G. Wayne Miller's Blog

December 26, 2025

An interview in my study conducted by my son, G. Calvin Miller, on Feb. 3, 2008. Watch it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Chz7...

December 11, 2025

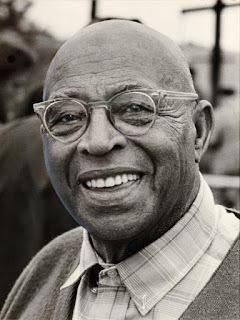

Twenty-three years ago. RIP, Dad

Author's Note: I wrote this 13 years ago, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of my father's death. Like his memory, it has withstood the test of time. I have slightly updated it for today, December 11, 2025, the 23nd anniversary of his death. Read the original here.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.

Roger L. Miller as a boy, early 1920s.My Dad and Airplanes

by G. Wayne MillerI live near an airport. Depending on wind direction and other variables, planes sometimes pass directly over my house as they climb into the sky. If I’m outside, I always look up, marveling at the wonder of flight. I’ve witnessed many amazing developments -- the end of the Cold War, the advent of the digital world, for example -- but except perhaps for space travel, which of course is rooted at Kitty Hawk, none can compare.

I also always think of my father, Roger L. Miller, who died 22 years ago today.

Dad was a boy on May 20, 1927, when Charles Lindbergh took off in a single-engine plane from a field near New York City. Thirty-three-and-a-half hours later, he landed in Paris. That boy from a small Massachusetts town who became my father was astounded, like people all over the world. Lindbergh’s pioneering Atlantic crossing inspired him to get into aviation, and he wanted to do big things, maybe captain a plane or even head an airline. But the Great Depression, which forced him from college, diminished that dream. He drove a school bus to pay for trade school, where he became an airplane mechanic, which was his job as a wartime Navy enlisted man and during his entire civilian career. On this modest salary, he and my mother raised a family, sacrificing material things they surely desired.

My father was a smart and gentle man, not prone to harsh judgment, fond of a joke, a lover of newspapers and gardening and birds, chickadees especially. He was robust until a stroke in his 80s sent him to a nursing home, but I never heard him complain during those final, decrepit years. The last time I saw him conscious, he was reading his beloved Boston Globe, his old reading glasses uneven on his nose, from a hospital bed. The morning sun was shining through the window and for a moment, I held the unrealistic hope that he would make it through this latest distress. He died four days later, quietly, I am told. I was not there.

Like others who have lost loved ones, there are conversations I never had with my Dad that I probably should have. But near the end, we did say we loved each other, which was rare (he was, after all, a Yankee). I smoothed his brow and kissed him goodbye.

So on this 22nd anniversary, I have no deep regrets. But I do have two impossible wishes.

My first is that Dad could have heard my eulogy, which I began writing that morning by his hospital bed. It spoke of quiet wisdom he imparted to his children, and of the respect and affection family and others held for him. In his modest way, he would have liked to hear it, I bet, for such praise was scarce when he was alive. But that is not how the story goes. We die and leave only memories, a strictly one-way experience.

My second wish would be to tell Dad how his only son has fared in the last 22 years. I know he would have empathy for some bad times I went through and be proud that I made it. He would be happy that I found a woman I love, Yolanda, my wife now for ten years and my best friend for almost two decades: someone, like him, who loves gardening and birds. He would be pleased that my three wonderful children, Rachel, Katy and Cal, are making their way in the world; and that he now has three great-granddaughters, Bella, Liv and Viv, wonderful girls all. In his humble way, he would be honored to know how frequently I and my children remember and miss him. He would be saddened to learn that his oldest child, Mary Lynne, died this year (How many lives did my sister Mary Lynne Wright touch? How many did she heal? She enrolled in nursing school in the mid-1960s and remained in healthcare until her retirement a few years ago, so surely it is tens of thousands, if not more. She personified what Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing said: “Nursing is an art: and if it is to be made an art, it requires an exclusive devotion as hard a preparation as any painter's or sculptor's work.” No one knew this better than her husband of 56 years: my brother-in-law, Walter “Duke” Wright. RIP, ML.) and his younger daughter, Lynda, died in 2015. But that is not how the story goes, either. We send thoughts to the dead, but the experience is one-way. We treasure photographs, but they do not speak.

