Ian Garner's Blog

February 2, 2022

Viktor Nekrasov - Stalingrad, February 1943

The author and Stalingrad veteran penned this short reflection on the end of the fighting on the Volga in 1983. Then exiled in France - he never returned to the USSR before his death in 1987 - Nekrasov plays with myths and expectations of Soviet and German troops’ behaviour at Stalingrad.

Employing his customarily slippery narrative style, the author at once reiterates and underlines the validity of Soviet myths of exemplary conduct in the wake of Stalingrad while simultaneously revealing the looting, pillaging, violence, and suffering that defined the post-battle period in the city.

Viktor Nekrasov, 1980s

Stalingrad, February 1943I’m writing these words on 2 February 1983, precisely forty years after the Battle of Stalingrad drew to a close. It was on that long awaited day that the German 6th Army laid down its arms and Field Marshal Paulus signed and sealed the unconditional surrender.

The war in Stalingrad was over. The cannons, howitzers, guns and Katyushas fell silent. The machine guns ceased their fire. But the submachine gun rounds continued to tear into the air. Searchlights, rockets, and tracer rounds joyously combed the sky late into the night. Everyone was drinking away, drinking to our victory, drinking to their defeat, drinking to kaput!

It hadn’t been long before – as recently as 29 January – that the then General Paulus had been signing this radiogram:

“To the Fuhrer. The 6th Army congratulates its Fuhrer on the anniversary of your rise to power. The Swastika flag still waves over Stalingrad. May our fight be an example to today’s generation and the generation to come of how a refusal to capitulate in this hopeless situation will lead to Germany’s victory.”

It was all talk. Five days previously, Paulus had reported to Hitler that, “Further defence is senseless. The catastrophe is inevitable. I ask your urgent permission to surrender that we might save those who remain alive. Signed, Paulus.”

Paulus’ request was turned down. On 31 January, the HQ and commanders of the 6th Army were taken prisoner in the central department store building on the Square of Fallen Fighters. On 2 February, the final army group, the 11th Infantry Corps, ceased combat near the Barricades Factory.

The surrender was complete.

Streams of Germans with hands held high and white flags aloft flowed out of dugouts, bunkers, cellars, crevices, and ruins. They had become prisoners of war. They numbered three hundred and thirty thousand.

Strong and well equipped, they had seized 1,500 kilometres of Soviet land, crossed the Dnepr and the Don, conquered all of Ukraine, reached and climbed Mount Elbrus to the south, and made it to the Volga. Now out they came, downcast, frozen and unaware of what awaited them…

What was to come? Revenge? Humiliation? Denigration? Cruelty?

None of that happened in Stalingrad. Dozens, hundreds of prisoners passed through my charge, through my dugout, through the neighbouring dugouts, and through our commanders’ dugouts. There was no denigration and there was no cruelty from either the COs or the troops. But mock we did:

“Well then, well then, made it to the Volga, did we? Liked it, did we? Had to tear through, eh? What’ve you got in your kitbag, then? Go on, give us a look! Photos? Give ‘em here. Who’s that, your little Gretchen? Cor, what a looker, what I wouldn’t do..!”

What came after was the usual soldier’s filth, but nobody took their photo albums away. That was the orders we’d been given. We left them with their owners, an act considered the very height of mercy. That would be followed by the ordinary: “Want a bite to eat, Fritz? There, take it! Have a smoke…you don’t even know how to roll? You’re used to your German cigarettes; here’s how you do it, have a look.”

Even reflecting hard on those days forty years past, I cannot remember a single example of cruelty or even impropriety. Later, in Eastern Prussia, it was a different matter. Violence, plunder, and murder. The murder of innocents and civilians. The fluff from ripped up feather mattresses whirled over their bodies for weeks on end. It was then that Stalin had allowed packages to be sent home from the front. He was obviously saying, “Loot it all! I’m giving you permission!” A week later, to be fair, came another order: “Looters and aggressors are to be shot.” But it was too late; people were coming up from the rear and they had to allow themselves a few entertainments, regardless of orders.

There was none of that in Stalingrad. If it did happen – after all, everything happens a little everywhere – I didn’t see any of it. And that makes it all the more awful to hear and read about what’s happening in Afghanistan today. At Stalingrad we were fighting invaders, but in Afghanistan, the Soviet soldier has become the invader. I don’t want to believe it, but he is stealing and committing violence without a damn. That’s a terrible thing.

Thus ended the war. Silence descended. An unnatural, unfamiliar, unbreakable silence broken only by the odd round of drunken submachine gun fire. Silence—and a kind of idleness. Inertia forced the issuing of some commands—clean this, wash that, take it apart, guard it—and inertia forced the unhurried fulfilment of these orders. Yet mostly we just blabbered away and rifled through German dugouts. We dragged out everything we could get our hands on. I sought out in particular newspapers, magazines, illustrated brochures, and stamp albums (that’s right, the Germans even seemed to have time for that at the front). Then, snug and warm in my bunker, I’d leaf through my Volkischer Beobachters and Allgemeiner Zeitungs and get acquainted with German propaganda.

They really didn’t do a bad job of it at all. It wasn’t even really propaganda as such; it was more of a strong link between the rear and the front, which is an extremely important thing. Until the very last the Germans kept dropping national and local newspapers and letters from relatives for their surrounded soldiers. For Christmas they got little folded cardboard Christmas trees, written for some or other corporal from his beloved Frau Muller, still in his native Weissenford.

I’d keep working my way through these newspapers and magazines, then one of the artillerymen or the scouts would turn up—and what did we do? We drank. We had plenty: our own stuff, and stuff we’d seized.

And that was how we spent the first half of February. No hard work: demining a few nasty minefields, tidying up some barbed wire, burying the dead (of which there was a considerable quantity in no man’s land), then spending our evenings…well, what do you think we did in the evenings? Have a bet.

In the middle of February, we fetched up our things and moved them to Leninsk on the left bank. Then we were loaded onto trains bound not for the east, not for the leave we all thought we’d get, but for the west. Forward—westward!

April 29, 2021

Pavel Nilin—The Polykhaevs

In this short story from a 1951 edition of the Soviet magazine Ogonek, Pavel Nilin tells the story of a pair of Stalingraders—the elderly Polykhaevs—who lived through the razing of the city in 1942 and took part in the early reconstruction. They welcome their long-lost grandson, Petya, who embodies the so-called “Stalingrad spirit” of young communists seeking to emulate the self-sacrifice of the older generation by participating in larger construction projects in Stalingrad.

Nilin’s story exemplifies the late-Stalinist Stalingrad story: the older Polykhaev, Erofey Kuzmich, symbolically dies and is resurrected with the city during the battle, while the sacrifices of the past are instrumentalised to encourage sacrifice in the present.

While the story is typical, Nilin—a relatively well-known writer of peasant origin—has a knack for characterizing the grandparents as a bickering elderly couple and for capturing the traumatic flashbacks the grandmother experiences as she seems almost to relive the events of her grandson’s evacuation from Stalingrad.

The translation from the Russian—an off-cut from my forthcoming compilation, Stalingrad Lives—is the first Nilin work to appear in English.

The Polykhaevs

Lately Grandmother had constantly been scuttling off to the highway to wait for a particular car. She would standing in the piercing wind for hours on end. On and on went the cars. Thousands must have gone by, but that car, the car that would bring Petya, did not come.

At last, one morning, Grandmother was getting ready to go to the highway. She was chasing around after the gloves that the kitten must have dragged off somewhere when Grandfather, Erofey Kuzmich, said:

“Sit down! You don’t want to catch a cold, do you? He’ll come when he comes, but running all over the place won’t do a thing. You’re no spring chicken.”

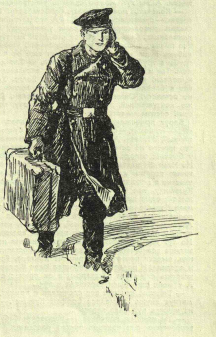

Grandmother was beaten. She sat down and began unbuttoning her fur jacket. She had just unbundled herself and taken off her lace shawl when a young man should appear amongst the snowdrifts on the path leading to the house. A belt with a shiny buckle looped around his black overcoat, while his black cap was quite inappropriate for the season. He carried a suitcase in one hand and was clapping the other hand against his ears so as to protect them from the wind.

Grandfather happened to be looking out the window when the boy approached. He stared at the lad intently. He did not move, nor did he say anything to Grandmother. After all, lots of people had turned up of late! Thousands of people were arriving on foot and by rail and road. A great undertaking was in progress.

There was a knock at the door. Grandmother raced to open it and instantly recoiled when she saw an unfamiliar young man in the cloud of steam.

“Do the Polykhaevs live here?” asked the young man.

