Jason A. Staples's Blog

August 11, 2022

Paul and the Resurrection of Israel to Be Published by Cambridge University Press

It is with great pleasure that I pass along the news that I have signed a contract with Cambridge University Press to publish my book, Paul and the Resurrection of Israel: Jews, Former Gentiles, Israelites, expected to be released in the spring of 2023.

This book represents two decades of work, and I cannot wait to see it in the wild and see how others interact with it. A basic abstract of the project follows:

This study examines how the concept of “Israel” was constructed and contested among Jews, Samaritans, and others in the Second Temple Period (roughly 515 BCE–70 CE), as different sects and groups laid claim to the heritage of biblical Israel and differentiated themselves from others doing the same.

Through exhaustive analysis of early Jewish and Samaritan evidence, the books demonstrate that (contrary to the assumptions of most modern scholarship) the terms “Israelite” and “Jew” were not synonymous in Second Temple Period. Instead, the most common view reflected in early Jewish sources is that the Jews are only a subset of the larger body of Israel, namely the descendants of the southern kingdom of Judah. Samaritans, by contrast, neither called themselves Jews nor were they regarded as such by others, but they did consider themselves Israelites, with different Jewish groups having varying responses to this claim. Moreover, the study demonstrates that the continued distinction between “Jews” and “Israelites” in Jewish literature frequently seems to reflect continuing hopes for a future restoration of reconstituted twelve-tribe Israel including the northern tribes of Israel scattered by the Assyrians in the eighth century BCE.

The project thereby introduces a new model for understanding the relationship between the terms “Israelite” and “Jew,” a problem that has drawn increased attention in recent scholarship. In the process, this study helps contextualize the variety of eschatological views that appear in Jewish literature from the Second Temple Period, correcting several recent scholarly trends in this area.

I am especially pleased that the book will be priced affordably, around $39 per hardback copy.

The post Paul and the Resurrection of Israel to Be Published by Cambridge University Press appeared first on Jason Staples.

April 1, 2022

My Harvard Theological Review Article on the Potter and Clay in Romans 9 Now Available

The post My Harvard Theological Review Article on the Potter and Clay in Romans 9 Now Available appeared first on Jason Staples.

July 8, 2021

The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: First Printing Typos and Errata

This week marks the release of my book, The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: A New Theory of People, Exile, and Israelite Identity.

It’s a great relief to finally have it in the wild after 18 years of working on the larger project of which this is the first portion to be released, and I’m excited to report that it has managed to retain its spot as the #1 new release in Judaism at Amazon through its first week.

Nevertheless, it is next to impossible to eradicate all typos and mistakes from a book, particularly one that was in progress for over a decade. In the interest of scholarly clarity and transparency/accountability, this page will therefore serve as the repository for the typos and errors in the first printing of the book. If you have found any others, please let me know either through a comment on this page or via email and I will add it to the list.

p. 7: In the Grosby block quote, “though” should be “through”

p. 33: Where it says Kuhn “delivered the same lecture,” that is a mistake. The lecture from Nov 9, 1938 was the same lecture (properly cited in footnotes 36 as “Gedankenakrobatik des Talmud”) that he had delivered on Nov 1, 1938 in connection with the Nazi propaganda exhibition “Der ewige Jude” at Munich. At the University of Berlin lecture, he gave his lecture on “Die Judenfrage als weltgeschichtliches Problem,” which was not “the same lecture.” (I somehow mixed this up in the editing/rewriting process. Thanks to Dr. Ulrich Kusche for alerting me to this error.)

p. 52: “is a term” is repeated

p. 64 n. 34; 151 n. 28; 152 n. 34: “Nodet, ‘Building of the Samaritan Temple'” should be “Nodet, ‘Israelites, Samaritans, Temples, Jews'” (my bibliographic software had the wrong short title for Nodet’s chapter, the consequence of duplicating the chapter of an edited volume in the database and changing author/title/page number but not the short title field)

p. 103: “expected be aware” should be “expected to be aware”

p. 205 n. 100: the page range for Freyne’s article “Studying the Jewish Diaspora in Antiquity” should be 1–5, not 1–9

p. 270 “There is, however, there is no indication” should be “There is, however, no indication”

pp. 325–27: “Ps. Sol.” should be “Pss. Sol.”

p. 297: in the block quotation, “ground’s” should be “grounds” (how this one happened is beyond me since I cut and paste such quotes)

I have also discovered that I had apparently not fully reworked my translation of two passages quoted in the DSS chapter that were mostly (but not completely) derived from the Wise/Abegg/Cook translation I used for convenience in the initial stage of writing.

