Daytona Strong's Blog

September 22, 2024

Writers Need to Read: My Multiform Approach to the Written (and Narrated) Word

I read multiple books at a time—fiction, nonfiction, poetry—using a variety of formats: paper, Kindle, Audible, Libby, and Speechify. I start my day with nonfiction, listen to audiobooks on my commute, and find that I get more housework done when I’m listening to a book than when I’m not. Sometimes I listen as I fall asleep, choosing a cozy book I’ve read before as a comforting bedtime story that soothes this lifelong insomniac, helping to slow my thoughts as I drift toward dreams.

(I must say that even as I approach reading strategies for busy people in this post, I’ve also learned the importance of silence and stillness, of taking time to be with myself, my thoughts, and the world. There’s a time for each.)

Writers need to readFor me, reading serves many purposes: the sheer pleasure of it, studying elements of craft and genre, staying abreast of what’s happening in publishing and the market, and supporting fellow authors. It expands and enriches my experience of the world, deepens my empathy, and fosters personal growth, knowledge, and new perspectives. I read to bask in the beauty and music of language and its ability to paint the world in words.

It all counts, no matter the formThere are plenty of opinions on how to read. Some people swear by reading books in paper form only, rejecting e-readers. (I was one of them until about two years ago when the Kindle Scribe came out and I could mark up a book with a stylus and take notes!) Some bring their e-reader everywhere, a streamlined way to reduce clutter or luggage and always have something new to read. And then there’s audiobooks. During my MFA, I encountered people who opposed them, believing that books should be experienced through words on a page. I understand their arguments, including the idea that we can learn more about craft by seeing the words as the author intended. However, I believe that literacy and being well-read are so valuable that any method of absorption is preferable to whatever barriers might otherwise get in the way—like those who struggle to read or find it daunting, leading them to read less than they otherwise would.

My approach, by genre and categoryFiction

Craft and Language: Beautiful prose and elegant writing styles have always drawn me into a book. There’s no better way to experience a masterfully written work than to slow down and savor the sentences, the music of the language, and the structure of the composition by sitting down with a hardcover or paperback. Some recent reads that fall into this category are Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, Deathless by Catherynne M. Valente, and Thistlefoot by GennaRose Nethercott. (If I do listen to a book in this category, such as The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt, I pay attention to the prose, its style, and expert craft while listening, knowing that I can go back to the book, open it anywhere, and examine it further.)Plot and Story: While in the MFA program, I read widely across genres, absorbing the feel of plot, structure, and pacing; familiarizing myself with genre expectations; studying the publishing landscape of the past few years; and noting the stories, genres, eras, writing styles, and authors who inspire me or capture my interest. The format—paper versus audiobook—depends. I listened to A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas, for example, to see what all the fuss was about, but wouldn’t have taken the time to read a hard copy. After reading Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, I decided to do an author study and am listening my way through all her audiobooks to see how she expertly crafts compelling works that entice readers with their glamorous, gritty, and sometimes dangerous worlds, intriguing characters, and cinematic writing style.Nonfiction

Deep Study: When I’m reading nonfiction that’s dense with ideas I want to let sink deeply, I’ll read slowly with a pen in hand. Books like The Dance of the Dissident Daughter: A Woman’s Journey from Christian Tradition to the Sacred Feminine by Sue Monk Kidd fall into this category.Curiosity: If I’m following my curiosity and don’t feel the need for a deep study (as with books like Once Upon a Prime: The Wondrous Connections Between Mathematics and Literature by Sarah Hart), or if I’m already reading other books and can’t get to it for a while, I’ll start with an audiobook. If the topic truly interests me, I might buy a hard copy to refer back to. If Women Rose Rooted by Sharon Blackie and The Heroine with 1001 Faces by Maria Tatar are good examples of this approach.Poetry

Paper. Always. And sometimes reading it aloud.Memoir

I almost exclusively listen to memoirs, wanting to hear the first-person account of an author’s experience told to me, often in their voice if they’re also reading the audiobook. ( Splinters by Leslie Jamison is a great example.)Additional considerationsBooks my kids are reading

Sometimes, I’ll listen to the audiobook versions of what my kids are reading, such as Ghost by Jason Reynolds and Blended by Sharon M. Draper. This allows me to connect with them in a special way and model a love of literature.Book clubs

I participate in several book clubs and love being introduced to books that I otherwise might not read, as well as connecting with others who love reading. I usually listen to the audio versions, especially when I’m not particularly interested in the book. For me, keeping an open mind and connecting with others is important, and the audiobooks allow me to experience a book I otherwise wouldn’t sit down to read. Examples include The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson and Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese—a brilliant book I otherwise would have missed!Books I struggle with

Occasionally, I begin reading a book that, for some reason or another, I struggle with but still want to experience. This happened with The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by N.K. Jemisin, an author whose work I had heard many good things about. I initially didn’t click with the writing style, but when I switched to the audio format and listened to the narrator tell the story, its characters and world—full of love and longing—came alive in a way that still touches my heart. I had a similar experience with The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller, a book I abandoned but later decided to revisit in audio form and am so glad I did.The “should” books

There are some books I feel like I should read for various reasons, or ones I’m curious about but not interested in sitting down to read. Jane Austen falls into this category for me. I’d read some of her novels but am not a “Janeite,” yet I still wanted to know her oeuvre. Listening proved a helpful way to familiarize myself with her work and characters, even if I wasn’t doing it for the sake of pleasurable reading.Of course, by listening to audiobooks, I sometimes wish I’d experienced a beautiful book in paper form. But I let go of the guilt and embrace the fact that I have an insatiable curiosity and love the written word. It’s also my craft and what I do. I’m a writer through and through. By implementing these reading strategies for busy people, I’ve managed to absorb many books, and my life is all the richer for it.

Image: Canva

The post Writers Need to Read: My Multiform Approach to the Written (and Narrated) Word appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

September 14, 2024

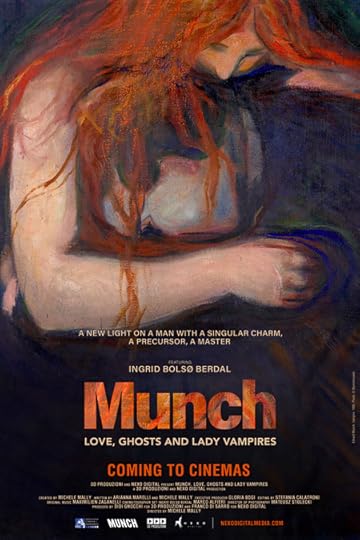

Edvard Munch Documentary Review: Munch: Love, Ghosts, and Lady Vampires

It feels like I’ve known the work of Norwegian artist Edvard Munch for as long as I can remember. His painting The Scream is one of the most recognizable works of art in history, immortalized in pop culture from movies to emojis. Its iconic, almost horror-laced image of a figure with hands to ears, mouth open in terror, is etched into the collective imagination. But Munch’s work is so much more than that single image. He offers a world beyond this frozen moment of panic, a deeper exploration of the human soul. I recently watched the Edvard Munch documentary Munch: Love, Ghosts, and Lady Vampires, and while I considered myself already well-versed in the artist’s works and history, I gained much insight while watching the film.

Several years ago, I took a particular interest in Munch’s body of work during my healing journey. At the time, I had just begun the process of claiming and healing from trauma. Drawing on my heritage has long been a constant source of comfort and healing for me—connecting with my loved ones, learning more about where I come from, and immersing myself in Scandinavian traditions. (That’s how I began writing about Scandinavian food so many years ago.) But in the summer of 2021, my exploration led me even deeper into folklore, mythology, and art, inspired by a dear friend who challenged me to look for magic and wonder in the world.

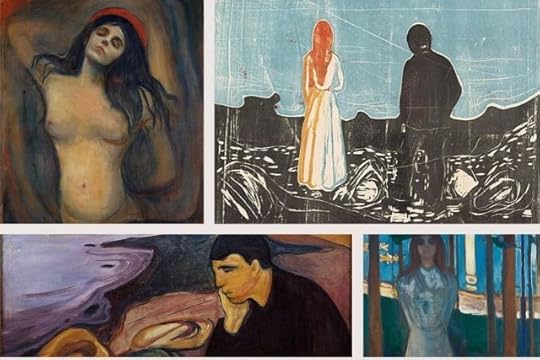

Munch’s art resonated with me in ways I didn’t expect. His paintings—like the melancholic man sitting alone with his hand to his chin along the shore, or the image of a man and woman seemingly worlds apart in Two People: The Lonely Ones, or his Madonna—all tell a story of love, anguish, and obsession. His women are depicted in a range of emotions, from desperation to ecstasy. These figures are both haunting and relatable, revealing the vulnerability and complexities of human relationships.

