Toby Litt's Blog

February 9, 2024

On a Benediction

This is something I’ve been yearning to share for over two years.

I hope those of you who’ve been following the Writer’s Diary will understand.

It’s something I’m proud of and which still moves me.

Whilst I was writing the first draft of A Writer’s Diary, partly during the early lockdowns, one entry in particular came straight out as a little piece that I felt would have a wider life. I had a suspicion people would like it. Partly because it’s gentle and optimistic. I’ve read it aloud a few times, and realised while doing so that it was a sort of benediction.

A benediction especially upon writers, during and after their struggles.

I hope you’ll take it as such.

That original entry ended up as Juli 24.

I tell you,

I don’t know why but some days, like today, the air just feels friendly.

Even gravity helps you.

A while later, in 2021, during another lockdown, I was contacted by my friend Chantal Acda who sings and plays solo, and with Bill Frisell and others, and with the Belgian band Isbells.

Two of the band (Gaëtan Vandewoude and Wouter Dewitt) had written a gorgeous song, ‘What You Give Is What You Get,’ and were looking for some words to go along with/on top of a stop-motion video they were planning to make.

I thought of the diary entry, and rewrote it as a poem.

That became Juli 30.

Rather than just send the text, I decided I’d make a small video to show everyone how it might work — with timings.

I downloaded an image from a NASA website, because I knew their stuff was free to use.

The photograph is called ‘Mammatus Clouds over Nabraska’.

The spiralling clouds, also, seemed to chime with the song and the poem. Same palette, somehow.

Using PowerPoint, I animated where and when the words appeared on top of the image — pressing the space bar to move on to the next line.

When I sent the video to Chantal, she said it made her cry and ‘it’s just more than beautiful’. The band loved it, too. But it’s taken this long while for the song to be released. (Thanks to Chantal and the band for inviting me to collaborate.)

That’s why I haven’t been able to share it with you before now.

And so here it is.

‘Today I can say everything.

And today you can say everything.’

November 13, 2023

Leaving Home, Bye Bye

A Beatles Story

[This was written round the time of ‘All You Need’ – the other Beatles story I posted. ‘Leaving Home, Bye Bye’ appeared in an anthology called Outside The Asylum: The Grist Anthology Of The Best Short Fiction Of 2012 alongside work by Melvin Burgess and Alexei Sayle, edited by Michael Stewart.]

The Beatles sit, left to right, George-Ringo-John-Paul, on a long pink cabriole leg sofa in Brian Epstein’s house, Belgravia, answering questions after a dinner party to celebrate the release of their new album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It is the 19th of May 1967. George is wearing a burgundy velvet jacket with thick stripes. Ringo is looking hip in white shirt, psychedelic tie and bespoke Edwardian-style suit with velvet trim. John is sporting a green frilly shirt, maroon trousers and a sporran. Paul has thrown on a grey pinstripe jacket, mismatched trousers and a thin silk scarf in pink and red. All The Beatles apart from Paul have moustaches. A single reporter, in gray suit, white shirt, blue tie, kneels in front of them, clutching his heavy microphone, trembling.

Paul (to reporter): The first thing I saw – in my head – were these curtains, like, with the light behind them. You know those sort of curtains. Not net curtains but not solid, either.

John: The word you’re fumbling for, old chap, is cheap.

Paul: Yeah, but curtains so you can, like, see through them when there’s a streetlight behind them or the sun’s coming up, which is what’s happening when –

George: It’s five o’clock.

John: It’s fab o’clonk, pop fans.

Paul: – when we meet the girl. It’s a small house on a long terraced street, you know. Two up, two down.

John: It’s an anagram!

Paul: Nothing special, the house or the street. And I suppose that I was thinking, like, that she was nothing particularly special, either. The girl. I could see her, too.

John: Oh, we all saw her.

Ringo: Which girl?

George: None of us have girlfriends, apart from those of us who have wives.

Paul: I don’t know where these things come from, but like they just come to me. And her I saw as, you know, a bit of a Rita Tushingham type.

John (into microphone): Hello, Rita, love. How ya doing?

Ringo: Lovely, Rita.

John: Bhagvad-rita – eh, George?

Paul: Just an ordinary girl in an ordinary house. But when I saw the morning sun coming up behind those curtains, it had a kind of sad melancholy to it.

Ringo: This is in Rita Tushingham’s house? Have you been to Rita Tushingham’s house?

Paul: You know, when the day hasn’t quite begun but there are people up and quietly doing stuff that they don’t usually do. Because she’s leaving –

John: Home. Yes. And she’s never going back, is she? Not to that dump.

Paul: Well,…

John: Not in a million bloody years.

Ringo: What kind of curtains does Rita Tushingham have? They’re not cheap, are they? She’s done alright for herself, our Rita.

George: There are different kinds of light.

Paul: Yeah, George is right. They’re different, even in the same house at the same time of day. Or at least, you notice them as different when you’re doing something different that day.

John: Like leaving home. For ever.

Paul: And sometimes when I see pictures like that, in me head, I get the music starting up, too.

George: Funny that. Tell us more, Mr Lennon-McCartney…

Paul: I could hear it, all with a slow kind of flowing, and moving from one chord to the other without you really noticing when –

John: Go on, Mendelssohn! Get in there!

Paul: – chord changed into the next. I like classical music.

Ringo: Is he still talking about curtains?

Paul: I’ve been digging a lot of, like, the classics recently. They’re really cool.

John: Beethoven is a great fan of Paul’s.

Paul: And I wanted some sort of grandeur to go along with this girl, as she left her girlhood behind.

John (in horror movie persona): Forever, ha ha ha!

Paul: Well, not necessarily…

George: Paul has been educating us about classical music, recently.

Ringo: Oh, aye.

Paul: I wanted the music to follow her downstairs – to sort of tiptoe out of the house with her.

John: Bye, bye, curtains.

Ringo: I like Rita Tushingham.

George: It’s very sad, that bit. I think it’s important that people feel these emotions, and that our music is able to make people feel them. It helps them progress.

John: And then she dances off down the road, doing a jig, because she’s finally escaped –

Paul: But the song has some sympathy for –

John: Yeah, but the girl is like out of the rotten cage, isn’t she? It’s been all her life that she’s been stuck with those twisted old people, and now she’s finally free.

Ringo: I like Rita Tushingham but I like Julie Christie, too.

George: It is a kind of escape, some kind of rebirth.

Paul: Her parents aren’t really equipped to understand the new world that they’re living in – or, rather, that their daughter wants to live in.

John: Yeah, it’s hard to understand Shepherd’s Bush.

George: Even shepherds don’t.

John: Oh, you are still there, are you? Wakely-wakely!

Paul: It hasn’t been easy for their sort, going through the war and then all the gloomy stuff that came after.

John: Choosing curtains.

Paul (to John): Look, I’m trying to be serious here, alright? The man’s asking me a serious question.

George: The serious man with the serious eyebrows.

Ringo: Julie Christie has a smaller nose than Rita Tushingham.

John: You’ve got a smaller nose than Rita.

Paul: Anyway, –

George (to reporter): He’s not like this normally.

Ringo: I am!

George (pointing at Paul): I meant him.

Paul: When she –

John: He’s worse than this normally.

Paul: – leaves the house, out the back door, goes off down the alley – when she’s out, we only follow her for a while. Most of the time is spent with her mother and father. They’re really making an effort to understand. I think lots of people are like that.

John: Well-meaning murderers.

Paul: Look, it was me wrote the song. They’re not murderers.

John: They haven’t been successful, no. But they’ve been trying to kill that girl since the moment she was born. There she is, alone with them in that house, and everything she does they criticize. Every boy she wants to go out with, every thought she might express, they just rip it apart, until there’s hardly anything left.

Ringo: Are they at it again?

George: Another cup of tea?

Ringo: Don’t mind if I do.

John: What she does is absolutely justified. Get out while you bloody well can.

Paul: That is what she does –

John: And what you leave behind you’s just something that you’ve left behind.

Ringo: They’re still talking about the song?

George: Not really.

Ringo: It’s the mother I feel sorry for.

George: It’s going to be painful whoever you are.

Paul: I think George is right. But that doesn’t mean cruelty is a good thing. We all need to try and treat eachother with decency and respect –

George: And compassion.

Paul: And love.

George: And mindfulness.

John: Mind your language.

Ringo: Mind the dog.

John: Ming the Magnificent!

Reporter: If I could just interject –

John: Watch it! This is me best jacket, sonny.

Paul: Go on.

Reporter: In the song, there’s a man from ‘the motor trade’. Is there any particular significance in that?

John: Look, mate, it’s this – that poor girl’s life is so bloody awful that she’ll go off with the first pair of trousers that comes along.

George: They’re his best trousers, too.

John: Old people just don’t understand what it means to be young. They think they were young once, but they weren’t. You can only be young. You can’t look back and remember it and, sort of, be it again. Once it’s finished it’s finished, and you’re practically finished, too, if you’d only admit it. You might as well get in the box and have them nail the lid down. Unless you grab hold of being young while you’re young, you’re never going to be able to do it later, after you’ve sensibly put away for your pension and collected your Green Shield Stamps.

