Ganesh Swaminathan's Blog

February 6, 2021

From The Beginning Of Time By Ganesh Swaminathan

Maria Wirth January 3, 2021

It hardly ever happened in recent times that I read a book from cover to cover within a few days, due to the huge daily influx of information via the internet. But it happened after I received “From the Beginning of Time — Modern science and the Puranas” by Ganesh Swaminathan.

The Puranas fascinate me, ever since I started many months ago to study the Srimad Bhagavata Mahapurana (1700 pages in English) and I am glad that more and more books come out on the Puranas.

It seems that slowly the realization dawns that the Puranas are an incredible treasure house of knowledge in many fields — knowledge that is so vast and a lot of it so ‘far out’ that it actually couldn’t be obtained by mere humans stationed on earth.

Strangely the impression was created (by whom?) that the Puranas are only mythological stories, about fights between gods and demons and about the life of Avatars. And they are mainly meant to promote a dharmic, righteous life and devotion for the Divine in common people through stories, as Vedic philosophy is too complex for them. At least that was the impression I got in my early time in India.

It is often not known, that all the 18 main Puranas start with the creation of the cosmos, a fact, that should make us sit up and reflect. Who could have recorded it? Who was present? Or is it just all plain imagination, like the fairytale that God created the world in 6 days some 6000 years ago, which has been disproven by now, as science estimates that the world is 4.5 billion years old.

The author puts the spotlight on the rational aspects or interpretations of the Puranic stories of creation. He wants to show that those stories are not fairytales but amazingly in tune with the modern scientific framework in regard to the topics he selected.

The topics are: the lifecycle of the sun, the moon, the history and geography of the earth, and the different lokas above and below our earth. Further, the descent of Ganga, the story about the Great Flood in different cultures, and the Puranic universe in general with its huge timelines have also chapters in the book with many quotes from different Puranas. Those quotes make the book a worthy read in itself.

The author gives first a detailed, informative summary of the insights of modern science regarding these topics, for example from postulated or observed astronomical phenomena and events, and then compares them with the stories in the Puranas and his interpretation.

Not surprisingly, in many instances, the scientific and Puranic view are close to each other, for example the 5 stages of the life cycle of the sun or that water came from outer space, or that the moon rises each day next to another star (nakshatra), etc.

In other instances, the interpretation of the author can be open for debate, for example his view that the North Pole could be seen as Mount Meru.

The author expresses his surprise how such old texts, like the Puranas, could know what modern science knows. However, it may be more surprising how science could discover this knowledge. The book starts with a quote from the Brahmanda Purana:

“Hence listen to this summary. Narayana creates the world. It is on that occasion of creation when he makes this entire Purana. It does not remain at the time of annihilation.”

We live in a time where “divine creation” is looked down upon as unscientific. We take it for granted that “of course” science knows that our earth is part of the solar system, and that we know the other planets, and can trace their position.

Google says that the “five planets were known since ancient times”. And it is made to look as if it is not big deal that the ancients knew about the planets. “They can be seen with the naked eye, is given as an explanation.”

But how to know that certain lights in the night sky full of lights are planets of our sun and relatively close by? While other lights are like our sun and far, far away?

Even if we watch the sky for thousands of years, we cannot come to this conclusion, can we? Only when Indian knowledge contained in the Puranas, Surya Siddhanta, etc., reached Europe, together with math and tables to calculate their position and the constellations in the sky, “science” suddenly took off and models about the cosmos appeared.

At first these models were hampered by the Church. It tried to suppress them to make its religious claims more acceptable. Only 400 years ago, in 1600 CE Giordano Bruno was still burnt at the stake by the Church because he did not recant heretic (Indian) ideas about the universe. But ultimately, the Church had to give in.

Swaminathan credits science with a lot of worthwhile insights, but he also points out that the scientific claims are so far only models. For example the theory that the earth was in the beginning a fire ball got in recent time competition from another theory which suspects that the earth was in temperate water, after probes from 4 billion-year-old stones indicated this.

Incidentally, the Puranas accommodate both these claims. They say that at the end of Brahmas day, the earth first becomes an inferno due to the sun becoming a giant, and then, when the sun diminishes and cools, the heat turns into a deluge of water which submerges everything during the night of Brahma.

