David B. Williams's Blog

October 13, 2023

Street Smart Newsletter

Every week I write a newsletter about human and natural history in the Pacific Northwest. Ranging from glaciers to escalators to wooly dogs, the newsletter is my way to continue to share stores of my rambles and observations, as well as updates on my books, walks and talks. If you are interested in signing up for it, it is free though you can also get a paid subscription, which helps me continue to write them.

Here’s the link to sign up. I’d be honored if you did.

Here are some of my favorites.

Erratic Behavior – Stories of those wonderful rocks carried by glaciers

Woolly Dogs – An exploration of the region’s native dogs and one of the few animals domesticated for their wool.

When Fill Fails – It’s a mess under the Light Rain tracks around the Kingdomes. Why?

April 20, 2023

The Giddiness of Time

As a geogeek who sees the world through obsidian-tinted lenses, I have long been interested in time, particularly what John McPhee called the deep time of our planetary past. Stretching back 4.54 billion years, that great abyss of eons is why the world looks as it does. Deep time is what makes possible the ever-so-slow diving of the Juan de Fuca Plate under North America, which gives the PNW our dynamic landscape. Deep time is what allowed microscopic organisms to evolve into the myriad of species that grace, have graced, and will grace our little planet. Deep time is what allows me to type this newsletter using minerals that formed millions of years ago.

Although deep time manifests itself in many ways, it resonates more strongly in some locations. One such place is in downtown Seattle at the southwest corner of 2nd Avenue and Marion Street. There you will find a rather lovely art deco structure, the Exchange Building, originally built to house the city’s commodity exchanges. Alas, it opened in 1930 and the Depression prevented the building from meeting the owners’ great expectations. (Talk about bad timing!) But they did choose wisely with their building stone, the Morton Gneiss of Minnesota.

If you want to subscribe to my newsletter, here’s a link.

With its swirly pink and black layers, the Morton has a dynamic feel, as if the rock was still forming. In one panel rafts of jet black basalt sit like islands awash in a sea of pink. Other building panels look like photographs of blood streaming through arteries, a texture that quarry workers called veiny. But the dominant pattern resembles what would happen if you took a series of photos while stirring together cans of pink and black paint, known as flurry in the lingua franca of stone.

More germane to my interests, the Morton Gneiss is 3,524,000,000 years old, or some serious deep time. As John Playfair wrote in the 18th century “the mind seemed to grow giddy by looking so far into the abyss of time.” The rock is so old that when it formed Earth didn’t look anything like it does now. The oldest evidence for life is also about 3.5 billion years ago, which means that the surface of the planet back then lacked any of the plants or animals or other life forms that provide the colors and textures and chaos we know today. Instead, the surface was probably fairly muted in palette except for the shades of water and lava. Nor, as I noted two weeks ago, were there any of the sounds that began to come into existence relatively recently.

3.5 billion years ago is so deep in time that the planet may not have functioned as it does at present. The basic way geology works, as has been taught for fifty years or so, is plate tectonics, that the surface of the Earth consists of slabs, or plates, in constant motion. Their jostling is responsible for earthquakes, volcanoes, and all the major planetary processes. But one question remains: When did plate tectonics begin? The answer ranges from one billion years ago to three billion or earlier. In other words, the geological processes that formed the Morton Gneiss may or may not have been ones that operate at present, which I think it PDN, or pretty darned nifty.

Whenever I lead building stone tours in downtown Seattle, I always stop by the Exchange Building. I tell people that the Morton Gneiss is most likely the oldest rock they will ever see. (I know it’s the oldest I will ever see because the older rocks are a long way from anywhere in the Northwest Territories.) I also urge them to touch the Morton Gneiss, to reach back, back, back to the early days of Earth and to bond with the deep time that binds us all together.

My first two tours with the Field Trip Society sold out so we added two more.

Stories in Stone – June 11 – 2pm – Field Trip Society – My downtown walk exploring building stone, including the Morton Gneiss.

