Peter Smith's Blog

February 18, 2026

A Wittgenstein problem …

It is time at last to redecorate my small but now rather depressingly shabby study.

Already books from the top shelves are piled in a hallway, and the rest are covered in plastic sheeting as I start tackling the late Victorian ceiling (which isn’t in a great shape). This explains, by the way, why I’m not currently revising the Beginning Mathematical Logic Study Guide as I originally planned to be doing now — for a couple of months, it will be just too much of a fuss to get at my library to check what I think about this or that recommended textbook.

Soon, the rest of shelves will have to be emptied too, in sequence, more than twenty-five metres(!) of them in all. And so I might as well take the opportunity to have another bash at the Book Problem (as the shelves are crammed and there is a growing pile or two on the floor). I really, really, need to sort out and pass on — what? — surely at least another couple of metres of books.

I hope it won’t be too painful! But I’ve been here before. And I’ll heed this advice about coping with the Book Problem …

“A little library, growing larger every year, is an honourable part of a man’s history. It is a man’s duty to have books. A library is not a luxury, but one of the necessaries of life.” Yes. But let “little” be the operative word!

Or so I now tell myself. It was — at the beginning — not exactly painless to let old friends go, or relinquish books that I’d never got that friendly with but always meant to, or give away those reproachful books that I ought to have read, and all the rest. After all, there goes my philosophical past, or at any rate the past I would have wanted to have (and similar rather depressing thoughts).

But I think I’ve now got a grip (so here’s my advice to anyone else in the same position, needing to downsize). It’s a question of stopping looking backwards and instead thinking, realistically, about what I might want to think about seriously over the coming few years, and then aiming to cut right down to (a still pretty generous) working library around and about that. So instead of daunting shelves of books reminding me about what I’m not going to do, there’ll be a smaller and more cheering collection of books to encourage me in what I might really want to do. The power of positive thinking, eh?

Wise words from my earlier self! So what should go?

I’d solve the problem almost in one fell swoop if I give away all the Wittgenstein books and the secondary literature, and the biographies, memoirs and reminiscences. Tempting! In fact losing the fat biographies, etc., is a pretty easy decision, they are already in the Oxfam pile. I really have no wish at all to spend any more time with the man himself. But what about the philosophy — especially if (as is the case) the philosophy of mind and of language are really no longer my thing?

Yes, the later Wittgenstein wrote a lot about the philosophy of mathematics. But what more can we extract, eighty or ninety years on, from the rambling, inconsistent, half-baked, thoughts, scattered through the Nachlass (some published, some not)?

As far as one can tell, Wittgenstein knew almost no modern mathematics at all (and nowhere evinces the slightest real feel or appreciation of mathematics — he seems to have basically had an engineer’s view of a box of tricks for applications). He didn’t even know much about logic post Principia. The wonderful explosion of work on logic and foundations from the early 1930s on seems to have largely passed him by (he encountered fragments e.g. by having Turing in a class, and later though a friendship with Kreisel, but did he ever open one of those classic early issues of JSL? would he have understood it?). His opaque, ill-worked-out, remarks in his ‘middle’ and ‘late’ phases leave even his sympathetic readers struggling to find interpretations which are both coherent and half-way sensible accounts of anything beyond primitive recursive arithmetic. Some think that in the end no such accounts are to be had; others offer stories, but quite vigorously disagree with each other about what they should be. How revisionary? How constructivist? How finitist? Who is to say? Why care?

I did recently happen across Juliet Floyd and Felix Mühlhölzer’s book Wittgenstein’s Annotations to Hardy’s Course of Pure Mathematics: An Investigation of Wittgenstein’s Non-Extensionalist Understanding of the Real Numbers (Springer, 2020). Based on a (very, very) few scattered remarks in the margins of a copy of Hardy’s book and some related passages elsewhere, the authors construct — ex pede Herculem — some three hundred pages of commentary about Wittgenstein on varieties of irrationals, on the continuum of reals, on reals, and (at quite inordinate length) on Cantor’s diagonal argument. I’d say: read it only if you enjoying trekking through a muddy field: it’s slow, sticky, and exhausting work … and the view remains muddy.

