Larry Gottlieb's Blog: The Insights Blog

April 25, 2025

Further Conversations on the Insights Blog

Dear Friends,

I have as of this writing shifted posts of my new writing to the substack platform. In a time of declining trust in, and readership of, traditional media, substack is an example of a new media order. This new order is a place where the power is distributed among the many instead of the few. I hope you will continue to enjoy my writing, and that of many others, in a system that rewards integrity, that is powered by relationships instead of attention, that redistributes ownership and power. To find it, click here.

Sincerely,

Larry Gottlieb

January 16, 2025

A Conversion about the Observer Effect

I recently had the opportunity to appear on Exus the Podcast, interviewed by the host, Bryan Marcus. The requested topic was The Observer Effect in the Context of Consciousness, a reference to a post I uploaded on this blog in June 2022. I’ll upload a link to the interview on YouTube as soon as it’s available.

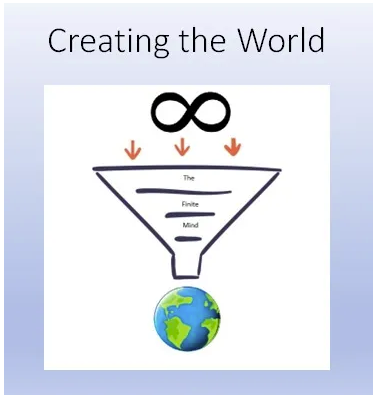

By way of background, I have written on this platform and on my website about the idea that the world we experience is not billions of years old, as is commonly thought. Rather, it comes into being moment by moment as a result of interpretation of sensory input.

Wait… isn’t the evidence for the Big Bang incontrovertible? Yes, I think so. But we don’t experience that world, the one that began 14 billion or so years ago, the one that started with a bang, underwent ‘inflation’, expansion, and so on. That’s a story, a model that fits what we’ve been able to observe. The world we experience is the one we’re perceiving right now, in this present moment, using the input from all of our senses.

I will begin this article by quoting from my original post, followed by selected questions from the host along with my answers.

The observer effect in the context of consciousness“How, then, does the “observer effect” show up when the world of objects is recognized to be the result of an interpretive process?

“The default or classical understanding of the observer effect is the phenomenon of changing the situation from the way it was before being observed to something different. But when the world and all its components are viewed as the result of interpretation by the observer, the observer effect is no longer an agent of change but rather an agent of creation. The observer brings the world he/she is experiencing into being through interpretation. There is no situation prior to its observation, and therefore there can be no effect on the situation in the usual sense.

“This inversion of the relationship between the world and the observer has numerous benefits. Psychologically, it puts the observer in a position of personal power with respect to the world of one’s experience which is unavailable in the classical view. Most of us have found that changing the world is difficult at best. However, interpretations can be changed or replaced, and thus the world as a product of interpretation can be changed as well.”

The questions and answersDo Things Exist in the Universe If They’re Not Observed?

In depends on what we mean by “things.” If we mean objects that are distinct from their surroundings, my answer is no.

If we mean fields, or possibilities, my answer would be yes. If we mean the world as something mysterious that we don’t have direct access to, again yes, but not in the way we think about objects. Those objects exist as vibrational or probabilistic possibilities. Or, you could say they exist as ideas.

Let’s step back a bit. When we were taught our native language, we didn’t realize that we were also learning a story about, or a description of, the world. It’s a story about what the world is, how it works and how to deal with it effectively. As we grew and became more independent, we internalized that story and began a lifelong process of retelling it to ourselves, often with embellishments and with increasing complexity. In the process, we forgot that the story, the description of the world, is something we learned. We forgot that the description is, in effect, superimposed over our perception of sensory information in the same way that boundaries are superimposed over topological information to create a map.

Bryan Marcus refers to the koan that goes, “If a tree falls in the forest, does it make a sound?” A more interesting question to me is, “If all sentient creatures somehow disappeared, would there still be a planet, revolving through space and time around a star?” We all “know” the answer to that question… right? Well… read on.

Tell us about the connection of your thesis, if any, to Biocentrism per Robert Lanza. Do you go this far?Here are some quotes from Lanza:

“Life is not an accidental byproduct of the laws of physics” - Robert Lanza

I couldn’t agree more!

“The whole of Western, natural philosophy is undergoing a sea change again, increasingly being forced upon us by the experimental findings of quantum theory” - Robert Lanza

I doubt that quantum theory is forcing any kind of a sea change in natural philosophy. Most physicists seem inclined to ignore the quantum enigma entirely. Instead, I would say the “sea change” is being forced upon us by the inability of our current descriptions of the world and ourselves to allow us to live lives full of joy and fulfillment.

“[Biocentrism] will release us from the dull worldview of life being merely the activity of an admixture of carbon and a few other elements; it suggests the exhilarating possibility that life is fundamentally immortal” - Robert Lanza

I agree, and I find this inspirational!

Tell us about the connection, if any, to the work of Donald Hoffman. Do you go this far?Here are some quotes from Hoffman:

“Consciousness causes brain activity and, in fact, creates all objects and properties of the physical world” - Donald Hoffman

Yes, I’m saying that consciousness is the source of all objects in the physical world, and this includes the brain and the body it is part of!

“Some form of reality may exist but may be completely different from the reality our brains model and perceive” - Donald Hoffman

Some form of reality does exist. The world is not imaginary. However, it’s unknowable, mysterious and magical! In that sense, it is entirely different from the reality our brains model and perceive.

“The causal notion of non-sentient matter developing into sentient beings is open to question” - Donald Hoffman

That notion is not just open to question; it’s completely untenable. The causal notion of non-sentient matter developing into sentient beings is imaginary. It exists because of our commitment to at least two ideas. First, that the world is senior to who we are (in other words, that it continues to exist while we come and go). And second, that all that we perceive, including the presence of sentient beings, is the result of the world evolving according to the principles of physics. These two ideas, and others, keep us locked into descriptions of the world and ourselves that virtually preclude us from living fulfilling lives.