Recently, I had the opportunity to deepen my connection with Munch’s work through the documentary Munch: Love, Ghosts, and Lady Vampires, which was shown at SIFF Film Center in Seattle. Having visited the Munch Museum in Oslo last summer, where I saw The Scream, The Sun, and many other works in person, this documentary felt like a natural continuation of my exploration. The museum visit had been a profound experience—seeing these works up close, works that had influenced me over time, was nothing short of breathtaking.

The documentary, produced partly in conjunction with the opening of the new Munch Museum in 2021, gave me additional insight into Munch’s life—particularly his time in Kristiania (today’s Oslo). It explored his relationships, the bohemian culture of the period, and the artistic salons that were so vital to his development as an artist. While I had already known much about Munch’s grief and trauma—the deaths of his mother and sister, and his struggles with mental health—this film offered a new lens on the relationships that shaped his life and work.

The documentary used interviews with experts and a dramatized narration by Ingrid Bolsø Berdal, transporting the audience back to Munch’s Kristiania. We were given a glimpse into the cultural and intellectual circles that surrounded him—the friendships, rivalries, and love affairs that fueled his creative output. By the end, I felt as though I had gained a deeper understanding of Munch, not just as an artist, but as a man shaped by the time and place in which he lived.

At first, I found the dramatized narration somewhat jarring. The actor spoke with an intensity that reminded me of a stage production—deliberate and theatrical, with eyes full of emotion. But as the film progressed, this approach began to feel right. It added to the drama of Munch’s life and art, making the documentary feel alive rather than a simple retelling of facts.

The film left me wanting to explore more—about his relationships with women, his psychological experiences, and the deeper meanings behind his art. It was as if this documentary had opened another door into the world of Munch, a world that beckons me to continue looking for the ghosts, the love, and the mysteries hidden in his work.

I highly recommend the documentary to anyone looking to delve deeper into the world of this brilliant artist.

Click here to watch the Edvard Munch documentary trailer.

Munch: Love, Ghosts, and Lady Vampires is available on Amazon here.

Images seen in this post include The Scream (scene photos from my visits to the National Museum of Norway and the Munch Museum in Oslo), Madonna, Two Human Beings: The Lonely Ones, Summer Night: The Voice, and Melancholy.

The post Edvard Munch Documentary Review: Munch: Love, Ghosts, and Lady Vampires appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

A Viking-Inspired Apple Cake and the Goddess with the Life-Giving Apples

Goddess with the life-giving apples. Source of youth and rejuvenation. Kidnapped by the gods and giants. Valued for what she could offer, as much as for who she was?

When I first began diving into Norse mythology, Idunn intrigued me, but admittedly, she took a backseat to the fiercer, more rebellious figures. The boisterous and often bawdy male gods commanded all the attention with their mischief and revelry. And among the goddesses, Freya and Skadi stood out—both bold and uncompromising in their own ways. Freya, the goddess of love, rode a chariot pulled by cats (enough said), and Skadi, the jötunn-turned-honorary goddess, fascinated me with her quest for vengeance (her story even includes a “divine divorce,” adding to what I found compelling about her, given my own ended marriage).

But Idunn? It seemed like she was just there to help others, who valued her for her apples that granted eternal youth. She seemed to lack agency and action, and although she was essential to the gods, she went down in myth as a secondary figure, her role diminished in comparison to the louder, more assertive voices of the pantheon.

I didn’t want to think of her this way. In fact, I’d rather hear about the goddesses’ exploits and adventures than those of their male counterparts. But as with so many mythologies, the men take center stage. Still, over time, as I explored the stories of Skadi and Freya, I came to appreciate Idunn more deeply. She wasn’t just a passive keeper of the apples—her role was vital, quietly underscoring the existence of the gods themselves.

An unfortunate legacyThe story that perhaps stands out most about Idunn is, unfortunately, her kidnapping. It bothers me that her most well-known tale centers on something done to her, not by her. For those of us who have experienced trauma, we understand all too well the feeling of not wanting to be defined by what happened to us. We want to overcome, to transcend—to shift from victim to survivor, and eventually, to warrior. As a survivor myself, it irks me that Idunn often seems like a damsel in distress in this particular quest of the gods.

The story goes like this: the giant Thiazzi, with Loki’s help, kidnaps Idunn and takes her to Jotunheim, the land of the giants. In her absence, the gods in Asgard begin to age. Without Idunn’s apples, their youth and vitality fade, and they realize how much they depend on her.

Finally, they force Loki to rescue her. He shapeshifts into a falcon, flies to Jotunheim, and transforms Idunn into something small (some sources say a nut) to carry her back to Asgard in his talons.

It’s at this point that the story of Skadi (my favorite of the women) has its inciting incident and intersects with Idunn’s. Thiazzi, the giant who kidnapped Idunn, is her father. He turns into an eagle to pursue them as Loki flees. But in his chase, Thiazzi is burned up in a trap laid by the gods. Skadi charges out of Jotunheimen and storms into Asgard in search of vengeance. In her quest, she ends up with a husband—interestingly, based on the appearance of his feet. The entire story makes me scratch my head on many accounts (it’s worth a discussion on another day), but her fiery, bold determination that wins her respect among the gods reflects the kind of boldness that Idunn’s story seems to lack.

What was lost in time?

What was lost in time?The records we have of Norse myths come largely from the Prose Edda and Poetic Edda, which were compiled in the 13th century from earlier sources. Snorri Sturluson, a scholar and politician, played a key role in preserving these stories. Yet, I often wonder how much has been lost over time—fragments of myths that slipped away during the centuries of oral tradition, or that faded with the introduction of Christianity to the region. As with many ancient stories, we’re left with texts that we must interpret through our modern lens, always aware that the original meanings may have shifted in the centuries between their telling and our understanding. What parts of Idunn’s story were lost to time?

Still, no matter what role Idunn played in the past, her story takes on new significance for me today. She wasn’t just a victim; she was a survivor with a quiet power. After all, she possessed the extraordinary power and privilege to grant the gods their youth and vitality—or presumably to withhold it. The gods knew they needed her; they experienced that firsthand when they briefly lost her to Thiazzi. There’s plenty of rich feminist material in that dynamic, though I’ll save that conversation for another day.

Who’s to say how fierce or fiery Idunn might have been? Or perhaps she had a quieter strength, a subtlety that was easily overlooked amid the more dramatic gods and goddesses. And who knows where she got those apples or how she tended to them? She was married to Bragi, the god of poetry, and I like to imagine that gave her an appreciation for art and words and that she found beauty even in the darkest circumstances. As a survivor myself, this thought a thought that brings her to life in a different way, one that resonates with my own love for art and storytelling.

Whether she was bold and outspoken or quietly powerful, I like to think of Idunn as holding a kind of strength that didn’t require her to make a scene. Her power was so essential that, regardless of how loud the other gods were, they all knew they would need her sooner or later.

What a delicious feeling that must have been.

A sweet taste of power

A sweet taste of powerNow, as the apple season arrives in Norway and here in the United States, it feels like the perfect time to give Idunn her due. She may not have been at the forefront of the myths, but she was always there, providing what the gods needed.

For her—and for others like us—I crafted this Viking-inspired Norwegian apple cake, drawing inspiration from ingredients available to the Norse people of centuries past. Rye provides a rustic, earthy flavor, and the warming spices of cinnamon and cardamom—while common in Scandi baking today—also began to influence Scandinavian cuisine during that time.

I’ve made variations of Norwegian apple cakes over the years (click here for a gluten-free version), but this one is for Idunn, as I give her a voice beyond one of victim. I invite you to try this cake, celebrate the arrival of fall, and share it with your loved ones. Reflect on the sweetness of life and the joy that can emerge from our darkest nights.

If you make this recipe, I would love to see your creation! Please share your photos and tag me on Instagram at @daytonadanielsen and Facebook at @daytonadanaielsen. While you’re at it, click here to sign up for my newsletter for more recipes, stories, and insights into Scandinavian culture, folklore, and food.

