Duncan Barrett's Blog

November 2, 2021

Farewell to Glad

Last month, we were finally able to say a proper goodbye to Gladys, one of our original Sugar Girls as well as an irreplaceable friend. Since the pandemic meant it wasn’t possible to have a public funeral when Glad died in March, her family had decided to wait until now to organise a get-together to celebrate her life, and to scatter her ashes.

We gathered at the Golden Fleece, on the edge of Wanstead Flats, where Glad and her husband John had courted so many decades earlier. Then in small groups we took the little bags of ashes that her family had carefully divided up and went to scatter them on the grass. It was an emotional farewell for everyone.

With the family’s permission, we also took an extra couple of bags to scatter at the site of the Plaistow Wharf factory. Knowing that the factory, too, was a major part of Gladys’ life – not least because of the life-long friends she made within its walls – it seemed right that part of her should remain there.

April 6, 2021

Raise a glass to Gladys

Gladys’s family have asked us to pass on the message that she is being cremated at 3pm today. Please join us in raising a glass to her then, and remembering one of the most remarkable of Sugar Girls. She will be much missed!

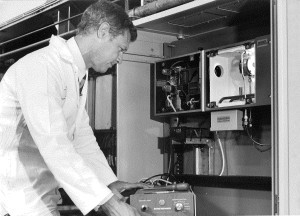

Gladys on a tour of her old factory in 2012

March 22, 2021

Gladys

[See image gallery at www.thesugargirls.com] It is with great sadness that we announce the death of our friend and first ever Sugar Girl, Gladys Hudgell, who has passed away at the age of 88.

Gladys was a true one-off, outspoken, irreverent and irrepressible. Her many pranks and run-ins with manageress Flo Smith were legendary at Plaistow Wharf, and the friendships she made at the factory lasted her whole life.

Gladys always said she wanted to be famous, and with her starring role in The Sugar Girls she got a taste of fame, storming Woman’s Hour, Midweek and the Robert Elms Show with her friend Eva, as well as featuring in the national press.

In recent years, following a heart attack and a hip replacement, Gladys was unable to get out and about as much, and had talked about wanting to go. She passed away peacefully in her sleep early on Saturday morning, while staying at her son’s house.

Glad, you are unforgettable. We will love and remember you always.

August 23, 2019

A half-century of service

While our main focus is on the women who worked for Tate & Lyle, we are always happy to hear stories from male workers – past and present – as well. Last year, at an event at the Houses of Parliament to celebrate 140 years of cane refining at the Thames Refinery in Silvertown, we met Alan Mead, who has the distinction of having worked for the company for more than half a century.

Alan started worked at Thames Refinery on 7 September 1964, on a three-year apprenticeship programme. The first year was spent on day work, learning about quality control measures in place throughout the factory. Then for years two and three he went on shift, alternating between 6am-2pm, 2pm-10pm and – most gruelling of all – 10pm-6am.

During those two years Alan had to learn the ropes of pretty much every job in the factory. Some of them were less than appealing – crawling through seemingly endless boiler tubes in search of corrosion, or digging out the 10-tonne char cisterns. (This last activity took place in 50-degree heat, and was performed in a uniform consisting of nothing more than a loincloth – plus regulation boots.)

After his three years as an apprentice were complete, Alan was given a role as a shift analyst and gradually worked his way up the ranks. In 1977, after 13 years at the factory, he was promoted to Shift Chemist, and the following year, when Thames Refinery celebrated its centenary, he was asked to lead the tour groups around the factory.

In 1981, Alan began the first of a series of international adventures on behalf of Tate & Lyle, when he was sent to help commission new refineries in Pakistan and Mindanao in the Philippines. Subsequent trips would take him to Algeria, Belize, China, Guyana, Saudi Arabia, Swaziland and more. But it was after his official retirement in 1998 that he embarked on his most significant trip abroad. One day after he had handed back his lab coat at Thames Refinery, Alan accepted a role with Tate & Lyle Process Technology in Bromley, working on a rolling two-year contract. A year later, they sent him on a sales trip to Vietnam, where he met the company’s South East Asia agent – and subsequently married her!

Today, Alan is back on site at Thames, working for Tate & Lyle Sugars. As he put it, ‘I have worked all round the world, but my heart and my home has always been at Thames Refinery.’

