Eugene Volokh's Blog

October 7, 2025

[Josh Blackman] Becoming Justice Barrett

Justice Barrett's new book is not a memoir. Though she sprinkles the book with some anecdotes about her family, Listening Law is quite guarded concerning how Barrett came to be where she is now. Her press appearances have likewise been fairly controlled, and she seems to repeat the same sets of pre-scripted answers. Yet, if you read between the lines, we can start to tie some threads together.

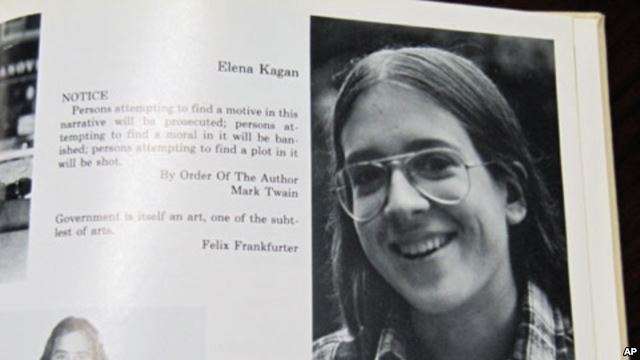

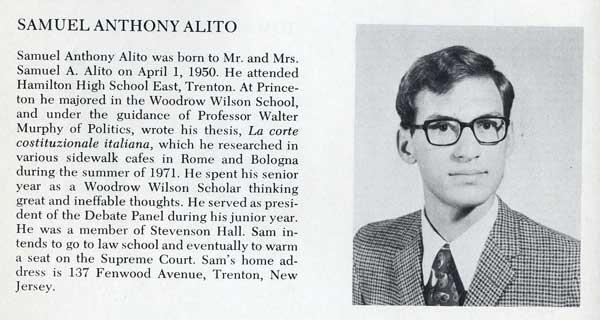

The first thread is that Justice Barrett did not aspire to be a judge before becoming a lawyer. Barrett's father was an attorney. But the Justice said in a recent press appearance that she wanted to be a teacher, like her mother. By contrast, some of Barrett's colleagues had their sights on the bench at a young age. In her high school yearbook, Elena Kagan wore a robe and held a gavel, and included a Felix Frankfurter quote. Samuel Alito's Princeton Yearbook said, "Sam intends to go to law school and eventually to warm a seat on the Supreme Court." Justice Jackson said that Judge Constance Baker Motley (with whom she shares a birthday) was a "North Star for me in my career." I don't get the impression that a young Amy Coney aspired for the bar or the bench, in the ways that some of her colleagues did.

Second, even after Barrett clerked for Justice Scalia, it still does not seem that she aspired to the bench, at least not right away. As a law professor, she did not do the sorts of things that an aspiring judge would do. I've written before how Barrett did not become a member of the Federalist Society until 2014. And prior to Justice Scalia's passing, she did not attend the Federalist Society National Convention, and did not speak at any FedSoc events.

I did not ever see Barrett in person until 2017, after she was already nominated to the Seventh Circuit. I was not alone. Ed Whelan recalls that he met Barrett for the first time at a memorial for Justice Scalia in November 2016, shortly before the election.

In the cafeteria before the ceremony, I sat down at a table with other former Scalia law clerks, and I met for the first time a Notre Dame law professor by the name of Amy Coney Barrett. Little could she or I have imagined that four years later she would become President Trump's third appointee to the Supreme Court and complete his process of transforming the Court into a body that would expand and entrench Scalia's legacy.

I consider Ed Whelan as one of the most plugged-in people in the conservative legal movement. He knows everyone, and remembers everything. How could it be that Whelan had never met her before? It appears that Barrett not only didn't attend any FedSoc events, but also did not attend the Scalia clerk reunions. "Little could" Whelan imagine that Barrett would make it to the Supreme Court. I suspect Professor Barrett in 2016 likewise could not have imagined at that point in time what would happen.

Were Barrett to write a memoir, I think this is the story she would have to tell. Most of her colleagues who made it to the Court took a series of deliberate and strategic actions throughout the course of their career to make it onto the bench, and later on the Supreme Court. At a minimum, they all served in government or some other public service. Barrett, other than clerking for two prominent judges, did none of these things. Indeed, she declined the various opportunities to put herself a position to be recognized as a potential judge--other than being a popular law professor at Notre Dame.

There is a third, and related thread. Justice Barrett by her own admission did not fully understand how she would be criticized as a Justice. For example, she told Jan Crawford:

"If I had imagined before I was on the Court, how I would react to knowing that I was being protested, that would have seemed like a big deal, like, 'oh, my gosh, I'm being protested,'" she says. "But now I have the ability to be like, 'Oh, okay, well, are the entrances blocked?' I just feel very businesslike about it. It doesn't matter to me. It doesn't disrupt my emotions."

She made similar comments in other venues--something to the effect of, I could have never imagined that X would happen. I've made the point many times that Professor Barrett was never subject to any sort of public scrutiny. Much was made of the "dogma" moment, but the full video tells a different story: A senile Senator asked a bizarre question, and Barrett just stared back blankly and didn't say a word. This was not exactly courage under fire.

Let me tie the three threads together. First, I find it refreshing that a young Amy Coney Barrett did not clamor to be a judge. Frankly, I find it a bit pretentious when young people say they want to become judges. I've rolled my eyes at many 1Ls who tell me they aspire for the bench.

