Eric Enno Tamm's Blog: Eric Enno Tamm

April 13, 2014

75th Anniversary: The Grapes of Wrath, first novel to herald Age of Ecology

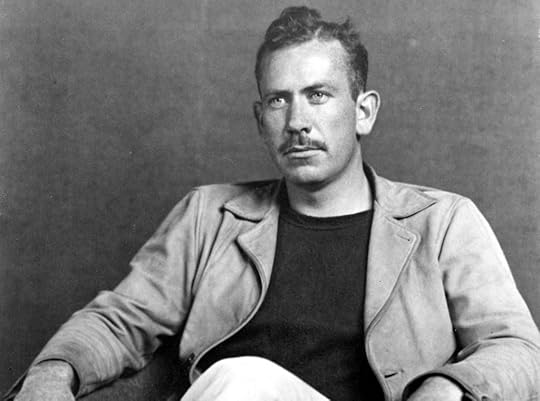

John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath is a ghastly portrait of poverty, filth, human misery, starvation, and injustice. It tells the story of the Joad family, Oklahoma tenant farmers or “Okies,” dispossessed from their Dust Bowl homestead by bankers and wealthy landowners. In a jalopy, the Joads go west along Route 66 in search of greener pastures, the proverbial Promised Land, only to confront the scorn of Californians.

Steinbeck imbued the novel with an essentially ecological message, about how “machine-man” with his iron tractors loses connection to the land, destroys the land, then consequently destroys his own humanity.

His political observations in the novel, one literary scholar has pointed out, “grew largely from his interest in Ed Ricketts’ ideas.” (Ricketts was a pioneering marine ecologist and the inspiration behind the Jim Casey character in Grapes.)

The reaction to Grapes—which weighed in at a mammoth 850 pages—shocked even Steinbeck, who thought it wouldn’t be a popular book at all and advised his publisher to “print a small edition.” After one month, 83,000 copies were in print, a number that would swell to 430,000 by year’s end, a staggering success then and now. Since the first edition appeared seventy-five years ago, the novel has never been out of print or sold less than 50,000 copies annually, in English alone.

Ecstatic reviews rolled in from critics at Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s and North American Review. Clifton Fadiman at The New Yorker summed up the novel’s power: “If only a couple of million over comfortable people can be brought to read it, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath may actually effect something like a revolution in their minds and hearts.” Such praise, however, only fed the hysteria of detractors—namely the Associated Farmers, conservative politicians, the clergy and communist witch-hunters.

Steinbeck wrote the novel in a marathon session—ninety-three working days over five months starting on May 26, 1938. It physically and emotionally crippled him and his wife Carol, who served as his stenographer and initial editor and who came up with its title from a verse in “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” With the manuscript completed in early 1939, they moved into a secluded Spanish-style ranch near Los Gatos, seventy-five miles from Monterey. Medical tests at the time showed that Steinbeck’s metabolic rate was “shockingly low” and neuritis left him bedridden for two weeks. The publication of The Grapes of Wrath in April of that year thus heralded the worst of times for Steinbeck, “a nightmare all in all.”

Hollywood stars quickly came knocking at his door—Burgess Meredith, Charlie Chaplin, Spencer Tracy, Anthony Quinn—the “swimming pool set” as Steinbeck dubbed them. They became occasional visitors around the pool at his Los Gatos home. He was offered $5,000 a week to write screenplays, and the film rights for Grapes sold for $75,000, one of the highest prices ever paid for a novel at the time.

Director John Ford turned it into an Academy Award–winning blockbuster in 1940, starring a young Henry Fonda as Tom Joad, a character who has been ranked as one of the greatest screen heroes of all time by the American Film Institute.

It was too much for John Steinbeck—the money, adoration, invidious innuendo and threats. “This whole thing is getting me down,” he wrote his agent, “and I don’t know what to do about it. The telephone never stops ringing, telegrams all the time, fifty to seventy-five letters a day all wanting something. People who won’t take no for an answer sending books to be signed. I don’t know what to do.” By the beginning of July, the Los Angeles Times reported that the famous writer had retreated to “a secluded canyon three miles from [Los Gatos], and padlocked himself against the world.”

