Judith Hale Everett's Blog

April 19, 2023

Confessions of a Georgette Heyer Addict

I’m not actually certain when I read my first Georgette Heyer. I know it was her anthology of Regency short stories, Pistols for Two, because I vividly remembered both the cover and several of the plot lines decades later, but I must have read it before the age of twelve, because the memories are inseparably connected to a specific armchair that didn’t survive much past that. I also entered a tomboy phase about then that precluded my even entertaining the thought of such drivel as historical romance.

But inevitably my tomboy phase ended and I swung to the other side of the pendulum, yearning for romance. In my inexperience, I unwisely pilfered an older sister’s hoard of Harlequins, quickly becoming jaded to the genre when I realized I do not appreciate sex or inuendo. After that, I turned up my nose at anything that looked suggestive—including, unfortunately, Georgette Heyer, because her ‘80s covers were just as bad as all the rest. (Witness this horrific example, April Lady, 1982)

But I had been bitten by the Regency bug, so I found myself drawn to Jane Austen and Baroness Orczy, and it wasn’t long before I fell in love with the time period, the language, the manners, the fashions, and the restrained but passionate emotions, and I wanted more. Occasionally, I’d try another modern historical romance, but most of these disappointed me because the very restraint I thought made everything so compelling and exciting in Austen’s work was abandoned, and they seemed more like modern romances dressed up in Regency period costumes.

Then finally, one summer when I was in my forties, another older sister came to visit and brought a box of old Heyers—with the awful covers—and when she offered one to me, I politely and righteously refused. But she knew better, and instantly set about disabusing me of my misapprehensions, pulling out the very edition of Pistols for Two that I remembered from my youth as proof. I was amazed to have been so terribly wrong for so hideously long, and agreed to give The Convenient Marriage a try. Needless to say, after two chapters I was hooked.

Deeply shocked that my life-long prejudice had kept me from such joy, I proceeded to read every Heyer I could get my hands on, quickly accumulating my own collection. How could I not? Here was finally a writer who incorporated everything I loved about classic romance, with just a touch of modern readability and humor—and she had thirty-some-odd books!

As an English language geek, I can’t get enough of the language in Heyer’s stories. It is so deliciously smooth and yet exact, something that modern language often lacks. I know Heyer’s language is considered by some scholars to be Edwardian rather than Regency, but what I’ve come to recognize as an American studying British works is that the written language didn’t evolve very much at all during the hundred years between Austen and Heyer. Just look at the Brontës and Dickens—their language is so similar to Austen’s that many readers continually confuse the Victorian era with the Regency. There are also other Regency writers who have a more casual writing style, like Fanny Burney, whose language is closer to Heyer’s. All in all, I feel that Heyer beautifully preserved the precision and feel of earlier language in a slightly more relatable form to modern readers.

I’m also in awe of Heyer’s humor. It is so unexpected and yet delightfully apropos. For an author who has been accused of racism and class prejudice, she certainly poked fun at the English upper classes a lot, exposing their faults and excesses and laughing at their self-consequence with abandon. No one was safe from her needle wit, from the Patronesses of Almack’s to the Duke of Wellington to the Prince Regent himself. She didn’t spare the lower classes either, but more often showed them in a sympathetic or superior light, emphasizing their wisdom as opposed to that of their “betters.”

Which brings me to her remarkable characters. She was as adept a student of human nature as classic authors, drawing her characters with a balance of virtues and flaws that imbued them with realism and life. No character is simply a side character—they all have dimension and history. They’re just so delightfully human that we want to take them to our bosoms as family. I think I’ve read The Corinthian and The Convenient Marriage ten times each, just to savor every moment with them. Even her villains are realistic, their fatal flaws stemming from reasonable causes and believable backgrounds. But many of her villains are multi-faceted, despicable and yet possessing redeemable qualities that cry out to be explored. Jack from Cotillion, for example, might just find himself in one of my books someday as a rake compelled by true love to reform.