Paul: People do their best, you know, in the circumstances they get given. I don’t think you should blame them for being how or who they are or whatever.

Ringo: Rita Tushingham has nice legs, but not as nice as Julie Christie.

George: Sometimes, Ringo, old chum, I think you are the wisest of us all by quite a long chalk.

Ringo: Thank you, whoever you are.

Paul: Some of the people that hear the song are going to be all for the girl, and some of them will be feeling bad like for the parents, and –

John: Some of them will be right and some of them will be fools trying to stop time.

Paul: The song isn’t there to make a judgement. It’s to make people feel the situation, and then they can make up their own minds.

John: You’re dead wrong.

Paul: Look, we’re not talking about ‘A Day in the Life’ here. I think I know what –

John: I knew that girl. I saw her living in that house and dying every single moment in that terrible house.

Paul: It was in the papers. I read about her in the papers, and I thought about her, then I sat down and I wrote the song. On the piano, actually.

John: She was a lovely girl, not ordinary, and she didn’t have one single piece of bright colour in her life. Not one single moment of joy or wonder. She lived twenty years of grey, behind those curtains. Like a sparrow covered in dust. And if she saw a little moment of brightness, and made a dash for it, then I’m all for her. I’m on her side completely, and against anyone who tries to stop her. I hate people who crush people just because they think they can. No-one should be put in that position of absolute power over another human being – call them priest or father or whatever you want. That’s the worst crime in the world, to kill another person’s heart by killing their hopes. And that’s what they were doing, those two, sitting there in their comfortable chairs and waiting up for her and passing eternal judgement on her for coming back smelling of port wine and aftershave. They’d tell her off for smiling, those skeletons. They’re the sort who put plastic covers on their sofas and never take them off. And if they could’ve, they’d have put a cover on her. She did the right thing. Ran. Thousands didn’t. They’re still there now – sitting and having tea and biscuits with their prison guards.

Ringo: Rita’s not in prison, is she?

George: Yet again!

Ringo: What did she do this time?

George (pretends to whisper in Ringo’s ear): Psst-psst.

Ringo (in mock-shock): I hope they throw away the key.

Paul: I think what John’s saying is, you know, like, you know –

John: Yes?

Paul: I agree with the part about freedom. I’m all for that. But when you just do what you want to do, there’s always going to be some suffering left behind.

George (to Paul): Welcome, brother.

Paul: And if we could think about that, before we did anything, we’d all be a lot better off.

John: Some people don’t think. Some people just kill.

Paul: ‘She’s leaving home’ isn’t about killing. It’s about life.

There are five clear seconds of silence.

John: Look, right, I think it’s a great song. Really. One of the best Paul’s ever done. I’d like to pay sincere tribute to my partner of these – how long is it? – these twenty seven years. I’m going to have to look lively. Sheep up or shut out. He’s no fool, that lad.

Paul: John helped with the chorus. You should ask about ‘A Day in the Life’.

Ringo: I still can’t believe that Rita murdered someone.

George: I have to put up with this all the time. Can you imagine?

Paul: Do you have another question?

Reporter: Yes –

John: As long as it’s not about curtains.

November 10, 2023

All You Need

A Beatles Story

[I wrote this a few years ago. With so much Beatle stuff in the air, seems a good time to put it up here. It was originally commissioned by, and published in, the Times newspaper, 2009. The original title, which I sort of prefer, was ‘Four Blind Mice’.]

PAUL

Paul rips up the drive in his Mini Cooper, so Dot-the-housekeeper puts the kettle on, like always, then trogs upstairs to wake John – who arrives in the Sunroom fifteen minutes later, wearing white T-shirt, skinny faded-pink jeans and house slippers. And Paul, who has been riding four year-old Jules on his knee whilst chatting with Cyn, says, ‘Alright?’

‘I’ve got The Song,’ says John. They both know what The Song is; they both want to be the one to write The Song – because in a couple of weeks the band will be performing it to a very large television audience, almost certainly the largest television audience ever: The Our World special.

‘Really?’ Paul asks, mildly.

‘Yes,’ says John. ‘Come on.’

With a wink, Paul hands Jules over to Cyn – he feels overdressed in comparison to John. He’s in a pinstripe jacket and blue shirt. They climb up through the house. Paul slips off his jacket, hoping John won’t be sarcastic about it.

When they get to Daddy’s Room, where John does his writing, Paul stands and waits to see what John will play – piano or guitar?

Piano, so Paul moves his chair close to the bass notes, sits.

‘It goes,’ says John, ‘like this…’ And he plays three descending chords, bom-bom-bom, bom-bom-bom. Paul expects it to change, but it doesn’t. Bom-bom-bom. John stops for a second, coughs into his fist, then starts again with the same chords. Paul has it now – Three Blind Mice! John has composed Three Blind Mice! But the mice-words have only just entered Paul’s head when John starts to sing Love, love, love. There’s a pause, no chord. Love-bom, love-bom, love-bom again.

John glances at Paul for half a moment – not enough time for Paul to respond but enough to scare him. Paul knows he didn’t have the proper expression on; he was probably, he thinks, looking a bit superior. This isn’t The Song. Three Blind Mice isn’t The Song.

The bom-bom-bom continues, unvarying, but now John starts singing from some lyrics propped up in front of him. There’s nothing… Paul hears, then loses it in John’s dumble-di-di dumble-dum. And then Nothing… Nowhere… It’s easy. And at last the chords change, going not up but sideways. Unless there’s a chorus later, this monotone is the chorus. All you need is love. All you need is love. All you need is and the voice goes up, thank God, love love. Where does he go now? Love is all you need. Oh.

Then it’s back to the verse again, and Paul is already adding harmonies around bom-bom-bom. It needs something. It needs a lot. On the lyric sheet are a list of verbs, from which John seems to be picking at random. Show/shown, know/known, blow/blown. It’s easy, John sings. All you need. Paul nods along. He’s getting it now – and just as he is, John stops.

‘No middle eight, like,’ says John, and reaches for his cigarettes.

‘Yeah. I like it,’ Paul says.

‘Love,’ says John, taking a drag. He plays the bom-bom-bom again, faster, as a comic rhumba. This is more what Paul had had in mind. Something upbeat. Not another John-dirge. John-dirges aren’t as bad as George-dirges, of course. Nothing’s as bad as them. Smoke from John’s nostrils cascades down the lyric sheet and spreads across the yellowed ivory of the keyboard. Without realising it, Paul too has lit up.

‘Play it again,’ Paul says. And when John comes to the end of the verse, Paul plays a jolly upwards riff on the bass notes – dum-di-dum, tum-ti-tum – taking the song back to the start, lifting it a little.

John accepts this, keeps on playing, round and round, bom-bom-bom.

‘How about…?’ Paul asks, and they start to work.

After half an hour, John stops, looks at Paul and says, ‘So, that’s The Song, isn’t it?’

Paul nods. It’s The Song.

RINGO

And when Ringo arrives at Olympic Studios a couple of days later, he has some ideas. He’s going to keep it really simple with the drums – just stay out of everyone’s way.

They start recording, and it’s different from normal. Because the song’s no great shakes to play, Paul’s suggested they all swap instruments. Ringo, though, can’t play anything else. So Ringo happily sticks to his drums. But so Paul is holding up a double bass, John’s sitting at a harpsichord and George – Ringo can’t quite believe it – George is trying his hand at the violin.

‘Okay, boys, let’s try one,’ says George Martin.

They do, and to Ringo it sounds ropey. Catchy but ropey. Ringo is still relieved the song John came up with is so simple. Less chance for them to cock it up in front of the whole world.

Love, love, love, Ringo sings along, not into a microphone.

Take seven.

Ringo looks over at George. He seems to be going at this one really serious, like, despite sounding like fingernails on a blackboard.

Take ten.

John counts them in, bom bom bom, and Ringo – all of a sudden – feels immensely proud. They are so good, his friends. They just come out with this stuff, and then more of this stuff. And we play it, Ringo thinks, and it goes round the world. Everywhere. Places I’ve never heard of. And this one’s gonner go round the world even quicker. This one’s gonner be the biggest yet.

Ringo hits the drums hard, but not too hard, and feels very happy.

