Ellen Jo Ljung's Blog

November 13, 2025

In Support of Teachers

I am sitting at a table at Sturdy Shelter Brewing in Batavia for my third book event in two weeks. It’s been nice to sell a few books, but the real value of each event has been meeting people and talking about education.

I particularly treasure conversations with those still in the classroom. I know: teaching is harder than it ever was in my time, but this country depends on these teachers to help prepare our youth for an evermore uncertain future. Each one of them has stories to tell.

At my reading last Sunday night, after I read the opening of my novel about a teacher in Texas who struggles with micromanagement and limits on the history she can include, a current teacher came up to me, eyes moist, to thank me. A history teacher herself, she struggled even here in liberal Illinois. That same night one of the facilitators, a teacher I know and respect, told me how much harder it had gotten. Mental health issues, absenteeism, a lack of cooperation and collaboration, helicopter parents, cheating and misuse of AI – the list of challenges seems pretty overwhelming.

I heard the same issues from teachers who stopped by my table at the local authors event at my public library last weekend. I read an entry from my favorite teacher’s blog where even he, one of the most reflective and committed teachers I know, wrote about burnout and discouragement.

I do indeed feel fortunate to have taught where and when I did. I faced plenty of challenges, but nothing like those crippling too many teachers today. My book events bring me face-to-face with those teachers, and I ache for them.

What does this mean for us as a country? We need to face these challenges head-on. We need to find ways to support teachers who are still deep in the trenches, doing their best to make a difference for their learners. Teachers and students need more than the lip service we freely offer them—they need us to work to change the culture, to provide support services, to make their workload manageable. The future holds further challenge, and our students are ill-prepared for it, our teachers too worn out. We simply can’t afford to wait.

You can make a difference. Learn about your school’s programs. Go to board meetings to support reasonable budgets. Consider volunteering. Ask what the schools need.

I’ve written often about our failure to meet the needs of our students and the cost to their learning. Now I’m asking my readers to think about how to support teachers who are trying to help those learners. If our teachers are too burned out to prepare our children for the future that awaits them, we’re in even deeper trouble than we thought. All of us have a stake here.

October 19, 2025

Team Teaching, A Proven Concept

Although some claim that team teaching in American public schools was a response to the Sputnik launch and the need to innovate in education, most credit William Alexander with popularizing the concept. At a 1963 conference at Cornell University, he presented a plan to establish “teams of three to five middle school teachers who would be in charge of team teaching content to large groups of pupils, ranging from 75 to 150.” He foresaw “several pedagogical and intellectual benefits, including the development of dynamic, interactive learning environments; creation of a model for facilitating the teaching of critical thinking within or across disciplines; and establishment of new research ventures and partnerships among faculty.“ Alexander acknowledged that teamed teachers would need to adapt their instructional strategies and course planning in order to collaborate successfully. (www.researchgate.net)

We now have research to support many benefits of team teaching, yet it largely disappeared in the 1970s. Larry Cuban writes, “as a buzzword, team teaching in K-12 classrooms flew like a shooting star across the educational sky in the 1960s and disappeared by the mid-1970s leaving little cosmic dust in its wake.” (larrycuban.wordpress.com)

Why did we let such a promising initiative wither? Many factors may have contributed to its decline, but I can think of four: it’s hard to do well because it requires a learning curve and professional development; other innovative initiatives may have displaced it, there are so many different approaches to teaming, and American education is a remarkably inert institution that resists change.

Why does it matter? Research proves that team teaching improves teacher retention and morale while helping teachers meet the ever-increasing diversity of needs of their students.

