Thomas W. Gilbert's Blog

June 19, 2024

OLD-FASHIONED BASEBALL -- NO UMPIRES CALLING BALLS AND STRIKES

BASEBALL IN THE GOOD OLD DAYS BEFORE THE STRIKE ZONE

Baseball carries the weight of almost two centuries of tradition. And because it has been around so much longer than any other American team sport, baseball seems to have a particular resistance to innovation. You can already feel the swelling opposition to MLB’s plan to introduce an automated strike zone detection system, which would take away the job of calling balls and strikes from a human being and give it to a machine. This would turn the home plate umpire from one of the most important figures on the field into a passive relayer of information. The only plays he would “call” would be fair/foul balls in the infield and plays at the plate.

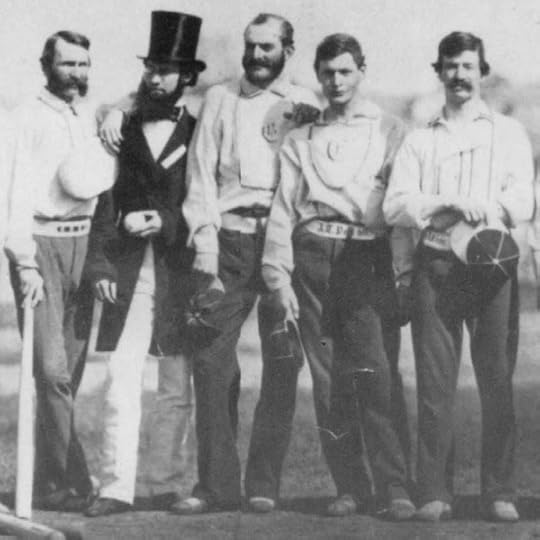

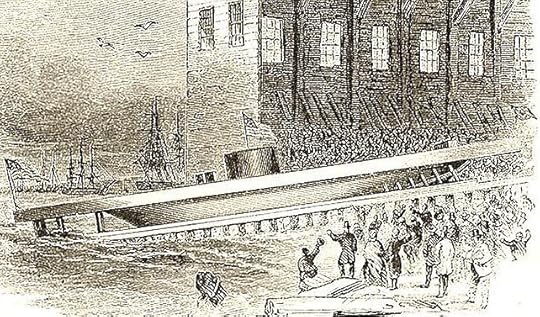

Nobody would try to argue that this is not something new, but in one very specific way, it isn’t. We do not know how old the game of baseball is, but it was definitely played for decades or even centuries without called balls and strikes and without an umpire standing behind home plate. See the illustration above from the year 1866. That is the umpire, standing off to the right and wearing a hat and coat.

February 12, 2023

Talking Baseball History with ChatGPT

Me: Explain how baseball originated.

ChatGPT: Baseball originated in the United States in the late 18th century. It is believed to have evolved from a game called rounders, which was played in England. The modern version of baseball as we know it today began to take shape in the early 19th century, with the first set of rules and regulations being established in 1845. The game quickly grew in popularity and by the late 19th century, it had become the national pastime in the United States.

Me: The first sentence is pure conjecture. The second is untrue. The third contains a falsehood -- the first set of rules and regulations was not established in 1845.

ChatGPT: You are correct that the first sentence is conjecture, and the second sentence is not entirely accurate. The origins of baseball are not well-documented, and it is not certain that the game evolved directly from rounders. The third sentence is also incorrect, the first official set of rules and regulations for baseball were established by Alexander Cartwright and the Knickerbocker Club in 1846. I apologize for any confusion caused by my previous response.

Me:We know that there were older written rules before the Knickerbockers; the Knickerbocker rules are merely the oldest that survive. The role of Alexander Cartwright is exaggerated and possibly trivial. There is absolutely no evidence that baseball evolved from rounders.

ChatGPT: You are correct, the game of baseball has evolved over time and the set of rules established by the Knickerbocker Club in 1846 is not the first set of written rules for the game. However, it is widely considered to be the first recorded set of formalized rules for the modern version of baseball. Additionally, Alexander Cartwright is credited with helping to establish many of the key elements of the modern game, such as the diamond-shaped infield and the three-strike rule. However, the exact origins of baseball and the extent of Cartwright's role in its development are still debated by historians. It is also true that there is no definitive evidence that baseball evolved directly from rounders or any other specific British game.

Me: Who was Jim Creighton?

ChatGPT: Jim Creighton was an early baseball player in the United States, widely considered to be one of the best players of his era. He was born in 1841 and grew up in Brooklyn, New York, where he began playing baseball as a young man. He played for several amateur and semi-professional teams in the New York area, and was known for his strong hitting and pitching abilities. Creighton died in 1862 at the age of 21, but his contributions to the sport helped to establish baseball's popularity in the United States and laid the groundwork for

the professionalization of the game in the following decades.

Me: He did not grow up in Brooklyn.

ChatGPT: My apologies, you are correct. The information I provided about Jim Creighton's upbringing is incorrect. The details of his early life and upbringing are not well-documented, and the specific location where he grew up is not known. I apologize for any confusion caused by my previous response.

Me: It is known that he grew up in lower Manhattan in New York City

ChatGPT: Thank you for correcting my previous statement. Yes, Jim Creighton grew up in Lower Manhattan, New York City. I appreciate the additional information.