Lately, I have been poring through boxes of black-and-white prints handed down from Dad’s side of my family. I am lucky to have them, more so that they were taken in the pre-digital age -- for I can touch them, as the people captured in them surely themselves did so long ago. I can imagine what they might say, if in fact they could speak.

Some of the scenes are unfamiliar to me: sailboats on a bay, a stream in winter, a couple posing on a hill, the woman dressed in fur-trimmed coat. But I recognize the house, which my grandfather, after whom I am named (George), built with his farmer’s hands; the coal stove that still heated the kitchen when I visited as a child; the birdhouses and flower gardens, which my sweet grandmother lovingly tended. I recognize my father, my uncle and my aunts, just children then in the 1920s. I peer at Dad in these portraits (he seems always to be smiling!), and the resemblance to photos of me at that age is startling, though I suppose it should not be.

A plane will fly over my house today, I am certain. When it does, I will go outside and think of young Dad, amazed that someone had taken the controls of an airplane in America and stepped out in France. A boy with a smile, his life all ahead of him.

My dad, second from top, with two of his sisters and his brother.

My dad, second from top, with two of his sisters and his brother. Dad, near the end of his life.

Dad, near the end of his life.November 30, 2025

LIFE HAPPENED by G. WAYNE MILLER Copyright 2025 gwaynemi...

LIFE HAPPENED by G. WAYNE MILLER

Copyright 2025 gwaynemiller.com

WGA registry no. 2222611

Library of Congress Registration PAu 4-278-689

LOGLINE

During a momentous historical period – the late 1970s and early 1980s – that is eerily reminiscent of today, politics, love, drugs, murder, mystery, music, racism, mental illness and sex collide at the fictional The Daily Times, where the Pulitzer Prize-winning staff seeks to tell truths, right wrongs, and help keep democracy alive. Available for production, contact me or my screen agent: Michael Prevett, Circle Management and Production.

August 23, 2025

Burnt Cove sold to major publisher!

I am excited to announce that Burnt Cove, my 22d novel, will be published by a major house in hardcover, paperback, audio and e- editions! They have asked me not to name them until we have completed editing and production and are ready to begin sales and marketing. When we get there, I will make the announcement. This is a book a long time in the writing and to finally be here is something I only imagined… until now! This not my first novel set in Maine. See the rest of my books at http://www.gwaynemiller.com/books.htm

July 18, 2025

Alan Hassenfeld's obituary, as published by Sugarman Sinai Memorial Chapel. Additional tributes follow after the end.

This is Alan’s obituary, as published by Sugarman Sinai MemorialChapel. Additional tributes follow after the end.

Alan G. Hassenfeld, former Chairman and CEO of Hasbro,Inc., and a global philanthropist, passed away peacefully in his sleep onJuly 9, 2025, in London. He was 76.

Born November 16, 1948, into the founding family of Hasbro,Hassenfeld became CEO in 1989 following the untimely death of his brother,Stephen. Though initially reluctant to lead, he transformed the company into anindustry powerhouse. Under his stewardship, Hasbro acquired Tonka Parker Kennerbringing iconic brands Play-Doh, Monopoly, and Nerf into its portfolio andelevating it to #169 on the Fortune 500.

Hassenfeld’s true legacy, however, lies in his profoundhumanitarian spirit. He championed corporate social responsibility, productsafety, and he worked to eliminate the use of child labor in toy industrymanufacturing. His compassion was most vividly expressed through philanthropy.He spearheaded the founding of Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence (1994),a landmark achievement funded partly by his leadership and a $2.5 millionpersonal donation. In 2008, he established the Hassenfeld Family Initiatives,supporting countless causes focused on children, education, health, and socialjustice worldwide. His guiding principle was simple yet profound: "Bringsunshine where there’s darkness."

