Kelsey Timmerman's Blog

November 1, 2024

The Best People Chorus on a Singular Stable Genius: A Warning in Their Own Words

((I compiled these quotes from Joint Chiefs, Cabinet members, Ambassadors, Lawyers, Senior staff members and just reordered them. I don’t think any of us would hire a dog walker who had such bad references. A lot of the quotes can be found here .)

It will always be, “Oh, yeah, you worked for the guy who tried to overtake the government.”

I am ashamed of my weakness.

I hope what follows is a sufficient warning to America’s voters to help avoid our worst fears from coming true. Don’t take an oath to a wannabe dictator.

***

I saw him when the cameras were off

Behind closed doors

He mocks his supporters,

He calls them basement dwellers.

He has no empathy, no morals and no fidelity to the truth.

He is a racist,

He is a conman,

He is a cheat.

He certainly falls

Under the definition of a fascist.

Certainly an authoritarian.

He admires murderous dictators,

Repeatedly compromised our principles for his own gain.

A danger for the United States.

His temper was terrifying,

Undisciplined

Unhinged

Unprincipled

Petty

Dangerous

Prone to outright fabrications

Erratic and delusional.

The most grave threat in American history.

He’s a fucking moron,

Lacked basic knowledge.

He has a short attention span, except on matters of personal advantage.

A view with no basis in fact, untethered to truth.

Not very smart.

A despicable human being,

A threat to democracy

He’s caught in a vortex of his ego and aggrievement.

Does not try to unite, tries to divide.

Thrives on purposely sowing strife and discord.

Destroys trust by spreading unfounded conspiracies,

Poisons our respect for fellow citizens.

A consummate narcissist,

Like a 9-year-old,

Will always put his interest first.

Has nothing but contempt for the constitution.

His anti-leadership undermines the rule of law.

He has a penchant for engaging in reckless acts.

His impulsiveness results in half-baked, ill-informed and occasionally reckless decisions,

He says, “Can’t you just shoot them?

Just shoot them in the legs or something?”

“When the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

I was stunned by violence, and was stunned by the indifference to violence,

He hastened the demise of democracy.

The root of the problem is his amorality.

His sense of betrayal drove him,

He’s getting meaner by the day.

My god, what an idiot,

A cynical asshole unfit for our nation’s highest office,

He has no idea what America stands for,

Will extinguish what, if anything, remains of the American Dream.

He has every characteristic you would not want

Hitler’s dictators? America’s Hitler!

He turns on everyone, soon it will be you.

***

We shouldn’t have followed.

If our leaders seek to conceal the truth, or we as people become accepting of alternative realities that are no longer grounded in facts, then we as American citizens are on a pathway to relinquishing our freedom.

Our country can’t be a therapy session for a troubled man like this. We can unite without him, drawing on the strengths inherent in our civil society.

He has never cared about America, its citizens, its future or anything but himself. “You are losers!” he railed. ‘You are all fucking losers!’”

Anyone who puts himself over the constitution should not be president

What can I add that has not already been said?

God help us.

March 23, 2023

Human Rights Day at Indiana State

I bet you can’t name all 25 articles of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. I bet you didn’t even know that there aren’t 25 articles, but 30. Ha! Got ya! I certainly couldn’t until I looked them up while researching WHERE AM I GIVING?

75 years ago the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights drafted by a committee of world leaders chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt. The declaration consists of 30 articles of basic rights and fundamental freedoms. However “basic” and “fundamental” they may be, many people across the world and even in the United States are denied them.

Each year Indiana State hosts a day where speakers and students reflect and discuss human rights. I’ve had the honor of speaking at the event three times over the past 12 years, including last week. This year I shared the stories of Rozy and Dalmas in Kenya, Ashok in India, and how each of them are working to promote human rights in their own communities. They started local and they started small. And because of their work, people in their communities have access to more education, safety, and economic opportunities. I was honored to share their stories and thankful to have the opportunity to connect and be inspired by the uber-engaged students of the Terre Haute community.

Learn more about Human Rights from my post What are the Human Rights Anyhow

Terre Haute’s channel 10 WTHI news reported from the event , as did the Tribune Star .

Talking with students and learning about their work is always a highlight for me at the event. But my favorite moment was getting a hug from one of the founding committee members of the event. He’s retired now, but Human Rights Day continues. He started small. Started local. And now the event has reached thousands of students and who knows how many students those thousands of students have reached.

There are heroes who walk among us, if we only take the time to get to know them.

February 22, 2023

Natural Causes & the Death of MarvHen

MarvHen was the last of our original chickens. And while the chickens we’ve added alongside her received names from our kids, I don’t remember them. I’m not sure anyone does at this point.

I’ve come to learn that our animals aren’t pets; they are a responsibility. I love them, but it’s different than loving our dog Jersey The Pitbull (who would totally love to kill all of the chickens). Jersey is a member of our family; MarvHen provided our family delicious eggs for three years. Jersey’s death will be a sad day at our family. MarvHen’s death is like hearing the news that some not-too-close friends are moving away. A bummer, but time and people and chickens and life and death march on.

The chickens keep me in tune with the time the sun sets and the flight paths of birds of prey. Our family coordinates their care. Did you put the chickens up? Did someone feed the chickens? They have personalities and a pecking order. They are social and once joined a golf party in our neighbors’ yard, staying out too late and overnighting in the fencerow. We’ve laughed and cursed and worried about the chickens. Now we have one less chicken to worry about.

We’ve had six chickens die. One went missing (I like to think she is living some grand Disney animal adventure), one was killed by a hawk, two died of illness, I put our rooster out of his misery, and MarvHen died of natural causes. But really, what we’ve learned from the chickens is that every cause of death is a natural cause. That death is natural.

The pic on the left is of me moving MarvHen to the barn for the winter from her free-range paradise in the woods. The pic on the right is of me carrying her to her final resting place in the woods, an offering to the hawks, owls, and eagles who hoped Marvin’s life would sustain theirs.

January 6, 2023

Fox Business

I was wearing a suit, and no one was getting married. No one had died. I felt like I was going to my own funeral. I felt like I had lost myself. I was going to be on Fox Business.

This was 2007. Fox was Fox, but it wasn’t quite the Fox it is today. And business? There isn’t much business in my soul. But the PR person at my publisher had booked me on a show on Fox Business to share my “expertise” “on” “trade” “in” “China.”

I had been to China exactly one time. I met a couple who worked in the factory that made my Teva flip flops near Guangzhou. I had traveled to the rural province to meet their son who they hadn’t seen in years. I had talked with people who had lost their homes in the valleys flooded by the Three Gorges Dam. I had read a few books on China and trade. But I was no expert.

