C.M. Rosens's Blog

November 26, 2025

Author Spotlight: Adrianne Brooks

Adrianne is a paranormal/fantasy author of over 15 novels.

When she isn’t writing, she’s busy with her kids on their homestead in the south.

Author Links:

All links: linktr.ee/adriannebrooks

Threads: @adrianne_brooks

Instagram: @adrianne_brooks

X: @AdrianneXBrooks

TikTok: @a_brookswriting

Bluesky: @adriannebrooks.bsky.social

You’re the author of 15 paranormal/fantasy books (and counting!), but we’re here to spotlight 2 – Riding Nerdy and Age of Defiance. Firstly, can you tell us what draws you to paranormal and fantasy, and why this has become your preferred set of genres to write in?

I read pretty much all genres, but I’ve always been drawn to the fantastical. I wrote my first short story when I was six or seven about a little girl who lost her baby sister in a fairy ring and went in to go find her only for neither to ever be seen again. I never really looked back after that.

Tell us about Age of Defiance. Did your own cultural/religious background play into the worldbuilding of this post-apocalyptic fantasy with angels and demons, and if so, how? If not directly, can you tell us about the inspiration and research that went into it?

My religious and cultural backgrounds influenced the worldbuilding in the sense that when I first wrote Age of Defiance back in 2012 it was a documentation of my own split from Christianity.

I’ve always been interested in various religions and have dabbled in theology and creation myths for most of my life.

I took recurring themes from these stories and built something from the pieces left behind.

Can you share your favourite quote or describe (briefly!) your favourite scene from Age of Defiance, and tell us why that’s your favourite, where that came from in terms of inspiration, and how readers have reacted/how you’d ideally like readers to react to it?

My favorite scene is toward the end when Defiance is facing down a zombie horde. I’ve always wanted an excuse to write something like that and the scene is a culmination of a lot of emotion and heartbreak in addition to just being really compelling to read.

My favorite quote from this book would have to be when the Archangel Uriel is speaking to Defiance about her sin of worshiping the devil. He says,

“If Hell awaits you, Defiance Gray, I pray you find it here, on earth, with me. Where I might still protect you from it. Where it might pass you by so quickly that the eternity you are left with is one of nothing but bliss.”

Can you tell us more about your character creation process – are you a world-first or character-first author, or something different? Can you use your FMC Defiance as an example, and tell us how she came to be fully developed?

I’m a bit of both. Usually, when a character comes to life in my mind, they’re existing in a moment or scene within their world.

From there, it’s up to me to sort of work backward and figure out – How did they get there? What sort of world is this and how did it affect them? who are they? what motivates them? where are they going from here? and so on.

Defiance came to me when I was listening to Castle by Halsey for the first time. I saw a girl painting death on God and watching him crumble into ashes at her feet as she danced and the story just unfolded from there.

Did you find yourself using the same process for your novel Riding Nerdy, and which character from this book was the most fun to create/develop? Who gave you the most trouble?

Yes, I use the same process for all of my books. And it would have to be a secondary character named Ape. He’s an aging werewolf biker zaddy, and I’m low-key obsessed with him.

The character that gave me the most trouble would have to be Edward’s mother. There’s an aspect of her characterization that’s very difficult for me to delve into, but I know that if I can go there, it will be a turning point in the whole series.

How much research did you do for biker gangs/what media did you consume for getting the right feel for the book?

For the crime aspect I actually just spoke to my older brother, lol. He robbed some banks/armored trucks and was kind enough to beta read my crime scenes.

In addition, the editor I chose was a woman who was a member of a biker club and had some experience with drag racing. She was kind enough to give me some invaluable advice about the inner workings of a club as well as bike and car specs for my chase scenes.

Can you share your favourite quote or describe (briefly!) your favourite scene from Riding Nerdy, and tell us why that’s your favourite, where that came from in terms of inspiration, and how readers have reacted/how you’d ideally like readers to react to it?

There are so many fun scenes in this book. There’s a part where the MMC is in the middle of naked fight club and turns his jingle jangle into a helicopter rotor, and I’ve seen people cry laughing over it. It’s my favorite because it’s such a great example of how the book blends genres, and I love the visceral reaction it evokes in readers.

Which books from your back catalogue should readers who liked AoD try next and what should they try after RN, in terms of similar character dynamics, settings, gods and monsters/angels and demons, or shared themes?

Right now, these are my only two books out. I’m currently revising my backlog so that I can republish them. Hopefully, AoD will appeal to the readers of RN and vice versa, especially since both books technically take place in the same world and feature some of the same characters.

Like This? Try These:

Like This? Try These:

November 24, 2025

In Praise of Non-Anglocentric Frankensteins

First off, let’s get this out there: I don’t like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. I get it, but I don’t like it. Del Toro talks [positively] about the book’s “fidgetey energy”, like a teenager questioning “why” to so many things, from capitalism to the meaning of life, and I think that’s also what doesn’t work for me, in the same way I can’t get on with the frenetic energy of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (which is basically ADHD: The Novel).

That said, I have two versions of it that I really, genuinely enjoy, and this post will contain spoilers for both: one is Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein (2025), and the other is Çağan Irmak’s Yaratılan/Creature (2023).

This will be a long post. I apologise for nothing.

They are both completely different, and focus on very different aspects of the novel and the themes within it. Neither is completely faithful, but both do really interesting things with the source material.

“I am more attracted to making movies about people that are full of villainy, because ultimately it’s a more real way of seeing the world.” – Guillermo Del Toro (quote from the documentary Frankenstein: The Anatomy Lesson 2025)

I really love both adaptations for the very different things they say and are in conversation with. While Del Toro is making a film focused (among other things) on the nature of villainy and monstrosity, Irmak is making a mini-series about (among other things) the redemptive nature of community and its power to engender and shape Selfhood, and the corrupting effects of isolation upon the soul, body, mind, and spirit.

I love both those things, and I find them both really compelling ways to tell the same story.

[One is also telling it within the confines of 2.5 hours, and the other is an 8-part mini-series, so they also have completely different formats and storytelling frames.]

Check out the trailers to get a feel of them side by side!

Frankenstein (2025) – official trailerCreature (2023) – official trailerLet me share some things I really love, comparing and contrasting the two versions.

CONTENTS

Framed Narrative Device

Victor/Ziya Comparison

Victor/The Creature vs Ziya/Ihsan

The Women

The Lab Setting

Religious Themes

Isolation & Redemption

Del Toro’s Victor & the Creature and Irmak’s Ziya & Ihsan are very different characters. Del Toro wanted to focus on the dialogue between fathers and sons, the isolation of those broken relationships and perpetuating abusive cycles. This is a story of rejection of a child, someone created from death then forced into monstrosity and to discover himself against this perception, because of the maker’s arrogance and hubris. Irmak wanted to tell a story of pushing the boundaries of science for the benefit of his family and community, the pain of losing members of that family and community, and the resurrecting of a parental figure (also rejected in horror) rather than the creation of an unwanted son. The themes are the same, but as it set in Ottoman Turkey, it has a distinctly Islamic cultural flavour, and is more grounded in communal relationships.

Even the names are meaningful: Victor, of course, has the meaning of the noun; the one who is victorious. In the end, he is defeated by his own arrogance and hubris, and broken down by the very victory over death he strived for. A victor is a singular person, often; many can run a race, but only one can win. Victor is a lonely, singular character – out in front of the scientific community, too far ahead to be fully appreciated or endorsed, and also too far gone to hear the words of warning and caution from behind him. Yes, he can achieve what he wants – he can triumph – but at what cost to himself, and others drawn into his orbit?

Del Toro plays with these themes with his Latin interpretation of Victor, whose passion cannot be stifled by cries of obscenity and blasphemy, and who does not understand why people, including his own brother, are frightened of him. Del Toro, I think, plays with the singularity of the victor as an image innate within the name of his protagonist, and the singularity of the monstrum, something strange and singular that gives warning or instruction of evil and the unnatural.

He embraces the original vision of Shelley in having Victor as the real monster, and this is the path he forges for his audience through Victor’s arc, and the explicit acknowledgement of his monstrosity in the dialogue with other characters like William and Elizabeth. Victor is ‘full of villainy’, and Del Toro enjoys playing with this on screen, and leading up to Victor’s suffering and death as his only means of redemption.