“Petenka!” cried Grandmother. She burst into tears and began to race around. “Petenka...you’ve Anfisa’s eyes...it’s like Anfisa’s here…”

She helped her grandson to undress. When taking his cold overcoat, she observed that he had his father Vasya’s mouth and nose. Kissing his cheeks, still rosy from the cold, she did not stop crying.

Grandfather Erofey Kuzmich merely frowned a little and said:

“What are you doing wandering around in a cap like that in this weather? Haven’t you got a proper one? Drank it away, did you?”

“Not at all, Grandfather! I’m teetotal,” smiled Petya. “I’m just used to wearing a cap in any weather. They say your hair grows better if you wear a cap in winter. My hat’s in my suitcase.”

“Just like your father,” smiled Grandmother, wiping away the tears. “Vasya was just the same: well-dressed and a bit of a dandy. But your eyes are Anfisa’s. They’re her eyes...but you take your boots off now, quick step! You must be frozen right through.” She prodded him towards a stool so that he would find it easier to take off his boots. “Look at that, your boots are hard as iron after that cold. You should have work felt boots.”

“It’s much better to be in regular boots; I like how they feel! My felt ones are strapped to my suitcase,” said her grandson. He walked across the ochred clay floor in his woollen socks.

Grandmother sat him down next to the warm stove and started to put out the food she had prepared for her grandson’s arrival.

“We’ve been waiting almost two weeks for you, Petenka. Ever since we got your letter.”

Grandmother hustled and bustled around the table as if she were afraid of being late for something.

“Get out of it, you little devil!” she hissed at the cat who was trying to catch at her hem.

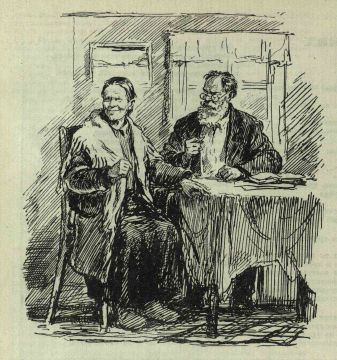

Grandfather silently looked the lad over. He had not yet decided how he ought to view this boy who was, in reality, a stranger.

“You wrote that you’d be here by the 12th, but it’s Sunday the 13th today” said Grandfather and tore a page off the calendar. “Where did you get held up?”

“D’you see, here’s what happened,” he began to explain as he coughed importantly into his hand. “I asked to go to Stalingrad, of course, and was issued documents to that effect. Then it turned out they’d already sent a bunch of our students here. Comrade Antonov said, ‘Go to Kuibyshev. It’s a site of great construction projects too,’ he says, ‘so I don’t see as it makes any difference. Or if you want we could send you to Central Asia.’

“I said to him, ‘Well it makes a difference to me. Stalingrad’s my hometown. It’s where I was born, where my mother and father were from.’ And he said, ‘Don’t get all sentimental. It doesn’t matter where people’s parents are from, we’re working to a plan. And don’t you forget that you’re a Komsomol member.’

“So I went to Comrade Samsonov. He summoned Antonov and said, ‘Don’t play the fool, you’ve got to fulfil Comrade Polykhaev’s request! Let Polykhaev go to Stalingrad.’ That’s why I was delayed. My training means I could have gone to Kuibyshev, to Central Asia, anywhere really…”

“And what was that training?”

“I’m learning to work with concrete.”

That answer pleased Grandfather immensely. He hadn’t said that “I am an expert” or that “I became an expert”; he’d said that he was “learning.” Quite right too. The old bricklayer had built dozens of houses in his time and knew that it took a whole lifetime to develop real expertise. His grandson was no young fool, then. He meant business.

“What’ve you put that fruit wine out for, Nadeya? Who’s going to drink that, eh? Better to get us out a good half-litre, something for the men…”

“Please, Erofey Kuzmich,” said Grandmother, “you don’t drink, and Petenka’s too young yet.”

“That’s no bother. It’s okay to mark an arrival. Especially on account of the cold.”

Two young girls emerged from the corner room. Grandmother had summoned their lodgers, a couple of surveyors, to meet her grandson. They greeted him and introduced themselves as Vera and Galya.

He offered them his hand and introduced himself—solemnly, the way a grown man should—by his surname alone: “Polykhaev.”

The death of two sons in the war had not done for that bricklaying family’s name. It had not disappeared, nor would it do so now, even if Erofey Kuzmich were to die. He had no intention of dying anytime soon, though. He still wanted to see how everything would grow, how a mighty hydroelectric station would be built and change everything, even the climate itself. He had heard that the forests and groves of graceful oaks would be enormous. Steamers from across the seas would, they said, mingle in this very port. Perhaps Erofey Kuzmich and Nadezhda Pavlovna—Grandmother Nadya—might yet set sail from here on a trip to far-off seas. Everything was possible, just so long as there was not another war. That would be a very bad thing indeed.

“Right then, let’s drink to you, Petr,” said Grandfather as if he were finishing off a thought. He raised his glass. “To you, and to all the young people who’ll come after us.”

Everybody clinked their glasses, downed the contents, and began to tuck in to the food. Grandmother alone did not eat, for she was constantly, unerringly, looking at her grandson. Heavy tears ran down her rosy cheeks. Oh, how big he’d grown, the little lad! There was no chance she’d be able to pick him up and carry him even a couple of paces now, oh no – not like she had carried him in the fall of ’42 to the quay, to the last passenger boat to leave Stalingrad.

What horrors were wrought in the city at that time! It is dreadful even to recall them; you cannot believe what we saw with our very own eyes. Yet we are still alive.

Grandfather was still young back then. He worked as a bricklayer and instructed other bricklayers too. Grandmother was a cook in the children’s home, where her grandson Petya would pass the days with her. When the Germans got close to Stalingrad, Grandfather went off to build defensive lines, and Grandmother helped to evacuate children from the home. Grandfather did not allow his grandson Petya to leave:

“He ought to stay here with us. Maybe everything will work out somehow, and then we’ll know what’s what.”

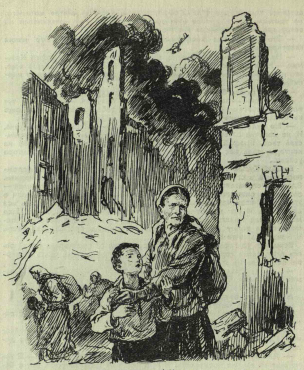

Petya stayed at home supervised by an infirm neighbour. Life in the city was becoming unbearable. The enemy was bombing the town every day and every night. The city burned with fire. The time came when the Polykhaevs’ neighbour was about to leave.

“You’re mad,” she said to Grandmother, “You’re in danger yourselves, but why are you keeping the little boy here when death is right here, right in front of you, and it might take any one of us at any time? Just think how many people have died already…”

The last passenger steamer was due to leave Stalingrad with the children. Grandmother insisted that her grandson was to go too: “I couldn’t have it on my conscience if, God forbid, the boy should perish.”

She had soon kitted him out for the journey, so they set off for the quay. Getting there was no mean feat by that point. Houses on both sides of the street were in flames. Charred logs, burning timber, and hot chunks of iron were falling onto the pavement.

They walked two blocks. Grandmother’s dress and headscarf were smouldering, but she stubbornly kept moving forward. Her grandson was crying and kept pulling back:

“I shan’t go! I shan’t! Take me home or I’ll cry even more!”

At last they made it past the burning houses and onto a wide square, where they doubled their pace. Grandmother suddenly stopped.

“Good grief, my child!” she said, totally shaken having spotted an enormous elephant covered in dust from red bricks on the square. “Did they disturb you, you poor thing?” The elephant, driven from the zoo by the bombardment, seemed to surprise her more than the fires.

The grandson stopped crying. He stared wide-eyed at the elephant forlornly waving its trunk like a fire hose and slowly wandering through the ruined and burning buildings.

Even the enemy planes that had suddenly struck up a racket over the square could not draw the boy’s attention from this surprising passerby, who seemed utterly exhausted from the hellish fires.

“We have to go, Petenka,” said Grandmother, tugging on the boy’s hand, “quickly now.”

“No, wait up, let me have a look at him,” the boy said with an almost adult decisiveness.

“We’ll be killed any minute now, you fool! See those German planes?”

She pointed at the sky, which was clouded over with black smoke. Oil was burning somewhere nearby.

“Let them kill us,” said Petya angrily. “We’re going to look.”

Grandmother stooped down, seized the boy by his legs, threw him over her shoulder like a sack, and began to run across the square.

“Where did that strength come from?” she now wondered as she sat across the table from the cheery, almost unrecognizably mature young man. She wanted to ask if he remembered the elephant, but thought the better of interrupting grandfather and grandson’s lively conversation. Let them have a good talk, she thought, when they have not seen each other for so long.