Most Indians are familiar with the story of Vishnu incarnating as a boar to bring out the earth which was lying submerged in water at the start of our present cycle of creation, which lasts for a day of Brahma, or 4,32 billion years.

The book is definitely an interesting read. However, in the process of making the Puranic narrative “scientific” the universe becomes lifeless, whereas the quotes from the Puranas project a universe full of life and divine entities. While the Puranas give Brahma the credit for creation, science turns it into dark, lifeless chance.

Would the creation make any sense if there is no awareness inherent in it? Science still sees the awareness in human beings only as a chance by-product of the material brain. Is it possible that this chance consciousness of humans on earth and maybe on some other planets would be the only knower and enjoyer of such an unimaginably vast, mysterious cosmos while everything else is dead matter?

I wished, the author had incorporated the imperative role of awareness and even the possible personification of celestial bodies into the narrative. Most Indians don’t see for example Surya Bhagawan as merely lifeless matter but endowed with awareness and identity. Unfortunately, it requires courage to express such views, as so-called scientists may call one mad.

Yet Hindus could have this courage. Their ancient texts are the basis for modern science. In all likelihood, it won’t take long and Darwin’s theory and the view that the Big Bang happened by chance will go out of fashion.

So why not challenge it already now and stand by the ancient knowledge before the West changes its view?

Regarding the divine origin of the Puranas, the author preferred to let the Puranas speak for themselves. Yet to make it acceptable for “scientific minded” people, he went with the view that they are “2000 years old”.

The last chapter is dedicated to the life and immense contribution of Maharishi Vyasa who not only compiled and simplified the Vedas, but also simplified the Puranas, which were at his time already “old”.

The author quotes from the Matsya Purana that the original 100 crore Slokas were condensed by Vyasa into four lakh Slokas. Even now in Devaloka they have the original number.

What I was missing in the book was a causal connection between the Puranas and the scientific models. The similarities are in all likelihood not by chance but the Puranas would have been inspiration for the modern scientific models.

Incidentally, the Jesuits got the Puranas translated in the 17th century by Brahmins in Kerala and then Jesuits were suddenly at the cutting edge of science, of course only in those fields which the Church allowed. Western universities valued Indian knowledge greatly in the 18th and 19th century.

When Tuebingen University in Germany for example received the Srimad Bhagavata and 10 other ancient Indian texts from a missionary in 1839, the Dean praised them as an ornament for the university and added ruefully that this treasure however is small in comparison to the treasure which the India House in London possesses.

So it can be safely assumed that a lot of modern science is based on the knowledge of the huge body of Puranas.

Some of it may have been misunderstood, too.

For example, it is intriguing that, though till recently the earth was claimed to be 6000 years old, suddenly the age was expanded to a huge 4,5 billion years. Incidentally, the Puranas claim that the lifespan of the earth is 4,32 billion years, which is very close to the estimate.

However, the Puranic calendar claims, that of those 4,32 billion years, by now around 2 billion years have passed in our present cycle of creation or about half a day of Brahma. Is it possible that some western scientist took inspiration from the Puranas but mixed up the lifespan with the present age?

I hope and wish that this book by Ganesh Swaminathan inspires more Indians to take interest in and study the Puranas.

Conversation with Ganesh Swaminathan Author “From The Beginning of Time”

From the Beginning of Time — Modern science and the Puranas by Ganesh Swaminathan is available on Amazon

As published in INDIC Today on Jan 3, 2021

November 18, 2020

MyInd Interview with Ganesh Swaminathan, author of the book, “From the Beginning of Time”

From the beginning of time is your debut book. Before we find out about the book, we would like to know the author. So, could you please tell our readers something about yourself first?

From the beginning of time is your debut book. Before we find out about the book, we would like to know the author. So, could you please tell our readers something about yourself first?I graduated from IIT Delhi with a degree in Mechanical Engineering. I worked as an engineer for a couple of years and then went to the IIM Ahmedabad, where I earned an MBA. Since then, for most of my professional career, I have worked in US multinationals in the field of technology. This has taken me to many countries, including the US, and given me an appreciation of their cultures. I am currently based in Singapore and live here with my wife. I have been an active sportsperson and a voracious reader.