An Education Week article says that more than 1,100 schools across 18 states use team teaching models. For example, at a Mesa, Arizona, elementary school, two teachers led a highly interactive fifth grade lesson while maintaining order. The article posits that team teaching may boost retention “because the team models address some of the most difficult tensions that bedevil the teaching profession: It helps students connect to more adults, protects institutional memory in school buildings, and gives teachers timely support to improve their own craft.” When teachers are asked how to boost their morale, additional staff is second only to pay raises. That’s even more true as teachers overall become younger and less experienced and the gap between highest- and lowest-performing students continues to increase. They cite Arizona State University’s Next Education Workforce, and Opportunity Culture, a model designed by the North Carolina-based nonprofit Public Impact as an effective example. That program offers core-content teachers support staff, including counselors or tutors, and gives those teams more autonomy. Another example: the Ector County district in Odessa, Texas adopted Public Impact’s Opportunity Culture team-teaching model in 2019 to cope with and reduce staff vacancies. It’s working: “vacancies dropped from 350 in 2018-19 to less than 30 in 2024-25, even accounting for pandemic disruptions.” (https://edweek.org)

Research supports these efforts. Huriya Jabbar, an associate professor of education policy at the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California, found that “the most effective teaching teams quickly develop collective lesson plans, procedures, and student data. Some teams had well-organized systems for tracking calendars, lesson plans, and modifications they’d made over time.” He acknowledges the barriers to this approach: “For all their purported benefits, teaching teams remain comparatively rare in schools. Logistically, they are a heavy lift: They require extensive and ongoing training for teachers, outreach to parents and community groups, and sometimes even physical changes to classroom layouts.” (Ibid.)

Another Education Week article describes the June 2025 findings of researchers at Arizona State University and the Center on Reinventing Public Education on improved retention of teachers. “… after controlling for teacher and school characteristics, that the teamed teachers were half as likely to leave their schools as their non-teamed peers.” Teamed teachers felt more autonomy about their pedagogy and were able to be more creative. (https://edweek.org2)

Through surveys, the researchers found the New Education Workforce teachers were more likely than teachers in the district working solo to feel they had a say in education decisions at their school. Teamed teachers were also more likely than solo teachers to feel control over their schedules and able to take creative approaches to instruction. Teachers, both solo and in teams, who reported a stronger sense of autonomy in their teaching were more likely to remain in their schools. That autonomy matters. “The study showed that having clear team support and accountability, coupled with flexibility for teachers within those teams, were associated with the highest teacher retention.” (Ibid.)

A study, conducted by the Mary Lou Fulton College for Teaching and Learning Innovation at Arizona State University in collaboration with the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE), found multiple benefits to team teaching, including both improved teacher retention and greater teacher-driven decision-making. (https://www.datiak12.io)

Another initiative, The Next Education Workforce model (NEW) uses eight key elements in their team model: “1) teachers share a roster of students, (2) teachers share multiple learning spaces and move across these spaces throughout the day, (3) teachers have and use team planning time, (4) team members have different roles and responsibilities, (5) teachers adjust their schedule according to the needs of both teachers and students, (6) teachers group and regroup their students based on students’ needs and interests, (7) teachers use data to tailor learning to each student, and (8) teachers provide each student with rigorous learning opportunities.” They assert that this approach allows deeper and more student-centered learning, with improved student and teacher motivation and performance. (www.ascd.org)

NEW already works with 28 districts in a dozen states, where 241 teams of teachers use the ASU model, and in the next two years it will expand team teaching in dozens of new schools in California, Colorado, Michigan and North Dakota. (https://hechingerreport.org)

NEW also offers flexibility instead of a one-size-fits-all model. They support school communities in constructing the model that best fits their needs. (https://www.the74million.org)

I myself had two wonderful team-teaching opportunities that improved my own pedagogy and motivation. When the teacher next door and I both taught Junior Honors English, although our classes met at different times, we planned our lessons together, meeting every few Friday afternoons to do that. We also arranged for interactions among our students, like a joint student-run Medieval Festival to which the entire school was invited. Those experiences nurtured both of us as well as our students. I also had the privilege of actually sharing a classroom and team teaching with the chair of the Special Education department as we mainstreamed a number of kids into our joint American Literature class. Again, I learned so much from my partner, our lessons grew ever more creative, and we all were inspired. I so preferred these experiences to being a solo practitioner!

Why, then, if we know the benefits and believe they outweigh the obstacles and challenges, aren’t we doing this more? This investment would reap huge dividends if only we had the will to make it happen.

