Aperture's Blog

February 3, 2026

11 Exhibitions to See This Winter

Michella Bredahl, Sybilla in her room, 2013

Michella Bredahl, Sybilla in her room, 2013Courtesy the artist and Huis Marseille

Michella Bredahl — Amsterdam

Having begun a modeling career at fourteen years old, Michella Bredahl felt the intrusions of a camera’s gaze early on. By contrast, her own portraits of young women, many with unstable upbringings that mirror her own, are grounded in trust and collaboration. In the Danish photographer and filmmaker’s first museum exhibition, portraits of pole dancers, new mothers, artistic peers, and chosen family derive their strength from displays of unguarded tenderness. “She had a specific vulnerability,” Bredahl has said of Sybilla, a friend and recurring subject. “It’s as if there was always a tear in her eye.”

Michella Bredahl: Rooms We Made Safe at Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, through February 8, 2026

Boris Mikhailov, from the series Yesterday’s Sandwich, 1966–68

Boris Mikhailov, from the series Yesterday’s Sandwich, 1966–68

© the artist and VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn; and courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhailov — London

A towering figure in Ukrainian art, Boris Mikhailov fully embraced photography after being fired from an engineering job in 1969, when the KGB realized he was developing nude portraits of his wife in the factory’s darkroom. It’s a fitting origin story for this inveterate rule breaker, whose photographs of everyday life in Kharkiv—both behind the Iron Curtain and after its collapse—skewer ideology with a bracing intimacy and a sly amateurism. Planned before the Russian invasion, Mikhailov’s largest exhibition to date explores the complexities of Ukrainian identity at a time when the nation is fighting for its future.

Boris Mikhailov: Ukraine Diary at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, through February 22, 2026

Alejandro Cartagena, Carpoolers #21, 2012, from the series Carpoolers, 2011–12

Alejandro Cartagena, Carpoolers #21, 2012, from the series Carpoolers, 2011–12Courtesy the artist

Alejandro Cartagena — San Francisco

Between 2011 and 2012, Alejandro Cartagena waited every morning on an overpass in Monterrey, Mexico, leaning over to photograph day laborers sprawled across various pickup beds, where they read newspapers, scrolled their phones, or napped during their commute into the city center. Carpoolers exemplifies Cartagena’s cumulative, serial approach to visual storytelling, as well as his mix of political critique and deadpan humor. The artist’s first museum retrospective—coinciding with a monograph published by Aperture—reveals the absurdity surrounding border culture, disastrous development schemes, and contemporary image-making itself, lending new credence to André Breton’s claim that Mexico is “the Surrealist place par excellence.”

Alejandro Cartagena: Ground Rules at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, through April 19, 2026

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Untitled (Madonna, plate 34), 1964

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Untitled (Madonna, plate 34), 1964© Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard

Ralph Eugene Meatyard — Atlanta

In 1950, a twenty-five-year-old optician named Ralph Eugene Meatyard bought his first camera, and what started as a way to document his new family led to a tremendous addition to the history of old, weird America. Part of a close-knit creative community in Lexington, Kentucky, Meatyard often photographed his wife and children, who gamely portrayed the figments of his Southern Gothic imagination using masks, dolls, and other props. The prints on view in the High Museum’s The Family Album of Ralph Eugene Meatyard are drawn from a monograph that the photographer assembled at the end of his life—tragically cut short in 1972—and intended as the culmination of his peculiar vision.

The Family Album of Ralph Eugene Meatyard at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, through May 10, 2026

Barkley L. Hendricks, Self-Portrait with Red Sweater, 1980

Barkley L. Hendricks, Self-Portrait with Red Sweater, 1980© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks

Photography and the Black Arts Movement — Los Angeles

Flourishing in the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Arts movement formed a revolutionary cultural front against the marginalization of Black life and art in the United States. This substantial show, curated by Philip Brookman and Deborah Willis, is the first to historicize the role of photography in what is often called the Second Renaissance, whose image makers—among them Barkley L. Hendricks with his pioneering portraiture that venerated everyday Black people—advanced a new visual language of self-representation and community building.

Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985 at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, February 24–June 14, 2026

William Eggleston, Untitled, 1970

William Eggleston, Untitled, 1970Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner

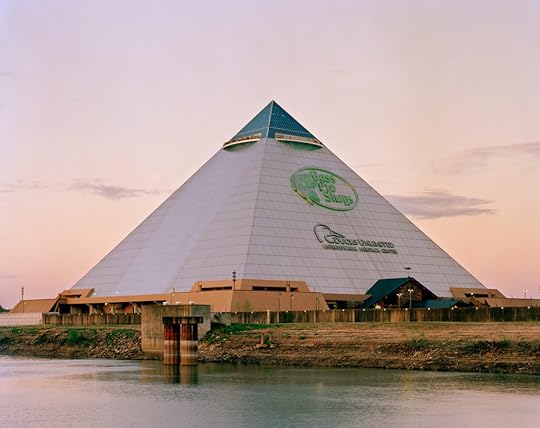

William Eggleston — New York

For a relief from doomscrolling, try The Last Dyes, an exhibition of William Eggleston’s incandescent color photographs from the 1970s. The cars, meals, bedrooms, and gas stations that would otherwise be unremarkable are, in this elegant exhibition at David Zwirner, elevated to icons of Americana, and burned into memory through an extraordinary range of colors. Eggleston ushered color photography into artistic consciousness exactly fifty years ago with his controversial 1976 solo show at the Museum of Modern Art, New York—color being associated, at the time, with the lurid commercialism of print advertising. The toxic and arduous dye-transfer process which Eggleston made famous, and which an explainer on the Zwirner website helpfully illustrates, renders banal scenes both shocking and glorious—a red sweater, a blue ceiling, a sunset like cotton candy. But Kodak stopped making the chemicals in the 1990s, and the works on display are the last of the dyes ever to be made with the remaining supply. The newest iPhone camera has nothing on the experience of encountering these prints in person, each one a vivid dream that’s all too real.

William Eggleston: The Last Dyes at David Zwirner, New York, through March 7, 2026

Jeff Wall, Passerby, 1996

Jeff Wall, Passerby, 1996 © the artist

Jeff Wall — Toronto

It’s hard to overstate the impact of Jeff Wall’s breakthrough pictures: staged narrative photographs mounted in light boxes that, when they debuted in Vancouver in the late 1970s, confounded and thrilled viewers. They still thrill. Exploring memory, war, and everyday life, his post-truth tableaux demand a level of sustained attention vanishingly rare today, each one resulting from meticulous location scouting, rehearsals, multiple shoots, and post-production magic. If visiting this show in Toronto—his first major Canadian survey in twenty-five years—feels a little like going to the cinema, that’s not by mistake. As the artist famously put it, “I guess you could say I’m like a director, but my movies have only one frame.”

Jeff Wall Photographs 1984–2023 at Museum of Contemporary Art, Toronto, through March 22, 2026

Nan Goldin, Greer and Robert on the bed, New York City, 1982, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 1973–86

Nan Goldin, Greer and Robert on the bed, New York City, 1982, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 1973–86Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Nan Goldin — London and Paris

Throughout her career, Nan Goldin has photographed her friends, lovers, and family she made for herself. Her candid, visceral photographs captured a world teeming with life—and challenged censorship, disrupted gender stereotypes, and brought crucial visibility and awareness to the AIDS crisis. First published by Aperture in 1986, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency has had a profound influence on photography and visual culture around the world. Marking the fortieth anniversary of Ballad, two new exhibitions explore its undimmed intensity and towering influence. In London, Gagosian Gallery presents Ballad in full for the first time in the United Kingdom, and later this spring, a retrospective devoted to her videos and slideshows will fill the Grand Palais in Paris.

