Sarah Airriess's Blog

February 13, 2025

In Praise of Radio Drama

Dear BBC Radio,

I started listening to BBC Radio online, from Vancouver, in 2005, at the tender age of 23. It started with Radio 4, which struck me as the platonic ideal of the broadcasters with which I’d grown up. One of its major differences was its wealth of drama – neither NPR nor the CBC had dramas at all regularly, and when one did appear it was usually dire. Radio 4’s schedule had an incredible range of dramatic offerings, in every genre, all tremendously well-produced and performed.

I was working in animation, which involved long stretches of tedious technical drawing, and I quickly formed a symbiotic relationship with Radio 4. A drama could keep my pencil moving uninterrupted for its duration, and my productivity soared. I consumed them compulsively, and was abundantly rewarded. Twenty years later I cannot count the number of literary works and histories I would never have come across but for the work of the Radio Drama Department, which have expanded my horizons, enriched my experience of humanity, and made me who I am. That’s not rhetorical: It was a radio drama that interested me in polar history, and I am now an Institute Associate at the Scott Polar Research Institute, making a series of graphic novels about Scott’s last expedition, in the course of which I have moved here and become a British citizen. Stories are powerful!

As I grew more familiar with the BBC’s programming, I noticed that many of my favourite productions fell under the banner of Drama on 3. These always seemed a notch above the rest, being more ambitious, stimulating, creative, or profound. As my job changed, and I began to spend more time writing than drawing, I had less time to lose myself in audio drama. When I was free to listen, I would go first to Dramas on 3, as those were the ones I would most regret missing.

So it was a great surprise to hear that the BBC intended to cut this drama slot entirely. Not reduce new commissions in favour of reruns, not move it to another station, but completely eliminate the feature-length drama from the programming slate. Drama on 3 is the best the medium has to offer, not just on the BBC but anywhere, and wiping it out is like Hollywood giving up on making Oscar bait. Many have argued that radio is a valuable training ground for up-and-coming writers and performers – Drama on 3 is where they really get to spread their wings and show us what they have in them. It’s also profoundly accessible: whether the listener is a North London pensioner, a Middlesborough decorator, or a trainee animator in Vancouver, Drama on 3 brings everyone, everywhere, an equal opportunity to enjoy great theatre, great literature, and great radio, regardless of whether they can afford a ticket, travel, or a university education. If that’s not what the BBC is for, then tell me what is! It informs, educates, and entertains, for a fraction of the cost of one episode of Doctor Who. I appreciate that budgets are under strain and cuts have to be made, but this? Really? Its loss will add only a little to the bottom line – is that worth what it will cost us all to lose it?

If low listening figures are behind this decision, I can only think this is a matter of publicity. I have Radio 3 and 4 on almost constantly; I scarcely ever hear a promo for Drama on 3. Its slot at dinnertime on Sunday means people are unlikely to catch it live, and they can’t look it up on Sounds afterwards if they don’t know about it.

The BBC ought to be proud of the gem in its audio drama crown, and draw attention to it, instead of hiding it under a bushel and then shrugging if no one listens. This age is voracious for audio. Streaming platforms are investing in audiobooks and podcasts, with dramas as prestige productions, often poaching talent from the BBC. My former animation colleagues, who listened to music while I was listening to Radio 4, are now all hooked on podcasts. Everyone I know is trying to ration their intake of news; what better alternative than something as enriching as Drama on 3? The audience is already there, it’s just a matter of letting them know what’s available. You will never know how much Drama on 3 could be appreciated if you cut it before they know it exists.

Please take a step back and look at radio drama in the wider context of the BBC’s remit. It’s a unique aspect of BBC Radio, and an art form in which Britain leads the world. Drama on 3 is the exemplar, not an expendable extra. It’s not just worth saving, it’s worth celebrating.

Yours sincerely,

Sarah Airriess

July 16, 2023

Antarctic Food

Below you will find my account of eating at McMurdo, but PBS did a whole special on it which has more privileged access and, like, moving pictures and stuff. I highly recommend watching that if you're at all interested in the food question.

As other pleasures in life are restricted or eliminated, food gains significance beyond mere nutrition. When removed from the comforts and diversions of civilisation for months or years at a time, polar explorers had to pay particular attention to the culinary side of their enterprise. Scott learned this the hard way on the Discovery, when their cook was so bad he was sent home after the first year and others took over his job in shifts. Shackleton, on his second visit to Antarctica, brought all sorts of tinned delicacies, and left a lot of them behind in his hut at Cape Royds, which the Terra Nova men would raid on day trips from Cape Evans. Scott was much more careful with his choice of cook on his second expedition, and in his journal he continually praises Clissold's cooking – though Atkinson, writing for a publication he knew no one would read, says that Archer (the ship's cook, who filled in after Clissold was invalided home) was a far superior chef, and made the miserable second winter that much more bearable.

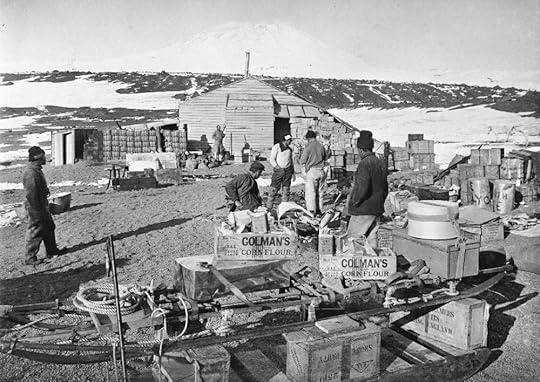

The expeditions of the early 20th Century brought down crates and crates of imperishables – tinned vegetables, powdered milk and eggs, and dry goods like flour, sugar, and tea. These were necessary, of course, but were ultimately supplemental to the core of their diet, which was the produce of Antarctica itself. In fact, in a letter laying out contingency plans if the Terra Nova Expedition were stranded in Antarctica, Scott says not to worry for their safety because the continent provides enough food to keep a party happily fed; they would only be wanting the comforts of a civilised menu. Mostly what the continent provided was seals, whose meat (especially livers) contained enough Vitamin C to stave off scurvy, but penguins and their eggs also regularly passed through the kitchen, and the contents of the marine biologist's net – once properly enumerated and dissected, of course – would often end up in the frying pan. The Notothenia fish was commonly eaten at breakfast, appreciated for its 'sweet' and 'nutty' flavour. Notothenia’s claim to fame is the sugar in its blood that acts as an antifreeze, so this is hardly a surprise.

Thanks to the Antarctic Treaty forbidding the killing of animals for consumption, modern Antarctic larders are not stocked with local wildlife, and as far as I know, no one down there now has tasted the sweetness of Notothenia. They do, however, have the advantage of modern transport and food storage, not to mention a century's worth of advances in the study of nutrition, so the diet of the present-day Antarctican is fresher, healthier, and much more diverse.

McMurdo Station's annual food supply arrives in one lump delivery, every January, on a big cargo ship from California. From the harbour where the Discovery berthed, it goes into climate-controlled storage, either to the dry goods store or to the freezer, which is a whole building off the cafeteria in the main station hub. A freezer, in Antarctica? Why, yes, because food safety regulations require frozen food to be kept at a constant temperature, and the only way to ensure that is to build an enormous manmade freezer in the land of ice and snow. In the summer, temperatures at McMurdo will wander around freezing, so this is entirely practical, but for much of the year, it's actually warmer inside the freezer than outside.

The modern Antarctic commissariat is not entirely divorced from its Edwardian predecessor, though – frozen vegetables taste fresher than tinned, and are more nutritious and palatable, but they are not fresh; powdered milk and powdered eggs are still the status quo. During the summer, perishable groceries – called 'freshies' – come down on the flights from New Zealand, if there is room after the passengers and equipment are loaded. After a month of flight cancellations, fresh apples and oranges are greeted with as much delight as they were on the arrival of relief ships in the Heroic Age, and the appearance of a salad bar in the Galley prompts general rejoicing.

The US Antarctic Program has its roots in the Navy, and McMurdo is still provisioned by one of the big firms that supplies the US military. Having had experience with industrial-scale American catering in California, I had moderate expectations of the quality of food at McMurdo, but it was surprisingly good. One might argue that the excitement of being there and the daily energy expenditure would be a good sauce for anything, and this may be true, but against this I would argue that dry air impedes one's ability to taste – that fact it was so flavourful at all is significant. People kept apologising for the food in the Galley and I kept telling them, earnestly, that it was better than the food in the Disney commissary. They didn't believe me, but I firmly attest this; I ate at Disney on my return journey and have confirmed it by direct comparison. I know they were working with roughly the same quality of ingredients, but the chefs at McMurdo reliably made things delightful to eat, which is more than I can say for the other place. Why this should be is anyone's guess ... Working as a Galley Rat is one of the few ways enthusiasts can get down to the Ice, so it's full of keen, intelligent, and curious cooks, and maybe that rubs off on the food. There are people who come back to tackle the unique challenges of Antarctic cuisine year after year, so maybe they're more experienced and invested in the job. My personal theory is that because they have to eat the food, too, of course they're invested in making it tasty – I suspect the folks behind the counter in LA have much better meals waiting for them when they get home.