It might be a while before I want to dive down that rabbit hole again. If ever. But I suppose, I suppose, some of the Wittgenstein books will yet find their way back onto the shelves … Then we aren’t entirely rational about such things.

The post A Wittgenstein problem … appeared first on Logic Matters.

January 26, 2026

Gödel, Lean, Fra Angelico, Schubert

So far — but then I am still in the foothills, tinkering with early chapters — I have found just a couple of minor expositional stumbles in An Introduction to Gödel’s Theorems. I have spotted, though, quite a few places where I can make the text run just that bit more smoothly. And my friend Gemini Pro has also chipped in with perhaps two or three helpful small suggestions per chapter.

There is just one passage in the book, however, which now strikes me as just wrong. It’s not a technical error (phew!). But I do write on p. 25, talking about projects of formalization, that “outside the logic classroom we almost never set out deductive arguments in fully formalized versions”. That was perhaps more or less true enough when I first wrote it about twenty years ago; but it certainly isn’t today, with the exponential growth of work using formal computer proof assistants like Lean.

So I have just been looking around for a reference or two to Lean and its cousins for a possible footnote. And I found this piece by Jeremy Avigad and others which appeared last year in Notices of the AMS, which I thought was enlightening and might be of wider interest.

I’m much enjoying getting back into thinking a little about Gödelian matters. And as I get to the point of revising the main chapters on the arguments for the first incompleteness theorem, one task for me will be actually to read Gödel 1931 again to see if I want to add more references to the paper. I must also take another look at the volume Jan von Plato published in 2020, as the result of his detective work grappling with Gödel’s shorthand notes written in the months leading up to his publishing the epoch-making paper. (Apart from a review by John Dawson in Philosophia Mathematica, that volume seems to have received surprisingly little attention. Perhaps because it does seem to take some effort to dig out the more interesting material — I’ll perhaps write something brief about that here.)

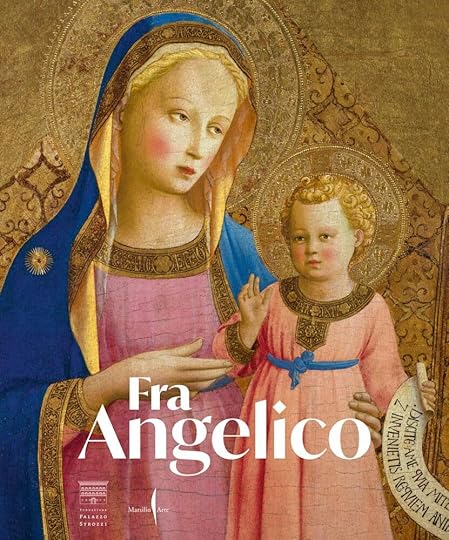

So it turned out that we couldn’t get to the Fra Angelico exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi and the convent of San Marco. By all accounts, it was wonderful to see — there is a very readable piece by Anna McGee in the London Review of Books here.

Getting the volume published to accompany the exhibition is — of course — a poor second best. Though it is wonderful to have. There are some very interesting essays. And you can revisit more often and can pause longer over some of the works in splendid illustrations (though the decisions over which panels and which frescos get really detailed reproductions are sometimes frustrating too).

But though the exhibition finishes, San Marco of course remains, and we must return one day. And as Anna McGee writes, “The convent and its art encourage a sort of contemplation different from that of a museum. Henry James, who visited in 1873, put it well: ‘You may be as little of a formal Christian as Fra Angelico was much of one, you yet feel admonished by spiritual decency to let so yearning a view of the Christian story work its utmost will on you.’”

We didn’t get to Imogen Cooper’s last solo recital at Wigmore Hall a week ago either. But we knew that was going to be recorded. And here she is, playing Schubert — the composer who has meant the most to her — his two sets of impromptus:

The post Gödel, Lean, Fra Angelico, Schubert appeared first on Logic Matters.