Too High and Too Steep – 1pm – Field Trip Society – We’ll look at the Denny Regrade and the often overlooked but still existing evidence of the topographic changes.

I have been meaning to recommend a couple of newsletters I read. Here they are.

Finding Words – A kindred spirit, David Lukas has a deep love for language and nature and weaves them together weekly. Check out this one on Lewis and Clark.

Taking Bearings – Adam Sowards’s thoughtful take on history and place. This one looks at the Centennial Trail, also a special spot for me.

Southwest Wawa – I first encountered Owen Lloyd Oliver through his Indigenous Walking Tour of the UW Campus. He continues to be insightful and observant in his writings, including this one about the Super Bowl.

February 21, 2023

Newsletter

Greetings. I had hoped to keep this page updated with my newsletter but clearly I haven’t. The best way to stay up to date is to subscribe to my Street Smart Newsletter.

Thanks kindly.

July 28, 2022

Urban Stalactites

Last week I wrote about looking down. This week I want to write about looking up, though my first example is of looking slightly down and across.

Riding Light Rail the other day, I noticed a curious geological feature at the Tukwila Station. Hanging down from the platform were stalactites, those classic cave structures. The urban ones in Tukwila were a half inch to several inches long and resembled soda straws, another term for them. They are also known as neoformations and calthemites (for the Latin calx, meaning lime; the Latin théma, meaning deposit; and the Latin -ita, a suffix indicting a rock or mineral) and are wide-spread across urban landscapes.

The key to their formation is the weathering of concrete. As I noted in a previous newsletter about lime kilns, concrete consists of cement (lime) and an aggregate. When water penetrates the concrete and seeps along fractures, it can pick up and carry calcium hydroxide. If the water reaches a surface in contact with air, the calcium hydroxide mixes with atmospheric carbon dioxide and leads to the formation of urban stalactites made of calcium carbonate, also known as the mineral calcite, and by the way, the second ingredient in Tums, after sugar.

For those who are interested, here’s the equation. From Garry K. Smith, Calcite Straw Stalactites Growing from Concrete Structures, one of the best papers on the subject. One point of caution, the solution that forms is very alkaline (pH13) and will burn your eyes or skin.

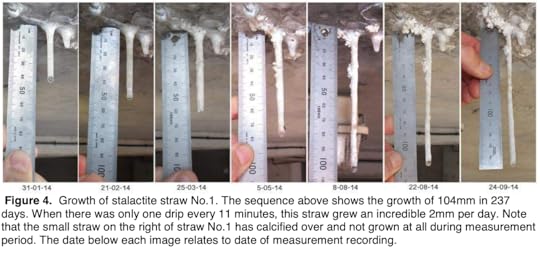

Water in concrete, particularly where calthemites form, comes from precipitation, gutters that leak, air conditioners, sewer pipes, and the like, says Garry K. Smith, an Australian caver and expert on calthemites. He found that soda straw growth depends on drip rate with maximum growth (2 mm/day) occurring when there are 11 minutes between drips. That growth rate is up to 360 times faster than occurs in caves. The longest calthemites are up to a meter long but most are less than eight inches. Smith told me that if the rate is too fast, on the order of 1 drip/minute, no stalactite forms though a stalagmite may develop below the drip.

Image also from Garry’s paper, listed above.

