Nikki Grimes's Blog

July 29, 2019

Owning Our Words

June 18, 2019

Going for the Gold: An Author Intervention

I’m on my way to ALA, the sweet

land of children’s book award ceremonies. I’ll only be there to promote my new

memoir, Ordinary Hazards, not to pick up any plaques, or medals this year. Still,

it got me thinking.

[image error]

Who doesn’t want a book award or citation, or even a starred review? We welcome them, pine for them, lust for them, hope for them. We do so, in part, because we assume they will guarantee success and longevity of our books, and keep them in print. Sadly, that is not always the case. I would know, having a number of such award-winning titles on the proverbial scrap heap of out-of-print books. A notable book citation didn’t keep What is Goodbye? from hitting the pile, nor did the Coretta Scott King Illustrator Award keep Something On My Mind from disappearing from bookstore shelves. (These aren’t my only OP titles, but ouch!) Then, there are those beautiful books that never stay in print long enough to find their market (Under the Christmas Tree, anyone? I dare you to say the paintings by Kadir Nelson are anything less than scrumptious! My poems weren’t too shabby either, if I must say so. I’m getting off point, though. Sorry.)

If awards and major citations don’t

keep a book in print, what’s the point? What’s the deal? The truth is, book

publishing has always been a crap-shoot. There’s really no nailing down which

book will make it, and which one won’t, which book will be chosen for special

honors, and which won’t. Don’t waste your time taking bets. Besides, awards,

while lovely (I won’t be giving any of mine back, thank you very much!), those

shiny stickers don’t come with any guarantees. (Okay. So maybe there’s one or

two exceptions. Still.)

Don’t get me wrong: awards are certainly

worth celebrating, and I’m ready to do the happy-dance whenever one comes my

way. Even so, an award can’t be the reason I write a book. If it were, I’d

constantly writhe in misery (well, more than I usually do) whenever one of my

books failed to take home the gold, or even the silver. No. I write books

because I have to, because I have stories to tell, because I want to entertain,

encourage, inform, inspire and challenge young readers. I write because I want

to touch hearts and, ultimately—I’ll admit it—hopefully change minds, and maybe

even lives. Whether I fail or succeed in the trying, an award is beside the

point. Every time I receive a glowing letter from one of my readers, or a

teacher, a parent, grandparent, or a librarian, I remember that. You should,

too.

Chin up, my fellow scribes! Hope to

cross paths with you on the road as we share our stories, and our hearts, with

the young readers who move us to put pen to paper, in the first place.

January 25, 2019

High Tech, Low Tech, No Tech?

I bought a new car recently (blame

the distracted driver who rear-ended me while I was at a full stop.) My new,

certified used car is essentially a computer on wheels—not the replacement car

I had in mind. However, of all the used cars the dealer had in stock, this one

was in the right price-range. Turns out, all the newish makes and models are

loaded with tech.

[image error]

The sales person was thrilled to

let me know the car was equipped with Bluetooth (what?), could be linked to my

cell phone (huh?), and gave me the capability to view films while driving—as if

I were honestly interested in splitting my attention between, say, Mission Impossible and the road before me. No. Thanks. As for Bluetooth, I

won’t be using that, or most of the other tech goodies available. I find them

all too distracting from, you know, Driving.

The sales person was especially disappointed that he wouldn’t be able to link

my car to my smart phone because—gasp—I don’t have one.

I’m strictly a flip-phone woman. Yes.

You read that right. That means I can’t surf the Internet or check my emails

every two seconds, but I don’t need to, anyway. Who does? (Well, being able to

search for nearby restaurants could come in handy when I’m hungry. Still.) My flip-phone

allows me to make and take phone calls, send and receive texts, and access

messages. What more do I need? “Apps!” you say. Well, apps might be

fun, even useful at times. But necessary? Vital? I don’t think so. Call me

crazy, but I actually manage to navigate the world without apps.

My shuttle driver tries to shame me

into getting on the smart-phone bandwagon. I’ll ask her something like,

“What terminal is my flight leaving from?” Since getting me to the

right terminal is part of her job, this is information I expect her to have. Instead

of just telling me, however, she launches into, “If you had a smart phone,

you could find out yourself, because there’s an app for that.” Really?