PrintViking-Inspired Apple Cake with Rye and Honey CreamCourse DessertCuisine Norwegian, ScandinavianKeyword baking, cakeServings 6Author Daytonna DanielsenIngredientsFor the cake3-4 large apples peeled, corned and thinly sliced1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour1/2 cup rye flour2 teaspoons baking powder1/2 teaspoon cinnamon plus more for dusting1/2 teaspoon freshly-ground cardamom1/4 teaspoon salt1 cup butter at room temperature1/2 cup sugar1/4 cup honey2 teaspoons vanilla extract2 large eggsFor the topping1 cup sour cream1 tablespoon honey1 teaspoon vanilla extract2 tablespoons. powdered sugarfresh thyme for garnishInstructionsFor the cakePreheat the oven to 350 degrees F and grease a 9-inch springform pan.In a medium mixing bowl, whisk together the all-purpose and rye flours, baking powder, cinnamon, cardamom, and salt.In a large mixing bowl, cream the butter and sugar until pale and silky, about 3 minutes, scraping down the sides of the bowl as needed. Stir in the honey and vanilla extract. Add the eggs, one at a time, mixing well between additions.Tip the flour into the batter and stir until incorporated.Spread half the batter into the prepared pan. Arrange half the apple slices over this, then spread the remaining batter on top. Arrange the remaining apple slices in a decorative circular pattern, starting in the center and working your way out. Dust cinnamon over the top.Bake for approximately 1 hour, until a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean. Cool on a baking rack, then remove from pan.For the toppingTo make the topping, whisk all ingredients together in a small mixing bowl until smooth. Taste and adjust honey and sugar as needed.Garnish with fresh thyme.

PrintViking-Inspired Apple Cake with Rye and Honey CreamCourse DessertCuisine Norwegian, ScandinavianKeyword baking, cakeServings 6Author Daytonna DanielsenIngredientsFor the cake3-4 large apples peeled, corned and thinly sliced1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour1/2 cup rye flour2 teaspoons baking powder1/2 teaspoon cinnamon plus more for dusting1/2 teaspoon freshly-ground cardamom1/4 teaspoon salt1 cup butter at room temperature1/2 cup sugar1/4 cup honey2 teaspoons vanilla extract2 large eggsFor the topping1 cup sour cream1 tablespoon honey1 teaspoon vanilla extract2 tablespoons. powdered sugarfresh thyme for garnishInstructionsFor the cakePreheat the oven to 350 degrees F and grease a 9-inch springform pan.In a medium mixing bowl, whisk together the all-purpose and rye flours, baking powder, cinnamon, cardamom, and salt.In a large mixing bowl, cream the butter and sugar until pale and silky, about 3 minutes, scraping down the sides of the bowl as needed. Stir in the honey and vanilla extract. Add the eggs, one at a time, mixing well between additions.Tip the flour into the batter and stir until incorporated.Spread half the batter into the prepared pan. Arrange half the apple slices over this, then spread the remaining batter on top. Arrange the remaining apple slices in a decorative circular pattern, starting in the center and working your way out. Dust cinnamon over the top.Bake for approximately 1 hour, until a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean. Cool on a baking rack, then remove from pan.For the toppingTo make the topping, whisk all ingredients together in a small mixing bowl until smooth. Taste and adjust honey and sugar as needed.Garnish with fresh thyme.The post A Viking-Inspired Apple Cake and the Goddess with the Life-Giving Apples appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

September 9, 2024

In the Shadows, We Find Hope: Breaking the Silence on Suicide

September is Suicide Prevention Month, and I’m sharing my experience because I want to help counter the stigma about mental health and seeking help. By doing so, I hope to offer a bit of hope or encouragement to someone who needs to know that even the darkest night can be followed by the most beautiful dawn. You matter. Very, very much.

Note: My story involves a discussion of suicide and trauma. I share it because I’ve seen the light that shines on the other side of despair and have discovered that just when you think there’s no hope, it’s right there, waiting for you to find it. If you are sensitive to these topics or need help, first of all be kind to yourself. Know that you matter. Reach out to a trusted individual or mental health professional for support. I’ve included crisis resources at the end.

Every morning, a new beginningEvery morning, I wake up to a life I didn’t think I’d live to see—a life I didn’t think I wanted or even believed could exist. I survived an aborted suicide attempt three and a half years ago, on a very dark night in 2021. I use the word “dark,” although in hindsight I see that even the darkness was bathed in light, and that even the shadow of death can be laced with life.

I was living with undiagnosed depression, PTSD, and an eating disorder prior to that night. My own attempts to cope with trauma had only made things worse, and I truly believed that no hope remained. I’ll fast forward and say that I am beyond grateful that I lived to see another day.

The thing about despair is that it’s difficult to comprehend unless you’ve lived it. It’s hard to grasp the chokehold it has—the intoxicating lure of death, the extreme comfort and temptation of relief when you start believing that the end might, in fact, be the solution.

I am outside of that despair now, at least for the moment, and I can tell you that life tastes different today than it did in those times. That degree of despair is like another dimension, another reality. That’s not to say it’s an altered state, but it’s fact that there’s something different about the grief and despair that will drive someone to the point of longing for the grave.

The weight of silence

The weight of silenceI didn’t want to die, not really, although I wouldn’t have been able to tell myself that at the time. What I wanted was relief and escape. I’d experienced trauma from both a specific incident and an ongoing situation, the details of which I won’t delve into; it’s complex, deeply personal (days after the attempt, a psychiatrist described my situation as “torturous”). But I will say this: I stayed silent for far too long. I didn’t ask for help or tell people the truth about what was happening in my life.

Silence about trauma leads to “the death of the soul,” writes Bessel Van Der Kolk, M.D. in The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, the work that just about everyone I’ve ever encountered in therapeutic spaces—from patient to provider—has either read or could cite as a seminal work on trauma and its effect on the whole person.

Since that dark night, I’ve spoken about my trauma countless times—to professionals and to those I trust most deeply. I sought help and underwent months and months of intensive treatment. I’m not holding it in anymore. The weight of unspoken trauma no longer eats away at me.

But at the time, I felt trapped. My life, my situation, had become so entangled with trauma that I lost any sense of self-worth. I believed no one needed me. I only allowed in the voices—those specifically directed to me and those coming echoing my past religious culture—that tore me down and perpetuated cycles of abuse. I pretended everything was fine. My loved ones have since told me they knew it wasn’t, but they didn’t know what to do. I didn’t let them in—the voices who could have told me that the lies were just that: untruths.

It’s taken extensive, intensive work to build back a sense of worth and to truly believe that I matter. If I would have spoken up, I might have been able to counter the lies. If I’d let people in, they could have held me in that space, kept me afloat, and helped me build a sense that I mattered and belonged here. Even if I didn’t believe it yet, I could have allowed them to believe it for me.

I see it now. For example, my parents would have been devastated by my death. My kids would have lost their mother. But in that moment, that night, I didn’t think they needed me. When I went into my children’s rooms and said goodbye, took one last look at their sleeping faces—the sweetness of their profiles, their little noses, their tiny lips—I was devastated. I loved them, fiercely, and the thought of what I was doing filled me with grief. Not the kind you can think through rationally, though. That kind of despair doesn’t work like that.

A fight for survivalSomeone once told me that when you’re in despair and feeling suicidal, the body and the mind are trying to live. Each day, maybe even each moment, it’s a fight for survival. It certainly was for me. I’d been ideating for a long time; sometimes, imagining an end was the only comfort that allowed me to get through my days. I didn’t see any other way.

So when the time came, I almost left my children motherless. I left the house and I ran. I ran and I ran until I had nothing left, pushing my body past its limits, wringing out every last drop of energy and adrenaline until I tumbled and I fell. I fell—literally and figuratively. The details will stay private, but it was surreal to be in that moment, knowing I was actually doing it—the thing I had contemplated and rehearsed for so long, the thing I never thought I’d have the “courage” to do. I thought I was too weak to action—until it was time.

We need other voicesBut there I was, alone and unable to talk myself out of it—unable to think rationally through the despair and that all-encompassing temptation. I had my phone, and I remembered all those messages we hear about crisis lines—about calling someone when you’re feeling suicidal. I searched for the crisis line on my phone, stared at the number, and wondered what the hell was happening, what strange existence I was in. But I couldn’t call. I didn’t want to be talked off the proverbial ledge—or at least, I didn’t think I did.

