Laurie Dennis's Blog

October 21, 2025

Happy 697th to the Ming Founder!

October 21, 2025, marks the 697th birthday of Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of China’s Ming Dynasty. He was born (on what corresponds to Oct. 21 on our modern calendar) in 1328, founded the Ming Dynasty in 1368, and died in 1398. Those lucky eights seem auspicious except that they are based on the Western Gregorian calendar and would have meant nothing to Zhu Yuanzhang himself. In the context of his era, he was born in an Earth Dragon year on the 18th day of the 9th month of the 1st year of the Tianli 天曆 reign of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty’s Wenzong 元文宗 Emperor Tugh Temur.

However you cite it, we are a mere three years from the big 700!

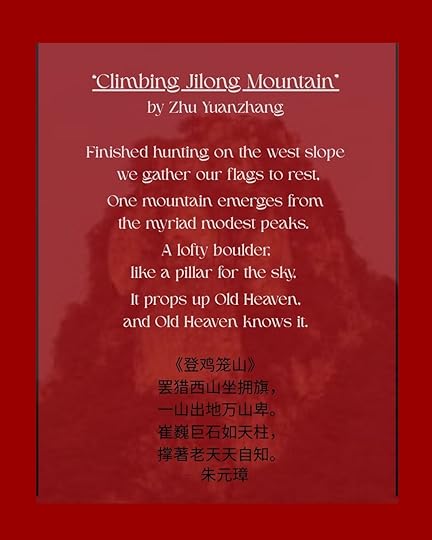

To mark this day, here’s a poem that is attributed to Zhu Yuanzhang. Written in 1355, it’s titled “Climbing Jilong Mountain” and describes the view of a summit near today’s Hexian, Anhui Province, located along the northern banks of the Yangtze River:

It is said that Zhu Yuanzhang wrote this poem while viewing Mount Jilong with his wife, the future Empress Ma. This would have been when he was a rising leader, one among many in the Red Turban rebellion raising armies to fight the Mongol Yuan Dynasty. He had not yet managed to get his army across the Yangtze, but already he had his sights on the city known today as Nanjing, the place where he would launch his dynasty.Finished hunting on the west slope,

罢猎西山坐拥旗,一山出地万山卑。

we gather our flags to rest;

One mountain emerges,

from the myriad modest peaks.

A lofty boulder, like a pillar for the sky;

It props up Old Heaven,

and Old Heaven knows it.

崔巍巨石如天柱,撑著老天天自知。

Zhu Yuanzhang is writing about a mountain, but these lyrics have also been read as a bold declaration of his ambitions. He is the lofty boulder emerging to dominate the landscape.

How did his future empress respond to the recitation of such a poem? Did she scoff at his audacious words? Clap her hands in delight? Or lower her eyes and hold her tongue?

No mere mortal could have guessed the extent of the role Zhu Yuanzhang would play in the annals of Chinese history once he crossed the river.

Only Old Heaven understood how this one young man was about to change the world.

October 20, 2024

The anthem of the Red Turban Rebellion

Happy Birthday Ming Founder!

October 21, 2024, marks the 696th birthday of Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of China’s Ming Dynasty.

He was born in 1328, founded the Ming Dynasty in 1368, and died in 1398.

To be more specific, he was born in an Earth Dragon year on the Dingchou 丁丑 day of the 9th month of the 1st year of the Tianli 天曆 reign of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty’s Wenzong 元文宗 Emperor Tugh Temur. It’s a date that corresponds to October 21 in the modern Gregorian calendar.

