B.W. Haggart's Blog

October 12, 2024

Writing with Sensitivity

Sensitive Writing

Being a published author has been a wonderful, fascinating, and at times, surprising experience for me. Recently, these unexpected episodes came in three notes. A few weeks ago, I received an email from a reader suggesting I read an article, How to Make Your Writing More Sensitive–and Why It Matters by a freelance writer, Melissa Haun.

https://www.websiteplanet.com/blog/sensitive-writing-guide/

On the heels of that email, another reader pointed out that my heroine, Cassie, in

Stealing Time, called an attempt to pack the family coach a “Chinese Fire Drill.” She wrote:

“Being of Asian descent, this reviewer was taken aback by the use of the dated phrase “Chinese fire drill” which has offensive overtones to me. In rating this book, I have made the assumption that the author had not considered this aspect in language used.”

Which was true. I hadn’t considered that aspect. Within the same week, my writing program, ProWritingAid, added its observation regarding sensitivity. When the hero in my new manuscript characterized the heroine as a “pugnacious, demented female.” A drop down note immediately cautioned, “Inclusiveness: This may imply a bias against those with disabilities.” Obviously, out of context in this case, but still, this effort to be sensitive to reader concerns is now part of writing programs.

Heaven knows I have no interest in ignoring sensitive issues, being insensitive or hurting anyone’s feelings with my writing. If nothing else, ignoring such things is hardly conducive to entertainment—at least the kind I am interested in creating. Clearly, the universe wanted my attention. The reader who sent me Ms. Haun’s article felt following her suggestions would increase my readership. I’m all for that.

Add this need for inclusiveness while avoiding being insensitive to others’ feelings, several readers have given my novels one or two stars for one failing: The complaint has been the novels contain swearing, crass words.

I can understand the confusion over content. Having written sweet/clean novels, and some with a middling-to-fair amount of swearing, violence, and sex, I now specify the ‘heat’ content in each novel as part of their description.

Being sensitive to reader needs and wants in their reading covers a lot of ground, which Ms. Haun acknowledged. She put a huge amount of thought into her excellent article—with diagrams. The article is specifically for writers, so I paid attention. Here is the summary graphic for what she sees are the basic considerations:

Following the graphic, she writes:

Categories & Examples of Sensitive Content

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s get more specific. There are several different areas where sensitivity is especially important. We’ve divided them into a few broad categories to give an overview of how to approach each one. These aren’t the only areas where sensitivity matters, of course, but they’re the ones that most commonly come up in our content:

· Race & Culture

· Sexism

· Gender Identity

· Sexual Orientation

· Disability & Ableism

· Appearance

· Age & Lifestyle

· Politics & Religion

In her article, Ms. Haun did a fine job exploring the specifics in each listed area of concern, so there is no need for me to repeat them here. Read the article.

My question is how can or should all this be dealt with in a novel? Ms. Huan’s descriptions and examples focused on narratives, whether fiction or nonfiction. Yet, there are characters too, and their take on the world may be decidedly insensitive, particularly if illustrating different cultures and eras. Let’s use Stealing Time and its main characters as our case in point. The story is about a cat burglar thrust back in time to the Regency period. Between her Brooklyn upbringing as a foster child, criminal activities, and the British culture during the early eighteen hundreds, nearly all of the sensitive areas listed above come into play during the story.

Narrative:

It is comparatively easy to ‘police’ your writing when describing people, places or things. It comes down to what words authors are using either in their adjectives such as ‘demented’ or comparison such as ‘Chinese fire drill.” These are easy to change, deleting the offending words or substituting something less triggering. However, there are more difficult parts of a story.

Ms. Huan notes context and inference can cross the line, suggesting things that amount to insensitive assertions. I can say some situation is ‘worse’ rather than changing, or emphasize a particular detail over another, say a man’s anger over a woman’s irritation, though both emotions are supposed to be of equal intensity. I say these issues are comparatively easy to address only in relation to the characters in the novel.

Characters:

In the cases of demented and Chinese Fire Drill, they weren’t my narrative descriptions. They were in a character’s Point of View, cat burglar Cassie’s and a Regency era ‘gentleman.’

I’ve been in Brooklyn several times, and I can verify that ‘Chinese Fire Drill’ is a common descriptor heard there. It is ‘in character’ for Cassie to use it. That doesn’t mean the author should. The writer can easily scrub it, just like any other insensitive term.

The problem is this: Cassie is an ‘insensitive’ character, from the streets, a criminal, fairly hardened by life. Does Cassie remain the same character if I soften or eliminate her insensitive edges altogether?

I have received suggested answers to this question. One is to smooth rough edges ‘just enough.’ A delicate balancing act. Another is to have other characters correct her behavior, or even the narrator. Depending on the transgression, Regency culture, as patriarchal as it was, may not realistically harbor characters who could chastise Cassie for her poor behavior. As the narrator, I can slap Cassie’s hand when she’s being bad, but that can be rather intrusive in most point-of-view modes other than omniscient.

A third idea is to have her recognize her lack of empathy during the story. While that happens in Stealing Time, she has to have her ‘Chinese fire drill’ moments if she is going to be shown to grow out of them. Of course, part of Cassie’s insensitivity is being dropped into a different culture. In this case, the Regency era, which had its own list of striking insensitivities.

The Environment:

British culture during the early nineteenth century blithely stomped across our culture’s ‘sensitive parts’ with big boots. The prevailing attitudes towards women, sex, the mentally and physically impaired, race, the ‘lower classes’, gender identity, religion, and politics would curl the hair of even marginally aware members of our twenty-first century society.

Obviously, everything can depend on how such insensitivities are avoided or represented, just like any narrative or character descriptors.

Here is a scene from Stealing Time where Cassie is confronted by blatant misogyny and implied racism. Cassie is being lauded for her climbing ability when the hero, Ross approaches the group of men surrounding her at a ball:

***

As he came up behind them, he could hear them praising her climbing performance and her dancing.

A large man, his collar high enough to wedge itself under his large ears, spoke with an authoritative air on women and climbing.

“You must admit, Contessa, that your talent and skill are exceedingly rare among the weaker sex. What other woman could possibly succeed as you have?”

Ross could guess what Cassandra was thinking about the condescension in the compliment, and her reply confirmed his suspicions.

“Why, Colonel Adderhatch, I doubt that many men could either.”

The Colonel cleared his throat, eyeing the other men, who were enjoying his discomfiture. “Yes, rather. Yours was an extraordinary feat.”

Another young buck, sporting an embroidered red vest said, “So, how did you accomplish it? What techniques did you employ?”

Before she could respond, an older gentleman, with the bearing and potbelly of an experienced Parliamentarian, stuck his thumbs in his waistcoat pockets and said, “Tut, tut there, Downey. Quite an unfair question, my boy. You can not expect the woman to know how to explain the technical skills involved. Far outside a woman’s ken. Common knowledge and all that.”

Ross winced, embarrassed for Parliament. For a politician, the man wasn’t particularly politic.

Downey blinked. “But Mr. Stellerby, how did she . . .”

“Instinct, boy, instinct. She is blessed with a natural talent. Can’t be taught, don’t you know.”

Kerrington watched Cassandra’s eyes darken as her lip curled ever so slightly. A set-down was brewing. He was about to intervene when another, more stately man, spoke up.

As though tutoring the now embarrassed Downey, the man said, “A woman’s understanding is limited in many ways. It is unfair to expect more of them than they can provide, particularly from the darker, southern European nations.”

Several others nodded sagely and murmured “Quite right, Lord Litton, quite right.”

Downey appeared totally undone and on the verge of apologizing to Cassandra for his unfair question when she removed her hand from Tate-Murray’s arm and laid it on Downey’s sleeve. She shook her head sympathetically, but Kerrington saw that devilish gleam in her eye and recognized the set of her jaw. He held his breath, bracing himself for what she might say, caught between apprehension and anticipation.

She laughed lightly and said to young Downey, but included the rest of the men, “Do not trouble yourself, Mr. Downey. Adam had much the same questions concerning women.”

The rotund politician chuckled and said, “And how is that, my lady?”

“Well, I guess you haven’t heard the story.” She leaned in and the men leaned closer to hear her. “In the Garden of Eden, Adam went to God one day to ask him why he had made the woman Eve the way he had.” Several men smiled and said they hadn’t heard it. “Well, as they walked in the Garden, Adam asked God, ‘Why did you make women so beautiful?”

“God answered, ‘So you would like them.”

Cassie began acting out the parts. She made Adam a rather vague character. “Then why did you make them so soft and cuddly?” The men chuckled at this, looking at each other with near leers on their faces. Ross kept his face blank and crossed his arms tight to keep from planting some facers. Cassandra grinned as though she was sharing their secrets, which made Ross want to shake her instead.