Second, I also find it refreshing that Professor Barrett did not structure her career with an eye towards becoming a Supreme Court Justice. Indeed, I've written that anyone who wants to be a Supreme Court Justice should be immediately disqualified from the job. But there is also a problem with the inverse situation: someone who never planned to become a Supreme Court Justice yet is somehow elevated to that position.

That brings us to the third thread. Because Barrett was never tested before becoming a judge, there was no way to predict how she would handle pressure when she becomes a Justice. Justice Gorsuch knew first hand from his mother's experience how D.C. works. Justice Kavanaugh had been at the center of many major controversies in his tenure. But what about Barrett? President Trump, or at least those advising her, took a gamble on her.

There is a fourth, and related thread: Because Justice Barrett was not acculturated in the conservative legal movement, it was unknown who would prove influential to her. Now, Barrett has confirmed what I have long speculated: Justice Kagan has proven to be an influential colleague. Jan Crawford's piece relays:

Still, Barrett insists that kind of language doesn't affect her relationship with Jackson, and that she works to have relationships with all the other justices. She says she enjoys talking about the law with Justice Elena Kagan, also a former law professor who, like Barrett has a more formalistic approach to the law than the Court's two other liberals, even though it leads them to very different places.

In a recent interview, Bari Weiss of The Free Press asked Barrett to give one word for each of her colleagues. For Kagan, Barrett chose "analytical." That's a word she also used in our conversation to describe herself.

I have written a lot about the Kagan-Barrett bond, and speculated (to much criticism) that Kagan was using that bond to influence Barrett's opinions. There were a (small) number of cases where Kagan joined Barrett's separate writings, Vidal v. Elster in particular. But here we have Barrett acknowledging what I suspected. I don't think Barrett has singled out any of her other colleagues with similar praise. Certainly she hasn't said these sorts of things about the other Trump appointees.

Recall that Kagan went out of her way to make friends with Justice Scalia. She even went hunting with him! Query how often Kagan has gone hunting since Scalia's passing? I would wager the number is zero. Kagan, the former Dean, is very savvy, and knows how to play to people. This is precisely why Laurence Tribe urged President Obama to nominate Kagan over Judge Sotomayor: she would be able to persuade Justice Kennedy. Now, Kagan can persuade a Scalia disciple without even having to pick up a gun. She can naturally exude the "analytical" mode of a law professor.

Yet, I have wondered over the past few months whether this relationship is faltering a bit. In earlier emergency docket rulings, Justice Barrett ruled more consistently with Kagan. But more recent orders have Barrett (likely) joining the conservative majority. And Kagan has taken shots at a majority opinion Barrett (likely) joined. Let's see what happens on the merits docket this year.

The post Becoming Justice Barrett appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] "Counsel Relied upon Unvetted AI … to Defend His Use of Unvetted AI"

[Plus, "I don't know how you can vehemently deny that when the evidence is staring us all in the face. That denial is still very troubling to me."]

From Ader v. Ader, decided last week by N.Y. trial court judge Joel M. Cohen:

This case adds yet another unfortunate chapter to the story of artificial intelligence misuse in the legal profession. Here, Defendants' counsel not only included an AI-hallucinated citation and quotations in the summary judgment brief that led to the filing of this motion for sanctions, but also included multiple new AI-hallucinated citations and quotations in Defendants' brief opposing this motion. In other words, counsel relied upon unvetted AI—in his telling, via inadequately supervised colleagues—to defend his use of unvetted AI….

Plaintiff [had] identified inaccurate citations and quotations in Defendants' opposition brief that appeared to be "hallucinated" by an AI tool. After Plaintiff brought this issue to the Court's attention, Defendants submitted a surreply affirmation in which their counsel, without admitting or denying the use of AI, "acknowledge[d] that several passages were inadvertently enclosed in quotation" and "clarif[ied] that these passages were intended as paraphrases or summarized statements of the legal principles established in the cited authorities." Plaintiff then submitted a letter in rebuttal to the Surreply Affirmation, to which the Court invited Defendants to respond. Defendants did not respond.

As set forth in detail in the Rebuttal Letter and the papers in support of the instant motion, defense counsel's explanation of the citation and quotation errors as innocuous paraphrases of accurate legal principles does not hold water. Among other things, the purported "paraphrases" included bracketed terms to indicate departure from a quotation (not something one would expect to see in an intended paraphrase) and comments such as "citation omitted." Moreover, the cited cases often did not stand for the propositions quoted, were completely unrelated in subject matter, and in one instance did not exist at all.

Even as to the subset of fake quotations that happened to be arguably correct statements of law, "the court rejects the invitation to consider that actual authorities stand for the proposition that bogus authorities were offered to support." Use of fake citations and quotations that may generally support "real" statements of law is no less frivolous. Indeed, when a fake case is used to support an uncontroversial statement of law, opposing counsel and courts—which rely on the candor and veracity of counsel—in many instances would have no reason to doubt that the case exists. The proliferation of unvetted AI use thus creates the risk that a fake citation may make its way into a judicial decision, forcing courts to expend their limited time and resources to avoid such a result.

Unfortunately, the summary judgment briefing is not the end of the troubling conduct. Despite previously assuring the Court in defense counsel's Surreply Affirmation during the summary judgment briefing that "[e]very effort will be made to avoid the recurrence of such issues and to maintain the clarity and integrity of the submissions before this Court", Defendants' opposition to this sanctions motion contains another wave of fake citations and quotations. This time, Plaintiff has identified more than double the number of mis-cites, including four citations that do not exist, seven quotations that do not exist in the cited cases, and three that do not support the propositions for which they are offered. Separately, although not the subject of this motion, Plaintiff has also alerted the Court of still more fake citations in Defendants' opposition to Plaintiff's application seeking attorneys' fees in connection with the award of summary judgment.