Steinbeck fled to Hollywood that summer to hide out, but also to get away from Carol. Suddenly she seemed to be turning on him too. Her behavior, including bouts of heavy drinking, had become erratic and hateful toward the writer. She had suffered greatly for his career and grew resentful. In Hollywood Steinbeck struck up an affair with actress Gwen (or Gwyn, as she later spelled it) Conger, a petite starlet twenty years his junior.

When Steinbeck returned to Los Gatos he found Carol hysterical. In late July, while at a party in Beverly Hills, she blew up, screaming viciously at her husband in an embarrassing public feud. Distraught and bewildered, John Steinbeck needed help. And there was only one place where he could hide out from his estranged wife, snooping FBI agents, newspapermen and scandalmongers. He ended up at Pacific Biological Laboratories, the home and business owned by Ed Ricketts on Cannery Row.

“Once, when I had suffered an overwhelming emotional upset,” he later recalled. “I went to the laboratory to stay with [Ed Ricketts]. I was dull and speechless with shock and pain. He used music on me like medicine… I think it was as careful and loving medication as has ever been administered.”

By autumn, Steinbeck was spending most of his time on Cannery Row, helping Ricketts with work at the lab and reading science books. He had tired of the “swimming pool set,” which he felt Carol had fostered.

On a number of levels, he sensed he was undergoing some kind of slow death—matrimonially, professionally, creatively, physically. He had barely written a word in 1939, his marriage had effectively collapsed, his health was frail, and war in Europe, which began in September, cast a doomsday spell over his psyche.

“The last two days I have had death premonitions so strong,” he scribbled in his journal on October 19, “that I burned all the correspondence of years. I have a horror of people going through it, messing around in my past, such as it is. I burned it all.” But with death came a rebirth too—a rebirth that would confound many who knew him.

He began an era of “new thinking” which involved the study of science. It became “a sort of sea anchor with which he tried to ride out the storm.” Steinbeck completely abandoned fiction writing and, oddly, wanted to produce a high-school level textbook on the marine biology of San Francisco Bay under Ricketts’ tutelage. Why, at the height of his literary career, with cash and kudos flooding in, would America’s best-selling author abandon the very craft he seemed to have mastered? The answer eluded many literary critics.

One of the greatest American men of letters in the twentieth century, Edmund Wilson, set the tone—and one can arguably say the misunderstanding— for a generation of critics who excoriated Steinbeck, notwithstanding his popular appeal. “Mr. Steinbeck almost always in his fiction is dealing either with the lower animals or with human beings so rudimentary that they are almost on the animal level. . . , ” wrote Wilson in an influential review of The Grapes of Wrath. “This animalizing tendency of Mr. Steinbeck’s is, I believe, at the bottom of his relative unsuccess at representing human beings.”

Steinbeck’s fiction was weak, flawed, belittling, Wilson argued, because his characters were simply not human, or not human enough. But Wilson completely missed the philosophical and scientific import of what Steinbeck was actually saying.

Anthropocentricism—the placing of human beings at the center of the universe—has been the very foundation of Western thinking, from ancient times through the Age of Reason into modernity. In eras bubbling with religious and imperial zeal, society saw nature as a gift from God, and its exploitation as a divine right. “The world is made for man,” Sir Francis Bacon wrote, “not man for the world.” The Enlightenment harkened a new world in which science would give mankind absolute dominion, in a biblical sense, over nature. With the new inventions of the Industrial Revolution, humans polluted and plundered the planet’s bounty: the soil, oceans, forests, lakes and rivers, and their myriad creatures.

Singularly, however, one event effected a sea-change in this man-centered worldview in North America. In the 1930s, huge dust storms blew over the Great Plains, transforming the sun into a lusterless ball in a gray sky. The Dust Bowl, vividly described in the opening chapter of The Grapes of Wrath, is arguably the worst environmental catastrophe of the twentieth century. It destroyed entire harvests, displaced some 300,000 farmers and precipitated violent social unrest and even starvation. A group of pioneering Midwestern plant ecologists concluded, however, that the Dust Bowl was a wholly man-made disaster; misguided farming practices had destroyed the native sod which was a vital buffer against wind and drought.

