Alexander Billet's Blog

October 30, 2025

Why Do They Come Here?

The following are my opening remarks introducing George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, presented on October 29 at Whammy! Analog Media in Los Angeles. It was sponsored by DSA-LA’s Hollywood Labor committee.

For readers in London, a reminder: I’m presenting my paper “From Modern Materialism to Popular Modernism: (re-)constructing a communist methodology of aesthetics” at the Historical Materialism conference, November 6 at 4:30pm GMT. More info here.

Happy Halloween…

Before George Romero, the zombie as we know it didn’t exist. It’s not just that he sketched out the “rules” of what made a zombie, though he did — in 2025, we’re used to zombies as this unstoppable biological force, fast or slow, not supernatural but very much human-made. Without Romero’s films there would be no shows like The Walking Dead, films like 28 Days Later, no games like Resident Evil, so on.

No, what made Romero’s work such a watershed in horror was that he was the first to paint zombies – he called them ghouls at first – as an avatar for a very specific kind of doom. The modern, late capitalist zombie is both the result of human folly and, conversely, a force of nature, a preventable disaster that we can only watch unfold, powerless to stop it.

As such, you can see that the first film in Romero’s series, Night of the Living Dead, dredges up all the tensions of post-war America in its content, the monstrous detritus that we would rather not face. Here’s a quote from Evan Calder Williams’ 2011 book Combined and Uneven Apocalypse released as the post-Great Recession era of “zombie capitalism” had taken hold:

Think here of the beginning of Night of the Living Dead, where the first zombie we see – the first recognizable zombie of late capitalism – looks like nothing so much as a homeless drifter of sorts, a raggedy man. Tellingly, Barbara and Johnny, her soon-to-be-zombified brother, hardly give him a second glance: at worst, he’ll ask them to spare some change. He is not marked as undead, at least not in the technical sense. Just as unwanted. Therein lies the explosion out of and against the accepted codes of who we recognize and who we don’t: the zombie’s furious attack, which here has nothing to do with trying to eat them, is the feral assertion of the right to be noticed. Even to the end of the encounter, we can practically read on Johnny’s face the bourgeois frustration: funny, it’s not usually this hard to kill the poor…

This gesture also taps into something far more fundamental in popular culture, going back at least to the early years of capitalism itself: what it does to the human body, the human mind, the human spirit.

There’s another book from 2011, exploring very similar themes in global capitalism. It’s called Monsters of the Market, by David McNally. In it, McNally traces how the monstrous and the inhuman has been used to discuss capitalism since its inception. Marx famously compared capitalism to a vampire, an undead and deadening force that sucks the life from everything it touches.

For sure, every culture has its version of the undead ghoul in its folklore going back centuries. But the first instance of these tropes cast a distinctly modern vein is found in what many consider the first proper modern horror novel: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Shelley was of course a radical herself, an early campaigner for women’s liberation and workers’ rights. McNally also points out that Shelley grew up next to Newgate Prison in London, where public executions took place on a daily basis. These were not just executions of murderers or traitors, but thieves, vagrants, the dispossessed.

Let’s not forget that the early years of capitalism — and this is a process that took place over centuries — involved kicking huge numbers of peasants off their land, confiscating it for private use, and forcing them into the towns where all they had to sell was their labor. Not to idealize life under feudalism, but whereas most agricultural peasants were able to have almost a third of the year with no work. To become a worker under the wage system meant almost constant toil, often repetitive, with very little time off at all.

Those who weren’t able to find that work were often cast off, criminalized, brutalized, and often executed. Witnessing this clearly stuck with Shelley. After the condemned were executed, their remains were most often handed off to the anatomists, who would then sell the bodies to medical schools. It’s no coincidence, therefore, that Victor Frankenstein, the doctor whose hubris condemns both his monster and himself to misery, is shown grave robbing, searching for human parts in complete indifference to who the dead might have been.

Taking into account what capitalism does to the human being as a whole, it can’t be a surprise that tropes of undead flesh, forced to live against all desire to rest, animated by an insatiable hunger that seems to come from without, are so enduring. It would be overly-simplistic to sum up the Romero zombie in Night of the Living Dead as a one-to-one analogy. His zombies aren’t representative of the working-class or the oppressed or disenfranchised. What they are is a personification of capitalism’s death drive, given more immediacy by the time in which the particular work of art being created.

Romero himself told the story about the night in April of 1968 that they finished filming Night of the Living Dead, just outside Pittsburgh. They placed the dailies in the trunk of his car, started it, turned on the radio. The first thing they heard was the breaking news that Martin Luther King had been shot dead.

Immediately, Romero and everyone else knew that this film was going to hit differently. Its protagonist, Ben, is played by Duane Jones, an African American. Romero always claimed that he didn’t cast Jones because he was black, just that he gave the best audition. Nonetheless, the tensions of the film take on a very specific dimension in the context of the civil rights and Black Power movements. The last sequence we see in Night of the Living Dead is Ben shot by a sheriff’s posse, whose members then act like nothing particularly out of the ordinary has happened. It’s this attempt to externalize, to turn the violence of American society into an “other” — when in fact it is, in the words of H. Rap Brown, “American as cherry pie” — that is so pernicious. The movements that had come about to transform this society into a more just and equitable version of itself made that violence a very live question.

Telescope that forward by ten years, almost exactly. American capitalism is still figuring out how to stabilize itself after a defeat in Vietnam, economic shock and oil crises. It’s done so by starting to roll back the gains of the 1960s as well as shredding away at the social safety net. You start to see, even in the early years of the Carter administration, the beginnings of neoliberalism, the replacement of the social with the individual, inherent social rights with the ability to purchase. In short, capitalism was rebalancing itself by privatizing daily life, by hoarding social spending and hitting the accelerator on consumerism to substitute.

But the violence is still there, it’s unavoidable. You will note one of the first scenes in Dawn of the Dead shows a SWAT team raiding a Black and Puerto Rican apartment complex that’s become infested with zombies. It’s a brutal scene, and deliberately frames the more famous images from this film: zombies mindlessly wandering the aisles of a shopping mall. These shots are quite funny, but they’re meant to play on the more cynical, rueful, dark-spirited side of our humor.

We can’t separate the braindead consumerism from the violence and repression. In fact, each makes the other possible. When Peter suggests that the undead are returning to the mall because it’s an instinct, it tells us that the same deadening, soul-sucking forces that dominate our lives in work – accumulation, mind-numbing routine – are extending into our leisure time and into our lives in general.

Today, the mall itself is a dead space, an echo of a past form of social life that revolved around consumerism. But the forces that spurred it on are, if anything, stronger than ever. We live in this peculiar and very pronounced era where we are presented with a greater abundance than ever before, but where the challenges to access it are increasingly acute. The way our lives are weighted down creates its own kind of torpor and inertia that makes it difficult to shake off. One of the takeaways of a film like Dawn of the Dead is that confronting this doesn’t just mean seeing capitalism as an economic system but a social and cultural one that poisons our very sense of the possible.

It is certainly easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, to imagine ourselves tearing each other apart rather than living cooperatively and democratically. The point, however, is that it doesn’t have to be so difficult. There is no more urgent task for the left today than forging this alternative imagination.

Header image is from George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978).

To Whom It May Concern... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Worms of the Senses(what I’m seeing, hearing, and reading…)

Seeing

Weapons, written and directed by Zach Cregger (2025)

Dawn of the Dead, written and directed by George A. Romero (1978)

The Tin Drum, directed by Volker Schlöndorff, screenplay by Schlöndorff, Jean-Claude Carrière, and Franz Seitz (1979)

Hearing

Massive Attack, Heligoland (2010)

The Pop Group, Honeymoon on Mars (2016)

Slowdive, Slowdive (2017)

Reading

Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune, by Kristin Ross (2016)

An Essay On Liberation, Herbert Marcuse (1969)

Pedro Páramo, Juan Rulfo (1959)

October 9, 2025

Forces of Nature

Quickly, before we get into the real horror, two upcoming events…

I’ll be doing a brief introduction for a screening of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, presented by DSA-LA’s Hollywood Labor Committee. It’s at 7pm PST on October 29 at Whammy! Analog Media in Silverlake. Find more info here.

