Martha Conway's Blog

February 19, 2023

iPhones, Community, and The Physician’s Daughter

A FEW WEEKS AGO, when my husband went to have dinner with a colleague, I decided to get take-out from my favorite Greek restaurant. I was halfway home with my food in a paper bag when I realized I didn’t have my cell phone with me anymore. I went home anyway to get my iPad, which has the app “Find my Phone” on it, thinking that at the very least I could learn whether my phone was still in the area or if someone had pickpocketed me (seemed unlikely) and then absconded with it.

But good news: I discovered that my cell phone was still near the restaurant on Divisidero Street, which is a very busy street in San Francisco. But when I got there I couldn’t find it. I tried sending an alert to my phone but the street was so noisy that I couldn’t hear it. Also, “Find my Phone” needs wifi, which of course I didn’t have once I left my house.

I probably spent nearly an hour walking up and down two city blocks looking for that phone. But I found help everywhere. A hair salon gave me access to their wifi. A liquor store owner called my phone number several times both from a landline and his own personal cell phone. A teenage boy who was working at his father’s pizza parlor patiently helped me set up “My phone is lost” (I had to go back to the hair salon and its wifi to activate it, however). Random shop customers, overhearing my story, bade me good luck in cheerful voices.

Finally, I asked a man in a camel-colored coat, who had just parked his car where I’d originally parked mine, if he’d seen it. No, but I could look under his car if I wanted. I’d searched there before but I looked again. After a minute I heard a “Whoo-wit”— a kind of Hey, you! call. I turned around. And there was the man in his camel-colored coat holding up my phone. It was cracked to bits, clearly run over by multiple cars, and someone had placed it out of (more) harm’s way up on the fire hydrant.

I was exuberant. But the phone was finished.

The Physician’s Daughter is about a young woman in 1865 who wants to become a doctor like her father. Naturally I did a lot of research on female doctors of that era, and I found that nearly every one had fathers or husbands who championed them. My character, Vita Tenney, had no such champion, at least at first. But she is persistent in following her dream and finds help from other sources; including a doctor who’d been drummed out of the Civil War, fellow boarding house residents, and, eventually, her estranged husband. As I developed the story I thought a lot about all the obstacles Vita would face, and I carefully built these into the plot. But the help she receives from unexpected places—well, many of these came as a surprise, even to me.

The Physician’s Daughter is about persistence and ambition, sure, but it’s also about community. This is where Vita finds so much help, and it’s also what her estranged husband, a damaged war veteran, is unconsciously looking for. The morning after my cell phone adventure, I woke up knowing that I will need to buy a new phone—but the experience actually landed on the plus side for me. Although at first Vita was only interested in the science of medicine, by the end, like these random Divisidero Street strangers, Vita helps people because she wants to help them.

You can read what people are saying about The Physician’s Daughter here…

https://marthaconway.com/the-physicians-daughter

And buy it here!

https://www.amazon.com/Physicians-Daughter-engrossing-historical-fiction-ebook/dp/B098Q7YH79/

As always, thank you thank you for your support!

Warmly,

Martha

November 8, 2022

Say yes to the yes

I’VE BEEN WORKING on a story that’s set in Ireland during World War II. One character—and I’ve yet to decide if he’s a good guy or bad guy (he’s a little bit of both)—tells my protagonist:

“You know what the opposite of fear is, don’t you? It’s abundance.”

“You mean only rich people aren’t afraid?”

He shakes his head. “It’s not what you have. It’s what you think you have.”

Is this true? Or is it just a pretty phrase? I have no idea where it came from. Some part of me I don’t access much, I think.

Writers, even the most successful ones, hear “No” as much as (or more than) they hear “Yes.” No one likes every book. I’ve definitely disliked books (rather strongly at times) that are generally praised.

But in truth everyone—not just writers—hears “No” as much as “Yes.” The question is: what do we choose to focus on? Can we change our focus to all the times we hear “Yes,” I wonder? Because that’s what brings forth abundance. That’s what brings our own abundance to mind.

I’ve just thought of three recent incidences where someone has said yes to me. It feels good! Try it!