Me: Creighton did not play for "semi-professional teams" because no such teams existed in his time

ChatGPT: Thank you for correcting my previous statement. You are correct, the concept of "semi-professional" teams did not exist in the time of Jim Creighton, as professional baseball was not yet established. Creighton played for amateur teams in the New York area, and he was widely considered to be one of the best players of his era. I apologize for any confusion caused by my previous response.

April 4, 2022

PRINTER, PLAYER, TURNCOAT, TRAITOR

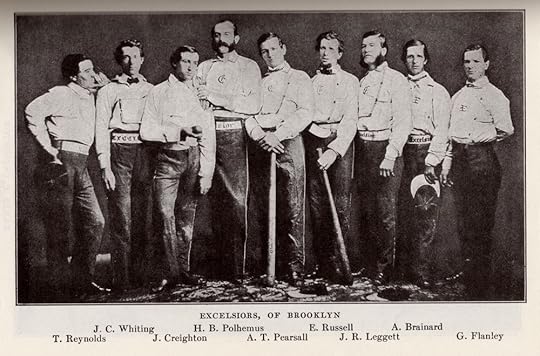

A. T. Pearsall of the Excelsiors (second from right): first baseman, physician, and friend of Alexander Babcock

Counting both sides, a total of more than three million soldiers fought in the Civil War. Alexander Babcock was two of them.

Alexander Babcock was the brother of William Babcock, a founding member of the Atlantic baseball club of Brooklyn, baseball’s first dynasty and the winningest club of the pre-professional era. In the 1850s both men worked as engravers, lived in Brooklyn, and played for the Atlantics. Like thousands of their fellow baseball players, when the Civil War broke out in 1861, they joined the Union army.

In the fall of 1862, after he had finished his service with a New York regiment, Alexander Babcock joined a group of friends including A. T. Pearsall, star first baseman of another Brooklyn baseball club, the Excelsiors, snuck down to Richmond, Virginia, and offered his services to the Confederacy. A practicing physician, Pearsall spent much of the war as a military surgeon in the (Confederate) 9th Kentucky Cavalry. Babcock helped print currency in Richmond before putting down his burin, picking up a Colt, and joining the infamous cavalry unit Mosby’s Rangers. (That’s another story — and a good one).

What led Babcock and Pearsall to switch sides? They never said. But there is an over-sized clue in their timing. On June 19, 1862 President Abraham Lincoln signed the Territorial Abolition Act, which outlawed slavery in all territories outside the control of any state, i.e., much of the West. On July 22nd the other shoe dropped; Lincoln read the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet. From that moment onward Lincoln was publicly committed to abolishing slavery throughout the United States; it was only a matter of how and how soon. Before and during the Civil War, many New Yorkers and other Northerners were torn between loyalty to the Union and ideological support of slavery. (It is widely forgotten that slavery had ended only a generation earlier in New York state). Pro-slavery and even pro-Confederate sentiment ran high in New York City, where in 1861 Mayor Fernando Wood threatened that the city would secede from the Union rather than cooperate with the Northern war effort. For men like Pearsall and Babcock, preservation of the Union was a worthy cause; abolition of slavery was not.

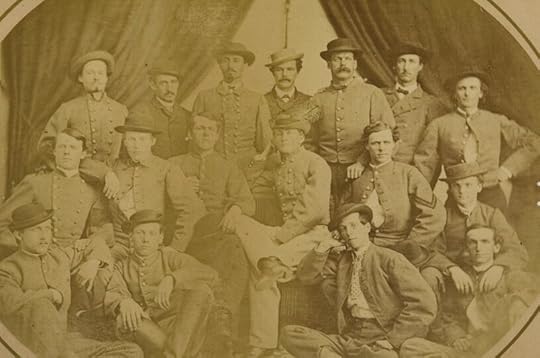

Alexander Babcock (back row, third from right), posing with fellow members of the notorious irregular cavalry unit Mosby’s Rangers, who frightened even their own commander, General Robert E. Lee. Colonel John S. Mosby himself is seated in the center with legs crossed.

Babcock’s military career raises an interesting legal question. Was he a traitor? By the nature of civil war itself, treason was a thorny issue in the postwar years. Immediately after the war President Lincoln issued individual pardons for treason to various ex-Confederates. The legal consensus then and now is that accepting a pardon carries an implicit acknowledgement of guilt. Certainly, there are many examples of Americans refusing pardons on the grounds that they are innocent. In 1867 former CSA President Jefferson Davis was about to stand trial on treason charges. His lawyers were preparing to argue that when his home state of Mississippi left the Union, he was no longer a citizen of the United States. This, of course, begs the question that was the casus belli. If secession was legal and the Confederacy was a legitimate independent state, then a citizen of that state could not be committing treason merely by serving in its army. A person cannot be guilty of betraying someone else’s country. A possible point in favor of Davis’s argument is the fact that the U.S. government treated captured Confederate soldiers as POWs, not as criminals. Perhaps partly out of fear that trying Davis might establish awkward precedents on the legality of secession, President Andrew Johnson issued a blanket pardon for the crime of treason that covered all former Confederate soldiers and officials. The Jefferson Davis trial never took place. Of course, it is hard to see how Davis’s hypothetical legal defense would have applied to Alexander Babcock, who was born and raised in New Jersey.

After the war Babcock remained in Richmond, started a successful ice business, and played baseball with a local club into the late 1860s. A. T. Pearsall married a nurse from Alabama and settled in her hometown after the war. He helped found one of the first baseball clubs in that state. In 1878, however, the divorced Pearsall returned to the Binghamton area in upstate New York, where his family came from. When he died there in 1903 his obituaries said nothing about his military service or his time in the South.