“God answered,” Cassie said in a deep voice, “’So you would enjoy holding them for your comfort.’”

“’Yes, it is all very nice,’” said Adam, “’but why, why did you make them so stupid?’”

The men roared their laughter, but Cassandra held up a hand and they quieted immediately. She spoke quietly among the crowds, so the men leaned in further to hear her next words.

“‘Well, my boy,’ God said, ‘I wanted them to like you too.”

There was a silence, which was broken by a quiet chuckle from the young Downey, and a coughing guffaw from a couple of men in the back, but the rest continued to frown at each other as though they’d missed the punch line. Ross clenched his teeth to keep from laughing, not only at the joke, but also at the dazed expressions exhibited by several of the blowhards in the group.

***

There is a great deal of insensitivity [i.e. lack of empathy] going on in the scene, perpetrated by several people, including Cassie towards most of the men with her joke. She does reassure poor Mr. Downey, her empathy appearing as a strength. In contrast, Mr. Downey’s was ‘troubled’ by his empathy for Cassie, but comes across as hesitant, and let’s admit it, weak.

The question here is whether the reader will find the scene insensitive. Women readers may have been the target of similar remarks concerning their abilities as women. Am I being insensitive to portray that reality? What about a reader’s feelings about their religion? Have readers felt the scene made light of their beliefs? And of course, there is the punchline of the joke which is pure man-bashing. Those paragraphs are brimming with potential offensive issues.

Referring to the ‘Mental Checklist’ graph above, this one scene hits three of the four issues listed:

#2. “Are my views influencing the way I am treating the topic?” Well, duh. Hard to avoid this one. Being self-aware of one's views is mandatory in this case, as well as the readers' views. But should the hero and heroine be equally self-aware? They were to some degree in the scene, but enough?

#3. Am I minimizing or exaggerating the importance of the topic. The attitudes and relations between men and women are important issues in the above story. It is a romance, after all. The characters may enhance or diminish the topics within the parameters of the story environment, but is that enough ‘balance’ for today’s readers?

#4. Does what I’ve written show respect towards those affected by this issue? How do I tell? Ms. Huan suggests asking others who might be affected. A good idea. There are two complications. One is the number of issues which might surface in a scene, let alone a story. Look at the number in just that one passage I provided. The second is who or how many writers and readers you ask about such sensitive issues. Not all those affected will have the same views, some more representative than others, some more sensitive than others. Just as an author can’t please every reader with their story, a writer will offend someone sometime, regardless.

Ms. Huan writes:

It’s true that this level of consideration and critical thinking requires extra work, but it’s worth it. And the truth is that there isn’t actually any other option. Every choice we make in our content will reflect a certain position

Yes, extra work and yes, in the end you can only realistically do what Ms. Huan points out: “This is why it’s so important to evaluate everything on a case-by-case basis.”

I agree with her: such considerations are vital. None-the-less, it makes me feel tired at the thought of doing this methodically on top of all the other methodical challenges inherent in writing a story. This is particularly true when she points out that “there’s no such thing as truly neutral language.” (She bolded those words.) Writers can try creating neutral passages at different points in their books, but in making those choices, the purposes are not neutral in intent. Kind of a Catch-22 balancing act.

Conclusions?

Ms. Huan ends with this equation: “Empathy + Flexibility = Sensitivity.

She states, “. . .we recognize that they aren’t all hard-and-fast rules, and the “right” way to write something often depends on the context of each situation. This is why it’s so important to evaluate everything on a case-by-case basis.” Again, that is the only way to deal with the issue in one’s writing outside one’s experience. My family recently reminded of that approach as well as asking the views of others who might be affected.

Ms. Huan concludes,

“If you’re ever in doubt about how you should represent a certain individual or group, the best thing to do is seek out their perspective . How do they prefer to be portrayed? What words and ideas do they find offensive? Not all members of a given group will agree on these things, but you can always try to find a consensus or a recommendation from a trustworthy source. It’s true that this level of consideration and critical thinking requires extra work, but it’s worth it. And the truth is that there isn’t actually any other option.

There are a few other options open to writers. Other writers and editors, more experienced with these issues can also help, on a professional level, regardless of their personal experience with the topics. There are actually editing programs such as the one I use that can mechanically identify sensitive words or ideas. There are writing programs available that are specifically designed to perform this kind of screening. Like all kinds of editing, a writer tries to catch all the problems with content, grammar and line errors. This editing for sensitive issues is just one more type of necessary proofreading.

June 12, 2024

Recognizing Fascism Today: A Historical Perspective.

“It will be seen that, as used, the word ‘Fascism’ is almost entirely meaningless. In conversation, of course, it is used even more wildly than in print.”

--George Orwell 1944

RECOGNIZING FASCISM TODAY: A Historical Perspective.

I avoid politics with my blogs, sticking to history and writing. However, I am going to make an exception, if an historical one. The words ‘Fascist’, ‘Nazis,’ ‘Authoritarian’ and ‘Totalitarian’ have been hurled about by both political parties, social media pundits, and talking heads, calling one side or the other Fascist, Nazi, and sometimes both Fascist AND Communist, [which is seriously silly].

I felt compelled to provide a historical grounding for those terms. What they were when created. Most importantly, I want to offer a way to recognize such political movements in the world today. Any confusion only neutralizes the ability to identify them, understand what they are, and combat their efforts. The intent here is to provide a little history of Fascism, give meaning to the word so as to recognize it for what it is.

The Beginning

Fascist and Communist nations were first created in the early 20th century. Both Fascism and Communism are Authoritarian political movements and/or governments, so they share some traits. Both create dictatorships, one man rule, the central government dictating all politics, the law, the economy, and policy for the whole nation. If these governments become extremely authoritarian, they are considered ‘totalitarian.’ Their control of a country is absolute, regulating every aspect of a citizen’s daily life. George Orwell’s novels 1984 and Animal Farm both describe such movements and governments. The North Korean government today is a horrifying, near perfect example of a totalitarian regime.

When a Communistic movement or government forms, as it did in the early 20th century, it was created in direct opposition to the current form of government, which it defeats by coups, usually by violence or war. Politically, it is a radical leftist movement. It creates one man rule, dictators. Most people can name the dictators of today’s major Communist governments. However, some like Putin’s Russia is basically a Fascist state in form and function, regardless of any ‘communist’ trappings. I’ll explain as we go along.

As a radical right political movement, Fascist movements or governments are always born in a functioning democracy, and come to power because of and through that form of government. Once in power, illegal means are employed to stay in power, destroying any democratic institutions.

This was true of Fascists in Italy in the 1920’s [where we get the term Fascism] and in the 1930’s, the Nazis in Germany. And like Communist dictatorships, most people recognize Hitler and Mussolini as the dictators of those Fascist governments. Der Führer and Il Duce both mean ‘the leader.’ Those two men were seen as the government and the national exemplar. Surprisingly, that is exactly how Putin, along with Hitler and Mussolini came to power, through Democratic means. On 31 December 1999, following the resignation of President Boris Yeltsin, he was appointed Acting President. He was first elected President of Russia three months later on 26 March 2000.

It is ironic that the legacy of the United States Constitution can be seen among both Communist and Fascist governments today. They all have a constitution, a parliamentary form of government, and elections, but they are window dressing, not democratic or republican in function. When an election is called, the winner is predetermined as it is in Russia and China today. Any elected assembly is no more than a rubber stamp for the dictator’s policies.

The Characteristics of a Fascist Political Movement

Here is a template for recognizing a Fascist political movements and governments. It is true that the behaviors or aspects of politics detailed below are seen in any society, one behavior here, another there. In stark contrast, a Fascist political movement or government is not hard to identify. A Fascist movement or government will display all of the following characteristics and behaviors beginning with Italy and Germany:

1. One Leader: Fascist movements form around an individual. He or she is seen as a powerful expression of the national spirit, a savior in dark times. He is the only solution to the nation’s ills, real or imagined. The leader IS the political party or organization, his whims are literally policy. This belief is not hidden. It is publicly declared as Mussolini did. “I am the only one who can solve your problems.”

2. The Threat and The Promise: The Fascist message is that the nation is failing, being destroyed, the national greatness has been lost, actually stolen, or being stolen. The world is going to hell and bad people are the reason. The Leader and his party promise to reclaim that greatness, defeat these enemies of the state. This was Hitler’s and Mussolini’s promise. The country’s deserved place in history will be restored, whether the thousand-year Reich or the new Roman Empire. This is Putin’s continued promise: Restore the Russian Empire and national pride.

