Robert Prentice's Blog

September 2, 2025

Reine Marie José d’Italie

La reine Marie José d’Italie demeure l’une des dames les plus emblématiques des familles royales d’Europe. Pourtant, beaucoup en savent peu sur sa vie, en particulier au-delà du glamour tel qu’il était dépeint autrefois. Comme cet article (ci-dessous) le révèle, il y avait bien plus à cette personne pragmatique, mais ayant un esprit démocratique.

En mai 1946, une grande dame aristocratique passait la journée à aider les sans-abri dans la région de Cassino. Cependant, lorsque un assistant l’a appelée ‘Votre Majesté’, l’individu a soudainement réalisé qu’elle était devenue Reine d’Italie. La dame en question était Marie-José, la fille du feu Roi Albert I des Belges et de sa femme Elisabeth. Mais comment cette situation avait-elle pu se produire?

Marie-José quand elle était enfant.

Marie-José quand elle était enfant.La princesse Marie-José est née à Ostende en août 1906. Elle était la benjamine des enfants du roi Albert Ier des Belges et de sa consort, née duchesse Élisabeth de Bavière. Par celle-ci, elle était petite-nièce de l’iconique impératrice Élisabeth d’Autriche (‘Sisi’). La princesse a d’abord été élevée au château de Laeken à Bruxelles, avec une maison de campagne à Ciergnon. Alors que les batailles de la Première Guerre mondiale se déroulaient en Europe continentale, elle a passé de nombreuses années de primaire en Angleterre où elle a fréquenté l’Ursuline Convent High School à Brentwood, Essex. Une influence particulière était Mademoiselle Hammersley, une femme anglaise raffinée qui s’occupait de sa protégée. En 1917, Mademoiselle Hammersley accompagnerait Marie-José en Italie où la princesse fréquenta l’Istituto Statale della Santissima Annunziata à Florence. Les cours étaient traditionnellement enseignés ici en italien, anglais et allemand.

Marie-José avant son mariage

Marie-José avant son mariageAvec l’arrivée de la paix, la princesse Marie-José retournerait à Bruxelles où, en 1919, elle s’inscrivit à l’Institut Sacré-Cœur à Linthout sous la direction de la Mère Supérieure Jacquemin. Elle y resterait jusqu’à l’âge de dix-huit ans et bénéficierait d’une éducation catholique de bonne qualité.

Un visiteur au port d’Anvers en Belgique à l’automne 1922 était Umberto, le Prince de Piémont et héritier du trône d’Italie. Il est arrivé à Anvers à bord du navire Ferruccio pour représenter officiellement l’Italie à l’inauguration d’un nouveau canal. Il a été accueilli par Marie-José et ses frères. La princesse a ensuite été montrée sur le navire par Umberto (qu’elle avait rencontré plusieurs années auparavant en Italie) et a été impressionnée par son apparence bronzée, ses cheveux d’un noir jais et son élégant uniforme militaire blanc. Ce fut une brève rencontre, au cours de laquelle les visites du Prince de Piémont à Rhodes, Benghazi et Tripoli ont été discutées. Il devait y avoir une étincelle suffisante entre eux, car le septembre suivant, la famille royale belge a été invitée pour une visite d’un mois au château de Racconigi près de Turin. Bien que des devoirs militaires et officiels aient signifié qu’Umberto n’a fait qu’une seule brève apparition, cela a donné à Marie-José un aperçu de la vie au sein de la Maison de Savoie. Cette visite a également dû s’avérer fructueuse car l’année suivante, la mère d’Umberto, la reine Elena, a écrit pour dire à une amie en Belgique qu’elle continuait à espérer une union entre son fils et la princesse Marie-José.

Ainsi, en janvier 1930, à la suite d’une longue romance, la princesse avait épousé Umberto, le prince de Piémont, dans la chapelle historique Paolina du palais du Quirinal à Rome. Au départ, Marie-José et Umberto vivaient au palais royal de Turin. Cependant, contrairement à son mari plus respectueux (qui appelait toujours son père, le roi Victor Emmanuel, ‘Majesté’), la princesse belge était beaucoup plus une âme libre. Elle préférait organiser des soirées musicales passionnantes et travailler avec la Croix-Rouge plutôt que d’observer une étiquette de cour stricte. Dès le départ, Marie-José était également passionnée par l’étude de l’histoire de la Maison de Savoie, dans laquelle elle s’était mariée.

Le prince et la princesse de Piémont le jour de leur mariage

Le prince et la princesse de Piémont le jour de leur mariageCependant, un déménagement à Naples, en novembre 1931 (où Umberto avait été nommé Commandant de la 25e Infanterie), devait s’avérer fortuit. Le couple pouvait échapper aux confins du Palais Royal de la ville pour des week-ends de détente à la Villa Rosebery dans la banlieue balnéaire de Posillipo. Marie-José se sentait également plus émancipée parmi les Napolitains heureux et détendus : elle jouait au tennis trois fois par semaine à la Villa Communale et avait établi un Réfectoire Public pour nourrir les pauvres de la ville. Épanouie et amoureuse, elle décrivit plus tard cette époque comme ‘les meilleures années de notre mariage.’ L’apogée de sa joie fut la naissance d’une fille bien-aimée, Maria Pia, le 24 septembre 1934.

Pourtant, c’était aussi une période difficile. Le père de Marie-José, le roi Albert, est mort dans un accident d’escalade pendant sa grossesse et on lui a conseillé de ne pas voyager en Belgique pour les funérailles. Puis, en août 1935, sa chère belle-sœur suédoise, la reine Astrid, a été tuée dans un horrible accident de voiture en Suisse. Toujours en arrière-plan, il y avait aussi les machinations troublantes du gouvernement d’extrême droite de Mussolini, ou plus précisément son invasion de l’Éthiopie en octobre 1935. Bien que la Princesse ait de graves réserves sur les actions et les politiques d’Il Duce, elle s’est débrouillée en essayant d’être d’une utilité pratique. Marie-José a été formée comme infirmière et a suivi un cours en médecine tropicale. Son travail à l’hôpital lui vaudra bientôt le titre de ‘Soeur Marie-José.’ Lors d’une tournée des troupes italiennes en Afrique en 1936, la Princesse a été troublée par les mauvaises installations et le moral bas des troupes. Elle était également indignée par la machine de propagande de Mussolini, qui la décrivait de manière provocante, mais inexacte, comme l’ ‘Impératrice de Éthiopie ‘

Avec le passage du temps, Marie-José déplorait la proximité croissante d’Il Duce avec Hitler. Cela entraînerait finalement une confrontation, lorsque la Princesse décida que les bénéfices de ses concerts de collecte de fonds à Naples devraient être donnés à son ‘Fonds de travail de la Princesse de Piémont’ plutôt qu’au ‘Fonds national de travail’ du Fasciste. Un des principaux bénéficiaires de la générosité de son Fonds était ‘l’Association nationale pour le sud de l’Italie’, une région plus pauvre, qui était supervisée par l’éminent archéologue et anti-fasciste, Umberto Bianco. Le régime fasciste à Rome était furieux. Ils n’étaient pas non plus enchantés par l’association de Marie-José avec des ‘libéraux’ tels que l’archevêque de Naples, le cardinal Alessio Ascaresi et le philosophe Benedetto Croce, dont la maison fut perquisitionnée par des soldats fascistes.

Marie-José en tant que Princesse de Piémont

Marie-José en tant que Princesse de PiémontEn février 1937, la princesse de Piémont a donné naissance à un fils, Vittorio Emanuele. Elle n’a pas été très heureuse d’apprendre que le Grand Conseil fasciste avait le pouvoir de délibérer sur la capacité d’un héritier à régner et a confronté Mussolini à ce sujet. Il a été déstabilisé par son approche directe, si différente de celle de son beau-père, le roi, que Marie-José considérait comme complaisant dans ses relations avec les fascistes. ‘Un monarque’, a reproché Marie-José à son mari Umberto, ‘doit être là pour tous ses peuples.’ Une rencontre avec Hitler à Naples n’a guère dissuadé son point de vue ‘démocratique’. En effet, en septembre 1938, la princesse a rencontré le héros de la Première Guerre mondiale, le maréchal Pietro Badoglio au château de Racconigi pour discuter d’un plan visant à évincer Mussolini et à persuader le roi Victor Emmanuel ‘discrédité’ d’abdiquer, ouvrant ainsi la voie à un gouvernement anti-fasciste. Cependant, l’accord de Munich du 29 septembre a court-circuité cette tentative.

Lorsque l’Italie a déclaré la guerre à la Grande-Bretagne et à la France, en juin 1940, Marie-José a informé une dame d’honneur que la monarchie en Italie était ‘finie’. Elle était déjà sous le choc des nouvelles de l’invasion de sa patrie, la Belgique, par les forces nazies le 10 mai. En effet, la princesse avait été ‘prévenue’ des intentions de l’Allemagne par un Pape Pie sympatique le 6 mai. Cependant, les tentatives de Marie-José pour alerter le gouvernement belge ont été contrecarrées par l’ambassadeur belge à Rome qui a rejeté l’avertissement comme une ‘rumeur ennemie’.