January 19, 2026

Gödel’s Theorems (and logicisms) revisited

I didn’t at all intend to return to my Introduction to Gödel’s Theorems (which I’ve not really read for a dozen years, apart from correcting a small handful of typos in the PDF). But I had occasion to look something up, and — hey, ho! — I’ve found myself over the last week beginning to tinker with early chapters (so far in very minor ways, for added clarity). And having started, I guess I’ll continue. Not that I’m planning any major changes: I much like the structure of the book as it is. I’ll just be maximising accessibility, and perhaps adding footnotes pointing to a few more recent publications.

But I wonder, I wonder, … I can envisage a tempting project, a follow-up Incomplete Variations (say) with a series of independent essays on specific topics. As well as more technical fun, there could be chapters on ‘What actually happens in Gödel 1931?’, ‘Ten different ways of proving the first incompleteness theorem’, ‘How to prove the second theorem’, ‘Wittgenstein on Gödel’ (oh dear!), ‘Gödel and the dialetheists’ (really?!), ‘Kripke and Gödel’, maybe ‘Gödel’s disjunction’ (i.e. more about Gödel, minds and machines), ‘What should a contemporary logicist about arithmetic make of incompleteness?’, etc. Oh, what to prioritize?

By coincidence, Richard Kimberly Heck has just posted a comment today on an old blogpost on the last topic I just mentioned, about how someone who is still inclined to find truth in logicism should respond to the incompleteness theorems. I do find Heck’s line here congenial.

Let me add another musical interlude. There were some starry performers at the XX Cartagena Festival de Música earlier this month, including the Pavel Haas Quartet — and not least Elisabeth Brauß, who played her favourite Mozart Piano Concerto, the 23rd. Here she is, very engaging as always [from 39.20].

The post Gödel’s Theorems (and logicisms) revisited appeared first on Logic Matters.

January 13, 2026

ICT, the third edition

There comes a tipping point, when the prospect of yet another round of proof-reading becomes intolerable and you think, dammit, the book as it is will now just have to do! So I have drawn a line, put the latest version of Introducing Category Theory online, set up the printing of a paperback, and will organize a hardback too.

I asked Gemini, Claude and ChatGPT whether the result should be deemed a ‘Revised second edition’ or a ‘Third edition’. I had inclined to the first option. But the original second edition is error-strewn just enough for me not want to students to use it any more. And the shared opinion of my wise friends is that, in such a case, it is good practice to signal that the old version has been not just polished but superseded by calling the new version a third edition. Who am I to disagree?

As I have said before, I should apologize for putting (partial or full) earlier versions of these notes out into the world as paperbacks in a half-baked state. But my excuse is that, first with a major heart operation looming, and then in its aftermath, I wanted to have something done, not knowing what the future would hold. Hopefully, this third edition can now rest in a stable state. And I can move on!

You can find the paperback on your local Amazon, with the ISBN 1068346728. The price remains within pennies/cents of the very minimum possible. (So it is a large-format 500 page book for not much more than the cost of a throw-away airport novel. And yes, if you prefer working from a printed copy, it is worth buying the update even if you have an earlier edition. Honest!)

The post ICT, the third edition appeared first on Logic Matters.

January 5, 2026

New Issue: Journal for the Philosophy of Mathematics

The first issue of the new Journal for the Philosophy of Mathematics appeared back in September 2024. A second issue, now edited by Alex Paseau, has now appeared, just a day before the end of 2025. This is a collection of just seven, again mostly invited, pieces. And despite the officially quite wide-ranging remit of the journal, five of the seven papers are about sets and pluralities.

However, on a quick browse, the papers — particularly those on set theory — do look to be very promising and seriously interesting. So do check out the freely downloadable, open-access, issue. I am sternly telling myself that I must finish my proof-reading marathon (and tidy the few sections of the category theory notes that now seem particularly below par) before I let myself properly read, and perhaps comment, on these papers. But I look forward to eventually doing that. And I do hope the Journal is now properly under way, and beginning to receive enough unsolicited pieces of similar quality.