I’m also presenting a paper titled “From Modern Materialism to Popular Modernism: (Re-)constructing a communist methodology of aesthetics” at Historical Materialism London, on November 6, 7pm GMT. More info about the conference here.

California Governor Gavin Newsom thinks that the arrest of Jonathan Rinderknecht will bring “closure” to those who lost their homes or were otherwise affected by the Los Angeles fires ten months ago. Maybe there will be for some, but I doubt it. Not when thousands are still mired in the financial quicksand of rebuilding, fighting with insurance companies who either stopped coverage or simply won’t pay up. Not when the hills of the Palisades and Altadena are still pockmarked with ruins.

Rinderknecht is an easy scapegoat, a way to personalize the disaster and grief, someone to easily blame, a convenient conduit for grief and rage. Evidence released – namely data from his phone – puts him where the Palisades Fire started… a full week before the blaze began. There, he looks to have started the Lachman Fire, a small, relatively insignificant fire that was quickly put out by LA firefighters. Or so it seemed. Embers smoldered there for a week in an underground root system. All it needed was a strong Santa Ana wind to pick it up. Which it did.

I have a long essay on the fires and their fallout in the upcoming issue of Salvage. Here’s a bit of what I’ve written there:

In ‘The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,’ [Mike] Davis writes of the ‘non-linear’ nature of the region’s fire risks. The Big One was never going to have only one cause, particularly as climate change throws predictable weather patterns out of whack. Several wetter-than-normal winters have allowed scrub brush and other undergrowth to flourish in recent years. Combine this with summers that get hotter and drier every year, and an unseasonably dry opening to the 2024-25 winter, and you’ve got ample fuel for something unprecedented.

Now add in the windstorms. The Santa Anas are an autumnal occurrence normally. High atmospheric pressures build up in the Great Basin of Utah and Nevada, then sweep down to the low-pressure coast. Having the Santa Anas show up in the first week of 2025 is further testament to the consequences of climate imbalance. Drastically different atmospheric pressures collide, and the gusts are pushed through the wind silos of the Santa Monica mountains. Trees and power lines are brought down. Sparks fly further and quicker.

No, Malibu and Pacific Palisades should probably never have existed, at least as densely as they do now. It is a steep price to pay for a nice view. But extreme conditions take their toll well beyond the usual fire zones. Altadena, a multiracial town on the eastern edge of LA, one of the few places in California where African Americans could own a home during the height of redlining, was devastated by the Eaton Fire. By some estimates, half of all Black homes burned down.

Climate breakdown, uneven and unequal urban development; these are all far greater problems. Obviously, they will not be addressed by simply putting Rinderknecht behind bars. Which isn’t to dismiss the role he apparently played. Who knows what will emerge in the coming weeks and months, and one should always take any media coverage (mainstream or otherwise) with a grain of salt nowadays. But the impression one gets of him so far is of someone quite troubled, though no more or less troubled than most people.

Prosecutors and investigators have said Rinderknecht was driving for Uber in the Palisades when he set the fire on New Year’s Eve. The passengers described him as “agitated,” though anyone who has had to work on New Year’s, particularly driving around drunk rich kids, can probably explain that agitation. The building manager at his apartment said he might have also worked as a restaurant server in Hollywood.

Neighbors and acquaintances describe him as two different people: on one end very normal, on the other someone volatile and disaffected. He was probably both. Nothing is more normal in this era than being disaffected, generally unmoored, isolated, without direction or support. Naturally, plenty of people manage to eke through the social disintegration without setting catastrophic fires.

There’s also, however, reason to believe he never anticipated it growing into the raging inferno that decimated the Palisades. Should he have? Nobody anticipated the Santa Anas to pick up the way they did, though at the same time the fire zone signs in Los Angeles are up year-round for a reason. It’s entirely possible this is a person with a level of dissociation that has left his sense of consequence completely distorted. If so, then we can only return to questions of what shaped him into this.

If the future is lucky enough to have archeologists of some kind, then they will be a jarring combination of spoiled and frustrated. Should the records of the algorithm survive in some legible way, they’ll be able to map our cultures to an unprecedented level of detail. The twists and turns of those maps, however, will be baffling, possibly to the point of indecipherability. Exploring the endless reams of queries, fantasies and scenarios stored in the memories of ChatGPT one of them may come across this prompt, and the images it generated:

“In the middle [of the painting], hundreds of thousands of people in poverty are trying to get past a gigantic gate with a big dollar sign on it.

“On the other side of the gate and the entire wall is a conglomerate of the richest people.

“They are chilling, watching the world burn down, and watching the people struggle. They are laughing, enjoying themselves, and dancing.”

It will likely be difficult for any archeologist to tell if these words are an accurate depiction of the world that produced the LA fires, or the digital ravings of someone deeply unwell. They are, in fact, both.

Header is images prompted by Jonathan Rinderknecht on ChatGPT, sourced through the BBC. I do not condone using AI to generate “original” images.

To Whom It May Concern... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

September 11, 2025

Violent Meaning, and/or, Meaning Violence

“With the new conditions that now predominate in the society crushed under the iron heel of the spectacle, one knows, for example, that a political assassination finds itself placed in another light; can in a sense be sifted. Everywhere the mad are more numerous than before, but what is infinitely more convenient is that they can be talked about madly. And it is not some kind of reign of terror that imposes such mediatic explanations. On the contrary, it is the peaceful existence of such explanations which should cause terror.” – Guy Debord, Comments On the Society of the Spectacle, 1988

When nothing means anything, anything becomes possible. That’s certainly the mad method at play here, and has been for a long time. It can’t be any other way in a falling empire.

Charlie Kirk was an influencer. Yes, he was an influencer whose persona existed entirely in the realm of politics, and he managed to assemble a large, even powerful network of conservatives on college campuses, but that did not make him a politician. That someone who does what an influencer does – posting online, speaking at functions, but mostly posting online – can be legitimately accepted in the realm of politics speaks to how much the boundaries between have dissolved.

The tidbits of decontextualized information, the fragments of definition that can bounce so freely around the internet; these were Kirk’s bread and butter, an atomic unit for online outrage. Which generates more online outrage, which generates more online outrage still. Build it up enough and those at the center of it will be launched into the public eye. But the momentum that puts them there – the “clout” – is ultimately without substance. That substance is filled with meaning only after the fact, when the vague and nebulous gains enough speed to produce the event.

That’s what is happening now. Even the fact that Kirk’s shooting death is being called an assassination, let alone that liberals are scrambling to paint this vicious yammering charlatan as an honorable political actor, speaks to how deeply our basic sense of meaning is being remade right now.

Flags now fly at half mast, for someone who has been able to do a measurable amount of damage to the lives of others. Meanwhile, Trump blames “the radical left” for Kirk’s killing, despite no suspect being arrested and no motive being known. He blames this same left for the attempt on his own life last summer, though Thomas Crooks had no known connections to any leftist organization and was, according to some sources, a registered Republican. This, again, does not matter.

None of those shot at school or at work or in any number of various public spaces get this level of reverence. None command such strident vows for revenge. None of their supporters invoke blood for blood like Kirk’s are now. And yet it is Kirk’s supporters, and the right writ large, who are the real victims, armed to the teeth and yet somehow powerless.

Make no mistake, out of this event, they are assembling new meanings, definitions and redefinitions reshaping the world. The far-right has understood hegemony better than liberals or the center for a long time now. Intrinsically, it grasps that assembling the social forces necessary for shaping a new reality requires this kind of redefinition. They’re good at it. And they’re getting better. Their core meaning is violence, and they mean to do violence.