What evidentiary basis is there for the “observer as creator” thesis?Personal experience is the only domain in which this evidence can be gathered. If the world we experience is a product of interpretation, evidence in the classic sense would have to be collected from outside the system of interpretation, and there’s no way to get there. We have only our interpretations of sensory information. There is no other place to look for information about the world.

Beyond that requirement that we stay within personal experience to answer this question, we can conduct a scientific inquiry into what factors influence what we wind up observing. My inquiry has suggested that our attitudes, opinions, beliefs, and what we can accept as being real all affect what we observe. Those factors are all within our control. Then, if we change one or more of those factors, we may see a change in what we observe. That would be powerful evidence that we are in fact creating the world of our experience through observation.

As counterpoint… what is the evidentiary basis for an external world independent of our observations of that world? Our bodies can be viewed as a special type of virtual reality headset, but a headset that’s generating input to our brains representing all of our senses instead of just sight and sound. Our brains create pictures out of this sensory input, and our bodies and minds react accordingly. The only way to know that you’re wearing a virtual reality headset is to take it off, and in the case of our bodies, we can’t do that!

What is the experimental evidence for “quantum weirdness” effects showing up in the macro world setting?

First of all, “quantum weirdness” is weird only because it violates common sense, or “what everybody knows.” But “what everybody knows” has been proven wrong over and over again in human history. See flat earth and geocentrism.

We could say that experimental evidence for experiencing “quantum weirdness” would include what our collective culture would call ‘miracles’. Our written and oral histories, including our cherished religious texts, are full of stories about these miracles. I experienced one myself in answer to a long-ago fervent prayer.

There are instances in which my wife and I clearly have the same thought at the same time with no conversation occurring. Is that telepathy, or is it the quantum weirdness called entanglement (i.e., she and I behave sometimes as if we are one thing…)?

What are some features of the reality/consciousness connection?Consciousness is the container in which everything else exists. It always was, is, and always will be. Knowing that consciousness creates our reality makes reality increasingly fluid and under our conscious, deliberate control (the only real control we’ll ever have).

Consciousness is infinite, in that it is not limited by time or space or the need to be contained in a physical body. If consciousness perceives scarcity and lack, inevitability, or no-solutions, it is our observations, conditioned by the factors such as beliefs I mentioned earlier, that produce those perceptions. There is no scarcity or lack of consciousness, nothing is inevitable for consciousness, and because consciousness is infinite, there is never a situation in which there are no solutions.

Is there a line between the quantum and classical worlds?That is, what causes “creation” in the quantum realm - - what causes a quantum entity that is in a superposition to “snap” into a single, real/classical thing? Is it observation in the first place? If not - what does that say about the Observer Effect as applied to the macro world?

The Measurement Problem in general

The measurement problem is the name given to the enigma that an observation of a system in superposition (composed of many possible outcomes of a given experiment or observation) causes one of those possible realities to become real and observable. In most interpretations of quantum mechanics, this is referred to as the ‘collapse of the wave function’. Is that what happens? What could cause that? There is no widespread agreement on these questions, even after over 100 years of successfully using quantum mechanics to design all manner of technologies from transistors to GPS to cell phones.

Various interpretations of quantum mechanics

The so-called Copenhagen Interpretation:

“Shut up and calculate” – avoid the whole issue of what quantum physics means.

Decoherence (environment) (H. Dieter Zeh/Wojciech Zurek) and

Decoherence (Killing Horizons) (Daine Danielson)

Decoherence theories explain the loss of superposition by citing the interaction between the micro-scale superposition and the larger environment, including the apparatus used to detect the superposition.

Explanations of how decoherence allows classical measurements to arise from quantum systems seek to explain the quantum enigma, or the wavefunction as a real entity. However, it’s the enigma itself that offers the most powerful lessons.

The urge or compulsion to eliminate enigma or mystery in the physical world blocks magical and mysterious experiences. It overemphasizes rationality over intuition, i.e. listening with the heart or “gut.” Rationality is very useful in certain problem-solving domains, but I would argue that it fails miserably when we use it to try to answer questions about how to live fulfilling lives.

Many Worlds (Hugh Everett)

The world is made up not of particles but of fields, or possibly one field, which I like to call the quantum field. Each ‘fundamental particle’ (electron, proton, etc.) corresponds to a particular vibrational mode of a field. The perception of “the world” is a function of tuning to one vibrational frequency or channel, much like happens in a television set. Another way of saying that is that we tune ourselves to a particular reality among uncountable others by choosing our beliefs, attitudes and what we are committed to.

Hidden Variables (David Bohm)

‘Hidden variables’ postulates an invisible phenomenon like a ‘pilot wave’, a supposed hidden agent that guides the path of each particle. Again, this can be viewed as an unnecessary complication that has so far eluded detection.

What is the source of consciousness, or the source of the observer?There is no source of consciousness. It just is. An observer is an individuation of consciousness with a particular point of view, and consciousness itself is the source of the observer.

What is the impact of the Observer Effect, or the “Observer As Creator” thesisA. Theoretical - Does it solve mysteries of the universe/reality?

Solving the mysteries of the universe… that quest undertaken with rationality is likely to remove the possibility of magical experience. The ‘observer as creator’ idea is an alternative to the classical understanding of the world as real, external and permanent, while we observers (humans) come and go. It is an explanation of what we perceive that restores to us our agency, our freedom to create, our ability to live in joy and satisfaction no matter what anyone else is doing, thinking or feeling.

The Double Slit Experiment

Demonstrates the wave nature of matter, interpreted as proving that the world exists in a superposition of multiple possibilities until one of them is observed.

Entanglement

Entangled objects behave as one entity, even if they are entangled and then separated by arbitrarily large distances. Physicists’ consistent demonstrations of this property of quantum systems means either that instantaneous communication is possible across distance (thus violating special relativity), or objects aren’t really separated. In that case, separation would then be simply an idea or a projection.

