Ian Plenderleith's Blog

November 30, 2021

Open Wide For Some Soccer podcast

Thanks to David McKenzie and former Diplomats and Cosmos defender Bob Iarusci for having me on the latest episode of their excellent NASL podcast,

Open Wide For Some Soccer

. You can hear the episode here. Among the topics discussed were:* What inspired me to write a book about the NASL

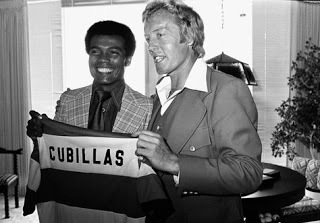

Celeb meets star* How I came up with the title for the book* Why the MLS is disrespectful to the history of the NASL * Indications that people are still interested in the league * The US’ involvement in bidding for the 1986 FIFA World Cup * Decisions to market Pelé while perhaps forgetting some other deserving players * Other mistakes made when trying to promote the league * Celebrity appearances and their help (or not) in growing the game in the US * Gimmicks used to promote the NASL and why I was a fan of them * The corruption of FIFA * Why Bob used to have to spray paint his shoes white before every game * Improvements that MLS has made in marketing the sport * Why Geoff Barnett decided not to play for the Cosmos * The merging together of playing styles throughout the world * Where the NASL has had its most influence on American soccer * The increased interest of international scouts towards North America

Celeb meets star* How I came up with the title for the book* Why the MLS is disrespectful to the history of the NASL * Indications that people are still interested in the league * The US’ involvement in bidding for the 1986 FIFA World Cup * Decisions to market Pelé while perhaps forgetting some other deserving players * Other mistakes made when trying to promote the league * Celebrity appearances and their help (or not) in growing the game in the US * Gimmicks used to promote the NASL and why I was a fan of them * The corruption of FIFA * Why Bob used to have to spray paint his shoes white before every game * Improvements that MLS has made in marketing the sport * Why Geoff Barnett decided not to play for the Cosmos * The merging together of playing styles throughout the world * Where the NASL has had its most influence on American soccer * The increased interest of international scouts towards North America

Celeb meets star* How I came up with the title for the book* Why the MLS is disrespectful to the history of the NASL * Indications that people are still interested in the league * The US’ involvement in bidding for the 1986 FIFA World Cup * Decisions to market Pelé while perhaps forgetting some other deserving players * Other mistakes made when trying to promote the league * Celebrity appearances and their help (or not) in growing the game in the US * Gimmicks used to promote the NASL and why I was a fan of them * The corruption of FIFA * Why Bob used to have to spray paint his shoes white before every game * Improvements that MLS has made in marketing the sport * Why Geoff Barnett decided not to play for the Cosmos * The merging together of playing styles throughout the world * Where the NASL has had its most influence on American soccer * The increased interest of international scouts towards North America

Celeb meets star* How I came up with the title for the book* Why the MLS is disrespectful to the history of the NASL * Indications that people are still interested in the league * The US’ involvement in bidding for the 1986 FIFA World Cup * Decisions to market Pelé while perhaps forgetting some other deserving players * Other mistakes made when trying to promote the league * Celebrity appearances and their help (or not) in growing the game in the US * Gimmicks used to promote the NASL and why I was a fan of them * The corruption of FIFA * Why Bob used to have to spray paint his shoes white before every game * Improvements that MLS has made in marketing the sport * Why Geoff Barnett decided not to play for the Cosmos * The merging together of playing styles throughout the world * Where the NASL has had its most influence on American soccer * The increased interest of international scouts towards North America

Published on November 30, 2021 08:43

December 12, 2018

"I love that!" When your book gets a nationwide plug, but no credit

Overstocked, undersold.Considering the number of soccer fans in North America, sales of 'Rock n Roll Soccer' in the continent have been, frankly, more than disappointing. As a writer, you can rationalise a book's failure in order to distract yourself from a creeping insecurity about your own abilities. That is, you find someone or something else to blame besides yourself. The following reasons, I've speculated, may all be the cause of public indifference to an analysis and history of the North American Soccer League:

Overstocked, undersold.Considering the number of soccer fans in North America, sales of 'Rock n Roll Soccer' in the continent have been, frankly, more than disappointing. As a writer, you can rationalise a book's failure in order to distract yourself from a creeping insecurity about your own abilities. That is, you find someone or something else to blame besides yourself. The following reasons, I've speculated, may all be the cause of public indifference to an analysis and history of the North American Soccer League:- a very poor publicity effort by the publisher, St. Martin's Press. "If it's not made the NY Bestsellers' List in two weeks, publishers lose interest," an insider told me. They certainly did. A planned book tour was supported in theory, but not with anything as helpful as cash or staff.

- sparse coverage from the mainstream sports media. All the major national print and broadcast outlets ignored the book - no surprise, given my lack of both fame and extensive contacts. The author's name is often way more important than the contents of their book. An old buddy from the press box? Sure, we'll mention your book! Known for spouting off shite on social media to several thousand followers? You're in!

- a lack of interest in North America's soccer history both among fans (see book sales) and teams - not a single Major League Soccer or NASL Mark 2 club was interested in or, in most cases, even had the courtesy to respond to my requests to host a reading. Even though this lack of interest was, ironically, something that the book sought to rectify. This may be down to the fragmented nature of US soccer history, or it may be due to the relentlessly forward-looking norms of a sport that still considers itself to be on the rise.

The 50th anniversary of the NASL's kick-off this year and the rapid success of MLS new boys Atlanta United may both have been a potential peg to revive interest in the subject, but I've lost so much money on the book by now that it hasn't been worth the risk of investing more unpaid time. Still, I was intrigued to see an interview run by the Associated Press last week with the former chief executive of NASL co-founders the Atlanta Chiefs, Dick Cecil, that ran across several media. Including the Washington Post and the New York Times, both of whom ignored 'Rock n Roll Soccer'.

Around two-thirds of the way through the piece, the writer Paul Newberry mentions how the Chiefs achieved some measure of international fame in their first year by twice beating English champions Manchester City. I quote, without permission:

Cecil gleefully pulls out a book about the history of the NASL.“Look at the title of the first chapter,” he says.I thumb quickly to the table of contents.“Atlanta, Champions of England,” it says.“I love that!” Cecil says, erupting in a laugh pulled straight from the belly.

"I love that!" My book! But the Associated Press doesn't cite the title of the book, doesn't mention the name of the author. I continue reading to the end of the interview, feeling that I am waving goodbye to a ship that was supposed to take me off the island, but which is now steaming over the horizon without a backward glance. Is there anything left for me to eat on the island? I turn around, and there are on the beach are several piles of unsold copies of 'Rock n Roll Soccer'...

"I love that!" My book! But the Associated Press doesn't cite the title of the book, doesn't mention the name of the author. I continue reading to the end of the interview, feeling that I am waving goodbye to a ship that was supposed to take me off the island, but which is now steaming over the horizon without a backward glance. Is there anything left for me to eat on the island? I turn around, and there are on the beach are several piles of unsold copies of 'Rock n Roll Soccer'...The publisher did write to me last year and offer me its "overstock" of 697 copies at a not particularly bargain price. Otherwise, their fate was unclear - pulped or remaindered? I suggested that they should be donated to the libraries of the country's state and federal prisons, which more than outnumber the overstocked books. They must still be thinking about that option, as I've yet to receive a reply.

'Rock n Roll Soccer' is still available here for $11.98. The author's latest book, 'The Quiet Fan', is available in the US here from amazon, and in the UK from When Saturday Comes magazine.

Published on December 12, 2018 01:01

August 29, 2018

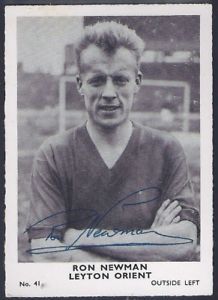

Ron Newman: 1936-2018. "When the NASL folded I was sitting in my office crying my eyes out"

I was saddened to hear of the death on Monday of former North American Soccer League player and coach, Ron Newman. Five years ago this week I talked to Ron, who granted me an extensive and entertaining interview about his time in the NASL. Many extracts from that interview ended up in Rock n Roll Soccer (he has 12 referrals in the book's index), but much of it has remained on my hard drive.

