George Weinstein's Blog

November 8, 2025

Too Many Books?

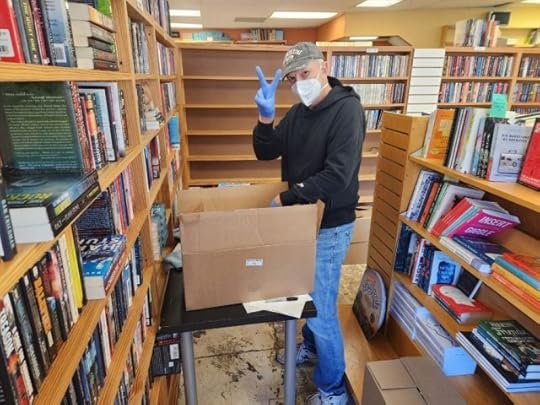

A favorite indie bookstore in my community called Bookmiser was damaged recently by smoke and soot when an adjacent store caught fire. When the bookstore owner put out a call for volunteers to help them sanitize their stock of hardbacks and paperbacks, my wife—author Kim Conrey—and I signed up to assist. We were joined that day by several other local authors. Our task was simple: clean the exterior of the books and box them for storage while the shop underwent renovation.

What was interesting about our morning of volunteering was that all of us writers experienced the same loop of thoughts while cleaning hundreds of volumes: There are already so many books for sale, maybe too many, and perhaps I’m wasting my time trying to put more out into the world.

Bookmiser sells new and used books. I was assigned to the used book section, cleaning suspense novels of old—John Dunning, Frederick Forsyth, and the like. Over the last forty years, I’d read many of the novels I sanitized, but I wondered whether anyone else was still reading them. I considered the hundreds or thousands of hours of effort and creativity each book represented and how many people in addition to the author had added their talents to the publishing process. These books all had their moment of popularity; some had even been made into movies.

But now here they sat, side by side by side, shelf after shelf, price discounted but still no longer selling, no longer being read. All around me were thousands of other books representing time and toil, inspiration and perspiration. And this was but one bookstore in a region with dozens of them—all of which were stocked with volumes that by and large no one was buying let alone reading.

What was I thinking, adding to this already-oversaturated marketplace?

The funny thing was that, when I compared notes afterward with Kim and the other authors volunteering that day, I learned that they too were thinking the same things. Having the same feelings of futility.

On our own and collectively, though, we also reached the same conclusions. Yes, there are already too many authors publishing too many books, with seemingly fewer people than ever buying and reading. But we don’t write to achieve fame or fortune. We write because it feeds our soul. The creative process delights us, entrances us, compels us. It makes us whole. We’re driven to write, to create and to share, just as others are inspired to make their own art, to craft something from nothing.

If we hold on to that belief, then it doesn’t matter that there are hundreds of millions of other books already in the world and thousands more are being published daily. The book we’re writing isn’t out there yet. And it needs to be.

So get back to work.

The post Too Many Books? appeared first on George Weinstein.

August 6, 2025

The Future of the Book

From the Reader’s Perspective:

Many people envision the future as a depersonalized experience, where we’re all cogs in the machine, reduced either to energy-producing units (e.g., The Matrix) or undifferentiated pleasure-seekers (e.g., Wall-E): in both cases, soulless and anonymous. Ever the iconoclast, I think the future will give us ultra-personalization, from what we wear to what and how we read. We’ll still have physical books, audiobooks, and ebooks, but our experience with them will be as individual as each of us is.

Paperbacks and hardbacks will continue to offer the tactile pleasure of holding a beautifully crafted volume—even more artful than the current leatherbound, sprayed-edge craze. You might be able to order a book in various aromas of paper (with as many options than incense provides) to engage more of your senses. Page textures might vary as much as print sizes. In these ways, physical books will become more cherished, with some ultra-bougie versions treated as luxury items. For those who want to disconnect from screens for a while, books in this traditional—albeit heightened—form will provide a sensuous experience.

Digital books will evolve even more. Integrated, augmented reality and virtual reality in three dimensions could bring any story to life with visual depictions of settings, action scenes based on the text that would be watchable from multiple viewpoints, and so on. Nonfiction could teach you even more effectively in this way. Active participation will make the author’s words feel personal and realistic. The e-reader could analyze your eyesight and light level and adapt the font size and screen brightness accordingly, to always make reading comfortable. Moreover, it could detect whenever you pause on a word or reread it and offer a contextual definition and synonyms to assist your understanding.