Having the Creature constantly repeat Victor’s name is not only to emphasise the bond of father/son between them, but serves as a statement of fact: Victor is indeed the victor, he has won, he has conquered death, and now there are no more horizons for him to chase. The Creature repeats his name as a statement of fact, of not just who Victor is, but what he is, and Victor’s horror and irritability stems not just from the fact that this is all his creation can say, but serves as a constant reminder that, now he has won, he doesn’t like it.

The Creature does not name himself Adam in this adaptation, nor does he receive a name from anyone else; the only word he can initially say is “Victor”, his creator’s name, which he repeats in various emotional states, until Elizabeth teaches him to say “Elizabeth”, also. The soft way the Creature pronounces this name drives Victor into a jealous frenzy and increases his disgust. Yet the Creature at no point confesses or professes romantic love for her – in these early scenes, he repeats the names as a child might say ‘father’ and ‘mother’.

As Del Toro emphasises the Creature’s composite makeup throughout the film, and the question is asked, in which part lies the soul, the question of in which part lies the name is absent. The Creature is a being without a name, on purpose, because he has surpassed the singularity of his creator. It is also a way of showing the audience that names are not necessary – for Victor to name his creation would be an act of conquest, of colonisation, of ownership, but Victor does not do this because he does not want the responsibility that goes with it. He does not want to be associated with the ‘monster’ he has made, because it doesn’t live up to his expectations, his ideals, and he has to reckon with the fact that he is its maker regardless.

To name something also means giving it and others a means to understand itself, and Victor withholds this, perhaps as another form of control. Yet in this, the Creature demonstrates that profound and mutual human connection is possible without names; he never learns the name of the old blind man, and yet his speech takes on the old man’s accent and patterns. They share a connection that does not require names or labels; it simply is, and it is understood through action and mutual respect and understanding. Similarly, the audience is invited into empathetic communion with the Creature through the perspective shift, just as in Shelley’s novel, and they can connect with him through his story, without a need for a name. This absence does not even feel like an absence; it simply is, and ultimately, no name or label needs to be placed on the Creature by others or by himself in order to come to an understanding of his own nature, and his self acceptance. He is known, and that is enough.

In Irmak’s adaptation, names are also important.

Ziya is a unisex Turkish name that means ‘light’, which reflects the character’s desire for enlightenment, fulfils part of a prophecy about the resurrection ritual required to get the machine to work, and also creates a sense of contrast to his inner darkness and character development journey. This signals that the story is not about a victor, a winner, but about a man whose passionate pursuit of knowledge and scientific boundary pushing for the sake of his community as much as for himself, leads him to some dark places.

Ziya begins by confronting three major medical horrors: first, finding out his mother’s friend, whom he has known from childhood, has leprosy. His immediate instinct is to touch her, and he is frustrated by the stigma and ostracisation she is experiencing, and the lack of effective treatment for her condition. Secondly, the pain that Ayise feels at the death of her mother in a contagion, and the fact that he cannot bring her mother back, has a profound effect on him. Thirdly, the horror of a cholera epidemic which takes his mother, and during which he personally works with his father, Dr Muzaffer (with whom he has a loving, if occasionally fiery, relationship) to provide limited medical assistance to the town.

Ziya goes to train in Istanbul, only to find that the academy has narrow views, and does not want students to go beyond the limits of currently understood medicine, which Ziya argues is anti-Islamic. He is thrown out for challenging his tutor, but Ihsan blackmails the principle into letting Ziya resume his studies. It turns out that the professor’s reluctance to allow students to investigate anything stems from his own insecurities at having a forged diploma, rather from any actual religious conservatism, which he hides behind. Ziya sheds light on the academy, but also on Ihsan, whom he first encounters at night. Ihsan is presented at first as the shadow-side of Ziya, but as the series progresses, it is clear it is also the other way around. Ziya tricks Ihsan into working alongside him, and even drugs Ihsan to get to the bottom of his secret machine. When it all goes wrong, it is Ihsan who pays the price, and Ziya resurrects him out of guilt and desperation, but then tries to hide what he has done by burning down the lab. He doesn’t try to burn Ihsan with it, but instead dresses him up as a leprosy sufferer and abandons him on the roadside. But hidden things keep coming to light, whether Ziya wants them to or not, and the consequences of his actions pursue him relentlessly, no matter how he tries to escape them.

Ihsan has a whole wealth of meaning, from simply ‘kindness’, to the deeply Islamic principle of showing your faith in actions, beautifying, or to do beautiful things. Ihsan helps people on the margins of society, and has a conscience about using dead bodies in his experiments – he covers himself from shame, but Ziya is more brazen and less concerned with morality. Ihsan extends to using a dead boar (pigs are haram), and drinks alcohol to excess, but he has lines which Ziya encourages him to cross. The result is his own horrible death, and resurrection, whereafter he is constantly referred to as a ghoul. Even so, he shows kindness and compassion to people he comes across, and seeks to protect other powerless people whom society has rejected, like him. In this way, he still lives up to his name, and ironically more so after his unnatural rebirth than when he was alive.

Ihsan and Ziya’s perversion of the natural order and use of forbidden texts pervert their very names and natures, but the narrative allows for them to return to those meanings, and explore (especially for Ihsan), how one can still enact kind and beautifying deeds as part of his social responsibility, even when he has been rejected by society and does not know how he fits into it anymore.

After a while, he re-names himself Ihsan, once his memory patchily returns, but he no longer knows who Ihsan was, or what that name means to anyone who might have known him. He has to find a new way to be Ihsan, and find a way back into himself, as well as a new way to understand his current existence. This forms Ihsan’s character arc, one rooted in Turkish drama as much as it is in Shelley’s novel. The result is that every episode is a banger, but Irmak manages to avoid a lot of the usual Diziler cliches, while making Frankenstein fit into a Turkish mould to be enjoyed by audiences used to certain formulae and conventions.

The Framed Narrative: PrefaceDel Toro’s story begins in the Arctic, reset to 1857, but focused on a Danish expedition to the North Pole. There wasn’t really a Danish expedition at this time, there was a British one which aimed to find Franklin’s lost expedition, and the opening of Del Toro’s movie definitely gave me The Terror vibes. The framed narrative goes from here, and I really liked the opening being in Danish, rather than English, as that located it for me as a much less Anglocentric Frankenstein and set the tone.

Irmak’s story is prefaced with Captain Ömer’s narration, and he asks why are people so afraid of ghouls? It is because they are afraid the ghoul will start talking, and they will learn there is nothing after death. It is set on the snowy mountains in northwestern Turkey, and the city of Bursa which lies in the foothills. In the mountains is rumoured to be the treasure of a long-dead Byzantine prince, and so the mountains are frequented by treasure hunters who often lose limbs to frostbite. One such party, led by Captain Ömer, discovers an unconscious man in the snow, who seems to have been carried there by a mysterious figure. Thus sets off the framed narrative, initially shot as backstory.

Both these framed narratives have the same function as the book – the tale is told to men obsessed with their own horizons, their own chasing after legends and making something of themselves, and the tales serve as a warning against their overreaching, dangerous ambitions. Except, of course, Victor’s tale is told only to the Captain of the ship, but Ziya’s tale is told at first just to Captain Ömer, but then to the whole group, and is a warning not to one man, but a warning that benefits all the hearers of the same story. Even in this, we have the contrast of the singular and individual versus the community and society.

Victor & Ziya Victor saws into a limb – Frankenstein (2025)

Victor saws into a limb – Frankenstein (2025)Victor is scarred by his mother’s death as a young boy. She dies giving birth to William, his little brother, whose appearance favours their father, and makes him the favourite child. I can see the Latin American racial layers coming into play here, superimposed on the European aristocracy, and I really liked that dimension. I really enjoy the passionate Victor, much more than the cold, aloof, Germanic version who whines and complains a lot.

Ziya, on the other hand, is a grown man training under his father to be a doctor. He was deeply moved as a child by Asiye’s pain after she loses her mother, but his own loss comes when a cholera outbreak takes not only a large number of people in the village, but his own mother, too. Ziya is arrogant and hot-headed, but he has a close and loving (if tempestuous) relationship with his father. It is not the desire to supercede him that drives Ziya, but the determination to overcome death.