September 28, 2025

Reading Matters

American students can’t read well. That news, supported by data from the National Annual Assessment of Progress, should worry all of us. These test scores, the first since before the pandemic, show a stark decline that had begun even before the pandemic. We can’t blame Covid alone. Students are struggling, and their lack of adequate reading skills may limit their ability to function as adults in our society. This national snapshot cuts “across demographic divides of race, class and sex,” despite progress in the science or early reading teaching. (nytimes.com)

I am both saddened by these findings and concerned about their long-term impact on both students and on society as a whole. The New York Times article cited above acknowledges the likely role of technologies that have replaced reading time, including teens’ use of screen time for social media and videos. I believe the shift from paper to screens, from books to messaging, videos, and chats – that this paradigm shift is indeed one factor.

I do not believe it is the only factor. If we fail to recognize some of the additional forces at play, we will be even less successful at bringing students back to reading. We need to ask ourselves how the following patterns impact this issue:

How many kids grow up in a home with books, without adults who read to them?How many kids even see the adults in their lives reading?Given our tendency to overschedule kids with playdates, schooling, organized sports, etc., from a very early age, how many kids have the time and energy to indulge in reading for pleasure?Given the shortened attention spans of kids identified by research, how might we support their making the effort that reading requires?Does increased use of short texts in place of longer works in schools mean that students don’t build the habit of sustained reading?Does the pressure of short, single, right answers in our test-driven curriculum push for superficial focus?How much choice do we allow students in their reading, so that they find something compelling to push them to finish?Given that television shows and movies require less active engagement, what are we doing to show the pay-off of the greater effort that reading requires?Does the overscheduling of our older students, given their involvement in extracurricular activities and/or employment, preclude time for independent reading?Until we acknowledge the variety of factors at play and find a consensus on how to support reading, we are destined to have a less literate work force and citizenry. That matters. I believe that readers not only find a source of pleasure and relaxation, but they discover a window into other worlds, ways to learn about more than our immediate present, and ways to tackle the big questions like what it means to be a good citizen or a collaborative worker.

There are solutions already available and more that we can generate. In thirty years, Dolly Parton’s amazing Imagination Library program has given over 270 million free, age-appropriate books to families, providing homes without books a shot. Project Head Start, whose funding has been under attack by the current administration, provides reading experiences to preschoolers who may not have them at home. School can reconsider how they structure reading assignments and—perhaps even more important—how they ask students to engage with their reading. Meaningful discussions about big ideas in the text seem far more effective than worksheets and busywork. We can stop using multiple choice and short answer tests that belie the importance of the content of books, instead helping students make meaningful connections. We can consciously teach students to expand their attention span by building it up slowly, incrementally, and purposefully. Our sons went to Montessori schools and a progressive public school, all of which included a period of “silent sustained reading.” Our children grew to love that time and continued to choose to read at home. Schools can also lessen their focus on academic achievement as early as kindergarten and offer more time for less structured play and for free reading. And other educators and parents, wiser than I, can offer additional strategies to help our children read widely and well.

Today we picked up a book on hold at our local library, and we were behind a mom whose toddler was returning a pile of children’s books. I told her about the research and complimented her on raising a reader. He then looked up and said, “I can’t read myself yet. But I’m practicing.” She thanked us as they walked off hand in hand. Wouldn’t we wish that for every child?

Reading well develops critical thinking skills, grows vocabulary, and makes us better writers. It introduces us to wider worlds and other ways of being. It helps us figure out who we are and what we believe. Why would we settle for less?

September 4, 2025

No More Backsliding!

I was sad but not surprised to read the results of the National Science Foundation’s meta-analysis of gender-stereotyping of children. They conclude that “at age 6, children already believe that boys and men are better at computing and engineering; girls increasingly endorse this belief in older ages. These stereotypes therefore have ample time to affect children’s motivations and behaviors as children engage with these subjects in formal schooling and select diverging pathways in later grades.” (psycnet.apa.org)

Nearly thirty years ago I first encountered articles and studies about why girls were avoiding math and science classes at ever earlier ages. Although I’m an English teacher and writer, the rest of my family is in STEM fields, and I see how important they are and the opportunities they offer. Even though I ran three other extracurricular activities, I started a group called WIMS [Women in Math and Science]. We met after school every month to look at the research and plan activities. I connected them with women scientists at Fermilab, and they reached out to girls at the middle school and grade schools. I was hopeful.