3. The Return to The Past. The nation’s past is held up as the ideal to be realized again, vague as that might be. Often this idyllic past is created whole cloth. The nation’s past is viewed as where the nation’s greatness resides. Patriotism is emphasized. Fascism is radically conservative in this sense, looking back to a venerated history. The new Roman Empire or Third Reich will restore the nation.

4. Anger: Fascism is an angry, aggrieved movement. outraged that national greatness has been lost, resentful that it was stolen by supposedly privileged or underhanded groups. Surprisingly, it is always the same groups, regardless of the country. Whether Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy, or fascists today—or Putin’s Russia. It is the political left, liberals, Jews, foreigners/immigrants, intellectuals, homosexuals, ‘the elites,’ and Communists are ‘The Problem.’ These people are diluting the purity of the nation and stealing the nation’s vitality. They must be segregated, expelled, or eliminated from the national landscape to save the nation.

5. Fear: The Fascist movement plays on people’s fears. There aren’t problems to be solved, there are disasters looming, and total catastrophe is at hand. The message is “you are victims and will lose everything.” Victimhood is the prime message, the response when anyone opposes them. The Fascists are victims of a powerful enemy. Again it is the minorities, the political left, particularly those in government that are lurking behind a shadow bureaucracy taking advantage of true patriots. Both Hitler and Mussolini made this a central political theme, a theme still in use today. For Putin it is the Liberal West who is the enemy. He manufactures that threat, that tension by threatening the West himself.

6. Language: There are words and phrases that appear in every Fascist movement, often aimed at anyone or organization viewed as their opposition: Take any phrases from this article and you will see them openly repeated. The opposition are vermin, liars, corrupt, vile monsters, unholy, demons, radicals, an enemy of the people, and murderers, often accused of the most hedonistic acts, sexual and otherwise. In Germany the Jews ate babies. In Italy, the Communists were devil-worshipers. In Russia, the liberal West are ‘demons’, ‘sick deviants.’ [Actual words used by Putin and the state media] The effort is to dehumanize the opposition and those seen as the problem. For Hitler it was the Jews. For both Mussolini and Hitler, the communists. They are not real citizens, not moral humans, not even human like ‘us.’ Fascists decide who is a real patriot and who isn’t. Fascists take any accusation of ugly behavior and simply accuse the opposition of the same bad actions.

7. Symbols: Traditional, national, or cultural symbols are usurped, whether the swastika [an ethnic Germanic peace and good luck symbol] or the fascio [A bundle of rods tied around an axe, a symbol of unity from the ancient Roman Empire.]. Clothing of some sort will always be used to identify members, like the brown or black shirts and the armbands seen in Germany and Italy. Hitler actually copied Mussolini’s tactics such as these. The point is to be able to easily identify who are supporter and generate unity. People will create these ‘common’ items themselves.

8. Information: Germany’s Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels said, “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.” Somehow, they are easier to believe. Fascist movements attempt to shut down all sources of information but their own. This is done directly by violence or when in control of the government, by use of the law. Fascist tactics were also meant to generate a flood of lies, misconceptions, and false problems. Make the loudest, most spectacular claims in the national media. This wasn’t to induce citizens to believe the lies so much as to make it impossible to know the facts, to have their listeners say, “no one knows the truth, and everyone lies.” Because the lies come so fast, it is impossible to actually keep up with them, ferreting out the truth and disseminating it. In Russia and China today, most citizens know that the government lies about everything, but as intended, they stop attempting to discover anything factual. They stop caring, because of the difficulties in knowing the truth. It is also dangerous to disagree with Fascist’s ‘alternative facts.’ To ask the ‘wrong question’ immediately labels you as the opposition. The ultimate is “double speak” where it all becomes nonsense, “war is peace, “freedom is slavery, facts are opinion.” Meek acceptance is the desired result. The result of these tactics are illustrated in the novel 1984.

9. Loyalty: In the Fascist regime, devotion to the cause [That is, the leader] is the primary requirement for success in the movement and government. Because of this, less ethical and less competent people will do well as long as they agree with The Leader. Intelligent, questioning people will not. Ability is secondary and can be detrimental because that is a threat to party leadership. This invariably leads to two things: poor decision-making in government, and corruption. It was true in Germany and Italy. It is seen today in most all authoritarian governments such as Putin’s Fascist Russia. What results is a mafia-like state organization.

10. Political Methods: Because the national situation is depicted as desperate, the politics of threats, intimidation, lies about the opposition, and violence are seen as morally justified. Trucks flying party flags filled with party loyalists would cruise the German and Italian streets, intimidating citizens. Loyalists surrounded opposition leaders’ homes menacing or attacking them. Crowds threatening those labeled ‘bad actors’ were common. The opposition is accused of terrorism, including ‘false flag’ events such as the Reichstag fire in Berlin soon after Hitler took power. It was blamed on the Communists and justified martial law. Both Hitler and Mussolini created such terrorist attacks. Putin is known to use the same tactics. Beating, imprisoning, and killing the ‘opposition’ or ‘disloyal’ party members were and are seen. “Ought to be hanged or killed” was often heard, whether referring to the Jews, minorities, Communists, Liberals, or ‘disloyal’ citizens. The fear that Fascists stoked is incited by the very societal chaos their violent behaviors create. Things do begin to feel like the world is falling apart. The current government can’t solve the problems, real or fake. Fascist movements intentionally act to keep the government from functioning—within the government. Only the Leader can solve the problems.

11. The Democratic Process: Whether Germany or Italy, or current Fascist movements, they come to power through the country’s democratic processes, either voted in by the people or selected by their democratic administration. Once in power, while keeping the trappings of democracy and the vote, the democratic government is dismantled and any constitution is ‘re-written’ for The Leader, if not ignored, [Putin recently termed this “managed democracy in his Tucker Carlson interview] cementing his dictatorship. The Dictator stays in power through illegal means, creating a police-state, and using the law to put their opposition in prison or worse. It’s all necessary because of the disasters looming. This is often done in the open, not in secret —once the public has been prepared with lies, fear, and violence. They accept that democracy doesn’t work and what is needed is a strong leader. Putin regularly has the laws and Russian constitution changed as he sees fit.

12. Law and Order: Fascism presents itself as a champion of law and order. However, law is seen as a tool to enforce obedience and punish any opposition. Threats of imprisonment is a staple of Fascist movements. Again, they are overt threats, not some secret effort. Putin’s regime exemplifies this. His political opponents are arrested and die in prison, if not killed outright. It is all very public. The legal authorities are not charged with protecting life, rights, and liberty. They are an arm of the Fascist government to enforce compliance and eradicate any opposition. In a Fascistic government, even my putting this up on a website would lead to censorship at best, at worst. . . .

Historically, as it is today, Fascist and Nazi-like movements and governments demonstrate all of the above characteristics to some extent, rather than just a few.

"When fascism comes to America, it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross."

—Attributed to Sinclair Lewis, author of the 1933 novel, It Can’t Happen Here.

September 24, 2022

How to Recognize a Napoleonic Officer's Rank

Recently, I was reading an enjoyable Regency romance when I came across this description:

“He was strikingly handsome in his red coat. She could see the officer was a captain by the bars on his shoulders.”

Well, that popped me right out of the scene. Captains in the Napoleonic British Army, the various militias or any other continental army of the time did not have their rank designated by two metal bars on their shoulder tabs. Those are modern American Officer designations shown below: [Today’s British Army have similar insignia for their shoulder tabs]

There were no such metal insignia for distinguishing officer ranks in the Napoleonic British army. So, I decided to describe how ranks were displayed by the British [and basically all Napoleonic armies to some extent]

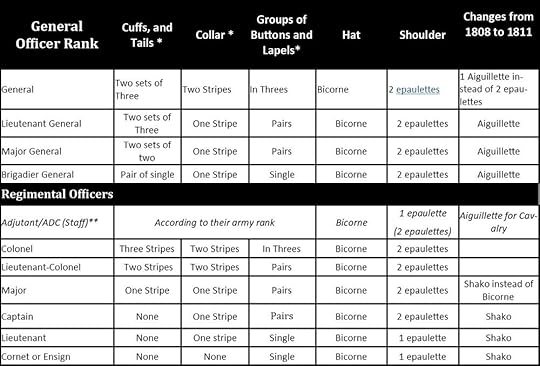

How were ranks displayed on British officers’ uniforms? Would you believe by the spacing of their coat buttons and lace?