What is there to do then? It is difficult to tell how exactly Trump and his base intend to follow through on their threats against the left, but some sort of physical defense is almost certainly going to have to be in the cards for our side. Coordination between the armed wing of the state and the armed far-right is being strengthened right now. Without giving into panic, with clear-eyed, cool-headed urgency, we need to understand and accept that we are not safe right now. All the coded false promises being dangled by liberals right now – learn to be civil and they won’t come after you – mean nothing on a long enough timeline.

Past that, there is a pressing need to understand exactly how we’ve been outflanked, how it is that we’ve gotten to the point where Trump and the right are able to so readily exploit the event like this. I’m sympathetic to what Julia Alekseyeva calls “radical media literacy,” mentioned in her book Antifascism and the Avant-Garde. In a world so wholly mediated, understanding how aesthetics and the struggle over interpretation have a real material impact on our sense of possibility – and the willingness to act on that possibility – is essential.

The opposite is also true: in a world so wholly mediated and aestheticized, media literacy on its own comes a day late and a buck short. In Disaster Nationalism, Richard Seymour dismisses the concept entirely. Though he may be oversimplifying the argument, he also rightly argues that the right knows how to mobilize passionate despair in an incredibly effective way. If we cannot counter this, on this level, then we are well and truly fucked.

What Jacques Lacan calls the chain of signification or signifying chain comes into play here. How does one word or phrase trigger another? How do these link together in such a way that the subject is moved to action? What alternative frameworks of meaning and mental association can be constructed through the actual associations of solidarity? How can this sentiment be understood, not just on an intellectual level, but on a deep psychological and practical level? How can this worldview be reinforced psychologically, and how can the psychological map make itself real?

If this sounds like a shade of the utopian, then you’re catching on quick. It’s not a liability right now. In fact, if we grasp it rigorously and sensitively enough, it may be our best asset. We could have, and should have, learned this a long time ago. Now we’ll simply have to learn as we go. Either we figure out how to build something new, or something old and spiteful, something that refuses to die, overtakes us entirely.

Header image is Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for a Crucifixion (1944).

To Whom It May Concern... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Worms of the SensesSeeing

Trainspotting, directed by Danny Boyle. screenplay by John Hodge (1996)

Every Cook Can Govern: The Life, Impact, and Work of CLR James, directed and written by Ceri Dingle and Rob Harris (2016)

David Lynch: The Art Life, directed and written by John Nguyen, Olivia Neergaard-Holm, and Rick Barnes (2016)

Hearing

Stars of the Lid, The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid (2001)

Manic Street Preachers, The Holy Bible (1994)

MF Doom, Mm..Food (2004)

Reading

Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, by Guy Debord (1988)

Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, by David Harvey (2019)

Collected Poems, by EP Thompson (2020)

September 3, 2025

What Swarms

The story will go like this. Eventually, life in the cities becomes untenable. Chains of value and exchange between town and country – built up over centuries – will break down. Not everyone can flee. Those who can will head for the countryside. Far more habitable.

As the hum of civilization recedes, the wreckage comes into focus. The centuries-long hollowing out of the countryside becomes unavoidable. Industry, as we understand it, starts in the small gap between urban and rural, widens it to a chasm. It digs into the earth, scrapes it out, and builds on top of the dirty, cavernous nothing it leaves behind.

The first elevators, the first technology that lifted us safely upward into buildings, weren’t used in skyscrapers. They were used in the mines, sending men and boys, hundreds at a time, deep down into the earth to haul buckets of minerals back up with them. Tons of rock and earth that should have stayed there, burned and spewed into the air.

That’s where the new/early/modern towns were built, on top of winding, maze-like caverns leading miles down into the crust. When there was nothing left to dig up, that’s where they were left. Many of them anyway. And many of them will be where people return to as they flee the faltering cities, once woven into their own intricate networks of place and people, now slowly

Consider the abandoned mining settlements of Northern Appalachia. Sewell, West Virginia, where the coke ovens and the houses still stand, but neither have been used or lived in for decades. Kings Station, Ohio, where coal production stopped in 1910, but the sturdy industrial structures can still provide ample shelter. Even the few remaining homes on top of the subterranean hellfire of Centralia, Pennsylvania might be a suitable place to wait out the world’s slow unravelling.

Or think of the small towns of Yorkshire and North East England. The towns already half empty from the closure of the mines. The places “redevelopment” skipped over in the wake of deindustrialization, punctuating the rolling moors and dales. Seaside villages that have tumbled into the North Sea as the clay soil eroded.

It’s not much, and many of the homes will be little more than ruins. Some have remained standing, even if they are in various states of disrepair. In terms of basic shelter – from the elements, from the collapse of a top-heavy civilization – they’ll do. Those who grew up with the irrepressible urge to escape, to run to the big cities and never return, will now find themselves running back to the suffocating quietude of brick row houses and the aimless indolence of a never-ending Sunday.

Describing these people will be difficult, like trying to summarize bits of paper thrown into a gust of wind. Beyond statistical grouping or sociological trends. In any event, there won’t be much of a statistics or sociology to sum them up. Just a vast trickling something that is.

Most of them won’t be looking to “start over,” still less to rebuild. More to find a place where they can forget. Where they won’t be burdened with the memory of lives that buckled under the weight. And, just as important, where a dying world can forget them. A chance to wait out the end in something like dignity.

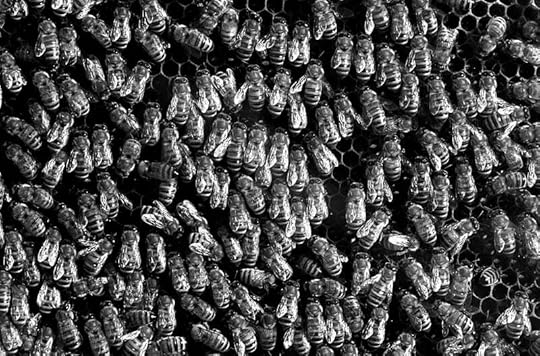

Bees hold the blueprint of a society. Not our society, but certainly a society. Its shape has been embedded in their genetic instinct over the eons of evolution. The hexagonal cells, stacked on top of each other: wax molded into a precise pattern millions of times over for a single hive. It’s all designed to an exact specification, providing for the various roles necessary to maintain it. A place for honey and pollen storage, for safe passage of foragers and drones, for the queen to lay her eggs. A hive of bees even knows how to keep the exact temperature needed for it to thrive.

Then the work that goes into maintaining that hive and its place in a vast and intricate ecology. Honey isn’t just a byproduct adopted as a condiment by humans. It is a vital, high-energy food source, perfectly fit to the bee’s metabolism. It is a misconception that bees fly from the hive to collect pollen. They fly out to collect nectar, naturally produced by flowers; the pollen that gathers on bees’ legs and bodies, deposited from flower to flower, is another crucial incidental of botanical evolution. It is the nectar that’s turned into honey, stored in the bees’ stomach, brought back to the hive, regurgitated and dissolved in enzymes, then fanned by the bees’ wings to evaporate excess moisture. Thus it’s transformed into the familiar sticky substance.

Think of all this. Actually think about it and sit with it. How perfect was the sequence of events in the natural selection that such a precise, delicate, wondrously intricate balance could be struck? Between plant and animal, yes, but even internal to the animal. And, significantly, designed and constructed by the animal. In considering this, are we considering all the uncanny valences? What are we watching when we do? Is it merely another series of webs and networks, connected

Bees cooperate instinctively. They need to if they’re to maintain their highly complex social structure. Bees also dream, at least according to some researchers, replaying memories when they sleep. This means consciousness, of a sort. Some research suggests they suffer a form of PTSD, and that the spreading catastrophe of colony collapse isn’t merely due to pesticides and pollution, but from the psychological stresses experienced by the bees themselves as industrialized agriculture continues to march along.