I wasn’t entirely wrong. We did make progress.

But we’re slipping again. According to Northwest Evaluation Association research, although the disparity between middle school math and science scores disappeared in 2019, the gap has returned. One author posited that teachers may be reinforcing old stereotypes and/or the renewed focus on boys’ learning after they fell behind may affect girls. Whatever the reason, we’re losing ground here. (www.the74million.org)

Indianapolis schools have tackled this issue by creating Girls IN STEM Academy. Its mission: “Helping elementary-age girls’ science hopes take flight.” They’ve enrolled 65 girls but plan to grow to 300. The Girl Scouts are a partner. Purdue Polytechnic High School students will mentor the girls, seeking to create a pipeline that eventually boosts the female attendance there, as well as at colleges.

“With women making up just a third of the STEM workforce and about the same majoring in STEM fields in college, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and American Association of University Women, experts see a need to start encouraging girls early in a STEM focus.” The article claims that there are only three other girls elementary schools with a dedicated STEM focus — Innova Girls Academy in New York, Rise STEM Academy for Girls in Kentucky and Solar Preparatory School for Girls in Texas. (indianacapitalchronicle.com)

Girls make up nearly half the population of school-age children, and our country cannot afford to discard their talents. STEM careers are highly desirable, and girls should be encouraged to seek them along with boys. Early support of STEM makes a difference. “Researchers have found that high-quality academic preparation and exposure to STEM is a key influence in high schoolers’ chances of landing a STEM career.” (www.the74million.org2)

It’s time for change.

August 13, 2025

Texas Again and Again!

I keep wanting to tackle other topics in this blog, but the Texan culture warriors just won’t take a break, so I won’t either.

Despite the assertions of too many, the United States is not and has never been a Christian country. Our founding fathers, particularly Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, advocated for a separation of church and state to protect religious freedom and prevent government overreach into religious affairs. They believed that the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion”) and Free Exercise Clause (“or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”) created a “wall of separation” between government and religious institutions. The 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause incorporates the First Amendment’s protections, including the Establishment Clause, to the states, ensuring that state governments cannot infringe upon religious freedom.

Yet Texas continues to push Christianity in schools. In 2021 Texas passed legislation requiring schools to display “In God We Trust” signs as long as they are donated by a private foundation. Last May Governor Abbott signed a bill requiring schools to post the Ten Commandments even though last June a Federal Court found a similar bill from Louisiana unconstitutional. And this session lawmakers are even pushing bills to allow a religious study or prayer period in schools. (texastribune.org)

All of this would be bad enough, but last November, Texas adopted Bluebonnet, a bible-infused curriculum, making it, “the first state to introduce Bible lessons in schools in this manner, according to Matthew Patrick Shaw, an assistant professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt University.” Critics maintain that even with recent revisions, the lessons remain biased toward Christianity, are sometimes misleading, and teach complex topics better suited for older children. Others warn that the materials overstep parents’ rights to make decisions about the role of religion in their kids’ lives. (abc7ny.com)

Texas won’t even reveal the authorship of the bill or its cost, claiming that the work falls under a disaster declaration that the Governor used to speed up the delivery of supplies during the pandemic. This clearly intentional lack of transparency and this rationalization have not satisfied some state Board of Education members, who say the curriculum borders on proselytizing and promotes a distinctly evangelical view of American history. The curriculum extends its Christian focus and is not always age-appropriate or accurate. For example, “A teacher’s guide for a third-grade lesson on ancient Rome, for example, devotes eight pages to the life and ministry of Jesus — presenting many of the events as historical facts, scholars say. But the Islamic prophet Muhammad isn’t named anywhere. A kindergarten lesson on “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” draws parallels to Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. And an art appreciation lesson walks 5-year-olds through the creation story from the Book of Genesis.” (www.the74million.org)

Other concerns have been identified by Mark Chancey, a religious studies professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, who said he submitted over 80 comments to the state. He points out distortions in the story of Queen Esther, and his analysis showed that the authors relied overwhelmingly on a 1978 version of the Bible that he called a “distinctively evangelical translation” that was “made by evangelical scholars for evangelical Christians.” (Ibid.)