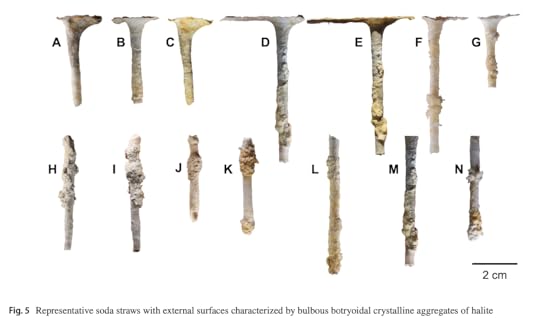

Calthemites are quite varied in texture and color, though most are white to taupe. The different hues result from metals encountered by the water during its travels through the concrete. Copper pipes lead to shades of green and blue and iron pipes impart orangish-reds. Halite (table salt) can also affect calthemites but mostly in the surface topography. If left undisturbed, urban stalactites can last forever, says Smith, though they are hollow and could break due to wind or being bumped by a person or beast. He notes that another problem is that the alkaline, or basic, chemistry of the drip can damage car paint, which would probably trigger removal, or at least staunching water movement.

From: Paul L. Boughton, “Morphogenesis and Microstructure of concrete-derived calthemites,” Environmental Earth Science (2020) 79:245.

In Seattle, calthemites form in a variety of locations, including tunnels, overpasses, the undersides of bridges, parking garages, and basements. (With all of the graffiti covering these types of locations, they’re sort of like our own small scale modern Chauvet Cave.) The key, as noted above, is concrete, as well as water. As we Seattleites try to deal with this summer’s heat wave, what could be better than exploring for urban stalactites in a dark place, underground or under a big concrete structure? Have fun.

Calthemites under I-5 where it crosses over Weedin Place. Longest stalactite looks to be about 6-7 inches.

I would like to thank Garry K. Smith, who provided helpful information and who has written about calthemites here and here.

Please let me know if you know of/find any of these splendid little formations.

If you’d like to subscribe to my newsletter (either free or paid), here’s a link.

July 22, 2022

My Favorite Maps

I freely admit that I have probably spent too much time looking down at my feet while exploring Seattle. I have probably spent too much time looking up, too. But whether I gaze skyward or sidewalk-ward, I am often rewarded. For instance, I think I am one of the few people to notice several duck tracks in concrete and to connect them to the duck in terra cotta just a few blocks away. I guess I just have an affinity for making brilliant deducktions. (I know, groan, but I couldn’t pass it up.)

Far better known than the tracks are the hatch covers throughout downtown. (Since personhole cover is a disgusting term and manhole a problematic term, hatch cover or utility cover are the preferred names.) The idea for Seattle’s hatch cover art began in 1975 after Seattle Arts Commissioner Jacquetta Blanchett traveled to Florence and saw the city’s hatch art. Working with Department of Community Development director, Paul Schell, Blanchett donated enough money to fund 13 covers, with six more paid for by other donors. Each cost $200 and weighed 230 pounds. There are now numerous designs adorning our streets.

My favorite hatch cover, of course, is a map, first put in place in April 1977, on the north edge of Occidental Park. It is still there.

Anne Knight designed the map. A map was natural because Seattle had such a “graphically interesting street pattern,” she said. Anne thought that the map covers would make an excellent teaching guide, as well as a guide to the city. If you look at the covers (except one), you will see there is no compass. A City of Light employee had told Anne that one thing he didn’t want was a compass on the map. Otherwise, the crews would have to orient the cover correctly each time. So there is no compass, though there is a map, which one would hope wouldn’t be too challenging for the City of Light crews to orient. Apparently it is. Despite Anne including a small welded bead on the outer ring of each cover to facilitate easy alignment, nearly all of the covers are misaligned at present.

Anne told me that a police officer had heard about the project and called her to say he was concerned that pedestrians would be stopping in the middle of the street to look at the maps. She told him not to worry as she had only chosen spots on corners.

Each of the maps includes city landmarks, such as the post office, the Seattle Public Library, King Street Station, and Denny Park. You can figure out which one is which by looking at the key on the map’s outer edge. All of the landmarks still remain except for the Kingdome. “At the time it had just been built and I thought naively that it looked like it was a structure that would be there forever,” Anne said.

