Michael Marshall's Blog

January 16, 2025

I helped edit a report on using AI to help tackle antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of those nasty looming threats on the horizon that it's difficult to even think about, especially given how many other problems we have as a species. In the most extreme scenarios, we end up back where we were in the 1800s, where a simple bacterial infection could kill you.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of those nasty looming threats on the horizon that it's difficult to even think about, especially given how many other problems we have as a species. In the most extreme scenarios, we end up back where we were in the 1800s, where a simple bacterial infection could kill you.Over the last few weeks, I've been helping to edit a report that looks at how we could use artificial intelligence (AI) to tackle AMR. The report is a joint effort by Google DeepMind and the Fleming Initiative and is out today. It's free to read:

Harnessing Artificial Intelligence to Tackle Antimicrobial Resistance

There's also a press release on the Fleming Initiative website, which summarises the key points.

The report starts with the need to figure out which aspects of AMR are most "learnable" by AIs. From there, it proceeds through the need for much more data and for that data to be widely shared. I also want to highlight the importance of equity: the AIs need to be accessible to low- and middle-income countries, as they're the ones at most risk from AMR.

I don't know how much of this will come to pass, but I hope it does: it's in problems like AMR, where there's a huge amount of complex data to sift through, that AI can be genuinely useful.

Published on January 16, 2025 09:07

January 3, 2025

Belatedly, my favourite stories of 2024

So 2024 is over and wasn't it... er... 366 days of stuff happening.

So 2024 is over and wasn't it... er... 366 days of stuff happening.As is tradition, here are my 12 favourite stories I've written over the year. These are the ones I'm most proud of, for whatever reason. Happy reading!

Game-changing archaeology from the past 5 years - and what's to come

Leading archaeologists share the biggest recent advances in our understanding of human evolution, and their hopes for the exciting finds the next five years may have in store

Readers deserve better from popular science books

There is a dirty secret in publishing: most popular science books aren't fact-checked. This needs to change

Iceberg A-68: The story of how a mega-berg transformed the ocean

The world's largest icebergs – which can be larger than entire countries in some cases – break off the Antarctic ice sheet. As they drift and melt in the Southern Ocean, they create a unique environment around them.

Geology's biggest mystery: When did plate tectonics start to reshape Earth?

Researchers have spent decades hunting for clues about the origins of the process that moves the continents around. Its deep history is finally starting to come into focus.

Why fantasy has often handled environmentalism better than science fiction

Science fiction struggles to portray environmental concerns; fantasy brings them to life (originally published in Arc 10 years ago, republished on my blog in 2024 so it counts)

The truth about social media and screen time's impact on young peopleThere are many scary claims about excess time on digital devices for children and teenagers. Here’s a guide to the real risks - and what to do about them

The UK coal-fired power station that became a giant battery

The closure of the last coal-fired power station in the UK raises questions about how old fossil fuel infrastructure can be repurposed. One option is to use them to store energy from renewables.

The unexpected reasons why human childhood is extraordinarily long

Why childhood is so protracted has long been mysterious, now a spate of archaeological discoveries suggest an intriguing explanation

The Earth's deepest living organisms may hold clues to alien life on Mars

To understand the life that might survive deep below Mars' surface, we can look to some of the deepest, and oldest, forms of living organism on our own planet.

First Nations astronomers predicted eclipses without using writing

The oldest written records of eclipses are in cuneiform texts from around 2000 BC, but examination of oral traditions reveal First Nations astronomers were predicting eclipses by word of mouth

How CRISPR could yield the next blockbuster crop

Scientists are attempting to rapidly domesticate wild plant species by editing specific genes, but they face major technical challenges — and concerns about exploitation of Indigenous knowledge.

And last but most definitely not least:

Our human ancestors often ate each other, and for surprising reasons

Fossil evidence shows that humans have been practising cannibalism for a million years. Now, archaeologists are discovering that some of the time they did it to honour their dead

Published on January 03, 2025 05:53

January 2, 2025

My favourite books of 2024

I read 30 books in 2024 - a bit shy of my target of 35, but I don't take those targets seriously so who cares.

I read 30 books in 2024 - a bit shy of my target of 35, but I don't take those targets seriously so who cares.You can see an overview of my year in books on GoodReads and on StoryGraph (login required).

Here are my five favourites and why:

Saga, Compendium One

Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples

I realise I'm late to this party but Saga is astonishing: a gripping, funny and touching multi-stranded epic about space travel, oppression, sex, robots and parenting. All human life is here, and quite a lot of non-human life as well.

The Republic of Thieves

Scott Lynch

The third and so far latest in the Gentlemen Bastard series - think Ocean's Eleven in a fantasy world inspired by Renaissance Venice - this was packed with cunning plot twists while also telling a compelling love story.

The BBC: A century on air

David Hendy

A rich, informative, funny and surprising history of the BBC - which doubles as an argument for why we in the UK need to take care of the BBC in the face of endless right-wing attempts to destroy it.

The Girl in the Road

Monica Byrne

Back in 2021 I gave a rave review to Monica Byrne's second novel The Actual Star: the word "masterpiece" was used and I don't say that lightly. In 2024 I finally read her debut, about a young woman fleeing across a narrow artificial trail that spans the Indian Ocean. It's hallucinatory, immersive, deeply unsettling and wildly imaginative. It won't be for everyone - but it's a hell of a ride.

Fool's Errand

Robin Hobb

Another piece of work that I'm late to, this first volume of The Tawny Man trilogy starts with 100 pages of gentle character work before building to a nail-biter of a climax. I can't discuss the reason for the sobbing without spoilers, but everyone who has read the book knows exactly which episode wrecked me.

Published on January 02, 2025 16:00

October 13, 2024

A correction to a story, and some thoughts on corrections

One of the worst experiences in any halfway-conscientious journalist's life is when someone tells you you've made a mistake. This just happened to me, so I thought I'd describe what happened and what my editors and I did about it. This also seems a good place to spell out something about corrections: it's not a novel insight by any means, but I think it's a useful one.

One of the worst experiences in any halfway-conscientious journalist's life is when someone tells you you've made a mistake. This just happened to me, so I thought I'd describe what happened and what my editors and I did about it. This also seems a good place to spell out something about corrections: it's not a novel insight by any means, but I think it's a useful one.In September I wrote a feature for BBC Future about an emerging trend of old fossil fuel power plants being turned into battery storage sites. Here it is (no paywall):

The UK coal-fired power station that became a giant battery

The story is built around a case study of a site in Ferrybridge, UK. It also highlights some other examples from around the world, and digs into some numbers to estimate how much more battery storage the UK will need if it's to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 while ensuring a reliable supply of electricity.

After the story was published, two readers flagged an apparent mistake on social media. On Threads, @sambeaujones posted:

"Dear BBC (and Michael Marshall @michaelmarshall6504), GW is not a measurement of battery storage capacity - GWh is. GW is a measurement of generation capacity. Yours, Grumpy."

And on Twitter/X, @CHPopp wrote:

"Great News from UK. BESS [battery energy storage systems] will become an important feature for renewable energy. One question: why is capacity denominated in GW and not in GWh?"

Oh no, I thought. While I've been writing about environmental and sustainability issues for years, my background is in biology and very much not in electrical engineering. I know that the units and terminology around electricity are quite specific and can be confusing. Had I mangled things? The two readers were making different points, but both revolved around the use of GW (gigawatts) as a unit of electrical capacity.

First, a basic point about these abbreviations. W is short for "watts" and Wh is short for "watthours". The G in front is for "giga", which means we are talking 10 to the power of 9, or a billion. So a gigawatt is a billion watts. Elsewhere in the story I talked about MW, megawatts, which means 10 to the power of 6, or a million watts. The thing that was at issue was the W bit.