Many audiobooks are already using AI-generated voices, but, unfortunately for voiceover artists, those narrative skills will continue to improve. Soon, audiobooks will be narrated in tones that are indistinguishable from human ones, with the ability to adjust the pace and emphasis to fit the mood of the scene and the author’s style, seemingly with a diverse cast of dozens or hundreds—whatever the text calls for.

The book of the future will adapt to your life. One format won’t replace another. Rather, you’ll be able to choose the reading experience that best suits your mood, location, and desire for engagement. You will have more ways to connect with stories and knowledge than ever before. Reading will become more accessible, more adaptable, and a profoundly more personal experience.

From the Writer’s Perspective:

The book of the future will adapt to the reader’s life. One format won’t replace another. Rather, you’ll be able to choose the reading experience that best suits your mood, location, and desire for engagement. Physical books will be able to be ordered with custom flourishes—escalating levels of cover design and illustrations and perhaps even different paper scents and textures. Each copy could be as individual as the person ordering it. Ebooks could be enhanced with augmented reality and virtual reality in three dimensions could bring any story or nonfiction tome to life. Audiobooks could be orchestrated with a diverse cast of dozens or hundreds of voices—whatever your text calls for.

Therefore, the craft of writing will begin to incorporate these considerations. The flourishes you as the author introduce in the text will influence readers’ experience of your words like never before. Your creativity will become even more important and distinguish you from your writing peers because those choices you make, word by word, chapter by chapter, will be enhanced by the technological evolution of books in their various forms.

While AI will continue to help you to eliminate grammatical errors and brainstorm ideas, no program will ever be able to match your intuition about characters, plot twists, settings, and so on. Despite that, AI will nonetheless be your competitor, as companies churn out a seemingly infinite number of stories, with AI-generated marketing to trumpet them, in the time it takes you to perfect your masterpiece. Any reader paying the least bit of attention will be able to discern the human touch from the derivative, literally unimaginative products those firms will blast out, but they might still fall for the pretty packaging and only too late realize there’s no soul behind those words. The trick will be rising above the scintillating noise so that readers discover you and your creative work. Unfortunately, the days of the hermit-like writer who won’t engage with their audience are long gone—that is, if that writer wants to be read.

As self-publishing, micro-presses, AI-narrated audiobooks, and other independent platforms continue to offer free or inexpensive means of getting stories into the hands/ears of readers, even more writers can enter the industry and try to make their mark. This, too, is a double-edged sword: the democratization of publishing gives more writers a shot, but that means even more competitors will be vying for a finite number of readers’ attention and digital wallets.

It is also possible that readers will want a bigger say in the literary entertainment and education they consume and will favor writers who give them a voice in the way a story unfolds or nonfiction is presented. The art of writing and the act of reading could incorporate a feedback loop, with serialization, fanfiction, and perpetual interaction between creator and consumer producing a dynamic, fluid process, where the book continues to evolve and remains a living entity rather than a fixed product. The Neverending Story could thus become the subtitle of every story. Such a world would turn paperback and hardback books into anachronisms because those tomes would be frozen in time, unable to evolve.

That future might never come to pass or only will do so for authors who want to continue to engage with the same story forever, but it’s a certainty that technology will influence more than ever what we write, how we write, and how readers engage with our work.

The post The Future of the Book appeared first on George Weinstein.

June 2, 2025

Baby Steps within the Footprints of a Giant

On behalf of the Atlanta Writers Club (AWC), I recently launched an author mentorship program, adding it to the ever-growing list of opportunities we offer members. Within a week of announcing it, more than 40 members had applied to be mentored, and, in short order, I had about 30 mentors willing to help 1-2 mentees each.

The pent-up demand among writers who are in search of guidance and among authors who want to give back or pay it forward led me to reflect on my own experiences as mentee and mentor. When you’re starting out in the complex field of writing—with its intrinsic mix of totally subjective creativity and utterly brutal economic realities—you do not know what you don’t know. At that early stage, everyone else seems more knowledgeable and sophisticated, and therefore, everyone’s advice seems credible and correct.

If you’re lucky when you start asking other writers for guidance or they volunteer to share their hard-won wisdom with you, you get a mentor who will encourage you to develop your writing voice and dig into the themes that motivate you to keep writing while preparing you for the complicated road ahead, whatever your writing goals. I was not so fortunate. During my first few attempts at finding a mentor, I fell in with one writer after another who seemed to know what they were talking about but set about changing my writing voice and style to match their own until I no longer recognized my own manuscript or enjoyed working on it. Some punishing feedback at the Iowa Summer Writing Festival sent me back to square one and taught me a lesson about never taking all advice at face value.

