Pat Schneider's Blog

May 20, 2019

My Interview on Aging with Tara Backes for her “Ageless Women” series

I was honored many weeks ago to be interviewed by Tara Backes for the Ageless Women online summit. She’s graciously sent me a copy of the video she made; I’m sharing it with you here. The interview is about 40 minutes long. Enjoy!

Peter’s poem “Lost in Plain Sight” on “Poetry in America” today

It’s been a long time since you’ve heard from me – we’ve had some health challenges here over the winter.

I’m delighted to be sending out this news today – Peter’s poem “Lost in Plain Sight” is the poem on Ted Kooser’s “Poetry in America” today!

This is a big deal! Newspapers carrying the column download it as a PDF and run it on their usual print schedules; subscribers will receive it electronically. Current readership is about 4.6 million people.

People in 71 countries now receive the column: Nepal, Indonesia, Uganda, Bangladesh, Australia, New Zealand, Peru, Egypt, Tunisia, most of Europe, Mexico, India, The Philippines, Turkey, China, Canada, Viet Nam, South Korea, Myanmar, the Tarawa atoll, Argentina and the U.K., as well as U.S. readers from Maine to Hawaii.

Also recently a friend of ours created this lovely video where Peter and I are both interviewed, recite some of our work, and recall how we first met; it includes Peter reading this poem.

Pat & Peter from Steveg1000 on Vimeo.

And here is Peter’s beautiful poem:

LOST IN PLAIN SIGHT

by Peter Schneider

Somewhere recently

I lost my short term memory.

It was there and then it moved

like the flash of a red fox

along a line fence.

My short term memory

has no address but here

no time but now.

It is a straight-man, waiting to speak

to fill in empty space

with name, date, trivia, punch line.

And then it fails to show.

It is lost, hiding somewhere out back,

a dried ragweed stalk on the Kansas prairie

holding the shadow of its life

against a January wind.

How am I to go on?

I wake up a hundred times a day.

Who am I waiting for,

what am I looking for

why do I have this empty cup

on the porch or in the yard?

I greet my neighbor, who smiles.

I turn a slow, lazy Susan

in my mind, looking for

some clue, anything to break the spell

of being lost in plain sight.

December 10, 2018

Narrative History – AWA – Part IV

PEREGRINE

One of the funnier things that occurred in the entire history our organization had to do with the fourth issueof our literary journal. Before we had a “press,” there was Peregrine.

The dream of a journal followed upon the formation of our budding organization: what had been simply my own workshops was growing into a community of people, some of whom had dreams beyond my own. We named ourselves Amherst Writers & Artists; Elizabeth Finn (French) wanted to lead art classes, Ani Tuzman wanted to lead a workshop for children, and simultaneously, Walker Rumble and Elizabeth wanted to found a literary journal. It became clear to methat I could not personally handle everything that was fermenting, and so I drew together a few of my closest friends among the writers in my workshops,and asked them to act as a Board of Directors. We decided there would be no decision other than by unanimous consent.

In1983, when the first issue was ready to go to press, we needed a name for the journal. After a first suggestion failedto get unanimous consent from the Board, Elizabeth Finn suggested “Peregrine.” Our first reaction was, “huh?” Elizabeth told us that not only was the peregrine falcon an endangered species, not only had a sheltered nest and a mated pair been placed on top of UMass’s new library building, but also the word meant “pilgrim.” We accepted the title. (By the way, the nested pair have now produced so many little peregrines, they feed on the mourning doves at my window birdfeeder – not my idea of ideal bird food!!) That first issue was only 35 pages, saddle-stitched (stapled) and sold for $3. We called our press “Amherst Writers & Artists Networks Press.” Walker and Elizabeth did all of the editing; Sharleen Kapp, our new Board chairwoman, managed production, Elizabeth designed the cover of the first two annual issues, reversing the brown and cream elements in the two. For the third and fourth issues, we asked Margaret Robison, an area artist, for cover art, increased our pages to 74, dropped“Networks Press” and named Peregrine“The Journal of Amherst Writers & Artists.”