So I sought to make myself an expert through an hour of googling and reading news stories. When I had done all the preparation I could do, I laid my suit jacket on the backseat of my royal blue Pontiac G6, and prepared to drive to the station in Indianapolis that would host me.

There’s no feeling quite like nervous sweating in a cheap suit. I was miserable.

My book “Where Am I Wearing” had just come out. I was 28 and I felt like I needed to know everything there was to know about the garment industry and globalization. There was no question I wouldn’t attempt to answer with authority.

I felt like a phony.

There’s imposter syndrome: feeling like your lack of skills or knowledge will expose you as a fraud even though you have sufficient skills and knowledge. And then there is being an imposter: pretending to be someone you were not.

In my suit, ready to appear on Fox Business, I was an imposter.

I was beginning to realize that writing a book comes with unearned authority. I was an authority talking about the people I met on my journey following my favorite items of clothing around the world. I had done enough research to write about the economic and political forces that impacted their lives. But speaking on trade policies? In China? On TV? Nope.

Never trust someone who knows everything. It’s a lesson I should’ve known from my days working as a SCUBA instructor. It was always the guys (and it was always guys) who acted like they knew everything about diving and didn’t need any sort of assistance or guidance, who would be the first to panic and require rescuing.

Since that first book, I’ve written three others. I get invited to classes and propped up on stages to speak with audiences. Sometimes at the end of a talk, someone will ask a very specific question prefacing it with their very specific knowledge, showing their authority. The question could be about a particular area of the 1,700-page NAFTA agreement. Suit Kelsey would’ve taken a swing at an answer.

Now I recognize people who never grow to “I don’t know.” They are so used to being a looked-to expert in one area that they begin to believe they are experts in all areas. They are imposters and don’t know it. And suddenly we have politicians who don’t know how government governs. Tech billionaires impacting food and agriculture policy in Africa. A world of suits pretending they know better than actual on-the-ground experts.

Before I turned the key and backed out of my garage to drive to my Fox Business interview, the PR person called. The segment had been canceled. Some other breaking news had bumped it.

A weight lifted. The moment felt like the first day of summer break. Like freedom. I was so close to losing myself in that suit. My appearance surely would’ve gone viral on YouTube and the phony version of me would become the version most people knew.

As I took off my suit, I vowed to never put myself in that position again. Dressing like someone I wasn’t. Pretending to know things I didn’t.

Now when someone asks me to do something I don’t have the skill, knowledge, or expertise to do, I say no. When someone asks me a question I don’t know I say with authority and expertise, “I don’t know.”

December 15, 2022

Local Business

The Rings

The Rings

My friends Dave and Sara Ring own and operate an organic grocery store in my hometown of Muncie, Indiana.

I wrote about them in my book Where Am I Eating?”:

“The Downtown Farm Stand is located in the heart of Muncie. Like our food moving overseas, like farmers moving to the burbs, life in Muncie has moved to McGalliard Road, a long strip of middle America strip malls and every chain restaurant a binge eater could want. The Farm Stand is the only place downtown where Munsonians can buy groceries these days.”

Recently Dave and Sara announced that for a variety of reasons, including declining grocery and deli sales, their store would only be open on Thursdays, as opposed to 6-days per week. And they would close their deli altogether.

I’m sad about it. They made their own bread, roasted meats, and sauces from scratch.

The Downtown Farm Stand deli was one of my favorite things about Muncie. They served the world’s best sandwiches, and while I was there I could pick up some organic, Fair Trade coffee, locally-grown produce, and other groceries. For someone who cared about where my food came from and what it meant for the land and farmers who grew it, Dave and Sara’s store is a trusted filter.

They carried bacon that was the best bacon I’d ever tasted. One day it wasn’t there and I asked Dave about it. Apparently, the farm producing the bacon no longer met the Farm Stand’s standards, so they stopped buying from them.

A lot of stores like the Downtown Farm Stand get into selling vitamins and supplements because the margins are so much higher. But Dave and Sara didn’t want to sell pills; they wanted to sell vitamin-filled and nutrient-rich food.

The fact that an organic, GMO-free grocery located in a struggling post-industrial downtown existed for a single year is a miracle. The Downtown Farm Stand has operated for 16 years, which has required resilience and adaptation. Hopefully these new changes will allow it to continue for many more years to come. They’ve lasted through the Great Recession and now the Great Reset. They’ve been an important part of Muncie’s downtown revitalization.

The ChainsEvery small town used to have at least one grocery store. It was typically named after the family who owned it. The family members worked in the store. Their kids and grandkids went to school with you. You could recommend a product and they’d stock it. In a lesson of “there is always a bigger fish”: regional chains consumed the mom-and-pop stores, then the regional chains were consumed by even larger regional chains, which were consumed by national chains such as Walmart, Target, and Costco. The stores fled urban and rural areas for the suburbs, leaving communities in food deserts with dollar and convenient stores as artificial oases of empty calories.

The Downtown Farm Stand bucked all those trends. Before consumers were supporting organic, the Downtown Farm Stand was selling it. Through the years the demand for organic and healthy food has grown. However, chains that didn’t carry organic food, now do, or through greenwashing using meaningless terms like natural, humanely, locally grown, act like their food is healthier and more environmentally-friendly than it actually is. Now Walmart is probably the largest seller of organic food in our community.

To be clear, I’m entrapped by the chains and their cheaper prices as well. While we do get a produce bin from the Farm Stand delivered every other week, support their latest venture–a music lounge–and regularly ate at their deli, we still spend the majority of our grocery dollars at chains. As Wendell Berry writes, “We’re all complicit in the things we may be trying to oppose. I’m complicit in the things that I’m trying to oppose.”

The Business of Being a LocalThere are a lot of large supply chain forces working against a local grocery store like the Downtown Farm Stand, but I don’t want to address the business side of local business, I want to focus on the local side of local business, which is really about the business of being a local.

Unlike the Walton family who owns Walmart or the Meijer family who owns Meijer or the countless shareholders who own Target and Costco, Dave and Sara are a part of the community they serve. That’s supposed to be a good thing. A feather in the cap of locally-owned businesses. How can the Waltons compete with that?

But after living in my community for 15 years, I’ve also seen how this is a bad thing.

Sara and Dave have opinions and thoughts about the direction of our community, as any active community members should.

They fought against schools spraying herbicides on playgrounds.

They fought against the construction of a local hog CAFO.

They fought against a heavy metal recycling facility on the edge of town that would have drastically decreased the quality of our communities’ air.

They spoke out against government corruption before that government corruption had been confirmed by a long-running FBI investigation.

