Allen J. Wiener's Blog

January 10, 2017

White Trash - Book Review

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in Americaby Nancy IsenbergViking (June 21, 2016)

Nancy Isenberg has destroyed whatever may have remained of the myth that the United States is a classless society or ever was. She shows that class has been a strong element since Jamestown and that it was deliberately created and cultivated. The poor and disadvantaged were always an inevitable part of the picture and, rather than taking responsibility for an economy that could never achieve full employment, the wealthier classes chose to blame the poor for their condition. Instead of giving the poor a way out of poverty or an avenue to social mobility, those with power and wealth denigrated and punished them for their poverty, used them as canon fodder in often meaningless wars and as the advance shield of westward expansion, removal or extermination of native tribes, and clearing of the land. The poor rarely enjoyed any of the fruits of these efforts, despite paying the price for them.

The wealthy and privileged invented a myth in which the poor were a natural result of civilization. People ended up where they did in the economic and social pecking order because they were fated to. Social Darwinism determined who the fittest were and they would survive and prosper, while others would not. Although she doesn’t mention it, this reflected Calvinist belief in predestination, practiced by Puritan settlers, which enabled early and later Americans to believe that, if people were poor, decrepit, starved, landless and penniless, it was their fate and nothing could (or should) be done to alter their condition. Followers of the Ayn Rand interpretation of history subscribe to much the same philosophy, including Paul Ryan.

Perhaps the greatest irony is how easily those in power have persuaded the poorer classes to work against their own best interests. By deflecting attention from the real cause of their place at or near the bottom rung of society, elites have persuaded the poor that someone or something else was to blame for their condition other than those who actually are responsible for it. Scapegoats have typically included racial minorities or immigrants who were “taking their jobs” or getting help from the government that they didn’t deserve and were paid for with tax money they worked for and unfairly disadvantaged them. Much the same thinking appears to have fueled Trump’s campaign and energized his base. Racism has always played a roll in this process. As Isenberg notes (p. 315):

“Poor whites are still taught to hate—but not to hate those who are keeping them in line. Lyndon Johnson knew this when he quipped, ‘if you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.’”

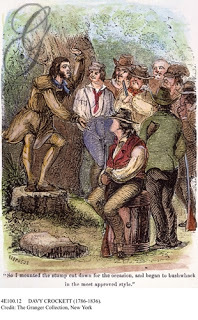

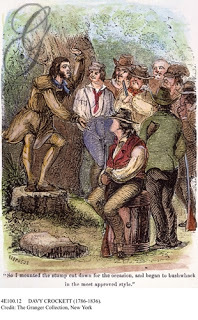

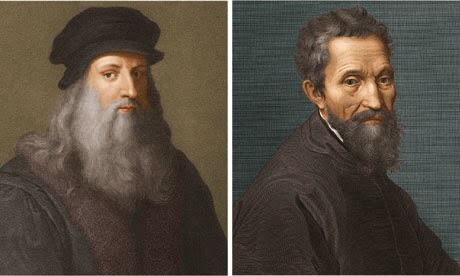

The treatment of squatters on the frontier was not new to me as my co-author, James R. Boylston, and I researched much about this for our book David Crockett in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Poor Man’s Friend (Bright Sky Press, 2009). Isenberg mentions Crockett’s efforts to secure legal title to land that squatters had settled, worked, and built homes on. As a three-term congressman, Crockett repeatedly tried to pass a bill that would give those parcels to the squatters who worked them, or sold it to them at a minimal price. He never succeeded, largely because he butted heads with the Jackson machine and was persona non grata among his own Tennessee delegation. Moreover, commercial land interests were not about to give away good land to squatters when fortunes were to be made from it. Instead, the land went to speculators, who could afford it and sold it at a profit. Although squatters were paid for the “improvements” they’d made to the land, such as houses, barns, fences, fields cleared and cultivated, they were left little option but to move on and squat on another piece of land. Land was the only real means of improving one’s economic condition and, as long as title to land remained elusive, the squatter would remain in an endless loop of poverty.

As Isenberg notes, the government hadn’t the resources to keep squatters off of public lands, but she is right in saying that the government was actually glad to see these frontier areas settled by squatters. It was a way to push boundaries into Indian lands, clear undeveloped lands, and produce cultivated farms. If anyone was going to be killed by Indians or shoved off the land they worked it might as well be these squatters, or “waste people”.

The squatter has been portrayed in literature and film as some sort of undesirable loafer, lazy drunkard, or mentally deficient lunkhead. Perhaps some were, and Isenberg cites accounts from travelers who saw some of the worst cases, such as the mind-boggling clay eaters (I never heard of them before, but didn’t eat for many hours after reading about them). I don’t know how typical these may have been, but these images obscure that of the hard-working poor squatters who simply could not afford to buy land, especially when competing with wealthier speculators and major plantation owners.

Crockett’s constituency included many poor farmers who pressed him not only to secure title to the lands they had worked, but also to fund schools in their areas so their children might get an education. Crockett spoke forcefully in favor of educating the poor as another means to elevate them economically. He said he understood the value of an education because he had suffered from the lack of one himself. Although Isenberg mentions the outrageous tall tales told by and about Crockett, which were a valuable campaign asset, he understood that education and land ownership were the only sure ways to improve the economic lot of the poor. He also suspected that the wealthier classes looked down on the poor and found them unworthy of elevating.

There is a vignette on page 87 that summarizes this business in regard to Jefferson’s theories:

“Jefferson knew that behind all the rhetoric touting America’s agricultural potential there was a less enlightened reality. For every farsighted gentleman farmer, there were scads of poorly managed plantations and unskilled small (and tenant) farmers struggling to survive. …Tenants, who rented land they did not own, and landless laborers and squatters lacked the commercial acumen and genuine virtue of cultivators too. In his perfect world, lower-class farmers could be improved, just like their land. If they were given a freehold and a basic education, they could adopt better methods of husbandry and pass on favorable habits and traits to their children. As we will see, however, Jefferson’s various reform efforts were thwarted by those of the ruling gentry who had little interest in elevating the Virginia poor. Even more dramatically, his agrarian version of social mobility was immediately compromised by his own profound class biases, of which he was unaware.”

By tracing the images of the poor, the “waste people”, the “white trash” of society from Jamestown till today, Isenberg administers the gas to the myth of classlessness in the United States, as well as the Horatio Alger mobility myth. The political and economic system was rigged against the poor, regardless of how hard they might work. It was a “Catch 22” – the economic system blocked upward mobility for the poor, who were then blamed for their condition. We hear much the same fiction today from the right wing extremists who are about to take over our government, and it rings just as hollow today as it did to Crockett.

Of course, squatters were later cultivated as voters, once suffrage was extended to all white males, including those without property (see page 128). Although Jackson didn’t care about squatters (and had helped draft suffrage restrictions for the Tennessee constitution in 1796), he and the Democrats eventually embraced the idea of preemption that Crockett had fought for. In fact, after Crockett died at the Alamo, his son, John Wesley Crockett, won his father’s old seat in Congress and pushed through the very land bill Crockett had failed to pass. Preemption made it possible for squatters to buy the land they had cultivated and become landowners (who, of course, were likely to gratefully vote Democratic).

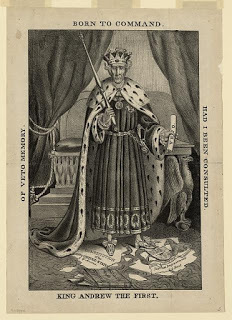

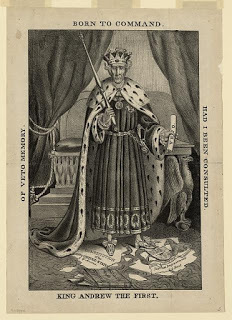

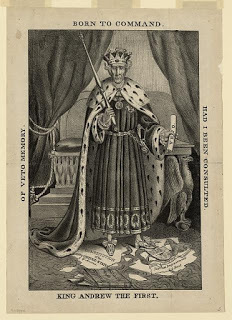

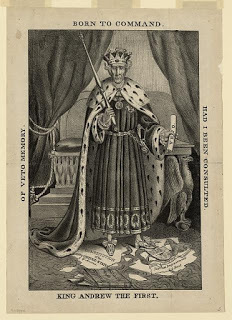

Isenberg provides an excellent portrait of Andrew Jackson, who may be the closest thing to Trump that the country has previously seen in the White House (see pages 123-129). Jackson and his backers used many of the same tactics Trump has, mainly placing him outside the mainstream and even portraying his crudeness, tendency to violence, and illegal acts as a plus. Although Jackson has been portrayed as a hero to and advocate for the “common man” who favored expanding democracy, he was anything but. Although a self-made man who rose from poverty, Jackson had little sympathy for those he left behind. His brutally cold removal of southwestern Indian tribes from their ancestral lands, often at bayonet point, is eerily similar to Trump’s vow to expel immigrants. The populist image of Jackson is as unjustified as his visage on the $20 bill, which will (thankfully) soon be replaced by that of Harriet Tubman.