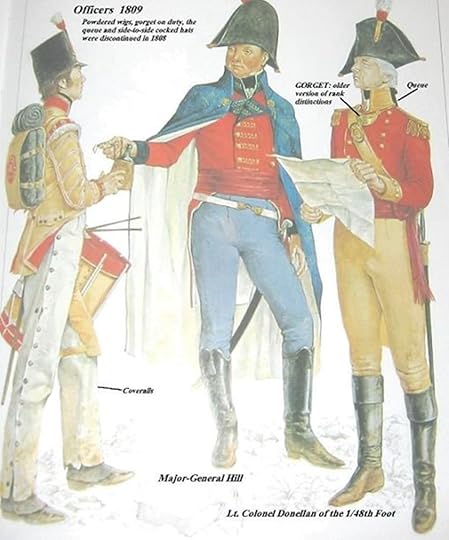

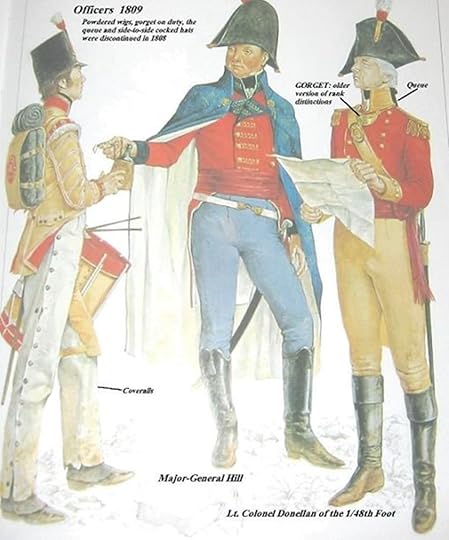

For officers, the signs of rank were evidenced on their coats. Look at the officers in the picture below to see if you can identify how their ranks are displayed without looking at the table farther down the page.

British militia had the same uniform and designations for rank. The difference between a Regular's uniform and a Militia man's was the absence of lace around the button holes on the front and sleeves of the coats. Militia uniforms were plain in comparison to the Regular officers.

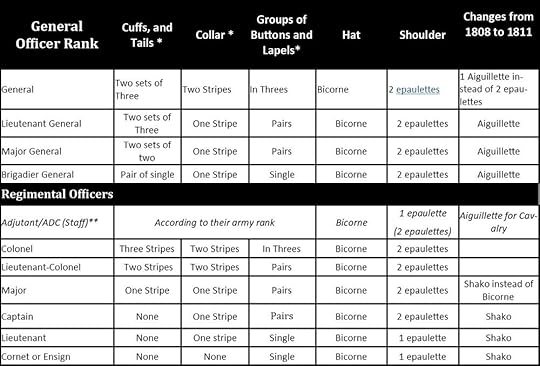

Here are the uniform regulations for British Officers for signifying their ranks from 1795 to 1815. All Infantry, artillery, engineers and general officers followed these conventions. Cavalry rank insignia tended to be more determined by the type of cavalry and each regiment’s uniform, thought the collar conventions generally were followed.

Notes:

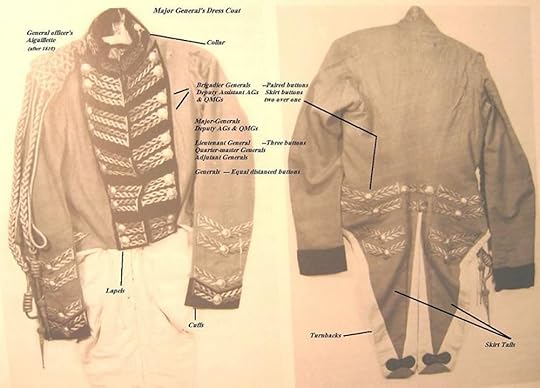

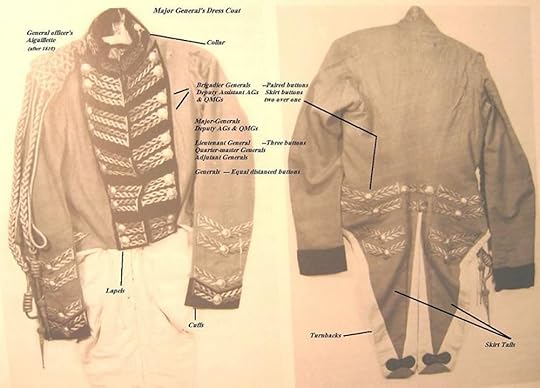

Notes:1. *The Stripes were chevrons of gold embroidery horizontally attached to cuffs, sleeves, collars, and tails. Each chevron had a button associated with it. On the lapels, the number of chevrons matched the number of buttons. [On the picture above, I’ve marked the parts of the uniform.] The plain or undress uniform coat did not display gold chevrons on the cuffs, as with General Hill shown above.

** General Staff- such as Quartermaster-General wore silver chevrons instead of gold on their coats, but their army rank was displayed. Quartermaster-General and Adjutant-General were staff positions, not ranks. George Murray was Wellington’s QG for most of the war and held the rank of Major General.

2. The Epaulettes of a colonel had a crown and star embroidered on the strap, the Lieutenant-Colonel a crown, and the Major a star. The same distinctions were observed by the field officers of the Light Dragoons.

3. A medal gorget was required around every officer’s neck, ensign to colonel. They were eliminated in 1808. The French Officers wore gorgets throughout the wars. They hated them.

4. The Bicorne was worn by regulation side-to-side (Napoleon style) until 1808 when it was decreed that it be worn fore-and-aft. (Wellington style) So, Colonel Donellan pictured above is wearing a pre-1808 uniform correctly. He was known for continuing to wear the gorget and powder his hair well into 1810.

5. The Aiguillette is the shoulder cording you see on the Major General’s coat seen above.

6. In actuality, you could see any combination of pre and post 1808 officer’s uniforms being worn through 1815.

7. The chevron embroidery was twice as wide for General officers. Each chevron, regardless of location, was supposed to have a button on the outside edge. The captain’s uniform was the only one where the match up between paired buttons and chevrons did not work. In that case the embroidery was placed between the two buttons. The two grades of officers where Regimental, up to colonel, and General, for Generals. This is what is meant by regimental officers or general officers.

8. There was an effort, though somewhat ineffectual, to associate a Regular Army regiment to a particular area or county--so the 15th Regiment was The 15th Shropshire. The idea was to have that county be the recruiting area for the regiment, but in practice it never really happened. A recruiting party paid no attention to such boundaries. However, part of the effort to connect the regiment to the county included the Militia regiment of the area sharing the same facing colors as the Regular regiment.

9. Field-Marshals could wear whatever they pleased, but officially, it would be red with dark blue facings, and lots and lots of gold braid and cording, particularly on the color and cuffs, so that the color blue could be hardly seen. Wellington tended to wear a blue overcoat on campaign.

Wellington uniformed as a field marshal. The blue sash is worn by the field marshal.

[I just saw the PBS Colin Firth version of Pride and Prejudice again, and at the end in the wedding, there is Darcy’s cousin in an accurate Lt. Colonel’s dress uniform]

See if you can identify the ranks of the following two regimental officers using the table of rank designations above:

1. 2.

2.

1. The officer is a full colonel, three buttons in a group on his coat and sleeves and two epaulettes.

2. The officer is a lieutenant, single buttons spacing, one chevon on the collar and one epaulette. The illustration is inaccurate because the lieutenant is wearing the bicorne fore and aft, but still wearing a gorget. Note that both officers have another emblem of rank for all regimental officers and NCOs, a red sash.

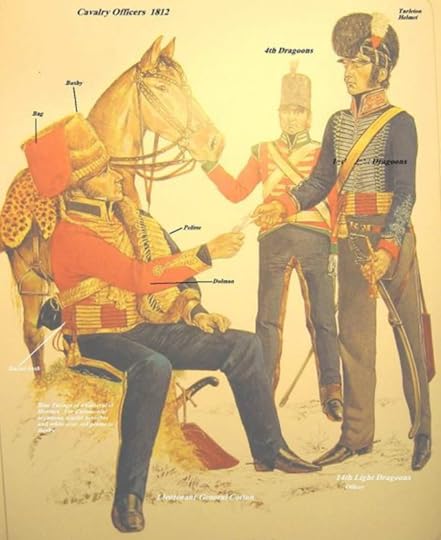

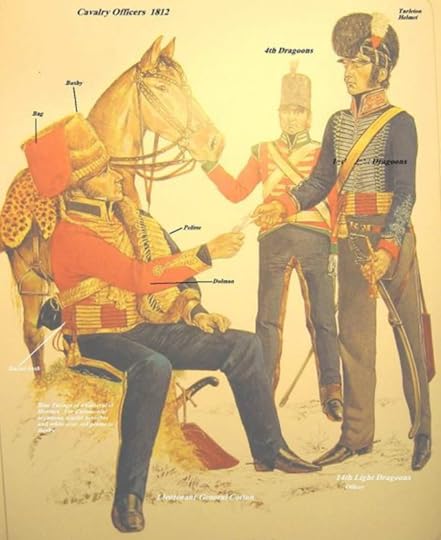

For the Cavalry, the rank distinctions followed the same patterns, but become more problematic. In general, the lace for officers was silver when the enlisted man’s uniform cording was white, and gold if the enlisted man’s cording was yellow. The number of layers of gold or silver embroidery and cording at the cuff and collar denoted the rank of the officer, ensigns with no collar cording, otherwise like the lieutenant’s single cord, captains two, majors three and so forth. For generals, they were supposed to wear staff uniforms following the infantry pattern, but each cavalry type, dragoon, hussar and Guard Dragoon and Household horse had a recognized “General officer’s Uniform” simply because even Generals liked dashing uniforms. Lord Uxbridge wore the officer’s uniform of the 7th Hussars at Waterloo. The picture above of General Cotton’s General of Hussars uniform he wore in the Peninsula. It is recognizable because of the dark blue cuffs and collar of a General—as there were no 'royal hussars' with dark blue facings. Of course, he was known for his extravagant outfits so there is a lot of fancy gold braiding.