Through the Atlanta Writers Club, I learned to think more critically about feedback and started a critique group that I’ve now run for more than 20 years, to help writers make their work better. I also met some authors who actually knew what they were talking about, but I was gun-shy and unwilling to let anyone else mentor me. And I could’ve benefited from the insights of those who had trod the path I was on. If I had been open once again to mentoring, I might have avoided spending six years represented by an agent who never sold any of my manuscripts to a publisher but kept promising that good things were just around the corner. I might not have quit writing for a few years in frustration. Maybe I could’ve been published sooner and built a bigger audience faster. In other words, for you few remaining On the Waterfront fans, “I could’ve been a contender. I could’ve been somebody.” Rather than getting a one-way ticket to Palooka-ville, though, I finally did get published and have managed to build an enthusiastic readership, but everything took much longer than I thought it would.

The older I get—yay, 59—the more stoic I become, so I reconcile myself with the assurance that everything that happened needed to happen. Which means that I was also fated to meet the late, great Terry Kay—author of To Dance with the White Dog and numerous other novels—through my work with the AWC and begin a decade of tutelage at the hands of a master motivator and author extraordinaire. I’ve blogged previously about the impact he had on me and dozens of other writers he encouraged, cajoled, and at times berated when we needed a kick in the pants to get us writing again.

Terry not only motivated me to keep going even when the words didn’t come together satisfactorily, he gave me a template for helping other writers: never tell someone how to write a character or scene but instead encourage them to remember why they were writing in the first place and what they wanted to say. Counseling about the business side of writing could flow more freely, because that was about strategy and probability rather than creativity. Every few days, a writer reaches out to me for advice; I try to respond as soon as possible because that’s what Terry always did for me.

As I launch my 33rd Atlanta Writers Conference—which has enabled innumerable writers move toward their publishing goals and sometimes achieve their wildest dreams—and now oversee a mentorship program that will help many more writers than I could ever assist individually, I realize that things did indeed happen just as they were meant to. My early frustrations and false starts primed me to be a healthy skeptic about taking other authors’ advice but also helped me to recognize a mentor who was the real deal. And those experiences opened me up to finding ways to help more and more writers avoid pitfalls and get on the fast track to realizing their ambitions.

I’ve told many people, “When I grow up, I want to be like Terry Kay.” Maybe as I close in on age 60, I’m taking some baby steps within the giant footprints he left behind.

The post Baby Steps within the Footprints of a Giant appeared first on George Weinstein.

April 15, 2025

Book Selling in Grocery Stores vs. Bookstores

Thanks to the national Authors in Grocery Stores Program, I’m now able to hand sell my Hardscrabble Road series in Kroger supermarkets across Georgia. Nothing can take the place of talking about reading favorite genres with faithful bookstore patrons—who are there because they love books and enjoy meeting the people who write them—but arranging signings in bookstores can be difficult, and they sometimes struggle to attract a lot of foot traffic, whereas a supermarket in a busy part of town always has people walking in. Having done numerous signings in both venues, I’ve observed some interesting differences between grocery store customers and those who frequent the bookstores where I usually sign with my wife, author Kim Conrey.

First, the Kroger customers I manage to talk to are almost universally surprised and often delighted to find an author at a table between the produce and florist sections doing a signing. Bookstores customers, by contrast, are accustomed to seeing writers flogging their wares. Some bookstores host one or more signings every week; we’re a common sight in those outlets.

The flip side is that the vast majority of grocery store customers reflect most American consumers: either they don’t like reading or don’t have the time. While some bookstore customers might be only shopping for the non-book tchotchkes that help pay the shop’s rent, Kim and I seldom hear “I don’t like to read” except from relationship partners trailing their book-loving better-halves. The irony of doing signings in supermarkets, then, is that, while I’ll encounter 100+ more potential buyers of my work in a Kroger than in a bookstore, the rejection rate is far higher as well.

