Anika Savoy's Blog

May 23, 2023

How the “Penny Papers” of the 1800s could make or break a woman’s reputation

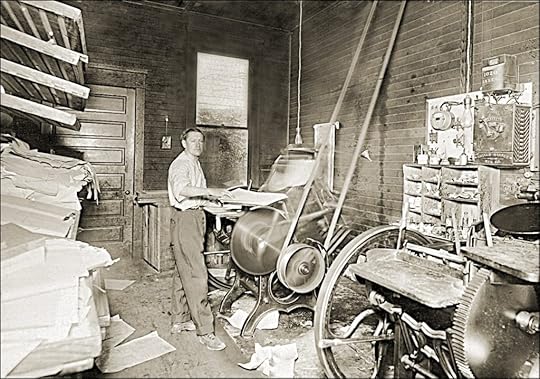

We tend to think of tabloids as a modern-day phenomenon, beginning in the 1970s when housewives purchased them at supermarkets and returned home to read about Jackie Onassis’s latest scandal. In fact, The National Enquirer was first published in 1926, and cheap newspapers covering salacious crimes and celebrity gossip, also known as “penny papers,” first appeared in the 1830s.

At the time, Western civilization was undergoing a communications revolution in which the advent of new technology- steam-driven printing presses and machine-made paper, enabled working-class readers to enjoy sensationalized articles comprising shorter sentences and paragraphs and simple vocabulary.

Woe to the woman who became the subject of public discourse, for the penny papers could devour her reputation faster than an energy vampire sucks the soul from his unsuspecting victim. In the first book of the Ungilded Series, The Ghost in Her, I describe the destitute Irish heroine, Maggie O’Connor, visiting the local library. Maggie references Flash, a tabloid that covers the titillating events of NYC’s Bowery District:

I walked to the west end of the room and entered the light-speckled treasure trove of weeklies and dailies that illustrated in words and etchings the activities of a city that never slept. So many vestiges of so many secret lives. The selection was enormous, ranging from the widely read New York Herald to street-smart, scandal-ridden dailies like Flash. In my fantasy world, I would be a Flash reporter. I was sure that I could describe the flamboyant happenings of the Bowery with more local color than a visiting writer on assignment.

Little does Maggie know that she will soon become Flash’s hottest damsel in distress. When Maggie is wrongfully committed to the NYC Lunatic Asylum, Flash gives her a new nickname, “Mad Maggie.” The derogatory moniker is intended to shape public opinion while erasing Maggie’s dignity, not unlike the tabloids that label Meghan Markle as, “The Difficult Duchess.”

When Maggie emerges triumphant and marries an architect who works for Andrew Carnegie, Flash dubs her “The Bowery Princess.” The title catches on, leading residents in the tenement district to proudly cheer for The Bowery Princess as Maggie and her groom throw candy to the crowds lining the Bowery streets on their wedding day:

“Don’t forget the candies!” Gershom shouted. I reached into the crate and tossed handfuls of hard candies and pennies over the crowd. People ran madly about, gathering the gifts.

“Thank you, Bowery Princess!” a little girl resembling wee Mary cried out. While the Flash reporter may have dubbed me the Bowery Princess with tongue firmly resting in cheek, the locales embraced the title with pride.

“Stop the carriage,” I told the driver. “You!” I called out, gesturing to the little girl.

Dumbstruck, she pointed her thumb to her chest.

“Yes, you, little love. Come here. I have a gift for you.”

She tripped across the roadway. I reached into the pocket of my tea gown and produced my mother’s roll-plate pin. She took hold of the pin, marveling at the enameled leaves.

She stared up at me, her eyes shining through the tears. “Thank you, Princess Maggie!”

“One day,” I replied, “you too will be a princess.” Seeing her wee face light up made the darkness that I experienced at the asylum miraculously melt away.

Whether the year is 1888, or 2023, media coverage can be a blessing or a curse. Fortunately for our heroine, Maggie O’Connor, the narrative turned in her favor!