In response to the overwhelming evidence skillfully marshalled by Plaintiff's counsel in the instant motion, Defendants "vehemently den[ied] the use of unvetted AI" and complained that "Plaintiff provides no affidavit, forensic analysis, or admission from Defendants confirming the use of generative AI" thus implicitly suggesting that AI was not used in preparing Defendants' summary judgment brief. At oral argument, the Court gave defense counsel the opportunity to set the record straight as to how exactly the many citation and quotation "errors" found their way into Defendants' briefs in this action. Defendants' counsel began with a prepared statement in which he acknowledged "some citation errors," but continued initially to maintain that "the cases are not fabricated at all."

Ultimately, however, upon questioning by the Court as to how a non-existent citation could possibly end up in the summary judgment briefing without the use of AI, counsel conceded that he "did use AI," contending that he "did verify and check the AI" but "must have missed" the false citation, which he conceded (for the first time) was an AI hallucination. With respect to incorrect quotations from actual cases, counsel acknowledged (also for the first time), under Court questioning, that they were not his own drafted "paraphrases" from the decisions but were instead AI-generated fake quotations that were not properly verified.

Turning to the inclusion of AI-generated false citations and quotations in Defendants' brief opposing the instant motion for sanctions, counsel began by indicating that he viewed the sanctions motion "as a minimal matter" relative to the other time-sensitive tasks on which he and his recently hired staff were working at the time. Ultimately, counsel conceded that a number of incorrect citations were AI-generated and not properly checked by lawyers he brought in to assist him. Indeed, he indicated that he identified at least one of the hallucinated citations during the drafting process and instructed his team to remove it from the brief, which they failed to do. In the end, it is undisputed that counsel signed a brief that contained the identified hallucination among several others.

Counsel expressed remorse for what occurred in this case, and at some points took responsibility (see e.g., id. at 15 ["[the false citation] was not removed. I take full responsibility for it being in this brief, and it had to be AI-generated. I believe it was"]; 17-18 ["I just want to explain my actions. And, obviously, some of this is sanctionable and extremely embarrassing and humiliating. I want to explain that I brought on additional staff because of the complexity of both of these matters. I was assured that all the quotations were 100 percent accurate. I went through the table of contents in each case to make sure they actually existed. I learned only after receiving the reply from opposing counsel that, in fact, there were inaccuracies"; 19 ["And, your Honor, when I say I told the staff, I take full responsibility. It's my staff, so I told myself to get rid of it and I did not get rid of it"]; 20-21 ["Your Honor, I am extremely upset that this could even happen. I don't really have an excuse. Here is what I could say. I literally checked to make sure all these cases existed. Then, you know, I brought in additional staff. And knowing it was for the sanctions, I said that this is the issue. We can't have this. Then they wrote the opposition with me. And like I said, I looked at the cases, looked at everything; so all the quotes as I'm looking at the brief—and I thought it was a well put together brief. So I looked at the quotes and was assured every single quote was in every single case, but I did not verify every single quote , , , . When I looked at—when I went back and asked them, because I looked at their [reply brief] last week preparing for this for the first time, and I asked them what happened? How is this even possible because, you know, when you read the opposition, I mean, it's demoralizing. It doesn't even seem like, you know, this is humanly possible"]).

On the other hand, counsel later muddled those statements of contrition by asserting: "I just want to clarify that I never said I didn't use AI. I said that I didn't use unvetted AI. I just want to be clear that I believe that I had checked everything. Number two, I did say that they were intended to paraphrase because in that rush of six days [to file the summary judgment brief] we made the decision that, hey, if this approximates this case, then let's remove the quotes. It's a paraphrase. Number three, retaliation was the reason for the immediate non-contrition. I thought, again, that the 800-lawyer firm [representing Plaintiff] was upset that I made a motion to have them relieved as counsel. I just wanted to point that out", to which the Court responded: "I'm not sure how that helps anything. The idea of unvetted AI, it sort [of] speaks for itself. If you are including citations that don't exist, there's only one explanation for that. It's that AI gave you cites and you didn't check them. That's the definition of unvetted AI. I don't know how you can vehemently deny that when the evidence is staring us all in the face. That denial is still very troubling to me."

{The troubling denial to which the Court referred is on page 12 of Defendants' brief in opposition to the instant sanctions motion and extends beyond the use of "unvetted" AI to suggest that AI was not used at all: "Plaintiff's speculation that Defendants' brief was generated using 'unvetted artificial intelligence ('AI') application' is purely speculative, unsupported by any evidence, and intended solely to cast Defendants' counsel in a negative light without factual basis. Defendants vehemently deny the use of unvetted AI. The errors, as explained, were human errors resulting from time constraints and the inadvertent misapplication of quotation marks to paraphrased content. Notably, Plaintiff provides no affidavit, forensic analysis, or admission from Defendants confirming the use of generative AI, nor do they show that any citation or quote was submitted with the knowledge that it was false. Absent such proof, accusations of bad faith or knowing deception fall flat under Rules of Professional Conduct Rule 3.3(a)(1)" (emphasis added).}

The court "award[s] Plaintiff her reasonable costs and attorney's fees incurred in connection with the sanctions motion, together with such fees attributable to addressing Defendants' unvetted AI citations and quotations in the summary judgment motion," and "directs Plaintiff's counsel to submit a copy of this decision and order to the Grievance Committee for the Appellate Division, First Department and the New Jersey Office of Attorney Ethics, copying Defendants' counsel and this Court on its transmittal letters. The Court will provide a copy of this decision and order to Judge Katz, who is presiding over a matrimonial matter in this Court in which Defendants' counsel is representing [the plaintiff]."