Mealtimes follow a strict schedule:

5:30-7:30 Breakfast (many a time I missed the cutoff, woe)

11:00-13:00 Lunch

17:00 to 19:30 Dinner. There was always a portion of the cafeteria serving breakfast food at this time; this was reserved for the night shift workers, who got a reprise of the day shift's dinner for their lunch. If you really liked whatever was served for dinner, nothing could stop you coming around again for another go at midnight.

The one exception to this was Sunday, when a brunch would be served from 10 to 12. The service in the chapel started at 10 as well, and was very weak competition. Brunch was always excellent, and being the single day off, was often where one would meet up with people who were too busy during the week.

If you failed to make a mealtime for any reason, there was always something on offer. A fridge would be stocked with packaged leftovers, sandwiches, and other food-to-go – when I had a day out, I would eat breakfast and then grab my lunch from this fridge. On one occasion, dinner included fried okra (one of my faves, rarely had outside the States) and after stuffing myself with it, I nabbed two or three extra portions and cached them in my dorm room mini-fridge to enjoy later.

In a challenging environment, with a lot of people doing energy-intensive jobs, calories are important. There was only one rule regulating portions: Take what you want, but eat what you take. With a finite amount of food on hand, and delivery only once a year, food waste is anathema – if you need it, then eat it, but do not throw any away.

The menu seemed to originate with whatever presented itself in the enormous freezer, though perhaps in November and December it was dictated more by what remained in it, prior to the new shipment. We didn't suffer for want of variety, though: if anything, we benefited from a surfeit of prawns, including great bowls of them at Sunday brunch. I found myself wondering if the US military had a contract for most of the catch from the Gulf, and how much of their famously inflated budget went into that; I suspect, in reality, the kitchen just hit a seam of prawn in the recesses of the freezer and had to use it up. As a devotee of all shapes of sea bug, I was in seventh heaven, and did my level best to help McMurdo clear the surplus.

Once new food was defrosted and cooked up, it would cascade through various dishes down the week, as leftovers were repurposed to minimise waste. Usually this was successful, but sometimes they had to try a little harder ...

A variety of cuisines were offered, some of which were more successful than others. They seemed to reflect the makeup of the US military, for whom the rations would have been designed. The best dishes were the meat-and-potatoes variety (my minder said that if she were on Death Row, she'd ask for McMurdo Pot Roast for her last meal), Italian, Southern (see above re: okra), and what I assume was Tex Mex – the only misstep on the last count was an almost inedibly hot 'taco soup' which may have been more of a delivery vehicle for leftovers than an intentional dish. The only disappointments were anything attempting to be Asian, and the fish, which, due to the circumstances, was always overcooked. Provision was always made for vegetarians and even vegans, but I can't say I noticed many people adhering strictly to those diets. I suppose if the animals are already dead and in the freezer, there's little difference whether you eat them or not.

There was also, always, pizza. It was left in one of those tiered heated racks like you get at a buck-a-slice takeaway pizzeria, but this was no buck-a-slice pizza, this was McMurdo pizza, and McMurdo pizza is AMAZING. My brother-in-law's cousin went to super legit pizza school in Naples, and gets queues down the street wherever he opens a pizzeria. He makes the best pizza I have ever had anywhere; McMurdo’s wasn't quite as good as his, but it was pretty darn close. It's a testament to how good the rest of the food was that I didn't just have pizza for every meal. The pizza kitchen runs 24 hours a day, and takes orders for pickup from all across the base. If you're flying out to a field camp, it's good manners to take their pizza order and deliver it to them hot and fresh. For all the advances in food technology since the Heroic Age, surely the greatest has to be the McMurdo Pizza.

We were reminded constantly how important hydration was, and the Galley offered a range of liquids at all hours. To my surprise, what looked like a soda fountain offered not pop but fruit juice – grapefruit, orange, cranberry, and apple, though one or more often ran out before the end of breakfast. There were enormous urns of extremely weak coffee – a provision, I supposed, for its diuretic effects – though with 10-hour workdays and very early starts, a little more oomph would have gone a long way. Experienced hands, and those of discerning tastes, brought their own coffee or sourced it somehow from the stores. The kitchenette in the Crary library was full of people's personal coffee-making supplies as they sought a more effective brew.

I had been warned that if I liked tea, I should bring my own; this was a sound warning, as the black tea on offer looked and smelled as though it had been on a shelf for about a decade. What I had not been warned about was that the only 'milk' on hand for one's coffee or tea was, in most places, 'coffee whitener', a ubiquitous Americanism which I'd completely forgotten about (or supressed?) since moving away. For those who've not had the privilege of its acquaintance, this is a blend of margarine, sugar, synthetic vanilla, and titanium dioxide, rendered into a powder by some unknown chemical process and packaged up to pass for milk. (I think it might be illegal in Europe. I've certainly not seen it around.) The Galley had the base's only dispenser of actual mammalian lactation – reconstituted from powdered, of course. If I were to go again, I would bring a small bottle to fill there with 'real' milk, which I could take away for tea purposes elsewhere. There were boxes of UHT milk available for purchase in the shop, and had I been staying longer I might have invested in some, but for just a splash per cuppa, it hardly seemed worthwhile.

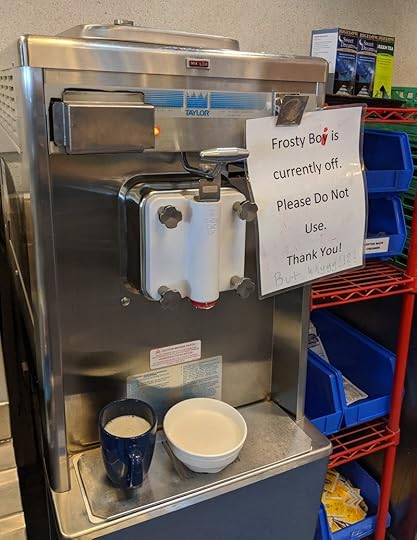

The undisputed star of the Galley was the soft serve ice cream dispenser, named Frosty Boy (or Boi), an ancient beast that was such an institution that it was rumoured the USAP had bought another one from a junkyard just for parts. The Thing to Do was, instead of putting milk or coffee whitener in your coffee, to use a dollop of Frosty Boy instead – I'm not sure which end of the dairy/non-dairy spectrum his product was nearest, but it did go well in the coffee, such as it was. More often than not while I was there, Frosty Boy exuded only a watery splutter rather than creamy delight – even when he was working, the product was rather gritty – but I was assured he was just going through a phase, and would be right again soon. I got the impression that if anyone tried replacing the machine with something more reliable, or which produced something more resembling ice cream, there'd be a protest. We shall see if Frosty Boy survives the station revamp, as the NSF seems keen to scrub out any vestiges of character ...

I have brought two things back from the McMurdo Galley, and they're things that go right back to the beginning: powdered milk and powdered egg. Even when I'm near a shop with both in fresh form, it's convenient to have the powdered on hand for recipes. I really only use milk to splash in my tea and coffee, so don't keep a large amount in my fridge, but recipes often call for far more than I have – so instead of making a trip for the extra, I can just mix it up on demand. I've also taken on the Perpetual Yoghurt: McMurdo makes its own yoghurt from its vast reserves of powdered milk, using a bit of the last batch to inoculate the next, and it turns out this is perfectly doable at home, too. Eggs eaten as eggs are better fresh, of course, but when providing structure in a recipe, no one's going to notice if they've been reconstituted, and then I can save my 'real' eggs for when they'll be appreciated. It's a good system, and economical, too. Alas, the pizza isn't as easy to replicate at home ...

For more information on McMurdo food –

The Antarctic Sun newsletter put out this podcast: https://antarcticsun.usap.gov/features/4329/

I didn't mention how good the desserts were; I was lucky enough to share my time at McMurdo with Rose McAdoo, who was featured in this story on NPR: https://text.npr.org/779463164

July 9, 2023

A Visit to Scott Base

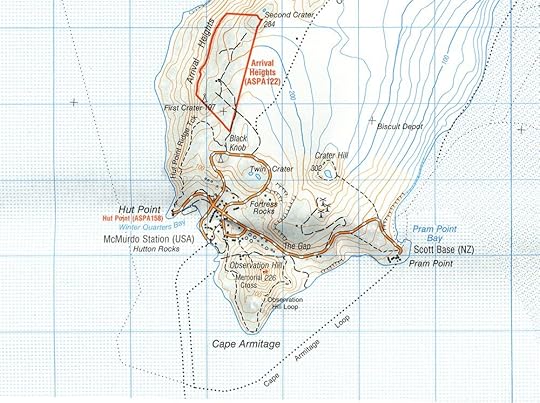

On the other side of the Hut Point Peninsula from McMurdo, on a small cape called Pram Point, is the main New Zealand outpost in Antarctica, Scott Base. It was formally founded in 1957 as the Eastern terminus of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, under the auspices of Sir Edmund Hillary, and "Hillary's Hut" still stands in the compound, lovingly restored and maintained by the same Antarctic Heritage Trust that looks after the historic huts of the Heroic Age.