Most disturbing, perhaps, is the broad distrust of intelligent, educated people like John Quincy Adams in favor of little- or un-educated leaders such as Jackson. The uneducated poor were easily manipulated to distrust eastern elites and the educated and turn instead to those who were more like themselves, who spoke “their language”, regardless of their lack of qualifications or agendas that actually worked against the interests of the poor. We see much the same today, including a discrediting and distrust of legitimate journalism, and the easy acceptance of fake news and propaganda that dovetails with preconceived notions or whatever makes people feel more comfortable.

Isenberg’s discussion of racial and social thinking among such founders as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin is particularly disturbing. It is not unlike the kind of perverted racial thinking developed in Nazi Germany. This was especially true in her discussion of how early American elites viewed breeding and blood lines, even comparing them to the breeding of animals (see pp. 138-139). Although some of these theories allowed that the lower classes could be “improved” or elevated over several generations through breeding, there was never any serious effort to give the poor that opportunity—perhaps for the best as the idea of such breeding is nauseating.

Allen Wiener

Nancy Isenberg has destroyed whatever may have remained of the myth that the United States is a classless society or ever was. She shows that class has been a strong element since Jamestown and that it was deliberately created and cultivated. The poor and disadvantaged were always an inevitable part of the picture and, rather than taking responsibility for an economy that could never achieve full employment, the wealthier classes chose to blame the poor for their condition. Instead of giving the poor a way out of poverty or an avenue to social mobility, those with power and wealth denigrated and punished them for their poverty, used them as canon fodder in often meaningless wars and as the advance shield of westward expansion, removal or extermination of native tribes, and clearing of the land. The poor rarely enjoyed any of the fruits of these efforts, despite paying the price for them.

The wealthy and privileged invented a myth in which the poor were a natural result of civilization. People ended up where they did in the economic and social pecking order because they were fated to. Social Darwinism determined who the fittest were and they would survive and prosper, while others would not. Although she doesn’t mention it, this reflected Calvinist belief in predestination, practiced by Puritan settlers, which enabled early and later Americans to believe that, if people were poor, decrepit, starved, landless and penniless, it was their fate and nothing could (or should) be done to alter their condition. Followers of the Ayn Rand interpretation of history subscribe to much the same philosophy, including Paul Ryan.

Perhaps the greatest irony is how easily those in power have persuaded the poorer classes to work against their own best interests. By deflecting attention from the real cause of their place at or near the bottom rung of society, elites have persuaded the poor that someone or something else was to blame for their condition other than those who actually are responsible for it. Scapegoats have typically included racial minorities or immigrants who were “taking their jobs” or getting help from the government that they didn’t deserve and were paid for with tax money they worked for and unfairly disadvantaged them. Much the same thinking appears to have fueled Trump’s campaign and energized his base. Racism has always played a roll in this process. As Isenberg notes (p. 315):

“Poor whites are still taught to hate—but not to hate those who are keeping them in line. Lyndon Johnson knew this when he quipped, ‘if you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.’”

The treatment of squatters on the frontier was not new to me as my co-author, James R. Boylston, and I researched much about this for our book David Crockett in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Poor Man’s Friend (Bright Sky Press, 2009). Isenberg mentions Crockett’s efforts to secure legal title to land that squatters had settled, worked, and built homes on. As a three-term congressman, Crockett repeatedly tried to pass a bill that would give those parcels to the squatters who worked them, or sold it to them at a minimal price. He never succeeded, largely because he butted heads with the Jackson machine and was persona non grata among his own Tennessee delegation. Moreover, commercial land interests were not about to give away good land to squatters when fortunes were to be made from it. Instead, the land went to speculators, who could afford it and sold it at a profit. Although squatters were paid for the “improvements” they’d made to the land, such as houses, barns, fences, fields cleared and cultivated, they were left little option but to move on and squat on another piece of land. Land was the only real means of improving one’s economic condition and, as long as title to land remained elusive, the squatter would remain in an endless loop of poverty.

As Isenberg notes, the government hadn’t the resources to keep squatters off of public lands, but she is right in saying that the government was actually glad to see these frontier areas settled by squatters. It was a way to push boundaries into Indian lands, clear undeveloped lands, and produce cultivated farms. If anyone was going to be killed by Indians or shoved off the land they worked it might as well be these squatters, or “waste people”.

The squatter has been portrayed in literature and film as some sort of undesirable loafer, lazy drunkard, or mentally deficient lunkhead. Perhaps some were, and Isenberg cites accounts from travelers who saw some of the worst cases, such as the mind-boggling clay eaters (I never heard of them before, but didn’t eat for many hours after reading about them). I don’t know how typical these may have been, but these images obscure that of the hard-working poor squatters who simply could not afford to buy land, especially when competing with wealthier speculators and major plantation owners.

Crockett’s constituency included many poor farmers who pressed him not only to secure title to the lands they had worked, but also to fund schools in their areas so their children might get an education. Crockett spoke forcefully in favor of educating the poor as another means to elevate them economically. He said he understood the value of an education because he had suffered from the lack of one himself. Although Isenberg mentions the outrageous tall tales told by and about Crockett, which were a valuable campaign asset, he understood that education and land ownership were the only sure ways to improve the economic lot of the poor. He also suspected that the wealthier classes looked down on the poor and found them unworthy of elevating.

There is a vignette on page 87 that summarizes this business in regard to Jefferson’s theories:

“Jefferson knew that behind all the rhetoric touting America’s agricultural potential there was a less enlightened reality. For every farsighted gentleman farmer, there were scads of poorly managed plantations and unskilled small (and tenant) farmers struggling to survive. …Tenants, who rented land they did not own, and landless laborers and squatters lacked the commercial acumen and genuine virtue of cultivators too. In his perfect world, lower-class farmers could be improved, just like their land. If they were given a freehold and a basic education, they could adopt better methods of husbandry and pass on favorable habits and traits to their children. As we will see, however, Jefferson’s various reform efforts were thwarted by those of the ruling gentry who had little interest in elevating the Virginia poor. Even more dramatically, his agrarian version of social mobility was immediately compromised by his own profound class biases, of which he was unaware.”

By tracing the images of the poor, the “waste people”, the “white trash” of society from Jamestown till today, Isenberg administers the gas to the myth of classlessness in the United States, as well as the Horatio Alger mobility myth. The political and economic system was rigged against the poor, regardless of how hard they might work. It was a “Catch 22” – the economic system blocked upward mobility for the poor, who were then blamed for their condition. We hear much the same fiction today from the right wing extremists who are about to take over our government, and it rings just as hollow today as it did to Crockett.

Of course, squatters were later cultivated as voters, once suffrage was extended to all white males, including those without property (see page 128). Although Jackson didn’t care about squatters (and had helped draft suffrage restrictions for the Tennessee constitution in 1796), he and the Democrats eventually embraced the idea of preemption that Crockett had fought for. In fact, after Crockett died at the Alamo, his son, John Wesley Crockett, won his father’s old seat in Congress and pushed through the very land bill Crockett had failed to pass. Preemption made it possible for squatters to buy the land they had cultivated and become landowners (who, of course, were likely to gratefully vote Democratic).