Note in the picture above, the light dragoon trooper handing Cotton the note is an officer, having silver lace and cuff embroidery. As many officers were wealthy and all officers were responsible for supplying their own uniforms, there could be a lot of self expression among both infantry and cavalry officers, and little policing of the materials or final results was done as long as the rank and regiment colors were recognizable and the uniform not ‘too’ flamboyant. [i.e. looked so fancy as to rival the higher-ranked officers] Therefore, one could see a great deal of diversity around the edges of the printed regulations, particularly among the higher ranks. Here is the Captain Grose’s 1795 take on that issue in his popular humor book “Advice to Officers.” His advice is addressed ‘To Young Officers:’

“The first article we shall consider is your dress; a taste in which is the most distinguishing mark of military genius, and the principal characteristic of a good officer… The fashion of your clothes must depend on that ordered in the corps; that is to say, must be in direct opposition to it: for it would shew a deplorable poverty of genius, if you had not some ideas of your own in dress.”

Grose’s book remained in print well into the 1800s. Obviously, as the nineteenth century wore on, [pun intended] uniforms became, well, more uniform. The chevrons on some officers’ collars were transferred to the shoulder tabs. As the military took over responsibility for clothing officers, far less expensive, smaller metal badges replaced the heavily embroidered officer decorations. Today, only high-ranking generals and 20th century military dictators regularly wear any kind of embroidered gold, fancy belts and cuff decorations.

How Recognize A Napoleonic Officer's Rank

Recently, I was reading an enjoyable Regency romance when I came across this description:

“He was strikingly handsome in his red coat. She could see the officer was a captain by the bars on his shoulders.”

Well, that popped me right out of the scene. Captains in the Napoleonic British Army, the various militias or any other continental army of the time did not have their rank designated by two metal bars on their shoulder tabs. Those are modern American Officer designations shown below: [Today’s British Army have similar insignia for their shoulder tabs]

There were no such metal insignia for distinguishing officer ranks in the Napoleonic British army. So, I decided to describe how ranks were displayed by the British [and basically all Napoleonic armies to some extent]

How were ranks displayed on British officers’ uniforms? Would you believe by the spacing of their coat buttons and lace?

For officers, the signs of rank were evidenced on their coats. Look at the officers in the picture below to see if you can identify how their ranks are displayed without looking at the table farther down the page.

British militia had the same uniform and designations for rank. The difference between a Regular's uniform and a Militia man's was the absence of lace around the button holes on the front and sleeves of the coats. Militia uniforms were plain in comparison to the Regular officers.

Here are the uniform regulations for British Officers for signifying their ranks from 1795 to 1815. All Infantry, artillery, engineers and general officers followed these conventions. Cavalry rank insignia tended to be more determined by the type of cavalry and each regiment’s uniform, thought the collar conventions generally were followed.

Notes:

Notes:1. *The Stripes were chevrons of gold embroidery horizontally attached to cuffs, sleeves, collars, and tails. Each chevron had a button associated with it. On the lapels, the number of chevrons matched the number of buttons. [On the picture above, I’ve marked the parts of the uniform.] The plain or undress uniform coat did not display gold chevrons on the cuffs, as with General Hill shown above.

** General Staff- such as Quartermaster-General wore silver chevrons instead of gold on their coats, but their army rank was displayed. Quartermaster-General and Adjutant-General were staff positions, not ranks. George Murray was Wellington’s QG for most of the war and held the rank of Major General.

2. The Epaulettes of a colonel had a crown and star embroidered on the strap, the Lieutenant-Colonel a crown, and the Major a star. The same distinctions were observed by the field officers of the Light Dragoons.

3. A medal gorget was required around every officer’s neck, ensign to colonel. They were eliminated in 1808. The French Officers wore gorgets throughout the wars. They hated them.

4. The Bicorne was worn by regulation side-to-side (Napoleon style) until 1808 when it was decreed that it be worn fore-and-aft. (Wellington style) So, Colonel Donellan pictured above is wearing a pre-1808 uniform correctly. He was known for continuing to wear the gorget and powder his hair well into 1810.

5. The Aiguillette is the shoulder cording you see on the Major General’s coat seen above.

6. In actuality, you could see any combination of pre and post 1808 officer’s uniforms being worn through 1815.

7. The chevron embroidery was twice as wide for General officers. Each chevron, regardless of location, was supposed to have a button on the outside edge. The captain’s uniform was the only one where the match up between paired buttons and chevrons did not work. In that case the embroidery was placed between the two buttons. The two grades of officers where Regimental, up to colonel, and General, for Generals. This is what is meant by regimental officers or general officers.

8. There was an effort, though somewhat ineffectual, to associate a Regular Army regiment to a particular area or county--so the 15th Regiment was The 15th Shropshire. The idea was to have that county be the recruiting area for the regiment, but in practice it never really happened. A recruiting party paid no attention to such boundaries. However, part of the effort to connect the regiment to the county included the Militia regiment of the area sharing the same facing colors as the Regular regiment.

9. Field-Marshals could wear whatever they pleased, but officially, it would be red with dark blue facings, and lots and lots of gold braid and cording, particularly on the color and cuffs, so that the color blue could be hardly seen. Wellington tended to wear a blue overcoat on campaign.

Wellington uniformed as a field marshal. The blue sash is worn by the field marshal.

[I just saw the PBS Colin Firth version of Pride and Prejudice again, and at the end in the wedding, there is Darcy’s cousin in an accurate Lt. Colonel’s dress uniform]

See if you can identify the ranks of the following two regimental officers using the table of rank designations above:

1. 2.

2.

1. The officer is a full colonel, three buttons in a group on his coat and sleeves and two epaulettes.

2. The officer is a lieutenant, single buttons spacing, one chevon on the collar and one epaulette. The illustration is inaccurate because the lieutenant is wearing the bicorne fore and aft, but still wearing a gorget. Note that both officers have another emblem of rank for all regimental officers and NCOs, a red sash.

For the Cavalry, the rank distinctions followed the same patterns, but become more problematic. In general, the lace for officers was silver when the enlisted man’s uniform cording was white, and gold if the enlisted man’s cording was yellow. The number of layers of gold or silver embroidery and cording at the cuff and collar denoted the rank of the officer, ensigns with no collar cording, otherwise like the lieutenant’s single cord, captains two, majors three and so forth. For generals, they were supposed to wear staff uniforms following the infantry pattern, but each cavalry type, dragoon, hussar and Guard Dragoon and Household horse had a recognized “General officer’s Uniform” simply because even Generals liked dashing uniforms. Lord Uxbridge wore the officer’s uniform of the 7th Hussars at Waterloo. The picture above of General Cotton’s General of Hussars uniform he wore in the Peninsula. It is recognizable because of the dark blue cuffs and collar of a General—as there were no 'royal hussars' with dark blue facings. Of course, he was known for his extravagant outfits so there is a lot of fancy gold braiding.

Note in the picture above, the light dragoon trooper handing Cotton the note is an officer, having silver lace and cuff embroidery. As many officers were wealthy and all officers were responsible for supplying their own uniforms, there could be a lot of self expression among both infantry and cavalry officers, and little policing of the materials or final results was done as long as the rank and regiment colors were recognizable and the uniform not ‘too’ flamboyant. [i.e. looked so fancy as to rival the higher-ranked officers] Therefore, one could see a great deal of diversity around the edges of the printed regulations, particularly among the higher ranks. Here is the Captain Grose’s 1795 take on that issue in his popular humor book “Advice to Officers.” His advice is addressed ‘To Young Officers:’

“The first article we shall consider is your dress; a taste in which is the most distinguishing mark of military genius, and the principal characteristic of a good officer… The fashion of your clothes must depend on that ordered in the corps; that is to say, must be in direct opposition to it: for it would shew a deplorable poverty of genius, if you had not some ideas of your own in dress.”