Indeed, they had much to talk about. Grandfather was listening to Petya with satisfaction. He was especially pleased that his descendant had followed in the footsteps of the other Polykhaevs: he may not have been a bricklayer, but at least he was in construction. Construction would always be a useful and glorious business.

“I suppose you want to work on the dam?”

“Of course,” said the grandson with an air of importance. “We’re going to lay the cement, but I need to take some courses here first. Then I’ll get right to work.”

“That’s good,” said Grandfather. “You’ll be a sort of city founder. You’ll grow up, get married, and walk along the dam with your own children and, perhaps, you’ll say: ‘Look here, kids, I was here when this station was built. I took part in the construction myself. And now the whole world knows about it!’”

“I don’t think I’ll be married by the time the construction is done,” smiled Petya and, slightly blushing, squinted over at the young surveyors sitting at the table.

The surveyors smiled too. The perky, hazel-eyed Galya, who had something of the Armenian about her, reminded them: “After all, the station will be finished within five years. That means you’ll be twenty-one, Petya. Or maybe a little older?”

Petya gave the impression that he had not heard the question. He did not want these girls to know exactly how old he was; he wanted to seem more grown up. Trying to change the topic, he said, “I could barely wait to be sent to Stalingrad…”

At this, Grandmother again started to recall how her grandson had left Stalingrad. Grandfather had run to the quay, but the boat was already gone. It was in the middle of the river when when enemy bombers flew at it and released their bombs. Grandmother covered her face with her hands, but Grandfather looked on at the defenceless, dying steamer and at the boiling water in which his only grandson was certain to have perished. He looked as rowboats set off for the steamer from the other bank, but knew that nobody could be saved after such a disaster.

“You didn’t listen! He’s drowned. The boy’s drowned,” said Erofey Kuzmich. But seeing how Grandmother had fallen to the grass and was convulsing as if she wanted to bury herself in the ground, his bravery evaporated completely.

“Nadeya...what now, Nadeya?” he said as he bent over her. He stood, scooped up some water topped by a layer of smoking oil with his cap, and gave it to his wife.

“Nadeya! Snap out of it, Nadeya. There’s more to come for sure…”

He never managed to calm her, just he never promised the impossible. He had not done so in their youth when he had borrowed a comrade’s pair of boots for their wedding; nor did he do so in their old age, when the war led them to the gravest of tribulations.

He picked his wife, her whole body still trembling, up from the grass. He led her home, supporting her by the shoulders from which hung charred strips of a colourful dress. She quietly wept, pressing herself to him, and kept repeating:

“Forgive me, Erofey Kuzmich, I didn’t listen to you, and now the boy’s drowned. You’re right, he’s drowned. But I honestly thought I was doing something good for him. Just look at what’s happening all around us...what’s next?”

“I don’t know, Nadeya. I don’t know anything,” said Erofey Kuzmich. “We just need to get back home to the apartment so you can lie down and relax. Maybe you could use some of your droplets. You’ve got all sorts. Things are only going to get worse...we need to preserve our strength…”

Getting home by the directest route now, though, had become impossible. Flaming rubble from destroyed houses was covering both streets leading from the quay to the house. They would have to go around.

It took almost until evening to get back, but when they finally made it, they realized that there was nothing to get back to. Only the two corner walls of the massive five-storey house remained. In the middle, on the third floor, a kitchen shelf remained. Two enamel pans hung from the shelf, jangling in the wind.

“Those are the Zavyavlovs’ pans. That was their apartment,” said Grandmother.

“It doesn’t matter whose it was any more,” said Erofey Kuzmich. “Pans and apartments don’t matter now. In fact it’s a good thing we weren’t here, else we’d be lying under those bricks.”

“Maybe that would have been for the best,” sighed Grandmother.

“Quiet!” shouted Erofey Kuzmich. “Stop your panicking! I have no intention of dying. And I order you not to. I’m not done with living yet…”

“Where shall you and I go now?” asked his wife timidly. And then she rather more boldly scolded her husband: “It’s all on account of your stubbornness, Erofey Kuzmich! Zlatorogov came from the bureau twice to get us evacuated. And now the bureau’s probably gone too.”

Erofey Kuzmich was silent. He contemplated the ruins of the massive house that he had been laying bricks for not six years past. He had received two prizes for work on this very site. He had been given a big and light apartment for his entire family in this very building. And now there was no house, no building, and no family. A month ago they had received the notice of their two sons’ deaths, while the wife who had volunteered to go with her husband, their son, was missing. What’s next? Mm?

Thinking back to that terrible time, Grandmother once again smelled the acrid burning, the sizzling air again clutched at her heart, and she again froze, just as she had frozen back then, in the ruins.

“Pour us a spot of tea, Nadeya. Tea, I said,” repeated Erofey Kuzmich and touched Grandmother’s arm to rouse her.

“Ooh, tea. Hold on,” said Grandmother and reached for the samovar. Grandfather winked to his lodgers and grandson and smiled:

“Grandmother’s probably tipsy! Tipsy after one glass…”

“Of course I’m tipsy when I’m with you,” smiled Grandmother as if coming round from her reverie.

“Right then,” Erofey Kuzmich went on, “we’ll drink our tea and head to the building site, Petr. You can see what’s being built here.”

“Why do you have to go now?” exclaimed Grandmother, “I still want to look at my grandson. He can look around by himself. Let him chat with the young ladies and warm up, then I’ll show him the house.”

“You think he hasn’t seen houses just like this, d’you?” said Grandfather. “He came on business, so he ought to have a look at what’s to be done.”

“He’ll have plenty of time to get a good look.” Grandmother was not giving in. “You see, Petya, your Grandfather and I built this house ourselves. It was the first house in the new settlement. Everything had been utterly destroyed, totally flattened. Your Grandfather and I were living in a bunker under the hill. Grandfather was concussed.”

“Off she goes again!” grimaced Erofey Kuzmich. Grandmother wanted to explain right away how they had left the ruins of their house late one night in that terrible autumn, how they had gone to the district council in the Volga embankment, and how they had been assigned work.

Their work in the city was uniquely sad. They had to remove and bury the bodies and clean the detritus from the streets. It was impossible to walk, let alone drive, along the streets. Houses were burning and collapsing every day. The fires had to be extinguished.

Grandmother was hired as a cook and Grandfather as an orderly in the underground hospital. When the enemy bombed the hospital, Grandmother found work as a washerwoman. She washed army uniforms, and Grandfather helped by bringing water. He had to crawl everywhere to avoid the ceaseless firing from every side. He adopted all sorts of cunning ploys to make it to the Volga right under the enemy’s nose. He would pour water into a tub then, on all fours, drag it behind him on a sled. Bullets were constantly striking the tub and, if he were not careful, might well have hit him too. And hit him they did—in the shoulder and arm.

Grandmother sighed.

“What are you sighing for?” said Erofey Kuzmich. “You oughtn’t to sigh but to be happy. We survived and we’ll live a while yet—and life will be better! Are you regretting that we didn’t leave Stalingrad back then?”

“I don’t regret it a bit,” said Grandmother. “I’m just surprised that we survived. So many people died before our very eyes! Even iron burns and breaks in fire. Stone couldn’t have survived it. But us…”

“Your pride is endless,” smiled Grandfather, “and your self-worth too. Anyone listening would think that you defended Stalingrad alone.”

“I wasn’t alone. I was with everyone who was here and helped out,” said Grandmother. “Nobody can take that away from me.”

“Very true,” agreed Erofey Kuzmich, “but you oughtn’t to sigh. I dislike it more than anything when people go sighing over nothing. Look, our grandson has come, and he’d like to hear something new…”

“On the contrary, I wanted to ask what it was like,” said Petya, “since I only know what the Battle of Stalingrad was like from books and what I saw in the cinema. But you, one could say, took part…”

Grandmother livened up: “Of course one could say we took part. Everything happened right in front of us. But even now it’s impossible to explain it. I wonder at how it all happened. I shall probably die wondering. We were basically crawling around for a hundred days. Crawling, crawling on all fours, so as not to get hit by a bullet or shrapnel, or by who knows what. From trench to trench, pipe to pipe, basement to basement, bunker to bunker. Crawling. The whole city was crawling back and forth. And then we crawled out to this settlement, right to the Volga. The fighting had stopped and we were still living in bunkers. There was nowhere to live. Even the shells of houses were gone. Just broken, burning brick. Grandfather was lying concussed in the bunker, and I was bustling about after him like a nurse, a sister of mercy, as best I could.”