While I don’t claim to have mastered Georgette Heyer’s style—because who ever could—I certainly write in homage to her. She, along with Jane Austen, instilled in me an insatiable love of the Regency, an appreciation for subtle but witty humor, and a fascination with deep characters and involved plots. In my humble opinion, there is no better style than theirs to emulate in the genre of Regency romance.

September 5, 2022

Anatomy of a Regency Inquest

During the Regency, the British had a constitutional dislike of police, believing that an organized police force would undermine the ideals of the kingdom. So when there was a crime, they had to rely on local magistrates and volunteer constables to take care of things. Occasionally, people would enlist the aid of the Bow Street Runners in London (that’s a post for another day). But when the crime involved a suspicious death, the coroner was called in to decide if someone was responsible and if that person deserved to pay for the crime.

The title “coroner” comes from the Latin “coronus,” meaning crown; from the Middle Ages, the British coroner was a representative of the crown in cases of criminal justice. The office evolved over, and by the Regency, the coroner was almost exclusively responsible for determining if murder had been committed, as well as the identity and the level of culpability of the guilty party. To do this, he called an inquest, which was a very loosely organized preliminary investigation to gather and analyze evidence.

The inquest generally took place within forty-eight hours of the death, and jurors were chosen from among the nobility, gentry, and principle inhabitants of the area where it occurred. The first order of business was to view the body, which was supposed to have been untouched since the death; hence, all the jurors would troop up to the bedroom or into the backroom or over the fields to see the dead person and make what they could of it.

Then the group adjourned to somewhere close by—a room in the house or the local inn—to decide who should be called in to give a deposition. Anyone with any knowledge of the situation was summoned by letter to give evidence, and could be heavily fined if they refused to cooperate. Generally, people were happy to comply, because it was their chance to discover more details of the crime as most inquests were not public.

If it was determined that someone was responsible for the death, these suspects were only detained in jail if they seemed to be dangerous or likely to flee, instead being told not to leave the country until the inquest was over. Unlike today, jurors were not forbidden from speaking to any of the witnesses (including the suspect) before the inquest. The only time the jury could not speak to anyone outside the court was after all the evidence was heard and they were deliberating over their decision.

If the inquest found the suspect guilty, he would be ordered to appear for trial at the assizes, where his final fate would be determined. Because the assizes came around only every couple of months and only in principle towns, the suspect was not necessarily detained, but expected to stay in the area until the trial. If he/she did not present him/herself at the appointed place and time, they could be seized by soldiers and fined or transported (depending on the situation).

At the town where the assizes were being held, the suspect would be held in jail until their hearing, and given the opportunity to make final arrangements in case they were found guilty and sentenced to death. The decision of the judge at the assizes was final, and could range from acquittal to transportation to death to prison, depending on the situation and, unfortunately, the status of the prisoner. Nobility and gentry tended to get better treatment, while commoners more often than not got the short end of the stick.

This process was a way to keep the assizes from becoming too overwhelmed by cases that could be resolved in the local community. Because the inquest was run by people who better knew the circumstances and the people involved in each case, there was a better chance of justice being served than by referring every suspicious death to a travelling judge in a far off town.

Sources:Impey, John. The practice of the office of sheriff; also the practice of the office of coroner. W. Clarke and Sons. 1817.

https://www.londonlives.org/static/IC...

August 5, 2022

Cerebral Palsy in the Regency

Just as the Industrial Revolution brought rapid changes during the Regency era, medical knowledge made significant improvements as well. Unfortunately, technology was slower to evolve, so there were still many mistaken beliefs held by medical doctors and other providers simply from an inability to probe further. Without imaging or electrical testing techniques, little was known about the nervous system, for example, and how it impacted various diseases.

Therefore, before 1837, cerebral palsy was lumped with various other conditions in a general diagnosis of “deformity.” A more specialized doctor may diagnose a patient with “spastic paresis” (involuntary jerking of muscles) or paralysis, with or without “idiocy” or “imbecility.” Imbecility at the time meant a minor mental handicap, while idiocy was a permanent, irreversible state of mental incapacity without intervals of proper function (as opposed to mental illness).