Isenberg provides an excellent portrait of Andrew Jackson, who may be the closest thing to Trump that the country has previously seen in the White House (see pages 123-129). Jackson and his backers used many of the same tactics Trump has, mainly placing him outside the mainstream and even portraying his crudeness, tendency to violence, and illegal acts as a plus. Although Jackson has been portrayed as a hero to and advocate for the “common man” who favored expanding democracy, he was anything but. Although a self-made man who rose from poverty, Jackson had little sympathy for those he left behind. His brutally cold removal of southwestern Indian tribes from their ancestral lands, often at bayonet point, is eerily similar to Trump’s vow to expel immigrants. The populist image of Jackson is as unjustified as his visage on the $20 bill, which will (thankfully) soon be replaced by that of Harriet Tubman.

Most disturbing, perhaps, is the broad distrust of intelligent, educated people like John Quincy Adams in favor of little- or un-educated leaders such as Jackson. The uneducated poor were easily manipulated to distrust eastern elites and the educated and turn instead to those who were more like themselves, who spoke “their language”, regardless of their lack of qualifications or agendas that actually worked against the interests of the poor. We see much the same today, including a discrediting and distrust of legitimate journalism, and the easy acceptance of fake news and propaganda that dovetails with preconceived notions or whatever makes people feel more comfortable.

Isenberg’s discussion of racial and social thinking among such founders as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin is particularly disturbing. It is not unlike the kind of perverted racial thinking developed in Nazi Germany. This was especially true in her discussion of how early American elites viewed breeding and blood lines, even comparing them to the breeding of animals (see pp. 138-139). Although some of these theories allowed that the lower classes could be “improved” or elevated over several generations through breeding, there was never any serious effort to give the poor that opportunity—perhaps for the best as the idea of such breeding is nauseating.

Allen Wiener

Published on January 10, 2017 09:28

January 9, 2017

I have been urging people who are concerned about the inc...

I have been urging people who are concerned about the incoming Trump administration to take positive action instead of wringing our hands and lamenting what's gone down. Robert Reich has suggested several ways to do this (see his website and posts on Facebook). Right now, it is imperative that we write and phone our U.S. senators and tell them firmly that Trump's cabinet nominees are almost all unacceptable. I have sent the following letter to my own senators and congressional representative. While the words may be wasted on most Republicans, it is essential that Democrats tell their party that they will not accept weakness, meekness in the face of a bully like Trump and a hypocritical Republican Party that expects the decent treatment it consistently denied to President Obama. I urge everyone to write a similar letter and also to phone their senators and representatives often. Continue to pressure them to resist the Trump agenda.Dear Senator _________:Never before in my 73 years have I been as concerned about the fate of our country -- and much of the world -- as I am at the Trump presidency. His behavior and statements pose potentially horrific consequences.Trump leads a Republican Party that now controls all three branches of the federal government, as well as 33 of the 50 state governments, and is devoted to the most extreme right wing agenda of the past century. Republicans have promised to repeal the ACA and defund Planned Parenthood. These two measures alone would do incalculable harm to millions of Americans who would be left without health insurance and unable to pay for care themselves. Politifact estimates that more than 20 million Americans would lose or be unable to obtain health insurance. Planned Parenthood is among the very few health and counseling resources available to lower-income populations -- men and women alike. Planned Parenthood estimates that 2.5 million women and men in the United States annually visit their health centers each year. While the GOP has made vague reference to replacing the ACA, they have given no details of such a plan and I doubt one exists. Even some Republicans have expressed disapproval of repeal without a replacement plan in place. GOP plans to repeal and to then, later, produce an alternative sound unworkable.The litany of Trump’s racist, xenophobic, and fear-mongering words show that he is dangerous and unfit for the presidency of the United States. Such a threat requires firm, outspoken resistance by you, our representatives in Congress, and by we the people. Careful, safe, and calculated statements are not enough, nor is it the time to retreat in fear of a man who is -- when all is said and done -- a childish schoolyard bully who needs to be resisted, like all bullies.Trump’s long list of lies and self-contradictory remarks are sufficient to conclude that his word cannot be trusted. His evolving statements regarding a wall along our border with Mexico is a graphic case in point. A 2009 Government Accountability Office report estimated the cost of building one mile of fencing along the 2,000 mile border averaged between $2.8 million and $3.9 million, but warned that it could be more. Aside from this move being racist and internationally provocative, he has also made so many different statements about his intentions that even his blindest supporters must feel betrayed by now. Newsweek Magazine reported that “Trump has described his wall as low as 25 feet tall and at other times as high as 55 feet. Sometimes he has his wall running the entire border, other times only 1,000 miles, plus the 670 miles of high steel fencing Republicans spent $2.4 billion on to keep illegal immigrants out of the U.S.” Trump’s estimates for walls of various lengths and heights range from $8 billion to $12 billion. The Washington Post estimated a more realistic cost of $25 billion.Perhaps most frightening are Trump’s attacks on the press, his barring reporters from news conferences and public events who even slightly challenge him, and his reliance on Twitter as his primary form of communication. He gives little thought to what he tweets -- or for that matter, says from any platform -- focuses almost solely on himself and those who personally attack or ridicule him. He makes rash and irresponsible statements about domestic and foreign policy, including suggestions that nuclear proliferation would be a good idea, along with a new trillion-dollar arms race with Russia. The Obama administration already has planned to spend over $1 trillion in the next 30 years on an entire new generation of nuclear bombs, bombers, missiles and submarines, which an independent Federal commission called “unaffordable”. He provoked China by talking to the Taiwanese government, had repeatedly defended of Vladamir Putin and threats against our NATO allies and, perhaps most dangerous of all, has threatened to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem. Jordan has already warned of “catastrophic” consequences if such an ill-advised move is carried out.The legitimate press must be encouraged and empowered to resume its traditional independent, investigative role, without intimidation or demonization. Both the press and Democratic opposition must develop effective ways to communicate facts that disprove Trump’s tweets. That can begin by re-instituting the FCC’s Fairness Doctrine that was repealed by President Reagan. Without that act, the likes of Rush Limbaugh and Fox News would never have gotten off the ground because the Fairness Doctrine required that holders of broadcast licenses present controversial issues of public importance in a balanced manner, including the presentation of opposing points of view.Trump’s repeated condemnation of our intelligence agencies and his propensity to believe other sources over them—including the Russians and Julian Paul Assange, editor-in-chief of the organization WikiLeaks—or just his own internal belief system, is alarming. Trump has more than once insisted that the election was not hacked by the Russians, and that claims of such are no more than sour grapes by the Clinton campaign, and that millions of people voted illegally (presumably all for Clinton) without a shred of evidence to support any of his claims. Leaders of the intelligence community have stood up firmly to Trump’s efforts to discredit and bully them. So must we all.Trump’s refusal to release his income tax statements or discuss his personal finances make it impossible to determine the extent of his conflicts of interest regarding those holdings, as well as his ability to act freely in foreign affairs or domestic economic regulation. Even the Wall Street Journal found that Trump owes at least $1.85 billion to 150 Wall Street firms and other financial institutions. “As a result,” say Journal reporters Jean Eaglesham and Lisa Schwartz, “a broader array of financial institutions now are in a potentially powerful position over the incoming president.”Trump’s nominees for key cabinet posts are a collection of the worst choices in the history of the presidency. Almost every important post would be filled by someone who has expressed condemnation of the department they would lead. Yet, the GOP leadership plans to ram through confirmation of Trump’s nominees without properly vetting them. The Office of Government Ethics has expressed serious concern that Congress is moving much too swiftly to confirm these nominees. More recently, the Office released a statement that it's lost contact with Trump’s transition team since the election. In the past, cabinet nominees were required to file extensive financial disclosures listing any business interests that could pose a conflict of interest. But most of Trump’s nominees -- many of them billionaires, business moguls, and Wall Street financiers -- have not yet disclosed a thing, or their disclosures are incomplete. Nonetheless, Trump’s transition team and some Senate Republicans want to hold hearings on them anyway, starting next week when nine hearings are scheduled, suggesting that Republicans have serious concerns about the qualifications of these nominees, which might be revealed in proper hearings. These same Republicans, including leaders Mitch McConnell and Paul Ryan, refused to even hold hearings on President Obama’s last nominee for the Supreme Court. During the recent campaign, the same Republican leadership threatened to reduce the Court to eight Justices permanently if Secretary Clinton won.A brief look at several Trump cabinet nominees and other appointments is frightening:-- Rex W. Tillerson for Secretary of State: Tillerson, a multi-millionaire, is the president and chief executive of Exxon Mobil and has close ties to Mr. Putin. For that reason, he comes with strong motivation to rescind President Obama’s sanctions against Russia in order to clear the way for Exxon to carry out oil exploration in Russia. -- Jeff Sessions for Attorney General: Sessions is a strong proponent of strict immigration enforcement, reduced spending, and tough-on-crime measures. He supports measures that restrict voting, especially among racial minorities. His nomination for a federal judgeship in 1986 was rejected because of racially charged comments and actions.-- Ryan Zinke for Interior Secretary: This congressman’s views indicate that he can likely be counted on to end President Obama’s rules that stop public land development, curb the exploration of oil, coal and gas, and promote wind and solar power on public lands. -- Rick Perry for Energy: A man who could not remember the name of the department he would lead and has vowed to abolish it.-- Andrew F. Puzder for Labor Secretary: Puzder is chief executive of CKE Restaurants and a major donor to Trump’s campaign. He has opposed fair treatment of workers, an increased minimum wage, and advocates measures that favor the corporate bottom line at the expense of workers.-- Scott Pruitt for E.P.A. Administrator: Trump has vowed to dismantle the agency “in almost every form” and this Oklahoma Attorney General -- who has close ties to the oil and gas industries -- is likely to do exactly that, including clean air and water standards.-- Steven Mnuchin for Treasury Secretary: Mnuchin was Trump’s campaign finance chairman and has no government experience. He is a former Goldman Sachs executive with major Hollywood roots, which is ironic, as Trump often criticized Secretary Clinton for having the same connections.-- Elaine L. Chao for Transportation Secretary: Married to Senator McConnell, she’s been a long-time fixture in Washington and served as Labor Secretary. She is likely to push through Trump’s plan to privatize much of the nation’s transportation infrastructure, such as privately owned toll roads, at taxpayer expense through tax breaks and subsidies, and which will levy tolls on users. Such action would reverse President Eisenhower’s intention in building the interstate highway system to serve commerce and the public.-- Betsy DeVos for Education Secretary: DeVos is a long-time, forceful advocate for privatizing education and would dismantle our public education system to the benefit of the rich and detriment of everyone else. Most of our country’s greatest achievements were accomplished by graduates of public schools. This is as true among business leaders as well as astronauts.-- Ben Carson for Secretary of H.U.D.: Aside from once serving as a frequent butt of Trump’s jokes, Carson lacks management experience and said that he does not want to work in government, making him an odd choice. He also opposes long-standing housing programs that benefit the poor.-- Stephen K. Bannon for Chief Strategist: Bannon is a right-wing media executive and chairman of Trump’s campaign. He is an outspoken racist and propagandist.I cannot state in strong enough terms that, under no circumstances, should any Democrat vote to confirm any Trump nominee. No Trump Supreme Court nominee should receive a single Democratic vote, nor even be granted a confirmation hearing. It isn’t just payback for the eight years of insults -- e.g., “You lie!” -- as well as degradation, racism, and obstruction that Republicans leveled at the Obama administration. Rather, it is the only way to effectively fight and resist a would-be dictator and tyrant like Trump.If the Democratic Party is to stand for anything, it must stand for resistance to the Trump agenda. It must be a loud, forceful voice of opposition and a communications channel that conveys truth to counter Trump’s lies and propaganda. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren can’t do it alone. It will take all of you, all of us, and all of our strength and courage.