The figures that were being questioned came straight from primary sources. SSE, the company building the Ferrybridge battery site, talks about capacity in MW: see for yourself. The National Grid report I had cited for projections of future BESS needs also talked about capacity in GW: again, scroll to page 119 and see for yourself. The numbers were correct. Maybe I was using these units wrong in some way, but if I was, it seemed, so were an energy company and the National Grid.

Still, I consulted the editors at BBC Future, and emailed Grazia Todeschini; an electrical engineer at King's College London whom I had interviewed for the story. She told me that, to properly describe a battery, you need two numbers: one expressed in W and one in Wh. Strictly, the W is "power" and the Wh is "capacity".

In other words, the numbers I had used were all correct, but I had used the wrong word to describe them. While the figure in W is indeed a description of "how much electricity this thing can store", it isn't technically the "capacity".

The thing is, the word "capacity" is often used loosely. The National Grid report I had relied on did so, as did many energy company websites. In fact, while this was going on, the International Energy Agency released a big report called Renewables 2024 . In the executive summary, the very first graph shows growth in "renewable capacity", measured in GW. The IEA is about as authoritative as it gets on energy supply.

Armed with new knowledge, I went back to the editors, and in the spirit of dotting Is and crossing Ts they decided to remove some of the uses of the word "capacity". For various reasons they couldn't remove them all: for instance, some are in direct quotes from interviewees, which can't be edited.

This is what a fact-checking process looks like. I went back to my documentary sources, and explicitly asked an expert in the field if I had done anything wrong. And then the editors tweaked the article accordingly.

I want to end by saying something about the importance of corrections. Mistakes are inevitable in any body of work, so despite my instinctual panic there's no shame in it. The important thing is to be open-minded when someone calls you out for a slip, to tell the editors immediately, to investigate, and ultimately to be willing to make a change.

I'm also a believer in openness. Apart from ensuring accuracy, I think it builds trust. A lot of ink has been spilled, rightly, about newspapers burying corrections deep in the inside pages, where hardly anyone will see them. It seems to me this is fine if it was something minor, like a spelling mistake or a slightly wrong date for a historical event. However, it becomes wildly problematic if the correction is an admission that an entire story was nonsense, especially if the story in question was promoted on the front page or otherwise a big deal. If your publication made a dramatic claim, and it was wrong, you need to correct it prominently. There is a sliding scale of mistakes, ranging from missing a full stop at the end of a paragraph (annoying but ultimately harmless) to falsely accusing someone of murder (very harmful). To my mind, the prominence of corrections needs to reflect the severity of the mistake.

Where does my "capacity" mistake fall on this spectrum? I think it isn't a big deal, for two reasons.

First, if the way I used "capacity" is a mistake, then a lot of people in the energy industry are making the same mistake. As I've documented, pretty much every source I looked at used "capacity" in the same way as me. I think it was pretty reasonable for me, as a journalist, to copy the National Grid's word choices.

Second, nobody reading the story would come away with the wrong impression. Again: all the figures are correct, as is the picture they paint of what the energy system looks like now and how it needs to change to achieve net-zero. And far from my word choice misleading readers, the lay understanding of "capacity" is "how much can this thing store", which is the right idea.

In short, this is the sort of correction that publications should absolutely make, and BBC Future did. But it's a minor one.

Published on October 13, 2024 16:00

October 9, 2024

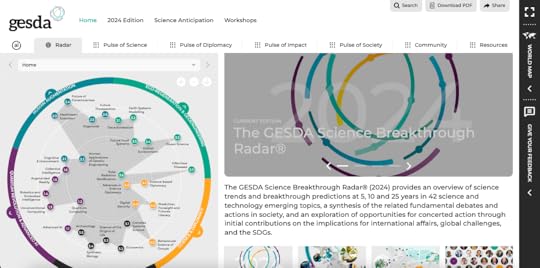

My contributions to the 2024 GESDA Breakthrough Radar

I helped to write the 2024 GESDA Breakthrough Radar. What is the GESDA Breakthrough Radar, I hear you ask? It's a roundup of the most exciting scientific and technological fields, from artificial intelligence to synthetic biology. Crucially, it offers predictions for what these fields will throw up in the next 5, 10 and 25 years, based on workshops with leading researchers.

I helped to write the 2024 GESDA Breakthrough Radar. What is the GESDA Breakthrough Radar, I hear you ask? It's a roundup of the most exciting scientific and technological fields, from artificial intelligence to synthetic biology. Crucially, it offers predictions for what these fields will throw up in the next 5, 10 and 25 years, based on workshops with leading researchers.The Radar is produced by the Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator (GESDA), a think tank affiliated with the Swiss government. The idea is to provide policymakers and diplomats with a rough roadmap of coming scientific discoveries, so they can make policy to handle them. That means anything from how to regulate synthetic biology to how to drive decarbonisation.

I want to emphasise that I am one of many writers and editors who contributed to the report. This was very much a team effort.

With that in mind, here, in alphabetical order, are the topics that I covered. Some of these were written in previous years and lightly updated for 2024. Others are entirely new. All of this is completely free to read, and it's designed to be very accessible (policymakers and diplomats not necessarily having much background in science). So if you're interested in what the next 25 years might look like, do have a read.

ArchaeologyDecarbonisationEarth systems modellingFuture food systemsInfectious diseasesOcean scienceScience of the origins of life (I mean, I did previously write a book on this...)Shaping ecosystems: Anticipating an age of eco-augmentation (this one was particularly good fun because I went to a three-day conference about it in the Swiss Alps, which is a very nice way to spend three days and I recommend it very much)Solar radiation modificationSynthetic biology

Published on October 09, 2024 16:00

September 10, 2024

Why fantasy has often handled environmentalism better than science fiction

This essay was published in Arc, a sadly short-lived spin-off from New Scientist, in 2014. Arc was a wild blend of short stories, essays, criticism and general interestingness, created and edited by Simon Ings. You can buy back issues on Zinio, if you want to see it in its full glory.

In this essay, I tried to articulate why it is that so many of my deeper feelings about nature and the environment are rooted in fantasy literature, not in science fiction - even though you might think SF was the genre more suited to dealing with such "realistic" topics.

There are bits of it I would write differently now, so in a few places I've inserted notes in square brackets. Also, things have changed in the last decade: subgenres like cli-fi and solarpunk were less prominent in 2014. So in some ways the argument might be out of date. But on the other hand, I was mostly writing about the prominent "entry texts" in the genres, as those are both the most widely known and responsible for setting the tone. You can judge for yourself whether there's still anything worthwhile here, 10 years on. The Hobbiton set in New Zealand (Credit: Joe Ross, CC-by-SA-2.0) The nature of the catastrophe

The Hobbiton set in New Zealand (Credit: Joe Ross, CC-by-SA-2.0) The nature of the catastrophe

Science fiction struggles to portray environmental concerns; fantasy brings them to life. Michael Marshall wonders why talking trees speak more eloquently than hard facts

Everyone knows the environment is in trouble. The climate is changing, species are going extinct, and vulnerable people are paying the price. It’s part of our narrative as a society: we are screwing up the planet, and we need to stop before we screw ourselves.

You wouldn’t know any of this from science fiction. SF has, with a few exceptions, ignored climate change and the ways in which a rich biosphere helps to sustain our society. The exceptions (we’ll get to them) do portray environmentalism extremely well, but they are not entry texts: new readers must work their way through the genre before they reach them.