Being so close to McMurdo, and founded around the same time, it feels a bit like entering an Alternate Dimension when you cross over the hill, where the conversational tones are more mellow, nimble Toyota 4x4s replace brute-force Fords, and the southerly aspect catches the sun best in the middle of the night.

The Kiwis, very wisely, have established kind but firm boundaries: Americans are welcome to visit on Sundays and (if I recall) Thursday evenings, when the shop and the bar are open, but the rest of the time they are politely barred, except by personal invitation. At visiting times, there are regular shuttle vans from McMurdo to Scott Base and back. I visited three times: once, on a Thursday, with the other AAWs, to the shop; once, on a Sunday afternoon, to drop off a memory card for someone who would be turning up that night, and once when I had the honour of being invited to give my Terra Nova talk. Being aware that I was in someone else's home, I didn't snap many pictures on any of these occasions, but I hope what I do have will give you some feel for it.

Pram Point has an important asset for a base: it's near enough to where the Ross Ice Shelf meets land that surface travel south is nearly always possible. Pram Point is mentioned frequently in Terra Nova accounts as the access point to the security of Ross Island, when the sea ice around Cape Armitage was unsafe or absent. Vehicles today still take this route, and drive right past Scott Base on the road between McMurdo and the airfields.

It's only a mile between McMurdo and Scott Base, so on my second visit, it being a fine day, I decided I'd rather get some fresh air and walk my memory card over and back, rather than wait for a shuttle – plus I could take the time to soak in the route I'd read so much about.

The climb out of McMurdo is drab and utilitarian. The station's outdoor storage is stacked up towards the road, so one has to pass row upon row of crates and flat-pack field huts before reaching anything more scenic. The final stretch out of town skirts the giant fuel tanks that supply the station's generators, though the three wind turbines on the other side of the road take up to 30% of that load, sometimes. The Gap – the valley between Observation Hill, to the right, and Crater Hill, to the left – is notoriously windy, so they're well-placed, although they have to be deactivated when the wind gets too strong, which happens fairly often.

Once over the crest, you get a nice view of the south side of Ross Island, across Windless Bight to Cape Mackay:

The smattering of containers in the middle distance isn't one of the airfields, but does provide a handy clue where the edge of the ice shelf meets the seasonal sea ice, which is wrinkling into grey ridges as it comes up to the land. You'd never guess, from this angle, that the near ice is a few feet thick but the ice under the containers is a few hundred, at least.

Coming around this tight bend, and looking the other way, is the 'back' of Ob Hill and – and!! – the ice where the Sea Ice Incident happened!

I'm sorry, I just find that endlessly exciting.

A nice steady roundabout decline, now, as we approach Scott Base. On the way is a metal koru, a memorial to the Air New Zealand crash on Mt Erebus in 1979, and signifier that one is now entering Kiwi territory. Because we are on an unofficial visit today, we are going to bypass the main entrance, with the Maori carving over the door, and instead scoot around the side and up a short flight of steps to the door nearest the shop.

And who should greet us in the vestibule, but ...

The man himself! (Next to a note reminding us not to stamp the snow off our boots here, but use the brush outside. I'm sure he would have supported this policy.)

Scott Base is an Alternate Dimension not just in the day-to-day realities, but because the area's history is more strongly present. McMurdo has the odd relic of its past, but history apparently starts with Operation Deep Freeze in the 1950s; Scott Base, on the other hand, wears Antarctic history on its sleeve, as well as in its name. The shop carries history books and postcards of the historic sites alongside the treats and branded station merch that one can also find at McMurdo. And, I discovered later, there are historic photos up throughout the base, including a massive reprint of the Midwinter Tree photo in the pub.

This shouldn't be at all surprising for the field HQ of the Antarctic Heritage Trust, but it did show up the disconnect I'd been feeling at McMurdo. I was in the very place where the history happened, but beyond the placenames, a photo of the Discovery in the Galley which showed the site of the future base, and one old hut, there was no acknowledgment of the original explorers. Here, though, was a familiar face in the right place, and a little room full of celebrations of the past, and I won't pretend it didn't make me a little emotional. Getting weepy over the Cape Evans postcards would not have been my best foot forward, though, so I purchased a topographical map of the area to add to my Ordinance Survey walking maps back home, and got out before I embarrassed myself.

It was lucky timing at the top of Arrival Heights that got me invited to speak at Scott Base on a non-visiting night. Some Kiwis had come to McMurdo for my big talk in the Galley there, and thought it would be good to bring me over, so when I happened to be up a hill at the same time as an antenna attendant, I got that precious personal invitation that would allow me access on a non-visiting day. It ended up being shortly after Whakaari blew up, so people were understandably distracted. For my part, speaking about the Terra Nova Expedition in front of the people who look after its earthly remains was a little intimidating. And that amount of talking was the nail in my laryngitis coffin, though it probably would have come on eventually no matter what. But the welcome was warm and the chat inclusive, and all in all it was a thoroughly lovely visit to Looking-Glass Antarctica. 12/10, would visit again.

Just like McMurdo, Scott Base is slated for a major redevelopment. I was a little surprised to hear this, as it seemed plenty modern to me already, but I am not the one making these decisions. The new one looks very shiny, and not unlike the airport hostel where I stayed while waiting to fly south. The architectural mockups don't show old photos on the wall, but I trust they will appear in due course, along with the anti-stomping advisories taped up on a printed sheet of A4. It'll be interesting to see how it all shakes down. I hope I'll get to see it, someday.

July 2, 2023

McMurdo Internet

Internet service is supplied to Antarctica via a geostationary satellite. This far south, the satellite is only a few degrees above the horizon, and unfortunately for McMurdo, it's behind Mt Erebus. So the signal is beamed to a receiver on Black Island, about 20 miles away to the southwest, and bounced over to the sheltered alcove at the end of the Hut Point Peninsula where McMurdo sits.

The view to Black Island, as seen from the Chalet at McMurdo Station

The Black Island telecommunications infrastructure was installed in the 1980s, long before the internet we know and love today. It was upgraded in 2010 to allow more data transfer, mainly realtime weather data to feed into global forecast models. For this reason, it's probably the only place I've ever been where upload speed is remarkably faster than download speed – 60Mbps for outbound traffic, but only 20Mbps for inbound. Most regular internet use is receiving, not sending, so that's an entire base running on a connection that's only marginally faster than the average American smartphone. As you can imagine, this is somewhat limiting.

The limits to one's internet access actually begin before one even reaches the Ice. At the orientation in Christchurch, one is directed to a URL from which one must download and install a security programme from the U.S. government. It may feel like a hippie commune full of nerds, but McMurdo is an installation of the American state, and as such its computer network is a target of whatever disgruntled conspiracy theorist decides to hack The Man on any given day. Computers that are allowed onto this network (such as the one on which I am typing right now) have to have an approved firewall and antivirus service installed, then this extra programme on top of them. I am not sure what it does. For all I know the CIA is spying on me even now. (Hi, guys!) But you need to install it to get on the McMurdo Internet, such as it is, so I did.

To be honest, I was rather looking forward to a month cut off entirely from the hyperconnected world, so I was a tiny bit disappointed that quite a lot of day-to-day communication is done by email, and I would need to be on my computer a fair bit to get it. Had I known just how important email would be, I'd have installed an email client that actually downloads one's messages instead of just fetching them; as it was, the cycle of loading an email and sending the reply, even in Gmail's "HTML for slow connections" mode, took about five minutes, not counting the time it took to write. Tending one's email was a serious time commitment; sometimes I felt like I was spending more time on the computer in Antarctica than I did at home.

Scientists in the Crary library working and waiting ... and waiting ... and waiting ...

In a way, though, I was lucky, because I was technically a scientist and therefore had access to the one building on base with WiFi, the Crary Lab. And don't think you can just waltz into Crary with your laptop and poach the WiFi – in order to access it at all, you have to get set up by Crary IT with your own personal WiFi login. If you do not have Crary access, your portal to the Internet is one of a handful of ethernet cables in each of the dorm common rooms, or some public terminals in the main building. You can hop on, download your emails, maybe check the news or Google something you needed to look up, and then leave it for someone else. When most online time sinks are either blocked or too heavy to load, it’s amazing how little internet time you actually turn out to need.

Things that we have come to take for granted in The World are not a part of McMurdo life. Social media is pretty much out – the main platforms are bandwidth hogs even before you try to load a video or an animated GIF. There is no sharing of YouTube links, and no Netflix and chill. Someone was once sent home mid-season for trying to download a movie. Video calls with family and friends? Forget it. People do occasionally do video calls from Antarctica, often to media outlets or schools, but these have to be booked in advance so as to have the requisite bandwidth reserved. Jumping on FaceTime does not happen – not least because handheld devices have to be in airplane mode at all times for security reasons. Your phone might be secure enough for your internet banking, but not for US government internet!