Published on January 09, 2017 19:23

January 2, 2017

Crockett Fought Odds in Washington,Tooby James R.Boylston...

Crockett Fought Odds in Washington,Tooby James R.Boylston and Allen J. Wiener

(Originally published in the Nashville, Tennessean, July 20, 2011)

Davy Crockett might not have“patched up the crack in the Liberty Bell,” but when he was in Congress, David Crockett was a fierce opponent of the partisanship that was fracturing Washington and, in Crockett’ s opinion, putting liberty at risk.

Born almost 225 years ago, on Aug. 17, 1786, Crockett would find that things haven’t changed much in Washington. CapitolHill bubbled with as much bitter partisanship back then as it does today. Initially a supporter of President Andrew Jackson, Crockett quickly found himself at odds with Old Hickory and his partywhip-crackers, including fellow Tennessean James K. Polk and New Yorker Martin Van Buren, both future presidents. The problem was that Crockett focused on the needs of the people who had elected him and would not compromise to pleaseparty bosses or even the highly popular president.

Throughout his six years inCongress, Crockett continually voiced his independence from any party when itconflicted with the interests of his constituents or put the nation injeopardy. “The Stars and Stripes,” hewarned, “must never give way to the shreds and patches of party.”

Crockett knew parties were not going away and was not entirely opposed to them,but, like many of the Founders, he was wary of them. “I am a party man in the truesense of the word,” he wrote, “but God forbid that I should ever become so much aparty man as obsequiously to stoop to answer party purposes.” He saw the rise ofpolitical parties as a threat to the country, because politicians were bound tobecome more concerned with the success of their party than the greater good ofthe country.

Like Jefferson, Crockettbelieved democracy was best served by tying citizens closely to the governmentthrough their representatives. He defiantly insisted that “I cannot nor willnot forsake principle to follow after any party and I do hope there may be amajority in Congress that may be governed by the same motive.” But it was avain hope.

Once Crockett bucked the party bosses, he found himself on Jackson’s hit listfor life.

In 1830, Crockett irritated both Jackson and his own congressional delegationby voting against the president’s brutal Indian-removal policy, which led tothe Trail of Tears. Crockett was determined to follow his conscience, insistingthat he had made “a good honest vote and one that would not make me ashamed inthe day of judgment.”

Partisanship continued to infuriate Crockett, and he told a crowd in Baltimorethat “I broke off with Jacksonism whenever I found I could not be a free man…. I gotdisgusted, and knew that the less you handle rotten eggs, the better chance youhave of coming off with clean hands, so I cut loose.”

When a delegation from Mississippi asked his permission to nominate him for thepresidency in 1834, Crockett recognized that it was not a realistic option forhim, but responded anyway, saying “If I am elected, I shall just seize the old monster —Party —by the horns, and sling him right slap into the deepest place in the greatAtlantic sea.”

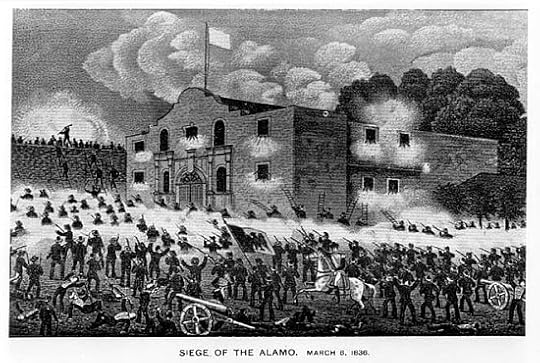

Ultimately, Crockett’s independence cost him his seat in Congress, so he packedhis bags and headed for Texas and, he hoped, greener pastures. Sadly, it wasnot to be. Within a few short months, rockett fell in defense of the Alamo and became the stuff of legend. While hissacrifice there should never be forgotten, his battle against injustice and politicaldivisiveness provides an additional example we could do well to emulate.

Davy Crockett would feel very much at home on Capitol Hill today.

James R. Boylston and Allen J. Wiener are authors of David Crockett in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Poor Man’s Friend(Bright Sky Press).

Amazon.com Listing: http://tinyurl.com/j4xcf9c

Author’s page: http://tinyurl.com/z83b72m

(Originally published in the Nashville, Tennessean, July 20, 2011)

Davy Crockett might not have“patched up the crack in the Liberty Bell,” but when he was in Congress, David Crockett was a fierce opponent of the partisanship that was fracturing Washington and, in Crockett’ s opinion, putting liberty at risk.

Born almost 225 years ago, on Aug. 17, 1786, Crockett would find that things haven’t changed much in Washington. CapitolHill bubbled with as much bitter partisanship back then as it does today. Initially a supporter of President Andrew Jackson, Crockett quickly found himself at odds with Old Hickory and his partywhip-crackers, including fellow Tennessean James K. Polk and New Yorker Martin Van Buren, both future presidents. The problem was that Crockett focused on the needs of the people who had elected him and would not compromise to pleaseparty bosses or even the highly popular president.