“You’re giving yourself too much credit,” said Grandfather, and mimicked her, “Like a nurse! Honestly…”

“Well, like an orderly then,” Grandmother corrected herself. “It doesn’t matter who I was like. What’s important is that I was looking after you the whole time. Then out of the blue Ivan Fedorovich Chalov, an engineer we knew, came: ‘We’re going to rebuild the factory—the Tractor Factory, the STF.[1] It’s an urgent matter.’ What was there to rebuild when almost nothing of the factory remained? The only thing standing was a statue, now riddled with bullet holes, by the gates. But Ivan Fedorovich Chalov said, ‘We’re putting up canvas tents for the workers around the factory. I want you to take part in the reconstruction.’ He said that to Erofey Kuzmich, because he was a bricklayer, and not to me, of course.

“But Erofey Kuzmich was barely alive—he was all skin and bones—and I thought that he’d never go back to bricklaying. He couldn’t pick up stone, and could not leave the bunker at all. And it was terribly cold. There was no food, because we’d been living off soldiers’ rations before. When the fighting was over, the soldiers had left for Berlin or wherever it was.

“Soon a woman from the district council who was going around all the bunkers found us. She said she’d give us food and ration cards, and send a doctor. She did everything she said, so when Ivan Fedorovich Chalov came, I gave him some tea and sugar. He’d brought some vodka and sausage, and I even got hold of some potatoes and onions.”

“Look how she’s accounted for everything and remembers who had what,” winked a laughing Erofey Kuzmich to his grandson. “What a spendthrift! She’d squeeze a whole pound of fat out of a sparrow!”

“Don’t interrupt,” said Grandmother, “I’m just trying to remember everything I can. After all, he asked us to tell him how we lived.

“So there we are in the bunker, drinking tea, and suddenly Ivan Fedorovich Chalov said, ‘By the way, I saw your Petya in the Urals.’ I asked, ‘Which Petya?’ Your Grandfather and I didn’t even hope to find you amongst the living after the steamer sank in front of us. Ivan Fedorovich said: ‘What d’you mean which Petya? The Petya, your grandson. He and my boy Grisha were in a children’s home together. Now they’re at school.’ I wrote down your address and sent you a letter. There was no reply for a year, even though I wrote close half a dozen letters.

“Then Grandfather Erofey Kuzmich began to get better, which was a shock to us all. Soon he went off to work. Not on the Tractor Factory, admittedly, because it was too far to travel, and they didn’t have any housing apart from tents. He worked right here in the village construction office.”

“The office is long gone,” said Erofey Kuzmich, and pointed out the window. “It was right there, where our girls”—he nodded at the surveyors—“have opened their office now. The drilling experts are housed there. Everything is going to be rather different now than how we imagined it back at the start. The hydrostation will create everything anew. One end of the dam will be pretty close to here.”

“I know,” said Petya, “I saw the design.”

Then Grandmother, rather offended, said, “Maybe you can tell the story by yourself, Erofey Kuzmich. I’ll be quiet. I’m not mad, of course, but…”

Grandfather smiled and offered some praise: “No, it’ll be better if you do it; you do it well. Maybe afterward you could put together a book.”

“I’m not putting together any books,” said Grandmother. “I’m just saying what I remember. Petena, the bunker where we lived was really quite close. You could see the spot from here, but it’s all covered in snow. One night, after the fighting was over and we were living in the bunker, Erofey Kuzmich’s shoulder started hurting again. He couldn’t fall asleep, so he was tossing and turning and grumbling away. I woke up and asked, ‘What are you grumbling about, Erofey Kuzmich?’ And he said, ‘I’m not grumbling, I’m thinking. Isn’t this all rather strange? I’m a bricklayer living in a bunker. Couldn’t I just build myself a house? I can’t just sit here waiting for life to happen, can I?’ So I said: ‘They’ll give us an apartment soon, for sure.’ And he said: ‘I doubt it. We have to take care of ourselves, and we could be a good example for others.’

“One morning quite soon after, on a Sunday too as it happens, he left the bunker and ordered me to come too. So off I went, of course, without a clue as to why or where. We walked for a kilometre or so, and then he suddenly stopped and said: ‘We shall build a little house on this very spot, and that the way we’ll start the street anew.’ To tell the truth, the street was still in ruins, all battered and burned bricks. But you can’t change Erofey Kuzmich’s mind. As soon as he’s got an idea in his head he won’t change course. On the following day he went to the district council and filled out the paperwork. Then a technician, a girl, came to the bunker, and said, ‘The district council has no objections to your plan, but we were a bit surprised that old timers like yourselves would want to take on such a project. But we’ll do whatever we can to help.”

“You’re going on a bit, Nadeya,” said Erofey Kuzmich, “this story’s taking a long time.”

“The house wasn’t built in a day, though.” said Grandmother, “We had to dig out the foundation. We had a lantern, the “bat” type, in the bunker. Misha Paderin, a sergeant from Siberia, gave it to us as a parting gift. As soon as Erofey Kuzmich got back from the construction office, he would eat, nap for an hour, and we would take that lantern and head for the construction site—for the Polykhaev Building Co.! That’s the nickname the council gave our house. We’d hang the lantern on a tripod then spend half the night digging around in the rubble, picking out the good bricks. We did that for a week or two until one evening we noticed lanterns just like ours glowing around us. Turns out more builders had turned up! The material we needed—charred brick and timber—was right there, to hand. The district council started on construction too. ‘Well there’s the competition!’ Erofey Kuzmich said, ‘We can’t skip a beat now. I wonder who’ll finish first.’ And we didn’t skip a beat. We put, as they say, our heart and soul into the work.”

“We took the work very seriously,” confirmed Grandfather as he looked at his grandson. “We really put our backs into it. You’d lie down to sleep, but your body’s still raring to go and bricks, mortar, and more bricks are swimming before your eyes. He turned to his wife. “Nadeya, I didn’t want to praise you for your work too much back then. I was afraid to offer praise. I thought it’d make you proud. But now I can say this: you’re a real fighter, even though you think you’re just some little old lady. The young ‘uns don’t stand a chance against you.”

Grandmother was embarrassed by this praise. She blushed and continued to tell her tale, but now without looking at Grandfather and still referring to him formally by his name and patronymic:

“Erofey Kuzmich wanted to get the front corner of the house, the one that would begin the street, built quickly. The moment it was done, Erofey Kuzmich cut out a wooden board, heated up a spike nail, and etched the street name—the old name—and the house number—number one—into the board. He fixed the board to the corner, stood back to admire it, and called me over. ‘Just you have a look at that, Nadeya! Now we have a proper address. Write another letter to the grandson…’ Naturally, I wrote the letter.”

“That’s right,” affirmed Grandfather, “she read me that letter. I was mad that she was crying so much, though. She dripped tears all over it. All the letters ended up smudged and blurred.”

Grandmother missed this last comment. She was in such a rush to keep telling the story that she continued:

“So. Our project, our Polykhaev Building Co., was getting close to being finished, when we found out that our neighbours—a team of mostly women—weren’t building a house for themselves. They were building a house for the greater good, for the orphans who were being discovered in practically every bunker. Erofey Kuzmich started to think: ‘What we’re doing isn’t right, Nadeya. People are working for the greater good, but we’re just doing it for ourselves, like private traders. Shouldn’t we give up our home for the children, mm?’ I said, ‘Well of course we can give it up. We’ll stay in the bunker and the children can come here. We had children too. This house can serve as a memorial to our perished children.’ And then I burst into tears.

“Erofey Kuzmich looked at me all suspicious, as usual, and said, ‘Those are crocodile tears, Nadeya. It’s not right. You’re crying from greed. You don’t want to give up your house for the children, so you’re crying.’ I was terribly offended by that and went off to the district council by myself to let them know we’d be giving the house up for the orphaned children. But they just waved their hands and said, ‘What are you on about? What would we need your house for? This house we’re building out of burned-out brick for the orphans is just a temporary measure. Soon real houses will be built. The funds are already in place.’

“While Grandfather Erofey and I were building our house the Tractor Factory had already started to produce new tractors. The other factories were working at full steam, even though there had been barely a brick left of them after the fighting. I thought I’d die and never see Stalingrad rise again. Now even the foreigners arriving are awestruck: ‘Nobody’s planning to restore many of our cities where the war was fought. But here everything’s like in a fairy tale…’”

“Don’t get started on foreigners, or you’ll never stop,” smiled Erofey Kuzmich. “You were talking about the house, but now you’ve gone off on some tangent like you were writing to a newspaper. You’ve dragged foreigners into it for some reason.”

“Maybe I won’t tell them anything at all, then.” Grandmother was getting offended again.

“No, you keep on talking now you’re started, just don’t rabbit on about this and that,” said a frowning Erofey Kuzmich.

Grandmother explained how, once the house was built, they did it up inside. She talked about how they got hold of and cut up timber, and how they acquired paint, nails, lime, latches and door handles.