2. Have you always been creatively inclined? What inspired you to write this book?

I cannot claim to have ‘always’ been creatively inclined. In school, I dabbled in clay sculpting and tried my hand at sketching at the IIT. In the IIM, I was the secretary of the Film Club. But my colleagues would likely remember me as a basketball player and someone who cycled from Delhi to Kanyakumari, rather than as a creative person.

This book came to me following a sequence of events. When my father was unwell, I would often visit my parents in India. I was mostly at home and had time on my hands. During a conversation, a friend mentioned that he was reading the Egyptian version of Noah and the Ark’s flood story. I had read a lot about the Flood stories, they are all over the world, and follow an archetype: A divine warning, a great flood, with drawl of the waters and the restart of creation. The Matsya Purana, from what I had read about it, seemed to follow a similar archetype. So I told my friend that the Matsya Purana was probably the Indian equivalent of the same. We agreed that he would read the Epic of Gilgamesh and I the Matsya Purana, and we would compare notes. I ordered an English translation of the Purana, and so started my journey through the texts.

The Matsya Purana turned out to be a text of great sophistication. I soon went on to read the Shiva Purana and the Bhagavata Purana. Later, when I could not find good imprints of other Puranas, I printed PDFs of old publications from the internet and went on to read the Brahmanda, Kalika and the Devi Purana.

I had been interested in space science from school. I had kept abreast of developments through books, articles and videos. By my fourth Purana, it had become evident that the resemblances of the descriptions of the Sun and the Moon to modern science were more than just happenstance. A few similar looking verses can be dismissed as coincidence, but there were whole passages that were quite close. I started making notes, and the outlines of a book began to take shape.

A couple of years back, when I took a break from corporate life, one of my first thoughts was that I now had the time to write a book. The notes that I had compiled became the source material for this undertaking.

3. Why this title?

The word purana in Sanskrit means ‘ancient’. The Puranic stories describe events from the Earth’s distant past. In the Puranic cycle, a Day of Brahma lasts for a Kalpa, about 4.3 billion years. This is preceded by a Night of Brahma, a period during which there is no activity. The book talks about both these periods in some detail. Because of the long Night of Brahma, there is little memory of the previous Kalpa.

Most of the Puranic stories are book-ended by the start and the end of the current Kalpa. The book, at its end, lists out a series of events from the beginning of the present Varaha Kalpa, about 2 billion years ago, and compares them with what we can infer from the geological records. The title refers to a timeline of events beginning with the current creation, the beginning of ‘our’ time as it were.

The story of the Sun’s birth is an event long before the current Kalpa. The Puranas also have references to the beginning of the ‘Universe.’ The book explores these references and how they match modern science. The title also works at this level, which I thought was quite fitting.

In this context, it is useful to cite a verse describing the Puranas existence from the beginning of all of creation:

“Hence, listen to this summary. Narayana creates the world. It is on that occasion of creation when he makes this entire Purana. It does not remain at the time of annihilation.”

Brahmanda Purana Book I, Section i, Ch. 1, v. 174

The verse has been used as the book’s opening quote.

4. Who do you think should read this book, and why?

The book should be of interest to people that like to read about the Indian Heritage and texts. Much of the discussion today has been centered around the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The Puranas have been mined for their stories of moral value, religious practices and cultural symbolisms, and even history. This book explores the Puranas through the lens of science.

This should make it especially interesting for our youth. We have been trained and have gone on to teach our young to be rational and evidence-based. This takes us away from our religious texts whose acceptance is based on faith and not evidence. This book should help our youth realize that there is a lot of science that backs up our ancient texts and energize them to re-engage with these treasures of knowledge.

5. What are the key takeaways, that readers could expect, from the book?

The overarching takeaway is that Puranic stories do not just have religious and moral value but that they have an entire cosmology embedded within them. I want to call out a couple of instances.

Hard as it may be to believe, the Puranas have descriptions of the five stages of the lifecycle of the Sun. A 50-minute presentation on this topic has been uploaded onto YouTube and can be accessed here. The birth of the Sun is similar to the story of the birth of the Sun God Martanda. The description of the Red Giant Sun, termed Samvartakaditya, is chilling in its accuracy; a brief 8-minute video explaining this can be accessed here.

Scientists today agree that practically all the water on the Earth’s surface came from outer space. The narrative of Ganga describes the extraterrestrial origins of the Earth’s waters. The story of the Moon’s origin parallels what we understand from modern science with some interesting differences.