Sources

Belonsky, Andrew, Sept. 8, 2018. “How the Penny Press Brought Great Journalism to Populist America” Daily Beast. https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-the-penny-press-brought-great-journalism-to-populist-america

Klein, Maury, 1996. “When New York Became the US Media Capital” https://www.city-journal.org/html/when-new-york-became-us-media-capital-11973.html

February 14, 2023

The “Murderous” Corsets of The Gilded Age

/*! elementor - v3.18.0 - 08-12-2023 */.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-stacked .elementor-drop-cap{background-color:#69727d;color:#fff}.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-framed .elementor-drop-cap{color:#69727d;border:3px solid;background-color:transparent}.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap{margin-top:8px}.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap-letter{width:1em;height:1em}.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap{float:left;text-align:center;line-height:1;font-size:50px}.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap-letter{display:inline-block}

/*! elementor - v3.18.0 - 08-12-2023 */.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-stacked .elementor-drop-cap{background-color:#69727d;color:#fff}.elementor-widget-text-editor.elementor-drop-cap-view-framed .elementor-drop-cap{color:#69727d;border:3px solid;background-color:transparent}.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap{margin-top:8px}.elementor-widget-text-editor:not(.elementor-drop-cap-view-default) .elementor-drop-cap-letter{width:1em;height:1em}.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap{float:left;text-align:center;line-height:1;font-size:50px}.elementor-widget-text-editor .elementor-drop-cap-letter{display:inline-block} Women’s fashion at the turn of the century was constrictive, to put it mildly. In some cases, it was lethal.

In the opening scene of The Ghost in Her, the heroine, Maggie O’Connor, walks along a desolate back street with her sister Nessa, who is in child labor, and eyes an advertisement for corsets.

Excerpt

Nessa’s breathing grew labored—the long, desperate grunts giving way to staccato gasps. Looking for a distraction, I crossed the cobblestone path and read an advertisement on a neighboring doorway.

Madame Martha’s Magnificent Corsets.

A Marvel of Comfort and Elegance!

Beneath this proud proclamation was a detailed sketch of a full-bodied woman, cleavage bulging and hips bursting, with a nearly pencil-thin waist. Dressed in a fashionable gown, she admired a ring on her outstretched hand. Long rippling lines stretched from the stone, the artist’s amateur attempt at depicting its dazzling radiance.

“Tell me what it says,” Nessa weakly said.

I snickered and read: “The girdle this lady wears needs no breaking in. It’s as comfortable as a satin under-slip.”

“Impossible,” Nessa dryly remarked.

The inspiration for this scene came from an actual advertisement for corsets that I discovered in Nellie Bly’s groundbreaking story, Ten Days in a Madhouse, which exposed the inhumane conditions of the NYC Lunatic Asylum in the late 1800s.

Ignore my chicken-scratched notes. I read Ten Days in a Madhouse early in the creative process while working out the plot and character details using different names.

In the opening scene of The Ghost in Her, the advertisement for Madame Martha’s Corsets is intended to juxtapose the gritty reality of what Maggie and her sister Nessa were experiencing at that moment. Dressed in ragged clothing and battered old shoes, the thought of wearing a girdle that unnaturally slims a woman’s waist by crushing her innards is nothing short of absurd.

For me, corsets are a symbol of the suppression of women in the 1800s. In order to achieve an unnatural hourglass figure, women pulled the laces as tightly as possible, resulting in reduced lung capacity. In some cases, the corsets caused atrophied back and chest muscles, and the compression of internal organs. Imagine digesting a five-course meal at the famous Delmonico’s restaurant dressed in a lacy vice. Some autopsies even evidenced rib cage deformity due to long-term corset usage.

Desperate to maintain the illusion, many pregnant women wore special corsets designed to fit their expanding bellies. Here’s a photo, taken from The 1895 Edition of The Montgomery Ward Catalog depicting a corset that allowed the new mother, puffed up and exhausted, to maintain her figure while nursing her infant.

Women finally caught on to the dangers of being “tight-laced.” In 1873, author Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward wrote:

Burn up the corsets! … No, nor do you save the whalebones, you will never need whalebones again. Make a bonfire of the cruel steels that have lorded it over your thorax and abdomens for so many years and heave a sigh of relief, for your emancipation I assure you, from this moment has begun.

Something tells me that Ward would have also burned her bra if she lived in modern times. It all begs the age-old question, “How far should women go to achieve an appearance that is pleasing to men’s eyes?”

As for me, I’ll stick with sports bras and leggings, sans corsets. When faced with choosing comfort or image, I’ll pick comfort any day of the week. Evidently, the heroine of The Ghost in Her, Maggie O’Connor, agrees. The modest muslin dress she wears on the book cover allows her to walk with fluidity and grace whilst staring at fairies on a moonlit street.