Victor & the Creature / Ziya & IhsanVictor’s relationship with the Creature is that of a bad father, procreating without woman, and not understanding either his creation, or how to have a relationship with him once he is made. This is the source of Victor’s horror and disgust – he has made something he doesn’t understand and cannot control, cannot unplug, cannot contain. Victor drinks milk, not alcohol, arrested at the point of his childhood and claiming an innocence he no longer has. He is searching for the secret to life to break the last barrier of science, for his own hubristic ideals, but he has no plans beyond this initial goal, which becomes all-consuming. When he does finally succeed, he immediately chains his creation to continue his control over it. He is encouraged in this endeavour by Harlander, a man riddled with syphilis, wanting to preserve his own mind in the new body of a new man.

Harlander reminded me strongly of both Basil and Henry in The Picture of Dorian Grey, and Del Toro himself described him as both antagonist and sympathetic. Yet he is not a corrupting influence – Victor is doing that all by himself. He also exceeds his own father’s cruelties, and the whole film is very much grounded in that central premise of broken father/son relationships.

Ihsan hooking up a body to the machine – already looking like a cross between the Igor characters of some versions, and the Creature himself.

Ihsan hooking up a body to the machine – already looking like a cross between the Igor characters of some versions, and the Creature himself.Ziya’s relationship with Ihsan is very different – from the first moment they meet in Istanbul, there is a sense of both attraction and repulsion. Ziya is afraid of Ihsan’s strange behaviour at the University, and then Ihsan begins leaving him notes to let him know that he saw him spying. He behaves the way Shelley’s Creature does to Victor at the end of the novel, mirroring this relationship, and foreshadowing what is to come.

The horror here comes from resurrecting Ihsan as a deformed, blank slate – no longer Ihsan as Victor knew him in life, but something else, a ghoul, that cannot communicate in the same ways. When the newly resurrected Ihsan says “baba?” at the marketplace, it reinforces the horror at that relationship being reversed, and now being unfamiliar and fundamentally broken. That is not something that the embittered, lonely cynic with a secret heart of gold would ever say.

Ihsan and Ziya are reflections of each other, mirrored images, dark and light, death and life.

Ihsan and Ziya are reflections of each other, mirrored images, dark and light, death and life.Ihsan in life is already Othered – a disgraced ex-faculty member of the medical school, a drunk with aural hallucinations, acting erratically. Ihsan is both Creature and Harlander, the instigator of Ziya’s resurrection discoveries, and the resurrected who pays the price for his own ambitions as much as for Ziya’s.

In fact, Ihsan is in the parental or mentoring role, specifically asked by Ziya’s father to keep an eye on him. They are, from the outset, mirrors of one another, presented explicitly throughout as two parts of one whole, two sides of the same coin, life and death, Self and Other, monster and man. This is not a story about bad fathers and damaged sons, it’s a story about all the facets of a person, and how community is essential in shaping them and guiding them back to a sense of themselves.

Ihsan is already a recluse conducting haram experiments, despite having a kind and caring heart, and persuading himself he is doing questionable things for the right reasons. The lady with leprosy, living in a colony of fellow sufferers, kills herself after learning of Ziya’s mother’s death from Ayise, and reportedly falling into a depression (off-screen). Ayise learns about the degrading and detrimental impact that being cut off from mainstream society with a stigmatised disease can have, while Ihsan’s ostracism has left him lonely, bitter, and falling into heresy. Ziya doesn’t see this – he leans into it, and cuts himself off from the world with Ihsan in order to pursue their dangerous goals.

The WomenThen there is Elizabeth and Asiye. Again, two very different characters, playing very different roles within the same story. Also bear in mind that Del Toro’s story is a deeply Gothic piece, while Irmak’s pays homage to the European Gothic elements of the story, but is more rooted in Turkish drama traditions.

I loved Mia Goth’s portrayals of both Elizabeth and Clara Frankenstein, I loved the costuming and the colours, the relationships she had with William, Victor, and the Creature. I also appreciated that she wasn’t murdered by the Creature, as she is in the novel, to hurt Victor. Elizabeth Lavenza is the adopted sister and wife of Victor in the novel, following the pseudo-incestuous Gothic trope, but she’s also a mother-figure for him, and that is brought out in Del Toro’s version as sister-in-law with spurned romantic tension, and the fact Mia Goth literally plays Victor’s mother, so the fact that both he and William are subconsciously drawn to Elizabeth adds another pseudo-incestuous dimension by visual associations. I really enjoyed all those layers.

Elizabeth and Victor bonding over the beauty in death – Frankenstein (2025)

Elizabeth and Victor bonding over the beauty in death – Frankenstein (2025)I love that Elizabeth turns Victor down to marry his brother in this version, and that Ayise’s rejection of Ziya prompts the start of his redemption, where he pledges to do better, and give up his obsessions, arrogance, and pretensions, and live a simpler life. At this moment, a plate smashes, an omen that a crisis has been averted. Victor has no such redemptive moment – he ends up shooting Elizabeth and blaming the Creature. His crisis is not averted, but his moment of forgiveness comes on his deathbed. Unlike Ziya, Del Toro’s Victor is not afforded a chance to redeem himself, but only given the opportunity to suffer on the ice as hunter becomes hunted, and creation masters the creator. Elizabeth is not his redemption or his conscience, she’s a character given her own personality and space on screen, and she’s really well played.

It is very deliberate that the only women in this adaptation are Victor’s mother and love interest, and they are played by the same actress. This really reinforces a lot of the character notes and themes of the film, and again, I loved Mia Goth in this so much.

The women in Irmak’s adaptation are many and varied. There is Ziya’s mother and his grandmother, both of whom are great characters, and the neighbour with leprosy, who plays a part in both Ziya’s arc and in Ayise’s. There are the women in the circus where Ihsan finds a temporary family and home. There is Esma and the old lady in the village where Ihsan flees after the circus, and there is Ayise herself, the main female character and Ziya’s bride-to-be.

I could talk about all of them in detail, but I’ll focus on two of them, to match the two female characters in Del Toro’s version. Rather than it being Ayise and Ziya’s mother Gülfem, I will talk about Ayise and Esma.

Ayise and Ziya after the death of Ziya’s mother

Ayise and Ziya after the death of Ziya’s motherAyise is raised with Ziya after her mother dies, and Ayise’s father declares that there is nothing for her in the village, where many others have also died. She and Ziya fall in love, and Ziya’s mother gives them her blessing on her deathbed. I don’t personally believe Del Toro’s Frankenstein should pass the Bechdel test, which is something I’ve seen Internet Discourse about (because it doesn’t), but this adaptation does – Ayise shows herself to be a good-hearted, independent, and community-spirited woman, who continues to comfort and visit a family friend with leprosy, just as Ziya’s mother did. Ayise is the peace-keeper in the home not by capitulating or being quiet, but by shouting at Ziya when he’s wrong and making him apologise to his father when that is warranted. She is not his mother, but his partner, with a life of her own while he is in Istanbul, and I really loved that for her. She has her own lessons to learn about love and suffering, her privilege, and her place in the community and the world, apart from Ziya.

Esma is Ihan’s love interest – it takes him until he resurrects to have one of those, so arguably he only really comes to know a family and experience love after his short sojurn in Hell. Esma is the equivalent of the young girl (Safie) who lives with her blind grandfather in the book, who isn’t given space in Del Toro’s version. In this one, Esma is pregnant – her fiancé raped her, then refused to accept the child was his, and she ran away. She is in hiding with an old lady who took her in, and now Ihsan is offered the life of a father with a wife and child, but this is snatched from him when the baby is born, and Esma is murdered in an honour killing. The baby is given up for adoption, and Ihsan is once more without a family, but he wants Ziya to resurrect Esma for him so she can be his companion and bride. He decides against this at the end, to not condemn her to the life he is living.

The LabIn Del Toro’s Frankenstein, the lab itself is an absolutely amazing set piece, with so many visual homages and great details. The colours are in dialogue with the costumes, the lighting works with everything, and it’s genuinely an amazing feat of set design. It’s very much a phallic feat of engineering, the kind of thing a certain type of man builds to compensate for the size of his estate… The storm is the catalyst, but so is the death of Harlander. There is a crucified Creature waiting rebirth, and there is beauty in the monstrous make-up. There is also the implication that the first thing the Creature must do is get himself off his cross (albeit one laid on the floor), and this is the opposite of Christ’s resurrection; even his birth is a blasphemy, and this is Victor’s fault, not his own.