Happy holidays, and here’s to more of the Yes.

My latest novel, The Physician’s Daughter, is a tale of ambition, betrayal, and love. It is on sale now at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookshop.org.

July 12, 2022

Women can’t be doctors because they’re needed to make tea

“Women’s nerves are too fragile to practice medicine,

and they’re needed to make tea.”

Where did I find this quote, which in my notes I have attributed to the Journal of the American Medical Association? Usually I’m scrupulous about dates and publications. But it was not an unusual sentiment for the time, which is maybe why I jotted it down and moved on to whatever it was I was really researching (how Victorian doctors dealt with pre-eclampsia, perhaps).

Women doctors! What a concept! When my first child was born (almost a month early), the male doctor I’d been seeing during my pregnancy was on vacation. A tall, gentle, female doctor I’d never seen before examined my newborn son. And I knew, just by the way she held him, that I wanted her to be my son’s pediatrician. Her gender didn’t matter to me, but the way she doctored did.

Dr. Miller. She’s the best.

For centuries, everywhere around the globe, the idea of letting women examine patients—complete strangers! naysayers often emphasized—was disparaged. Ridiculed. Held up as dangerous. But wouldn’t women feel more comfortable with women doctors, one argument went? This was, after all, the era of the “Ideal Woman” — sensitive, delicate, sedentary. (“The indoor woman,” some reverently called her.) And weren’t male doctors a bit, ahem, indelicate in their examinations? For a while—staving off the campaign to accept women as doctors— the learned men of medicine discussed how male doctors could examine their female patients in a more seemly way, as if this would solve the whole problem.

The Respectable Gynecological Examination

The Respectable Gynecological ExaminationDr. William Smellie (yes that’s his real name), an 18th century British obstetrician, suggested that male doctors wear a loose nightgown instead of their regular clothes when they assisted women in labor—to ease their fears. (Would it, though?) Doctors were also exhorted to avoid eye contact and idle chatter with their female patients; I’m not sure that would make me feel more comfortable, either.

But women passionate about studying medicine prevailed. They went to medical school, often surrounded by hostile men (Harvard students threw squishy tomatoes at them). They performed autopsies; they delivered babies; they amputated limbs; and they performed surgeries. In 1860 there were about 200 women practicing medicine in the United States. By 1800 there were 2,400 women doctors; and by 1900 there were more than 7,000.

Today, over one-third of all doctors in the U.S. are women.

Last summer my husband had a severe bicycle accident that landed him in the ICU. He recovered beautifully, thanks to all the excellent medical attention he received at San Francisco General (now renamed Zuckerberg San Francisco General; Mark Zuckerberg’s wife, Priscilla Chan, was once a pediatrician there). When I asked my husband if he’d had any women doctors over the course of his stay, he said yes.

“How many?” I wanted to know.

“I’d say there was an even mix of male and female doctors, and the same with nurses.”

And I’d say that’s how it should be.

•

Martha Conway teaches creative writing for Stanford University’s Online Writing Certificate program. Her forthcoming novel, The Physician’s Daughter, will be available in the United States in September.

Receive Martha’s quarterly book news, including events and writing tips, here.

September 12, 2021

Exploring Your Main Character

Who is the protagonist of your story? Sometimes as you are building a story—outlining, writing notes, running through scenes in your mind—you realize that the main character is not the most interesting character. This might prompt you to change your protagonist. After all, any story can be told from any viewpoint. The main criteria is to make your point-of-view character compelling to the reader.

These exercises are designed to flesh out your character’s traits. You want to make sure your character is interesting; what about her stands out? She must be someone that the reader can empathize with sooner or later, even with all her flaws and limitations. And shemust have flaws and limitations. If she’s too “good” she will be boring.

Remember that your protagonist must be a character who can change. Lejos Egri describes the protagonist as “the eternally changing character who forever reacts … to constantly changing internal and external stimuli.” As readers, we want to witness the minute changes and adjustments that characters make as they navigate their world. It’s a good idea to keep that in mind when we’re thinking about each of our characters.