These events, along with many others, are described in the book, starting with a brief description of the current science.

6. Do you have any plans of translating it into Tamil, Hindi and/or other Indian languages?

As the book is presented to various audiences, there has been interest in translating it into regional languages. There are no definite plans just yet.

7. What has been your most rewarding moment after the publication of the book, so far?

One of the steps authors take after writing a non-fiction book is to get it ‘peer-reviewed.’ It was hard to find anybody, at least in my immediate circle, that would have domain expertise in the Puranas, space sciences and the geosciences. As a result, the ‘peer-review’ process went as far as testing for the book’s logic.

The INDIC Academy took an interest in the book, close to its publication. Dr. Nagaraj Paturi, the Director of the Inter-Gurukula Centre and a polymath, read the book and gave it the thumbs up. I later found out that he had written a PhD. paper on the symbolism of the Sun in the Puranas many years ago.

Prof. Mahadevan of IIM Bangalore, and formerly of IIT Delhi, also had a very favorable opinion of the book. To quote:

“What stood out according to me was that you have maintained a wonderful balance between the mere (blind) glorification of the Puranas and arguing that Puranas had all the information that science is saying today.

Presenting Scientific viewpoints and the equivalent perspectives from Puranas side-by-side and leaving the reader to make his/her own judgment and sense of the matter is very good.”

While the book has a lot of science in it, it has been written in a simple language to make it accessible to a non-technical but well-read audience. In that context, to have my mother read the book and give it her thumbs up was probably the most satisfying!

8. You have self-published the book. Why did you choose this route? How has your experience been so far?

I started with submitting proposals to some large publishers, but after a lengthy review, none of them accepted. I, therefore, decided to go ahead with self-publishing. I am grateful to the INDIC Academy for choosing to promote the book. They have given this book from a first-time author such as myself, a lot more visibility than a publishing house might have.

9. How are you promoting the book?

There has been a lot of interest in hearing about the book. I am in the process of writing articles in various publications, also being interviewed on some platforms. I have made a few presentations that I have put into a YouTube channel called “The Puranic Universe” and have started a blog with the same name. We are exploring if the book can be turned into content for young adults. So quite a few activities to get readers to be aware of the book and engage with the Puranas.

10. What should the readers of From the Beginning of time expect from you next?

I have received a lot of favorable feedback about the book but would like to hear more from readers. One option is to expand the book with some additional content.

11. Who are your favorite authors?

For the past eight years, from when I started to read the Matsya Purana, I have not read a ‘book’ that is not a Purana! That should explain my level of fascination with these texts. Before this, I have read fiction by Amish Tripathi and the books by Ramesh Menon on the Puranas. The book India by John Keay was an excellent read as well.

12. Thank you for your time. Do you have a concluding message for MyIndreaders?

The Puranas are encyclopedic and a vast source of knowledge. Let us re-engage with these texts and unlock the treasures they offer for the benefit of all humankind

As published by MyIndMakers on 10 Nov. 2020.

MyInd Interview with Ganesh Swaminathan, author of the book, "From the Beginning of Time"

Available on Amazon India at bit.ly/AuthorGanesh

Currently also listed on Amazon in the US, UK, Germany, Singapore and Australia.

November 8, 2020

Modern science and the Puranic texts

The Sanskrit word purana means ancient. To associate the word with anything modern is, obviously, incongruous. To suggest that the ancient Hindu texts, the Puranas, have anything in common with modern science seems incredible. And yet, that is what a nuanced reading of the Puranas suggests.

The Puranas are one of the three widely known sets of texts in the Hindu faith, along with the Vedas and the Itihasas. Vedic hymns are recited at the significant events in such as naming, marriage and others. The Itihasas are considered history, a record of what happened. The authors of the two Itihasas, Maharishi Vyasa and Valmiki, were not just alive during the time of the epics but were themselves a part of the narrative. The Itihasas have been translated, abridged, widely read and analyzed. The Puranas, however, have not attracted as much attention. For the most part, they have been mined for their stories and their religious and cultural symbolism.

My reading of the Puranic texts began with the Matsya Purana. I wasn’t sure of what to expect, probably a collection of stories about the various divinities. The Matsya Purana turned out to be of a text of great sophistication and kept me so engrossed that I went on to read the Shiva and the Bhagavata Puranas.