Curiously, the manhole cover on Second Avenue between Spring and Seneca has a unique, post 1975 landmark on it. That landmark is the Seattle Art Museum. In order to fit that landmark on the key, Harborview Hospital was dropped. The map is also the only one not on a corner. (Anne does not know the exact origin of that cover; a special one was made for the Seattle Art Museum but it was removed when the Hammering Man fell and damaged it.)

As you can see from the accompanying annotated map, not all of the original covers exist. I could locate 14, plus the later one added on Second Avenue. One is now in Kobe. (This one had been moved to an alley and a City of Light employee had removed it and happened to have it in his truck when he attended a sister city meeting and suggested sending the cover to Kobe.) Several others have been moved and/or removed with their whereabouts unknown. Another that was on the original list apparently was never in that location and there is one at the Seattle Center at the northwest corner of the fountain lawn at what would be the SE corner of Republican St (August Wilson Way) and Second Ave N.

These manhole maps are one of the delights of Seattle. So next time you are out walking around downtown, take a look down at your feet. You might be amazed at what you find. And, watch out for that terra cotta duck. Who knows where she’ll land next.

I also know of one other map hatchcover. It’s at Waterway 15, at 4th Avenue NE and NE Northlake Way, on Lake Union.

This posting is part of my Seattle Street Smart newsletter. If you are interested in subscribing, here’s the link.

July 7, 2022

Has Blackberry Met its Match?

Recently while biking on the Burke Gilman Trail near Gas Works Park, I was struck (not physically mind you, in case you worried that I suffered a shrubbery injury) by the lush fennel along the trail. In some places, the plants formed great thickets that were dense enough to preclude the growth of another non-native invasive, Himalayan blackberry. (Actually a native of Western Europe, these blackberries arrived in our part of the world because of horticulturalist Luther Burbank.) If fennel is that aggressive, and able to replace blackberries, that could be an intriguing development, perhaps inspiring more people to use this fragrant plant.

Such growth though is also problematic. Common fennel, or Foeniculum vulgare, for the scientifically inclined, has been classified by Washington State as a Noxious Weed. The problem, as illustrated on the Burke Gilman, is that non-native fennel can outcompete and crowd out native plants. Less problematic and rather impressive is the way fennel appears to kick some blackberry butt. Which exact fennel subspecies is spreading, and whether it actually does spread, is a bit controversial but if you have ever planted fennel or seen it appear and rapidly take over an area, you know that at least some varieties are quite capable of proliferating like rabbits (so to speak).

Native to the Mediterranean and temperature parts of Africa, fennel has spread globally with a host of names, such as mieloi (Basque), bad (Hindi), phase (Lao), phak chi (Thai), and finnuchio (Italian). Tall plants can easily be more than six feet with anise-scented and -flavored foliage, and bright golden flowers in terminal umbels (revealing their carrot family affinity). Over the centuries people have found many medicinal uses for the plants, including abdominal pains, antiemetic, aperitif, arthritis, cancer, colic in children, conjunctivitis, constipation, depurative, diarrhea, diuresis, emmenagogue, fever, flatulence, gastralgia, gastritis, insomnia, irritable colon, kidney ailments, laxative, liver pain, mosquitocidal, mouth ulcer, and stomach ache, as well as improving the milk of breastfeeding mothers, removing any foul smell of the mouth, and coloring textiles. Why aren’t more of us eating fennel all the time? It’s clearly the wonder plant that could save us.

Fennel isn’t the lone Mediterranean plant that seems to be proliferating in Seattle. Artichokes are everywhere. I don’t know if planting them is this year’s fad or I just happened to notice their lovely purple spikiness more often. With climate change perhaps Seattle is becoming more hospitable to them, though I don’t think any will get as big as this one I saw down in California. But we can dream, especially if one have access to large vats of butter. YUM!