March 28, 2022

Hired Man: The Story of Bad Patsy Dockney

An 1860s gold pocket watch that was not stolen by Patsy Dockney

In May of 1866 newspaper publisher Colonel Thomas Fitzgerald surprised the baseball world by resigning as president of the Athletics. Cofounded by Fitzgerald, the Athletics were the most successful baseball club in Philadelphia and a contender for the national championship. Readers of his newspaper, the City Item, soon learned why Fitzgerald had quit – he disapproved of the Athletics’ use of “hired men,” or mercenaries.

Nowadays, of course, the best baseball clubs are professional, and their players are all “hired men.” But baseball in 1866 was still an amateur sport. The first professional league opened five years later, in 1871. The term amateur carried cultural as well as regulatory meanings. Baseball club members were supposed to be bound to each other by mutual social obligation, not by economic considerations. Baseball’s national governing body strictly forbade clubs from paying players. For one club to poach a player from another club was considered unethical, even if done in a way that was technically legal. Clubs were also expected to enforce minimum standards of behavior and respectability. As the sport spread outward from New York City and Brooklyn (then independent cities) the stakes increased and the national baseball championship became more competitive. More and more clubs quietly recruited players based on athletic performance alone. Race remained a dealbreaker – even the best African American players were excluded from organized baseball until the late 19th century, well into the professional era -- but class barriers weakened.

Philadelphia publisher and baseball man Colonel Thomas Fitzgerald

The City Item accused Colonel Fitzgerald’s fellow Athletics officers of paying four players $20 a week. Under a cartoon caricature of a hired man appear the words, “They generally come from New York, with only one or two exceptions, and are about the hardest set we ever saw.” It did not name names, but thanks to the hint, the identities of two of the filthy four are obvious.

They are Patsy Dockney from Hoboken, New Jersey (across the Hudson River from New York City) and Lipman Pike from Brooklyn, New York. The brawling, hard-drinking Dockney and Pike are a good fit for “the hardest set we ever saw.” As Fitzgerald wrote, “The officers of the Athletic Club have done much to bring the game into contempt by employing men to play in their nine who have been repeatedly arrested and confined in the station house...on the charge of drunkenness and rioting. There was a time when a player would have been expelled from the club for drunkenness and rioting, but that day seems to have passed.” Dockney and Pike both left Philadelphia by the end of the year.

Until the very end of the Amateur Era the clear letter of baseball law prohibited clubs from paying or compensating players in any form, but as applied in the real world the prohibition was a bit more elastic. Some forms of player compensation came to be regarded as acceptable; others were not. Influential journalist and baseball rules committee member Henry Chadwick drew a partly class-based distinction between “hired men” – in it solely for the money -- and “those whose loss of time and necessary expenses are very properly paid.” “All clubs,” he wrote, “who have first class players in their nines whose positions in life are not surrounded with pecuniary advantages, or who are not, in fact, well off in the world, of course take care that their players are not sufferers from sacrificing their time to sustain the playing reputation of the club of which they are prominent players. But this style of thing is...very different from ‘hiring men,’ or paying them so much a week for their services, just as ‘professional’ cricketers are paid.” (This sounds almost as if it were tailored to rationalize the Brooklyn Excelsiors’ treatment of pitching great James Creighton. The avowedly amateur Excelsiors brought the teenage Creighton and his family from a New York City slum to suburban Brooklyn, provided them with an expensive house, and arranged no-show government jobs for Creighton and his father.)

One look at their careers, however, makes it obvious that Patsy Dockney and Lipman Pike were out and out mercenaries. Dockney played for the New York Gothams in 1864 and 1865; the Athletics in 1866; the Eurekas of Newark, New Jersey in 1867; and both the Cincinnati Buckeyes and the New York Mutuals in 1868. Lipman Pike came up through Brooklyn junior clubs under the control of the Atlantics, where he was playing when he jumped to the Philadelphia Athletics for the 1866 season. He went on to play in New York, Baltimore, Hartford, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Providence.

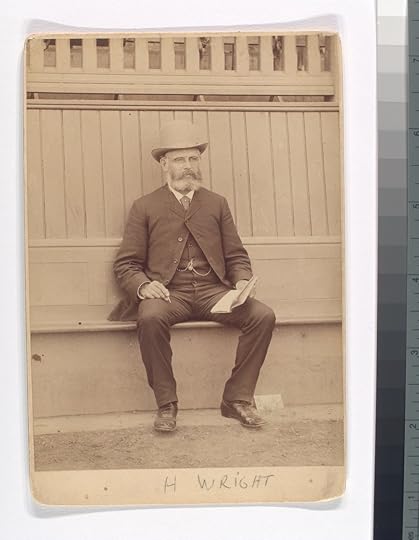

Harry Wright

Dockney was a power-hitting catcher who had been discovered on a New Jersey sandlot by Harry Wright, who was then a member of the Gothams. Dockney was exceptional among Amateur Era ballplayers in several respects: he was born in Ireland, emigrating to the U.S. as a four-year-old with his family; he was Catholic; and he had a working-class upbringing. He also drank too much and got into frequent trouble with the law. In April 1867, while a member of the Quaker City club, Dockney was charged with stealing a pocket watch. He was acquitted, but he seems to have had a special affection for timepieces; he was repeatedly arrested for similar crimes. In April of 1868 he was in Cincinnati, playing for the Buckeyes, when a newspaper reported that a certain Frank Robinson had been stabbed in the chest during a melee in a saloon at 256 Central Avenue. The real story soon came out. Frank Robinson was the anachronistically hilarious false name that Dockney gave the Cincinnati police; and the saloon was in fact a bordello. Embellished over the years and exaggerated beyond all recognition by sportswriters, this sordid episode was once a standard part of baseball lore. There are many versions, but the following 1919 newspaper story is typical:

“In 1870 the Athletics went to St. Louis to play a series with the star club of that city. On the night before the first game Dockney and some of his associates became involved in a fight in a St. Louis café and when it was all over it was found that Dockney had been slashed with a butcher knife across the chest. The wound ran from one shoulder to the other and blood streamed in torrents. Dockney, unconscious, was picked up, placed into an ambulance and hurried to the hospital. There physicians took something like fifty stitches in his chest and were compelled to place strips of plaster across to assist in holding all the torn parts together…[The next day, Dockney] escaped from the hospital and reported at the baseball grounds “ready for duty.”…Dockney caught the game that day without the use of a glove, mask or chest protector, which were practically unknown in that era…He endured until the last man was out and then collapsed utterly.”

It is hard to know where to start fact-checking this one. The actual incident took place in Cincinnati in 1868; a bordello bears little resemblance to a café; and Dockney was not a member of the Athletics at the time. Even though the story greatly exaggerates the size of Dockney’s chest wound – an 1871 prison record lists his principal scars but fails to mention any on his chest – whatever really happened to him kept him out of baseball action for a good three months.

Patsy Dockney resigned from the Buckeyes in 1868, moving on to the Mutuals, then several other clubs in 1869 and 1870. In 1871, at 26, he was convicted of larceny and sentenced to three and a half years in New York state prison. He was pardoned by the governor after serving three years. He spent the next several years playing as a paid ringer for amateur clubs in the New York City area, as well as working as a “fish butcher” in New York’s Washington Market. We do not know when and where he died; he last appears in the U.S. Census at age 32 living in Manhattan with wife Flora, 21, and a four-year-old son named Alexander.

Prison records contain one last illuminating detail about Patsy Dockney. His 1871 Sing-Sing prison records note that he had two crude blue dots on his left forearm and three more on his left hand. These are Victorian prison tats. Made by prisoners, they signify prison sentences. Sure enough, Patsy Dockney’s 1871 prison intake document states that he had served five previous jail terms.

March 4, 2022

MLB's FIRST LATINO PLAYER WAS.....COLOMBIAN?

Luis “Jud” “Manuel” “Miguel” “MIchael” Joaquin Bonifacio Castro Vasquez

Who was the first MLB player born in a Spanish-speaking country?

For a long time, the answer to this question has depended on who you ask. Was it Esteban Bellan or any of the other Cubans who played in the National Association — the first U.S. professional baseball league, which lasted from 1871 to 1875? Not according to MLB, which decided a long time ago that the NA didn’t count as a major league.

MLB is the majors — but does it get to decide retroactively what historical leagues are or aren’t “major league”?

I guess so.

MLB says that the first major leaguer born in a Spanish-speaking country was Luis Castro. This is surprising. Not only was Castro from Colombia — not from Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Venezuela or any other country that would make sense — but he was from Medellin, which is well outside the small section of Colombia that plays baseball, the Caribbean coast, near Cartagena and Baranquilla. (This is the region that produced Edgar Renteria, Gio Urshela and Jose Quintana ). Luis Castro starred at Manhattan College in New York before playing professionally. The peak of his career came in 1902, when he was 25, when he played second base for the Philadelphia Athletics, who were in the American League — which was definitely a major league.

Another twist in the Luis Castro story is that historians have disagreed about where he was actually born. Some say he was born in Colombia and brought to New York City by his Colombian father; others say that he was born in the U.S.

The eccentric Castro himself told conflicting stories about his life and his nationality. Some official documents list his birthplace as Medellin, Colombia. Others say he was born in New York City. For whatever reason, he told friends and teammates at various times that he was Venezuelan, Cuban, even Spanish. Until about a week ago, we were not even sure of his real name, which baseball references give as Luis Manuel Castro, Luis Michael Castro, and other variations. He was nicknamed “Jud” by his professional teammates. Of course, we don’t know why.

Now, however, we have proof of where he was born.

Castro was born on November 25, 1876, in Medellin, Colombia. He was baptized in May of 1877; this is confirmed by a recently discovered church record that gives his full name as Luis Joaquin Bonifacio Castro Vasquez. His father, a banker named Nestor Castro, brought him to the U.S. when he was eight. He grew up in New York City, where he learned baseball and attended Catholic schools. He died and was buried in Queens in New York City in 1941. Last summer MLB and the Society for American Baseball Research honored him by placing a marker on his previously unmarked grave.