Quelles que soient ses émotions personnelles, la princesse se concentrait désormais sur l’aide aux personnes dans le besoin. Après la naissance de son troisième enfant, Maria Gabriella, elle passa l’été 1940 à travailler avec la Croix-Rouge sur le Front occidental et organisa même un train-hôpital pour transporter les blessés du Front. En septembre, Marie-José rendit visite à Bruxelles pour des discussions avec son frère, le roi Léopold III, qui avait décidé de vivre l’occupation allemande avec son peuple. Il demanda à sa sœur bien-aimée de rencontrer Hitler pour demander la rapatriement des prisonniers de guerre belges et solliciter des denrées alimentaires indispensables. Encore une fois, la princesse mit de côté ses sentiments individuels pour le bien de sa patrie et rendit visite au Führer à Berchtesgaden le 17 octobre. Il semblait désintéressé, bien que Marie-José persista avec détermination et lui parla des ‘nombreuses souffrances infligées au peuple belge.’ Elle encouragea également son frère à engager un dialogue avec Hitler sur les différentes questions.

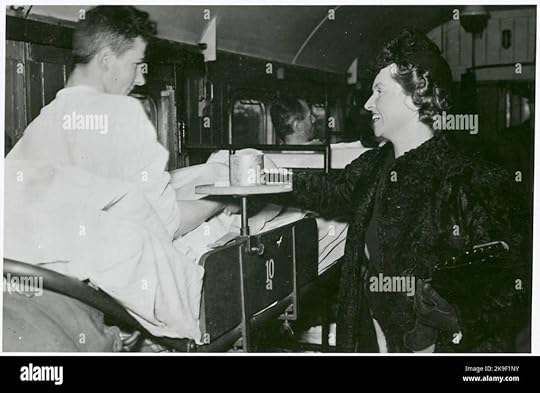

Marie-José en uniforme de la Croix-Rouge.

Marie-José en uniforme de la Croix-Rouge.Lorsque l’Italie a déclaré la guerre aux États-Unis, en décembre 1941, la princesse avait déjà conclu que sa patrie adoptive ne pourrait pas gagner la guerre. Elle a de nouveau tenté de contacter le Maréchal Badoglio pour lui faire comprendre la nécessité d’éliminer les fascistes et de mettre fin à la guerre. Les événements allaient soutenir son point de vue : à la fin de 1942, l’Italie souffrait de revers militaires en Libye et en Russie. Le Maréchal, cependant, attendait un signal du Roi ‘constitutionnel’ qui, à son tour, cherchait un signal du peuple!

Sans se laisser décourager, la Princesse poursuivit son travail dans les hôpitaux et parmi les sans-abri et les dépossédés, dont le nombre avait considérablement augmenté en raison des bombardements alliés. Marie-José était également touchée par les manifestations d’affection du peuple envers elle lors de ses visites dans ses réfectoires à Rome et Naples. Déjà enceinte de son quatrième enfant, Maria Beatrice, la Princesse cherchait parfois refuge dans des maisons locales lors des bombardements, où elle se voyait offrir du café et, à une occasion, un bouquet de fleurs du jardin.

En revanche, Mussolini semblait distrait et marqué par le souci. L’arrogance avait disparu alors que les défaites de l’Italie s’accumulaient. Lorsque les Alliés ont envahi la Sicile le 10 juillet 1943, le roi Victor Emmanuel, d’habitude indécis, a enfin décidé d’agir et, le 25 juillet, lorsque le Duce est venu à la Villa Savoia du roi pour une audience, il a été arrêté. Il est révélateur que le Duce ait crié : ‘C’est la Princesse de Piémont [le titre royal officiel de Marie-José] qui sera heureuse.’ Il est clair que Mussolini réalisait que cette princesse ‘démocratique’ de Belgique était l’une de ses plus grandes ennemies.

À la suite de la capitulation de l’Italie face aux Alliés le 8 septembre 1943, un officiel de la Maison Royale a rendu visite à Marie-José à son emplacement actuel au Château de Serre dans la vallée d’Aoste et a demandé qu’elle se rende en Suisse. C’était probablement pour sa propre sécurité, alors que les forces allemandes envahissaient désormais l’Italie et occupaient les zones centrales et nordiques. La Princesse et ses quatre enfants se sont d’abord installés à l’Hôtel Excelsior à Montreux, puis ont déménagé à l’Hôtel Montana, à Oberhofen. Son ennemi, Mussolini, avait entre-temps été ‘libéré’ par les Allemands et avait établi la ‘république marionnette’ de Salò. Le Roi et d’autres membres de la famille royale italienne sont restés à Naples, qui a été occupée par les Alliés le 11 octobre. L’Italie a déclaré la guerre à l’Allemagne le 13 octobre.

Bien que Marie-José souhaite désormais rejoindre les forces partisanes pour combattre les forces nazies dans le nord de l’Italie, elle a réalisé que si sa participation était découverte, il pourrait y avoir des représailles pour la population locale. Au lieu de cela, la princesse s’est contentée de faire passer des armes à la frontière suisse pour une utilisation de l’autre côté en Italie. C’était très risqué car elle était sous surveillance constante des autorités suisses et aussi des agents ennemis.

Le 23 janvier 1944, le diplomate italien Gallarati Scotti a rencontré Marie-José à Oberhofen. Il a discuté d’un plan pour installer la princesse comme régente pour son fils, Vittorio Emanuele, et espérer rapprocher la monarchie du peuple. Marie-José était, après tout, considérée comme une démocrate, sans liens avec Mussolini ou son régime fasciste de droite. Cependant, ceux qui étaient actuellement au pouvoir décidèrent que l’autorité royale future devrait plutôt reposer sur son mari Umberto, qui fut nommé Lieutenant-Général du Royaume en juin 1944, avec tous les pouvoirs royaux, suite à la libération de Rome par les Alliés. Ce n’est qu’à la fin avril 1945 que Marie-José retourna en Italie, traversant les Alpes à pied depuis la Suisse, escortée par deux guides de montagne. Des combattants de la résistance communiste lui firent ensuite escorte jusqu’au Château de Sarre. Émouvant, sa présence ultérieure à un Te Deum dans la cathédrale voisine d’Aoste fut accueillie par des applaudissements chaleureux de la part des autres fidèles.

En mai 1945, la princesse déménagea à Turin et ouvrit une cantine de la Croix-Rouge pour aider les sans-abris. Enfin, elle arriva à Rome, voyageant par avion depuis Turin, le 16 juin, pour une réunion tant attendue avec Umberto qu’elle n’avait pas vu depuis deux ans. Pourtant, elle était également hantée par la vue des ruines des villes autrefois vibrantes qu’elle survolait en route. En août, les enfants royaux (qui avaient séjourné à Glion où, à un moment, Maria Pia et Maria Gabriella avaient toutes deux succombé au typhus) rentrèrent également chez eux à Rome. Pendant ce temps, Umberto avait ouvert une aile du Quirinal pour accueillir les sans-abris, alors Marie-José vendit des bijoux pour aider à fournir des fonds nécessaires à l’ouverture d’une autre cantine, ainsi qu’un atelier pour que les femmes locales puissent confectionner des vêtements. Néanmoins, il y avait beaucoup de ceux qui s’opposaient à Umberto, estimant qu’il n’avait pas suffisamment résisté à Mussolini. Umberto décida alors qu’un référendum devrait être organisé sur l’avenir de la monarchie. Celui-ci devait avoir lieu en juin 1946.

En attendant, le roi Victor Emmanuel a abdiqué le 9 mai et est parti en exil à Alexandrie en Égypte. Umberto était désormais roi d’Italie et Marie-José était sa reine consort. Mais pour combien de temps ?

Ironiquement, au moment où l’auxiliaire mentionné ci-dessus, à Cassino, faisait référence à Marie-José en tant que ‘Sa Majesté’, la nouvelle Reine se préparait déjà mentalement à l’exil. Son pressentiment était juste, car après le référendum (au cours duquel elle vota dans une école locale, en soumettant un bulletin de vote blanc), Marie-José fut informée en privé que 54 % des électeurs avaient voté en faveur d’une république. Le Roi ordonna maintenant à sa femme de partir immédiatement pour le Portugal. Mais d’abord, elle s’assura de téléphoner aux responsables de toutes ses œuvres de charité, en soulignant que leur travail devait se poursuivre sous une république.

Le 5 juin, Marie-José et les enfants prirent l’avion de Rome à sa chère Naples et à la Villa Rosebery. Elle demanda à quiconque voulait l’entendre : ‘Pourquoi ne puis-je pas rester ici en tant que citoyenne ordinaire ?’ Cependant, le lendemain matin, elle et sa famille embarquèrent à bord du navire, à destination de Lisbonne. Alors qu’elle regardait la côte italienne disparaître au loin, l’ancienne reine réfléchit : ‘Pour la première fois, je suis libre de toute la fausse apparence et de l’hypocrisie qui m’ont entourée.’ Soudain, son ‘règne’ de moins d’un mois était terminé. Elle devint désormais connue pour la postérité sous le nom de La Regina di Maggio (La Reine de Mai).