Word of the Week – Mosquitocidal – An agent employed to kill mosquitoes. Mosquito comes from the Spanish, which seems to derive from the Latin musca, in reference to fly. (One origin story for the name for Moab, Utah, comes from the Ute word Moapa, meaning mosquito water.) Given the way English has so many letters with many sounds, it’s not surprising that mosquito has perplexed spellers for centuries. Examples include muskitoes, musketas, mosqueta, muskeito, musqueetoes, muscato, moscheto, musqueto, and moschitoes. Cide comes from the Latin -cīda, meaning killer or slayer.

And, thanks to all who subscribed to my newsletter last week. I deeply appreciate your support.

To subscribe, here’s a link.

A Top Secret Bunker and a Nobel Prize

As an urban researcher, one of my most exciting “discoveries” over the years was the underground building at Pigeon Point, the ridge that comprises the east side of West Seattle. I first heard about it when I was putting together a walk for my Seattle Walks book. Someone had told me about a facility or building on Pigeon Point where they (whoever they was) had spied on the Japanese in World War II or conducted some sort of weird animal experiments. When I began asking around, I heard hints and tidbits, rumors and rumblings, scuttlebutt and speculation, so I did what I often do, I headed to the archives to find the truth.

At Special Collections at the University of Washington and the National Archives on Sand Point Way NE. I found documents that enabled me to piece together a story that not only confirmed the hearsay but made the truth even more interesting than I suspected.

In 1900, the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps began an ambitious project to establish a network of isolated outposts across Alaska, all linked via telegraph lines. The ultimate goal was to connect Alaska to the United States (Alaska wasn’t a state then) through a transmitter base in Seattle. Known as the Washington Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS), it consisted of 1,497 miles of telegraph wires and 2,128 miles of oceanic cable (the copper conductor in the cable weighed 130 pounds/mile). It was completed in late 1904 and was heralded as one of “the greatest feats of electrical engineering the world has seen,” at least in the Seattle newspapers.

Jump forward to World War II, when the US War Department decided it needed bomb-proof radio facilities in Seattle for the Alaska Communication System (WAMCATS became ACS in 1936) to handle essential wartime information about the north and points further west. Work began in West Seattle at Pigeon Point in 1942 and transmissions started in 1943. The site eventually totaled 44 acres and consisted of several tuning huts, housing, a five-car garage, and the concrete transmitter building. Built underground so it would be less vulnerable to attack, the bomb-proof structure had four-foot thick walls covered by a nine-foot thick detonation slab of reinforced concrete.

Following the war, use of the facility waned until the US Government decided to sell the property. The University of Washington bought it in 1958 to use for antenna and radio science research and later for cosmic ray studies and oncology experiments. Taking advantage of the bomb-proof, and apparently radiation proof, underground building, oncology researcher E. Donnall Thomas irradiated dogs that had lymphoma with cobalt 60 to help understand why bone marrow transplants typically failed. His work with dogs (mostly pets, which had been referred to Thomas and his colleagues) continued with humans, who were irradiated and then transferred from Pigeon Point across town to what was the US Public Health Service Hospital (aka Marine Hospital, Pac-Med Building). The work was so successful that Dr. Thomas won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1990 for his work on bone marrow transplantation research.

By the time Thomas had won the award, the UW had abandoned the bunker and the surrounding acreage and the Seattle Parks Department and Seattle Schools acquired the land and facility in 1998. It is now the home of Puget Park and the Pathfinder K-8 school. On the 1998 plans to build the school, then designated as Cooper Elementary, there is a note reading “Underground Research Lab to Remain,” with no additional explanation. The subterranean facility is still there, located, as you can see below, at the north end of the entry road in front of the school. There is no entrance to the bunker and no sign to indicate the story hidden beneath.

Subscriptions – Wow, hard to believe that it’s nigh unto July. Two of my highlights of the past six months has been writing these newsletters and the kind responses that people have sent in. I am still having fun with them and look forward to what the next six months brings. My weekly newsletter will continue to be free with an option to contribute as a paid subscriber. If you feel inclined to do so, I would sincerely appreciate it.