Dr. Ashish Jha of Brown University School of Public Health,home to the Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation Initiative noted that "Hepushed us to make sure our work was relevant to the people of this state andconstantly focused on impact, an extremely funny and warm person. Personally, Iwill miss his late-night phone calls railing against the injustices of theworld and ask what we were doing to make things better. His passing is a hugeloss to the world.”

Hassenfeld was also a civic force. He founded "RightNow!", a successful Rhode Island ethics and campaign finance reformmovement. He fostered a culture of giving at Hasbro, pioneering employeevolunteer programs like "Team Hasbro" and "Global Day ofJoy."

Alfred J. Verrecchia, former Hasbro chairman and CEO and alongtime friend of Hassenfeld. “He devoted himself to making the world a betterplace. He was happiest when he was helping people. He wasn’t afraid to put hisname and reputation on the line for something he believed.”

Tributes poured in from global leaders, colleagues, andbeneficiaries.

Rabbi Leslie Y. Gutterman said "He gave generously andselflessly of his time, his treasure and his love.”

The Toy Association hailed his "visionary andpassionate leadership" and tireless advocacy for children.

Hasbro stated his "enormous heart" remains thecompany's guiding force.

Alan Hassenfeld is survived by his wife, Vivien;stepchildren Karim and Leila Azar; sister Ellen Block; nieces Susan BlockCasdin and Laurie Block; nephew Michael Block; grandchildren Chloe, Talullah,Kaia, and Khalil; and grand-nephews Kinsey and Blaisdell Casdin.

Funeral services will be this Sunday, July 20, 2025 at 10:00am at Temple Beth-El, 70 Orchard Avenue, Providence, RI. Private burial tofollow.

For those unable to attend services in person, you may joinvia livestream at https://www.temple-beth-el.org/live-s...

In lieu of flowers, donations in Alan’s memory may be madeto Hasbro Children’s Hospital – Greatest Needs Fund or The Miriam Hospital –Centennial Campaign Fund. Both can be accessed athttps://giving.brownhealth.org/Hassen...

An irreplaceable loss to Rhode Island, the toy industry, andthe world’s children, Alan Hassenfeld’s legacy of compassion, innovation, andjoyful generosity will endure.

Arrangements are in the care of Sugarman-Sinai MemorialChapel, Providence, R.I.

Additional tributes:

“Alan had alife-long commitment to making things better for children, whom he called ‘our most important natural resource,’ ” saidElizabeth Burke Bryant, Professor of the Practice, Brown School of PublicHealth/Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation Institute, and former executivedirector of Rhode Island KIDS COUNT. “His sense of urgency - that all kidsdeserve a high quality education, access to health care, and opportunities todiscover their talents and reach their full potential -- never wavered, When anopportunity arose to make a difference for kids, he leapt into action, such aswhen he joined with others to successfully advocate for the Children's HealthInsurance Program to be reauthorized by Congress so coverage wouldn't lapse. Hesaid then that ‘children cannot Wait’, which sums up his purpose and hispassion for the children of Rhode Island, the nation, and the world.”

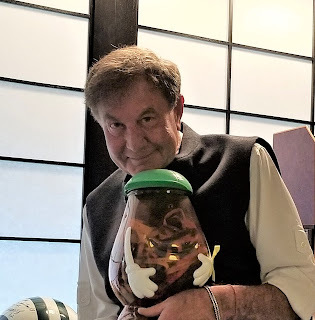

Alan with Mr. Potato Head - Photo by G. Wayne Miller

Alan with Mr. Potato Head - Photo by G. Wayne Miller“Alan was a pillar of the local and world community,” saidNeil Steinberg, former head of the Rhode Island Foundation and former chair ofthe Rhode Island Life Science Hub. “His empathy, commitment, and generosityleave an amazing legacy! He also epitomized the slogan “every boy loves aHasbro toy.”