These definitions sound harsh to us today, but because doctors of the time had very little knowledge of how the brain worked they could only identify issues from how a person appeared or acted. Children with intellectual disability or quadriplegia were often sent to asylums, where there supposedly were more resources for proper care. But these facilities varied widely in quality of care, depending on funding and the involvement of trustees, so outcomes were not always positive.

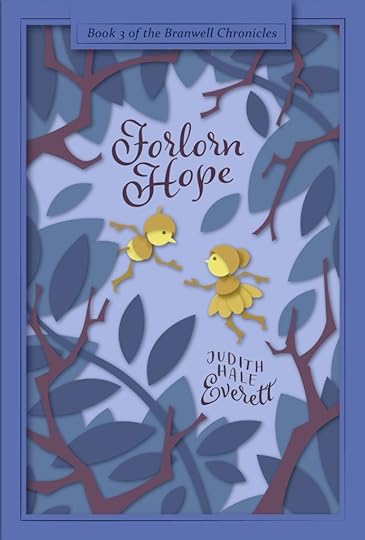

Children with only motor dysfunction, like Mr. Noyce in my book Forlorn Hope, could more easily be cared for at home and had a good prognosis for health and happiness. In the 1830’s, Dr. John Little, himself affected by neural disease, made the first focused study of cerebral palsy, though he connected neural defects with injuries or lack of oxygen at birth. But he got members of the medical field thinking, and due to his pioneering work, what we know as cerebral palsy was termed “Little’s Disease” until 1887, when Dr. William Osler—the next “big player” in the development of treatment—coined the term we use today.

Sources:Panteliadis C.P., Vassilyadi P. “Cerebral Palsy: A Historical Review.” Cerebral Palsy. Springer, Cham. 2018.

May 3, 2022

A Reflection on Pre-Colonialism

When we think of the British in India, most of us will instantly envision colonial officers and their memsahibs lording it over the natives. This supremacist attitude, however, did not always the reign in England, but was the result of a long and complicated progression.

England had a presence in India from the year 1600, when the East India Company was formed to advance trade in India and Asia. In accordance with trade practice at the time, the company colonized as it went, seizing control of strategic parts of India and other countries along the trade routes to protect British interests.

To support their activities, the EIC brought in hundreds of Englishmen to act as officers and soldiers in a paid army that ensured that the balance of power—and therefore trade—would remain in British hands. These men were generally unmarried, and after a long day of keeping the peace, they had only a barracks full of other grumpy men to come home to.

This situation led to drunkenness, brawls, bawdy parties, and an influx of fatherless children of unwed Indian mothers around the camps. To combat the problem, the EIC first tried to import English women into India, with the idea that they would marry and settle down the men, with little success. Single women of high enough character to tempt the British soldiers in India simply were not desperate enough to leave their English lives and travel into an unknown region to be married to whatever man would have them.

So the EIC encouraged their men to marry Indian women instead. Many of them had already done so, some setting up harems after the manner of Indian sahibs. This practice did settle things down, and generations of Anglo-Indians sprang up as ready replacements for their fathers within the ranks of the EIC. Several high-ranking officers, most of them of the English nobility, took Indian noblewomen as wives, and a few even began to dress and act like Indian Mughals.

Lieutenant-Colonel James Achilles Kirkpatrick in Mughal dress

Lieutenant-Colonel James Achilles Kirkpatrick in Mughal dressHowever, by the late 1700’s, the political tensions between reigning Indian factions and the British presence in India had come to such a height that the EIC began to question the loyalty of its part-Indian dependents. They felt they could not trust anyone of Indian descent to protect the interests of the EIC when they clashed with the rights of Indians. So they did what any reasonable totalitarian body would do: they turned their back on them.

Thus began the slide from integration to segregation, starting with changes in policy to forbid the placement within the company of any candidate who was not of at least 3/4 English blood. These changes were retroactive, and resulted in the summary dismissal of several Anglo-Indian children of former and present full-English officers and soldiers. Only a few extremely lucky Anglo-Indian employees survived this purge, and only with the help of high-ranking (and rich) supporters.