It’s a conclusion that resonates throughout Steinbeck’s epic novel—“The land bore under iron, and under iron gradually died,” he wrote—and made John Steinbeck, argues his biographer, “the only major literary figure of his time to embrace and bring to his writing one of the most—if not the most—important concepts of the twentieth century, a concept that has changed radically the way man views himself and his relationship to his environment.”

As Galileo rankled the Vatican for confirming that the earth was not the center of the universe, so too was Steinbeck attacked for trying to show that the earth itself was not a man-centered world. Humans were biological beings, Steinbeck suggested, and were thus united by the same natural laws that shape the rest of the animal kingdom. He was not denying the uniqueness of the human species—its distinct cognitive, linguistic and emotive powers—as Wilson contended, but rather recognizing that humans were one with nature.

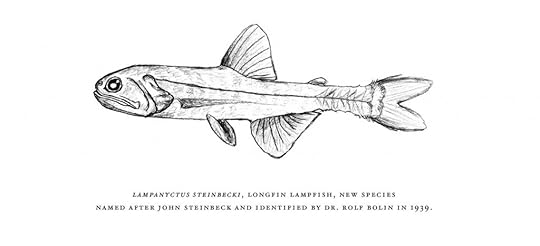

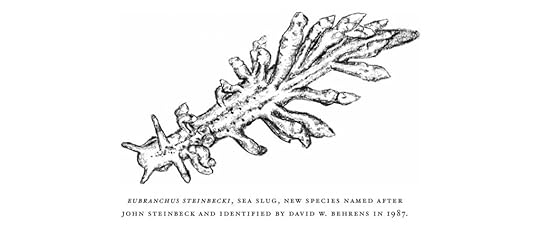

The fate of civilization, in effect, rests perhaps less on how man treats his fellow man than on how man treats the environment. That humanity’s survival depended on the health of the global commons—a fact that sounds trite today in light of global warming, species extinction and habitat destruction—was a prophetic statement half a century ago. And while literary scholars criticized Steinbeck for animalism and gross sentimentalism, it has been the scientific community who has largely vindicated the writer, proclaiming Steinbeck a conservationist, an ecological prophet and the first American writer to herald the Age of Ecology.

John Steinbeck knew, as Ricketts had once written, that “the study of animal communities has this advantage: they are merely what they are, for anyone to see who will and can look clearly; they cannot complicate the picture by worded idealisms, by saying one thing and being another: here the struggle is unmasked and the beauty is unmasked.”

In The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck unmasked the human struggle and was persecuted with “worded idealisms” for doing so. By turning to marine biology and the tide pools, he hoped to apply his own eye to this “peep hole,” and to fish for the same beauty and struggles among animal communities that he had unmasked among human society. “Our fingers turned over the stones,” Steinbeck said of seashore collecting, “and we saw life that was like our life.”

* * *

Essay adapted from Beyond The Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, The Pioneering Ecologist Who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell.

January 11, 2012

“A rich tapestry of narratives,” says Uyghur human rights activist

“Tamm’s writing deftly conveys readers from 1906 to 2006, from St. Petersburg to Beijing, intertwining his own experiences with those of Mannerheim,” writes Amy Reger, a Uyghur human rights activist in a book review in the Asia Sentinel. “His prose and dry wit, which earned him the 2011 Ottawa Book Award for Non-fiction, sustains readers masterfully through a grand scope of nearly 500 pages,”

“The Horse that Leaps Through Clouds,” she concludes, “goes far beyond clichéd notions of the Silk Road and the modern rise of China, and imparts to readers a discerning look into the marginalized people and groups living on the geographical and economic edges of Chinese society. The book is unique in its understanding of the methods of control used by paranoid leaders attempting to maintain power in the face of myriad forms of discontent. The travels and observations of both Tamm and Mannerheim outline the mundane difficulties and the more agitated discord created by regimes slow to embrace political reform but, in China’s case at least, experiencing tumultuous economic reforms. It is left to the reader to predict whether or not the side effects of Beijing’s reticence to embrace fundamental reforms will take cues from history, and how those living on China’s periphery will react to continued pressure from above.”