The Uncertainty Principle

Correlates with the quantum enigma and allows for unexpected experiences. It is also consistent with the mysterious nature of the world in that it shows that the world cannot be completely known.

B. Practical - How would adoption of the thesis impact peoples’ lives?

To sum up, the world is magical and mysterious, it’s awesome and unfathomable. It is our certainty that we already know what the world is and how it works that blinds us to the magic and the mystery. Our certainty blocks the awe that we could feel in experiencing the wonder of it all. And our belief that we can fully understand the world deprives us of the joy of appreciating its mysteries… especially the mysteries about ourselves.

The observer gives rise to the world and not the other way around. This inversion of the relationship between the world and the observer has numerous benefits. Psychologically, it puts the observer in a position of personal power with respect to the world of one’s experience which is unavailable in the classical view. Most of us have found that changing the world is difficult at best. However, interpretations can be changed or replaced, and thus the world as a product of interpretation can be changed as well.

January 2, 2025

Living into the Looking Glass

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, Alice climbs up onto her fireplace mantel, pokes at the wall-hung mirror behind the fireplace and discovers, to her surprise, that she is able to step through it to an alternative world where everything is reversed. That reversal tells her that she is, in fact, in an alternative world. And, she knows that alternative world exists in contrast to the normal one she remembers perfectly well.

We, too, have entered a looking-glass world. The difference is, we don’t remember the “normal” world. We entered the mirrored world so long ago it seems to us perfectly normal.

By John Tenniel - Through the Looking-Glass, Public Domain

In order to understand what is meant by a mirrored world, we have to first examine what we mean by “the world.”I know, that’s a very strange thing to say!

Examining the meaning of the term ‘the world’ is an inquiry that is, to say the least, almost never conducted. We all know what we mean when we refer to the world. It’s what we confront when we open our eyes in the morning. You know, it’s what we took our leave from when we went to sleep last night and what we return to, grinding or humming along (depending on your outlook on it) when we awaken. Right?

We “all know” that the world is permanent while we transients come and go. We are convinced that the physical world is senior to us, in that it exists much as it appears to us, whether or not there is anyone or anything around to perceive it. This relationship between the permanent and the transient is part of the worldview we all subscribe to; it’s almost never questioned.

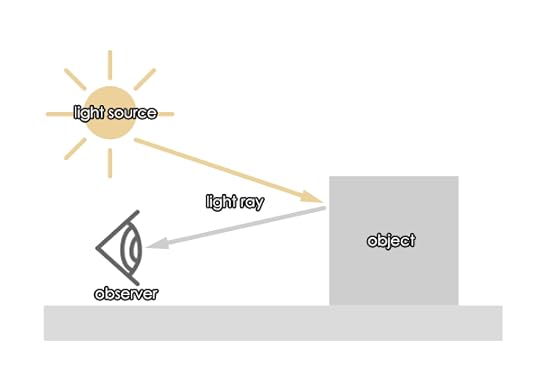

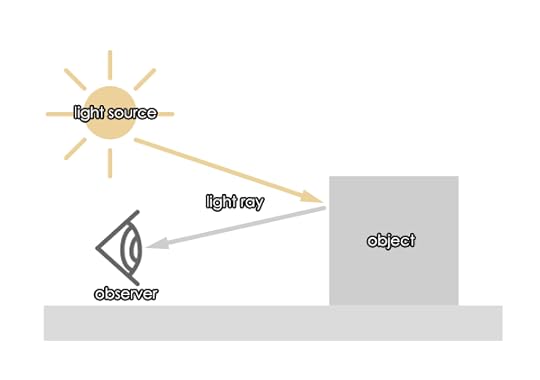

However, let’s look more closely at the idea that the world is senior to us. Consider the part of perception we call vision. The story we’re told is that light is emitted from some electrical process or from the sun, that it then bounces off some object and this reflected light enters our eyes.

From there, the electrical impulses generated in our retinas by the light impinging on them are transmitted to our brains by the optic nerve. Our brains then create pictures from these impulses, and all of us assume that these pictures represent more-or-less accurately the object which reflected the light.

So far, so good.

Does this story satisfy the scientific method?In science, a story such as the preceding explanation must be validated by observation in order to be considered a tenable idea. A hypothesis must be tested. That’s the scientific method in action. But there’s a problem here: there is no apparent method by which we could prove or otherwise demonstrate that there are in fact objects “out there,” independent of our perception, that we are perceiving.

In our Western culture, at least, we are accustomed to watching our television shows and knowing, at some level of sophistication, that a camera recorded whatever it was aimed at, the data it recorded is transmitted to the TV set and interpreted by an algorithm, and finally the image created by that algorithm is projected on a screen.

But now we have moved into an era in which CGI, or computer graphics imagery, can create that image from scratch without benefit of any collection of objects at which to point the camera. And those who wish to prove the authenticity of an image must find a way to distinguish between a real photo or video and what’s now called a “deepfake.” According to Wikipedia, “while the act of creating fake content is not new, deepfakes leverage powerful techniques of machine learning and artificial intelligence” to manipulate or generate visual and audio content that can more easily deceive.

So, are we being deceived when we perceive the world?Let’s inquire further into the nature of those pictures our brains generate from the raw material of electrical vibrations in the optic nerve. First of all, we know that our brains are capable of generating those images without benefit of any electrical vibrations in the optic nerve… that’s how dreams work. Second, we have likely all experienced that there are variations among the images brains create from those vibrations when more than one of us is viewing the same scene. These variations range from “it’s green…” “no, it’s blue” to different accounts of some event described by people who are each convinced they’re “telling the truth.”

It seems clear to me that the pictures we’re talking about amount to interpretations of the incoming data. And, interpretations are generally influenced and conditioned by belief systems, opinions, perceptual bias, and maybe what we had for lunch.