It’s the dismal upshot of the Anthropocene. When the bees are dying, as they are right now, it’s more than society that’s in trouble, whatever that means. It’s the very ontology of building, a collapse of the organic infrastructure necessary for a large swathe of complex collective life to survive.

In other words, we will not be the only species that leaves behind what had been an infrastructure, the networks of rooms and tunnels, the scaffolding of interwoven lives, sitting silent and still. Remnants of a dead world with only itself left to experience it.

Header image is public domain, from the US Department of Agriculture.

To Whom It May Concern... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Worms of the SensesSeeing

The Big Lebowski, directed by Joel Coen, screenplay by Joel and Ethan Coen (1998)

Hangmen Also Die! directed by Fritz Lang, screenplay by Lang, John Wexley, and Bertolt Brecht (1943)

News from Home, written and directed by Chantal Akerman (1976)

Adolescence, directed by Philip Barantini, screenplay by Stephen Graham and Jack Thorne (2025)

Hearing

Loscil, Plume (2006)

Calexico, Algiers (2012)

Múm, Finally We Are No One (2002)

Reading

Psychogeography, by Merlin Coverley (2006)

Nineteen Seventy-Seven, by David Peace (2009)

A History of Pan-African Revolt, by CLR James (1969)

Gaza Faces History, Enzo Traverso (2024)

August 18, 2025

Old Pop, Good Pop

To Whom It May Concern… relies on your support. If you haven’t become a paid subscriber yet, then now is your chance.

1.Is More good? Is Pulp’s first album in 24 years, released earlier this summer, good? It’s a surprisingly difficult question to answer. And to be clear, good does not necessarily mean worth listening to. We know the album is worth listening to because millions of fans listened to it after its release. Most of them probably listened to it more than once.

Similarly, we don’t just mean enjoyable when we say good. More is obviously enjoyable. That Pulp are currently able to fill fairly large venues while touring in support of the album makes this clear enough.

Then again, plenty of demonstrably bad acts produce songs listened to repeatedly, and manage to sell out even larger spaces than the Hollywood Bowl or Detroit’s Masonic Temple. Some of the most well-known artists in the world are demonstrably bad. Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker seems to have always been aware of this on some level: whether an artist’s music is good has little to do with whether it’s an obvious spectacle. Such spectacular bands may also be good, but their being good has little to do with the fact that they can produce a spectacle. When Cocker infamously shakes his ass at your performance, you can at least take comfort in the fact that he isn’t necessarily calling you bad.

The lines, the definitions, are blurry. Cocker and Pulp don’t seem to particularly care though. The lead single from More seemed to straight up revel in the idea of being bad, inept, out of step.

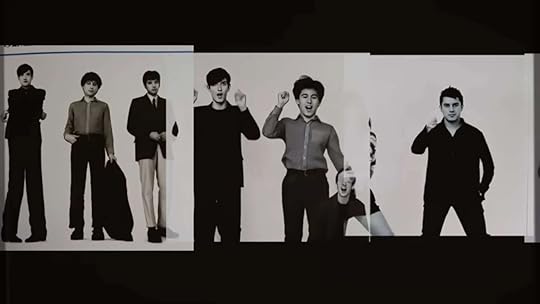

The video for Pulp’s “Spike Island” announces itself bluntly. “This is the new single by Pulp,” reads the chyron in big, pink, block letters. “It’s called ‘Spike Island.’” As we learn, the video is made entirely from thirty-year-old photos of the band and their albums, fed through an artificial intelligence application.

The animation is bad. Hilariously and intentionally so. Over the song’s shimmering keys and soaring guitars, we watch as still images of Pulp are crudely dropped into row-houses and chip shops, moving in wooden, unrealistic ways. “Perhaps I need to work on my prompts” say the pink letters. Before long, the scenes around the wooden, inert band members devolve into the same incongruous slop we are used to seeing from AI. Bicycles and coaches move sideways. Bodies mutate extra limbs.

“Spike Island” is the lead single from More. Being out of step isn’t just inevitable here; it’s probably on purpose. “Maybe,” reads the chyron, “we need to work on other ways of coming alive.”

2.“You will never understand / how it feels to live your life / with no meaning or control / and with nowhere left to go.” It’s been almost 30 years since Cocker famously spat these words in the face of a class tourist in “Common People.” While its premise is familiar enough today, the archetype of the “class tourist” stung in a different way in the “end of history” 1990s.

Most of Britpop at the time, compulsorily laddish as it was, often pointedly disdained the idea that pop music could actually do something. This was of course in perfect line with the proto-Blairite Cool Britannia optimism that attempted to shed pesky concepts like class or inequality.

Ten years before “Common People” was recorded, some of Pulp’s members had been on picket lines supporting the miners striking against Thatcher. Russell Senior, the band’s then-guitarist, volunteered as a flying picket, blocking scabs from entering the mines. The miners’ crushing defeat stuck in the minds of many of the era’s bands. Manic Street Preachers. The Mekons. Pulp.

Listen to “Last Day of the Miners’ Strike,” the one new track included on the band’s 2002 Hits compilation, and you can hear it. Horizons for young working-class people in their native Sheffield shrank. Thinking about politics became a fool’s pursuit, and by “‘87 socialism gave way to socialising.” The contrast between hope and defeat became a kind of “Magna Carta,” a nostalgic touchstone wistfully longed for rather than actively remade.

Now, a few decades later, the future of neoliberalism is in question. What looks set to take its place, though, is an amplification of its most venal, coercive aspects. Cruelty becomes a virtue. All things bearing a sympathetic human touch are regarded with spite and suspicion. After enough time having the synthetic and simulated shoved in our faces, one starts to think they’re natural. That they’re good.

3.

3.Ways of coming alive. It’s an odd turn of phrase. Life, at least in how we are taught of it, just is. Its biology manifests of its own accord. Finding a way to come alive seems to push where there’s already momentum. Unless, of course, something in that biological process is out of step…

Ways of coming alive. It bears a certain resemblance to one of the most influential books on art of the late 20th century: John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. Whether this is deliberate or not, we do know that Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker is a fan of Berger’s book. He has publicly cited it as an influence on his memoir Good Pop, Bad Pop. (The list also includes Damon Krukowski’s Ways of Hearing, which creatively applies Berger’s framework to music.)

August 1, 2025

It Will Begin Again

It may be the most inconsequential example of collective enlightenment in recorded memory. Over the past few weeks, the political establishment and mainstream media seem to have grown a heart for Gaza, or at least for Gazans. More liberals, including in Israel, are acknowledging the unfolding mass starvation – wholly engineered by the Israeli state – as an act of genocide. France and the United Kingdom are willing to recognize a Palestinian state. The world watches, the world declares its horror.

And what changes? Next to nothing. The west’s most powerful governments – including those now waxing diplomatic – are still in practice supporting Israel, still sending it arms, still pleading ignorance when members of its government openly declare their intent to cleanse the whole of Gaza. If most of the world acknowledges mass murder, and that mass murder is allowed to continue, can we credibly speak of democracy?

It goes to prove, yet again, what many of us have progressively realized over the past decade, what history shows us time and time again. Horror is not enough. Shame is not enough. Morality is not enough. Protest? Only if it manages to fully stop the everyday in its tracks.

Grief is also not enough. In fact, as PE Moskowitz argues, the urge to grieve while the crime is ongoing may reinforce a certain resignation, powerlessness in the face of calamity, not just now but in the future too. “How can one grieve those who are not even yet known dead?” they write. “One can only do so if those people have already been killed in our heads.”

The viabilities of life and respect for it are deliberately made slippery here. Those who are already dead were never fully alive. Those who we grieve now, quickly, have their memory defanged.