I was saddened to hear of the death on Monday of former North American Soccer League player and coach, Ron Newman. Five years ago this week I talked to Ron, who granted me an extensive and entertaining interview about his time in the NASL. Many extracts from that interview ended up in Rock n Roll Soccer (he has 12 referrals in the book's index), but much of it has remained on my hard drive.In tribute to a kind and generous man who gave so much to the game in the US, here is the interview in full:

What brought you to the USA and the Atlanta Chiefs in 1967 ?

Ron Newman : I was sold by Portsmouth to Orient and through the club I took over this house where [future NASL Commissioner] Phil Woosnam had been living while he was at West Ham. I used to get his post and send it on to him, though I didn’t know him. We got talking one time in the players’ tunnel and had quite a long chat. Now when I was in the army I was a drill instructor, so I knew how to handle people, and when my career started to wind down I thought I wouldn’t mind a go at coaching. Eddie Firmani was talking to me about coaching abroad in Australia or South Africa. But then I got a call from Phil and he said, ‘Don’t go to South Africa, come with me to America.’ I said, ‘America? They can’t play the bloody game over there!’But I talked about it with the kids and we ended up going, all because of that link up with the house where we’d both lived.

What was it like that first year in Atlanta?

Newman : Everything was new. Everything was huge. Right in the beginning I’d met the people from Atlanta in a hotel in London, and we had lobster. I’d never had lobster before, we couldn’t afford that. This of course was the baseball people. My son, who was about eight, had just started playing soccer and he didn’t want to go because there was no soccer in Atlanta. We told him they had hamburgers and colour television over there, so that persuaded him. When I got to Atlanta I told him we were

We put an ad in the paper and a whole load of kids showed up and I thought, 'Bloody hell, what am I going to do with this lot?' But in no time at all we started a league. But then we had to find balls, refs, a place to play and I thought, ‘What have I got myself into?’ I’d worked five or six years in the docks as an apprentice and so I was a carpenter. I used to joke that there had been two very important carpenters in history – Jesus Christ and me. So I got the job of making a set of goalposts, because there were no goals. Then Saturday morning came around, but somebody had ripped the goalposts down and broken them into bits. Anyway, we hammered in two goals in the end without a cross-bar, but that was the start of my exploits in seeing what had to be done in a country like the US. There was nothing there. Nothing. But after a year things got bigger and more kids came around, it grew and grew. When I left for Dallas after a couple of years I handed it over to the YMCA and they started the Summer Soccer League. Years later I met a taxi driver in Dallas who’d played in that very league! And that’s what I ended up doing everywhere I went in the US.

In the US we were always trying to sell the game, always trying to give people a reason why they should play it. We’d go to clinics and schools, and Phil asked me to go to one place about three hours south of Atlanta. The headmistress was so grateful that I’d come, she was telling me how fantastic it was that I’d come. Then she says, ‘You know, we’re fascinated to know, how do you guys manage to stand up on those skates?’She thought I was from an ice hockey team. You’d go to schools and they wanted you to put the ball between the American football posts like a place kicker. You’d do it with your right foot and then with your left and they’d be really impressed by that.

We hadn’t been there a week in Atlanta when they had a big parade downtown. So we put a float in the display, but we had nothing on it to say who we were, though we managed to get some uniforms, but it didn’t say on the shirts who we were. So we were waiting to start, with 1000s on the sidewalk, but no one knew who we were. So I took a ball, jumped off the float, which was an absolute no-no, and I started playing 1-2s with all the people on the sidewalk.

We hadn’t been there a week in Atlanta when they had a big parade downtown. So we put a float in the display, but we had nothing on it to say who we were, though we managed to get some uniforms, but it didn’t say on the shirts who we were. So we were waiting to start, with 1000s on the sidewalk, but no one knew who we were. So I took a ball, jumped off the float, which was an absolute no-no, and I started playing 1-2s with all the people on the sidewalk. Bob Bell at San Diego once said to me, ‘Every game has to appear to be important’. You’ve got to do something to make people excited about coming. Good or bad, as long as it causes a stir.Our league was divided into regional conferences, so you were never far from the top or the bottom, and any intra-conference game was important anyway. I looked across at England and they’d got it all wrong over there. You’d have two or three months of the season left and none of the games had any consequence any more if you were mid-table. Now [in England] they’ve found a way to make more positions at the top and the bottom of the league important with the playoffs and finals at Wembley with huge crowds.

I thought the English game in the 70s was going to go belly up. The stadiums they had in England at that time weren’t anything like as good as the ones we played in over here.

[Former Atlanta Chiefs Chief Executive] Dick Cecil and [former NASL player and coach] Dave Chadwick both told me you took the missionary philosophy from Atlanta with you and spread it across the country.

Newman : I did, and it was so easy. Selling soccer in this country was like selling five dollar bills for a dollar. Once people saw it worked, they couldn’t get enough of it. It was hard work, but easy. You’d go to a school and make a good impression, and they’d recommend you to another school down the road and you’d go there too, and it just spiralled like that. The game grew so fast. I had a little piece of paper and explained about who I was and about the game of soccer. The key was at the bottom of that piece of paper - this is a new enterprise, I need help from older brothers, parents, people to coach, referee, organise the team and so on. That was the secret – there were kids, kids, kids all over the place, but you needed the parents.

What sort of promotions did you use to sell the NASL when you became coach with the Dallas Tornado in 1969?

Newman : Parades, doing these things in schools, I had a funny accent that appealed to them all. I couldn’t juggle the ball when I was in England as a pro, but I got so much practice there doing demos that I became a good juggler. I’d explain the difference between soccer and US sports: you can come and get the ball if you want, come and kick it – it wasn’t like American football and basketball where you couldn’t really take the ball off the other team. ‘It’s all yours, come and get it if you want, anyone can try and get it.’

I remember going to the first National Coaches’ Convention up in New York and you’d make contacts and people gave speeches and you’d buy some equipment from a bloke with a suitcase. That thing grew to enormous size. Can you imagine the first one? It was pathetic. So anyway, I was doing a clinic in Dallas, doing a demo of bending the ball and so forth. I was showing them how to elevate the ball, and to demonstrate that I’d hit the basketball board with a ball in the air. Well this time the ball went through the net without touching the sides. A Brazilian player from the Tornado who was with me started shouting, 'Pelé! Pelé!' And all the kids in the bleachers are sitting there watching and one of them says, 'Do it again!' So I was at the coaches’ convention a few years back and a guy at one of the stands stopped me and asked me if I was Ron Newman. He wanted his picture taken with me because he remembered that clinic in Dallas, and he remembered me putting it through the basketball net. And he was the same kid who’d yelled out ‘Do it again!’

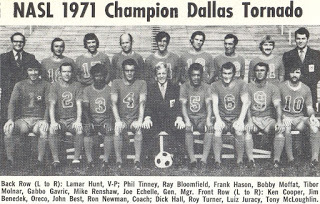

What were the challenges of coaching Dallas in the early 70s and what was your relationship was like to its owner, Lamar Hunt?

Newman : I was MVP at Atlanta, and they were a very good side with some very good players. I was injured for the Manchester City games in 68 [when Atlanta beat the reigning English champions twice], but I remember the games, they were terrific.

At that time I had just recovered from my injury and was offered this opportunity in Dallas where they’d fired the coach and called in Keith Spurgeon, ex-Tottenham, and he was in Belgium, and he was looking for someone to help him as an assistant with a little bit of experience of the US. But then at the end of the 68 season the league shrunk down to five teams, and I could have done what a lot of players did – gone out to play golf while the remaining teams decided what to do. Keith went back to Europe, but I thought, if we do go forward for another season… Lamar was a magnificent man, a great believer in the game, he wanted [his team] to play. So I went back out into the schools.

It was a learning curve for me as a coach. At the end of the 1970 season we had no chance of winning the league, so for the last few games I experimented with the line-up in preparation for the following year, and of course we lost those games, but I didn’t think anything of it because they weren’t important. Yet the media were asking me, ‘Do you think you’ll lose your job?’ And I was thinking, I’m busting my balls here trying to keep this new franchise and league going, and suddenly you’re being asked about keeping your job. So I learned that early – you’ve got to keep your wins coming or the media will be all over you.