What’s really going on here?Let’s see what happens if we accept as a premise the idea that all we have is the pictures in our brains and that we have no way of verifying that they represent more-or-less accurately an external world that exists “out there” somewhere.

We “all know” that when we act in some way, we are looking out at the external world and attempting to use our actions to change something. We’re looking to rearrange objects or change them in some way, assemble some objects and disassemble others. I call that living out into the world.

But what if that which you’re looking at right now is a picture in your brain? In that case, you are living into that picture; you are attempting to change something in that picture!

Now, add to that the idea that your interpretations, the ones that form the pictures in your brain, are conditioned by your beliefs and your opinions. You’re interpreting electrical impulses according to a very complex algorithm, an algorithm that is not only shaped by the design of human perception, however that works. The algorithm is also shaped by what your parents told you, what you read, what others tell you, and so on. That entire complex algorithm is what we call ‘perception’.

Your perceptions reflect your opinions and your biases. In fact, once you accept the truth of that statement, you can use your perceptions as if they constitute a mirror to identify and, perhaps, even correct your biases.

Now, since our perceptions reflect our beliefs, the world we perceive (remember, it’s just a picture in this argument) serves as a looking glass. So, when we act, we are living “out” into the looking glass, into the reflection we see in the world.

Yes, we are interpreting electrical impulses that in some way are related to the “real world,” whatever that might be, but we have no way of interacting with that world directly. For us as human beings, equipped only with our five senses, our interpretation, our description of the world, always stands in between ourselves and that world.

My promise to you is that if you decide to treat the world you experience as if it reflects your beliefs, you will find yourself recovering the power you gave away when you had to depend on bigger people for your every need when you were young. You’ll find yourself back in the driver’s seat of your life. You’ll discover yourself as a creator of worlds, specifically the one you’re looking at right now.

January 27, 2024

The End of Common Sense

Twentieth century physics represents a profound turning point in the history of science. It marks the time when we as a culture had to leave behind the comfortable world of common sense, where physics agreed with and supported what “we all know” about the world.

From simisi1 on Pixabay

Dear reader,

In the interest of reducing duplication, the rest of this post can be found on my Substack at:

The End of Common Sense - by Larry Gottlieb (substack.com)

Thank you for reading my work, and please subscribe on that platform.

January 9, 2024

What Does Quantum Theory Mean?

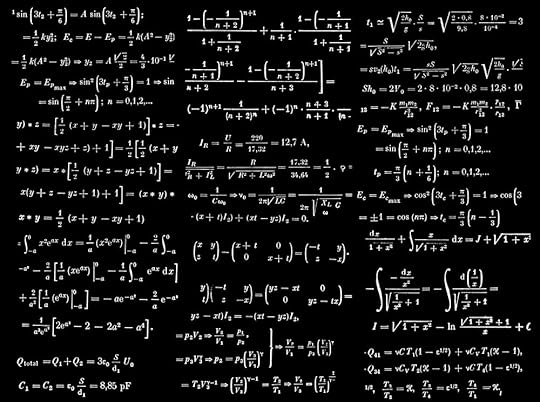

For most of us, quantum physics is mysterious and unfathomable. When shown a blackboard full of symbols, our eyes tend to glaze over.

Photo by Dan Cristian Pădureț on Unsplash

For people who actually work with the theory, things aren’t much better. They’ve been trying for a century to understand what the theory tells us about the world we live in without much success. One cliche often used to describe this mysterious quality of quantum physics is, “shut up and calculate.”

That’s actually good advice for most engineers. The theory allow us to design our age’s most powerful tools, from the transistor to the cell phone and beyond. Never mind that it also tells us that the supposed building blocks of the world, the fundamental particles, don’t have definite values, such as position and momentum, until they’re measured.

I contend that quantum physics shows us that the world we experience is fully dependent on our observation of it. It believe it further shows us that the independent reality of the world we experience (i.e. independent of us) is an illusion.

If that were true, it would follow that our strategies for living are rendered obsolete by this understanding. Our cherished strategies for getting along in life are all dependent on the idea that the world is an “is.” An “is” is something that appears to us as it actually is, and is something that would be that way whether or not there is somebody around to observe it. According to quantum theory, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

This begs the question, “What does this mean for human beings?”Ruediger Schack, in the online publication The Conversation, has pointed out that “The starting point for most philosophers of physics is that quantum mechanics must somehow provide a description of the world as it is independently of us, the users of the theory.”

Quantum physics, I believe, flatly denies this interpretation. Instead, it describes the world as a field of weighted possibilities (i.e. probabilities) for the results of any experiment that will be performed on the world. Quantum laws are all about the results of observations. As far as we know, they do so with complete accuracy.

But right there, physics is inseparable from consciousness. Isn’t it meaningless to talk about the results of experiments or observations without implicitly referring to the conscious being that’s doing the experimenting?

Quantum theory further shows that any attempt to measure or observe any part of the world causes the field of possibilities to collapse into the one possibility that is actually observed. But then, after the measurement is complete, the field somehow resumes its probablistic nature before the next observation.

There have been many attempts to interpret this finding, none of which is truly definitive. For a century, physicists have argued about how observation of a system can cause one possibility to emerge from a field of possibilities when the laws of quantum physics contain no mechanism for this emergence.

Since we always start from the assumption that the world exists independently of us, once we encounter quantum theory as a description of probable outcomes of experiment, we assume that these probabilities are somehow inherent in the physical system we’re observing. Yet, a century and more of theorizing has yet to provide a mechanism that yields these probabilities.

I believe that the most plausible resolution of this quandary lies in the following recognition.The world we experience is actually a picture formed in our brains by interpretation of sensory data. That is, what we think of as the external world is in reality an interpretation of the data our brains receive via our sense organs, and all such interpretations are conditioned by past experience, trauma, memory, and many other subjective factors.

Equipped only with our sensory apparatus for inquiring into the world, we have no way of getting outside of these interpretations and observing the external world directly. The “real” world, assuming there is such a thing, is thus unknowable.

