turned. Designed for dogfights, the Sabre was more maneuverable at lower altitudes and, crucially, it had a tighter turn than the MiG. It carried six .50-caliber machine guns that could spit out an impressive 1,200 shots per minute and a radar gun sight that automatically measured the distance to the chosen target, a feature the MiGs lacked. But its less-powerful guns couldn’t hurt a robust MiG unless close by.

“If a Sabre was engaged by a MiG, all the pilots had to do was to pull as hard they could into a really tight turn and spiral down away from the MiG,” notes Napier.

The Aces of MiG AlleyIn some ways, Korean War dogfighting was no different from that of World War II. As in the Battle of Britain, pilots relied on their eyes and reflexes—not radar—to spot enemy aircraft. Battles were fought at close range, with machine guns and cannons rather than missiles fired from a distance.

“World War II veterans would have certainly recognized these close-in, turning, maneuvering dogfights,” says Napier. “They’d recognize the importance of a wingman staying with them to cover their tail.”

As in the previous war, pilots on both sides of the Korean conflict competed fiercely to earn the title of “ace”—a designation typically awarded to those who shot down five or more enemy aircraft. U.S. Captain James Jabarabecame the world’s first jet-versus-jet ace on May 20, 1951. Two years later, Captain Joseph McConnell Jr. achieved the distinction of being the first double ace, ultimately downing 16 enemy jets. (After being hit and forced to bail into enemy waters after his eighth win, he returned to the skies the next day to notch his ninth.) The top Soviet ace of the war was Colonel Yevgeny Pepelyayev, with 23 victories.

Korea Vet Recalls WarVeteran Sherman Pratt recalls the tough conditions during the Korean War.0:00

Split-Second Decisions at 700 mphIn many other ways, the dogfighting in MiG Alley marked a sharp departure from World War II. The jets flew significantly faster (approaching 700 mph) and operated at higher altitudes with superior climb rates. “The dogfights in MiG Alley were fought from the deck [ground] up to 50,000 feet, which was nearly twice the [altitude] range as during World War II,” explains Napier.

This meant that two aircraft engaged in a dogfight closed in on each other much faster than in piston-engined aircraft. “If you are flying a jet plane you have seconds to see another jet [and] you have seconds to make decisions,” he says. “Have they seen me? Am I going to attack or go on the defense? This sort of thing would be very different for a Mustang pilot in World War II.”

Plus, jet fighting subjected pilots to far greater G-forces than ever before, reducing blood flow to the brain and leading to tunnel vision or even blackouts. For the first time, American aircraft like the Sabre were equipped with anti-G suits to help counteract those effects—a crucial advantage their Soviet counterparts lacked.

For pilots, dogfighting in the jet age proved to be fast, deafening and often terrifying—not to mention physically draining due to the relentless G-forces. “When the adrenaline and tunnel vision kicks in, you are just thinking about ‘how do I kill this guy?’” says Napier.

In this fast-paced, life-or-death, three-dimensional chess game, pilots had to process possibilities at lightning speed. Looming fears about flying over enemy territory—or brutal treatment they would receive if captured—were often pushed aside in the heat of combat, as they streaked by enemy aircraft and dodged near-misses. “You just feel immortal, invulnerable and unbeatable,” says Napier.

What Caused the Korean War and Why Did the U.S. Get Involved? The Global Stakes of MiG Alley

The Global Stakes of MiG AlleyIn MiG Alley, the stakes extended far beyond the Korean Peninsula; they reflected a broader global reckoning. As the Cold War emerged, two new superpowers—the United States and the Soviet Union—stood armed with atomic weapons capable of unimaginable destruction. The Korean War became the first major test of this new geopolitical landscape, pitting communist forces (North Korea, backed by Soviet arms) against democratic ones (South Korea, supported by the U.S.-led United Nations).

Since the Soviet Union wasn’t officially a belligerent in the Korean War, its pilots attempted to disguise their identity by speaking in Korean or Chinese over the radio. But in the chaos of battle, American pilots sometimes glimpsed them in cockpits and heard them speak Russian over their radios. While their presence in MiG Alley became an open secretamong U.S. airmen, the American public was kept in the dark to avoid calls for escalating the conflict. For similar reasons, American pilots were told not to fly into China, even if they frequently disobeyed it in pursuit of another kill. And Soviet pilots who were shot down over American-controlled territory killed themselvesrather than risk capture—and exposure.

The stakes ran high for the United States as well. Maintaining air superiority over Korea was seen as essential to winning the war. Not only was the U.S. fighting Soviet influence, but its bombers were also fighting to stop Chinese reinforcements and equipment from crossing the Yalu River into North Korea. At the same time, they aimed to prevent that nascent communist regime from building its own airfields on the Korean Peninsula.