The unexpected fall had stunned me, leaving me injured and bruised. Elements of nature had intervened, leaving me with scars, but perhaps by that delay, they saved me from making my final mistake. While I couldn’t bring myself to call the crisis line, I remembered my children. I needed to make sure they would be okay.

I called my best friend. To ask her to advocate for my kids.

Imagine the friend you call when you’re at your lowest—the one who hears it in your voice, who holds you through the phone, listening without judgment as you bleed out all the secrets that have been killing you. She sits with you, gently reminding you of who you are, telling you that your children need you. And even when you still don’t believe it, her voice pours into the cracks like a salve. This is the friend who holds you with strength and stillness through the phone until your battery dies, and then she drives out to find you, late at night, even though she has her own family at home, even though she doesn’t know exactly where to find you.

When your phone battery finally dies, you’re drained, in shock, and you collapse. You can no longer even move, but you have survived. You still have to face the aftermath, but you’ll get there. You will live, and one day, somewhere down the road, you will realize you’re experiencing the life you almost didn’t get to live, and you’ll be so very, very grateful for the gift.

After I wrote those two previous paragraphs, I noticed that I had shifted from first to second person—a subtle way of distancing myself from the intensity of that experience. In a way, while I was letting the words pour out, I realize now that I was trying to tell you something: you matter, and your life is worth living.

In the depths of darkness, everything can seem so bleak that it feels like there’s no glimmer of another way. That’s what I meant when I wrote about despair earlier—how different everything seems in those times. When you’re in it, it feels utterly rational. You might think, Of course this is right, I’m clearheaded and this makes sense. Because it might even feel like relief. It might even feel like hope. But it’s not real hope—it’s something else, disguised.

There’s so much more I want to share about the days, weeks, and months that followed my own dark night, and I will. But for today, I want to leave you with this: in those darkest moments, there is something more. You’re stronger than you think. You can endure one more moment, one more day. Reaching out can change everything. Silence has a heavy impact. Let others love you and lift you up.

You are not too broken or too far gone. Even if you can’t believe in your own worth, or feel like you have no one to tell you that you matter, there are resources. That night, I didn’t call the crisis line; I called my friend. But knowing it was there helped. There’s also 988. Please use it. I’m so grateful I reached out, even though I did it for my children and not for myself. Please remember this and do the same.

I’ll be honest—the past three and a half years of healing have required hard work. There have been many tears, months of intensive therapeutic treatment, and major changes in my life. But every single moment of it has been worth it. It’s why I’m here. This journey has not only helped me to heal my trauma, but it has also transformed me into a more fully-realized version of myself. I still face depression, and there are times when trauma responses resurface. But it’s different now. I can identify it when it’s happening, recognize it for what it is, and ask for support early on, to help me resist the seduction of despair.

I don’t have all the answers when it comes to suicide prevention. But I do know this from my own experience: there’s light even in the darkest of nights, and that even the most lost among us can find our way home.

If you’re struggling, please ask for help. Please. A phone call saved my life. It’s one step toward realizing that none of us are truly alone, no matter how it might feel at the time.

I wrote the following to accompany the opening photo as I left the desert where I sought treatment after that darkest night:

There’s a story here I’ll someday tell. But in the meantime, all is well. Take care of yourself today. Pay attention to your body—it has things to tell you. Connect with your heart and find compassion for yourself, not just for others. And listen for your voice, and never let it go. You matter.

It’s true. You matter very much.

If you’re in immediate need of help, here is a selection of crisis support resources:

If you’re in immediate need of help, here is a selection of crisis support resources:988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988 – it’s available 24 hours a day, every day of the year.

Trevor Project Lifeline

A 24-hour hotline that supports LGBTQ+ Youth.

Call 988 and choose option 3 to reach the Trevor Project Lifeline or or text 678-678

Veteran Crisis Line

Call 988 and choose option 1. Or text a VA responder at 838-255.

Photo is a snapshot from June 2021. Other images created in Midjourney.

The post In the Shadows, We Find Hope: Breaking the Silence on Suicide appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

March 23, 2023

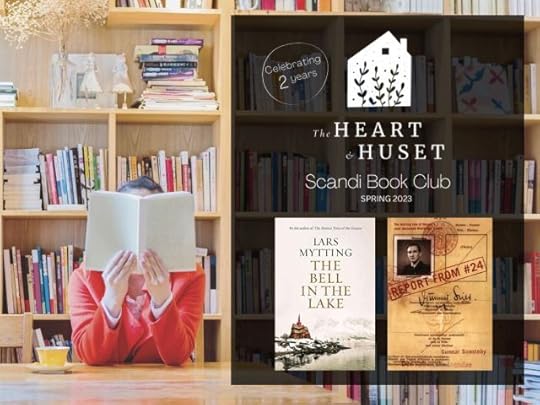

Layers of Worldbuilding, Symbolism, and Identity Continue in “The Reindeer Hunters”

After reading The Bell in the Lake and finding much to love about author Lars Mytting’s world building of the Norwegian village of Butangen with its superstitions, mythology, and legends, I promptly began reading the second book in the trilogy, The Reindeer Hunters. This latest book in the Sister Bells trilogy—released in English last fall—continues the story of the Hekne family through the next generation—that of Astrid’s twin boys.

Much has changed since 1880 when The Bell in the Lake took place, for both individual characters and society. The Reindeer Hunters spans 1903 through the end of World War 1, a time of great change and challenge for Norway. The primary character who bridges both books is Kai Schweigaard, the pastor of Butangen, who in the first book was a modern newcomer who rejected the villagers’ superstitions but comes to embrace the old ways and beliefs as he ages. Societally, the advances of hydroelectric energy railroads, and machinery for dairies changed work and life for many.

Infusing fiction with a sense of timeI attended a virtual book club for the book hosted by Scandinavia House in New York City on February 7, 2023, then later that evening listened to that organization’s recorded author talk with Mytting from November 22, 2022. In the talk, Mytting discussed the process by which he married the storytelling with the major historical and societal changes happening in the book. He begins by playing with the characters, paying attention to them as though they have a will of their own. Then he goes back and looks at the major events that took place in history at the time of the story. Incorporating this research inevitably requires him to make many changes to the story and the laws of the novel, but it allows him to maintain his commitment to the story coming first.

In addition to major events, Mytting gets a feel for the mood of a time and place and what people were interested in by reading contemporary newspapers, sometimes even fiction contemporary to the time, although he would choose what ordinary people would be reading, not the now-classical works that mostly the educated would choose. Doing this for the early 20th century, when the events of this novel take place, was one thing. But when it came to exploring sources for the 1600s—the time of the Hekne sisters, whose famous weave is a major part of the book—he consulted the stories and texts of the country’s preachers to get a sense of the working conditions and the mindsets of the time. (As he pointed out, in rural areas, they would often have been the only people who could read and write, and their responsibilities included documenting the births and deaths, sometimes adding longer stories.)

I appreciate hearing about other authors’ processes, and I took away some practical ways I can add richness to my novel:

What would the characters in my book be reading? In the case of my novel-in-progress, my protagonist, Agneta, grew up steeped in Norwegian folktales and mythology, and these have already informed the book significantly. After writing, research the history and determine what additional layers this might add to my story. Tapestries of history woven through The Reindeer Hunters

Tapestries of history woven through The Reindeer HuntersRegarding the text of the novel itself, motifs are a strong element in both of the Sister Bells books. In The Bell in the Lake, the sister bells were the primary motif, becoming a “controlling image,” as I wrote in my commentary on that novel. In this novel, the Hekne weave is the primary one (the book is called Hekneveven or The Hekne Weave in Norwegian, as opposed to The Reindeer Hunters in English).