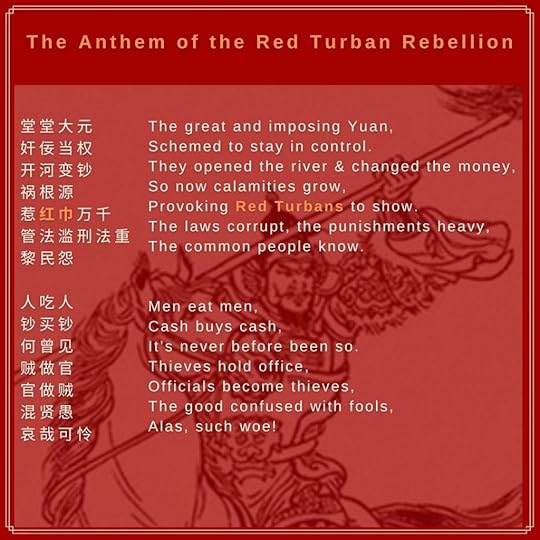

Last year I marked this day by publishing an updated version of my translation of the biography Zhu Yuanzhang wrote in 1378, the tenth year of his reign.

This year, I am marking it with a song. It’s an incendiary lyric with no title by an anonymous author and it describes, in catchy rhyming phrases, the political and economic breakdown in the 1350s that resulted in the Red Turban rebellion. The same rebellion that Zhu Yuanzhang joined and eventually led, fighting his way from Anhui Province south across the Yangtze River to the city known today as Nanjing, where he established the dynasty that replaced the Mongol Yuan: the Great Ming.

According to the scholar Tao Zongyi 陶宗仪, who lived through this era, the song was soon on everyone’s lips. He included the words in his vast collection of anecdotes, noting “I don’t know who created this lyric to the Zui Tai Ping tune, but from the capital to Jiangnan, everyone can recite it.” (《醉太平》小令一阕,不知谁所造。自京师以至江南,人人能道之。)

Here’s my translation:

堂堂大元奸佞当权

开河变钞

祸根源

惹红巾万千

管法滥刑法重

黎民怨

人吃人

钞买钞

何曾见

贼做官

官做贼

混贤愚

哀哉可怜 The great and imposing Yuan,

Schemed to stay in control.

They opened the river & changed the money,

So now calamities grow,

Provoking Red Turbans to show.

The laws corrupt, the punishments heavy,

The common people know.

Men eat men,

Cash buys cash,

It’s never before been so.

Thieves hold office,

Officials become thieves,

The good confused with fools,

Alas, such woe!

This lyric is referring to two interrelated causes of the fall of the Yuan Dynasty: Chancellor Toghto’s massive project to open up a new channel for the Yellow River, and changes to the depreciating paper money system driven by the government’s increasing need for funds.

It’s ironic that the river project and the paper money system were both, in many ways, historic successes for the Yuan Dynasty. The channel project was intended to put an end to the disastrous cycle of flooding for a river known as “China’s sorrow.” As John Dardess pointed out in his 1973 history of the late Yuan, “Toghto’s desire to accomplish something of genuine historical significance was realized. The rerouting of the Yellow River was one of the greatest hydraulic projects ever undertaken in China in premodern times.” And the issuance of paper money was even more significant. A recent article on paper money in Yuan China in The Economic History Review concludes that, “The Yuan was the world’s first regime that used paper money as the sole medium of exchange, marking a milestone in global financial history.”

However, these achievements came at a cost. Over 150,000 people were rounded up as conscripts and forced to spend months dredging the new path to the sea for the Yellow River.

Out came the red turbans.

It is said that the Red Turban Rebellion, which brought down the Yuan Dynasty, started in the first weeks of the river rechanneling project, among a group working at a section called Huangling Gang 黄陵冈, northeast of Kaifeng. They tied red cloths around their heads to mark themselves as a divine army fighting demons in the form of the Mongol Yuan. They claimed to be driven to rebellion by prophecies about “stirring the Yellow River.” (I have written a short story about this.)

Chancellor Toghto spent the remaining four years of his life chasing down the Red Turbans. He never succeeded. And at the time of his death, an obscure Red Turban leader was emerging in the walled city of Chuyang (today’s Chuzhou in southern Anhui). His name was Zhu Yuanzhang. And his birthday is October 21st.

October 20, 2023

The Ming Founder’s story – in his own words!