JOHN

John is chewing gum. They’ve done two days of rehearsals, and he hasn’t messed up yet. The first words are There’s nothing you can do… How could he forget them? He wrote the bloody things. Yesterday they lined up for the press in four sandwich-boards, each with a word of the title on – everything but Is. Ringo was All, Paul was You, John was Need and George was Love. Yeah, that was about right. That was spot bloody on. John was Need. John is chewing chewing gum. He’s already had Paul mime spitting it out, but he’s keeping it in. It makes him feel secure. Two minutes, says the floor manager. They finish their run-through – just the band, not the orchestra. Paul mimes spitting again. It looks like he’s gobbing on Marianne – Marianne Faithfull – who’s down by John’s left leg. John knows Jagger is close behind him, all dressed up in a butterfly coat. And Keith. And Eric. Forget the millions at home – if he cocks up in front of this lot, it’ll be hell for weeks. John wants to say something. Should he make the old joke? Should he say toppermost poppermost? John says, ‘I’m ready to sing for the world, George, if you can just give me the backing…’ John looks around. There’s bloody balloons all over the place – and some idiot’s brought along a sign saying ‘Come Back Milly!’. Paul’s wearing a smock that makes him look like some art teacher from Bootle. One minute. John’s head feels like it belongs to someone else. Only his jaw, chewing, is John – and if the jaw is his then hopefully the throat will be, too. When he opens his mouth, resting on the jaw, a sound will come out which won’t be jibberish or a scream. The first words are There’s nothing you can do… It feels like his jaw is a piece of straight, hard metal – but it’s still him. Three. Two. Green light. They start to play over the backing track. Bom-bom-bom. Simple. John chews his gum. He’s on – he’s being watched. Marianne is almost touching his leg. She better not touch his bloody leg. Mick is listening. Then George Martin’s voice interrupts. ‘I think that will do for the vocal backing very nicely. We’ll get the musicians in now…’ John says, Oh great, great. Sounding like a phoney. He’s getting too nervous to sing, so he sings – She loves you yeah yeah yeah! It gets a laugh from the heads around his knees, which makes him feel less jagged inside. George Martin asks, ‘Are you ready?’ And Paul says, ‘Ready when you are, Uncle George.’ That’s my line, thinks John. Paul’s pretending he’s not nervous. He plays a little skiffly shuffle on the bass and Ringo joins in. George doesn’t. They’re all cacking themselves. It takes something big to get through to them, these days – after the Royal Variety, after Ed Sullivan – but this has got through. All the way. Too soon a recorded voice says ‘One, two, three…’ and the horns start with that French tune. He’s sung the first line, and he can’t remember singing the first line, but he must have sung the first line because he’s singing now and he knows he hasn’t just started singing. And now he starts watching himself singing, which is dangerous because he needs to be in himself in the singing to make the singing real. So he opens his eyes, just a slit, and sees a red pulse, the colour on Paul’s white and red shoes, keeping time. It’s enough. He’s himself again, singing over his jaw, through his mouth, he’s come back and knows he can stay back for the rest of the song. And afterwards he’ll know it was really him who sang it. It’s easy. Suddenly John feels comfortable, and opens his eyes. Paul is smirking, but he’s smirking – John knows – for all four of them. They’re getting away with it. John decides to sing She loves you, yeah yeah yeah.

GEORGE

George, ecstatic, is sitting in the Studio One Control Room with the others – all apart from John. The crowd of friends has gone home. Perhaps they’ll meet up with them later, in the Bag O’ Nails or somewhere. Celebrate. John wasn’t happy with his vocals, though, when he listened back to them – so he’s in there now, on his own, singing the song again, and none of them are really watching.

When John finishes, everyone applauds. They have all been drinking red wine. George feels incredibly heavy – as if his body were made of something other than flesh.

‘Well done,’ says George Martin, the weariest of them all. ‘I think we’ve got it with that last one – if you’re happy.’

John comes slowly into the Control Room as the tape glinky-glinky-glink rewinds. He slumps down, and they listen back to the thing one more time.

Afterwards, Ringo says he’d like to replace the tambourine at the start with a drum roll.

‘Tomorrow,’ says George Martin, ‘please. We can do it tomorrow.’

He looks awful, the other George. His father died a few days ago. His wife is pregnant.

‘You can go home,’ says Paul.

The other George shakes hands with each of them before he leaves the room.

It’s just the four of them, now, within earshot – Mal, the others, the drivers, they’re a shout away, waiting. George tries to breathe meditatively.

‘Phew,’ says Ringo. ‘Nice job, lads.’ He keeps talking. ‘And positive. Love. Something everyone can agree on.’

‘Yes,’ says George, exhaling. ‘It was amazing.’

‘Yeah, says Paul.

‘No,’ says John. ‘I had something very specific in mind, when I wrote the song. Love, not all these wars and death. But I’ve sung it that many times now I’m just not sure about anything any more. I don’t know what love means. I’d like to. I mean, I’d like someone to just come along and give me the answer. But they’re not going to, are they?’

‘They think we know,’ says George, upset. ‘Those people watching us. We maybe changed their minds.’

‘Love,’ says Paul, ‘is trying to help things along. It’s looking on the universe and wanting positive things to happen.’

‘Love,’ says George, ‘is a universal force that holds everything in balance, including love.’

‘Yeah,’ says Ringo. ‘I agree with Paul and George.’

‘But George and Paul don’t agree,’ says John. ‘Do you?’

‘I think we do,’ says Paul. ‘Sort of.’

‘My kind of love contains his kind of love,’ says George.

‘I want that love,’ John says. ‘I want it, because right now I’m further away from it than ever.’

‘Love’s a big warm feeling deep inside you,’ says Ringo. ‘A bit like cognac, only better.’

‘I mean, how can I go on and on, singing about love,’ John asks, ‘when I can’t even love you lot? And I can’t. There’s too much there.’

January 21, 2023

A Writer’s Diary Launch and 30% Off

Hello,

I hope you’ve been enjoying the last few days of the diary.

I have exciting news –

This Tuesday evening, there’s a launch event for the book version of A Writer’s Diary – online – and here is your invitation.

I’m delighted to be speaking with Sally Bayley, author of The Private Life of the Diary.

If you’d like to attend, please email info@galleybeggar.co.uk.

Alongside this, Galley Beggar have kindly offered a 30% discount on hardback copies of A Writer’s Diary.

Just enter WRITERSDIARY2023 at checkout. Link here.

Hope to see you on Tuesday.

All best,

Toby

November 28, 2022

Why not just sit and write some more about climate?

Following my participation in the recent non-violent, non-polluting Extinction Rebellion actions, now seems a good time to repost this. By way of explanation.

On January 28 2020 I introduced Clare Farrell, one of the co-founders of Extinction Rebellion, at the second Writers Rebel event.

The first event took place last October, on Trafalgar Square, where 40 writers – including Ali Smith, Robert Macfarlane and Susie Orbach – read and gave speeches.

At that event, I read Blake’s ‘What is the price of Experience?’ as a mic check – getting the crowd to read along with me. It was extraordinary, to feel the power of Blake’s words.

Before I read, I said that I was sure that Blake, if he’d been alive, would have been there, would have been taking part in the protest.

For the second event, I was asked to say a little bit about writing and protest. Here’s what I said –

I like to sit.

I’m a writer. I like to sit.

I’m a Buddhist. I like to sit.

But here I am. I’m here, standing. Standing up in front of you, talking. Directly. Politically.

Thank you for coming. Thank you for being here. You could be somewhere else.

I could be somewhere else. Sitting. Because, like you, I’m a writer – and, for me anyway, that means more than just about anything else, I like sitting at my desk and writing.

It takes something to get me out of the house. Also, I’ve tended to agree – in the past – with the advice that getting too involved, too politically doctrinaire, hurts the writing, and takes time from it.

And so I’ve voted Green in most elections, and after Trump was elected I joined the Green Party. As something to do.

But I haven’t committed to any kind of political action that was likely to get me arrested. I’ve been on marches about university tuition fees, against war, against Brexit. But I haven’t become involved in organising civil disobedience.

Now, with the world as it is, with the climate crisis as extreme as it already is, I feel I have no choice but to become more involved, more committed – committed to Extinction Rebellion.

Why? Why Extinction Rebellion?

Well, I don’t know how old you are – I don’t know if you remember the 4-minute warning. 4 minutes until nuclear holocaust.

During the 1980s, I spent quite a lot of time thinking about what I’d do when the 4-minute warning sounded.

I was fairly sure it would sound.

Eventually, I settled on two courses of action – either I would run out onto the street, to try and find someone of my age to lose my virginity with, or, more likely, as the streets of Ampthill, Bedfordshire, probably wouldn’t have contained anyone capable of helping in that endeavour (they hadn’t so far, obviously) – or more likely I would put on ‘Imagine’ by John Lennon.

‘Imagine’ lasts a few seconds over 3 minutes, so I reckoned I could get it played start to finish by the time the nuclear blast hit.

At the time, looking at adults, looking at the madness of Mutually Assured Destruction, looking at Ronald Reagan, I wondered why everyone wasn’t already out in the streets – doing one thing or another.

I wondered why, things being so bad, so extreme, the whole human race wasn’t protesting.

Coming into the very recent past, I was still wondering why there weren’t mass protests everywhere about environmental degradation? Why wasn’t there resolute, global action?

Well, now there is – now, there are millions of people out on the streets. They are focussed, organised, and they have a sense of urgency.

It is Extinction Rebellion which has given the focus – at least in the UK.

If there is a single thing that has caused me to want to do more, to want to do whatever I can, then it’s just this: within my short lifetime, I’ve witnessed the English climate change.