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency at Gagosian Gallery, London, through March 21, 2026, and Nan Goldin: This Will Not End Well, at the Grand Palais, Paris, March 18–June 21, 2026

Dana Lixenberg,

Tupac Shakur

, 1993

Dana Lixenberg,

Tupac Shakur

, 1993Courtesy the artist and Grimm Gallery

Dana Lixenberg — Paris

Portraiture has been central to Dutch photographer Dana Lixenberg’s documentary practice for more than three decades, and it likewise anchors her latest solo exhibition, American Images. Bringing together work she has made in the United States since the early 1990s, the exhibition spans two floors of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris, and ranges from portraits of pop culture icons such as Tupac Shakur to Polaroid test shots and images from her incisive examinations of race and class, including The Last Days of Shishmaref (2007) and Jeffersonville, Indiana (1997–2004). The museum’s top floor is dedicated to Imperial Courts (1993–ongoing), a body of work begun in the 1990s about the residents of a Los Angeles housing project, to which Lixenberg continues to return today.

Dana Lixenberg: American Images at La Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, February 11–May 24, 2026

Janna Ireland, Struckus House, Number 11, 2024

Janna Ireland, Struckus House, Number 11, 2024Courtesy the artist

Janna Ireland — Chicago

Janna Ireland: A Goff House in Los Angeles explores the last residential project designed by visionary American architect Bruce Goff. Ireland’s photographs delve into the origin story of the Al Struckus House, commissioned in 1979 for the engineer, woodworker, and art collector Al Struckus. Located in Woodland Hills, in northwestern Los Angeles, the four-story cylindrical structure features organic elements, from radical floor joists to rotating circular closets, that create an open yet dizzying atmosphere, reflecting the architect’s eccentric flair as well as the personality of its owner. As Ireland notes, the house is “organic and singular in form, it is a shining example of Bruce Goff’s design philosophy, moving forward through time unimpeded, always somehow in the ‘continuous present.’” The exhibition complements the retrospective Bruce Goff: Material Worlds, also on view this spring at the Art Institute.

Janna Ireland: A Goff House in Los Angeles at the Art Institute of Chicago through May 18, 2026

Nuits Balnéaires, Le Messager 8, from the series Eboro, 2025

Nuits Balnéaires, Le Messager 8, from the series Eboro, 2025© the artist

François-Xavier Gbré, Rubino, from the series Radio Ballast, 2024

François-Xavier Gbré, Rubino, from the series Radio Ballast, 2024© the artist/ADAGP, Paris

Nuits Balnéaires and François-Xavier Gbré — New York

In Latitudes, two distinctive yet complementary photographers present meditations on memory and place in Côte d’Ivoire. François-Xavier Gbré, who was born in France and has worked across West Africa, is known for his precise examination of how architecture forms a living archive of a country’s aspirations. His newest series, Radio Ballast (2025), follows a rail line that connects Abidjan to Niger. He spent a year photographing its aging infrastructure: train cars, stations, and rusted track, against the backdrop of the verdant Ivorian landscape. Nuits Balnéaires is a Grand-Bassam–based visual artist who began his career in the fashion industry. His work explores the multicultural nature of Côte d’Ivoire’s southeastern shores and its deep connection the environment. Inspired by the Nzima and Agni-Bona people’s belief in a return to a single human origin at the end of life, his series Eboro (2025) takes viewers on a metaphorical journey to find his ancestors—and himself. The rich, cinematic palette of colors in Eboro evoke nostalgia and quiet longing. Together, these works offer a remarkable look at how Côte d’Ivoire’s past—spiritual, cosmological, and ecological—seeps into its present.

Latitudes: Nuits Balnéaires and François-Xavier Gbré at the International Center of Photography, New York, through May 4, 2026

January 30, 2026

John Chiara Illuminates the World’s Simple Mysteries

Some three hundred years ago, the Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico came to a humble conclusion that still startles today—that one can understand only what one makes. Perhaps it’s true to say that the claim grows only more astonishing as the centuries accrue and technology evolves at such a breakneck pace that very few, if any of us, make anything for ourselves anymore. The paradox baffles the mind (or does so if we take Vico at his word): in the twenty-first century, when any one of us has in the palm of our hand all the knowledge the world possesses, we are secretly immersed in a new dark age. We know it all, but we understand none of it. The “cloud” memorizes the images we take, a strange archive of experiences we ourselves have lived, edited, and filtered, accessible when we want to remember what it is we’ve lived—a life, or a kind of life. Proof we were there, wherever there is, digitized and stored away and shareable. . . . But I’m haunted by the suspicion that not one image of it all is a thing we’ve made, truly made, ourselves.

John Chiara and his camera, Treasure Island, August 2025. Photograph by Tom Bollier for Aperture

John Chiara and his camera, Treasure Island, August 2025. Photograph by Tom Bollier for Aperture

It’s a bleak thought, but one that must be confessed, that our own life is something we don’t understand—one that must be addressed, to see an art such as John Chiara makes. Since the age of sixteen, Chiara has maintained a darkroom, a way of developing for himself the images he’s taken, but a process ornate enough that he began to suspect it interfered with the direct experience of vision and memory driving his artistic inquiry.

He sought another way, one that is extraordinarily labor-intensive: Chiara builds the cameras he uses, and they’re large. Imagine a Hasselblad box magnified to the size of a small house, towed on a trailer behind a truck and in which the photosensitive paper on which the image is made is put in the camera by stepping inside the camera itself. These cameras reach back through time to the beginnings of the art form itself, the camera obscura, light inverted through a lens and the upside-down image cast back onto the paper for hours. The handmade camera invites in leaks of light and breeze as an inherent part of a process that seeks anything but to be merely in control.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Not simply a framer of a scene, Chiara is an experimenter in time, calling into question vision’s instantaneousness, showing us the eye entangled with light by which it sees, light that the photograph puts on miraculous delay—a delay that feels to me nearly philosophic, almost metaphysical, attuning us to awe and error, making seeing itself something we can no longer take for granted, a reinitiation into the mystery in which we live the hours of our wakeful lives. In photographs larger than our own bodies, a perspective that quietly quickens the child within us, is that fear and marvel of feeling how small one is in relation to all that’s in the world, a fact the adult too easily forgets.

A gift initiated Chiara into his work, a camera his father gave him when he was eight years old—a Nikon the family couldn’t really afford. Rather than promoting a separation from the world, the camera became for Chiara a tool of intimate entanglement with it, as if the lens with its auto shutter taught the child the nature of his own eye. Chiara goes back to those earliest photographs, “the ones of birds far distant in trees or cats rolling on garden hoses and close-ups of grass,” and feels a worthy pride. His work has taken him across the nation and abroad, from his native California, where his love for his art first was fostered, to a recent residency in Georgia.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

But it’s Northern California, where he trained his eye to see the world around him, that continues to exert a touchstone fascination, as if he hasn’t yet seen what he means most to see. I find myself returning to the series Treasure Island (2020–24), sepia in tone but more golden, full of ancient honey, of the bay and San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge. The sun’s light tunnels through the water. The water gleams with a gathered glow the foreground stones of the shore can’t claim. And in haunted silhouette, the cityscape and the lacework bridge, temporary witness to a process of light and substance that has existed as long as light and substance themselves have existed, and will outlast any witness to them. This series focuses on Treasure Island, a landmass as handmade, in a certain sense, as Chiara’s cameras, and sharing their exceptional scale. Built from 1936 to 1937 to host the Golden Gate International Exposition, Treasure Island has gone from world’s fair site to World War II naval base to residential, shifting from monthly rentals to million-dollar condos. What shade is there is cast by nonnative trees: palms, eucalyptus, Italian cypress. It’s a strange thing—how place teaches us how to see.

Chiara teaches us to see through the handmade humility that returns to the world its proper wonder. He attunes us to the made-ness of made things—the chromed phantasmagoric spectacle of the metal stands that hold the ropes that mark the lines we wait in; a mooring block of concrete; homes and buildings and the wires and poles that send the electricity that lights the lights within them. Chiara also enlivens us toward the facts of all it is we can’t make ourselves: sunlight, water, land; eyes, mind, life. It puts in my heart a feeling I want to call azure—which doesn’t assure, but describes some instant of the evening sky. Or is it the early morning sky? Either way, Chiara has given us a craft to navigate the terrain: a way of making, and a making that transports us through.