Word of the Week – Pigeon – An Anglo-Norman word in reference to a young bird. The origin of the name Pigeon Point is clouded in the shrouds (if that’s physically possible) of time. It could, but probably doesn’t, refer to band-tailed pigeons (Patagioenas faciata), which are migratory birds of wet forests that visited but probably did not reside in this area; or to feral pigeons (aka rock dove), which probably arrived here soon after the first European settlers. In Arthur Denny’s granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s When Seattle Was A Village, she wrote “A long time ago, when Seattle was young and mud flats extended from Yesler’s Mill to Duwamish Head…on a promotory, wild pigeons roosted on Pigeon Point.”

February 10, 2022

Newsletter

I am rarely updating my blog at present.

Instead I have created a weekly newsletter about human and natural history around the Pacific Northwest. Each one addresses a recent adventure, story in the news, or a tidbit of history, such as a hike up the Oyster Dome, which prompted observations about time travel to the last ice age; finding a house from the Denny Regrade now located on Lopez Island; or my obsession with maps around Seattle.

Sign up is easy. Just follow this link. I look forward to sharing these stories with you.

April 25, 2021

Puget Sound Quiz – Answers

Okay, time for the big reveal. Here are the answers and, in case you didn’t suspect it, all of them but one are found in Homewaters, which you can buy direct from me, with a signature. (Cost is $33, which includes shipping, taxes, and autograph.)

Answer A. In 2009, archeologists found hundreds of pieces of basalt, rhyolite, dacite, and chert, which had been hewn into projectile points, knives, scrapers, and hammerstones. The site is located along Bear Creek. No coffee mugs were found: apparently the Bear Creek people eschewed coffee, or at least mugs.Answer B — The geoduck was found near Richmond Beach and dated by counting the growth rings. A 205-year-old rougheye rockfish was found in Alaska and biologists have determined that red sea urchins have the possibility of cracking two centuries in age. Both species live in Puget Sound, so Answer D could also be correct.Answer C – Bing Crosby did have an ancestor with the name of Clanrick, who did pilot steamers, but he didn’t operate the Capital. The answer is the story. The Capital lived to steam again after its short and muddy stroll.Answers A and D – The answer depends on whether you think that Apostolos Valerianos, better known as Juan de Fuca, saw his eponymous strait or not; most historians think he did not. If not, then the first is Frances Barkley , wife of Charles Barkley, who was the first European woman to reach this region, in 1787. So, being the generous soul I am, I consider both to be correct.Answer B – Built to protect the Sound from enemy invaders, the Triangle of Fire, which consisted of Forts Flagler, Casey, and Warden, was at its maximum strength in 1910. No shots were ever fired at any enemy. I am just glad it’s not Answer A, as that sounds dangerous.Answer C – xw̌əlč is normally translated as salt water and is the oldest known name that refers to the body of water we call Puget Sound.Answer A, C, and E – Quimper, Fidalgo, and Haro are three of the many Spanish names on the landscape, a clear reminder of Spanish exploration in this region, an often overlooked part of the area’s history.Answers B and C – Wilkes generally chose pretty straightforward names, such as Fox (ship surgeon John L. Fox) but he also included a couple of curiosities, such as Bung Bluff (south end of Herron Island) and Ned and Tom (near McNeil Island), which never made it onto any maps. Answer B – Yep, you guessed it, those guns were powerful enough to lob a shell from tech giant to tech giant.Answer D – Eighteen species, in one of the richest areas of kelp diversity anywhere, make their home in Puget Sound. Answer B – Sea urchins are a primary consumer of kelp and if their numbers aren’t kept in check by animals such as sea otters, they can ravage a kelp forest. Sadly seersuckers have long been on the decline in Puget Sound though sartorial sightings are periodically reported.Answer B – Although they sometimes refer to themselves as age readers, sclerochonologists (sclero-meaning hard or hardness; and chrono-or time) figure out the age of fish by counting growth rings. They are very very patient and precise people. Answer B – In the 1940s, there was a perceived need for Vitamins A and D and Puget Sound fishers and processors capitalized on this by harvested millions of pounds of sharks. All that was “needed” were the livers so the rest of the fish was tossed, unused for any purpose. Answer D – Although such an intriguing specimen was found, apparently none of the archeologists made any such comment, but I did compare it to a turducken. It’s in the book.Sadly, it is Answer D. Nearly all of us contribute to this phenomenon of putting more of these pollutants in Puget Sound. PAHs also impact salmon and rockfish.Answer D – Our namesake Peter Puget had an eye for the flowers. Answer B – Not only did Charles Wilkes leave behind a legacy of names, he also thought rather highly of the inland sea. Answer A – The Rafeedie decision has been called the shellfish equivalent of the Boldt decision.Answer D – One of the hallmarks of this region, according to Butler and Campbell, is that over thousands of years of catching and consuming fish, the Coast Salish peoples did not deplete their most important food source. They write that there are many lessons to learn from this behavior.Answer B – Like many early writers in local papers about steamers in the Sound, the author complained. “Though they take a whole week to make a twenty-four hours’ voyage, they hurry in and out of a way-port as if the devil or a sheriff was always after them, and the people generally are beginning to indulge the hope that one or more of those personages may speedily catch and keep them.”15-20 correct – I will seek you out the next time I write about Puget Sound.