Corpse parts are everywhere. When the Creature is born, Frankenstein’s first instinct is to chain him up and leave him below the lab in the tower, frustrated with the slowness of his intellectual progress. He threatens and abuses the Creature for being afraid, and for only being able to say “Victor”, the way an infant’s first word might be “Dada”.

The lab explodes with amazing pyrotechnics, and we see how Victor escapes first, then the Creature in the Creature’s point of view section of the film.

In Irmak’s version, the lab is within Ihsan’s house, a hidden secret, and this makes everything more contained and dramatic. It is in the woods outside Istanbul; lonely, unassuming, just like Ihsan himself. However – it is Ziya himself who gives life to Ihsan, not just via the machine and galvinism, but because he fulfils the prophetic conditions of the Book of Resurrection and understands it is his own blood, from his palms (on which, his grandmother told him, are engraved the 99 names of Allah), and he is willing to bleed and sacrifice himself to regain Ihsan. He initially took blood from an ethnic minority community in exchange for money, the same ones he defended against racism from a guard, but it is his own blood that is required.

There is no beauty in the horribly burned corpse of Ihsan – and when he rises, he is a blank slate, and bears no resemblance to the man Ziya loved. Ziya begs the resurrected Ihsan to speak to him, to give him some sign that Ihsan is still there, that he remembers who he was before he died. Ziya’s horror and rejection of Ihsan comes from his belief that Ihsan has come back wrong and empty. Ihsan is no longer a Professor, but needs to be toilet-trained and washed like a baby. His fear of fire leads him to nearly strangle Ziya, who chains him to his divan, horrified and not knowing what to do. Ziya recruits his friend Yunus to help him burn the lab down and get Ihsan out, planning to abandon him like an unwanted dog.

In both cases, there is a deep sense of fear and horror and profound disappointment in their creation, but for very different reasons. Frankenstein is appalled that he has begotten someone who cannot match his measure of intelligence, but also lacks the patience to teach him properly. He is horrified at the monster he has made, seeing only the unnaturalness of him, the imperfections; yet he intervenes in the market when Ihsan follows him there, and prevents the people from attacking Ihsan and hurting him. Ziya cannot do more than this, however – he runs away and abandons Ihsan again, and Ihsan stands there, confused and bereft, saying, “Baba?” (“Dad?” in Turkish). This is not the relationship that they ever had, and it’s not something Ihsan would ever say. In fact, he had a bad relationship with his own father, who rejected him, and now he is going through this abandonment again in his afterlife. Ihsan is about to be rejected and ostracised all over again, just as he was in life, but without the tools to deal with it, or the understanding of himself to cope.

Ziya is devastated at the loss of Ihan, but also wants to cover his tracks. He is afraid that Ihsan had been returned from Hell, and this was the reason for his fear of fire, his total amnesia, and his regression. He doesn’t want to be responsible, and so he abandons Ihsan on the road disguised as a leprosy sufferer, selfishly demands forgiveness, then runs away and leaves him there.

Religious ThemesI really like the religious questions and intertextual elements of (book) Frankenstein, and how this is echoed in Del Toro’s version with questions of the soul, forgiveness, and the final moment of embracing the sun – the moment that appears at the end of Cronos and Pinocchio, a favourite image for Del Toro that encapsulates his ethos. It’s the antithesis of Shelley’s ending, where the Creature walks out into the darkness, and yet it provides that ending, and imagines beyond it, to the sunrise of a new moment, a new beginning, a new man. Not only new, but accepted and seen, wholly and completely, and loved for who he is. This is contrasted with the monstrosity of Victor, condemned for playing God, and in whom a God who rejects and abandons His creations is held up as monstrous. Victor is criticised as being obscene and blasphemous – all of which he turns on his creation, who says, “To you I am obscene – to me, I am simply myself” (paraphrased).

In the book, of course, the ending is not as explicitly hopeful and optimistic, but in the book, the Creature murdered Elizabeth and has become “an instrument of evil”. Walton discovers the Creature mourning Victor. The Creature walks off into darkness to die, trying to reclaim his sense of self in the process. I prefer the adaptations that end on a note of hope, or those which really dive into the tragedy of the human existence and the central relationship.

In Irmak’s version, Ziya uses the teachings of the Prophet (pbuh) and the Qu’ran to justify pushing the boundaries of science, and is spurred to find cures for everything from his experiences in Bursa. His community’s cholera epidemic, seeing Ayise’s pain at her mother’s death, and seeing his mother’s friend with leprosy, all spur him onwards, but the crucial thing is finding a picture book in his father’s study disguised as “Stories for Children”, but actually relating the tale of the “Book of Resurrection”, a forbidden and lost tome. Ziya memorises the book even though his father punishes him for having taken a key and getting it out of its locked hiding place, and here we get some Necronomicon vibes/references, with alchemy. Ihsan, meanwhile, has been desperately seeking this book to push forwards with his own experiments (decidedly not halal, as his machine uses wild boar). Yet Ihsan tries to persuade Ziya and himself he only wants to use the machine to revive diseased and damaged organs, and cure bad diseases, not to raise the dead. It is Ziya who whole-heartedly sets out with the resurrection goal from the start, and shows Ihsan that he is lying to himself. This sets the experiments up as haram, and mirrors book Victor using animal bones and parts from the abbatoir in order to make his Creature, as well as human parts.

Neither Del Toro nor Irmak use the pick ‘n’ mix approach with their Creature, but I think this is Irmak’s reference to it, as well as using this to really underline the obscenities of the experiments for the audience. This is contrasted with Ziya’s enthusiasm – he doesn’t condemn Ihsan, but instead acts as a living version of the forbidden book, as the pictures and captions now exist in his head. It is fitting, then, that Ihsan’s accidental and tragic death makes him the prime subject for the machine, and turns him from Professor to Creature. The questions here centre also on the soul, but from the perspective of folklore and Islamic teaching; what is Ihsan now he is resurrected? Is he a ghoul? Do ghouls have souls? Can they be redeemed like living humans?

The machine in Irmak’s version is described as a sentient thing – mocking Ziya, looking at him. Ziya tells Cpt. Ömer that it was then he felt Shaitan beside him; this is the first time this pursuit has explicitly been aligned with the demonic, and it is by Ziya himself, who has now grown enough to recognise this.

Isolation & RedemptionWhat I love about Del Toro’s version is that every character is part of a self-contained Gothic world, where their very clothes are in dialogue with each other, with the sets, and with the story – but they are still all seeking some kind of human connection, with varying results. The Creature learns some very bleak lessons – everyone he cares for is taken from him, both the old blind man and Elizabeth, and his ‘father’ abandons him and rejects him. He learns self-acceptance at a terrible cost. This version of the Creature has no animal comforter, but kills wolves and comes to understand his place in the food chain and the dispassionate nature of the natural order: “The world will hunt you and kill you for who you are.” Yet, at the end of the film, he comes to an optimistic moment of embracing the sunrise, and stepping into the light. This is an important moment, but he does so on his own – this is a film about self-acceptance and self-discovery, about breaking generational cycles, and stepping into one’s own future, unshackled by the past. I like this, but for me, these types of stories lack the added dimensions of community.

What I love about Irmak’s version is that every single character has at least one friend, even if they are not part of wider society. They all have a hook to bring them back into community, if they can bring themselves to use it. Ihsan is so close to being restored to his living community when his only friend Hamdi lets him rest at his restaurant, but doesn’t recognise him, and Ihsan cannot communicate at that time, nor can he fully recall who Hamdi is. Ihsan’s living choices led him to reject society, and the family and care that Hamdi represents, and now after his rebirth, he is not able to reclaim what he rejected. Yet he is nevertheless provided with other companions and people who encourage him to find his own truth, his own sense of self, even as that is measured once more in loss and suffering. Even so, while human (and animal) connection is not necessarily sought after, it is given freely. People can be bad, but they can also be good; they can be cruel, but they can also be loving and generous. People are always simply people. Ihsan relearns all these lessons, and relearns his own compassion in the process, but at the cost of deep suffering. Yet, there is always the hope and the desire for community, for connection, for love, and that is what resonates with me so deeply about this whole piece. I love how Ziya deteriorates in the process of his flight, until he and Ihsan remain reflections of each other. I love how they get back together after a great struggle, and are only whole when they are reconciled. Only then are they free to go their own ways.