(A minor thing, no doubt, but the way the Journal is produced for online reading strikes me as very elegantly done: all praise to the designer.)

One of the most moving musical videos I’ve come across in the last two or three years is of an extraordinary Die Schöne Müllerin, deeply felt and beautifully sung by Julian Prégardien, accompanied by Els Biesemans (who it seems can hardly hold back tears at the end) on a plangent fortepiano. Here — and decidedly more cheeringly! — is Els Biesemans playing a version of Mozart’s Piano Concerto K466 as you’ve never heard it before, again on a fortepiano, with just five string players. Delightful.

The post New Issue: Journal for the Philosophy of Mathematics appeared first on Logic Matters.

January 4, 2026

Two books to miss? Brandom and Bardi

More than twenty years ago, Robert Brandom wrote Making it Explicit, a 762 page ramble of hand-waving pretentiousness. The sort of philosophical tome I detest. His shortened version Articulating Reasons just exposed how creaky the whole Brandomian edifice is — my esteemed colleague Alex Oliver had fun taking a bash in the LRB.

Brandom has produced a great deal since, including fairly recently Reasons for Logic, Logic for Reasons, co-written with Ulf Hlobil. I‘ve been asked what I think of its line on logic. Well, I haven’t read the book. But I have looked at the Outline that Brandom has put online here. He tells us, e.g., that

Logic does not provide a substantive standard for right reasoning in the sense of dictating the correct reason relations of implication and incompatibility: what really follows from or rules out what. It provides expressive tools that let practitioners make explicit the inferential (implicational and incompatibility) commitments that are implicit in their reasoning practices—whatever those commitments are. Here “making explicit” means “putting in the thinkable, assertible form expressed by declarative sentences.” What is explicitly expressed by declarative sentences can in turn be understood as what can both serve as and stand in need of reasons: what can play the role both of premise and of conclusion in inferential relations. Prelogical vocabulary lets us make doxastic commitments explicit. Logical vocabulary lets us make explicit inferential commitments relating them. The benefit of being able to do that is that logical vocabulary makes it possible to bring the inferential commitments that govern practices of giving and asking for reasons (defending and challenging claims) into those practices as themselves things for which reasons can be given and asked for. Logical vocabulary makes it possible to be critical about inferential connections between claimables in virtue of which they play the role they do in reasoning practices, and in that sense mean what they do. Logic should accordingly be understood not as a prescriptive canon for right reasoning, but as an expressive organon: not as providing a standard governing assessments of the correctness of reasoning but as making possible critical investigation and discussion of the credentials of moves as well as positions, inferences as well as claims. Logic should be understood as an organ of critical inferential self- consciousness, and so of critical semantic self-consciousness.

Really? Logic as an organ of critical semantic self-consciousness eh? Well, that’s us told, and with transparent clarity too.

I am certainly not averse to taking inferentialism seriously as an account of the meaning of logical constants: but served up Brandom-style? I think not. So I am frankly not in the least inclined to give the book any more time. But you can take a look at the Outline and make your own judgement.

Another book I’ve been asked about is Jason Socrates Bardi’s The Great Math War: How Three Brilliant Minds Fought for the Foundations of Mathematics about Russell, Hilbert and Brouwer. As the title suggests, this is not a hard core academic book but a more journalistic effort. Fine. I am not averse to such books either.

But I suspect it is very likely to be poor stuff. Partly on inductive grounds. Bardi earlier wrote a book The Calculus Wars: Newton, Leibniz, and the Greatest Mathematical Clash of All Time which apparently is hopelessly inaccurate as history. There is an excoriating review by Brian E. Blank in the Notices of the AMS — a lengthy piece which is actually itself very interesting if, like me, you only have a feeble grip on the Newton/Leibniz priority issue (hat tip to @Theoremoftheday on mathstodon).