Obviously any errors are mortifying for an author who wants everything to be perfect, but I very much appreciate it when people notify me of mistakes. (The biggest scares in the editing process were when a couple of footnotes had somehow dropped out, resulting in unattributed quotations, but we hopefully caught everything of that nature.) Hopefully this book sells enough that we can get the errors here corrected in a future printing.

[Update: these mistakes have been resolved for the second printing and beyond.]The post The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: First Printing Typos and Errata appeared first on Jason Staples.

The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: Typos and Errata

This week marks the release of my book, The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: A New Theory of People, Exile, and Israelite Identity.

It’s a great relief to finally have it in the wild after 18 years of working on the larger project of which this is the first portion to be released, and I’m excited to report that it has managed to retain its spot as the #1 new release in Judaism at Amazon through its first week.

Nevertheless, it is next to impossible to eradicate all typos and mistakes from a book, particularly one that was in progress for over a decade. In the interest of scholarly clarity and transparency/accountability, this page will therefore serve as the repository for the typos and errors in the first printing of the book. If you have found any others, please let me know either through a comment on this page or via email and I will add it to the list.

p. 33: Where it says Kuhn “delivered the same lecture,” that is a mistake. The lecture from Nov 9, 1938 was the same lecture (properly cited in footnotes 36 as “Gedankenakrobatik des Talmud”) that he had delivered on Nov 1, 1938 in connection with the Nazi propaganda exhibition “Der ewige Jude” at Munich. At the University of Berlin lecture, he gave his lecture on “Die Judenfrage als weltgeschichtliches Problem,” which was not “the same lecture.” (I somehow mixed this up in the editing/rewriting process. Thanks to Dr. Ulrich Kusche for alerting me to this error.)

p. 52: “is a term” is repeated

p. 64 n. 34; 151 n. 28; 152 n. 34: “Nodet, ‘Building of the Samaritan Temple'” should be “Nodet, ‘Israelites, Samaritans, Temples, Jews'” (my bibliographic software had the wrong short title for Nodet’s chapter, the consequence of duplicating the chapter of an edited volume in the database and changing author/title/page number but not the short title field)

p. 205 n. 100: the page range for Freyne’s article “Studying the Jewish Diaspora in Antiquity” should be 1–5, not 1–9

pp. 325–27: “Ps. Sol.” should be “Pss. Sol.”

p. 297: in the block quotation, “ground’s” should be “grounds” (how this one happened is beyond me since I cut and paste such quotes)

Obviously any errors are mortifying for an author who wants everything to be perfect, but I very much appreciate it when people notify me of mistakes. (The biggest scares in the editing process were when a couple of footnotes had somehow dropped out, resulting in unattributed quotations, but we hopefully caught everything of that nature.) Hopefully this book sells enough that we can get the errors here corrected in a future printing.

The post The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: Typos and Errata appeared first on Jason Staples.

September 4, 2020

Article on Potter/Clay Imagery in Romans to Be Published in Harvard Theological Review

I just received word that my article, “Vessels of Wrath and God’s Pathos: Potter/Clay Imagery in Rom 9:19–23” has been accepted for publication in Harvard Theological Review. The abstract is as follows:

Starting from the concept of divine patience in 9:22, this article argues that Paul employs the potter/clay metaphor not (as often interpreted) to defend God’s right to arbitrary choice but rather as an appeal to what Abraham Heschel called divine pathos—the idea that God’s choices are impacted by human actions. The potter/clay imagery in Rom 9:20–23 thus serves to highlight the dynamic and improvisational way the God of Israel interacts with Israel and, by extension, all of creation.