But then, this is how the (post-)(post?)modern empire stunts our psyches. Any sympathy for the colonized has also had to break through twenty-five years of War on Terror monstering, decades of Orientalist racism, and a few centuries of imperial mistrust. At the end of history, it is these divisions that are somehow real, while empathy, love, and solidarity are shifty and untrustworthy.

Mass atrocities, some insist, are essentially unknowable, beyond comprehension. Others have argued that making them exceptional also makes them repeatable. We’ve been proven right. And as a result we are now faced with what feels incomprehensible.

Not that we cannot grasp who made it happen. Famines, as Brecht reminds us, never simply happen. They are perpetrated. But how they can be conceived in the first place, how one set of humans can even countenance carrying this out against another; this is what avoids comprehension. It is the self-fulfilling prophecy of the amnesiac, and it has a sick sense of humor.

War and its aftermaths were a major preoccupation in the work of Alain Resnais. Form-wise, he returned again and again to the fractured narrative, the shards of events that can never be wholly reassembled. In other words, he fit right in among the French New Wave: Jean-Luc Godard, Anges Varda, Chris Marker, Marguerite Duras. Resnais worked with all of them at one time or another, and shared with them a certain sensibility that the everyday could be a prison.

His first full-length feature film, 1959’s Hiroshima, Mon Amour, was written by Duras. Two lovers, a French woman and a Japanese man, return to each other in Hiroshima. He is an architect, while she is in town to shoot a film on the subject of peace.

The two have much to hide from each other, and anyway both of them are happily married, though they occasionally indulge in extramarital affairs. She never wants to return to her home, the French city of Nevers. He can only return to a Hiroshima that has been rebuilt on the ruins of a city where his whole family died in the bombing. She, meanwhile, wishes she could forget that she fell in love with a German soldier during the war, and that after her neighbors found out they killed him and tortured her, driving her to madness. (That her lover may have been a supporter of the Nazis is never mentioned, nor is it really the film’s point.)

Life continues, much as they hate the idea. And it continues in such a way that the two cannot fully connect. Every embrace is ash. For twenty straight minutes in the film, they silently wander the streets of Hiroshima together, him following ten feet behind her, she never turning to see him. Only at the film’s end do they admit to themselves that their traumas, their grief, and their desires will have to breathe the same air.

“It will begin again,” she says to him. “200,000 dead and 80,000 wounded in nine seconds. Those are the official figures. It will begin again. It will be 10,000 degrees on the earth. Ten thousand suns, people will say. The asphalt will burn. Chaos will prevail. An entire city will be lifted off the ground, and fall back to earth in ashes…I meet you. I remember you. Who are you? You’re destroying me. You’re good for me.”

What is Hiroshima, Mon Amour about? Artists, scholars, and film aficionados have discussed it for sixty-five years. Is it about love? War? The contrast between the two? The ability of east and west to face each other as equals? Human commonality beyond borders?

Yes and no. All of the above. None of it. More than anything, it is an attempt to grapple with history’s apparent impossibilities. Just as it is impossible to square the loss of her lover with the loss of 140,000 people in the wake of the bombing. Just as it is impossible to square the message of a film with mass starvation in Palestine.

This isn’t to say everything is inevitable. Just that the most intimately human can be as confusing and as overwhelming as the grandest historical event. In some ways, the latter is impossible without the former. Maybe, when we actually grasp the full truth of this, we won’t have another Hiroshima or Gaza to fear.

Header photo is a still from Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959).

To Whom It May Concern... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Worms of the Senses

Seeing:

Intruder in the Dust, directed by Clarence Brown, screenplay by Ben Maddow (1949)

La Jetée, written and directed by Chris Marker (1962)

Herbert’s Hippopotamus, written and directed by Paul Alexander Juutilainen (1996)

Odds Against Tomorrow, directed by Robert Wise, screenplay by Abraham Polonsky (1959)

Hearing:

Black Moth Super Rainbow, Soft New Dream Magic (2025)

The New Eves, The New Eve is Rising (2025)

RJD2, Deadringer (2002)

Black Sabbath, Paranoid (of course, 1970)

Wet Leg, Moisturizer (2025)

Reading:

Gothic Capitalism: Art Evicted From Heaven and Earth, by Adam Turl (2025)

Anti-Fascism and the Avant-Garde, by Julia Alekseyeva (2025)

Ways of Hearing, by Damon Krukowski (2019)

How To Be a Revolutionary, by C.A. David (2022)

July 18, 2025

New Maps

The confetti has fallen. The celebration hangovers have faded. Now the problems and realities of power come into focus, the excitement for a new future faces the inertia of history. It is not a sure thing that Zohran Mamdani will be the next mayor of New York City, but it is more likely than the other options.

Eric Adams is simply too bogged down with scandal and corruption; the political establishment has abandoned him. Andrew Cuomo’s shames follow him around like a cursed shadow. His recently-confirmed independent campaign will be shambolic at best. Real estate moguls and the like will do what they can to prevent Mamdani’s election. The momentum is against them.

We should not for a second dismiss the significance of “Zohran Mamdani, Mayor of New York City.” The largest city in the United States – a global economic hub, a collision point for hundreds of languages, backgrounds, and cultures – governed by a democratic socialist, and a young Muslim to boot.

In the context of Donald Trump’s America, this will be a significant shift in the political calculus. The administration is, predictably, already putting him in its sights. If and when he wins in November, this will intensify. The possibilities will grow. So will the pitfalls.

The global imagination holds a very particular place for New York. In many ways (for better or worse, fairly or unfairly), it has come to be regarded as not just the archetypal American city, but the platonic ideal of the city. As such, whatever contradictions New York stumbles over tend to be encountered by others. The philosophies of small chaos Jane Jacobs lauded to counter the authoritarian influence of Robert Moses in the 1950s are twisted back around into justifications for displacement. Walkable neighborhoods, quiet streets, and the small business as artisanal endeavor become synonymous with gentrification. When Broken Windows policing became the go-to for American cities, it was only after Giuliani had workshopped it in the poorer neighborhoods of New York.

In keeping with this, today’s New York bears the marks of late-late capitalism in spades. To walk through Harlem, Astoria, Flatbush, or the South Bronx is to see vibrant, multiracial, working-class communities sliced through by aloof, homogenizing affluence. Expensive condos bear down on bodegas. Apartment buildings are filled with families whose faces are used to attract middle-class liberals to the area, who will in turn come to resent the very presence of the humbler, more long-time residents.

We are, inevitably, obligated to imagine a New York where these residents – nurses, transit workers, teachers, retail employees, street vendors, hustlers, homemakers – are front and center. Not just in terms of visibility, but in terms of the decisions that shape daily life in one of the world’s central cities. A Mamdani victory does not, to be clear, signal the start of the New York Commune, but it does demand we ask questions about the socialist city. At stake in this moment isn’t just the political fortunes of Zohran Mamdani, the future of the left or New York City, but the ability of a socialist project to provide a concrete, radically democratic vision for American cities.

Nobody is by now surprised that this prospect is making the Democratic establishment anxious. It is sadly predictable that the likes of Bill Ackman are pouring barges of cash into sinking Mamdani’s campaign. Almost as predictable as Bret Stephens’ New York Times op-ed “Mamdani for Mayor (if You Want to Help the Republicans).” There’s not much to say about this one – if only because its talking points are so tired by now – but it is worth pointing out how much of it comes off like a threat: the worn tropes of a crime-ridden, unlivable city wielded to whip votes for the same people currently making it unlivable. “Turns out, socialism works no better in Brooklyn than it does in Havana,” writes Stephens. This, dear readers, is a man salivating for a trade embargo on Bed-Stuy.

Far more useful is the amount of Mamdani supporters now interrogating challenges and obstacles of socialist governance, examining the strengths and viabilities of his platform, trying to pick out the places where it might get into trouble. There is an encouraging tone of yes, and… in most of this analysis, seemingly signaling that what this particular democratic socialist says about a future New York is far from the last word.