They spoke out against the hundreds of thousands of dollars of government-support that helped bring a major competitor, Meijer-owned Fresh Thyme, to our community.

Dave ran for State Senate and then for County Commissioner.

During each of these fights and campaigns there were local people on the opposite side of the Rings. People who “used to go to the Farm Stand” until they disagreed with Sara and Dave’s opinion, fight, or activism.

I’m as guilty as anyone. I’ve had the words and actions of local business owners rub me the wrong way, and because there are few local options, I chose, perhaps with not enough thought, to instead take my business to the chains.

Maybe being outspoken and involved in so many issues is small business malpractice. Maybe it’s best if the Rings and other local business owners just shut up and sold groceries. Maybe if you run a business you should stay quiet. Be a voiceless, passive member of our community.

The Local Burden

National chains don’t shoulder the local burden. They are nameless and faceless and largely opinionless, which shouldn’t be a benefit. What are Target’s values? What are Walmart’s values? What do they think about our community? Do they even think about our community or are we a line item on some corporate spreadsheet, reduced to a zip code or store number?

Sure, these national and large regional chains execute some corporate-giving initiatives and they pay taxes and employ folks, but are they showing up to City or County Council meetings? Are they helping to shape and direct our community? Going all-in for a school levy? Speaking out against a local injustice?

Dave and Sara stopped offering chicken in the deli because they couldn’t get it from a supplier raising them on pasture. Meanwhile, Meijer, Walmart, and Target sell chickens grown in cages, pumped full of antibiotics and steroids, and processed in factories by workers whose bosses took bets on how many of them would die during the height of the COVID pandemic. National chains sell “grass-fed” beef contributing to deforestation in the Amazon and chocolate produced by enslaved people. They profit from products sold on the shelves in our community, produced in other communities that have been poisoned, polluted, and enslaved.

Yet people say: “But did you read the Op-Ed that Dave wrote? Did you hear him speak out at the meeting?” And then they give their business to the chains.

I’m writing this for my community as much as yours, to remind me as much as you. Whether or not we agree with a small business owner in our community, we should appreciate when they care enough about our community to speak out and get involved. I . . . We should think twice before turning our backs on local businesses and taking our business to voiceless, faceless, impersonal national chains that don’t have opinions, or neighbors, or hands to shake, or ears to listen, or the heart of a Sara and Dave who regularly guide recently-diagnosed cancer patients on their journey to cleaner eating, and who comforted my wife and me when we embarked on a new diet to help our autistic son.

Chains?

Chains care about business.

Locals?

Locals care about the business of being a local.

December 9, 2022

Staying in it

(Cliff playing a song for Enemias)

When I was in Colombia learning from the Arhuaco about their relationship with nature, my friend Cliff accompanied me. Cliff is a talented musician and photographer. (And he is exhibiting his work on Saturday December 10th at 201 E. Charles St. Muncie, IN 47305, starting at 2 pm and ending with some words and music from Cliff at 7 pm.)

The Arhuaco are an Indigenous People who live in the Sierra Nevada mountains of northern Colombia. Like most Indigenous People around the world, they’ve had less than favorable interactions with the outsiders. They were hesitant to have us visit and much of our first day was spent sitting with one of their spiritual leaders, who had us examine our own intentions for being there. Was it only to take pictures and stories or were we there to partner with them to help share their worldview.

Our permission was officially granted and then they blessed cotton bracelets that they tied around our wrists. They told us, “The Mountains are happy you are here.”

One day we were taken into the jungle with one of their most revered spiritual leaders, a man named Enemias. They cleared some vegetation for us and we were told to sit. Enemias led us through more self-reflection. As we sat, I, and I alone, was devoured by ants. I think the mountains wanted to eat me.

Often my work as a writer isn’t to write. It’s to experience. As Enemias talked, I wanted to scribble down notes. I could see the same tension on Cliff’s face as he stared down at his camera he hadn’t used all day. And then Enemias stood. The afternoon sun lit him perfectly. I could see Cliff’s camera finger twitching.

“Can I take photos now?” Cliff asked.

“Not yet,” Miguel, our guide, said.

Cliff calmed and a peace came over him. He said that in that moment he thought of a scene from the movie The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, in which Walter Mitty played by Ben Stiller tracks down a legendary wildlife photographer, played by Sean Penn, perched on a mountainside. As they talk a snow leopard steps into the photographers frame, opens its mouth. It’s the perfect shot.

Walter: “Why don’t you take it?”

Photographer: “Sometimes I don’t. If I like a moment, for me, personally, I don’t like to have the distraction of the camera. I just want to stay in it.”

Walter: Stay in it?

Photographer: Yeah. Right there. Right here.

I hadn’t even realized there was an opening in the canopy to let the sun penetrate. Enemias was perfectly silhouetted, yet somehow there was still light reflecting on his face. He stood as still as a tree.

We stayed in it. Right there.

December 2, 2022

Change Starts with a $6 Soccer Ball

The World Cup is underway, so I thought I would share a few soccer stories from around the world from my reporting involving the beautiful game.

In India, I got to spend time with Ashok Rathod, who founded the OSCAR Foundation. I wrote two chapters in my book Where Am I Giving? on my experiences in Ashok’s community. In the chapter below I meet Ashok and learn how he’s impacting his community through soccer.

If you like what you read, consider following OSCAR on Facebook and consider buying a copy of Where Am I Giving? for more stories of awesome givers like Ashok.

Buy Where Am I Giving? at Bookshop / Indiebound / Barnes & Noble /Books-A-Million / Amazon Chapter 16: Start With Your Local (India, 2017)Crossing caste lines / Towers & slums / Untouchables

WHEN THE 50-SOMETHING-YEAR-OLD MUSTACHED man wearing a sailor’s suit saluted me, I wasn’t comfortable. Nor was I when the hotel manager told me the man in the sailor’s suit, his “boy,” could carry my bag to my room and then called for him: “Boy!”

I wasn’t comfortable ringing a bell at lunch so a waiter could meet my immediate need – Heinz ketchup.

I wasn’t comfortable when the man in the sailor’s suit saluted me as I left in the morning to make my way to the docks. I’ve earned no rank or status. I had enough money to buy a plane ticket to India. I was American. I knew a guy who knew a guy who was a member at the Royal Bombay Yacht Club and could get me into one of the three-room guestrooms accessed by a palatial staircase or a steam-punk elevator. None of which made me salute-worthy.