The post "Counsel Relied upon Unvetted AI … to Defend His Use of Unvetted AI" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] No Pseudonymity for Former Federal Employees Suing Over Mass Firings

["The fact that disclosure means Plaintiffs 'could be deemed litigious' or that future employers 'may treat Plaintiffs' association with this litigation as a red flag' is not sufficient to allege a substantial privacy interest."]

From Civil Servant 1 v. Office of Special Counsel, decided yesterday by Chief Judge James Boasberg (D.D.C.):

Plaintiffs Civil Servants 1–5 are former federal employees whose jobs were "terminated during their probationary periods as part of the Administration's mass firings in February 2025." They each filed a prohibited personnel practice (PPP) complaint with the Office of Special Counsel, only for the agency to summarily close each of their cases because they were probationary employees. Plaintiffs now bring this lawsuit alleging that OSC unlawfully closed thousands of probationary-employee complaints without considering their individual merits, undermining the workplace protections once afforded to probationary workers and violating the Administrative Procedure Act….

Generally, a complaint must identify the plaintiffs. That requirement reflects the "presumption in favor of disclosure [of litigants' identities], which stems from the 'general public interest in the openness of governmental processes,' and, more specifically, from the tradition of open judicial proceedings." A party moving to proceed pseudonymously thus "bears the weighty burden of both demonstrating a concrete need for such secrecy, and identifying the consequences that would likely befall it if forced to proceed in its own name." …

Plaintiffs have failed to meet their burden to show that their privacy interests outweigh the public's presumptive and substantial interest in learning their identities.

To begin, the Court finds that Plaintiffs' privacy interests do not implicate "a matter of a sensitive and highly personal nature." Plaintiffs contend that being "publicly linked to litigation" challenging the current administration "could have long[-]term consequences" for their careers. Certainly, when a plaintiff points to concrete career harms that would result from the disclosure of her identity, this factor favors pseudonymity. For instance, the Court granted pseudonymity for a doctor who was accused of misconduct that, if disclosed, would have prevented her from practicing. Doe v. Lieberman (D.D.C. 2020). [Note that not all judges agree on this point; some categorically conclude that pseudonymity can't be justified by a risk of reputational and professional harms, which is a commonplace risk in civil litigation. -EV]

But when identification poses only a speculative professional risk, this factor cuts against pseudonymity. Doe v. FDA (D.D.C. 2023); Doe v. DOJ (D.D.C. 2023). Plaintiffs' arguments, which identify neither concrete career consequences nor specific job prospects at risk of harm, do not rise to the occasion. The fact that disclosure means Plaintiffs "could be deemed litigious" or that future employers "may treat Plaintiffs' association with this litigation as a red flag" is not sufficient to allege a substantial privacy interest. The first factor therefore weighs against pseudonymity.

Next, the Court considers "whether identification poses a risk of retaliatory physical or mental harm." Plaintiffs assert that they could face harassment and retaliation "by members of the public or political actors" given the politically charged nature of their lawsuit. To support this contention, they cite instances of federal employees being terminated or put on administrative leave for expressing their opposition to the Administration.

But those examples all feature individuals who were federal employees at the time they opposed the Administration, rather than terminated employees, and the retaliation they faced happened primarily with regards to their employment. It is not clear what analogous harm can be extrapolated from those examples to Plaintiffs, who are not currently employed by the government and thus face no risk of being put on leave or fired.

The other consequences Plaintiffs discuss, such as private-sector firms being unwilling to hire someone "publicly known to have sued OSC and the Administration" are more clearly applicable, but as explained [above], this concern is undercut by the generalized nature of the career harm alleged…..

When plaintiffs sue the government, which way [this] cuts depends on the relief that they seek. If they request programmatic relief that would "alter the operation of public law both as applied to [them] and, by virtue of the legal arguments presented, to other parties going forward," then the "public interest" in their case "is intensified" and this factor cuts against pseudonymity. On the other hand, if plaintiffs seek only individualized relief—say, a judgment that their visas were improperly delayed or that they were unlawfully denied government benefits—then this factor favors pseudonymity. [Here too different judges take different views of the matter; some courts, for instance, conclude that when plaintiffs focus on what happened to them individually, that makes the credibility of their factual allegations and therefore their identities more relevant than if they were challenging a broad policy on its face. -EV]

Here, Plaintiffs seek vacatur of the Probationary Directive and an order that OSC reopen the thousands of probationary-employee complaints it closed, which amounts to programmatic relief. Any ruling in their favor would "alter the operation of public law both as applied to [them] and, by virtue of the legal arguments presented, to" all those whose complaints were disposed of by OSC pursuant to the Probationary Directive. And while programmatic relief need not be fatal to a motion for pseudonymity, this case does not present the "truly exceptional circumstances" that overcome the presumption against pseudonymity for programmatic relief. See Doe v. Hill (D.C. Cir. 2025) ("[T]hose who seek to alter public law by using the federal courts must, in all but truly exceptional cases, reveal their identity.")….