All photographs by John Chiara from the series Treasure Island, 2020–24

All photographs by John Chiara from the series Treasure Island, 2020–24Courtesy the artist

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue.”

January 23, 2026

The Woman Who Immortalized the Bauhaus

“I want to tell you that we are on unfriendly terms with her lately and that she has even brought or intends to bring a suit against Walter for having kept her Bauhaus photographs to himself. There are hard feelings on both sides,” wrote Ise Gropius, wife of Walter Gropius, the German architect and founder of the Bauhaus art and design school, in a 1956 letter to a friend who was hosting a dinner in his honor in London. Ise Gropius was eager to ensure that “she” would not be invited.

“She” was Lucia Moholy, the Czech-born photographer whose mid-1920s images of the Bauhaus campus designed by Gropius in the German city of Dessau have long been regarded as archetypal depictions of the modernist aesthetic. Her precise, beautifully composed photographs of the school’s architecture, students, teachers, and their work still define our perceptions of the Bauhaus as a progressive, empowering bastion of cultural and social idealism. They swiftly became more famous than the woman who made them.

Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus workshops, chess table by Heinz Nösselt with pieces by Josef Hartwig, 1924

Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus workshops, chess table by Heinz Nösselt with pieces by Josef Hartwig, 1924Courtesy Galerie Derda, Berlin

László Moholy-Nagy, Head (Lucia Moholy), ca. 1926

László Moholy-Nagy, Head (Lucia Moholy), ca. 1926© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Lucia Moholy: Exposures, an exhibition presented in 2024 at Kunsthalle Prague, in the Czech Republic, and at Fotostiftung Schweiz, in Winterthur, Switzerland, this past spring, sought to change that by exploring the full scope of Moholy’s work in writing, editing, and documentary filmmaking as well as photography. But why was such a gifted and charismatic woman overlooked for so long? And why, for much of that time, was she not credited for her most important body of work? The answers lie in the misogyny and geopolitical turmoil of mid-twentieth-century Europe.

Born Lucie (she later changed her name to Lucia) Schulz to nonpracticing Jewish parents in Prague in 1894, she had a comfortable childhood thanks to her father’s successful law practice. As part of the first generation of European women (albeit only wealthy ones) to be encouraged to attend university, she qualified as a German and English teacher in 1912, then studied philosophy and art history at the University of Prague. After spending much of World War I in Germany, first in Wiesbaden, then Leipzig, she settled in Berlin and worked in book publishing while writing experimental literature under the male pseudonym Ulrich Steffen. By then, she was part of an avant-garde group of intellectuals, artists, and activists who were devotees of a Mazdaznan sect, which advocated meditation, strict vegetarian diets, and a bracing exercise regime of wild swimming and hiking in the countryside.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

In 1920, Schulz fell for a recent arrival to Berlin, a young Hungarian artist and activist named László Moholy-Nagy. A few months later, they married, and she changed her surname by adopting the first part of his, becoming Lucia Moholy. At the time, László was focused on applying his work in painting and collage to securing radical political change. During their country walks, he began experimenting with photography, then widely dismissed as being too sentimental and commercial to have cultural value. Lucia contributed heavily to his program for what he called a “new vision” and swiftly developed photographic concepts and techniques of her own. As well as collaborating with László to create photograms by printing images of objects, or their shadows, on photographic paper, she explored innovative ways of presenting daily life using a camera. They both believed that photography was an exciting means of documenting the speed and urgency of modern life, and its dangers.

Subsisting on her modest wages, they had so little money that they could not afford to heat their apartment in the brutally cold Berlin winter. Their fortunes changed after the success of a 1922 exhibition held at Der Sturm gallery in Berlin, which included László’s “telephone pictures,” made by a sign factory in accordance with instructions he relayed by phone. Among his new admirers was Walter Gropius, who was so impressed by László’s intellectual vigor that he invited him to teach at the Bauhaus, which was then in Weimar.

Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus Dessau, workshop wing from the southwest, 1926

Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus Dessau, workshop wing from the southwest, 1926© ProLitteris, Zurich, and courtesy the collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus Weimar, director’s office, 1923

Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus Weimar, director’s office, 1923© ProLitteris, Zurich, and courtesy the collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

When the couple arrived in 1923, the four-year-old Bauhaus was in chaos. Under attack by conservative local politicians, who derided it as a hotbed of subversion and depravity, it was still scarred by a long-running conflict between Gropius and a charismatic teacher, Johannes Itten, who favored a mystical approach to art and design education. As Itten ran the foundation course, which was compulsory for all incoming students, he exercised considerable influence until Gropius ousted him in 1922.

Gropius hired László to replace Itten, judging correctly that he would have a very different vision for the school. László reinvented the Bauhaus in accordance with Constructivist principles by urging the students to deploy art, design, science, and technology to improve the lives of the masses. He also allowed women to study the same subjects as men, rather than being relegated to supposedly “feminine” courses, principally weaving.

Unlike many “masters’ wives” who were uninvolved with the school, Lucia played an active role at the Bauhaus, notably in her unofficial capacity as resident photographer.

As for Lucia, she began a two-year apprenticeship with the photographer Otto Eckner, who was then responsible for documenting life at the Bauhaus. When the school moved to Dessau in 1925, she enrolled in photography classes in nearby Leipzig, and set up a darkroom where they could continue their experiments in their home, one of the tellingly named “Masters’ Houses” designed for Gropius’s almost all-male teaching staff.

Unlike many “masters’ wives” who were uninvolved with the school, Lucia played an active role at the Bauhaus, notably in her unofficial capacity as resident photographer. Her still lifes of objects designed by the students—including Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel B33 chairs, Marianne Brandt’s silver and ebony teapot, and a corsage made by the Bauhaus weaver Gunta Stölzl—defined a radically new style of industrial photography. Using primarily an old plate camera for 18-by-24-centimeter glass negatives, she made the object the sole focus of the image, always positioning it against a neutral backdrop. As the design historian Robin Schuldenfrei noted in a 2013 essay, “The products’ modernity is underscored in the photographs themselves: in the shiny reflective surfaces, lit so that they gleam but do not over-reflect.”

Lucia Moholy, Set design by László Moholy-Nagy for The Tales of Hoffmann, Kroll Opera, Berlin, 1931

Lucia Moholy, Set design by László Moholy-Nagy for The Tales of Hoffmann, Kroll Opera, Berlin, 1931© ProLitteris, Zurich, and courtesy the collection Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur

Lucia Moholy, Corsage for a Bauhaus festival by Gunta Stölzl, 1926

Lucia Moholy, Corsage for a Bauhaus festival by Gunta Stölzl, 1926Courtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Lucia applied a similar methodology when documenting the evolution of the Bauhaus Dessau, starting with its construction before focusing on each completed element, including the learning spaces, theater, canteen, student apartments, and teachers’ houses. Each of these immaculately composed photographs was taken in a painstakingly planned, seemingly dispassionate style that depicted the school as a series of stage sets, devoid of people. (Lucia also photographed the stage sets designed by László at Berlin’s Kroll Opera House.) They convey a sense of elegance, modernity, and discipline that has defined the Bauhaus, and modern glamour, ever since.

Her portraits from this period share many of those qualities, not least by tightly cropping her subjects’ faces to emphasize nuances of their characters while forging a rapport between them and the viewer. In her 1939 book A Hundred Years of Photography 1839–1939, Lucia cited the extreme close-ups used by Sergei Eisenstein and other avant-garde Russian filmmakers as an inspiration, despite the misgivings of some of her subjects. “They find it interesting and worth discussing,” she wrote, “but few of them wish to have their portraits taken in the same way.” Tellingly, many of her most cooperative sitters were women, often friends, such as the German photojournalist Edith Tschichold and the New York–born artist Florence Henri, who arrived at the Bauhaus as a painting student, only for László and Lucia to convert her to photography.