May Liang, president of the China Toy and Juvenile ProductsAssociation, was another who paid tribute to Hassenfeld, saying: “Alan was agreat industry leader with global vision, pioneering spirit and unwaveringdedication. I can strongly feel he always had passion with the toy industry.Alan's pass away is not only a loss of toy industry [but] also a loss ofadvisor and friend for myself.”

“Alan's lifeand legacy was marked by a deep and profound dedication to bringing smiles andhope to the world's children,” said Kathrin Belliveau, Chief Policy for TheToy Association, the industry organization. “As CEO and a business leader, he pioneered the idea of corporatesocial responsibility, rooted in adeep and unwavering belief that businesses must operate responsibly fromproducing products of the highest quality and safety for children to ensuringsupply chains were upholding human rights and eradicating child labor andforced labor.”

“Alan's passion, heart, and visionaryleadership have left a lasting mark on the toy world and beyond,” said DanKlingensmith, G.I. Joe historian, archivist and author. “I’ll never forget theexperience of having Alan speak at our VIP event during HASCON. His warmth,humor, and love for G.I. Joe came through in every story he shared, leavingeveryone in the room inspired. Beyond the toys, Alan’s work with HasbroChildren’s Hospital shows just how deeply he cared about making a difference.He was more than a business leader—he was a true example of kindness,generosity, and heart."

“This is notabout me, it is about Alan,” said Karen McKay Davis, president of Hasbro’sChildren’s Fund during Hassenfeld’s tenure. “So many things keep coming tomind, we were one of the first companies to launch an employee volunteerprogram, giving employees 4 hours a month of paid time off to volunteer withchildren. We did this with Alan under Colin Powell and America's Promise. TeamHasbro went on to be one of the most successful corporate volunteer programswith over 95% of our employees engaged in the community. It led to Global Dayof Joy where employees worldwide would volunteer together in their communities,bringing joy to children in need. It created an amazing culture. All becauseAlan believed in the power of service and a true culture of giving.”

The Toy Association stated: “As the former CEO and Chairmanof Hasbro, Inc., Alan was a visionary and passionate leader in the toyindustry. He was the past chairperson of The Toy Association, chairperson ofthe Toy Industry Hall of Fame committee, and himself a distinguished Toy AssociationHall of Fame inductee. Alan’simpact was far-reaching and global, extending beyond his role at Hasbro. Fromhis tireless work championing ethical sourcing to his unwavering advocacy forchildren’s rights and philanthropy during times of crisis and profound need,his legacy will continue to inspire us all for generations to come.”

Alan in his office - Photo by G. Wayne Miller

Alan in his office - Photo by G. Wayne MillerHasbro issued this statement: “Today, the entire Hasbrocommunity is mourning the loss of Alan Hassenfeld—our beloved former Chairmanand CEO, a cherished mentor, and dear friend. Alan's enormous heart was, andwill remain, the guiding force behind Hasbro - compassionate, imaginative, anddedicated to bringing a smile to the face of every child around the world. Histireless advocacy for philanthropy, children's welfare, and the toy industrycreated a legacy that will inspire us always. While we grieve deeply, we alsocelebrate Alan's remarkable life and the incredible impact he made. Our deepestcondolences go out to his family, friends, and everyone who had the privilegeof knowing and loving him.”

Said Hassenfeld biographer G. Wayne Miller: “RIP Alan,philanthropist, benefactor and corporate leader during his many years aschairman and CEO of Hasbro. He was a uniquely great man and dear friend of morethan 30 years who cared deeply for others and did all he could to improve livesin Rhode Island and across the country and globe.”

During a public forum in 2018, Hassenfeld was asked aboutthe guiding principle behind his philanthropy.

“That’s easy,” he said. “Any time any of us sees a childwho’s not smiling, who’s going through problems—if we're able to turn thatgrimace into a smile, that makes your heart just absolutely feel so good. Whatmakes me happiest is trying to be creative in philanthropy and trying to makesure that we're making a difference because too often I think we give but wedon't think necessarily what the end goal is going to be. And so for me, theend goal is how do we bring sunshine where there’s darkness.”