The post No Pseudonymity for Former Federal Employees Suing Over Mass Firings appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Possible Tort Liability for Harvard in Donated Cadaver Parts Theft Case

A short excerpt from yesterday's long Massachusetts high court decision in Weiss v. President & Fellows of Harvard College, written by Justice Scott Kafker:

In a macabre scheme spanning several years, Cedric Lodge, the person responsible for the care of cadavers at the Harvard Medical School morgue, dissected, stole, and sold parts of the bodies of individuals who donated their remains for research purposes….

Decedents' relatives sued Harvard, and the court concluded that the case could go forward, despite "the 'good faith' defense under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA …)":

As outlined in [a criminal] indictment, Lodge stole dissected portions of donated cadavers, including heads, brains, skin, bones, and other human remains, and transported them to his home in New Hampshire. From there, Lodge and his wife sold the stolen body parts to buyers, including the two alleged coconspirators, with whom they communicated via social media websites and cell phones.

Lodge also allowed third parties unauthorized access to the morgue in order to select body parts for purchase. For example, alleged coconspirator Katrina Maclean {the proprietor of "Kat's Creepy Creations"} agreed to meet Lodge at the Harvard morgue at 1 p.m. on Wednesday, October 28, 2020, to purchase two dissected faces for $600. Lodge also assisted Maclean with finding human skin to provide to a third party in exchange for his services tanning other human skin into leather. Coconspirator Joshua Taylor sent thirty-nine electronic payments, totaling over $37,000, to a PayPal account operated by Lodge's wife, including a $1,000 transaction with the memo "head number 7" and a $200 transaction with the memo "braiiiiiins."

While employed by Harvard during the period in which he was dissecting, removing, and selling donated body parts for profit, Lodge commuted to work in a car with a license plate that stated, "Grim-R." …

[Section] 18 (a) [of the UAGA] specifies that "[a] person [including a corporation] who acts in accordance with [the UAGA] … or who attempts in good faith to do so, shall not be liable." …

[W]e [have] defined "good faith" as "an honest belief, the absence of malice, or the absence of a design to defraud or to seek an unconscionable advantage over another." We further explained that "it may be possible that evidence of a peculiarly pervasive noncompliance [with the act] could warrant an inference that a defendant acted maliciously, possessed a design to defraud or to seek an unconscionable advantage over the plaintiffs, or acted out of something other than an honest belief" and thus failed to act in good faith. We conclude that the plaintiffs' factual allegations rise to this level and therefore warrant an inference that Harvard failed to act in good faith.

We reach this conclusion for several reasons. First, the facts alleged constitute "peculiarly pervasive noncompliance" with the act. Instead of the dignified treatment and disposal of human remains required by the act, the donors' remains were ghoulishly dismembered and sold for profit under the most horrifying of circumstances…. "[T]here is 'a special sensitivity' required in the processing and handling of a deceased human body" …. "There is a duty imposed by the universal feelings of mankind to be discharged by some one towards the dead; a duty, and we may also say a right, to protect from violation" …. This horrific and undignified treatment continued for years and involved numerous donors.

Although we focus our inquiry on Harvard's conduct, Lodge's misdeeds are relevant insofar as they demonstrate where Harvard failed to act in good faith in operating and overseeing the morgue. Despite the risk of harm being known to Harvard, as similar misconduct had previously occurred in a strikingly similar fashion in another medical school morgue [at UCLA], there were little to no controls in place to prevent this harm from occurring at Harvard. Instead, according to the allegations, an unsupervised Lodge was able to dismember the donated bodies; bring unauthorized people into the morgue to inspect and purchase body parts, including during working hours; and carry body parts out of the morgue for years.

Other red flags, such as his license plate describing himself as the "Grim-R[eaper]," which revealed an unprofessional insensitivity given his position in a medical school morgue, were also ignored or tolerated. Thus, Harvard's extraordinary failure to adequately supervise the morgue's operations and properly protect the donated remains in its care exemplifies the kind of "peculiarly pervasive noncompliance" we have said can demonstrate a lack of good faith…. We emphasize that "peculiarly pervasive noncompliance" is different in kind and not just degree from isolated acts of noncompliance, which alone are insufficient to defeat a good faith defense under the act….

Jeffrey N. Catalano, Kathryn E. Barnett, Jonathan D. Sweet, Leo V. Boyle & Chelsea Bishop represent plaintiffs.

The post Possible Tort Liability for Harvard in Donated Cadaver Parts Theft Case appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Hoover Fellow Program: Up-to-5-Year Paid In-Residence Position for Aspiring Academics (Including Aspiring Legal Academics)

The Hoover Institution at Stanford University, where I'm now a Senior Fellow, has long offered up-to-5-year paid in-residence positions (with no teaching obligations) in various fields.

This year, we'll also be considering people who are interested in becoming legal academics. We expect the selection process to be highly competitive: The position is unusually generous, compared to other fellowships, in salary ($165K-230K/year plus a $20K housing allowance), potential length, and lack of teaching obligations.

To be realistically eligible, applicants should have clerkships, top grades, published law review articles, and plans for new articles. It seems likely that most applicants will be from the Usual Suspect academic feeder law schools, but I'm a UCLA law graduate myself, so I'm certainly open to top people from other schools as well. We have no particular preferences for any particular fields within law: We'll gladly consider people who want to work in business law, constitutional law, international law, criminal law, immigration law, and all sorts of other topics.