“That was all easy,” Erofey Kuzmich again interrupted, “what really took something was the basement.” He pulled up the mat lying under his feet, grabbed an iron ring attached to the floor, and deftly lifted a trapdoor.

“There it is,” he said, staring into the dark pit, “I’ll turn the light on.” He flicked the switch. When lit, the pit turned out to be an enormous basement lined with small tiles. Grandfather was suddenly overcome with embarrassment: “It’s not such a great piece of workmanship really. It’s no Volga-Don, and no hydrostation. But people in the know will understand. Not a drop of water gets through. It’s really not badly done at all. We’ve got potato, carrot, and cabbage stored down here.”

“We’ve got a little garden”—Grandmother had to get her two cents in—“You can’t see it right now because of the snow. But it’s just beautiful in the spring!”

“It’s hardly beautiful,” said Erofey Kuzmich, “but it’s a good thing the Volga’s so close.”

“It’s no good thing at all!” exclaimed one of the surveyors—Vera with the red face, who had been silent until now. She turned bright red as her friend quickly grabbed Vera’s hand. Erofey Kuzmich looked at his lodgers.

“What did you say?”

“Nothing, nothing...just a silly remark…” answered Galya on Vera’s behalf.

Erofey Kuzmich’s countenance grew dark, but Grandmother continued to explain how she and Grandfather had read their grandson’s first letter—written in “letters just so!”—and had planned to visit him then changed their minds, and how they had delighted at his enrolment in the vocational school, how they had packed parcels for him, and how they had waited for him.

“And then you came, Petenka. I still can’t believe you came. Now Grandfather and I shall be at peace. We don’t need anything else. Not a thing. Only for you to be right here with us. All our hopes are resting on you…”

At this Grandmother looked at her husband and began to get quite emotional. What was Erofey Kuzmich’s sudden dark look? Maybe she had misspoken? The lodgers were whispering back and forth about something or other. Perhaps they had noticed something wrong?

Grandmother felt the situation rather awkward, so she broke the silence:

“I’ve got some nuts too; I’d forgotten about them. I’ll go and grab them.”

She disappeared into the kitchen. Erofey Kuzmich went over to the lodgers, sat on a chest right next to them, and said:

“Are you done muttering about your little secrets, girls? Shared them all already, have you?”

“We’re not keeping secrets, Erofey Kuzmich,” said an apologetic Galya.

“I know all about you and your secrets,” smiled Erofey Kuzmich, “you just think that nobody knows them but you.”

“Honestly, Erofey Kuzmich,” exclaimed Vera, “we didn’t say anything!”

“Don’t be embarrassed now,” said Erofey Kuzmich. “I heard what you said about the Volga: ‘It’s not good that we’re so near the Volga’.”

“Well, it’s not,” affirmed Galya. “And it’s going to annoy us for as long as we’re here. We’re used to it, but it’s still not clear…”

“No. It’s already clear,” said Erofey Kuzmich.

“What happened?” asked Petya.

“They can explain,” said Erofey Kuzmich, gesturing to the surveyors.

“Well nothing has really happened yet,” said Vera and coquettishly corrected her hair, “but according to the plans for the hydrostation’s construction, we have to widen the river here. That means that this house and the neighbouring ones…”

Vera saw Grandmother returning from the kitchen and fell silent.

“In short,” concluded Tanya, “this conversation isn’t important right now.”

“But why?” asked Grandmother, placing a dish of nuts on the table. “Am I disturbing you?”

“No, of course not, Nadezhda Pavlovna!” Vera said awkwardly.

Everyone tucked into the nuts. Vera tried to crack one with her teeth. She had no luck, so took the nutcracker. Grandmother broke into a smile.

“You can’t crack them with your teeth, then, Verochka? You’re not strong enough? Watch how it’s done.” Gripping a nut between her teeth, she cracked it open smoothly and placed it on her palm. “See that, Verochka? I’ve still got my teeth; all present and correct! You feel sorry for me, but I’m not that old…”

“Why d’you think I feel sorry for you?”

“You do. You’re worried that if I find out what you know I’ll be upset.”

“I don’t know anything.”

“You do. You know that they plan to demolish the house, but you’re trying to keep it secret so as not to upset the old lady.” Grandmother squinted, almost angrily. “Do you really think I’ll cling onto this house without thinking of the greater good? Do you think I’ll go off crying like some bourgeois who’s lost her property?”

“Well it would still be your property,” said Galya. “The state will pay you handsomely for it. And they’ll give you another apartment—an even better one!”

“Are you trying to calm me down?” asked Grandmother. “Have I really worked for years and made it to old age so that some young girl can mollify me? Does money matter? Am I looking for a quiet life? My husband Erofey Kuzmich and I have taken part in all the great events of our lifetime. Do you really think after all that I’ll lock myself up in this house and close my eyes to what’s going on around me?”

“Alright, alright,” said Erofey Kuzmich. “Enough of that endless pride of yours, Nadeya! Enough!”

“Am I not telling the truth, hm?” asked Grandmother. “Did you and I exhaust ourselves for good building this house, Erofey Kuzmich? Is this the last of our efforts?”

“No, it’s not the end,” agreed Erofey Kuzmich. “We shall live and work yet, Nadeya, and we shall see what’s being done…”

“You wanted us to go to the Volga,” Petya interrupted his Grandfather.

“Let’s go, Petya,” said Grandfather. “Let’s go. I’ll show you what’s happening all around. We’ve done quite enough sitting around…”

February 17, 2021

Unknown Friends (Vadim Sobko)

Since I had way too much material for my forthcoming book, Stalingrad Lives, I thought I’d publish some of the off-cuts here. If you want more - but even better! - stories, wait for the book to come out. In the meantime, you’re stuck with this…

Vadim Sobko’s Unknown Friends is a typical piece of micro-fiction (that’s right, Soviet writers were the original hipsters) written at the Stalingrad Front. Published in late September 1942 in the national newspaper Izvestiya, the story’s focus on individuals’ guile and cunning in a bleak period when Stalingrad seemed certain to be lost was typical.

Sobko, who had barely left the front for over a year as his unit retreated from Odessa back towards and past Rostov, would be awarded the Order of the Red Star and other medals for his work and bravery at Stalingrad (and would later barely escape death in the Battle for Berlin). In Unknown Friends, Sobko prompts the reader to imagine that any passerby or stranger might be the one to save them or their loved ones: this, Sobko opined, was not a battle for Stalin or between great powers, but a daily conflict to save kith and kin. The romanticism of the tale—the charming idea of hidden and surprising encounters colouring the terror of the front—hints at the reasons for Sobko’s “immense popularity” amongst frontline soldiers.

Unknown Friends - 25 September 1942

Our armoured cars tore into the village. The gunners got out and quickly took up positions in huts and attics, but the tanks went on ahead. The German defence was broken quickly.

The tank at the head, commanded by Lieutenant Sokolov, made it through the whole village without stopping, blasted a hut hiding a camouflaged anti-tank gun. For a second, the debris covered the tank, but on it went in pursuit of the German cars escaping up the road away from the village, kicking up yellow dust in their wake. Inside the tank it was stuffy and hot and smelled of oil. Sokolov opened the hatch a little. The wind seemed cool; the freshness helped Sokolov’s sore head.

The Germans were escaping but they weren’t in disarray; they would soon be ready to take to the defence once more. They’d been repelled from the village, but they weren’t yet beaten. The lieutenant was certain that the battle would start up again immediately. But at that very moment, a shadow descended on his tank and a sound rang out in the air. A plane adorned with a red star was falling from the shining expanse of the sky toward the field’s scorched autumn grass. The wind whistled through its wings.

Sokolov could do nothing to help the pilot. He froze in anticipation. He watched as the plane descended, nearing the earth, and thought that before his very eyes it would crash and the pilot would perish.

But the plane didn’t crash. Its wheels touched down on the dusty grass—this was piloting of the very best school. Out of the cockpit and onto the wing leapt the pilot. He made for the engine. The tank was at a fair distance from the plane, so that Sokolov couldn’t see the pilot’s face. He wanted to drive his tank closer and congratulate the pilot on his skilful achievement.

The tank began to move forward, but at that exact moment, some Germans came out of a hollow between Sokolov and the plane. Nobody could stop them. Nobody could defend the pilot, who was occupied fixing his engine.

Sokolov’s tank advanced at full speed, making a circle as its machine guns fired away. The Germans went to ground. They were still far from the pilot, so they couldn’t hinder him any longer. They were forced to lie where they’d fallen, not a single step closer. The tank drove around in a circle. The plane with the red star stood at its centre; the field immense and still as a frozen sea.

As he fired from the turret gun, Sokolov occasionally glanced at the pilot. He was still busy with the engine. The Germans began to outskirt the tank along a more distant hollow. Now no one tank could hold back their advance. Sokolov, though, took another look at the wide, flat field. He could no longer see the plane, only clouds of dust kicked up by the propeller and a light shadow hanging over the steppe.