You’re seen it, too.

We’ve seen bird and insect numbers collapse. We’ve seen winter becoming sometime muggy, rather than freezing. We’ve seen trees blossom in December that used to come out in March.

And that shouldn’t happen – that kind of change shouldn’t be perceptible within a single human lifetime.

It’s a planet we’re talking about, not a back garden.

I’ve seen this in a place, in a country, that is generally quite isolated from extremes of weather.

It’s true, I have benefited from many of the industries and systems that have caused environmental change. I’ve bought the plastic, eaten the meat. But I realise that just changing my own consumer habits is not enough. That’s continuing to sit.

I need to try to make more of a difference.

What we need now is individual commitment to collective, global action – political action; sometimes obstructive, sometimes annoying to people who just want business as usual, sometimes infuriating to them.

As a writer, like you, I have always tried to find my own words for things – not to take on slogans. But, at this point, I’m happy to copy an eleven year-old school striker carrying a placard that says NO PLANET B.

Because they’re right.

There is NO PLANET B.

We have caused the mess, with our dynamism and our laziness. We have put the energy into the ecosystem. Now we need to clean up our own mess. We need to take the energy out.

It can be done.

I’m a writer, so Writers Rebel is where I’m going to make my contribution, put my commitment, spend my time, make my stand.

And if the writing gets suffers, it suffers. And if the writing gets worse, the writing gets worse.

I don’t think it has to.

Maybe you’re where I am, maybe not.

This evening is a chance for you to think about what you want to do, or not do.

This evening is a chance for you to think about where you sit.

—

Here’s a link to Extinction Rebellion.

And here’s the Writers Rebel blog.

November 22, 2022

My Arrest

Yesterday morning, at around 11.20, I was arrested for the first time in my life. As far as I’m aware, no member of my family has ever been arrested before. It felt embarrassing, empowering, necessary.

I was arrested after taking part in a non-violent direct action on behalf of Writers Rebel. This involved the pavement outside the Institute of Economic Affairs and a dark liquid that was non-toxic, vegan, biodegradable. It was part of a wider Extinction Rebellion campaign to highlight the enablers of continued the expansion of fossil fuel production and consumption. (Yes, the guys.)

In the immediate aftermath of COP27’s complete failure, it felt good to act.

I’m fine today – if you were concerned. I was courteously treated, charged with Criminal Damage, held until just before midnight and released on bail. Natasha Walter, who was arrested too, is also fine.

A full explanation of the reason for our action is on the Writers Rebel website.

I am very aware this kind of thing (Down With This Sort of Thing) annoys a lot of people. Twitter today is making me even more aware. Lots of people don’t approve of these mess-making tactics. However, I have been employing many of those tactics these people do approve of (signing petitions, going on marches, raising awareness in my work) for the last three years with a great deal less impact than this one messy act.

Back when they started, it was what Extinction Rebellion conveyed of the urgency of the global situation that made me join them. (I am also a Green Party member.) As their Westminster Bridge banner said, ‘Climate Change – We’re Fucked’.

I have been thinking about whether to take part in a ‘spicy’ (arrestable) action ever since October 2019 – when I was one of the readers at the first Writers Rebel Marathon. (Yesterday, Natasha and I recited this same William Blake poem just after we finished pouring. Full circle.)

So this has been something I’ve considered from many angles for a long time. I’ve written about it for the London Magazine (not online). I’ve spoken about it when I had a platform – the need not just to write but to be physically present.

I think that’s what the writers of the past that I love the most, as a reader and a writer, would have us do. From radicals like Blake and Shelley to High Tories like Wordsworth.

Blake saw the dark satanic mills of the Industrial Revolution (other ways of referring to it available). He knew pollution and environmental degradation. But if he’d seen where we are today – floods, fires, heatwaves, insect deaths – he’d surely have lost it completely. He’d have asked how we got here. He’d have wanted to know what he could do to stop things getting worse.

This act was my small, fallible contribution to trying to stop things getting much worse.

Thank you for reading this.

Extinction Rebellion’s crowdfunder to support legal cases is here.

October 31, 2022

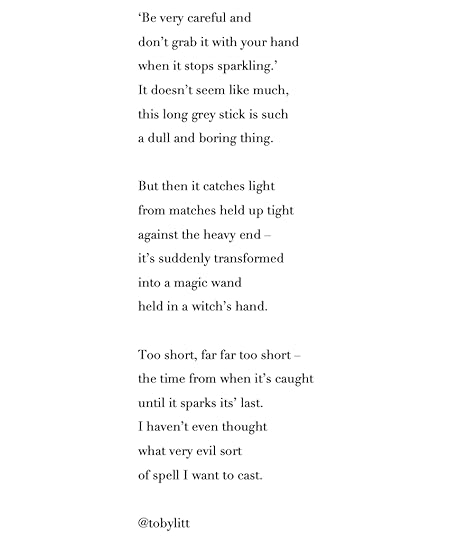

The Sparkler – A Hallowe’en Poem

October 10, 2022

We Can Send Letters

I’ve been focussing on A Writer’s Diary, over on Substack, for most of this year. It’s been going really well, and I’m grateful for all the support I’ve had from readers of this blog.

However, there have been other things going on. Today, for example, I made public a letter I’ve written to Terence Mordaunt, one of the Trustees of the Global Warming Policy Foundation.

Clearly, he and I disagree on a lot of matters. But it’s not an aggressive or shaming letter. Rather, in writing it, I tried to look back on his life and wonder about the decisions he’s made.

Terence Mordaunt is a very successful man – worth millions – much of it earned through his involvement in the Port of Bristol. And as well as the GWPF, he’s a Trustee of the Outward Bound Trust.

I have fond memories of going on Outward Bound weeks when I was eleven or twelve. I had a great time. It was all about going a bit wild in nature.

You’d think that someone involved in that would be more concerned about preserving the nature that future children are going to go wild in.

Writers Rebel is publishing a letter to a different Trustee of the GWPF every day this week. Sir Jonathan Porritt and Monique Roffey’s letters are already out. Please share on twitter and elsewhere, if you feel like supporting us.

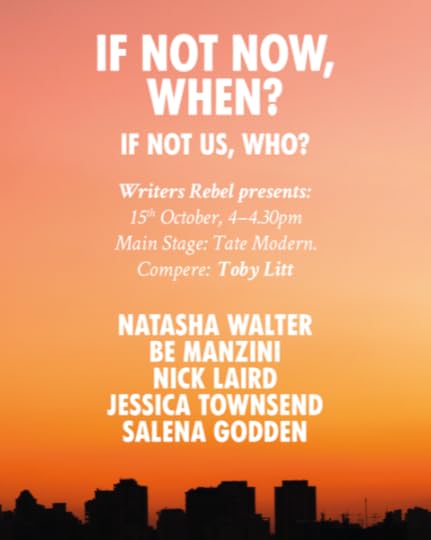

Also for Writers Rebel, I’ll be compering a great reading in London – this Saturday – outside Tate Britain. If you’re able to make it down, please come along and say hello.

April 26, 2022

Sustaining

This lecture was delivered to Creative Writing students at Birkbeck College on April 26th 2022.

I still love the smell of petrol – I can’t help it. It’s warm, sweet, powerful, modern. It makes me remember sitting in the hot backseats of my parents’ golden Peugeot 504 Estate, windows down, me and my sisters, waiting for my father to fill the tank with French essence – not petrol, essence. We would be driving from Calais to campsites with a swimming pool in the Dordogne, the Pyrenees. Or we would be driving to a beach, a river, a restaurant, a château. Or, at the end of the four or five weeks, all of us now darker than the car (because in 1976 sunbathing was good for you), we would be driving back to Calais. More than once, the day we drove back was August 20th – my birthday. I had several birthday parties in the laybys of Brittany and Normandy. All holiday, my mum had kept my presents wrapped and hidden in her suitcase. I would unwrap them in the middle of a gentle haze of exhaust fumes.

A Scale Model

A Scale ModelI love the smell of petrol, but now, when I smell it, I know it smells of things other than the most luxuriant days of my childhood.

What I’m going to say today has been hard to write. It feels nowhere near as finished as some of the other lectures I’ve done, but I think that’s down to the subject – it’s emotional and global, it’s confusing and very simple. It involves guilt as well as anger. I know I’ve not managed to say everything as I should. Very often, in speaking of this subject, I join in with the general politeness, and positivity, and end up saying less than I mean. I’m still trying to figure the most basic things out, as, I think, are we all.

Is that a good memory, of France, of turning eight? What is a good memory? What do we do with our petrol-soaked past? What do we do with all the things we expected of our future – the powers, the distances? How do we keep going, with such exhausting confusion? What do we do? What should we do?

In my case, keep writing – writing my way towards an understanding and expressing of attempting a possible sustaining.

Beginning

I don’t like the word sustainability – it already feels brittle with having been stretched too far, stretched to cover the whole future of the whole planet.