Après la confirmation des résultats du référendum, Umberto a ensuite rejoint sa famille dans un domaine à Sintra, la Quinta de Bella Vista. Lui et Marie-José ont trouvé la vie ensemble difficile. Elle a plus tard exprimé sa plainte en disant que ‘Umberto était angoissé, accablé par une souffrance intérieure qu’il ne pouvait pas partager. Cela a commencé à me perturber et m’a mis mal à l’aise dans ma propre maison.’ La fille du couple, la Princesse Maria Pia, a souligné que ses parents étaient des caractères ‘très différents’. Umberto était ‘très sérieux et conscient de son rôle’ tandis que sa mère, ‘aimait rire et marcher seule dans la rue. [Mon père] n’aurait jamais fait cela.’

La reine Marie-José dans les années 1950

La reine Marie-José dans les années 1950Les choses dans le mariage sont devenues tendues lorsque Marie-José a reçu une transfusion du mauvais groupe sanguin lors d’une opération de l’appendicite. Elle est tombée immédiatement dans le coma et, lorsqu’elle a repris conscience, il a été découvert que sa vue était gravement altérée en raison d’hémorragies rétiniennes. La Reine s’est rendue en Suisse pour suivre un traitement sous la direction de l’ophtalmologiste Adolphe Franceschetti. Cependant, les dommages se sont révélés permanents et étaient tels que si elle regardait vers le bas, elle ne voyait rien. Marie-José restait désormais éternellement méfiante face aux escaliers. Malheureusement, il s’avérait politiquement inapproprié pour Umberto de suivre sa femme en Suisse et Marie-José, déconcertée par l’apparente incapacité de son mari à réagir à sa situation, supposait qu’il désirait la solitude.

En temps voulu, la Reine acheta un petit château, Merlinge, près de Gy. Son fils Vittorio la rejoignit là-bas, tandis que ses autres enfants lui rendaient visite à intervalles réguliers depuis le Portugal. Elle parlait désormais rarement du passé mais avouait regretter la chaleur de Naples. Ses journées étaient consacrées à des recherches sur la Maison de Savoie, dont elle écrivit plusieurs livres. Un autre intérêt était la musique, ce qui l’amena à établir le Prix International de Composition Musicale Reine Marie-José. Les voyages étaient également une attraction et, accompagnée de sa mère, la Reine Elisabeth des Belges, Marie-José se rendit en Inde (où elle rencontra Nehru) et en Chine.

Dans les années 1980, l’âge rattrapait à la fois Marie-José et Umberto. Ce dernier est décédé en mars 1983, après une longue et douloureuse bataille contre le cancer. Lui et sa femme avaient toujours gardé contact et la Reine le visitait souvent à l’hôpital. Marie-José a continué à se battre, souvent avec douleur et utilisant une canne : En mars 1988, elle a effectué sa première visite en Italie depuis 1946, visitant Aoste pour assister à une conférence historique suivie d’une visite du Palais Royal de Turin et des Archives d’État. Lorsqu’on lui a demandé ce qu’elle pensait des monarchistes italiens, elle a habilement répondu : ‘Je suis une Reine, mais je ne suis pas une Monarchiste.’

À un âge avancé, Marie-José est tombée amoureuse du Mexique lors de ses visites à sa fille Maria Béatrice à Cuernavaca. Elle a ensuite acheté une villa là-bas avec une piscine, dans laquelle elle se baignait tous les jours. La Reine a accueilli une large gamme de visiteurs, y compris son neveu, le roi Albert II des Belges. Bien que le corps de Marie-José puisse maintenant la lâcher, son esprit n’était certainement pas affecté. Maria Béatrice se souvenait de l’esprit ‘jeune’ et de la ‘manière de penser moderne’ de sa mère.

En 1995, dans un esprit réfléchi, Marie-José entreprit une visite en Belgique. L’année suivante, elle décida de retourner vivre en Suisse, cette fois avec son fils, Vittorio Emanuele. Ce dernier organisa une fête en plein air pour célébrer le 90e anniversaire de sa mère le 4 août 1996, un anniversaire qu’elle partageait avec la reine mère du Royaume-Uni, Elizabeth, qui avait six ans de plus. En 1999, Marie-José visita Florence pour recevoir la liberté de la ville et l’année suivante, elle reçut une invitation pour assister aux célébrations du 100e anniversaire de la reine Elizabeth à Londres. Malheureusement, elle était trop fragile pour accepter.

Reine Marie-José dans un âge avancé

Reine Marie-José dans un âge avancéSa Majesté la Reine Marie-José d’Italie, Princesse de Belgique, est décédée le 27 janvier 2001 à l’Hôpital du Canton de Genève, à l’âge vénérable de 94 ans. Elle avait reconnu des membres de sa famille jusqu’à la fin. Lors de ses funérailles à l’Abbaye de Hautcombe, le 2 février, son cercueil, drapé avec le drapeau belge et les armes de sa chère Maison de Savoie, a été porté par des membres de la famille et des royalties européennes. Son cher chœur Alpini a chanté quelques chansons favorites et l’hymne sarde, ‘Conservat Deu Su Re Sardu’ (chanté à son mariage) a résonné dans l’Abbaye. C’est un témoignage de la personne que, au fil des ans, la Reine est toujours rappelée avec grande affection.

August 29, 2025

Death of Belgium’s Queen Astrid

Astrid and Leopold as royal bride and groom.

Astrid and Leopold as royal bride and groom. On 29 August 1935, some 90 years ago, a most tragic road accident occurred in Switzerland. The driver of the Packard 120 open-topped sports car was none other than King Leopold of the Belgians. Beside him in the passenger seat was his beautiful wife, Queen Astrid. As they journeyed together along the Lucerne to Zurich road, just before the village of Küssnacht, Leopold seemed to lose control of the car as it unexpectedly skidded on the narrow, winding road and rolled down a hill. Astrid was thrown from the vehicle and flung against a tree. She suffered fatal head injuries, including a fractured skull. Leopold was also injured and by the time he reached her, she was already dead (although other sources say she died in his arms).

The wreckage of the Packard 120 Car being recovered. A complete write-off. Original Photograph by Willy Rogg.

The wreckage of the Packard 120 Car being recovered. A complete write-off. Original Photograph by Willy Rogg. The news of her death immediately plunged Belgium into deep mourning. Crowds gathered around the newsstands to observe the latest newspaper reports: the front pages of both De Standaard and Le Soir were heavily edged in black as a mark of respect. There was a sense of incredulity that their beloved “Snow Queen” was suddenly no more. Thoughts also turned to her widower husband, Leopold and the couple’s three children, Joséphine-Charlotte, Baudouin and Albert, the latter who had been born only the previous summer. Meanwhile, in her home country of Sweden, the people were also stunned as they remembered this beautiful Swedish princess, with her toothy grin, who had been raised in an unspoilt fashion, in Stockholm, by her parents, Prince Carl, Duke of Västergötland and his Danish-born wife Princess Ingeborg. In Oslo too, Astrid’s older sister, Märtha, the Crown Princess of Norway was also much affected by the news; as was the eldest of the three sisters, Princess Margaretha who had married into the Danish Royal House.

Princess Astrid of Sweden (far right) with her sisters and mother Princess Ingeborg.

Princess Astrid of Sweden (far right) with her sisters and mother Princess Ingeborg. Queen Astrid with her older children, Joséphine-Charlotte and Baudouin

Queen Astrid with her older children, Joséphine-Charlotte and BaudouinAstrid’s mortal remains were carried by train from Switzerland to Brussels, arriving there on 30 August. A lying-in-state took place at the Royal Palace which would last for three days (although the family actually lived at the Château du Stuyvenberg at Laeken). Meanwhile, Astrid’s parents arrived from Sweden; her mother Princess Ingeborg was photographed in deepest mourning staring forlornly at a bronze statue of her late daughter, now wreathed in flowers as a symbol of respect. Outside, the street lamps were covered in black mourning cloth, flags flew at half-mast and there was a ceremonial fly-past by the Belgian Air Force.

The funeral procession of Queen Astrid of the Belgians.

The funeral procession of Queen Astrid of the Belgians.The funeral took place on 3 September. The courtyard of the Royal Palace was covered in wreaths and floral tributes. Astrid’s mother-in-law Queen Elisabeth, with Joséphine-Charlotte at her side, openly wept, as she watched her son Leopold, himself bandaged and injured, walk with his head bowed behind the funeral hearse accompanied by his father-in-law, Prince Carl of Sweden. This was pulled by eight horses, each sporting black plumes attached to their heads. The royal ladies followed behind in carriages. The funeral route was lined by tens of thousands of people, just as it had been nine years before when she arrived in Brussels for the religious marriage service to Leopold, then titled the Duke of Brabant. Indeed, even at this moment, the crowds must have reflected on their stylish Queen, who was always dressed in wonderful couture clothes by Lanvin, Molyneux and Mainbocher, invariably accessorised by her trademark Delly Poelman hats, adorned with ostrich feathers and rich velvet, the outfits completed by hand made court shoes. Fortunately, over the years, the Belgian photographer Robert Marchand had taken many images of Astrid both en famille and for official purposes.