March 3, 2022

JOE LEGGETT: GREAT BASEBALL PLAYER, TERRIBLE HUMAN BEING

Mr. Leggett was trusted too soon after his operation in the fire department. --Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 22, 1877

In pre-Civil War baseball, playing the position of catcher required a degree of physical courage that we can barely conceive of. Catchers had no face masks or other equipment. The only thing preventing a pitched ball from skipping away from the field, allowing runners to circle the bases, was the catcher’s unpadded and unprotected body. Game accounts of the 1850s rarely tell of a pitcher being taken out of a game; catchers, however, were often removed with head or hand injuries. When there were two strikes, an aggressive catcher would move up behind the batter and spread out his bare hands, risking a fractured nose or cheek bone in order to catch a foul tip. Joseph Leggett, star catcher of the Excelsiors of Brooklyn, was very good at this. In his 1868 baseball instructional Henry Chadwick referred to this technique as “taking balls sharp off the bat, a la Joe Leggett…”

Joseph Bowne Leggett was born in Saratoga County in upstate New York in 1828. The Leggetts were an old Quaker family whose ancestors had settled in Queens in the late 17th century. Leggett moved to Brooklyn as a young man and worked in the family wholesale grocery business with an uncle and several cousins. He was a volunteer fireman with the baseball-playing Pacific Engine Company #14 on Love Lane in Brooklyn Heights. Leggett, his cousin James K. Leggett and another relative, Isaac Leggett, all served terms as foreman. (James K. Leggett later became president of the Brooklyn Fire Department). In 1861, when the Excelsiors were inactive because of the Civil War, two of Joseph Leggett’s teammates, Henry Polhemus and George Flanley, played for the Pacific #14 baseball team. In 1867 the nearly 40-year-old Joseph Leggett married the 20-year-old Alice Marks; they had three children.

Leggett joined the Excelsiors in 1857 and was their best player until the arrival of pitching phenom James Creighton three years later. It is difficult to evaluate the batting statistics of Leggett’s day, but the Excelsiors kept a silver ball on which they engraved the name of their top batter for each season. In 1860 it was Joe Leggett. That was the year in which the Excelsiors made their famous road trips to eastern cities. One of their stops was Baltimore, where Leggett and Polhemus had earlier helped a business associate, grocer George Beam, found that city’s first baseball club, which was also called the Excelsiors. On July 22 the Brooklyn Excelsiors demolished the Baltimore Excelsiors, 51-6. Local fans were awed by the sight of Baltimore players swinging at Creighton fastballs after they were already in Leggett’s hands, and Leggett’s “daring, almost reckless” play behind the plate.

Leggett also acted as a combination pitching coach, trainer and talent scout for the Excelsiors. It makes sense that a catcher would serve this function, because pitchers of the time could only throw as hard and with as much movement as their gloveless catchers could handle. Leggett developed and trained not only the great James Creighton, whom he taught to lift weights, but also two of the other great pitchers of the day, Asa Brainard and Candy Cummings. In 1866 Leggett saw the teenage Cummings pitch and persuaded the boy’s parents to let him join the Excelsiors. Older than most of his teammates, Joe Leggett was looked upon as a father figure, who, in modern baseball terminology, policed the Excelsiors clubhouse. Well respected in baseball generally, he served as vice president of the National Association of Base Ball Players in 1862. The only wart on his baseball portrait was his odd hypersensitivity to crowds, a quality that contributed to the notorious forfeited championship game between the Excelsiors and Atlantics in 1860.

As fine a ballplayer and as solid a teammate as he may have been, Leggett was a deeply flawed human being. Both during and after his playing career, Leggett exploited his fame and the connections he made as an athlete to make a living. He held a string of jobs in institutions connected to the powerful men behind the Excelsiors. But he could not keep his hand out of the till. It may be that Leggett had a gambling problem. An underlying vice would help explain why Leggett’s transgressions so often met with sympathy and why his friends gave him one second chance after another. It is also possible, of course, that he was simply dishonest. In 1859 Leggett worked at the Brooklyn’s Mercantile Library Association, a favorite charity of the wealthy, where he was caught trying to rig an officers’ election. During the Civil War Leggett served as a quartermaster in the 13th New York State Militia under fellow Excelsior Colonel John Woodward. In 1869 Leggett was appointed treasurer of the Widows and Orphans Fund of the Brooklyn Fire Department. Three years later, he failed to deposit the nearly $3,000 proceeds from a charity ball into the fund. An official investigation later found that his boss, a fellow ex-firefighter from Engine Company #14, had dropped the matter despite Leggett having reneged on a promise to pay the money back. Forced to resign, Leggett found a clerical position with the Brooklyn Police Department Excise Bureau, which issued liquor licenses. In 1877 $1000 in license fees went missing; Leggett disappeared and was fired. On January 4, 1878, the Brooklyn Union Argus reported the following.

Joe Leggett, the runaway clerk of the Excise Bureau, is still wanted at Police Headquarters. His whereabouts is a mystery. In consequence of his sudden and improvident departure his wife was obligated a few days before New Year’s to give up her residence in Monroe Street, and she and her children are now boarding with friends…Leggett’s best friends are loud in their denunciation of his misconduct, and loud in their praise of his wife’s fortitude under crushing trial.

This time, Joseph Leggett legged it. As far as we know he left New York never to return, apparently living the rest of his life under a false name. Family genealogical records have it that he died near Galveston, Texas in 1894, by one account in prison. There are indications that the fugitive Leggett may have maintained some form of communication with his abandoned wife or with members of his family. Alice Leggett and her children were taken in by Joseph Leggett’s brother. In 1899 Alice applied for and was granted a Civil War widow’s pension; this raises the question of how she knew that her husband had died and how she was able to document his death to the government. Leggett’s new name and location may have been an open secret in the New York baseball world. In 1889 Chadwick reminisced in print about the great amateur Excelsiors. “Ed Russell, Asa Brainard and Tom Reynolds are dead and gone,” he wrote, “Pearsall is a doctor in the South [sic: by then he had moved back home to upstate New York]…Harry Polhemus is one of Brooklyn’s society men and a millionaire; John Whiting is in business in this city, and his brother Charley also, I believe, while Joe Leggett is—well, I will be silent for old times’ sake.”*

*Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 15, 1889, p.4

July 2, 2021

Why are Major League Hitters Striking Out So Much -- An Analytics-free Opinion

Consider this scenario:

You are MLB and you want to standardize the strike zone, which for more than a 100 years has varied from era to era and from umpire to umpire (it has also changed depending on the score, the length of a particular game or even who is batting). You deploy a new technology that precisely measures umpires’ strike zone accuracy. You use it to grade umps, which incentivizes them to conform; it takes a few seasons, but eventually it starts to work.