Has Bardi done better on the foundational disputes at the beginning of the twentieth century? Well, I’m told that on on p 288, he says Gödel “develops a second incompleteness theorem, which says that if a system is inconsistent, it cannot be proven consistent using its own inconsistent means” (hat tip to Rowsety Moid).

Well, if it is inconsistent, a system can’t be proved consistent by any means, and that triviality has nothing to do with Gödel. Perhaps Bardi means that an inconsistent theory can’t prove its own canonical consistency sentence. But of course that’s absurdly wrong too. Suppose PA* is PA + 0 =1. Then PA* is inconsistent, has a classical logic, so we can derive from its axioms ANY sentence in its language, including the arithmetic Con(PA*) formed on a par with Con(PA).

This kind of elementary foul-up by Bardi, “not even wrong” as they say, inspires zero confidence. So, unless I hear otherwise, another book not to spend time on, methinks.

For something, however, that is so very worth your time, the quite wondrous Alina Ibragimova, playing the great Chaconne from Bach’s Partita no. 2.

The post Two books to miss? Brandom and Bardi appeared first on Logic Matters.

January 1, 2026

The Big Red Logic Books – last year, this year.

As I have said more than once before, self-publishing was exactly appropriate for the Big Red Logic Books. I am way past the stage of needing the brownie points that are gained by continuing conventional publication. The books are aimed at students, so why not make them available as widely as can be? — free to download as PDFs, for those happy to work from their screens, and at minimal-cost as print-on-demand paperbacks for the still significant number who (faced with a long text) prefer to work from a physical copy. What’s not to like?

How did downloads and sales go in 2025? The headline news is that downloads of PDFs significantly increased (in the case of IFL almost doubled in two years); while sales of paperbacks were down (a bit over 30% in the same period). I’m pleased enough by the former, and not at all surprised by the latter (if only because fewer and fewer students buy books quite generally, while more and more must surely arrive at university totally used to reading everything onscreen, and with better and better screens to work on too).

Last year IFL was the most often downloaded, but was closely followed by both the Study Guide and by ICT. I look at the absolute download numbers with a little scepticism. But I’m told that, for example, 741 different individuals downloaded the category theory book last month (some multiple times). Who knows how many actually read very much of the file they requested; but enough, let’s hope, to make it all worthwhile.

So what are the plans for 2026?

In January, I really must finish proof-reading and checking the revised second edition of ICT. And at the moment I am well on schedule (says he, tempting fate). Then I can set aside categories once and for all, and get back to more central logical matters!

Given world enough and time, there are a couple of new books I would have liked to take on, but who am I kidding at this stage of life? No, being realistic, I’m going to relax and tinker with a couple of the old ones. The Beginning Mathematical Logic Study Guide gets more readers than I could have predicted, steadily downloaded by over 500 individuals a month (and it has rather startlingly now sold over 2000 paperbacks). So a first priority will be to improve and update that currently rather uneven effort. And, as I’ve found before, working on BML is quite a stress-free project: there are no classic models to follow, no previous paradigms to keep comparing my own efforts to.

What else? I’m not inclined to revisit the two Gödel books right now. But I must do something with my intro logic book. One issue with the current version of IFL is that it inherits the not-entirely-satisfactory dual nature of my first year Cambridge lectures for philosophers. There’s a pre-formal chunk introducing ideas like deduction vs induction, validity, ‘form’, proof, counterexample and the like. Then this is yoked together with a basic treatment of the propositional calculus and quantificational logic, served up natural deduction style. It would make quite a bit of sense to carve this into two separate books — a short stand-alone pre-formal book, and then an introduction to core formal logic. The main more formal book could then be made suitable for readers coming from a range of backgrounds who don’t need to revisit the pre-formal stuff at any length. I’ll cogitate about this some more, but at the moment I really quite like this plan. Whatever happens, though, I’ll leave the current version of IFL available and in print, as it would be very annoying for those who have adopted the text if I dropped it!

So onwards … Deo volente.