Environmentalism and science fiction both have their roots in the nineteenth century [Dear Past Mike, this sentence needs a qualifier. People have been worrying about the environment for millennia, and the roots of SF run extremely deep.]. The period that saw the publication of science fiction’s formative texts, Frankenstein and The War of the Worlds, also saw William Blake coin the phrase “dark Satanic mills” in reference to the hideous pollution created by the Industrial Revolution. Later, the British physicist John Tyndall produced the first real evidence of the greenhouse effect, demonstrating via ingenious experiments that gases like water vapour and carbon dioxide trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere. [ Eunice Foote ]

Science fiction exploded onto the popular consciousness in the middle of the twentieth century, driven first by pulp magazines and later by B-movies. By then some scientists were already concerned about climate change, warning that if humanity kept emitting carbon dioxide by burning fossil fuels, Earth might become dangerously hot. Concerns loomed large about the destruction of wilderness, the extinction of species and pollution. The milestone came in 1962, with the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a grim but lyrical warning about the reckless use of pesticides on farms.

These were some of the most important scientific discoveries of the twentieth century. Science fiction ignored them. The great early authors like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were largely concerned with space travel, artificial intelligence and other forms of computer technology, and with what a future society might look like. Asimov’s Foundation series, published in the 1950s, is a long disquisition on how to run a society so that it survives in the long term, but environmental degradation, one of the principal threats that can collapse a society, doesn’t feature.

[If I were to write this now, I would tweak that last sentence to make clear that climate change can act as a stressor on societies, but how that society (especially its elite) chooses to respond is a huge factor in whether or not a collapse (whatever that means) happens.]

In the decade after Silent Spring, Clarke produced two important works - 2001: A Space Odyssey and Rendezvous with Rama – and Heinlein published The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. All are classics, asking huge questions about our place in the universe and how a space-based society might work; but it’s fair to say that Silent Spring might as well not have been written. In fact Heinlein’s book expressed a libertarian philosophy, preaching extreme individual freedom and an extremely reduced state. Many other technofuturist authors pushed similar philosophies, until the courageous individual struggling against the cruel, repressive state became a recurring theme in the genre. In fiction, as in the real world, libertarianism tends to ignore environmental concerns – or denies their validity – because they pose an insoluble problem for anyone trying to design a libertarian utopia. It’s hard to imagine how to halt society’s emissions of greenhouse gases if you don’t even admit the existence of society.

One exceptional science fiction author did tackle the environment. The result, Frank Herbert’s Dune, is (for my money) the best science fiction novel ever written. It contains plentiful genre tropes, from faster-than-light travel to advanced weapons technology. But its breakthrough was to create an entire planetary ecology and then show how people lived within it.

The desert world of Arrakis has almost no water, so the native Fremen have been forced to adopt extreme methods of water conservation. They wear “stillsuits” that prevent them losing moisture to the air and even have a taboo against crying. In later novels, the Fremen gather enough water to change the planet’s climate, and Arrakis experiences rain for the first time. But this comes at a high price: the rain is lethal to the giant sandworms, which produce the lucrative spice that underpins the economy. So, in a bid to improve their environment, the people of Arrakis damage it and threaten their own livelihoods.

In the wake of Dune, science fiction had a decade of strong interest in the environment. In 1966, Harry Harrison’s Make Room! Make Room! delivered a stern warning of the dangers of overpopulation, portraying a nightmarish future New York City that is overcrowded and chronically short of food. [Your regularly scheduled note that fears about overpopulation are at best wildly overblown and often extremely misguided.] Its film adaptation Soylent Green, together with Silent Running, in which a botanist fights to preserve some of the last living plants in an artificial orbiting habitat, contributed to a short wave of environmentalist-themed SF at the movies. But this burst of interest wouldn’t last.

Instead the 1980s saw the rise of cyberpunk and a revival of space opera. Cyberpunk often took environmental destruction as read and made it part of the background: the future world of William Gibson’s Neuromancer has clearly taken a beating. It’s equally obvious that this wasn’t a book about the environment.

Iain Banks exploded onto the SF stage in the 1980s with his Culture novels. Set in an ultra-technological communist utopia, the books were unusually thoughtful space operas that asked tough moral questions, often about whether advanced societies have the right to interfere with the more primitive. The series helped establish a template for many later authors like Alastair Reynolds and Charles Stross. Strangely, though, for a writer so vocally “green” in interviews and in his personal life, Banks rarely worked environmental questions into his fiction.

The one genre that has really aced environmentalism is the one that has, on the face of it, the least to do with harsh reality. From The Lord of the Rings to Game of Thrones, fantasy has conveyed the threat of environmental destruction in a way SF never has.

Tolkien himself denied that his tale of hobbits and their quest to destroy the One Ring was about anything in particular. In his foreword to the book he said that, while it was enriched by his experiences and ideas, he didn’t like to write allegories, and preferred “history, true or feigned”. So one shouldn’t take The Lord of the Rings as an environmentalist tract, any more than it is an allegory for the second world war. But it does contain a wealth of key environmentalist ideas, and even foreshadows some modern debates.

Most obviously, the book portrays a clash between heavy industry and the desire to preserve nature. Sauron’s forces pollute their home, leaving it a barren wasteland. One character states that Sauron “can torture and destroy the very hills”, and the Dark Lord’s stronghold of Mordor is a vivid portrayal of a collapsed, polluted ecosystem. The subplot about the wizard Saruman, who cuts down a forest to build facilities for his army, and his defeat by the talking trees known as Ents, develops this theme. The Ents’ final decision, to recolonise the area razed by Saruman, is a textbook example of rewilding, in which a landscape altered by humans is restored to a wild state by reintroducing long-lost plants and animals. We can be confident Tolkien intended this fanciful-sounding interpretation: in his foreword he complains, “The country in which I lived in childhood was being shabbily destroyed before I was ten”.

But there is more: the people of Middle Earth have to find ways to coexist with nature, just as we do. Today, most countries measure their success in terms of Gross Domestic Product: how much money they have made. But there is a growing push towards new measures that focus on the wellbeing of people and the environment. There is no point having lots of money if everyone is miserable and hungry. Tolkien understood this: in the book’s penultimate chapter, Saruman takes over the hobbits’ homeland, the Shire, and converts it from a bucolic paradise to a ravaged industrial backlot. He does this largely out of spite, and indeed there’s no benefit to anyone: as one hobbit notes, the villains install a new mechanised mill to increase efficiency, but there is no point as the old mill was quite fast enough to grind enough corn for everyone. The Shire has made technological and economic progress, but all this does is foul the environment, and make its inhabitants less happy.

With all these proto-environmentalist themes in The Lord of the Rings, it’s no wonder it was taken up by the burgeoning hippy movement in the 1960s – to Tolkien’s acute embarrassment. (The San Francisco free-love scene was hardly his intended audience.) But it’s striking, the extent to which these themes recur in other fantasy classics of the twentieth century.

Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy was published in the late 60s and early 70s. Written for older children, it follows a wizard named Ged from his initial training to his time as chief wizard, when he must defend the Earthsea archipelago from a seemingly world-ending evil.

As in many of her books, Le Guin uses Taoist ideas about how to live one’s life, with a strong focus on letting things be and refraining from action unless it is absolutely necessary. This is spelled out early in the first book, A Wizard of Earthsea, when Ged is apprenticed to a wizard named Ogion and finds that his tutor hardly ever does magic. This frustrates Ged, “for when it rained Ogion would not even say the spell that every weatherworker knows, to send the storm aside.” Clouds are comically shoved from side to side by neighbouring wizards, none of whom want to get wet. “But Ogion let the rain fall where it would,” and simply takes shelter, reluctant to change the path of the storm in case he inadvertently causes something far more serious. Nowadays we know that human interference in the climate can create more extreme storms, yet we keep pressing planet Earth’s buttons willy-nilly. Ogion seems wiser than ever.

Restoring the balance of nature is something the genre returns to just as often as it returns to magic swords and dragons. Fantasy authors obsess over the notion of evil as a pollutant. Hating everything that is beautiful, the villainous Lord Foul of Stephen Donaldson’s ten-book Thomas Covenant series, begun in the late 1970s, creates monsters and spews toxins into The Land. [Yes, I know these books are hugely problematic for (among other things) their portrayal of rape, not to mention Donaldson's, er, overcooked prose style.]