These exercises are a way of getting you to put down on paper some character details, both details you’ve thought about before and ones that you are just making up now. You don’t have to keep all of these traits for your character. It’s just to get the wheels started. As you hone your characters, you will change details about them. For instance, you may begin thinking your character is an only child, but later give him a younger sibling who competes with him.

Writing Exercises:

Write down as many specific traits about your character as you can: gender, age, race, social class, sexuality, level of education, place of birth, number of siblings, current home, any special abilities.Write ten unusual facts about your character (for instance, she never uses a pillow when she sleeps; he whistles through his front teeth when he’s nervous). After that write then ten lies.Write ten different ideas about what your character wants. Now write ten different ideas about what he or she needs.Longer Writing Exercises:

Write a one-page scene in which your character is asking a teacher for an extension on a writing assignment, and include at least one trait or fact from your writing exercises (above).Write one page using this prompt, from the point of view of your main character: “I told myself that what I wanted was … but that was a lie. What I really wanted was …”August 9, 2020

The Physician’s Daughter: Sneak Peek

June 1865

Lark’s Eye, Massachusetts

Vita was sitting on the front stairs in a shaft of sunlight reading On Diseases Peculiar to Women when they carried the Boston man into her house. It was Tuesday, so her mother and sister had gone into town to visit Aunt Norbert. Vita was waiting for her father to emerge from his office, once a front parlor, which was directly across from the staircase. She knew he was in there although for the last thirty minutes—she squinted at the watch pinned upside down to the shoulder of her dress—she’d heard nothing, not even the shush of a newspaper page turning.

Her brother’s parakeet Sweetie was perched on her shoulder. “What does he do in there all day?” Vita asked her. Sweetie repositioned her claws and butted her pale feathery head against Vita’s ear—the triangular fossa. Triangular fossa, scapha, auricular lobule, Vita recited. Parts of the outer ear.

She was just about to give up her vigil when she heard the sound of carriage wheels on the gravel drive, and a man shouting:

“Dr. Tenney! Dr. Tenney!”

She stood up. The front door banged open, and two men came into the house carrying a third man by the armpits and ankles. Sweetie flew off Vita’s shoulder to the fixed safety of the newel post.

“Dr. Tenney!”

Maneuvering, the men knocked over the little oak table with its double-wick lamp. Now there was glass on the floor.

“Dar?” Vita called. Like her brother and sister, Vita called her father Dar and her mother Mitty—her older brother Freddy’s attempt at saying their names, Arthur and Marie, when he was a baby.

Her father opened his office door and stood in the doorway, unshaven and wearing the same gray waistcoat he’d been wearing for three weeks straight. For some reason he looked at Vita first.

“Stop shouting.”

Sherman Tillings, who owned the saddler and the public stable and had a wife named Thankful, was at the injured man’s head; Vita didn’t recognize the other man.

“We was just changing horses for the Boston coach,” Mr. Tillings explained. “He collapsed on the porch, didn’t say a word. Where can we set him?”

Her father directed them to the long sofa against the windows in his office, where the light was best.

“Not one word,” Mr. Tillings went on, lowering the man onto the green velvet upholstery. “A Boston man. You see where his forehead is swelling? Cracked the rail when he fell.”

The man’s face—closed eyes, open mouth—had a waxy tinge, like skin on hot milk. Was he breathing? Vita, who had seen many an injured man or woman brought into their house, watched his chest. She couldn’t see any movement.

“Shall I fetch a blanket?” she asked. It’s important to keep the extremities warm, her father always said. He was sitting on the stool next to the sofa, and he bent to put his ear against the Boston man’s mouth. Then he straightened up and lay two fingers against the man’s limp wrist.

“No pulse.”

He told Tillings to prop the fellow up as he opened a bottle of whiskey. Holding the bottle by the neck, he pushed back the man’s head and poured a glug down his throat. “To encourage the swallowing reflex.” But the man didn’t swallow. Two uneven streams ran down either side of his beard.

“Get a hot poker, set it against his head, that’ll shock him awake,” Tillings said.

“Or blow tobacco smoke into his mouth,” suggested the other man—the coach driver?—who was small and freckled with wiry red hair.