The application deadline is Nov. 18, and the details are at https://www.hoover.org/hoover-fellows-program. Note that there would be no obligation for people to stay the full five years (and probably an expectation that they would stay no more). If someone gets a tenure-track law school teaching position two or three years into the fellowship—which tends to be the norm in the law market—we would be delighted to see them take it.

Here is the description from the link above; note that the title of the position is "Hoover Fellow," but that is different from other fellowships at Hoover (such as the long-term Senior Fellow position that Orin and I and Michael McConnell have, the one-year National Fellow position, and the various other fellowships):

Opportunities for Early-Career Scholars

The Hoover Institution at Stanford University seeks outstanding scholars for positions as a Hoover Fellow. The term of the appointment is five years, with the option to renew for one additional term. The position is located at the Hoover Institution, Stanford, CA.

During their fellowship, Hoover Fellows are expected to publish scholarly articles and books with implications for public policy and to contribute to the intellectual life of the Hoover Institution. This position carries no teaching responsibilities. The 12‑month base salary range is $165,000 to $230,000, plus a $20,000 annual housing allowance.

Candidates must have a Ph.D. or equivalent degree in a relevant field, such as economics, history, international relations, national security, political science, or public policy, and expect to complete that degree by September 1st, 2026. [A J.D. would count as an "equivalent degree" for people interested in law school teaching, because that is a norm of the legal academy, though of course law review articles will be expected as a rough analog to a dissertation. -EV]

Hoover Fellows are encouraged to engage with Stanford's broader research community in their respective fields. The Hoover Institution is a research center at Stanford University, located in the heart of Stanford's campus.

Please submit:

A cover letter or statement of interest that includes a description of academic background and experienceOne or more recent publications, working papers, or draft book chaptersA curriculum vitaeA statement about future research plans (two pages maximum)Three letters of recommendation that focus on the candidate's research and research potentialIf you have any questions, please contact hooverfellowship@stanford.edu. Please note that we only monitor this email address periodically.

Please submit completed applications online by November 18, 2025.

The post Hoover Fellow Program: Up-to-5-Year Paid In-Residence Position for Aspiring Academics (Including Aspiring Legal Academics) appeared first on Reason.com.

[Paul Cassell] Why the Supreme Court Should DIG Ellingburg v. U.S. Next Week

[The Court granted cert to review whether criminal restitution under the Mandatory Victim Restitution Act is "penal" in character. But the defendant was ordered to pay restitution under a different statute.]

Whoops! What happens if the Supreme Court grants certiorari to review a question presented about a particular statute—but the case does not involve that statute?! That's the situation in Ellingburg v. United States, a case that will be argued next week (Tuesday, October 14). The Court granted review of the question presented "[w]hether criminal restitution under the Mandatory Victims Restitution Act (MVRA) is penal for purposes of the Ex Post Facto Clause." But closely analyzing the proceedings below reveals that the petitioner/defendant was actually ordered to pay restitution not under that mandatory statute but under the discretionary regime of the Victim Witness Protection Act (VWPA). Accordingly, the Court should resolve the case by dismissing it as improvidently granted—or, colloquially, the Court should "DIG."

The Ellingburg case has been largely overlooked in previews of the Court's upcoming Term. But Ellingburg raises an important issue for the crime victims' rights movement: Whether restitution is "penal" in character because it punishes criminal defendants. If restitution is characterized as punishment rather than compensation, then the restrictions of the Ex Post Facto Clause apply to Congress and state legislatures as they craft restitution regimes. And perhaps other constitutional restrictions (such as the right to jury trial) attach as well.

Because of the importance of the issue to the movement, I've joined Allyson Ho, Bradley Hubbard, and other lawyers at Gibson Dunn in filing an amicus brief urging the Court to affirm the judgment below in Ellingburg and hold that restitution compensates victims rather than punishes defendants. Our amicus brief is filed on behalf of a crime victim's mother, Ms. Debra Ricketts-Holder, whose son was senselessly murdered. She received restitution for her son's funeral expenses under an (arguably) ex post facto restitution regime in Michigan. The Michigan Supreme Court affirmed, explaining that restitution statutes "provide a civil remedy for victims' injuries rather than to provide a criminal punishment for defendants." The defendant in that case has sought review in the U.S. Supreme Court—and his petition is apparently being held for resolution of the Ellingburg case.

So how should the Supreme Court answer the question presented in Ellingburg about whether restitution under the federal MVRA is penal in character? An answer to that question might potentially shed some light on whether other restitution awards are penal, such as the award in Ms. Ricketts-Holder's case. But, remarkably, Ellingburg was not actually sentenced under the MVRA.

Here are the facts: In 1995, Ellingburg, along with an accomplice, robbed a bank with a sawed-off shotgun, escaping with $15,134.50 in cash. He was caught. In August 1996, a jury convicted Ellingburg of bank robbery and of using a firearm during a crime of violence. The district judge sentenced Ellingburg to 322 months in prison and ordered him to pay $7,567.25 in restitution to the bank—half of the money and his accomplice had stolen. In ordering restitution, the district court applied the VWPA, as the MVRA had only recently been adopted (between Ellingburg's crime and sentencing).

Several decades later, in 2022, Ellingburg finished his term of imprisonment, having paid only a quarter of his restitution obligation. Ellingburg's probation officer continued to seek restitution with interest, citing MVRA provisions allowing an extended period of time to collect restitution and adding interest to the obligation.