While this tapestry is introduced and certainly important in the first book, it takes on a greater role in book two. One of the reasons this lost tapestry is so important is that it is said to portray Skråpånatta, a Day of Judgment. Kai is determined to find the lost tapestry, to discover what future events it foretells. As Mytting discussed in the author talk, such tapestries go back to the pre-Viking times, when they would be unrolled to accompany storytelling, and also when women called norns would weave tapestries depicting a person’s fate or destiny. Though such tapestries are the primary way that textiles feature in the book, Mytting takes it further by exploring the importance of textiles beyond the Hekne weave as well. First, in Kai’s search for the Hekneweave, he finds a pillow with a tartan pattern, whose roots he tries to track down. The book takes place in the Gubrandsdal area of Norway, where in the 1612 Battle of Kringen, several hundred of Scottish mercenaries were killed, the clothes of the slain kept by Norwegians. This is believed to be the origin of the tartan pattern has become common in that region of Norway.

One character explained,

“I think the pattern we see in our local folk costume is a legacy from the Battle of Kringen. Because it differs so greatly from most patterns elsewhere in the country. Our pattern is a tartan. A distinct weaving method. Mirrored around a central thread. And this is found only in the folk costumes of Gudbrandsdalen and Romsdalen, the exact same places where the Scots came. Ours is red and dark green, perhaps to symbolize the blood that was spilled.”

Chapter: The Woman Who Knew

The folk costume mentioned is the bunad, which is another way the author uses textiles to add depth and context to the story. The book opens in 1903, two years before Norway became independent from Sweden. The bunad—now commonly worn by Norwegians and Norwegian Americans for confirmations, festivals, weddings, and other celebrations—was a garment of rebellion at the time, which women would wear as a way to protest the Swedish union. That same character explained the importance of her work in textiles:

“not only to find the oldest costume designs across rural Norway, but what lies behind the colours and shapes. Patterns always attract interpretation, not that they have to mean anything, but they often have a clear narrative behind them, and that’s what we want to tap into. That’s how we can integrate our history, our land and our people. Showing our local histories. The Bunad will be a flag our people can wear!”

Leaving the superstition to the readerThe two books ring loudly of superstition, and a member of the book club at Scandinavia House described it as magical realism. However, during his author talk, Mytting said that he does not insist that supernatural powers exist in these books, but that he allows his characters to believe they do. Similarly, he allows readers to make up their minds. To investigate how the author managed to do this, revisited some passages from the book.

Now and then he had a feeling something was happening. That his feet were somehow heavier as he stood here in the graveyard. That somebody was calling out to him. Though when he turned, there was no-one to be seen. No-one to be seen, but something to mark, just as the villagers claimed to have done through the years, when they said they heard the church bell ring from the depths of Lake Løsnes, calling out to her sister.

Chapter: The Thistle

In that passage, Kai is remembering Astrid, the woman he loved in the first book. Her death continues to haunt him all these years later.

It came in flashes now, the sorrow. His memories no longer brought the same swingeing pain. He liked to sit before the fireplace in the drawing room, smoking and reading, preferably with an open window, so as to feel both the heat from the open fire and the refreshing evening chill. And sometimes she came to him, Astrid, a thickening in the shadows, a shift in the curtains, and he talked with her when things were tough or when he was happy, and sometimes she whispered to him, and other times she was dead.

Chapter: The Thistle

In these two passages, Astrid’s ghost or presence is suggested through Kai’s experience of grief, a feeling he’d have when sensing her presence. Whether that presence is real or not is left to the reader to decide.

Changing industryOne of the greatest delights (of many) while reading these two books has been the importance of the seter, or upland summer dairy farm, which figures largely in my own novel as well. A seter plays an even stronger role in The Reindeer Hunters than it did in The Bell in the Lake, and I was excited to learn more about the tasks and experiences of being a dairy maid at one of these seters from reading the book. As the author discussed, the steep terrain of Norway means that many farms do not have much room for their cattle to graze. So during the summer, they’d be led upland to the endless mountain fields. There, women—usually just one or two for a seter—would do the work of milking the cows, churning butter, and making cheese at these remote locations. It was hard, solitary work. So when machines became available to do much of the work—as they do in this book—it became revolutionary for the women who could now work an independent job with proper wages. As one character said,

“Think o’ cheesemaking. Of the endless work. We dairymaids work wi’ our hands for hour upon hour. We churn the butter and crank the separator till our arms ache. We mun stand and stir the cheese till it be cold through, otherwise it turns grainy. ‘Tis dark by the time a dairymaid be done wi’ her work and she be quite outspent. All this dreary, tedious work can be done for us by electricity”

Chapter: The Dynamo Master

Essence of a time past

Finally, while reading these two books, I was struck by the “Norwegianness” of them. The author’s level of detail while worldbuilding contributes to a rich experience of being rooted in a time and place. During his author talk, Mytting described why The Reindeer Hunters is fitting for a North American audience as well as in Norway: The book takes place during the time of a great Scandinavian migration, so a lot of Norwegian Americans will find elements of that time period and its mood familiar from the stories that their families have passed down through the generations. No wonder I love these books so much. Mytting captures a Norwegianness that feels so much like the Norway that I have imagined as a child of a Norwegian father and Norwegian American mother.

Mytting, Lars. The Reindeer Hunters. Translated by Deborah Dawkin, MacLehose Press, 2022.

(Disclosure: Posts on this site may include Affiliate Links; click here to learn more.)

Read more great Scandinavian books in The Heart & Huset’s Scandi Book Club

The post Layers of Worldbuilding, Symbolism, and Identity Continue in “The Reindeer Hunters” appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

March 18, 2023

Researching a Family Story in “Kristine, Finding Home: Norway to America”

I’ve often wondered what it was like for my grandparents who emigrated from Norway to America in 1956. They were 39 and 40, with child in tow and no command of the English language. What was it like to leave house and home, country and family? They, like the title character in Kristine, Finding Home: Norway to America by Aleta Chossek, left as adults with a child in tow. They, like Kristine, intended to return to Norway after a period of time. They, like Kristine, never moved back. Although much is different between my grandparents’ experience and that of this woman and her family, I appreciated this glimpse into her story, knowing that there is something universal about being human and the way we experience life. Even though I’ll never know much about what it was like for my grandparents to leave Norway, reading Kristine’s story—as written by her granddaughter based on letters, reports, and oral history—expands my understanding of an experience that I’ve never had, and helps me to perhaps understand my grandparents more as well.

Finding—and creating—home

Finding—and creating—homeIn Kristine, Finding Home, Kristine Kristiansen is a young woman deeply engaged with her family in Førde, in western Norway, before she immigrates to America in 1925 to join her husband, Fredrik, who had settled there in advance for business. She created a home in Illinois with Fredrik and their children, always with the expectation of returning to Norway someday. She takes language classes, finds community, and raises their daughters. She adjusts to electricity and other modern conveniences and experiences what it’s like for her family to have their own car. She’s truly created a home, infusing it with Norwegian charm with the curtains she sews from fabric she brought from Norway, preparing Norwegian meals, and offering hospitality to her family and guests. However, her longing for Norway remains. Whenever she inquires about returning to Norway, Fredrik has a reason why this isn’t the right time. Eventually, during a stay at a Norwegian American farm while Fredrik is off at work, Kristine comes to a realization. Among these relatives of Fredrik’s, she finds comfort in being among people who share a knowledge of the foods and culture of their heritage and an ease with the dual languages they share. The experience makes her homesick and also prompts her to think of how much she missed her husband. After receiving wisdom from one of the women, Kristine contemplates her situation in America.

She thought about Selma’s question. Why would she go to Norway? What would she find? Somehow she and Fredrik were both looking for more. With him, she had become aware of new people, new ways of doing things. Being together, seeking more with Fredrik had become a kind of home for her. She knew her role was not here doing what had always been done. What part of being at home is knowing how you fit in.

Chossek

At the end of Kristine’s visit, when Fredrik comes to bring her and their daughters home, they have a simple yet revealing conversation.

Investigating a narrative“Was it a good visit, Kristine? Fredrik asked.

Chossek

“Ja, it was, but I missed you, and I am anxious to get home,” she said.

“To what home, Kristine?” he asked sharply.

“To our home, yours and mine in Waukegan.”

Indeed, Kristine manages to find home. Not in Norway, as she had always expected, but in America, as she and Fredrik build a home for themselves and their children, and for the generations to come. The author is the granddaughter of Kristine’s oldest child, Odny. Chossek crafted Kristine’s narrative through letters sent between Norway and America, Odny’s college reports, and stories told by relatives. Chossek describes in the afterward,

Each of us descendants knows part of the story; some details differ, but none of us has a full understanding of what it was to come to the United States in 1925 with a baby in tow, or to make a home and a living in Waukegan, Illinois.