Those who did not were left to fend for themselves, which was increasingly difficult because they were also mistrusted by their Indian neighbors. Understandably, as the EIC asserted its authority in India, all things English became hateful to those Indians opposed to their rule, and Anglo-Indian persons found themselves unable to exist in either sphere.

Meanwhile, back in England…

Thanks to the difficulty of travel (steamships were not in use until 1830, and the fastest travel time from England to India was four months one way), communications from the EIC to its English offices were slow and tedious. Policy changes came to England with very little context, and free of the immediate pressures that surrounded their counterparts in India, the London officers of the EIC often scratched their heads over them or disagreed with them outright. This caused a back-and-forth conversation that was much like that of tin cans on a string: much misinterpretation and very little clarity.

But the English imagination had been ignited by India, and English people—for the most part oblivious to the increasing tensions that reverberated between cultures in that far-away sub-continent—embraced anything Indian with enthusiasm. Among the elite, especially, there was a fascination with Indian style in home decoration, and even the Prince Regent remodeled the Royal Pavilion in Brighton to resemble an Indian palace.

The Royal Pavilion, Brighton

The Royal Pavilion, BrightonRefugees, generally of the Mughal (ruling) class in India, came to England to seek redress when treated unfairly by the EIC, and were met with great favor and clemency, many winning their cases and returning to India with cash awards for their trouble. Some opted to remain in England and enjoyed the life of a celebrity for some time.

Thus, by the Regency (1810-1820), there came an influx of Anglo-Indian children to England, sent to make their way in a gentler world. As generally only officers and other high-ranking officials in the EIC could afford such an arrangement, these children were of the upper class, and therefore already had an advantage in society. Some lower-class children, and their Indian mothers, however, were also successfully integrated into English society during this time.

This tolerant period, unfortunately, was fairly short-lived, as the advent of steamships and the telegraph accelerated communication—and thus, fellow-feeling—between the English in the two countries. By the 1830’s, strong prejudices against Indians and Anglo-Indians began to develop in England, culminating in the typical colonialist attitudes of the Victorian era.

Sourceshttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_India_Company

Dalrymple, William. White Mughals. Harper Press 2012.

Fisher, Michael Herbert. Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Travellers and Settlers in Britain, 1600-1857. Permanent Black, 2006.

March 8, 2022

Forlorn Hope: Coming March 14!

Cover art by raeallenart.com

Cover art by raeallenart.comCaptain Geoffrey Mantell has returned after years on the Peninsula to find a wife, but none of the society misses he meets quite grasp what he’s been through as a soldier. Only Miss Emily Chandry, the unfortunate daughter of the miser next door, seems to understand him completely, but though the hours they spend together are the happiest of his life, he does not think of her as more than his childhood playfellow.

Only after his regiment is recalled to the Continent to fight the horrific battle of Waterloo does Geoffrey at last see the truth, realizing that Emily is the only one for him. He comes back to England after the war to claim her hand, but he is too late—Emily is lost to him, the wife of a stranger who does not seem to care for more than her social connections.

Reeling from this turn of events, Geoffrey must try to move on, but Emily’s situation will continue to haunt him until a mystery surrounding her late father opens up opportunities to change her fate, and he can only hope that his love for her will not drive him too far.

Don’t miss this third installment of the Branwell Chronicles, coming to Amazon March 14 and to all other distributors March 28!

For a sneak peek of Forlorn Hope, click here.

January 10, 2022

A First of Its Kind: the Waterloo Medal

Most people have heard of the Battle of Waterloo. It was the culminating battle of an eleven-year conflict with France which, under the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte, was attempting the subjugation of all Europe, and even the world. The series of wars were split into several periods, including the Wars of (various) Coalitions, and—those that happened during the reign of the Prince Regent, and that most historical romance fans are familiar with—the Peninsular War (which took place in Spain, France, and Portugal during 1809-1814), and The Hundred Days (which took place after the (supposed) defeat of Napoleon and his subsequent escape from exile and recommencement of hostilities in France and Belgium, and was ended by the sister battles of Quatre Bras, Ligny, and Waterloo in June 1815).