Brian Callaci’s and Osman Keshawarz’s Jacobin piece is spot-on in pointing out that rent freezes – a key component in Mamdani’s platform – are an effective way to keep people in their homes, but only if they are made one part of a larger vision of social and public housing that undermines private developers.

Ross Barkan (whose 2018 campaign for New York State Senate was managed by Mamdani) is also attempting to think ahead in last week’s Times op-ed. It’s a useful piece, though frustrating at times. Not because of what it says necessarily, but what it doesn’t.

It is old Marxist hat to say that this frustration stems from Barkan’s pragmatism. But there are two kinds of pragmatism. One is the kind that disingenuously throws up its hands and asks what can I do? while in fact not even trying. The other, if borne of any sincerity, is an impatient, uncomfortable sort of pragmatism. The kind that sees every stopping point as one in a series of strategic battles of position, a springboard toward bolder and more radical initiatives.

July 8, 2025

That's Not Me

The following was delivered, via Zoom, for the launch of Adam Turl’s book Gothic Capitalism: Evicted from Heaven and Earth, as part of Le Grande Transition conference in Montreal on May 27, 2025.

I will also be delivering a paper at the Historical Materialism conference, to be held London from November 6 - 9. The title of paper is “From Modern Materialism to Popular Modernism: (Re-)constructing a communist methodology of aesthetics. More details forthcoming.

On December 2nd, 2016, during a performance of several electronic and house music artists, the Ghost Ship performance space in Oakland, California caught fire. The Ghost Ship was a warehouse surreptitiously converted into an artist collective.

The building was not built as a performance space. It had neither sprinklers nor sufficient fire extinguishers. The fire spread quickly. Thirty-six attendees, including artists and musicians, died. Blame immediately fell on the artists themselves. After all, legally, they weren’t supposed to be there. But with gentrification and the disappearance of cheap rents making independent performance spaces and even existence as an artist impossible, where else were they to go?

Promises were made to investigate, and indeed, the primary renters of the space went to trial, a few went to jail. But rents for workers and artists, in Oakland and elsewhere, remain increasingly unaffordable. Beyond Oakland, police used the tragedy as a pretext to evict other alternative art spaces.

As if this weren’t enough, the Ghost Ship tragedy also found its way into the sights of the American far-right. Still high from the first election of Donald Trump just a few weeks before, and seeing any deviation from an arbitrary norm of Americanness as another manifestation the queer, woke threat, right-wing message boards lit up with gleeful socialized sadism. Users encouraging each other to search out underground venues like the Ghost Ship, report them to local police, even take matters violently into their own hands.

Seven years later, October 7th, 2023. As part of the incursion across the Gazan border into Israel 378 attendees at the Nova trance music festival at Kibbutz Re’im, were killed by Hamas militiamen. The events themselves, and the countless horrific stories, were broadcast around the world, and used as pretext for the full-scale assault on Gaza by Netanyahu’s Israel. As we know, this assault, this genocide, is ongoing.

How can they attack a music festival? observers asked. A naive question. For just five kilometers away is Gaza itself, an area that, well before October 7th endured two decades of siege and blockade. Where Israel monitored and repressed everything from Palestinians’ political activities to their daily caloric intake. Where peaceful protesters who approached the border fence were fired on by the IDF.

How can insurgents think of attacking a music festival? We will be unable to answer this unless we first answer how it is that any festival takes place within earshot of the world’s largest concentration camp.

These are two moments are the coordinates of music’s current spatial exile. Marx observed that capitalism annihilated space with time. Fredric Jameson updated and flipped this on its head, arguing that the architectures of late capitalism annihilate time with space. Both are accurate, pulling our built environment and the individual subject in impossible simultaneous directions, the arrhythmia that Henri Lefebvre diagnosed contemporary urban space with.

Music, with its reliance on rhythm, simultaneity, syncopation, also has a specific relationship to time. These temporal and spatial relations have also been privatized and disrupted. Its fields of experience narrowed by the rise of personal listening devices, headphone culture, streaming services and the algorithm. What has, anthropologically speaking, always been a collective experience has been atomized and disconnected.

In light of this, capitalism makes music’s homogenization all but inevitable, fodder for background noise, designed to soothe our anxious, exploited, traumatized psyches: manufactured by AI-generated ghost artists, piled into playlists we neither have nor want control over. The worker musician, liked the worker artist described by Adam Turl in Gothic Capitalism, is increasingly confronted by a spectacularized cultural landscape, that divorces human creativity and human labor from their temporal and historical valences. The shapes and paces of daily life are often beyond the control of even the richest and most powerful, more the product of late capitalism’s anarchic inertia than anything else. The mass human imagination, in both its individual and collective iterations, is exiled from history.

The scene, the geographic and temporal space of difference that made it possible for artists to live, create, collaborate, and flourish, is strangled. The average price for a home in San Francisco’s former hippie hub of Haight-Ashbury is now $2.3 million. CBGB is replaced with a John Varvatos boutique.

As such, the artist is doubly exiled, not just from history but from themselves. By now it is old hat to say that virtually all art in late capitalism is an attempt to confront a deep alienation. But in confronting that personal alienation, artists also frequently confront their ability or inability to create history. Take the video for Skepta’s 2014 track “That’s Not Me,” in which the grime MC asserts an individuality past the glamorous trappings that often surround hip-hop’s various styles. This was about two years before Skepta won the Mercury Prize, and grime finally came to be considered a valid part of the UK’s musical landscape by the music industry, still when the style’s associations with the housing estates of urban Britain made it the target of police raids and radio censorship.

There’s much to say about the song and the video. What bears mentioning in this context is Skepta’s use of headphones as a microphone. This isn’t exactly novel. It’s a common enough practice among musicians with limited resources. It is very fitting however. Turning an instrument of music’s isolation inside out, using it to project the rhythms and experiences of the artist back into a collective milieu.

It is also a synecdoche for the kinds of musical approaches that will be needed as neoliberalism gives way to what is still taking shape in its place. The commodification of life has emptied time into a linearity of mind-numbing sameness. It has turned public space into a threatening reminder that you exist at someone else’s whim.

Given what we know about the likes of Trump, Modi, Orban, Milei, Meloni, as well as Farage, and the various personalities of France’s Rassemblement National, it is not far-fetched to imagine lived time transformed into a telos of absolute despair. Death, jail, or work. Take your pick. Or to imagine pseudo-public space giving way to expanding sacrifice zones and inverted gulags: undesirables locked out rather than in.

There is, without a doubt, a musical counterpart to this. We have already heard and seen it. Just as artificial intelligence takes the human element out of the annihilation of Gaza, so does it raise the possibility of music made without human input. This is already commonplace. We can turn our noses up to the audio equivalent of slop as much as we want, but the more of it that’s created, the more it homogenizes the means and averages of sonic possibility.

Classical music is already piped into train stations and public squares to deter “the wrong kind of people.” Can noise instantly be tailored to chase off over-surveilled youth, based on a data-mined profile, be far away? Maybe. But maybe not. Every eventual watershed dissolves another layer between the present and the most dismal, dystopian version of the future. We are not ready for it. But we can and must envision the kinds of utopian ruptures that have always been a vital lifeblood of the revolutionary prospect.

These have been part of our movement since at least the songs and poems of the Diggers in the English Civil War. But it is only with the advent of modernity – and specifically modernism – that the direction of their gesture started to take shape. While modernism dared to dream of the future, its boldest, most radical iterations took what Walter Benjamin called “a tiger’s leap into the past.” Malevich’s blunt squares and crosses referenced and replaced religious peasant ikons that went back centuries.

The delta blues quoted slave spirituals and West African music in such a way that made them fit inside and apart from the railroad economies that unleashed the form into urbanized areas. It also was, notably, celebrated by the surrealists for what it was: a howl of those deemed invisible and disposable. The “blue note” a note that could not be quantified in the confines of western music annotation, became a common reference for the virtual entirely of popular music.