In the second Covenant trilogy, Lord Foul deploys a piece of black magic known as the Sunbane, a malevolent aura that surrounds the Sun and causes paroxysmic environmental changes. In rapid succession, The Land suffers drought, fertility, pestilence and rain, the changes coming too swiftly and violently for many of its inhabitants to adapt. Anyone wanting to get a sense of what it would be like to live in a world suffering rapid climate change should go read The Wounded Land. It is far from literally correct, but it is incomparably vivid.

Today’s most successful fantasy series is George R R Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, adapted for television as Game of Thrones. [Obviously, I wrote this before season eight came out] The series is known for its rich political intrigue and “realistic” approach to its pseudo-medieval setting. But it’s telling that even in this tale of warring kings, the biggest threat is environmental. In the world of Westeros, seasons last for years, and the story plays out in the run-up to a brutal winter in which the snows are expected to fall hundreds of feet thick, causing everyone to freeze to death. That’s if the ice zombies that only come out in winter don’t get them first (and of course assuming that Martin ever gets around to finishing the thing). In Martin’s world, political leaders squabble endlessly over power and money while in the background a changing climate threatens to kill everyone. Sound familiar?

There are other elements in fantasy that are innately environmentalist. The use of anthropomorphic nature is one: Tolkien’s personified trees, with their comical slow speech, no doubt help many young readers to love woodland. They certainly had that effect on me. The use of talking animals, whether it’s Le Guin’s aloof dragons or the talking rabbits in Watership Down, also ensures that the reader starts to care about nature, almost without realising it. This is most effective when the anthropomorphised organisms are still recognisably themselves: Tolkien’s Ents are extremely tree-ish in their behaviour and manner, for all that they can talk and walk; it’s an easy leap from liking Ents to liking real trees.

Many fantasies hark back to a distant past when their world was dominated by other creatures, before the advent of humans. Many of the trees in A Song of Ice and Fire’s Westeros are carved with faces, which relate in some nebulous way to old gods that have long since disappeared with the rise of human society. Humans in fantasy are often interlopers in a wondrous landscape, who don’t know what they’re doing and may unwittingly harm their world. Concepts like stewardship, and responsibility for nature, emerge naturally from this.

Fantasy succeeds by expressing these elemental truths about humanity’s relationship with nature, rather than through realistic depictions of genuine environmental problems. After all, metaphor is often more vivid than straight exposition, however beautifully delivered. That’s why the Ents’ assault on Isengard can still move me to joyful tears, over two decades after I first read it. I know that trees can’t literally do that, but it’s an exaggerated version of something I would dearly like to see happen: for Earth’s wild areas to retake some of the land that humanity has sprawled onto and despoiled.

Can science fiction offer any competition to these vivid images? James Cameron’s Avatar – at time of writing still the most financially successful film in history – did try. Avatar is a straightforward environmentalist parable, in which human miners dig for a rare mineral in the pristine forest of an alien world, while eco-conscious natives fight back. [Hmm, not sure about "natives": it has a colonialist ring. "Indigenous peoples" would be better]

The film certainly took environmentalism to a mass audience, and the astoundingly detailed ecosystem of Pandora makes for a vivid experience. The trouble is, the film articulates an out-of-date “hair-shirt” version of environmentalism. The only way to live in harmony with the Pandoran ecosystem, it seems, is to abandon advanced technology and return to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Really? It wasn’t possible to mine for the mineral in a slightly more sensitive way, without blowing up the natives’ home tree? Avatar suggests that any damage to the ecosystem, even the smallest interference, is a bad thing, and that modern technology and the environment cannot coexist. If Cameron really believes that, he should refrain from making big-budget movies. At any rate, much of the environmentalist movement has moved on from this sort of thinking. You can now find greens like Mark Lynas arguing furiously in favour of nuclear power, because it produces lots of energy without releasing greenhouse gases. Avatar, for all its visual brilliance, was obsolete even when it came out.

In the book world, there is a movement (or at least, a number of authors who critics have lumped together and called a movement) called biopunk, with a strong environmental emphasis. The most successful example is Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl, set in a Bangkok where sea levels have risen and genetically-modified organisms run wild. Bacigalupi shows how environmental change has affected society – but it’s a grim book, and long, not for science-fiction newbies.

SF’s environmentalist figurehead is Kim Stanley Robinson. His Mars trilogy is one of the pinnacles of modern science fiction, and its story of ecologists terraforming Mars should be read by everyone with an interest in the environment (which is to say, everyone). Robinson tackles everything from man’s relationship with nature to environmental economics, and does it all with élan. ["man's relationship", ugh] More recently, his less-successful Science in the Capital series is about US government scientists trying to stop climate change. [Robinson has since published Aurora and The Ministry for the Future, both of which tackle environmental issues.]

Robinson is going to go down as one of science fiction’s greats, but he is not a gateway author. Only a fraction of fans will get past the allure of full-on space opera and find their way to someone like Kim Stanley Robinson. By contrast, most people’s introduction to adult fantasy is likely to be either The Lord of the Rings or – nowadays – A Song of Ice and Fire, and the environmentalist themes are in place from the start. The beginner texts may not receive the same critical attention as more sophisticated works, but they are more influential; these are the stories people read while they’re young.

Does SF have an inherent disadvantage when it comes to portraying environmentalism? Maybe, but there are a few things its practitioners might bear in mind. First, any novel that’s set anything more than a few decades into the future has to include the effects of climate change. It’s ridiculous not to. You can make all the cute predictions about artificial intelligence you like: if you set your story in 2100 and don’t at least give lip-service to extreme weather and an ice-free Arctic, your imagined future will be irrelevant. It would be like a science fiction writer of the early twentieth century deciding, without explanation, to imagine a futuristic society without computers or space travel.

Some of the techniques of fantasy aren’t really available to science fiction authors. It’s hard within science fiction to personify nature (although Avatar did give it a shot). SF authors, being oh-so-rational, wouldn’t dream of anthropomorphising a tree – and then they have the devil’s own job making the trees matter. Shorn of the ability to walk and talk, greenery’s a poor protagonist. [I didn't anticipate Adrian Tchaikovsky's Children of Time series, which among other things personifies slime moulds.]

But perhaps SF authors could trust the real science a bit more. Most ecologists, for instance, don’t talk much about the beauty of wilderness, but about “ecosystem services”: the things that ecosystems like forests do for us that we don’t appreciate until they’re gone. For instance, forests clean dirt out of the rivers that flow through them, ensuring that people living downstream have access to clean water. When you take that into account, preserving the forest stops being about having a nice place to go for a walk, and becomes a health issue. Frank Herbert used this idea in Dune half a century ago, but it hasn’t had much play since.

One big thing science fiction could do is ditch the libertarian fringe. SF has done so little on the environment because the genre can’t bear to let go of its libertarian ideals. It’s easier to transfer those ideals into outer space (where resources seem effectively limitless) than face up to the realities of life on the ground. From Heinlein on, the genre has pushed an extreme freedom ethic that rejects any notion that society has the right to curtail an individual’s actions, particularly if those actions are part of a free market.

This is an easy place to write from, but it’s a calamitous philosophy to live by. We often hear complaints that SF has lost its can-do optimism. Well, is it any wonder? In the hard, chromed, rugged, affectless shambles SF has made of the world, the introduction of some shamanic wonder - or failing that, a little love of place and people - would go a very long way.

In this essay, I tried to articulate why it is that so many of my deeper feelings about nature and the environment are rooted in fantasy literature, not in science fiction - even though you might think SF was the genre more suited to dealing with such "realistic" topics.

There are bits of it I would write differently now, so in a few places I've inserted notes in square brackets. Also, things have changed in the last decade: subgenres like cli-fi and solarpunk were less prominent in 2014. So in some ways the argument might be out of date. But on the other hand, I was mostly writing about the prominent "entry texts" in the genres, as those are both the most widely known and responsible for setting the tone. You can judge for yourself whether there's still anything worthwhile here, 10 years on.