As a writer for the past 25 years and a published author for the last 13 years, I’ve grown thick skin, but, even so, being told by the multitudes that what you do doesn’t matter to them (or shown this via a rapid turn of a grocery cart and studious lack of eye contact) can be discouraging. It makes encountering a grocery shopper who also craves books an extra special event. They seem to be even more excited about their purchase of a signed copy than those in bookstores. When they were making out their shopping list that morning, none of them had written down “book,” but there they were, buying a copy for themselves or for family or a friend. If you go to a bookstore, you expect to buy books; getting an inscribed, autographed copy is a bonus, but you’re counting on getting something with lots of pages between two covers—not so the Kroger customer. Their enthusiasm more than makes up for all the rejection.

Another difference is pace. The average supermarket shopper is on a mission, whereas the typical bookstore customer is browsing or maybe even just killing time. “Shopping” is done at two very different speeds at these two kinds of retailers. I’ve seen some bookstore customers spend a full hour in browse mode and leave empty-handed—perhaps intentionally—but I seldom see a grocery store shopper walk out without at least a purchase or two in hand. Their hurried pace makes the rejection rate even higher: even if they like reading, they’ve told me, they don’t have time to listen to my spiel. But those who do pause to speak with me are much more likely to buy my work than is the bookstore patron who’s surrounded by thousands of other reading choices to consider on the shelves and tables around us.

Doing book signings in any kind of retail environment—from bookstores and supermarkets to craft fairs and festivals—is not for the easily discouraged or faint-hearted. The chance to talk to potential readers about what I’ve written is a privilege anywhere, but while the sales I get at the grocery store are fewer and further between than at bookstores, they’re harder won and can be that much more satisfying.

If you’re an author and interested in the Authors in Grocery Stores Program, click here, and if you sign up, please put AtlantaWC on the referral line so the Atlanta Writers Club will get credit.

The post Book Selling in Grocery Stores vs. Bookstores appeared first on George Weinstein.

February 8, 2025

It’s All about Soul—Until It’s Not

As artificial intelligence continues to shape the landscape of literature, a compelling question arises: do readers care whether a text was written by AI? The answer depends on the reader’s expectations. Many may still prefer the “human touch”—the nuances, the imperfections, the lived experience that seem inherently absent in machine-generated content. Yet, as AI-generated texts improve in quality, the lines blur. Some readers might struggle to distinguish between an AI’s prose and that of a human, especially in more formulaic or genre-driven writing.

However, it’s not just about technical ability. Readers engage with literature on a deeper, emotional level. The question isn’t merely whether AI can mimic human style, but whether it can evoke authentic emotional resonance. While AI may excel at structure, its capacity for profound, lived experience—something inherently human—remains its greatest limitation. In the end, the value of a text lies less in its origin than in its ability to connect with the reader.

The two paragraphs above were written by ChatGPT based on a prompt I entered. Could you tell? I confess I wouldn’t have known that if I hadn’t done the prompting. It reads well, with few echoes or other literary problems that could make the text sound clunky, and no grammatical or punctuation errors. There’s an awkward jump between the penultimate and final sentence, but the ending connects back to the beginning in a compelling way. Overall, a solid 160 words—which is really scary for authors like me, who were convinced only a short time ago that AI-generated writing would come off as stilted and, well, robotic. In other words, we thought AI wouldn’t offer any real competition to creative types.

Time for a reckoning. I’m convinced that writing novels—a craft that one never really masters, where each book is a unique challenge—could now be, or at least will soon be, within the competent domain of artificial intelligence and the individuals who supply it with fine-tuned prompts. And that output might well be better than what I could produce. Better than the best scene I’ve ever written? Maybe, maybe not, but probably better than many that I’ve written.

It’s conceivable that we’ll soon have entire books written in the style of any famous author you can name. The estates of deceased, popular authors might commission those instead of hiring real people to continue that legacy and, more likely, new writers who want to become known as the next JRR Tolkien or whomever will put these AI tools to use. They’ll produce books in minutes or entire series in an hour that echo the desired style, slap their name on them with attractive AI-generated covers, and put them online for sale without even reading them through. Who has time for that? What they want is easy work—and maybe they’ll even sell some copies. Meanwhile, I’ll still be laboring on the pivot from Chapter 23 to Chapter 24 to make sure it strikes just the right chord of tension and dramatic irony, with the completion date for that book still a matter of speculation.

As with “deepfake” videos, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to tell whether a work is genuine—created solely from the imagination and skills of a writer—or produced by a machine trained on millions of books to regurgitate something “new.” A small company called Spine was launched in 2024 with a pledge to give readers over 8,000 AI-generated books this year alone. For comparison purposes, a Big Five publisher might produce 10,000 books a year but with huge staffs and numerous freelancers working long hours to manage that.