The strike zone that you programmed into the video technology is the one in the rulebook — it is the width of home plate and it extends from the bottom of the batter’s knees to the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants.

The problem is that, as every fan over 20 knows, the strike zone as called in MLB games had evolved a considerable distance from one(s) in the rulebook. It was a few inches wider than the plate and several inches shorter. Umpires in the real world were reluctant to call strikes much above the batter’s belly button — especially if they were high or hanging breaking pitches.

And something else — also obvious — was happening. A few years ago, batters started uppercutting more (launch angle!) and pitchers responded by throwing more high pitches, because high pitches are harder to make contact with if you are uppercutting.

These trends are not the only factors in today’s decline in batting, but their combined effect has been more strikeouts and less offensive action.

My question is: did MLB mean to do this?

If they didn’t, then the solution is obvious: simply enforce the real strike zone as it had evolved until, say ten years ago, instead of the literal rulebook strike zone. Then we won’t need to move the mound, change the baseball or deploy other new rules to help the batters.

June 28, 2021

Launch Angle Ruining Baseball -- in 1856

Once upon a time, a sportswriter criticized the batters of the New York Knickerbockers for upper-cutting the ball. “No club,” he wrote, “strikes with greater power, but from their habit of striking high, they give too many chances for such excellent clubs as the Gotham and Eagle.”

The strictly amateur New York Knickerbockers, founded in 1845, were one of the earliest known baseball clubs. The above quotation is from Porter’s Spirit of the Times, a national sports weekly; it was written in 1856.

It may be that he was right, that outfield defense had improved to the point that too many of the Knickerbocker power hitters’ long fly balls were being turned into outs. (These were the days before outfield fences).

Another possibility is that the Knickerbockers had figured out what Babe Ruth figured out in the 1920s, what Ted Williams preached in the 1940s, and what major league hitters have re-rediscovered today, that the way to produce runs in baseball is not to hit down on the ball—as high school coaches told me, my father, and my grandfather to do—but to drive it in the air as far as possible.

Because that works.

March 4, 2021

The Man Who Invented Modern Pitching - Which Killed Him

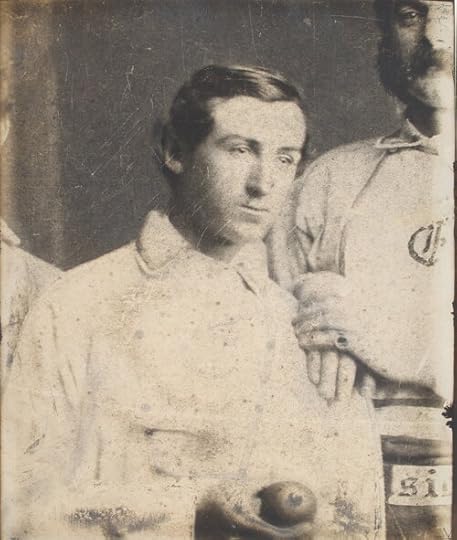

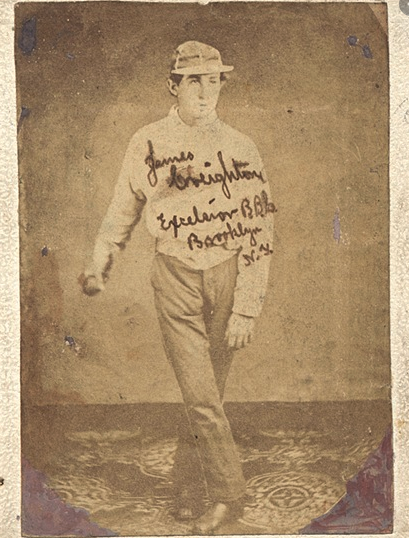

The story of James Creighton is the oldest and saddest one in the baseball book.

Creighton, who became baseball’s first national star in the early 1860s, possessed the game’s most indispensable skill, the ability to get good hitters out. The rare players who can do that have been overworked and abused for 150 years. Every time they take the mound, modern pitchers are doing what James Creighton was the first to do -- walk a tightrope between making effective pitches and injuring themselves. Sometimes they fall off the tightrope. Today, it hardly makes news when an exhausted, overworked pitcher literally rips his elbow ligament into shreds; surgeons simply put in a new ligament taken from another part of the pitcher’s body and he is back at work in 18 months. If that one tears, they do it again. Rest a sore shoulder? Not with games to win and money on the line. Arm injuries end careers in the majors, the minors, college and high school every day. But throwing a baseball too hard for too many innings cost Creighton much more than a career.