I have updated my annotated translation of Zhu Yuanzhang’s autobiographical text, known as the Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming 大明皇陵之碑.

Click here to download a free (November 2023) PDF of this text.

Leave me a comment if you have any suggestions for this translation, which is an ongoing project…

One of the remarkable aspects of the Imperial Tomb Tablet is what it does not do: Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty, who ruled the Celestial Kingdom for 30 years after ascending the Dragon Throne in 1368, does not dwell on his military exploits. The first third of this 96-line text gives no indication of the battles won or the armies defeated. This disinterest in bragging is made clear from the opening line, when Zhu begins by describing himself first as a filial son, and second as an emperor. The only other times when he refers to his royal status, is when he describes his parents as “imperial,” though that was a posthumous title for them.

As background: soon after becoming emperor in 1368, the Ming founder transformed his family’s burial place in Fengyang, modern Anhui Province, into a grand imperial cemetery for the House of Zhu. He ordered that a stone tablet be placed before the graves, and carved with the words he wanted his descendants to read and ponder for generation after generation. The PDF monograph listed above is my translation of these words.

It should also be noted that this text is a second draft. The first was composed by Wei Su, a respected Confucian scholar, and written in consultation with the emperor soon after the dynasty was founded, but Zhu Yuanzhang came to dislike it. He decided to write a new version himself, and his text still stands today, carved into stone and erected at the site of his parents’ burial.

So what is different? Zhu’s final draft is far more personal, more emotional, and more tragic:

• Where Wei Su wrote, “In the Jiashen year, the Imperial Father and Imperial Mother Chen both passed away,” Zhu ignored the date and mourned, “All at once, calamities gripped the land and my family met with disaster. My imperial father had reached the age of 64, and my imperial mother 59, when they perished.”

• Wei Su noted politely that the poor family had no burial plot, while Zhu angrily named his landlord, Liu De, as a bad person who “would not attend to our needs, carrying on with his arrogant shouting” until the landlord’s elder brother came to the family’s rescue with the offer of a final resting place.

• Wei Su indicated that the orphaned young man faced an uncertain future, but Zhu cried out “what did I have but fear to the point of madness?”

Clearly, the emperor wanted his descendants to understand the tragedy that he had managed to survive, but that claimed his parents and eldest brother. Moreover, he wanted to express gratitude for those who had helped him – he stresses the kind landlord’s brother, and also his neighbor Old Mother Wang, who got him admitted to the nearby temple so that he would not starve to death. Most touching is his description of the sacrifice made by his surviving brother, who left the village to roam the countryside in search of food and thus left all that remained to eat (meager though it was) for Zhu Yuanzhang. “My brother wept for me, and I grieved for my brother; under the bright sun in Heaven, our sorrow rent our hearts.” Zhu never saw this brother again, and it is quite possible that he soon starved to death in the devastated region.

It is the emperor’s willingness to face his raw emotions that makes this text so unusual, and so gripping. And because this particular struggling orphan went on to become the ruler of China, the story of his family provides an extraordinary insight into the world of 14th-century peasant

For me, the most important reason to read this text, is that Zhu Yuanzhang’s words reach across time and place to offer insight into what makes us human – the struggle to survive, the compassion of friends and family, the need to write it all down for future generations to contemplate.

Happy 695th birthday to the Ming founder!

Zhu Yuanzhang was born on what we would now call October 20, 1328.

To mark his 695th birthday, I have updated my annotated translation of his autobiographical text, known as the Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming 大明皇陵之碑, or the Huangling Bei.

Click here to download a free PDF of this text.

Leave me a comment if you have any suggestions for this translation, which is an ongoing project…

Soon after becoming emperor, Zhu transformed his family’s burial place in Fengyang, modern Anhui Province, into a grand imperial cemetery for the House of Zhu. He ordered that a stone tablet be placed before the graves, and carved with the words he wanted his descendants to read and ponder for generation after generation. The PDF monograph listed above is my translation of this text.