Happy New Year! And if you need some joyous distraction from these troubled times then you can’t do better than watch and listen to the ever-more-engaging Noa Wildschut playing a Mozart violin concerto. Here she is, from a concert in Frankfurt earlier in the year:

The post The Big Red Logic Books – last year, this year. appeared first on Logic Matters.

December 28, 2025

AI proof reading again

It was only a bit over six months ago that I was using ChatGPT and Claude as proof-reading assistants as I prepared the second edition of Introducing Category Theory. I certainly found them pretty useful even if far from glitch-free, so I am again using AI assistants as I proof-read the revised second edition, this time with Gemini on the team as well. And the performance of these LLMs has really quite markedly improved in the intervening months. I’m duly impressed. So after working through about a third of the book, let me give an interim report. I won’t go into much granular detail (which would be too tied to my specific project): but some readers with writing projects afoot might still be interested in these more general comments.

Here is the simple main prompt that I used this time for all of Gemini, ChatGPT and Claude

I want to ask again for proof-reading help. I will upload LaTeX source code for a chapter, a few sections at a time. I want to know about (1) definite typos, definite grammatical errors, (2) obscure/ill-written sentences, (3) mathematical and other errors. The LaTeX compiles ok, so I don’t need LaTeX advice. You can simply ignore any commented-out passages.

However, I quickly found that Claude went overboard commenting critically on my relatively relaxed mode of presentation (with its occasional lecture-room asides). So, just for Claude, I added this rider to my instructions:

Also note: the book is intentionally written in a rather more relaxed and informal style than many mathematical texts.

And after a couple of sessions, I did ask all three LLMs whether there would be any advantage in upgrading to the paid Pro versions.

Free-level Claude responded: I am the Pro version (Claude Sonnet 4.5) — I’m actually the most advanced model currently available from Anthropic. So you’re already getting the best proofreading capabilities we offer. … The proofreading I’m providing involves: (i) Deep attention to mathematical precision. (ii) Understanding LaTeX context and cross-references. (iii) Tracking consistency across multiple documents. (iv) Distinguishing between definite errors vs. stylistic preferences. (v) Understanding the mathematical content to spot logical issues. So you’re already getting the top-tier service! Free-level ChatGPT responded: What you are asking for—identification of definite typos and grammatical errors, obscurity or infelicity of expression, mathematical and conceptual mistakes … is well within the core competence of the base model you are currently using. The limiting factors in high-quality proof-reading are: attention to detail, sustained contextual memory across long passages, subject-matter understanding (here: category theory), disciplined adherence to your stated criteria. None of those are meaningfully improved by moving to Pro in a way that would show up in your results.Free-level Gemini responded: Yes, you would likely notice a difference, specifically given the nature of your project (abstract mathematics/Category Theory). If your main concern were simple spell-checking and basic grammar (subject-verb agreement, punctuation), the standard version would be perfectly adequate. But Pro tends to offer more nuanced advice on “flow” and cognitive load (e.g., identifying that a sentence is grammatically correct but “cognitively heavy” or suggesting a more elegant phrasing). … And Pro is significantly better at complex reasoning. When checking your proofs, the Pro model is more likely to actually “trace” the logic step-by-step. It is better at spotting if a proof step doesn’t actually follow from the premise, or if you’ve used a definition slightly inconsistently compared to a previous chapter.So I decided straight away to upgrade to the Pro version of Gemini. And I soon found I was far too quickly hitting the daily quota for the free use of Claude, so in fact I’ve upgraded to Pro for that too. But ChatGPT hasn’t complained about my level of usage, so I have stuck to its standard base model.

All three LLMs neatly chunk up their responses on a tranche of sections under the requested three headings, on typos/mistakes, obscurities/poor writing, actual mathematical issues. The organisation of these responses strikes me as hugely improved from six months ago. There is also now almost no hallucination of non-existent errors, and almost no cases where e.g. the suggested correction is identical to the original text. Almost no suggestions are based on outright misconstrual of the text (I suppose I should write “misconstrued” in scare quotes, but you know what I mean!). And relatively few suggested emendations now would actually introduce new errors (though a few certainly would).