In keeping with tradition, Queen Astrid was interred in the Royal Crypt in the Church of Notre-Dame de Laeken. This would become a place of pilgrimage even many decades later. It is a measure of the esteem and love in which Queen Astrid was held, that in November 2005, an exhibition of her life ” Astrid et nous: regards croisés”, took place to commemorate the centenary of her birth. This was organised by the l’Association Royale Le Musée de la Dynastie at the BELvue Museum in the Place des Palais. Such was the demand from the public, that the exhibition was extended for a further six weeks. It was filled with many personal mementos, including Astrid’s recipe books, written in French (but with the thumbnails annotated in her native Swedish) as well as postcards sent to family members for her travels overseas to the Far East and Africa.

Astrid’s legacy has lived on through her children and grandchildren. Both Baudouin and Albert would hold the titles of King of the Belgians. In due course her grandson, Albert’s eldest son, Philippe, would accede to the throne following the abdication of his father in July 2013 (for health reasons). In 1953, Joséphine-Charlotte married Hereditary Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg, who in 1964 succeeded his mother, Grand Duchess Charlotte, to become Grand Duke of Luxembourg. As at the time of writing, another of Astrid’s grandsons, Henri, is the present Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

Forever Remembered: A Royal Icon.

Forever Remembered: A Royal Icon.

August 20, 2025

La reine mère Hélène rentre en Roumanie 2019

Lors d’un matin sombre à l’aéroport international de Genève, un cercueil, recouvert d’un drapeau royal, a été chargé à l’arrière d’un avion de transport militaire roumain. Le cercueil contenait les restes mortels de Sa Majesté la Reine Mère Hélène de Roumanie, Princesse de Grèce et du Danemark et la Princesse grecque senior de sa génération. Hélène est la dernière (et probablement l’une des dernières) membres d’une famille royale d’un ancien pays du bloc de l’Est dont les restes ont été rapatriés.

Hélène Princesse héritière de Roumanie

Hélène Princesse héritière de RoumanieAu moment de sa mort le 29 novembre 1982, la reine mère Hélène vivait dans un appartement à Lausanne. Étant donné que la Roumanie était alors dirigée par un dictateur communiste, Nicolae Ceaușescu, qui n’aurait certainement pas permis l’inhumation d’un membre de l’ancienne famille royale du pays dans son fief, une parcelle avait été achetée au cimetière de Boix-de-Vaux à Lausanne comme lieu de repos pour Hélène. Pourtant, elle ne devait pas être seule : le mari de la cousine d’Hélène, la princesse Olga, le prince Paul de Yougoslavie, y avait déjà été inhumé après sa mort en 1976 comme avaient été les restes mortels de son fils le prince Nicolas qui était mort dans un accident de voiture en Angleterre en 1954 (son corps avait été amené du cimetière près de la maison de feu sa tante, la princesse Marina, à Iver et réinhumée à Lausanne à la demande de la princesse Olga). En 1997, la princesse Olga a elle-même été enterrée au Bois-de-Vaux à la suite de sa mort à l’âge de 93 ans.

Cependant, suite à la ‘réhabilitation’ du prince Paul par la Haute Cour serbe en 2011, lui, Olga et les corps de Nicolas ont été exhumés et enterrés à nouveau, avec grande cérémonie, dans la crypte du Mausolée royal Karageorge à Oplenac en Serbie, le 6 octobre 2012.

Pendant ce temps, depuis la chute du régime Ceausescu en décembre 1989, la popularité de l’ancienne famille royale prenait de l’ampleur en Roumanie. Une grande partie de cela peut être attribuée à l’implication dévouée de la plus ancienne petite-fille de la reine-mère Hélène, Margareta (qui vivait désormais à Bucarest) et de sa Fondation Princesse Margareta de Roumanie. En effet, dès 2003, les restes mortels de l’ex-mari d’Hélène, le roi Carol II, avaient été rebaptisés dans sa patrie (de leur lieu de repos original dans le Panthéon de Bragance à Lisbonne) dans une chapelle latérale de la cathédrale de Curtea de Argeș dans les Carpates. Le 16 décembre 2017, son fils le roi Michel Ier a également été enterré à Curtea de Argeș, bien que dans un mausolée royal nouvellement construit, à côté des restes de sa défunte épouse, la reine Anne, qui est décédée en août 2016.

Reine Mère Hélène et Roi Michel de Roumanie

Reine Mère Hélène et Roi Michel de RoumaniePourtant, tout cela se passait alors que les restes mortels de la reine-mère Hélène languissaient encore à Lausanne. Cependant, début septembre 2019, il a été annoncé que le corps de Sa Majesté allait être rapatrié en Roumanie et réinhumée à Curtea de Argeș. Ce qui me ramène à l’aéroport international de Genève le matin du 18 octobre : Après avoir obtenu l’autorisation de vol nécessaire, l’avion militaire roumain a atterri à l’aéroport d’Otopeni, à Bucarest, où le cercueil de Sa Majesté a été reçu, juste après 11 heures, par une garde d’honneur composée de la 30e brigade de la garde, et soigneusement sorti de l’avion précédé d’une grande croix en bois portant l’inscription ‘Elena-Regina 1896-1982’. Regardaient la scène le Gardien de la Couronne de Roumanie (Margareta), son mari le prince Radu et deux d’autres petites-filles d’Hélène (les princesses Sophia et Maria). Étaient également présents une pléthore de politiciens et de représentants des dénominations religieuses roumaines et, particulièrement pertinent, de l’Église orthodoxe grecque.

La dépouille de la reine mère Hélène de retour en Roumanie

La dépouille de la reine mère Hélène de retour en RoumanieÀ la suite d’un bref service religieux, le cercueil de Sa Majesté a ensuite été transporté au Palais Elisabetha, où il a été exposé pendant un court moment dans la Salle du Roi. Le cortège funèbre s’est ensuite dirigé vers le nord, vers Curtea de Argeș, arrivant en fin d’après-midi pour être accueilli chaleureusement par une grande foule. Le cercueil – toujours drapé de l’étendard royal – a ensuite été placé sur un catafalque à la Vieille Cathédrale. Le public a ensuite été autorisé à présenter ses respects. Émouvant, le président de la Roumanie, Klaus Iohannis, a publié une déclaration décrivant la Reine Mère Hélène comme ‘un puissant symbole de dignité, d’honneur et de courage, et une figure spéciale de conduite morale dans le sombre vingtième siècle.’

Juste avant midi le 19 octobre, des membres de la famille royale roumaine et des représentants de maisons royales étrangères (le comte de Rosslyn représentait le prince de Galles, maintenant Le Roi Charles III) se sont réunis dans la vieille cathédrale pour le service religieux. Par la suite, le cercueil de la reine mère Hélène, contenant ses restes mortels, a été porté par des soldats jusqu’au nouveau mausolée royal à proximité. Sa Majesté est enterrée aux côtés de son fils bien-aimé, le roi Michel, et de la reine Anne. Les restes de son ancien mari, le roi Carol II, reposent également à proximité, ayant été transférés au nouveau mausolée royal au printemps.

August 10, 2025

King Gustav V of Sweden: Nazi Sympathiser?

King Gustav V of Sweden was an avowed Germanophile, as was many of his family. His late wife, the strong-willed Queen Victoria of Sweden, had after all been born a Princess of Baden and was both the granddaughter of Emperor Wilhelm I, as well as a cousin of Emperor Wilhelm II. Furthermore, the marriage was primarily a political alliance organised by Gustav’s father, King Oscar II, who was keen to forge strong ties with Germany. Victoria’s influence over her rather hesitant husband was considerable and was still evident in the years following her death in 1930. The latter’s cousin, Prince Maximilian von Baden, who died in 1929, was another influence. He had long emphasised to Gustav that Germany and Sweden had common interests against Russia. In 1915, during the Great War ‘Max’ even travelled to Drottningholm in an (ultimately futile) attempt to bring Sweden into the war on the German side. Another relative of the Swedish Queen, her second cousin Prince Victor of Wied was to serve as a counsellor in the German Legation in Stockholm between 1919-1922. In 1933, and by now a member of the National Socialist Workers’ Party, he returned to the Swedish capital in the powerful and influential post of German Minister. Wied-who was a friend of Hermann Göring-continued to foster relations between Sweden and Germany, not least through the King and members of the German and Swedish aristocracy, who were traditionally pro-German. It so happened that Göring’s Swedish first wife Carin, had been high-born. (Although she died in 1931, Carin would open up contacts on behalf of her husband which were still in use during World War 2.) It also helped that Gustav’s grandson (and heir-but-one to the Swedish throne) Gustav Adolf, had married the German Princess Sybilla of Coburg the previous year. Her English-born father, Charles Edward, the Duke of Coburg, was a staunch supporter of Hitler and the Nazi Regime and had contacts at the highest level in Berlin. He was also a friend of Victor of Wied. Unsurprisingly, in 1933, during a visit to Berlin, Gustav entertained the President of Germany and the newly-elected Chancellor, Adolf Hitler to lunch at the Swedish Legation. Meanwhile, in February 1939, the King paid another visit to Berlin, during which he conferred on Field Marshal Göring, a Commander Grand Cross of the Royal Order of the Sword, a distinguished Swedish military award.

King Gustav on a visit to Berlin with his grandson, Gustav Adolf. Field Marshal Göring in the centre.

King Gustav on a visit to Berlin with his grandson, Gustav Adolf. Field Marshal Göring in the centre. King Gustav and his German-born wife, Queen Victoria.