I get that the new tech is

convenient, but there are a myriad of ways to get the information I need

without casting myself off the high-tech bridge and getting caught in the

whirlpool of apps, games, and social media connects on-the-go.

I came late to the digital party,

kicking and screaming all the way. I’ve found much of it useful as a

promotional tool for my business, but I’m also painfully aware of its

time-stealing potential. Let’s face it, the Internet is addictive. I waste

enough time on social media at home, as it is. Must I now also take it with me

on the road? I think not. Beyond the basic cell phone, I don’t need tech that

follows me out of the house. Limits must be set.

[image error]

What disturbs me most about all the

new tech, though, is its negative impact on social interaction. Too often, I’ll

walk into a room where two people, seated a few feet apart, are connecting with

each other (you can’t really call it communicating) via their devices. The same

is true of people on lunch and dinner dates. The parties might as well be

seated at separate tables, for all the genuine connection being made. They’re

all too busy slavishly checking their phones between bites of food they aren’t

taking time enough to fully enjoy. What is the point? What ever happened to

conversation? I miss conversation. And eye contact. And having a companion’s

full attention. Sigh.

I know a good many people who feel

quite overwhelmed by constant waves of new tech lapping at the shore of human

imagination. We forget that there are shut-off switches, that no one is holding

a gun to our heads forcing us to use the latest app dropped into the digital

universe. Those who feel overwhelmed complain that they don’t have enough time

for their art, for their spouses, for their children, for—fill in the blank. But

if they weren’t constantly plugged into their various devices, playing games,

exploring the latest new app, checking email and mindlessly scrolling through

social media newsfeeds several times a day, they’d have more of the time they

crave. How do I know this? (Behind on a deadline, anyone?) As I’ve already

admitted, I’m scrolling right along with the rest of the crowd! It’s a habit

I’m determined to break.

High tech, low tech, no

tech—whatever we choose, it’s a trade-off. We can choose more convenience and

connection, but the cost is less security, and less opportunity for genuine,

interpersonal communication. If we choose less convenience and less broad-based,

or abbreviated connection, we multiply the time we have for deep personal

communication, for mindful living, for art, for greater awareness of our

surroundings.

It all comes down to time, the most

precious commodity we have. How we use it, and how much of it we have to use,

is very much bound up with the choices we make concerning high tech, low tech,

or no tech. Take your pick. It really is a choice.

I look up all the time. I notice

the clouds dance across the sky, the Magnolia blooms spilling their vanilla

scent, the rash of mushrooms following a rain, the hummingbird nuzzling a rose.

Do you?

[image error]

June 22, 2015

Lessons from Charleston

An unarmed black person dies at the hands of, or in the custody of, white policemen, and we run around as if our hair were on fire, screaming, “What can we do? What can we do?”

An unarmed black person dies at the hands of, or in the custody of, white policemen, and we run around as if our hair were on fire, screaming, “What can we do? What can we do?”

Nine black souls are massacred in a house of worship, in a state where the Confederate flag, symbol of hatred, flies proudly, and we run around as if our hair were on fire, screaming, “What can we do? What can we do?”

I won’t claim to have all the answers, but I certainly can suggest a few, the most important of which has nothing to do with gun control, and everything to do with empathy. We need to teach our children empathy. It’s a lot harder to murder someone you have empathy for than someone you don’t.

The perpetrator of this latest atrocity was not mentally ill, as some wish to suggest. (Please don’t insult me by suggesting every white person who kills a black person is mentally ill. I grew up with a parent who was genuinely mentally ill, so I, for one, know the difference. Oh, and, I should note: she didn’t kill anyone.) Nor was this perpetrator born with hate in his heart. No one is. Hatred is a seed that must be planted, watered, fertilized, and nurtured. The ugly fruit of hatred is not produced in a single, sudden moment. Rather, it ripens over time. It is not inevitable. I repeat: race hatred is not inevitable.

As a seedling, hatred can be uprooted early on. Or, it can be left untouched in its own environment and allowed to produce a head and heart both poisoned, and poisonous. While children are yet children, and still under our care, we adults get to influence which of those two things happen.