May 31, 2025

Cabot's Neck: A supernatural novel with demons, curses and time travel. In progress.

Just hit the 30,000 word mark!

CABOT’S NECK

by

G. Wayne Miller

Copyright 2025 gwaynemiller.com

WGA registration # 2286466

Chapter One

Nothing there

“I love this beach!” seven-year-old Cassie Cabot said. “Momand Dad, can we come back here tomorrow?”

“Yes!” said her mother, Daniela Cabot.

“And every day until vacation’s over!” said her father, JimCabot.

“Yay!”

It was the summer of 2027 and the Cabots, who lived inBoston, had rented a house in Ipswich, Massachusetts, to celebrate goodfortune: Daniela, one of the world’s top video game designers, had justcompleted her latest game; Jim, an expert in AI, had recently been promotedfrom visiting lecturer to assistant professor at MIT; and Cassandra, who likedbeing called Cassie, would start second grade at summer’s end after acingfirst.

Cassie packed the seashells she’d collected into herbackpack, her parents gathered the blanket and cooler, and they started towardtheir car down the long, narrow, tree-covered path that was the only landaccess to the beach.

“Dad, can you tell me again how this peninsula got itsname?” Cassie said. She was precocious, but she never flaunted herintelligence.

“You never tire of that story, do you,” Daniela said.

“Nope,” her daughter said

“Cabot’s Neck was named by one of my ancestors, JosephCabot, son of John Cabot, who came to America from England in 1700,” Jim said.“Joseph was born in Salem and he became wealthy enough to buy this land, which laterCabots donated to Ipswich for public use.”

“But he made hismoney in a bad way,” Cassie said.

“He did,” Jim said.

“In the rum and slave trades,” Daniela said.

“For which Cabots born later made reparations,” Cassiesaid. “Tell me again: what are reparations?”

“Amends for terrible things done in the past,” Jim said.“My family later apologized and paid a lot of money to descendants of slaves.But money of course cannot undo the damage.”

“Your family was good,” Cassie said.

“Some members, anyway,” Jim said. “Now enough history.Let’s gather our stuff and get out of here. Hotdogs for dinner and S’mores fordessert.”

“Yay!” Cassie said. She ran ahead of her parents andstopped by an old oak tree.

When Daniela and Jim reached her, she was rubbing her handalong the tree trunk.

“How old do you think it is?” she said.

“It probably was here when Joseph Cabot bought this land,”Jim said.

“Wow,” Cassie said. “That’s ancient.”

“That lower limb has a rope tied around it,” Daniela said.

It was a small, weathered strand that had been cut near theknot.

“Probably was a rope swing,” Cassie said.

“Or an ancient gallows,” Jim joked. “Maybe they marchedwitches in from Salem to hang them.”

“Not funny, Jim,” Daniela said.

“I wasn’t joking,” Jim said. “There were witches galoreback then, or so the Puritans believed. Let me show you the latest story Ifound. It’s fascinating.”

Cabot's Neck: A supernatural novel with demons, curses and time travel

CABOT’S NECK

by

G. Wayne Miller

Copyright 2025 gwaynemiller.com

WGA registration # 2286466

Chapter One

Nothing there

“I love this beach!” seven-year-old Cassie Cabot said. “Momand Dad, can we come back here tomorrow?”

“Yes!” said her mother, Daniela Cabot.

“And every day until vacation’s over!” said her father, JimCabot.

“Yay!”

It was the summer of 2027 and the Cabots, who lived inBoston, had rented a house in Ipswich, Massachusetts, to celebrate goodfortune: Daniela, one of the world’s top video game designers, had justcompleted her latest game; Jim, an expert in AI, had recently been promotedfrom visiting lecturer to assistant professor at MIT; and Cassandra, who likedbeing called Cassie, would start second grade at summer’s end after acingfirst.