Sources:

https://www.geriwalton.com/death-by-corset-and-tight-lacings-in-the-1800s/https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2015/11/16/how-corsets-deformed-the-skeletons-of-victorian-women/?sh=4d785f7e799chttps://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/elizabeth-stuart-phelps-grandmother-bra-burners/If you’re interested in learning more about Nellie Bly and her time on Blackwell’s Island, and you need a good laugh, check out this Drunk History Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7ZPl4FHyxc

“Burn up the corsets… from this moment has begun.”

December 5, 2022

To Thine Own Self Be True

/*! elementor - v3.18.0 - 08-12-2023 */.elementor-heading-title{padding:0;margin:0;line-height:1}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title[class*=elementor-size-]>a{color:inherit;font-size:inherit;line-height:inherit}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-small{font-size:15px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-medium{font-size:19px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-large{font-size:29px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-xl{font-size:39px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-xxl{font-size:59px}Trying to look like Annie Lennox at McGill, 1985.

/*! elementor - v3.18.0 - 08-12-2023 */.elementor-heading-title{padding:0;margin:0;line-height:1}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title[class*=elementor-size-]>a{color:inherit;font-size:inherit;line-height:inherit}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-small{font-size:15px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-medium{font-size:19px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-large{font-size:29px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-xl{font-size:39px}.elementor-widget-heading .elementor-heading-title.elementor-size-xxl{font-size:59px}Trying to look like Annie Lennox at McGill, 1985. Hi, it’s Anika Savoy! Welcome to my blog. Now I know what some of you are thinking: Anika Savoy looks a lot like true crime author Anne K. Howard. Okay, I’ll confess. We are one in the same. I had a good run with my true crime book, HIS GARDEN: CONVERSATIONS WITH A SERIAL KILLER, when it came out in July 2018. What followed were television shows and too many presentations and podcasts to count. But when I got to work on my second true crime manuscript, I found that I had lost all interest in researching and writing about grisly murders and the human suffering that ensued. Writing true crime was sucking the life out of me.

Depression inevitably followed. I had recently retired from practicing law for the sole purpose of writing true crime. Now what the hell was I supposed to do? Making matters worse, the pandemic hit.

Hanging around. Nothing to do but frown.

Rainy days and lockdowns always get me down.

I put the half-written true crime manuscript to the side and asked myself, ‘Anne, what do you really want to write?”

Flashback to 1985. I was in my first year at McGill University, studying English Literature. I decided to enter a creative writing contest. While other entrants were writing New Yorker style short stories, I wrote a fairy tale. Yes, a fairy tale. It won, and you can still locate MOUNT LUMINAC’S LIGHT on the shelf at the McClennan-Redpath Library in Montreal, typos and all.

Fast forward to 2020. Like most Americans, I desperately needed an escape. Ideas started to come to me about a fairy tale universe set in the Bowery, NYC, circa 1888. I gave myself permission to have fun with the story, to let my imagination run free with otherworldly characters and an outrageous plot. And yes, I also gave myself permission to write a feel-good romance. Not nearly as cool as writing true crime, but so much more enjoyable.

I just put the finishing touches on my paranormal historical romance, THE GHOST IN HER, written under the penname of Anika Savoy. I’ll be submitting it to agents and one publisher (Carina Press, a division of Harlequin) next week. This blog will keep you updated on the ups and downs of finding an agent and a publisher. I will also share some of the fascinating research that I did when writing the book. I’ll post about The New York City Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island, where impoverished and often very sane women were housed; NYC’s colorful and squalid Bowery district; and fashion and recipes from the Victorian era. We’ll have fun together, I promise. I’ll also include some excerpts from THE GHOST IN HER, which is book one in a series that takes place in turn-of-the-century lower Manhattan.

Rest assured; the thrill is not gone for me when it comes to writing paranormal historical romance. More to come!

The Hidden Horrors of Blackwell’s Island

Visit Roosevelt Island today and you will encounter a pleasant oasis set apart from the hustle and bustle of New York City. That’s not to say that it is vacant of modern structures. In addition to a high-tech campus, restaurants, upscale apartment buildings, and a trendy hotel, you will walk upon grassy parklands teeming with geese and get terrific views of Manhattan.