And the bill is suspiciously similar to others produced by Christian right bill mills in a national push to provide model legislation to help states embed Christianity in their schools. (www.the74million.org2)

Proponents like Jonathan Covey, director of policy for Texas Values, argue that the First Amendment “does not demand strict governmental neutrality towards religion…There is nothing the U.S. Supreme Court has laid down requiring equal time or equal treatment among religious sects.” (www.the74million.org3) https://www.the74million.org/article/in-close-vote-texas-approves-reading-program-laden-with-bible-lessons/?utm_source=The+74+Million+Newsletter&utm_campaign=fb1300fd77-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_07_27_07_47_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_077b986842-fb1300fd77-177359832 The courts have often disagreed, so lawsuits will continue to be filed.

There is some good news. “Texas won’t force districts to use the materials, but is offering up to $60 per student — a total of $540 million — to any that adopt the program. That’s an incentive many are unlikely to turn down at a time school systems are projecting deficits and calling for tax increases to offset them.” (www.the74million.org) Indeed, many of the largest districts in Texas are choosing not to adopt this reading program or to use only parts of it. Texas has 1200 public schools and about 600 charters, but between May and late July, only 144 districts and charters had ordered the materials, and only one of the 20 largest districts intends to use them. (www.the74million.org4)

Yet the Texas Education Agency continues to push the program. It insists that free state support will help students perform well on tests, and it made the materials available months before other options. State lawmakers authorized contracts with businesses to “promote, market and advertise” Bluebonnet and appropriated $243 million to districts to help with implementation costs, like coaching for teachers. (Ibid.)

So: a reading program infused with Christianity that is biased, non-inclusive, inaccurate, not nuanced… what could go wrong? The hypocrisy of leaders and parents who insist that parents should decide how to raise their children in all arenas, including religion, while they embed a specific religion into state curriculum, is staggering. And Texas is not alone in this pursuit. Our constitution and basic rights are being assailed, and we need more public reaction to stop it.

July 22, 2025

A Tribute and an Answer

Screenshot

ScreenshotMy last blog explored why teachers continue to teach despite the challenges and frustrations that too often confront them. A recent loss reminded me of the answer to “why teach?”.

I grew up in part of a New York suburb with a K-8 grade school, Quaker Ridge, though the rest of the community had elementary schools and a shared junior high. I didn’t realize until much later in life how special that experience was, how tight the bonds we formed had been. When I went back to my high school’s 50th reunion, we also held a Quaker Ridge reunion, the highlight of the reunion weekend for me. I loved reconnecting with childhood friends, but some of the magic happened because a teacher beloved by all of us joined us. Nat Sloan was our seventh and eighth grade science teacher, and his passion for both us and for his subject mattered to all of us.

Nat had a particular impact on me because he required us to choose a book from his amply stocked bookshelf, read it, and report back to the class. In seventh grade I chose Patterns of Culture by Ruth Benedict. A well-respected anthropologist, Benedict explained her belief in cultural relativism, which emphasizes understanding behaviors within their cultural contexts rather than through the lens of one’s own cultural biases. She then went on to demonstrate her approach through an in-depth examination of three disparate cultures. Spellbound, I recognized that going steady and girls’ wearing a boys’ ID bracelet were patterns from my culture, not universal patterns. She opened my eyes to a world wider than I’d considered and drove my desire to travel to other cultures and to study anthropology in college.

Nat gave me a different lens to explore the world, and that mattered. It’s no surprise that he was one of two teachers we invited to our wedding. His presence, along with Garnet Almes, an amazing math teacher, mattered. They were the two teachers who did the most to shape my own commitment to teaching, and I was honored to stay connected with both of them. We visited Ms. Almes in Florida before she died, and I maintained email correspondence with Nat after the reunion. He had become a sculptor and we are glass artists, so we had a lot to write about and pictures to share!

So what does this self-indulgent trip down memory lane have to do with why we teach? My classmate, who is now the mayor of our hometown, emailed us when Nat died last month after reaching 100. The outpouring of love and memories from all of us created a beautiful tribute to the man and his impact on his students. And we were only one class out of many years of classes, no doubt similarly affected by him.

Nat Sloan mattered. Good teaching matters. He and other really impactful teachers live on in the memories of the students they taught. How could anyone ask for a richer life than that?