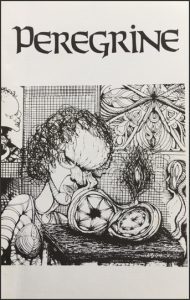

Sharleen is a brilliant, funny, and very clear-headed woman – single mother of five who had risen to the top of the design department of Massachusetts Mutual Insurance Company, known throughout the valley as “Mass Mutual.” In that role, she had access to the entire design department in the basement of their huge building in Springfield. She had taken each of the first three issues of Peregrine into MassMutual, given it to “the guys” in the basement who copied it at night and turned it into a journal. When it came time to print the fourth issue, Sharleen and I were a little too giddy with the brilliance and importance of what we were doing! We decided to ask the absolutely most famous artist in our area for cover art for our journal (whose wife, Peggy Gillespie, just happened to be in my workshop.) Gregory, whose work hangs in theMetropolitan Museum in New York City, responded graciously, “Sure! That dresser is full of images – you can use any one you want!” Sharleen and I went through drawer after drawer, image by image, and silently put them down. Every one – in Gregory’s inimitable style, and to our eyes definitely high art – nevertheless included naked body parts, not erotic, but in very explicit detail. It was 1984, both Sharleen and I were middle-aged women who truly wanted to be artistically and culturally “cool,” but we couldn’t put body parts on the cover of our journal. Finally we came to a slide that, held up tothe light, seemed to be a woman seated at a table on which lay a fruit of somekind. We sighed in relief and Sharleentook it to the guys in the basement of Mass Mutual and went upstairs to her desk. Whereupon one of them called her and asked, “Have you looked at this image?” She answered, “Yes.” “Well,” he said, “We think you should come down and look at it again.” She did. The object on the table was not a fruit. It was a bisected body part.

Sharleen and I first were appalled, then we laughed, and fairly quickly decided to vote on the side of art. “Go ahead and print it,” we said. And they did. Soon after, we asked Barry Moser, an equally celebrated local artist, if he might have an illustration of a Peregrine falcon that we could use. His image has been on every issue since. Our secret is, he didn’t have a Peregrine, but his turkey vulture serves beautifully!

Please note: this post was originally published without the illustrations. Apologies of the webmaster for the oversight.

November 29, 2018

Narrative History – AWA – Part IV

One of the funnier things that occurred in the entire history our organization had to do with the fourth issue of our literary journal. Before we had a “press,” there was Peregrine.

The dream of a journal followed upon the formation of our budding organization: what had been simply my own workshops was growing into a community of people, some of whom had dreams beyond my own. We named ourselves Amherst Writers & Artists; Elizabeth Finn (French) wanted to lead art classes, Ani Tuzman wanted to lead a workshop for children, and simultaneously, Walker Rumble and Elizabeth wanted to found a literary journal. It became clear to me that I could not personally handle everything that was fermenting, and so I drew together a few of my closest friends among the writers in my workshops, and asked them to act as a Board of Directors. We decided there would be no decision other than by unanimous consent.

In 1983, when the first issue was ready to go to press, we needed a name for the journal. After a first suggestion failed to get unanimous consent from the Board, Elizabeth Finn suggested “Peregrine.” Our first reaction was, “huh?” Elizabeth told us that not only was the peregrine falcon an endangered species, not only had a sheltered nest and a mated pair been placed on top of UMass’s new library building, but also the word meant “pilgrim.” We accepted the title. (By the way, the nested pair have now produced so many little peregrines, they feed on the mourning doves at my window bird feeder – not my idea of ideal bird food!!)

That first issue was only 35 pages, saddle-stitched (stapled) and sold for $3. We called our press “Amherst Writers & Artists Networks Press.” Walker and Elizabeth did all of the editing; Sharleen Kapp, our new Board chairwoman, managed production, Elizabeth designed the cover of the first two annual issues, reversing the brown and cream elements in the two. For the third and fourth issues, we asked Margaret Robison, an area artist, for cover art, increased our pages to 74, dropped “Networks Press” and named Peregrine “The Journal of Amherst Writers & Artists.”