Throughout his six years inCongress, Crockett continually voiced his independence from any party when itconflicted with the interests of his constituents or put the nation injeopardy. “The Stars and Stripes,” hewarned, “must never give way to the shreds and patches of party.”

Crockett knew parties were not going away and was not entirely opposed to them,but, like many of the Founders, he was wary of them. “I am a party man in the truesense of the word,” he wrote, “but God forbid that I should ever become so much aparty man as obsequiously to stoop to answer party purposes.” He saw the rise ofpolitical parties as a threat to the country, because politicians were bound tobecome more concerned with the success of their party than the greater good ofthe country.

Like Jefferson, Crockettbelieved democracy was best served by tying citizens closely to the governmentthrough their representatives. He defiantly insisted that “I cannot nor willnot forsake principle to follow after any party and I do hope there may be amajority in Congress that may be governed by the same motive.” But it was avain hope.

Once Crockett bucked the party bosses, he found himself on Jackson’s hit listfor life.

In 1830, Crockett irritated both Jackson and his own congressional delegationby voting against the president’s brutal Indian-removal policy, which led tothe Trail of Tears. Crockett was determined to follow his conscience, insistingthat he had made “a good honest vote and one that would not make me ashamed inthe day of judgment.”

Partisanship continued to infuriate Crockett, and he told a crowd in Baltimorethat “I broke off with Jacksonism whenever I found I could not be a free man…. I gotdisgusted, and knew that the less you handle rotten eggs, the better chance youhave of coming off with clean hands, so I cut loose.”

When a delegation from Mississippi asked his permission to nominate him for thepresidency in 1834, Crockett recognized that it was not a realistic option forhim, but responded anyway, saying “If I am elected, I shall just seize the old monster —Party —by the horns, and sling him right slap into the deepest place in the greatAtlantic sea.”

Ultimately, Crockett’s independence cost him his seat in Congress, so he packedhis bags and headed for Texas and, he hoped, greener pastures. Sadly, it wasnot to be. Within a few short months, rockett fell in defense of the Alamo and became the stuff of legend. While hissacrifice there should never be forgotten, his battle against injustice and politicaldivisiveness provides an additional example we could do well to emulate.

Davy Crockett would feel very much at home on Capitol Hill today.

James R. Boylston and Allen J. Wiener are authors of David Crockett in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Poor Man’s Friend(Bright Sky Press).

Amazon.com Listing: http://tinyurl.com/j4xcf9c

Author’s page: http://tinyurl.com/z83b72m

Published on January 02, 2017 09:01

Crockett Fought Odds in Washington, Tooby James R. Boylst...

Crockett Fought Odds in Washington, Tooby James R. Boylston and Allen J. Wiener

(Originally published in the Nashville, Tennessean, July 20, 2011)

Davy Crockett might not have “patched up the crack in the Liberty Bell,” but when he was in Congress, David Crockett was a fierce opponent of the partisanship that was fracturing Washington and, in Crockett’ s opinion, putting liberty at risk.

Born almost 225 years ago, on Aug. 17, 1786, Crockett would find that things haven’t changed much in Washington. Capitol Hill bubbled with as much bitter partisanship back then as it does today. Initially a supporter of President Andrew Jackson, Crockett quickly found himself at odds with Old Hickory and his party whip-crackers, including fellow Tennessean James K. Polk and New Yorker Martin Van Buren, both future presidents. The problem was that Crockett focused on the needs of the people who had elected him and would not compromise to please party bosses or even the highly popular president.

Throughout his six years in Congress, Crockett continually voiced his independence from any party when it conflicted with the interests of his constituents or put the nation in jeopardy. “The Stars and Stripes,” he warned, “must never give way to the shreds and patches of party.”

Crockett knew parties were not going away and was not entirely opposed to them, but, like many of the Founders, he was wary of them. “I am a party man in the true sense of the word,” he wrote, “but God forbid that I should ever become so much a party man as obsequiously to stoop to answer party purposes.” He saw the rise of political parties as a threat to the country, because politicians were bound to become more concerned with the success of their party than the greater good of the country.

Like Jefferson, Crockett believed democracy was best served by tying citizens closely to the government through their representatives. He defiantly insisted that “I cannot nor will not forsake principle to follow after any party and I do hope there may be a majority in Congress that may be governed by the same motive.” But it was a vain hope.

Once Crockett bucked the party bosses, he found himself on Jackson’s hit list for life.

In 1830, Crockett irritated both Jackson and his own congressional delegation by voting against the president’s brutal Indian-removal policy, which led to the Trail of Tears. Crockett was determined to follow his conscience, insisting that he had made “a good honest vote and one that would not make me ashamed in the day of judgment.”

Partisanship continued to infuriate Crockett, and he told a crowd in Baltimore that “I broke off with Jacksonism whenever I found I could not be a free man…. I got disgusted, and knew that the less you handle rotten eggs, the better chance you have of coming off with clean hands, so I cut loose.”

When a delegation from Mississippi asked his permission to nominate him for the presidency in 1834, Crockett recognized that it was not a realistic option for him, but responded anyway, saying “If I am elected, I shall just seize the old monster — Party —by the horns, and sling him right slap into the deepest place in the great Atlantic sea.”

Ultimately, Crockett’s independence cost him his seat in Congress, so he packed his bags and headed for Texas and, he hoped, greener pastures. Sadly, it was not to be. Within a few short months, rockett fell in defense of the Alamo and became the stuff of legend. While his sacrifice there should never be forgotten, his battle against injustice and political divisiveness provides an additional example we could do well to emulate.

Davy Crockett would feel very much at home on Capitol Hill today.

James R. Boylston and Allen J. Wiener are authors of David Crockett in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Poor Man’s Friend(Bright Sky Press).

Amazon.com Listing: http://tinyurl.com/j4xcf9c

Author’s page: http://tinyurl.com/z83b72m

(Originally published in the Nashville, Tennessean, July 20, 2011)

Davy Crockett might not have “patched up the crack in the Liberty Bell,” but when he was in Congress, David Crockett was a fierce opponent of the partisanship that was fracturing Washington and, in Crockett’ s opinion, putting liberty at risk.

Born almost 225 years ago, on Aug. 17, 1786, Crockett would find that things haven’t changed much in Washington. Capitol Hill bubbled with as much bitter partisanship back then as it does today. Initially a supporter of President Andrew Jackson, Crockett quickly found himself at odds with Old Hickory and his party whip-crackers, including fellow Tennessean James K. Polk and New Yorker Martin Van Buren, both future presidents. The problem was that Crockett focused on the needs of the people who had elected him and would not compromise to please party bosses or even the highly popular president.

Throughout his six years in Congress, Crockett continually voiced his independence from any party when it conflicted with the interests of his constituents or put the nation in jeopardy. “The Stars and Stripes,” he warned, “must never give way to the shreds and patches of party.”

Crockett knew parties were not going away and was not entirely opposed to them, but, like many of the Founders, he was wary of them. “I am a party man in the true sense of the word,” he wrote, “but God forbid that I should ever become so much a party man as obsequiously to stoop to answer party purposes.” He saw the rise of political parties as a threat to the country, because politicians were bound to become more concerned with the success of their party than the greater good of the country.

Like Jefferson, Crockett believed democracy was best served by tying citizens closely to the government through their representatives. He defiantly insisted that “I cannot nor will not forsake principle to follow after any party and I do hope there may be a majority in Congress that may be governed by the same motive.” But it was a vain hope.

Once Crockett bucked the party bosses, he found himself on Jackson’s hit list for life.

In 1830, Crockett irritated both Jackson and his own congressional delegation by voting against the president’s brutal Indian-removal policy, which led to the Trail of Tears. Crockett was determined to follow his conscience, insisting that he had made “a good honest vote and one that would not make me ashamed in the day of judgment.”

Partisanship continued to infuriate Crockett, and he told a crowd in Baltimore that “I broke off with Jacksonism whenever I found I could not be a free man…. I got disgusted, and knew that the less you handle rotten eggs, the better chance you have of coming off with clean hands, so I cut loose.”