It was hard to find the translations of the other Puranas, so I had to download and print scanned PDFs of old publications to continue my journey. As I read on, it became apparent that the Puranas were more than just a collection of charming stories. I have had a fascination with the space sciences and cosmology since my days at school. The resonance of these stories with current science was becoming increasingly difficult to explain away as just happenstance.

A significant set of stories in the Puranic texts relates to the sun. The life cycle of a star such as our sun, as understood by science, consists of five stages. They are birth, wild youth (yes, even stars do have them), the current mature stage, the Red Giant stage and finally, death as a White Dwarf. The first two stages are described allegorically, through stories. The story of the birth is that of the Sun God Martanda, born of Sage Kasyapa and Aditi. The juvenile stage of the star and its subsequent maturity are appropriately described through the marriage of the Sun God, here named Vivasvan, with Samjna. Each of these can be read as charming tales, but the details presented and our current knowledge of the sun’s life cycle make the allegory obvious.

The last two stages of the Red Giant and the White Dwarf are straight out descriptions in the Puranas. The implications of a Red Giant sun for our planet is currently an area of investigation for science. For this to be discussed in eye-watering detail in a text of this antiquity is staggering.

Let us take the example of the Red Giant stage of the sun. It is the scientific perspective that the sun will enter this stage in about 5 billion years and could grow up to 100 times its current size. Current models suggest that the sun’s orb is likely to envelop Mercury and Venus and come close to the earth, making the planet earth extremely hot. The adjacent image (source: phys.org) is an artist’s impression of the Red Giant sun close to the planet.

An artist’s impression of the Earth near a Red Giant Sun (Source: Wikipedia)

An artist’s impression of the Earth near a Red Giant Sun (Source: Wikipedia)This Puranas terms the sun in this stage as the Samvartakaditya, the sun that destroys the world. The Brahmanda Purana’s description of the sun heating the earth starts with the planet experiencing a severe drought. As a result of this, most of the animals and plants die and are turned to dust.

133–136a. On account of it, only those living beings deficient in strength or having very little potentiality on the surface of the earth become dissolved and get mingled with the dust.

As this sun grows in size, it gets closer to the earth, further heating it, the water in the oceans turns to vapor.

136b -140. Seven rays of the sun that blazes in the sky sucking up water, drink water from the great ocean.

Heated by the sun, the earth slowly becomes a blazing red ball, similar to the artist’s impression in the image above.

157b-159. Getting the fiery splendour transmitted to it, the entire universe slowly assumes the form of a huge block of iron and shines thus.

Brahmanda Purana, Book III, Section iv, Ch. 1

The verses above are a sample from an extensive passage in the Brahmanda Purana. The level of detail in the text is astounding.

Following this, we have the sun collapsing to become a White Dwarf. It leads to torrential rains and the submergence of the planet in Ekarnava, the one vast ocean.

The Puranas similarly have many references to the moon. Many of us may recall the story of the moon, having 27 wives.

21. Daksa, the son of Pracetas, gave in marriage to the Moon the twenty-seven Daksayanis (daughters of Daksa) of great holy rites, whom they know as the stars.

Brahmanda Purana, Book II, Section iii, Ch. 65

The path of the moon’s orbit around the earth is divided into 27 equal parts in the Indian Nakshatra system. The lunar month is 27.3 days, and 27 is the nearest whole number. The moon is seen every dawn next to a new nakshatra. This is taken to mean it had spent the night with that nakshatra, with that wife! Hence the story of the moon having 27 wives, the 27 nakshatra.

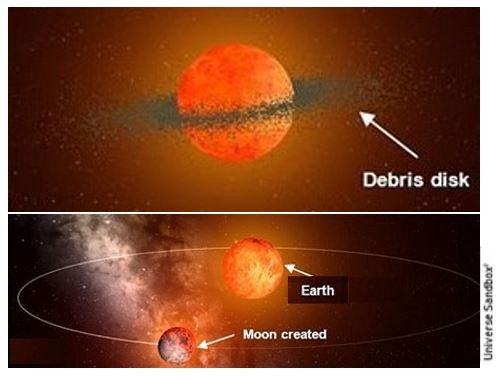

The scientific view is that the moon originated from the impact of a smaller Mars-sized planet with the earth. This is called the Giant Impact hypothesis. The cataclysmic collision resulted in a large cloud of debris that orbited the earth. Over time, the dust in this cloud clumped together to form the moon. The adjacent illustrations (source: OpenLearn) are a simulation of the last two stages of this event. This is a field of study that is not considered settled, and this hypothesis has a few variants.