April 26, 2019

Help us find the Liverpool Sugar Girls!

Almost a decade since we began work on The Sugar Girls, we are finally getting going on a sequel – and this time we’ll be focusing on Henry Tate’s original ‘mother factory’, the Love Lane Refinery in Liverpool.

Almost a decade since we began work on The Sugar Girls, we are finally getting going on a sequel – and this time we’ll be focusing on Henry Tate’s original ‘mother factory’, the Love Lane Refinery in Liverpool.

As we research the new book, we are keen to speak to as many women as possible who worked at Love Lane, any time from WW2 up to the factory’s closure in 1981.

If you know anyone who would be willing to share their memories, do get in touch on 0151 528 9494 or email sugargirlsbook@hotmail.co.uk.

Thanks for your help!

Duncan & Nuala

October 21, 2013

The Sweet Smell of Knowledge

A ‘sugary memory’ from guest-blogger Barbara Nadel

My paternal grandparents were different. Unlike most East End granddads and grandmas in the 1960s they didn’t go down the pub, have a picture of a lady with green skin on their parlour wall or visit Southend on Sea for plates of cockles. Instead they lived in a gas-lit flat that hadn’t seen a new coat of varnish since the 1890s and with no TV, no radio and only my granddad’s disturbing First World War memories for company.

My paternal grandparents were different. Unlike most East End granddads and grandmas in the 1960s they didn’t go down the pub, have a picture of a lady with green skin on their parlour wall or visit Southend on Sea for plates of cockles. Instead they lived in a gas-lit flat that hadn’t seen a new coat of varnish since the 1890s and with no TV, no radio and only my granddad’s disturbing First World War memories for company.

To me they were thrillingly exotic. I loved the fact that every corner of their parlour was crammed with photographs of long dead relatives and I, sometimes alone, would listen for hours on end to my grandfather’s ramblings about his childhood in India. I liked his stories about his mongoose, whose name I can’t now recall. I liked the ones about his bear too, except when he reached to the bit where it got torn to pieces by dogs. A few years ago I wrote a short historical crime series based around a World War 1 veteran, called Francis Hancock, who was loosely based on my grandfather.

But much as I loved my grandparents I hadn’t had to grow up with them. My father, their youngest child, had. And at times it wasn’t pretty. Born in the late 1920s, by the time the Second World War began my father was a young teenager with a keen interest in fire-watching, bomb fragments and homemade bicycles. Because all of my father’s siblings were adults the family didn’t evacuate out of London and so he continued to muck about in the streets of Plaistow, Silvertown, Canning Town and North Woolwich in a pretty unsupervised fashion. My grandfather and his craziness acted as night watchman at the Beckton Gasworks while my grandmother washed and cleaned and fretted about her own mother who could have a whole ‘Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?’ style book devoted to her.

Dad, consequently, was largely free range. Whenever he saw a dead person in a bombed house he just had to get on with how he felt about that. Whole swathes of subjects were taboo in the lives of my Victorian grandparents and that included sex. Granddad was just too weird to talk about it while my grandmother was way too religious at that time. So Dad at thirteen only knew what he’d heard in the playground, from his older siblings and in church. This all boiled down to something about storks, women’s stomachs and strange lavatorial oozes. One night in 1940 however, all that changed very quickly.

Dad was hanging about in Silvertown, down by the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery. He had family and friends inside and was lurking around in the hope of a tin of black treacle or golden syrup when the sirens went off. The docks were going to be hit again and he was over a mile from his home and the safety of the Anderson Shelter in the family’s back yard. Not knowing what to do he began to run. But someone saw him and he was pulled up short by a gruff voice which yelled out, ‘Get in here, mate!’

Dad was hanging about in Silvertown, down by the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery. He had family and friends inside and was lurking around in the hope of a tin of black treacle or golden syrup when the sirens went off. The docks were going to be hit again and he was over a mile from his home and the safety of the Anderson Shelter in the family’s back yard. Not knowing what to do he began to run. But someone saw him and he was pulled up short by a gruff voice which yelled out, ‘Get in here, mate!’