Sokolov smiled with satisfaction. It was a great feeling to know that he’d managed to save a comrade’s life and a plane. The tank turned around and set off for the village, where the battle continued.

Shells were falling around the tank, exploding over the village, and striking and igniting the huts. The Germans were firing from a great distance. This was the prelude to a counterattack. Sokolov drove behind a hillock and stopped the tank to wait for the approaching Germans. He assumed they’d throw their own tanks into the counterattack—his tank, hard to see, would wait in ambush and do all sorts of damage to them.

More than an hour went by. The German tanks didn’t appear: the infantry went on the attack. They would have to traverse several kilometres to reach the village. The tank commander decided to emerge from his cover and rejoin his own forces.

Suddenly, a shell exploded right by the tank. The shrapnel could not penetrate its armour, but struck the tracks. A shard wedged itself between the links. The tank could no longer move.

At first, Sokolov couldn’t comprehend what had happened. He quickly opened the hatch, hopped out of the tank and fell to the ground. Bullets whizzed and clattered over his head, hitting the tank’s armour. The Germans may have been far from the village, but there was just a few hundred metres between them and the tank. Like serpents they crawled along the ground. They’d seen what had become of the tank, so slowly, surely, they advanced. The tank was now their prey.

Sokolov lay on the dry, dusty ground. The enemy fire kept him down; he could not reach the damaged track. Then, from high in the blue sky, out rang the mighty, assured roar of an engine, and the shadow of spread wings again was cast over the tank. An angry, ferocious fighter plane was tearing across the field. Firing its machine guns, the plane flew in a great circle with the tank at its centre.

The red stars on the plane’s wings were crystal clear to Sokolov. He desperately wanted this plane to be the same one he’d defended just a quarter of an hour previously on this very field. The plane flew over the field. Little puffs of dust flew up wherever the pilot fired. The Germans tried to hide, using every last little bump in the ground--but it’s hard to hide from a plane on the steppe.

Sokolov seized this moment, when the plane was distracting the Germans, to make it to the damaged track. It took several minutes to hammer the shrapnel out of the track, but now the tank was ready to move and make war again.

Sokolov leaped onto the vehicle, waved with his black tank regiment helmet and called out some joyful words of greeting to the pilot. The pilot saw everything, understood everything. Delighted with his success, he turned a dizzying figure over the tank. He span his plane around several times, then whizzed sharply upwards, disappearing into the blue sky.

The Germans went back on the attack. The battle wasn’t over yet.

***

Several days later, Tank Commander Sokolov, Flying Officer Kabanov, and several of their comrades, arrived at a hut in a derelict hamlet on the steppe. They were silent, but in a celebratory mood. They had no desire to boast of their feats. They were businesslike men who well knew the old saying: “Act first, talk later.” They barely knew each other, and did not intend to speak of the struggle for the autumn steppe. For them, it had been just another day’s battle--one which had albeit ended fortunately, since they had managed to save a comrade’s life. There was nothing to talk about; it was all too trivial, too ordinary.

A tall, greying man arrived. He was carrying a large suitcase filled with boxes of medals. Tank Commander Sokolov and Flying Officer Kabanov were awarded the Red Star. They pinned their medals to their lapels, firmly shook the hand of the tall, grey-haired man and silently—triumphantly—went out into the darkness of the Volga-side autumn steppe.

They entered the mess and accepted their comrades’ congratulations. Neither of them spoke of that day’s heated fighting; neither of them knew that the man who had saved their life stood alongside. They each drank a glass of wine, smiled at each other in parting, and went their separate ways.

July 18, 2020

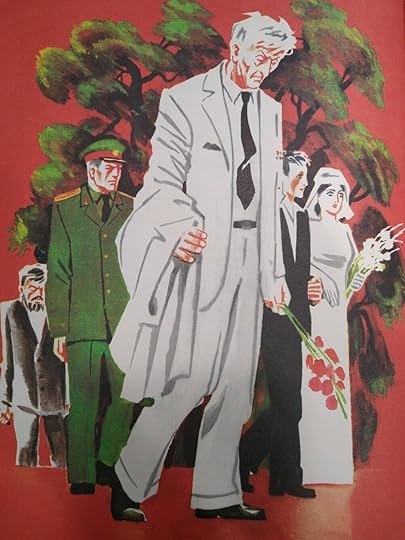

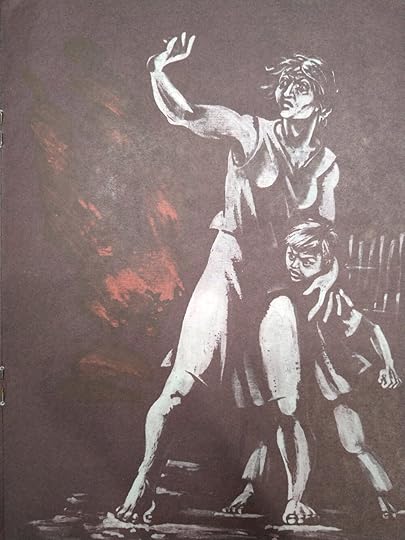

The Eternal Flame (Timofey Belozerov)

Timofey Belozerov was a well-known Soviet children’s poet and author. Although heavily published in the USSR, Belozerov seems to be mostly forgotten today.

Belozerov’s poem The Eternal Flame was published in 1985, when the Soviet government held elaborate celebrations for the fortieth anniversary of victory in World War 2. In Belozerov’s work, the narrator tells a brief story of a visit to an eternal flame—presumably the one in Moscow—and, somewhat scoldingly, explains the debt today’s children owe to those martyred in the war. Combined with the rather graphic and dark illustrations, this is quite a shocking piece compared to representations of war shown to western children.

The Eternal Flame

I walk in the memorial park,

Where the stones

are smooth as glass.

The melancholy sound of music

Weighs sad, bright on my heart.

The iron banners mute,

Marble and granite shine,

The still nighttime dew,

Remains too on the lawn.

That’s not a firebird flapping

Its pensive, fiery wing—

But a flame in bronze chalice

Where memory lives long.

Under shaded trees in the garden,

It burns like sun in grey skies,

Two pioneers stand guarding,

Holding firm a pair of rifles.

The remains of a general

And a private are buried here.

In the quiet, both painful memory

And iron tanks rumble near.

My young impatient friend,

Reader of these lines!

You’re free, your joy has no end.

You’re living in carefree times.

Everything is easy for you:

You have space and light too,

You’re fed and clothed by your parents.

But it could’ve been

quite different…

Back on one chilly morn,

When first the flowers bloom,

Airborne armadas swarmed,

Their fascist crosses loomed.

Buckled helmets swayed,

With mess tins loudly jangling,

Gleaming guns sprayed

Bullets at women and children.

Tank tracks noisily thundered,

Villages, fields were plundered.

And your life was like a spark,

A little star, quiet in the dark.

Sometimes it hardly shone,

And sometimes was so pale,

That it was very nearly gone;

you could have

ended up a slave.

A slave with no name or kin,

No right to think or dream,

No right to cry out, proud within,

“Country, Freedom, Russia!”

…to such slavery we would not yield!

A foreign flag in the breeze,

Foreign birds in the field,

Foreign berries on our trees.

Don’t dare learn or utter

A single Russian word or letter.

Learn to mend and iron hems,

For those fattened pigs,

And don’t dare challenge them.

Learn to scrape and bow and dip,

But don’t you dare hide from the whip.

Don’t you dare

Don’t you dare

Don’t you dare

Don’t you dare!

Those who hid from all that strife,

Weren’t those who saved your life.

They burned up hot in our planes,

And froze in trenches snowy,

They drowned in the seas and the rains,

Facing death to kill the enemy.

Our soldier is bandaged, bloody.

His gun on the earth laid,

He wields a heavy bundle,

Of anti-tank grenades.

In the grey German landscape,

Driven by rage and fury,

He confronts the tigers and panthers.

He leaves behind death

And welcomes immortality

With a cry of “No step back!”

His every step fatal,

Until over the Reichstag

He spies flying our

Soviet

Flag!

…the starlings

hurry o’er the park,

Flying to the fields, away from the dark.

An old lady with a bouquet,

Approaches the Eternal Flame.

From her shoulders, thin and old,

Slips

a mourning

shawl,

In her eyes, tired and cold,

Are hope, pride, sadness—all.

She visits the grave her son lies in,

In hand a

single flower…

He fell at the walls of Berlin,

With bloodied, beaten brow,

With paid-out telephone spool,

With brickdust on his shoulders,

With sweaty cap tied to tunic,

With a single word—“Mama”—

He was laid to rest…

Today is splendid and gracious,

Clouds float higher, more and more,

And out, up, from the chalice,

Rises the flame, to burn forevermore.