"A rich tapestry of narratives," says Uyghur human rights activist

"Tamm's writing deftly conveys readers from 1906 to 2006, from St. Petersburg to Beijing, intertwining his own experiences with those of Mannerheim," writes Amy Reger, a Uyghur human rights activist in a book review in the Asia Sentinel. "His prose and dry wit, which earned him the 2011 Ottawa Book Award for Non-fiction, sustains readers masterfully through a grand scope of nearly 500 pages,"

"The Horse that Leaps Through Clouds," she concludes, "goes far beyond clichéd notions of the Silk Road and the modern rise of China, and imparts to readers a discerning look into the marginalized people and groups living on the geographical and economic edges of Chinese society. The book is unique in its understanding of the methods of control used by paranoid leaders attempting to maintain power in the face of myriad forms of discontent. The travels and observations of both Tamm and Mannerheim outline the mundane difficulties and the more agitated discord created by regimes slow to embrace political reform but, in China's case at least, experiencing tumultuous economic reforms. It is left to the reader to predict whether or not the side effects of Beijing's reticence to embrace fundamental reforms will take cues from history, and how those living on China's periphery will react to continued pressure from above."

October 28, 2011

Ottawa Book Award for Nonfiction Winner

At the National Library and Archives, Mayor Jim Watson announced that I won the 2011 Ottawa Book Award for Non-fiction, beating out literary and journalistic heavyweights Charlotte Gray, Tim Cook, Roy McGregor and Martin Lawrence.

At the National Library and Archives, Mayor Jim Watson announced that I won the 2011 Ottawa Book Award for Non-fiction, beating out literary and journalistic heavyweights Charlotte Gray, Tim Cook, Roy McGregor and Martin Lawrence.It was quite an an honour to be nominated as a finalist among such a distinguished group, literary icons who've published wonderful works on the icons and iconography of this country. I feel incredibly honoured, not to mention lucky, to have won the award.

The jury, consisting of John Geddes, Sarah Jennings and Kerry Pither, said that, in the book, I build "toward a memorable portrayal of the state of modern China. Tamm's account, which combines vivid travelogue, historic inquiry and personal essay, richly rewards readers with a rare blend of epic sweep and intimate meditation."

In my acceptance speech, I thanked the citizens of Ottawa for their support of the arts, especially at this gloomy time when the arts are, in fact, especially important. I also thank my partner and my father, who recently passed away. He gave me a passion for history and a flair for storytelling. He lives on in my books.

I also dedicated my award to a fellow writer, Nurmuhemmet Yasin, whom I write about in my book. He is a Muslim Uyghur writer from Kashgar who is about my age. In 2004, he wrote a story titled "Wild Pigeon" for the Kashgar Literary Review. The Chinese government read it as an allegory for their harsh and brutal rule over their Muslim borderlands and imprisoned Yasin for 10 years. Compared to Yasin, my own travails in researching and writing this book are the equivalent of a weekend at Disney World.

April 28, 2011

Find a book signed by the author

TORONTO

View Bookstores in a larger map

MONTREAL

Chapters at 1171 St. Catherine Street Google map »

Indigo at 1500 McGill College Avenue Google map »

NANAIMO

Chapters at Woodgrove Centre Google map »

KINGSTON

Novel Idea Bookstore, 156 Princess Street, Kingston Google map »

Chapters at 2376 Princess Street, Kingston Google map »

OTTAWA

Nicholas Hoare at 419 Sussex Drive Website »

Chapters at 47 Rideau Street, Ottawa Google map »

Chapters at 2401 City Park Drive, Gloucester Google map »

Chapters at 400 Earl Grey Drive, Kanata Google map »

Chapters at South Keys Shopping Centre, 2210 Bank Street, Ottawa Google map »

Chapters at Pinecrest Shopping Centre, 2735 Iris Street, Ottawa Google map »

PARKSVILLE

Mulberry Bush Bookstore at 102 – 280 Island Highway East Website »

QUALICUM BEACH

Mulberry Bush Bookstore at 130 West 2nd Avenue Website »

TOFINO

Mermaid Tales Books Website »

METRO VANCOUVER

Chapters at 2505 Granville Street and Broadway Google map »

Indigo in Park Royal Mall, West Vancouver Google map »

Chapters at Metrotown, Burnaby Google map »

VICTORIA

Bolen Books at 111-1644 Hillside Avenue Website »

Munro's Books at 1108 Government Street Website »

UVic Bookstore at the University of Victoria Website »

Chapters at 1212 Douglas Street Google map »

March 31, 2011

“A truly inspired journey…” – Kirkus Review

A complicated, ambitious travel adventure through modern Inner Asia, tracing the 1906–08 trek by a Russian spy commissioned by Tsar Nicholas II.