Instead of looking the other way while hatred takes root in young hearts and minds, why not try this: Plant the seeds of empathy. Teach the young to feel the heartbeats of races and cultures other than their own. Replace any possible fear of the unknown, with knowledge of the knowable. Teach them the ways in which we humans are more alike than we are different. Teach them that the most important common denominator is the human heart. Start with a book.

Give young readers books by and about peoples labeled “other.” I’m not talking about one or two books, here and there. I’m talking about spreading diverse books throughout the curriculum, beginning in elementary grades, and continuing through to high school. Why? Because racism is systemic and teaching empathy, teaching diversity, needs to be systemic, too.

You say you want to change the dynamic of race relations in America. Well, here is a place to begin—unless, of course, you’re not really serious. In that case, by all means, keep running around like your hair is on fire, screaming, “What can we do? What can we do?” every time an unarmed black person is killed by a white policeman, or a group of innocent black people is massacred. Just don’t expect me to keep listening. I’ve already told you where to begin.

October 21, 2014

The Gift of Story

A recent blog by Sally Lloyd-Jones got me thinking about a question we authors hear some version all the time: Where do you get your ideas, or how do you come up with ideas for your stories? The question would suggest that there’s a treasure trove, somewhere, packed with stories ready for the taking. Or that there’s a place one could go, a repository one can simply dip into, at will. But, the truth is, story ideas are more elusive than that. Their source is far less predictable, more a matter of magic, or of serendipity. An idea might spring from a period of fasting, or flash of insight during a meditative state, or result from literally tripping over an object that brings that idea to mind. No matter the origin of an idea, or the vehicle that brought it to you, that idea, that story, is a gift.

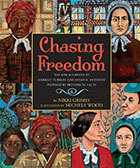

I’ve been thinking about my newest title, Chasing Freedom, releasing in January 2015, and trying to trace it’s origins. The initial idea came to me while I was busy working on something else. The something else was a series of dramatic monologues for a theater production to be performed in China, in 1988. The theme of the show was American History, and so I chose as my subjects Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Susan B. Anthony. In the midst of researching their stories, and crafting their monologues, I became excited to learn that they not only lived at the same time, but all knew each other. One day, while thumbing through these histories in the stacks of the Doheny Library at USC, I suddenly thought, “I wonder what it would be like if Harriet Tubman and Susan B. Anthony sat down for a talk.” That notion was the seed that eventually led to my writing Chasing Freedom. I wasn’t looking for an idea, mind you. It simply arrived of its own! A gift.

I’ve been thinking about my newest title, Chasing Freedom, releasing in January 2015, and trying to trace it’s origins. The initial idea came to me while I was busy working on something else. The something else was a series of dramatic monologues for a theater production to be performed in China, in 1988. The theme of the show was American History, and so I chose as my subjects Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Susan B. Anthony. In the midst of researching their stories, and crafting their monologues, I became excited to learn that they not only lived at the same time, but all knew each other. One day, while thumbing through these histories in the stacks of the Doheny Library at USC, I suddenly thought, “I wonder what it would be like if Harriet Tubman and Susan B. Anthony sat down for a talk.” That notion was the seed that eventually led to my writing Chasing Freedom. I wasn’t looking for an idea, mind you. It simply arrived of its own! A gift.

I turned my thoughts to Words With Wings, a novel-in-verse about daydreaming, and I tried to trace the origins of that story. This task was more difficult, because the genesis of the idea was much less straightforward. Over the years, I’d read or heard comments by teachers about the importance of nurturing the imagination; read or heard Steve Jobs bemoan the fact that children are no longer encouraged to daydream; read or heard nameless others comment on this subject, in one way or another. Somewhere along the line, this train of thought stuck, and I began thinking about my own childhood, and how important daydreaming had been in my own formation, and later success, and I realized how much I wanted that for the children I serve through my work. Out of this thick soup of essays, articles, off-hand commentary, and personal memories grew the idea for a novel about a daydreamer. So there.

I turned my thoughts to Words With Wings, a novel-in-verse about daydreaming, and I tried to trace the origins of that story. This task was more difficult, because the genesis of the idea was much less straightforward. Over the years, I’d read or heard comments by teachers about the importance of nurturing the imagination; read or heard Steve Jobs bemoan the fact that children are no longer encouraged to daydream; read or heard nameless others comment on this subject, in one way or another. Somewhere along the line, this train of thought stuck, and I began thinking about my own childhood, and how important daydreaming had been in my own formation, and later success, and I realized how much I wanted that for the children I serve through my work. Out of this thick soup of essays, articles, off-hand commentary, and personal memories grew the idea for a novel about a daydreamer. So there.