Sharleen is a brilliant, funny, and very clear-headed woman – single mother of five who had risen to the top of the design department of Massachusetts Mutual Insurance Company, known throughout the valley as “Mass Mutual.” In that role, she had access to the entire design department in the basement of their huge building in Springfield. She had taken each of the first three issues of Peregrine into Mass Mutual, given it to “the guys” in the basement who copied it at night and turned it into a journal. When it came time to print the fourth issue, Sharleen and I were a little too giddy with the brilliance and importance of what we were doing! We decided to ask the absolutely most famous artist in our area for cover art for our journal (whose wife, Peggy Gillespie, just happened to be in my workshop.)

Gregory, whose work hangs in the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, responded graciously, “Sure! That dresser is full of images – you can use any one you want!” Sharleen and I went through drawer after drawer, image by image, and silently put them down. Every one – in Gregory’s inimitable style, and to our eyes definitely high art – nevertheless included naked body parts, not erotic, but in very explicit detail. It was 1984, both Sharleen and I were middle-aged women who truly wanted to be artistically and culturally “cool,” but we couldn’t put body parts on the cover of our journal.

Finally we came to a slide that, held up to the light, seemed to be a woman seated at a table on which lay a fruit of some kind. We sighed in relief and Sharleen took it to the guys in the basement of Mass Mutual and went upstairs to her desk. Whereupon one of them called her and asked, “Have you looked at this image?” She answered, “Yes.” “Well,” he said, “We think you should come down and look at it again.” She did. The object on the table was not a fruit. It was a bisected body part.

Sharleen and I first were appalled, then we laughed, and fairly quickly decided to vote on the side of art. “Go ahead and print it,” we said. And they did. Soon after, we asked Barry Moser, an equally celebrated local artist, if he might have an illustration of a Peregrine falcon that we could use. His image has been on every issue since. Our secret is, he didn’t have a Peregrine, but his turkey vulture serves beautifully!

September 29, 2018

STRANGENESS . . .

I am having a great time writing my “Narrative History” of Amherst Writers &Artists. I’m doing it as an introduction to the huge amount of Archives of AWA in the Jones Library, Amherst — newsletters, publications (We’ve published 39 books and a literary journal for almost 40 years!) — so much that it would be impossible for some grad student wanting to research our history to get a true “feel” of who we have been. And still are. I’m trying to provide the stories, my own and those of others willing to contribute their stories.

But yesterday morning before daylight I came downstairs and in the lovely dark –Kafka said even dark is not enough solitude for the writer. I came down to write, and was thinking about strangeness, how John Gardner said the most important thing in good writing is a quality of strangeness.

Last week, when Hurricane Florence moved over North Carolina, a letter came from an extended family member there. He is an artist making stunningly beautiful jewelry out of glass, Barry Summers, www.lettherebeglass.com. We had been exchanging thoughts about “strangeness,” and I had sent him a copy of my book, How the Light Gets In, which has a chapter on “strangeness.” His letter was about his strange experience with an artistic spider.

Barry is an artist with words as well as with glass, and — I confess it — to manipulate him into more writing, I had promised him story for story. His was about a spider in his front yard. She was building a web that stretched between trees twenty to thirty feet apart. Thinking that his landlord would be mowing the lawn and risked web-in-face, he considered taking it down. I’d like to think he also wanted to discourage the spider from further construction in the face of a hurricane. He took a long, thin pole and wound up the web. Whether this was an act of compassion for the landlord, the spider, the hurricane, or himself, is not clear. My responding story didn’t make it into my chapter on “strangeness.” It might reveal that side of me that is — well, weird.

[image error]

A good friend in my workshops and in the management of AWA, Nancy, told me that her husband’s father had died and his mother was in a nursing home. Their small farmhouse was in Norfolk, a beautiful suburban area, and it was unoccupied. I could go there for a week to write. I went, and it was as they said — old fashioned, comfy, a lovely place to write. I did for a couple of days. Then one day I wandered from room to room, looking closely at everything. On the walls of every room there were honorific framed plaques and papers praising the man for his participation and leadership in the Masons. Every room. I asked myself, where are the honors for his wife? On every floor there were handmade, braided rag carpets. Not commercial ones. I imagined, and still believe, they were her hand made rugs. I turned up the edge of one to look at the stitches, and saw that moths were having, and had been for a long time having, “their way with them.”