The man’s spine straightened, and his heels nearly clicked. I awkwardly nodded to his salute and flagged down one of Mumbai’s famous black-and-yellow cabs. To my relief, the driver turned on his meter. The day before a driver had refused to do so, intending to charge me more than the going rate, and I demanded he stop to let me out, but he wouldn’t. I demanded to be treated equally—like a local. Why should I pay more? Why should I be treated differently? I had threatened to jump out, had my door open and everything. He called my bluff. I wasn’t going to jump out of a moving car because of $1.

The driver dropped me at the Sassoon dock. This wasn’t a dock for yachts, but one of the oldest docks and largest fishing markets in Mumbai.

The women who lined the entrance of the dock didn’t salute me; they motioned to the fresh catch before them: Would I like to buy a recently killed stingray?

It was tempting, but I was heading to a meeting that a dead stingray would make awkward.

At the dock, men tossed faded pastel baskets filled with their catch eight feet up to other men standing on the seawall. Those men passed the catch to other men who auctioned the fish to women. Auction winners walked away with shrimp, crab, and fish of all sorts balancing on their heads. They pushed me out of their way to get where they were going.

Ashok Rathod rolled up on his scooter. He wore prescription Oakley glasses and had disheveled, thick hair, and a look on his face that seemed to question everything. We wove our way through the crowds at the dock.

“Sometimes the women will pour fish water on you to get you out of the way,” Ashok warned in a gravelly voice. Ashok is the founder of the OSCAR Foundation. He’s a movie lover and named the nonprofit after the Oscar awards, which was somewhat incongruent with the organization’s mission and perhaps in violation of copyright, so he came up with an acronym: Organization for Social Change Awareness and Responsibility. Ashok chose to meet at the dock to tell me about OSCAR’s work using soccer as a means to promote education and empower underprivileged kids.

“I started working here when I was 10,” Ashok said.

Ashok’s father worked on the docks for 35 years before becoming a gardener. He did not want his children to follow in his footsteps, so he enrolled them in a government school where the teacher-to-student ratio was 1 to 65.

“The education is not good,” Ashok said. “One day we decided during our break to go to the fishing market to see how our parents made money. There were a lot of fish on the floor. Everyone was busy running around to sell fish, buy fish . . . Whatever fish fell down, we were collecting and putting in a bucket. When the bucket was full, someone came to us: ‘How much?’”

Back then, 17 years ago, fish were so plentiful that no one cared about the small fish; now the adults collect them. Things were cheaper, too. Ashok could go to school in the morning, sneak off to the fish market at lunch to earn $2 or $3, and head back to school with enough money to see a movie and grab something to eat.

“One day my father found that I was here working. He warned me, ‘If you come again, we will throw you out of the house.’ So I stopped coming because if I got thrown out of the house, where would I stay?”

Ashok stayed in school, while his friends dropped out to work.

We walked past the boats to a long open-walled building beyond the hustle where men repaired fishing nets. During the monsoon, the government doesn’t allow large-scale fishing. During the main season, this dock would be full.

By age 15, Ashok’s friends started drinking, gambling, and smoking. They broke into groups sort of like gangs and got into fights with other groups. When their parents found out what their boys were up to, they made them marry. The responsibilities of a family would calm them down. This was the cycle of life in the slum. Few went to school. Few left.

“Now they are 28 or 29 years old and have two to four children,” Ashok said, watching the men fix the nets. “Now everything becomes expensive and their income is less . . . They have to work 12 hours. It’s a hard life for them to feed their children. I’m sharing this story because I wanted to become like them: to earn money, enjoy life and not to think about the future, to think of today’s life and enjoy. I thought this was the best way. But because of my father, I continued school.”

A white police SUV pulled in front of us, blocking our path to the end of the dock. The police called Ashok over to check out what we were doing. In November 2008, 10 terrorists came ashore on the Sassoon dock and executed four days of shootings in a train station, café, hospital, movie theater, and hotel that claimed 164 lives. The fishermen had been reporting their concerns about strange and unlicensed boats around the docks for days leading up to the attack, but no one listened to them – they were just fishermen.

The police are determined not to make the same mistake again and are extra sensitive to a foreigner walking around snapping photos and taking notes. Ashok and I walked in silence and once the police drove out of sight, I asked him to continue his story.

Ashok graduated and volunteered with Door Step School, a nonprofit that worked to educate kids with the goal of enrolling them in public schools. A few years later, he got his first job with another NGO, Magic Bus, which also focused on educating kids.

“One day I was coming home from work and I saw two boys from my neighborhood. They were smoking at the age of 13. They saw me, and they hid behind a car.”

The kids were on the same path as his friends, the same path he would’ve taken if not for his father. Ashok had a vague idea of doing something to help kids in his own community.

“I identified 18 children who were school dropouts and I asked them, ‘Do you want to play football?’ I didn’t tell them anything about education directly.”

The kids mostly played cricket, but they were interested in football – or as we refer to it in the U.S., soccer. They had never worked with a coach in any sport before and the prospect of having a coach and playing a sport more formally appealed to them. Ashok told them to come to the field Saturday at 4 p.m. They did, all 18. Ashok didn’t think any of them would show up, so he didn’t go.

“They called me: ‘Where are you? We are here to play football!’ I said, ‘Wait, wait, I am coming. I reached there in 10 minutes.”

The kids saw him coming, empty-handed. He didn’t even have a ball. “Some football coach,” the kids thought. He led them in a few other games and promised he would return the following week. He couldn’t really afford a ball, but bought one anyway, for $6 – a quarter of his weekly salary.

“Initially,” Ashok said, “they weren’t willing to play each other because they were coming from different castes and religions. Everyone wanted to keep the football with them, and nobody wanted to share.”

Ashok decided to mix the teams, and soon the kids were celebrating goals across castes and religions. “Basically,” Ashok said, “it’s about all cultures and religions living together. It’s about unity.”

He told them that if they wanted to continue, they had to enroll and stay in school. Ashok was onto something.

More kids started to show up, which was great, but a problem because he couldn’t afford more equipment. Fast-forward 10 years, and the OSCAR Foundation now reaches 3,000 kids. Prince William and Kate Middleton have visited. Manchester United forward Juan Mata spent two days practicing with the kids and, no doubt, getting a similar tour that ended in the same improbable location: Ashok’s home.

We made our way from the dock to Ashok’s community. I sat on the back of his scooter as the monsoon season pelted us with rain from a gray sky. The Ambedkar Nagar slum in Cuffe Parade sits off the road behind a high wall painted with OSCAR Foundation art: a painting of kids raising their hands and a close-up of a girl’s face.

“That is the raising hand,” Ashok said, pointing to the paintings, “like coming up and also having an opportunity to help others come up. This is about women and girls. They have many challenges, but they are strong and face them. Forty percent of the kids in our programs are girls.”