It is, unavoidably, still a digital environment, it just gets by largely without internet access. Nearly everyone has an external hard drive, mostly for media that they've brought down to fill their off hours. If you want to share files you just swap hard drives, or hand over a memory stick. When the Antarctic Heritage Trust wanted some book material from me, I dropped it onto an SD card and ran it over to Scott Base on foot – a droll juxtaposition of high- and low-tech, not to mention a good excuse for a hike over The Gap on a beautiful day. It took half an hour, but was still faster than emailing it.

There is also a McMurdo Intranet, which includes a server for file sharing. Emailing someone your photos will take ages, but popping them into a folder on the I: drive and sending them a note to say you've done so (or, better yet, phoning them, or poking your head into their office) is much more efficient. To conserve space, this informal server partition is wiped every week, so you have to be quick about it, but it's an effective workaround, and also a good way to get relatively heavy resources to a large number of people in one go.

The telecommunications centre on Black Island is mostly automated, but like anything – perhaps more than some things, given the conditions – it needs to be maintained. There is a small hut out there for an equally small team of electricians and IT engineers; Black Island duty attracts the sort of person who might have been a lighthouse keeper back in the day.

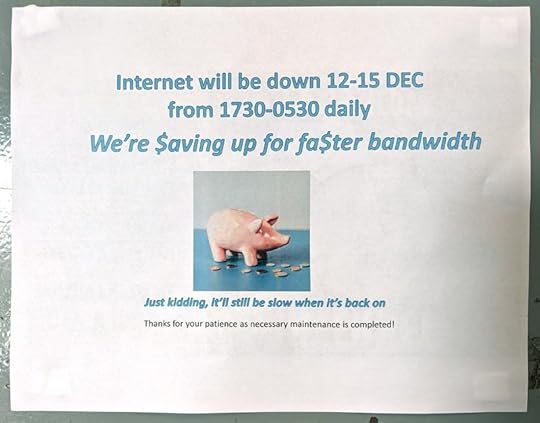

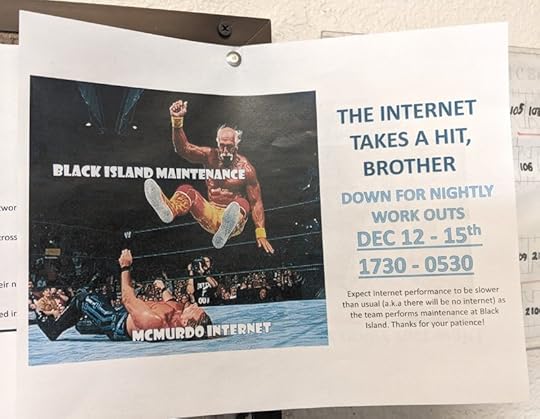

Towards the end of my time on the Ice there was a spell where they needed to shut off the connection overnight, to do some necessary work. Given that most people's workdays extended at least to the shutoff time at 5:30 p.m., this meant essentially no internet for a large portion of the population, and some amusing flyers were posted up to notify everyone of the impending hardship.

Someday, faster, more accessible internet will come to Antarctica. It's more or less unavoidable, as communications technology improves, and everyone's work – especially the scientists' – depends more and more on having a broadband connection at all times. It will make a lot of things more convenient, and will make the long separation from friends and family much easier. But I'm pretty sure that many more people will mourn the upgrade than celebrate it. One can, theoretically, curtail one's internet use whenever one likes, but even before the pandemic it was almost impossible to live this way with the demands of modern life: I know from personal experience that opting out of Facebook alone can have a real detrimental effect on relationships, even with people one sees in the flesh fairly regularly, simply because everyone assumes that is how everyone else communicates. Being in a community where no one has access to assumed channels, and is more or less cut off from the rest of the world in a pocket universe of its own, levels the playing field and brings a certain unity. The planned (and, unarguably, necessary) updating of the physical infrastructure of McMurdo will wipe out a lot of the improvised, make-do-and-mend character of the place; how much would free and easy access to the online world change it in a less tangible way?

I'm sure the genuine Antarctic old-timers would shake their heads at the phone and email connections we have now, and say that no, this has already ruined Antarctica. It's not Antarctica unless your only link to the outside world is a dodgy radio. It's not Antarctica unless you only get mail once a year when the relief ship arrives. Doubtless the shiny new McMurdo will be seen as 'the good old days' by someone, someday, too. Change may happen slower there than elsewhere, but just like the rust on the tins at Cape Evans, it comes eventually, regardless.

For my own part, I'm glad I got to see 'old' McMurdo, such as it was, all plywood and cheap '90s prefab. The update will be much more efficient, and tidy, but yet another generation removed from the raw experience of the old explorers. My generation is probably the last to remember clearly what life was like before ubiquitous broadband; to some extent, Antarctica is a sort of time capsule of that world, just as the huts are a time capsule of Edwardian frontier life. I hope they'll find a way to hang on to the positive aspects of that.

Now, if you'll excuse me, I'm off to waste an hour mindlessly refreshing Twitter ...

If you'd like to learn more about the Black Island facility, there's a lot of good information (and some photos!) here: https://www.southpolestation.com/trivia/90s/blackisland.html

And this Antarctic Sunarticle goes into greater depth on the 2010 upgrade: https://antarcticsun.usap.gov/features/2114/

June 25, 2023

The McMurdo Wave

A certain breed of musical always starts with a 'Happy Village Song.' The real world rarely reflects the tropes of musical theatre, but I found myself reaching for exactly this convention when trying to describe the atmosphere of McMurdo. I know I'm not the only one – it's something that gets commented on by many visitors, and is why so many of its people come back year after year.

The modern theory for this is that there is no WiFi and no cell phone service, so people aren't engrossed in their devices and are forced to speak to each other. It's also possible that the communal dining arrangements, where everyone eats at roughly the same time and you generally end up sharing a large table with strangers, contributes to the social cohesion as well.

But these are not unique to McMurdo. I went to high school in the '90s, when no one had a cell phone and WiFi was a distant dream. We all had lunch in a crowded cafeteria at roughly the same time. The population of my school was about twice McMurdo's, but even in smaller subsets of the student body, the happy village feeling was hard to come by. Why doesn't McMurdo split into factions? Why is the mixing so happy and so widespread?

There must be something else. An obvious factor is probably the Antarctic character, discussed in the last post – the people who self-select for Antarctica just tend to be more open and amenable than your average joe, and this goes a long way towards establishing and perpetuating a happy village. The aforementioned disillusionment with status on The World's terms is also likely involved, as this is a motivator of cliques: you can't limit yourself to associating only with 'the cool kids' if you roll your eyes at the concept of 'cool' and don't care how highly others think of you.

I think there's another factor, though – a very small one that is easy to overlook, but whose ramifications multiply far beyond its tiny self, and that is what I call the McMurdo Wave.

McMurdo Station has trucks and vans, but for the most part people get around on foot. There is a lot of heavy machinery about as well, not least the massive graders which smooth out the soft gravel roads more or less constantly. Humans are small and squishy, and they share the roads with nothing smaller than a Ford pickup, so there needs to be a protocol to make sure accidents don't happen. A pedestrian must make eye contact with a driver, to make sure they're aware of you. But how can you tell you've made eye contact, especially when you might both be wearing goggles? Simple: you wave at each other. Every time you come into proximity with a vehicle, you wave, and they wave back, and you're good.

This very quickly becomes a habit, and you start waving at everyone, regardless of whether they're in a vehicle or not, and they of course wave back because they're in the habit too. And so connections are formed. It's impossible to go around in a self-absorbed little bubble; you must acknowledge and accommodate other people, it's the rules. And once you've smiled and waved at someone, and they've smiled and waved back, you are, to each other, sentient human beings, and not 'just' the cleaner, the dish washer, the heavy machinery driver, the snooty scientist studying who-knows-what about invisible whatevers, doing your thing in isolation. You might recognise the other sometime and, encouraged by the welcome of the wave, start a conversation. It's a remarkably easy ice breaker: I am an old friend to social anxiety, but the convention of the wave was enough to say 'I don't mind if you want to talk with me' and made it much easier to do so. With such glue is a happy village bound.

McMurdo Station exists to serve science. Without the science, the graders would not need to keep the roads in good condition for the trucks, because the trucks are only there to enable the science. The Galley and its cooks and dish washers and cleaners and Frosty Boi repairmen are there to feed the scientists, and those whose work supports the scientists. The scientists – or as they are known on the Ice, 'grantees' – have had to compete fiercely for a handful of grants to come down at all, and are afforded more privileges and freedoms than most of the base population. Such an environment is structured quite obviously with a small group of elites at the top of a massive support pyramid, and as such is prone to rather feudal attitudes. In different ways, I have seen this at work in two very different places: Both Disney and Cambridge attract people who've worked very hard to get to the top of their field, and both are massive machines which exist to allow these people to concentrate on doing what they do best. In both places, the experts exist in a bubble where all that matters is their work, and the essentials just sort of happen; no one thinks twice about the invisible people who keep the machine running.