The Korean War also represented a pivotal moment for the U.S. Air Force itself. Having only gained independence from the U.S. Army in 1947, the fledgling branch saw the conflict as a proving ground—a chance to demonstrate its effectiveness and establish itself as a dominant force in modern warfare.

MiG Alley, in particular, became the crucible for modern air combat. “This is where Top Gun and Red Flag came from,” says Napier. “It’s where the F-16 and F-18 came from as well, with their incredible turning performance that allows them to get in close and fight.”

Yet the legacy of MiG Alley carries a somber weight. More than 30 American Sabre pilotswho were shot down are still missing, and efforts to locate and recover their remains continue to this day.

My latest for History.com: How the Korean War Supercharged Aerial Dogfighting

National Archives/Interim Archives/Getty Images

National Archives/Interim Archives/Getty ImagesAmerican Sabres and Soviet MiGs screamed through the skies, ushering in the jet age of warfare. Soviet pilots, who weren’t supposed to be there, fought covertly.

Read it in full below, or by reading the original here (USA only, VPN needed otherwise).

On December 17, 1950, six months into the Korean War, American F-86 Sabres and Soviet-built MiG-15s clashed in the skies over northwest Korea. It was the first known dogfight between swept-wing jet fighters, and it unfolded in an airspace soon to earn the ominous nickname “MiG Alley.”

The encounter would revolutionize aerial combat—and usher in the jet age of warfare.

“MiG Alley was the scene of the first large-scale, jet-on-jet combat in history,” says aviation historian Michael Napier, author of Korean Air War. These dogfights—waged in powerful new jet aircraft—took place at much higher altitudes and at far greater speeds than any aerial battles before. The rapid acceleration subjected pilots, many of them veterans of World War II, to much more disorienting G-forces. “It represented a dramatic break from [that conflict’s] piston-engine dogfights.”

U.S. Jetfighter Ace of KoreaGet to know Colonel Ralph Parr, whose three-decade Air Force career encompassed three wars and five combat tours.0:00

MiG Alley, a wedge-shaped mountainous area stretching along the Yalu River, traced North Korea’s border with Chinese Manchuria. It earned its name from the great number of the North’s MiG-15 fighters (often piloted covertly by Soviet airmen) that lurked in the area, sweeping down to ambush American aircraft in the battle for air supremacy over the Korean Peninsula.

Although the Soviet Union was not a named combatant in the Korean War, these secretive Soviet flyers played a pivotal role. Their presence raised the conflict from a regional showdown to a perilous Cold Warflashpoint—one that saw superpowers shadow-boxing for dominance in the skies.

Dogfighting Goes Jet SpeedThe iconic fighter aircraft of MiG Alley were the F-86 Sabreand the MiG-15. According to Napier, “they looked so similar in a dogfight that there is more than one case of pilots on either side shooting down their own wing man by mistake.”

The Sabre and the MiG, both single-seat, single-engine fighter jets, were among the first fighters to take advantage of a revolutionary aerodynamic breakthroughpioneered by the Nazis: swept wings. Angled rearward from the fuselage rather than extending straight out, these wings dramatically improved high-speed performance, especially as aircraft approached the sound barrier.

Re-defining Air Combat to Become “Jet Ace”In the skies above North Korea, a new kind of air war is raging at 500mph. Jet vs. jet dogfighting for the first time in history.0:00

While generally well matched, the two machines differed in a few significant ways. The MiG-15 was smaller, lighter and had a better rate of climb and higher acceleration. Its three relatively slow-firing cannons “could take a wing off a Sabre,” says Napier, and it performed better at altitudes above 30,000 feet. “If a MiG pilot was ever in trouble in a dogfight, all they had to do was to fly up on full power.” The Sabre didn’t have that option.

Below 30,000 feet, however, the tables turned. Designed for dogfights, the Sabre was more maneuverable at lower altitudes and, crucially, it had a tighter turn than the MiG. It carried six .50-caliber machine guns that could spit out an impressive 1,200 shots per minute and a radar gun sight that automatically measured the distance to the chosen target, a feature the MiGs lacked. But its less-powerful guns couldn’t hurt a robust MiG unless close by.

“If a Sabre was engaged by a MiG, all the pilots had to do was to pull as hard they could into a really tight turn and spiral down away from the MiG,” notes Napier.

The Aces of MiG AlleyIn some ways, Korean War dogfighting was no different from that of World War II. As in the Battle of Britain, pilots relied on their eyes and reflexes—not radar—to spot enemy aircraft. Battles were fought at close range, with machine guns and cannons rather than missiles fired from a distance.

“World War II veterans would have certainly recognized these close-in, turning, maneuvering dogfights,” says Napier. “They’d recognize the importance of a wingman staying with them to cover their tail.”