Ashok led me past the wall and down a crooked alley. Nothing was straight. The walls of the houses weren’t. The ground was uneven. For the most part these weren’t the tin shanties and tarps that I had come to know in the slums of Kenya or Cambodia, but two-story structures carved out of a world of concrete. Local media outlets referred to them as “hutments.” The first levels housed stores, and steep ladders accessed the dwellings above.

We passed kids in red OSCAR shirts. They asked me if I played football, probably hoping I was some less athletic European star they didn’t recognize. Another kid asked me if I knew Juan Mata.

“Here they are mostly working in laundry,” Ashok said.

A man swung a long white sheet across his shoulder and then whipped it down like a hammer at a carnival trying to ring a bell. An arch of water followed the tail of the sheet.

Ashok estimated that 15% to 20% of people in his community beat, scrubbed, and dried the laundry of the area hotels and the surrounding luxury apartments.

“From my hotel?” I asked, as if it mattered. Should I have more empathy or guilt or connection with this man if it were my sheet?

A man, wearing only a bleached white towel, stepped to the side as we left the laundry. He brushed his teeth, white foam gathering in the corners of his mouth.

The alley narrowed. I felt like a giant, my shoulders barely clearing the distance between buildings. Ashok climbed a ladder.

“This is the library,” Ashok said.

Shelves on the walls held short stacks of books organized by grade level. There was 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, a Hardy Boys graphic novel, The Story of India for Children, and the somewhat creepy title of Crazy Times with Uncle Ken. A cartoon frog and dinosaur were painted on the wall along with the phrase: “Send them to school.”

Two office chairs sat at a desk where Ashok put his wallet stuffed so full of cards that it was round – the wallet of a man who won’t let go or is too busy to bother. Other than that, the middle of the room was open. It might’ve been 10 feet across at the most. Ashok told me that most homes in his community were smaller than this room and slept six or seven people.

I asked if he lived in a similar place, thinking that he probably didn’t, thinking his education had lifted him to a higher standard of living, thinking that the founder of a nonprofit that had been visited by stars and princes – and who had earned the support of embassies and corporations – would live elsewhere.

“Yes,” Ashok said. He reached into a cupboard and pulled out a small bedroll. “This is my bed. I sleep here.”

His phone rang. He apologized and answered it.

I looked around the room and out the short doorway. A shining apartment tower seemed to rise into infinity. Archana, the woman who first told me about Ashok and OSCAR, lived in that apartment tower. She was a friend of the man who got me into the Royal Bombay Yacht Club.

Ashok can roll out his bed on the floor and see the tower where a three-bedroom, 2,000-square-foot apartment lists for more than $2 million. When the sun rises, the shadows of the towers, the most desired real estate in Mumbai, reach toward the slum.

A month before my visit, the Forest Department, accompanied by 100 police of officers, bulldozed more than 1,000 homes here. They claimed the homes were in violation of a law protecting mangrove cover. Residents claimed that the demolitions took place without notice, and they weren’t allowed to save their belongings beforehand. They speculate that someday their homes will become new high-rises.

Residents of the slum work in the apartment towers as domestic help and drivers. They cook exotic meals they would never eat from countries they will never visit. They pick up toys they could never afford and support lifestyles they could never live.

It’s not normal for someone in the apartment tower with ocean views to go down and visit the slum. Arachna first visited five years ago when her staff invited her to their homes during Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. Now she volunteers as an English teacher and, collects toys for OSCAR’s community toy library. Sometimes she takes the kids to the movies on their birthdays. She has arranged for a Santa to go door-to-door delivering chocolates in the community. She inspired a friend of hers to donate his services for a dental clinic.

“Ashok is super inspiring,” she told me. “He’s giving back, not from a higher place, but from where he lives. He’s stayed inside the slum even though he could leave.”

The world has haves and have-nots, but the proximity – a short walk – and the disparity between the apartments and the slum are staggering. Yet, many who live in the apartments choose not to experience the slum even though they have a “slum view” every bit as much as they have an “ocean view.”

People in the towers think the men are drunks, that the slum is dirty. They have strong opinions about a place they’ve never been. They may like their help, see giving to them as their charity, and see them as part of their family, but not extend that charity, empathy, or love to the other residents of the slum.

People in the towers think the men are drunks, that the slum is dirty. They have strong opinions about a place they’ve never been. They may like their help, see giving to them as their charity, and see them as part of their family, but not extend that charity, empathy, or love to the other residents of the slum.

In India those who believe in karma believe that those who live in hutments got what they deserved. Archana told me she believed in karma, but she also believed in the importance of spending time supporting OSCAR and interacting with people in the community.

Ashok inspired her, and she inspired her friends to give, although not all of them are comfortable visiting. She sees herself as a bridge.

Ashok hung up the phone. It was his girlfriend. Speaking of divides and bridges, she’s from another caste. She’s getting a Master’s in women empowerment at one of the best schools in the country. He’s Banjara and she’s Brahmin. His parents just found out about the relationship and don’t approve. They are afraid he will leave. Her parents don’t even know. They met five years ago when he was speaking at a conference she attended.

“I’m from a very low caste,” Ashok said. “I don’t believe in caste. According to [society] I come from the very bottom and she comes from the top.”

In some states in India, the government classifies Banjara as an “other backward class” (OBC), a term referring to castes that are socially and educationally disadvantaged. Sometimes they are referred to as “untouchables.”

The Brahmin occupy the top of the social structure. In Hinduism they are seen as the priests and protectors, the closest to the gods.

Ashok and his girlfriend come from different cultures and speak different languages.

People in the community look up to Ashok. He has received awards on TV and appeared alongside global celebrities, and more than that he has promoted education and unity. Kids are going to university; they are traveling abroad. Gang membership has declined. He has inspired other sports programs in the community. People greet him as a celebrity, but not some unknowable celebrity. He’s their celebrity.

“Now the community is going against me,” Ashok said. “People are against the relationship. Because they think that here I am a famous face for the youth and the children, and they think if I get married to a different caste, other youths will also follow me.”

Ashok intends to marry his girlfriend, but he worries what that will mean for his family and the community he loves. Someone had already totaled his old scooter by beating it with a heavy rock. I could hear the pressure in his voice. It wasn’t really a decision anymore. He knew what he would do. He just couldn’t predict the impact that leaving would make.

“I will leave,” Ashok said. “I love staying here, but, yes, I want to leave.”

Two years into OSCAR, he struggled with the kids’ parents. They weren’t happy. The kids were always using practice as an excuse to run off. Eight of the kids dropped out of school.