James Creighton was born in 1841 and died in 1862. That is no misprint — he died at 21. He played during baseball’s Amateur Era (the first professional baseball league was founded in 1871.) Before Creighton, baseball was a hitter’s dream. The rules of the time required that the rubber-packed, lively baseball be delivered dead underhand with no wrist snap. Think of pitching horseshoes rather than what we mean by the word pitching today. There was little speed or deception; pitchers more or less put the ball over the plate and ducked. There was no strike zone in Creighton’s day because none was needed; pitchers gained little by throwing pitches that batters wouldn’t swing at and batters gained little by taking hittable pitches. Not surprisingly, home plate took a beating. A score of 7-4 raised more eyebrows than a score of 65-50.

Around 1860, while pitching for the great Excelsiors of Brooklyn, Creighton figured out a legal or apparently legal way to throw very hard, with unusual movement and command. His new style of pitching was immediately and widely imitated. Transforming pitching into a weapon, it so upset the balance of power between offense and defense that it led to the creation of the strike zone, which has been the center of the action of a baseball game ever since. Before the strike zone, baseball games were decided by which defense did a better job of controlling balls put in play; ever since, they have been decided by who wins control of the imaginary box hovering over home plate. The strike zone is the main reason that baseball is watchable on TV.

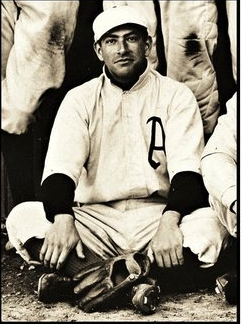

The first baseball card?

James Creighton’s legacy remains with us in other ways, too, whether most fans have heard of him or not. He was the subject of a posthumous carte de visite that may be considered the first baseball card. In August of 1858 James Whyte Davis of the Knickerbockers wrote parody song lyrics for a banquet attended by the principal New York and Brooklyn baseball clubs. This is one of the stanzas about the Excelsiors:

They have Leggett for a catcher, and who is always there,

A gentleman in every sense, whose play is always square;

Then Russell, Reynolds, Dayton, and also Johnny Holder,

And the infantile “phenomenon,” who’ll play when he gets older.

The “infantile phenomenon” is a veiled reference to the teenage James Creighton, then playing for one of the Excelsiors’ affiliated youth clubs. It comes from Charles Dickens’s 1838 novel Nicholas Nickleby, in which a theatrical child prodigy is advertised as the “infant phenomenon.” It is likely the source of the term “phenom,” which is still baseball slang for a promising young player.

In the absence of video or film, we don’t know what Creighton’s pitching actually looked like. Atlantics star Pete O’Brien, who batted against him, described it as “something entirely new, a low, swift delivery, the ball rising from the ground past the shoulder of the catcher.” Does this mean that Creighton delivered the ball from a lower angle than other pitchers, or that his pitches had a four-seam-type hop to them, or that he was throwing an underhand breaking pitch of some kind? Eyewitnesses all agreed that Creighton threw extremely hard, but they also talked of his use of “twist.” What they meant by that is unclear. It seems that Creighton was able to achieve a break or some other kind of deceptive movement on his pitches. He may have thrown the first curve ball.

Based on O’Brien’s description of Creighton’s delivery, some of Creighton’s perceived velocity may have been the result of a deceptive release point. Before radar guns, it was not easy to distinguish between pitches that were difficult to pick up visually and pitches that were simply traveling very fast. Contemporaries of Creighton also said that he did not run up to the pitching line, as other pitchers of the time did, but took a single stride like a modern pitcher. The few images we have of Creighton’s delivery show him twisting his lower body in a strange way. Both would be consistent with Creighton using a lot of hip torque, which would create a whipping action and increased arm speed. They are also consistent with throwing a curveball, which is difficult to do while on the run.

We may not know exactly what kind of pitches James Creighton threw or how he threw them, but we do know that they had a devastating effect. When overmatched batters realized that they couldn’t hit Creighton, they went to Plan B — they tried to tire him out by leaving the bat on their shoulders and taking dozens of pitches. This despised tactic caused the rules to be changed to give the umpire discretion to call strikes as a warning. It took a few years, but called strikes eventually became part of the game. This was followed by called balls and, ultimately, the establishment of the modern strike zone. The strike zone that we use today is essentially a response to the revolutionary new way of pitching pioneered by James Creighton.

During a game on October 14, 1862 Creighton became ill. He died in agony four days later. The press and public assumed that the cause was a traumatic injury sustained during the October baseball game. The September 16, 1865 Brooklyn Daily Eagle gives the following account: “...in making a third attempt at the ball [Creighton] struck with great force and immediately fell down. After a while he felt no more uneasiness, and played the balance of the game. But alas! He had ruptured some of the internal organs, and in a few days the baseball fraternity were startled with the announcement, ‘Creighton is dead.’” Like an expensive Bordeaux, the story of Creighton’s death improved with age. In his 1910 book The National Game, Alfred Spink published the following account by former Atlantics outfielder John C. Chapman: “I was present at the game between the Excelsiors and the Unions of Morrisania at which Jim Creighton injured himself. He did it in hitting out a home run. When he had crossed the rubber [i.e. home plate] he turned to George Flanley and said, ‘I must have snapped my belt’... It turned out that he had suffered a fatal injury.”

Neither of these stories can be true. They are inconsistent with Creighton’s known actual cause of death, a strangulated intestine. A strangulated intestine is normally caused by an inguinal hernia, which is an inherited weakness or gap in the inguinal canal, behind the groin area, through which contents of the abdomen sometimes protrude. If a section of intestine becomes caught, its blood supply can be cut off, which would lead to a gangrene infection. Today, an inguinal hernia can be easily diagnosed and repaired with surgery, and a strangulated intestine is quite treatable. But in the 1860s there were no surgical options or antibiotics, so reaching the gangrene stage meant certain death.