The origin of the idea for my next book, Poems in the Attic, out next spring, is a bit clearer, but not much. I watch the nightly news as much as anyone, and I’ve noticed a barrage of stories about our military over the recent years. With troops in Afghanistan, Iran, and Iraq, especially, this last decade has produced miles of videotape about soldiers. I especially noticed the preponderance, of late, of images on television of soldiers returning home, snuggling with their children after long tours away, images of both fathers and mothers in uniform, nearly wrestled to the ground by children so excited to have them home, again. These images stuck. Then, there was the show Army Wives, which brought these themes into my living room weekly. Besides the above, there’s the fact that several of my friends regularly share childhood stories of growing up as military brats. At some point, a couple of years ago, I started thinking about the increasing number of children who have to negotiate the uncertainty of life with a parent in the military, and I wondered if I might offer some small collection of poetry that would speak into that. Hence, the story-in-verse book, Poems in the Attic.

The answer to the question of where stories come from is rather random, isn’t it? It’s mysterious. It’s magical. It’s simple: a story, and the idea that gives birth to it, is—a gift. Yeah. That sounds about right.

September 11, 2014

Mister Cellophane

I recently read a blog post by author René Saldaña, Jr., that got me wondering—and not for the first time—how much effort teachers and librarians, especially, go to when searching for books by authors of color. It is a question worth asking.

I recently read a blog post by author René Saldaña, Jr., that got me wondering—and not for the first time—how much effort teachers and librarians, especially, go to when searching for books by authors of color. It is a question worth asking.

The other day, out of curiosity, I Googled myself. I found a whopping 1, 470,000 results listed under my name. These include bios, videos, interviews, periodical features, photos, and, of course, books and audio-books. Wow. And yet, I regularly meet teachers and librarians who are wholly unfamiliar with my work. How is that possible?

Now, I’m not saying my work is the greatest thing since sliced bread, because there are writers out there whose wordsmithing I envy. What I’m saying is that my titles are not exactly in hiding. In fact, throughout the course of my career, I have worked diligently to make sure they’re not. From seeking out bookstore signings, in my early days; to doing school visits; to producing postcards and bookmarks; to creating a comprehensive website; to investing in teacher guides for my books; to developing an online presence via Facebook, and now Twitter—in these ways, and more, I have made a concerted effort to put my work out there. How is it, then, that many people still manage to miss it?

Now, I’m not saying my work is the greatest thing since sliced bread, because there are writers out there whose wordsmithing I envy. What I’m saying is that my titles are not exactly in hiding. In fact, throughout the course of my career, I have worked diligently to make sure they’re not. From seeking out bookstore signings, in my early days; to doing school visits; to producing postcards and bookmarks; to creating a comprehensive website; to investing in teacher guides for my books; to developing an online presence via Facebook, and now Twitter—in these ways, and more, I have made a concerted effort to put my work out there. How is it, then, that many people still manage to miss it?

Before I go any further, let me say that I am extremely grateful for those teachers and librarians who have sought out and found my work, over the years, and then went on to share it with the students they serve. Obviously, I wouldn’t have much of a career without these literature-loving professionals. They have kept a goodly percentage of my 46 trade, and 20-odd mass-market books in print. I’m hoping they receive to my next two titles with equal kindness. However, after 30+ years in the business, I still routinely hear people say, “I’ve looked for your work everywhere and can’t find it,” to which I respond, “Huh?”

Before I go any further, let me say that I am extremely grateful for those teachers and librarians who have sought out and found my work, over the years, and then went on to share it with the students they serve. Obviously, I wouldn’t have much of a career without these literature-loving professionals. They have kept a goodly percentage of my 46 trade, and 20-odd mass-market books in print. I’m hoping they receive to my next two titles with equal kindness. However, after 30+ years in the business, I still routinely hear people say, “I’ve looked for your work everywhere and can’t find it,” to which I respond, “Huh?”