July 2, 2025

Remembering Why We Teach

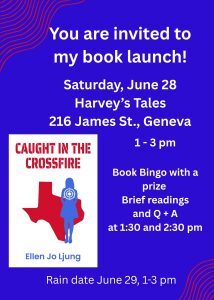

Last Saturday I had the privilege of launching my new novel at our favorite local bookstore, Harvey’s Tales, in Geneva, Illinois. My first foray into fiction, Caught in the Crossfire evolved from the research I’ve done for this blog. I’ve written often about the pressures teachers are under, the micromanagement and censorship they face in many states. As my frustration continued to rise, a mythical teacher named Claire Peters emerged in my dreams, in the shower, on long car rides, and she urged me to tell her story. I did, and the writing of it became therapeutic. I had no sense of whether anyone else would care. To my surprise, teachers I’d never met, teachers who saw local articles and publicity about the upcoming launch, joined us on Saturday. Although the heat was gruesome, they – and others – stuck it out and talked about the book.

I loved the conversation about our passion for teaching, our concerns for current students and teachers and the struggles they face, the importance of teaching… I could go on! We acknowledged, though, the new challenges that teachers and students, along with parents and administrators, face.

I really loved being a teacher until I didn’t. At the end of my public school career, changes in my school and my role didn’t appeal to me, and I was wise enough to resign and lucky enough to be able to resign. But I continued in education in multiple ways because it is who I am at the very core. These women agreed. We’re all relieved not to be dealing with the current challenges, and those very challenges are far worse in states like Texas and Florida. Writing about a mythical teacher’s struggles in Texas proved cathartic for me, and I hope this story sparks lots of conversation among educators and others alike.

I find solace in Rachel Jorgenson’s August 2023 Edutopia post, “Why I Keep Teaching.” (edutopia.org) She acknowledges that the “teaching profession has rarely felt more bleak” yet insists that the work of teachers matters. She lists four reasons:

Every time I show up for work, a student might change my life for the better.My work has invisible ripple effectsMy head and my heart are engaged every dayMy work is an investment in a brighter futureHer conclusion expresses my views on teaching better than I ever could: “Our work has an impact, whether we see it or not. We may be planting seeds that don’t come to fruition until decades later. Showing up for students with love, empathy, kindness, and selflessness makes a tremendous impact, whether or not we know it.”

I’ve been one of the lucky ones. I’ve had students reach out to me years later, showing me I mattered to them.

I’ve often likened teaching to the title of a favorite children’s book, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. When it’s going well, there’s nothing like it: seeing a student make a discovery and develop understanding is a gift to both the student and the teacher, but sometimes we all have “terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day[s].” Rachel Jorgensen and the teachers I met at my book launch remind me that we must make the good days count and make the others worth it.

Note: Caught in the Crossfire is available from Harvey’s Tales (https://harveystales.com/) and directly from the author or Amazon. In mid-July it will be available at bookstores in six states, including Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon, and Barnes & Noble in New York City and Salt Lake City.

June 19, 2025

Caught in the Crossfire

The research I do for this blog has driven my concern about teachers being “handcuffed” by micromanagement and censorship in far too many states. Texas and Florida may lead this unhelpful pack, and my growing frustration sought an outlet.

Until now, my writing has been non-fiction, but nearly two years ago, a creative and talented teacher named Claire Peters started pestering me in my dreams, in the shower, on long car rides. My mythical colleague had a story to tell and hounded me to tell it. Reluctantly, I let myself be drawn in. Claire’s story led me to research schools, communities, and laws in Texas, to merge real places and issues into this telling. Although this novel is fiction, it’s grounded in what happened to teachers in Texas during the 2022-2023 school year, interference and micromanagement that continue to this day. The realities drew me in, and I hope they draw my readers in, too.

I didn’t know the ending when I began. I just let Claire lead me, and this is where we landed.

In hindsight, a conversation with a fellow writer reminded me that I, too, had experienced this kind of micromanagement in my very first teaching job, an experience so challenging that it nearly ended my teaching career at the start. You can read all about it my teaching memoir, Tales Told Out of School: Lessons Learned by the Teacher.