It’s a far cry from the macabre isle that it once was. In the late 1800’s, when my upcoming paranormal historical romance takes place, the narrow strip of land in the East River was called Blackwell’s Island. It was home to prisons, alms houses, and the New York City Lunatic Asylum. In other words, it was a place to which the most marginal members of society were banished.

Since Blackwell’s Island was closed to the public, horrific abuses often went unnoticed- and unregulated. At the NYC Lunatic Asylum, epileptic and schizophrenic patients were plunged into ice-filled tubs, a treatment euphemistically called “hydro-therapy.” For calmer patients, a daily bath was shared with a long line of inmates. God help you if you were at the end of that line, as the water would be black and filled with lice. Straight jackets, euphemistically called “camisoles,” beatings, and solitary confinement were routinely employed to keep the patients in line, and addictive opioids like laudanum and morphine were handed out like candy.

The doctors who worked in the facilities were usually fresh out of medical school, and the opportunity to “practice” on mental patients and prisoners was one step above working on cadavers. Many psychiatrists, freakily called “alienists” at the time, believed that mental illness involved demon possession. Mistakes were made. Innocent people died. Such was life in 1888, when the heroine of my new book entered the asylum.

An ambitious young journalist, Nellie Bly, faked insanity to write an expose on the asylum. A local judge, seeing Bly dressed in schmattes and incoherently mumbling, quickly ordered her involuntary commitment at the asylum where she observed the ice baths, the beatings, the degradation, and death in her midst. Once Bly revealed her identity as a reporter, she was released from the NYC Lunatic Island and later wrote of the female patients, “I left them in their living grave.”

Ruins of the Smallpox Hospital today.

Ruins of the Smallpox Hospital today. The asylum closed in 1894. While the ruins of a smallpox hospital remain on the island, all that is left of the NYC Lunatic Asylum is a domed octagonal structure that once served as the admissions building. Ironically, upscale apartments are now attached to the Octagon.

Here’s a brief excerpt from my upcoming paranormal historical romance describing the plight of the heroine, who has been involuntarily committed to the asylum. In this scene, Maggie discusses her fears with a widow (who is actually a ghost commissioned to assist Maggie) on the boat ride from midtown Manhattan to the shores of Blackwell’s Island. I hope you like it.

Are they sending you to the lunatic asylum?” the widow softly inquired.

“Yes.” I whispered. The boat rocked and moved forward, fueling my despair.

“I’ve been there,” said the widow.

“You have?”

She nodded. “Years ago.”

“Is it as horrible as they say?”

“It is a despicable place,” the widow replied. “A dragon has charge over the wards. Her name is Nurse Stoddard. She is a heartless beast. Watch out for her.”

“Is there anything else that I should know?” I eagerly asked. “Is there a way to escape?”

The widow lifted the string of polished stones. They glimmered like mica against a slender beam of moonlight streaming through slats in the floor above.

“There is no way to escape,” she replied. “Even if you did, how would you cross the river and get back to Manhattan? A guard lives at the pump house. He strolls the shore and keeps a lookout for escapees sneaking into boats.”

“What if I swam across the river?” I asked. The quarter of a mile trek through warm waters in the summer would be difficult, but not impossible.

She shook her head, the black crepe crumpling against her collar. “River Runners always drown. The currents are strong.”

My shoulders dropped. “But how will I survive in a madhouse?”

“The dragon possesses a large bunch of keys,” the widow whispered. “They jingle from a rope belt tied to her waist. Each one is shaped differently. There is a hidden cellar beneath the building called The Lodge. It is where they store dead patients before they bury them in Potter’s Field. There is a small door in the corner of the cellar. It leads to catacombs that reach deep into the earth. A skeleton key opens that door.”

“Does it lead outside?” I asked.

“It leads to freedom,” she whispered.

My heart leapt with hope. “But how will I cross the river once I have escaped?”

“I told you,” the widow said, “there is no way to escape the asylum, but what you discover in the catacombs will set you free.”

The deceptively calm waters contain strong currents.

The deceptively calm waters contain strong currents.  The Octagon, once part of the asylum.

The Octagon, once part of the asylum. Sources:

“Ten Days in a Madhouse,” Nellie Bly, 1887

“Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad & Criminal in 19th Century New York,” by Stacy Horn, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2018

A Gnome. A Time Machine. The Gilded Age. What could possibly go wrong?