Cover of Lucia Moholy, A Hundred Years of Photography, 1939

Cover of Lucia Moholy, A Hundred Years of Photography, 1939Courtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Equally enthusiastic were the occupants of Schwarze Erde, a feminist commune in the Rhön Mountains where Lucia often stayed. Like her, they were ambitious, highly educated Neue Frau, or New Women, who had thrived in pre-Nazi Germany. Lucia captured their strength and dynamism but also their idiosyncrasies in seemingly spontaneous photographs that contrasted sharply with her Bauhaus Dessau still lifes and architectural images. She was equally playful in a mid-1925 portrait of László dissolving into laughter while raising a hand toward the camera, as if to stop her from proceeding.

Lucia’s role as the Bauhaus’s unofficial photographer gave her a sense of purpose at a time when she felt increasingly unhappy with her life there and her marriage. “I simply can’t stand it anymore,” she wrote in her diary on May 27, 1927. “I need something that I’m not finding here.” She and László left Dessau and returned to Berlin the following year. It was a welcome change for Lucia, who relished being back in a big, culturally dynamic city. Resuming her photographic experiments, she participated in exhibitions. After she and László separated in 1929, she taught photography at a Berlin art school run by Itten.

By then, Lucia was approaching photography almost as a craft, though not in a conventional sense. She regarded industrialization as an indispensable tenet of modernism, as did her friends. As a result, most Bauhaus teachers and students were committed to designing for serial production, and succeeded in persuading like-minded German companies to mass-manufacture the furniture, ceramics, glassware, textiles, and other products developed at the school. The industrial element of photography was part of its appeal to Lucia, yet the deeply personal nature of her experiments in the darkroom, not least in devising ingenious ways of printing her photographs by hand and of producing images as photograms without recourse to a camera, evokes the intimacy and idiosyncrasy of craftsmanship.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

As the Nazi Party gained power in Germany, Lucia’s position as a foreigner, a Jew, and an activist made her increasingly vulnerable. It became untenable in August 1933 when her lover Theodor Neubauer, a Communist politician, was arrested at her home and imprisoned for subversion. (They never met again, and he was executed in February 1945.) Terrified, she fled to Prague to join her family, leaving her possessions in her Berlin apartment except for her archive of prints and 560 glass-plate negatives, which she entrusted to László and his new partner, Sibyl Pietzsch, whom she had befriended.

Over the next few years, Lucia moved to Switzerland, Austria, and France before settling in London, where she combined photography with writing, culminating in 1939 with the publication of her book, A Hundred Years of Photography, one of the first histories of the medium in English. She also continued to work in portraiture by documenting politicians, academics, authors, artists, and other influential Britons, ranging from the peace activist Ruth Fry to the socialite and anti–women’s rights campaigner Margot Asquith.

It would have been easier for Lucia to forge a career in photography after leaving Germany if she’d had her Bauhaus Dessau images. When World War II began, she applied for a US visa, supported by László and Sibyl, who arranged for her to be employed at his recently opened design school in Chicago, and invited her to stay in their home. Yet her application was rejected, so she remained in London. After the war ended in 1945, she asked László to return her archive. He explained that he had given it to Gropius for safekeeping before he and Sibyl left Berlin. Unbeknownst to László, Gropius had shipped it to the United States with other Bauhaus artifacts in 1937, when he began an academic career at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

László Moholy-Nagy, László and Lucia, ca. 1923. Reproduction copy printed in 1979 by Lucia Moholy

László Moholy-Nagy, László and Lucia, ca. 1923. Reproduction copy printed in 1979 by Lucia MoholyCourtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus workshops, table lamps by Carl Jakob Jucker and Wilhelm Wagenfeld, ca. 1924

Lucia Moholy, Bauhaus workshops, table lamps by Carl Jakob Jucker and Wilhelm Wagenfeld, ca. 1924Courtesy Galerie Derda, Berlin

All works by Lucia Moholy © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. All László Moholy-Nagy works © Estate of László Moholy-Nagy/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Given the turbulence of the time, neither man behaved unreasonably. The problem was that Gropius then used her “Bauhaus photographs” in numerous projects, without asking her permission or crediting her. He made the same omissions when releasing her images for use by others. When Lucia wrote asking him to send prints for her to screen in a lecture, he advised her to contact a British architecture journal instead. She then discovered that he was also storing her negatives, which, until then, she believed had been destroyed, and demanded their return with compensation, eventually hiring the lawyers described in Ise Gropius’s letter to help her. In 1957, after three years of fraught negotiations, Lucia recovered most but not all of them. Two years later, she left London for Switzerland, where she lived until her death in 1989, writing on art and the Bauhaus.

Plucky, resourceful, and talented, Lucia Moholy was a remarkable woman who led an extraordinary life. Why is her work better known than she is? A prime factor was misogyny. Like all gutsy Neue Frau, she faced gender discrimination at every turn. She had been lucky in marrying such an enlightened man as László, but her early photographs were routinely misattributed to him. Like him and many of their friends, she faced repeated struggles to rebuild her life in various countries during the turbulence of Nazism and World War II, but for her, those challenges were aggravated by anti-Semitism. She was also unlucky in facing such a powerful, well-connected opponent as Gropius. Lucia emerged victorious, but only after a long, painful battle. A cruel irony is that had the archive remained in his Berlin house, as László and Sibyl intended, it would have been destroyed when the building was bombed during World War II. And had Lucia kept it after leaving Berlin, it would have suffered the same fate, as her first London apartment was ravaged by fire during a 1940 air raid. In either scenario, those precious Bauhaus photographs would have been lost.

This essay originally appeared in Aperture No. 261, “The Craft Issue.”

Fashion Photography’s AI Reckoning

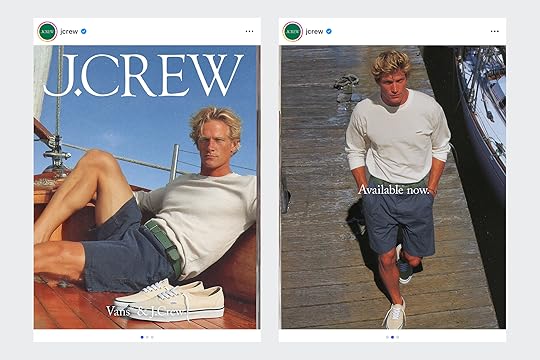

Last year, a J.Crew campaign promoting the company’s collaboration with Vans roiled certain corners of the internet concerned with the sanctity of menswear. The images seemed at home for a brand built on the signifiers of blue-blooded Americana: a barrel-chested WASP lolling on his daysailer, his flaxen hair swept back in perfect dishevelment, his jawline cutting perfect Harvard crew-team symmetries. Except there were some peculiarities. The contours of that jawline had dramatically realigned themselves in the time it took for him to dock. Other conspicuous glitches: the stripes of a rugby polo fuzzed into static, a foot implausibly torqued. The initially uncredited campaign was judged to be AI-generated. J.Crew eventually admitted it was the work of Sam Finn, a London-based AI image maker who, with presumably little irony, goes by “AI.S.A.M.”

To devotees of the mall brand’s “vintage” 1980s aesthetic (Ivy League, Nantucket, Caucasian) referenced by these images, the choice felt like a betrayal. Here was a brand cannibalizing its own history, sloppily regurgitating it and feeding it back to consumers like some malformed lunch meat. Worse, it was a machine making a mockery of their nostalgia. Their self-styled taste was revealed to be so flat as to be replicable by algorithm.

“I think the thing that mostly annoys people about AI is it’s sometimes really good and sometimes really bad,” Charlie Engman, a photographer whose engagement with AI straddles commercial and art practices, told me. “It fails a lot, and I think the failures are actually very instructive and tell you what we care about. And then when it succeeds people get upset because then they feel manipulated.”

Screenshots of J.Crew Instagram

Screenshots of J.Crew Instagram  Screenshots of J.Crew Instagram

Screenshots of J.Crew Instagram The debacle was similar to one a month earlier involving a Guess ad in the August edition of Vogue, a two-page spread featuring a lissome model dressed in two looks from the brand’s summer collection. Here, too, there were inconsistencies: The model’s face subtly morphed across the images, her skin giving off the plasticized matte finish native to residents of the uncanny valley. This time, though, Guess wasn’t trying to fool anyone. In small print at the top of the page appeared the words “Produced by Seraphinne Vallora on AI.”