A gate opened and, what turned out to be a very heavily made up woman, pulled him inside the refinery building. Like most of the Tate & Lyle girls she was both glamorous and very frightening to a young boy – and she knew it. ‘Don’t be scared,’ she said as she led him down to the air raid shelter, ‘I won’t eat ya.’ Then she laughed. My dad began to shake. He’d heard his sisters talk about this Tate girl and that Tate girl being able to ‘eat blokes alive’ and he wondered whether he’d actually be better off out in the street taking his chances with the Luftwaffe. But he followed her.

The shelter when they got to it, was packed. Men and women of all shapes and sizes, pretty, ugly, old, fat and thin, all smoking fags and talking at the tops of their voices. Overhead, Dad could just hear the sound of the bombers engines and the whine that always accompanied the dropping of their payloads. Rammed in to what was not a large space, it was hot and when the first bombs hit their targets everybody sweated that little bit more and raised their voices to drown the deadly sound out. The ground shook and my Dad instinctively moved towards to back of the shelter on the basis that if he was near to a wall it would help to protect him from the blast.

Depending on your point of view about sex, this was an error. Because not only did Dad move closer to the back wall, he also moved several light years closer to real sexual knowledge. To use his own words he was suddenly confronted by ‘almost every sexual practice that can happen between a man and a woman and some that shouldn’t be possible’. He gawped. Partly because of what the gorgeous sugar girls were doing with the sugar men but also because he was watching and they didn’t care. Trapped behind a wall of sweating bodies and smoking fag butts he couldn’t escape and so he had to stay where he was, watching these various performances, until they reached their conclusions.

It was quite a night and when the raid was finally over the women he’d seen doing things with their ‘rude bits’ that clearly made them happy, ruffled his hair and smiled at him. He never told his parents about his adventure ever and in fact he didn’t tell his siblings until he was middle aged. But it stayed with him. That vision of the fabulous sugar girls taking life by the balls, as it were, and defying death with joyful sex. Maybe that was why, in spite of his weird background, he was never uptight about sex himself. What consenting adults did to and with each other was OK by him.

It was quite a night and when the raid was finally over the women he’d seen doing things with their ‘rude bits’ that clearly made them happy, ruffled his hair and smiled at him. He never told his parents about his adventure ever and in fact he didn’t tell his siblings until he was middle aged. But it stayed with him. That vision of the fabulous sugar girls taking life by the balls, as it were, and defying death with joyful sex. Maybe that was why, in spite of his weird background, he was never uptight about sex himself. What consenting adults did to and with each other was OK by him.

But when the raid was over and Dad was let out of the refinery something that was of even more interest to a thirteen year old boy who was very often hungry came to pass. Tate & Lyle’s had taken a hit and there were rivers of molten sugar all over the pavements and in the roads around the plant. As it cooled it became soft, sticky caramel which Dad ripped up in long strips and stuck in his mouth and in his pockets. On his way back to Plaistow he ate as much of the molten sugar as he could while wondering what the beautiful Tate & Lyle girls were doing now that the raid was over. He eventually decided that he probably couldn’t imagine anything odder than what he’d seen them do already. As he later said to me, it was his first exposure to the notion that ‘life will always find a way,’ whatever the circumstances and whatever the odds. And he was grateful for it.

Barbara Nadel is an award-winning crime writer and the author of twenty novels. Her most recent, An Act of Kindness , was published earlier this year. For more information on her books, visit www.barbara-nadel.com.

, was published earlier this year. For more information on her books, visit www.barbara-nadel.com.

September 11, 2013

A sugar girl turned GI bride

When we posted a notice on this blog about our next book, calling for stories of British women who had become GI Brides, we never expected to find a woman who was both – and yet that was the case of Frances Telling. Her daughter Lynn contacted us to tell us her story.

Frances was born in 1923 and grew up on Eastwood Road in Silvertown, a stone’s throw from Tate & Lyle’s Plaistow Wharf Refinery. At the age of fourteen she left school and took a job as a sugar packer on the Hesser Floor. After her father had walked out on the family, she had been raised by her mother, who was deaf, and her elderly grandfather, and as an only child she was the main breadwinner of the family.

Tate & Lyle’s Plaistow Wharf Refinery

During the war, the family would gather at a shelter in Lyle Park, although Frances always worried that being deaf her mother would not be able to hear the sirens. The first she would know of the bombs falling was the vibrations that she could feel – one time she got up to answer the door convinced that someone was knocking, only to find it was a raid.