The account of the secretive two-year journey undertaken by Baron Gustaf Mannerheim was not published until 1940, when it was highly admired by Hitler. Journalist Tamm (Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist Who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell, 2004, etc.) only discovered Mannerheim’s Across Asia from West to East recently, and embarked on his trip in 2006 to retrace the baron’s arduous ethnographic journey through the last years of the Qing Dynasty, when modern currents were eradicating the old order—not unlike the cataclysmic changes shaking China to this day. In 1906, Russia was reeling from its humiliating defeat by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War, and enlisted Mannerheim, an officer in the Imperial Army, to undertake the mission through the Asian provinces to gather information on all aspects of Chinese reforms, defensive preparations, politics, colonization and the role of the Dalai Lama (whom Mannerheim got to meet), all in preparation for a possible Russian military incursion. Like Mannerheim, Tamm is intensely curious about the role of China on the world stage, and pursues similar questions about what kind of China will emerge from these wrenching attempts at modernization. Tramping from St. Petersburg to Peking proved a mind-boggling trajectory, penetrating myriad ethnic pockets, Mannerheim by caravan, Tamm by airplane, train, bus and car. Each man encountered all manner of suspicious or friendly people, mishaps and illness. Along the way, Tamm read Mannerheim’s diary—”aloof, impersonal and even churlish at times”—to gain a deeper understanding of this singular character.

A well-edited work chronicling a truly inspired journey, leaving readers hopeful about Chinese progress as well as full of questions.

"A truly inspired journey…" – Kirkus Review

A complicated, ambitious travel adventure through modern Inner Asia, tracing the 1906–08 trek by a Russian spy commissioned by Tsar Nicholas II.

The account of the secretive two-year journey undertaken by Baron Gustaf Mannerheim was not published until 1940, when it was highly admired by Hitler. Journalist Tamm (Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist Who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell, 2004, etc.) only discovered Mannerheim's Across Asia from West to East recently, and embarked on his trip in 2006 to retrace the baron's arduous ethnographic journey through the last years of the Qing Dynasty, when modern currents were eradicating the old order—not unlike the cataclysmic changes shaking China to this day. In 1906, Russia was reeling from its humiliating defeat by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War, and enlisted Mannerheim, an officer in the Imperial Army, to undertake the mission through the Asian provinces to gather information on all aspects of Chinese reforms, defensive preparations, politics, colonization and the role of the Dalai Lama (whom Mannerheim got to meet), all in preparation for a possible Russian military incursion. Like Mannerheim, Tamm is intensely curious about the role of China on the world stage, and pursues similar questions about what kind of China will emerge from these wrenching attempts at modernization. Tramping from St. Petersburg to Peking proved a mind-boggling trajectory, penetrating myriad ethnic pockets, Mannerheim by caravan, Tamm by airplane, train, bus and car. Each man encountered all manner of suspicious or friendly people, mishaps and illness. Along the way, Tamm read Mannerheim's diary—"aloof, impersonal and even churlish at times"—to gain a deeper understanding of this singular character.

A well-edited work chronicling a truly inspired journey, leaving readers hopeful about Chinese progress as well as full of questions.

“A fascinating, sweeping combination of history and travelogue…”

REVIEWED BY QUENTIN MILLS-FENN, UPTOWN, March 31, 2011

REVIEWED BY QUENTIN MILLS-FENN, UPTOWN, March 31, 2011

Eric Enno Tamm’s The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road, and the Rise of Modern China (Douglas & McIntyre) is a fascinating, sweeping combination of history and travelogue.

Tamm takes as his starting point Baron Gustaf Mannerheim, one of those intriguing footnote figures: Russian spy, last Regent of Finland, the recipient of a birthday visit from Adolf Hitler.

On July 6, 1906, Mannerheim set out on a secret mission, charged by Nicholas II to report on China’s increasing power. The Baron traveled through Central Asia on the ancient Silk Road connecting East and West.