10-15 correct – Sit back, relax, and enjoy the beauty of Puget Sound, knowing you know some cool info about it.

5-10 correct – Sit back, relax, and enjoy the beauty of Puget Sound, knowing you learned some cool info about it.

0-5 correct – Have I got a book for you to bone up on your Puget Sound facts.

Here’s a link to order Homewaters direct from me, if you feel you want to get 100% on the next quiz.

April 13, 2021

Puget Sound Quiz

With the publication of Homewaters, I thought it would be fun to create a little quiz related to Puget Sound. I will also provide the answers next week.

1. The oldest archaeological evidence for people in Puget Sound was found in Redmond and dates from at least 12,500 years ago. What is it?

a. Hundreds of pieces of rock used to make tools.

b. Bones from a giant sloth with an embedded antler projectile point.

c. Pieces of a canoe.

d. MS-DOS branded coffee mug

2. What is the oldest known animal collected in Puget Sound?

a. A 205-year old rougheye rockfish

b. A 173-year old geoduck.

c. A 200-year old red sea urchin.

d. All of the above.

3. What is famous about the steamer Capital?

a. It was the second steamer to arrive in Puget Sound.

b. It was piloted by Bing Crosby’s great-granduncle Clanrick Crosby.

c. After being abandoned by its captain, the paddlewheeler continued spinning and sort of walked itself across the tideflats at Olympia.

d. It inspired Karl Marx to name one of his books.

4. Which of these sailors was the first European to see the Strait of Juan de Fuca?

a. Apostolos Valerianos

b. James Cook

c. George Vancouver

d. Frances Barkley

5. What does the Triangle of Fire refer to?

a. A flaming Hamentashen

b. Forts Flagler, Casey, and Warden

c. Amazon, Microsoft, and Starbucks

d. Insignia on Boeing planes during WWII

6. The Lushootseed word for Puget Sound is xw̌əlč, often written in English as Whulge. What does it mean?

a. Beautiful place

b. Salt water

c. Home

d. None of the above

7. Spanish explorers were the first known Europeans to sail down the Strait of Juan de Fuca. What place names reflect Spanish influence? Choose all that apply.

a. Quimper Peninsula

b. Eld Inlet

c. Fidalgo Island

d. Strait of Georgia

e. Haro Strait

f. Toandos Peninsula

8. Captain Charles Wilkes brought the US Exploring Expedition into Puget Sound in 1841. More than 260 of his place names are still on maps. Which of these names he created are not on modern maps? Choose all that apply.