The Hobbiton set in New Zealand (Credit: Joe Ross, CC-by-SA-2.0) The nature of the catastrophe

The Hobbiton set in New Zealand (Credit: Joe Ross, CC-by-SA-2.0) The nature of the catastropheScience fiction struggles to portray environmental concerns; fantasy brings them to life. Michael Marshall wonders why talking trees speak more eloquently than hard facts

Everyone knows the environment is in trouble. The climate is changing, species are going extinct, and vulnerable people are paying the price. It’s part of our narrative as a society: we are screwing up the planet, and we need to stop before we screw ourselves.

You wouldn’t know any of this from science fiction. SF has, with a few exceptions, ignored climate change and the ways in which a rich biosphere helps to sustain our society. The exceptions (we’ll get to them) do portray environmentalism extremely well, but they are not entry texts: new readers must work their way through the genre before they reach them.

Environmentalism and science fiction both have their roots in the nineteenth century [Dear Past Mike, this sentence needs a qualifier. People have been worrying about the environment for millennia, and the roots of SF run extremely deep.]. The period that saw the publication of science fiction’s formative texts, Frankenstein and The War of the Worlds, also saw William Blake coin the phrase “dark Satanic mills” in reference to the hideous pollution created by the Industrial Revolution. Later, the British physicist John Tyndall produced the first real evidence of the greenhouse effect, demonstrating via ingenious experiments that gases like water vapour and carbon dioxide trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere. [ Eunice Foote ]

Science fiction exploded onto the popular consciousness in the middle of the twentieth century, driven first by pulp magazines and later by B-movies. By then some scientists were already concerned about climate change, warning that if humanity kept emitting carbon dioxide by burning fossil fuels, Earth might become dangerously hot. Concerns loomed large about the destruction of wilderness, the extinction of species and pollution. The milestone came in 1962, with the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a grim but lyrical warning about the reckless use of pesticides on farms.

These were some of the most important scientific discoveries of the twentieth century. Science fiction ignored them. The great early authors like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were largely concerned with space travel, artificial intelligence and other forms of computer technology, and with what a future society might look like. Asimov’s Foundation series, published in the 1950s, is a long disquisition on how to run a society so that it survives in the long term, but environmental degradation, one of the principal threats that can collapse a society, doesn’t feature.

[If I were to write this now, I would tweak that last sentence to make clear that climate change can act as a stressor on societies, but how that society (especially its elite) chooses to respond is a huge factor in whether or not a collapse (whatever that means) happens.]

In the decade after Silent Spring, Clarke produced two important works - 2001: A Space Odyssey and Rendezvous with Rama – and Heinlein published The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. All are classics, asking huge questions about our place in the universe and how a space-based society might work; but it’s fair to say that Silent Spring might as well not have been written. In fact Heinlein’s book expressed a libertarian philosophy, preaching extreme individual freedom and an extremely reduced state. Many other technofuturist authors pushed similar philosophies, until the courageous individual struggling against the cruel, repressive state became a recurring theme in the genre. In fiction, as in the real world, libertarianism tends to ignore environmental concerns – or denies their validity – because they pose an insoluble problem for anyone trying to design a libertarian utopia. It’s hard to imagine how to halt society’s emissions of greenhouse gases if you don’t even admit the existence of society.

One exceptional science fiction author did tackle the environment. The result, Frank Herbert’s Dune, is (for my money) the best science fiction novel ever written. It contains plentiful genre tropes, from faster-than-light travel to advanced weapons technology. But its breakthrough was to create an entire planetary ecology and then show how people lived within it.

The desert world of Arrakis has almost no water, so the native Fremen have been forced to adopt extreme methods of water conservation. They wear “stillsuits” that prevent them losing moisture to the air and even have a taboo against crying. In later novels, the Fremen gather enough water to change the planet’s climate, and Arrakis experiences rain for the first time. But this comes at a high price: the rain is lethal to the giant sandworms, which produce the lucrative spice that underpins the economy. So, in a bid to improve their environment, the people of Arrakis damage it and threaten their own livelihoods.

In the wake of Dune, science fiction had a decade of strong interest in the environment. In 1966, Harry Harrison’s Make Room! Make Room! delivered a stern warning of the dangers of overpopulation, portraying a nightmarish future New York City that is overcrowded and chronically short of food. [Your regularly scheduled note that fears about overpopulation are at best wildly overblown and often extremely misguided.] Its film adaptation Soylent Green, together with Silent Running, in which a botanist fights to preserve some of the last living plants in an artificial orbiting habitat, contributed to a short wave of environmentalist-themed SF at the movies. But this burst of interest wouldn’t last.

Instead the 1980s saw the rise of cyberpunk and a revival of space opera. Cyberpunk often took environmental destruction as read and made it part of the background: the future world of William Gibson’s Neuromancer has clearly taken a beating. It’s equally obvious that this wasn’t a book about the environment.

Iain Banks exploded onto the SF stage in the 1980s with his Culture novels. Set in an ultra-technological communist utopia, the books were unusually thoughtful space operas that asked tough moral questions, often about whether advanced societies have the right to interfere with the more primitive. The series helped establish a template for many later authors like Alastair Reynolds and Charles Stross. Strangely, though, for a writer so vocally “green” in interviews and in his personal life, Banks rarely worked environmental questions into his fiction.

The one genre that has really aced environmentalism is the one that has, on the face of it, the least to do with harsh reality. From The Lord of the Rings to Game of Thrones, fantasy has conveyed the threat of environmental destruction in a way SF never has.

Tolkien himself denied that his tale of hobbits and their quest to destroy the One Ring was about anything in particular. In his foreword to the book he said that, while it was enriched by his experiences and ideas, he didn’t like to write allegories, and preferred “history, true or feigned”. So one shouldn’t take The Lord of the Rings as an environmentalist tract, any more than it is an allegory for the second world war. But it does contain a wealth of key environmentalist ideas, and even foreshadows some modern debates.

Most obviously, the book portrays a clash between heavy industry and the desire to preserve nature. Sauron’s forces pollute their home, leaving it a barren wasteland. One character states that Sauron “can torture and destroy the very hills”, and the Dark Lord’s stronghold of Mordor is a vivid portrayal of a collapsed, polluted ecosystem. The subplot about the wizard Saruman, who cuts down a forest to build facilities for his army, and his defeat by the talking trees known as Ents, develops this theme. The Ents’ final decision, to recolonise the area razed by Saruman, is a textbook example of rewilding, in which a landscape altered by humans is restored to a wild state by reintroducing long-lost plants and animals. We can be confident Tolkien intended this fanciful-sounding interpretation: in his foreword he complains, “The country in which I lived in childhood was being shabbily destroyed before I was ten”.

But there is more: the people of Middle Earth have to find ways to coexist with nature, just as we do. Today, most countries measure their success in terms of Gross Domestic Product: how much money they have made. But there is a growing push towards new measures that focus on the wellbeing of people and the environment. There is no point having lots of money if everyone is miserable and hungry. Tolkien understood this: in the book’s penultimate chapter, Saruman takes over the hobbits’ homeland, the Shire, and converts it from a bucolic paradise to a ravaged industrial backlot. He does this largely out of spite, and indeed there’s no benefit to anyone: as one hobbit notes, the villains install a new mechanised mill to increase efficiency, but there is no point as the old mill was quite fast enough to grind enough corn for everyone. The Shire has made technological and economic progress, but all this does is foul the environment, and make its inhabitants less happy.

With all these proto-environmentalist themes in The Lord of the Rings, it’s no wonder it was taken up by the burgeoning hippy movement in the 1960s – to Tolkien’s acute embarrassment. (The San Francisco free-love scene was hardly his intended audience.) But it’s striking, the extent to which these themes recur in other fantasy classics of the twentieth century.

Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy was published in the late 60s and early 70s. Written for older children, it follows a wizard named Ged from his initial training to his time as chief wizard, when he must defend the Earthsea archipelago from a seemingly world-ending evil.

As in many of her books, Le Guin uses Taoist ideas about how to live one’s life, with a strong focus on letting things be and refraining from action unless it is absolutely necessary. This is spelled out early in the first book, A Wizard of Earthsea, when Ged is apprenticed to a wizard named Ogion and finds that his tutor hardly ever does magic. This frustrates Ged, “for when it rained Ogion would not even say the spell that every weatherworker knows, to send the storm aside.” Clouds are comically shoved from side to side by neighbouring wizards, none of whom want to get wet. “But Ogion let the rain fall where it would,” and simply takes shelter, reluctant to change the path of the storm in case he inadvertently causes something far more serious. Nowadays we know that human interference in the climate can create more extreme storms, yet we keep pressing planet Earth’s buttons willy-nilly. Ogion seems wiser than ever.

Restoring the balance of nature is something the genre returns to just as often as it returns to magic swords and dragons. Fantasy authors obsess over the notion of evil as a pollutant. Hating everything that is beautiful, the villainous Lord Foul of Stephen Donaldson’s ten-book Thomas Covenant series, begun in the late 1970s, creates monsters and spews toxins into The Land. [Yes, I know these books are hugely problematic for (among other things) their portrayal of rape, not to mention Donaldson's, er, overcooked prose style.]

In the second Covenant trilogy, Lord Foul deploys a piece of black magic known as the Sunbane, a malevolent aura that surrounds the Sun and causes paroxysmic environmental changes. In rapid succession, The Land suffers drought, fertility, pestilence and rain, the changes coming too swiftly and violently for many of its inhabitants to adapt. Anyone wanting to get a sense of what it would be like to live in a world suffering rapid climate change should go read The Wounded Land. It is far from literally correct, but it is incomparably vivid.

Today’s most successful fantasy series is George R R Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, adapted for television as Game of Thrones. [Obviously, I wrote this before season eight came out] The series is known for its rich political intrigue and “realistic” approach to its pseudo-medieval setting. But it’s telling that even in this tale of warring kings, the biggest threat is environmental. In the world of Westeros, seasons last for years, and the story plays out in the run-up to a brutal winter in which the snows are expected to fall hundreds of feet thick, causing everyone to freeze to death. That’s if the ice zombies that only come out in winter don’t get them first (and of course assuming that Martin ever gets around to finishing the thing). In Martin’s world, political leaders squabble endlessly over power and money while in the background a changing climate threatens to kill everyone. Sound familiar?

There are other elements in fantasy that are innately environmentalist. The use of anthropomorphic nature is one: Tolkien’s personified trees, with their comical slow speech, no doubt help many young readers to love woodland. They certainly had that effect on me. The use of talking animals, whether it’s Le Guin’s aloof dragons or the talking rabbits in Watership Down, also ensures that the reader starts to care about nature, almost without realising it. This is most effective when the anthropomorphised organisms are still recognisably themselves: Tolkien’s Ents are extremely tree-ish in their behaviour and manner, for all that they can talk and walk; it’s an easy leap from liking Ents to liking real trees.

Many fantasies hark back to a distant past when their world was dominated by other creatures, before the advent of humans. Many of the trees in A Song of Ice and Fire’s Westeros are carved with faces, which relate in some nebulous way to old gods that have long since disappeared with the rise of human society. Humans in fantasy are often interlopers in a wondrous landscape, who don’t know what they’re doing and may unwittingly harm their world. Concepts like stewardship, and responsibility for nature, emerge naturally from this.

Fantasy succeeds by expressing these elemental truths about humanity’s relationship with nature, rather than through realistic depictions of genuine environmental problems. After all, metaphor is often more vivid than straight exposition, however beautifully delivered. That’s why the Ents’ assault on Isengard can still move me to joyful tears, over two decades after I first read it. I know that trees can’t literally do that, but it’s an exaggerated version of something I would dearly like to see happen: for Earth’s wild areas to retake some of the land that humanity has sprawled onto and despoiled.

Can science fiction offer any competition to these vivid images? James Cameron’s Avatar – at time of writing still the most financially successful film in history – did try. Avatar is a straightforward environmentalist parable, in which human miners dig for a rare mineral in the pristine forest of an alien world, while eco-conscious natives fight back. [Hmm, not sure about "natives": it has a colonialist ring. "Indigenous peoples" would be better]

The film certainly took environmentalism to a mass audience, and the astoundingly detailed ecosystem of Pandora makes for a vivid experience. The trouble is, the film articulates an out-of-date “hair-shirt” version of environmentalism. The only way to live in harmony with the Pandoran ecosystem, it seems, is to abandon advanced technology and return to the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Really? It wasn’t possible to mine for the mineral in a slightly more sensitive way, without blowing up the natives’ home tree? Avatar suggests that any damage to the ecosystem, even the smallest interference, is a bad thing, and that modern technology and the environment cannot coexist. If Cameron really believes that, he should refrain from making big-budget movies. At any rate, much of the environmentalist movement has moved on from this sort of thinking. You can now find greens like Mark Lynas arguing furiously in favour of nuclear power, because it produces lots of energy without releasing greenhouse gases. Avatar, for all its visual brilliance, was obsolete even when it came out.

In the book world, there is a movement (or at least, a number of authors who critics have lumped together and called a movement) called biopunk, with a strong environmental emphasis. The most successful example is Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl, set in a Bangkok where sea levels have risen and genetically-modified organisms run wild. Bacigalupi shows how environmental change has affected society – but it’s a grim book, and long, not for science-fiction newbies.

SF’s environmentalist figurehead is Kim Stanley Robinson. His Mars trilogy is one of the pinnacles of modern science fiction, and its story of ecologists terraforming Mars should be read by everyone with an interest in the environment (which is to say, everyone). Robinson tackles everything from man’s relationship with nature to environmental economics, and does it all with élan. ["man's relationship", ugh] More recently, his less-successful Science in the Capital series is about US government scientists trying to stop climate change. [Robinson has since published Aurora and The Ministry for the Future, both of which tackle environmental issues.]

Robinson is going to go down as one of science fiction’s greats, but he is not a gateway author. Only a fraction of fans will get past the allure of full-on space opera and find their way to someone like Kim Stanley Robinson. By contrast, most people’s introduction to adult fantasy is likely to be either The Lord of the Rings or – nowadays – A Song of Ice and Fire, and the environmentalist themes are in place from the start. The beginner texts may not receive the same critical attention as more sophisticated works, but they are more influential; these are the stories people read while they’re young.

Does SF have an inherent disadvantage when it comes to portraying environmentalism? Maybe, but there are a few things its practitioners might bear in mind. First, any novel that’s set anything more than a few decades into the future has to include the effects of climate change. It’s ridiculous not to. You can make all the cute predictions about artificial intelligence you like: if you set your story in 2100 and don’t at least give lip-service to extreme weather and an ice-free Arctic, your imagined future will be irrelevant. It would be like a science fiction writer of the early twentieth century deciding, without explanation, to imagine a futuristic society without computers or space travel.

Some of the techniques of fantasy aren’t really available to science fiction authors. It’s hard within science fiction to personify nature (although Avatar did give it a shot). SF authors, being oh-so-rational, wouldn’t dream of anthropomorphising a tree – and then they have the devil’s own job making the trees matter. Shorn of the ability to walk and talk, greenery’s a poor protagonist. [I didn't anticipate Adrian Tchaikovsky's Children of Time series, which among other things personifies slime moulds.]