In both these cases, the images were realistic, that is, they spoke in the language of photography—naturalistic lighting, figures that credibly read as human. Objectors (there were plenty) noted the bitter irony of billion-dollar companies undercutting skilled labor to produce something that looked like what they normally do anyway. In fact, that was less ironic than the entire point.

The idea that advertising is unscrupulous is by now well understood. Fashion advertising in particular has a well-recorded history of emotional and technical deception. More than a decade ago, Photoshop caused an epistemological crisis—suddenly the waistlines of models in advertising and consumer magazines shrank to unnatural degrees, and cheek fat dissolved with the swipe of a cursor, leaving so much body dysmorphia in the wake of the healing brush tool. Even celebrities—the already beautiful—were not immune to the retoucher’s gaze. The boundaries of visual reality were compromised. The public learned that photographs could now lie, and probably were lying.

Edward Steichen, Ad for Coty Lipstick, ca. 1930

Edward Steichen, Ad for Coty Lipstick, ca. 1930Courtesy Whitney Museum of Art and Scala/Art Resource, NY

The fashion image’s elastic relationship with truth stretches further back than the advent of Adobe software. Artifice was part of the deal from the beginning. Edward Steichen, the godfather of commercial fashion photography, introduced tricks of lighting, focus, and long exposure to manipulate the texture of fabric or flatter a face. As technology has become more sophisticated in pursuit of the same goal, AI’s total artificiality is, in many ways, more honest. Andrea Petrescu, the twenty-five-year-old cofounder of Seraphinne Vallora—the marketing agency behind the Guess ad—articulated, perhaps inadvertently, a philosophical loophole. “We don’t create unattainable looks,” she told the BBC. “Ultimately, all adverts are created to look perfect and usually have supermodels in, so what we are doing is no different.” The fashion industry, long maligned for promoting unattainable standards of beauty, would seem to reach its logical endpoint in AI: a standard of beauty that cannot be accused of being unattainable, because the beautiful people don’t exist.

The idea that advertising is unscrupulous is by now well understood. Fashion advertising in particular has a well-recorded history of emotional and technical deception.

From a world-historical view, AI is simply the latest entry in industrialized automation. The increasing accessibility of AI tools means what once took dozens of specialized roles can now be achieved (or approximated) by one person clicking around in Midjourney. Some of the most conspicuous uses of AI in advertising have been commissioned by multimillion-dollar companies, which by their nature must adhere to capital’s ruthless logic. Finn, for instance, is credited with AI imagery for mass-market apparel brands like Ugg and Skims that is, like his J.Crew work, relatively tame compared to the nightmarish stuff he’s cooked up for Alexander McQueen (gargantuan beetles) and Gucci (a psilocybin-soaked AI sequence shoehorned into last year’s The Tiger, a bizarre fever-dream-as-brand-showcase directed by Spike Jonze and Halina Reijn and starring Demi Moore). For brands that wish to telegraph an edgy persona, AI reads like shorthand, if not compulsory.

Laura Dawes, a director at the London office of Webber Represents, a creative agency that manages photographers as well as stylists, set designers, and art directors, told me that navigating demand for AI is an evolution of what she’s always done as an agent, which is to manage expectations. “The thing about artists is that everyone is so unique,” she said. “I’ve had some really embrace it, and that’s usually in a controlled studio setting, something that’s more, say, constructed. But then in an uncontrolled environment, with natural light, that can be quite hazardous.” Dawes said she has seen clients use AI to build mockups for campaigns, which invites an intolerable level of risk: “You’re making an artificial image and using that as a guide and selling that to stakeholders on set when it’s not physically possible.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Commercial adopters of AI are seduced less by the technology’s supposed mystique than by its labor efficiencies. It’s a short leap from fast fashion’s already algorithmic enterprise to AI’s promise of cost optimization. A recent report from the International Advertising Bureau projects that generative-AI creative will reach 40 percent of all ads beginning this year, confirming what anyone who watches YouTube videos or regularly rides the subway could already predict. It’s easy to see why AI would appeal to J.Crew, a company that filed for bankruptcy in 2020 and seems to be working through a prolonged identity crisis. “In a way, you can’t fault companies like Guess or J.Crew for doing this, because it’s just following profit models that have always existed,” Engman said. “Having worked in a lot of these jobs, you know, the creativity is very marginal. From a conceptual standpoint, it’s like, yeah, sure, make the J.Crew catalog.”

“Like it or not, this technology is here,” said Kalpesh Lathigra, who teaches in the MA commercial-photography course at London College of Communication. Lathigra, an artist and documentary photographer who also works commercially, believes that the industry will see what AI can do, but more importantly, what it cannot. “Personally, I’m not interested in AI. I would much rather get out into the world. A machine can give you millions of possibilities, but it can’t give you that elusive, intangible thing that draws us in and holds us, which has remained the same since the dawn of photography.”

Charlie Engman, AI-Generated Image for Acne Studios, 2023

Charlie Engman, AI-Generated Image for Acne Studios, 2023  Charlie Engman, AI-Generated Image for Gucci, 2023

Charlie Engman, AI-Generated Image for Gucci, 2023 Photographers and models, the image-industry jobs with the largest cults of personality, may be at less risk than less visible technical roles. “The people that I’m most worried about are the set designers,” Engman told me. “That’s the job that I feel is already disappearing.” Those roles are being supplanted by the elevated presence of retouchers, some of whom have cannily rebranded themselves into what Engman refers to as AI consultants, “which is a very interesting thing, because historically, retouchers were not seen as a particularly creative part of the process.”

There’s general resignation to the idea that AI is hastening entropy in a certain part of the medium. “The race to the bottom I feel will only apply to the basics of image-making—what was once referred to as ‘pack photography,’ home catalogs, basically, but today is product imagery for e-commerce,” Lathigra told me.

Dawes agrees. “When friends of mine were entering the industry, there were a lot of entry-level gigs mainly based around e-commerce, where people could do those kinds of jobs and have the ability to shoot their personal work on the side,” she said. That was only a decade ago. “Now there are brands producing all of their e-com in AI. That for me is quite scary, because that’s such a large section of the industry.” Dawes said she now routinely deals with clients whose entire catalog of product photography is AI-generated.

Engman, who has shot for Prada and Gucci, was an early AI adopter, starting to play around with AI models in 2022. He has an openness toward its possibilities that other photographers might not. It’s an openness that has made him sought-after in the fashion world as an AI oracle; he seems to talk about AI as much as he uses it. A couple of years ago, he estimated that 80 percent of his work engaged AI in some way, like a campaign for Acne that featured statues of vaguely humanoid figures who had seemed to ossify into seashells while shopping. He puts his current AI output vis-à-vis commissions much lower. Did he get bored, or is the flawlessly formed surface of AI’s bubble already deflating?

Screenshot of Vogue Instagram, December 2025 cover

Screenshot of Vogue Instagram, December 2025 cover“I felt like I was participating in the bubble a few years ago, and now I think we’re in the awkward growing pains of moving out of the bubble,” he told me. Engman recalled a recent shoot with Coach, which had commissioned him based on his AI work but then realized that wasn’t actually what it was interested in. “What they wanted to do was much easier and more effective to do in CGI,” he said.

The taste of AI has already coated our mouths enough that it may not matter if it’s actually present at all. Vogue’s December 2025 cover features an image of the actor Timothée Chalamet dressed in Celine jeans, cream topcoat, and untied motorcycle boots, inexplicably posed on top of a swirling nebula. It calls to mind the kitschy roll-down backdrops of school picture day. The portrait, shot by the perennial Vogue contributor Annie Leibovitz, is not AI, but with its disproportionate scaling and goofy premise, has the same acrid aftertaste. In many ways, that’s worse. If we’ve reached the point where humans are aping machines aping humans, especially unconsciously, we’re further down the valley than we realize.