When a delegation from Mississippi asked his permission to nominate him for the presidency in 1834, Crockett recognized that it was not a realistic option for him, but responded anyway, saying “If I am elected, I shall just seize the old monster — Party —by the horns, and sling him right slap into the deepest place in the great Atlantic sea.”

Ultimately, Crockett’s independence cost him his seat in Congress, so he packed his bags and headed for Texas and, he hoped, greener pastures. Sadly, it was not to be. Within a few short months, rockett fell in defense of the Alamo and became the stuff of legend. While his sacrifice there should never be forgotten, his battle against injustice and political divisiveness provides an additional example we could do well to emulate.

Davy Crockett would feel very much at home on Capitol Hill today.

James R. Boylston and Allen J. Wiener are authors of David Crockett in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Poor Man’s Friend(Bright Sky Press).

Amazon.com Listing: http://tinyurl.com/j4xcf9c

Author’s page: http://tinyurl.com/z83b72m

Published on January 02, 2017 09:01

December 29, 2016

Why The Beatles?

Why The Beatles?by Allen J. Wiener

Could any other group draw a crowd as big as the one that congregated around "The Beatles Anthology"? Probably not, or at least not for six to 10 hours of visuals and sound, particularly since the Beatles created it out of little more than a bunch of old recordings and film clips - unused "rough drafts", if you will. But then, the Beatles were never like anyone else. From the very beginning they looked, sounded, sang and acted differently from all who had gone before. Only Elvis had so personally revolutionized pop music.

There can be no doubt that the Beatles are exactly what Billboard's Joel Whitburn has called them -- "The world's #1 rock group" -- and his facts and figures demonstrate their Olympian status: more U.S. number one singles, albums, and gold singles than any act in history; second only to Elvis Presley on Billboard's list of top 100 singles artists since 1955; second in total top 10 hits; top album artists of the rock era; and by far the biggest sellers in the 1960s, all within a recording career of less than eight years. In that brief time, the Beatles released some 213 songs, about 26 per year, something that would overwhelm contemporary artists. And most of those songs have stood the test of time quite well.

Just before "Anthology" was televised, Forbes predicted that the Beatles would earn more than $100 million in 1995, and money is certainly one potent measure of the group's sustained drawing power and sales potential. After ABC-TV had paid $20 million for "Anthology" broadcast rights, the network sold 80 percent of the series' commercial slots in less than three weeks at premium prices, with thirty-second spots commanding fees over $300,000. At the time, Apple expected to realize $75 million from "Anthology" television broadcasts alone. Even recycling the original Beatles albums in their present compact disc editions earns the group an estimated $12 million annually.

No one, not even George Martin, who helped create their music, can articulate what is so special about the Beatles. Nor is it easy to explain why their mystique continues to grow, recruiting new fans with each generation. Perhaps the timeless fascination with the Beatles and their music defies explanation, but a few factors do shed some light on the group's lasting appeal.

· The Beatles redefined the parameters of rock and roll music and demonstrated that its possibilities were limitless. Once albums like "Rubber Soul," "Revolver," and "Sgt. Pepper" conquered the charts it was clear that rock and roll could be just about anything that anyone wanted it to be. The Beatles may have been partially shaped by Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Chuck Berry, but they did not confine themselves to that early form of teen rock and roll for very long. As those pioneers had captured the frivolous teenage spirit of the fifties, the Beatles bent and shaped their music to match the mood of '60s youth, which had moved from the malt shop and teen hop to the more dangerous battlefields of sit-ins and political demonstrations.

· The Beatles revolutionized studio recording methods, proving that there was no sound, mood or effect that could not be achieved if all possibilities were explored. Today, many of those innovations are taken for granted, but the Beatles had to imagine or invent them on the fly. "We didn't have any magic or electronic boxes to plug into," their engineer Geoff Emerick points out. "We had to make it all mechanically ourselves. Most of the gadgets you can buy today are just based on the things we used to do mechanically. The artificial double tracking and the flanging and all that sort of stuff." The Beatles added their own experimental innovations, including endless tape loops that combined multiple layers of sound, backward effects, and the introduction of instruments like the sitar, the mellotron and the synthesizer. They did not hesitate to bring any instrument or musician into their sessions, whether it was a lone horn player, a string quartet, or a full symphony orchestra. After the Beatles, the only limitations were those of imagination, creativity and effort. The Beatles even managed to break the long-standing three-minute time limit rule that had applied to virtually all previous hit singles by clocking in with the 7:11 "Hey Jude." And, along the way, they invented the modern outdoor stadium concert.

· The Beatles seldom, if ever, repeated themselves. Unlike many rock and roll singers who preceded them, they did not attempt to continually recycle the sound or "formula" of their first hit over and over, a mindless strategy that was followed by far too many artists and producers in the '50s and early '60s, and which spawned a legion of one-hit wonders. Each new Beatles record, particularly after their first two albums, showed significant creative growth.

· The Beatles "died young" by calling it quits while still at their peak. They didn't dwindle down to a second- or third-rate act. Despite 25 years of solo work, they are still frozen in that 1960s image, the top group in the world with lots of remaining potential, albeit unrealized - enough to fuel decades of "what ifs."

· The Beatles' music has been made more special by the group's lasting breakup. When they closed shop at Abbey Road in 1970, it was really for good. There was no reunion album, no reunion concert, no one-off charity gig. When Lennon died in 1980, all chance of a real reunion died too. Fans may enjoy "Free As A Bird," but the Beatles can never really come together again. That leaves a finite body of work comprising 13 albums and 22 singles that represent all of the real music the Beatles ever produced together for public consumption. The "Anthology" packages of outtakes, demos, and home recordings lends insight into the creation of that music, but does not really enhance it. That finite status adds a special preciousness to the Beatles' music.

The closer one gets to the Beatles' sessions, the more elusive is an explanation for their longevity. Those who worked most intimately with them seem unable to resolve it. Allan Rouse, the EMI archivist who worked on both the "Live At The BBC" and "Anthology" projects with George Martin, is similarly stuck for an explanation. "I've heard that question asked of far better qualified people than me, and even George Martin has struggled to come up with an answer. The simple fact is that great music lasts forever."

The Beatles were extremely creative artists, and the combination of their four personalities gave rise to a rare studio environment that none of them could later duplicate individually, nor has any succeeding group recaptured it. More than anything else, it is the lasting quality of the Beatles' music that accounts for their continued magnetism. "It's the songwriting," Emerick agrees. "Like Cole Porter and Gershwin - it's just there forever. I don't think we'll be playing Oasis' stuff in 30 years, but we'll be playing Gershwin and Cole Porter and Lennon-McCartney."

And Emerick believes that there was an intangible magic to those sessions. "Whenever they are in a room together there's just an energy there, and I guess that's really the only word I can use to explain that." Emerick witnessed the same thing when Harrison, McCartney and Starr returned to the studio to work on "Free As A Bird." "We hadn't been in the same room together for 25 years, and it was just like it had been a week ago. We just carried on recording."

Author's Facebook Page: http://tinyurl.com/pofg47vAuthor's Amazon Page: http://tinyurl.com/po638bd

Could any other group draw a crowd as big as the one that congregated around "The Beatles Anthology"? Probably not, or at least not for six to 10 hours of visuals and sound, particularly since the Beatles created it out of little more than a bunch of old recordings and film clips - unused "rough drafts", if you will. But then, the Beatles were never like anyone else. From the very beginning they looked, sounded, sang and acted differently from all who had gone before. Only Elvis had so personally revolutionized pop music.

There can be no doubt that the Beatles are exactly what Billboard's Joel Whitburn has called them -- "The world's #1 rock group" -- and his facts and figures demonstrate their Olympian status: more U.S. number one singles, albums, and gold singles than any act in history; second only to Elvis Presley on Billboard's list of top 100 singles artists since 1955; second in total top 10 hits; top album artists of the rock era; and by far the biggest sellers in the 1960s, all within a recording career of less than eight years. In that brief time, the Beatles released some 213 songs, about 26 per year, something that would overwhelm contemporary artists. And most of those songs have stood the test of time quite well.