The post Article on Potter/Clay Imagery in Romans to Be Published in Harvard Theological Review appeared first on Jason Staples.

Article on Potter/Clay Imagery in Romans to Be Published in Harvard Theological Review

I just received word that my article, “Vessels of Wrath and God’s Pathos: Potter/Clay Imagery in Rom 9:19–23” has been accepted for publication in Harvard Theological Review. The abstract is as follows:

Starting from the concept of divine patience in 9:22, this article argues that Paul employs the potter/clay metaphor not (as often interpreted) to defend God’s right to arbitrary choice but rather as an appeal to what Abraham Heschel called divine pathos—the idea that God’s choices are impacted by human actions. The potter/clay imagery in Rom 9:20–23 thus serves to highlight the dynamic and improvisational way the God of Israel interacts with Israel and, by extension, all of creation.

The post Article on Potter/Clay Imagery in Romans to Be Published in Harvard Theological Review appeared first on Jason Staples.

April 7, 2020

Bruce Metzger and Plagiarism – Literary Forgeries Edition

Back in the spring of 2008, I took Bart Ehrman’s seminar on “Literary Forgery in the Early Christian Tradition.” At the time, Bart was working toward his book, Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Christian Polemics, which he later popularized into Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Aren’t Who We Think They Are, and the rest of us benefited from his having collected extensive resources on the subject and suffered together through Wolfgang Speyer’s Die literarische Fälschung.

But that’s not the subject for today’s post. The second week of the class was on the Disputed Pauline epistles (or, as Bart prefers, the Deutero-Pauline epistles)—that is, 2 Thessalonians, Colossians, and Ephesians, each of which is thought not to have been written by the historical apostle Paul by a reasonably high percentage of critical scholars. One of the articles we read for the class was from Bart’s Doktorvater (and now my Doktorgroßvater), Bruce Metzger, “Literary Forgeries and Canonical Pseudepigrapha,” JBL 91 (1972): 3–24.

We read this article after going through earlier (19th century) materials on the same subject and were all surprised to find numerous examples of verbatim or near-verbatim agreement between Metzger’s article and Alfred Gudeman’s 1894 chapter on “Literary Frauds among the Greeks.” I’ll list the examples below, with underlining where there is substantive agreement.

On pp. 66–67 of his chapter, Gudeman says the following:

Finally, I draw attention to one other instance of a literary forgery which is of particular interest, because it furnishes the only example, at least the only one that has come under my observation, of a literary fraud perpetrated from a motive of pure malice, it having been designed to blast the reputation of one of the greatest historians of Greece.

Apropos of a statue in Olympia, erected to Anaximenes of Lampsacus, the traveller Pausanias takes occasion to add a few details concerning this man and to give some of the reasons for his being thus honoured. We learn, accordingly, among other things, that Anaximenes was the author of a number of historical works, and that he was the inventor of extemporaneous speeches, whatever that may mean. The statue in question had been erected to him by his grateful fellow-citizens, because he had on one occasion saved the town of Lampsacus from destruction at the hands of the enraged Alexander, by a very clever ruse which he practised upon the great Macedonian. After relating the story, Pausanias continues as follows: This same Anaximenes once played an ingenious but very scurvy trick upon his enemy, the historian Theopompus. Being himself a sophist, and skilled in imitating the style of the sophists, he wrote a book, in which he slandered Athens, Sparta, and Thebes; and then counterfeiting to perfection the diction of the historian, he sent the work to these cities under the latter’s name, in consequence of which all Hellas was intensely exasperated at Theopompus.

Metzger’s article includes the following (pp. 6–7):

Occasionally a literary fraud was perpetrated from the motive of pure malice. A counterpart in antiquity to the modern fabrication in czarist Russia of the scurrilous “Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion” was the attempt of Anaximenes of Lampsacus to blast the reputation of one of his contemporaries, the historian Theopompus of Chios (4th cent. B.c.). According to the account of Pausanias, Anaximenes, being himself a sophist and skilled in imitating the style of sophists, once played a scurvy trick by composing, under the name of his rival Theopompus, bitter invectives against the three chief cities of Greece, Athens, Thebes, and Sparta. He then sent a copy of the slanderous work to each of these cities, with the result that the unfortunate historian was henceforth unable to appear in any part of the peninsula.