I went into the kitchen and went to the sink to make my lunch. I admit feeling very judgmental about the difference in the visible praise for their two lives. I was using a knife and noticed how it was worn down to a very narrow width. I held it in my hand, thinking of the many meals that woman had made standing at her sink. I was feeling connected to her — it is not too much to say I was loving her, when all at once she was in the room. I mean it — she was there, and she was furious. She did not want me there! Every hair on my body stood on end! I was being told to GET OUT!

I called Peter and told him to come and get me, ASAP! I packed my bags, gathered my papers and waited on the porch. Later I wrote a poem about it and gave it to Nancy. Later, her mother-in-law died and Nancy asked my permission to read the poem at the memorial service. That eased my feelings about the whole thing — even if the woman who used the knife didn’t feel I was honoring her, at least Nancy must have understood.

That is not the same “strangeness” as a spider building a web between two universes — but now that I say that, hmmm. Maybe there are some similarities!

August 22, 2018

Narrative History – Amherst Writers & Artists

INTRODUCTION

by Pat Schneider

Amherst Writers & Artists is one manifestation of what came to be known in and following the 1970’s as the writing process movement. Although its deepest origins are in books by two women, Dorothea Brande, 1934, and Brenda Ueland, 1938, they have seldom been recognized as the founding mothers of a new and profoundly more humane way of teaching writing. Before the 1970’s, a competitive, negative-response method was used almost universally. Then there emerged a groundswell of reaction. In 1973, Peter Elbow’s articulation of a new approach in Writing Without Teachers (Oxford University Press, 1973) became well known in academic settings; and starting in 1979, knowing nothing of Elbow’s work, I began to develop a new workshop method, non-hierarchical, non-classist, craft-based but specifically designed to eliminate shaming, belittling, and bullying in responses to written work—all of which were deeply engrained in the teaching of writing in schools, colleges, and universities. From second grade on through a doctorate, persons were being taught, both subtly and overtly, that they could never be “a writer.”

For the first twenty-five years its life, the community that named itself Amherst Writers & Artists (AWA) consisted of three related but somewhat separate parts: (1) entrepreneurial creative writing workshops; (2) outreach to under-served populations such as women in low-income housing, youth at risk, and the incarcerated; and (3) AWA Press, a small, independent press, publishing books of poetry mostly by writers in our community, and occasional books about our work. Two major events were influential: the publication in 2003 by Oxford University Press of my book on our method of writing workshop leadership, Writing Alone and With Others, and a companion film to the book titled Tell Me Something I Can’t Forget, made by Diane Garey and Larry Hott for public television by their international award-winning film company, Florentine Films.

All throughout its history, I have imagined and intended to write a narrative history of the organization—a compilation of memoir writings by myself and others who wish to contribute to it—to accompany AWA’s very large archive in the Jones Library, Amherst, Massachusetts. At one point I did write two short essays on the original roots of the organization in my own personal past, and fully intended to begin the next essay by researching the archived materials at the library as my reminder and major source material. However, life being what it is, time for that never came.

Now, many years later, in my eighties, I face my own limitations and understand that if anyone ever does a studied and researched history, it will not be me. However, it may be appropriate for me to write pieces of personal memoir of certain moments in our history, as an addition to existing archival materials. I have invited other leaders, past and present, to add their own remembrances by sending them to me or directly to Special Collections, Jones Library, Amherst, MA 01002.

THE BEGINNING DAYS OF AWA: 1979

Having just completed MFA degrees in Creative Writing at the University of Massachusetts, my friend, poet and artist Margaret Robison, and I both were facing major changes in our lives that required us to have an income. Margaret was seeking a divorce; my husband Peter and I were leaving the church after his twenty-five years as a United Methodist minister. We had always lived in furnished parsonages; we were facing no income, no home, no furniture. Margaret and I decided to start an independent creative writing workshop. I had the advantage of having been the director of publicity for the U. Mass theatre department for two years at the suggestion of one of Peter’s parishioners, Jim Young, at that time chair of the Department of Theatre at the University. After those two years of experience, I knew how to do publicity. Margaret designed a beautiful poster; I talked a local printer, Hamilton Newell, (also one of Peter’s parishioners) into printing them in exchange for our plugging his print shop. Margaret and I persuaded a local radio station, WRSI, to letting us do a weekly interview with famous local writers. (There is an almost inexhaustible supply in our five-college valley.)