Grose’s book remained in print well into the 1800s. Obviously, as the nineteenth century wore on, [pun intended] uniforms became, well, more uniform. The chevrons on some officers’ collars were transferred to the shoulder tabs. As the military took over responsibility for clothing officers, far less expensive, smaller metal badges replaced the heavily embroidered officer decorations. Today, only high-ranking generals and 20th century military dictators regularly wear any kind of embroidered gold, fancy belts and cuff decorations.

May 12, 2022

The Gentleman, Where Did That Idea Come From?

Way back when the Normans conquered Anglo-Saxon England in 1066, William the Conqueror installed a brand-new hierarchy of titles for the ruling class. These men and their families were given nearly all available land across England. Those who lived on those lands were ‘subjects’ of the ruling class and of the King.

At the same time, the Age of Chivalry was dawning. At its heart was a set of ethical behaviors and heroic ideals expected, specifically of the warriors, the knights of Feudal Europe—which included the majority of the nobility. Our notions of ‘fair play,’ gracious behaviors, and being thoughtful of others less fortunate were encapsulated in the ideals of Chivalry. Much of this code of conduct was created by the Catholic Church to curb the tyrannical and often rapacious behaviors of knights and nobles. Chivalry also included the romantic, almost exclusively the chaste worship of some lady, almost exclusively married.

A ‘gentleman’ originally meant someone at the lowest rung of the upper class, just below a squire. The Squire was the knight’s apprentice. The Gentleman was the ‘squire in waiting’, an officer among a knight’s soldier and servants. They shared the same expectations of chivalric behavior as any knight or noble. Heredity still held sway as the determiner of a gentleman. A man was born to the title, or like other noble ranks, he won glory for the king and as a reward, received a title and land.

The rank of gentleman became a distinct title with the Statute of Additions in 1413 and remained in place throughout the Regency. This title was given to a man of high rank or birth, with wealth and inherited land, though there were exceptions. In 1413, it was an inherited title. In the beginning, chivalric behavior was simply something expected of anyone holding the rank of gentleman or above. A man was born to be a gentleman. William Harrison, writing in the late 1500s, noted, "Gentlemen be those whom their race and blood, or at the least their virtues, [accomplishments in achieving glory] do make noble and known."

Even this early, a growing middle class sought entry into the upper classes with their new wealth. Not surprisingly, entry was at this lowest rung of nobility. In 1614, John Selden, author of Titles of Honor voiced a growing concern with wealth-created’ gentlemen:

"…that no Charter can make a Gentleman, which is cited as out of the mouth of some great Princes that have said it." He adds that "they without question understood Gentleman for Generous in the ancient sense, or as if it came from Genii/is in that sense, as Gentilis denotes one of a noble Family, or indeed for a Gentleman by birth." For "no creation could make a man of another blood more than he is."

The feudal creation of chivalric knighthood, of sensitive, ‘genteel’ behavior on the part of warriors grew to be seen as evidence of ‘good breeding’, a visible distinction setting the upper classes apart from the lower classes. In this case, ‘breeding’ meant just that: Family lineage. Not surprising, this set of behaviors had to be clearly defined. Henry Peacham’s 1634 treatise The Compete English Gentleman: The Truth in Our Times, was an example of an author delineating these differences to the upper class by one of their own. The prevailing belief was that gentlemen are born, not made.

The Successful Noble, the Successful Gentleman.

What constituted success and status for men of the European aristocracy from 1500s to 1800s was exemplified by the most successful noble in the middle of that period, Louis XIV, The Sun King. The goal of that French monarch was identical for every aristocrat: Glory. Or as the German princes called it ‘Ruhm.’ This was fame, admiration, and social distinction. These outward signs of glory were attained by successful wars and battlefield heroics, gaining new territories and particularly social notoriety among a noble’s peers. This was usually attained by a conspicuous demonstration of wealth, with clothing, court and social activities, impressive buildings and possessions.

Louis VIX was the model. It didn’t matter how small or poor theEuropean principality or duchy, a smaller version of the Versailles palace had to be built, wars fought and personal grandeur bought. The most expensive possessions and extravagant spending remained de rigor, driving many nobles—and their states—into poverty.

This desire for glory on the part of the British upper classes continued into the 19th Century. In 1812, Colonel George Napier, an officer and a gentleman, speaking of why he went to war wrote, “I should hate to fight out of personal malice or revenge, but have no objection to fighting for fun and glory.”

Social Challenges to the Upper Classes

The Enlightenment belief in the power of rational thought and Man’s ability to understand the world viewed the arbitrary laws and traditions such as hereditary power and ‘Divine Right of Kings’ [an the nobility] as hindrances to human progress in all areas of life.

In 1700, Louis XIV had said, “I am the State”. Fifty years later, a rational ‘Philosopher King’, Frederick the Great, as absolute a ruler as Louis, viewed himself as “The First Servant of the State.” Government has moved from the individual to an entity made up of every subject including the king: The State.

Chivalry, which had pertained only to knights and nobility grew to be a ‘rational’ expectation of any civilized person, first among the upper classes.

The political challenges went deeper. A contemporary of Frederick’s, Jean Jacque Rosseau, signed his letters and essays ‘A Citizen.’ He was not the subject of a king. He insisted on a different relationship with ‘the state.’ All men were equal as members of the ‘social contract.’ Those radical views of government and Man’s relationship to it led to both the American and French Revolutions. The Declaration of Independence in 1776 is based on this idea. This view saw representative government as the rational model, an idea encouraged in England by a history of civil wars, progressively limiting the power of the monarchy.

The British upper classes found themselves caught between the power gained through a weakened monarchy and the ideas of representative government, especially the madness of the French Revolution and Napoleon, threatening their hereditary powers.

The Gentleman Redefined

Ancient traditions of what constituted the gentry and a gentleman were challenged in the 18th Century by the Enlightenment ideas. Where the Enlightenment held up the intellect and reason as the salvation of man, not the class system. Romanticism challenged that view, turning to the emotions, the individual and the senses as more essential to life. During the Regency period, these two views marched side-by-side, when not mixing in complicated ways. The growth of the wealthy middle class and the reading public spread these views. For instance, British poets at the beginning of the 19th century seemed to exemplify this Enlightenment-Romanticism dichotomy. Coleridge, Wordsworth and Keats spoke to the intellectual approach to beauty, while Blake, Shelly and Byron were the sensual romantics, the arbitrators of ‘the New Man.’ This is a basic conflict in Austen’s book Sense and Sensibility: Elinor Dashwood holds on to propriety, sensible behavior in spite of her emotions whereas her sister Marianne values the purity of emotions honestly expressed above the artificial strictures of etiquette.’

Even politics were affected: the Tories held to traditional, rational beliefs, the Whigs, the liberal views of representative government, equality and romanticism. The expectations of gentlemanly behavior also became more democratic under these pressures, however at odds with upper class definitions.

Romanticism took the ideals of Chivalry and their attendant ethical behaviors and made them the ennobling aspect: Behavior defined the gentleman. Books and magazines concerning etiquette appeared detailing the proper behavior of gentlemen. Before the end of the 18th century, The Gentleman’s Magazine appeared. One of the first published to both ‘educate and inform’ the upper class gentleman—and the ambitious middle class of professionals and businessmen. Popular novels also detailed these expectations in an effort to ‘educate.’

The idea of ‘ennobling’ genteel behavior took hold in various ways. A story told at the end of the 18th century, which is probably not true, but indicative of this idea involved King James II. The monarch was petitioned by a lady asking him to make her son a gentleman. He supposedly replied, "I could make him a nobleman, but God Almighty could not make him a gentleman." The idea of a gentleman in behavior was beginning to be separated from any upper class distinction or rank.

When armies were commanded by nobles, every officer was of course, a ‘gentleman’, a member of the upper class, thus everyone commissioned was then both an “officer and a gentleman.” The upper classes enforced this distinction when all officer commissions were purchased for hundreds of pounds.

The huge expansion of the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars changed this relationship dramatically. There weren’t enough upper class gentlemen to officer the forces needed. This created a change in social relationships. For officers, regardless of military or social rank, in the regimental mess, all officers were considered equal. On the battlefield, all officers were equal, and middle class officers could outshine upper class officers, winning glory. For instance, volunteering for a ‘Forlorn Hope, leading infantry into a breach of a siege wall was one way of becoming ‘noticed’ and achieving higher rank and reputation.