I have a website featuring all of my titles, awards, audio-clips, and select reviews, with posted links to IndieBound.org and Amazon.com. In addition, I have a Wikipedia page, as well as an Amazon.com page. How hard have you been looking, exactly? I’m confused.

I have a website featuring all of my titles, awards, audio-clips, and select reviews, with posted links to IndieBound.org and Amazon.com. In addition, I have a Wikipedia page, as well as an Amazon.com page. How hard have you been looking, exactly? I’m confused.

Sylvia Vardell’s must-view Poetry for Children website lists many of my poetry titles. TeachingBooks.net features my Coretta Scott King Award and Honor winners (six in total). I, thankfully, have books on any number of Best Book lists. Tell me again how hard it is to find my work.

Clearly, there’s more to the lack of diversity in children’s books than whether or not POC are creating and publishing them. Could it be that some lack the motivation to seek out the books that are already there? That’s what René Saldaña, Jr., is asking. Now, I am, too.

Clearly, there’s more to the lack of diversity in children’s books than whether or not POC are creating and publishing them. Could it be that some lack the motivation to seek out the books that are already there? That’s what René Saldaña, Jr., is asking. Now, I am, too.

Mind you, I’m not saying that we don’t need more books by people of color, because we most certainly do. The numbers show that we are woefully off the mark in producing diverse books in numbers commensurate with the proportion of our ever-increasingly diverse population. But that said, I am suggesting that we, perhaps, look at the issue a little more closely, that we ask a few more uncomfortable, but necessary, questions.

René Saldaña, Jr., spoke to this issue from the point of view of an author with a little less visibility than mine. And yet I have to agree with so much of what he has to say.

The juggernaut that is #WeNeedDiverseBooks is hard at work to raise the visibility of books by, and for, people of color. This is great and important work. Still, I can’t help but wonder if there’s more going on beneath the surface that would explain why the gatekeepers in this business continue to miss the POC books—including Coretta Scott King, Pura Belpré, Newbery, Caldecott, Printz, and National Book Award Winners—that are already out in the marketplace.

Where, exactly, is the disconnect? Is it the want-to that’s missing? If so, how do we begin to address it?

Let’s talk.

August 28, 2014

Under the Gun

My friends come in many sizes, shapes, and colors. I am open to each one because I judge according to character, not color.

So the argument goes something like this: Policemen come into contact with any number of violent, criminal black men during the course of their careers, and so it is only reasonable that they should view all black men as potential threats, and should have their loaded guns at the ready, whenever, wherever, and  under whatever circumstances they happen to encounter a black male, no matter his age, size, appearance, or demeanor.

under whatever circumstances they happen to encounter a black male, no matter his age, size, appearance, or demeanor.

To the above, I respond thus: As Negro, Colored, Black, African-American peoples, we individually, and collectively, carry in our hearts, minds, and souls, the memories of countless lashings, lynchings, cross-burnings, cattle prodding, water-hosing, hangings, bombings, whippings, rapes, mutilations, tarring, feathering, and police-baton beatings at the hands of people with white skin. In addition, we have in the past, and continue to suffer in the present, acts of discrimination at the hands of people clothed in white skin, some of whom hurt, harm, mistreat and misjudge us every day. (For those of you who think otherwise, racial discrimination is, sadly, very much alive in America. We wish it weren’t.)

Having said that, it’s important for you to know that I do not spend my days enraged or even angry. Life is too short to walk through the world with a permanent chip on one’s shoulder, no matter the rationale. The truth is, I’ve got better things to do. So have most of my friends. Besides, we prefer to interact with, and judge, each person we encounter based on the

content of their character, not the color of their skin. Most African Americans will tell you the same.

Now, re-read the earlier paragraph, and note that none of the aforementioned atrocities lead black people to leave our homes, armed to the teeth, and ready, without a moment’s hesitation, to mow down every white person we encounter, in whom we see the shadow of other whites who may have hurt or harmed us or threatened our very lives.

What, ultimately, is the key difference between a black person who refuses to see every white person he encounters as a threat, and a white person, policeman or otherwise, who refuses to see a black person, particularly a male, as anything but? Choice. It really boils down to choice.

Here’s a novel that explores the complexities of the issue of race and gun violence in an even-handed way.