In 1971 we won our first championship, and it was the first championship for any team in Dallas. Then a baseball team came in to Dallas and you realised how cut-throat it was. We’d been getting good media coverage in the city newspapers, though there wasn’t much on TV. Then suddenly there’s a new baseball team coming to Dallas, and we were blown away, and I asked the journalists why we couldn’t get in the paper any more. They said, you were the only pro team in Dallas. And I’d be saying, but we draw more fans than the baseball team. And they’d say, that’s the way they do it, baseball won’t come to Dallas unless they’re guaranteed three stories in the sports pages every day. And one of those had to be on the front page of the sports section. Soccer didn’t have that power.

In 1971 we won our first championship, and it was the first championship for any team in Dallas. Then a baseball team came in to Dallas and you realised how cut-throat it was. We’d been getting good media coverage in the city newspapers, though there wasn’t much on TV. Then suddenly there’s a new baseball team coming to Dallas, and we were blown away, and I asked the journalists why we couldn’t get in the paper any more. They said, you were the only pro team in Dallas. And I’d be saying, but we draw more fans than the baseball team. And they’d say, that’s the way they do it, baseball won’t come to Dallas unless they’re guaranteed three stories in the sports pages every day. And one of those had to be on the front page of the sports section. Soccer didn’t have that power. In Dallas we played on artificial turf and the ball bounces differently and rolls off the field. We had a special shoe with smaller studs, they were just coming out. Before that the best way to play on artificial turf was a regular moulded stud, but reasonably worn down. When I was coach at the Fort Lauderdale Strikers [in 1977] we were playing up in New York at the Cosmos and we heard it was going to piss down with rain. So we looked into finding a different kind of shoe, one that would be sharper and give you a better grip. I talked to this manufacturer, Pony, who was distributing shoes to the Cosmos. We go up earlier in the day and somebody came along and gave us these shoes, they were the worst shoes you’ve ever seen, made of cardboard, you wouldn’t have sold them in Woolworths. If you tried to stop in them your foot would continue out of the shoe. They were horrible.

So we had to wear our normal worn-out shoes we wore for home games, where of course it was always dry because it never rained in Fort Lauderdale – we had a roof. And our goalkeeper Gordon Banks was slipping and sliding all over the place, he couldn’t stand up, and several players were like that. We got beat 8-3. There was this English player for the Cosmos on the left wing, he was cutting and twisting and spinning like a bloody ballerina, and I cornered him as we came off, and asked him, ‘How did you do that?’ ‘It’s these shoes,’ he said. I asked him for a look, and they were made out of kangaroo leather. I’ve always thought, though I couldn’t prove it, but the Cosmos could do or say whatever they liked. My suspicion was that whoever was in charge of footwear at the Cosmos told the company not to show us the shoes that the Cosmos had. We were cheated in that game. We had no chance to change the shoe just before kick-off. I think we were done by the shoes. Poor old Banksy in goal, he couldn’t cut from one side to the other. This is just my belief. There was no way we could possibly wear the shoe this company had presented to us. I always wish I’d kept a pair as proof. They were so powerful, New York.

At Fort Lauderdale you were in charge of a team that had Gordon Banks, Teofilo Cubillas, Gerd Müller, George Best - so in terms of star names you were competing with the Cosmos.

Newman

: That’s because I said to [owner] Joe Robbie, ‘We need players you can talk about.’ You can’t talk about players that came out of college, you had to go for big names. I had the smallest bloody budget in the whole league. I’d promise the players an extra ice cream after the game if they played for us. Müller was a wonderful player, but not all over the field. You had to tune your style of play to suit him, but he was a great character. Georgie came in… we were all sure we could save him from alcoholism, he hadn’t had a drink for six months. I don’t really want to go into this, because George is dead. Just for your own satisfaction, he wasn’t a great deal of help. He suddenly started drinking again. I go looking for him, it was a terrible shame, he still had a couple of years left, but not as a drunk. No one knows why it happened, he’d been six months without a drink, he was fine when he came from LA, but suddenly he disappears, his wife calls up. He came to training the next day and was in the car park stinking to high heaven of alcohol.

Newman

: That’s because I said to [owner] Joe Robbie, ‘We need players you can talk about.’ You can’t talk about players that came out of college, you had to go for big names. I had the smallest bloody budget in the whole league. I’d promise the players an extra ice cream after the game if they played for us. Müller was a wonderful player, but not all over the field. You had to tune your style of play to suit him, but he was a great character. Georgie came in… we were all sure we could save him from alcoholism, he hadn’t had a drink for six months. I don’t really want to go into this, because George is dead. Just for your own satisfaction, he wasn’t a great deal of help. He suddenly started drinking again. I go looking for him, it was a terrible shame, he still had a couple of years left, but not as a drunk. No one knows why it happened, he’d been six months without a drink, he was fine when he came from LA, but suddenly he disappears, his wife calls up. He came to training the next day and was in the car park stinking to high heaven of alcohol.There was a story before that, though, when he was sober. He’d scored a goal for us in his first or second game. Now you know how hot it gets in Fort Lauderdale, especially playing in the afternoon, and we used to have to play in the afternoon a lot because of television. So we’re playing and George was having a good game but he was slowing down pretty rapidly, and then started to kick back at young players who were taking the ball off him. He’d come from LA and had to sit out a number of games for a suspension for getting too many red and yellow cards. But if he’d got another red card he’d have had to sit out another long suspension. So he’s getting redder and redder in the face, so I thought Christ, if he gets sent off now we’re in the shit. So I take him off to do him a favour, and George comes off he starts pulling at his shirt, and I was already thinking he was going to throw it at me. He’s walking along the touchline and I know what he’s going to do. He throws it at my head, and I knocked it down nonchalantly and kept on giving instructions to the team. We won the game but on my way out the media was all over me. ‘What are you going to do about that?’ Me: 'About what?' ‘About Georgie Best - you took him off and he threw his shirt at you.’ Me: 'Everybody wants one of George’s shirts, I’m no different. George knows that I wanted one of his shirts.I’m going to take it home and frame it and put it over my fire place.' I made a joke about it. I saved George’s hide, because he was in big trouble.

In Atlanta you told the Journal in 68 that you didn’t agree with changing the laws of the game just to suit the US. Did you come to change that point of view?

Newman : I can’t believe I would have said that! Maybe they were talking about bigger goalposts or something like that. I was a big supporter of different rules for the US, like the 35-yard line. So was Pelé, so was Franz Beckenbauer. I went to the Rowdies game here in the new NASL and it was nil-nil, but there was no shootout, which was what that game needed. It [the shootout] was magical. I remember going back to England to watch Southampton against Tottenham and it was a bloody awful game. And at the end of the game it was 0-0 and a shootout would have saved the day.

A lot of these changes were made to the laws specifically to make the game more appealing in the US. Would they have worked for the rest of the world?

Newman : Without question. The 35-yard line was mainly down because we kept playing in high school arenas and they were so long and narrow. You were fitting a soccer field inside a running track and it was hard in this country because the running track was a different shape here, more narrow, and you’d get things like a long jump pit down the edge of the field and you had to cover it up. Now of course they have soccer-only stadiums. I hope that I had a major input in that, because I studied it and talked about it a lot. In Dallas I found out you couldn’t go to a High School field, where you’d get the atmosphere, because the media didn’t consider that was a place for professionals to play. So we had to play in that 70,000-seater stadium in Dallas where you couldn’t get the atmosphere.I went to Fort Lauderdale where there was only one stadium, and the press used to have to get up in the High School press box and opened up the windows because there was no a/c, and they’d be given food and the rain would come in the windows and ruin the sandwiches. But the fans really created an atmosphere in stadiums like that.

At Fort Lauderdale they had adult tickets at $5 each and kids’ tickets at $4.50. I said you can’t do that, you want kids to come and see the game. We had maybe five or six thousand seats on either side of the field. They said we can’t afford to let the tickets go for 50 cents. But we went that way and we got people, and next year we filled up the ends with seats, and then we sold out the corners, 16,000 fans, sold out and the atmosphere was tremendous.

How did your move to San Diego come about?