Chossek

The stories in this book are a narrative of how it may have been. The facts, names, places, and events are all as accurate as memories, written records, and photographs allow. The conversations, motivations, and feelings form the arc of Kristine’s transformation from naïve, bewildered newcomer to matriarch of her small family and leader in her church and community.

To think of Aleta having access to letters sent between Norway and America, of Kristine’s child’s college reports of the immigrant experience, etc.—that she had access to the materials that she did—what a gift for her! And what a gift that she created this book for her family, and also for the rest of us who can now experience an account of one woman’s experience of immigrating to America from Norway.

The value of storiesIn 2009, when Grandma Agny was about to turn 93, I decided it was time to ask her if she’d begin telling me about her life. What was it like to live through the war and the occupation of Norway? To have a baby during that time? To later bury another baby? To leave home and country and family and start a new life in America? It was a sunny July Sunday morning in Seattle, and I was just about to leave the house to celebrate Grandma’s birthday with her and my parents. I was going to ask her if she would start telling me her stories. The phone rang. It was my mom. Grandma was gone. I was shocked by the loss and the grief stung all the more, as it was laced with regret that I hadn’t done this sooner. I’ll always wish I knew more about my family’s story. I used to daydream that I would happen upon a treasure trove of correspondence that would reveal what I missed. I am grateful, however, for writers such as Chossek who have the gift of such materials and the generosity to share them with the world. Chossek knows the value of heritage. As she writes in the afterward,

In 1962, I did now know how important visiting my mother’s birthplace with Grandma was to me and my identity. To stand in the room where my mother was born, to walk the path from Kristine’s girlhood home to the church, to have coffee with her friends, to hike in the mountains surrounding Førde, to listen to the waterfall, Huldfossen, was to experience my origin story rather than simply hear it.

Chossek

That and future time spent in Norway gave meaning and shape to who I was becoming then and who I am today.

Many of the Norwegian Americans I have met over the years share a similar sentiment, and I suspect that this story will resonate with many, as it has for me.

Chossek, Aleta. Kristine, Finding Home: Norway to America. First edition. Waukesha, WI: Ten 16 Press, 2019.

(Disclosure: Posts on this site may include Affiliate Links; click here to learn more.)

Read more great Scandinavian books in The Heart & Huset’s Scandi Book Club

The post Researching a Family Story in “Kristine, Finding Home: Norway to America” appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

February 27, 2023

A Handful of Scandinavian Books (and Other Titles I Finished in February 2023)

A large portion of my work in the MFA consists of reading extensively and studying the works of authors across a range of cultures, genres, and styles. Last month I began a monthly series documenting the books I’m reading. Here’s a look at February’s reading, beginning with a handful of Scandinavian books. Perhaps you’ll find a new favorite here!

Books by Scandinavian authors, in translation

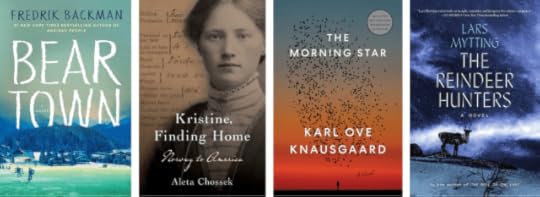

Books by Scandinavian authors, in translationBeartown

by Fredrik Backman

The first in a series of novels set in the fictional town of Beartown, this novel by Swedish author Fredrik Backman explores the ties that knit a small town together over a dream of ice hockey nationals and what happens when an act of violence creates shock waves throughout the town. As in the author’s other books including A Man Called Ove and Anxious People, Bearrtown features his distinct voice that captures the humanity of each character, even while holding them accountable for their actions.

The Morning Star

by Karl Ove Knausgård

Karl Ove Knausgaard is known largely for My Struggle, the epic six volumes of autofiction that made him an international name. Yet these lengthy and detailed accounts of the quotidian and often mundane are only a slice of the oeuvre he’s produced thus far, consisting of novels, numerous essays and articles. His most recent novel published in English, The Morning Star—while fiction—reflects Knausgaard’s comfort with a range spanning fiction and nonfiction forms as well as an ability to capture the way others perceive and engage in the world around them.

The Reindeer Hunters

by Lars Mytting

After reading The Bell in the Lake and finding much to love about author Lars Mytting’s world building of the Norwegian village of Butangen with its superstitions, mythology, and legends (see my essay here), I promptly began reading the second book in the trilogy, The Reindeer Hunters. This latest book in the Sister Bells trilogy—released in English last fall—continues the story of the Hekne family through the next generation—that of Astrid’s twin boys. While reading these two books, I was struck by the “Norwegianness” of them. The author’s level of detail while worldbuilding contributes to a rich experience of being rooted in a time and place.

Kristine, Finding Home by: Norway to America

by Aleta Chossek

Kristine Kristiansen is a young woman deeply engaged with her family in Førde, in western Norway, before she immigrates to America in 1925 to join her husband, Fredrik, who had settled there in advance for business. She created a home in Illinois with Fredrik and their children, always with the expectation of returning to Norway someday. Kristine’s granddaughter retells this family story through oral history, college reports, and letters sent between one country and another. I also come from a Norwegian family, and I’ll always wish I knew more about my family’s story. I used to daydream that I would happen upon a treasure trove of correspondence that would reveal what I missed. I am grateful, however, for writers such as Chossek who have the gift of such materials and the generosity to share them with the world.

Deluge

by Leila Chatti

I first discovered Chatti during the January residency for my MFA, in her craft talk called “Praise in Hard Times.” I could relate to much of what she said about emotional suffering and the ways that we can cope with it from a place of praise and gratitude. In Deluge, she confronts chronic medical suffering and the idea of it being punishment, addressing religion and desire and evoking ancient women from sacred texts whose lives, though millennia before our own, still offer us the gift of a known experience.

Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative

by Melissa Febos

This collection of essays reads like a combination of memoir, writing masterclass, and fellow trauma survivor providing companionship on the road to healing. From writing about how she wrote her memoir of spending four years as an addict and professional dominatrix to describing the way that writing personal narrative is like a spiritual act of confession that helps to heal trauma, Febos shares with authenticity what it is to be a person for whom writing is as essential as breathing.

The Ocean at the End of the Lane

by Neil Gaiman

Until Norse Mythology back in 2018, I hadn’t read anything by this widely-respected fantasy writer, and I’m glad I dove back in this month with The Ocean at the End of the Lane. This brief novel evokes how it feels to be a lonely child in a big world where the grownups neither truly see nor acknowledge your pain. When the protagonist, then, meets the Hempstock women at the farm down the lane—where the little girl calls the duck pond and ocean and the grandmother remembers when the moon was made—he experiences shelter, even if for only a night, from the monstrous unknown.

Lessons in Chemistry

by Bonnie Garmus

Elizabeth Zott just wants to be taken seriously as a scientist. The problem is, it’s the 1960s and she’s a woman. And a single mom. And was in a relationship with another renowned chemist she must have ridden the coattails of. And they weren’t even married! Of course the reader in 2023 knows that Elizabeth is a legitimate scientist whose struggle is being a woman in a field dominated by men. Even when she reluctantly ends up pivoting to teaching housewives the science of the kitchen in her unexpected TV cooking show, it’s clear she’s won’t be beaten down. Garmus writes with a distinctive voice that’s engaging and witty, making this book a delight to read.

Winter Recipes from the Collective

by Louise Glück

My first encounter with a book of Glück’s poetry, this collection struck me with its restraint and quiet wisdom, reflective of both mortality and of the solace—and even joy—to be found even in the winter of one’s life. After finishing the book, I learned that Glück suffered from anorexia in her youth and forewent a traditional undergrad education in favor of psychoanalysis. This piqued my interest, having experienced anorexia myself, and took me down the road of reading more about Glück as a poet. I look forward to exploring more of her poetry.

The Remains of the Day

by Kazuo Ishiguro

In this post-war British novel, Stevens, an aging butler at Darlington Hall, takes a trip to see a former housekeeper, then Miss Kenton, under the guise of hiring her back. The journey proves contemplative as he reflects on his reserved encounters with Miss Kenton; his service to the estate’s former master, a Nazi sympathizer; the duty of butlers; and on what all this has meant for his life.