But perhaps SF authors could trust the real science a bit more. Most ecologists, for instance, don’t talk much about the beauty of wilderness, but about “ecosystem services”: the things that ecosystems like forests do for us that we don’t appreciate until they’re gone. For instance, forests clean dirt out of the rivers that flow through them, ensuring that people living downstream have access to clean water. When you take that into account, preserving the forest stops being about having a nice place to go for a walk, and becomes a health issue. Frank Herbert used this idea in Dune half a century ago, but it hasn’t had much play since.

One big thing science fiction could do is ditch the libertarian fringe. SF has done so little on the environment because the genre can’t bear to let go of its libertarian ideals. It’s easier to transfer those ideals into outer space (where resources seem effectively limitless) than face up to the realities of life on the ground. From Heinlein on, the genre has pushed an extreme freedom ethic that rejects any notion that society has the right to curtail an individual’s actions, particularly if those actions are part of a free market.

This is an easy place to write from, but it’s a calamitous philosophy to live by. We often hear complaints that SF has lost its can-do optimism. Well, is it any wonder? In the hard, chromed, rugged, affectless shambles SF has made of the world, the introduction of some shamanic wonder - or failing that, a little love of place and people - would go a very long way.

Published on September 10, 2024 06:06

September 8, 2024

How I came to write a feature in Nature about the origins of plate tectonics

Recently I a feature out in Nature, about how plate tectonics got started on Earth. It's free to read:

Recently I a feature out in Nature, about how plate tectonics got started on Earth. It's free to read:Geology's biggest mystery: When did plate tectonics start to reshape Earth?

I want to say a little about how this story originated, for two reasons. First, I thought it might be useful to any aspiring or junior journalists to get a sense of how someone like me (who has been around the block a few times) comes up with ideas. This is one case where it was solely my idea and I can tell you exactly what happened. And second, I can give a little bit of personal context that wasn't appropriate for a reported story.

What happened was this. I have a longstanding interest in palaeontology and the history of the Earth, which of course relates to my fascination with the origin of life - about which I wrote a book called The Genesis Quest that you should all go and read. This includes an interest in what the planet was like when it was young, e.g. when did the crust solidify, when did oceans form. The onset of plate tectonics is a big part of that story.

For years I've seen (and written!) stories that try to pin down when plate tectonics got started. Depending on the type of data they were collecting and the processes they were trying to study, people came up with wildly differing timings - sometimes billions of years apart. So the debate became a matter of "my data's better than your data", or perhaps "my data's more relevant than your data".

In 2022, I wrote a feature for New Scientist about the early geological history of the Earth. This was mostly focused on the early oceans, in particular on the vexed question of when the first exposed land emerged, and what that meant for the origin of life. Here it is (paywalled):

What Earth's mysterious infancy tells us about the origins of life

The story included a short box about the origins of plate tectonics, based largely on a conversation with geologist Nadja Drabon. Her evidence pointed to a multi-part story, in which there were early episodes of subduction that were localised and short-lived, and which gradually built into global plate tectonics. In other words, there was no single switch-on date: it was a process. I wrote this up in about 200 words, and spent most of my time on the oceans question.

Once that feature was done, the idea of a multi-stage onset of plate tectonics lodged itself in my head and wouldn't leave. If this was correct, then all those stories I had read (and written!) pinpointing the origin of plate tectonics were in some crucial sense wrong. Not that the data was wrong, or that the dates identified weren't significant. But the stories were conceptually wrong because they were chasing a single onset date, when that just wasn't what happened.

Naturally, actual geologists were way ahead of me. When I started looking, I found reviews making exactly this kind of argument. It seemed to me that there was a quiet paradigm shift happening in geology: the idea of a single onset of plate tectonics had proved unworkable, so everyone was instead devising multi-step scenarios. And that's the story I pitched to Rich Monastersky at Nature, and which is now published.

It was a challenging story to report, because two contradictory things happened. Some of the geologists I spoke to were, I think, slightly baffled that I was doing it, because what I was saying seemed obvious to them. Meanwhile, the editors at Nature (rightly!) took a certain amount of convincing, because this shift in consensus had happened gradually and there wasn't a clear peg: no single dramatic study that had overturned the previous paradigm. It had crept up on everyone, including me.

I don't know how much cut-through the story will have, but here's the dream. You should never again see a story that is framed around "we found the date when plate tectonics started". The geological community is forming a consensus that there is no such single date. It was a multi-step process. Put another way, the point of the story isn't to say "this is exactly how it happened", but rather "this is the kind of story we need to be telling".

This is, of course, also implicitly about churnalism. If you're a journalist who is constantly writing rapid-turnaround stories with little or no time for reflection or deep reading, you won't be able to grasp slow but crucial trends like this. I'm privileged to be able to do this sort of thing, because the outlets I write for are willing to give me the time and money it takes. Many other journalists aren't so lucky.

Published on September 08, 2024 16:00

August 7, 2023

Where to find me on social media

What with all the brouhaha around X (formerly Twitter) and the launch of competing sites like Mastodon and Threads, I thought it might be useful to quickly spell out where you can find me on social media and what I'm doing there.

For now at least, I'm keeping my profile on Twitter. I'm less active and chatty on there than I used to be, but I'm present. I've thought about deleting my account, but for now I'm keeping it, for two reasons. One, I have a lot of followers there (and the number has held up despite Elon Musk's activities). And second, if I delete my account it just opens up the space for potential impersonators. But if you've left, that's fine: I'm on plenty of other sites.

For a full listing of where to find me, have a look on the About page. If you scroll down a bit, you'll see a grid of logos: these are all the websites where I have a public profile.

With a few exceptions, I post the same things to every social media site I'm on. If you follow me on Instagram, you're pretty much getting the same stuff you'd get on Facebook or LinkedIn. I'm on these sites to raise my own profile and to draw people's attention to my work, so my aim is for them to be pretty consistent in the messages they present. Or to put it another way, I want to meet and engage with readers wherever you are. If you prefer Threads to Mastodon, that's fine: I'm on both. I tweak the posts according to the rules and conventions of each site, but fundamentally I'm posting because I want you to read a story I've written about a gigantic extinct shark, or I really liked a book and want to tell the world about it, or whatever.

Because I have so many accounts, I use a piece of software to manage them. It's called Loomly and it allows me to quickly post the same (or basically the same) thing to multiple sites. It's great, I love it.

The problem I currently have is that Loomly doesn't connect to the newer social media platforms. Mastodon, Threads and Newsmast are not supported, and if I were on BlueSky or Post they wouldn't be either. This means the time I saved by adopting Loomly is now being sucked up by copying posts to these other sites.

All of which is another way of saying: I really want Loomly to roll out integration for these newer sites ASAP. Otherwise I'll either need to find a different social media manager, or ditch some of the accounts.

I don't want to do either of those things. In particular I don't want to abandon my accounts on nascent networks like Mastodon, because the audiences on these sites may well grow. In an ideal world I'd also make some short videos for TikTok and YouTube. But right now managing my existing social media is a time-consuming slog.

And yes I do blame Elon Musk for this.

For now at least, I'm keeping my profile on Twitter. I'm less active and chatty on there than I used to be, but I'm present. I've thought about deleting my account, but for now I'm keeping it, for two reasons. One, I have a lot of followers there (and the number has held up despite Elon Musk's activities). And second, if I delete my account it just opens up the space for potential impersonators. But if you've left, that's fine: I'm on plenty of other sites.

For a full listing of where to find me, have a look on the About page. If you scroll down a bit, you'll see a grid of logos: these are all the websites where I have a public profile.

With a few exceptions, I post the same things to every social media site I'm on. If you follow me on Instagram, you're pretty much getting the same stuff you'd get on Facebook or LinkedIn. I'm on these sites to raise my own profile and to draw people's attention to my work, so my aim is for them to be pretty consistent in the messages they present. Or to put it another way, I want to meet and engage with readers wherever you are. If you prefer Threads to Mastodon, that's fine: I'm on both. I tweak the posts according to the rules and conventions of each site, but fundamentally I'm posting because I want you to read a story I've written about a gigantic extinct shark, or I really liked a book and want to tell the world about it, or whatever.