Book covers are increasingly made using AI graphics apps rather than depending on the creativity and skill of old-fashioned cover artists. AI narration tools can make an audiobook sound like it’s being read by any actor or other public figure. It’s a bad time to be a cover designer or an audiobook narrator. I love the work done by the narrators who’ve produced my audiobooks, and I’d use them again in a heartbeat, but how can they realistically compete in the marketplace against software that will not only give listeners the late, great James Earl Jones or any other distinctive voice but do so for free or only a small subscription fee?

For writers, book artists, narrators, we need to remind ourselves like a daily mantra that we do this for the love of being creative, for the sheer joy we feel bringing a story to life, not because of any potential monetary gain. There’s already precious little profit for most of us, and—if the scenario I’ve described above comes to pass—there could be even less still to go around.

Beyond the issue of making a living as a creative, though, competition for readers’ attention because of all these technological marvels will become that much fiercer, and the chance of an original, genre-changing talent rising above the noise will become less likely. Readers will find even more variety, of course, but will it soon become nearly impossible to discern what was written with soul…until that no longer matters to most people?

The post It’s All about Soul—Until It’s Not appeared first on George Weinstein.

November 24, 2024

A Meditation on Book Research

New writers seeking inspiration are often instructed to “write what you know.” I think that’s terrible advice because if you only write what you know, sooner or later (very soon, in my case) you’ll run out of things to write about.

Instead, I encourage writers to “write what you can find out,” just as I encourage readers to seek out books that will educate as well as entertain.

We live in the golden age of research, thanks to the internet and now artificial intelligence, which can help you discover all sorts of facts backed up with citations, if you provide effective prompts. For me, though, nothing beats what journalists, biographers, and the merely curious have always relied on: interviewing primary sources.

The reason my Southern historical novel Hardscrabble Road and its sequel Return to Hardscrabble Road ring true for numerous readers is that many of the stories related in those two novels really happened and were conveyed to me by the individuals (primarily Bud but also his two older brothers and older sister) who took action or survived the actions taken against them. In the case of Bud, I wrote down his stories for a decade and then interviewed him over the course of two more years so I could also capture his sense memories—the ways things smelled, tasted, felt, etc. I think these details are more important than the actions themselves, because sensory descriptions hold readers’ attention in a scene. They help us imagine what’s going on at a gut level. We experience those five senses while we’re reading as if we are there. That’s the magic of reading and why movies and TV can never duplicate the power of our imagination, no matter how hard they try (“Smell-O-Vision” anyone?).

Even for those writing sci-fi or fantasy set in mythical kingdoms or far-off planets, research is vital. We must ensure that readers continue to suspend their disbelief. Even invented worlds need to abide by consistent physical rules or magic systems. And interviews can play a role here as well—not only speaking with experts in physics, for example, but also talking with those who have experienced the kind of things you’re writing about. No one can tell you how they survived a starship dogfight or a melee with trolls wielding medieval weaponry, but veterans of combat can absolutely tell you what it feels like to fight for your life and see/hear/smell/taste/feel those around you lose that battle.

There is, of course, the danger of the research rabbit hole, that feeling that you never have quite enough details to write convincingly about anything. To retain momentum as they’re crafting scenes, many writers simply put brackets around some word prompts, like “[clothes]” to remind them to go back and figure out how someone in the designated place and time would be dressed. This technique keeps them from stopping every sentence or two to gather more facts: looking up one thing tends to beget researching something else. Thus, you can begin with a question about 17th century pants in New England and find yourself immersed in the tannery process and the art of dyeing clothing.

The writer must also resist including 95%-99% of all the research they did. We’ve all read books where the writer sacrificed the momentum of their story for a show-and-tell that revealed just how much they learned about a given subject. Save that stuff for the super-fan annotated special edition and get on with the show.

The point of all this research, of course, is to captivate readers. In my experience, there are two types of readers: a small minority who just want to escape into the same kind of story over and over and the vast majority who want to learn new things, discover surprising aspects of life, and encounter unexpected people and situations. This latter group delights in the research details writers sprinkle throughout their stories. These readers want to be transported to the writer’s world, be it an ultrarealistic recreation of an actual place and time or a fantastical land far from our reality.

In the end, the story is always more important than the research. But compelling details uncovered through diligent interviews or careful study can take a commonplace story and make it sing.

The post A Meditation on Book Research appeared first on George Weinstein.