I think what sums up both adaptations is the idea that if you stop searching, stop seeking, stop striving, for something better than you have, there is no hope left. And the message of both versions is to ultimately embrace that hope, whether that comes from self-acceptance and understanding, or if it comes from religious redemption, or if comes from a return to community and a hope for closer connections. And whatever that is, that really resonates with me, too.

I think I’m going to leave this comparison alone for now, as this is already far too long, but if you have made it to the end, thank you for sticking with me.

I have so much more I could say – but perhaps another time.

In the meantime, I would highly recommend the two adaptations.

Like This? Try These:November 19, 2025

Author Spotlight: Kevin Schumaker

Born and raised in pocket communities across Wisconsin and Iowa, Kevin Schumaker (he/him) was the son of a hydraulic engineer and a secretary. Straddling the border between the boomer generation and Gen X, Kevin describes himself as coming of age between two, often incompatible, dreams for America.

Kevin has worked as a trial attorney for 28 years, and writes short stories and poetry. He is currently working on his first novel.

Author Links

Instagram: @kevin.schumaker.esq

Amazon Link: a.co/d/j2AJXWz

We’re here to talk about your poetry collection, That’ll Leave A Mark. Tell us about what first drew you to the existentialist and beat poetry traditions, and how this collection came to be.

I was a terrible student in high school and graduated in the bottom half of my class. When I finally did get to I flunked out after my second semester, passing only Intro to Philosophy and Fencing. I joke that my path was either going to be as a philosophy professor or a sword fighter. I originally chose the first. Eventually, I fell in love with the French existentialists, especially Sartre and Camus. To this day, I still reread Camus’s The Stranger every few years.

As far as the Beat poets, I think I was just drawn to the way they rejected traditional poetic forms and rhythms. Plus, they wrote about all the things polite society looked away from. That was what I wanted to write about as well. So, when I set out to collect my poetry into this book, I realized that these influences permeated everything I had been writing. So, I think the poetry came first, the labels came later.

Can you tell us more about how you see the world, perhaps how your philosophy background plays into this, and where your inspiration comes from?

I was never a popular kid. I would have one or two friends, but we were always the outsiders, the ones that didn’t fit in with all the cliques and groups in school, or in the workplace. I think when someone lives as an outsider there can be two big responses.

First, one can react in hate and become a person who’s focus is on what’s wrong with the world.

The second response, and the one I seemed to have taken, is not to hate that and those that pushed you away, but to fall in love with all the things that have also been pushed away.

That’s why I say my writing is about finding the beauty that exists in the things that others find ugly. I think my study of philosophy really aided me in this. To be a “philosopher” is not a popular thing, and really not respected as it once might have been. But, it taught me how to put what I see and feel into words. So, it trained me to write, and to write from a place outside of the norm.

Were there other poetical forms you played with that did not make it into the collection, or other poems that did not make the final cut – what were they, and why?

I am a very unintentional writer. By that I mean I write the poems that come to me when they come to me. I’ve tried, at various time, to sit down and write a poem about a subject or topic, but those never work. They always feel forced. Additionally, I can not write anything that rhymes. I respect those who do, and most of my poet friends embrace that form. To me, though, I always feel like I’m being to clever when I try to rhyme. It always feels like, “look what I did there.” So, all my attempts at rhyme are in the dustbin.

How did you structure your collection from beginning to end, and what can you tell us about your opening poem – why that one to open the collection?

Laugh, I have to recall how I opened the book. Well, there are two poems that open the book. There is One Love, which is the first official poem. I chose that one, and like that one as an opener, because it opens the book with a sudden, visceral, image. “Simply strike one love” is so kinetic, so bodily, sound. I think it opens the book with some drama.

There is another poem though, earlier. In the introduction I open the intro with the first have of a poem, and end the intro with the second half. I did that because I wanted to very bluntly let the reader know who I am as a writer. The opening line, “I have no interest in beauty” I think places me where I see myself. I write from outside the circle of most poets.

If you had to choose a poem to highlight (apart from the opening one) which you think – or readers/critics think – encapsulates a lot of your themes, which one would you pick, and why?

Kisses (Three Different Ones) has been my most popular when performing. It’s structured in three parts, like a triptych, three different panels displaying kisses in three different moods. I like the moods and swings of it. And, I think structurally it’s one of my most significant. On the One Year Anniversary of My Father’s Passing – 09/06/24 is special for me. I wrote it while planning his funeral, while it was going on, and I think is a very pure unfiltered portrayal of that moment.

What has been your favourite responses to your work so far?

I’ve gotten some really nice reviews of my book, which of course I love. But I think my favorite response so far has been my own.

Completing this book, and getting it published, has caused me to change the way I view myself. I have always been a lover of artists. Writers, painters, poets, dancers, all of them.

Once I saw this book in print I realized, I may not be the greatest of these people, but I am one of them now. I guess, in the end, by publishing this book I finally feel like I’m part of the crowd that I love most. The misfit artists.

Like This? Try These:

DAJ2020 – award-winning author of Emotions, a poetry collection. Read his interview here.

V. Walker, poet and author of the collection The Fragile Humans We Are. Read her interview here.

Read More:

Read More:

November 12, 2025

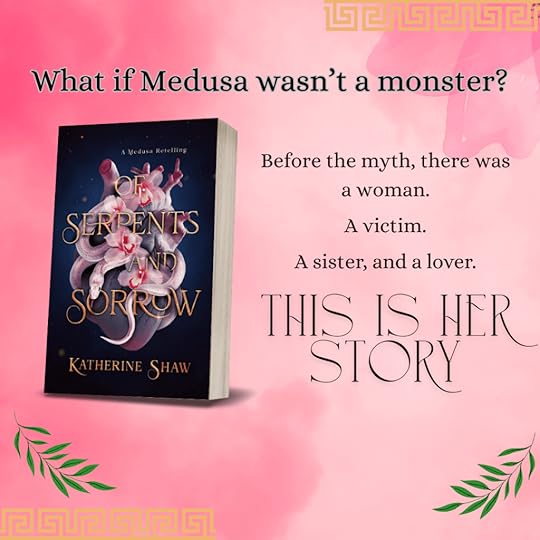

Author Spotlight: Katherine Shaw

Katherine Shaw (she/her) is a multi-genre writer, bi and grey ace disaster, and self-confessed nerd, hailing from Yorkshire in the UK. She spends most of her time dreaming up new characters or playing D&D, and you can find more about her and her latest work at her website (katherineshawwrites.com).

Author Links:

Instagram, Threads and Facebook: @katherineshawwrites

Bluesky: @katheroony.bsky.social

Website: katherineshawwrites.com

Your Historical Fantasy / Romantic Tragedy sapphic Medusa retelling, Of Serpents and Sorrow, came out in August (2025). Can you tell us about the premise, and where that premise came from?

I’ve been a Greek Mythology geek ever since I was a child, so I’ve always had an urge to delve into retellings at some point. I’ve been re-reading some of my favourite stories in recent years, and growing a little frustrated by how we’re only told the point of view of the “hero”, and learn virtually nothing about characters around them, including the “monster” they often have to slay.

Perseus’ goal is to slay Medusa and take her head, but who was Medusa before this moment? What life had she led, and what did she mean to those around her? This is what I wanted to explore with Of Serpents and Sorrow. I wanted to give Medusa the backstory she deserves.

There are many different variations of the Medusa myth – which did you read/know about, and how did you go about developing them into a retelling?

I’m fairly well-versed in the mythology of Medusa, but I did delve a little deeper than I had done before to make sure I was aware of the various versions throughout history (though it’s likely many more have been lost to time). There are two main myths to be aware of: the older one told by Hesiod where Medusa is always a gorgon as the offspring of Phorcys and Ceto, alongside her sisters Euryale and Stheno (who are also in my story), and the later one told by Ovid where she begins life as a woman and is transformed following an assault by Poseidon.