Shooting to kill is not an accident. It’s a choice. It’s a choice in Ferguson, in Florida, in Chicago, in New York, in Anywhere, USA.

The arguments put forward by police and private citizens, for shooting to kill any and every black man or boy they see in the street, day or night, does not pass muster. A refusal to holster hate, or unprovoked fear, is a choice. Not bothering to tell the difference between a burgundy car and a tan car is a choice. Not taking care to distinguish between a car full of school children, and one full of potential adult male suspects, is a choice. Failing to differentiate between a boy, or a man, on the attack, and a boy or a man with his hands in the air, is a choice. And, by the way, punching, or pummeling an unarmed, middle-aged woman on the side of a freeway is a choice.

A choice is a decision, not a cause for making excuses. Any mature, mentally healthy adult can tell the difference between the two.

August 13, 2014

Coming Attractions

I love it when children’s books do well in the world. I was excited to join Katherine Paterson at the film premier of Bridge to Terabithia, a couple of years ago, and can’t wait for The Great Gilly Hopkins to hit the big screen. I’m all a-tingle just thinking about the wide release of Lois Lowry’s, The Giver. I thoroughly enjoyed The Fault In Our Stars, and the growing number of other Hollywood treatments based on children’s and young adult books. But—there is a but.

Where, oh where are the films based on children’s and YA titles written by authors of color? Why is no one optioning some of the worthy titles by these authors?

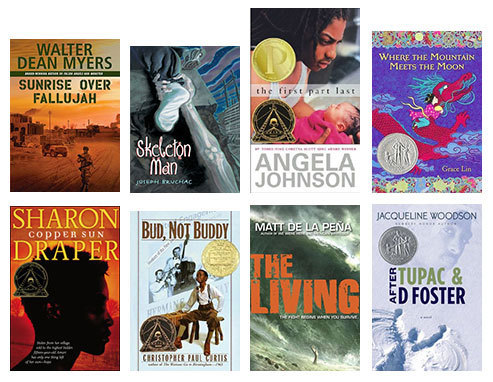

My question is as much to black filmmakers and black movers and shakers (and Latino, and Asian, and—well you get my drift) as it is to anyone else. There may not be as many moneyed POC in Hollywood as there are whites, but there are certainly a number of heavy hitters I could name. Why aren’t they stepping up to the proverbial plate? I know they have production companies of their own, so why aren’t they making moves to acquire the rights to works by Walter Dean Myers, or Joseph Bruchac, or Angela Johnson, or Grace Lin, or Sharon Draper, or Christopher Paul Curtis, or Matt de la Pena, or Jacqueline Woodson, or—well, we’ve got a decent list of our own. (We may be small, but we are mighty!) And mind you, I’m talking about award-winners, and bestsellers, so the book-to-film audience is there, in case anyone asks. I just wish our affluent counterparts in the film industry would rise up to the dollars and sense to be made by developing our books for the big, or small, screen.

Oprah Winfrey, Will & Jada Smith, Spike Lee, are you listening? BET, what about it? Tyler Perry, what do you think?

What’s it going to take, huh? Look, I’m not saying it’s going to be easy. (Is anything important ever?) I’m just saying it’s going to be worth it.

July 21, 2014

Everything Old is New Again

In preparation for a lecture I was giving on the use of poetic elements to enhance prose, I dug through a few old newspaper and magazine articles I’d written for sample passages in which I had done precisely that. In the midst of my search, I came across a piece of reportage from 1977 that had particular resonance. The title of the piece was “Broadway Orchestras: A Pit of Discriminatory Hiring,” and it was all about a lack of diversity in Broadway theater orchestras, discussed at a public hearing I was sent to cover.

“During this year, the Houston Opera Company produced two major Black shows. The first, Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha, featured 35 musicians in its orchestra. The second, Porgy and Bess, features a 43 man orchestra. Of these 78 musicians only seven were black.

“Eleanor Holmes Norton, of the Commission on Human Rights, brought these facts to attention recently in a public hearing entitled “Hiring Practices for Broadway Musical Orchestras: The exclusionary Effect on Minority Musicians.”

“The hearings, designed to ‘determine which recruitment and hiring practices result in this (exclusionary) pattern…’ brought out some of Broadways key producers, contractors, and Black musicians. Among them were producers Norman Kean and Philip Rose, contractors Earl Shendell and Mel Rodnon, musicians Gayle Dixon and Jack Jeffers, and actor, producer, director Ossie Davis.