I was lucky. I was pregnant with our second child when that school year ended, and we were committed to my being home with our children once my husband finished graduate school. Taking care of our sons gave me a five-year respite which created the space for me to try teaching again. Decades later, I’m grateful for that second chance. But that first experience clearly pushed Claire’s story for me.

I give you Claire Peters. She isn’t me, but I think we’d be friends if she were human. And I’m grateful for her pushing me to tell this story. I hope you found her as compelling as I did.

And I hope her story generates conversations about what it means to be a good teacher in a system that discourages good teaching. I believe that the best teachers coach learners to ask open-ended questions and then seek answers for them. I believe that the point of studying the humanities is to better understand people and lead to better decisions in the future. I believe that history teachers help learners discover the past so that we are not condemned to repeat its mistakes. How, then, can a teacher caught in the cultural crossfire coach learners effectively? How can that teacher encourage questions and independent thought when history is whitewashed and connections are discouraged?

I don’t have answers, but I will always pose questions. We need to protect independent thought, to raise independent thinkers. We cannot do that with our hands tied.

Note: My book is available through Harvey’s Tales in Geneva, Illinois [https://harveystales.com/] and on Amazon in paperback and Kindle.

June 11, 2025

Here We Go Again!

Screenshot

ScreenshotMy relief about last month’s Supreme Court’s decision not to allow Oklahoma to open the nation’s first publicly funded Catholic charter school may have been premature. I knew the decision was narrow and ended in a tie, with Justice Barrett recusing herself, but at least the court “affirmed last year’s Oklahoma Supreme Court decision that the concept of a publicly funded Catholic charter school is unconstitutional.” (oklahomavoice.com)

The first amendment to our Constitution unequivocally states, “”Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The Court’s tie ruling, however, suggests some openness to dismantling that separation. Our current administration insists that we are a Christian country despite the clarity of the amendment’s statement.

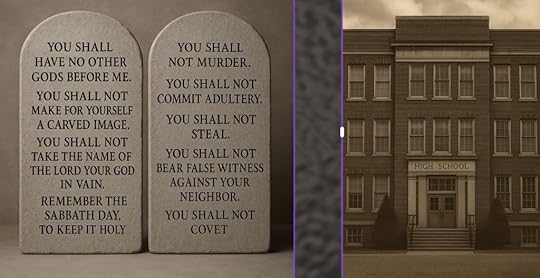

In 1980 in Stone v. Graham, the Court found that Kentucky’s requirement to post the Ten Commandments in schools “violated the Establishment Clause of the Constitution. The Court found that the requirement that the Ten Commandments be posted ‘had no secular legislative purpose’ and was ‘plainly religious in nature.’ The Court noted that the Commandments did not confine themselves to arguably secular matters (such as murder, stealing, etc.), but rather concerned matters such as the worship of God and the observance of the Sabbath Day.” (www.oyez.org )

Despite precedents like that, a year ago, Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry signed a bill into law mandating that the Ten Commandments be posted in every classroom in the state and said, ““I can’t wait to be sued.” Last November, U.S. District Judge John deGravelles that “the law is ‘facially unconstitutional’ and ‘in all applications,’ barring Louisiana from enforcing it and adopting rules around it that obligate all public K-12 schools and colleges to exhibit posters of the Ten Commandments.” (nbcnews.com)

When this case reaches the Supreme Court, the outcome should be a no-brainer. Constitutional law scholar Sanford Levinson warns, however, that the current Court’s willingness to dispense with past precedents may lead to a different decision. (hls.harvard.edu )

And Louisiana is not alone. This fall every school in Texas must post a copy of the Ten Commandments, and they will not be permitted to post any alternatives: “the bill requires every classroom to visibly display a poster sized at least 16 by 20 inches. The poster can’t include any text other than the language laid out in the bill, and no other similar posters may be displayed.” (texastribune.com)