The Hardcore Optimism of Milo Keller

Milo Keller loved the word hardcore. He used it when we interviewed candidates for the graduate photography program at the University of Art and Design Lausanne, Switzerland, or ECAL. He would lean forward with a half-smile and say, “This course is hardcore. Are you ready for it?” The faces across the table often looked puzzled, sometimes even afraid. But for Milo, hardcore was never a threat. It was a mantra. It meant curiosity pushed beyond comfort, work carried further than most people thought possible, and ideas pursued until they opened something genuinely new. Hardcore was not a pose. It was the way he lived.

Milo died in December 2025. I first met him in the early 2010s, when we ended up in a pub in London. Milo kept buying rounds, refusing to let the night end. At some point I begged the bartender to serve me water in a shot glass, secretly, just so I could stay afloat. But what defined Milo was not his excess, even if his parties became legendary. It was the morning after, when he would show up in Lausanne to start teaching at eight. Work hard, play hard.

Milo Keller, 2023

Milo Keller, 2023Courtesy ECAL

Milo was born in 1979 and raised in Ticino, the Italian-speaking canton of Switzerland. I interviewed him recently for a forthcoming book (Views on Things, produced with Jörg Boner), and he spoke about being raised by a Swiss German father—an architect, rational and disciplined—and a Catholic mother with strong ties to Italy, associated with warmth, sociability, and openness. It was not conflict but a coexistence of two worlds that he learned to hold together. He recognized that same duality throughout his life and work: discipline and openness, planning and intuition, order and chaos.

As a photographer, Milo spoke about images as “spaces to be resolved.” His work began with an architectural sense of order—volumes arranged, lines stabilized, compositions built with deliberate precision. Once an image felt too resolved, he felt compelled to unsettle it. His photographs exist in a fragile equilibrium, where structure is never complete without disturbance, humor, and, at times, eroticism. That sensibility also shaped his engagement with places like Ivrea, where the architecture of Olivetti’s abandoned offices sits between modernist social idealism and decay.

Milo was first a student at ECAL, and in 2012, he was invited back to lead the BA in photography; in 2016, he established the MA Photography program. In these roles, he shaped the department around a pedagogical framework that was strict, structured, and work-driven. Students were expected to be present from early morning until late afternoon, and Milo insisted on an intensive rhythm of classes, workshops, production periods, and critiques. Technical competence, reliability, and discipline formed the foundation. It was precisely because he built such a defined framework that experimentation became possible. Inside that structure, he encouraged students to introduce uncertainty, accident, and risk into their work. He was drawn to candidates with temperament and character rather than polish, and he brought in practitioners working with emerging tools and approaches, including photogrammetry, CGI, sculpture, moving image, virtual and augmented reality, and, more recently, artificial intelligence. The framework was his method; the space inside it was playful and unpredictable.

The aesthetic that emerged around the program during his tenure is often described as “ECAL style.” The images are precise and controlled, built through staging, careful lighting, and refined production values—a visual clarity that carries traces of advertising and studio language, even when the work moves into documentary or fine art. He was uneasy with the idea that a school might be reduced to a look, and he knew how many former students worked far outside that vocabulary. But the style exists, and it has become widely recognizable. Whether he embraced it or not, it remains part of his legacy.

Installation view of Automated Photography, FotoIndustria, Ex Chiesa di San Mattia, Bologna, October–December, 2023

Installation view of Automated Photography, FotoIndustria, Ex Chiesa di San Mattia, Bologna, October–December, 2023Photograph by Mahalia Taje Giotto. Courtesy ECAL

Alongside teaching, Milo also developed a research program within the department, conceived as a laboratory devoted to critical and collective inquiry. Each cycle begins with a question about the future of the medium and unfolds through workshops, prototyping, and discussions with students and invited artists and thinkers, extending into traveling exhibitions, publications, and online platforms. Augmented Photography (2016–17) explored the status of the photograph and its production in a post-photographic era, when images become malleable data. Automated Photography (2019–21) weighed the effects of automation and computation on production and authorship. The current project, Soft Photography, focuses on the emotional stakes of images generated by artificial intelligence, pointing toward a future that many approach with uncertainty and anxiety.

Across this work, the question of where photography may be heading remains central. While much of the field tends to meet technological change with apprehension, Milo approached such transitions differently. He treated them as opportunities to think, test, and work, engaging with them inside the space of education. His optimism was not naive. It was grounded in practice and in the belief that the medium could always be expanded and challenged head-on. That same attitude shaped his relation to students. He believed that each of them contained possibilities beyond what they imagined for themselves, and he pushed them toward those thresholds with forcefulness and trust.

Milo Keller leaves behind photographs, research, exhibitions, and the achievements of many former students. But more than any single body of work, his legacy lives in this hardcore optimism: a conviction that the medium can still change, and still matter, that individuals can exceed their own expectations, and that possibility is something to be acted upon. It is an optimism directed at humanity, and it resonates with particular urgency in the moment we are living in now.

January 16, 2026

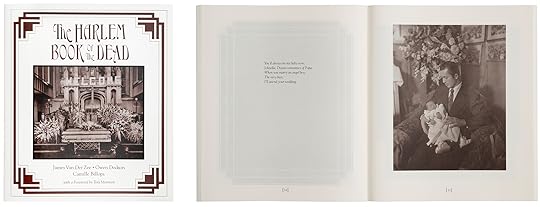

Bringing “The Harlem Book of the Dead” Back to Life

James Van Der Zee and Garrett Bradley were born nearly one hundred years apart. What unites them across the snap of a century is a deft capacity to make visual hymns of Black life with their cameras, without overdetermining the lyric of that living. It’s fitting, then, that Van Der Zee’s The Harlem Book of the Dead—first published in 1978 and out of print for nearly fifty years—sees a second coming at the behest of Bradley, the artist and director celebrated for her Oscar-nominated 2020 film Time, in the form of a facsimile edition.

A dwelling place for Van Der Zee’s funerary portraits, The Harlem Book of the Dead encircles the deceased with a chorus of voices: an interview between Van Der Zee and Camille Billops, who conceived the original text; poetry by Owen Dodson; and a foreword by Toni Morrison. As managing editor of the reissued edition, Bradley retained the original contributions as well as Billops’s approach to polyvocal book-making, commissioning a new afterword by Dr. Karla Holloway, who writes: “Van Der Zee is speaker for the dead. . . . These images secured the souls of Harlem’s Black folk.” As speaker and “securer,” Van Der Zee and his images attend to the belief that death is not an end, nor a terminal point, but rather a threshold, a passageway interminably open on both ends. By exhuming his elegiac photographs alongside the liturgy that cradles them, Bradley carries forward a longstanding Black tradition in which the living are called to caretake the desires of the dead.

Cover and interior spread of The Harlem Book of the Dead (Primary Information, 2025)

Cover and interior spread of The Harlem Book of the Dead (Primary Information, 2025)Camille Bacon: What was your first encounter with The Harlem Book of the Dead and Dr. Karla Holloway, who authored the facsimile edition’s afterword?

Garrett Bradley: I was taking Professor Kevin Quashie’s class Death and Dying at Smith College, which introduced me to Karla Holloway’s book Passed On: African American Mourning Stories (2002), which begins with her own personal experiences with grief. From there, it builds into a set of queries that brings readers into the history of Black death and dying in America over the course of a century.

Holloway contextualizes Van Der Zee’s work in particular within the early 1900s and mid 1920s as running parallel to the Red Summer of 1919, the high child-mortality rates in New York City because of the rise in tuberculosis and pneumonia, and eventually both world wars. In the same way that Van Der Zee took a radical approach to his subject matter, mourning and death, Holloway was also introducing us to a new way of understanding the personal alongside the historical. Both bodies of work—The Harlem Book of the Dead and Passed On—propose the impossibility of separating personal grief from the collective experience of grief. Our proximity to it may begin intimately, but what happens next, our journey through it, our attempts to do something with it, are a universal pursuit. I owe a great deal to Quashie for opening that door for me as a student and then introducing Karla and I years later. Karla and I have since become good friends and are in the process of adapting Passed On into a new body of work.