The latter is probably the most famous nowadays, and many SA survivors use iconography of Medusa for this reason. I focused my retelling on this version, as it provides the opportunity to give Medusa a human life before she becomes the gorgon most people know her as, and allowed me to show her as a real, living, breathing person before she is killed.

Can you tell us more about Ismene and how you developed her character?

I love Ismene, and it’s been fascinating (and wonderful) to see how many readers connect to her. I knew going into the book that I wanted the story to be sapphic, and so when creating Ismene I went in with the idea of developing a potential partner for Medusa, whilst also providing her own identity, backstory and room for character development.

A lot of Ismene’s struggles came from my own research into what life was like for women in Ancient Greece (spoiler: it wasn’t great!). While Medusa was a priestess, and so would have some privileges other women would not have access to, Ismene wouldn’t have any of that, and would be under the control of her father until she was married off. This fact really planted the seed of who Ismene was going to be, and what the conflict would be in her life outside of her relationship with Medusa.

Can you tell us more about the setting, and the research and worldbuilding you did to create the historical fantasy feel?

I always wanted to keep the Ancient Greek setting, and so I went into the writing process wanting to make my descriptions as accurate as possible. What I soon realised is how most of the information we get about historical cultures is through the lens of the aristocracy, and finding out about the day-to-day lives of average people is actually really tough. It’s easy to find out about kings and temples and palaces, but when you want to know what a typical person might have in their house, what they might have eaten, what furniture they had… that takes some digging! I enjoyed it, though, especially when I visited a museum in Corfu and got to see some of those sorts of items myself.

While everyone else was looking at the statues and artwork, I was peering into the glass cases of bowls and tools and equipment, taking photos and soaking it all in. Ismene’s time on the island of Crete was a little easier, as I’ve spent time there myself and could draw on my own experiences, especially when describing the city of Knossos, and the surrounding fields of herbs and flowers (I’ve never forgotten the amazing smell).

While I’m sure there are some accidental mistakes in there, I did my very best, and the feedback I’ve had from readers so far has been really great, which is a relief!

What are the key themes of Of Serpents and Sorrow and what would you like readers to be aware of before they go in (any CWs etc)?

One the taglines I use for the book is “who is the real monster?”, and I think that summarises one of the core themes quite well. We look at monstrous characters and assume they must be evil, must be the villain of the story, but appearances aren’t everything. Beyond this, there are some obvious feminist themes, given both Ismene and Medusa’s battles against their positions within a highly patriarchal society, but with this comes a strong feeling of women being their most powerful when they come together.

As in most of my writing, there is the theme of found family, and that the strongest sense of love and belonging can come from unexpected places. Even with Perseus, he is not just a two-dimensional hero blindly fulfilling a quest, but he has his own struggles and insecurities due to the class structure of his homeland, and his desire to prove himself to his superiors is what drives him forward.

This is definitely an emotional book, and I always make sure to describe it as a tragedy so readers go in with their eyes wide open. While there is a beautiful love story at the core of the book, there are also some deeply upsetting moments, so be prepared for an emotional rollercoaster with this one.

There is a full list of content warnings on Storygraph for readers to check they are comfortable with the content before they continue.

Which books from your back catalogue do you think would help your readers’ book hangover once they’ve finished this one?

If you’re left wanting more sapphic romance, my short story “The Knucker of Lyminster” appears in the anthology Once Upon a Summer (alongside other summer-themed fairy- and folk tales). Similarly, if you’re still hungry for Greek mythology retellings, my fae Narcissus retelling (where Narcissus is NOT the villain) appears in Once Upon a Spring. If you want a novel but don’t mind a jump into another genre, my domestic thriller Gloria also has themes of found family, female friendship, and rage against an oppressive, abusive man.

Like This? Try These:

Romantic tragedy Shattered Fate by M.T. Envy – Greek myth retelling with queer rep.

Read the Author Spotlight interview.

Read More:November 10, 2025

The Castle of Otranto: Retelling When

With all the hype (justified) around Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein, I’ve just finished listening to The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole (1764), recording/narration by Thomas A. Copeland, the novel that spawned the Gothic by dropping a giant helmet on a sickly bridegroom and killing him stone-dead on the day of his wedding. (Click the title above for the Project Gutenberg eBook).

If you’re curious about ‘the first Gothic novel’, here are some fun starters for you to check out:

ArticlesThe Castle of Otranto, Wikipedia

The Castle of Otranto: The creepy tale that launched Gothic fiction, BBC Magazine, 2014

The Castle of Otranto, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Backlash: Romantic Reactions to The Castle of Otranto and England’s Gothic Craze, Andrew Reszitnyk, 2012

Classics: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, The Gothic Library, 2018

Review: The Castle of Otranto, The Grub Street Lodger, 2022

The Gothic has always been queer and transgressive, even from its inception (where incestuous/inappropriate m/f relationships are a possible stand-in for repressed homosexual desires), but this particular novel has not had the same kind of adaptation treatment as its more famous successors. That is, frankly, because it’s bananas.

There is one adaptation:

Otrantský zámek / The Castle of Otranto dir. Jan Švankmajer (1977) – an 18min animated Czech short based on Walpole’s novel. Švankmajer’s pseudo-documentary follows an amateur archaeologist and his exploration of the setting of Otranto Castle, which he believes is in Czechoslovakia, not Italy. (Watch on DailyMotion, also available on BFI Player). Book PlotLet’s break this down. Spoilers ahoy.

Here’s a handy Character List.

The whole thing is that the giant ghost of Alphonso is haunting the castle to fulfil a prophecy, that the Castle of Otranto will pass from the present family when the real owner (Alphonso’s ghost) grows too large to inhabit it. He takes the form of a gigantic, armoured knight, but the characters only see bits of him at any one time until the big climax.

The first glimpse we get of this is his helmet, crashing down from the sky without an explanation or any warning, and landing on the only heir to the castle (Conrad), as he crosses the courtyard on the way to his own wedding.

Later, servants are terrified at the sight of a giant leg in the gallery, and an arm somewhere else.

A group of mysterious knights rock up with a giant sabre they found in Joppa while on the Crusades, guided to it by a hermit who shows up later as a skeleton, and reunite the sabre with the helmet and Alphonso’s gigantic armoured ghost then puts in a brief appearance.

The plot, such as there is, revolves around the prophecy and the doomed family: Manfred is the current Prince of Otranto, and he’s a dickhead. He has one son, Conrad, who gets squashed like a bug in Chapter One, and a daughter Matilda who is the clever one he totally ignores. His pious wife Hippolita exists to pray and serve his whims, even when that extends to annulling their marriage on dubious grounds.

Matilda has a maid called Bianca, who is the sassy but loyal one who enjoys gossip and drama.

Conrad‘s bride is Isabella, Manfred’s ward, whose father, Frederic, is believed dead while on Crusade.

Well, Conrad’s squished, so Manfred has an absolute meltdown, as there goes his only son and heir. If Matilda marries, then Otranto will pass from his family line to her husband’s, and he can’t be having that for Ego Reasons. So he does the only sane thing a man can do in that position: proposes to Isabella, who is his daughter’s age, and tries to annul his own marriage so he can marry her legally and get some more sons.

Also, he wants to know what the hell just happened, and in the confusion he arrests a (suspiciously well-spoken) peasant, Theodore, whom he mistakenly believes is somehow responsible for the helmet catastrophe. He imprisons Theodore under the helmet. It doesn’t help that Theodore strongly resembles Alphonso, the ancestral owner of the castle… Hmmm I wonder what that secret could be that we’re probably going to find out later…

Isabella, horrified by her father-in-law’s proposal, runs away. The ghost of Manfred’s grandad comes out of a painting and scares a few people witless. Theodore manages to escape the helmet and meets Isabella, and helps her to escape. He then decides not to impugn her honour by escaping too, in case people think she has escaped with him, and so he … goes back under the helmet.

There is some shenanigans where Matilda fancies him too, and a bit of a love triangle but where each lady tries to out-pious the other by sacrificing her happiness for the other’s happiness, and tries to yield their claims to him. It turns out he’s into Matilda.

More shenanigans ensue with the action happening off stage, like a Greek drama, with Manfred being alerted to a giant ghost by servants rushing in and not being able to give him accurate information, very much in a comedy of miscommunication sketch style. (These scenes would work really well on stage).