a. Fox Island

b. Bung Bluff

c. Ned and Tom

d. Vendovi Island

e. Port Townsend

f. Bainbridge Island

9. Fort Warden formerly had disappearing guns, mortars, and barbette guns. A 12-inch disappearing gun could shoot a half-ton shell how far?

a. Length of a typical pre-pandemic Seattle traffic jam

b. From the Amazon HQ to the Microsoft Campus (~10 miles)

c. To hell and back

d. A stone’s throw

10. How many species of kelp live in Puget Sound?

a. Fewer than 5

b. 5-10

c. 10-15

d. 15-20

11. What are some of the most voracious predators of kelp and why have they proliferated?

a. Seersuckers, because they are well suited to consuming seaweed.

b. Sea urchins, because of the overhunting of sea otters, which formerly kept urchin populations in check.

c. Ratfish, because they sort of look like rabbits and breed like them, too.

d. Kelp rockfish, because they have grown larger with climate change.

12. People who study the age of fish by counting the annual rings on the ear bone, or otolith, are called?

a. Fish whisperers

b. Sclerochronologists

c. Chronotolithophiles

d. Bone accountants

13. In the 1940s, the Seattle Times proclaimed Seattle as the “Vitamin A-D Capital of the World.” Why?

a. Scientists at the UW had invented an artificial method to produce the two vitamins.

b. Much of the nation’s vitamins A and D came from the livers of soupfin sharks and Seattle was a major processor of the sharks.

c. Botanists at the UW had discovered a source for the vitamins in Douglas fir trees.

d. It was an April Fool’s day story.

14. At the Old Man House in Suquamish, archaeologists unearthed a curious find of a herring nested in a littleneck clam nested in a butter clam. They described it as what?

a. A precursor of the modern food trend of spending too much time making your food look pretty.

b. A precursor of a turducken.

c. A precuror of a fish stick.

d. None of the above.

15. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a significant pollutant in Puget Sound, causing malformed hearts in herring embryos. What produces PAHs?

a. Burning oil and gas

b. Driving a car

c. Cooking meat

d. All of the above

Quotes

16. The flowers were “by no Means unpleasant to the Eye.” Who wrote this?

a. Archibald Menzies

b. David Douglas

c. Jimi Hendrix

d. Peter Puget

17. “There is no country in the world that possesses waters equal to these.” Who wrote this?

a. Seattle Chamber of Commerce brochure 1934

b. Charles Wilkes

c. Peter Puget

d. Bertha Knight Landes

18. Danica Sterud Miller, professor of American Indian Studies at the University of Washington, told me: “[The] Rafeedie [decision] was about reaffirming our language, decolonizing the space, and reasserting our ability to self-determine. It was a profound moment.” The Rafeedie decision refers to what?

a. A law case that resulted in 1994 in a 50/50 split of the shellfish harvest between tribal and nontribal harvesters.

b. A law case in 1945 that resulted in the 50/50 split of the salmon catch between tribal and nontribal harvesters.

c. A law case in 2016 that resulted in the denial of permits for a coal port at Cherry Point.

d. A law case in 1989 that resulted in the federal recognition of geoducks as a premier species.

19. Archaeologists Sarah Campbell and Virginia Butler wrote in a 2010 paper that fish managers should make a “greater investment in the activities that foster direct connections among people, fish, and other resources.” What was this in reference to?

a. Encouraging more investement in urban streams and habitat.

b. Encouraging less reliance on isolated technological fixes that focus only on salmon.

c. The archaeological record of fish bones that showed that Native people sustainably harvested salmon for more than 7,500 years.

d. All of the above.

20. “Steamers come and go “like a thief in the night,” and no man knows the day nor the hour.” Who wrote this?

a. Murray Morgan, Puget’s Sound

b. Seattle Weekly Gazette, August 20, 1864

c. Peter Puget

d. Hazel Heckman, Island in the Sound