August 11, 2024

Don’t Listen When You’re Told No One Will Care

Many of you have heard my backstory about Hardscrabble Road: I spent ten years writing down the brutal, often horrifying, but always compelling childhood stories of my former father-in-law—who was “Bud,” if you’ve read the book and the sequel Return to Hardscrabble Road—and his two older brothers and older sister. When I approached Bud about helping me shape those stories into a novel by sharing his sensory memories of those bygone days, he told me not to waste my time because no one would care. That opinion was an informed one:

No one cared enough to stop his psychopathic father from beating and terrorizing Bud and his brothers.

No one cared when Papa tried to murder Bud’s mother (even the court barely cared, sentencing the horrible man to just a few years in prison).

No one cared (except for Bud’s favorite teacher) when he and his brothers dropped out of school one by one to work in a sawmill and do predawn bread deliveries to feed their family and keep a rented roof over their heads.

I cared, though, and I finally convinced him to help me. I finished writing Hardscrabble Road twenty years ago and sent it to my agent, who was excited to have something new of mine to send to the big publishers. She couldn’t get anyone to care about my first novel, The Five Destinies of Carlos Moreno, but thought this one would resonate.

But Bud was right: no one cared. We didn’t get a publishing contract for Hardscrabble, Five Destinies, or my domestic drama The Caretaker. I eventually fired that agent and focused on helping other writers on their journeys.

A chance meeting with a small, local publisher resulted in Hardscrabble Road being published in 2012. And you know what? Individual readers cared. Book clubs cared. Most of the 5,000+ people who’ve left reviews online for the book since then cared. Bud didn’t survive long enough to see the book in print (that’s him on the cover in 1936, holding out a can of worms to his middle brother), but I hope he knows that people cared.

And somehow, twelve years, six more books, and two more publishers since then, Hardscrabble continues to be the one that outsells all my other titles combined. My wife, author Kim Conrey, and I just did a signing at the beautiful Poe & Co. Bookstore in Milton, GA, which displayed all my books, but which one did I sell? You guessed it. We’ll go to DragonCon in a few weeks, where sci-fi and fantasy rule, but my satirical pre-apocalyptic comedy Offlining tailored for that audience probably won’t sell as well as the Southern, historical gothic Hardscrabble.

What’s the moral of all this? If you have a story in you and you’re telling yourself not to bother writing it because no one will care, think again. If you want to tell stories from your own life to family or friends so they’ll understand you better, but you haven’t done so because you don’t think they’ll care, think again. If you haven’t shared your views or your news on social media because who would care, think again.

Bud was a brilliant man and, I imagine, the most resilient, optimistic child who ever picked cotton and hoed peanuts from dark-thirty to dark-thirty. He once told me, “There’s nothing stranger than people, and you’ll never understand them,” because of the terrible man and disinterested woman who raised him and the various odd characters he encountered in his adult life. Clearly, though, he didn’t understand readers and couldn’t imagine their affinity for his childhood tale, but I’ve witnessed it first-hand for a dozen years and counting. And readers are now telling me they enjoy Return to Hardscrabble Road even more because Bud is coming into his own and has agency (he’s on the far right on that cover).

So, tell or write your story. Don’t be afraid to share it. You just might be surprised who will care.

The post Don’t Listen When You’re Told No One Will Care appeared first on George Weinstein.

February 26, 2024

We Live in a Two-Story House

Sharon Thomason, Featured Authors Chair of the Dahlonega Literary Festival, conceived this wonderful title when pitching a talk for me and my wife, author Kim Conrey, to do about what it’s like to live in a home with two writers. We’ll offer that presentation on March 2, 2024, at 11:00 a.m. during the festival. In preparation, here are my initial thoughts about this atypical arrangement.

Living in a “two-story” house can be summed up with three C’s:

1. Collaboration – in writing, marketing, and presenting

2. Commiseration – about uncharitable reviews, dips in sales, and other setbacks

3. Celebration – sharing large and small wins together

Talk about being in bed together…we’re collaborating in all sorts of ways! Each of us always has a critique partner to offer feedback about what’s working and what could use some more attention. For Kim, I’m the story whisperer, offering plot suggestions that can advance the story while building on her characters’ development. For me, Kim is my characters’ emotional and spiritual adviser, focusing on ways in which I can more fully develop their inner lives, so that their outer struggles will mean more to the reader.