Sustaining is a little better – suggesting a voice holding a high note, or food hearty enough to keep you going until the next meal.

Sustainability or sustaining – I can’t think of a quicker and more direct way of getting across what this lecture is about: it’s about how you can keeping going, as a writer, in a way that means your writing can continue to develop and deepen.

That can sound like quite a grind: keeping going.

Anyone who has written a novel, or a full-length work of non-fiction, will confirm that much of it – the process – is nothing but grind. And much of the secret of finishing is simply the obviousness of having kept going.

This doesn’t rule out gray periods of being stuck, giving up, of forget it, no, actually, forget the whole thing; and nor should it imply there will never be irridescent days of easy flow and miraculous invention.

Even writers have occasional days when they really feel like writers.

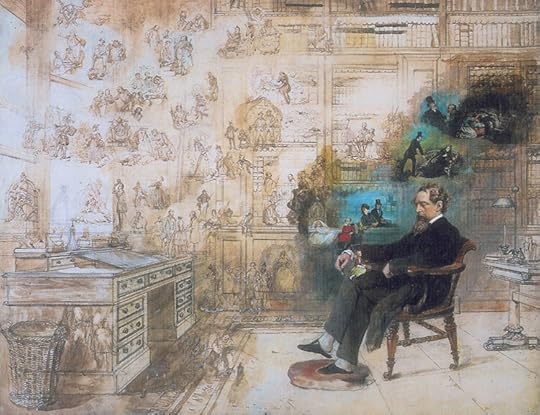

Dickens’ Dream, Robert William Buss

Dickens’ Dream, Robert William BussVery often, though, they feel like accountants, lawyers, project managers and tech support. (They also feel, on occasion, or for months at a time, like solo round-the-world yachtswomen, serial killers, archaeologists or morticians.)

All writers – all writers who intend to write more than a single book – need to work out ways of sustaining themselves through the grind.

Today, I’d like to help you think about sustaining yourself, as a writer, and sustaining the conditions around you that will allow you to continue to be a writer.

Small conditions of the desk, and vast conditions of being.

Today, I’d like to suggest that what is sustainable has already changed, and that what will be sustainable in future is certain to change even more – to the extent that it’s no longer recognisable, or perhaps even desirable.

But it still somehow seems like there’s a safe place, and everyone wants to get through the door before it’s shut.

I think a lot of workers, in a lot of different industries, have developed what I’d characterize as a bank robber or a Booker Prize mentality. ‘Just one last job,’ they say to themselves. ‘Just one big steal, then I can retire on the proceeds and buy a farm and live a good life.’

The job of writing is not one big steal. The job isn’t getting to a publishable level, once, with feedback from fellow students, with tutors’ advice fresh in your ears. The job is maintaining, year after year, an absolute consistency of attentiveness to and presence to language.

In other words, being able to say, ‘I am a writer’ and for that to be true.

Micro to Macro

I have begun bleakly as I feel that’s where we all might end; and I will return to the possibility of a completely other landscape, based in the ruins of our cities, before I move on to some more hopeful territory. But first I’m going to look at your basic material conditions.

I am going to move out from the microcosm to the macrocosm, just as the film Powers of Ten does. As everyone who has been taught by me in the last couple of years has seen.

(If you play it, please turn off the sound.)

Let’s start with sustaining you, physically.

The Body

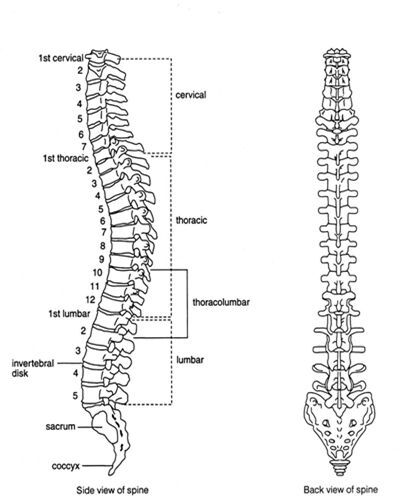

Let’s talk about your spine.

Ouch.

Ouch.Some writers write standing up. Towards the end of his career, Philip Roth’s back problems had become so catastrophic that he wrote whilst on a walking machine. Virginia Woolf wrote standing up, as did Ernest Hemingway on top of a bookshelf and Saul Bellow and Stan Lee and Vladimir Nabokov at a lecturn. And also Gogol, Kierkegaard, Dickens, Victor Hugo. (Yes, I’m aware they’re all but one of them men. I couldn’t find examples of women.)

However, writers are mostly sedentary animals.

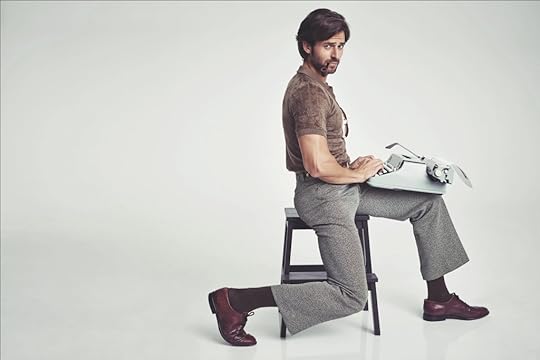

Search for copyright free photographs of writers, and what you will find is someone retro and gothic on a typewriter, or – more often – with a mug of coffee or herbal tea beside them, sitting on the floor, or cross-legged on a tastefully grey sofa, or this guy –

This is bullshit. If this is how you aspire to write, or actually do write, you need to stop right now. It isn’t sustainable. To be able to manage long hours of work, or actually type for any decent period of time, you need a good sensible posture. Ergonomics.

You need a good chair. I would advise you to spend whatever you can afford on the best second-hand office chair you can find. Aeron are great; others are available. Ideally, it should be fully adjustable for height, angle, where the arms go. It’s also a good idea, for hot summers, if the bits that support your back and bum are porous mesh.

You need a desk or table at the right height. Perhaps you’ll find these things in your kitchen (rented or owned), or in a local café. Perhaps you’re lucky enough to have a room of your own, with a chair and desk of your own. If you’re going to sustain writing over a long time, these are things you’re going to have to work towards.

It’s better to work on a desktop computer with the screen raised to eye level or just below. If you write a whole novel like this, you will avoid killing your spine. Most writers, like most humans, have bad backs.

They’re not this guy –

Who is This Guy? What has he written?

Who is This Guy? What has he written?Ideal conditions are not always ideal conditions: I knew Sue Townsend, the writer of the Adrian Mole books, and The Queen and I. She told me once that she’d had a marvellous office built for her, at the top of the house, with a large window, and wonderful light – but she never once used it. She still worked in a cleared space on the kitchen table, with the ironing on one side and a crumby plate on the other. The bespoke study didn’t feel like hers. She probably felt she’d write worse there. I think she was right.

Ideal conditions are not always ideal conditions, but a fucked up spine is a fucked up spine.

It’s good for you to alternate between typing and writing by hand, so everything isn’t typing. This, at least, varies the angle of your body, and the focal distance of your eyes. I once had a job making subtitles for TV programmes – Emmerdale, Blind Date, The Bill. The days involved nine and a half hours of typing. If I wanted to write on top of this, which I very much did, I could only manage it in a different form, with a different posture – that is, with pen and paper.

Eyesight

You should look after your eyes. Make sure the screen is neither too dim nor too bright. Have the font in a comfortable size. A bigger screen, where you can compare two pages alongside one another, can be useful. (But here I am advising you to buy things you, and also us, might not be able to afford…)

Take regular breaks.

(I don’t, but you should.)

Maybe not as often as one every fifteen minutes, as usually advised, but do get up at least once an hour.

Exercise

Margaret Atwood, in her essay ‘Polonia’, wrote, ‘If you want to be a novelist, do back exercises daily – you’ll need them later.’ [Burning Questions, 2022, pg 21.]

I once went to an osteopath with my spine problems. She told me to exercise. I expected her to give me some especially writerly stretches. ‘What exercise?’ I asked. ‘Any exercise,’ she said, ‘if you want to keep going.’

Walking is good, but I think you need to do something that is aerobic and stretches your muscles. Walking is too much like writing. I can only do it in a hunched up and concentrated way, as if I were still at the desk – as if I were looking for a lost ten pound note. Instead, I go swimming. Lots of writers go swimming.

Haruki Murakami runs, and has written about it in What I talk about when I talk about running.

This is part of the grind – the physical grind of sitting for eight or more hours a day.

Margaret Atwood knows all about this. She’s full of wisdom, and she can usually be persuaded to share it.

[At this point, I played a message of greeting from Margaret Atwood to Creative Writing students at Birkbeck College. In it she gave as her wisdom, ‘No-one sees it until you show it.’ You can listen to it, if you like.]

Outtake from Writers Rebel interview with Margaret AtwoodSummary

All of this adds up to one thing: If you want to be a full-time writer, if you want to have something to show to them, you need – physically – to be able to write full-time.

You need to create the material conditions in which this is possible.