Some of the parents weren’t sold on the idea of school. Unlike Ashok’s dad, they didn’t see the value of an education. For generations, there were set jobs for set castes. Their children would do laundry, or fish, or work in a home, or drive a car. This perception remained, despite the fact that social mobility in India – the percentage of the population escaping poverty – has been equal to that in the United States for more than a decade.

When Ashok started the program, no one gave him money. They thought he might misuse it.

“They were judging me because I live in a slum,” he said. “Then one day in 2009, I shared this problem with the children.”

The OSCAR team had lost in the semifinals of a tournament. The kids were devastated. They cried. Ashok started to give them a pep talk and started to cry himself. His team had lost to teams that had more equipment than his kids had. He felt that he had let them down. He walked out of the room, wiped away his tears, and then returned.

“Competition isn’t easy,” he told them. “Anything you want . . . you have to work hard. Practice. Practice. Practice and work hard. This time we reached the semifinal; next time we can reach the final. It’s not your mistake that we don’t have equipment. If we had more equipment your game could improve faster. Because I don’t have money, I can’t buy more equipment.”

What had started as a pep talk devolved into exposing the depressing truths that had brought tears to Ashok’s eyes in the first place. No one believed in Ashok enough to give him money – no one except for the kids.

They had a solution. Every kid who participated in OSCAR would bring a single rupee (less than 2 cents) to each practice. Ashok used the money to fix the discarded balls from other teams, which cost him less than a dollar. He had more equipment for more kids. OSCAR’s first major financial backers were the children themselves.

That was the tipping point. By 2014, OSCAR was working with 600 kids, and in 2017 with 3,000 kids.

OSCAR has grown to other communities and states in India.

***

I accompanied Ashok into a neighborhood interested in starting a program with OSCAR.

The flat, muddy, clay field looked like the blank slate of a future high-rise apartment building. Trump Tower Mumbai, still under construction, looked down upon us. I had seen a billboard advertising the $1.2 million condos that read: “Any resemblance to a 7-star hotel is purely intentional.”

The property’s website has a section on privileges, which included: “A private jet at your service: Chauffeur-driven cars are passé. As a resident of Trump Tower Mumbai, you have a private jet at your disposal, ready to whisk you away to a destination of your choice. This service is the ultimate way to travel. But then our residents are used to being spoiled.”

Other privileges included a Trump Card that will allow you to “live without boundaries, limits or compromises” and stay in other Trump properties around the world, a pool where you can “soak up the luxury . . . located high above the ground, for your pleasure.”

Far below, we were standing in monsoon mud puddles. A Cummings generator hummed rather quietly, powering a welder renovating the stands. Orlando, OSCAR’s newly-hired program manager, talked to me over the hum. He was as tall as I was; his hair was shaved on the sides and curly on top. If someone had told me that he was a famous Indian soccer player, I would have believed it. He was well educated and came from a family of means. Previously he had worked in a call center and talked to English speakers all over the world.

A man in his forties arrived. He talked with Ashok and then made a call. Soon 12 college-aged students showed up, each of them with unique boy band hair – thick, coiffed, styled.

Introductions were made, and first they determined what language was best to use for everyone: Hindi.

Ashok mentioned the successes of the program, the kids, Juan Mata, and the awards. The students started to look from Ashok to one another, nodding their approval and sharing looks that said: “This is pretty cool. We should do this.” But then their body language shifted when they realized they were too old to participate as athletes in the program.

Ashok won them back when he talked about the young leaders program. There were 150 active young leaders in OSCAR, led by eight staff coaches.

Behind them, a laborer stacked bricks in a wheelbarrow with a wheel that made a clunking noise once every revolution. Ashok talked of a world of opportunities beyond the field, beyond Trump Tower. OSCAR students were going to England; they were going to visit Manchester United.

As Ashok spoke, the group grew. People just appeared. By the time Ashok was finished speaking there were 20 potential coaches and players passing him their names and phone numbers.

At the end of the meeting when participants divided themselves into smaller circles, Ashok walked over to a group of kids playing cricket. He doesn’t walk with the natural step of an athlete. His feet duck out a bit and he shifts from side to side in a strut. His glasses are thick, and he’s short. If this were a movie, Orlando would be the leading man and Ashok his sidekick.

Ashok held a soccer ball in his hands. He offered the ball to the kids.

“We say that football is our religion,” Ashok told me. “Football never tells you, ‘Don’t pick me because you are a Christian. Don’t pick me because you are a Hindu or Muslim.’”

—

That night I returned to the Royal Bombay Yacht Club to a world where a man in a sailor’s suit saluted me, where my five nights cost more than a year’s worth of rent in the slum, where a locker room attendant gave me fresh bleached white towels and mouthwash. It felt like I was in a tower of privilege looking out at the ocean view as if it were mine, something I earned or deserved. In India the haves and have-nots are in sight of one another if they take the time to see.

Part of me wants to enjoy the view, looking out and not down, but mostly I don’t want to forget seeing the tower from the slum.

The lives of those in the towers and at the yacht club are closer to my own, and probably yours, than to Ashok’s and the OSCAR kids. I have lived in a yacht club most of my life, really. If I feel uncomfortable at the yacht club, I should feel uncomfortable in my own life, unless I do something about it.

In the tower a soccer ball is just a soccer ball. But in the Ambedkar Nagar slum, a soccer ball is much, much more.

If you like what you read, consider following OSCAR on Facebook and consider buying a copy of Where Am I Giving? at Bookshop / Indiebound / Barnes & Noble /Books-A-Million / Amazon

December 1, 2022

What is land worth?

Winter is almost here and the field beyond the auction sign looks like a desert. Corn stalks as tumbleweeds. Lifeless soil, dusty as sand. Vultures feasting on mammals that couldn’t outrun the reaping.

It’s a windy day in Indiana, and if you picked up a handful of dirt and threw it into the air, it would blow to the highway? The next county? The Sahel?

Yesterday a mammal lifted a bidding number and bid $15,000 per acre for the land. To be clear, the animal was a human. Although the mental image of a raccoon lifting up a number with its five, long, tapered raccoon hands, little nails scratching on the paper, is one I’d like to sit with for a spell.

If the raccoon placed the winning bid, it wouldn’t plant the field with soybeans and corn like the human farmers, who, if they were lucky, would profit $400 per acre per year and take 37.5 years to equal the initial investment. The raccoon would let the land do what it wants to do. Let the seed bank grow. No plow. No poison.

The mustard plants would paint the fields yellow, the henbit and deadnettle purple. A succession from a grassland of wildflowers to bushes, trees, and then a hardwood forest. A friend’s mother paints such landscapes. Her paintings sell for $2,000.