Newman

: We were trying to start a team in Miami in the American Soccer League, and they had me postpone the very first game because they couldn’t get into the stadium. I lost all the radio and media because of this bullshit. It was ridiculous, so I went over to San Diego, which wasn’t doing very well. It was a good club, Bob Bell was the owner, who I always thought was terrific. He drove a Rolls Royce, he’s still an old friend of mine. It was a load of different nationalities, I had no trouble getting on with them, and we managed to win. We had Kazimierz Deyna, he’d been playing at Manchester City at the time. He was a magician.He was tall enough, he wasn’t robust. They’ve got a shrine to him in Poland. It was summer-time [1989] when he died, I was in England, and he pulled over on a main road, and he was hit by a truck, killed instantly. They didn’t know who he was, but they found a ring on his finger which was a championship ring he’d won with the Sockers, and they knew who Iwas, so they called me and left a message on my machine that I didn’t get because I was in England. They wanted me to come down and identify the body. Man, I couldn’t have done that. We had one game in Chicago when he said he wasn’t feeling well, and I said to him he could raise his hand if he wanted to come off, whether it was ten seconds in or ten minutes in. Fortunately, he played and he went out there and had the game of his life [Chokes up].

Newman

: We were trying to start a team in Miami in the American Soccer League, and they had me postpone the very first game because they couldn’t get into the stadium. I lost all the radio and media because of this bullshit. It was ridiculous, so I went over to San Diego, which wasn’t doing very well. It was a good club, Bob Bell was the owner, who I always thought was terrific. He drove a Rolls Royce, he’s still an old friend of mine. It was a load of different nationalities, I had no trouble getting on with them, and we managed to win. We had Kazimierz Deyna, he’d been playing at Manchester City at the time. He was a magician.He was tall enough, he wasn’t robust. They’ve got a shrine to him in Poland. It was summer-time [1989] when he died, I was in England, and he pulled over on a main road, and he was hit by a truck, killed instantly. They didn’t know who he was, but they found a ring on his finger which was a championship ring he’d won with the Sockers, and they knew who Iwas, so they called me and left a message on my machine that I didn’t get because I was in England. They wanted me to come down and identify the body. Man, I couldn’t have done that. We had one game in Chicago when he said he wasn’t feeling well, and I said to him he could raise his hand if he wanted to come off, whether it was ten seconds in or ten minutes in. Fortunately, he played and he went out there and had the game of his life [Chokes up].You had great success with San Diego…

Newman : In 84 we switched to the indoor league, and Kaz was behind switching the rest of the players to the indoor game. Within a game or two, he was just as good indoors as he was outdoors.

Dave Chadwick said he found indoor soccer boring to play. Do you think indoor soccer helped the league’s demise?

Newman : It was all promotion, it was easy to sell, the fans loved it, they were close to the players, they could watch three games a week. When I was at Dallas I was invited to an indoor game at St. Louis and I didn’t know what to expect. It was a Hocksoc tournament, they didn’t have the in-built goal yet, this was around 1970. I thought this was great, it’s fun, you’re not cold, not too hot, the rain wouldn’t stop it. I kept trying to tell the league it was brilliant, easy to sell, that it could go worldwide. In winter we’d go and play an indoor tournament, then in 1978 the other indoor league started. All the good players were good indoor players too. I loved the game and had a lot to do with the rules and how it was played. When the NASL folded [in 1984] I was sitting there in the San Diego office. I was elated at being coach of the year, but I was shocked that the league had folded.

Was it really a shock at that point that the NASL folded?

Newman : There was something going on in Rochester, some goalkeeper came out and didn’t know whether to go for indoor or outdoor, and suddenly that team decided it would play indoor, and that was the straw that broke the camel’s back. You had to have eight teams [for outdoor NASL], and if we didn’t have eight it wasn’t going to happen. We should have gone and got another team, we switched to seven and didn’t have enough time to find the eighth one, we should have been doing something behind the scenes. It was a great league and when it went down I was sitting there in my office crying my eyes out.

We never worked together, people were jealous of each other, fighting each other, we should have been able to have an indoor league and an outdoor league. What terrible mistakes people make.

If the NASL had survived, so you think soccer in the US today would be significantly more advanced?

Newman : Absolutely, we would be all like Seattle and Portland are now

What was it like going to coach in Major League Soccer for the Wizards in 1996?

Newman : I was the first coach recruited. Lamar Hunt was the one who hired me. When Lamar let me go in Dallas in 1975, it was time, and there were lots of reasons for it, but I was ready to go. Lamar was there with Bill McNutt, two great gentlemen. They called me in to let me know, but I already knew. They said they were going to try and recruit the top coach in the world. I said, ‘That’s a shame, you can’t do that now.’ He [Lamar] said, ‘What do you mean?’ I said, ‘You just fired him.’ Many years later I’d just won the title in San Diego and Lamar wrote me a card saying. ‘Why didn’t you tell me you were the best coach in the world?’

When you went back to coach the Wizards, that was Lamar’s team too?

Newman

: Yes, I was really ready to retire. The first two years we had one of the best regular season records and people had said I couldn’t do anything besides indoor soccer. Anyway, it was very, very difficult in Kansas. Lamar was quite ill, so I had nowhere to go if I had problems. There was no training pitch, and you were always in a fight with the NFL people because we were sharing facilities. You had all these people wanting to try out for the team. There was little chance of finding a new player like that. So we turned it into a promotion. But then we couldn’t get the field to play on. I said, ‘We can’t play on a field where someone’s granny is taking their dog for a walk.’ So how do you solve that problem? You turn to Lamar and the problem’s solved in a flash. But that was hard, getting the money to find a training ground. We did draw 20,000 for the first game, but then we didn’t play at home again for two weeks and all the hoopla was lost.

Newman

: Yes, I was really ready to retire. The first two years we had one of the best regular season records and people had said I couldn’t do anything besides indoor soccer. Anyway, it was very, very difficult in Kansas. Lamar was quite ill, so I had nowhere to go if I had problems. There was no training pitch, and you were always in a fight with the NFL people because we were sharing facilities. You had all these people wanting to try out for the team. There was little chance of finding a new player like that. So we turned it into a promotion. But then we couldn’t get the field to play on. I said, ‘We can’t play on a field where someone’s granny is taking their dog for a walk.’ So how do you solve that problem? You turn to Lamar and the problem’s solved in a flash. But that was hard, getting the money to find a training ground. We did draw 20,000 for the first game, but then we didn’t play at home again for two weeks and all the hoopla was lost.After two years Lamar offered me a second contract and I wasn’t sure, and I was thinking about going back to a team in Florida, that it might be easier to bring the crowds to. I went to Lamar and asked if I could enter into talks with Fort Lauderdale, thinking purely of the game, and he sent me back a great big NO on the letter and gave me 25 grand more. I wasn’t interested in the money, it was just that it was so difficult in Kansas to compete with baseball and Football. Of course I didn’t turn it down, but it wasn’t the reason for doing it.

Here’s another NASL story. I was coach at Dallas and we went down to Washington and they had the pitcher’s mound still on the playing field. I hated those baseball fields. You were supposed to remove it before soccer games, but they said they couldn’t do it, that there was no way to move it. I remember this one Brazilian centre-back we had would be there waiting for the attackers to come down the pitcher’s mound.So after the game I wrote to the league and complained and said I’d refuse to play there again as long as the baseball mound was there. So we go back out there for another game – no pitcher’s mound because they’d pushed the pitch across and just manage to get the mound off the field. After 15 minutes we get our first corner, and the corner flag is two or three inches away from the fence. Our player’s looking at it and wondering how he’s going to run up. Then he sees on the fence there’s a handle, so he opens it, walks up the path for his run-up, but as he turns to take the corner the door shuts and he can’t get out. So he can’t get on to take the corner kick. I always finish the story by saying, ‘He wasn’t playing that well so we left him in there’ [Laughs].

Ron Newman (19.1.36-27.08.18), North American Soccer League Coach of the Year: 1971, 1977, 1984.

Published on August 29, 2018 04:04

February 19, 2018

Good Seats Still Available - RnRS on the Podcast For Extinct Leagues

Good Seats Still Available is a podcast created by Tim Hanlon focusing on the history of defunct US sports leagues. In the latest episode, he interviews me about the North American Soccer League.

I talk about why I'm fascinated by the NASL, what motivated me to write Rock n Roll Soccer , and some of the people, rules and stories that made it a lost but pioneering league.

Kicks from Minnesota, Roughnecks from Tulsa. What more do you need?

