Alex Boyd's Blog

November 28, 2025

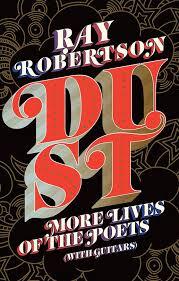

Excerpt: Dust, More Lives of the Poets by Ray Robertson

In 2016, Ray Robertson published Lives of the Poets (With Guitars), essays on the lives of different musicians, reviewed on Goodreads as “essays every bit as rollicking and energetic as many of the performers discussed.” There’s now a follow-up book called Dust: More Lives of the Poets (With Guitars) and I asked Ray if anything surprised him in researching the book, particularly if there was an overlooked musician. Ray provided the following excerpt about Danny Kirwan. The title of the book — Dust — is taken from his last song, recorded with Fleetwood Mac.

The legend of Fleetwood Mac goes something like this: in the beginning, there was Peter Green, Gibson Les Paul for hire in John Mayall’s mid-60’s Bluesbreakers, a brilliant but psychologically troubled musician who put the Mac together in 1967 (unassumingly naming it after his crack rhythm section of drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie) and played some staggeringly good guitar and wrote a bunch of great tunes before having his guitar god wings clipped by drugs and mental illness. Then, the story goes, the rudderless good ship Mac floundered on the seas of artistic and commercial irrelevancy for a few years in the early seventies before the pop gold renaissance that came when Lindsay Buckingham and Stevie Nicks joined the group at the decade’s midway point.

A legend, H.L. Mencken wrote, is a lie that has attained the dignity of age. Fleetwood Mac’s dark ages (1970-1974) are the lie that has become rock and roll legend, and principally because of the guitar playing, song writing, and singing talents of Danny Kirwan, who joined the group in the summer of 1968 as an alarmingly fresh-faced eighteen year old prodigy and was booted from the band four years later for drunken volatility—and by the age of thirty was out of the music business for good and on his way to full-blown alcoholism, debilitating mental illness, and eventual homelessness.

For a former member of a world-famous rock and roll band, Danny Kirwan is remarkably unknown, both in terms of the biographical details of his life and the wonderful music he created. He’s not a legend—he’s a mystery. Although he’s still waiting for the biography he deserves (I nominate Martin Celmins, Peter Green’s biographer and all round British blues authority), the music, as always, is there for us to listen to. The wife of Duster Bennett, the one-man British blues band, told Celmin, who wrote Duster Bennett’s biography, “Everything you want to know about Duster is all there in his music.” Maybe not everything—we still need that Danny Kirwan biography or documentary—but musicians do communicate most meaningfully through their music. That’s why they’re musicians. And whatever else Danny Kirwan was—alcoholic, mentally unstable, homeless and impoverished—he was foremost a musician. Danny Kirwan might be Fleetwood Mac’s mystery man, but it’s a mystery with a soundtrack that deserves to be heard.

September 27, 2025

Fan Mail: A Guide to What We Love, Loathe and Mourn, Jason Guriel

There’s a reason I’ve revisited Citizen Kane (including the commentary by Peter Bogdanovitch), listened to the 1966 recording of “River Deep, Mountain High,” and enjoyed a cartoon mashup of Godzilla and The Great Gatsby (Godzilla’s Monsterpiece Theatre, Tom Scioli). Jason Guriel’s Fan Mail: A Guide to What We Love, Loathe and Mourn finds ways to be openly but profoundly articulate about poetry, even as it delightfully blends this fascination with so many others. Guriel recommends whatever he finds worthy, and as someone who explores reading, music and film at a slow and steady pace, it’s an ideal book.

The book is broken up into a section for each (“Love,” “Loathe” and “Mourn”), but Guriel explores in an open-minded way, finding “blindingly good” moments in The Virgin Suicides, nestled in the section for not-so loved.

A big part of writing is making language sit up and dance, and a big part of reviewing a book is having an eye for the perfect quote. Guriel is quite capable of all of the above. In his piece on “selfie criticism,” he observes those pieces by critics like Pauline Kael and Lester Bang that seem “fired by irrefutable furnaces: living, breathing personalities.” He notes a character in a film has “a scarf so threadbare it could be a gnawed-off noose.” Guriel quotes Carl Wilson describing Vegas as somewhere that leaves him “feeling insignificant and micro-penised.” I can picture Guriel underlining sentences or otherwise making note of a line, and isn’t that the kind of reader every writer wants?