All that workplace ergonomics stuff from the 1970s, it holds true. It is very hard to write well, and almost impossible to write for a long time, if you feel like someone is repeatedly jabbing a ballpoint pen in to your spinal cord.

Alexander Technique, Ashtanga Yoga, Swedish Exercises, lying feet up on the floor listening to Joni Mitchell’s Blue for the thousandth time – whatever it takes.

Apart from chocolate.

Try not to make chocolate or cigarettes part of your writing routine. (For much of the twentieth century there was a dialectic between typing and smoking – though it is, of course, possible to do both at once.)

Cigarettes were a beautiful pivot-point of writerly being: Write whilst within the tension of increasingly craving a smoke; re-read whilst within the relaxation of smoking; exhale creatively, inhale critically.

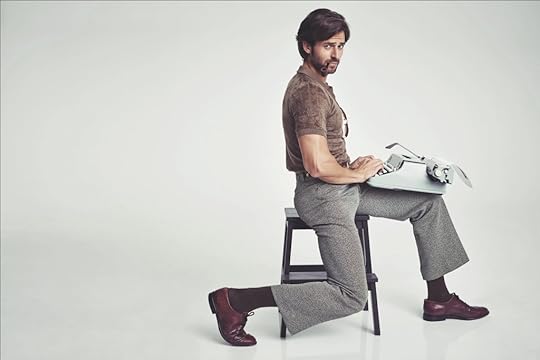

Our time now, in our clear-aired rooms, is not so easily divisible. (I am not advising you to take up, or to go back to, smoking; though it’s hard to wish that, say, Albert Camus or Clarice Lispector hadn’t smoked.)

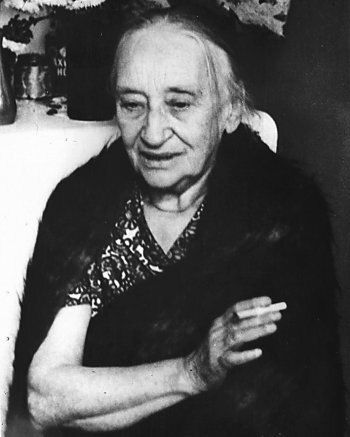

Clarice Lispector, so much X Factor

Clarice Lispector, so much X Factor

Albert Camus, such a glamourpuss

Albert Camus, such a glamourpussThe Writing Itself

How do you sustain the writing itself? How do you keep it going for long periods of time – days, decades? Those who find this easiest are those whose form of grind always gives them something to do – the biographer never lacks a task, the novelist (until the final signing off of proofs) always has some double-checking they can turn to. It’s the short story writer and, even more so, the poet who have difficulty joining up one period of writing with another. Some solve this problem by becoming editors of anthologies – which is a little like becoming a biographer; others drink or get intoxicated in some other way. It is hard to turn up regularly at the page when the moral of your work is that the poetry of life exists only in the irregularities, the assymetries, the ecstacies.

(The Lispector/Camus swap was deliberate, btw.)

Many writers sustain themselves by writing books in series. Publishers look very favourably on detective fiction or thrillers that follow on, one from the other. If you take the model of Walter Mosley, Patricia Cornwell, Mark Billingham, or Birkbeck’s own Amer Anwar, you’ll always have another book to write – a book that someone (always granted that the previous ones have sold) will want to bring out and promote. Because when you’re promoting the 11th book of a series, all of which are pretty similar, you are also promoting the previous ten books and yourself as a brand. Synergy.

However, and this is quite a big however, writers who return again and again to the same main character, characters, world or genre risk becoming bored, frustrated, angry. It can be catastrophic for their ego to believe that readers want them for one thing and one thing only. Like Conan Doyle, with Sherlock Holmes, they often try to kill off their Unique Selling Point. Then resurrect them.

The point these writers are at – a point you may envy – of being established, bestselling, recogniseable, may be the peak of their self-disgust. Imagine sitting down in your comfortable Aeron chair, at your perfect-height desk, every day – knowing that your job is to continue inventing worse tortures and more and more ingenious murders. Or that you had to aim to make people laugh out loud three times a page – even today, even with the news being what it is. For some writers, this self-repetition would be their ideal; for other’s, it’s a deal with the devil.

Perhaps you think I’m being too limited in my thinking. Crime writers can turn away from writing crime whenever they want, can’t they? Comedy writers can suddenly get serious.

Yes, writers can reinvent themselves, and change genre, but such 90 degree or 180 degree turns make editors nervous. And they make Sales and Marketing people despair.

Publishers – by which I mean everyone present at an acquisition meeting – want to know they have an author who the readers will recognise and follow and buy, even if they do introduce the odd jink into their straight path. Recent examples of writers to whom readers are very loyal are Maggie O’Farrell, Rachel Cusk, Tsitsi Dangarembga. Their success has been cumulative. Wherever they have gone, they have taken most of their readers with them – and added some more. (It helps to be regularly nominated for major prizes.)

From my side of things, which is not profitable, a more sustaining writing life than the crime serial stems from a deep fascination with what writing is, and what it can do that it hasn’t quite done before. This is writing as an attempt at art.

Here is Andrei Tarkovsky, speaking about another artform – cinema.

“It’s not hard to learn how to glue the film, how to work a camera. But the advice I can give to beginners is not to separate their work, their movie, their film, from the life they live. Not to make a difference between the movie and their own life. Because a director is like any other artist: a painter, a poet, a musician. And since it is required from him to contribute his own self, it is strange to see directors that take their work as a special position given to them by destiny, and simply exploit their position. That is, they live one way and make movies about something else. And I’d like to tell directors, especially young ones, that they should be morally responsible for what they do while making their films. Do you understand? It is the most important of all. Secondly, they should be prepared for the thought that cinema is a very difficult and serious art. It requires sacrificing of yourself. You should belong to it, it shouldn’t belong to you. Cinema uses your life, not vice versa. Therefore I think that this is the most important. You should sacrifice yourself to the art. That is what I have been thinking about recently in my profession.”

Andrei Tarkovsky, Voyage in Time, 1983

Writing uses your life, not vice versa.

The Books/The Paper

I’m now going to turn to the book itself, and to the publishing industry.

If you are a bestselling author, one of the earliest questions in the lifecycle of a book is ‘How many acres of trees in Norway do we need to buy for the wood pulp to print this?’ (A very bestselling author I know told me that when her editor has a good feeling about a book, and wants to print another 50,000 copies, they immediately buy up a bigger acreage.)

A bestselling author is the direct cause of large areas of deforestation.

Although the FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) logo, present in many books, suggests these trees are from sustainably planted areas, that’s not true. Much older growth is still being felled in order to print the latest literary novel.

Hmm.

Hmm.94% of the environmental cost of a book comes from the paper it’s printed on – not the writing, distribution or storage.

We will need to ask, very soon, which books are worth this? The market says, Books people want to read today.

I suggest, Books people will still want to re-read in five years’ time.

(The market is currently stronger than all opposition to the market. It is also, unsurprisingly, better at marketing its views.)

Books will need to be recycled into other books – using post-consumer waste – much more than we’re doing now. (At the moment, it’s better to read a novel on your phone, the phone you already own, than buy a Kindle or a hardback.)

Perhaps not in five years’ time, but definitely in ten, the books business is going to be a very different place. In the interim, there will be very large amounts of money to be made from distracting people, from giving them virtual anxieties in sympathetic genres – your novel, too, can be adapted for Netflix. I don’t know what state of mind you’ll need to be in, to be capable of doing this, writing those books; it’s no longer one I’m able to achieve. But perhaps I shouldn’t be telling you things you might not want to hear.

People never rejoice when you gift them a new anxiety.

Which brings our Powers of Ten macro-level up to that of climate.

Climate

Often, when I mention ‘climate’, to shorthand it as that – shorthand ‘climate emergency and biodiversity crisis’ so I don’t have to keep saying the words ‘emergency and biodiversity crisis’ – there’s a visible flinch in the audience. Oh no – why here? Didn’t we come here to get away from that?

You could argue that writing, in all its forms, even dystopian TV and cinema, affords us our main away from that.

Andrei Tarokovsky, Stalker

Andrei Tarokovsky, StalkerDystopian fictions offer the comforts of dramatic structure. As collapses, they are formally satisfying.

But often when someone speaks about climate in a concerned or an alarmed way, they are immediately seen as a party pooper. Unfortunately, this particular party needs quite a lot of pooping.

I wish this wasn’t the case. How I wish this wasn’t the case! I wish I could have given you a straightforward lecture on the short story, or on point of view and time.

And how I envy the writers of 1850, who could see industrialisation as progress, or the novelists of 1950, would could look away from Hiroshima and Nagasaki and pretend the happenings of the drawing room really were events of note. But the Industrial Revolution and the coming of the Atomic Age were both foreshadowings and direct causes of the Climate and Ecological Emergency. It was once possible to see them as other than they now appear – just as it was possible for me to unquestioningly love the smell of petrol.