A proper raccoon wonderland. The rabbits would do what rabbits do and the hawks and eagles and owls would feast. The micorogranisms in the soil would explode, decompose, give life. The soil would grow.

All of this life. And none of them would think to thank the raccoon or ask how a raccoon got its financing.

What would a human banker think? All those roots and life in the way. All those weeds. How unproductive. An acre of woods in Indiana is only worth one thousand human dollars, 1/15th of the bare land.

It takes 500 years to build an inch of topsoil, which each rain and gust of wind deducts from the field’s account. There’s only so much soil and oil. The land won’t stand being treated like a Chia Pet. A sprinkle of fertility mined from distant lands. Magic chemicals losing their magic.

The human bankers and bidders don’t realize it, but they can’t outrun the reaping either. The ledger is out of balance. The raccoon knows something they’ve forgotten. Land isn’t an investment. Land is home. The more dollars it’s worth to one human, the less it’s worth to all other life.

Land isn’t worth $15,000 per acre. It’s worth everything. Futures of everythings.

A single industrious raccoon could grow more than $400 per acre.

November 29, 2022

Ugly Truth, Beautiful Game

(These ladies in Mumbai showed me how they played the beautiful game)

In Indiana, when I was a kid, we had wooden goal posts painted white.

In Cambodia, the goals were orange cones.

In the Mosquito jungle of Honduras the goals were piles of fresh wood shavings–leftovers from crafting dugout canoes.

In a slum in Mumbai, the goal was a puddle of water filled by a monsoon.

In rural China, the goal was not to have to chase a ball down the terraced fields.

Beautiful GameWhile reporting around the world from some 60 countries, I’ve seen soccer/football played in almost all of them. Often the ball wasn’t a ball but a plastic bottle, or plastic bags taped together, or some collection of cloth and string and tape.

I had assumed that’s why football (soccer) was called “the beautiful game.” Football can be played with anything that can be kicked and almost anywhere. Football doesn’t require expensive gear, manicured grounds, or any equipment whatsoever. If you want to play football, you can play football.

Half of the world’s population lives on less than $2.50 per day, yet football is accessible to everyone.

That’s beautiful.

Yet it turns out there is no settled origin story of why football is call “the beautiful game.” Some say it’s the grace required among individuals and teams. Some say it’s because David can beat Goliath.

Let’s accept that a thing can be beautiful to different people for different reasons. Okay?

Football is beautiful (to me) because it is accessible to people regardless if they are subsistence farmers, residents of a slum, or live in a war-torn nation near a minefield.

Ugly World (Cup)I met a guy, Ashok Rathod, who had lived his entire life in a slum in Mumbai. He spent $6, a large chunk of his weekly wages, on a football so he could coach kids that lived in his community. Ashok eventually founded the OSCAR foundation. If the kids wanted to play, they had to stay in school. Today his organization has received international recognition from Juan Matta, Prince William, and Pharrell Williams, and has impacted the lives of 14,000 children across India. And it all started with a $6 football.

Qatar spent $220 billion on stadiums and infrastructure in order to host The World Cup. That’s more than any country has ever spent on the Olympics. The nation has a population of 3 million, and 88% are migrant workers from places like Ashok’s community in India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Since being awarded the World Cup and beginning construction in 2010, 6,500 migrant workers have died. Maybe one of the players I played with when I visited to report on Ashok and OSCAR were among the dead, since many relatives pursue opportunities in the Middle East.

Qatar doesn’t have much of a football tradition and daytime temperatures can hit 130-degrees. It’s not a logical choice to host such a sporting event. The nation was a long shot to be selected as the host, but Qatar bribed FIFA officials as did Russia to host the World Cup.

There are other issues. Only recently did the nation announce to the surprise of sponsor Budweiser that beer would not be served at the World Cup. How the hooligans going to hooligan?

It’s illegal to be gay in Qatar. Players faced penalties from FIFA if they wore “One Love” armbands in support of the LGBTQ+ community.

The problems go beyond Qatar to the World Cup in general. Other host nations have had labor issues–poor working conditions and pay for the necessary infrastructure. Brazil constructed a $200+ million stadium in the Amazon that hosted four matches. It’s one of a long line of excessively expensive stadiums that have been abandoned. Crumbling memorials to the waste and irresponsibility of modern life.

There is so much money in football. With money comes corruption and exploitation.

Like half the people on planet Earth, I’ll tune in, well aware that some of the players on the pitch might’ve started playing by kicking homemade balls through makeshift goals. That’s indeed beautiful. But also aware that the migrant workers who may have come from those same communities left siblings, parents, and children, often paying $2,000 bribes for the opportunity, attempting to improve the lives of their families back home.

At the World Cup in Qatar 832 players will play on the fields, which 6,500 migrant workers died to build.

The game of football is beautiful, the realities of our world and the World Cup are ugly.

***

Still curious?Read: In the coming days and weeks of the World Cup, I plan to share some excerpts from my soccer reporting through the years.

Listen to an Episode of The Good People podcast in which I interview Seren Fryatt of L.A.C.E.S., an NGO that works to create a sustainable, replicable model of community development using sports as a tool to reach at-risk youth and empower their local communities.

Watch John Oliver’s deep dive on the World Cup in Qatar:

November 28, 2022

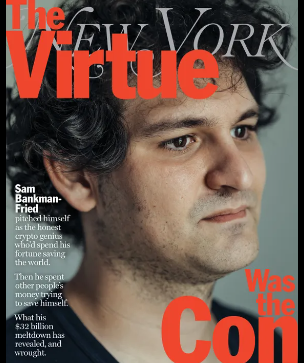

FTX, SBF, and EA: When a Do-Gooder Does Bad

One of effective altruism’s biggest givers, crypto-bro Sam Bankman-Fried (often referred to as SBF), may have built his billion-dollar empire on lies and under the cover of goodwill bought by his extreme giving.

Ross Douthat of the New York Times referred to Bankman-Fried’s actions as “playing Robin Hood using proceeds from an over-leveraged Ponzi Scheme.” And he did so from his penthouse of pills and polyamory in the Bahamas. At least he had fun, but now the entire Effective Altruism (EA) movement is under fire.

Just look at these headlines written after SBF’s fall:

Effective Altruism Committed the Sin It Was Supposed to Correct

Effective altruism solved all the problems of capitalism—until it didn’t. What if a movement designed to do the maximum good for the most people actually helped a few people get very rich?

Is Effective Altruism to Blame for Sam Bankman-Fried?