How does the probablistic nature of quantum theory show up in this description?

One possibility is that we could interpret our sensory data in many ways, the most probable of which is in accord with what our culture has taught us, what “everybody knows,” common sense.

When we look at the world as an interpretation of something that is in itself essentially unknowable, optimizing our experience is no longer about solving problems or trying to change conditions. Instead, it is about crafting our interpretations to optimize the quality of our experience.

Another of our culture’s profound illusions is that the resources required for our physical and emotional wellbeing are limited. That would be true if the world were “real” in the scientific sense. The definition of “real” in physics is that “objects have definite properties independent of observation.” The 2022 Nobel Prize in physics was in part awarded for the demonstration that this is not the case, that the objects composing the world do not have definite properties when they are not being observed. We are interpreting signals that represent something, but that something is not the objective reality we think it is.

To summarize: The world we experience is the product of interpretation of something which is itself unknowable. Scarcity, the limits we believe apply to the available supply of physical stuff, is part of this interpretation. The field of possibilities we are interpreting is not limited; that field is infinite. In other words, interpretation as a phenomenon is not limited unless belief places a limitation upon it. To the degree to which I free myself from a belief in limitation, I am free to interpret the field of possibililties so as to optimize the quality of my own experience.

This argument shows, I believe, that so-called zero-sum games are artificial. Zero-sum games are systems in which what one gains another must lose. Again, that would be true if the world were “real,” if the stuff of the world were limited.

Believing in the finiteness of resources is required for zero-sum games. And this belief is the source of most, if not all, of our human misery. Ultimately, we fight over scarce resources: territory, wealth, and ideas which are themselves based on scarcity, such as markets, political and other arguments.

As I endeavor to see the world as it really is, waiting for me to observe it and thus make it real, I find…I no longer believe in the finiteness of any of that which is required for the most joyful and satisfying experience of life.

In order to see the world as it really is, I find I must relinquish the habit of describing it incessantly. I find I must quiet the internal dialog that constantly interprets the world according to my needs, fears, and desires. Obviously, that’s been called “Be Here Now.” And in the right-now, the experience is complete and satisfying.

If I’m not experiencing satisfaction right now, it’s not because I don’t have the world, the sum of its building blocks, in the right place at the right time… it’s because I’m not experiencing being “right now!”

That’s hard to hear, isn’t it?

January 5, 2024

Why Haven’t We Destroyed Ourselves yet?

While traveling in Guatemala in 2022, my wife and I had the opportunity to attend a Mayan cacao ceremony. There were about 25 of us, arranged in a circle on the floor. She and I were easily twice as old as the rest of our fellow attendees.

After some prayers and readings and drinking more unsweetened cacao than I ever imagined consuming, the leader of the ceremony told us a story about this time in human evolution. To the best of my recollection, this is what she said.

“During the period we refer to as the Second World War, those on the other side became concerned that this human experiment might entirely self-destruct. Some older souls chose to answer the call… to come forth into human form and hold the possibility of love and light on Earth.”

She particularly emphasized the dropping of the two atomic bombs, the first on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the second on Nagasaki on August 9. She looked around the room and her eyes gazed into mine.

She said, “You appear to be the eldest of the group. When were you born?”

I answered, “I was born four days after Nagasaki.”

She said, “You were part of the first wave. You, and others after you, came forth to hold that space of possibility through some relatively dark times.”

That conversation had a profound impact on me. Those of you reading these words can, if you choose, consider yourselves part of the first few waves of souls who are here on Earth to lift us all up, to participate in what has been called the Ascension.

This lifting up requires the exploration and ultimately the discarding of our culture’s profound illusions. Observing recent as well as current events, I am compelled to conclude that such exploration requires seeing our illusions and their consequences ‘up close and personal’.

A list of those profound illusions would include, but not be limited to:

There are good guys and bad guys, good countries and bad countries

The resources required to live a good life are finite, limited, and therefore we must participate in zero-sum games

The universe is “local” - objects can only be influenced by their surroundings and such influence can’t travel faster than light

The universe is “real” - objects have definite properties independent of observation

Lifting one another up… what does that look like? A traditional way of looking at that phrase would imply speaking, or more technically, languaging, which can show up as speaking, writing, creating programs, and so on. It looks like somebody influencing another through words and actions.

Languaging, in turn, nearly always conjures putting something out into your surroundings. This idea rests on top of our belief that the universe is “local” - that we can only influence another by being part of their surroundings, and this influence must obey the realities of time and space.

But wait - I listed locality above as one of our culture’s profound illusions. What’s my justification for doing that?

Well, it’s the basis of the 2022 Nobel Prize in physics! That prize was given to three physicists for experiments that demonstrated the reality of quantum entanglement. Quantum entanglement shows that the idea that we can only influence objects, i.e. other people, through their physical surroundings is an illusion.

I propose that there is a profound implication inherent in this finding. The implication is that we can influence other people in ways that do not require obeying the usual rules of time and space, physical languaging, and so on.

I further propose that we live in a sea of illusions which obscure our true nature as creators. Any one of us who carries the knowledge of this condition, and who chooses to regard the world as our mutual creation, uplifts the entire world. That’s what the first few waves of souls emerging in and after 1945 are here to do. We are here to serve as guard rails, keeping the entire human experiment from going entirely off the rails.

It’s a profound responsibility we carry, to fulfill the purpose for which we’re here. It’s also a path of fulfillment and joy.

August 17, 2023

On Making the World a Better Place

From Ben White on Unsplash

One of the readers of this blog is a very long-time friend, whom I’ll call M. M. wrote the other day with the following message:

“I just read your new post. As long as you concentrate on the quantum stuff, you leave me in the dust. I’m anxious for you to get to the part where you suggest how we can alter our perception to make our world a better place.”

M. has a great point.

My emphasis on ‘the quantum stuff’ comes from a couple of places. First, that’s my educational background. And second, I’ve found that field of study a useful frame of reference in grasping the ideas I present in these writings.