To my great surprise, this social hierarchy was inverted at McMurdo. There were certainly cool kids amongst the grantees, but if you wanted the real rulers of the roost, you found them in the support staff. Grantees work like hell to get to Antarctica, but are generally only there for one or two seasons before leaving again. They're housed in the 'transient' dorms, so don't get embedded in the company of long-timers. Those who've invested themselves in the running of the base, who come down year after year because the same work always needs doing, have become the Establishment. And, despite their privileges, the grantees know this. They can see how the base runs, and it's obvious that the people who really matter aren't them, around whom the machine is structured, but rather the people who keep the machine running, and without whom there would be no machine at all. The support staff have the real power. Those I met who were at the top of the implicit McMurdo hierarchy never had the sort of job titles that reflected their status. Astrophysicists come and go, but wastewater treatment is forever.

I wonder if the grantees take this attitude back to The World with them. If, getting to know the dish washers at McMurdo, they acknowledge the dish washers at the university cafeteria. I hope so, but I'm not confident ... it's too easy to slip back into old habits when back in the old paradigm. It's a valuable lesson for us all, though. I never really stopped waving at people when I got back home; most of them didn't notice, or ignored me, but it made me feel more connected, and happier in consequence. People say the pandemic has made everyone much friendlier: we're craving social contact, and on the rare occasions we have the opportunity, we make the most of it. Why not try the McMurdo Wave and see what happens?

June 18, 2023

Antarcticans

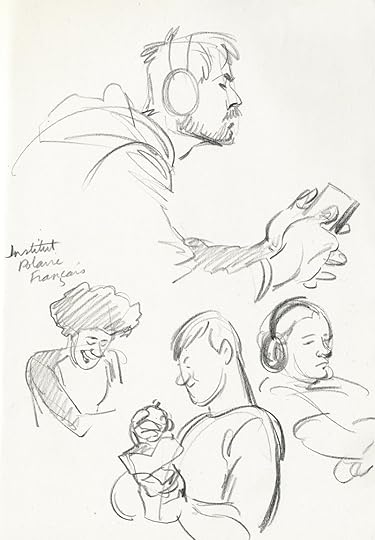

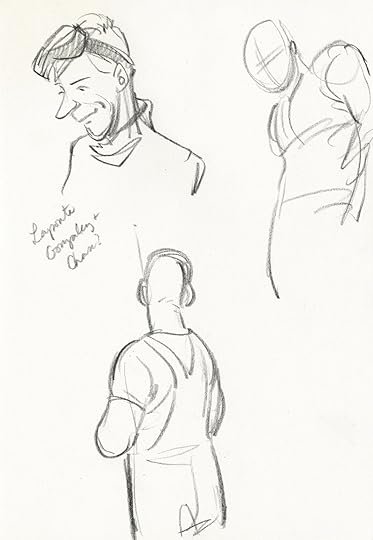

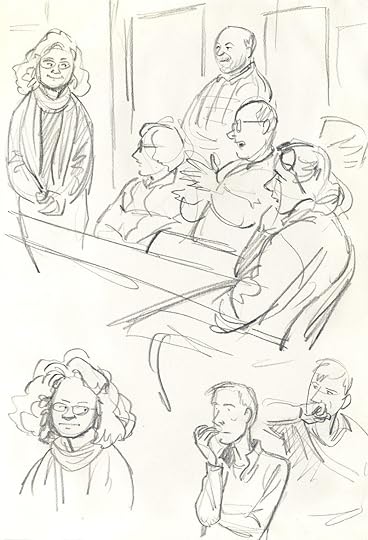

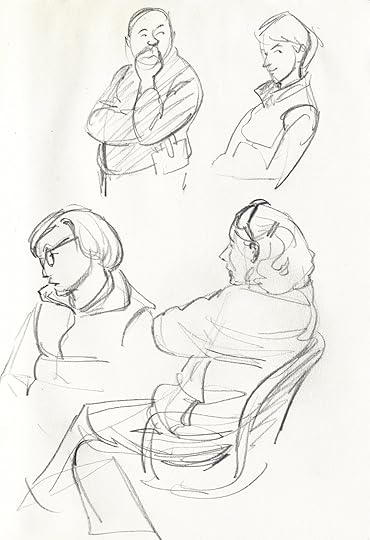

I may not have used my sketchbook as much as I thought I would, with regard to locations, but I did fill a few pages with one of my favourite pastimes back in The World: people sketching.

My biggest anxiety about going to McMurdo was the human factor. Whether it was school or work, a recurring motif in my life is that I do not do well in a big box full of Americans, and that is, almost literally, exactly what McMurdo is. Sure, the continent wants to kill you, and every way of getting to and around it comes with risk of serious accident, but the only thing I was actually afraid of was finding myself in a stressful social situation and not having any recourse to escape. I know how to build a snow cave. I don't know how to deflect the ire of people who've taken a set against me – and, for whatever reason, I tend to rub people in the States the wrong way. When I was shortlisted for the placement, the person handling the admin briefed me about the process and asked me if I had any further questions, and I raised this concern. She responded that, speaking purely from her own experience, she had never felt more comfortable being herself than when she was at McMurdo. Not knowing who 'herself' was, I took this with a grain of salt, but it was an encouraging answer nonetheless.

It turned out that the best thing about McMurdo was, in fact, those very people I had been afraid of. Everyone I met was absolutely splendid. In my first days there, my supervisor joked that if you shake the world, all the best people end up at the bottom; the remainder of my time there proved how right she was. One of the main things that attracted me to the Terra Nova story, and has kept me committed to it for so long, was how wonderful the people were – far outside what I had come to expect from humanity. Warm, genuine, accepting of and attentive to each other, a wide range of personalities and dispositions that nevertheless got on and functioned together as a society, in the face of environmental and emotional extremes ... I needed to know such people were possible, and clung to them as an ideal. It was a wonderful surprise to discover that they would not be out of place amongst their modern counterparts.

Is it because they're scientists, as someone theorised? But they're not – most of the people at McMurdo are support staff, working in the kitchen or waste disposal or shuttle fleet; helping the science happen, yes, but that's not necessarily why they're there, personally. Is it because a harsh environment triggers something in the human psyche to support each other, rather than compete? Maybe, but these people seem like they'd be solid wherever they are, and were like that before going South.

I suspect there is an element of self-selection – something about the sort of person who would want to go to Antarctica correlates with a certain mindset, one that gels extremely well with others who share it, however different they may be in other respects. There is no denying that everyone there is a bit odd. They tend to be types that exist on the fringes back in The World and, like me, may struggle to conform to its values. A few years ago, I came across this adage from an Antarctic veteran: "You go the first time for the adventure. You go the second time to relive the first time. You go the third time because you don't belong anywhere else." Many of them live in remote places, or travel, or do itinerant work when not on the Ice. There is a bit of a running gag in Where'd You Go, Bernadette? that everyone doing a mundane job in Antarctica is a high achiever in something amazing, who left it all behind – and that's not exactly untrue. Perhaps what unites Antarcticans is an awareness of what really matters, when you get right down to it: they've played the game enough to see through it, and are done with it. "Glory? He knew it for a bubble: he had proved himself to himself. He was not worrying about glory. Power? He had power." So Cherry wrote about Wilson in 1948, but many modern Antarcticans might sympathise. When you come out the other side of self-aggrandisement and jockeying for status, and are happy just to be yourself and let others be themselves, you get a happy, harmonious society. Or so it would seem.

At midnight on my last day there, I had a deep conversation with someone I'd only met in passing before, but who was totally down to have a long talk with a random stranger on a footbridge in the middle of the night. I presented her my hypothesis that no one at McMurdo was popular in high school. No, she replied; there may be a handful who were popular in high school ... but they're not popular at McMurdo. Maybe the secret is in there somewhere.

Anyway, I didn't do nearly as much people sketching as I'd have liked, given that the base was populated entirely by Characters, but these (above) are the pages I did manage to get.

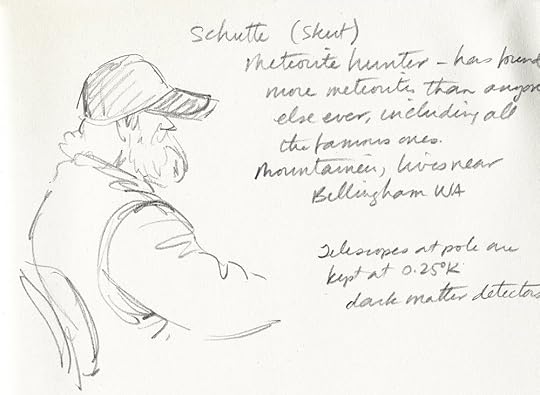

Galley sketch of a celebrity in Antarctic circles, the meteorite hunter John Schutt (Spelled his name wrong in the sketch, sorry).

A lot of construction guys were on the plane to McMurdo and they were good studies for the sturdier sailors on the Terra Nova, a body type I have almost no experience with.