Cassie packed the seashells she’d collected into herbackpack, her parents gathered the blanket and cooler, and they started towardtheir car down the long, narrow, tree-covered path that was the only landaccess to the beach.

“Dad, can you tell me again how this peninsula got itsname?” Cassie said. She was precocious, but she never flaunted herintelligence.

“You never tire of that story, do you,” Daniela said.

“Nope,” her daughter said

“Cabot’s Neck was named by one of my ancestors, JosephCabot, son of John Cabot, who came to America from England in 1700,” Jim said.“Joseph was born in Salem and he became wealthy enough to buy this land, which laterCabots donated to Ipswich for public use.”

“But he made hismoney in a bad way,” Cassie said.

“He did,” Jim said.

“In the rum and slave trades,” Daniela said.

“For which Cabots born later made reparations,” Cassiesaid. “Tell me again: what are reparations?”

“Amends for terrible things done in the past,” Jim said.“My family later apologized and paid a lot of money to descendants of slaves.But money of course cannot undo the damage.”

“Your family was good,” Cassie said.

“Some members, anyway,” Jim said. “Now enough history.Let’s gather our stuff and get out of here. Hotdogs for dinner and S’mores fordessert.”

“Yay!” Cassie said. She ran ahead of her parents andstopped by an old oak tree.

When Daniela and Jim reached her, she was rubbing her handalong the tree trunk.

“How old do you think it is?” she said.

“It probably was here when Joseph Cabot bought this land,”Jim said.

“Wow,” Cassie said. “That’s ancient.”

“That lower limb has a rope tied around it,” Daniela said.

It was a small, weathered strand that had been cut near theknot.

“Probably was a rope swing,” Cassie said.

“Or an ancient gallows,” Jim joked. “Maybe they marchedwitches in from Salem to hang them.”

“Not funny, Jim,” Daniela said.

“I wasn’t joking,” Jim said. “There were witches galoreback then, or so the Puritans believed. Let me show you the latest story Ifound. It’s fascinating.”

May 15, 2025

"Sweetie," the audio version. By Charles Conover, distinguished voiceover artist and audio narrator.

"Sweetie"was originally published in 1990, and reprinted in Vapors, The Essential G. Wayne Miller Fiction, Vol 2.

Charles Conover

Charles ConoverListen to Conover's narration.

February 25, 2025

A story I wrote during my first month as a journalist. I was a staff writer at the long-gone North Adams (Mass.) The Transcript.

February 12, 2025

An Island in Winter: A story written a long time ago

Thanks to Antonia Noori Farnaz, esteemed Providence Journal reporter who brought this to my attention. She wrote wonderfully today about another island, Prudence, in winter.

An island in winter, a people apart Story by G. Wayne Miller in The ProvidenceJournal, March 6, 1983

ICE SKIMS PONDS no larger than big-city puddles. Buildings are shuttered and boarded tight. The sounds aresurf, cries of angry ocean birds, wind. And everywhere, in the snowless thickets and fields, in the sky and on the sea, along the towering southernbluffs, the predominant shades are brownsand yellows and greys.

The road north to Sandy Point, where white settlerswaded ashore 322 years ago, twists and winds up over rolling hills and back down into lonely hollows.The road is cold and bare, empty of people on bicycles or in cars. To the west,Great Salt Pond is one big mirror,a lusterless reflector of sky, unbrokenby boats or bathers.

These are the broad brush strokesof Block Island on an overcast winter afternoon - a bleak, Victoriancomposition faithfully lifted from one ofThomas Hardy's best brooding landscapes. The summer visitors are all gone now, gone back home to far-awaywork and schooland business. Now it is an islander's island, 12 lonelymiles out to sea.

Tending North Light many years ago

Tending North Light many years ago"A PLACE where you can find yourself," says Barbara Brown, school secretary.