The eleven year-long struggle to free Europe of Napoleon’s rule had been so overwhelming that his final defeat at Waterloo—many believed—marked one of the greatest victories of all time. England had played a decisive role in all the battles, but it was General Arthur Wellesley, who was made Duke of Wellington for his contributions during the Peninsular War, who is associated with ending the war, as he led British, Irish, German, and Dutch troops at the Battle of Waterloo. Between this Anglo-Allied army, the Prussians, and the Austrians, Napoleon was defeated once and for all, and died six years after re-entering exile, this time on the distant island of Saint Helena.

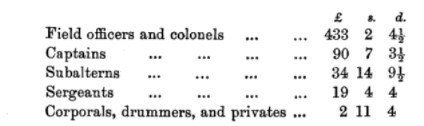

Up to this point, England had issued medals for incidents of extreme bravery or excellence in battle, but had not considered a mass award for specific engagements, as other countries had done. The prevailing belief was that men who fought in the Army did so out of honor, and thus had only done their duty, which had its own reward. Because this battle was so hard-won and the victory so long awaited, however, Parliament felt the need to celebrate it and to give a more tangible thanks to those who had participated. The Duke of Wellington agreed, and added his voice to those urging the Prince Regent to mark such a historic victory in a historic way. Prinny, needing little encouragement to put his stamp on history, decreed that all those who had fought at Waterloo and the surrounding battles were to receive a reward in the form of a medal (boasting his own profile) and a monetary prize equal to 2 years’ military pay according to rank.

Waterloo Meda

Waterloo MedaThis recognition was gladly received, but not everyone thought it was appropriate. For one, it effectively dismissed the contributions of all those who had fought in the ten years leading up to Waterloo, but who had retired or were not able to fight in the Battle of Waterloo. This neglect by the government increased the strife and irritation already prevailing among the lower classes in England because of the high costs—emotional and financial—of the war. The Corn Laws, ongoing enclosure of common farmland, coin shortages, and the upheaval of the Industrial Revolution all took their toll on an already stressed economy, and Britain, though set to enjoy fifty years of peace from the outside world, would see little peace within its borders.

Those who received the Waterloo Medal, however, were glad for it, as they were for the extra pay, though the grades varied hugely (see below table). The Duke of Wellington, whose name was inscribed on one side of the medal, enjoyed a most “flaming character,” as Jane Austen would say, and was almost deified by all walks of social life. The Prince Regent, however, though his profile and name graced the opposite side of the medal, would continue to earn such sobriquets as “Fat Prinny,” “Fum the Fourth,” “the Prince of Pleasure,” and “the Prince of Whales,” no matter how many medals he inaugurated.

Reward pay grades for recipients of the Waterloo Medal, Goff 72Resources

Reward pay grades for recipients of the Waterloo Medal, Goff 72Resourceshttps://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/medals/waterloo-medal

https://www.warwickandwarwick.com/news/guides/an-in-depth-guide-to-waterloo-medals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waterloo_Medal

https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1831/

Historical Records of the 91st Argyllshire Highlanders: Now the 1st Battalion Princess Louise’s Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Containing an Account of the Formation of the Regiment in 1794, and of Its Subsequent Services to 1881, Gerald Lionel Joseph Goff · 1891

January 3, 2022

Entails: the Real Deal

“About a month ago I received this letter…It is from my cousin, Mr. Collins, who, when I am dead, may turn you all out of this house as soon as he pleases.”

“Oh! my dear,” cried his wife, “I cannot bear to hear that mentioned. Pray do not talk of that odious man. I do think it is the hardest thing in the world, that your estate should be entailed away from your own children; and I am sure, if I had been you, I should have tried long ago to do something or other about it.”

Jane and Elizabeth attempted to explain to her the nature of an entail. They had often attempted it before, but it was a subject on which Mrs. Bennet was beyond the reach of reason.

Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen p. 207

by Hugh Thompson

by Hugh ThompsonThe trope of an entail to complicate matters of heredity and fortune is well known to all readers of historical fiction. Even Jane Austen used it in Pride and Prejudice to explain why “the business of (Mrs. Bennet’s) life was to get her daughters married” (p.180). Unlike Mrs. Bennet, however, most of us know what an entail is, and generally how it works, but when it comes to how one can be broken, there seems to be a lot of confusion.