Kicks from Minnesota, Roughnecks from Tulsa. What more do you need?

I talk about why I'm fascinated by the NASL, what motivated me to write Rock n Roll Soccer , and some of the people, rules and stories that made it a lost but pioneering league.

Kicks from Minnesota, Roughnecks from Tulsa. What more do you need?

Kicks from Minnesota, Roughnecks from Tulsa. What more do you need?

Published on February 19, 2018 05:46

August 29, 2016

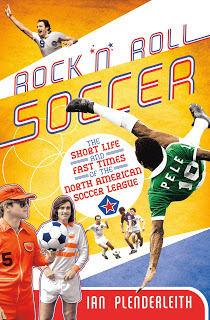

Rock n Roll Soccer - more rollicking reviews

Some recent customer reviews from the ever-reliable internet. At amazon.com,

Rock n Roll Soccer has a 100% 5-star rating (nine reviews):

"Definitive history with a cogent narrative. Thorough without being tedious and ties the story to the present. If you didn't grow up with soccer [in the US] you need this book to fill in that gap." (Nathan Sager, amazon.com reader) "Football book of

"Football book of

the decade."

"With this book, [the author] has managed to weave together a huge amount of research and interviews into a cohesive and rollicking narrative. This means that it doesn't really matter if you weren't previously interested in the NASL - if you like sports journalism, particularly the longer form more common in the USA over the years, then chances are you will very much enjoy this. As well as Plenderleith does in weaving this book together, perhaps the best writing in it is his own voice - when he's assessing things in a very dry way, that often raises a chuckle. Having enjoyed his fiction, I hope now also for more non-fiction from him." (reader review, amazon.co.uk)

"The football book of the decade." (Richard Luck on Twitter)

"This is a splendid book. Although it explicitly claims not to be a history of the NASL, and it's right, it isn't, it is very, very informative. It seems that Mr Plenderleith the author has also written the book with a wry smile on his face because football is only a game after all. There is plenty of humour and the half time entertainment is a lot of fun. The most fascinating thought the book leaves you with is that despite folding in 1984 the NASL can be seen to have left a legacy which is very visible in the English Premier League." (reader review, amazon.co.uk)

"Definitive history with

"Definitive history with

a cogent narrative""A must read for any fan of the NASL! So many players names brought up in this GREAT book that bring back memories. I was lucky enough to go to Spartan Stadium and watch my beloved Earthquakes play and watch that GREAT George Best goal. We can not and must not forget these pioneers that started it." (reader review, amazon.com)

"So, I’m giving this book five stars (and would give it a hundred if I could) just because it’s the first time I’ve seen an outsider actually give us some recognition." (John F. Pepple, amazon.com reader)

"A great book about a wild and crazy league that probably could've only existed in the mid to late 70s-early 80s. Fast and loose and freewheeling, the book reads a lot like the NASL's existence, bouncing from pillar to post, sometimes quite unorganized, and a little frustrating. Still a good read. Recommended." (reader review, amazon.com)

Rock n Roll Soccer has a 100% 5-star rating (nine reviews):

"Definitive history with a cogent narrative. Thorough without being tedious and ties the story to the present. If you didn't grow up with soccer [in the US] you need this book to fill in that gap." (Nathan Sager, amazon.com reader)

"Football book of

"Football book of the decade."

"With this book, [the author] has managed to weave together a huge amount of research and interviews into a cohesive and rollicking narrative. This means that it doesn't really matter if you weren't previously interested in the NASL - if you like sports journalism, particularly the longer form more common in the USA over the years, then chances are you will very much enjoy this. As well as Plenderleith does in weaving this book together, perhaps the best writing in it is his own voice - when he's assessing things in a very dry way, that often raises a chuckle. Having enjoyed his fiction, I hope now also for more non-fiction from him." (reader review, amazon.co.uk)

"The football book of the decade." (Richard Luck on Twitter)

"This is a splendid book. Although it explicitly claims not to be a history of the NASL, and it's right, it isn't, it is very, very informative. It seems that Mr Plenderleith the author has also written the book with a wry smile on his face because football is only a game after all. There is plenty of humour and the half time entertainment is a lot of fun. The most fascinating thought the book leaves you with is that despite folding in 1984 the NASL can be seen to have left a legacy which is very visible in the English Premier League." (reader review, amazon.co.uk)

"Definitive history with

"Definitive history witha cogent narrative""A must read for any fan of the NASL! So many players names brought up in this GREAT book that bring back memories. I was lucky enough to go to Spartan Stadium and watch my beloved Earthquakes play and watch that GREAT George Best goal. We can not and must not forget these pioneers that started it." (reader review, amazon.com)

"So, I’m giving this book five stars (and would give it a hundred if I could) just because it’s the first time I’ve seen an outsider actually give us some recognition." (John F. Pepple, amazon.com reader)

"A great book about a wild and crazy league that probably could've only existed in the mid to late 70s-early 80s. Fast and loose and freewheeling, the book reads a lot like the NASL's existence, bouncing from pillar to post, sometimes quite unorganized, and a little frustrating. Still a good read. Recommended." (reader review, amazon.com)

Published on August 29, 2016 00:53

May 5, 2016

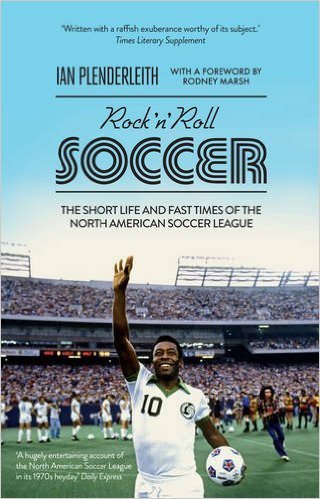

Pelé salutes the readers of Rock n Roll Soccer!

Edison Arantes do Nascimento holds up his hand for

Edison Arantes do Nascimento holds up his hand for a cheap(er) copy of Rock n Roll Soccer. The trade paperback version of Rock n Roll Soccer is published today in the UK. Don't ask me what "trade paperback" means. The first edition was just a plain old paperback for £14.99, the trade paperback is a wee bit smaller and costs six pounds less at £8.99. But calling it the "cheap paperback" probably wouldn't do much for sales. Everyone likes a bargain, but no one wants to be told they're buying low grade goods.

Pelé, as you can see, is on the cover this time. For the plain old expensive paperback we went with Rodney Marsh and George Best and The Bloke Between Them, who turned out to be their agent, but was managing to look like a member of The Eagles - so the photo fit the title. While writing the book, I caught up with the agent by phone from California, where he's now in property. He couldn't remember much about the North American Soccer League, but vehemently denied the allegations in former Washington Diplomats' striker Paul Cannell's book that following a sponsorship deal, he once paid the Geordie striker in lieu of cash with a fat pouch of cocaine.

Three-times world champion Edison Arantes do Nascimento, though, sells more books than some dodgy no-name former wide-boy, so the agent's been despatched to the archives and the cover shows what I'm claiming in the book the NASL was not all about - Pelé, the Cosmos, razzmatazz blah blah blah. But I realise that's not what grabs a reader's attention. Every time I hand someone a copy of the book, or see them pick it up, the first thing they do is flick to the pictures in the centre. Every single person. Pictures, fellow hacks - if you're writing a non-fiction book, don't forget the pictures. Preferably of easily recognisable people.

Pelé is delighted to be on the front cover - you can tell from his face. You may quibble that he didn't know when he was running out on to the field that he was going to be on the front cover of Rock n Roll Soccer some four decades later. But you can't prove that he didn't. And that he's waving, "Buy! Buy!" It's what the game's been all about since the day he signed for the Cosmos.

Published on May 05, 2016 07:40

May 3, 2016

Johan Cruyff in the NASL: the Anti-Diplomat

When Prince died last month, someone on my Twitter feed posted a snapshot of the page in a book they'd written that told an anecdote involving the singer. Less than a day had passed since the announcement, and already a writer was crying out, "Prince is dead, buy my book!" Well, as I'm always told, publishing's a business just like any other.