"Atime to settle down," says Gladys Steadman, who is spending her 93rd winter on the island.A season of harsh, austerebeauty, more Irelandor Wales than Rhode Island.

At night, and in day, the chilled wind whistlesand moans as it comes sneaking inside, uninvited, throughcracks around windowsand loosely fitting doors. For a moment, the moon winks through the clouds, andthen it is gone, leavingonly the sweep of Southeast Light against the starless black of the evening sky.

On Water Street, the great turn-of-the-century waterfront hotels are all closed now, their breezy August charms locked and frozen. Inside boarded shops, an army of silent mopeds waits. The Empire Theatre's next screening is in June."Sorry, we're closed," reads the smallorange-on-black sign on Barone's Restaurant.

Only at ferry time,once daily at quarter past noon, and three timeson Fridays, will Water Streetbarely - just barely - awaken from its winter slumber. Then, two or three dozen souls will gather to unload freight, or greet returning friendsand relatives from the mainland, which almost everybody here on the rock calls"America." In half an hour, everyonewill be gone again.

BACK A BLOCK from the sea, on Chapel Street, one of the island's year-round residents is having coffee at theNumber One Cafe. He's Kevin Jones, licensedrefrigeration specialist, owner of the island's two laundries,longtime Cable TV Committeeman. He's lived on the island so long that they've named a sandwich for him at McAloon'sSaloon, a popular watering hole.

"In order to be here in the winter," Jones says, "youhave to be a person basically happy with yourself. Otherwise, you couldn'tmake it. You're living in a very small community. You can't be a person who requiresgoing to the movies all the time,all those othermainland things."

"It'sreally easy-going, low-key," says Howell T. Conant Jr., publisher of the island's only year-roundnewspaper. "There are no rulesand regulations. There'sno traffic. There'sno noise. You can take a walk onthebeach and not see a soul. You walk into a restaurant, and they're all your friends. You don't lock the doors ortake the keys out of the car."

No one has an exact figure,and there have been severalbabies born sincethe last officialcensus, but the year-round population of New Shoreham, R.I., is thought by most islanders to fall somewhere between 600 and 700 people, of which 80 are schoolchildren, and even more are retirees.

"On a busy summerweekend, when we have a harbor full of boats,when we have ferries operating and planes landing, we probably get up around 7,000, 8,000 people," says Police Chief Paul Riker, one of two year-round cops.

Riker has a summertime force of six, with at least one officer on headquarters duty 24 hoursa day, seven days a week. In July, about the peak of the tourist season, his department responded to 353 calls. In January,it was two dozen. Thesedays, when the chief pullsthe graveyard shift,as he often does, he sleeps at homewith the phone by his bed. It almost never rings.

ALMOST ANYTHING you can count on the island is like that - abysmally low in winter, astronomically high insummer. A crazy roller-coaster life, a peaks-and-valleys kind of existence that never lets up, never evens out year after year, for those who have chosen to sink their roots into Block Island's sandy soil.

With the cold weathercome the closingsand the reducedhours, the layoffsand shutoffs, the rollbacks and cutbacks. These are winter facts on the island: A single operating hotel, the 1661 House. One bank, FleetNational, hours, Tuesdaysand Fridays, 9 to 1. A hardware store, John Rose & Co., open an hour a day, noon to 1.

These are more winter facts: One grocery store, the SeasideMarket. One doctor.One state nurse. Nopharmacy, no department store, no dentist, no baker, no barber, no hairdresser, no cobbler. In winter, thesemean mainland trips. And this grim winter fact: unemployment averaging 27 percent, up 20 or more points from summer.

FOR THOSE workerswithout work, winter is a constant struggle, a touch-and-go battle against boredom andcabin fever - sometimesfought, and sometimes lost, inside the four bars that stay open year-round. Often, it is summer savings or unemployment compensation or pick-up work, never high-paying, never guaranteed,that help the unlucky and unable to scrape by.