An entail, the idea of which had originated in the 1400s, was created in the first place to keep the property of a family intact—to prohibit its being parceled up each generation until there was hardly anything left worth passing on. By securing the entire property to one child—usually the eldest son—the family name was guaranteed the dignity of landed property in perpetuity. However, sometimes situations occurred to make the entail undesirable—as in the case of the Bennets who, lacking a son, would happily have split up the property amongst their five daughters rather than lose it all to a man “nobody cared anything about” (p. 207). In this event, it would be desirable to break the entail.

It turns out that breaking an entail was not doing away with it, but recreating it. An entail was in force for three generations: the present owner, to his heir, to his heir; then it would legally end. If the middle generation wished to change things, he—generally the son, once he came of age—would have to prove that the entail was illegal in some way. But since entails were almost always legally sound, there was no way to make a case.

But the British gentry were resourceful! They came up with a wild yet admittedly ingenious solution to thwart the system, which somehow became the accepted mode—and this is why people are so confused about it. The solution was that the present owner and his heir would together engage in a farcical legal battle called a “common recovery” with an imaginary opponent who supposedly had laid a claim to the estate.

I’m totally not kidding. This is a documented process that happened over and over and over, and rather than be blown away by how crazy it was, people just accepted it as the way to get the thing done.

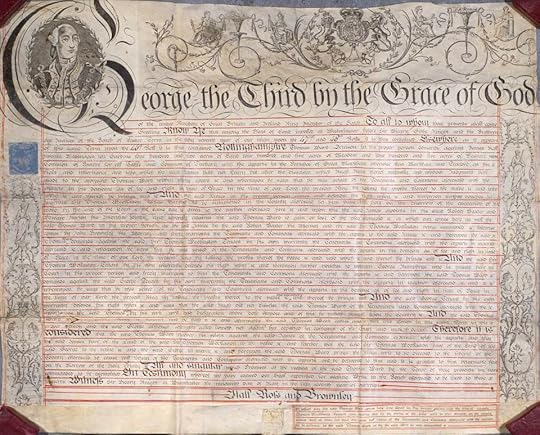

Exemplification of a common recovery of messuages and land in East Markham and Tuxford, Nottinghamshire; 1817 (from resource, below)

Exemplification of a common recovery of messuages and land in East Markham and Tuxford, Nottinghamshire; 1817 (from resource, below)Anyway, with an outside claimant—played by a court clerk or paid actor who often went by the name of, get this, John Doe—the entail would no longer be legal, and thus it would be broken until the claim could be decided. But then the imaginary claimant would conveniently not appear for testimony, and being found in contempt of court, would lose his claim to the estate. Now the property reverted back to the present owner, but the entail was still broken, so the current owner of the property, with the collusion of his heir, could recreate the entail, making adjustments such as selling off land in order to free up money, and the new entail would then carry to the heir’s second generation.

This slick little process worked beautifully, but could only be accomplished with the agreement of the heir, who must be of age. This generally was not a problem if the heir was the son, who would have a vested interest in the well-being of his family. But if the heir was a cousin or someone farther off in the family tree, there was little to no hope they would sacrifice their inheritance for the welfare of their relations, pathetic though their situation at his inheriting may be. This was why it was not even suggested in Pride and Prejudice that Mr. Collins would collude in breaking the entail because, absurd as he was, he was very much aware of the value of the Longbourn estate to himself.

Even if the heir was the son, however, it was quite possible that he would refuse to collude, especially if he had a bad relationship with his father, or knew that breaking the entail would only benefit the present owner and not himself or other members of the family. In my story, Romance of the Ruin, Lord Helden’s father was a neglected only child, and refused to collude with Old Lord Helden because he had no desire to enable his father’s abuse of himself in any way, so the entail carried to his son, where it naturally ended.

Not surprisingly, the British legal system eventually grew tired of this ridiculous circumvention of the law, and finally outlawed entails in 1833.