“Nonsense.” Her father began massaging the man’s chest. “But perhaps I can work up the heart.”

“Work it up?” Vita asked. The human heart, with its auricles and ventricles and valves, its precise oscillation, was, to her, a miracle of engineering. She had seen her father perform countless exceptional procedures —setting badly broken bones, draining pustulous head wounds, and once making an incision into a man’s bladder to extract a stone the size of a fig—but she had never seen him restart a stopped heart. Scientifically, it seemed impossible, but there was so much she didn’t know. She stepped closer.

“I thought you were getting a blanket,” her father said.

When she came back into the room they were pushing the man forward and back, bending him at the waist as though he were a lever. They stopped long enough for Vita to spread the dark green blanket over his legs. The man’s eyes were not altogether closed although he was clearly unseeing. He had a very round face with a cluster of white warts under one eye; whiskey drops glistened on his beard. She touched the top of his hand. It was still warm. Of course, she thought, it will take a while for the blood in the body to cool.

The three men began again to pull him up and shake him, set him down, pull him up. Meanwhile her father became angrier and angrier, as though the unlucky man was clinging to death just to vex him.

“Enough!” he said at last. “He’s clearly past saving.”

Mr. Tillings stepped back and took off his hat. By now the Boston man’s mouth was fully open, and his neck and shoulders were unnaturally still. There was no rise and fall to his chest. Nothing. For a moment, Vita could almost understand it: how the body, with its layered, exact systems and its rhythmic machinery, might, at any moment, halt absolutely. Here was proof. However the next moment the man, a stranger on her father’s green sofa, didn’t seem quite real.

“Rupture of the heart,” her father said with his usual authority. But how did he know?

•

After the men left—Vita could hear Mr. Tillings and the coach driver arguing about the Boston man’s belongings as they carried him back out of the house—she watched her father pour himself a shot of the whiskey, drink it, and pour a second shot.

He probably wanted her to leave, too, but this was her chance. He tipped back the whiskey. He had a long thin nose with wide nostrils, which widened further into little round caves of distaste when he was annoyed.

They widened now. “I’ll just get on with my work, then,” he said, seeing her standing there.

When she and her brother Freddy were children, they spent many rainy afternoons in this office, examining Dar’s collections of curiosities: ancient bleeding bowls, antique instruments for pulling teeth, and a set of mandibles he’d gotten as a prize while studying medicine at Yale—a seagull, a porcupine, and a snake. Framed pictures of iridescent beetles hung on the dark-paneled walls like soldiers awaiting inspection.

Once, when they were here alone, Freddy bet Vita a penny that she wouldn’t touch the two-tailed lizard displayed in a jar of liquid; she won the penny easily. Sometimes even without Freddy, if Dar was out, Vita pulled books from the bookshelves to read about the uses of quinine, or how to re-set a dislodged shoulder.

But no one besides her father had been in this room for weeks now—he wouldn’t even let Gemma in to clean it. Apart from this morning, he hadn’t seen a patient in weeks. Vita half expected to find something horrible or secretive here, something he didn’t want to be seen. However except for the stacks of yellowing newspapers piled up on the floor and under the windows, the room seemed much the same. What struck Vita most was the smell, which was heavy and densely male: sweat and stale tobacco smoke and wool clothes that needed airing. She looked down at his set of mandibles and picked up the snake, a bone rubbed smooth as glass.

“And take that blanket with you as you go. Best to have Mrs. Oakum wash it.”

She put the snake mandible back down on the painted tray with the others, turning it slightly so that it faced the door.

“Dar,” she said, picking up the blanket. She didn’t look at him. “I’ve discovered something. Well, I’ve known it for a long time. Which is that I want to be a doctor. Like you.”