Dr. Joseph B. Jones, physician and President of the Excelsior baseball club of Brooklyn

There are two problems with the idea that Creighton fatally injured himself swinging a bat one day in 1862. One is that an inguinal hernia is a chronic condition and is not caused by a single event. The hernia would have worsened over a long period, probably years. Pitchers in Creighton’s time threw a lot of pitches in a game. Creighton threw more than most because of the waiting tactics used against him by overmatched batters. It was not unusual for Creighton to throw over 50 pitches in a single inning or to record game pitch counts in the 200s or even the 300s, numbers that are unthinkable today. His unusual pitching delivery may have added additional strain. The other problem is that the inguinal hernia was a well-understood medical problem in the mid-19th century. Creighton would have been treated for it, and would have worn a truss. And the Excelsiors club was full of doctors. At least two of them, team president Joseph B. Jones and first baseman A. T. Pearsall, knew Creighton intimately. They would have known that inguinal hernias are exacerbated by long-term physical stress, for instance from repeated violent twisting or weightlifting and they would have known of the risk of a strangulated intestine. It is hard to escape the conclusion that the people that Creighton played for and with knew that they were risking his health in order to win baseball games.

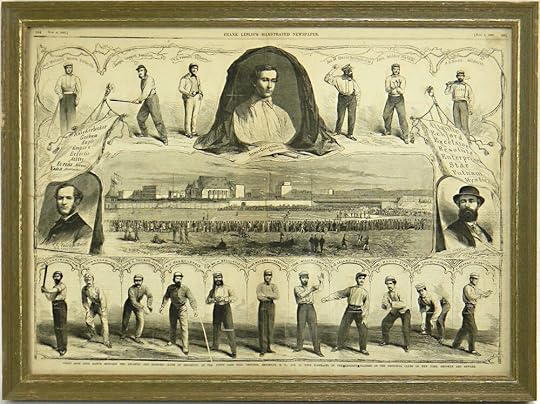

James Creighton’s breathtaking grave monument in Brooklyn;’s Green-Wood cemetery

The loss of Creighton at twenty-one years old hung heavily over baseball for years. In 1865, three years after Creighton’s death, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper carried a two-page spread depicting the baseball world and its principal clubs and figures. At the top is a larger than life James Creighton, shrouded in black crepe, looking down as if from the next world. Creighton’s death cast a particular pall over the Excelsiors. Even though they continued to play through the 1860s, the club dropped quickly out of the ranks of the top clubs. Grief and guilt over Creighton’s untimely death may have played a role in this. Later baseball clubs made pilgrimages to Creighton’s grave monument in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood cemetery—a form of tribute that has no parallel. In 1866 the Washington Nationals traveled to Brooklyn to play the Excelsiors. They stopped at Green-Wood to pay their respects to Creighton. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle called Creighton’s grave “the Mecca of ball players, the sole relic of the noblest and manliest exponent that the national game has ever had.”

November 19, 2020

WHAT'S AN ECKFORD? Why one of the earliest baseball clubs was named after a Scottish shipbuilder

Henry Eckford (1775-1832), godfather of American shipbuilding. The Greenpoint Eckfords baseball club was named after him but he never played the game

The patriotic pride of pre-Civil War Americans was their shipbuilding industry, which traced its beginnings to the naval vessels built by Henry Eckford during the War of 1812. Eckford taught the next generation of great American shipbuilders, including Isaac Webb, John Dimon and John Englis, whose yards lay along the New York City side of the East River near Corlear’s Hook. The shipyards of New York, Boston and other East Coast cities struck a blow for American economic independence by ending decades of British domination of long-range commercial shipping. Their primary weapon was the American clipper. These magnificent sailing ships set speed records to Europe, the West Coast and the Far East. Running out of space in the 1840s and 1850s, the New York City shipyards relocated to the sparsely populated farmland and orchards of Greenpoint and Williamsburg on the Brooklyn side of the East River.

The 1862 launch of the ironclad warship Monitor, built by John Ericsson in 101 days

Thousands of shipwrights and workers in dependent industries went with them, moving to Brooklyn from the 7th, 10th, 11th and 13th Wards of New York City. They brought their culture, including baseball and, according to legend, the peculiar way of talking that became known as Brooklynese. (If you go today to Greenpoint, where I am typing these words, and talk to a non-Polish-born local, you can still hear south, boiler and there pronounced “sowt,” “burluh” and “deh-ah”).

In 1855, Frank Pidgeon, William H. Bell and others formed the Eckford baseball club, named in honor of Henry. Like most of the original Eckfords, Pidgeon and Bell grew up around the New York City shipyards. For a while, the Eckfords straddled the East River, working and playing in Greenpoint while some continued to live in Manhattan. Pidgeon was a dock builder. Bell was a physician, but members of his family worked in shipbuilding. The Eckfords soon became one of the top clubs in Brooklyn and in the country, winning amateur baseball’s national championship in 1862 and 1863. The Greenpoint shipyards produced too many famous vessels to list here, but one of them was John Ericsson’s ironclad Monitor, launched in January 1862 and sunk off North Carolina’s Outer Banks eleven months later.

The Monitor’s officers

The Eckfords stopped playing baseball in the late 19th-century, but lasted as a social club and community organization until the 1960s. The shipyards of North Brooklyn are also long gone, but Greenpoint still has an Eckford Street, a Monitor Street and a Monitor monument.