Cutting through the bullshit: Cruyff in DC It's taken me a few weeks to write about Johan Cruyff. The day after his death, one of my publishers contacted me to write a piece about the Dutchman and his time in the North American Soccer League. They would try and place it with a newspaper. Good publicity for the book, you understand. It wasn't a good time, and in any case, I didn't want to. There were dozens of Cruyff appreciations being hacked out, as you'd expect. Nothing I said was going to add to the narrative, and I'd have been left with the same sensation I had when I saw the Prince tweet - Cruyff is dead, read all about it! I do read obituaries and I've also been paid to write them, so I'm not trying to come across as morally aloft. But there's a difference between using words to deal with your upset and manufacturing them to push your bloody book (again).

Cutting through the bullshit: Cruyff in DC It's taken me a few weeks to write about Johan Cruyff. The day after his death, one of my publishers contacted me to write a piece about the Dutchman and his time in the North American Soccer League. They would try and place it with a newspaper. Good publicity for the book, you understand. It wasn't a good time, and in any case, I didn't want to. There were dozens of Cruyff appreciations being hacked out, as you'd expect. Nothing I said was going to add to the narrative, and I'd have been left with the same sensation I had when I saw the Prince tweet - Cruyff is dead, read all about it! I do read obituaries and I've also been paid to write them, so I'm not trying to come across as morally aloft. But there's a difference between using words to deal with your upset and manufacturing them to push your bloody book (again).

During these past few weeks, though, I did think about Cruyff a lot, just as I had done while writing 'Rock n Roll Soccer'. During that time, I thought how magnificent it would be to talk to him about the NASL. Doubtless, my publisher would have been happy too. But I really did want to know what he'd thought of the league, of the USA, why he went there, and what was his view of soccer there now. I wanted to know what he thought way more than I wanted to know what Pelé or Franz Beckenbauer thought. Cruyff, I imagined, would have torn it up and prompted me to start all over again. He would have said the unexpected, the slanted, the unpopular, the bizarre, the interesting. Not may soccer players manage that.

In many interviews I conducted for the book, I maybe suggested certain things in my questions. Thus prompted, the interviewee might agree, or they said, "You know, I'd never thought of it like that, but I think you're right." How great for the writer's ego! What I loved to hear, however, was the moment when they said, "No, it wasn't like that at all. That's bullshit. This is what it was like." I thought that Cruyff would do that with every question. He would make me feel small and stupid. Like the player and the person he was, he would come at every topic from a completely fresh angle, varying his replies from the ludicrous to the enlightening. It's a certainty that he would have made me write a better book.

Leading from the front: "He was

Leading from the front: "He was

the ultimate team player."The players who encountered him in the NASL loved to talk about him. Who wouldn't want to remind people that they played alongside him? Or against him, like Rochester's Damir Šutevski, who admits in a game where Cruyff scored twice for LA (even though he only played one half, in his first game for six months), "I covered him but I couldn't stop him. He took me to the cleaners." Carmine Marcantonio of the Washington Diplomats recalls trying to compete with Cruyff and LA in a playoff game in 1979, and takes up the tale of chasing the player when he received the ball at the top of his own penalty area. "He got the ball, I caught up with him, I tried to grab his shirt, but I couldn't bring him down and I went down and dislocated my finger trying to hold him back. He went upfield with the ball, faked out two or three defenders and scored the winning goal. There's a picture with four of us on the ground and Johan putting the ball in the empty net."

Cruyff was promptly signed by the Diplomats for the 1980 season, "and that was one of the best years I had, being teammates with Johan", says Marcantonio. "He was the ultimate team player. He took more pleasure in assisting and would pass to a team-mate to score." Cruyff scored 10 goals, but also registered 20 assists in 25 regular season games. However, Bob Iarusciand Don Droege - also both on the Diplomats' team that year - agree that Cruyff disturbed the equilibrium of what had been a fairly successful side, and that he more or less usurped team coach Gordon Bradley when it came to tactics. Droege personally wasn't bothered: "I'm just a lowly American player, and I'm just happy to be out on the field. But the English players like Alan Green, Bobby Stokes, Jim Steele, Matt Dillon - you bring in a player like Cruyff and the whole dynamics are gone." Droege didn't recall any truth to the rumoured story of Cruyff wiping Bradley's chalkboard clean so that he could give his own team-talk, but adds, "I do remember talking with Bradley in the bathroom and him checking under the stalls to make sure Cruyff wasn't in there listening to us."

Cruyff claimed at the time he was in the NASL to help promote and develop the game in the US, but it was also thought that, like Pelé, he came out of retirement because he needed cash after making some poor investments. It's no longer relevant. It's only important that he graced the league with his superior enigmatic touch for a handful of years. "He was a great individual," says Marcantonio, "in that he almost wanted to run the show on the field, but wanted it done in a team concept. Johan was very domineering. Like any great player, he didn't shut up." And for that we can only be thankful.

(The story of NASL soccer in Washington DC, and Cruyff's role in turning around the Diplomats' 1980 season, can be read in Chapter 8 of Rock n Roll Soccer , 'Broken Teams in Dysfunctional DC: Cruyff, the Dips, the Darts and the Whips.' Buy it now for just $£ etc. etc.)

Cutting through the bullshit: Cruyff in DC It's taken me a few weeks to write about Johan Cruyff. The day after his death, one of my publishers contacted me to write a piece about the Dutchman and his time in the North American Soccer League. They would try and place it with a newspaper. Good publicity for the book, you understand. It wasn't a good time, and in any case, I didn't want to. There were dozens of Cruyff appreciations being hacked out, as you'd expect. Nothing I said was going to add to the narrative, and I'd have been left with the same sensation I had when I saw the Prince tweet - Cruyff is dead, read all about it! I do read obituaries and I've also been paid to write them, so I'm not trying to come across as morally aloft. But there's a difference between using words to deal with your upset and manufacturing them to push your bloody book (again).

Cutting through the bullshit: Cruyff in DC It's taken me a few weeks to write about Johan Cruyff. The day after his death, one of my publishers contacted me to write a piece about the Dutchman and his time in the North American Soccer League. They would try and place it with a newspaper. Good publicity for the book, you understand. It wasn't a good time, and in any case, I didn't want to. There were dozens of Cruyff appreciations being hacked out, as you'd expect. Nothing I said was going to add to the narrative, and I'd have been left with the same sensation I had when I saw the Prince tweet - Cruyff is dead, read all about it! I do read obituaries and I've also been paid to write them, so I'm not trying to come across as morally aloft. But there's a difference between using words to deal with your upset and manufacturing them to push your bloody book (again).During these past few weeks, though, I did think about Cruyff a lot, just as I had done while writing 'Rock n Roll Soccer'. During that time, I thought how magnificent it would be to talk to him about the NASL. Doubtless, my publisher would have been happy too. But I really did want to know what he'd thought of the league, of the USA, why he went there, and what was his view of soccer there now. I wanted to know what he thought way more than I wanted to know what Pelé or Franz Beckenbauer thought. Cruyff, I imagined, would have torn it up and prompted me to start all over again. He would have said the unexpected, the slanted, the unpopular, the bizarre, the interesting. Not may soccer players manage that.

In many interviews I conducted for the book, I maybe suggested certain things in my questions. Thus prompted, the interviewee might agree, or they said, "You know, I'd never thought of it like that, but I think you're right." How great for the writer's ego! What I loved to hear, however, was the moment when they said, "No, it wasn't like that at all. That's bullshit. This is what it was like." I thought that Cruyff would do that with every question. He would make me feel small and stupid. Like the player and the person he was, he would come at every topic from a completely fresh angle, varying his replies from the ludicrous to the enlightening. It's a certainty that he would have made me write a better book.

Leading from the front: "He was

Leading from the front: "He wasthe ultimate team player."The players who encountered him in the NASL loved to talk about him. Who wouldn't want to remind people that they played alongside him? Or against him, like Rochester's Damir Šutevski, who admits in a game where Cruyff scored twice for LA (even though he only played one half, in his first game for six months), "I covered him but I couldn't stop him. He took me to the cleaners." Carmine Marcantonio of the Washington Diplomats recalls trying to compete with Cruyff and LA in a playoff game in 1979, and takes up the tale of chasing the player when he received the ball at the top of his own penalty area. "He got the ball, I caught up with him, I tried to grab his shirt, but I couldn't bring him down and I went down and dislocated my finger trying to hold him back. He went upfield with the ball, faked out two or three defenders and scored the winning goal. There's a picture with four of us on the ground and Johan putting the ball in the empty net."