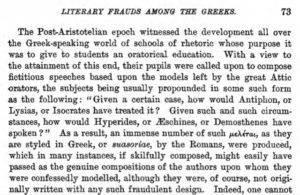

These are relatively minor, and if this was the extent of the verbatim agreements, we’d probably not have thought much of it. But there’s more later in the piece. On p. 73, Gudeman says:

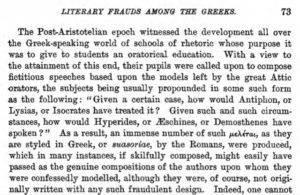

Gudeman’s original version

The Post-Aristotelian epoch witnessed the development all over the Greek-speaking world of schools of rhetoric whose purpose it was to give to students an oratorical education. With a view to the attainment of this end, their pupils were called upon to compose fictitious speeches based upon the models left by the great Attic orators, the subjects being usually propounded in some such form as the following: “ Given a certain case, how would Antiphon, or Lysias, or Isocrates have treated it? Given such and such circumstances, how would Hyperides, or Aeschines, or Demosthenes have spoken?” As a result, an immense number of such μελέται, as they are styled in Greek, or suasoriae, by the Romans, were produced, which in many instances, if skilfully composed, might easily have passed as the genuine compositions of the authors upon whom they were confessedly modelled, although they were, of course, not originally written with any such fraudulent design.

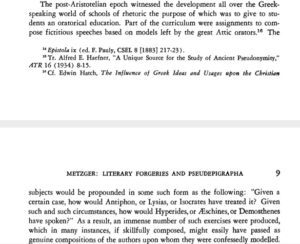

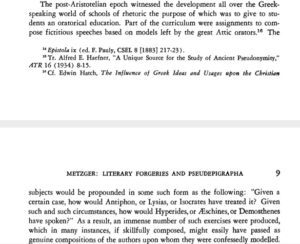

Metzger’s version (pp. 8–9) is as follows:

Metzger’s version from “Literary Forgeries”

The post-Aristotelian epoch witnessed the development all over the Greek- speaking world of schools of rhetoric the purpose of which was to give to students an oratorical education. Part of the curriculum were assignments to compose fictitious speeches based on models left by the great Attic orators. The subjects would be propounded in some such form as the following: “Given a certain case, how would Antiphon, or Lysias, or Isocrates have treated it? Given such and such circumstances, how would Hyperides, or Aeschines, or Demosthenes have spoken?” As a result, an immense number of such exercises were produced, which in many instances, if skillfully composed, might easily have passed as genuine compositions of the authors upon whom they were confessedly modelled.

Yikes. This passage is lifted nearly verbatim from Gudeman, and with no attribution. I must confess to chuckling at the irony of this happening in an article on literary forgery and pseudepigrapha—and in a paragraph on mimesis, no less. But there’s more, as Gudeman says (p. 64):

For there is scarcely an illustrious personality in Greek literature or history from Themistocles down to Alexander, who was not credited with a more or less extensive correspondence.

Metzger’s version (p. 10) is as follows:

There is scarcely an illustrious personality in Greek literature or history from Themistocles down to Alexander, who was not credited with a more or less extensive correspondence.

Yet another example of verbatim agreement, and it’s made even worse by the fact that Metzger nowhere cites Gudeman’s chapter in his article. There may be more examples, but these were the ones I have in my notes from back in 2008, and I haven’t been interested enough to work through the articles more closely since then. Needless to say, this led to some interesting discussion in the seminar that week.

For his part, Bart didn’t think it likely that these were intentional plagiarisms. Instead, he thinks they were likely the result of Metzger’s peculiar method of taking notes for research projects, which involved writing down quotes and notes on the 3×5″ notecards that he carried with him everywhere and then would file for his projects. Bart’s thought was that Metzger probably wrote these quotes down on the cards but wasn’t always careful about recording the source on every card, making it too easy for Metzger to lose the connection between the quote and the source, accidentally misattributing what he had on a given card as his own words or notes (which he regularly composed on those cards as thoughts came to him) rather than a verbatim quote from someone else.