We’re also in business with each other, publishing our books through our private imprint Soul Source Press, and now we’re collaborating in the traditional sense: we’re writing a new book together! Combining her experiences growing up in a backwoods Pentecostal church in way-west Georgia—with demons being prayed out of her at every turn, pew-walking, and speaking in tongues—with my love of mysteries and thrillers, we’re working on a cozy mystery series we’re calling the Southern Fried Nonsense Mysteries. The first book concerns a woman hired by her west Georgia hometown to turn an abandoned church into an arts center. Unfortunately, this earns her the scorn of those convinced she’s desecrating their temple, and the skeleton she discovers in the basement puts more than her livelihood in jeopardy. In this version of collaboration, we’re living in a one-story house!

In addition, we help each other with marketing tips and tricks, with one of us acting as a guinea pig to set a budget, spend some money, and see whether the results were worth it before the other one takes the plunge. “Your mileage may vary” is a common experience with these things.

And we also regularly present together at writing events and literary festivals. We’ll be doing the aforementioned “Two-Story House” talk along with a “Paths to Publication” workshop at the Dahlonega Literary Festival. At the Carrollton BookFest in April, we’ll discuss publishing again, and later that month, we’ll be at the Red Clay Writers Conference doing a tandem talk on the lessons we’ve learned from two decades in the book business.

Commiseration is a seldom-discussed topic among writers, but venting is something we all need to do, and it helps to rail and gnash teeth when your listener is someone who understands and can offer insights and empathy rather than a helpless tsk-tsking. Kim and I commiserate when an anonymous doofus leaves a one-star review because they thought the book was well-written, but it just wasn’t for them or presents some other bizarre, twisted logic that will forever pull down the average rating of our labor of love. We’ll go days without selling a book online or the event we attend doesn’t attract book buyers or any number of other things that make a difficult job—selling our art—that much harder.

But sometimes unexpected, good things happen—Kim won the 2023 Georgia Author of the Year in the romance category for her sci-fi romance Stealing Ares and my historical novel Hardscrabble Road notched its 3,000th review while maintaining a 4.4 average rating and its 2022 sequel, Return to Hardscrabble Road, is already closing in on 400 reviews with a 4.2 average—and we each have someone who truly understands and appreciated the achievement. Or, one of us (usually Kim, as she’s a much faster writer) finishes a manuscript, and we get to celebrate that milestone. For a time, those things we were commiserating about only a day or two beforehand hold less sway over our emotions, and we can feel good about our own and each other’s success on a journey with precious few such markers.

What does this mean for you? Think about your hobby or subject of interest and find your tribe of like-minded enthusiasts—or just one person who “gets” you—and you, too, will have someone to collaborate, commiserate, and celebrate with. If you’re among the lucky few like Kim and me, you can even create a partnership that becomes your whole world and makes your two-story house a home.

The post We Live in a Two-Story House appeared first on George Weinstein.

November 13, 2023

For Writers: Reconsidering Paths to Publication

If you read my other blogpost this month, you’ll know that I’ve had to reclaim the copyrights to all my titles, labor to remove my former publisher’s editions of those books on Amazon and the distributor Ingram, and then self-publish updated editions with new ISBNs and tweaked covers.

Why didn’t I try to find another traditional publisher, as I did after the tribulations with my first publisher, where my books spent a year in limbo before being republished by the now-defunct SFK Press? Don’t I run a traditional publishing conference twice a year for the Atlanta Writers Club, which promotes the benefits of signing with literary agents or directly with publishers?

I still believe traditional publishing is a worthwhile avenue for authors who are interested in getting a lucrative advance against future royalties, seeing their books in stores across the US and beyond, garnering reviews from Publisher’s Weekly and other famed literary magazines, receiving blurbs from popular authors, and/or benefiting from the publisher’s marketing efforts. Some traditional publishers offer all these benefits; others provide one or two; many don’t do any of that but at least give one the peace of mind knowing that someone else deemed one’s work as worthy and was willing to invest their time and money to publish it.

These are all totally legitimate reasons to seek out an agent in hopes of landing a big publisher or go directly to a smaller publisher. Speed, however, is something traditional publishing can’t offer. And I wanted to get my books back on the market quickly. I’m not getting any younger, and I don’t have the patience I did back when I decided to wait until I could secure a second traditional publishing deal. Another virtue of self-publishing is visibility of sales. I get reports daily from Amazon, Ingram, and ACX (for the audiobook versions) showing me exactly how many editions were purchased and, in the case of the ebooks, how many pages were read (for Kindle Unlimited subscriptions, the author gets paid based on page-reads). I know at any given time whether and how many of my books are selling, which I never knew when I was traditionally published. Before, I could only speculate about whether I made any money on a given day—now I know.