April 15, 2020

From Stalingrad to the Stars: Science Fiction and Memory in Putin’s Russia

What happened to memory of Stalingrad after the fall of the USSR?

How are ultra-nationalist Russian groups reproducing memory of Stalingrad?

Why is science fiction a perfect vehicle for the expression of right-wing macho Russian dreams in literature?

Read on to find out the answers!

______________________________________________________

Stalingrad was one of the Second World War’s most important and bloodiest battles. Soviets and Germans engaged in street battles throughout fall 1942, before an improbable Soviet counter-attack in late November comprehensively turned the tables, encircled the German 6th Army and, eventually, forced its surrender in early February 1943. The Soviet press instantly painted Stalingrad as a ‘the greatest victory of the war’ (“Inostrannaia Pechat’”), that, in spite of its enormous human and material cost, had laid the groundwork for the defeat of Hitler's Eastern campaign and therefore the entire Third Reich.

Soviet authors quickly produced dozens of works about Stalingrad: Konstantin Simonov's Days and Nights (1944), Viktor Nekrasov's In the Trenches of Stalingrad (1946) and Vasilii Grossman’s sketches from the battle and For a Just Cause (1952) were printed and reprinted in vast quantities. In spite of the suppression of Grossman’s Life and Fate, unpublished in the USSR until 1988, Soviet writers constantly returned to the theme of Stalingrad. Nina Tumarkin describes the Soviet obsession with the politicized memory of the War as a ‘Cult of the Great Patriotic War’. This Cult legitimized the power of the USSR’s incumbent rulers by lauding the sacrifices of the older generation, which burdened younger generations with an unpayable ‘debt’ (Tumarkin 133). An inflated myth of the sacrifices of heroic Stalingrad was at this Cult’s center.

During the socioeconomically turbulent 1990s, the Eltsin government did little to support the myth or memory of Stalingrad. While Stalingrad has now almost faded from living memory, its myth – as part of the Cult of War – has been revived under the increasingly militarized Putin regime (Wood). In October 2013, Fedor Bondarchuk's Stalingrad was released at the Russian box office. Its mostly state-provided $30m budget made it one of the nation's biggest ever productions. Cinema-goers flocked to Stalingrad. Despite mixed reviews, the film took over $66m, including the Russian Federation's most profitable opening weekend in history.

However, cultural production today is not limited to government-funded major productions. In this essay, I examine the importance of the Stalingrad myth to the users of In the Whirlwind of Time (V vikhre vremen; VVV), a Russian-language online forum founded in the mid-2000s. Dedicated to the discussion and creation of alt-history and science fiction books, VVV has become a production line for pulp fiction works spanning the gamut from medieval fantasy to science fiction works. Although it has just 2000 registered users, 400-500 visit every day, and the most successful users have published dozens of books with large Moscow-based publishers (see “Bibliografiia uchastnikov foruma”). A great number of these relate to Second World War themes, and especially Stalingrad.

Budding and experienced authors turn to forum users for help on every subject. They post drafts of pages or chapters and receive feedback on every step of the writing process. These discussions are usually littered with confrontation and vicious insults. The most important issues, especially those relating to Second World War themes, are those of ‘truthfulness’ and ‘morality’: forum users are quick to gang up on those who veer from a Russian nationalist, pro-Soviet viewpoint. While the arguments over what is true are bitter, the prevailing viewpoint is that Soviet fiction is ‘true’: the forum users’ standards for memory are not based on rigorous, historical enquiry familiar to Western readers, but on a literary corpus passed down from their fathers’ generation. Collaborative work is extremely popular on the forum: ‘Fedor Vikhrev’, a pseudonym for a large group of users who co-author the works, has published several works. The ‘truth’ here is a shared, subjective concept.

VVV is dominated by extreme Russian patriotic and nationalist voices. In principle, members can be banned for ‘fomenting ethnic and religious hatred’ (“Pravila”), yet this does not appear to extend to Westerners, especially Americans, who are regularly and openly abused on the forum and in print editions, where they effectively stand in as a modern replacement for Nazi villains, plotting dastardly moral crimes against Russia and the Russians. While one might expect an online forum to broaden geographical borders and expand the scope for literary creation, here it actually gives a relatively small group of users a chance to share and voice their strong opinions. Without the internet as a means to make contact, it is unlikely that a group like this would exist: while nationalist military-patriotic culture in the 90s was mostly restricted to fermenting in extreme conservative literary journals, especially Nash sovremennik (Our Contemporary), its adherents now find like-minded men (there are almost no female users) with ease.

Sharing their sense of the 1990s as a catastrophic, Western-led socio-cultural vacuum that lacked the communist moral compass, these men desperately try to recreate and rework the past in order to recover the lost Soviet era. Building on Soviet literary heritage, they create an ever-more mythical concept of Stalingrad as nationalist ideology, rather than historical reality. Where Stalingrad saved the Soviet Union in 1943, now these writers use its symbolic value to suggest that it can save 21st-century Russia from Western immorality.

In this essay, I do not mean ‘myth’ as a lie to be uncovered. I use it in Northrop Frye’s sense: myth informs our understanding of poetry’s interconnectedness. Communicated by repetition and the resultant (usually subconscious) expectation of the reader, pure myth indicates absolute 'metaphorical identification' with the apocalyptic—the realization of the impossible, which is usually contained by nature's limiting force. This is to say that myth is the opposite of naturalism: the storyteller has total control over events thanks to his

To establish plausibility, the purely mythological in most fiction appears in 'displaced' figurative form. In literary terms, this means the movement toward the absolutely fictional. Here, this implies the suspension of all disbelief at the implausibility of the events of Stalingrad as presented in fictional narratives, which instead function as part of a symbolic process of establishing communist utopia through the 'resurrection' of the USSR's war at Stalingrad. In spite of the misleading name of ‘Socialist Realism’, the USSR’s state-sponsored writing system, Soviet authors strove to depict this symbolic value, [see K Clark History as Ritual] rather than ‘reality’. In this sense, the writers of VVV, through their insistence on community-monitored ‘truthfulness’ through adherence to a certain Stalingrad narrative, move towards Frye’s mythical. This process is at its strongest in sci-fi and alt-history works relating to Stalingrad, where the impossible becomes ’true’ through its symbolic content: the addition of fantastic, physics-warping time travel motifs to the Stalingrad story focuses all narrative attention on the storyteller - the author - rather than on the ‘facts’ of the history of Stalingrad.

While the fantastic content of the users’ writing is manifestly not realistic, their readers are keen to praise work that they consider to be ‘true’. This is a reflection of the Soviet penchant for fictionalized history – indeed, Grossman and Simonov's war reportage is intended to be inspirational, not informative – and the popularity of the semi-fictionalized ‘documentary tale’, or ‘fictionalized non-fiction’, as Maria Balina puts it (194). In Soviet eyes, works are true when they repeat certain key elements of an established narrative: these sci-fi works may appear to be left field, but they are a continuance of the Soviet literary tradition. This is why forum users are keen to read similar stories time and again, and why borrowing ideas is seen as homage rather than plagiarism. The works at hand share many ideas, including uncannily similar events, turns of phrase and major plot details, such as the mechanism by which their protagonists travel through time.

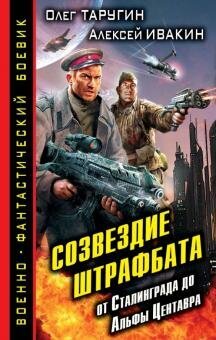

In this essay, I focus on three works by forum users: Oleg Tarugin and Aleksei Ivakin’s The Shtrafbat's Constellation: From Stalingrad to Alpha Centauri (2013); Aleksandr Kontorovich’s Black Infantry: Shtrafnik from the Future (2010); and Vladislav Koniushevskii’s The Attempted Return (2008).[2] Each work demonstrates key motifs relating to time travel as a major plot device, to Soviet literary heritage, and to the desire to resurrect the moral certainty of the USSR. All three were praised by users for their truthfulness and released by major publishers.

Tarugin and Ivakin, last-generation Soviets in their early 40s, are both forum users. A teacher and a pediatrician, they are educated professionals responding to the crisis of the generation that matured in the late 80s and difficult 90s. From Stalingrad to Alpha Centauri was written on VVV: accordingly, the authors thank the users for their help in creating the work (“Ot avtorov”). Forum users received the work as an instant classic. They singled out the work’s patriotic theme of generational reeducation for praise: according to one, the novel is good to ‘teach those who have forgotten the war to be men, to die for the Motherland, to kill and to win’. One user who wondered how bloody-minded shtrafniki from the past would suddenly want to patriotically save the world was abused by regular users, who attacked him as an ‘idiot’ and ‘brain-washed’ (“Verite li v sebe, avtory?”): truthfulness and patriotic thinking does not require, for these Russians, rigorous or rational enquiry.