However, if we don’t find the ideas themselves useful in enhancing the quality of life for ourselves, our loved ones, and the world at large, they’re really just another game.

So, let’s address M.’s request. The first issue is our understanding of perception and how we might be able to alter it.

Here’s the definition of perception as presented in Wikipedia:Perception (from Latin perceptio 'gathering, receiving') is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment.

In our cultural understanding, the word ‘perception’ conjures the idea that there exists an environment, a real, tangible world about which we receive sensory information and which information we can use to understand that world. All of us assume that what we’re perceiving exists pretty much as we see it. In that sense, perception is a mostly passive process of gathering information about something that would be the way it is whether or not any of us are around to perceive it.

What might be the possibilities in altering our perception of the world in that context? We could gather more information by working harder and longer. We could gather better information by increasing the sophistication and accuracy of whatever methods we use to gather it. We could gather different information by looking for other aspects of what we’re studying. (An example of this last point would be looking out at the physical universe at different wavelengths, such as the infrared spectrum that the James Webb Telescope is designed to view.)

I would argue that we humans have been doing that more-better-different thing for quite some time now, and as M. suggests, the world still needs to be a much better place.

So, how else might we look at our world?How, indeed, might we alter our perception to bring into view some other approach than more-better-different?

There is a principle called Occam’s Razor, attributed to William of Occam (c. 1287-1347), which suggests that in explaining a thing no more assumptions should be made than are necessary. This is often stated as “the simplest explanation is probably the correct one.”

The simplest alternative approach to the world’s ills is to stay out of the future, which is arguably entirely conceptual, and bring the question into the present. If we do that, the question becomes “how do we make the world better?" It’s interesting that you can read that question in two ways. It’s usually heard as “how will we make the world better,” which puts us in the future again. The other way is to assert that we are already making the world better and we’re doing it now. In that context, the question is about what we’re doing now to make the world a better place.

How are we making the world better now?By being authentic, by insisting on focusing our attention on the journey towards the highest good of all, by sending love to all who want and need it. All of us have the capacity to do that. But how can that possibly be enough?

I have argued consistently in my writing and speaking that we create our own reality. When I try to explain that experience to people, I usually wind up in the quantum realm, and as I stated at the outset, I am deliberately not going there in this piece.

And yet, most of us will agree that we do have an influence on others through our vibration (read ‘mood’, ‘attitude’, or whatever sounds less technical). Whenever we are experiencing joy and satisfaction in our lives, we uplift others. Then, of course, there’s a multiplier effect wherein each of those we’ve uplifted proceed to uplift others.

The power of staying in the present moment is the key.As soon as we mentally delve into the future, we find ourselves in a place where we have no power. There are way too many unknowns in the future to know what to do to make things better. The entirety of our power to change things lies in the present.

Which begs the following question: what is our power to change things in the present? How does being in the present change things for the better?

From stux on Pixabay

My friend M. has what might be called a sunny disposition. I know M. to be committed to looking at the bright side of things, both in the here-and-now and in the future. It may be that the only thing that keeps him from knowing that he’s making all the difference he’ll ever need/be able to make is our cultural insistence on trying to change things using more-better-different. And that’s true for all of us.

Instead of relying on more-better-different, try looking at all the world’s actors as fully capable, whole, complete beings who are having a human experience.

Like consummate actors, there are an infinitude of possible roles to play in the human drama and they all require great skill and commitment. If you look at the world from there, you can appreciate the present moment to such a degree that you can release both the past and the future. And then you may find that in the present, all the worry and angst vanishes. Those concerns live in the future, which doesn’t exist except in the human mind. In the present moment, there is only love, for the world and all who play out their roles in the human drama. And it turns out that acting out of love in the present moment is enough.

August 3, 2023

Sometimes We Feel Powerless

What do you feel when you look at the morning’s headlines or listen to a news broadcast? Does what you see make you afraid? Angry? Tired? Bored?

From Geralt on Pixabay

Looking at my own experience, what underlies any and all of those reactions is the feeling of powerlessness. My mind variously describes this feeling as, “it’s a big world out there, and I’m just ‘little me’” or “Most of what I see is out of my control” or even “The best I can do is learn to allow it to be, to enter my awareness through the front door and exit out the back.”

I do feel that powerlessness. It’s a regular feature of my emotional landscape. But what if powerlessness is an illusion? What if I’m just so accustomed to looking at the world that way that it doesn’t occur to me that there might be a another, better way?

“That’s interesting,” you might say, “but I have to go to work. I’ll think about that later.”

I don’t blame you for saying that to yourself. After all, you do have more pressing things to think about.. right?

However… suppose you were to calm down, sit comfortably, quiet your mind, and be the witness, the observer of all that goes on inside you. Suppose you were to cultivate that ability in yourself to the point that you could observe your thoughts instead of thinking them?

From Geralt on Pixabay

Here’s what I think you’d observe. I think you’d watch very familiar patterns of thought play out in your mind, patterns which have over the years of your life increased in sophistication and complexity but maintained the same themes. You might become able to recognize those themes. They might sound like:

“It’s not my fault.”

“They’re not playing fair.”

“They have so much and I (or the rest of us) have so little.”

“They’re so stupid.”

I hear thoughts in “my head” that sound a lot like that. I also hear those thoughts articulated by young children… so, maybe things haven’t changed as much as I might like to believe they have!

Anyway, back to cultivating the ability to witness your thoughts. You might feel that you don’t have nearly as much control over those thoughts as you think you do. Eventually, you might come to feel that it’s something else besides you that’s thinking them.

In his book, The Art of Mastery, Peter Ralston explains how actions relate to perception:

“Your actions are determined by your perceptive-experience… whatever action your mind thinks is called for in relation to what you perceive, that is what you will do, and you have no choice about that.”

Notice that Ralston doesn’t say, “… whatever action you think is called for…” He objectifies your mind as something you have, not you yourself!