The reclamation of time inevitably requires the reclamation of space, as the rave scenes in Detroit, New York, Chicago, London, Rotterdam and beyond showed. Old warehouses or factories or disused train yards, abandoned by neoliberalism, were transformed into sites of collectivity. When police and governments came for these spaces, they had to politicize to be protected, often quite quickly.

In a moment that threatens absolute wreckage, this gesture of salvage, of radical reinvention of what capital would rather discard and forget, becomes all the more vital. When anachronism insists on its own existence despite the steamroller of official time, it disrupts that time, opening up the potential for a different trajectory. It reclaims the collective-utopian valences of artistic expression.

More recent radical cultural frameworks have attempted to accentuate this. The thrice-dead “salvagepunk” of China Mieville and Evan Calder Williams centers the principle of reinventing out of the discarded. The assertions of the late Mark Fisher’s “popular modernism” sought to discover the democratic nexus between the popular and the avant-garde.

In this respect, the kinds of musical expressions to come will not be unique. They will simply have to be more forceful, clinging ever more fiercely to what has been left behind, reaching even harder into the future. They will have to embrace what, pivoting from Turl’s “weak strong imagery,” we might call weak-strong sound, cobbling together a collective dream that stands in contrast to the nightmares of disaster nationalism. Particularly as the repressive tolerance of neoliberalism gives way to outright repression.

Musicians and artists that did not behave within the parameters of late capitalism’s cultural logic were until recently very easily ignored out of existence or metabolized into a sanitized version of themselves. Now they have to be boycotted and cancelled, gleefully driven out of the center of cultural consciousness, the full weight of political and cultural respectability brought to bear.

Consider the furor around Kneecap, Irish republican rappers from the working-class areas of West Belfast whose decision to rap in Irish Gaelic could have easily been pigeonholed as a novelty by the music industry. Each tiresome controversy around the group has simply gained them more fans, brought their music to the attention of more young people. Their streams have increased. Their shows have sold out quicker. And a few more people know how to say “fuck the cops” in the Irish language. They know how to game the spectacle

To be clear, this is a gothic, salvage approach too. Listeners identify with Kneecap’s lyrics partly because of its references to grime, IDM, the rave scene, and partly because they portray, vividly, young people displaced from time, anachronized, left to the anarchies of history’s backgrounds. Stories of boredom, scapegoating, harassment from cops, random sex, the anxieties of mental health and poverty. The thrills of petty vandalism and doing handfuls of drugs. In other words Kneecap’s music seems to reach toward a postcapitalist desire, an impulse for a mode of being more enjoyable than the present and cobbled together from its detritus.

Their appearance at Coachella, however, in which they projected messages opposing Israel’s war on Gaza, has been countered with calls to have their work visas revoked, even charges of supporting terrorism against one of the group’s members. We should expect more of these as capitalism’s more illiberal phase takes shape.

We must also understand that at stake is a fundamental question about art in late capitalism. Who gets to make art? What kind of art do they get to make? What purpose will it serve? Will it ferment the human subject apart from the rule of capital? Or will it become a soundtrack to the subject’s confinement?

Where one stands on these questions will likely tell us where they stand on a host of other matters. Key among them: socialism or barbarism.

Header/background image is by Laura Oldfield Ford. All other images were used in presentation slideshow.

To Whom It May Concern... is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

April 29, 2025

Half a Life

For the past several months, our struggle – existential and material, though mostly existential insofar as it is material – has been not to assert our place, but to understand it. How can we fight for a place if can’t grasp its shape and boundaries, if we can’t cobble together a few predicted outcomes to resist or fight for?

It’s not just that we have trouble imagining a future. Lately, we also seem to lack more than a tenuous grasp on the present. These are cruel, vicious times. Some seem to gleefully relish dropping the floor out from under us. And/or making us feel like it might at any moment.

Turning to popular culture for any explanation is frequently, often correctly, dismissed as a fool's errand, a soft option compared to understanding the world as it actually is. That our favorite shows and a rotating selection of movies seem to be the only stable constants in our lives merely cements their status as spectacle.

This is only one side of the dialectical coin. The political unconscious doesn’t work solely in favor of subjugation. We are creatures of contradiction, of strange desires whose excess can’t always be captured. Crafting a compelling story frequently demands that we regard these healthier, more liberatory impulses (even if the culture industry does ultimately capture them).

Take, for example, the season two finale of Severance. This is a show whose second season could have easily run aground, not despite the originality of its premise, but because of it. Making literal the division between our “work selves” and our “real” selves (our innies and our outies) is a clever and relatable conceit, but could easily become limiting. What to do with the premise? How to ensure the plot remained thematically coherent and didn’t resort to easy gimmicks?

The second season answered those questions. It showed us more corners of the severed floor, stranger parts of an existence designed to be smooth and unthreatening. It built on the Lumon corporation’s cult-like history and neo-Victorian practices, far-flung into frozen wilderness preserves and abandoned mill towns.

Think of the season finale’s Hitchcockian final shots. Innie Mark and innie Helly running back into the severed floor’s windowless depths, Mark’s outie wife Gemma frantically screaming for him on the other side of a locked door, all to the eerie-longing tune of Mel Tormé’s version of “The Windmills of Your Mind.”

It’s a perfect ending, honestly good enough to finish the series with. Particularly juxtaposed with the weirdest scene of the season, rivaled in the show only by season one’s waffle party. The completion of the Cold Harbor project celebrated with… a marching band. Milchick, the quintessential manager — disillusioned and resentful, who can only direct his bitterness with his boss against his subordinates — dancing, stone-faced and menacing. I can remember who I am and how I am being used his moves say. What’s your excuse?

What starts as Mark, Helly, and Dylan barricading Milchick in the bathroom turns into a small-scale insurrection on the part of the (also-severed) marching band. Standing on the desks, Helly speaks: “They give us half a life, and think we won’t fight for it.” So they turn in Milchick’s direction, a room full of severed employees against one unsevered manager. They haven’t a clue who they are, or even what their last names are. They just know that unless they push back, they’ve already vanished.

Inside is all they know. White walls, functional furniture, creepy art, a marching band, goats. It’s all numbers, set like a watch within certain limits and times. Nothing gets better, but at least you can expect it won’t get worse. But then it does, increasingly so. People you love – as unsure of who they are as you – disappear without warning. Attempts to find the truth are thwarted with the cool, dispassionate touch of the bureaucrat.

The growing awareness that it’s bound to happen to you too. The lies pile up. You know that fighting for yourself means in some way preserving this hell, but what other choice do you have if you want to live?

Outside is the real. Not “reality,” but the real: existence outside the tightly controlled fantasy. The place where people die violent deaths, where towns rot in the cold ether. It’s where you finally face yourself, where the real work of building a life begins, sans guardrails. No wonder our instinct is to run from it.

So which half do you fight for?

Header image is from “Cold Harbor,” season two finale of Severance.

Half A Life910KB ∙ PDF fileDownloadClick here for a pdf version...DownloadDaydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

April 15, 2025

The Future Is Here

Disorientation runs deep, and it is certainly persistent. One would think that Donald Trump’s climbdown from his punishing tariffs would be reason for celebration. And it would if it weren’t merely a prelude for something else just as monumentally stupid and destructive. How much more expensive are goods going to become? Will my job still be here in a year, six months, one month? What, ultimately, are the prospects of pushing back when there is a clear political will to cast any dissident into a hole they might never come out of?

Highlighting this epic flail is the fact that we still aren’t sure just how to characterize this new moment we’re in: not just Trump but the whole global rise of the far-right, with its chainsaws, its brimstone rants about trans people and immigrants, its gleeful cruelties and conspiracy theories.

Were the tariffs a death blow to neoliberalism? And if so, do their persistent obstacles mean that free market fundamentalism is alive and well? Is it fascism? Is it still neoliberalism? Fascism with neoliberal characteristics? Illiberal neoliberalism?