Anyway, Isabella goes and hides out in a monastery with Fr. Jerome. Jerome is actually Theodore’s dad, in his Before the Monastery days, and they are both (surprise!) nobility. Theodore actually has a claim to Otranto. That’s why he talks like a nobleman and looks exactly like the late Alphonso. He is the rightful heir! What a surprising twist.

Theodore escapes Manfred’s wrath and again finds Isabella hiding out in tunnels and trying to escape Manfred.

Meanwhile, visitors to the castle have brought a giant sabre to the door, and their leader is a mysterious knight (about Manfred’s age). The sabre was shown to them by a wise old holy hermit near Joppa, and they’ve brought it to Otranto for Prophecy Reasons.

The mystery leader goes in search of the missing Isabella and finds Theodore protecting her. Theodore thinks the Mystery Man has been sent by Manfred and they duel. Theodore wounds Mystery Man, and it turns out… he’s just stabbed Isabella’s missing dad, Frederic. Oops.

Fortunately, it’s not fatal, there’s a touching reunion, and Isabella accompanies her wounded father and Theodore back to Otranto. Manfred again tries to execute Theodore even though it’s obvious by now he has nothing to do with the whole ghost giant thing, and Fr. Jerome confesses that Theodore is his son. There’s more shenanigans, and Manfred eventually relents.

Manfred now proposes to Frederic that if Frederic will let Manfred marry Isabella, Frederic can marry Matilda.

Matilda, who is in love with Theodore, who has spent all his time “saving” Isabella (badly), is not pleased at the thought of marrying Isabella’s dad.

Hippolita piously prepares for divorce and is no use whatsoever.

Frederic gets a visit from the holy old hermit who showed him where the giant sabre was, but the old monk is now a skeleton who terrifies him, and warns him against marrying Matilda.

Matilda goes to be with Theodore, but Manfred is insanely jealous and believes Theodore and Isabella are an item. He catches them together, believes it’s Isabella, and runs her through in a rage. It turns out he’s just killed his own daughter.

Matilda dies peacefully and piously, with much forgiveness and weeping all around.

At some point – GIANT GHOST appears.

Theodore marries Isabella instead, but basically vows to spend the rest of his life mourning for his lost love, Matilda. He ends up with the castle, and everyone lives miserably ever after.

Feature Film AdaptationIf you’re thinking, that would be a cool plot without the weird supernatural fever dream nonsense, you could read Clara Reeve’s retelling/adaptation/loosely based novel, The Old English Baron (1778), edited by Mrs Bridgen (daughter of the author and painter, Samuel Richardson). This novel was another major player in the development of Gothic fiction, and can be read online.

However, I would personally love to see something wilder and more contemporary.

Hear me out:

Modern-day religious cult family terrified of a ghostly giant prophecy. They’re very rich so we’re sticking with the names as not out of place. I’m leaning to super-rich US Americans, actually, as there’s that very culturally specific brand of US entitlement to European spaces when they can claim a bit of heritage in that place, without much understanding of what that actually means, or any grasp of the cultural norms and laws and so on. (No, not all US Americans… but definitely some of them).

The setting is a castle that Manfred has bought which has a caveat that it’s only his if he has got signed permission from the true heir, but the heir cannot be found. Manfred has been Doing Genealogy and believes this is his birthright, although prior to this he’s never been out of his state before. He has become rabid and weird about this, and has made it his whole identity and personality. He’s now hosting his son’s wedding there.

I think what would be a really fun device here is that, just like the novel claimed to be a ‘found manuscript’, this is ‘found footage’, but you get a mix of ‘footage’ (what is real and filmed), and character POV film, so you can see what they are seeing/think they see.

People find the footage in real time but it cuts out at inopportune moments or gets obscured, so it’s easy to get the wrong end of the stick from watching/listening to things back, and that propels the miscommunication and assumptions.

Manfred is the patriarch, but slimy and Mr Collins-like (thanks for that visual, Sam Hirst).

Hippolita is the perfect trad wife, but has no personality of her own outside of Bible Study and baking.

Matilda is the dutiful daughter who runs Hippolita’s trad wife social media.

Bianca is the sassy influencer hired for the wedding, who ends up feeling sorry for Matilda even as she sucks up to her for exposure and collabs.

Isabella was taken in by the family after her dad went missing on a mission trip. She’s being married off to Conrad, the weedy son, and is pretty miserable about it.

At this point, I reckon that the whole wedding party is spiked with hallucinogens or exposed to something in the ‘fairytale castle’ where the wedding is due to take place.

Time warps – the whole novel only takes a few days, a lot of Plot is tightly packed into a short space of time, so I think all the supernatural stuff could be explained either a bad trip, or as something they’re actually opening themselves to seeing.

Conrad could have been crushed by falling masonry (the castle is unsafe). But because of the prophecy, everyone sees it as a helmet – the power of mass suggestion, or actually a giant helmet?

We aren’t sure, because we see Groom Cam footage of Conrad (everyone’s wearing a camera for the wedding video compilation) getting crushed to death, but we’re not sure what by. Then someone screams that it’s a giant helmet, and all hell breaks loose.

You can then have reels and TikToks from Matilda and Bianca, with the scripted Lives vs the reality off-screen contrasted as things get increasingly weirder and weirder. As most of the action happens off screen in the book, you can have that happening here too, as people start tripping out and getting increasingly erratic and unreliable. The Guest Cam/Bride Cam/Social Media footage is only marginally helpful, as it doesn’t fully reveal things, only provide more questions and muddy the already muddied waters.

The group of armed knights who come with the giant sabre could be a gang who steal and smuggle antiquities out of different countries, perhaps the way the religious group/cult is funded, with Frederic as the mystery leader. He’s looking for his daughter Isabella, of course.

(I also think this works with the whole grooming theme, and older men marrying much younger wives, and the idea of Isabella’s dad agreeing to her marriage to Manfred as long as he gets to have Matilda.)

The sabre itself is an antiquity belonging to the castle, and is indeed brought back by Isabella’s missing father, but as they come under the strange influence of whatever it is going on there, they also start buying into the hysteria of ghosts and giants, and start seeing the sabre as enormous, and their stories of how they found it get as warped as the rest of the narrative.

Theodore is a local lad that Manfred wants to get rid of, because it’s fairly obvious he is the true heir. It does turn out he’s the son of the local priest, Jerome, who is there by law or something, to be present at the wedding.

(A little twist might be that Jerome is responsible for the hallucinations, to ruin the wedding and try to stall it so that Theodore can take his place as the rightful heir, but he didn’t realise how out of control things would get as a result. In the book, he obfuscates and tries to conceal things from Manfred, and this also has unintended negative consequences, so I think that fits. It would mean that he had a grand plan in advance, and it all falls to bits).

Bianca is the only one with any sense, and it’s not clear (either from her footage or her ‘off camera’ scenes) whether she is under the influence of anything, or if she’s worked out what’s happening and is stirring the paranormal paranoia.

However… obviously this goes very wrong, and ends up with a jealous Manfred stabbing his own daughter in a case of mistaken identity, and Matilda’s death.

I think this could work, and be really weird and messed up, as well as quite funny in places.

I want Samara Weaving and Mia Goth in this.Directed by Ben Wheatley [A Field in England (2013), Meg 2: The Trench (2023)] because that man has range.

OR

Directed by Angela Bassett (I loved her series of American Horror Story which has a very similar device of found footage vs viewing outside that device).

OR

Directed by an indie Italian director who maybe wants to say something about the selling off of Italian land and homes to foreigners, and have the whole film be about the underlying issues with that (focused around Theodore’s rightful inheritance).

I don’t know!

Anyway, that’s my adaptation idea… someone who knows how to do screenwriting should get on that, I reckon.