From my own reading of prior generations of scholarship, such sloppy documentation seems to be the norm rather than an exception, and in fairness, when the technology involves post-it notes or 3×5″ cards rather than Bookends or Endnote, it’s definitely more difficult to keep track of everything.

Nevertheless, some of us, including myself, were (and remain) a bit more skeptical of that explanation given the degree of verbatim agreement here and the fact that some of the material is reworked in exactly the way one would expect if someone knew he was plagiarizing. That said, either way, it’s a reminder of how important it is to have a rigorous and reliable research process that makes one less likely to plagiarize.

I must confess to being a bit terrified of accidental plagiarism in my own work, a fear that has only been increased by a few occasions in the last couple years in which either I or another reader/reviewer have noticed a quote where somehow the footnote containing the citation for a marked quotation had fallen out in the process of editing. Fortunately, all of these have been caught to date, but it’s definitely an occupational hazard of which I’m especially wary.

(Disclosure: I receive affiliate income from the purchase of any books through the links above.)

The post Bruce Metzger and Plagiarism – Literary Forgeries Edition appeared first on Jason Staples.

Bruce Metzger and Plagiarism – Literary Forgeries Edition

Back in the spring of 2008, I took Bart Ehrman’s seminar on “Literary Forgery in the Early Christian Tradition.” At the time, Bart was working toward his book, Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Christian Polemics, which he later popularized into Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Aren’t Who We Think They Are, and the rest of us benefited from his having collected extensive resources on the subject and suffered together through Wolfgang Speyer’s Die literarische Fälschung.

But that’s not the subject for today’s post. The second week of the class was on the Disputed Pauline epistles (or, as Bart prefers, the Deutero-Pauline epistles)—that is, 2 Thessalonians, Colossians, and Ephesians, each of which is thought not to have been written by the historical apostle Paul by a reasonably high percentage of critical scholars. One of the articles we read for the class was from Bart’s Doktorvater (and now my Doktorgroßvater), Bruce Metzger, “Literary Forgeries and Canonical Pseudepigrapha,” JBL 91 (1972): 3–24.

We read this article after going through earlier (19th century) materials on the same subject and were all surprised to find numerous examples of verbatim or near-verbatim agreement between Metzger’s article and Alfred Gudeman’s 1894 chapter on “Literary Frauds among the Greeks.” I’ll list the examples below, with underlining where there is substantive agreement.

On pp. 66–67 of his chapter, Gudeman says the following:

Finally, I draw attention to one other instance of a literary forgery which is of particular interest, because it furnishes the only example, at least the only one that has come under my observation, of a literary fraud perpetrated from a motive of pure malice, it having been designed to blast the reputation of one of the greatest historians of Greece.

Apropos of a statue in Olympia, erected to Anaximenes of Lampsacus, the traveller Pausanias takes occasion to add a few details concerning this man and to give some of the reasons for his being thus honoured. We learn, accordingly, among other things, that Anaximenes was the author of a number of historical works, and that he was the inventor of extemporaneous speeches, whatever that may mean. The statue in question had been erected to him by his grateful fellow-citizens, because he had on one occasion saved the town of Lampsacus from destruction at the hands of the enraged Alexander, by a very clever ruse which he practised upon the great Macedonian. After relating the story, Pausanias continues as follows: This same Anaximenes once played an ingenious but very scurvy trick upon his enemy, the historian Theopompus. Being himself a sophist, and skilled in imitating the style of the sophists, he wrote a book, in which he slandered Athens, Sparta, and Thebes; and then counterfeiting to perfection the diction of the historian, he sent the work to these cities under the latter’s name, in consequence of which all Hellas was intensely exasperated at Theopompus.

Metzger’s article includes the following (pp. 6–7):

Occasionally a literary fraud was perpetrated from the motive of pure malice. A counterpart in antiquity to the modern fabrication in czarist Russia of the scurrilous “Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion” was the attempt of Anaximenes of Lampsacus to blast the reputation of one of his contemporaries, the historian Theopompus of Chios (4th cent. B.c.). According to the account of Pausanias, Anaximenes, being himself a sophist and skilled in imitating the style of sophists, once played a scurvy trick by composing, under the name of his rival Theopompus, bitter invectives against the three chief cities of Greece, Athens, Thebes, and Sparta. He then sent a copy of the slanderous work to each of these cities, with the result that the unfortunate historian was henceforth unable to appear in any part of the peninsula.