Just before "Anthology" was televised, Forbes predicted that the Beatles would earn more than $100 million in 1995, and money is certainly one potent measure of the group's sustained drawing power and sales potential. After ABC-TV had paid $20 million for "Anthology" broadcast rights, the network sold 80 percent of the series' commercial slots in less than three weeks at premium prices, with thirty-second spots commanding fees over $300,000. At the time, Apple expected to realize $75 million from "Anthology" television broadcasts alone. Even recycling the original Beatles albums in their present compact disc editions earns the group an estimated $12 million annually.

No one, not even George Martin, who helped create their music, can articulate what is so special about the Beatles. Nor is it easy to explain why their mystique continues to grow, recruiting new fans with each generation. Perhaps the timeless fascination with the Beatles and their music defies explanation, but a few factors do shed some light on the group's lasting appeal.

· The Beatles redefined the parameters of rock and roll music and demonstrated that its possibilities were limitless. Once albums like "Rubber Soul," "Revolver," and "Sgt. Pepper" conquered the charts it was clear that rock and roll could be just about anything that anyone wanted it to be. The Beatles may have been partially shaped by Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Chuck Berry, but they did not confine themselves to that early form of teen rock and roll for very long. As those pioneers had captured the frivolous teenage spirit of the fifties, the Beatles bent and shaped their music to match the mood of '60s youth, which had moved from the malt shop and teen hop to the more dangerous battlefields of sit-ins and political demonstrations.

· The Beatles revolutionized studio recording methods, proving that there was no sound, mood or effect that could not be achieved if all possibilities were explored. Today, many of those innovations are taken for granted, but the Beatles had to imagine or invent them on the fly. "We didn't have any magic or electronic boxes to plug into," their engineer Geoff Emerick points out. "We had to make it all mechanically ourselves. Most of the gadgets you can buy today are just based on the things we used to do mechanically. The artificial double tracking and the flanging and all that sort of stuff." The Beatles added their own experimental innovations, including endless tape loops that combined multiple layers of sound, backward effects, and the introduction of instruments like the sitar, the mellotron and the synthesizer. They did not hesitate to bring any instrument or musician into their sessions, whether it was a lone horn player, a string quartet, or a full symphony orchestra. After the Beatles, the only limitations were those of imagination, creativity and effort. The Beatles even managed to break the long-standing three-minute time limit rule that had applied to virtually all previous hit singles by clocking in with the 7:11 "Hey Jude." And, along the way, they invented the modern outdoor stadium concert.

· The Beatles seldom, if ever, repeated themselves. Unlike many rock and roll singers who preceded them, they did not attempt to continually recycle the sound or "formula" of their first hit over and over, a mindless strategy that was followed by far too many artists and producers in the '50s and early '60s, and which spawned a legion of one-hit wonders. Each new Beatles record, particularly after their first two albums, showed significant creative growth.

· The Beatles "died young" by calling it quits while still at their peak. They didn't dwindle down to a second- or third-rate act. Despite 25 years of solo work, they are still frozen in that 1960s image, the top group in the world with lots of remaining potential, albeit unrealized - enough to fuel decades of "what ifs."

· The Beatles' music has been made more special by the group's lasting breakup. When they closed shop at Abbey Road in 1970, it was really for good. There was no reunion album, no reunion concert, no one-off charity gig. When Lennon died in 1980, all chance of a real reunion died too. Fans may enjoy "Free As A Bird," but the Beatles can never really come together again. That leaves a finite body of work comprising 13 albums and 22 singles that represent all of the real music the Beatles ever produced together for public consumption. The "Anthology" packages of outtakes, demos, and home recordings lends insight into the creation of that music, but does not really enhance it. That finite status adds a special preciousness to the Beatles' music.

The closer one gets to the Beatles' sessions, the more elusive is an explanation for their longevity. Those who worked most intimately with them seem unable to resolve it. Allan Rouse, the EMI archivist who worked on both the "Live At The BBC" and "Anthology" projects with George Martin, is similarly stuck for an explanation. "I've heard that question asked of far better qualified people than me, and even George Martin has struggled to come up with an answer. The simple fact is that great music lasts forever."

The Beatles were extremely creative artists, and the combination of their four personalities gave rise to a rare studio environment that none of them could later duplicate individually, nor has any succeeding group recaptured it. More than anything else, it is the lasting quality of the Beatles' music that accounts for their continued magnetism. "It's the songwriting," Emerick agrees. "Like Cole Porter and Gershwin - it's just there forever. I don't think we'll be playing Oasis' stuff in 30 years, but we'll be playing Gershwin and Cole Porter and Lennon-McCartney."

And Emerick believes that there was an intangible magic to those sessions. "Whenever they are in a room together there's just an energy there, and I guess that's really the only word I can use to explain that." Emerick witnessed the same thing when Harrison, McCartney and Starr returned to the studio to work on "Free As A Bird." "We hadn't been in the same room together for 25 years, and it was just like it had been a week ago. We just carried on recording."

Author's Facebook Page: http://tinyurl.com/pofg47vAuthor's Amazon Page: http://tinyurl.com/po638bd

Published on December 29, 2016 17:40

April 6, 2015

Leonardo vs. Michelangelo

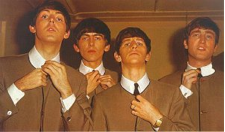

Leonardo da Vinci & Michelangelo Buonarroti

The Lost Battles: Leonardo, Michelangelo and the Artistic Duel That Defined the Renaissanceby Jonathan Jones

Review by Allen J. Wiener

Renaissance artists were often treated like rock stars and crowds of admirers would flock to see even a preliminary sketch, or cartoon, of their works in progress. They often had egos to match their adulation and bitter competition between them, including the occasional personal insult, was not uncommon. None of them were bigger or brighter stars than Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti, who actually engaged in a direct competition of the stars in Florence five hundred years ago.

The Lost Battles is an entertaining account of this lesser-known episode intersecting the lives of the two greatest artistic giants of the Renaissance. The occasion was a contest between the two to paint representations of two battles in Florence's history on the walls of the Great Council Hall. The competition was arranged by Niccolò Machiavelli, chief advisor to the head of state, who sought to stimulate patriotism among Florentines. Leonardo was to take on the Battle of Anghiari; Michelangelo the engagement at Cascina, glorifying these Florentine victories of 1440 and 1364 respectively. Neither painting would be completed.

Peter Paul Rubens’ copy of The Battle of Anghiari

Michelangelo did not progress beyond what was apparently a magnificent cartoon of the proposed painting, which was viewed and admired almost as much as some of his greatest completed works. Leonardo's cartoon was similarly applauded and admired and he did at least make a start on the painting itself. Thus, much of the author's evaluation of the works is based on contemporary descriptions, fragments of the works that survived, for example in Leonardo's many notebooks, and copies that were painted by others. Through this method, the author is able to draw conclusions about the artists' motivations and intentions.

Even those of us not schooled in art history or technique will find the author's descriptions and comparisons of the two works interesting, especially the influence that Leonardo and Michelangelo had on each other, despite their bitter rivalry. And bitter it was. According to this account, the two could barely stand the sight of each other, but the author presents a good case for this reflecting the deep admiration, not to say envy or threat they felt from each other. It also was common practice at the time for artists of their stature and reputation to openly denigrate and even insult one another. In a weird sort of way, it was an indication of respect.

Copy of the Battle of Cascina by Michelangelo's pupil Aristotele da Sangallo

The author offers additional insight into the roots of their differences through an analysis of what kind of people they were, beyond their artistic and, in the case of Leonardo, scientific achievements. Michelangelo the devoted Florentine patriot and deeply religious individual, who gives allegiance to church and state; Leonardo the religious skeptic and scientist, who sees little reason for political loyalty to mercurial, temporal rulers who might solicit his work and advice, only to later abandon him. In this telling, life for Leonardo was about exploring and experimenting and finding the truth.

Perhaps the most glaring difference between the two artists is their respective legacies. One of them, the Last Supper, is a magnificent ruin, its colors faded long ago due to Leonardo's own miscalculation in the method he chose to use on the wall where the painting remains. His Mona Lisa, which he kept with him until his death, remains a mesmerizing enigma and achievement enough for a lifetime for most artists, but few completed works by da Vinci survived, largely because he completed so few and often abandoned his projects. Michelangelo, on the other hand, left a world of magnificent creations that include the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the breathtaking David, at least two pietas, his Moses in the tomb of Pope Julius II, among others.