From Stalingrad’s events, set in the year 2297, echo those of the Second World War. Humanity is now united and genetically engineered to remain peaceful. As a result, they have forgotten the Second World War and how to fight. Mysterious, bestial lizardmen suddenly attack human extraterrestrial colonies, overcoming the helpless defenders and slaughtering the local population (i.e. they reiterate the German invasion of 1941). The human ‘universal government’, looking for a miracle, sifts through time to find the ‘best soldiers in history’: a shtrafbat of Stalingrad veterans. They pull the soldiers from the moment of their deaths in the 1940s through time to 2297. There, they ask them to recreate the seeming impossibility of the Soviet last-stand victory at Stalingrad.

With their military acumen and sheer bravery, the shtrafbat triumphs in a Stalingrad-like victory on Earth, conveyed through images of a hellish world of total war (‘The town was burning, the asphalt was burning, the concrete was burning, the glass was burning’, Ch.1) that reminds us of images from Soviet victory of a burning Stalingrad (e.g. see Grossman 1942). Having thus averted the danger to Earth (i.e. the threat in 1942 to Moscow and the USSR), the shtrafbat makes its advance towards the lizards’ home planet, analogous to the post-Stalingrad march on Berlin. A further battle takes places at ‘Kotel’nicheskii’, whose name alludes to Kotel’nikovo, a town close to Stalingrad that saw major fighting in 1942. Ivakin and Tarugin directly compare the ruins of a colony to those of Stalingrad and Dresden (Ch.3): ‘Stalingrad' is not only the most significant event of the future war, it is also the standard for destructive sacrifice and suffering in war.

It transpires that the lizard men are battery-farmed by shadowy members of the universal government, who have hatched a barbaric plot to control human overpopulation through mass destruction. The shtrafbat discovers their experiments on humans, which take place at a concentration camp-like extraterrestrial base. Here, though, experiments on humans are products not of Nazi racial ideology but of Western European rationalism, and inspired by Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford prison experiment: ‘How are these modern scientists different from the bloody vivisectionists of the Third Reich?’ (Ch.3), asks one time-traveling soldier. Having saved the day, the shtrafbat reeducate the population, encouraging Soviet participatory activities like archeology as a means of preserving the memory of the fallen. The shtrafbat are idealized soldiers who die for the Soviet Union in 1942, die again for humanity in the future, and teach ‘generational debt’ to the young: at the story’s heart, Stalingrad is the symbolic moment that allows them to move towards these heroic feats.

Aleksandr Kontorovich, a veteran of the Soviet-Afghan War and VVV user, writes works ranging from medieval fantasy to Second World War alt-history. His Black Infantry is a typical time travel alt-history work. Unlike in From Stalingrad, Kontorovich’s protagonist, Kotov, falls backward through time, from the 2000s present to 1942, giving him the chance to refight the War and achieve an (even) better result.

Praised for his ‘morality and ethics’ (“Verite li vy sebe, avtory?”), Kontorovich is one of the forum’s most popular authors. Black Infantry is written for a ‘small circle of familiar faces’, including several named users of VVV (Foreword). Kontorovich claims it is based on real people and events, but by mixing stories from the past with characters from the present he indicates an important trope: the VVV authors see current Russian military action around the nation’s periphery as a moral, ideological continuation of the Second World War.

Kotov is a brutish, individualist special forces soldier who has served in Afghanistan and Abkhazia. A secret government agency experimenting in time travel sends him back to 1942. Kotov’s fate is threatened not by Nazi forces, which he always brushes aside with ease, but by an opposing American intelligence agency. In the past, Kotov relives the retreat from Kharkiv to Stalingrad. Armed with his prescient knowledge of future events and military tactics, he plays through the VVV fantasy of ‘saving’ Russia in both the past and present, thereby repaying the debt to his grandfathers’ generation. Kontorovich borrows stories from Soviet Stalingrad authors to rewrite the myth, implying that Kotov’s battles have a Stalingrad-like eternal importance.

Vladislav Koniushevskii, a bodyguard, soldier and author of several works, is an active VVV user. He is the most overtly nationalist of the authors here: on his profile page on authors’ site Samizdat, he urges forum members to ‘shit on the liberals’. In The Attempted Return, his protagonist, Lisov, another macho military specialist, falls through time to 1941 after a blow to the head. Lisov relives the entire War, using his knowledge of the future to advise Stalin personally and ‘invent' a number of pieces of modern military technology. [3] He regularly visits the front and wreaks personal havoc on Nazi opponents. Thanks to Lisov’s foreknowledge, Stalingrad is avoided. He therefore negates the generational debt by single-handedly ‘winning’ Stalingrad. As a result, the Germans lose the War, and the USSR remains a dominant world power in the 21st century: there is no turbulent 1990s, and Western dominance never happens. The rewritten future ends in an epilogue set near an untouched Stalingrad, now at the center of a still-extant USSR. Unsurprisingly, the book was well received: one user writes that ‘Koniushevskii’s great achievement is in correcting the political direction of the USSR, which he does efficiently and absolutely truthfully. He has set the standard for years to come’ (“Morskoi Volk-2 VladSavin”).

All three books share formal features that link their origins to Soviet works. They reiterate Soviet stories, recreate the atmosphere of the Soviet era in both past and present, and adopt Soviet phraseology, a key feature of Socialist Realist writing. The similarity of events across the books (and across works penned by VVV users) indicates a key mode of Soviet writing: inspirational, ideologically sound stories endlessly rewritten with minor changes.[4] This is true of the Stalingrad story: over a hundred almost-identical works of fiction about the battle were printed in the five years before perestroika alone. Soviet writers, rather than reflecting reality, were expected to create reality (Markov 15).

Accordingly, all three authors borrow symbolic locations and events from their predecessors’ (and each others’). Tarugin and Ivakin’s shtrafbat visit symbolic locations around Stalingrad in the 23rd century. The authors also recreate a significant scene from Simonov’s Days and Nights when Krupennikov, the battalion commander, looks to the sky’s starry vastness as an escape from Stalingrad. Krupennikov, unlike his predecessor, Simonov’s Saburov, takes to the stars and saves the universe: the writers’ work has its origins in Soviet fiction, but rewrites it with limitless possibilities.

An analogous incident occurs in Kontorovich’s Black Infantry. Kotov’s first action in the past is a direct rewriting of Nekrasov’s battle for the Mamaev kurgan (a major hill in Stalingrad) from In the Trenches of Stalingrad. The protagonists in both works are asked to conduct an almost impossible operation to take German bunkers. Yet where Nekrasov’s soldier distrusts maps and strategy, operating by intuition in the chaos of battle, Kontorovich’s character just turns the map of the hill ‘here and there, every which way’ (Сh.24). He considers all possibilities to find the best method of attack, carrying it out and killing dozens of Germans. The exaggerated abilities of the time traveler give the current soldier the chance to eliminate the burden of generational debt and save the present. These borrowed elements, ramped up with the fantastical possibilities of genre writing, demonstrate the writers’ debt to the Soviet literary heritage in creating their own, modern myths.

As well as the plots, which reiterate and replay the trajectory of the Second World War, with Stalingrad its moral centre, the authors literarily recreate the cultural feel of the Stalinist 1940s by referencing seminal works. Tarugin and Ivakin’s Krupennikov, the good Soviet citizen, disapproves of his commissar’s enjoyment of Western rock music in the future, but praises Aleksandr Tvardovskii’s popular wartime poem Vasilii Terkin. Other references are to the films Chapaev and The White Sun of the Desert, the television serial 17 Moments of Spring, and popular war-era songs such as Oh, the Roads….

The VVV writers adopt another typical element of Soviet writing style, the use of blochnoe pis’mo (‘block writing’), the repetitive, often stilted, use of set phrases. Aleksei Yurchak suggests that blochnoe pis’mo allowed Soviet citizens to demonstrate their adherence to ‘correct’ Marxist-Leninist thinking (Yurchak 47). Koniushevskii’s Lisov loves Stalin as the ‘best friend of the Soviet people’ (Ch.3), a typical phrase used to describe the leader in propaganda. Tarugin and Ivakin claim that ‘the towns of Belarus […] will be written forever into the heroic annals of the Red Army’ (Ch.1), a wording frequently used in Soviet journalism; Kontorovich describes Stalingrad as ‘impenetrable [kromeshnyi] hell’ (Ch.37), a phrase associated with the battle from 1942 and often adopted as a story title by later writers. By unironically incorporating Soviet clichés, the VVV authors express a dual sense of belonging: to the Soviet past, and to the other forum members.