Catrin Thomas, field guide for BAS. I only learned well after actually meeting her, learning from her how to operate a Primus, and parting ways again, that she's a holder of the Polar Medal. When I drew her eating crisps on the plane, she was merely the cool lady with the Wonder Woman slippers.

Two pages of random McMurdites, likely in the Galley:

These last four are from a meeting where team leaders were presenting their projects to some high muckymucks visiting from the NSF. I was only there because my project was allotted a space in the presentation, but the main focus was the massive Thwaites Glacier project, a collaboration between the US Antarctic Program and the British Antarctic Survey to study one of the most unstable regions in Antarctica. They quite rightly took up the whole meeting time, and the privilege of being there meant I learned a lot about the project. My longstanding habit is to draw during meetings, so I captured some of them in my sketchbook while absorbing the science into my head.

Notable characters in my sketches include:

- David Vaughan, heading up the British contingent of the Thwaites team, was quite an engaging and affable guy but had a concentration scowl that puts mine in the shade. I was shocked when I heard he died of cancer earlier this year (2023) – a great loss to BAS, glaciology, and Antarctic science generally.

- When Erin Pettit isn't studying glaciers with an eye to climate change, she's taking girls on wilderness adventures to foster an interest in science and art, as well as self-confidence.

- Britney Schmidt, Queen of Icefin, not only earned my profound respect but has a whole episode of PBS's Terra dedicated to her work developing sub-ice autonomous robots with the aim of exploring Europa. (Seriously, so cool.)

I could go on about Antarctic people, but there's nothing so good as showing you, and luckily I can do just that. PBS sent a small team down in 2018 to do a YouTube series, and one of their episodes is all about the cool people who call McMurdo home. It might make my point better than all my whittering, and is certainly more fun. If you'd like to see more, Werner Herzog's film Encounters at the End of the World is much of the same, but more so. It had been recommended to me several times, but I hadn't managed to get my hands on it until a week before I left, when it turned out a Cambridge friend had a copy and lent it to me. 'I don't know how true it is,' he said, 'but I want it to be.' When I got back, I was happy to confirm to him that it was, indeed, exactly like that. And I miss it so much.

June 11, 2023

Antarctic Meteorology

In my early teens, I wanted to be a meteorologist. Mostly this was because I found weather thrilling – living at the interface of the Great Basin and Rocky Mountains, the weather, when it happened, usually was thrilling – but learning about the principles and patterns of weather systems was fascinating in its own right. Back before the Weather Channel had any programming more mainstream than the local forecast, I would watch it for fun, and in the long unstructured days of summer would follow the development of tropical storms the way others might follow a soap opera. The only downside to this interest (aside from the number of ads for orthopaedic beds) was the regular disappointment, in the winter, that we didn't get the forecast amount of snowfall.

Any intent to pursue this interest professionally petered out within a couple of years. It was one of the many scientific disciplines which was really fun to learn about, but daily practice mostly involved solving complicated equations, and that was not going to work for me. The summer I was 14, I caught the animation bug, and never really looked back. I could not have imagined that my animation career, and where it led me, would bring me to a place where all my meteorological dreams would come true.

It had been proposed that I go for one last visit to Cape Evans on Saturday, December 7th. The day was clear, the forecast promising, and the sea ice still in decent shape. We suited up and packed the sledge to go, but then one of the snowmobiles wouldn't start. When impromptu snowmobile maintenance failed, the fault was called in to the maintenance people, and we went and got an early hot lunch instead of eating a cold late one at our destination. By the time the problem (spark plugs) had been fixed, the weather was obviously turning, and we called off the trip.

That ended up being a very good decision, because that afternoon a surprise storm rolled in, and by the time I was up and about the following morning, more snow had piled up than had been dropped by any other storm in my time there. I got a taste of what the early explorers meant when they wrote that the weather was 'thick as a hedge' – it really was like walking through a leafy hedge, the air so dense with snowflakes that you almost couldn't inhale without sucking them in. Long-timers were commenting that they'd never seen snow pile up like this. And it kept snowing.

On one of my first nights there, I attended a science lecture by one of the meteorology research teams – not the day-to-day, observing-and-forecasting meteorologists, but a group looking at big-picture, model-building stuff. Their presentation was on the difficulty of measuring precipitation in Antarctica: Because it's always windy, not only is it hard to get the snowflakes into the gauge, but it's practically impossible to know what is new precipitation and what is old snow being blown there from perhaps hundreds of miles away. "It's a signal vs. noise problem," as they put it. They showed a number of ingenious automated weather stations they'd designed to calm the wind immediately around the gauge, and how Antarctica had laughed at them and found an easy way around their ingenuity. It's very difficult to forecast precipitation when you can't build up an accurate record of what has fallen in the past, or when you can't cross-check your forecast with what actually did happen. At present, models run entirely on the amount of moisture in the atmosphere (detectable by satellite) and make their best guess, based on that, how much might reach the ground.

Antarctic snow is very light. Melted down, you get only a small fraction of its volume in water. Commuters and teenage weather enthusiasts care about accumulation totals; meteorologists are much more interested in the amount of moisture ('Snow Water Equivalent') and not how deep the snow is. Knowing Antarctica was a desert, I was surprised how many days there were snowflakes falling from the sky, but moisture-wise they were purely decorative. Even the barely-precedented accumulation on 8 December was fluffy like down; you could shuffle your feet through it and feel hardly any resistance. Most of the snow in Antarctica doesn't stay accumulated; either it blows somewhere else, or it evaporates back into the air, a process called sublimation.

The day-to-day observing-and-forecasting meteorologists at McMurdo, who had not been represented in the talk, take regular observations from their many exciting instruments, and twice a day send up a weather balloon to get a picture of what's happening at higher levels. The balloon launch is just an ordinary part of the job for them, but is great fun for non-meteorologists, so they allow people to come down and set it loose at the designated time. These are coordinated with meteorological stations around the world, and therefore are always at 11:30 AM and PM, McMurdo time. I was usually busy for the morning launch, and usually asleep (or trying to be) for the night one. But this Sunday I had nothing going on, and thanks to the prompting of my coordinator, in whose company I was eating brunch, I made it to the meteorologist's eyrie in time to join in the fun.

Back in Olden Times, the hydrogen-filled silk balloon would carry up a little box with instruments that recorded temperature, altitude (via pressure), and wind direction. This was attached to the balloon by a slow match, which would sever the connection after a specified time, and trigger the release of a parachute to ease the instrument box's descent. The box held one end of a long red thread, and the other was held by someone on the ground; when the box fell, the thread could be followed to retrieve the box and its precious data. Many a polar diary tells of following the thread over rocks and pressure ridges until losing it in bad light, or finding that it had broken, but a few instrument boxes were retrieved, and Simpson, the meteorologist, worked their observations into his surprisingly accurate models.

Nowadays, the balloon is latex, filled with helium instead of hydrogen, and the instrument box radios its much wider range of data back to base in real time. As the balloon rises, external air pressure decreases, and its internal pressure expands the balloon's skin until it finally pops. No one tries to retrieve balloon or instrument. I'm not sure how it factors into the Antarctic Treaty's imprecation to pack out what you pack in, but there seems to be an agreement amongst meteorologists around the globe that the small amount of e-waste from twice-daily balloon launches is just regrettable collateral damage against the greater good of accurate models and forecasts.

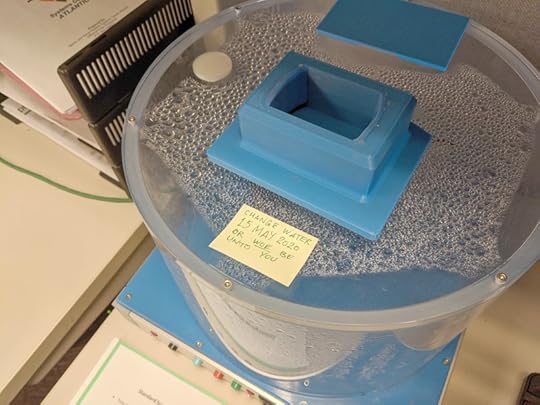

The instrument box, or 'radiosonde', comes sealed tight in plastic. Once unwrapped, it's put into a 100% humidity tank to check the calibration:

Then it's taken down to the launch pad to get hooked up with a balloon. The balloon launch area is essentially a garage on the bottom level of the building that houses the sewage treatment plant, so I got to see that on the way, which was a nice plus. (No, really, it was. It didn't even smell that bad.) Down here are the helium canisters and the very high-tech equipment of a brass stand and a cup-hook screwed into the side of a workbench.

The balloon is hooked up to a canister and filled until it just lifts the brass stand off the tabletop. This indicates exactly the amount of helium that will lift the balloon at a rate of 300 metres per minute.

Waxed twine is then tied very securely around the neck of the balloon, with a loop sticking out. This loop is hooked onto the cup hook, keeping the balloon anchored and leaving both hands free, so they can attach a clip with a spool of plastic line very securely to the neck.