It’s Christmas Eve. A gnome arrives at your doorstep. He looks like Santa Claus’s mini-me; roly-poly with a long white beard and a red velvet cap. He introduces himself as Randy. Yes, the gnome’s name is Randy. His stubby little finger points in the direction of an evergreen tree on your front lawn, beneath which sits a time machine. Randy explains that for Christmas this year, you are being given a wondrous gift from the folklore gods. The rusty old machine will transport you to New York City at the height of the Gilded Age, where you will remain for the next twelve hours.

It’s Christmas Eve. A gnome arrives at your doorstep. He looks like Santa Claus’s mini-me; roly-poly with a long white beard and a red velvet cap. He introduces himself as Randy. Yes, the gnome’s name is Randy. His stubby little finger points in the direction of an evergreen tree on your front lawn, beneath which sits a time machine. Randy explains that for Christmas this year, you are being given a wondrous gift from the folklore gods. The rusty old machine will transport you to New York City at the height of the Gilded Age, where you will remain for the next twelve hours.

Without hesitation, you run to the machine and step inside. Randy slams the door shut and off you go to the land of gold-plated carriages, five course dinners at Delmonico’s, and extravagant parties at the Vanderbilt Mansion.

In the blink of an eye, the door creaks open. You step outside to see that you are not in upper Manhattan, as you had stupidly assumed. You are in lower Manhattan. The Bowery, to be exact. Randy, you devilish twerp. Here are a few takeaways from the next twelve hours of your life- twelve hours that you never want to live through again:

The Bowery stinks. Literally. People dump the contents of their chamber pots from upper story windows. The fecal stew douses the heads of unfortunate pedestrians walking past. You quickly learn to walk beneath the awnings, designed for that purpose. A noxious mixture of manure and urine from horses and oxen, not to mention stray dogs and cats, cakes the streets. It’s winter and people wear coats over their ragged clothing. Nevertheless, in the absence of indoor plumbing, they still reek of body odor so powerful that any cologne used to cover it up only makes it worse. And the halitosis! Ugh. You feel like handing out tubes of toothpaste and bottles of Listerine.

Indoor plumbing was a luxury that Bowery residents did not enjoy.

Indoor plumbing was a luxury that Bowery residents did not enjoy.

My, there sure are a lot of flop houses and brothels. The oldest profession is thriving in the Bowery, but the women are not the well-dressed courtesans that frequent the restaurants and ballrooms uptown. Plain-faced, haggard widows transact for a loaf of bread. Girls, some of them as young as twelve, walk the streets. Even younger girls are forced to offer their services in the backrooms of beer gardens and brothels. You want to cry, but what’s the point? They are all dead now. The past is the past.

You head for the tenement district. You visited the Tenement Museum in the Bowery last summer, and you expect to see the sturdy brick buildings that you saw on that tour. You spot a few, but the most common living quarters are ramshackle wooden edifices with lopsided roofs and very few windows, resulting in poor ventilation and deadly fires. Families are packed together like sardines. No wonder so many people are pale-faced and hacking with some sort of deadly virus or disease.

Nicer brick tenements still stand in the Bowery. The wooden ones are gone.

Nicer brick tenements still stand in the Bowery. The wooden ones are gone.

Regulations to keep air pollution at bay- what are those? Clouds of black ash cover the facades of every building. Housewives stretch damp garments on strings hanging between fire escapes. The freshly washed dresses and petticoats are floral corollas in a sunless garden. By morning, they will all be covered in soot. The noise pollution is no better. The deafening and persistent rumbling of the El Train bursts with a thunder that booms through the neighborhood, shaking buildings in their foundations, and dripping lines of oil on the roofs. Vendors shout, children scream, morphine addicts moan for their next fix, and the yawping of drunken kerfuffles pierce the air. If only you brought your migraine pills….

‘Good grief,’ you think as you climb back into the time machine after twelve wretched hours. Was there anything positive about that experience? Yes, the immigrants. The Irish, the Jews, the Germans, the Chinese. And those who never chose to come to this country, African Americans who migrated north following the Civil War. Many had returned your curious gaze with vacant eyes, but in some of the faces you saw hope. The same hope that created The City of Dreams.

You emerge from the time machine. Randy approaches. He asks if you enjoyed your trip. You want to kick his pudgy little ass to kingdom come. Instead, you shake his tiny hand. “Come on inside for a cup of spiced eggnog,” you say.