However, because the common officer and soldier could now be or aspire to be a ‘gentleman,’ part of a superior social rank, there were jokes and jabs at crass men being capable of being a ‘gentleman’, particularly when displaying poor behavior. Here is one example of a song of the time about this dichotomy between behavior and being considered a ‘gentleman.’

The Gentleman Soldier

It's of a gentleman soldier

as sentry he did stand

He saluted a fair maiden

by a waiving of his hand

So then he boldly kissed her

and he passed it off as a joke

He drilled her up in the sentry box

wrapped up in a soldier's cloke [sic]

You can see all the lyrics at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=e34fG1DJQnI

Or the entire song sung by the Pogues

The social changes generated by the wars created real confusion socially.

In 1811, four men walk into a ballroom. One is a titled noble, one is a local squire, third is a wealthy businessman and the fourth, a lawyer. The host walks up to them and says, “Gentlemen, welcome to our ball.” Which men is he speaking to?

By the Regency, a man could be called a ‘gentleman’ for a variety of reasons including shear politness:

· A recognized rank by law and society as a land-owning member of the upper class.

· Any person of the upper class, noble or gentry, the recipient of heredity and tradition.

· A wealthy person of the upper class without land but with family among the gentry or nobility.

· A broad social class that included those who owned land (the country or landed gentry) as well as specific professions who did not (barristers, physicians, military officers and the clergy).

· A hereditary consequence of ‘good breeding.’

· Anyone adhering to a set of social and ethical principles, proper behavior and etiquette. This quality could possibly have any man being referred to as ‘a gentleman.’

· An address applied to any respectable man.

Any and all of the above might apply or not to the four men mentioned above. If that sounds confusing and rather contradictory, it was. “You misled me by the term gentleman,” observes one character in Persuasion, “I thought you were speaking of some man of property.” This confusion becomes a serious social conundrum for gentlemen of the Regency.

The Regency Upper Class: The realm of the Gentleman

By 1800, The British nobility or peerage included about 300 families of royal parentage as well as non-royal Dukes, Marquis, Earls, Viscounts, and Barons.

The Gentry was ranked lower, being all those who were not nobility, but still considered part of the upper class. This included all the offspring of a titled father except the first born son. However, the gentry also encompassed non-hereditary titles including 540 baronets, 350 knights, 6,000 landed squires and about 20,000 gentlemen.

The families of these nobles and gentry, considered the Beau Monde, totaled perhaps 1.5% of the British population in 1800 and about 20% of the national income. However, the nobility and gentry combined owned more than 70% of the land across the British Isles. Thus, in 1801, the gentleman was a member of an elite group numbering no more than 100,000 individuals in a nation of 8 million in England and Wales, nearly 16 million counting Scotland and Ireland.

Though industrialization and urbanization had begun to take hold at the end of the eighteenth century, the most influential sector of society during the Regency was the landed gentry through sheer numbers, and not the titled nobility. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this relatively small group retained their hold over the land through a system that encouraged the consolidation and extension of estates by enforcing strict inheritance laws, all property going to the eldest son. Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility were were written during this period of confusion and social transition where the effort to concentrate wealth and enlarge estates, all property was inherited by the first male children or male relatives rather than breaking it up and distributing it amongst family members, male and female.

This meant the other sons were left to fend for themselves, gentlemen without income, hard pressed to remain in that class by avoiding earning a living in ‘trade’. This too created a real conundrum for the upper-class, where a good portion of a family were hard pressed to remain part of the upper class. Rory Muir has written an excellent book on these ‘second sons’ and their options in gaining a livelihood, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune. https://www.amazon.com/Gentlemen-Uncertain-Fortune-Younger-Austens/dp/0300244312/ref=sr_1_1?crid=17BRR53SQB84Y&keywords=gentlemen+of+uncertain+fortune&qid=1652404720&sprefix=Gentlemen+of+uncer%2Caps%2C152&sr=8-1

The continental kingdoms such as France did not do this, which resulted in the nobility multiplying in number while diluting noble estates, later generations becoming impoverished princes and dukes with ever smaller holdings.

Officially, in order to be a member of the gentry, a man had to own a country house and estate lands which would be rented by tenant farmers or workers. A gentleman did not work his lands or *gasp* do manual labor like a small landowner, the yeoman farmer. His income came from the tenants. Any financial ties to business and ‘trade’ had to be severed to gain and retain gentry status.

The large country estates of the kind Mr. Darcy owned and Mr. Bingley desired to purchase, served as a symbol of the wealth and proof of being part of the landed gentry. The Gentry was a uniquely British stratum of upper-class society not found in continental Europe. Many of the Gentry were far wealthier than dukes and princes on the continent, or even in Britain.

Because of the many changes created by twenty years of war and the attendant economic wealth generated, becoming a gentleman grew easier, though buying an estate remained an expensive legal transaction. However, achieving the elevated position of gentleman, whether by wealth or accord, did not necessarily guarantee acceptance by the ranks of the upper class. There was a bottom tier where one was barely acknowledged regardless of wealth and land.

This the ability to hold onto the rank of gentleman became harder for a good portion of the male portion of the upper class while the ever-wealthier middle class was pushing into the upper class.

This inner-gentry ranking wasn’t enforced by law, per se, but rather by active social strictures. The Beau Monde policed its own. One had to be ‘allowed in’ socially, which was difficult without significant support. This kind of censorship could come from any quarter, but it always sounded the same. For example, Reverend William Holland, the vicar for the parish of Overstowey in Somerset, wrote in his diary in 1799 about a local man, Andrew Guy, “Alias squire Guy, a rich old widower…the son of a grazier [raised cattle] lifted up to the rank of gentleman, but ignorant and illiterate.” They would never be fully accepted, and the best hope was for their children to marry ‘above their station’, something that also could carry a stigma.

Jane Austen portrayed this social ‘gate’ repeatedly in her novels. A newly minted gentleman, someone like a wealthy merchant or even successful naval officers such as Admiral Croft and Captain Wentworth in Persuasion, did not have the prestige attached to ‘old families’ who inherited landed estates over several generations. The resistance to the ‘new gentry’ is portrayed by Jane Austen many times. For example, Anne Elliott’s family in the same novel is forced to rent their estate to the far wealthier Admiral Croft, but they still see him as a socially inferior interloper.

In Pride & Prejudice, Sir William Lucas is a knighted gentleman, but still deferential to the unknighted or titled Darcy because his family, far wealthier, comes from a long line of Darcy’s whereas Lucas has no inherited land or title. In Emma, the Vicar Philip Elton considers himself a gentleman and therefore capable of marrying Emma, while she, because of her sense of class distinctions, never imagines he would or could seriously consider courting her. It is no accident that Jane Austin gave Darcy [D’Arcy] and Lady de Bourgh ancient family names harking back to the French Normans.

Money and broadening definitions made this access to the upper class possible, but it also threatened the established class system, seriously weakening boundaries between the gentry and the middle classes. It made any such distinctions evermore critical, defending the class boundaries and a gentleman’s rank as an issue of social survival, particularly when facing the dictums of equality triumpted by the French Revolution. The Tories recognized this danger. Edmund Burke, is seen as the father of modern conservativism. In his 1791 “Reflections on the Revolution in France”, he wrote in detail about the need to uphold tradition, believing a nation’s wealth and stability resided in land ownership, the established hierocracy, not business and the fickle marketplace where land is sold and bought like cattle. It is no accident that some of his ideas are today championed by a group called “Chivalry Now.”

http://www.chivalrynow.net/articles2/...

Yet, Tom Paine responded with “The Rights of Man,” defending the new ideas of equality and representative government. Both Burke’s and Paine’s pamphlets were best sellers, even though they both were sold for three shillings apiece. Both pamphlets were supported by members of the upper class. The Tories felt the price would keep Paine’s work out of the hands of those who should not be reading it. However, the Whig ‘London Constitutional Society’ stepped in and provided Paine’s work for far less to the “lower orders.”

In Pride and Prejudice, we see the Lady Chatherine de Bourgh insist on this division in social rank when it appears that Darcy will propose to Elizabeth Bennett. Elizabeth refuses to acknowledge the importance of any such social distinction…or society’s condemnation, based on Darcy’s wealth and ancient status:

Elizabeth: “In marrying your nephew, I should not consider myself as quitting that sphere. He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman's daughter; so far we are equal.”'

Lady de Bourgh: “True. You are a gentleman's daughter. But who was your mother? Who are your uncles and aunts? Do not imagine me ignorant of their condition….”

Elizabeth: “If Mr. Darcy is neither by honour nor inclination confined to his cousin, why is not he to make another choice? And if I am that choice, why may not I accept him?”