King Gustav and his German-born wife, Queen Victoria. However, when World War II commenced in September 1939, the Swedish government of Per Albin Hansson adopted a neutral stance, a view endorsed by King Gustav. Nevertheless, this would prove a difficult position to maintain and was to come at a price. The first challenge was when Germany invaded Sweden’s neighbours of Norway and Denmark on 9 April 1940. Gustav received news of this by telephone, just after 5am, from his Foreign Minister, Christian Günther. The latter had been informed of the dual invasions in person at his home on Ymervägen in Djursholm, only a few minutes earlier, by the German Minister in Stockholm, Prince Victor of Wied. The latter had been at pains to reassure Günther that Sweden, unlike Norway and Denmark, would not be invaded (subject to certain conditions) and that he would soon be in a position to hand over an official communication from Berlin which would elaborate on the German government’s position. Wied was as good as his word and, by 9am, a collection of notables, including the Prime Minister, the Foreign Minister and the Crown Prince, joined the King in his study at the Royal Palace to discuss Germany’s demands. It made uncomfortable reading: Firstly, Sweden was not allowed to mobilise its forces. Secondly, the Swedish navy must at all times not hinder German naval operations nor travel further than three miles from the Swedish coast. Neither was Sweden to impede German official telecommunications traffic. Of particular importance to the German war effort, deliveries of Swedish iron ore were to continue unhindered, with the mines to be protected against Allied sabotage attempts.

It would be fair to say that each person sitting round the table was fearful of the Nazi menace. They had no reason to doubt that if they did not agree to these terms, Hitler’s troops would soon be marching down the streets of Stockholm. Indeed, only the sceptical Crown Prince-who had previously been married to Britain’s Princess Margaret of Connaught and was currently married to the British-raised Louise Mountbatten (who outspokenly compared Nazism to Barbarism)-spoke out against acceptance of these conditions. Eventually, it was agreed to accept the German’s demands with one exception: Sweden would not agree to being prohibited from mobilising its forces. On April 19, King Gustav V wrote a personal letter to Hitler ‘affirming the intention of Sweden to maintain strictest neutrality and to resist the violation of Sweden’s frontiers by any powers.’ Hitler replied within days reaffirming Germany’s intention to respect Sweden’s neutrality unconditionally. But, as shall be seen, these words were merely diplomatic platitudes.

Gustaf V (centre) presides over a wartime Council of State meeting with Minister of Defence Per Edvin Sköld, Minister for Foreign Affairs Christian Günther, legal consultant Thorwald Bergquist and Minister of Justice Karl Gustaf Westman.

Gustaf V (centre) presides over a wartime Council of State meeting with Minister of Defence Per Edvin Sköld, Minister for Foreign Affairs Christian Günther, legal consultant Thorwald Bergquist and Minister of Justice Karl Gustaf Westman.However, even as he signed his letter to Hitler, Gustav V was already dealing with several dilemmas. The first was when his niece, Crown Princess Märtha of Norway, seeking to avoid capture by German occupying forces, travelled from Elverum across the border into Sweden with her three children in the early hours of 10 April. None of the party had passports but eventually the border guards let them through. Unsure of the reception she would receive from her Swedish relations, the Crown Princess then proceeded to the Högfjällshotell in the ski resort of Sälen where she was joined by her mother, the Danish-born Princess Ingeborg, who was no fan of the Germans, who had recently invaded her homeland.

King Haakon (second left) and Crown Prince Olav (extreme left) run for cover as German Heinkel aircraft attack them in April 1940

King Haakon (second left) and Crown Prince Olav (extreme left) run for cover as German Heinkel aircraft attack them in April 1940No sooner had Gustav received word of Märtha ’s arrival when another crisis crossed his desk. An exhausted King Haakon and Crown Prince Olav, who had remained in Norway but refused to cooperate with the Nazis, were currently being hounded by a crack group of 120 German commandos bent on their capture or death. They had reached the Swedish border post near Flötningen, on 12 April. The Norwegian Foreign Minister, Halvdan Koht, telephoned his Swedish counterpart, Christian Günther, seeking a guarantee that King Haakon might be allowed to cross over into Sweden and cross back safely after a night’s rest at a hostel. Günther discussed the matter with King Gustav. The reply was brisk and uncompromising: ‘The Swedish government does not want to provide guarantees regarding return travel in advance.’ It was also indicated that under international law, if the Norwegian King and his party crossed the border in military uniform, they would be interned. This response was to earn Gustav the lasting enmity of King Haakon.

Meanwhile, the situation with Crown Princess Märtha was also mishandled by King Gustav. Märtha was moved on from Sälen, as it was feared her presence so close to the Norwegian border might provoke the Germans, but as to doing exactly what remains unclear. “Uncle Gustav”, after initially welcoming Märtha and her family to his home at Drottningholm (where an adjutant warned that the war was not to be discussed at the dinner table) eventually offered her accommodation at nearby Ulriksdal Palace. Interestingly, the move to his palace coincided with King Haakon learning that the Germans had informed the Administrative Council, an interim body appointed by the Norwegian Supreme Court to deal with matters of civil administration in Norway, that he should abdicate the throne. Furthermore, during this period the Crown Princess (who received little direct news of King Haakon and her husband Olav) was subject to constant political pressure to return to Norway with her son Prince Harald and cooperate with the occupying power by acting as Regent, of what would effectively be a puppet throne, until her son reached his majority. A number of prominent Norwegians who visited Stockholm advocated for such a solution. This idea also had its supporters within Per Albin Hansson’s Swedish government. For instance, the Swedish Justice Minister (and one-time Foreign Minister), Karl Westman, wrote in his diary as early as 19 June, mentioning his attendance at a government meeting: ‘I reiterated my question about why the friends of the Norwegian dynasty do not put the Norwegian crown princess and [prince] Harald on a plane and send them… to Oslo.’ He was writing this at a time when many Swedes believed that Märtha’s presence threatened to undermine Sweden’s neutrality when Germany was on the ascendance: Only a few days earlier German forces had entered Paris unopposed and the French were on the point of signing the surrender at Compiègne. Meanwhile, some Norwegians even harboured the-not unrealistic-suspicion that Prince Harald could be kidnapped and taken to Oslo by force.

King Gustav, meanwhile, was concerned to learn of the German’s desire to have King Haakon abdicate or even to depose the monarchy in Norway. He now chose to become personally involved and in a telegram to Hitler observed, ‘I consider it my duty to personally emphasize to you, Herr Reich Chancellor, that such a measure would elicit serious disapproval among the broadest circles of the Swedish people and throughout the whole of Scandinavia. I wish therefore, before irrevocable decisions are made by you, to draw your attention through this telegram…to urge you, Mr. Chancellor, to proceed with all the moderation that can be considered possible in relation to Norway, its king and people.’ Did he now fear for his own throne?

Rumours now began to circulate of a cipher telegram having been sent on 21 June by King Gustav to King Haakon to advise him to abdicate in favour of his grandson as ‘a means of saving the Norwegian people from unnecessary difficulties’. This led to confusion and it appears that the contents of King Gustav’s earlier telegram to Hitler was somehow misconstrued or misreported for, on 22 June the British Minister in Stockholm indicated that King Gustav had telegraphed Hitler directly personally recommending the Regency option to him. Thus, London (and the Crown Princess) now believed that Gustav was the principal protagonist in this “Norwegian Regency” matter. Indeed, such was the fury in London that it caused Britain’s King George VI to sit down and write a very stern letter to the Swedish King. Fortunately, this was not forwarded by the British Legation in Stockholm to King Gustav, when it became clear that in his earlier telegram to Hitler the meddling Swedish king had instead urged the Reich Chancellor to show the utmost possible moderation in his dealings over Norway. Some commentators have taken the view that Gustav intervened simply because he believed that if the matter was not resolved soon Germany would abolish the monarchy in Norway. Ironically, Hitler would interpret Gustav’s involvement as a Norwegian-inspired attempt to put pressure on Germany.

The Crown Princess of Norway and her children Ragnhild, Harald and Astrid in August 1940 as they travel through Finland en route to Petsamo.

The Crown Princess of Norway and her children Ragnhild, Harald and Astrid in August 1940 as they travel through Finland en route to Petsamo. Märtha was clearly aware of the growing danger and sent a telegram to London warning her husband and father-in-law ( who had fled there, in early June, with members of the legitimate Norwegian government) that her Swedish family (i.e. King Gustav) and Hitler were conspiring to remove King Haakon and set up a Regency. Crown Prince Olav had never felt his family were safe in Sweden and in a letter from Buckingham Palace dated 22 June, he appraised his old friend President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the situation. The President soon came to Märtha’s rescue and offered her and her children the chance to relocate to the United States as his ‘personal guests.’ They departed Ulriksdal on 12 August and sailed from the Finnish port of Petsamo (now Petsjenga, Russia) aboard the USS American Legion on 15 August. Olav’s intervention, of course, thwarted the regency option. King Gustav seemed displeased by this latest development and telegraphed King Haakon, on 24 July, stating that he objected to the American trip as it might undermine the future of the Norwegian monarchy, a viewpoint Haakon quickly dismissed.