Exactly one hundred years later, Tamm duplicated as closely as possible Mannerheim’s journey. Along the way, he visited Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, encountering despotic, brutal regimes, allies of the West in the so-called War on Terror. The area’s plentiful oil and gas reserves also helps in making friends.

Then Tamm finds his way to China itself as he addresses the same questions as Mannerheim did: what kind of role will China play in the contemporary world?

Tamm has also put together an impressive website for this compulsively readable book (www.horsethatleaps.com) with maps and some of the three thousand photographs he took on the trip.

"A fascinating, sweeping combination of history and travelogue…"

REVIEWED BY QUENTIN MILLS-FENN, UPTOWN, March 31, 2011

REVIEWED BY QUENTIN MILLS-FENN, UPTOWN, March 31, 2011

Eric Enno Tamm's The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road, and the Rise of Modern China (Douglas & McIntyre) is a fascinating, sweeping combination of history and travelogue.

Tamm takes as his starting point Baron Gustaf Mannerheim, one of those intriguing footnote figures: Russian spy, last Regent of Finland, the recipient of a birthday visit from Adolf Hitler.

On July 6, 1906, Mannerheim set out on a secret mission, charged by Nicholas II to report on China's increasing power. The Baron traveled through Central Asia on the ancient Silk Road connecting East and West.

Exactly one hundred years later, Tamm duplicated as closely as possible Mannerheim's journey. Along the way, he visited Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan, encountering despotic, brutal regimes, allies of the West in the so-called War on Terror. The area's plentiful oil and gas reserves also helps in making friends.

Then Tamm finds his way to China itself as he addresses the same questions as Mannerheim did: what kind of role will China play in the contemporary world?

Tamm has also put together an impressive website for this compulsively readable book (www.horsethatleaps.com) with maps and some of the three thousand photographs he took on the trip.

March 12, 2011

“A wonderfully fat new work of travel and history…” – The Diplomat

A century ago, Gustaf Mannerheim and Paul Pelliot took a portait with Kurmanjan Datka, the Queen of Alai, near Chigirchiq Pass. A century later, Eric Enno Tamm (far left) posed for a photograph with Sardarbek Ismailov (second from left), the great grandson of Kurmanjan Datka, and his relatives in a yurt atop Chigirchiq Pass.

Book review by George Fetherling in Diplomat magazine.

There’s a connection to be made between Pearl Buck in China and The Horse That Leaps through Clouds (Douglas & McIntyre, $34.95), a wonderfully fat new work of travel and history by Eric Enno Tamm, of Ottawa. As the 19th Century melted into the 20th, writes the author, “Western technology and imported consumer goods — along with radical political ideas, democracy and Christianity — were spreading to every corner of the Chinese Empire,” eliciting not joy but fear in Western capitals. One result was the so-called Great Game (the term popularized by Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim) in which Imperial Russia and Britain, along with France and some other European players, tried to out-spy one another to get control of Central Asia’s oil and other resources (a story well told in The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia and other works by Peter Hopkirk).

Just as this tomfoolery was winding down, Russia sent Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim on a two-year espionage mission from St. Petersburg to the farthest reaches of northern and western China. In later life, Mannerheim (1867−1951) became a controversial national hero in his native Finland and, for a time, its prime minister.

But, in 1906, he was a colonel in the tsar’s service, posing as an ethnographer and travelling with 16 steamer trunks on a mission that would last two years. Mr. Tamm sets out to retrace his famous predecessor’s steps, following the same path across, for example, Eurasia, that “vast continent ruled by a bizarre patchwork of oil-soaked aristocrats, one outlandishly ruthless crackpot and the world’s last major Communist regime and rising superpower.”

A sophisticated journalist indeed, Mr. Tamm gathers observations like gemstones as he crosses “a gauntlet of political and geographical extremes, including some of the world’s hottest deserts, highest mountains and cruellest dictatorships” stretching 17,000 kilometres. He is too clever to pretend he can intuit the future, but he clearly sees the present reflected in the past. For example, he notes while crossing Uzbekistan that “Khanates of blended races and tongues traditionally ruled Inner Asia. People identified themselves according to their local oases, their ruling dynasties and their allegiance to Islam. That didn’t quite fit the Soviet concept of nationality.”