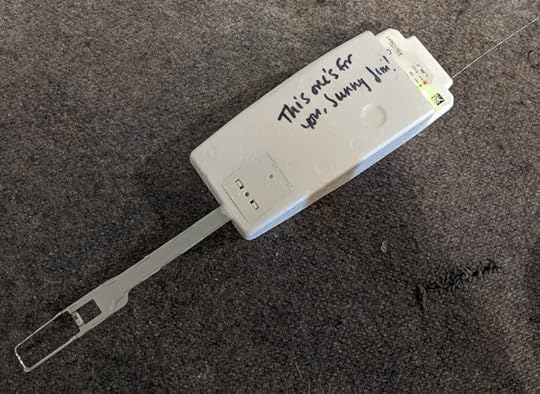

The radiosonde will hang from this line. The instrument itself is is encased in styrofoam, and guest launchers get to write a personal message on it. You know me, one-track mind ...

Then, just before the balloon is released, current conditions on the ground are noted, to give a starting place for the readings that come off the radiosonde. For example, the instrument measures wind speed with an accelerometer, which measures changes in its motion, not an anemometer, with measures the wind speed directly, so the wind speed on the ground has to be subtracted from its data.

Then it was out into the McMurdo snow globe to let the balloon go ...

The meteorologist, who took the picture of me, apologised that the conditions were such that the balloon didn't really show up in the photo, but I assured him that a grey-on-grey photo of launching a weather balloon in a freak record snowstorm was immensely more satisfying to me, personally, than a postcard-perfect snapshot of sending an ivory balloon into a clear blue sky.

(BAS has put together a fun little interactive page about releasing weather balloons, if you'd like to see it done on the other side of Antarctica, in the sunshine, and with a different accent.)

Sunday, December 8th was supposed to be my penultimate day at McMurdo. I was booked onto the flight leaving on the 10th – the return flight of the C-130 arriving on the evening of the 9th – and I knew that I'd be spending most of the 9th in a flurry of packing, cleaning, and goodbyes. The 8th was the last day I could really enjoy, and enjoy it I most certainly did.

As so often happens in Antarctica, the weather forced a change of plans. The dump of snow at the airfields, and the sastrugi carved by the wind afterwards, put them out of action until they could re-pack and re-groom the landing strips. No plane would be landing on the 9th, and therefore no homeward flight departing on the 10th. I was given a few more precious days on the Ice.

McMurdo is a scientific outpost, filled with rational, objective people, but it was funny how often news of my weather delay got the response "They want you to stay!" with no ambiguity about who They might be. So, whoever it was who pulled the strings to send a teenage fantasy's surprise snowstorm: Thank you. It was the finest early Christmas present a girl could ask for.

June 4, 2023

The Chapel of the Snows

The Chapel of the Snows stands out amongst the rough-and-ready prefab huts of McMurdo. Originally constructed during Operation Deep Freeze, when the base was built by the American military in the mid-1950s, it's drawn along the lines of a Midwestern village church, all whitewashed matchboard with discreet Gothic windows and a modest steeple. The first chapel burned down in 1978, to be replaced with a temporary structure which also burned down; the current building is more or less a reconstruction of the 1950s one, was consecrated in 1989, and as of the time of writing, hasn't yet burned down again.

It's definitely the nicest building on base. The Chapel's only rival is the Chalet, a 1970s cabin that currently houses the administrative offices, but the Chalet is rustic where the Chapel is quaint. With its carved and polished wood, decorative wall hangings, and stained glass window, in contrast to the steel-and-formica utilitarianism everywhere else, it feels like a place that has been loved and worn smooth by many hands.

On Sunday mornings the Chapel hosts Christian church services, but it serves a broader purpose to the McMurdo community. Other faith groups use it at other times for their gatherings, and it's also a concert venue, meeting space, and a place of quiet retreat for anyone wishing to escape the hustle of McMurdo life. Because of its central location at the bottom of the main drag, it's also the zero point for giving directions anywhere else. Everyone knows where the Chapel is.

The US military provides a Protestant chaplain on three-month rotation. I happened to meet the incumbent on one of my first days, as he attended the history talk I gave to the hut guides, but I'm still not sure whether he was Methodist or Episcopalian. I was told a Catholic chaplain is provided by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Christchurch, but I don't think there was one in residence during my time, as you will see further on. Other faith groups generally have to get by with a lay leader.

Now, before I continue, I should brief you on my own religious background: I was raised Catholic, and spent my teenage years in a deeply Mormon suburb of Salt Lake City, where my best friend was Evangelical. I started going to an Anglican church in my mid-20s, only a month before hearing the Worst Journey radio play that started all this. It proved a more fruitful spiritual home for me, and the combined forces of modern and Edwardian Anglicanism have guided the reformation of my adult life in tandem. So I come at this with a fair amount of personal knowledge and experience, but also awareness of a broader cross-section of the Christian ecosystem; the sole McMurdo Sunday service I attended therefore became a fascinating study that I have been chewing on ever since.

Because it serves a small gathered congregation from across the denominational spectrum, the Chapel of the Snows is a sort of Big Brother House of American Christianity. I had lived in the US but had been away for several years by this point, and while there is enough on the news to baffle international Christians as to the values of their American brethren, it still wasn’t enough to prepare me for being thrown in the deep end.

Out of a station population of about 900, the congregation numbered around twenty. This in itself was not very surprising, as Sunday is the only day anyone gets to sleep in, and brunch starts around the same time as the service. The choir consisted of whoever could sing confidently enough to lead, which on this Sunday was me and one other lady. Within five minutes it was obvious who the Catholics were, as they were resolutely doing all the gestures in defiance of the corrupting tide of Protestantism, with a conviction that I recognised from my teenage years. They had a spokesman who informed us at the start of the service that in the Catholic Church today was the Feast of Christ the King, and kept us updated on how things would go in the Catholic Church at every turn of the liturgy.

There was a spell in the middle where congregants raised matters to be prayed for. Among the litany of ill and bereaved friends and family who were struggling to afford medical bills was the solicitation to support a prayer vigil at a Texas brewery which was using Satanic imagery on their bottles. The chaplain's sermon hinged on a survey done in the 1950s, which found that the vast majority of Americans identified as Christian, but only a third regularly attended services or had other habits of observance which would signify them as practising; the same survey a few years ago found that those identifying as Christian had fallen to less than half, but the percentage actively practising was virtually identical to the 1950s. I thought this was leading to a point about the decline of hypocrisy, or possibly the resilience of faith despite overwhelming changes in popular culture; instead it was spun to indicate how people were now embarrassed to admit being Christian, that Christianity was such an unsightly label in our godless world that people didn't want to be associated with it. Are you one of the few, the brave, who will stand up and be counted? Ironically, he went from this to a rushed and awkward Eucharist, which looked very much like he was embarrassed to enact one of the central tenets of Christian practice, although being caught between the Catholics and the Evangelicals would have made anyone nervous. By this point, the other half of the choir had had to slip away, so I abused my power by selecting 'Onward Christian Soldiers' for the closing hymn. This was because it was Scott's favourite and was sung at the Polar Party's burial service almost exactly 107 years before, but I thought I could get away with it as it's not out of place for Christ the King. Then the Catholics took themselves off to a side room to pray properly, while the rest of us nattered over the strongest coffee on base and a pile of pastries that greatly overestimated how many McMurdites were not embarrassed to call themselves Christian that Sunday.

There was a lot to unpack from that interesting social hour. My first impression was that, in spite of my efforts to remind myself that the loudest voices do not necessarily speak for the whole, American Christianity was indeed in a very strange place, and that what we could see from across the sea was not as unrepresentative as I'd hoped. My second impression was how desperately they needed to believe that they were a persecuted minority, when in fact they hold the most political power of any faction in the most powerful country in the world. In our immediate context, the political party they’d voted into government had the power of life and death over McMurdo Station; its anti-science disposition and branding of government-sponsored research as wasteful hung like the Sword of Damocles over us all. Most were inclined to believe that if the American presence in Antarctica weren't strategically valuable, the US Antarctic Program would be defunded. It was bemusing that the people gathered in this building couldn't see the obvious paradox.

My third impression was that they had not actually asked any of the heathens in their midst why they might be disinclined to associate with Christianity. If they did so, they might have found that Christianity's image problem has little to do with being “uncool”, and a lot to do with prioritising beer labels over honouring their leper-healing, privilege-flouting founder by working to ensure everyone has access to medical care regardless of income or employment status. Most of my friends have been godless heathens, and I can tell you they have a better grasp of Christian values than a great many Christians I have known.

I am being critical, of course. They were all thoroughly lovely people, who did not withhold their welcome to a stranger, and nor did their welcome extend only as far as the chapel door. For the rest of my time there, these people whose names I barely recalled, who knew they would never see me again after a few weeks, made me feel like one of their own, inviting me to eat with them in the Galley and making warm and friendly small talk in the corridors. It was just what one would hope for in a community. But I could never quite shake the suspicion that I just happened to fall on the right side of a line they had drawn through the universe. For all I know, they had the same misgivings about the sermon that I did, and this may be an unfair assumption. But my lifetime of tiptoeing around us/them divides drawn by exclusive tribes does not get erased easily.