Copyright 2020 by Martha Conway

If you’d like to get word when THE ANATOMY OF DESIRE is available, please sign up here:

Upcoming Releases

The Anatomy of Desire: Sneak Peek

June 1865

Lark’s Eye, Massachusetts

Vita was sitting on the front stairs in a shaft of sunlight reading On Diseases Peculiar to Women when they carried the Boston man into her house. It was Tuesday, so her mother and sister had gone into town to visit Aunt Norbert. Vita was waiting for her father to emerge from his office, once a front parlor, which was directly across from the staircase. She knew he was in there although for the last thirty minutes—she squinted at the watch pinned upside down to the shoulder of her dress—she’d heard nothing, not even the shush of a newspaper page turning.

Her brother’s parakeet Sweetie was perched on her shoulder. “What does he do in there all day?” Vita asked her. Sweetie repositioned her claws and butted her pale feathery head against Vita’s ear—the triangular fossa. Triangular fossa, scapha, auricular lobule, Vita recited. Parts of the outer ear.

She was just about to give up her vigil when she heard the sound of carriage wheels on the gravel drive, and a man shouting:

“Dr. Tenney! Dr. Tenney!”

She stood up. The front door banged open, and two men came into the house carrying a third man by the armpits and ankles. Sweetie flew off Vita’s shoulder to the fixed safety of the newel post.

“Dr. Tenney!”

Maneuvering, the men knocked over the little oak table with its double-wick lamp. Now there was glass on the floor.

“Dar?” Vita called. Like her brother and sister, Vita called her father Dar and her mother Mitty—her older brother Freddy’s attempt at saying their names, Arthur and Marie, when he was a baby.

Her father opened his office door and stood in the doorway, unshaven and wearing the same gray waistcoat he’d been wearing for three weeks straight. For some reason he looked at Vita first.

“Stop shouting.”

Sherman Tillings, who owned the saddler and the public stable and had a wife named Thankful, was at the injured man’s head; Vita didn’t recognize the other man.

“We was just changing horses for the Boston coach,” Mr. Tillings explained. “He collapsed on the porch, didn’t say a word. Where can we set him?”

Her father directed them to the long sofa against the windows in his office, where the light was best.

“Not one word,” Mr. Tillings went on, lowering the man onto the green velvet upholstery. “A Boston man. You see where his forehead is swelling? Cracked the rail when he fell.”

The man’s face—closed eyes, open mouth—had a waxy tinge, like skin on hot milk. Was he breathing? Vita, who had seen many an injured man or woman brought into their house, watched his chest. She couldn’t see any movement.

“Shall I fetch a blanket?” she asked. It’s important to keep the extremities warm, her father always said. He was sitting on the stool next to the sofa, and he bent to put his ear against the Boston man’s mouth. Then he straightened up and lay two fingers against the man’s limp wrist.

“No pulse.”

He told Tillings to prop the fellow up as he opened a bottle of whiskey. Holding the bottle by the neck, he pushed back the man’s head and poured a glug down his throat. “To encourage the swallowing reflex.” But the man didn’t swallow. Two uneven streams ran down either side of his beard.

“Get a hot poker, set it against his head, that’ll shock him awake,” Tillings said.

“Or blow tobacco smoke into his mouth,” suggested the other man—the coach driver?—who was small and freckled with wiry red hair.

“Nonsense.” Her father began massaging the man’s chest. “But perhaps I can work up the heart.”

“Work it up?” Vita asked. The human heart, with its auricles and ventricles and valves, its precise oscillation, was, to her, a miracle of engineering. She had seen her father perform countless exceptional procedures —setting badly broken bones, draining pustulous head wounds, and once making an incision into a man’s bladder to extract a stone the size of a fig—but she had never seen him restart a stopped heart. Scientifically, it seemed impossible, but there was so much she didn’t know. She stepped closer.

“I thought you were getting a blanket,” her father said.

When she came back into the room they were pushing the man forward and back, bending him at the waist as though he were a lever. They stopped long enough for Vita to spread the dark green blanket over his legs. The man’s eyes were not altogether closed although he was clearly unseeing. He had a very round face with a cluster of white warts under one eye; whiskey drops glistened on his beard. She touched the top of his hand. It was still warm. Of course, she thought, it will take a while for the blood in the body to cool.

The three men began again to pull him up and shake him, set him down, pull him up. Meanwhile her father became angrier and angrier, as though the unlucky man was clinging to death just to vex him.