The downside of all this visibility is the urge to do something. I can see which books aren’t selling at any given time, and I want to post ads on Amazon and Facebook, apply for a BookBub Featured Deal, do a BookTok post, offer a Goodreads giveaway to garner some reviews…DO SOMETHING. When I was traditionally published, I could guess how my books were faring based on daily fluctuations in my Amazon sales rankings and dream about what kind of royalty check I’d get in the months to come. Now, I know exactly how flat or robust sales are, so I can’t pretend any longer.

Yes, it’s better to know than be in the dark. However, to paraphrase Spider-Man’s uncle, with great knowledge comes great responsibility. If I don’t do anything to goose sales, it’s my fault when there aren’t any purchases. Before, I could gripe about my publisher’s lack of action, but I no longer have that scapegoat. If book sales flourish, I can claim credit. Equally, if my books fail to sell, that’s solely on me too. I’ve never been so acutely aware of my personal responsibility in this. Of course, I can still create excuses by the score if my book sales are abysmal, but in my heart, I know the fault does not lie within my stars.

This is a humbling aspect of self-publishing that I understood only intellectually before. Now I feel it bone-deep every day. So, if you’ll excuse me, I have to go DO SOMETHING!

The post For Writers: Reconsidering Paths to Publication appeared first on George Weinstein.

Back in Business

The reason I began these blogposts years ago was to give readers an understanding and appreciation for the craft of writing—the creative process—and the business of writing with its myriad idiosyncrasies and disfunctions.

I haven’t contributed any blogposts recently because of one such dysfunction: the instability of the publishing business. My latest publisher, Southern Fried Karma (SFK) Press, closed its doors this summer. I went to SFK after my first publisher stopped paying the royalties they owed me, and now this. Publishing others’ books is a tough way to make a buck.

Thus, I spent the last three months getting my rights back, having all my books removed from Amazon and the worldwide book distributor Ingram, getting updated covers and new interior layouts created, and uploading everything again as self-published editions using the Soul Source Press name that my wife, author Kim Conrey, and I launched earlier this year. Quite the marathon just to be able to sell the same books again, but at least all the money now comes to us.

The experience has forced me to reflect on issues of trust and loyalty, inertia and motivation. Both publishers I’d worked with were eager to get my books on the market and start racking up sales, but neither had been timely in their payments. This was a red flag I chose to ignore because I liked both the guys who founded their presses. I hung out with them, met and worked with their families—in both cases, several family members had roles in the business—and helped them recruit other clients by referring writers I knew. When royalty payments started to arrive later and later, and often only after nudging from me, I excused their tardiness because I understood how hard it was to run a small business. Whenever I had a new book completed, I considered going elsewhere, but there was that issue of loyalty. “Stay true, have faith, and everything will work out”: it looks good embroidered on a throw pillow, but such a philosophy often burns us in business dealings. “Fool me twice, shame on me” is more appropriate. Though it looks a little cynical on that hypothetical pillow.

My excuse for not going elsewhere was being extraordinarily busy in every other aspect of my life, and it was just easier to keep doing the same thing and expecting different results—we all know how that story ends. With my first publisher, it took them ceasing to respond to my nudges about past-due royalties to motivate me to threaten to sue them for breach of contract and demand my rights back. They ended up paying me with warehoused copies of my books. With SFK, the publisher decided to close his doors because I was the only author making him money, and the thrill was gone. So now I’m a purely self-published author.

Some advantages of self-publishing also involve trust, loyalty, and motivation. I don’t need to trust and be loyal to anyone but myself and my readers—there’s no one to string me along or lead me astray. Staying motivated is easy because I can see the results of my advertising efforts every day—versus when I was traditionally published, where the publisher had that information, not me (and did precious little to get the word out, even though they had the motivation to act). Inertia means no sales, so it’s an easy formula.

For readers, the upshot of all this is you can be assured that any purchases going forward will be supporting the creator of the work rather than an anonymous publisher who might or might not be sending royalties. I promise you that I’ll focus even more on producing quality reading experiences. Currently, I have four projects I want to complete, ranging from historical fiction to a contemporary Southern novel I’m cowriting with Kim.

It’s just another chapter in a grand adventure. We’ll see what happens next together!

The post Back in Business appeared first on George Weinstein.