Frances met her GI husband, Richard Ross, at the roller-skating rink at Forest Gate. A corporal in the US Army, he was based at the docks, where he helped supervise the ships that were bringing in supplies for the Americans. At the skating rink, Frances felt sorry for him, since he seemed to be spending more time on the floor than he did skating around. They got talking, and arranged to see each other again. Soon they were dancing together at American Red Cross clubs and playing darts in the local pubs, as well as walking for miles around and ending up on a bench in Lyle Park.

Frances and Richard in Trafalgar Square

In less than a year Frances and Richard were married, in a Baptist church in Plaistow. Strangely, she had been warned that she would marry a foreigner – by a tea leaf reader she had visited a few months earlier. The woman had told her she would move to a different country, never see her mother again, and almost die in childbirth. Frances was so terrified she vowed never to see a fortune teller again.

Richard was from Brooklyn and when Frances told her mother that she would be leaving Silvertown to live with him in New York, the poor woman was devastated – as a deaf single mother she had always relied on her daughter’s help and support and she was worried about how she would cope on her own.

When the war ended, Richard was shipped home and Frances awaited passage as a war bride. But she was already pregnant, and gave birth to baby Lynn before she could be reunited with her husband. She developed pre-eclampsia and was seriously ill for several weeks, so Lynn went to live with her grandmother.

It was almost a year later that Frances finally made her way to the United States, on a liberty ship, the George Washington Goethals. Like many women, she was upset at the way she was treated by the American authorities, who were often suspicious that GI brides, particularly those from poorer backgrounds, were using marriage as a ticket to a richer country. ‘I was made to feel like a tramp’, she later told her family.

It was a stormy crossing, and Frances was badly seasick. At one point the ship rocked so violently that her daughter’s crib broke loose of its fixings and careened across the deck and into a bulkhead, leaving the baby with a nasty cut to her chin. Frances was filled with relief to finally arrive at the pier in New York, where Richard came running up the gangway with a beautiful cocker spaniel puppy in his arms. (His mother had given him some money to buy a new suit for the occasion, but he had decided that a new dog was much more suitable!)

Frances and Richard went to live with his mother in her small apartment in Brooklyn. It was a difficult time for Frances – Mrs Ross felt that her son had married beneath himself and largely ignored her new daughter-in-law, although fortunately she adored baby Lynn. It was a relief when they were able to move out and go to live with Richard’s grandmother in Milford, Connecticut, in a house just a block away from the beach.

When the old lady died, Richard and Frances remained in her house, and they stayed in Connecticut for the next fifty years. Richard got a job in the paint department of Sears Roebuck, where he worked his way up to become manager. When he retired, the couple moved to Florida.

At first Frances found it hard to adjust to life in America, and she felt that people she met were so fascinated by her English accent that they didn’t bother to listen to what she was saying. She was shocked when she saw her first teabag and avoided ‘foreign’ dishes such as pizza and spaghetti. But in time, she found a group of British women in Milford, the British-American Club, which became one of the focal points of her life.

Although Frances grew to enjoy life in America, her great regret was for her deaf mother, left behind in England. Although she wrote to her regularly, and sent pictures every few months, she was unable to travel home to visit until the 1950s, when her mother was dying. For the rest of her life, Frances felt troubled by guilt at having left her to become a GI bride, although for the most part she enjoyed her life in America.

Frances and Richard remained married for 64 years. She died in 2009 at the age of 86. Her relatives brought some of her ashes back to England and scattered them in Lyle Park.

March 27, 2013

Listen to Gladys and Eva on Radio 4’s Midweek

This morning, sugar girls Gladys Hudgell and Eva Rodwell were star guests on BBC Radio 4’s Midweek, hosted by Libby Purves.

Glad and Eva livened up the Wednesday morning discussion show with tales of their experiences at the Tate & Lyle sugar factories in the East End in the 1940s and 1950s – in particular, the pranks they used to get up to.

Gladys recounted the time she got her own back on a strict forelady by taking a nest of mice into her office and scaring her witless, while Eva talked about the fights that used to go on amongst the workforce of rowdy 15 and 16-year-olds.