Resources:https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/common%20recovery

September 24, 2021

The Senses and Sensibility

The craze for Gothic romance went hand in hand with the decades-long craze for sensibility—a deep response to emotion, whether in oneself or in one’s environment. Sensibility bore a strong resemblance to what we now term drama—or the tendency to overreact to or overdramatize anything and everything. Hence Marianne Dashwood’s poetic reaction to fallen leaves in Sense and Sensibility, and Lenora Breckinridge’s fascination with dramatic heroism in Romance of the Ruin.

Romances such as those penned by Mrs. Radcliffe were filled with sensibility: in Udolfo, the book that captivates Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey, the heroine is constantly swooning from deep emotion, and pages upon pages are dedicated to sweeping descriptions of the Italian countryside entirely calculated to stimulate the emotions. The key here is extremes: think a 1930’s black and white silent movie. All emotion is intense, whether it be fear or courage or love or greed. It is no wonder that Catherine Morland’s imagination, steeped in such ideas, should succumb to the terrible conclusions it did when she reached the Abbey.

But sensibility was not restricted to Gothic romances. The Romantic poets, Wordsworth, Byron, Coleridge, Keats, etc., employed verse that either spoke to the sensibilities of their readers or emanated from their own sensibility, and the Romantic painters sought to evoke intense emotion in their works.

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, John ConstableThere was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight

To me did seem

Appareled in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream.

Ode on Intimations of Immortality, William Wordsworth

An Enigma, Sir William Quiller Orchardson

An Enigma, Sir William Quiller OrchardsonWhen we two parted

In silence and tears,

Half broken-hearted

To sever for years,

Pale grew thy cheek and cold,

Colder thy kiss;

Truly that hour foretold

Sorrow to this.

When We Two Parted, George Gordon, Lord Byron

The romantic force for sensibility in the Regency period was extremely strong, yet there were some who were not entirely swept away by it. Jane Austen was influenced by the Romantic poets and read all of Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, but she managed to keep her head, much like her character Elinor in Sense and Sensibility. That book in itself may be called proof of Austen’s attitude toward the prevailing rage, at least as it affected people in real life. Northanger Abbey is another reaction to sensibility, but is more satirical, and aimed toward the sensibility engendered by Gothic romance.

Overall, an understanding of sensibility should help readers of Regency fiction—both contemporary and modern—to understand why there was so much swooning and palpitations and generally intense emotion, and to appreciate that there has always been drama, in one form or other, in the world of romance.

September 20, 2021

Never Mind Your Daily Bread

Though I love the Regency era, it was not all loveliness and good manners. There was plenty of greed and oppression and general evil happening then as in any era, and it sometimes boggles the mind.

The Napoleonic Wars, which began in 1807 and ended in 1815 at Waterloo, was an expensive enterprise paid for primarily by raised taxes and tariffs on various imports. British blockades of French trade ships ensured that profits stayed in England and that British markets did not support Bonaparte’s bid for world domination. This also meant that the British people were able to purchase only what was readily available within their country, and at the prices required. These trade restrictions greatly enriched already wealthy landowners, whose farms supplied “corn” (all types of grain) to the entire country.

A political cartoon of the time

A political cartoon of the timeAfter the war, the landowners did not wish to part with their plump wartime profits, so Parliament, which was made up of nobility and landed gentry–or all the wealthy landowners–imposed the Corn Laws, which prohibited the import of foreign grains unless the price of British grain rose to a specified point. While this strategy satisfied the wealthy landowners, the middle and working classes were terribly oppressed by it, because their “daily bread” had become so expensive that they often despaired of being able to afford it.

Unsurprisingly, the Corn Laws greatly depressed the economy, because the majority of the population stopped buying manufactured goods so they could afford to feed themselves. Factories were forced to turn off workers because demand was so low, which swelled the ranks of those “breadwinners” unable to provide for their families. Their sufferings went unheeded by the government, however, because they did not have a voice in government. Even the merchant class, whose factories and trade were struggling under the current laws, had no recourse, because only those who owned land were allowed a vote in Parliament.