Cruyff was promptly signed by the Diplomats for the 1980 season, "and that was one of the best years I had, being teammates with Johan", says Marcantonio. "He was the ultimate team player. He took more pleasure in assisting and would pass to a team-mate to score." Cruyff scored 10 goals, but also registered 20 assists in 25 regular season games. However, Bob Iarusciand Don Droege - also both on the Diplomats' team that year - agree that Cruyff disturbed the equilibrium of what had been a fairly successful side, and that he more or less usurped team coach Gordon Bradley when it came to tactics. Droege personally wasn't bothered: "I'm just a lowly American player, and I'm just happy to be out on the field. But the English players like Alan Green, Bobby Stokes, Jim Steele, Matt Dillon - you bring in a player like Cruyff and the whole dynamics are gone." Droege didn't recall any truth to the rumoured story of Cruyff wiping Bradley's chalkboard clean so that he could give his own team-talk, but adds, "I do remember talking with Bradley in the bathroom and him checking under the stalls to make sure Cruyff wasn't in there listening to us."

Cruyff claimed at the time he was in the NASL to help promote and develop the game in the US, but it was also thought that, like Pelé, he came out of retirement because he needed cash after making some poor investments. It's no longer relevant. It's only important that he graced the league with his superior enigmatic touch for a handful of years. "He was a great individual," says Marcantonio, "in that he almost wanted to run the show on the field, but wanted it done in a team concept. Johan was very domineering. Like any great player, he didn't shut up." And for that we can only be thankful.

(The story of NASL soccer in Washington DC, and Cruyff's role in turning around the Diplomats' 1980 season, can be read in Chapter 8 of Rock n Roll Soccer , 'Broken Teams in Dysfunctional DC: Cruyff, the Dips, the Darts and the Whips.' Buy it now for just $£ etc. etc.)

Published on May 03, 2016 01:48

December 8, 2015

Major League Soccer’s Existential Dilemma

Personality x 3: Chinaglia, Pelé, BeckenbauerWendy Parker's review of Rock n Roll Soccer at Sports Biblio last week highlighted the book's conclusion, where I write about the lack of personality in Major League Soccer compared with its fore-runner, the North American Soccer League. That's an aspect of the book that's been further thrown into focus this week as MLS concluded another season with yet another new champion, the Portland Timbers. All for the good, of course. Who doesn't like to see titles shared around? Who wants to be like Europe, where Barcelona or Bayern Munich win year after year?

Personality x 3: Chinaglia, Pelé, BeckenbauerWendy Parker's review of Rock n Roll Soccer at Sports Biblio last week highlighted the book's conclusion, where I write about the lack of personality in Major League Soccer compared with its fore-runner, the North American Soccer League. That's an aspect of the book that's been further thrown into focus this week as MLS concluded another season with yet another new champion, the Portland Timbers. All for the good, of course. Who doesn't like to see titles shared around? Who wants to be like Europe, where Barcelona or Bayern Munich win year after year?On the other hand, there's a major existential problem here for MLS. Commissioner Don Garber is never slow to talk about where his league stands in comparison with its European counterparts. He likes to set vague future goals about when MLS will be big, bigger and biggest. Last week he was talking up the rotating championship title as a reflection of "one of the most competitive leagues in the world". Yet when we think about MLS, what are the equivalent keywords to the NASL's feverishly listed Cosmos, Pelé, Beckenbauer, Best, Cruyff, Chinaglia? You can't answer back with 'parity' and expect to hold anyone's interest.

But didn't MLS sign David Beckham? Wasn't that the league's Pelé moment? Beckham may be a polite and wealthy young man, but his on-field and off-field personality fell way short of making an impact the size of Pelé's. His former team, the LA Galaxy, may be five-times record champion, but they don't yet have the stature or the style - in any respect - to be seen as the North American domestic giants. They just happen to be the team that has won MLS Cup more than anyone else, without offering many thrills on the way. They also boasted the league's and the United States' best ever player, Landon Donovan, but he needed to be one of many. Instead, he was just one of one. Now he's retired, leaving Toronto's Italian striker Sebastian Giovinco as the league's sole outstanding player in 2015.

In late October, I managed to get a ticket for Eintracht Frankfurt's home game with Bayern Munich. It's the only guaranteed sold out home game for Eintracht, and it's been that way for decades. Every right-thinking German soccer fan hates Bayern, and wants to see them defeated. Though in fact you could leave the word 'defeated' out of the previous sentence. Even as we despise them, we are fascinated at the way they can tear opponents apart with audacious attacking soccer. On the night, Frankfurt defended their asses off and grabbed a point in a 0-0 draw - the first points that Bayern had dropped all season. It's been a point of some pride in a mainly dire season for Frankfurt.

Bayern Munich - hated, but talked about. Rich, hugely successful, and inversely popular. They are a globally massive team. Am I really saying that MLS needs a team like Bayern to win MLS Cup year after year? Not at all. MLS could, however, urgently use four or five teams with some measure of Munich's magnetism. At the moment, parity means 20 clubs that vary from anaemic to presentable. There are still too many MLS games when the teams seem to think that the idea of soccer is to keep the ball as far away from both goals as possible. Importing veteran star names like Andrea Pirlo, Kaka, Steven Gerrard and Frank Lampard is a sign of stagnant imaginations in the league's front offices. These players won't make the league any worse, but neither they will they do much for its future. Eventually expanding the number of teams to 28, as MLS announced just this week, is making me feel tired as I type, and it's only nine in the morning.

Fatal expansion: Former NASL commissioner

Fatal expansion: Former NASL commissionerPhil Woosnam presents quantity over quality.

Garber pointed out last week that "we’re spending almost $120 million on DPs [Designated Players]. That’s six times what we spent five years ago. So if we’re able to grow our business, our owners are going to spend more money. And it’s not just going to be on our core roster. It’s going to be on areas where we can spend more on players that will improve quality." To paraphrase the commissioner - spending money on big name players means the league will attract even more money, and then we can invest that in long term youth development. That's a leap of faith that's hard to quantify, even with the aid of corporate flow charts. As a Plan for the Future, it's lacking exactly what you would hope for in a plan for the future - a clear-sighted vision, and a cogent means of getting there.

In the book's conclusion I generally show understanding for the MLS approach to building a league during those nascent years. Its caution, its prudence, and its need to develop in a way that will not frighten off new investors with concepts like relegation and bankruptcy. Yet, as that $120m figure above shows, parity and the salary cap have become fluid concepts according to the league's evolving needs.

That salary cap isn't fooling anybody, and is increasingly meaningless when the league, with a ludicrous and shameless lack of transparency, will not even reveal its teams' profits and losses, transfer figures, or salaries (we have to rely on leaks, Forbes and the players' union for any of this information). What remains of parity's sham are the shackles preventing the emergence of teams with the kind of power and personality that - compared with the old NASL - is conspicuously missing. Still in place is a league more focused on its balance sheet than its league table and the quality of its play.

A possible solution? MLS should stop trying so hard to control its own history. Quit setting grandiose goals, drop the business-speak, and cease caring about how it shapes up compared with Spain, England and Germany. Retire Garber - he's steered the league to security, but his job is done. Bring in someone (former deputy Ivan Gazidis?) who has a genuine feel for the game. Remove parity and let the clubs chart the league's history, mistakes and all. Allow supporters to develop a team's culture, not the marketing department.

It wouldn't mean having to see the same team celebrate lifting the championship trophy year after year. The playoffs will prevent the dominant teams from serially winning titles and always give outsiders a chance. Even the mighty Cosmos only won four of the ten NASL titles between 1975 and 1984. They had charisma, but it was infectious. And as that league discovered too late - better a smaller, vibrant league than ill-conceived expansion for expansion's sake.

Published on December 08, 2015 04:40

October 30, 2015

"Thank Goodness for Rock n Roll Soccer"

America's longest-running football/soccer publication, Soccer America, has reviewed 'Rock n Roll Soccer'. Here's Mike Woitalla's full appraisal:

America's longest-running football/soccer publication, Soccer America, has reviewed 'Rock n Roll Soccer'. Here's Mike Woitalla's full appraisal:One of my favorite soccer memories: I was 13, sitting next to my grandfather who was visiting us from Germany, in Aloha Stadium watching Team Hawaii play the Las Vegas Quicksilvers.