Randy flashes a diabolical smile and follows you inside.

November 14, 2022

Anderson Cooper takes a spirited deep dive into his Gilded Age ancestry.

The nightmare began at the beginning of the 19th century, when an eleven-year-old boy named Cornelius Vanderbilt dreamt of making vast quantities of money that would one day set him apart as the richest man in America. Vanderbilt followed the rule book for all aspiring tycoons: work your ass off, ruthlessly attack your competitors, even if one of them is your own father, and live below your means.

The nightmare began at the beginning of the 19th century, when an eleven-year-old boy named Cornelius Vanderbilt dreamt of making vast quantities of money that would one day set him apart as the richest man in America. Vanderbilt followed the rule book for all aspiring tycoons: work your ass off, ruthlessly attack your competitors, even if one of them is your own father, and live below your means.

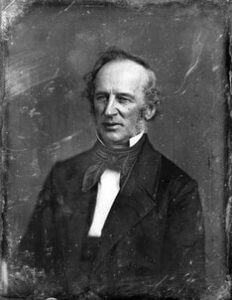

In contrast, Vanderbilt’s wives and children followed the rule book for entitled heirs of the super-rich: travel the world, throw lavish parties while the working class suffers, viciously gossip about ‘friends’ in your circle to your heart’s delight, and above all, recklessly squander the wealth that dear old crusty Cornelius labored for all his life. By the way, do you see a faint resemblence between Cooper and Cornelius? I do.

American business magnate, Cornelius Vanderbilt.

American business magnate, Cornelius Vanderbilt.

When I first learned that Anderson Cooper was the great-great-great grandson of the larger-than-life Cornelius Vanderbilt, aka “The Commodore,” I felt the same kind of envy that I experience upon learning that someone is a trust fund baby, privileged since birth. Like most, I assumed that Cooper had inherited millions of dollars and his hefty salary at CNN, about 12 million per year, was simply frosting on the cake. ‘Must be nice,’ I jealously thought.

But that’s just not the case. By the time Cooper entered the mix as Gloria Vanderbilt’s beloved son, almost all of the Vanderbilt money had been squandered by his ancestors, most seemingly clueless about the importance of investments and living on a ‘budget’ that would make most of us swoon. Cooper shares tale after tale of grossly impractical expenditures that soaked millions from the family fortune: The Breakers, a 70-room mansion in Newport, Rhode Island, the proverbial white elephant with outdated plumbing and exorbitant maintenance fees, and the famous Vanderbilt mansion on 5th Avenue, built in 1882 to last 1000 years, it was demolished in 1926.

“The Breakers” was the grandest of Newport’s summer “cottages.” Renaissance Revival, circa 1895.

“The Breakers” was the grandest of Newport’s summer “cottages.” Renaissance Revival, circa 1895.

Vanderbilt: The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty, is beautifully written. Cooper narrates the audible version with the same dry air of detachment that he employs when discussing the nightly news. He has a sharp eye for the hidden nuances, contradictions, and hypocrisies of people living in a gilded age in which social climbing was an artform. He does not seek to defend them or mythologize them. He simply tells it like it was… and is to this day. Exorbitant wealth and good character mix about as well as oil and water. That was true at the turn of the century, and it’s just as true now.

Highlights: the ‘Grey Gardens’ plight of Alice Vanderbilt, donating The Breakers to a nonprofit for public tours only to be forced out of her upstairs living quarters in old age; the heroic death of Alfred Vanderbilt aboard the Lusitania; Cooper’s mother, Little Gloria, not-so-happy at last after enduring a prolonged and toxic custody battle as the richest girl in the world; and the self-sabotaging journey of literary great, Truman Capote, friend and betrayer to many of NYC’s elite.

Kudos to Cooper for casting his mother, fashion designer Gloria Vanderbilt, in a brutally honest yet affectionate light. Like her predecessors, Gloria thought that money grew on trees and her squandering was limitless. To her credit, she created a best-selling clothing line and loved her sons. At the end of her life, Cooper was working overtime to pay his mother’s bills, not just for round the clock nursing care, but also for her impulsive purchases. No wonder he was glad to never receive a dime from the fallen Vanderbilt estate. It enabled him to learn the value of hard work and yes, even balance a checking account- two important traits that most of his ancestors never quite seemed to grasp.