At some point during your practice of being a witness to your thoughts, you might even start to get the feeling that there’s something foreign within you that’s telling you what to think and how to feel.

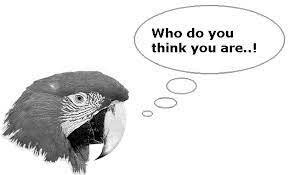

This morning I googled “poison parrot.” In response, I got several references to the poisonous parrot as “a metaphor used to describe those nagging criticisms that pop into your head during the day” or something similar. The remedy or antidote most often suggested was to notice the parrot and cover the cage!

From a website called getselfhelp.co.uk, I found the following (This text is from “The Malevolent Parrot” by Kristina Ivings):

"There’s that parrot again. I don’t have to listen to it – it's just a parrot". Then go and do something else. Put your focus of attention on something other than that parrot. This parrot is poison though, and it won't give up easily, so you'll need to keep using that antidote and be persistent in your practice!

From getselfhelp.co.uk

Where does that poison parrot come from? Why is it there in the first place? And why is it so difficult to shut up?

Now, those are questions worth asking: Here I thought I was the one doing the thinking, and now you’re telling me not only that it might be something else that’s thinking, but that it doesn’t necessarily have my best interests at heart (thus the reference to poison)?

The way I see it, we are born into a pre-exiting understanding of the world that reflects the beliefs of those who taught us language. As we grow, we refine and expand that understanding until it becomes like second nature to us. It becomes the water we swim in. We look at everything we perceive through that understanding, and it determines not only what we see but what we’re able to see. If you look at the world through rose-colored glasses (or any other color), you won’t be able to see certain other colors.

This second-nature understanding is the poison parrot. It tells us not only what’s what but also what’s real.

I’d like to suggest that none of what it tells us is real. It’s all made up.

Suppose that voice in “our heads” is in fact a foreign entity with a greatly exaggerated sense of self-importance. Why does it persist? Why is it so hard to get it to shut up? What is its purpose? What’s it up to?

Try this: what it’s up to is survival. After all, that imperative is built into every creature that’s ever lived on the planet, including ourselves. And since we consider ourselves to be that voice…

That voice is almost never recognized to be something we have and not who we are. It sounds like our voice, and it’s so familiar to us that we take it for granted. We have identified ourselves with it. We have become that voice. So, it’s only natural that it tries to survive because that imperative is built into us!

As long as we identify with that voice, we are not the free beings we pretend to be. Something else is thinking our thoughts and guiding our lives. As Peter Ralston said, whatever action that entity thinks are called for, that’s what we will do, and we will have no choice about that.

So, maybe put a cover over the parrot’s cage. And go do something else… like whatever your heart wants to do.

July 27, 2023

Why Did I Do That?

In his book, The Art of Mastery, Peter Ralston explains how actions relate to perception: “Your actions are determined by your perceptive-experience… whatever action your mind thinks is called for in relation to what you perceive, that is what you will do, and you have no choice about that.”

I think this is a powerful statement, and as such it deserves dissection to really understand what he’s saying.

Photo by Thomas Aeschleman on Unsplash

First of all, let’s look at what is meant by ‘perceive.’ In our normal, default way of thinking about the world, the one we learned from our culture, perception is about detecting and interpreting what is ‘actually there.’

This definition of perception relies on the following premise: all of us assume that we live in a universe in which we are temporary visitors and which would be the way we perceive it to be whether we were here or not.

Quantum physics, however, informs us that the world exists in a superposition of possible states and that it doesn’t settle into the one state we are observing right now until we do so. In other words, we live in an observer-based reality and not a reality which essentially doesn’t ‘care’ whether we’re observing it or not.

In light of this information, we must look more carefully at what we mean by perception. If perception were actually about detecting and evaluating what is actually there, we would be aware in every moment of the superposition of multiple possible configurations of the world. And… we’re not.

So, perception is not the passive sensing of reality. It is rather the active choosing of one of the possible states of reality with which to interact.

Now, lest you think I am talking about a bunch of parallel worlds in a science-fiction context, let me explain what I mean by ‘possible states of reality.’Think about the distinction between response and reaction. Again quoting Peter Ralston, “A response arises from a calm mind and sensitive awareness… A reaction arises from automatic impulses that tend to be motivated by such activities as fear, desire, resistance, vulnerability, anger, or other knee-jerk self-protective actions.”

In my book, Hoodwinked: Exploring our Culture’s Profound Illusions, I describe the worldview we humans have inherited from our culture in terms of an ocean of belief. We are like fish swimming in this ocean, and everything we look at is colored, filtered, and partially obscured by impurities that are dissolved in it. In the case of this ocean of belief, the impurities represent mistaken ideas, incorrect assumptions, and all the beliefs we hold which don’t reflect reality and which we have never questioned. For the most part, we are unable to see the world clearly due to these intervening impurities.

I would suggest that the vast majority of us, in this time of great upheaval, find ourselves looking at the world through what amounts to an ocean of fear and mistrust. For most of us, the moments of calm mind and sensitive awareness Ralston refers to have become few and far between. As a result, we have become reaction machines. When we look out at the world, we tend to see danger and difficulty instead of wellbeing and ease.

This viewpoint is the one reality of the innumerable possible states of the world with which we have unknowingly chosen to interact. And, as Ralston points out, it’s the one reality that determines how we act.

Photo by Roman Kraft on Unsplash

Next time you watch the news or read a newspaper, try looking at the information presented as a report on the reality we have chosen, as opposed to how good or bad you think things are. Try setting aside all your judgements, hopes and desires, and see the reality we live in for what it really is. The reality we perceive, the one we have actively, though unwittingly, chosen, is being shown to us constantly by the actions people take. We take those actions because they are suggested to us by minds which are drenched in fear and anger. And once our minds have suggested those actions, we have no choice but to take them.