Not content with concerning himself with Norwegian matters, Gustav V turned his hand to acting as a peacemaker between Germany and the United Kingdom. He wrote personally to Britain’s King George VI, as well as to Hitler offering his services as an intermediary for peace. What the Fuhrer replied is unclear but George VI handed a note to the Swedish Ambassador in London on 12 August which courteously but firmly rejected Gustav’s offer, pointing out that ‘the intention of My Peoples to prosecute the war until their purposes have been achieved has been strengthened’ as a result of the felonious behaviour of the Germans in the war so far.

A Swedish soldier watches over German troops being transported through Sweden in World War 2.

A Swedish soldier watches over German troops being transported through Sweden in World War 2.Meanwhile, as the above sagas were being played out, King Gustav was also faced with an even more pressing problem within days of the occupation of Norway: A German request to transport food rations, medical staff and nursing supplies through Sweden by train to Narvik in northern Norway. This port was the primary outlet, particularly in winter, for transporting the Swedish ore by sea to Germany. The Swedish government agreed to this request on 17 April. It was a decision they would soon come to regret, as over time the Germans would push for further concessions including the transport of ‘furlough troops’ and ‘destroyer crews’. This was eventually expanded to ‘arms and troops’ by the end of June.

King Gustav and Per Albin Hansson 1941

King Gustav and Per Albin Hansson 1941However, the most debated was during the so-called midsummer crisis (Midsommarkrisen) in June 1941, when Germany-who had by now reached an accommodation with Finland and was planning an invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa)-asked to transport a battle-equipped division of military personnel belonging to the Wehrmacht’s 163rd Infantry Division from Oslo and through Sweden to Haparanda, near the Finnish-Swedish border in Northern Sweden, for further transportation eastward. The Swedish cabinet was divided on the issue and was initially against granting the request, on the basis that it was a violation of Sweden’s neutrality. Heated discussions took place throughout 23 and 24 June. However, the government executed a volte-face when the Swedish Prime Minister, Per Albin Hansson, indicated that King Gustav had informed him that he could not take responsibility for a negative answer and would abdicate unless Germany’s application was granted. He also informed his brother Eugen (who notably distanced himself from the Nazi regime) that the consequences of saying no to the Germans would be serious. Although Swedish historians have continued to debate whether their monarch really threatened to abdicate, it should be noted that on June 25, the Prince of Wied had a long conversation with King Gustav. The German Minister was subsequently pleased to inform the Foreign Ministry in Berlin that Gustav had ‘expressed his satisfaction that the principal German request for the transit of one division had been accepted by the State Council and who indicated his personal support in the matter.’ Indeed, Gustav himself would later reveal ‘that it had been owing only to his personal intervention that the question of the transportation in the summer of troops through Sweden had been settled in accordance with [German] wishes.’

King Gustav V with his family during World War 2. Crown Princess Louise (left), the King, Princess Sybilla with daughter Birgitta, Crown Prince Gustav Adolf with granddaughter Margaretha.

King Gustav V with his family during World War 2. Crown Princess Louise (left), the King, Princess Sybilla with daughter Birgitta, Crown Prince Gustav Adolf with granddaughter Margaretha. The same afternoon, the first of the trains left Oslo, crossing the border into Sweden early on 26 June, and heading northwards through Sweden en route to Finland and the Eastern Front. As the train arrived at Krylbo, 15 kilometres northwest of Stockholm, the Prince of Wied was present to inspect a guard of honour in the company of his wife. The main transport commenced on 27 June with around four trains crossing into Sweden each day. In total 15,449 German troops were transported by 12 July. Meanwhile, according to Sweden’s Expressen newspaper, over the ensuing wartime years 2,140,000 German soldiers and 100,000 tons of weapons and equipment would be transported through “neutral” Sweden. It should also be noted that on 29 June 1941 cooperation agreements were made between the Swedish and German air forces; as well as between the Swedish and Germany naval forces. Gustav would later indicate to the German Minister that is had only been due to his ‘personal intervention’ that in September 1941, the German 2nd Division, had been permitted to sail through Swedish territorial waters with a Swedish naval escort, en route north to the Eastern Front. The grateful Germans continued to push for more, with Sweden’s adherence to the Tripartite Pact even being mentioned at one stage.

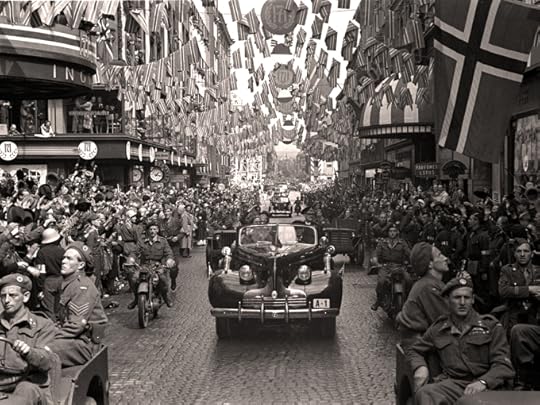

German-born Princess Sybilla visits a German Hospital Train as it passes through Sweden in November 1941.

German-born Princess Sybilla visits a German Hospital Train as it passes through Sweden in November 1941.This period sees Gustav and some of his family at their most fawning where Germany is concerned. In November 1941, a smiling Princess Sibylla, with a German army officer at her side, was spotted serving coffee and cake to a group of wounded German soldiers, travelling homeward from Norway, at the Krylbo railway station. It is inconceivable that this was done without the King’s permission; while in February 1942, Gustav would also permit a visit to Stockholm by Sibylla’s father, currently an Obergruppenführer in the German Sturmabteilung (SA). In addition, in October 1941, four months after the German invasion of Soviet Russia, Gustav attempted to send a personal letter to Hitler ‘about a matter that is close to my heart…’ i.e. Bolshevism and offering his ‘sincere thanks to you for deciding to strike at this plague..’ and congratulating the Fuhrer ‘on the results you have already achieved.’ However, the Swedish Prime Minister got wind of it and would not allow the letter to be sent. That the King was a devious operator is evidenced by what he did next: Gustav merely sent for the Prince of Wied on 28 October and read the contents of the letter out aloud to him. The Prince took notes and that very evening, the German Foreign Ministry in Berlin received a copy of the text from the German Embassy in Stockholm: ‘The King wished quite frankly to express his warm thanks to the Fuhrer for having decided to crush this [Bolshevik] plague. The King asked that his heartiest congratulations be conveyed to the Fuhrer on the great success already achieved. At the same time the King gave assurances that by far the greater part of his people shared his views in this matter. His efforts and his activities would always be aimed at converting the doubters to his views. The King also added that he was very anxious for the preservation of good relations between Germany and Sweden.’ Gustav also asked the Prince of Wied ‘to treat the foregoing communication in special confidence so that it would not become known in public. ‘ As a second cousin of Gustav’s late wife, the King still treated the Prince ‘like family’ and he was invited on summer retreats until 1943. It is no wonder that Winston Churchill now viewed Gustav as being, ‘absolutely in the German grip.’ Hitler responded to Gustav’s message, on 7 December, ‘with sincere pleasure’ and particularly mentions ‘the very personal comforting personal attitude of Your Majesty…’ in appreciating the ‘historic action’ which Germany had taken in the war against Bolshevism.

Gustav V and his government were also afraid of the Swedish press upsetting the Germans. Academics have reported that there was ‘very limited reporting’ on the Jewish question in 1940 and 1941 compared to the pre-war years. This self-censorship also extended to at least sixteen Swedish newspapers being prevented from reporting abuses in Norwegian prisons. Expressen cites a case which illustrates that the Swedish King took a personal interest in such matters. When the Gothenburg Trade and Shipping Magazine featured an article by Torgny Segerstedt (an avowed critic of Nazism and Sweden’s policy of appeasement to Hitler) which mentioned Nazi atrocities, Gustaf V summoned the magazine’s editor to the Royal Palace and urged him to stop writing negative articles about Hitler and his regime. Meanwhile, on one occasion, Hitler himself set the record straight, when in an interview with Stockholm Tidningen, in March 1944, he denied that he had made an approach to King Gustav, who had offered to mediate with Finland.

It is easy today to criticise the actions of King Gustav. However, he and his government were clearly under constant pressure for although Sweden remained unoccupied, it remained cut off from the West by German-held territory and was heavily dependent on Germany economically, including for her imports of necessities. Furthermore, the possibility of a German invasion of Sweden was ever-present. At times, the King’s intervention may even have prevented a German incursion, as when he wrote to assure Hitler that ‘Sweden will defend itself against all invaders, even against an English attack…’ This was in response to Hitler’s grumblings that Sweden would not protect itself against a British invasion thus threatening the supply of iron ore on which Germany so desperately relied. Certainly, in April 1942, Hitler decided to strengthen German forces in Norway by 70,000 men. The 25th Panzer Division was strategically stationed in Oslo and was Germany’s way of intimidating the Swedish government into continued cooperation. By contrast, with the weakening of the German military position in the latter part of 1943 onwards, Gustav’s fear of German reprisals seemed to diminish and he appeared a little more accommodating, although cynics would say that was merely repositioning himself in preparation for an Allied victory. In advance of the Heads of Government Meeting at Tehran in November 1943 some-such as the Russian Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov-were pressing for Sweden to abandon neutrality and fight with the Allies. However, the Swedish Minister in Moscow told the United States Ambassador to Soviet Russia, W. Averell Harriman, that while Sweden was ready to take ‘certain risks,’ his government was not ready to go very far and there was a regal reason :’He pointed out that it was the ambition of the King to lead his people through the war without the suffering that would come from participation.’ Meanwhile, around 7 million tons of iron ore were still being traded between Sweden and Germany in 1944.