Cheryl Shea,19, was joblessmuch of the winter, untilshe was hiredto cook mealsfor a group of phone company workers who spentseveral weeks on the islanddoing major maintenance. Still, for her and her boyfriend, who is trying like crazy to get an auto repair shop off the ground, winter times are tough times, toughfinacially and emotionally.

"Winters are hard for everybody," she says as she cleansup after breakfast. "You're lucky to get a job.Families out here, I don't know how they do it. Still, we love it in the winter. You don't see your friends in the summer ever.Everyone is tryingto save something for the winter."

THOSE HOLDINGcold-weather jobs eitherwork for the state, or the town,or in the few open restaurants or bars. They go lobstering or quahogging, or do construction - especially construction. On some days, when the ever-blowing wind is at rare whisper-level, the clutter of hammers and saws can be heard against the sounds of the ocean and its restlessgulls.

There are those who say that Block Island is on the verge of a development boom, and there is no doubt that plenty of new construction is planned or underway, but the big chores in winter are repairs and additions to islanders' homes, to hotels, to cottages owned by off-islanders. Most new starts come in spring and summer.

Weatherthis winter, unseasonably mild and virtually snowless, has been a bonanza for everyone, particularlythe laborers. So says the island'scorporate memory, Fred Benson, a greatly respected old man who has been a baseballcoach, a fisherman, a mechanic, a broker, a notary publicand a whole host of other peoplein his eight decades on theisland.

The late Fred Benson

The late Fred Benson

"Whatwe call a real soft winter," says Benson in his office, a hole-in-the-wall affair he has plastered proudlywith the snapshots and proclamations and yellowing newspaper clippings and chartsthat document the manyaccomplishments of his 87 years."I've seen it snow threedays and threenights steady. I've seen 22 inches of ice on the ponds.I've seen upwardsof 30 inches of frostin the ground."

THOSE WERE winters when ice skating and hockey were the big outdoors events, but there has been little ofeither this year. There have been some walks on the beach, some jogging,some mainland trips for shoppingor entertainment, but this winter,like most, has been mostly an indoorsaffair.

That means cards and parties,dinners and Bruins games on cable TV. It means town politics - in 1983, the politicsof development, the pros and cons of rental mopeds. It means hanging out in bars, or evenings by the propane-gas heater or the coal stove, because there'sno abundance of home-grown firewood.Mostly, it means seeing moreof your neighbors.

Winter weaves a bond, Block Islanders will tell you in their more poetic moments, a certain special fraternitythat can't hide behind their traditionally crusty Yankee respectfor privacy.

Their word for it is family,a word that crops up again and again, even in the idlest chit-chat. "You don't see them any other time," says Jones. "Inwinter, you see everybody. You catch up."

"Especially in winter," says the island'sonly year-round clergyman, Tony Pappas, Baptistpastor of Harbor Church, "Block Island is very human and personal, a face-to-face community. That's why we've stayed here for seven years. It's a community where we can relate to others."

IN WINTER,only the dailyferry and the noon fire siren reallymark the passageof time, and an islander's schedule is relaxedand casual. Clothing, too, is casual - casual and rugged. Flannel shirts, wool caps andcoats, Levi's copper-riveted jeans, down vests, work boots - these are the islanders' hallmarks. Maybe every fourth man is bearded;many others have two or three days'growth.

Beneath the outward tranquility and solitude, the satisfaction with their winter lot, is the islanders' shadowyfeeling that, someday,somehow, paradise couldbe lost. Already,it is threatened. What yearsago was the traditional Memorial Day-to-Labor Day rush is now an extended tourist season, three months longer. That's three fewer months the island is the islanders'.

Still, on an overcastBlock Island winter afternoon, thoughts of tourists, the economic lifeblood of the island,are far away.

Says Conant: "I wish there was a way to make this place like this all the time. Twenty more people on thisisland is 20 too many. I think a lot of people feel possessivebecause they're part of winter here. It makes them special,like they're a part of Block Island."

Copyright © 1983. LMG Rhode Island Holdings, Inc. All Rights Reserved.