One of the remarkable aspects of Imperial Tomb Tablet is what it does not do: Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty, who ruled the Celestial Kingdom for 30 years after ascending the Dragon Throne in 1368, does not dwell on his military exploits. The first third of this 96-line text gives no indication of the battles won or the armies defeated. This disinterest in bragging is made clear from the opening line, when Zhu begins by describing himself first as a filial son, and second as an emperor. The only other times when he refers to his royal status, is when he describes his parents as “imperial,” though that was a posthumous title for them.

It should also be noted that this text is a second draft. The first was composed by Wei Su, a respected Confucian scholar, and written in consultation with the emperor soon after the dynasty was founded, but Zhu Yuanzhang came to dislike it. He decided to write a new version himself, and his text still stands today, carved into stone and erected at the site of his parents’ burial.

So what is different? Zhu’s final draft is far more personal, more emotional, and more tragic:

• Where Wei Su wrote, “In the Jiashen year, the Imperial Father and Imperial Mother Chen both passed away,” Zhu ignored the date and mourned, “All at once, calamities gripped the land and my family met with disaster. My imperial father had reached the age of 64, and my imperial mother 59, when they perished.”

• Wei Su noted politely that the poor family had no burial plot, while Zhu angrily named his landlord, Liu De, as a bad person who “would not attend to our needs, carrying on with his arrogant shouting” until the landlord’s elder brother came to the family’s rescue with the offer of a final resting place.

• Wei Su indicated that the orphaned young man faced an uncertain future, but Zhu cried out “what did I have but fear to the point of madness?”

Clearly, the emperor wanted his descendants to understand the tragedy that he had managed to survive, but that claimed his parents and eldest brother. Moreover, he wanted to express gratitude for those who helped him – he stresses the kind landlord’s brother, and also his neighbor Old Mother Wang, who got him admitted to the nearby temple so that he would not starve to death. Most touching is his description of the sacrifice made by his one surviving brother, who saw that there was only enough food to support one, and so left the village to roam the countryside and leave Zhu with all that remained. “My brother wept for me, and I grieved for my brother; under the bright sun in Heaven, our sorrow rent our hearts.”

It is the emperor’s willingness to face his raw emotions that makes this text so unusual, and so gripping. And because this particular struggling orphan went on to become the ruler of China, the story of his family provides an extraordinary insight into the world of 14th century peasants.

For me, the most important reason to read this text, is that Zhu’s words reach across time and place to offer insight into what makes us human – the struggle to survive, the compassion of friends and family, the need to write it all down for future generations to contemplate.

May 24, 2022

My short story on a 14th-century uprising

Spittoon Collective, an arts group based in Beijing, is featuring my short story, “Stirring the Yellow River,” this month on their website. Of course, I wish I could actually go to Beijing and hang out with book people, but having a group like this offer my story, along with an illustration, a Q&A, and even a commentary, is the closest I can get to a writer’s dream come true in the COVID lockdown era. I’m so grateful!

(Illustration by Kerry Dennis)

(Illustration by Kerry Dennis)“Stirring the Yellow River” is my fictionalized version of the 1351 uprising that launched the Red Turban rebellion, which eventually led to the downfall of Mongol rule over China. It’s a bizarre tale that involves a one-eyed stone man, laborers dredging the Yellow River, and an apocalyptic rhyme brought to life.