Life Path: Personal and Spiritual Growth through Journal Writing

by Luci Shaw

I’ve experienced great personal benefits from journaling yet maintain a practice that ebbs as much as it flows, and therefore appreciate hearing the ways that other writers approach it. Shaw is a poet in the Pacific Northwest with a similar religious tradition as mine. Since I have been in a lengthy process of deconstructing, I found much of the book too religiously simplistic, but the gems in the book are attainable nonetheless, and I will keep this book nearby as a reference and source for a great many journaling prompts suited to deep reflection and insight.

Follow me on Goodreads for more updates throughout the year. If you love a good list of Scandinavian books or want to stay updated on the progress of the novel I’m writing, sign up for my free newsletter.

(Disclosure: Posts on this site may include Affiliate Links; click here to learn more.)

The post A Handful of Scandinavian Books (and Other Titles I Finished in February 2023) appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

February 24, 2023

Swedish Mazarin Torte with Raspberries (A Fika Friday Recipe)

When I launched The Heart & Huset in 2021, Fika Friday was one of the hallmarks of the online membership community. Initially planned as a montly gathering, it became a cherished event for the founding members, and I increased it to weekly. Fika Friday has been a weekly event ever since, with friendships forming between members from around the country. Food is a part of The Heart & Huset too, and back in the day, this Swedish Mazarin Torte with Raspberries was our first “Fika Friday Recipe of the Month.”

This version of the classic Swedish Mazarintårta combines a shortbread-style almond crust with a luscious almond filling and a layer of raspberry jam. There’s something about the combination of almond, butter, and raspberry that tastes as good as it gets. Somewhere along the line, this recipe has roots in a couple of sources, including Beatrice Ojakangas’ The Great Scandinavian Baking Book, which is–as its title boasts–a great book, and Nika Standen Hazelton’s The Art of Scandinavian Cooking. Do be sure to serve this with fresh raspberries—they provide a fresh contrast to the delectably rich torte. Can be made a day or two in advance.

The Heart & Huset is an online membership community that helps people take a deep dive into Scandinavian culture and traditions. Featuring recipe collections, a Scandi book club, special guest appearances, and more, it’s also a place to meet other like-minded individuals. It’s designed to help you live your best Scandi-style life, no matter your roots or where you call home. The Heart & Huset opens to new members only a few times a year. If you’d like to be notified when enrollment is opening, sign up for A Place at the Table, my FREE weekly Scandinavian Living newslettter, and you’ll be the first to hear about it.

PrintSwedish Mazarin Torte with Raspberries (A Fika Friday Recipe)Course DessertCuisine Scandinavian, SwedishServings 1 tartAuthor Daytona Danielsen (www.daytonadanielsen.com)IngredientsC... cup butter softened*1/4 cup powdered sugar2 eggs1 cup all-purpose flour3/4 cup almond meal/flourFilling2 eggs2/3 cup sugar1/2 cup unsalted butter softened1 cup almond meal or almond flour1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract1/4 teaspoon almond extract1 cup raspberry jamIcing1 cup powdered sugar sifted1 tablespoon waterFresh raspberries for servingInstructionsPreheat oven to 350 degrees F.To prepare the crust, cream the butter and sugar. Add the eggs and beat until light and creamy. Add the flour, salt, and almond meal and mix until stiff. Press the dough into a 10- or 11-inch tart pan with a removable bottom, using your hands to create an even layer across the bottom and up the sides. Spread 1/2 cup of the raspberry jam over the bottom. Set aside while you make the filling.To make the filling, beat the eggs and sugar until light, then beat in the butter, almond meal, and vanilla and almond extracts. Pour the filling into the crust.Bake for 30 to 40 minutes, until the top is golden and slightly firm to the touch. (It will continue to set while it cools.) Slide the pan onto a rack and allow to cool fully.Once the torte is cool, spread the remaining raspberry jam over the top and remove the torte from the pan.Make the icing by whisking in in the water until smooth, adding a few more drops if needed to get the desired consistency. Spread over the top of the torte, and garnish with fresh raspberries.Notes*I use salted butter; if you’re using unsalted butter, add about 1/8 tsp to the crust.If you enjoy this Swedish Mazarin Torte, find even more sweet and savory treats in my cookbook

Modern Scandinavian Baking

!

PrintSwedish Mazarin Torte with Raspberries (A Fika Friday Recipe)Course DessertCuisine Scandinavian, SwedishServings 1 tartAuthor Daytona Danielsen (www.daytonadanielsen.com)IngredientsC... cup butter softened*1/4 cup powdered sugar2 eggs1 cup all-purpose flour3/4 cup almond meal/flourFilling2 eggs2/3 cup sugar1/2 cup unsalted butter softened1 cup almond meal or almond flour1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract1/4 teaspoon almond extract1 cup raspberry jamIcing1 cup powdered sugar sifted1 tablespoon waterFresh raspberries for servingInstructionsPreheat oven to 350 degrees F.To prepare the crust, cream the butter and sugar. Add the eggs and beat until light and creamy. Add the flour, salt, and almond meal and mix until stiff. Press the dough into a 10- or 11-inch tart pan with a removable bottom, using your hands to create an even layer across the bottom and up the sides. Spread 1/2 cup of the raspberry jam over the bottom. Set aside while you make the filling.To make the filling, beat the eggs and sugar until light, then beat in the butter, almond meal, and vanilla and almond extracts. Pour the filling into the crust.Bake for 30 to 40 minutes, until the top is golden and slightly firm to the touch. (It will continue to set while it cools.) Slide the pan onto a rack and allow to cool fully.Once the torte is cool, spread the remaining raspberry jam over the top and remove the torte from the pan.Make the icing by whisking in in the water until smooth, adding a few more drops if needed to get the desired consistency. Spread over the top of the torte, and garnish with fresh raspberries.Notes*I use salted butter; if you’re using unsalted butter, add about 1/8 tsp to the crust.If you enjoy this Swedish Mazarin Torte, find even more sweet and savory treats in my cookbook

Modern Scandinavian Baking

!

(Disclosure: Posts on this site may include Affiliate Links; click here to learn more.)

The post Swedish Mazarin Torte with Raspberries (A Fika Friday Recipe) appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

February 11, 2023

Pannekaker: What Makes these Pancakes Norwegian, Anyway?

I’m writing this from my kitchen this morning, where the aroma of melted butter and sugar lingers after breakfast. It was a pannekaker morning for my kids, and all is quiet again after the morning rush, when they came to the kitchen to devour the Norwegian pancakes nearly as quickly as they came off the pan.

I love these times–making something from our Norwegian heritage for my kids and sharing in a tradition we’ve developed together over the years.

The tradition of making pannekaker for my children began when my oldest was a toddler. I’d been hired to teach a baking class at Seattle’s Nordic Heritage Museum (now the National Nordic Museum). They were hosting a series of classes on pancakes from each of the Nordic countries and wanted me to instruct the class on the Norwegian kind. I’d grown up eating Swedish pancakes in Seattle but didn’t know there was a distinction. After consulting with a variety of sources, I discovered that Norwegian pannekaker are a little thicker and eggier than Swedish pannkakor, but they’re really quite similar.

“Mama gets to make pancakes for work,” I told my toddler son as I prepared for the class all those years ago, researching and analyzing recipes as I developed my own version with the right balance of delicacy and toothsome bite, and with plenty of flavor. We ate plenty of Norwegian pancakes the week of the class, and I was so grateful to be able to integrate work and motherhood in this way.

We were beginning a tradition that week, one that’s carried on over the years with his sister, with whom I was pregnant at the time. It’s linked to the reason I began cooking Scandinavian food to begin with. I grew up with food being a primary link to my heritage. My grandparents–one set directly from Norway, the other Norwegian by way of North Dakota and a few generations–favored Scandinavian dishes in much of their cooking and baking, particularly during the holidays. Lefse, lutefisk, ribbe, boller, vaffler, riskrem, sandkaker, krumkaker, potato dumplings, the list goes on–food was one of the ways they showed love. Being able to share this heritage with my kids through the foods I serve (and sometimes invite them to make with me) is such a joy, as I know that it’s not just heritage that I am serving, but a legacy of love.