“Enough!” he said at last. “He’s clearly past saving.”

Mr. Tillings stepped back and took off his hat. By now the Boston man’s mouth was fully open, and his neck and shoulders were unnaturally still. There was no rise and fall to his chest. Nothing. For a moment, Vita could almost understand it: how the body, with its layered, exact systems and its rhythmic machinery, might, at any moment, halt absolutely. Here was proof. However the next moment the man, a stranger on her father’s green sofa, didn’t seem quite real.

“Rupture of the heart,” her father said with his usual authority. But how did he know?

•

After the men left—Vita could hear Mr. Tillings and the coach driver arguing about the Boston man’s belongings as they carried him back out of the house—she watched her father pour himself a shot of the whiskey, drink it, and pour a second shot.

He probably wanted her to leave, too, but this was her chance. He tipped back the whiskey. He had a long thin nose with wide nostrils, which widened further into little round caves of distaste when he was annoyed.

They widened now. “I’ll just get on with my work, then,” he said, seeing her standing there.

When she and her brother Freddy were children, they spent many rainy afternoons in this office, examining Dar’s collections of curiosities: ancient bleeding bowls, antique instruments for pulling teeth, and a set of mandibles he’d gotten as a prize while studying medicine at Yale—a seagull, a porcupine, and a snake. Framed pictures of iridescent beetles hung on the dark-paneled walls like soldiers awaiting inspection.

Once, when they were here alone, Freddy bet Vita a penny that she wouldn’t touch the two-tailed lizard displayed in a jar of liquid; she won the penny easily. Sometimes even without Freddy, if Dar was out, Vita pulled books from the bookshelves to read about the uses of quinine, or how to re-set a dislodged shoulder.

But no one besides her father had been in this room for weeks now—he wouldn’t even let Gemma in to clean it. Apart from this morning, he hadn’t seen a patient in weeks. Vita half expected to find something horrible or secretive here, something he didn’t want to be seen. However except for the stacks of yellowing newspapers piled up on the floor and under the windows, the room seemed much the same. What struck Vita most was the smell, which was heavy and densely male: sweat and stale tobacco smoke and wool clothes that needed airing. She looked down at his set of mandibles and picked up the snake, a bone rubbed smooth as glass.

“And take that blanket with you as you go. Best to have Mrs. Oakum wash it.”

She put the snake mandible back down on the painted tray with the others, turning it slightly so that it faced the door.

“Dar,” she said, picking up the blanket. She didn’t look at him. “I’ve discovered something. Well, I’ve known it for a long time. Which is that I want to be a doctor. Like you.”

Copyright 2020 by Martha Conway

If you’d like to get word when THE ANATOMY OF DESIRE is available, please sign up here:

Upcoming Releases

June 30, 2020

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

February 9, 2018

The Kindness of Readers

DRIVING TWO-AND-A-HALF hours to get to a Book Club meeting might not seem like everyone’s cup of tea, and it’s true that my car tires seemed to touch every highway in the Bay Area in order to get there.

DRIVING TWO-AND-A-HALF hours to get to a Book Club meeting might not seem like everyone’s cup of tea, and it’s true that my car tires seemed to touch every highway in the Bay Area in order to get there.

But greeted by enthusiastic readers and incredibly yummy food, I was grateful to have the opportunity to talk about—and listen to opinions on—my novel, The Underground River.

First, the food: a beautiful salad, sauteed mushrooms on toast (gluten-free crackers provided, too), succulent chicken niblets (almost like finger food, but so tasty!), and a Canadian-inspired dessert of Nanaimo bars (3 layers of cracker-crumb, custard, and chocolate—with coconut thrown in).

I’m always interested in the questions readers have. Was Hugo very upset over his sister’s death (a lively discussion on how this was handled in the story)? Who was the most despicable character? And—the first time I’ve been asked this—who wrote the jacket copy for the book?

We veered off to talk about Germany during World War II, what’s really great about Amsterdam, and rumors about secret office buildings maintained by Apple. As usual when I talk to Book Clubs, by the end of the evening I felt I’d been friends with these women for a long time!