As has been observed, Swedish wartime diplomacy sought to ward off German invasion by adopting a neutrality that sacrificed some of Sweden’s independence and made significant concessions to Germany, many backed by the King. Nonetheless, during this period, Gustav V has been credited with helping save Jews deported from Nazi-occupied countries such as Denmark by authorizing measures including the distribution of Swedish passports. Furthermore, in June 1944, at the urging of the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg and the Chief Rabbi in Sofia, Gustav sent a telegram to the Hungarian ‘Regent’, Miklós Horthy, protesting the deportation of Jews from Hungary. This examples a stronger stance than in 1933 when he apparently informed Hitler that the persecution of the Jews initiated by the Nazis would have a disastrous effect on Germany’s international reputation. The Chancellor should ‘proceed more gently.’

At the time of his 85th birthday in 1943 Gustav V made an interesting speech, which indicates his mindset during World War 2, “It is my firm opinion that a constitutional monarch under ordinary circumstances should not act as a leader in one direction or another except in exceptional cases. But during the current great world crisis, I have considered it my indisputable duty to try on several occasions to help the country out of the difficulties of the moment.” With these words, he acknowledges that he certainly had strayed in ‘one direction’ and that was certainly not in the direction of the Allies.

The author of this blog takes a keen interest on the fate of royalty during World War II. He narrates the wartime adventures of the Greek-born Princess Olga (onetime Consort of Prince Regent Paul of Yugoslavia) in Africa (and much else besides).

July 21, 2025

Crown Princess Märtha’s Regency Battle

In the early hours of 9 April, Crown Princess Märtha and her husband Olav were awakened by a phone call from an aide, bringing the devastating news of an invasion by German military forces. With her mind in a whirl, Märtha immediately awakened her three children, instructing them to dress for a mountain hike. Ragnhild, the eldest, would later recall that ‘the clearest sign that something was wrong was that it was our parents themselves who woke us up.’ After eating a hasty breakfast, at around 6 a.m. Märtha , Olav and their three children (Ragnhild, Astrid and Harald) set out from their home, some twenty kilometres to the west of Oslo, for the Royal Palace in central Oslo, in a convoy of three cars. The Crown Prince was at the wheel of his own car, his wife and children beside him. Olav-who was driving at great speed-had already decided that if anyone tried to stop him, he would run them down.

On arrival at the Royal Palace, everything was in a state of flux. The royal family departed the royal residence at 7 a.m. travelling in the direction of the Østbane railway station in order to take a special train to Hamar to avoid capture. The members of the Norwegian parliament, the Storting, were also on board the train. The group was led and organised by the President, Carl Joachim Hambro. It had been at his suggestion that the royal family accompanied the parliamentary group. Just as the train passed through Lillestrøm, the town was bombed, although the focus was fortunately on the nearby airport at Kjeller. The entourage travelled onwards towards Hamar with German soldiers and aircraft in hot pursuit.

By the early evening, the royal party had settled at an estate at Sælid, a few kilometres outside of Hamar, where they were just sitting down to dinner when word was received from the local police chief of the impending arrival of several busloads of German paratroops. This was a group led by the German Air Attache in Oslo, Captain Spiller, who was intent on seizing the King and his ministers by force. They did not reckon on the efforts of the Norwegian Colonel Otto Ruge and his men, many of whom had only completed their basic training, who manned a roadblock. Their heaviest weapon was one machine gun. Fighting tenaciously, they succeeded in mortally wounding Hiller and the Germans withdrew. Meanwhile, the King and others of the royal group immediately set out by car towards Elverum, to rendezvous with members of the government who had fled there from Hamar. It was also at Elverum that the Storting gave the King and government the authority to govern the country for as long as the war lasted (“The Elverum Mandate”). However, with so much uncertainty prevailing, a decision was made to send Crown Princess Märtha and the royal children over the border into neutral Sweden, for reasons of safety. Among those accompanying them were Olav’s trusted aide, Major Nicolai Ramm Østgaard (who would almost immediately return to his duties with the Crown Prince), his wife Ragni and their ten-year-old son Einar. Also in the royal entourage was Signe Svendsen, Prince Harald’s nurse; as well as Ragnhild and Martha’s Swedish governess Maja Thorén. Another Swedish national, the Crown Princess’s maid, Edla Norberg completed the party. The royal convoy, consisting of three cars, crossed the border into Sweden from Trysil at 00:50 hours on 10 April.

German troops parade down Karl Johan’s Gate with the Royal Palace in the background.

German troops parade down Karl Johan’s Gate with the Royal Palace in the background. The events surrounding the party’s crossing into Sweden are the subject of debate. There are two versions:. In Brita Rosenberg’s biography of Princess Astrid, the latter recounts that Swedish border guards did not want to raise the border barrier and only did so at the last minute when their Norwegian driver indicated that he would drive straight through unless they did so.

Einar Østgaard, in his 2005 book about Crown Princess Märtha, which makes use of his father’s notes and journals, takes issue with this account: ‘The claim that Crown Princess Märtha was denied access to Sweden was printed for the first time over forty years after crossing the border on the night of 10 April 1940.’ He is of the opinion that this version must be due to a misremembering. The author also cites his mother Ragni, who served as the Crown Princess’s Lady-in-Waiting, later describing an undramatic border crossing: ‘None of us had passports, but at the Swedish border station, Nikko (her husband, Nikolai Østgaard) was out explaining who it was, and there was no difficulty in getting past.’

Either way, the convoy continued to the winter resort of Sälen to stay at the well-known Högfjällshotellet, arriving at half past three in the morning. As it was a glorious sunny day and the royal children spent most of the time skiing on the nearby slopes, while their anxious mother remained at the hotel glued to the radio for news of events in neighbouring Norway. What she heard could hardly have lifted her spirits. On 10 April, the King had met with the German Minister Kurt Bräuer in the High School at Elverum. Bräuer set out the demands of his masters in Berlin: the legitimate Norwegian government must resign, and the King must appoint Vidkun Quisling of the right-wing Nasjonal Samling (National Unity) party as Norway’s Prime Minister and approve the formation of a pro-German government led by him. King Haakon subsequently presented these demands to officials of the legitimate Johan Nygaardsvold government during an extraordinary Council of State held in nearby Nybergsund (where they had relocated). The King made it clear that they must decide what course of action they wished to take, but added that he would not bow to these German demands and if the government decided to agree to them, he would abdicate. The government, in turn, fully backed the King. King Haakon’s “no” and the government’s approval thereof were formulated as a Royal Decree and signed by the King, the Prime Minister and Minister of State Bredo Rolsted. The Norwegian population were informed of the decision in a radio broadcast.

When the Germans learned of this decision (which was relayed by telephone to Bräuer at Eidsvoll by Foreign Minister Koht) , they were infuriated. The following day, Heinkel 111 bombers of the German Luftwaffe bombed both Elverum and Nybergsund, where the King and Crown Prince were sheltering, killing dozens of people. Crown Princess Märtha was subsequently relieved to learn from newly-arrived Norwegian guests at the hotel that, although shaken, both the King and Crown Prince Olav were uninjured. This news was corroborated by the hotel manager who had been in Nybergsund at the time of the attacks, in an attempt to obtain information on behalf of the Crown Princess. From first-hand reports carried in the Swedish press, it became clear that King Haakon was the key target. At one stage, he and his son Olav were forced to take shelter in a ditch to avoid being fired on by the low-flying Heinkel bombers.

Crown Prince Olav (to rear) and King Haakon literally run for their lives at Nybergsund 11 April 1940

Crown Prince Olav (to rear) and King Haakon literally run for their lives at Nybergsund 11 April 1940An early visitor to Sälen was the Storting President Carl Joachim Hambro, who was en route to Stockholm. He recalls in his memoirs arriving in time for breakfast and apologising to the Crown Princess for ‘being so unkempt and not having had time to shave.’ Märtha, clearly having maintained her sense of humour merely laughed and replied, ‘Me neither.’ He brought with him a letter written by King Haakon at Nybergsund addressed to his sister (and Märtha’s mother) Princess Ingeborg. The latter arrived at the winter resort a few days later, visibly tired and looking somewhat older, according to Ragni Østgaard. Yet, Ingeborg was also ‘filled with a glowing hatred of the Germans’ for her homeland of Denmark had also recently been occupied. Märtha’s mother was also deeply concerned for the welfare of her brother, King Haakon (formerly Prince Carl of Denmark until his accession to the throne of Norway in 1905) and her son-in-law (and nephew) Olav.

Prince Harald photographed at Sälen

Prince Harald photographed at SälenThe Swedish authorities were by now growing increasingly nervous of the presence of Norwegian royalty in an area so close to the border. What if, they reasoned, the Germans accidentally bombed the hotel due to a “navigation error” or if a kidnapping attempt was made to seize the royal party? The Swedish county governor decided to act and asked the royal party leave the hotel. In order not to attract attention, on 18 April, the royals and their entourage departed in the middle of the night, and headed southwards by car (which almost upturned in a snow drift) towards Uppsala. Thanks to Princess Ingeborg making use of family connections, it was arranged that the royal party could take temporary residence at Count Carl Bernadotte of Wisborg’s home at Rasbo. They would remain there for ten days, before proceeding to Stockholm and Drottningholm Palace.