I noticed that Opa, not a man prone to demonstrating excitement, was practically giddy.

“Michael, that’s Eusebio!” he said. “The world’s best player ever besides Pele. … See No. 5? That’s Wolfgang Suhnholz. He played for Bayern Munich!”

This was in 1977. After the North American Soccer League had so much success in many parts of the country, it started franchises in the middle of the Pacific and in the middle of desert -- when Vegas was a third the size it is now, had never had major league sports, and no soccer culture.

“What the hell were they thinking?” writes Ian Plenderleith in 'Rock 'n' Roll Soccer: The Short Life and Fast Times of the North American Soccer League.' After one season, The Quicksilvers moved to San Diego and Team Hawaii became the Tulsa Roughnecks."

Reckless expansion was of course a main factor for the demise of the NASL, which folded after the 1984 season.

But, boy, am I thankful that the NASL did some crazy stuff. Not just because of the memory of seeing my grandfather so delighted, or because I got to watch Pele play, or had Team Hawaii players visit my school.

The NASL inspired the generation of players who made the U.S. national team respectable, like New Jersey boys Tony Meola, John Harkes, Tab Ramos and Claudio Reyna, who went to New York Cosmos games. It spread the seeds that led to soccer’s current state -- neck and neck with basketball as the most popular team sport among American children.

“In 1967, 12,000 schoolchildren went through the [Atlanta] Chiefs soccer clinics, while 42 area high schools had begun to play the game,” writes Plenderleith.

But what Plenderleith does most expertly -- and is previously less covered than NASL grassroots’ impact -- is show the NASL’s impact on the global game, and how some of that stuff doesn’t seem so crazy in hindsight.

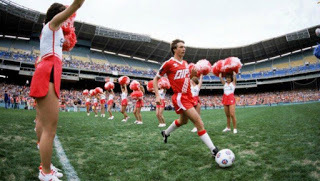

“Old World” soccer purists may have mocked halftime armadillo races, players entering the field on Harley-Davidsons, or the San Diego Chicken doing a pirouette, flopping and playing dead next to a fouled player. (Minnesota Kicks coach Geoff Barnett: “The referee goes nuts and comes over to me shouting, ‘Get that f****** chicken off the field!”)

But as Plenderleith writes, the NASL was “a league that got too much right to ignore.”

“The NASL introduced the idea that a soccer game could be an event and a spectacle, not just two teams meeting to compete for points. You weren’t herded into the stadium by policemen waving wooden batons. You were a customer …”

Some of the “manufactured atmosphere” -- which could also be considered “marketing techniques aimed at wooing a new generation of fans” -- may have been over the top. But …

“Once the game started you could watch a version of soccer easily recognizable as the real thing, but which promoted scoring, played down defensive duties, and refuted the virtues of a hard-fought 1-1 draw. …

“In the 1970s, Pele, Johan Cruyff, Eusebio, George Best, Gerd Mueller and Franz Beckenbauer all played in the same league. … It was a big money glamour league that aimed to entertain, while generating cash. In that respect, it was the Champions League and the English Premier League rolled into one.”

Plenderleith lays out a solid case for how the NASL was ahead of its time. FIFA may have fought the league’s attempts to tweak the rules, but later made changes that resemble some of those attempts. Publishing a wide range of game statistics, marketing to women, names on the back of jerseys -- that happened first in the NASL.

Clive Toye, the former New York Cosmos general manager, says, “We were constantly being visited by executives from English clubs to see what we were doing, asking why we were doing it.”

From all that the NASL got right to where it went astray, this colorful and important era of American soccer is in good hands with Plenderleith, a skillful writer and thorough journalist.

For those of us who lived through the NASL, 'Rock 'n' Roll Soccer' brings back wonderful memories and enlightens us on aspects of the league we may not have realized. For those too young to remember the NASL, it’s a chance to comprehend how soccer took a foothold in the USA and meet the fascinating characters who made it happen -- with laugh-out-loud moments, to boot.

Rock 'n' Roll Soccer: The Short Life and Fast Times of the North American Soccer League by Ian Plenderleith (Thomas Dunne Books 2015) 350 pages.

Published on October 30, 2015 01:19

October 1, 2015

Interview with the late John Best: Spartans, Stokers, Sounders and Roses

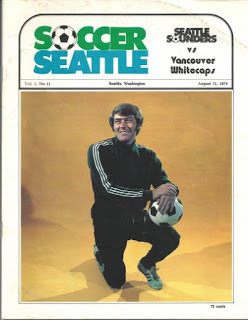

John Best was a player, a coach and a General Manager in the North American Soccer League. After coming over from his native England in the early 1960s, he turned out for the Philadelphia Ukrainians in the American Soccer League (1962-67), the Philadelphia Spartans (1967), the Cleveland Stokers (1968), and the Dallas Tornado (1969-73). He then coached the Seattle Sounders for three years before becoming GM at the Vancouver Whitecaps. He then returned to the Sounders, also as GM.

John Best, transitioning from

John Best, transitioning from

player to coach in 1974 John very sadly passed away a year ago. With the permission of his wife, Claudia, here are the highlights of an interview that John gave me in January 2014 while I was researching Rock n Roll Soccer .

RnRS: You started out with the Philadelphia Spartans in the National Professional Soccer League [which one year later merged with the United Soccer Association to become the NASL]. Can you tell me about the pay and conditions as a player in 1967? Were you well looked after? John Best: Oh yes, very much so. The pay wasn’t great at that point in time, but it was as good as a lot of people were getting in the first and second divisions in England. I’m sure there were many [in the NPSL] who earned less, but in terms of being taken care of - it was really unbelievable because of the quality of hotels and travel. We flew to games, stayed in the best hotels, and I remember after we played in St. Louis, [team owner] Art Rooney took the whole team out to eat. I don’t know that every team was treated that way, but certainly we were. And at the clubs I later managed we tried to maintain the high standards as well. It was a better experience than most people had in British soccer.

RnRS: Art Rooney was typical of the early NASL owner - a wealthy entrepreneur. Looking back, is it surprising to you that people like him wanted to get involved in soccer?JB: Rooney owned the Pittsburgh Steelers. If you go back and look at the ownership of the NASL clubs all the way through that early period, you’ll find that it was extremely strong, and made up mainly of sports entrepreneurs. They were wealthy people, but very shrewd in terms of marketing professional sports. The problem was that the sport was unknown – you’re not just starting up a new sport, but you’re starting up with people with absolutely no concept or idea of that. It took a tremendous effort to grow the sport in those early years. I was very fortunate to play for the Rooneys. Later on I played in Dallas for Lamar Hunt, and then went up to Seattle as coach for an expansion team, where the ownership group were city elders, and [were] just very intelligent, proactive people. So you had a great opportunity to do a quality job, because you were left alone to do it, and with enough funding. I’m not suggesting that all ownerships were like that. There were amazing changes as time went by, and the majority of teams became corporately owned, and that brings a difference in attitude and perspective – when you have a meeting of CEOs of major corporations compared with a group of wealthy sports entrepreneurs.

Philly, replaced by fillies after one yearRnRS: The Spartans folded after one year. Was that down to money?

Philly, replaced by fillies after one yearRnRS: The Spartans folded after one year. Was that down to money?

JB: That was part of the reason, but they also had the licence for horse racing in Philadelphia – that was certainly profitable. They were offered the licence for through-bred racing, so they took that instead of soccer, and I think they used the same facility for the horse-racing.

RnRS: Then in 1968 you went to Cleveland, but they only lasted one year as well.JB: It turned out that 80-90% of the Spartans were going to Cleveland, so I wanted to be part of that. They were owned by two groups, I believe – one was baseball, the other politicians. We played in the huge Civic Stadium down by the lake there, we had some good games. [Crowds were] not necessarily that impressive [the Stokers pulled in 4,000-6,000 at home games - RnRS ], and it never seemed to really catch fire. We played in the conference final against Atlanta and lost there, so they decided they’d lost too much money and didn’t want to continue. But also around that time the league had lost its network TV contract. Although those contracts weren’t necessarily providing huge amounts of funds – they weren’t – the League had been based on network contracts for long term major revenues, so any time they lost coverage it would drop down for the league and they would lose teams. That in my opinion was the major problem with Cleveland.