“What brought on all the hooplah?”

Akua Dixon (photo: James Rich)

Reading this piece gave me chills, for a range of reasons. For one, Ruby Dee, widow of the late Ossie Davis, had just passed. For another, the viola player Gayle Dixon, sister of friend and cellist Akua Dixon, was a personal acquaintance. Akua had just recently mentioned Gayle, who passed years ago. These twin facts were reason enough for my goose-bumps, but there was a third. The piece was about diversity or, more precisely, the lack thereof. In this case, it pertained to Broadway orchestras. These days, a lack of diversity most often pertains to children’s literature, a subject I have addressed on more than one occasion. Apparently I’ve been bumping up against, and speaking out about, this issue for quite some time.

I wonder about the state of Broadway orchestra pits today. It’s been a long time since I last followed up on the subject. I’ll have to get the skinny from Akua. As for diversity in children’s literature, well, in case you haven’t been keeping up, the stats remain pretty dismal. But this isn’t a piece about statistics. This isn’t even a piece about the dollars and sense of publishing and marketing a more diverse selection of books for an ever-expanding, diverse population of readers. Instead, I want to talk about the good of it all. What comes from sharing books featuring children of one race or culture, with readers of another? That’s what I want to speak to.

I know a thing or two about sharing children’s books across the color line, and not because I’ve taken polls, but because I’ve written and published more than 60 books since I entered this field, in 1977. Over that time, I’ve gathered hundreds of letters and emails from readers. I haven’t crunched the numbers, but I’ll wager that a significant percentage of them are something other than African American. Some are Asian, some are Latino, and many are white. How do I know that? It’s usually easy enough to judge from the name but often I don’t have to because the readers, unbidden, choose to mention their ethnicity. Yes, they write to tell me how they feel about my books, but also to introduce themselves. In the process, they share basic information about who they are: their names, ages, schools, grades, where they come from, and their ethnic backgrounds. Mind you, if we adults didn’t make such a big deal of the latter, these young people wouldn’t either!

I know a thing or two about sharing children’s books across the color line, and not because I’ve taken polls, but because I’ve written and published more than 60 books since I entered this field, in 1977. Over that time, I’ve gathered hundreds of letters and emails from readers. I haven’t crunched the numbers, but I’ll wager that a significant percentage of them are something other than African American. Some are Asian, some are Latino, and many are white. How do I know that? It’s usually easy enough to judge from the name but often I don’t have to because the readers, unbidden, choose to mention their ethnicity. Yes, they write to tell me how they feel about my books, but also to introduce themselves. In the process, they share basic information about who they are: their names, ages, schools, grades, where they come from, and their ethnic backgrounds. Mind you, if we adults didn’t make such a big deal of the latter, these young people wouldn’t either!

The notes and letters I receive from children and young adults across the country, and around the world, are very telling. Here’s what I’ve learned from readers:

They like humor.

They enjoy being moved and inspired.

Some have come to my books disliking poetry, but have come to love it. Many have since tried their hand at poetry, themselves.

Some come to my books as reluctant readers, but leave as avid readers.

They relate to my contemporary storylines.

They see themselves in my characters.

As for the color of my characters? Basically, my readers could care less. When they comment on race at all, it is only to explain exactly why race doesn’t matter:

Mariah T. says: “I’m white but to me race doesn’t matter, not one bit, and I’m reading your book Bronx Masquerade, and so far, I love it.”

Mariah T. says: “I’m white but to me race doesn’t matter, not one bit, and I’m reading your book Bronx Masquerade, and so far, I love it.”

Zach A. writes: “I think that if most of the characters in a book are not the same race as you, that should not stop you from reading it. That’s racist and just plain silly.”

Ary B. comments: “I stick my nose in your book, and have a hard time taking my nose out of it. I can put myself in your characters’ shoes and pretend to be them, even though I am white. I think African American authors should actually be recognized more, because it is nice to think that instead of assuming everyone is white, which white people tend to think, we are looking at the world in a whole new perspective.”

Can I get an Amen?