At Drottningholm, King Gustav proved to be welcoming host but made it clear, through an adjutant, that there would be no discussion of the war at the dinner table. This was interesting, as otherwise Gustav had taken a keen interest in developments throughout Europe, with maps spread out over a billiard table nearby. However, it was noticeable that there was none pertaining to Norway. This particular map had been removed, prior to the arrival of the Norwegian contingent, perhaps out of tact. The Crown Princess tried to distract herself with games of gin rummy and bridge. Meanwhile Norwegians in Sweden were told not to openly celebrate their National Day on 17 May.

So how did the Crown Princess now continue to obtain news of what was happening across the border? Märtha acquired a quality radio set and each evening she and Ragni Østgaard would listen to the late night news bulletin from London. Perhaps Märtha even managed to tune in to the National Day service broadcast from the Norwegian Seamen’s Church in London, as King Haakon and Crown Prince Olav managed to do in a holiday chalet in Northern Norway? She also had the services of the Norwegian diplomat Jen Bull, who acted as a liaison between Märtha and the Norwegian Legation in Stockholm. Bull had previously served (1925-1931) as a Counsellor in the Norwegian legation in Berlin, rising to the rank of Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office in Oslo in 1939.

In due course, the Crown Princess was informed that King Haakon and Crown Prince Olav had departed Norway (from Tromsø) on the evening of 7 June, following a cabinet meeting held in the Bishop’s Palace, in order to continue the fight from Norwegian democracy from London. The war in Norway aside, Crown Prince Olav’s chief concern was now for the safety of his children and wife in Sweden. He had written to President Franklin D Roosevelt from Trangen, Langvatnet, as early as 10 May, mentioning an offer which Roosevelt had made, in late April 1939, during the Crown Prince and Princess’ weekend stay at the President’s country home at Hyde Park, ‘to take care of the children’ if the war should reach Norwegian shores.

After observing the 82nd birthday celebrations for ‘Uncle Gustav’ the previous day at Drottningholm, on 17 June, the Crown Princess and her children moved to Ulriksdal Palace. This allowed for some more privacy, and the children were able to relax with games, picnics and boating on the inlet. Furthermore, young Harald took the opportunity to learn to swim under the instruction of Signe Svendsen. Nonetheless, there was always a watchful Swedish policeman in attendance. Interestingly, the move to Ulriksdal coincided with King Haakon learning that the Germans had informed the Administrative Council, an interim body appointed by the Norwegian Supreme Court to deal with matters of civil administration in Norway, that he should abdicate the throne. This move on the part of the German occupiers seems to have hit a raw nerve with King Gustav of Sweden who, most unusually, became involved, sending a telegram to Adolf Hitler stating that ‘I consider it my duty to personally emphasize to you, Herr Reich Chancellor, that such a measure would elicit serious disapproval among the broadest circles of the Swedish people and throughout the whole of Scandinavia. I wish therefore, before irrevocable decisions are made by you, to draw your attention through this telegram…to urge you, Mr. Chancellor, to proceed with all the moderation that can be considered possible in relation to Norway, its king and people.’ Did he now fear for his own throne?

The sitting room at Ulriksdal Palace much as it was in 1940.

The sitting room at Ulriksdal Palace much as it was in 1940.In the interim, Berlin had appointed Josef Terboven as Reichskommissar in Norway. Despite the initial refusal of the Administrative Council to comply with the abdication request, negotiations were continuing with Terboven, who was currently focused on the formulation of a future political framework for use in Norway during the occupation. Furthermore, despite King Gustav’s aforementioned telegram, there was a genuine possibility that a powerful Germany, aided by sympathetic Norwegians, could, if necessary, use leverage against Sweden, both diplomatically, economically, and militarily, to arrange for Märtha to be returned to Norway with her son and a Regency formed until Harald came of age. A number of prominent Norwegians who visited Stockholm advocated for such a solution. This idea also had its supporters within Per Albin Hansson’s Swedish government. For instance, the Swedish Justice Minister (and one-time Foreign Minister), Karl Westman, wrote in his diary as early as 19 June, mentioning his attendance at a government meeting: ‘I reiterated my question about why the friends of the Norwegian dynasty do not put the Norwegian crown princess and [prince] Harald on a plane and send them… to Oslo.’ He was writing this at a time when many Swedes believed that Märtha’s presence threatened to undermine Sweden’s neutrality when Germany was on the ascendance: Only a few days earlier German forces had entered Paris unopposed and the French were on the point of signing the surrender at Compiègne. Time Magazine would subsequently report that Crown Princess Märtha had indeed been offered ‘a regency in the name of her son, Prince Harald.’ Meanwhile, some Norwegians even harboured the-not unrealistic-suspicion that Prince Harald could be kidnapped and taken to Oslo by force.

On 27 June, the Presidential Council of the Storting, under pressure from the occupiers and recognising the need to establish a provisional government, responded tentatively to Josef Terboven’s proposal to establish a Council of the Realm to act as a collaborative body with the occupiers. In order to progress matters, they now asked the King to abdicate, giving him until 12 July to ‘renounce his constitutional functions for himself and his house.’ However, King Haakon refused to comply and, on 8 July, announced his rejection of the abdication request via a BBC radio broadcast from London, as well as formally placing his response in writing. What would this mean for the future of Norway and the monarchy going forward?

In Stockholm, Märtha, under the impression that her Swedish family (i.e. King Gustav) and Hitler were conspiring to remove King Haakon and set up a Regency, was feeling the pressure and sent a telegram to London as early as 24 June warning her husband that attempts were being made to ‘induce her’ to return with her three children to Oslo. Indeed, rumours had been circulating of a cipher telegram having been sent on 21 June by King Gustav to King Haakon to advise him to abdicate in favour of his grandson as ‘a means of saving the Norwegian people from unnecessary difficulties’. It also appears that the contents of King Gustav’s earlier telegram to Hitler may have been misconstrued or misreported for, on 22 June the British Minister in Stockholm indicated that King Gustav had telegraphed Hitler directly personally recommending the Regency option to him. Thus, London (and the Crown Princess) now believed that Gustav was the principal protagonist in this matter. Indeed, such was the fury in London that it caused Britain’s King George VI to sit down and write a very stern letter to the Swedish King. Fortunately, this was not forwarded by the British Legation in Stockholm to King Gustav, when it became clear that the meddling Swedish king had instead urged Hitler to show the utmost possible moderation in his dealings over Norway. Some commentators have taken the view that Gustav intervened simply because he believed that if the matter was not resolved soon Germany would abolish the monarchy in Norway.

Despite the strong political pressure placed on her, according to Einar Østgaard’s book, Crown Princess Märtha did not particularly want to travel to the United States. However, King Haakon and Crown Prince Olav, fearing for Märtha and the children’s safety, seemed keen that this should happen. In late June, the Crown Prince had written again to President Roosevelt from Buckingham Palace pressing him to make good on his offer of sanctuary to his children, but this time he also included a request on behalf of his wife. Olav also made an approach to the US Secretary of State via the US Ambassador in London, Joseph Kennedy, entreating ‘if there is anything you can do in a hurry to get the [Crown] Princess out [of Sweden].’ On 12 July, the US Secretary of State sent a message to the US Minister in Stockholm saying that President Roosevelt was arranging for a naval transport vessel to be sent to Finland to evacuate the Crown Princess and her family, along with a group of ‘stranded’ US citizens.

On 17 July, the Norwegian Government-in-exile addressed a letter to the Storting Presidential Council, in which cautious appreciation of the work done by the Administrative Council was combined with a plain warning that ‘everything which is agreed or done at this time in respect of government in Norway must have the clear stamp of temporariness, if nothing is to be lost for the future of the country.’

On 18 July, Märtha received a telephone call from the Norwegian Minister in Washington, Wilhelm Thorleif von Munthe af Morgenstierne. He informed a somewhat nonplussed Crown Princess (who seems to have been in the dark about Crown Prince Olav’s recent correspondence with Roosevelt) that an American warship was being sent to Finland to transport her and her children to the United States. But would she go? On 20 July, Märtha received the US Minister to Norway, Mrs Florence Harriman, who was now ensconced temporarily at the United States Legation in Stockholm. Having had time to reflect on the efforts being made on her and her children’s behalf, both in London and Washington, the Crown Princess indicated to the American that she would be happy to accept President Roosevelt’s kind offer. Nevertheless, Märtha was keen to emphasise that she wanted to enter the United States ‘as quietly as possible’ and that she ‘would not be required to meet reporters or a reception committee’. Naively, the Crown Princess even expressed the hope that the date of her arrival should be kept confidential. King Gustav, on hearing of the “American plan”, telegraphed King Haakon, on 24 July, stating that he objected to the American trip as it might undermine the future of the Norwegian monarchy, a viewpoint Haakon, who deeply resented Gustav’s meddling, was quick to dismiss. Some sources also have Crown Princess Märtha and “Uncle Gustav” having a robust exchange of views on this matter in Stockholm.