These are relatively minor, and if this was the extent of the verbatim agreements, we’d probably not have thought much of it. But there’s more later in the piece. On p. 73, Gudeman says:

Gudeman’s original version

The Post-Aristotelian epoch witnessed the development all over the Greek-speaking world of schools of rhetoric whose purpose it was to give to students an oratorical education. With a view to the attainment of this end, their pupils were called upon to compose fictitious speeches based upon the models left by the great Attic orators, the subjects being usually propounded in some such form as the following: “ Given a certain case, how would Antiphon, or Lysias, or Isocrates have treated it? Given such and such circumstances, how would Hyperides, or Aeschines, or Demosthenes have spoken?” As a result, an immense number of such μελέται, as they are styled in Greek, or suasoriae, by the Romans, were produced, which in many instances, if skilfully composed, might easily have passed as the genuine compositions of the authors upon whom they were confessedly modelled, although they were, of course, not originally written with any such fraudulent design.

Metzger’s version (pp. 8–9) is as follows:

Metzger’s version from “Literary Forgeries”

The post-Aristotelian epoch witnessed the development all over the Greek- speaking world of schools of rhetoric the purpose of which was to give to students an oratorical education. Part of the curriculum were assignments to compose fictitious speeches based on models left by the great Attic orators. The subjects would be propounded in some such form as the following: “Given a certain case, how would Antiphon, or Lysias, or Isocrates have treated it? Given such and such circumstances, how would Hyperides, or Aeschines, or Demosthenes have spoken?” As a result, an immense number of such exercises were produced, which in many instances, if skillfully composed, might easily have passed as genuine compositions of the authors upon whom they were confessedly modelled.

Yikes. This passage is lifted nearly verbatim from Gudeman, and with no attribution. I must confess to chuckling at the irony of this happening in an article on literary forgery and pseudepigrapha—and in a paragraph on mimesis, no less. But there’s more, as Gudeman says (p. 64):

For there is scarcely an illustrious personality in Greek literature or history from Themistocles down to Alexander, who was not credited with a more or less extensive correspondence.

Metzger’s version (p. 10) is as follows:

There is scarcely an illustrious personality in Greek literature or history from Themistocles down to Alexander, who was not credited with a more or less extensive correspondence.

Yet another example of verbatim agreement, and it’s made even worse by the fact that Metzger nowhere cites Gudeman’s chapter in his article. There may be more examples, but these were the ones I have in my notes from back in 2008, and I haven’t been interested enough to work through the articles more closely since then. Needless to say, this led to some interesting discussion in the seminar that week.

For his part, Bart didn’t think it likely that these were intentional plagiarisms. Instead, he thinks they were likely the result of Metzger’s peculiar method of taking notes for research projects, which involved writing down quotes and notes on the 3×5″ notecards that he carried with him everywhere and then would file for his projects. Bart’s thought was that Metzger probably wrote these quotes down on the cards but wasn’t always careful about recording the source on every card, making it too easy for Metzger to lose the connection between the quote and the source, accidentally misattributing what he had on a given card as his own words or notes (which he regularly composed on those cards as thoughts came to him) rather than a verbatim quote from someone else.

From my own reading of prior generations of scholarship, such sloppy documentation seems to be the norm rather than an exception, and in fairness, when the technology involves post-it notes or 3×5″ cards rather than Bookends or Endnote, it’s definitely more difficult to keep track of everything.

Nevertheless, some of us, including myself, were (and remain) a bit more skeptical of that explanation given the degree of verbatim agreement here and the fact that some of the material is reworked in exactly the way one would expect if someone knew he was plagiarizing. That said, either way, it’s a reminder of how important it is to have a rigorous and reliable research process that makes one less likely to plagiarize.