Lady de Bourgh: “Because honour, decorum, prudence, nay, interest, forbid it. Yes, Miss Bennet, interest; for do not expect to be noticed by his family or friends, if you willfully act against the inclinations of all. You will be censured, slighted, and despised, by everyone connected with him. Your alliance will be a disgrace; your name will never even be mentioned by any of us.”

Elizabeth: “These are heavy misfortunes,” replied Elizabeth. “But the wife of Mr. Darcy must have such extraordinary sources of happiness necessarily attached to her situation, that she could, upon the whole, have no cause to repine.”

This debate and the social repercussions outlined by Lady B. were very real. The defense of class distinction and rank becomes more strident as its boundaries were battered from a number of quarters. Even so, the romantic view presented in Austen’s works were influential as were many others. Scott’s Waverly and Ivanhoe supported this romantic view of the heroic knight errant, the gentleman. Like Darcy, Ivanhoe’s actions, not his station, make him noble, a true gentleman.

Today, we view the Regency through a prism of more than two centuries. Our idea of Regency gentlemen can seem crystal clear, cut to shape by opinions of the intervening centuries. How to be a gentleman was not so obvious to those living during the Regency. It was a time of transition, where fundamental changes in perception can appear even across a single generation, which it did for the British gentleman.

Charles Dickens was an author of relatively humble origins who desired passionately to be recognized as a gentleman. Great Expectations, which contains a great deal of disguised self-analysis, is at once a portrait Dickens's concept of the Gentleman and a justification of his own claim to that title. His old friend, the author William Thackeray , on the other hand, insisted that a writer of novels could not be a gentleman. The two argued over this issue for a long time, Yet, owning land played no part in the debate. Thackeray’s novel, Vainity Fair presents his concept of the gentleman. The debate over just what constituted a gentleman raged on in many contexts, but nowhere was it contested so fiercely as within Victorian literature itself, appearing in works as different as Tennyson's In Memoriam.

By the 1860s, the notion of a gentleman had transformed to a significant degree from being a class of landowners to simply those following a set of ethical behaviors. Cardinal Newman, born in 1801 to a professional banking family, and not the gentry, wrote in the 1860s:

“It is almost a definition of a gentleman to say that he is one who never inflicts pain…he is mainly occupied in merely removing the obstacles which hinder the free and unembarrassed action of those about him… The true gentleman, in like manner carefully avoids whatever may cause a jar or jolt in the minds of those with whom he is cast—all clashing of opinion, or collision of feeling, all restraint, or suspicion, or gloom, or resentment; his great concern being to make everyone at his ease and at home.”

Gone are the requirements of wealth and land. During the Regency, men of the upper classes lived in the midst of this transition in definitions, from rank to ethics, from wealth and land, to particular behaviors. It represented an intense challenge to their identity. Upper class men were caught between maintaining one’s status in society against changing definitions and the upwardly mobile “new gentry,” while attempting to understand what expectations of behavior, old and new, constituted a proper gentleman.

The Darcy Dilemma

In this period of crisis, where the very structure of society is challenged and in transition across Europe, what does it mean to be a man? How is one to be a gentleman, upholding his proper station with all the contradictory expectations? This struggle is well illustrated again in Austen’s Pride and Prejudice: the pride of place and the effort to maintain class distinctions as opposed to the expectations—prejudices of ‘gentlemanly behavior.’

In Austen’s novel, Darcy has the problem of being a high ranking gentleman among gentlemen. How does one evidence that distinction in day-to-day interactions? In Austen’s novel, Darcy goes from being a gentleman aloof to those perceived as beneath him to working to meet Elizabeth’s expectations of a ‘true gentleman’ along the lines of the chivalric definition. His original proposal of marriage brilliantly illustrates Darcy’s, and all Regency Gentlemen’s conundrum:

“In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.”

Elizabeth’s astonishment was beyond expression. She stared, coloured, doubted, and was silent. This he considered sufficient encouragement, and the avowal of all that he felt and had long felt for her, immediately followed.

[Darcy]He spoke well, but there were feelings besides those of the heart to be detailed, and he was not more eloquent on the subject of tenderness than of pride. His sense of her inferiority—of its being a degradation—of the family obstacles which judgment had always opposed to inclination, were dwelt on with a warmth which seemed due to the consequence he was wounding, but was very unlikely to recommend his suit.

[Elizabeth replies] "In such cases as this, it is, I believe, the established mode to express a sense of obligation for the sentiments avowed, however unequally they may be returned. It is natural that obligation should be felt, and if I could feel gratitude, I would now thank you. But I cannot—I have never desired your good opinion, and you have certainly bestowed it most unwillingly. I am sorry to have occasioned pain to anyone. It has been most unconsciously done, however, and I hope will be of short duration. The feelings which, you tell me, have long prevented the acknowledgment of your regard, can have little difficulty in overcoming it after this explanation."

Mr. Darcy, who was leaning against the mantelpiece with his eyes fixed on her face, seemed to catch her words with no less resentment than surprise. His complexion became pale with anger, and the disturbance of his mind was visible in every feature. He was struggling for the appearance of composure, and would not open his lips till he believed himself to have attained it. The pause was to Elizabeth's feelings dreadful. At length, with a voice of forced calmness, he said:

"And this is all the reply which I am to have the honour of expecting! I might, perhaps, wish to be informed why, with so little endeavour at civility, I am thus rejected. But it is of small importance."

Darcy has no reason to suspect his proposal will be rejected. He offers Elizabeth not only position and wealth far beyond her current station, but a true, self-sacrificing love in his willingness to set aside her inferiority of position and family which will generate serious opposition from family, friends, and the upper class at large. Elizabeth rejects him because of his ‘ungentlemanly’ behavior towards her and others. She sees his efforts to maintain the social distinctions between her and her sister, his family and friend Bingley as insulting, thoughtless and hurtful, based on a false pride, false differences.

Austen portrays Darcy’s reaction as surprise and yes, resentment that she does not value his rank in society as he does. Darcy is left bewildered and angry by her rejection. A man’s identity as a gentleman and society’s expectations created conflicts where men struggled to find some balance. That is a primary issue for Austen’s novel.

Austin uses Bingley, newly established, to portray the other approach to this conflict. Bingley is recognized as very gentlemanly, very agreeable, treating every person, regardless of rank or station as equals…which leads him to favoring Jane, someone seen as socially inferior. Yet, he is unable to maintain those sentiments in the face of active opposition from his family and friends concerning the perceived inferiority of Jane Bennett and her family.

This concern for pride of place in society was taught by family and society. As Austen has Darcy explain:

“As a child I was taught what was right, but I was not taught to correct my temper. I was given good principles, but left to follow them in pride and conceit. Unfortunately, an only son (for many years an only child), I was spoilt by my parents, who, though good themselves (my father, particularly, all that was benevolent and amiable), allowed, encouraged, almost taught me to be selfish and overbearing; to care for none beyond my own family circle; to think meanly of all the rest of the world; to wish at least to think meanly of their sense and worth compared with my own. [i.e. in maintaining his social status] Such I was, from eight to eight and twenty; and such I might still have been but for you, dearest, loveliest Elizabeth!”

The rules of rank, gentlemanly behavior and etiquette are the cause of misunderstandings and conflicts throughout Jane Austen’s novels as they were for most English novels of the period. However, from reading her novels, I think Austen illustrated a deeper, more realistic understanding of the emotional dissidence among the Regency upper class than many contemporary authors. In the end, Austin seems to condemn both the pride of station and wealth as well as the prejudice of judging a person on notions of ‘propriety,’ while upholding those gentlemanly, chivalric behaviors, whether Darcy or Captain Wentworth.

I found a college thesis by Sarah Ailwood entitled “What men ought to be”: Masculinities in Jane Austen’s Novels to be a fascinating investigation into Austen’s view of men, not only how they were, but her ideas concerning the resolution of these conflicting views of a ‘gentleman. It can be found at:

This confusing tug-of-war over a gentleman’s identity was as emotionally real for men of the Regency as any of today’s seemingly incompatible social expectations. As a comparison, today women attempt to meet Society’s expectations and their own, to ‘have it all’, be both a mother and a career woman. Such dilemmas can surface at any time. Recently, on “The Voice” just the mention of the struggle to have a family and career by a contestant brought tears to the eyes of several women.

February 22, 2022

Men Writing Romance?

Do men write romance novels? Do men read them?

When I was preparing to have my first romance novel published, several writer colleagues and my publisher suggested that I have a woman’s pen name or at least something androgynous. I was told more than eighty percent of romance readers are women, and many won’t read male romance authors. Having been a member of several romance writers’ groups for more than two decades, I have been told a few times, “I’d never read a romance written by a man,” but overwhelmingly, I have received wonderful support from women writers.