If you missed it, you can listen to the interview here:

Listen to Gladys and Eva on Radio 4′s Midweek

This morning, sugar girls Gladys Hudgell and Eva Rodwell were star guests on BBC Radio 4′s Midweek, hosted by Libby Purves.

Glad and Eva livened up the Wednesday morning discussion show with tales of their experiences at the Tate & Lyle sugar factories in the East End in the 1940s and 1950s – in particular, the pranks they used to get up to.

Gladys recounted the time she got her own back on a strict forelady by taking a nest of mice into her office and scaring her witless, while Eva talked about the fights that used to go on amongst the workforce of rowdy 15 and 16-year-olds.

If you missed it, you can listen to the interview here:

March 10, 2013

The Sugar Girls’ guide to life after Call the Midwife

With the second series of Call the Midwife coming to an end tonight, we’ll be subject to an agonizing – and appropriate – nine-month wait before our favourite nuns and nurses get back on their bikes for the Christmas special. So if you, like us, are dreading the post-partum depression that will inevitably follow the series finale, here are our suggestions for how to pass the time while you wait for the next delivery.

Before Call the Midwife’s smash success, series writer Heidi Thomas was best known for her adaptation of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford , but it was an earlier series that really laid the foundation for her writing about the working-class inhabitants of Poplar. Lilies

, but it was an earlier series that really laid the foundation for her writing about the working-class inhabitants of Poplar. Lilies was inspired by her own family history living around the docks of Liverpool in the 1920s. For anyone who loves the heart wrenching family drama of Call the Midwife, the eight-part series is a must.

was inspired by her own family history living around the docks of Liverpool in the 1920s. For anyone who loves the heart wrenching family drama of Call the Midwife, the eight-part series is a must.

If you can’t get enough of the 1950s East End, aside from the amazing trilogy of books on which Call the Midwife is based (Call The Midwife , Shadows of The Workhouse

, Shadows of The Workhouse and Farewell to The East End

and Farewell to The East End , now available in one bumper edition

, now available in one bumper edition ), check out Gilda O’Neil’s fascinating book My East End

), check out Gilda O’Neil’s fascinating book My East End , which captures the area in the words of those who lived there. And if you want an absorbing tale of a life lived in the shadow of the East End docks, Melanie McGrath’s wonderful book Silvertown

, which captures the area in the words of those who lived there. And if you want an absorbing tale of a life lived in the shadow of the East End docks, Melanie McGrath’s wonderful book Silvertown – which tells her own grandmother’s story in gripping detail – is hard to beat.

– which tells her own grandmother’s story in gripping detail – is hard to beat.

Meanwhile, if you’re after more first-person memoirs of twentieth-century women’s lives, try Angela Patrick’s book The Baby Laundry for Unmarried Mothers , which tells the heartbreaking story of a woman who – like Joan in The Sugar Girls – was forced to have her illegitimate child in a home run by nuns, and to give the baby up for adoption. West End Girls

, which tells the heartbreaking story of a woman who – like Joan in The Sugar Girls – was forced to have her illegitimate child in a home run by nuns, and to give the baby up for adoption. West End Girls by Barbara Tate (no relation to the sugar manufacturers!) tells of the colourful scenes she witnessed as the maid to a Soho prostitute during the 1940s.

by Barbara Tate (no relation to the sugar manufacturers!) tells of the colourful scenes she witnessed as the maid to a Soho prostitute during the 1940s.

And of course, if you love true stories of life in the East End during the 1950s, do check out The Sugar Girls too. Focusing on Tate & Lyle’s female factory workers in Silvertown, not far from the midwives’ stomping ground of Poplar, it tells true stories of ordinary working-class lives in a thriving industrial area. There’s a fair share of heartache, but plenty of fun and romance too – and if the absence of Call the Midwife has left you with a craving for baby drama, The Sugar Girls features three pregnancies!

too. Focusing on Tate & Lyle’s female factory workers in Silvertown, not far from the midwives’ stomping ground of Poplar, it tells true stories of ordinary working-class lives in a thriving industrial area. There’s a fair share of heartache, but plenty of fun and romance too – and if the absence of Call the Midwife has left you with a craving for baby drama, The Sugar Girls features three pregnancies!

And if all that doesn’t keep you busy until we return to Nonnatus House at Christmas, you can always start bingeing on the 900-minute Call the Midwife boxset .

.