The process of conducting research for the adaptation of Passed On is also what brought me to The Harlem Book of the Dead. It was originally published in 1978 by Morgan & Morgan. When they closed their doors shortly after the book’s release, it quietly slipped out of circulation. That initiated a second and separate endeavor, which was to bring The Harlem Book of the Dead back and to do so in a way that retained the original approach conceived by Camille Billops. She was the glue that brought Van Der Zee, Dodson, and Morrison together. James Hoff, the executive editor at Primary Information, was immediately supportive in helping to bring the book back to life. The only modification to the facsimile edition is the addition of Holloway’s afterword. I think her perspective offers something unique and valuable for those encountering it for the first time.

Bacon: One thing that struck me about Billops’s original impulse to compile these images in a book, which is a form that can be shared widely, is it also means these images are pulled beyond their original context. From my understanding, loved ones of the deceased would commission Van Der Zee to make the photographs included in the book and thus I imagine they were originally placed on a mantelpiece in a family home, or maybe in a scrapbook or photo album. When they’re gathered in a text, they circulate in the public arena. What does that kind of contextual shift mean?

Bradley: I’m thinking about [the Studio Museum in Harlem director] Thelma Golden’s framing of Van Der Zee’s body of work as one that operates as documentation of the Harlem Renaissance but also a “family album” of Harlem as a whole. Van Der Zee talked about his hope for the images in The Harlem Book of The Dead to operate on a formal level that is well beyond documentation and exemplifies his interest and pursuit in having the images go beyond a direct read. The book itself is its own kind of universe and context.

Van der Zee was born in Massachusetts about twenty years after the Civil War. He moved to New York briefly with his father and did odd jobs. He then started a family and left New York briefly, then moved back to Newark and developed his photographic practice, where a good portion of his work was commissioned by a local church. From there, he opened his own place on 272 Lennox Avenue. His arrival in Harlem was really the beginning of the career that defines him. Owen Dodson was thirty years younger than Van Der Zee and grew up in Brooklyn. He was a playwright, a novelist, a poet, and a scholar. Camille Billops was the youngest of them all. She was around fifty years younger than both Dodson and Van Der Zee and was a sculptor, a filmmaker, an archivist, an educator, and an organizer. Billops’s works came so much from bringing people together, and she had a natural instinct that makes the collaboration in this book feel somehow inevitable. And Morrison, who wrote the foreword for the book, was actively shifting the entire literary landscape as a writer. Each of them gave themselves, and their work, permission to be articulated in as many different forms and shapes and styles as necessary.

Bacon: What you’re saying reminds me of this quotation from Toni Morrison’s foreword where she describes Van Der Zee’s photography as “truly rare—sui generis.” What is so clear in his pictures and so marked in his words is the passion and the vision, not of the camera but of the photographer.” A central facet of Van Der Zee’s approach was his editing practice, which feels singular and not only “sui generis,” one of a kind, but also ahead of its time. In the book, he talks about smoothing someone’s wrinkles or adding inserts of angels into the frame so the subject has a companion in the afterlife.

I know you’re deeply involved with the editing of your own films and have spoken about how the editing process is where you get “closest to actually touching your own work” and how physical it can be. I’m curious to hear you speak further about how we might interpret Van Der Zee’s modification of his own images.

Bradley: We live in an elusive time. It’s very hard to touch anything in a digital era—or to be touched. But Van Der Zee was living in an analog world, and when we’re talking about “editing,” there are many ways of looking at it. There are the embellishments that come in the form of painting, collage—a layering of imagery and the photographic negative that operates as storytelling, historical clarification, or correction. [Van Der Zee’s modification of the images] also operates as transcendence and empathy visualized. It connects the personal and the collective. This is where the images exist beyond the subject matter.

There is also a strong element of glamor and of editing for “perfection.” Softening the face, removing the wrinkles, adding a twinkle to the eye. I would say a major difference that shifts the way those changes operate in, for example, a magazine, then and now, is that these images are solely for the people receiving them. The edits become an act of generosity as opposed to a rejection of the viewer or narrowing of what’s accessible.

Bacon: Absolutely. It’s almost like his edits, especially the insertion of angels or scripture into the images, become additional speculatory material that’s particularly tailored to how Van Der Zee imagined the idiosyncrasies of the subject in the frame, not just what’s “really” there.

I was also so taken by the rhythm of the book’s organizational structure. We meet James Van Der Zee by way of his language, before we meet his images. After Morrison’s foreword and Billops’s introduction, we are carried directly into Van Der Zee and Billops’s interview, then you get the lyricism of Dodson’s poetry, and then we submerge into the totality of all of those elements as Dodson’s verses are punctuated by the images. What do you make of the book’s rhythm and how the multitude of voices in this chorus—Morrison, Billops, Van Der Zee, Dodson, the images themselves, and now Holloway—are introduced to us?

Bradley: The book’s spine, so to speak—what really holds the book together—is the dialogue between Billops and Van Der Zee, which encompasses his life story and creative practice. Their discussion unfolds alongside the work, and to the left is Dodson’s writing, which I think acts kind of as an open-ended verse that is not necessarily narration or captioning but parable—something between scripture and query. They can operate as a guide, or even as something that’s contradictory to the image. There’s a lot of openness that exists there, and I think that that’s how the interview between Van Der Zee and Billops also operates in this. Going back to these questions of, What is photography? How does photography operate?, we understand it’s not just documentation because we’re not just getting descriptions of what we’re seeing. We’re in a much different place that is deeply emotional. I think even with all these elements, the book is beautifully unified while also being spacious or timeless, really.

Bacon: I’m interested in how this book resolutely differs from the stream of images of Black death that we’ve been encountering en masse for some time, especially through our phones. The work in The Harlem Book of the Dead feels contrapuntal, like a countermelody to the conditions that create those images and the velocity at which they circulate. There’s a slowness and a stilled-ness—to riff on Holloway’s afterword—to them that injects something devotional that is absent from images of Black death that are captured against our will.

Bradley: What makes this body of work really stand apart from something that we might be seeing on a regular basis or being inundated with today is that the images that are proliferating throughout the internet and that have historically existed around Black death have never been for us. These were portraits that were given to family members as mementos. They weren’t just taken and then put into a news outlet. There was a lot of care and a lot of love. It’s almost like a eulogy that has been visualized and placed into the photograph. I think that that’s where they really stand apart, and that’s a key point.

Bacon: The Harlem Book of the Dead inhabits the emotional environment of life’s limit in such a profound way. I appreciated the way that the writing and images in the book create a scaffold for others to write about bereavement, make images of mourning, and also create language and images that themselves grieve.

Bradley: I think Karla Holloway articulated it best in asking, “Where does one find grief’s conclusion?” She found a compromise with it in the process of writing and in art and in the process of making. The Harlem Book of the Dead is an apt example of that same question. To quote Marcel Proust, ideas are successors of grief, which says to me that America’s culture, aesthetic, and every innovation it has produced has come from grief, and I think this book is also a remarkable example of that.

Bacon: Each of the original collaborators dedicated the book to someone or a group of “someones.” Who or what might you dedicate this facsimile edition to?

Bradley: I think everybody in the world right now is living with grief and trying to navigate its presence. We create things out of it, and that is essentially its purpose: to build something from it, to move through it, and to continue to contribute to the world in a way that helps us continue to understand and process one of the most human and unavoidable emotions that there is. Grief will never go away. It’s a part of our experience here.

It’s also not something we always have a clear understanding of how to move through, particularly as modern people who have been predominantly separated from any original tradition or have replaced it with the idea of being an individual. I might dedicate it to this moment, an era of great global grief as a reminder of the potent and loving power that can be born from it.