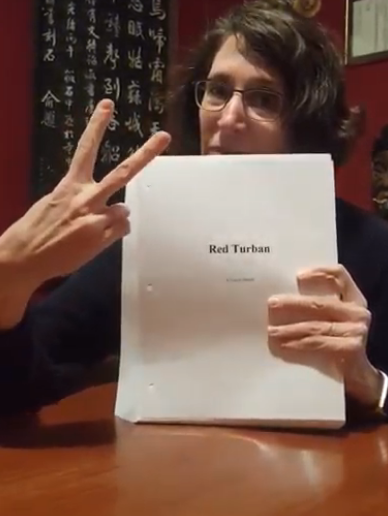

This story is also a selection from the start of Book 2 (which I am calling “Red Turban”) in my series of fiction about the Ming founding. I have finished the manuscript for this one, but I’m still tinkering and editing…

As I explained to Spittoon editor Deva Eveland, “Stirring the Yellow River” follows events described in unofficial writings that circulated in the 14th century by authors like Ye Ziqi 叶子奇 in his 1378 essay collection, Master of Grass and Trees 草木子. (These have been analyzed in English by the modern historians Barend ter Haar and the late Hok-Lam Chan.)

Ye Ziqi was interested in rumors and prophesies and wrote that a certain Han Shantong 韩山童 and his conspirators craftily buried a one-eyed stone man and waited for it to be unearthed by laborers working on a massive river channeling project. A prophetic children’s rhyme, and its connection to the stone man and the uprising, was also mentioned in various accounts, including by the historian Song Lian 宋濂 in the official Yuan Dynasty history, who wrote that, “It all started in the Gengyin year (i.e. 1350) with the children’s ditty told north and south of the river…” Were the rhymes and rumors true? Who can say? They probably contained a mixture of fact and fantasy.

One problem I encountered in writing my own version of this story was explaining why Han and his key co-conspirator Liu Futong 刘福通 were down in the trenches talking with the laborers. The historical records are silent on this matter, and don’t have much to say about the background of either leader. What made the most sense to me was to make Han and Liu fellow conscripts. So each retelling of this story creates its own deviations.

How does this story connect with the Ming founding, which is the focus of my historical fiction? Liu Futong went on to lead the northern branch of the Red Turbans, which a peasant-turned-monk named Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋 joined in early 1352. Zhu rose through the ranks and eventually became the most powerful Red Turban in the land. He founded the Ming Dynasty in 1368, and scholars consider the word “Ming 明” to be a reference to the religious beliefs unleashed in the river channeling rebellion.

Meanwhile, here’s the short story:

Stirring the Yellow River

March 21, 2022

The cringey world of book promotion

I did not realize, in my dreams about getting a book published, that promotion would be such a big part of the process. Then I started attending conferences for writers and learning about the need to pitch to agents and “have a platform.” With my first book finally out, I felt overwhelmed with all the social media I was supposed to be using to talk about my book. Who has time for all that? I asked a friend in the business which social media platform is best. “All of them,” she replied. I vowed I would not pester my friends and family on Facebook. And yet I did. And here I am, talking about my book on Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, this website. I’ve made cringey Tiktoks. I’ve tried to make a podcast and learned that it’s hard to sound off-the-cuff interesting, especially when you can’t resist reading from a script. “Don’t read from a script,” my kids told me. But I’m all about scripts – I’m a writer!

I’ve also learned that I’m not alone in trying to figure out the world of book promotion. There are some bad ideas out there – like the guys who message me on Instagram offering to review my book for $20 bucks. But there are also interesting innovations – like Bookshop.org, which supports local, independent bookstores, and Shepherd.com, which is intended to help authors meet readers.

Photo above: My list on the new platform for books, Shepherd.com

Photo above: My list on the new platform for books, Shepherd.comLaunched in 2021 by Ben Fox and with a name intended to evoke “discovery, exploration, and gentle guidance,” this website resulted from dissatisfaction with the experience of finding books on Amazon and Goodreads. Shepherd.com has authors create lists of five books that are related to their own book and explain why. The list is titled with a “best” book motif, because Ben says “95% of book searches on Google include that phrase, and in user testing, we found that users think that way when looking for a book.”

So my contribution is a list of “The best books for entering the world of imperial China.” Click here to see my five selections.

I remember when I first contemplated setting up a Twitter account. “I don’t have anything to tweet about,” I complained to a savvy, younger friend.

“Don’t worry, you’ll think of something,” she assured me.

And now my account lists 653 tweets. How is that even possible?