It looks like SBF stole money from Tom Brady, the mean shark from Shark Tank, and a lot of other people to the tune of billions of dollars, and then gave much of it away to folks working to prevent future robots from deleting humanity.

What money was left was imaginary. When Crypto started to collapse and people wanted their money back from SBF’s exchange, FTX, it was essentially a run on the bank, and the bank didn’t have any money! All of that is probably an oversimplification. You can find much more in-depth analyses of what happened from people who don’t think crypto is fake fairy dust spreading cancer upon our economy and climate. But that’s my take, and I don’t want to examine crypto here. I want to focus on Effective Altruism.

Effective AltruismA few years ago I wrote “Where Am I Giving?” a book in which I went in search of a good person equation. After realizing and accepting that we live in a world of injustice and inequality, I sought an answer to the question: What can each of us do to make a positive impact? The book was heavily inspired by the work of philosopher Peter Singer. In his book “The Life You Can Save,” which should be read by everyone on Earth, Singer essentially states that we ought to do the most good we can do to help those living in extreme poverty and eliminate human suffering.

This simple, yet challenging idea, inspired the Effective Altruism movement, led by Will MacAskill among others. Essentially we need to give more with our heads than just our hearts. Websites such as Singer’s The Life You Can Save, MacAskill’s Giving What We Can, and ultimately effectivealtruism.org recruited givers and pointed them to orgs like GiveWell.org that conducted triple-blind analyses of nonprofits to see which were the most effective at saving a life. And then encouraged people to donate to them.

I was sold on the idea. In fact, as I started to research my book, I saw it as sort of a boots-on-the-ground look at EA. I visited and wrote about Give Directly, one of the top recommended sites of the movement. I gave money to them along with the Against Malaria Fund, which had been deemed the most effective for years.

Where Am I GivingAs I researched the book, my idea of giving broadened beyond that of EA, yet I was still aligned enough with EA that I solicited and was thrilled to receive blurbs from both Singer and MacAskill.

“Kelsey Timmerman has been where very few donors go, and has seen the positive impact of the highly effective giving I advocate, as well as the negative impact of less desirable forms of giving. Where Am I Giving? offers thought-provoking and often entertaining insights into the importance of thinking carefully about where we give. ”

– Peter Singer, professor of bioethics, Princeton University, and founder of The Life You Can Save.

“Traveling with Kelsey Timmerman in the pages of Where Am I Giving? will inspire you to do the most good you can do.”

– Will MacAskill, President of the Centre for Effective Altruism and author of Doing Good Better: Effective Altruism and How You Can Make a Difference

My book wasn’t just a boots-on-the-ground look at effective altruism; it became something different, partly because the EA movement lost me with certain ideas, including “earning to give” and the movement’s ever-increasing focus on directing funds to preventing human extinction by AI and eliminating animal agriculture. But also because I came to realize that there were more forms of giving and human generosity than donations to a nonprofit you read about on a website.

The idea of “earning to give” offered absolution to the uber-wealthy, so it makes sense that someone like SBF would be into it when he met MacAskill.

From Intelligencer by Eric Levitz:

“…MacAskill hoped to guide MIT’s aspiring altruists onto that path. While in Cambridge, he learned of an especially promising candidate for the cause, an undergraduate named Sam Bankman-Fried.

Over lunch, Bankman-Fried told MacAskill that he had recently become a vegan and wanted a job in which he could advance the cause of animal welfare. MacAskill suggested that he would reduce animal suffering far more if he tried to make a lot of money and then donated it to relevant charities. Bankman-Fried took his advice.”

SBF decided to go into finance and then he started his own hedge fund. Eventually, his net worth was reported to be around $26 billion. He intended to give much of it away to EA supported causes, especially those supporting ending animal agriculture and the threat of artificial intelligence.

Billionaires vs Billionaires’ RobotsWhen the EA movement gets away from maximizing giving to most effectively end human suffering, it loses me. Tushar Gandhi, Gandhi’s great grandson, said something to me about the philanthropy of the uber-wealthy that I won’t soon forget:

“They are sitting in five-star hotels sipping on coffee and they are talking about poverty. What do they know about it? They haven’t even smelled poverty.”

Maybe it’s more comfortable for the ultra-rich to focus on animal suffering and suffering of people who don’t exist yet because they don’t have to deal with the suffering of the world they have helped shape, and which rewards them so much.

Parts of EA have gotten progressively tech-broish. It’s overly-focused on math, reducing humans and meaningful lives and suffering to statistics. I get the need to focus on the future, even when suffering exists now, as long as thinking too far into the future, the focus of MacAskill’s new book on futurism, doesn’t distract us from attending to and helping the humans we share a world with now.

The AI thing really loses me. The EA community has often given it more thought and resources than working on climate solutions. Some billionaires are creating an AI future, while others, including SBF, are trying to prevent AI from eradicating humanity. Think Matrix and Terminator. I think most billionaires are so insulated and out of touch with the real world that they should stay out of the affairs of us mortal men. After all, any time the Greek Gods came down to earth, they just fucked things up even more. (Note: I don’t think billionaires are Gods, but they certainly are treated as such in our predominant form of capitalism.)

I also struggled with EA’s focus on animal welfare. Not that animals shouldn’t be treated more humanely. Ninety-percent of animal agriculture treats animals horribly and harms our world in a variety of ways. Many EA funds aren’t going to support proper animal agriculture, but instead to ending animal agriculture. We need animals as part of regenerative farming systems, but that’s my next book.

The Need for “effective altruism”Parts of EA drifted from its origins, but to say that EA is the problem because of its role in the creation and association with SBF is to ignore the immense good it has done. I’ve sat in the living rooms of Kenyans who received direct cash payouts from Give Directly, an organization supported by the EA community. The people I met had their lives changed forever. For the first time they didn’t have to worry about how they were going to find their next meal, and they could work toward a dream and put an unrealized skill and talent to work.

The way we give needs to be challenged. EA is challenging it. We need to give more and give smarter. All giving isn’t equal and some is harmful. Many of us don’t know the difference.

Giving more and giving effectively aren’t goals that should change because of the bad behavior of one person. Effective Altruism, the movement that requires the term to be capitalized and has a fancy centralized office has its flaws, but working toward and supporting “effective altruism” that seeks to reduce human suffering is still a worthy goal we should all strive toward, and one that Effective Altruism can still play a critical role in.

Still Curious?Calculate the impact your income can make using Peter Singer’s impact calculator.

Listen to the episode of The Good People podcast in which I interview the Joe Huston, the CFO, of the Give Directly.

Read my book Where Am I Giving? to learn how to give in an effective way that connects you with your local and global communities. You have a lot more to give than money.