So thank you, avid readers and book club members! To paraphrase Tennessee Williams, I’ve always relied on the kindness of readers.

To book a book club meeting with me in person or via skype, please email me! marthamconway [at] hotmail [dot] com.

September 20, 2017

The Boy Who Could Not Lie

I WASN’T LOOKING FOR a subject for a new novel. I was in the midst of re-writing a novel that I’d been working on for a few years, and the finish line was in sight. But one day—this was about a year before I began writing The Underground River—I had one of those moments, more oh:this! than ah-ha.

I was talking to a friend of mine, when she said in a very off-hand manner:

The Ohio River (Kentucky)

The Ohio River (Kentucky)“Well, you know,” she told me, “my son can’t lie.”

It was a startling moment, for me. I stopped listening (sorry, friend!) and thought about what she had said. It was true, I decided. I knew her son. He always went to great pains to tell the truth as accurately as possible.

Now that would be an interesting trait for a character, I thought. And thus my character May Bedloe was born.

How much trouble could a character who couldn’t lie, not even a white lie, get into? A lot, perhaps. That’s always good for drama. And what if that character not only had to lie, but break the law as well? Could they do it?

We all lie all the time. Little lies to spare feelings; big lies to try to get out of speeding tickets. My mother used to call her father the morning after we’d return from a trip to let him know we were home. “If he knew we were driving at night he’d worry, so I just let him think we drove back in the morning.”

When May Bedloe, the character who cannot lie, finds herself blackmailed into helping ferry slaves along the Underground Railroad, she is scared of punishment, yes (she could be fined at best and hung at worst, depending on who finds her and where), but she is also very, very uncomfortable. At one point, May thinks:

On the one hand I did not want to know too much, because

if anyone asked me anything, I was in danger of blurting out

whatever I knew. On the other hand, I did not like to

undertake any activity without specific directions. Step A,

step B. step C.

Many readers have asked me if May is “on the Spectrum,” in the parlance of our times. And the answer is yes. Having a sister with autism gave me some knowledge of what May might be like, although May also (since she’s the main character) has to change by the end of the story. She does not grow out of her fundamental traits, however; rather, she accommodates for them. An actor teaches her a trick for lying, and after one scene she realized she lied without even thinking about it: “That was fear, I suppose.”

In 1838, a person like May might just be called socially awkward. But she is more than that. She has a sense of humor, like my sister, and she is able to rise to the many challenges I threw at her as I was constructing the plot. When my friend talked about her son, I saw a boy who was trying to navigate the world as best he could with his own inner sense of right and wrong. Just like May.

And really, the same can be said of all of us.

Previous Posts in Writing The River series:

Steamboats and Slavery

A Victorian Partridge Family

Next up: Travels with my Father

The Underground River is available at Amazon | B&N | IndieBound | BAM | Powell’s

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Tell me when the next post is posted!

June 12, 2017

Writing The River: Steamboats and Slavery

ga('create', 'UA-55185287-1', 'auto');

ga('send', 'pageview');

PROBABLY LIKE EVERY STATE, OHIO can be very regional; the northerners stay in the north, and the southerners stay in the south. I grew up in the north, in Cleveland, which is separated from Canada only by Lake Erie; I didn’t set foot in Cincinnati (the southern tip) until I was an adult. As a child, we drove straight down to West Virginia without stopping when we went on summer vacation.

PROBABLY LIKE EVERY STATE, OHIO can be very regional; the northerners stay in the north, and the southerners stay in the south. I grew up in the north, in Cleveland, which is separated from Canada only by Lake Erie; I didn’t set foot in Cincinnati (the southern tip) until I was an adult. As a child, we drove straight down to West Virginia without stopping when we went on summer vacation.

But I was writing a novel that took place in Cincinnati and along the Ohio River, and visit it I must. It was a great trip.

First of all, there were statues of pigs everywhere. What could be better than that?