The book is largely literary. Around twenty years ago now I hosted a reading series and Elise Partridge dropped in alone to do a reading from out of town. I went out of my way to chat with her, something she observed was kind, but it was really just a pleasure to meet someone so thoughtful. She died far too young, and a poignant piece by Guriel reminds me to read more of her poetry, even as there’s a casual reference to a final book of poems by John Updike, Endpoint.

On criticism, we get the observation, “because he tends to be exacting, the reader tends to trust his praise.” Wise words, considering I’ve gone on YouTube to hear book comments like “prepare to have chilly feet, because this book will knock your socks off.” Guriel mentions those “practicing artists who can’t help but comment on their art,” and I’m grateful he’s another one.

The commonly repeated call to read widely can mean a “failure to make judgments,” and it’s better to “fall down a rabbit hole,” a sentiment that reminded me Wayson Choy once told me to start reading like a writer, meaning simply pay attention to the way others do it. Does reading widely absolutely always mean you fail to be critical? Of course not, but it’s worth examining our instincts and habits when it comes to improvement, and improvement is supposed to matter.

On book blurbs, I share his view so many of us are “stunning,” these words become meaningless. Guriel provides some insightful examples of the subtle difference between a quietly potent blurb and the ones that somehow trip over themselves, even in a few sentences. But that’s what language can do all too easily. I’m not sure I agree “If your name needs a qualifier, you’re not ready to write blurbs for people.” Surely not many of us can get a blurb from someone like Stephen King, and when drawing from the ocean of largely unknown writers for a blurb, it only makes sense to note the person’s qualifications. Maybe the best answer is simply to dispense with blurbs as they’re so obviously rounded up. There are also astute comments on “the politics of bios,” in another essay, considering the suggestions they hold if the reader bothers to read between the lines.

Regardless, here’s my blurb for this latest book by Jason Guriel: “Reading Fan Mail feels like a series of lucky breaks, like every time you head down to the pub the same articulate, interesting person has something new to tell you about.”

A bit short? I’ll work on it.

May 31, 2025

Lowfield by Mark Sampson

I have to admit, I didn’t have reading a horror novel set in PEI on my list of things to do for 2025, but I enjoyed Lowfield by Mark Sampson. Riley Fuller is a traumatized officer on leave when he inherits and explores his family’s ancestral property, an old house known as Applegarth. But does Fuller own the house, or does the house own him? With some of the shows I stream leaving a trail of undeveloped ideas, a novel set largely in one location appealed.

Sampson is a skilled writer. There’s enough detail here for the lives of the characters to feel convincing and real, but not so much it’s overbearing or tedious. The story is set around 1995, and Fuller cranks up his computer and begins a journal, “Dear Diary, or Journal, or whatever the fuck you are.” He’s exploring the whole e-mail thing, which everyone seems to be getting. It’s a novel that reminded me of John Wyndham because Wyndham is also capable of grounding his characters in a believable world as a way to help him sell and explore extraordinary ideas.

Sampson grew up on PEI and I can only assume that helps him add convincing detail. When an old journal in the house refers to “P. E. Island,” it feels very real. Characters say imperfect things and act imperfectly, but the book is also served well by its description. In a nightmare about jellyfish they’re “an army of glutinous, wine-dark blobs undulating in the salty waves, trailing their stinging tendrils behind them like torn skirts.”

I was surprised at some of the lines the book crosses, but it’s in the name of showing the corrupting, appalling influence of the house as it seizes Fuller with its own goals. It’s in the name of giving the book a potency it wouldn’t otherwise have, and the suggestion toxic masculinity is both exhausting and suffocating is not, wisely, spelled out for the reader. The house can repair itself even as corrupting visions about using others grip Fuller. Fair warning, the book finds its way to grotesque moments, and while that isn’t normally my cup of tea because I don’t have a strong stomach, in the hands of a skilled writer it has a purpose. I think there should be room in literary culture for horror and SF that examines large, universal ideas. All this is blended with some suggestions about the history of the province and the value of journalism.

There’s even a dash of literary criticism here when Fuller is sent an “impenetrable,” and “baffling” book of Canadian poetry. It contributes to Riley concluding “I hate reading,” but while I was tempted to suggest this was a heavy-handed moment — it does take the reader out of the story to some extent — I wondered if there’s meant to be an implied connection between Lowfield (a location eventually detailed in the book) and lowbrow, so that overall, the novel is perhaps suggesting some of the fault is in Fuller for not wanting to meet a book of poetry halfway.

I think there’s an argument to be made that in terms of theme, subtlety can be trusted to have more impact on the reader, in the end. The way these themes and ideas are not spelled out at a time direct statements are becoming more common is part of the value of Lowfield, which I’m very glad to have read.