A new entry in the world of book promotion

I did not realize, in my dreams about getting a book published, that promotion would be such a big part of the process. Then I started attending conferences for writers and learning about the need to pitch to agents and “have a platform.” With my first book finally out, I felt overwhelmed with all the social media I was supposed to be using to talk about my book. Who has time for all that? I asked a friend in the business which social media platform is best. “All of them,” she replied. I vowed I would not pester my friends and family on Facebook. And yet I did. And here I am, talking about my book on Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, this website. I’ve made cringey Tiktoks. I’ve tried to make a podcast and learned that it’s hard to sound off-the-cuff interesting, especially when you can’t resist reading from a script. “Don’t read from a script,” my kids told me. But I’m all about scripts – I’m a writer!

I’ve also learned that I’m not alone in trying to figure out the world of book promotion. There are some bad ideas out there – like the guys who message me on Instagram offering to review my book for $20 bucks. But there are also interesting innovations – like Bookshop.org, which supports local, independent bookstores, and now a brand new experiment, Shepherd.com.

Photo above: My list on the new platform for books, Shepherd.com

Photo above: My list on the new platform for books, Shepherd.comLaunched less than a year ago by Ben Fox and with a name intended to evoke “discovery, exploration, and gentle guidance,” this new website resulted from dissatisfaction with the experience of finding books on Amazon and Goodreads.

Here’s how Ben explains what he is trying to do:

For Readers – I love wandering around bookstores and letting random books capture my attention. Nothing will ever replace the “bookstore experience”, but I want to reimagine book discovery online with a lot more serendipity and delight.

For Authors – I want to help authors meet more readers. Authors illuminate our world, take us on faraway journeys, and entertain us. There is a growing trend that authors have to become their own marketing team. That concerns me because it is very difficult to do. I want to make this easier.

It is very difficult! His model is to have authors create lists of five books that are related to their own book and explain why. The list is titled with a “best” book motif, because “95% of book searches on Google include that phrase, and in user testing, we found that users think that way when looking for a book.”

So my contribution is a list of “The best books for entering the world of imperial China.” Click here to see my five selections.

I remember when I first contemplated setting up a Twitter account. “I don’t have anything to tweet about,” I complained to a savvy, younger friend.

“Don’t worry, you’ll think of something,” she assured me.

And now my account lists 653 tweets. How is that even possible?

Shepherd.com is just getting going, but already its “China bookshelf” lists 288 volumes. I clicked on a recent addition by Peter Zarrow, a historian at the University of Connecticut. Five great suggestions!

And so it begins.

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-6239588f62eeb', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

__ATA.cmd.push(function() { __ATA.initDynamicSlot({ id: 'atatags-26942-6239588f62eeb', location: 120, formFactor: '001', label: { text: 'Advertisements', }, creative: { reportAd: { text: 'Report this ad', }, privacySettings: { text: 'Privacy', } } }); });

January 24, 2022

Hoping to get Book 2 out in the Year of the Tiger

I recall being in a taxi in China several years ago, I think in Shanghai, shortly before the Lunar New Year holiday, when a pedestrian jumped in the path of our car.

It’s still getting edits and comments, but here is the manuscript for Book 2!

It’s still getting edits and comments, but here is the manuscript for Book 2!The driver slammed on his brakes and – in the same motion – rolled down his window, so that he could yell at the hapless pedestrian even as we were skidding to a halt to avoid running him over.

“要过年吗?!” (Loose translation: “Were you hoping to live to celebrate the New Year?!”)

The taxi driver’s words were superficially polite but uttered with such vehement anger and sarcasm that they turned into an insult, a seasonal version of, “Get out of the way, you idiot!” I remember – once I recovered from the shock of the near accident – feeling amused by the driver’s aggrieved tone and aggressive wit.