Ellingburg, proceeding pro se, challenged the continued enforcement of his restitution obligation under the Constitution's federal Ex Post Facto Clause, U.S. Const., art. I, § 9, cl. 3. He argued that the MVRA's liability extension of his restitution liability from 2016 to 2042 retroactively increased his punishment because the MVRA did not exist when he robbed the bank back in 1995.

The district court denied Ellingburg's motion. After examining the sentencing documents, the district court concluded that "rather than applying the MVRA in ordering restitution, the sentencing court instead applied the Victim and Witness Protection Act of 1982." The district court also held that extending the period of liability for a preexisting restitution obligation did not qualify as an increase in punishment for purposes of the Ex Post Facto Clause.

Ellingburg then obtained counsel and appealed to the Eighth Circuit. The Eighth Circuit affirmed on the ground that, under circuit precedent, MVRA restitution is not criminal punishment and therefore is not subject to the Ex Post Facto Clause.

Ellingburg filed a petition for a writ of certiorari in the Supreme Court. His petition did not disclose that the sentencing court had imposed his restitution obligation under the VWPA. Instead, the petition presented the question whether "criminal restitution under the [MVRA] is penal," extensively discussed the MVRA, and highlighted conflicting appellate decisions about whether MVRA restitution qualifies as criminal punishment.

After the Supreme Court granted certiorari, the government joined Ellingburg on the same side of the question presented. To assure adversarial argument, the Court appointed a very capable amicus (John Bash of the Quinn Emanuel firm) to defend the Eighth Circuit's judgment.

Ellingburg and the Government then filed their opening briefs on the merits, spilling lots of ink supporting their position that restitution awarded under the Mandatory Victim Restitution Act was penal.

The Court-appointed amicus then filed his response, pointing out that this case does not involve restitution ordered under the MVRA. Thus, if the Court were to answer the question presented, it would be handing down an impermissible advisory opinion:

[Ellingburg] asks this Court to decide the nature of "criminal restitution under the

[MVRA]," but the sentencing court did not apply the MVRA in imposing restitution even though the statute was in effect at that time. In the proceedings below, the district court determined that "rather than applying the MVRA in ordering restitution, the sentencing court instead applied the Victim and Witness Protection Act of 1982." For support, the [district] court cited the (now-sealed) 1996 presentence investigation report and 1996 judgment stating that under "[the VWPA], restitution may be ordered in this case."

On appeal [to the Eighth Circuit], [Ellingburg's] opening brief agreed that "the district court judge appears to have sentenced petitioner under the VWPA, the statute in effect at the time of the offense conduct." [Ellingburg] enumerated "several indicators" supporting that conclusion and showing that he was in fact sentenced under the pre-MVRA version of the VWPA[] ….

[Ellingburg] was therefore never subject to "restitution under the [MVRA]," and the question presented is not implicated by this case.

Court-appointed Amicus Br. at 13-15 (some citations omitted).

The Court-appointed amicus is correct: Because petitioner Ellingburg was not ordered to pay restitution under the MVRA, his question presented about how to characterize restitution under the MVRA is not actually presented. The only appropriate result in the case, then, is a DIG. As the Supreme Court has explained in other cases, if it becomes apparent that the question presented is "without legal significance" to the "rights of the parties," Coffman v. Breeze Corp., 323 U.S. 316, 324 (1945), the case should be "dismissed as improvidently granted," Zacchini v. Scripps-Howard Broad. Co., 433 U.S. 562, 566 (1977).

A DIG does not rest on some sort of technicality. Instead, it relies on the commonsense observation that cases will be most accurately resolved when courts decide them against backdrop of a concrete factual dispute. Moreover, others who have an interest in the rule of law at stake in outcome can point to the underlying facts of a case as potential limits on any holding.

Here, for example, restitution awarded under the MVRA may significantly differ from restitution awarded under the VWPA. Under the VWPA, restitution is discretionary. In deciding whether to impose restitution, a sentencing court can consider "factors" beyond the victim's loss "as the court deems appropriate," such as the defendant's characteristics, the crime's circumstances, and other concerns. By contrast, under the MVRA's mandatory-restitution regime, a restitution award must cover all relevant victim losses without regard to any considerations other than (for non-violent offenses) impracticability or burden on the court.

In his reply, Ellingburg gamely maintains that the MVRA question somehow remains properly before the Court. Here's the most significant part of his claim:

The court of appeals here … took the view that no ex post facto analysis is necessary at all, on the theory that restitution under the MVRA is a civil penalty to which the Ex Post Facto Clause is categorically irrelevant. This Court has the ability, if it chooses, to review that rationale…. [W]hile restitution under [the VWPA] remains discretionary, it shares other features in common with mandatory restitution under [the MVRA]: each is imposed "when sentencing a defendant" as a "penalty" for the commission of a criminal "offense," compare 18 U.S.C. 3663A(a)(1), with 18 U.S.C. 3663(a)(1)(A); each is subject to the procedures set forth in 18 U.S.C. 3664, see 18 U.S.C. 3556; and each has the same enforcement mechanisms, 18 U.S.C. 3613(f).

Ellingburg Reply Br. at 5 (some citations omitted).

Ellingburg gives away the game in conceding that the MVRA only "shares … certain features" in common with the VWPA. That concession means that a Court ruling on restitution under the MVRA would be advisory as to the parties, because the other features of the VWPA might dictate a different result. A Court decision on the question presented would not decide further proceedings. Rather than render an advisory opinion, the Court should DIG the case.