May 3, 2025

Dear Ray

Recently, I enjoyed Dear Ray by Donna Dunlop, a long poem about Raymond Souster and his loss. Souster is a deserving poet and — though I never met him — someone I believe to be a deserving soul for a book like this one, and the poem finds many poignant moments in the long wait and decline that comes with illness. The title really says it all in that this is a concise, loving tribute.

The book is available from Contact Press.

April 4, 2025

Court of Memory, James McConkey

Sadly out of print for years — and I’m sorry to say it sat on my shelf for so long before I finished it, I no longer remember where I bought it — I found much to admire in this set of essays. McConkey has that rare quality: reverence. But what he does repeatedly through the book is humanize people, even immensely unlikeable ones. Here’s a passage from his World War Two experience on a mail orderly:

Version 1.0.0

Version 1.0.0“He had no friends and apparently desired none. The platoon thought him a sadist. Both in training camp and abroad he would postpone as long as possible the distribution of mail. Finally he would climb upon a table or file case and cry imperiously for silence. He dispensed the letters with a flourish, as if each were a token of his personal largess. If a soldier became angry at his tyrannical slowness, he was apt to leave his perch for an hour or so, taking all the mail with him; and he was known to have withheld letters for several days from any person who displeased him. His platoon wished to murder him; he was beaten up on at least one occasion. In eastern France he appeared late one night during a snowstorm at divisional headquarters, to which I had been transferred, to pick up some packages – a task anybody else would have delayed until the following morning. We saw him suddenly fall to the ground, threshing in helpless convulsions, his little packages skittering over the snow. A medic wedged open his mouth to keep him from biting off his tongue. The mail orderly had managed to conceal until that moment the fact that he was an epileptic. Afterwards, in tears, he begged that he be permitted to remain overseas with his buddies, to whom he thought himself of use; but he was immediately shipped home. I never heard of him again.”

March 23, 2025

The Mislaid Church

The church vanished, leaving an empty lot. One article after another had less and less to say. After the media had tired of it the locals still asked questions between each other, sitting in living rooms over coffee and near swings at the park. It was found ten years later: when they’d started to dig up the land in favour of a condo, it was there. At least, stone steps leading down were found. At the bottom of the steps a visitor felt a brief, dizzying flip and was upside down in the inverted church.

But it felt right side up, you see? The church was there, but in reverse, below the ground the way someone sitting in a pond has a reflection of the way they look from the waist up in the water. It was in a pocket of air that reached as high as a somewhat lazy bird in flight, a carved bowl of earth around the church with a smattering of occasional worms looking up, not visible to the eye, like odd stars. On two sides, eight wide steps took you up to a platform with the arched, double wooden doors. The steps are enough of an effort to give a person a slow transition moment before the doors. On the side of the church there’s the ramp, a man said they remembered their daughter running up and down it at two years old chattering to herself. He could never make out the words, and she was afraid but kept doing it. Joining the increasing group of people milling around before the steps one woman was heard to say, “More people have been to the moon than the hadal zone of the ocean.”

There was still a particular creak of floorboards just inside the door. Lighting was set up all around the church and made its muted way through the stained glass. I see you there, the images seemed to say to no one in particular. People wondered if the stone angels had stood in absolute darkness the entire ten years.

People walked around the outside of the church but found no cars, the parking lot vanished. If you climbed one of the two spires at the front and reached out a slim window, you could almost touch the ground.

February 6, 2025

Quicker Than the Eye, Joe Fiorito

I’ve reviewed Quicker Than the Eye by Joe Fiorito, and included mentions of several other poets I admire and appreciate. The review is over at The Wood Lot, and my thanks to another talented poet, Chris Banks, for creating a home for poetry reviews and essays.

December 27, 2024

Year in Review: 2024

Story collections: Coexistence (Billy-Ray Belcourt) is the kind of collection I appreciate because it’s intensely interested in being meaningful and profound, with lines like “Remember: a man is a fable that doesn’t necessarily convey a moral.”

What We Think We Know (Aaron Schneider) is a skillfully written set of stories with the right amount of experimentation: it’s the spice, not the main course. Reviewed below.

Difficult People (Catriona Wright) has one of those titles so good you wonder why you haven’t seen it before. Characters that feel quite real are in unique slices of life, so to speak.

Survivors of the Hive (Jason Heroux) is reviewed below as a story collection with a thoroughly enjoyable sense of experimentation. I imagine Heroux grew up on The Twilight Zone, like I did.

Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? (Raymond Carver) has a bit of a fragmented approach, but I appreciate that Carver wants to capture something real rather than provide all the answers.

Novels: Black Dogs (Ian McEwan) is concise and skillfully done, changing up the narrative a few times but always finding its way to something profound: “A crowd is a slow, stupid creature, far less intelligent than any one of its members.”

Desperate Characters (Paula Fox) has struggling, fairly self-obsessed characters I didn’t love, but moments in the writing like this: “Leon is right. When I open my mouth, toads fall out. I’m sorry.”

DeNiro’s Game (Rawi Hage) is an urgent, compelling novel about childhood friends growing up in war-torn Lebanon. Remarkable details, and if I found it a little clunky in execution, I think maybe that just added to the realism, somehow.

Piranesi (Susanna Clarke) is an intriguing and skillfully written intellectual mystery, involving identity and assorted rooms large enough to have hundreds of statues and cloud formations.

Gormenghast (Peake) is the middle part of a trilogy of novels set in a fictional world that reads a bit like Shakespeare. No dragons, just people and their own motivations, and it’s nothing short of remarkable with great moments in the writing. But start with Titus Groan.

Anomia (Jade Wallace) is reviewed below as a compelling but meaningful novel that doesn’t include gender for any of the characters.

The Road (Cormac McCarthy) immediately became one of my favourite novels for being as gripping as it was profound, with just the right amount of scattered poetic moments.

Confessions of a Crap Artist (Philip K Dick) is a pretty straight-up drama without any twist on reality, proving Dick and simply conjure up fascinating characters in a compelling story featuring “a collector of crackpot ideas,” and his impact on the world.

Mystery novels: The West End Horror (Nicholas Meyer) is a thoroughly engaging Sherlock Holmes mystery involving the theatre world with characters like Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde appearing.

Sherlock Holmes and the Great War (Simon Guerrier) was a compelling mystery but also involved a good amount of interesting historical detail that wasn’t awkwardly forced into the story.

Nonfiction: Grief is for People (Sloane Crosley) is a concise, deeply articulate memoir: “And no one is obliged to learn something from loss. This is a horrible thing we do to the newly stricken, encouraging them to remember the good times when they’re still in the fetal position. Like feeding steak to a baby.” It’s among the books I’ve reviewed below.

Best Canadian Essays 2025 (Emily Urquhart, editor) is another excellent book in the series, with relevant and skillfully written selections. It’s good to see the series going strong.

News of the World: Stories and Essays (Paula Fox) is something I read, having enjoyed Desperate Characters. As a collection, it was a bit hit-and-miss for me, but with some deeply worthy moments

Lazy Bastardism (Carmine Starnino) is a book of poetry criticism that had me reaching for my highlighter often: “The real game of writing poetry remains the part that rests entirely on a lucky break: the creation of a singular, stand-alone word structure that satisfies emotionally and intellectually while signaling itself as an artifice. Have our poets been that lucky? Absolutely.”

Boldy Go, Reflections on a Life of Awe and Wonder (William Shatner) features Shatner telling some interesting tales but also finding reverence, which I appreciated.

Graphic novels: I read many, but I think the best one was Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness (Kristen Radtke) which manages to slowly and carefully get at something profound.

An honourable mention to Through a Life (Tom Haugomat) which fast-forwards through the decades of a life in a way that clarifies how fleeting life can be, and how valuable.

Poetry: Like a Trophy from the Sun (Jason Heroux), A Year of Last Things (Ondaatje), Talking to Strangers (Rhea Tregebov), Ways to Say We’re Not Alone (Simon Alderwick), National Animal (Derek Webster), Ghost Work (Robert Colman). I Can Hear You, Can You Hear Me? (Nolan Natasha).

And Little Poems (an Everyman anthology edited by Michael Hennessy) was an excellent collection.

October 26, 2024

What We Think We Know, Aaron Schneider

I often can’t help but feel experimentation should be the spice, not the main course. Aaron Schneider enhances his stories skillfully in What We Think We Know using fairly moderate amounts of experimentation. Sex (in “The Cara Triptych”) has footnotes, detailing the stray thoughts and emotions typically washed away in all the surrounding moments.

In “Tuesday: All Day” (which vividly brings the life a day in the life of a teacher) an ongoing series of statements the teacher declines to add are crossed out and a long, awkward conversation he’d been dreading with a plagiarizing student goes without actual dialogue, putting the emphasis on what are basically stage directions: “[SILENCE].” At the same time, some of his students are the “jellyfish of culture,” in that “They are incapable of self-directed motion, but pack a vicious sting.”