The new moon February 1 on the Western calendar for 2022 marks the start of the Year of the Tiger. It’s a year when I hope to see Book 2 published in my series on the founding of the Ming Dynasty. Under the current title of Red Turban, this volume will cover the tumultuous four years, 1351-55, that turned Zhu Yuanzhang from an obscure wandering monk to a leading warlord contending for control of all of China, and brought the future Empress Ma to his side. The manuscript is currently undergoing edits, but has taken full form and benefited from reader comments (please email me if you would like to receive notifications about it).

So I am looking forward to the lunar New Year, and I intend to channel that taxi driver’s nerve and wit in the face of the anxiety of getting a novel published.

Happy Year of the Tiger!

July 9, 2021

Crossing the river

Though I’m not into numerology, it did give me pause to realize that one of the key moments in the founding of the Ming Dynasty occurred exactly 666 years ago.

On the second day in the sixth month of an Yiwei year that corresponds to the Western date of July 10, 1355, Zhu Yuanzhang led his newly-acquired fleet from Hezhou, his temporary base on the northwest bank of the Yangzi River. He was headed toward a outcrop on the far shore known as Ox Barrier. One of Zhu’s newest recruits, Chang Yuchun, was the first to make landfall. Chang jumped to the shore, wielded his ax and rushed toward the Mongol troops. Zhu Yuanzhang’s Red Turbans surged behind Chang’s charge and routed the imperial army from their fort in the cliffs. Chang’s attack was so heroic that it is said you can still see his footprint in the boulders above the site of the landfall.

Such are the tall tales told of that fateful moment.

I consider this river crossing to be such an important date because it marks when Zhu Yuanzhang emerged as a military leader in his own right. Born a peasant in rural Anhui Province, he served in a Buddhist temple for several years before joining the Red Turban uprising in 1351. Zhu fought under the banners of a local bravo known as Guo Zixing, who recognized Zhu’s talent, married him into his household, and began promoting him among the ranks. It was a difficult relationship in a tempestuous era, but Zhu did not waver in his support of Guo until Guo’s death in early 1355. Then all bets were off and the entire Guo clan was dead by the end of the year, save a girl who was either Guo Zixing’s daughter or granddaughter, and later became the mother to five of Zhu Yuanzhang’s many children.

Taking an army across the Yangzi was no small matter. Zhu Yuanzhang had no boats and had never even seen the Yangzi when he first began to contemplate crossing China’s longest river to set up a base in the city we now call Nanjing. The advisors around Zhu filled his head with the idea of leaving the poverty and suffering of the Huai River Valley for the wealth and comfort of the south. They told him that Nanjing was a place where the dragon coiled and the tiger crouched – an ancient capital where a hidden talent could emerge as a conqueror.

This idea proved irresistible. So even as he was grieving the death of his mentor, Guo Zixing, Zhu was also meeting with a band of boat families feeling hemmed in and oppressed in Lake Chao. They needed to escape, they needed protection, and they had boats. A lot of boats.

This was the fleet that carried Zhu Yuanzhang’s soldiers across the Yangzi. It still took several years for Zhu to found the Ming Dynasty in 1368. However, this breakthrough moment is what put Zhu on the national stage. It was one of what I consider the three key dates that led to the Ming: the others being 1344, when Zhu lost his family to the plague and was forced off his life trajectory; and 1363, when he defeated Chen Youliang in the most significant battle of fourteenth-century China.

The story of the Yangzi crossing is also the subject of my latest novel, which I am writing now, sitting at my desk with a glass of wine wondering what it was like to cross that churning river in 1355, a devilish 666 years ago today.

April 13, 2021

IndieReader “All About the Book” Profile

Not sure how long it will last, but right now I’m featured on the home page of IndieReader.com. Whoop whoop! My book, the Lacquered Talisman, is among four profiles, and I’m in good company with Suzanne Tierney’s WWII historical fiction, and WG Hladky’s award-winning science fiction.

My profile discusses why I decided to write a novel about the founder of the Ming Dynasty, who I’d pick to play him in a movie, and more. Happy reading!