But I don’t think that point of view is sustainable any more. I don’t think it’s an honest story to tell. If I’m in an emergency, then I have to act as if I’m in an emergency. I have to speak directly about it – if clumsily, if inaccurately.

We’ve been here before. A communist, looking at where capitalism had brought the world in 1916, would have felt a similar urgency. A member of CND, seeing how the Cuban Missile Crisis played out in 1962, would have felt it. For similar reasons, both a global socialist revolution and universal nuclear disarmament are depicted as dead hopes. And yet the slogan which most drew me to Extinction Rebellion, apart from this one ‘Climate Change – We’re fucked’ was ‘Another World is Possible.’

Since 2019, I’ve been involved with Writers Rebel – part of Extinction Rebellion. I’ve been editor of their website. I’ve written a short book for them, called How to Tell a Story to Save the World. And one of the things we say we’ll do, as members of Writers Rebel, is bring up climate whenever we have a public platform, such as this one.

Believe me, I wish it were down to someone else to remind you of this, again. To awkwardly bring it up. But I firmly believe that politeness and avoiding embarrassment are – within a British context – a major part of what is holding us back. That’s what mainly annoys people about Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil – that they will keep insisting on mentioning what we’d all prefer to ignore. They tediously insist. God, not them, again. Sticking themselves to roads, again. Can’t they just shut up? Can’t they stop inconveniencing hard-working people who just want to go about their day-to-day business?

I’m afraid they can’t.

If they didn’t do that, insist upon the emergency, then the media wouldn’t cover it; if the media didn’t cover it, the politicians wouldn’t care about it; if the politicians didn’t care about it, they wouldn’t act on it; and if they didn’t act on it, then we would – collectively – be doing nothing – or what amounts to nothing.

Something, amounting to pretty much everything, needs to be done.

Please be assured – in all of this, I’m not saying that writing is only worthwhile if it directly addresses climate, or is full of explicit protest.

I will try to express this as simply and unmelodramatically as I can: the basis of writing has not changed, but it has been shown to be other than what we thought it was.

The realisation of this, the recognition, has come much later to those living in the northern hemisphere than it did to those in the global south. Within the study of imperialism and colonialism, it is a given that the basis of ‘developed societies’ – with their infrastructure and legal systems – is exploitative, polluting, genocidal and racist, and that it has always been dependent on turning the goods of other countries into commodities, and their people into slaves.

If you’d like to read more on this, I’d suggest Kathryn Yusoff’s A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, and the books in its bibliography.

Many human extinctions took place hundreds of years ago; many are continuing today.

It is only recently that something similar to this revelation and revaluation has become unavoidable within an ecological context – and that revelation and revaluation is ongoing.

What does it mean, for example, to drive your kids out to see the latest superhero movie, and then treat them to a Maccy D’s afterwards? What effect does that act of generosity and love, if also a little of giving in, have upon the world? What does it depend upon and what does it continue to call into being?

William S. Burroughs said of his novel Naked Lunch, and I think the words are themselves a revelation: ‘The title means exactly what the words say: naked lunch, a frozen moment when everyone sees what’s on the end of every fork.’

(Perhaps a McDonald’s hamburger avoids being a naked lunch by being eaten without a fork.)

We are slowly coming to see, as if tracing the bright line backwards through sockets, wires, transformers, meters, mains, pylons, distribution plants, power stations, sometimes nuclear power stations – we are starting to see our energy as questionable. What do we make of it? What does it make of us? These are now a subject. (Even more so following the Russian attack upon Ukraine.)

To me, at least, they have become a self-consciousness (as those of you who have been reading my Diary will be aware).

This might go some way to explaining why a recent entry (26th February) began: ‘Is it immoral to use electricity?’ And why, as well as I’ve been able to express it, I included this sentence – on February 28th – about the world of market forces: ‘Just because a product is legal to consume does not make it ethical to produce.’

Among these unethical products I would not only include obvious ones such as private jets, SUVs and the BBC’s Octonauts’ magazine (with plastic crap on the cover of every issue).

The state of it.

The state of it.I would also mention mobile phones with a built-in obsolescence of three to four years, and laptops that stop running their constantly updated operating systems after seven to eight years.

Nature

Much of what I’ve mentioned so far relates to the manufactured world, and is on the level of transactions. These products are the material basis of our society. I wrote this, and made the PowerPoint, on my computer. But there have been technologies since one stick was sharpened, since one stone was piled consciously upon another. What has changed even more profoundly, and the change is retrospective – changing also the meaning of what humans made and thought in 1500 CE and 2000 BCE – what has changed is Nature.

In a Swedish novel written in 1950, the flowering of the apple trees in Spring, the freezing of the mountain streams in Winter, the reaping of the corn in Autumn, the turning of the seasons, that is a fact; in 2022, it is a conceit – it is nostalgic wishfulness – it is part of the problem.

A Swedish novel, or a Ukranian novel.

(I have to be nationally specific about this because, as the Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott pointed out on many occasions, hot and cold seasonality as a way of doing the passage of time, or the return of hope, was never a resource available to Caribbean writers. But Caribbean writers still have the natural metaphors of cutback and regrowth, of planting and harvest.)

Although it’s a very grand statement, probably the grandest I’ve ever made, I think it’s demonstrable: the central metaphor of human culture is the cyclical revival of nature.

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?

That’s how Shelley puts it in ‘Ode to the West Wind.’

Little darling, it’s been a long cold lonely winter.

Little darling, it feels like years since it’s been clear.

Here comes the sun…

That’s how George Harrison puts it.

Up until recently, Nature could be guaranteed to restore, in fact to resurrect what had died – perhaps not in the same form, perhaps radiant and glorified, perhaps as mould or slime.

That is over. That is no longer true.

Extinction is forever. I have never seen a dodo, except a stuffed one. When all the coral reefs of the world bleach, including those of Saint Lucia, there will never again be coral reefs – or not for millennia and millennia. Writers from islands covered over by rising seas will have nothing but the wilderness of exile and the salt of memory.

There are one-way processes in action, curtailed cycles.

(Looking beyond a human timescale, there have been extinction events before – five of them. But I’m assuming you’re not going to take much comfort from whatever evolutionary Spring follows a Nuclear Winter or a High Summer of desertification.)

I think this changes the meaning of what has been written, and changes the nature – the Nature – of what can and should be written from now on.

All fiction is climate fiction now. Either you’re looking at it, or you’re looking away from it. The direction of your looking is in relation to our relation to Nature.

What once restored us we ourselves need to restore, or we will die from its lack.

What was once our poetics of renewal has to become our politics of survival.

What depends upon the irreplaceable is, by definition, unsustainable.

I don’t believe, however terrible things get, that human beings will stop writing for one another, or rewarding those who write movingly and memorably. But whilst it’s been proved possible to plan a novel, and even to compose and memorize a sequence of poems, whilst in extreme poverty or in a labour camp, it’s unlikely that a future society based on subsistence farming, or on cannibalizing the dead technology of the past, will have the free time for more than songs, raps, jokes and myths.

If you’d like a version of this, a revived oral culture in a post-apocalyptic world, take a look at Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban. This is one of the greatest twentieth century novels. Within the society Hoban pictures, words are still important – sometimes a person’s life and death depends on correct intonation – but there’s no such thing as publishing, or an archive. There are important speakers, and many storytellers, but no short story writers. It’s a horrible, avoidable world.

Obviously, the best way for this not to happen to all of us is for all of us to make sure this cannot happen.

Survivalist Literature

Writing is very robust. All texts first exist in a single manuscript or typescript. ‘Hamlet’. Beloved. Only a single copy of a book needs to survive for it to survive. The Diary of Anne Frank.

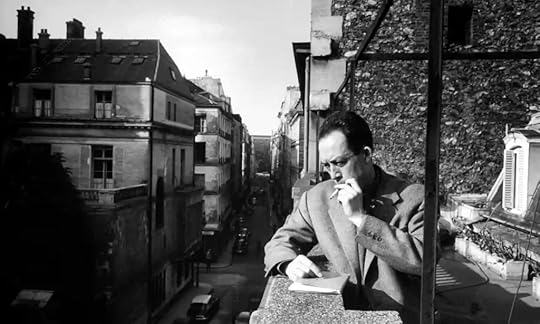

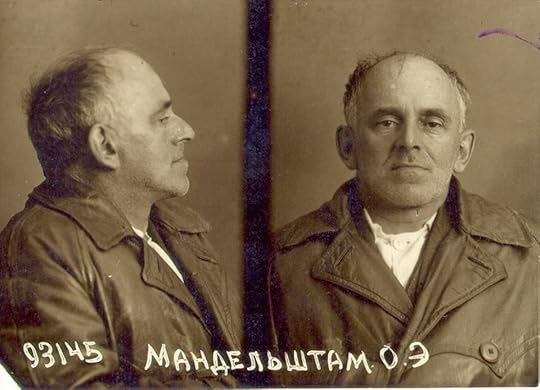

Sometimes there doesn’t even need to be a physical copy. Quite a few of the poems of the Soviet-era poet Osip Mandelstam exist and are read now because they were memorised by Nadezhda Mandelstam and Anna Akhmatova.