Another favourite of mine was “The Death and Possible Life of Daan de Wees” which illustrates the way we survive in fragments of memory with the bald, unadorned statements about a grandfather in bold followed by less certainty: “Did they pack their lives into a set of steamer trunks given to them by a relative or into a handful of mismatched, second-hand suitcases with battered corners and latches Daan wired shut to be safe?”

In “Weather Patterns,” the way people move together and apart (and make use of each other, it could cynically be said) is blended with weather and the landscape. Schneider can both pile on the detail and keep the pace moving briskly along, as in this moment a woman leaves her apartment during an ice storm: “She yawed wildly along the sidewalk. Her hands slid off ice-slicked cars, deformed parking meters, the handle of a door that had doubled in size. She didn’t even make it to the end of her block before she turned back.”

And while it’s often ignored, the reality of climate disaster makes an appearance here when storms saturate the grounds in the mountainous coastal states of Veracruz and Tabasco, Mexico. With the soil incapable of absorbing anything, “more than a meter of rain falls in a few days, causing flooding and landslides, and washing crocodiles into the streets of Villahermosa.”

Unfortunately, I’m quite confident this part of the story isn’t made up, and it’s entirely believable it barely made the news in Canada. A character “pauses to imagine a slope shifting. Vague. Brown. Too broad to be fully grasped. Breaking free. Its weight gathering into a terrible momentum.”

If skill with language is an important ingredient in a worthy writer, far-sightedness and an ability to filter out the less relevant is perhaps equally important. This is a book that’s a potent and careful examination of life at the moment, and it comes highly recommended.

September 26, 2024

Anomia, Jade Wallace

Euphoria is a town nestled next to the Unwood, woods in which “You’ll survive,” but “don’t stay still for too long.” As a novel, Anomia successfully blends reality with mythology, getting the balance just right even as gender is left to the assumption of the reader. Having given up on more than one work of Canadian fiction this year for heavy-handed generalizations, I found this refreshing. By the time this lottery of assumptions has settled and characters have formed — with readers perhaps considering why they may have made those assumptions — the result is a long and valuable experiment in seeing people as complicated. A fable related near the end touches on the idea that this particular fable is retold, “re-envisioning itself, never quite resolved.” People are perhaps the same.

I was tempted to object to some character description closer to the end of the book when a character named Blue, we’re told, has “hair as dark as crow feathers.” Shouldn’t the reader have been given this before? And then it hit me: black and blue. It’s possibly a hint at the history of the character, but regardless, a character morphs a little and resettles in an unconventional but intriguing way.

All of this is blended with dialogue that can feel quite real, and skillful use of description: “The Singing Frog, the sign announces, though the image is evidently a rendering of a green toad, its skin nodular and mossy, its body stocky and its nose broad.”

A novel needs an impressive beginning and Anomia has one, but returns to profound, arresting thoughts throughout. A particular chapter begins “If the human mind were a place, it would be a body of water, immeasurably deep, where fish, aquatic plants, and microorganisms multiply too quickly to be tracked. Many are consumed as soon as they are born, others persist for years. Of those who endure, some are bright and gaudy and splendid and show themselves off to the glittering sunlight. They are impossible to miss. Others – who can say what they look like – hide away in the remoteness of shadows, seen rarely if at all by other creatures.”

Novels with a somewhat mythological feel still require character motivation and Wallace is careful to provide it. Fir, a character searching for Blue, remembers meeting Blue as “one of life’s scarce glimpses of paradise, when what one wanted and what one had were exactly the same thing.”

Nitpicks? Not many. I think for the omniscient narrator to use the occasional word like “avoirdupois” lifts the reader out of the novel in favour of being aware of a writer reaching for elevated language. And leaving out gender only occasionally interferes with believability (I don’t know of any teenager who’ll refer to “my parent,” in an unspecific way). But all that is more easily shrugged off in the context of a novel that blends our world with a slightly mythological take on it. Adorably, it’s a world with video rental stores even as other more recent technologies are around, like current phones.

I don’t think any great work of literature can be said to have relied on sweeping generalizations, and writers sometimes don’t always seem to recognize there are both unfashionable ones and immensely fashionable ones. This is a novel that neatly sidesteps all that from the start, given it can be quietly assembled in different ways, all while enjoyably well-written and peppered with interesting ideas. The paradox of movie theatres is that they “let you be close to other people without ever speaking.”

If the job of literature is to nudge us into new perspectives and new ways of thinking without being heavy-handed about it (so that people, you know, actually listen) Anomia succeeds admirably.