An illustration of the Moon being created from the debris disk of the collision (Source: OpenLearn)

An illustration of the Moon being created from the debris disk of the collision (Source: OpenLearn)In this Puranic story, the moon spends all his time with Rohini, ignoring his other 26 wives, Rohini’s sisters. Daksha, the moon’s father-in-law, curses him to waste away by consumption, for not treating all his daughters equally!

A moon that is always in one place in the sky (close to one star) is a moon headed towards the earth. The debris of the resulting collision spreads in a region of space called the Kshiroda Sagara. This region of space is ‘churned’ to make the moon manifest again. This is a complex story and is explained in some detail in a new book.

Titled ‘From the Beginning of Time,’ the book examines the universe of the Puranas in five parts. These are the sun, the moon, the earth, the Bhumandala and the loka (Deva and Patala loka). The narrative for each part is tested for two attributes: their ability to be as close to the scientific perspective as the interpretation of the texts will allow and to stand as a coherent and plausible sequence of events. A third test is to see if these five narratives work well with each other.

The descriptions of the five parts create a collage of the Puranic universe. A chapter on the summing-up draws upon the story of the Ganga to tie these stories and demonstrate that they are not just disparate accounts. The Ganga is not just the river that is much revered in India. The story of its descent to the earth is really the story of the extraterrestrial origin of the earth’s waters, as understood by modern science. The models describing the early earth suggest it would have been too hot to hold liquid water on its surface.

The Ganga is described in the Bhagavata Purana as descending from the heavens and covering the Brahmanda.

1. Through that opening, rushed in the stream of waters, covering externally the cosmic egg.

Bhagavata Purana, Book V, Ch. 17

The Puranas also have the well-known story of the Ganga being brought down from the heavens as a result of King Bhagirath’s penance. The waters are held in an intermediate region, the “matted locks” of Shiva, who then releases the waters so they can safely reach the earth.

As mentioned earlier, the scientific perspective is that the earth’s waters have extraterrestrial origins. In light of this, the Herschel Space Observatory, a project of the European Space Agency, has been chartered to track down the sources of water in space. Here is a note from its website:

In fact, water has been observed in celestial objects as diverse as planets, moons, stars, star-forming clouds, and even beyond our Milky Way, in the stellar cradles of other galaxies.

ESA, Herschel, The cosmic water trail uncovered by Herschel, Sep. 2019

There are two regions of space surrounding the earth with water (ice), the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud. The Kuiper Belt has objects that are frozen volatiles, such as ammonia, methane and water. The illustration below (source: Wikipedia) shows the Kuiper Belt objects locations relative to the planets in our solar system.

The Kuiper belt (green), in the Solar System’s outskirts (Source: Wikipedia)

The Kuiper belt (green), in the Solar System’s outskirts (Source: Wikipedia)A class of comets originates from the Kuiper Belt headed towards the sun. When some of these enter the earth’s atmosphere, the heat of entry vaporizes the water, which later falls to the earth as rain. The Oort Cloud, which is much further out, is hypothesized to have a different class of comets, also containing water. And so, we have water being held in an intermediate region of space surrounding the earth and safely reaching our planet in the form of comets, as described in the Puranas.

The book brings a fresh perspective to the Puranic texts, looking at them through the lens of modern science. The Puranic narratives often align with current science, but there are also a few divergences. That said, science itself is not static, and the book makes the case that if this exploration had been carried out about 200 years ago, most of what we know today would not have been available. The stories would all have been seen as flights of a poet’s fantasy.

The use of science as a framework for reading the Puranic texts will, hopefully, provide a heft of rationality and steer us away from some of the more frivolous interpretations. I use the word ‘framework,’ as I do not profess to be an expert in all the cosmological sciences. A framework allows those with expertise in the various sciences, but little exposure to the Puranas, to engage and contribute to this conversation. As a result of this process, the framework will itself likely evolve, but we would be well on our way to uncover the knowledge of the Puranic texts for the benefit of all humankind.

As published in Manushi on Oct. 12, 2020;