Osip Mandelstam

Osip Mandelstam

Nadezhda Mandelstam

Nadezhda Mandelstam

Anna Akhmatova

Anna AkhmatovaIf we go back to Homer and Ovid, we see the codification of an oral culture. This was something people could carry with them as they walked – just as people know by heart Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell songs, or raps by Kendrick Lamar, Missy Elliott, or a thousand other lyricists.

Medieval forms were portable.

Writing about Dante, Osip Mandelstam said:

The question occurs to me – and quite seriously – how many shoe soles, how many ox-hide soles, how many sandals Alighieri wore out in the course of his poetic work, wandering about on the goat paths of Italy.

The Inferno and especially the Purgatorio glorify the human gait, the measure and rhythm of walking, the foot and its shape. The step, linked to the breathing and saturated with thought: this Dante understands as the beginning of prosody.

Osip Mandelstam, Conversations about Dante, trans. Clarence Brown

I first read this on page 227 of Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines. This book, now seen as questionable, is based on a vision of the first people having sung the land into existence – and that those lines still existed in the lineaments of hill, billabong and apparently featureless plain.

Humans made it up; fragments of it continue to exist.

What will survive of us is portable.

Hope in a Darkened Heart

Obviously, as I said, the best way for this not to happen is for all of us to make sure this cannot happen. I don’t mean us individually; I mean us collectively, actively, politically.

All of us who, when we smell petrol, smell our childhoods.

Because when the only ones left defending the pure profit motive are gangsters, you have our situation.

There is hope, if we can gang up against the gangsters.

Being eco-friendly is not enough, in days like these.

If you want to be a writer in twenty years’ time, you need to make that writing sustaining and sustainable – in any way you understand those words.

This goes from spine, to chair, to desk, to laptop, to paper, to book, to art, to world.

It may be that if you want to be a writer in twenty years’ time, if you want anyone to be a writer in twenty years’ time, then you may need to be something other than a writer right now.

And if you don’t want to take it from me, take it from Margaret Atwood.

Further reading:

Jay Griffiths, Why Rebel, Penguin, 2021

Andreas Malm, How to Blow Up a Pipeline, Verso, 2021

April 22, 2022

A Writer’s Diary – Marz Q&A

The third Discussion Thread happened on Friday 25th March. It’s taken me a while to archive it here (very busy with Writers Rebel recently), but here it is.

The next one is imminent: April 29th.

Hello Grab-baggers,

I am very aware how the Diary might be reading right now – sticking to very small concerns, and making no mention of the war in Ukraine. However, I’ve decided to go ahead with it as planned.

Now we’ve reached (so soon) the last Friday of March, I’d like to invite you to join a discussion thread.

I’ll be here at 4pm, and this time we’re going to be talking about publishing, getting published, and – most specifically – publishing on Substack.

Any questions or suggestions you have, please sling them my way by commenting on this post.

The last couple of discussions have been extremely fun and interesting. I’ve archived them here and here.

Thank you for following the Diary. Your presence is transforming how I think about writing.

This week, I learned that A Writer’s Diary is in the Top 25 on Substack for Fiction.

All best,

Toby

Grace

Congrats! Number 25. An odd number, so very pleasing. Does your wife read your diary?

Dear Grace,

yes, which I can only assume means I was in at number 23. This was a fact I only discovered when I looked at the subscribe page, via a New Incognito Window (because I didn’t want to be taken straight to my admin page). As far as I know, there’s no chart or ratings in the public domain. Back when I was setting up the Substack, deciding whether or not to categorize the Diary as fiction or non-fiction had me hesitating for about a week. Maybe this is a sign I made the right choice.

But to answer your question – Leigh has read all of the Diary, everything that will appear this year, and although that wasn’t a comfortable experience, and brought up a lot of stuff, she was happy for it to go out into the world. I’ve written about us before, most of all in Ghost Story.

Hope to see you around soon.

All best,

Toby

Hi Toby – just wanted to say a massive thank you for A Writer’s Diary. It’s a daily delight delivered to my inbox. No mention of the war is a positive! No questions, just a thank you from a very appreciative reader.

Dear Gareth,

thank you. And thanks for writing.

I’m wary of offering escapism for escapism’s sake. There are other and more important things in the world than pencils – of this I’m in no doubt. However, writers of all sorts do have this desk-stuff confronting them all day long. It’s obstacle and relief.

I always envied painters the amount of time they could spend doing the physical business of brushes, palettes, glazes.

The loss of life is the most appalling thing, and the blazing aggression. But one of the other things the destruction of Eastern Ukraine has made me very aware of is the fragility of domestic space. How many ‘right places’ have been obliterated in the past month? ‘That’s where that mug hangs.’ ‘Grandfather always puts his slippers there.’ ‘The cat sleeps on the windowsill on the left.’ We are so powerfully reassured by these locations, which are gone in a second. It may be our lives that that go from them, or they that go from our lives. But those walking into exile are heading into spaces where there are, in the first few moments, or perhaps for years, no right places. That is one of the worst of the minor cruelties.

You didn’t ask for this, but it’s been on my mind.

All best,

Toby

Thanks for the reply Toby. I think I better understand what you originally meant, and some thought provoking reflections as to what people are going through in the Ukraine on a personal and domestic level.

I must admit this is not something that always springs to mind when people are losing their lives in such horrific fashion, but thinking about having your normal life ripped away must be one of the many indignities.

It wasn’t what I asked for, but it was what I needed!

Cheers,

Gareth

Hi Toby,

Publishing seem such a dangerous button to press. To push through the hesitation and utter words which cannot be unseen once on the page. As a non participant, I’m more interested in why someone decides to publish and why a particular work rather than how to. The integrity of placement.

On a different note, I was compelled to attempt your free writing and, with all rules removed, it’s not as easy as words on a page. Jabberlitty could be a a new form of expression, quick register it.

Further, I like the examination of minutiae. It calms me, lets me linger on images and sensations and sometimes form sentences as I drift off. And I’ve not done that in a long, long time.

It’s all good.

Chris

25 and hurtling skywards.

Dear Chris,

I’m pleased to hear it’s all good.

Why someone decides to publish is a difficult question. It’s sort of taken as a given, especially on writing Twitter and within Creative Writing programmes. It’s the reason lots of people post or pay the money for workshops and teaching. But publishing, as most published writers know, is a treacherous business. It does strange things to your sense of what you’re writing for.

I’m no longer sure what counts as ‘published’. When I began writing, I thought being published meant a large publishing company producing a physical book with your words inside that you hadn’t paid them to produce. Publishing was anything book-like that wasn’t vanity publishing. However, certainly at the beginning, my desire for this wasn’t without vanity. I wanted to be good enough to be published. But I didn’t doubt (or not very often) that I could get to be good enough, given the number of hours available to me in my forseeable life. I was prepared to do anything I needed to – junk any unnecessary parts of my personality – in order to get the large publishing company to love me. I didn’t questions what that ‘good enough’ might mean. (Perhaps I’m being a bit hard on my young self.)

Later on, publishing was something I felt I had to ignore – along with whatever successes it might bring – in order to do the writing better. If I was too preoccupied with strategising my next book, to achieve some particular new level, then I’d inevitably write worse. As a result, I did a kind of anti-strategising, and followed deadkidsongs with Finding Myself. That was not a move likely to please anyone. How could I escape my own preconceptions of myself in order to escape other people’s preconceptions of me? I still think that’s worthwhile, if only as an avoidance of ego-traps.

Why a particular work is an even more difficult question. I don’t think I can answer it. Works tend to be cuckoos in the nest; other treasured little speckled eggs tend to end up dropped onto the roots and go splat.

Jabberlitty is a fun idea. I think it’s yours, though.

Be assured, the minutiae will continue.

Thanks for those questions.

All best,

Toby

Perhaps knowing preconceptions are out there/ inside somewhere, is the first win. Publishing or not, everyone should take a writing class because the act of writing, rewriting and possibly learning from it, changes people in unexpected ways. Again all good. The appearance of your cuckoo strikes a cord and is the 3rd bird in my emails this week. Bird by Bird indeed.

Thank you for the diary and the time you give to your readers.

Chris

Feynman (Mr F.) now stretches in the coastal sun in the form of a large, old and adored black cat. He keeps company with bro Oppenheimer (Opi, also sage) and Bogard (cute but no respect for birds). These days the boys judge the world silently because there are no words.

Hi Toby,

Do you have the same reader in mind when you write the diary as opposed to a novel?

The Diary is almost like daily flash fiction.

Best, Ian

Dear Ian,

well, thanks to your retweets on Twitter, you (along with Saskia van der Linden on Facebook) are one of the readers I definitely know is out there waiting.

But, in the moment of writing, I don’t think I think of a reader. I have some vague scale of comprehensibility. Does this sentence make sense? Is it something I, or anyone I know of, has said before? Is it worth saying?