Unlike adults, children and young adults get it: the thing that matters most about a book is Story. And when readers are given the opportunity to dive into stories across lines of color and culture, they walk away with valuable lessons, such as:

We are more alike than we are different.

We all bleed.

We all experience joy and laughter, suffering and pain.

We all need love and blossom when we have it.

We are all capable of both good and evil.

What separates us is not our color, but our character.

We live in a country that, in word at least, celebrates its cultural multiplicity. Isn’t it past time that the books we share with our children reflect that, as well? There is only one right answer to that question, by the way.

We live in a country that, in word at least, celebrates its cultural multiplicity. Isn’t it past time that the books we share with our children reflect that, as well? There is only one right answer to that question, by the way.

If we live in a culturally diverse world—and we do—it behooves us to learn something about the cultural groups we live among. One of the least intimidating ways to learn those lessons is between the pages of a book. Yes, I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating.

As we in the diverse children’s book community like to say, let’s move the needle. This issue has been stuck on pause long enough, and it’s our children—Native American, Asian, Latino, African-American, and white—who are paying the cost.

April 26, 2014

Baffled

In my college dorm with a special room-mate,

my daughter, Tawfiqa

I just got back home from seeing the movie, “Heaven is for Real” and I’m baffled.

“Heaven is For Real,” based on a book of the same name, is the story of a four-year old boy who has a near-death experience. Once he returns to his body, he begins relating anecdotes of his visit to heaven. He’s quite matter-of-fact about it all. Sadly, no one else is. Not the members of the church board, who prayed fiercely for his recovery; not his mother who leads the church choir; not even his father, who is the church’s pastor. And that’s what’s baffling. A man acquainted with the holy scriptures, which declare the existence of heaven, in no uncertain terms; a man who has read about, and, I’m sure, preached on the promise that, when a believer dies, he or she will enter heaven and be greeted by loved ones who passed on, before—this man does not actually believe that his son has seen heaven, or that heaven physically, literally—not metaphorically—exists.

What is such a man doing in the pulpit? What exactly is his wife singing about every Sunday morning? Why do members of the church board bother to gather, at all? That is what baffles me. After all, when it comes to the Nicene Creed, Heaven and Hell, death, resurrection and eternal life are pretty basic.

In May of 1974, I rocked back and forth over the grave of my daughter, Tawfiqa, my one and only child. She died just before her fourth birthday. As a poet and author, it’s fair to say that I am quite the wordsmith. However, believe me when I say this: I do not possess the language to make you understand the depth of the pain I felt at the loss of my child. The pain I feel. The pain I will continue to feel until the day I die. What makes it possible for me to stand, let alone laugh and know joy in my life, is the certainly that I will one day see my precious child again. The Bible has taught me that. The Spirit of God has impressed that upon my heart. Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ who died on Calvary, then conquered death by rising again, did so, in part, to make that very reunion possible. If you believe that, as I do, you live your life with power. If you don’t, as the pastor in this film did not, then you live within the constraints of your own human power, which is to say, with no power at all. Let’s face it, human power is, at the end of the day, an illusion. I’m not interested in living with the limitations of man. Are you? But I digress.

My central question, here, is why anyone would pour himself into the work of the church universal if he doesn’t even believe in its most basic doctrines. And when he, for a moment, began to consider that maybe heaven actually was real, why did he care that people made fun of him for it? If, in fact, he’s going to heaven, he will most certainly have the last laugh. When people mock my faith, that’s what I hold onto. But then, he is not me.

Maybe the gentleman in this story was placed near the Light so that his own son could lead him fully into it. Yeah. That could be it. Of course, what this particular man was doing in that particular church pulpit is really none of my business. It’s God’s. Better I should direct my time and energy into feeling grateful—grateful that I believe in the Christ who died so that I could live for him here on earth, and with him some day in heaven; grateful that I can look forward to seeing my beautiful daughter, again, as well as my foster brother, and many others whom I’ve lost along the way; grateful that my belief in such things is matter-of-fact—not because such things aren’t miraculous, but because the God of the Universe has shown me miracles time and time again.

What about you? Have you run into any angels lately? Have you experienced the miraculous? Do you even want to? The one great power we humans have is choice.

Nikki Grimes's Blog

- Nikki Grimes's profile

- 589 followers