It was such a rare thing for anyone—let alone women, in 1979!—to lead an independent writing workshop arts newspaper that The Valley Advocate carried a full cover photo of Margaret and me over a bold line: Two Women Start Writing Workshop.

In the last year of Peter’s work as a clergyman, we led a workshop in the parsonage. There we discovered that the method we had experienced as MFA students in workshops at UMass was not only a poor way to teach writing—it was positively disabling. Sitting around talking about what is wrong with a piece of writing, giving little or no positive feedback for the strengths in any piece of work, simply destroyed, rather than stimulating and encouraging good writing. We dropped that method entirely, offered participants a simple prompt, and asked them to write whatever came to mind. We gave responses that were only positive upon first reading, but gave thorough and careful questions, suggestions and encouragement when they brought in typed work in manuscript. The difference in the quality of writing we received was astonishing.

At the end of that year Peter and I were in a new home at 77 McClellan Street, Amherst , and Margaret was giving her time to the Poet in the Schools program. It was another two years before the workshop that I created alone began to develop into what became Amherst Writers & Artists.

July 18, 2018

A STORY I NEVER WROTE DOWN BEFORE

EPSON scanner image

Last week the count went up to three thousand on the evening news. Three thousand children separated from their parents and removed to detention centers and foster care all over the country. No records kept of parent/child identities. Three thousand. Children.

All at once I am eleven years old. Writing these words, my stomach turns. Something deep inside wakes up, alert, afraid. My breath gets short.

I was eleven when I stood with my nine-year-old brother in the admissions office of the orphanage, being admitted. He would become “Sam” as an adult. Then, he was “Samuel.” I was “Patsy.”

We had been living in one room on Pine Street in St. Louis. Mama had moved us there because it was “a nice neighborhood.” Brick homes, a tree-lined street. But our room was in the basement, in the back of the house. It was separated from the rest of the basement by a loose door. On the other side there was a furnace and an open coal bin. In our room there was a coal stove in the center of the space, a hanging light bulb on each side of the stove, one bed for the three of us, a hot plate, a small sink unattached to the wall, and three small windows up near the ceiling, at ground level outside. But the neighborhood was nice.

One day the woman who owned the building and lived upstairs pounded on the door to our room. “Get out!” She screamed at our mother. “Get out! You are filthy! You have brought roaches into our home! Get out!”

In truth, we probably had. I have wondered about that woman. Did she not see the children in the room? Did she not care that they were there, listening? Three thousand. Children. Watching. Listening.

In the admissions office, I remember standing close to my brother. My mother was there. An older woman behind a desk, a younger woman, taking notes. Next to me, close to me, Samuel. Many years later, in my fifties, I went back to the orphanage, and got some of the records. The woman taking notes, wrote: “Patsy did not take her hand off her brother throughout the entire interview.”

[image error] The newspaper details an incident in which a twelve-year-old-girl wants to hug her ten-year-old brother, “to reassure him.” She is told she cannot touch her brother. In the orphanage, I was not allowed to see or talk to my brother. He lived in the “boy’s cottage.” He sat at one of the boy’s dining tables at the far end of our common dining hall. I could see his yellow hair, but I could not go where he was. I have never written these things before. I do so now to say, “don’t they see? Don’t they know the children are even there?” I am eighty-four years old. These memories are still raw sores in my psyche. I have come to understand that my mother had nowhere to go. She said it was for my own good, so I would learn “good table manners.” I understand now that what she meant was, I would learn how to cross class. And I did. And I suppose it was for my own good. But they kicked my brother out in a few weeks, and he experienced the worst of things in a foster home. Three thousand children are being placed in “foster care” and detention centers. Their hurt is for a lifetime. People, we have to see. We have to act. We have to care. My way is to write notes of protest or thank you to people who act for the things I believe in. One helpful way to do that is at the Americans of Conscience Checklist, at https://jenniferhofmann.com, which gives me well-researched information and exact addresses.

July 5, 2018

AN INVITATION TO SEND WORK TO A BRAND NEW JOURNAL!