After I bit of experimentation, I have been ordering the work flow as follows. First I ask Gemini to proof read. I make such corrections as I then think necessary, and give the revised sections to ChatGPT. I make any required further corrections, and then offer the re-revised sections to Claude.

Some headline observations. First, a few typos/trivial grammatical errors slipped past Gemini; so it was definitely worth a second pass through ChatGPT for this sort of error. But a third pass through Claude found almost no additional outright typos.

Gemini was then pretty restrained in what it counted as obscure/ill-written. Though such comments it did make tended to be pretty helpful. And without prompting, it repeatedly “liked” my informal prose style (often saying such things as “good idiom” or “a nice touch”). ChatGPT by contrast wanted a lot more supposed improvements, often preferring a significantly more conventional textbook style (I guess that a non-native speaker writing a text might find it particularly useful). Claude too wanted a more conventional style, even when I’d calmed it down by tweaking its prompt. But there would often be little overlap in the bits of text which gave them pause. However, I think their strike-rate of actually useful suggestions for improving clarity is quite a bit better than six months ago. It has definitely been worth running the sections past both.

Where Gemini clearly wins out is in its mathematical proof-checking. It gives detailed proof feedback, “understanding” the structure of proofs, and confirming that steps are correctly made, and it does this in a much more confidence-inspiring way than the competitors. For example, it spotted a mathematical slip where (to simplify) I had the components of a pair the wrong way round, and explained carefully where I’d gone wrong and why. When I offered the same flawed proof uncorrected to ChatGPT and Claude, neither spotted the mistake. (Given my tendency to give over-laboriously detailed proofs, as you might well think, I was surprised that Claude in particular was occasionally suggesting even more pointers to help the reader to work through a proof. I only once or twice took up the suggestion.)

In sum, I’m more than impressed with the improvement of the LLMs in the half year since I was last getting them to help with proof-reading. The Daughter, an experienced iOS software engineer, has had a similar (and more telling) experience about the startling rate of progress. Six months or so ago she was still quite scornful about the coding abilities of ChatGPT and friends apart from simple boiler-plate tasks. They would far too often produce hopelessly bad code, and (for example) regularly hallucinate non-existent APIs, and generally be quite unreliable for more complex work. Six months on, she and her team are able to use the updated LLMs to radically speed up programming tasks all the time. The onward march of these AI models is indeed impressive. Though concerning — but that’s another story.

The post AI proof reading again appeared first on Logic Matters.

December 24, 2025

A Christmas card

Fra Angelico, Adoration of the Magi

Fra Angelico, Adoration of the Magi Sadly, we still haven’t yet been, as we planned, to the Fra Angelico exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi and San Marco in Florence. “Momentous and inexpressibly beautiful … a miracle of an event” said the NYT review: others have similarly extolled the exhibition. There is still a chance we might get there before it closes near the end of January, health issues allowing. Here’s hoping that I can report back!

Meanwhile, I do hope that you and yours — despite the state of the wider world — do have a happy Christmas tide and that your own world is as peaceful as it can be.

The post A Christmas card appeared first on Logic Matters.

December 19, 2025

Revised 2nd edition of ICT

I have just uploaded a PDF of the current draft of a revised second edition of Introducing Category Theory. I will tinker with the draft over the next few weeks, proof-reading with some help from Gemini this time, but also — more importantly — checking for consistency of message on topics like issues of “size”. I hope it won’t be too long before there is a new paperback (and, for the first time for ICT, I’ll then make a hardback available for libraries too). In the meantime, I’ve stopped Amazon from supplying the current paperback.

So, here’s a link to the current PDF (check back every week or so for a minor update — if you are reading the book, you might as well battle with the latest, greatest, version). And — need I add this? — any comments would still be most welcome.

The post Revised 2nd edition of ICT appeared first on Logic Matters.