All photographs by James Van Der Zee from The Harlem Book of the Dead (Primary Information, 1978/2025)

All photographs by James Van Der Zee from The Harlem Book of the Dead (Primary Information, 1978/2025)© James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and courtesy Primary Information

Bacon: Your response, namely when you said it “will never go away,” makes me think about something specific [Smith] Professor Samuel Ng, who teaches a course called the Politics of Grief, has said about grief: Black grief is pathologized for a multitude of reasons, but especially because of the way it endures, how because a central cause of our mourning, the conditions that beget and necessitate Black death, have not ceased; our grief keeps coming back. It’s cyclical, and it refuses to end within an amount of time deemed “appropriate.” It’s those “circles and circles of sorrow” Toni Morrison describes at the end of her novel Sula. Throughout The Harlem Book of the Dead, grief and its duration are characterized not as some kind of malady but as symptomatic of a life lived on the ledge of recurring disaster—and a life that is still verdant and vibrant amidst it all.

In our last couple of minutes, I would love to linger with one of the images together.

Bradley: Let’s turn to page fifty-three. A young woman lays in an open casket, adorned with lace and white flowers. Jesus holds a baby lamb and looks down at her on the upper right-hand corner of the frame.

It was Holloway’s work that connected the dots between Van Der Zee and Morrison. Toni Morrison’s character Dorcas in her 1992 novel Jazz was inspired by this image. In the novel, Dorcas is shot by her lover but lets him get away because she loves him. To the left of the image, Dodson’s verse further connects the four artists—Van Der Zee, Morrison, Billops, and Dodson himself—across time and story:

They lean over me and say:

“Who deathed you who,

who, who, who, who . . . .

I whisper: “Tell you presently . . .

Shortly . . . this evening . . . .

Tomorrow . . .”

Tomorrow is here

And you out there safe.

I’m safe in here, Tootsie.

Theaster Gates on Waking Up That Energetic Life

“I’m tired of either/or,” says Theaster Gates. Artist, urban planner, activist, potter, archivist, gospel singer, and much else—the eminent Chicagoan has spent his career embodying the possibilities of both/and.

Uniting Gates’s efforts is a commitment to harnessing the energy of everyday materials, as exemplified by his idea of Afro-Mingei: a fusion of African American history and identity with the Japanese philosophy of mingei, which celebrates the beauty of functional objects handcrafted by anonymous artisans. Whether making installations, ceramics, or places, Gates has refused to pit craftsmanship and conceptual art against each other. For him, the lives of ordinary things are an essential thing of life.

“Can we learn to love to do things excellently?” With this question top of mind, Gates recently spoke with the curator and writer Ekow Eshun for a conversation that ranges across the past, present, and future of his art—from the work he’s done with his Rebuild Foundation transforming distressed buildings in Chicago into affordable living spaces and cultural centers, to his founding of the Black Image Corporation, to promoting the significance of clay, to envisioning what it will take to craft new platforms and paradigms for a collective Black imaginary.

View of Theaster Gates: Le chant du centre, LUMA Arles, France, 2024. Photograph by Wyatt Conlon

View of Theaster Gates: Le chant du centre, LUMA Arles, France, 2024. Photograph by Wyatt Conlon  Theaster Gates, Lantern Slide Pavilion (detail), 2011

Theaster Gates, Lantern Slide Pavilion (detail), 2011 Ekow Eshun: I saw you last summer at the Black artist retreat you hosted in Arles, France. You transformed the LUMA Foundation space into a site of manufacture as well as display, where you were making new clay works and then putting them on show. You talked about how you wanted to explore “the museological, political, and social possibilities of clay.” Can you elaborate on that idea of what clay represents for you?

Theaster Gates: I’ve been intentional about acknowledging the polemics of craft as a starting point for recognizing the contribution of craft to all kinds of contemporary practices, and the truth of craft within modernity. We could not have gotten to modern sculpture if it hadn’t been for someone recognizing that the same material that could be used to make a vessel for fermentation could also be used to make a torso, or a neck, or a hand. If we were to look at folk like Giacometti or Henry Moore or Barbara Chase-Riboud, if they were casting it in bronze, they were sometimes doing that from another positive, and that positive may have been directly connected to the plastic arts.

Clay has been the main stage, and artisans have not only been preoccupied with the making of the vessel, they’ve also been occupied with some notions of imaginative thought beyond the vessel. Poetry. Things done in jest in the Greek vessel. Potters making fun of each other, telling stories. Clay is as small as an art historian says it is. And if that’s the case, could I push back against the historian and say, “Oh, actually, this material is big, and it’s central to making”?

Eshun: It’s not about the finished art object. It’s the fact of making and working with the material in itself?

Gates: Yes. Rather than trying to prove that clay could do anything else, I wanted to simply represent the material and its processes, so people might draw their own opinions about the limits or the limitlessness of the idiom. The vessel is a body. It is a foot and a belly and a shoulder and a neck and a lip.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Eshun: Let’s go back. The first time you go to Japan is 2004. Can we talk about what you discovered there in terms of the ceramic tradition, but also how you thought your art might fit into that tradition, and in relation to what you were bringing with you?

Gates: Tokoname, this small Japanese city, birthed in me three things. The first thing was that, relative to the history of this material and great makers, I am nothing. The first thing Tokoname did was it humbled me. I was an American, naive, twenty-nine-year-old sculptor who thought he was going to share how great he was, and I arrived to a town I had never heard of, with people who have no relation to the part of the world that I’m from, and I was immediately humbled by the generations of expert skill, intuition, spirituality, discipline, intention, sociability. I was humbled at how little of a man, how little of a human I was. That I hadn’t read enough poetry. I hadn’t ever worked hard and deeply enough. I wasn’t as kind and as social as I thought I was. I was actually quite selfish. And my skill was bunk, relative to this great mountain that I was in front of. I needed that humility first, because that was the enzyme that broke me down, and that demonstrated that there was a lot to learn—and at twenty-nine, learning that there was a lot to learn. This is after I’ve gone to South Africa. I had a great experience there. I’ve come back. I’ve started my own artist collective.

The second thing Tokoname gave me was a hunger for learning and being a lifelong learner. Because I thought, There’s no way that I’m ever going to be as good as I want to, no matter what the newspapers tell me of a good or bad exhibition. The thing I’m chasing, people spend their whole lives chasing: one glaze color, one bowl form, trying to get spirit from wherever it comes from, through their hands and into a material form. I hungered for that kind of learning and that kind of engine for learning.

The third thing that it gave me was a sense of an aesthetic dimension that had nothing to do with the material world.

Theaster Gates, Afro-Ikebana, 2019. Photograph by Theo Christelis

Theaster Gates, Afro-Ikebana, 2019. Photograph by Theo ChristelisCourtesy White Cube, London

Eshun: Say more.

Gates: That while I was preoccupied with making a tea bowl, the making was actually not about tea bowls. That the pursuit, the aesthetic dimension could be akin to a spiritual dimension. That it’s a way of assigning aesthetic values to a branch—ikebana. To a textile. To the garden. To the creation of paper. To the assembly of your books. To the tying of a box. It was a way of understanding that the world lacked aesthetic dimensionality. The Industrial Revolution, the Romantic era, the age of Enlightenment gave us logic and intelligence, and they disrupted aesthetic dimensionality. And that I could spend my entire practice never making a new work, but simply assigning an aesthetic dimensionality to the objects that already exist in the world.

People talk about that in terms of “reclaimed” and “recycled,” it ain’t about that. It’s about recognizing the aesthetic potential within a preexisting thing. The reason I talk about Shintoism at all is because I’m interested in the possibility of the energetic life that might live within an object. How do we wake up that energetic life?

“If you’re going to make something, make it good. That’s a value that I’m trying to bring back from the past.”

Eshun: You’ve talked before about how you see your work, at least in part, as honoring the spirit within things.

Gates: Yes.

Eshun: But it’s that balance that’s so interesting. That, yes, there’s the spirit, but there’s also the thing in itself. And that seems as important as the feeling one finds within it.

Gates: You know, I’ve seen so often a woodworker make a beautiful table and then put the wrong finish on the table. It’s almost like they woke something up in the material, and then, they smothered it. The hunger for learning would be continuing to learn what the material needs in order to be its best self. If I were to care for this material fully, does it have something to say?

Those are the kinds of questions that I’m asking myself in the studio.

Still from Theaster Gates’s Art Histories, 2019, featuring deaccessioned glass slides from the art history department of the University of Chicago