[image error]Forty-some years ago, in the early days of Amherst Writers & Artists (AWA), one of the founding editors of our literary journal Peregrine, Walker Rumble, along with Karen Donovan, started up their own small journal, Paragraph.

This magazine had many fans, and a long run. Now Editor Elizabeth George and artist Adell Donaghue, through Simian Press, will be launching LINEA, a journal of previously unpublished paragraphs of fiction.

LINEA will be similar to Paragraph, but with its own unique, artistic flair. Co-editor on the project is my good friend and another early dreamer of our work together in AWA, Carol Edelstein.

Let’s offer work for the premier issue of LINEA!** (More information from Carol and Elizabeth below). (**Marge Piercy says “never say ‘submit!’– say ‘offer!'” You go, Marge, girl!)

With best wishes,

Pat Schneider

______________________

[image error]

Linea

is a linen thread; the warp and weft during weaving; a fishing line; a plumb line; a bowstring; a geometric boundary; the long markings, dark or bright, on a planet’s surface; a line of thought; an outline; a sketch.

Linea is a literary journal of short fiction published by Simian Press. We celebrate the literary snapshot, the atmospheric vignette, the emotion jotted in the margin, the lives, characters, moods and settings that come alive within narrow straits.

We invite you to offer your previously unpublished short fiction for the inaugural edition of Linea, to be published in the fall, 2018. Edited by writers Carol Edelstein and Elizabeth George and designed by artist Adell Donaghue, Linea promises a cornucopia of fiction, taut, crisp, breviloquent, and lovely, as well as illustration artfully designed using both modern letterpress and digital technologies.

Work is accepted via email to egeorge115@me.com. Please limit your pieces (no more than 3) to 180 words, using twelve-point Times New Roman type, single spaced, in block text format (single paragraph, no indentation, spoken word embedded). In addition, please send us your postal address and a brief biography. The submission deadline is August 1, 2018. Contributors will receive a complimentary copy.

We look forward to hearing from you!

Elizabeth George

Carol Edelstein

[image error]

June 20, 2018

Pat Schneider’s Blog – June 2018

Something quite wonderful has just happened, and it moves me to celebrate the work of my husband, Peter Schneider. Yesterday he received a letter from Poet Laureate,Ted Kooser, asking permission to use Peter’s poem, “Lost in Plain Sight” on American Life in Poetry, which “reaches 1.5 million readers in newspapers and on the web!”

To read his poem, go to: LOST IN PLAIN SIGHT

Although he has a beautiful book of poems, Line Fence, and we are in the process of publishing a new collection, Below the Remembering Mind, Peter does not think of himself as a poet. Nor does he credit himself for his 25 years of work in our farmhouse basement, managing all of the business of Amherst Writers & Artists.

It was 1990. We had left 25 years of his work pastoring Methodist churches, and he had followed that with ten years in a business he founded with lawyer Michael Pill, responding to the need for turbines in small dams in New England. He retired from that work and joined me in AWA at the point in 1990 where the organization was growing into an international fellowship of people trained in our method.

Through the next 25 years, Peter jokingly called himself “the old fart in the basement”, and always responded with surprise when someone commented that our entire organization rested on his management of more than a dozen volunteers working in and out of our basement at all hours of the day and night.

He is a beautiful, humble, brilliant poet and clarinetist now, 87 years old, and not at all “lost in plain sight” to the rest of us!

Peter in clarinet tee shirt

Peter Schneider & Emily Savin in Concert, 2017

LOST IN PLAIN SIGHT

by Peter Schneider

Somewhere recently

I lost my short term memory.

It was there and then it moved

like the flash of a red fox

along a line fence.

My short term memory

has no address but here

no time but now.

It is a straight-man, waiting to speak

to fill in empty space

with name, date, trivia, punch line.

And then it fails to show.

It is lost, hiding somewhere out back,

a dried ragweed stalk on the Kansas prairie

holding the shadow of its life

against a January wind.

How am I to go on?

I wake up a hundred times a day.

Who am I waiting for,

what am I looking for

why do I have this empty cup

on the porch or in the yard?

I greet my neighbor, who smiles.

I turn a slow, lazy Susan

in my mind, looking for

some clue, anything to break the spell

of being lost in plain sight.