Tomorrow, I'll discuss why, if the Court nonetheless chooses to consider whether MVRA restitution penal, it should answer the question "no." Restitution is compensation for victims, not punishment of defendants.

The post Why the Supreme Court Should DIG Ellingburg v. U.S. Next Week appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] The Heritage Guide to the Constitution: Essay Nos. 201–216

To continue my preview of The Heritage Guide to the Constitution, which will ship on October 14, here are the authors of essays 201–216.

Essay No. 201: The Fifteenth Amendment —Earl M. MaltzEssay No. 202: The Income Tax Amendment —Andy GrewalEssay No. 203: The Popular Election Of Senators Amendment —Michael R. DiminoEssay No. 204: The Senate Vacancies Amendment —Todd J. ZywickiEssay No. 205: The Prohibition Amendment —Paul J. LarkinEssay No. 206: The Suffrage Amendment —Judge Edith H. Jones & Jacob R. WeaverEssay No. 207: The Presidential Terms Amendment —Brian C. KaltEssay No. 208: The Repeal Of Prohibition Amendment —Paul J. LarkinEssay No. 209: The Presidential Term Limits Amendment —Judge Chad A. Readler & Andy NolanEssay No. 210: The District Of Columbia Electors Amendment —Derek T. MullerEssay No. 211: The Poll Taxes Amendment —Derek T. MullerEssay No. 212: The Presidential Succession Amendment—Sections 1 And 2 —John D. FeerickEssay No. 213: The Presidential Succession Amendment—Section 3 —John D. FeerickEssay No. 214: The Presidential Succession Amendment—Section 4 —John D. FeerickEssay No. 215: The Minimum Voting Age Amendment —Michael R. DiminoEssay No. 216: The Congressional Compensation Amendment —Giancarlo CanaparoThe post The Heritage Guide to the Constitution: Essay Nos. 201–216 appeared first on Reason.com.

[Josh Blackman] Today in Supreme Court History: October 7, 1982

10/7/1982: I.N.S. v. Chadha was argued.

The post Today in Supreme Court History: October 7, 1982 appeared first on Reason.com.

October 6, 2025

[Eugene Volokh] "Deloitte Issues Refund for Error-Ridden Australian Government Report That Used AI"

Financial Times (Ellesheva Kissin) reports:

The Big Four accountancy and consultancy firm will repay the final instalment of its government contract after conceding that some footnotes and references it contained were incorrect, Australia's Department of Employment and Workplace Relations said on Monday….

In late August the Australian Financial Review reported that the document contained multiple errors, including references and citations to non-existent reports by academics at the universities of Sydney and Lund in Sweden….

While Deloitte did not state that AI caused the mistakes in its original report, it admitted that the updated version corrected errors with citations, references, and one summary of legal proceedings….

The post "Deloitte Issues Refund for Error-Ridden Australian Government Report That Used AI" appeared first on Reason.com.

[Eugene Volokh] Free Speech Unmuted: From Brandenburg to Britain: Rethinking Free Speech in the Digital Era with Prof. Eric Heinze

[Jane and I speak with Eric Heinze (Queen Mary University of London) about how the digital age has transformed the meaning and limits of free expression, from Britain’s recent Lucy Connolly case—involving online incitement and hate speech—to the philosophical and legal contrasts between the American Brandenburg standard and the U.K.’s more interventionist approach.]

Prof. Heinze argues that democracies must rethink free speech in an era dominated by opaque, powerful platforms like Twitter and Facebook, where risk, harm, and accountability are far harder to define. He and Jane and I debate whether governments—or tech companies—should bear responsibility for regulating speech online, and what "freedom" really means when algorithms, not citizens, shape public discourse.

Our past episodes:

From Brandenburg to Britain: Rethinking Free Speech in the Digital Era with Eric HeinzeA Conversation with FIRE's Greg LukianoffFree Speech Unmuted: President Trump's Executive Order on Flag DesecrationFree Speech and DoxingThe Supreme Court Rules on Protecting Kids from Sexually Themed Speech OnlineFree Speech, Public School Students, and "There Are Only Two Genders"Can AI Companies Be Sued for What AI Says?Harvard vs. Trump: Free Speech and Government GrantsTrump's War on Big LawCan Non-Citizens Be Deported For Their Speech?Freedom of the Press, with Floyd AbramsFree Speech, Private Power, and Private EmployeesCourt Upholds TikTok Divestiture LawFree Speech in European (and Other) Democracies, with Prof. Jacob MchangamaProtests, Public Pressure Campaigns, Tort Law, and the First AmendmentMisinformation: Past, Present, and FutureI Know It When I See It: Free Speech and Obscenity LawsSpeech and ViolenceEmergency Podcast: The Supreme Court's Social Media CasesInternet Policy and Free Speech: A Conversation with Rep. Ro KhannaFree Speech, TikTok (and Bills of Attainder!), with Prof. Alan RozenshteinThe 1st Amendment on Campus with Berkeley Law Dean Erwin ChemerinskyFree Speech On CampusAI and Free SpeechFree Speech, Government Persuasion, and Government CoercionDeplatformed: The Supreme Court Hears Social Media Oral ArgumentsBook Bans – or Are They?The post Free Speech Unmuted: From Brandenburg to Britain: Rethinking Free Speech in the Digital Era with Prof. Eric Heinze appeared first on Reason.com.

Eugene Volokh's Blog

- Eugene Volokh's profile

- 7 followers