In my novel, I’d been writing about the pigs. Frances Trollope mentioned them in her book, Domestic Manners of the Americans, and I fell in love with the idea of pigs roaming around the streets, eating garbage and generally being nuisances:

“As I made my way across the street I tried to stay away

from the snuffling pigs running loose and making

every effort to bump up against me.” (from The Underground River)

Well, in the twenty-first century the pigs no longer roam the streets of Cincinnati, sadly, but their heritage lives on. You have to respect a city who honors their porcine past.

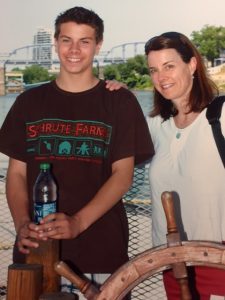

When I went on this research trip, I lured my teenage son to go along with me with promises of visiting friends in Louisville, Kentucky (also on the Ohio River). He was a good sport. We visited Harriet Beecher Stowe’s house. (“So you’re the little lady who started this great big war,” Abraham Lincoln is reputed to have said upon meeting her.)

There we learned that Cincinnati, like the country as a whole, was polarized around the issue of slavery: in 1836, two years before my novel takes place, there was a an anti-abolitionist riot led by working class white men who feared that if slaves were freed they would get their jobs. But many pastors preached against the evils of slavery, and one recounted a story of a young slave woman who fled Kentucky in the winter, when the Ohio River was frozen over. She barely made it across before the ice started cracking.

Harriet Beecher Stowe heard the story, and it became the germ for her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Another thing I wanted to do was ride on a steamboat. Okay, it sounds hoaky, but I really wanted to feel what it was like to be steaming down the river, like my character May did before her steamboat, the Moselle, blew up.

Another thing I wanted to do was ride on a steamboat. Okay, it sounds hoaky, but I really wanted to feel what it was like to be steaming down the river, like my character May did before her steamboat, the Moselle, blew up.

I’m happy to say that ours did not blow up.

On board the Belle of Cincinnati, we were treated to a running commentary by the captain over loudspeaker that combined both history and current urban planning. As we steamed west, my son and I played two-handed spades and ate sun chips and looked out at the beautifully landscaped riverbanks. When the captain invited all the children to come up and take a peek at the pilothouse, I went up, too — although John Henry felt he was really to old for that.

Unlike the other children there, I didn’t ask to try on his captain’s hat or pretend to steer the ship (although it was tempting). Instead, I asked the captain where the Moselle had blown up, (the “Fulton landing” is all I knew). He wasn’t sure, but he said he would try to find out. He became busy entertaining the real children, and so after taking in the beautiful view from the upper deck, I went back down to my seat. However, I was rewarded a few minutes later when the captain announced we were “at the spot where the steamship Moselle sank” over the loudspeaker.

Doesn’t look like much now, does it? The river is much more manicured than it was in the last century. But I got a little tingly feeling anyway. Still do.

Three hundred people were on board the Moselle, and less than half survived. It was a steamboat version of the Titanic—a captain who was too proud of his boat, and who pushed her too hard to make good time. From our seats on the Belle of Cincinnati, the shore did not seem so far away, but people had to swim nearly half a mile to get to shore. They were wearing those heavy Victorian costumes which, in a panic (and think of all those buttons), many didn’t bother to remove.

Besides walking across the iced-over Ohio River to freedom, or rowing across the water in a rowboat in the dead of night (without a light), some slaves stowed away on steamboats. They hid behind the boilers, and routinely caught and sent back “home,” where a whipping or worse awaited t hem. One of the hallmarks that our steamboat captain pointed out was the Second Baptist Church on the northern side of the river. If the light in the steeple was lit, he said, that was a signal that it was safe for slaves to cross over.

hem. One of the hallmarks that our steamboat captain pointed out was the Second Baptist Church on the northern side of the river. If the light in the steeple was lit, he said, that was a signal that it was safe for slaves to cross over.

Our steamboat turned around just past Fulton. The boat docked, stretched out the gangplank, and all of us twenty-first century tourists walked in a neat line back to shore.

Previous Post in Writing The River series:

A Victorian Partridge Family

Next up: The Boy Who Could Not Lie

The Underground River is available at Amazon | B&N | IndieBound | BAM | Powell’s

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save