As in the previous war, pilots on both sides of the Korean conflict competed fiercely to earn the title of “ace”—a designation typically awarded to those who shot down five or more enemy aircraft. U.S. Captain James Jabarabecame the world’s first jet-versus-jet ace on May 20, 1951. Two years later, Captain Joseph McConnell Jr. achieved the distinction of being the first double ace, ultimately downing 16 enemy jets. (After being hit and forced to bail into enemy waters after his eighth win, he returned to the skies the next day to notch his ninth.) The top Soviet ace of the war was Colonel Yevgeny Pepelyayev, with 23 victories.

Korea Vet Recalls WarVeteran Sherman Pratt recalls the tough conditions during the Korean War.0:00

Split-Second Decisions at 700 mphIn many other ways, the dogfighting in MiG Alley marked a sharp departure from World War II. The jets flew significantly faster (approaching 700 mph) and operated at higher altitudes with superior climb rates. “The dogfights in MiG Alley were fought from the deck [ground] up to 50,000 feet, which was nearly twice the [altitude] range as during World War II,” explains Napier.

This meant that two aircraft engaged in a dogfight closed in on each other much faster than in piston-engined aircraft. “If you are flying a jet plane you have seconds to see another jet [and] you have seconds to make decisions,” he says. “Have they seen me? Am I going to attack or go on the defense? This sort of thing would be very different for a Mustang pilot in World War II.”

Plus, jet fighting subjected pilots to far greater G-forces than ever before, reducing blood flow to the brain and leading to tunnel vision or even blackouts. For the first time, American aircraft like the Sabre were equipped with anti-G suits to help counteract those effects—a crucial advantage their Soviet counterparts lacked.

For pilots, dogfighting in the jet age proved to be fast, deafening and often terrifying—not to mention physically draining due to the relentless G-forces. “When the adrenaline and tunnel vision kicks in, you are just thinking about ‘how do I kill this guy?’” says Napier.

In this fast-paced, life-or-death, three-dimensional chess game, pilots had to process possibilities at lightning speed. Looming fears about flying over enemy territory—or brutal treatment they would receive if captured—were often pushed aside in the heat of combat, as they streaked by enemy aircraft and dodged near-misses. “You just feel immortal, invulnerable and unbeatable,” says Napier.

What Caused the Korean War and Why Did the U.S. Get Involved? The Global Stakes of MiG Alley

The Global Stakes of MiG AlleyIn MiG Alley, the stakes extended far beyond the Korean Peninsula; they reflected a broader global reckoning. As the Cold War emerged, two new superpowers—the United States and the Soviet Union—stood armed with atomic weapons capable of unimaginable destruction. The Korean War became the first major test of this new geopolitical landscape, pitting communist forces (North Korea, backed by Soviet arms) against democratic ones (South Korea, supported by the U.S.-led United Nations).

Since the Soviet Union wasn’t officially a belligerent in the Korean War, its pilots attempted to disguise their identity by speaking in Korean or Chinese over the radio. But in the chaos of battle, American pilots sometimes glimpsed them in cockpits and heard them speak Russian over their radios. While their presence in MiG Alley became an open secretamong U.S. airmen, the American public was kept in the dark to avoid calls for escalating the conflict. For similar reasons, American pilots were told not to fly into China, even if they frequently disobeyed it in pursuit of another kill. And Soviet pilots who were shot down over American-controlled territory killed themselvesrather than risk capture—and exposure.

The stakes ran high for the United States as well. Maintaining air superiority over Korea was seen as essential to winning the war. Not only was the U.S. fighting Soviet influence, but its bombers were also fighting to stop Chinese reinforcements and equipment from crossing the Yalu River into North Korea. At the same time, they aimed to prevent that nascent communist regime from building its own airfields on the Korean Peninsula.

The Korean War also represented a pivotal moment for the U.S. Air Force itself. Having only gained independence from the U.S. Army in 1947, the fledgling branch saw the conflict as a proving ground—a chance to demonstrate its effectiveness and establish itself as a dominant force in modern warfare.

MiG Alley, in particular, became the crucible for modern air combat. “This is where Top Gun and Red Flag came from,” says Napier. “It’s where the F-16 and F-18 came from as well, with their incredible turning performance that allows them to get in close and fight.”

Yet the legacy of MiG Alley carries a somber weight. More than 30 American Sabre pilotswho were shot down are still missing, and efforts to locate and recover their remains continue to this day.

July 3, 2025

I WON an award at The Aerospace Media Awards in Paris last week!

In 2024 I was a finalist at The Aerospace Media Awards. In 2025 I WON at the Awards held in the historic Aero Club of France.

Thank you to all the judges who voted for my feature article for The Smithsonian’s Air and Space Quarterly on The Secret History of Drones, and the editorial team and the fantastic curators who made it possible.

Thanks to Peter Bradfield for tirelessly organising the Awards each year.