These questions become tiresome. I’m partial to the argument that this is “both not yet fascism and not-yet-fascism.” What continues to elude us is the affirmative. What exists in place of the not yet? Do Trump, Netanyahu, Milei and all the rest even know? There’s a good chance they don’t. For the past few years it’s been consensus that neoliberalism is dying, but what replaces it has yet to come into focus. Something something morbid symptoms something something.

Call it serendipity, but, notably, all this comes simultaneously to a debate about the nature of what we call the future. Or, perhaps more specifically, how we conceptualize the future, particularly those of us who spend our time agitating for a better one.

On April 2, Tribune published Luke Cartledge’s review of Liam Inscoe-Jones’ book Songs In the Key of MP3, which lauds artists like FKA Twigs, Earl Sweatshirt, SOPHIE, and Oneohtrix Point Never as “icons of a new internet age.” Inscoe-Jones, and by extension Cartledge, use these artists to push against Mark Fisher’s influential “cancellation of the future” thesis. According to the authors, Fisher’s assessment that neoliberalism – with its privatization and commodification of cultural resources – had effectively stymied cultural innovation was either exaggerated or premature.

While Cartledge broadly agrees with Inscoe-Jones’ arguments, he also asserts that other writers do a more thorough job in rejecting the ways Fisher situated music against time. He particularly highlights the work of Anna Kornbluh, and Paul Rekret’s recent book Take This Hammer: Work, Song, Crisis. Cartledge’s review and its critique of Fisher has prompted a long and thorough response from Mattie Colquhoun on their Xenogothic blog. Colquhoun – former student of Fisher and editor of his posthumously published Postcapitalist Desire lectures – defends Fisher’s thesis and attempts to better situate it in what they see as its various mischaracterizations from Cartledge, Inscoe-Jones, and Rekret.

Cartledge’s review and Colquhoun’s rejoinder are worth reading. So, for that matter, is Rekret’s Take This Hammer, which illustrates music’s relation to work not as a narrow category but as a fundamental pillar of existence under capitalism that touches all facets of life.1 His mapping of the temporalities of trap music, ambient, and post-vaporwave forms is incredibly incisive, and his arguments around Fisher’s “cancelled futures” and “popular modernism” are thought provoking.

I cannot speak to Inscoe-Jones’ book, simply because I haven’t read it. But turns of phrase like “icons of a new internet age” should give heartburn to anyone with brainwaves. The impression is that Inscoe-Jones’ arguments only stay intact by demurring from the insidious forms of social decay instilled by and indeed coded into the internet. From the algorithmic narrowing of sonic variety to the almost lightning fast recuperations of anything remotely novel or dissonant, it is tough to make the case that the internet has been a net positive for music or culture. Arguments to the contrary just sound like something Paul Mason would say fifteen years ago. Too much has happened since for it to be a viable argument anymore.

We could say that artists like FKA Twigs, SOPHIE, and Oneohtrix Point Never (all unique and fascinating artists) represent a dialectical opposite to the all-encompassing enshittification of the internet, an alternative of radically democratic plugged-in ontology. But such a future only needs to be suggested in the first place because of the dominance of futurelessness. Ergo, without simply repeating Colquhoun’s arguments here, I find myself agreeing with their defenses of Fisher’s formulations.

At the risk of stretching the category beyond its usefulness, all forms of capitalism have involved cancelled futures. From the enclosure of the commons that robbed the peasantry of their livelihoods to the automated pop ups reminding us that time without the hustle is wasted. One of Rekret’s most salient points in his arguments is that the Fordism which popular modernism apparently longs for always denied a viable existence to the racialized and oppressed. But most of the white men who supposedly shared in its abundance were also being denied something. Living as an extension of an assembly line, performing the same motions day after day after day, partaking in meals and leisure at only set and allowed moments; these are the characteristics of what Walter Benjamin called “empty time.” Time of dull repetition, each moment largely indistinguishable from the previous one. Time without discovery or evolution. Dull. Numb.

It may be better to be exploited and bored by capitalism than unexploited and starving, but the point is that both exist on a continuum. What we might call the “organic composition” of empty time was unique during the decades of high Fordism. Its mollifying comforts were more accessible on the whole (at least in the “developed world”), its temporal shapes more tightly wound. Hence the significance of the pivot, of the break with empty time provided by mass protest and global revolution. It’s why supposedly privileged students found common cause with lumpen Black militants and why many blue collar workers embraced the counterculture.

This begs a question, not of temporality necessarily, but of historicization. The typical (if oversimplified and static) view of Fisher’s ideas is that popular modernism’s high points fell roughly between 1960 and 1990, while the slow cancellation of the future comes after, concomitant with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the end of the Cold War, and the triumph of neoliberalism.

But if cancelled futures come standard in capitalism, and if some form of popular modernism can be found beyond the fall of Fordism, do these respective terms mean anything? Are they worthwhile categories? Or does their permeability simply turn them into distinctions without difference? Furthermore, now that the system that ended history and canceled the future has itself finally ended, does this mean futurity is back? If so, what does this mean for the construction of an art and a viewpoint that can provide real liberation?

History never sections itself off quite so neatly as our categories would like it to. It never simply ends one epoch to start another. Opposed models of untrammelled trade and protectionism always jockeyed for dominance in capitalism. Whichever prevailed was often down to contingent factors, chance maneuvers or victories for this or that section for this or that class. Similarly, different structures of feeling predominate in various moments by expressing – in admittedly contingent and chaotic ways – the crass drives that keep capital moving.

Neoliberalism didn’t kill the impulse that drove popular modernism, but it did radically disrupt its routes of expression. Keep in mind that while social safety nets were eviscerated, the rate of exploitation overall increased in these decades. Working longer and harder for less in return became an expected part of daily life, leaving less leisure, less time to recover, more stress numbing people’s emotional and intellectual capacities. Time itself became emptier as algorithms made labor more flexible. Strategies for coping became similarly profitable, particularly after everyone’s phone started to give them access to the virtual entirety of all known human information. Doomscrolling became a favorite pastime. What Fisher described as “depressive hedonia,” what’s now becoming known as “cheap dopamine,” further flattens our existence into something more akin to what the situationists called a representation of life, rather than life itself.

We should also keep in mind that part-and-parcel to this, streamlining the narrowing and deadening of daily life into a sequence of undifferentiated non-events, is the shaping of artistic output into something that often denies audiences any sense of alterity. In the post-Spotify age, it is difficult to think of even something as tame as MTV’s earliest years, when programmers enthusiastically featured some rather experimental artists. Let alone the kinds of explosions that characterized popular music through the 60s and 70s. It isn’t that contemporary versions of these same experiments aren’t happening. Just that the algorithm has made them into exceptions that prove the rule. Until they don’t. But that outcome is contingent on forces that have not yet managed to cohere.

This is just one more example of how technology, imprinted as it is with the values of late capitalism, is far more bound to exile us from active participation in history and the future than it is to aid us in creating them. How this looks, however, cannot be understood past mere sketch before it happens. That’s the unpredictability of the superstructure. When we ponder the day when artificial intelligence finally takes our job, we know it won’t be as simple as the Kids In the Hall arms-in-a-vat-of-dead-fish sketch. It won’t be our boss saying “sorry buddy, but corporate gave me no choice” before wheeling in a massive server with a red light that insists on calling you Dave. Until Trump’s climbdown in the middle of last week, it might have looked like a tariff list cranked out by ChatGPT. It still could.

For the time being though, however much the underlying forces of this moment might present in a different shape, its functions and mechanisms remain the same as they ever were. The form has changed, but it has yet to negate the content. The future is here, it’s just not here for you. It never was.

Header image is from Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s art installation Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future.

Daydreams & Paving Stones is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

1An excellent book, whatever disagreements I may have with it. Review forthcoming.