That’s worth thinking about. Especially since there are innumerable other possible realities from which to choose.July 12, 2023

Living Into the Looking-Glass

By John Tenniel - Through the Looking-Glass, Public Domain

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, Alice climbs up onto her fireplace mantel, pokes at the wall-hung mirror behind the fireplace and discovers, to her surprise, that she is able to step through it to an alternative world where everything is reversed. That reversal tells her that she is, in fact, in an alternative world. And, she knows that alternative world exists in contrast to the normal one she remembers perfectly well.

We, too, have entered the looking-glass world. The difference is, we don’t remember the “normal” world. We entered the mirrored world so long ago it seems to us perfectly normal.

In order to understand what is meant by a mirrored world, we have to first examine what we mean by “the world.”I know, that’s a very strange thing to say!

It’s an inquiry that is, to say the least, almost never conducted. We all know what we mean when we refer to the world. It’s what we confront when we open our eyes in the morning. You know, it’s what we took our leave from when we went to sleep last night and what we return to, grinding or humming along (depending on your outlook on it) when we awaken. Right?

We “all know” that the world is permanent while we transients come and go. We are convinced that the physical world is senior to us, in that it exists much as it appears to us, whether or not there is anyone or anything around to perceive it. This relationship between the permanent and the transient is part of the worldview we all subscribe to; it’s almost never questioned.

However, let’s look more closely at the idea that the world is senior to us. Consider the part of perception we call vision. The story we’re told is that light is emitted from some electrical process, that it bounces off some object and this reflected light enters our eyes.

From there, the electrical impulses generated in our retinas by the light impinging on them are transmitted to our brains by the optic nerve. Our brains then create pictures from these impulses, and all of us assume that these pictures represent more-or-less accurately the object which reflected the light.

So far, so good.

In science, a story such as the preceding explanation must be validated by observation in order to be considered a tenable idea. A hypothesis must be tested. But there’s a problem here: there is no apparent method by which we could prove or otherwise demonstrate that there are in fact objects “out there,” independent of our perception, that we are perceiving.

In our western culture, at least, we are accustomed to watching our television shows and knowing, at some level of sophistication, that a camera recorded whatever it was aimed at, the data it recorded is transmitted to the TV set and interpreted by an algorithm, and finally the image created by that algorithm is projected on a screen.

But now we have moved into an era in which CGI, or computer graphics imagery, can create that image from scratch without benefit of any collection of objects at which to point the camera. And those who wish to prove the authenticity of the image must find a way to distinguish between a real photo or video and what’s now called a “deepfake.” According to Wikipedia, while the act of creating fake content is not new, deepfakes leverage powerful techniques from machine learning and artificial intelligence to manipulate or generate visual and audio content that can more easily deceive.

So, are we being deceived when we perceive the world?Let’s inquire further into the nature of those pictures our brains generate from the raw material of electrical vibrations in the optic nerve. First of all, we know that our brains are capable of generating those images without benefit of any electrical vibrations in the optic nerve… that’s how dreams work.

From OpenClipart-Vectors on Pixabay

Second, we have likely all experienced that there are variations among the images brains create from those vibrations when more than one of us is viewing the same scene. These variations range from “it’s green…” “no, it’s blue” to different accounts of some event described by people who are each convinced they’re “telling the truth.”

It seems clear to me that the pictures we’re talking about amount to interpretations of the incoming data. And, interpretations are generally influenced and conditioned by belief systems, opinions, perceptual bias, and maybe what we had for lunch.

What’s really going on here?Let’s see what happens if we accept as a premise the idea that all we have is the pictures our brains and that we have no way of verifying that they represent more-or-less accurately an external world that exists “out there” somewhere.

We “all know” that when we act in some way, we are looking out at the external world and attempting to use our actions to change something. We’re looking to rearrange objects or change them in some way, assemble some objects and disassemble others. We’re living out into the world.

But what if that which you’re looking at right now is a picture in your brain? In that case, you are living into that picture; you are attempting to change something in that picture!

Now, add to that the idea that your interpretations, the ones that form the pictures in your brain, are conditioned by your beliefs and your opinions. You’re interpreting electrical impulses according to a very complex algorithm, an algorithm that is shaped by what your parents told you, what you read, what others tell you, and so on. We call that complex process perception.

From a_m_o_u_t_o_n on Pixabay

Your perceptions reflect your opinions and your biases. In fact, once you accept the truth of that statement, you can use your perceptions to identify and, perhaps, even correct your biases.

Now, if our perceptions reflect our beliefs, the world we perceive (remember, it’s just a picture in this argument) serves as a looking glass. So, when we act, we are living “out” into the looking glass, into the reflection we see in the world.

Yes, we are interpreting electrical impulses that in some way are related to the “real world,” whatever that might be, but we have no way of interacting with that world directly. For us as human beings, equipped only with our five senses, our interpretation, our description of the world, always stands in between ourselves and that world.

My promise to you is that if you decide to treat the world as if it reflects your beliefs, you will find yourself recovering the power you gave away when you had to depend on bigger people for your every need when you were young. You’ll find yourself back in the driver’s seat of your life. You’ll discover yourself as a creator of worlds, specifically the one you’re looking at right now.

The Insights Blog

Those superstitions are responsible for Albert Einstein’s declaration that “you can’t solve problems with the same thinking that created them in the first place.” Our superstitions have us hoodwinked!

Those superstitions are responsible for Albert Einstein’s declaration that “you can’t solve problems with the same thinking that created them in the first place.” Constructing belief systems on top of superstitions is like building on top of an unstable foundation.

When we were taught language, it was inevitable that we also acquired the world view of those from whom we learned that language. We now live inside that description of the world, and it shapes and colors everything we look at. Because we depend on that understanding for our well-being and for the success of all our endeavors, it has become a jealous master.

I call our understanding of the world "the water we swim in." Like the proverbial water to the fish, we are essentially unaware that we are immersed in that understanding. My work helps readers unlock their natural power to determine the quality of their own lives. ...more

- Larry Gottlieb's profile

- 122 followers