About pannekaker

About pannekakerSomething worth noting about pannekaker is that it’s traditional to eat the pancakes with soup for dinner—sometimes a yellow pea soup, other times a version studded with little pieces of meat and vegetables. While the idea of eating pancakes with pea soup originated in Sweden, many Norwegians have adopted the tradition, making the combination comfort food to people in both countries.

When developing this recipe, I noticed a lot of similarities between the ingredients in other ones. Basically, if you have flour, salt, sugar, eggs, milk, and butter, you can make pancakes. The differences come from the flavorings—which can include cardamom, lemon zest, and vanilla—and the ratios. Through testing I came up with my ideal ratio, which turned out similar to some others—the ultimate in authentic pannekaker, in my opinion. If you’d like to add any of the flavorings, go ahead.

Be aware that practice makes perfect. Don’t be afraid to just start cooking—the first ones will be imperfect and might even tear while you’re flipping or rolling them. That’s okay—it’s part of the process, and each one will turn out better than the last as you get the technique down and adjust the heat of your pan to the right temperature.

To serve, consider lingonberry preserves or perhaps another fruit jam with sour cream. Butter and sugar is another classic combination. I hope you’ll give these a try.

PrintPannekaker (Norwegian Pancakes)Recipe by Daytona Danielsen, daytonadanielsen.comCuisine Norwegian, ScandinavianServings 3Ingredients3/4 cup all-purpose flour1/4 teaspoon kosher salt1-2 tablespoons sugar1 teaspoon vanilla extract3 eggs1 1/2 cups whole milk2 tablespoons unsalted butter melted, plus more for panInstructionsMix all ingredients except butter in a medium-sized bowl using a whisk or fork until the batter is smooth and you have no lumps. Stir in butter. Refrigerate for a half an hour to let the batter rest.Meanwhile, warm a pan over medium heat. I prefer a well-seasoned cast-iron pan, which minimizes the need for additional butter to keep the pancakes from sticking.Melt a little butter in the pan. To get started on your first pancake, pour in enough batter to thinly coat the bottom of the pan—I find that a 1/3-cup measure is just right for my 10-inch pan. Twirl the pan around to coat the bottom, and when the top starts to set and the edges begin to color slightly, carefully but confidently and swiftly slide a heat-safe silicone spatula under the pancake, jiggling it slightly as you do, and flip the pancake. It will probably need about 2 minutes on the first side and a minute or so on the second. When done, use the spatula to roll the pancake in the pan and transfer to a plate.Repeat until you’ve used up all the batter, adding a little butter to the pan between pancakes if necessary. Cover the pancakes with a tent of foil paper as you go to keep them warm.Find even more sweet and savory treats in my cookbook Modern Scandinavian Baking !

(Disclosure: Posts on this site may include Affiliate Links; click here to learn more.)

The post Pannekaker: What Makes these Pancakes Norwegian, Anyway? appeared first on Daytona Dawn Danielsen.

February 9, 2023

Norwegian History and Lore in Lars Mytting’s The Bell in the Lake

Norway is rich with folklore and mythology, and Norwegian author Lars Mytting captures the essence of this deeply in The Bell in the Lake. The first in a planned trilogy of novels, this story unfolds in the isolated village of Butangen in southern Norway. An air of superstition surrounds the story from the first pages when we become briefly acquainted with the local legends, the conjoined Hekne sisters who were born generations before the story’s main events.

Halfrid and Gunhild were famous for their weaving skill, in particular a tapestry called Skråpnånatta, depicting a day of judgment like Ragnarök. It was said that the sisters—who shared everything they saw and experienced—shared a glimpse into the kingdom of the dead when the first one died, leaving the second to finish the prophetic scene.

The bells, forged in their memory, became objects of lore that the people of Butangen carried for generations, even as the outside world and modernism entered the village. The bells were said to ring of their own accord—a portent of something to come. As told by one of the villagers,

The bridge between past and future“When the bells were cast, it weren’t just silver that Eirik Hekne threw in. He threw in a lock of each girl’s hair and a piece of her nail. Thus the bells got the talent of seeing into the future, just as the girls had done when they looked into the hereafter. But nobody knows how far into the future the sisters saw nor how far the bells will see. Some say till the end of time, all the way to Skråpånatta. But happen we donae fully understand the truth of Skråpånatta. If they could find the weave, we might know more. With each age we understand summat new, but with each age we lose understanding for the times yore” (125).

The core story takes place generations after the Hekne sisters’ deaths, centered on a descendent of the sisters, Astrid. Having refused the suiters who have since come her way, Astrid yearns to experience the world beyond Butangen, whose inhabitants live and die without seeing much if any of the world outside. She becomes the bridge between the past and the future, the tight confines of the village to the world outside, and the societal expectations and the agency and purpose she finds within herself.

Around 1880, the world comes knocking twice. Once in the form of Kai Schweigaard, the new pastor, and next in the form of Gerhard Schönauer, the German architecture student and artist tasked with drawing the village’s stave church and planning its demolition and reconstruction in Dresden. Astrid gets to know both of these men, curious whether they might provide her with a way out of Butangen.

The villagers bemoan the new pastor’s new ways, preferring their own customs and beliefs. Even so, the church—which is a center of village life—has seen alterations over time, with ornately carved portions removed and supposedly used as firewood without much thought or concern. As for the architect, they tolerate him mostly, leaving him to his work, until word gets out that the legendary sister bells will be leaving Butangen with him when he returns to Dresden.

Stave church as link to Norway’s historyOne of the things I love so much about this book is its strong sense of Norwegian identity. The town of Butangen bears the marks of centuries, and it’s clear it holds the ghosts from the medieval days when the Norse myths were still the common belief and mingled with the Christianity that was still new to Norway. One of the ways that the author accomplishes this sense of place is through the descriptions of the church.

Stave churches have a rich history going back centuries in Norway, with an estimated one thousand being built between the 11th and 14th centuries (today there are 28 remaining; six of them are UNESCO World Heritage sites). Stave churches represent a time when the existing paganism and newly-introduced Christianity mingled, a reflection of the old and new ways which is very much a theme of the book. The distinct architectural style, constructed of staves that vertically upheld the building, was adorned with ornate carvings depicting scenes from both Norse mythology and Christianity. As such, describing the stave church was a way to show the folklore and mythology that were vital to the village and also to Norwegian history, giving the story a strong rootedness with layers of meaning, symbolism, and depth.

Time and place through folkloreAnother tool that Mytting uses to establish a sense of place and time and to cement the story’s rootedness in the village is through folklore. There is much of this in the customs that he describes, from the way the midwife tells an expectant mother how to tell the sex of her unborn child to the sister bells at the center of the story.

The bells serve as a controlling image throughout the novel, to use a term taught by poet Dorianne Laux at my January 2023 MFA residency. Laux described a controlling image as something concrete that haunts a piece of writing, in the way that a familiar would assist a witch—an object that forwards the ideas in a piece of writing and allows a vortex to give it something steady amidst the chaos.

The author took inspiration for the sisters and the bells from stories told by Ivar Kleiven, who collected folk stories from Norway. He establishes the significance of the bells from the beginning:

The Sister Bells had neither a sad nor fearful ring. At the core of each chime was a vibrancy, a promise of a better spring, a resonance coloured by beautiful, sustained vibrations. Their sound penetrated deeply, creating mirages in the mind and touching the most hardened of men. With a skilful bell-ringer the Sister Bells could turn doubters into churchgoers, and the explanation for their powerful tone was that they were malmfulle – that silver had been added to the bronze when the church bells were cast. The more silver, the more beautiful and resonant the chime (6).

The bells are believed to ring out a warning if disaster was about to take place and serve as such harbingers throughout the book. When Astrid learns that the bells are to be taken to Dresden along with the church, she cannot accept this and weaves her own fate with theirs in a quest to keep them in Butangen. Early on, before we even meet Astrid, the author summarizes the story that is to come, making it already a legend:

The bells hung safely in the tower until 1880, when they and the village were the subject of sudden changes and unbending wills. One of the bells would even finish up under water and be hauled up again, and the only person who would have any power over their fate was a young girl of Hekne lineage. Her sacrifice was no less than that made by the Hekne parents centuries ago, but hers had to be made in secret, and for some time only one man would remember her for it. Those who might have wanted to remember would have found it hard to understand her actions without knowing the story of the stave church and the village she called home (8).

Indeed, in a mystical experience, Astrid experiences a vision that emboldens her to become the bells’ protector.