Other states have climbed on this bandwagon. In 2024, Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs vetoed a state senate bill that would have permitted posting the Ten Commandments in schools. Last summer Utah passed a bill “adding the Ten Commandments along with the Magna Carta to a list of approved historical documents and principles allowed to be studied in public schools.” The final watered-down version that passed removed the requirement and made the display optional. (abc4news.com) In Oklahoma, House Bill 1006, which failed last year, has been revived and would require a poster or a framed copy of the Ten Commandments to be posted in a conspicuous place in every public school classroom in Oklahoma, the same state where Education Superintendent Ryan Walters “ordered public schools to keep a copy of the Bible in every classroom and incorporate the Christian text into lesson plans. Several district leaders have said they won’t comply, and a lawsuit is challenging the order.” (oklahomavoice.com)

The Supreme Court has weakened the doctrine of separation of church and state before. In 2005 in Van Orden v. Perry, a lawsuit about a monolith displaying the Ten Commandments being placed at the Texas state capitol after being donated by a private group, the Court determined that, “The Establishment Clause does not prohibit per se all forms of government action that may have religious content or a religious message.” (supremejustia.com) In the 2019 Kennedy v. Bremerton case, the Court determined that the football coach had the right to pray on the high school football field after a game, where he could be joined by players. (www.law.cornell.edu)

I fear that the current US Supreme Court will continue to make decisions that erode the separation of church and state. Mandated posting of the Ten Commandments excludes other religions along with atheists and agnostics. It has no part in our public square. Our founding fathers were not anti-religion, but they sought relief from the enforcement of any single religion. I believe in an inclusive and welcoming space for all learners. Religious instruction has been a private matter and must remain so.

May 20, 2025

Penny Wise, Pound Foolish

My heart lies with Project Head Start. As a senior in high school, already committed to teaching, I was lucky enough to volunteer in one of the first Head Start programs in New York. I saw firsthand fine teaching and coaching. I met children who grew up without books and reading in their homes, who became a rapt audience. I valued the relationship-building the paid teachers facilitated and felt hopeful for the future of the kids enrolled. That hopefulness was confirmed when I researched the impact of the program for one of my education classes in college.

Knowing that research might now be updated, I just did another search. Overall, the program remains effective: children have significantly better social-emotional, language, and cognitive development and are better prepared for kindergarten. (Love et al., 2002) These children are less likely to end up in foster care (sciencedirect.com), more likely to have better health outcomes (Lee et al., 2013; Ludwig and Miller, 2007), more likely to graduate high school (Bauer and Schanzenbach, 2016) and go to at least one year of college and less likely to be unemployed (Deming, 2009). The children of Head Start graduates are significantly more likely to finish high school and enroll in college and they are significantly less likely to become teen parents or to be involved in the criminal justice system. (Barr and Gibbs, 2017)

A systematic meta-study shows that “studies have found persistent favorable effects of Head Start on academic achievement scores at older ages; on educational attainment, including high school graduation and college enrollment; on other lifecourse outcomes such as criminal behavior, teen pregnancy, and aspects of health, albeit with some differences in the magnitude of the impacts across subgroups defined by gender or race-ethnicity.” (www.rand.org)

I find the plans of the current administration to defund this valuable program not only appalling but also bewildering. Head Start, which serves more than half a million of the country’s neediest children, is run by public and private schools but dependent on the federal government for its funding. Current programs have received $1 billion less already, “slow-walking” money approved by Congress. That’s almost a third of their funding, and its absence caused some programs to close. (apnews.com) RFK Jr. claims he wants to preserve funding for this fiscal year (chicagotribune.com), but last month the news leaked that the Trump administration would propose eliminating Project Head Start in 2026. (usatoday.com) Indeed, in early April the federal government closed five regional Head Start offices, including the Chicago regional office. (chicagotribune.com) The ACLU has filed a lawsuit asking the federal court to stop the administration from stripping funding for Head Start and closing program offices. (chicagotribune.com 2)

While the ultimate outcome is unclear, programs suffer from the uncertainty. I believe in Project Head Start because it serves children who need support. I am convinced that Project Head Start’s investment in our neediest children offers a good return on investment. For those who don’t value its work as a moral issue, the economics should convince them. Cutting this program might save money initially but will cost far more in the long run. The human cost is incalculable. I am heartbroken that the current administration continues to weaponize funding instead of making wise decisions about what’s worth doing. Too many of our children and—ultimately—their ability to be self-sufficient adults with agency are at stake.