The author makes insightful observations about the two men that explain why they left such different legacies. This is most helpful in understanding Leonardo, who found it difficult to complete works and was often distracted by diverse pursuits, even engaging in an experiment in human flight while at work on the Battle. Although few da Vinci works survive, his voluminous notebooks contain a wealth of insight into his mind and undying curiosity about nature and science, his designs for war machinery, sketches of contemplated art works, and inventions. Politics of the time, which favored Michelangelo's work as more in tune with popular feelings, also played a role in the contemporary responses to the two painters' respective works. Jones also finds Michelangelo’s work a breakthrough from the past, while he views Leonardo's technique as anachronistic and less patriotic than Michelangelo's, which he regards as important factors at the time.

Readers may quibble with some of the author's speculations and conclusions regarding the feelings and motivations of the two artists, but his thorough research and expertise in art history lend weight to those ideas. This is one of the most enjoyable and accessible books on these two giants and, although focused on a single event in their lives, uncovers much about them and their work beyond that encounter.

Published on April 06, 2015 10:54

February 24, 2015

David Crockett Defends Native Americans

David Crockett’s opposition to President Andrew Jackson’s 1830 Indian Removal Bill was one of the highpoints in his long, often contentious political career. As a Tennessean, Crockett did not make things easy for himself by repeatedly bucking Jackson, the state’s most celebrated hero and popular politician. Yet Crockett managed to win three terms in Congress, losing two close elections, before packing it in and telling his constituents that they might all go to Hell and he would go to Texas. He made good on the promise and met his death at the Alamo on March 6, 1836, in Texas’ war for independence from Mexico.

Crockett’s speech opposing Indian Removal was included in “Davy Crockett Goes to Congress”, the second episode in Walt Disney’s three-part TV mini series that aired on “Disneyland” in 1954-55. Portrayed by Fess Parker, Crockett gives an angry, rousing speech aimed at shaming the Congress for even considering such an unjust measure. Parker dramatically tears his copy of the bill in half before storming out of the House chamber to rousing applause.

Fess Parker in "Davy Crockett Goes To Congress"

Fess Parker in "Davy Crockett Goes To Congress"Of course, the speech was not quite so dramatic and was so short that it was not even included in the Register of Debates, the early 19th century version of today’s far more authoritative Congressional Record. This omission led Crockett scholars to conclude that he never really gave the speech and that he didn’t want his pro-removal constituency to learn that he had opposed Jackson’s bill. But Crockett actually boasted about the speech, was very proud of his stand, and aware that, had he tried to conceal the speech, his numerous political opponents would have seen that it was widely published in his district anyway.

The following excerpt from David Crockett in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Poor Man’s Friend, by James R. Boylston and myself, explains Crockett’s views on Indian Removal and his speech opposing it.

“Crockett’s support for the Indians and his vote against removal have often been seen as merely part of his consistently strong anti-Jackson stand and just one more swipe at Old Hickory, which lacked real commitment. This view of Crockett’s motives stems largely from the fact that the speech he gave in the House does not appear in the Register of Debates in Congress, suggesting to some that he tried to conceal his defense of Indians from voters. However, the speech was reported in the United States’ Telegraph and published elsewhere in full, including in the Jackson Gazette in Crockett’s home district, and it was mentioned or summarized in newspapers throughout the country. It also appeared in a compilation of speeches on Indian removal.

“Crockett read the reports about his speech in the press and took exception to the way it had been paraphrased in the Telegraph. He wrote to the newspaper to correct its errors, particularly the report that he had said ‘he was opposed in conscience to the measure; and such being the case, he cared not what his constituents thought of his conduct.’ Crockett denied having said anything of the kind and insisted ‘I never hurl defiance at those whose servant I am. I said that my conscience should be my guide. . . and that I believed if my constituents were here, they would justify my vote.’1The published speech actually paraphrased him as saying ‘He had his constituents to settle with, he was aware; and should like to please them as well as other gentlemen; but he had also a settlement to make at the bar of his God; and what his conscience dictated to be just and right he would do, be the consequences what they might. He believed that the people who had been kind enough to give him their suffrages supposed him to be an honest man, or they would not have chosen him. If so, they could not but expect that he should act in the way he thought honest and right.’2

“Crockett knew that he could not keep his vote or such a speech secret from his constituents, and he was keenly aware that his position on the issue was unpopular with many of them. Newspapers back home criticized his vote, and he defended it openly in his letters and circulars, which were widely read by his constituents. He also boasted proudly of his vote in his autobiography, published in 1834, and insisted that it was a matter of conscience and his obligation under the trust that voters had placed in him. ‘I had been elected by a majority of three thousand five hundred and eighty-five votes,’ he wrote, ‘and I believed they were honest men, and wouldn’t want me to vote for any unjust notion. . . . I voted against this Indian bill, and my conscience yet tells me that I gave a good honest vote, and one that I believe will not make me ashamed in the day of judgment.’3

“Apparently Crockett had even stronger words in support of the Indians that were cut from his original autobiography manuscript. According to John Gadsby Chapman, who painted Crockett’s portrait in mid- 1834, ‘There were, moreover, many portions of his manuscript, cancelled by the counsel of his advisers, that gave him special vexation—chiefly such relating to inhuman massacres of Indian women and children, which if he wrote of with half the intensified bitterness of reprobation that I have heard him express towards the perpetrators of such atrocious acts, and the officials by whom they were permitted, suppression of their narrative may have been better for the credit of the nation and humanity.’ 4

“Crockett continued to defend his vote even after he was defeated in his bid for reelection in 1831. Writing to a supporter in his district, he condemned Jackson on several counts and showed no regret for his vote in opposition to Indian removal, proclaiming that ‘I also condemned the Course parsued to the Southern Indians I love to sustain the honour of my Country and I will do it while I live in or out of Congress . . . .’5”

1 United States’ Telegraph, May 25, 1830. 2 Jackson (Tennessee) Gazette, June 26, 1830. 3 David Crockett, A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee, ed. and annotated by James A. Shackford and Stanley J. Folmsbee (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1973), 206. 4 Curtis Carroll Davis, “A Legend at Full-Length: Mr. Chapman Paints Colonel Crockett— and Tells About It,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 69 (1960), 169–70.5 Crockett to James Davison, August 18, 1831, DRT Library at the Alamo.

Allen J. Wiener's books can be found on Amazon.com: http://tinyurl.com/po638bd

Visit my Facebook page here: http://tinyurl.com/pofg47v

Published on February 24, 2015 07:19

February 5, 2015

Moses Rose of the Alamo!

The 1836 Battle of the Alamo is steeped in myth, rich in history, and a source of many unsolved puzzles. Countless written words and hours of debate have centered on the battle and its major figures, David Crockett, Jim Bowie, and commander William Travis.

The Alamo battle quickly ascended into myth and legend. Fictionalized and glorified images of the defenders, as well as the demonization of their Mexican adversaries, particularly General Santa Anna, have been preserved in poetry and fiction; on stage, screen and television; and in a considerable amount of music. Nearly all of these artistic representations reflect the traditional image of the Alamo heroes as brave martyrs who went down fighting for Texas independence from Mexico. Little negative is ever said about them, but on rare occasions some bold wag has held a more cynical or comical lens up to the Alamo myth. Take Moses Rose for example, whose name may actually have been Louis Rose, who may or may not have been French, but who certainly fought at the Alamo and, unlike his fellow defenders, lived to tell about it.

At some point during the siege, so the story goes, Colonel Travis gave the garrison the option of leaving the fort with honor or remaining with him to fight to the death, which was a certainty by the time he made the offer. Legend has it that only one man, Rose, chose to bolt over the wall and attempt escape through Mexican lines. Although the story has met with some skepticism, Rose does appear to have fought at the Alamo and managed to escape before the final battle. Thus, no stigma of cowardice should haunt Rose’s memory (after all, Travis did give the garrison permission to leave with honor) but, nonetheless, history has sometimes judged him to be “less-than-heroic”.