Corn riots

Corn riotsGeneral unrest quickly gave way to riots and other violence, but though legislation to revise or repeal the Corn Laws was more than once brought before Parliament, it continually failed to pass. At last, the Reform Act of 1832 extended voting rights to the merchant class, which brought hope to the suffering poor.

Change was not imminent, however. A few alterations to the Corn Laws lowered the price required before grain could be imported, but these were so slight that they were essentially ineffective. The Anti-Corn Law League was organized in 1836, made up primarily of members of the merchant class, but it would not be until 1846, a full decade later, that the Corn Laws were finally repealed.

That such a small portion of the population could ignore such widespread suffering, all for the sake of their own greed, is really sickening to me. I take some comfort in the fact that there must have been some landowners with consciences, however, because bills to repeal or reform the Corn Laws were introduced, though they were largely unsuccessful.

Resources:

https://editions.covecollective.org/chronologies/corn-laws-1815

https://www.britainexpress.com/History/victorian/corn-laws.htm

September 10, 2021

The Truth about Romance

The title of Book 2 of the Branwell Chronicles, Romance of the Ruin, is a play on the 1791 Gothic romance by Ann Radcliffe, Romance of the Forest. This title today would evoke ideas of lovers in the woods, secret trysts and dramatic breakups, and perhaps some acts of daring. But the era in which Mrs. Radcliffe was writing defined the word “romance” differently.

A romance in the time of the Regency was a fantastic tale, usually set in the past, where the action was not possible–or at least not probable–in real life (similar to a fairy tale), and where love, if it factored at all, was only a side interest. The word “romance” comes from the Old French word “romanz,” meaning “verse narrative,” and was applied to fireside stories told of knights and magic and chivalry and adventure. The sense of “an adventurous story” persisted through the early 1800’s, with the incorporation of gentlemen rather than knights.

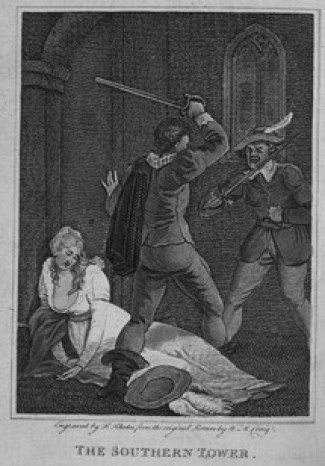

A Gothic romance illustration, probably for a Bluebook

A Gothic romance illustration, probably for a BluebookRomances of the Georgian and Regency era were typically filled with fainting damsels in distress, dastardly villains bent on abduction (but oddly preferring marriage to rape), and downtrodden heroes who ended up the long-lost heir of some rich lord. Gothic romances, like Mrs. Radcliffe’s, added paranormal elements, horror, and suspense to the mix.

These Gothic romances reached the zenith of their popularity during the Regency era. The stories were inhaled by readers of all kinds: young, middle-aged, old, male, female, rich, middle-class. Only those who could not afford a subscription to the lending library were restricted to the Bluebooks–cheap, pamphlet-sized serials of books that appeared one chapter at a time. The lower classes could borrow Bluebooks from the lending library for a penny apiece (these were the precursor to the Penny Dreadfuls of the Victorian Era), or purchase them for sixpence or a shilling. But all classes enjoyed the Bluebooks–there was such a thirst for horror and dread and adventure that an author had to be terrible indeed not to gain an audience in the early 1800’s.

It is perhaps no wonder then that young ladies such as my heroine, Lenora Breckinridge, yearned for adventure and looked for villains behind every bush. The real marvel is that anyone of the time found true love at all, and recognized it as such with so dramatic and fantastic an expectation founded by the craze for Gothic romance.

Resources:

Etymology of “romance,” https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=romance

The Great Courses, The Life and Works of Jane Austen, Devoney Looser

Gothic Bluebooks: the popular thirst for fear and dread, Susan Thomas, https://library.unimelb.edu.au/exhibitions/dark-imaginings/gothicresearch/gothic-bluebooks-the-popular-thirst-for-fear-and-dread