Because I have so many accounts, I use a piece of software to manage them. It's called Loomly and it allows me to quickly post the same (or basically the same) thing to multiple sites. It's great, I love it.

The problem I currently have is that Loomly doesn't connect to the newer social media platforms. Mastodon, Threads and Newsmast are not supported, and if I were on BlueSky or Post they wouldn't be either. This means the time I saved by adopting Loomly is now being sucked up by copying posts to these other sites.

All of which is another way of saying: I really want Loomly to roll out integration for these newer sites ASAP. Otherwise I'll either need to find a different social media manager, or ditch some of the accounts.

I don't want to do either of those things. In particular I don't want to abandon my accounts on nascent networks like Mastodon, because the audiences on these sites may well grow. In an ideal world I'd also make some short videos for TikTok and YouTube. But right now managing my existing social media is a time-consuming slog.

And yes I do blame Elon Musk for this.

Published on August 07, 2023 05:49

June 30, 2023

I wrote a special issue called "The Civilisation Myth" for New Scientist

After over 15 years as a journalist, I still get a thrill whenever one of my stories is the cover feature. This one for New Scientist is particularly special because it's a special issue: one big main feature and two shorter tie-ins, plus an editorial.

After over 15 years as a journalist, I still get a thrill whenever one of my stories is the cover feature. This one for New Scientist is particularly special because it's a special issue: one big main feature and two shorter tie-ins, plus an editorial.The main feature is called "The civilisation myth: How new discoveries are rewriting human history". It's about the great transformation that began around 10,000 years ago, when societies that were based around hunting and gathering instead took up farming, city living, writing and the other accoutrements of modern life. In particular, it's about why our ancestors did this - and whether the reasons were the same for every society.

The first tie-in story is called "The societies proving that inequality and patriarchy aren't inevitable". It explores the enormous diversity of past societies, many of which can't be neatly fitted into simple categories like "monarchy" or "authoritarian". For example, the degree to which men have dominated society varies considerably.

That leads into the other tie-in story: "Utopia: The ancient discoveries that point to the ideal human society". For this, I asked the anthropologists what they would change about our society. They had quite a lot to say about this, ranging from ending systemic racism to reducing wealth inequality in order to reduce the risk of violent unrest.

Finally, I wrote an editorial called "History reveals vital new lessons in how to make our societies better". Whereas the main features are focused on synthesising what the various experts say, this is more my interpretation. My main argument is that we all have a lot more power to influence the course of history than we think.

The stories are all in issue 3445 of New Scientist, which is in shops now.

Even after all that, I still had some material left over. In the interests of sustainability and reducing waste, I'm going to use it for this month's Our Human Story email newsletter for New Scientist.

Published on June 30, 2023 02:38

May 19, 2023

Star Trek Picard season 3: A very late review

I finally finished watching season 3 of Star Trek Picard. I realise everyone was done talking about it weeks ago, but I have a bunch of thoughts percolating in my head and they won't go away, so I'm writing them down.

I finally finished watching season 3 of Star Trek Picard. I realise everyone was done talking about it weeks ago, but I have a bunch of thoughts percolating in my head and they won't go away, so I'm writing them down.Opinions on the series seem pretty divided, with some saying it's the best bit of Star Trek since [insert date in the long-ago times] and others that it's little more than nostalgia bait.

I think it's a bit of both. There were a lot of incidents and developments that got a proper emotional reaction out of me. But some did so more cheaply than others. To use a culinary metaphor, some of the storytelling choices are satisfying home-cooked meals while others are unprocessed junk food.

In case this wasn't obvious, this review contains FULL SPOILERS.

First, the positives. Here's a short list of things I thought were properly good:

Jack Crusher as a characterThe Borg's plan to sneakily assimilate everyone by spreading Picard's Borgified DNARo LarenThe crew of the TitanSeven becoming the captain at the end

I also can't deny that seeing the Enterprise-D again was a bit of a moment. Obviously it's nostalgia bait, but I thought it made enough sense in context that I went with it.

However I also kept running into issues with the story. In a vague attempt to be systematic, we'll call them the four Cs: contraception, Changelings, consequences and conclusions.

Contraception

It's clear from context that Jack wasn't planned, so Crusher got pregnant accidentally. But this doesn't make sense. Contraception in the 21st century is advanced enough that we can prevent the majority of unplanned pregnancies. Futuristic contraception ought to be way better. Combine that with the fact Picard and Crusher are both educated professionals, and an accidental pregnancy looks unlikely. Even if it did happen, Crusher could have had an abortion.

For such a central plot point, it's clumsy. Two characters who previously handled their relationship with maturity are suddenly stupid teenagers.

This isn't the first time the show has pretended the future is weirdly primitive in order to create a story. In season two, it's revealed that Picard's mother was mentally ill, so her husband locked her in a room to stop her hurting herself. Even today we know that's cruel and counterproductive, which is why it's illegal.

I understand the impulse to have actual conflict, rather than everyone just calmly getting along and solving problems. But stuff like this feels forced.

Changelings

Great to see these folks again. Just two questions:

Why are they helping the Borg? It seems to be out of sheer malevolence, but like most such motivations it makes no sense. The Changelings hate non-shapeshifters, derisively calling them solids. Wouldn't the Borg be the ultimate solids? Also, surely the Borg's new genetic assimilation technique could also be applied to the Changelings? You'd think they'd be at least a bit worried about that. All of which could be sorted out if there were, for instance, multiple Changeling factions so we could see them hashing these issues out. Instead the Changelings are reduced to moustache-twirling villains.

What did we learn about the Changelings that we didn't know before? For all the screen time they get, nothing new emerged. We don't understand their culture or history any more than we already did. They're just being used as a plot point, and as a smokescreen to delay the obvious reveal that the Borg are the main villains.

Here I think the show's desire to spring surprises on the audience has worked against it. By holding back the reveals of the Changelings and the Borg, the show ends up spinning its wheels when it could be fleshing out its antagonists.

Consequences

Over its three seasons, Star Trek Picard has made a lot of big choices, and hardly any of them matter.

At the end of season one, Picard died - except he was reborn in a synthetic body and went on just like before.Data also died, again, except now he's back.At the end of season two, Agnes became the new Borg Queen, with the promise that this would in some way transform the Borg. But in season three there's no sign of her and we're back to the original Borg Queen.

At the end of season two, Picard was in a relationship with Laris, but she gets shoved to one side at the start of season three and never seen again.Q died in season two, except it turns out he can still pop up whenever he likes.In season three, Ro Laren died - except I've seen an interview with showrunner Terry Matalas in SFX where he says he left her an out. Same for Shelby, who got shot by a Borg, but who Matalas says may or may not be dead.

What we have here is something like the Star Wars sequel trilogy, the story of which lurched around from movie to movie. It's a series that's been pulled in twenty different directions, because its creators never agreed on what it was. Consequently, all sorts of interesting ideas have been brought up but then discarded, and the whole thing is wildly inconsistent despite heavy serialisation.

And that brings us to:

Conclusions

The only reason Star Trek Picard exists is that The Next Generation doesn't have a proper ending. Well, technically it ended twice, but neither was definitive.

The TV show ends beautifully with "All Good Things..." but that was written in the full knowledge that movies were coming. Hence it offers a potential future for the characters but then undoes it all, and ends with them all still together on the Enterprise-D. It's a deliberately open ending. I love it.

And then there's Nemesis. This offers endings for Data (dead, with a potential out) and Riker and Troi (married, off to another ship). In the process it undoes Worf's ending from Deep Space Nine, and does absolutely nothing for Picard, La Forge or Crusher. Also it's rubbish, but my point here is that it's not a conclusion.