I must confess to being a bit terrified of accidental plagiarism in my own work, a fear that has only been increased by a few occasions in the last couple years in which either I or another reader/reviewer have noticed a quote where somehow the footnote containing the citation for a marked quotation had fallen out in the process of editing. Fortunately, all of these have been caught to date, but it’s definitely an occupational hazard of which I’m especially wary.

(Disclosure: I receive affiliate income from the purchase of any books through the links above.)

The post Bruce Metzger and Plagiarism – Literary Forgeries Edition appeared first on Jason Staples.

February 18, 2020

Cambridge University Press to Publish The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism

It is with great pleasure that I pass along the news that my book, The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: A New Theory of People, Exile, and Israelite Identity has been accepted by Cambridge University Press and should be published by the end of 2020.

This book represents over a decade of work, and to say I’m looking forward to seeing it in the wild would be an understatement. A basic abstract of the project follows:

This study examines how the concept of “Israel” was constructed and contested among Jews, Samaritans, and others in the Second Temple Period (roughly 515 BCE–70 CE), as different sects and groups laid claim to the heritage of biblical Israel and differentiated themselves from others doing the same.

Through exhaustive analysis of early Jewish and Samaritan evidence, the books demonstrate that (contrary to the assumptions of most modern scholarship) the terms “Israelite” and “Jew” were not synonymous in Second Temple Period. Instead, the most common view reflected in early Jewish sources is that the Jews are only a subset of the larger body of Israel, namely the descendants of the southern kingdom of Judah. Samaritans, by contrast, neither called themselves Jews nor were they regarded as such by others, but they did consider themselves Israelites, with different Jewish groups having varying responses to this claim. Moreover, the study demonstrates that the continued distinction between “Jews” and “Israelites” in Jewish literature frequently seems to reflect continuing hopes for a future restoration of reconstituted twelve-tribe Israel including the northern tribes of Israel scattered by the Assyrians in the eighth century BCE.

The project thereby introduces a new model for understanding the relationship between the terms “Israelite” and “Jew,” a problem that has drawn increased attention in recent scholarship. In the process, this study helps contextualize the variety of eschatological views that appear in Jewish literature from the Second Temple Period, correcting several recent scholarly trends in this area.

I am especially pleased that the book will be priced affordably, between $35–45 per hardback copy.

The post Cambridge University Press to Publish The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism appeared first on Jason Staples.

Cambridge University Press to Publish The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism

It is with great pleasure that I pass along the news that my book, The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism: A New Theory of People, Exile, and Israelite Identity has been accepted by Cambridge University Press and should be published by the end of 2020.

This book represents over a decade of work, and to say I’m looking forward to seeing it in the wild would be an understatement. A basic abstract of the project follows:

This study examines how the concept of “Israel” was constructed and contested among Jews, Samaritans, and others in the Second Temple Period (roughly 515 BCE–70 CE), as different sects and groups laid claim to the heritage of biblical Israel and differentiated themselves from others doing the same.

Through exhaustive analysis of early Jewish and Samaritan evidence, the books demonstrate that (contrary to the assumptions of most modern scholarship) the terms “Israelite” and “Jew” were not synonymous in Second Temple Period. Instead, the most common view reflected in early Jewish sources is that the Jews are only a subset of the larger body of Israel, namely the descendants of the southern kingdom of Judah. Samaritans, by contrast, neither called themselves Jews nor were they regarded as such by others, but they did consider themselves Israelites, with different Jewish groups having varying responses to this claim. Moreover, the study demonstrates that the continued distinction between “Jews” and “Israelites” in Jewish literature frequently seems to reflect continuing hopes for a future restoration of reconstituted twelve-tribe Israel including the northern tribes of Israel scattered by the Assyrians in the eighth century BCE.

The project thereby introduces a new model for understanding the relationship between the terms “Israelite” and “Jew,” a problem that has drawn increased attention in recent scholarship. In the process, this study helps contextualize the variety of eschatological views that appear in Jewish literature from the Second Temple Period, correcting several recent scholarly trends in this area.

I am especially pleased that the book will be priced affordably, between $35–45 per hardback copy.

The post Cambridge University Press to Publish The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism appeared first on Jason Staples.