In a funny way, McMurdo Station is not enormously different from a monastic community. There is a lot more sex, to be sure. The food is ample and rich – the vat of prawns at Sunday brunch is anything but abstemious. But it is a small and isolated self-contained society; the selection process is exacting; the work is long and arduous; discomfort is a given; privacy is not; those called to it have eschewed a normal life and, often, dependable income, stability, or even a home and family. It is telling that both the consecrated religious and the Antarctican refer to the sphere occupied by most of humanity as "The World." Out there, where people conduct business, and holiday in the Seychelles, and speculate over who will win Strictly, is The World; here, out of the world, is a different place altogether. Whether lost in contemplative prayer or following the data trail of a neutrino, it's another kind of existence, and in comparison The World just seems like so much chaff. For all they don't turn up to church, the Antarctican almost certainly has greater insight into the religious ideal than a devout churchgoer at home.

Part of the Christian calling (and, indeed, most other religions) is to free oneself from the tawdry preoccupations of The World, and religious buildings are designed to feel set apart. It was paradoxical, then, that in the Chapel, which ought to be set-apart within the set-apart, The World seemed closer than anywhere else. In Antarctica one could easily forget that there was Satanic imagery or breweries in Texas, or indeed that there even was a Texas, but here the threads back to The World were stronger and more plentiful than anywhere else. The relationships between congregants and those far away, as well as tangible tokens of civilisation – the Gothic details, the Navy flags, the hymnals and kneelers like any other church anywhere – all knitted the Chapel of the Snows more inextricably to The World than anywhere else at McMurdo. What did the motifs of wheat and grapes have to do with anything, here?

Before I left Cambridge, someone in the church group I frequented had asked me if there was a church at McMurdo. Yes, I replied, though why one would want to sit in a little wooden box instead of the vast cathedral of Creation was beyond me. “It's probably warmer,” was his response, and I had to admit he had a point. But the image of a puny shed in the midst of almost incomprehensible grandeur stuck with me as symbolic of the pettiness of human religious constructs in the face of the Divine. “Human kind cannot bear very much reality,” wrote T.S. Eliot, and when faced with the mild-melting enormity of the Ultimate Reality, human kind must shrink it down or cut it up into small enough pieces to digest. The priest in his chapel, the marine biologist in her tank, the artist in the historic hut, the glaciologist with her cores, the pilot in his sky, the wastewater supervisor with her bacterial cultures, the chef in the kitchen, the videographer in his ice cave, the astrophysicist with her antennae, the meteorologist up his tower – they are all working on their tiny tiny piece of the whole, more than enough for one or even several to handle, but only an infinitesimal fraction of What Is. The trick is not to fall under the illusion that the piece which fills the whole of your field of vision is, in any way, all that matters. How they fit together gets you closer to the point, and leaving any bit out pulls you further away. This is the problem with Us and Them. Exclusivity is the enemy of wisdom.

The future of the Chapel of the Snows is doubtful. Not, as some might want to believe, because of insidious secularism, but because the grand plan for a renovated McMurdo is to include a chapel in the central building that will comprise the Galley, administration, and some dorms, like a prayer room at an airport. This is not a popular plan. Very few McMurdites would ever consider worshiping in it as a chapel, but it is a hub of McMurdo life, and practically the only building that isn't Work in some way. Its entanglement with The World is a comforting shred of familiarity. Having a space set aside to be different is valuable no matter what your religious convictions are, and the Chapel is an important building to nearly everyone in their own way. But the NSF works in mysterious ways, and a budget spreadsheet is more persuasive than a sociologist, so the little shack in the midst of a cathedral may not be long for the little world outside The World. McMurdo will be a poorer place for loss of it.

May 28, 2023

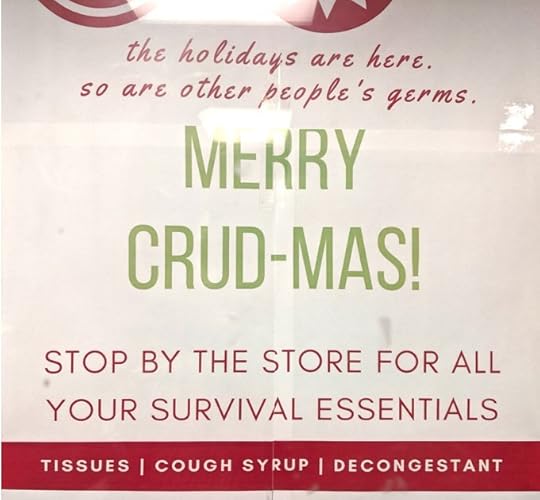

The Crud

A much-belated return to the Antarctic Blog. This was originally written for my Patreon in December, 2020. This post contains frank details of an upper respiratory viral infection. If you are grossed out by such things, or if you want to look crème pâtissiere in the face again, please click away now.

McMurdo has a secret.

A secret they don't want you to know.

A secret that is kept out of the documentaries and the media reports and the funny little personal videos about life at the bottom of the world.

There is a beast that lurks in the corridors, passes unseen through the Galley, can follow you out to a field camp, or come find you safe and warm in your dorm. You won't know it's close until it's got you. People will swear by magic spells, potions, and rituals that keep it away, or alleviate the suffering, but there is no stopping fate, and fate goes by the name of ...

THE CRUD.

According to the multi-year veteran dish-washer I met over dinner one evening, The Crud is a cold virus that's endemic to McMurdo. It gets passed from cohort to cohort, year on year, and has evolved into its own thing. The CDC even sent someone to investigate it once.

I don't know how much of that is true, but it is certainly impossible to escape the presence of The Crud. It's required to wash one's hands before entering the Galley, and there is a bottle of hand sanitiser on every table. The McMurdo shop, which is just around the corner in the same building as the Galley, does brisk business selling pharmaceuticals to those who've been afflicted – in fact, along with souvenirs, beer, and cartons of UHT milk, decongestants seem to be their main line of business. Everyone must show proof of having the most recent flu vaccine before they can get on the plane to Antarctica, but there is no vaccine against The Crud, so it's a dependable return on investment.

Looking back on The Crud from the other side of 2020 is amusing. On one hand, ubiquitous hand washing and alcohol gel are no longer quirks of McMurdo but part of eveyone's life. On the other, it's a little comical that there was such paranoia in the Galley, but nowhere else. I'm pretty sure I caught The Crud at a science lecture in the library, where upwards of 50 people were crammed together in a smallish, poorly-ventilated room for over an hour, with nary a sanitiser pump to be seen – or a face mask, which would probably have been more effective.

I can confirm that it was not like any other cold I'd ever had. I am no stranger to the seasonal rhinovirus, and have made a lifelong study of its variations. The Crud started as colds usually do, with a tiny but persistent irritation high up in my nasal passages and a general sense of inflammation. However, instead of taking the usual track through sneezing, running, stuffiness, and a lingering cough, it turned quickly into a head full of crème pâtissiere and stayed there, unmoving, for days.

Being a regular sufferer, I have devised a strategy that gets me through the average cold: At first sign, slam it with a proven cocktail of herbs and vitamins, drink as much water as you can swallow, and look after your sleep. If that fails, sleep as much as possible in the first 36 hours, be assiduous with decongestants and anti-inflammatory nasal spray, and suck down hot mulled ginger lemonade until it goes away. Once upon a time I believed in medicating and soldiering through, which gave me ten days of a bad cold and a month of cough. With the new strategy, which I like to call Looking After Myself, I am usually over it in a week and sometimes don't even get a cough at all.

I have a small anti-cold kit in my travelling toiletries bag – one never knows! – but the preventatives were useless in this case, and the decongestants not much better. I spent an entire day in bed, early on, but all that achieved was wasting one of my precious limited Antarctic days. The only thing that seemed to do any good at all was the anti-inflammatory spray, which opened enough of a pathway through the crème pâtissiere that I didn't have to breathe through my mouth all the time.

Sometimes you get an untreatable cold, and just have to make the best of it. This was by no means the most miserable one I'd had, and the lack of a runny nose was a notable relief. But I did miss having access to a kitchen: Normally I'd bung the lemon, ginger, honey and spices in a giant teapot and simmer it on the warmer until mulled into a soup to make a medieval chef weep, but the best I could manage in the McMurdo galley was to put some cinnamon powder in a mug of apple juice and nuke it. It was comforting, and cleared me slightly for a few minutes after drinking it, but wasn't nearly as effective.

The most bothersome thing about The Crud was the fatigue. I had been going pretty hard for a few weeks so I definitely needed to catch up on my rest, but I never seemed to be able to get enough. Part of this was not getting proper sleep when I did lie down, on account of the crème pâtissiere threatening to smother me. I didn't have the brain fog that comes with illness, but the sleep deprivation began to make up for it. On top of that was the frustration of seeing my precious Antarctic time slipping away and not having the wherewithal to take hold of it. Day after day I sorted photos and caught up on my journal and watched the sun wheel away my remaining hours. Another day of taking it easy should see me right ... maybe one more ... must be almost over it now ...