November 5, 2025

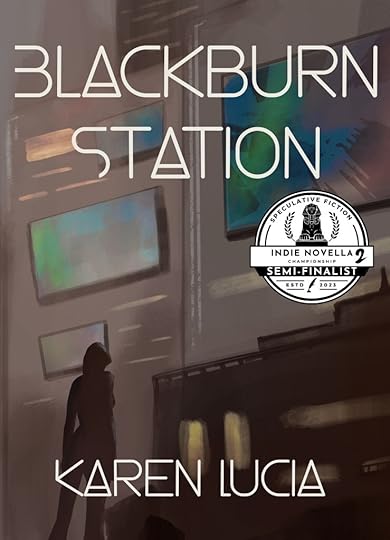

Author Spotlight: Karen Lucia

Karen Lucia (she/her) is a Minneapolis author. The long Minnesota winters taught her the value of a good story. Growing up on authors like Piers Anthony and Ursula K LeGuin she developed an interest in Science Fiction and Fantasy that has shaped her writing today. Throughout her life, Karen has had a small handful of adventures that help her craft the stories she writes, ranging from her time abroad, to becoming a mother, or her years spent as an Army Officer, working on a mass casualty response force, and her time in cybersecurity. Always on the hunt for strong female leads, Karen decided to write some of her own leading to the Warriors of Helsvern series. THE GOLDEN VALIA is her debut novel and the first book in the Warriors of Helsvern.

Author Links:

Website: KarenLuciaWrites.com

TikTok: @KarenLuciaWrites

Instagram: @karenlcreates

BlueSky: @karenlucia.bsky.social

We’re here to spotlight your gaslamp fantasy, Landbringer, and your Sci-Fi novella, Blackburn Station. Tell us what it’s like to hop from one genre to another – does your writing process change between the two, do you find yourself worldbuilding differently, was one more challenging than the other, etc?

When I write sci-fi it is generally soft sci-fi, so I don’t have to dive too deep into the science of it all. That helps smooth the jump between genres. I don’t think I my process changes (if you can classify how I write as having a process), but I do find sci-fi more challenging. I’ve always read sci-fi, but I have also been intimidated by writing it. I’ve read a lot of hard sci-fi, so I got hung up on the idea that the science needs to be explained and seem somehow feasible. But I have learned to let go. My writing is more character focused, and my sci-fi works so far have been novella length, so while the worldbuilding is there it doesn’t require the nitty-gritty details I am used to reading. I would say my process changes more based on the length of the work, and how much depth and development is needed, than based on the genre. I love genre jumping because it gives me room to try new things.

Tell us about your process for character development – how do you create your characters, and is it the same process for each project?

My process at the start of every story could generally be classified as chaos. When I am finding my character, I usually have a scene that I want to write and the unknown person moving through it. So, I will usually write the scene, see if I have a drive to write on from there, then see where the story is being pulled and how the characters feel in the space before putting more structure to the development. In a lot of ways, I let the characters and the story find themselves in the early phases of my messy drafting, then I think more critically about the characters and how they are interacting once there is more structure to the world around them. Landbringer came about because I was bored at work one day and decided to write a few pages focused on hands and that morphed into a character and a world and a novel.

Tell us about Landbringer and the world you built for this book. What drew you to gaslamp fantasy particularly for this story, and how does gaslamp fantasy lend itself to the world of intrigue, gods, and ghosts, that you created?

I actually had no idea Gaslamp was a thing until a few months after publishing Landbringer. I saw the word in a reel or something one day and looked it up and realized it fit what I had created. What drew me to it, though, was that I liked the steampunk aesthetic, but I wanted more magic and spooky ghosts in my story. The society structure of the era/locale of Gaslamp lends itself really nicely to quiet plotting and conspiracy with a twist of magic and behind the curtains workings.

Tell us more about your Sci-Fi novella, Blackburn Station. How did you worldbuild for this, and what were your influences?

Okay, so Blackburn Station came out of a weird place. I was attending a Suicide Intervention course and while I was there, little scenes and snippets of this story started taking shape. In terms of my influences for sci-fi, I am heavily influenced by Mass Effect. I love that game. Also, The Expanse. If you read it, I’m curious if you catch any of those vibes.

Grief seems to be a central theme of both books, with the ghost in Landbringer needing justice, and Jane’s grief as driving force in Blackburn Station. What draws you to write this, and what other themes do your works tend to share?

That’s a great question. I hadn’t ever really called that out for myself, but grief is definitely there. I feel like most authors would agree that writing is a means of processing and coping. As I have sort of collected more of these moments of strong emotion in my life, I think they tend to bleed out onto the page. My latest novella, A Second Life Worth Living, is very driven by a darker dread fueled by the current situation in our world. Funeral Singer is all about finding purpose and moving forward in your life. I think my novels are my place to explore a new world and really dive into characters and intrigue, while my novellas are where I process myself more.

What future works can we look out for from you?

I’m working on an epic fantasy now. I want something sprawling and massive and full of magic. I’ve been circling it for a while, and throughout writing it, I have sidestepped to write a few novellas, so I wouldn’t be surprised if a few other surprise stories come out before I have my epic fully drafted…

Like This? Try These!October 31, 2025

#AScareADay – Day 31 – The Path She Sings by Vanessa Fogg

October 31st – Vanessa Fogg – ‘The Path She Sings’ (2025)- Read it here.

The whole challenge list: romancingthegothic.com/2025/09/21/the-scare-a-day-challenge-october-2025

This one was heart-rending, too, and very much like Kaaron Warren – ‘Eleanor Atkins is Dead and Her House is Boarded Up’ for Day 25.

I really enjoyed this one. The imagery is beautiful, and so sad. The loss and emptiness and stepping into another state of being you cannot comprehend from living outside it – all depicted really movingly within such a short space.

I’ve got so many authors I want to read more from now, and adding Vanessa Fogg to my list!

Today is the release day for OCCUPYING BODIES, the body horror anthology my sad revenant story is in! Here’s another snippet from that, and where to get the anthology.

The premise here is a revenant whose last imprinted memory is of the long-distance partner they never got to meet in real life, after starting a relationship online. The revenant is now dragging themself along train tracks in a desert, on their way to where their partner used to live.

Get it now

Get it nowYou can escape your past, your fears, even your mind—but never the body you occupy.

The body is the first prison, the final battlefield, and the one thing we can never abandon. Yet what happens when the flesh betrays us, when consciousness claws against its cage, when skin, bone, and blood twist into something unrecognisable?

Occupying Bodies is a visceral anthology of body horror that explores the dread of living inside fragile, treacherous vessels. Within these pages, nightmares take the form of grotesque mutations, psychological unravelings, everyday afflictions magnified into terrors, and Cronenbergian transformations that defy imagination. Each story forces us to confront the inevitability of flesh—the aches, the ruptures, the decay—and asks whether escape is salvation or damnation.

Curated by Bernardo Villela, this collection gathers diverse voices united by one chilling truth: no monster is more intimate, more inescapable, than the body you inhabit.

Read on for a quote from my story:

There is something inside my brain. It keeps me company as I move forwards, under the blanket of heat and light pressing down on my broken back. It doesn’t hurt. I can feel it moving inside my skull, tickling parts of me into spasm and sparking my emotions into life, like light hammers tapping on taut strings.

I wonder if that is why the morning looks different today.

There is something inside my throat. I am not sure if I want it there, and it stops me forming sounds the way I want to. I could barely say anything the first time we called, do you remember? We had gone beyond small talk and only the abyss was left, and I was afraid of the depths you wanted to plumb. I choked up words that I hadn’t told another soul, the way I choked up clots when it all went wrong. Now, I’m afraid I have no more words for you, but you have the ones I wrote down, and the song I wrote for you. And I am still choking, but I hope you’ll forgive me. I didn’t mean to leave it so long to see you, but I am coming now.

I am coming.

October 30, 2025

#AScareADay – Day 30 – Bleeding Hearts by Suzan Palumbo

October 30th – Suzan Palumbo – ‘Bleeding Hearts’ (2024) – Read it here. Catch up with the Challenge list here.

I loved this one. This is witchy and not scary, but very appropriate for the spooky season nonetheless. I love Palumbo’s stories, the way she mixes in so many layers to her short fiction, and weaves very human dramas in so few words. I really love the idea of grief diffusing into something that grows, and a garden of other people’s pain.

I also really liked the ex-girlfriend’s misery (screw you, Rebecca) and how things develop between Ashley and Claire.

I really loved the garden imagery, and the idea of plants growing from seeds of blood and tears, and diffusing heartbreak and grief, rather than ‘curing’ it. I also love that you can then do anything you like to the plant – let it grow, take it home, or destroy it, up to you. It’s your pain.

I did an interview with Suzan Palumbo when her short story collection Skin Thief came out, and you can listen to that, or read the transcript, and grab her books now: