Peter M. Ball's Blog

September 17, 2025

Boost Your Fiction: The Power of Objects and Objectives

I spend a lot of time talking to writers about their work, whether it’s as an editor, a writing mentor, or someone who exchanges critiques with friends. Over the years, I’ve noticed that one of the most commonly used solutions I’ll offer when folks are stuck on a problem is simple:

What’s the object you can attach to this objective or goal?

Learning to use objects and objectives effectively in fiction is one of those tricks that really levelled up my writing, and it’s the thing we all overlook when in the messy process of creating a first draft.

Nine times out of ten, if a scene or story is feeling problematic or vague, it’s because the big picture goal or ambition is locked down, but there’s no way of confidently stating whether a character has achieved it.

Unfortunately, we read stories to see how characters solve problems. Having a clear sign that a problem is solved is one of the most useful things we can embed in our fiction.

OBJECTS MAKE THE ABSTRACT SPECIFICTransforming the abstract and intangible into the concrete and specific is a key skill for writers, and it manifests in different forms. It’s the same advice that lies at the heart of Chuck Palahniuk railing against the use of thought verbs, where he argues:

Your story will always be stronger if you just show the physical actions and details of your characters and allow your reader to do the thinking and knowing. And loving and hating. (Nuts and Bolts: “Thought” Verbs, Litreactor.com)

Similarly, objects can transform an ambiguous goal into something specific and tangible. Take, for example, a character whose long-term goal is “I want to be rich.”

Rich is a nebulous social construct, and it means different things to different people. There are people out there who believe that earning $100,000 a year is a fantastic income, and others who will decry that they earn that much and live paycheck to paycheck.

Ergo, the reader left pondering what “rich” means in this context: moving from poverty to a middle-class lifestyle? Becoming a titan of industry? Building an investment portfolio to rival Warren Buffett? Becoming your world’s equivalent of Tony Stark?

Even though your story will provide some context, the nature of wealth means there’s a sliding scale.

But look at what happens when we take that goal and attach it to a concrete action or object:

“Rich” means living in the $5 million mansion on top of McKinley Hill. The big, white-walled place that looks like a castle, which I used to stare at from the bedroom of my shitty shared bedroom as a kid.

“Rich” means having $10,000 in savings in the bank and enough money to send my kids on the trip to Disneyland they always wanted.

“Rich” means walking into the boardroom of my rival company after a final takeover and firing the board, particularly my hated father-in-law.

“Rich” means driving a cherry red Lamborghini to my fifteen-year high school reunion.

“Rich” means launching my experimental rocket, and funding a trip to Venus.

By attaching the goal to a physical thing, we immediately know what kind of rich the character is chasing, why it’s so important to them, and whether they’ve achieved it.

Does the character live in their mansion? No! Then the story isn’t over yet.

EVERYONE CAN INTERACT WITH AN OBJECTHere’s the other advantage of attaching goals and objectives to an object: everyone can interact with it. An idea is shared by everyone without changing, but an object can be moved from person to person, and the ownership of it can motivate the character and show their progress through the story.

It’s hard to argue that someone has stopped your character from getting rich, but if their arch-nemesis buys the mansion or a hacker steals the savings buffer they’ve worked so hard to build up… well, now that characters is going to be motivated.

When they have a specific vision of what rich means attached to the object, they’ll immediately want that object back.

Similarly, you can change the object to show how a character is growing and shaping over the story. Physical objects become metaphors as they change over the course of the story. Dent a character’s Lamborghini, and we know their self-esteem is damaged. Wreck it, and we know they’re on the verge of burning out (or they’re about to learn their goal was stupid, and chase after what they need instead of what they wanted).

This interactivity can also show a character’s evolution. Take Episode VI of Star Wars, for example, when the long-term goal of “Stopping the Empire” is attached to a physical object: a small, unprotected exhaust port vulnerable to torpedoes.

The rebellion throws everything they have at the exhaust port, but technology won’t get the job done. It takes Luke Skywalker rejecting technology (turning off his targeting computer – another object serving as a stand-in for the wrong path) and trusting in the Force to actually take down a Death Star.

In doing so, he actually becomes a Jedi, worthy of the object that’s attached to that goal (the lightsaber he received in the first act of the film).

(Star Wars is often a masterclass in using objects. Consider, for example, what the Millenium Falcon means to Han and Londo, or receiving his first X-Wing means to Luke. Also Princess Leia’s iconic hairdo, the chase after Death Star plans, and the way Darth Vader’s mask represents his character growth).

SHORT TERM OBJECTSThe examples above revolve around long-term objects and objectives, but often the fix to a scene that’s not working is figuring out the short-term object the character is chasing in the moment.

For example, an abstract goal like “to get married” can be made concrete by giving the character a suitor to pursue, which in turn suggests a series of short-term goals: get a date; make it through the date without embarrassing yourself; fending off the interest of the wrong guy; making big mistakes that may alienate your paramour; showing the object of your affections that your intentions are real after pissing them off.

Each of these can have an object attached. “Get a date” might mean “get the phone number” or “use these tickets to a theatre event to coax them into going out”. Success and failure are built in – do you have the phone number? Have they agreed to the date?

Similarly, great romance stories often attach the highs and lows of a relationship to objects or information that can be shared to destabilize a relationship (or stabilize it, in turn).

But this is not just a romance tactic. I would argue most scenes should have an object the character wants or an objective they’re trying to acquire, a short-term step on the path to the longer term goal. I often find myself distilling from goal to objective to object. For example:

“Find out who murdered my sister?” is a big, abstract goal.

“Get information from Detective Maury about my sister’s murder?” is an objective that might be at the heart of a scene – a small step towards that larger goal.

“Get Maury go give me my sister’s case file?” turns the objective into a concrete object the character is pursuing.

More importantly, attaching the objective to an object opens up tactics. If the investigator can’t convince Detective Maury to share the file or get access to it through the courts, they might break into the police station or hack the files or even smuggle the file out of the police station.

The genre and tone of the story will guide the exact actions, but the object gives us options. More importantly, it makes it clear when a scene is over, because the character has either taken possession of their object or been thwarted so badly they need to regroup and try another tactic.

OBJECTS AND STAKESThe flip side of a character’s goals are stakes – the things the character is afraid of losing, rather than the thing they’re chasing. My favourite method of figuring these comes from a workshop by Mary Robinette Kowal, who suggests thinking about the things that could happen that would really make your character feel like the worst person in the world.

The worst way to approach stakes is to treat them as the inverse of the character’s goal – if the character wants to be rich, then their stakes are not being poor. But once again, attaching these to objects can be incredibly useful.

For example, if our character chasing wealth would feel like shit if the antique watch he inherited from his grandfather was destroyed, then we immediately have an object that suggests what this character values.

The watch is a connection to family, and he feels value in protecting the one nice thing he was given as a child, and its destruction is meaningful to him.

Once again, attaching the character’s stake to an object makes it easy to motivate them and show where their character is at:

What happens if another character steals the watch?

What if the price of getting the home they always wanted is sacrificing the watch they love?

What does it mean if he shows another character the watch and tells them the story behind why it means so much?

What does it mean if he sacrifices the watch for another character’s goals?

OBJECTS MATTERAs writers, ambiguity is the enemy. We work in an in-exact art form where words suggest and shape, but never actually represent what we’re trying to describe. We manipulate and reshape the reader’s memory, and provide context to guide them towards the points and themes we’re trying to make.

There are very few problems in writing that aren’t improved by sitting down and asking how to incorporate meaningful objects into the scene, how to attach meaningful objects to the character, and how to transform goals and objectives into something tangible.

Done well, you can create metaphors and icons that last for generations. From lightsabers to Indiana Jones’ hat and whip, from the light on the end of a dock in West Egg to the myriad rings, swords, and Mithril shirts that dominate Lord of the Rings.

Objects matter to us, in stories and real life.

Deploy them at will to level up your writing.

The post Boost Your Fiction: The Power of Objects and Objectives appeared first on Peter M. Ball.

September 9, 2025

When The Algorithm Doesn’t Love You Anymore

Here’s a dirty secret I rarely say out loud as a writer: I don’t want you to friend me on Facebook.

I don’t want you to follow me on Threads or Twitter or Instagram. I sure as fuck don’t give a shit if you’re following me on TikTok.

I’m on all these places, and I’ll engage with you if they’re the only choice, but they’re not my primary focus.

As a writer, I’ve got three top tiers of engagement: I want you to subscribe to my newsletter. If that’s a no-go, the second-best choice is joining my Patreon. The third choice—just—is following my YouTube. Maybe, as a last resort, I’d taken a follow on BlueSky.

Why? Because everything listed in that first paragraph are increasingly algorithmically driven. A follow there is next to worthless to me, because the For You page or “content we think you’d like” has taken over the follower feed.

I’m interested in actual followers, who’ll hear from me regularly. Email is still an old-school follow. Patreon, for various reasons, is much the same. YouTube is algorithmic as hell these days, but at least has the Subscriptions section where you can get updates from folks directly.

And for a writer—heck, for any artist—an old-school follow is the most valuable thing there is.

I miss the old-school follow. I’d still be talking about Facebook et al. with affection if they still offered something like it.

But they don’t, even if so many writers still produce content for social media like it’s 2007.

THE MAGIC OF THE FOLLOWThe founder of Patreon, Jack Conte, spent much of 2024 giving speeches about the Death of the Follow and how it will affect creators who rely on the internet.

If you’re unfamiliar with his work, Conte is an interesting case study. Before he was the CEO of a tech platform, he was a musician who broke out on YouTube as both a solo artist and one half of Pomplamoose. If you were online in 2010, you probably encountered some of their covers (I’m still a big fan of their version of All The Single Ladies).

Conte is still a working musician on top of running Patreon, and he created Patreon to solve a problem he saw with the way YouTube was changing as the platform matured.

There’s two things writers and other creative artists typically want from social media:

We want to reach people who don’t know about us and tell them about our work.We want to build our following and keep talking to the people who like our work.Buttons that allowed users to follow or subscribe to us on social media, Conte argues, were the revolutionary part of Web 2.0. It allowed people who liked what we did to sign up and hear from us repeatedly. It gave writers, musicians, and other artists a distribution channel that ensured future work was sent to people most likely to be receptive to it.

“The follow is not some handy feature of a social network,” Conte says. “It’s foundational architecture for human creativity and organisation… Not just reach, but a step past it. Ongoing communication, connection, a sustained relationship. Community.” (Jack Conte, Death of the Follower: SXSW 2024 Keynote)

The Follow allowed small creators to reach a dedicated group of fans and build up their profile. It allowed books to succeed that wouldn’t otherwise.

I ran pretty hot on my author platform in that era and saw its effects first-hand: small press books that sold out print runs unexpectedly; ideas that went viral because they were shared and re-shared by people who enjoyed the way I thought and wrote.

But large chunks of the internet don’t work like that anymore.

I wish it did.

Because here’s the thing: The follow is magic for creators.

It’s not so good for social media platforms.

THE ERA OF RANKING AND ALGORITHMIC FEEDSThere’s a simplicity to the old-school follow: a user says, “I’d like to see more from this user,” and then they see more. Every post is displayed on the feed as it goes live, and they can track what their favourite creators (and their friends, and their loved ones, and their favourite burger place) are doing day to day.

Here’s the problem: most people aren’t that interesting twenty-four hours of the day. Or they’re not showing up and talking about the things you love all the time.

And social media needs to be interesting. It needs to reward you with stuff you absolutely want to engage with every time you log on, because the money in social media lies in having a large user base who shows up often, giving you data and reach that can be sold to advertisers.

Facebook started messing with the feed around 2009 to 2012, moving away from a solid timeline and towards an algorithmic feed. They’d survey all the posts made by folks you followed, and feed you the ones that were getting the most engagement and interest from other people. Stuff nobody engaged with was more likely to get hidden.

Instantly, a follow became less useful. Largely because, in those nascent days of the internet, stuff that got engagement was often realising a chunk of your friends group were not who you thought (2013 was the peak era of friends engaging in comment-fights with the vague acquaintances whose racism and sexism was exposed).

Over time, Facebook got good at showing you folks you weren’t following, who were still interesting. Then it got good at showing you paid ads that held your attention and kept you on the platform. Soon you could idle away whole days engaging with vaguely interesting stuff that tapped into a part of your identity and fed it.

That shit was insidious, but effective. Great for Facebook. Less great for us.

A few years after that, we had TikTok, which disposed of the follower feed altogether. The default there became pure algorithm—the For You page—where a constant stream of stuff you’re probably interested in rolls past in a series of six seconds videos.

And because algorithmic feeds worked, everyone adopted them. Facebook’s innovation begat similar tools on Twitter and Instagram and Threads. Suddenly, you had to pay to reach your followers, or feed a steady stream of high-engagement content into your social media.

And here’s the thing about the algorithm: it favours a small percentage of creators who reliably get traction with posts. It randomly gives attention on another subset of creators, based upon the needs of the algorithm. As Cory Doctrow notes in his essay on the Enshittification of TikTok, the platform will often artificially inflate the presence of a new users’ videos on the For You page to convince them of the platform’s value.

Then, shit goes wrong.

Once those performers and media companies are hooked, the next phase will begin: TikTok will withdraw the “heating” that sticks their videos in front of people who never heard of them and haven’t asked to see their videos. TikTok is performing a delicate dance here: There’s only so much enshittification they can visit upon their users’ feeds, and TikTok has lots of other performers they want to give giant teddy-bears to.

Tiktok won’t just starve performers of the “free” attention by depreferencing them in the algorithm, it will actively punish them by failing to deliver their videos to the users who subscribed to them. After all, every time TikTok shows you a video you asked to see, it loses a chance to show you a video it wants you to see, because your attention is a giant teddy-bear it can give away to a performer it is wooing. (The ‘Enshittification’ of TikTok, Cory Doctrow)

From there, you enter a cycle. Random bursts of attention to make it feel like the algorithm is favouring you, followed by long stretches where your reach is throttled to entice users into coughing up cash.

WHAT’S THE ACTUAL BENEFIT HERE?Here’s my problem with the current state of social media: writers and other artists still treat it like an old-school follower platform. I’m certainly guilty of it, spending days creating month-long posting schedules to maximize the reach of my content and try to prompt engagement.

And, as ever, the problem isn’t that social media has no benefit. The fluctuating algorithmic reach is still potentially useful and can feed readers towards work. It allows you to cultivate fans over time, especially the small subset of followers who actively show up and engage with everything you post.

I’m not saying get the hell off social media, just because it’s algorithmic.

I simply started thinking about the return on investment with regard to that time, and how I could maximize it.

I want to loop back to the two goals writers typically have with social media use, mentioned at the start of this entry:

We want to reach people who aren’t familiar with our work.We want to build our following and talk to people who like our work.Algorithmic social media is terrible at building a following and connecting you with your followers, but it has an upside: a For You page or algorithmic feed is very good at putting your content in front of people who might be interested in your work.

That has a benefit to us as writers, especially in the early days of a platform before the enshittification has really set in. TikTok in 2020 was an incredible lead generation tool, just as Facebook was in its earlier days.

My concern isn’t that it can’t do these things, but that it can’t do these things as effectively as other options.

As noted back when I looked at the capital exchanges inherent in social media, it makes more sense to run adds or use lead-generation tools like newsletter swaps that feed potential readers into a tool where they can still follow me (like a newsletter) than it does to spend six to eight hours generating posts to do the same job organically.

YOUR NEW MINDSET: DE-PLATFORM LIKE A MOTHERFUCKERI spend a lot of time listening to other authors talk about how they use social media, and as someone who mentors other writers a lot, I spend a lot of time doing courses about how to maximize engagement on platforms and use it to drive readership.

I think it’s important to understand these platforms and use them; I just think we need to engage with a different goal. To borrow a phrase from social media guru Justin Welsh:

Social media is one of the best to master because you can gain attention and then slowly de-platform prospects and customers to something you own – like an email list. (Why People Fail On Social Media, JustinWelsh.me)

If I’m showing up on a social media platform in a professional capacity as a writer or publisher, this is pretty much my goal. I want to get people to leave Facebook or Threads or Instagram, and go to a platform where the Old School Follow is still in effect.

A place where I can clear away the noise of a thousand other posts and the clatter of algorithmic distractions, and talk to readers who actively say, “yes, talk to me more about this thing we’re both interested in.”

Email lists are old-school tech, and so clunky that lots of people devalue them or outsource their creation to “free” services like Substack, but the truth is they’re the most effective follow-based tools writers have these days (and, in terms of data they can generate, even more effective when you learn to use them well).

Every writer finds their own way of doing this. Some use ads to drive people to free reader magnets—and I certainly do a lot of that. I’m also putting a lot more writing up on blogs, creating hubs where I can capture followers (newsletters, Patreon) and use engagement on social media as tendrils that reach out and snare potential readers like kraken plucking sailors off the deck of a ship.

It’s slow and steady work, but ultimately less disheartening than fighting the algorithm for each new release. 100 followers who engage with you regularly often prove to be far more valuable than a thousand follows on a social media site where you need likes and reposts to find other people.

This post appears courtesy of the fine folks who back my Patreon, chipping in a few bucks every month to give me time to write about interesting things. If you feel like supporting the creation of new blog posts — and getting to read content a few weeks ahead of everyone else — then please head to my Patreon Page.

If you liked this post and want to show your appreciation with a one-off donation, you can also throw a coin to your blogger via payal.

All support is appreciated, but not expected. Thank you all for reading!

The post When The Algorithm Doesn’t Love You Anymore appeared first on Peter M. Ball.

September 3, 2025

Preserving Great Writing Advice From Internet Decay

The post Preserving Great Writing Advice From Internet Decay appeared first on Peter M. Ball.

August 14, 2025

The Most Valuable Page Of Notes I’ve Ever Written

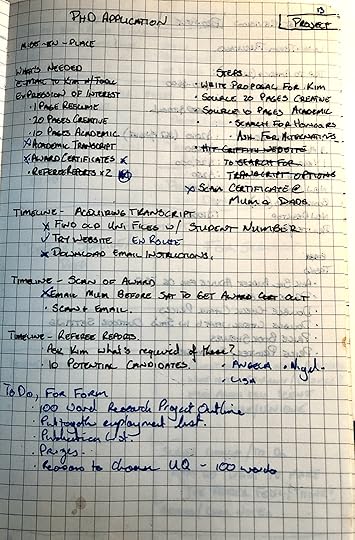

I’ve been re-reading old bullet journal this morning and found this page, from 2016, which led to the most important writing gig I’ve ever had:

I produced this on my friend Meg’s back deck, trying to sort through the complicated steps required to apply for a PhD and break them into tangible, completable steps. I basically broke down everything I had to do–and especially the things I didn’t know how to do–and laid things out.

I wrote this on the 29th of August, 2016.

By January of 2017 I was in the program, on scholarship, producing three short books (White Harbor War, On Writing Series, and the yet-to-be-released Cerberus Station Rumble). For three and a bit years, the university paid my bills and I got to sit and think and write.

Back in February I wrote a blog post about the things writers and publishers can learn when comparing the CIA’s Practical Timelines for culinary students to traditional recipe formats. The Practical Timeline essentially breaks down what we think of as a “recipe” into four categories of information:

What ingredients do we need?What tools do we need?When needs to be done?When does it need to be completed?The page above was the first time I applied that thinking to a complicated project with a bunch of small, daunting steps that could have derailed me. This single page plan basically worked thorugh five layers of questions:

What do I need to gather together for the applicatoion?What do I need to do?What do I need to find out?What are the smaller tasks?When order do I need to do things?I doubt I’ll ever write anything that pays me as well as the years I spent on a PhD scholarship, and one might think that’s what makes this page valuable.

And you’re partially right. But I’m looking at it for another reason.

NOTEBOOKS MAKE PROCESS VISIBLEI’ve been thiking about this page a lot this week, as I recently asked one of my mentees to consider working in a notebook for a stretch. They’re very much an at-the-keyboard kind of writer, and normally I’d roll with that, but they’ve hit a period of feeling disconnected from a project.

I usually advise a short stint of writing in notebooks for a few reasons. First, because filling a page is more tangible than typing 250 words, particualrly in the era where word processes infinitately scroll and add new pages as each one is filled.

Second, because making writing tactile is often distracting enough to shut up that little perfectionist voice that wants to focus on why things are bad. And writing in a notebook is, tangibly, not a finished draft. It frees you up to make mistakes.

But the third reason–and the most significant, for me–is that notebooks make processes visible. When we write on a computer it’s easy to write and rewrite and lose track of how things iterate and develop.

We don’t get a sense of whether we write good lines on the first draft, or come up with them as part of a process. Our creative thinking tends to disappear because it’s hard to go back and see what was after you’ve made a change.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with that, but there are times where it’s incredibly useful to be able to see how something developed. Looking back at my 2016 notebook, I’m actually surprised by how much pre-work I was doing on the page.

I’ve got about twelve years of journals showing how I work. They don’t always have a complete picture–my focus on a bullet journal waxes and wanes, depending on what else is going on–but it’s enough to see patterns and the relationship between periods and how strings of “bad” weeks often lead to work I’m incredibly proud of in retrospect.

This post appears courtesy of the fine folks who back my Patreon, chipping in a few bucks every month to give me time to write about interesting things. If you feel like supporting the creation of new blog posts — and getting to read content a few weeks ahead of everyone else — then please head to my Patreon Page.

If you liked this post and want to show your appreciation with a one-off donation, you can also throw a coin to your blogger via payal.

All support is appreciated, but not expected. Thank you all for reading!

The post The Most Valuable Page Of Notes I’ve Ever Written appeared first on Peter M. Ball.

August 4, 2025

The Theory Of Constraints

The theory of constraints is a business management philosophy popularised in Eli Goldratt’s 1984 book, The Goal, although it builds upon work by earlier thinkers, including Germany’s Wolfgang Mewes.

These days, The Goal is better known as a book Jimmy Donaldson—aka MrBeast—used to make all his employees read and assimilate.

Now let’s be clear: I don’t really get Mr Beast, nor like him. I think his whole schtick is emblematic of a fundamental problem with algorithmic social media, and I’m vaguely baffled he’s a millionaire or famous. I sure as fuck don’t know how he has a line of snacks, let alone an Amazon show.

Which means I’m not interested in the content he produces, but I’m oddly fascinated by articles and insights into how Mr Beast came to grace our YouTube streams. He’s emblematic of a shift in the marketplace, and I like to understand those for my own good as someone who makes a living on creative work.

Similarly, The Goal is not a good book. It engages in a particular rhetorical cheat beloved of business books, articulated by Sci Fi author John Scalzi as “confirming the usefulness of the book by creating characters that are helped by its philosophy, but which don’t actually exist in the real world”. (Stinky Cheese) Suffice to say, there’s a reason I’m linking to many references here, but not that one.

The theory of constraints is also an argument for the “just in time” model of business infrastructure, which was exposed as a enormous problem during the recent pandemic. It’s great for maximising profits, but terrible for withstanding shocks to the infrastructure and black-swan disruption events.

On the other hand, when used as a guideline, there are some useful ideas in Goldratt’s book. Starting with a simple question: what’s currently stopping you from putting out books at the speed you need?

Goldratt argues there’s three key types of constraints on any process: the limits of the equipment used, the skill set of the people involved, and written and unwritten policy assumptions that prevent a system from operating at capacity.

The key to levelling up a business is identifying those constraints, coordinating the rest of the system to work at the limits of the biggest bottlenecks, and then slowly elevating everything by improving equipment, skill sets, or policies.

Infrastructure BottlenecksGoldratt’s book is built around the management of industrial production processes with a lot of moving parts and people involved. It doesn’t feel like a natural fit for a small press publisher with a single person handling much of the workload, nor a writer who is essentially a one-person fiction factory.

As I’ve mentioned a few times now, a writer’s infrastructure requirements are light. There’s not much to refine and level up there, even if there are a handful of technological innovations (online submissions, easily accessible ebook production tools and distribution, the bookfunnel app) which lead to quiet revolutions in how we produce and distribute work.

Still, the theory of constraints has helped make a bunch of decisions around my recent infrastructure changes. It encouraged me to sit down and look at the biggest bottlenecks when putting out Brian Jar Press books and selling them at the quantity we needed.

And trust me, there were many. The website wasn’t operating at peak capacity. I wasn’t drawing in enough new readers and operating them in the right way. I was spending a lot of money to replicate the same two systems.

All stuff that I’ve talked about improving over the last few weeks.

But that was looking at the tech stack — the equipment.

The rest of the process was looking at the other two potential bottlenecks: the people and the policy/system assumptions.

Or, given that I’m the sole employee of both Brain Jar Press and GenrePunk Books: where in the process do books get derailed?

There’s obviously a long list of possibilities here, but here’s the short-list I identified:

Line and copy edits, particularly when it’s another author’s book instead of my own.

Writing emails to people I don’t know well enough to predict their response, particularly when asking for a favour or communicating when we’re behind.

Mailing out pre-release review copies for blurbs and review.

Managing cash flow, especially during leaner months when there are no new releases or constant outreach to bolster the direct sales store.

One of these, I knew about. If Brain Jar Press books sold enough copies to justify outsourcing copyedits and line edits to a reliable editor, our release schedule would probably triple in the space of a few months.

I’d call copyedits my personal bugbear; the perfect storm of a task that doesn’t play to my strengths, triggers my social anxiety hard, and is important enough that I’m cautious about who I trust with it.

We had someone who was the right mix of reliable, trusted, and affordable, but they were lured back to full-time work in a job they love. And while I have a series of great line editors I’d like to work with, but they know what they’re worth and charge accordingly. They’re a long-term solution for speeding things up if circumstances change (either we sell more books, or I get a part-time gig), but I need another plan in the short-term.

So there were some decisions to be made in the short-term, that will ultimately help.

The other two… well, they also led me to an immediate step I could take that might level things up: focus on mental health.

The Grinding Gears of Executive FunctionLet’s be really clear about something: I haven’t been making all these infrastructure changes because things are going right behind the scenes. They’re very much a response to alarm bells blaring and oxygen leaking out of the hull.

I try to put a cheerful varnish on things when I post about them. Often, when things are bad, I won’t talk about them until months after the immediate emergency is past.

Narratives build up around writers and publishers. Stories we tell ourselves, and stories other people tell about us. Even when you’re in a bad place, and help would be worthwhile, it can be professionally tricky to say, “Everything is a little shit right now.”

As Kameron Hurley noted, way back in 2015:

I’ve heard from a lot of writers (including the late Jay Lake) about how people stopped offering them opportunities on the assumption that they were unable or would be unwilling to tackle them. I didn’t want people to count me out, but I had to wait until I knew I was already better before noting that, you know, back in July I was a fucking nut and yeah, no, it just kept getting worse. This summer was pretty bad. (Why I Chose To Write Publicly About Anxiety)

Similarly, the last thing any publisher wants is an emerging narrative suggesting that they aren’t in good shape, undermining the confidence of readers and authors alike.

This is compounded by the trickiness of explaining business to folks who don’t run businesses. Brain Jar Press books, for example, are profitable enterprises. In the eight years since launching my publishing efforts, I’ve produced exactly one book that hasn’t made a profit.

But those profits can take a while to manifest, especially because we’re not built to sell books at the same velocity as other publishing houses. That’s why an understanding of asynchronous income and profit is useful when you’re getting into publishing.

Every book makes a profit, but that doesn’t mean your expenses get covered straight away. Try to grow too fast, spend too much on a project whose initial sales aren’t as strong as you’d hoped, and you’ll end up with more money going out than you’re bringing in.

Given time, that will even out.

But time isn’t always an asset you can leverage. It’s been one of Brain Jar’s strengths for the last eight years, but it stopped being one around the end of March, and things got…harder.

My spouse had been dropping hints they were concerned about my mental health towards the end of last year, and I started talking to my doctor about it back in January. Then the chaos of 2025 started, and the inertia set in. Following up kept getting pushed to the back of the to-do list, after fixing holes in walls and wisdom teeth removal and cyclone prep and more damage to our home.

Which meant it was six months before I finally got around to follow-up and taking actual steps.

And, as always, I’d forgotten what it was like to actually address mental health trickiness instead of just enduring it. It’s like swapping from an old junker of a car with grinding gears to a brand-new loaner that actually turns the corners without protest. I can decide about what to focus on without that feeling like I’m trying to redirect the fucking Titanic before it hits an iceberg.

I’m just moving past the “early days of this antidepressant will come with side-effects” phase, but I’ve still submitted my first new short story since 2023 (and have now got three stories out on submission for the first time since 2013). My spouse got frustrated with me as we got ready for work, and I didn’t spend the next four hours going over the minutiae of that conversation and mentally preparing myself for the worst.

I started thinking of how to get ahead on books I’m behind on, and didn’t want to lie down on the couch and panic.

You’d think I’d be prepared for this shift, since it’s been a repeating pattern once I found an antidepressant that worked, but mental health is a tricky thing.

What’s The One Thing?One of the more interesting variations on Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints is Keller and Papasan’s business book The One Thing, which suggests approaching your to-do list and goals with a simple question:

What’s the one thing I can do such that by doing it everything else will become easier or necessary?

The phrasing here is… well, horrible… but the intention is surprisingly useful. Getting into the habit of asking that takes time and effort, but ultimately pays off.

Here’s the thing about problems, particularly when you’re worn down or burning out: we get stuck on a solution or a process, and stop considering alternatives. There’s a natural tendency to assume that if we keep doing the same things, but do them harder, it will somehow work.

And that’s not always the best solution.

Sometimes you need to step back and identify the real problem. The one thing that—if you do it—speeds up everything else.

I’ve used this in many ways in the past. Back in 2023, I used this philosophy to get unstuck on a story I was writing. After getting stuck on a particular scene, I stepped back and created a big list of the details I needed that weren’t coming as I was writing. Doing that one list made everything easier, and I finished the story in a few hours.

In business, it’s useful for clarity. For months, I’d been bemoaning the fact I couldn’t bring on board paid copyeditors and start getting things moving. Everything became focused on the same problem and solution cycle: earn more money to bring on copyeditors so I can earn more money.

And it wasn’t working, because cash flow had been up in the air for a few months. And because I was using a solution from another time, and kept thinking about trying to do more.

The trick of Keller and Papasan’s approach is simple: you don’t decide on the one thing. You make a list of the possibilities, then refine it down to the one thing that will actually help.

It’s a small thing, but the shift in perspective is useful.

The Slow Level UpThese days, I’m working on doing less. Slowing production to the speed that I’m capable of, making time to diversify the income streams a little. Three books that come out on schedule are, after all, more valuable than six books I struggle to get out and another six I’m too burnt out to do.

Similarly, I’m fixing one bottleneck at a time. An assortment of things emerged when I created a spread of potential solutions, instead of focusing on the editorial blockage.

Right now, it’s easing the anxiety and getting back to a more even keel.

Then, it’s fixing the cash flow and rebuilding financial reserves under the “new normal” of our working lives.

This is a slower process than the therapy and medication, since there’s a bunch of small debts to clear after one or two projects didn’t hit targets over the last two years. I also have a “year ahead” target that needs to be met, so the expenses for the coming twelve months are covered.

This one is frankly going to be hard. It’s going to involve prioritizing projects differently, and focusing on a combination of what’s easy to release and what’s offering the greatest short-term return (this is, somewhat, related to the fact I’m writing short fiction and submitting it again; also my return to Patreon. Drop me a comment if you’d like me to talk through this logic in a future post).

Then I’m going to focus on building up Brain Jar’s customer base (one reason I recombined the Brian Jar and GenrePunk stores, since I have a lot of easy ways to draw people to the store by giving fiction away when it’s mine).

This is the next step because there’s an ideal sales target (about 250 copies) that makes bringing on board a paid copyeditor a feasible thing for me. Some of our books do that within a year, but not all of them.

The whole business changes once I can do 250 sales for a new release in the first twelve months.

Only then will I try to fix what I regarded as the “key” thing to fix and start outsourcing parts of the editorial process.

It’s a slow process of leveling up. It will be incremental gains that take time. But it’s the most feasible one I’ve come up with after thinking about this for a while, and the first plan where the next steps are relatively clear.

Logjams and One ThingMy focus in this piece is the business side of things, but you can apply this to almost everything in writing and publishing.

On the writing front, for example, I can produce drafts at great speed. I wrote a whole damn novel in three weeks back in June, just to clear my head, but that’s not the same thing as producing a book (rewriting is my logjam there. Any release schedule I imagine needs to fall in line behind how fast I revise books, rather than produce drafts).

When I work with clients who get stuck, unravelling their work is often a similar process. What’s the thing that’s blocking this draft? What’s the list of things that may make solving that logjam easier, and which feels like the right one?

We get so locked into the one problem, one solution mindset that it’s hard to step back and diversify our thinking, but it almost always makes things a hell of a lot easier.

This post appears courtesy of the fine folks who back my Patreon, chipping in a few bucks every month to give me time to write about interesting things. If you feel like supporting the creation of new blog posts — and getting to read content a few weeks ahead of everyone else — then please head to my Patreon Page.

If you liked this post and want to show your appreciation with a one-off donation, you can also throw a coin to your blogger via payal.

All support is appreciated, but not expected. Thank you all for reading!

The post The Theory Of Constraints appeared first on Peter M. Ball.

July 21, 2025

On Heinlein’s Habits & The Rise of the New Pulp Era: An Essay

I spend a good chunk of yesterday incredibly bummed out I hadn’t got this essay finished before the end of August, not least because I’d talked myself back into running a monthly fiction-and-essay zine on the basis of actually hitting personal deadlines again. Then a colleague helpfully pointed out August had 31 days, so I still had time to do the last minute edits and referencing by the end of the month.

This is a chunky slice of wordage — around 4,500 words — which can be unwieldy for online reading. If you’d like an alternate format, you can grab it in ebook form here because this month’s mini-collection has official mutated into Eclectic Projects Issue 001, scheduled to drop for the rest of the world next year.

On Heinlein’s Habits & The Rise of the New Pulp Era

SECRET ORIGINS

I first learned Heinlein’s Rules for Writing while at Clarion South in the Australian summer of 2007, holed up in the Griffith University campus with seventeen other speculative fiction hopefuls for six weeks spent critiquing and learning our craft under the watchful eye of established SF professionals.

At the time I’d written semi-professionally for over a decade, publishing poetry and RPG materials while making slow to negligent progress on my creative writing PhD. I could string words together in a pretty row, but time spent in academia does precious little to give writers a toolkit for writing more than you research. I went into Clarion confident I knew how to produce a story, but eager to learn how to be a writer, and soaked up all the business advice I could get.

Our crash-course in Heinlein’s rules came via the Western Australia writer Lee Battersby in the second week, and they remain the single most important lesson I learned in my Clarion tenure. Applying them—along with a market list with editors open to submissions—changed my career trajectory and netted overseas publications in an era when such things felt new and strange for an Australian author.

The application of Heinlein’s rules earned me more money and kudos in the next eighteen months than a decade of writing had earned me prior.

To make my subtext plain: the adoption of Heinlein’s rules proved significant for me and transformed my relationship with writing. I doubt I’d still do what I do without them.

And yet I come to bury Heinlein Rules, not to praise them.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Like many contemporary writers, I learned Heinlein’s rules from a mentor or friend rather than the primary source. The five steps laid out as a simple system to follow if pursuing publication. Even though Heinlein’s himself declined to call them ‘rules’—he preferred the ‘business habits’—countless adherents use the term in workshops, blog posts, and books. High-profile authors (including Dean Wesley Smith and Robert J. Sawyer) and excitable new writers alike advocate for ‘the rules’ with vociferous enthusiasm, and you’re almost certainly familiar with some variation.

For those who’ve never encountered Heinlein’s advice before, I lay all five out in brief below. Heinlein believed a writer must do these five things in order to forge a career as a fiction writer:

1. You must write.

2. You must finish what you start.

3. You must refrain from rewriting except to editorial order.

4. You must put it on the market.

5. You must keep it on the market until sold.

Modern adherent will often add a sixth rule to the end — you must start the next thing — but the gist remains intact. It’s easy to see why these habits are so popular — they’re simple and logical, custom-built for repetition and easy recitation from memory. Over time, they’ve taken on a mythic quality, wisdom handed down from the venerable master of speculative fiction’s pulp era. A Rosetta stone to change a writer’s fortunes.

In truth, when we go back to primary sources, they’re a throwaway at the tail of Heinlein’s essay ‘On The Writing Of Speculative Fiction’ in Lloyd Arthur Eshbach’s 1947 essay anthology Of Worlds Beyond. A practical suggestion appended to a longer essay about Heinlein’s theory of science fiction, offered as a sop to Heinlein’s conscience after headier thoughts about the genre.

To understand the mythology around Heinlein’s habits, consider the iterative ways Heinlein’s rules expand in repetition: Heinlein lays out his practices and provides contextual detail in 261 words. Robert J. Sawyer’s essay on the rules, written in 1996, weighs in at approximately 1,200 words. Dean Wesley Smith’s 2016 book, Heinlein’s Rules: 5 Simple Business Rules For Writing, delivers the same information across 12,000 words. Both Sawyer and Smith cleave to the same five rules, with “start the next thing” appended as a sixth rule, but neither offer additional context and explanation.

To my knowledge, neither quotes Heinlein’s final statement on the business habits:

“… if you will follow them, it matters not how you write, you will find some editor somewhere, sometime, so unwary or so desperate for copy as to buy the worst old dog you, or I, or anybody else, can throw at him.”

(Heinlein LOC 178)

KNOW YOUR PRODUCT

Many people believe the independent publishing movement has sparked a new pulp era, with authors free to replicate their pulp forebears’ successes with constant production and release on an sped up schedule traditional publishers abandoned decades before.

Before I quibble with this assertion, let’s take a trip back in time. The first American pulp magazine — the revamped Argosy, launched in 1896–set the format. A thick magazine with 135,000 words of content: 7 inches by 10 inches, approximately 128 pages, filled with lurid and disposable genre tales grouped together by type. Printed on wood-pulp paper with ragged edges, their production values distinguish them from the ‘slick’ magazines with better printers and paper quality. While the slicks sold ads to make a buck, a pulp magazine’s production quality didn’t lend itself to reproducing art or graphics. Their profits lived and died in their ability to lure back readers who loved their genre niche.

In the late nineteen thirties, the pulps dominated the entertainment market, with some estimates suggest there were over 1,000 titles in production at once (some short-lived, others not). Not all pulps published science fiction—pulp aficionados will be familiar with the myriad genres covered by pulp magazines—but even so, the landscape provided markets hungry for stories to fill their page count.

This market Robert Heinlein published in shaped his business principles, but it was already in a state of decline as he laid out his business habits in 1947. The pulps battled paper shortages caused by World War II and the steady increase in competition from new mediums such as radio and television heading into the 1950s, and they would lose that fight. Within ten years, the primary pulp distributor, American Magazine Publisher, liquidated and marked the death knell of the format.

Some pulp those writers carried on, writing for the advertising-supported slicks, which demanded a different type (and, frequently, higher “quality”) story than their pulp siblings. Other pulp writers ceased production of short stories and wrote longer paperbacks1, while others moved on to television

And some faded into obscurity, unable to transition to a new model when the familiar, hungry pool of editors desperate for copy ceased to exist.

CH-CH-CH-CHANGES

The market for speculative fiction didn’t go away with the demise of the pulp magazines, but it changed and left some writers less than pleased with the transition. Authors who once supported themselves and their families with short fiction now found themselves focused on longer works for much the same money.

Writers who wax poetic about Heinlein’s rules often leave out contextual details. When arguing ebook publishing represents a new, neo-pulp era, where self-published authors with a love of genre fiction and the capacity to write fast can forge a living, there’s often a failure to reconcile Heinlein’s rules with the logic governing the contemporary marketplace.

It also overlooks the other useful insight to be drawn from visiting Heinlein’s advice in the original format: Eshbach included Heinlein, and nominated his essay as the first in the collection, because:

“… he is the first of the popular science fiction writers to sell science fiction consistently to the “slicks”. Others will follow his lead; and it may well be that this brief article will be the spark that will fire the creative urge in other writers, who will aim for—and hit—the big pay, general fiction magazines.”

(Eshbach LOC 75)

Ergo, when repeating Heinlein’s rules in a contemporary audience, we present two points worthy of acknowledgement. First, they are business habits tied to a particular era with different market logic.

Second, it’s a strategy employed by a writer with a surfeit of talent, luck, or good timing, which allowed him to achieve notably exceptional success rather than a success typical writer of his era, and this too may influence a contemporary writer’s ability to replicate his results.

THE CULTURAL LOGIC OF THE CONTEMPORARY MARKET

My adoption of Heinlein’s rules as a short fiction writer in 2007 led to a level of success, but it didn’t allow me to forge a full-time career as a writer. The short story market wasn’t large enough, and editors were now spoiled for choice rather than hurting for copy. Any attempt to sustain Heinlein’s business model through short stories alone would be impractical, if not outright impossible. Traditional publishing avenues required longer works, with stiffer competition, and even those books saw less demand thanks to television, film, and the internet. The world simply required fewer fiction works than it did when Heinlein transitioned from short fiction to novels.

It seemed the editors desperate for content were no longer editors, but television executives tasked with filling hundreds of channels with content twenty-four seven. Fiction writers would never again have the same marketplace for their work Heinlein wrote into back in 1947, and their approaches adapted to the times.

Then Amazon launched the first Kindle to the public on November 19, 2017, and the game changed in an instant.

Ebooks existed prior to the Kindle’s launch, but a major player unleashing an e-reader as a loss leader changed the game. The Kindle created a new audience for fiction—an audience hungry for books to read on their new devices, ready to embrace content in formats and genres traditional publishing either underserved or ignored altogether. For the next four years, independent publishing boomed with all the fervour of a Wild West gold rush. Those who could feed the market at speed earned themselves a full-time career, if not a fortune.

I don’t blame anyone who saw a new pulp era here. For a few brief, shining years Heinlein’s rules made perfect sense again: write fast, put the work to market, and readers desperate for content would pay you for your writing. The first wave of kindle millionaires emerged from writers who fit one of two archetypes:

• Authors with a deep backlist they could publish, composed of either out-of-print work from their traditional career or simply work the traditional market wasn’t interested in; or,

• Authors who could write and publish fast, establishing a deep backlist at speed.

It’s easy to see how Heinlein’s rules enjoyed new relevancy around this time, and why the general tenor of writing conversations online turned to questions of speed and quantity. Rachel Aaron’s seminal 2k to 10k post became a lighting post in 2011, with a book of the same name released soon after. Scores of self-published authors followed suit, cycling through all manner of advice for rapid production of words, from pomodoro cycles to writing sprints to dogged persistence and long hours to tools such as dictation.

What new pulp era advocates and writers who focus on speed often overlook is the difference between the hungry market Heinlein sold into and the contemporary ebook market, including the biggest and most significant: pulp magazines proved a temporary format, published on degradable, low-quality paper with a comparatively short shelf-life. Even the pulp paperback market, which picked up after the magazines folded build around the assumption books would sell for a limited of time, each release quickly replaced on store shelves and racks, because the cost to warehouse back list titles frequently outstrips the potential profit.

Ebooks, on the other hand, exist in infinite stores without physical limitations. Every work you produce—in theory, and often practice—is available for as long as there are folks willing to host the files and profit from it. Rather than competing with the other works released that moth, you’re competing with all the back list works published and kept in digital ‘print’ by stakeholders across the publishing landscape.

As the costs of creating such works wane, the wealth of available works expands, and the poetics of fiction adjust. Factor in print on demand, which removes the burden of warehousing from print books, and the same is increasingly true on the physical side of the industry as well.2

The market hungry for ebooks after the Kindle launched quickly became spoiled for choice. Backlist sales—once the domain of best-sellers and cult hits—are now a part of every sane author’s business strategy.

This, too, changes the game in ways that intrigue me. You can still write and publish at the speed of a pulp author—and even earn a few bucks along the way—but the cultural logic of the contemporary marketplace doesn’t favour the tactic.

Contemporary pulp writers don’t seek editors desperate for copy, but niche audiences who feel under-served by the existing markets (or dedicated fans who crave more from a specific writer rather than a specific genre, but they take time to build).

In the here and now, the challenge is not selling your work to an editor, but finding and keeping an audience.

CUTTING YOUR FUTURE INCOME

Back in 2009, venerable SF writer Robert Silverberg wrote an entry in SF Signal’s Mind Meld blog about the best writing advice he’d ever received. The advice came in the early part of his career, around 1957 — just ten years removed from Heinlein’s essay — when Silverberg forged a career via the rapid production of the solid-but-conventional 5,000 word stories needed to fill magazine pages in his era. To the young Silverberg, it seemed a safer bet to produce the “competent potboilers” editors found it easy to say yes too, but neither stretched him as a writer or showed any real ambition. In effect, he wrote in accordance with Heinlein’s advice, producing work fast and lean, then finding an editor hungry for copy.

This approach lasted until the magazine editor Lester Del Ray gave Silverberg some advice:

(Lester) pointed out to me that I was working from a false premise. “Even if all you’re concerned with is making money,” he said, “you’re going about it the wrong way. You’re knocking out penny-a-word stories as fast as you can, and, sure, you’re pulling in the quick bucks very nicely. But you’re shortchanging yourself, because all that you’ll ever make from what you’re writing now is the check you get for it today. Those stories will die the day they’re published. They won’t get into anthologies and won’t be bought for translation and nobody will want you to put together a collection of them. Whereas if you were writing at the level that I know you’re capable of, you’d be creating a body of work that will go on bringing in money for the rest of your life. So by going for the easy money you’re actually cutting your future income.

(Silverberg 2007)

Silverberg hesitated to push himself, as his experience showed his ambitious projects never sold as easily as the potboilers, but Del Ray argued this would be a temporary phenomenon. Eventually Silverberg did as advised, and the approach transformed his career. He won awards, had work reprinted, and collections followed suit. Rather than produce disposable stories, Silverberg shifted to stories that rewarded re-engagement, which became the cornerstone of his income.

Our era resembles the pulp paperback age Silverberg wrote into than the pulp magazine era in which Heinlein formulated his rules. Shifts in the market—especially how and where we read new work—made it necessary. As editor and author Nick Mamatas argues in his essay, How To End A Story, the pulp magazines (and many slicks) favoured stories with neatly tied denouements over those which provoked further thought. Magazines needed disposable content, so a reader would pass the magazine around (a tactic used to boost the circulation numbers pitched to advertisers) and make way for the next issue.

The creative economy of the internet age is different. Magazines need unique rather than disposable, something to pull readers towards their websites. They want stories destined to be shared, discussed, unpicked, and broadcast via online channels. An ending with a ragged edge, which leaves the reader thinking, is a stronger choice than something easily forgotten. As Mamatas notes, the genre’s elder statesmen still offer editorial advice informed by the pulp era, but the economy around short fiction has changed under their feet.

HUNGRY MARKETS

So where are the copy-hungry markets Heinlein wrote for to be found in the current marketplace? Where should an aspiring pulp author, eager to cleave to Heinlein’s rules, seek to find an editor so desperate for content they’ll buy the complete dogs of our back catalogue? It doesn’t lie in short fiction anymore, and may not lie in long-form fiction either.

On the surface, a contemporary neo-pulp writer might search for what indie phenomenon Chris Fox has dubbed a Hungry Market, or “a genre that loves to read, but isn’t being supplied with enough books.” (8). This often translates to a highly specific sub-genre or trope, rather than a broad market, and indie publishing has forged whole subgenre movements by deploying this approach. In the last decade I’ve witnessed the rise of dinosaur erotica, academy romance, litRPG, technomagic, reverse harem romance and erotica, and other highly recognisable sub-genres trends that have risen, crashed to shore, and receded through the indie publishing conversation like a wave.

The curse, of course, is any hungry market will soon be overfed by other neo-pulp writers swarming the profitable niche. After a rapid rise in available content, the subgenre ceases to be hungry, satiated by the rapid emergence of backlist titles and a pseudo-cannon of “must read” titles that form a common language among fans.

I would argue the most compatible hunger for content to Heinlein’s day isn’t books at all, but social media. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, et al have the voracious need for content, constantly putting new material before users to promote engagement, then niche and categorize their audience data based on those interactions.

Alas, these platforms are notoriously difficult for creators to monetise. Social media sites trained creators to engage with them for free, trading access to an audience for much needed content. For most platforms, paying a creator for their work is not a feature, but a tool to be deployed when attempting to capture market share or threatened by competitors. Their philosophy is to get as much content for free, then pay for the most popular when it becomes clear the creators may leave.

Platforms often deploy a communal creator fund—an arbitrary amount bequeathed by the organization running the platform—in lieu of straightforward exchanges of financial capital for artistic content. They spread this monthly fund among content creators on a proportion-of-content-consumed basis, with X minutes of content consumed equating to Y cents.

These funds are frequently disconnected from revenue generated, which means they can be inflated in the early stages (to draw creators in when a revenue share wouldn’t pay out as much) and then allowed to stagnate as profits rise. The funds disconnect the value creators provide from their compensation, which leaves the system ripe for abuse.3

The Kindle Unlimited program — aimed at voracious readers willing to subscribe for ten dollars a month — is similarly hungry, and there’s a subset of Neo-Pulp writers who forged strong careers there, working at speed and tickling Amazon’s algorithms with constant new releases. Like the social media platforms above, authors are paid from a creator fund, and while their work is not generating ad revenue, it is providing considerable value to Amazon above and beyond the creative product, allowing them to run the Unlimited program and lock in exclusive content, which then pulls reader into an exclusive relationship with the Amazon shopping ecosystem.4

In all these examples, the revenue a creator can earn is supported by speed and the willingness to unleash a deep backlist. Alas, said revenue is not proportionate to the value they provide to the platform in question.

While one could argue this is true of the pulp magazine model, said magazines at least paid on delivery rather than waiting to see how ‘successful’ a story proved to be with their readership. The potential value of a story was easy to predict.

THE NEW PULP ERA

There are still authors who earn good money cleaving to Heinlein’s principles. Some even make significant money, for the moment, but it’s worth considering the publishing landscape here in 2022. Heinlein’s business practice assumes there’s always a market for a competent-but-unspectacular story, an assumption reliant on a surfeit of hungry markets cycling through disposable content at speed.

I argue the contemporary writer, producing work in systems with deep access to back list and a greater need to build their own audience, face the opposite problem. Our markets are not hungry for long—increasingly, they’re picky eaters, with broader genres giving way to specific tropes and subgenre preferences. In this terrain, a writer is arguably better off crafting more ambitious, better-quality work than the churn implied by Heinlein and his more vocal contemporary advocates.

It doesn’t mean we should eschew Heinlein entirely — in a world where back list titles hold almost as much value as new work, the ability to work fast still holds value — but I think reasserting Heinlein’s rules as habits rather than commandments is a good first step. Like much advice from the previous century, the assumptions that underpin Heinlein’s Habits are ripe for re-examination.

Embracing speed at all costs starts from a false premise. Sheer weight of production can still generate an income, just as thousands of tiny tributary dribbles may eventually form a river, but it strikes me as an approach requiring more effort for less reward. In a marketplace where the primary challenge is discovery, repeat customers and word-of-mouth are a writer’s most valuable resource.

It’s tempting to see this as a callback to hackneyed concepts around ‘quality’ art versus the commerce-driven genre, but I think the key word to focus on is ambition rather than quality. As a fan of B-grade movies and cult literature, in addition to years of teaching writing to undergraduate students, I know the endearing qualities ambitious works possess. An artist to achieve something great, even if they’re stretching beyond the limits of their time, budget, or skill, is far more interesting than an artist playing it safe. A brilliant failure is far more interesting than a stultifying success.

To echo Del Ray, ambition is a strength in the 21st century writing landscape. You’re competing for a reader’s attention against your contemporaries, but also the greats, the very goods, and the merely competent authors from many generations who came before you.

After all, Robert Heinlein’s novels are still right there, ready to be purchased in multiple ebooks, print books, and audio. And I promise you the works keeping him prominent aren’t the worst old dogs he fired off to editors desperate for copy to fill their pages. Those works only have longevity and value as a backlist because the best of Heinlein’s works elevated his profile and expanded his readership.

CONTEMPORARY PRINCIPLES

For all I see flaws in Heinlein’s rules, especially when read against his original essay, the adoption of all five in moderation can still help writers push their career forward. You must still write, after all, and finish what you start. While I believe in redrafting and editing, I believe there’s a point where you must declare the work done, and not tinker with it any further.

Where I diverge from Heinlein most is the final two steps, for putting the work to market is no longer enough. The desperate editors are not there and the hungry markets are too short-lived, and there are now enough books to feed even the most gluttonous of readers. There is more space for ambition and reworking your craft in this landscape. Your back list matters considerably more and you want to build it fast, but always question whether three okay stories are more valuable than a single great work.

The contemporary pulp writer doesn’t simply put work to market because they understand each new work builds up value around their other creations. They produce works aimed at engaging a reader long-term, across multiple works, rather than focusing their relationship on a single tale. They ask for investment across their entire career, not a single storyline. They engage their audiences directly, rather than editors, and extend beyond the parasocial relationship of author and reader.

And they keep building up their back list, one ambitious story at a time, searching for new readers because those books are still available. No mouldering wood-pulp magazines will steal away our work, wiping away our worst and our best stories as time passes. Everything we do is still available and may well be for decades to come.

To eschew the immediate appeal of hungry markets might sting in the short term, when the first books are harder to sell, but we build careers off the stories folks still read years after release.

NEW PULP

“I always wanted to be a pulp writer,” Kameron Hurley writes in her introduction to Future Artefacts, citing an affection for fantasy tales such as the Conan stories and Elric of Melnibone. Future Artefacts collects Hurley’s short stories produced for her Patreon over the last six years. Like the pulp writers, she knocked out stories in a couple of days in order to make regular cash, rather than stretching royalty cheques for longer works, which arrived twice a year.

And yet, Hurley works at a slower pace than the pulp writers of old, producing a single short story per month (albeit at a higher fee than she’d earn from most magazines; At time of writing, Hurley’s Patreon will pay her over $3,000 Australian for each new story, and she averages one a month). Those who cleave to Heinlein’s rules and the pulp ideology around fast production may hesitate to embrace Hurley as a New Pulp writer, but I often fear those folks miss the forest for the trees.

Hurly makes her Patreon income off the stories she produces, but they’re a fraction of the total content generated for her patrons. She supplements story production with broader outreach, much of it story-adjacent without becoming new fictional works. This outreach includes a monthly podcast, behind-the-scenes videos, craft advice, and one-on-one skypes with fans. Hurley repurposes these secondary works after an exclusive period: posting videos on her website; making the Get To Work Hurley podcast available through multiple podcast streams. Even the stories have a second life—Future Artifacts is published by Apex Publishing, rather than Hurley’s Patreon funds, and exists as a separate product to the works sold to her most ardent fans. While Hurley writes for her most ardent fans on Patreon, those same works spread and extend her reach into other content-hungry parts of the internet.

In this respect, at least, the pulp era hasn’t left us—the philosophy has simply mutated to adapt to a new era. Stories and novels, increasingly, are the high-end prestige products in an author’s arsenal, while the hungry markets desperate for content have become social media streams where the payday is less, but the reach is considerable.

The spirit of Heinlein’s rules remains valuable, but the blind application of the practice or exhortation of its virtues without consideration for the market in which we operate does a disservice to creators. The wood pulps are gone, and the hungry social streams won’t pay for stories, but smart writers can still leverage that hunger if they hustle. They create fewer works, but the increased reach and long life-span elevates the value of what they produce through repeated, deepening engagement.

The goal is no longer feeding a hungry periodical market with easily forgotten stories, but to write stories which reward those who come searching for more.

We may well be in a new golden age of pulp fiction, but the logic of our market demands more from us than the simple repetition of habits from decades ago.

FOOTNOTES

(1) Interestingly, many pulp paperbacks were distributed through the same magazine networks who once distributed the pulp magazines,

(2) At this stage, fewer indies publish their work in print than ebooks, leaving print-on-demand the platform of choice for small presses more often than indie authors. The long-term implications of this technology are less obvious as a result.

(3) The sole platform offering creators a profit percentage based on the ad revenue their content generates is YouTube, who made the choice while fending off new challengers in the video space. Sadly, this only applies to some content — at the time of writing, they’re monetization for the short-video offshoot they’re hoping to use as a challenge to emerging competitor has fallen back on the creator fund model.

(4) In recent years, changes on Amazon have limited organic search for books, leaving many Kindle Unlimited authors reliant on the Amazon advertising systems in order to find their readership. It’s a deft way of recouping royalties paid out to artists via the creator fund by asking authors to reinvest their profits.

REFERENCES

• Eshbach, Lloyed Arthur. “Editors Preface.” Of Worlds Beyond, edited by Lloyd Arthur Eshbach. Advent Publishing, 1947. Kindle edition.

• Fox, Chris. Write to Market: Deliver a Book that Sells, Self-Published, 2016.

• Heinlein, Robert A. “On the Writing of Specualtive Fiction.” Of Worlds Beyond, edited by Lloyd Arthur Eshbach. Advent Publishing, 1947. Kindle edition.

• Hurley, Cameron. Future Artefacts. Apex Book Company, 2022.

• Mahatmas, Nick. “How to End a Story.” Starve Better,

• Sawyer, Robert J. “On Writing: Heinlein’s Rules.” SF Writer, 1996. https://www.sfwriter.com/ow05.htm#:

• Smith, Dean Wesley. Heinlein’s Rules: Five Simple Business Rules for Writing. WMG Publishing, 2016

• Silverberg, Robert. “MIND MELD: Shrewd Writing Advice From Some of Science Fiction’s & Fantasy’s Best Writers.” SF Signal, January 2009. https://www.sfsignal.com/archives/2009/01/mind_meld_shrewd_writing_advice_from_some_of_science_fiction_and_fantasys_best_writers/

The post On Heinlein’s Habits & The Rise of the New Pulp Era: An Essay appeared first on Peter M. Ball.

July 17, 2025

How I Got From Hemmingway And Space Marines to Carver and Zombies

The Red Rain series largely exists because of cover designs. I mocked up the cover for What We Talk About When We Talk About Brains as a pre-made when I lost my job back in 2022, and loved it so much I wanted to write a book to fit it.

I ended up releasing those stories as individual titles because I’d made a cover design for my short-lived magazine project, where the first Red Rain stories appeared, and loved those so much I wanted to use them.

So it’s a very design driven project.

But before all that, the real seed was a goof I did back when I worked at the Writers Centre here in Brisbane. I was joking with friends about the film Midnight In Paris, and Cory Stoll’s incredible turn as Ernest Hemingway in the film, and riffed on one of his speeches to create a sci-fi with Stoll’s psuedo-Hemmingway voice.

The assignment was to rescue a colony that had been overrun by xenomorphs. There were eight of us, nine if you counted the android, but he had malfunctioned after being hacked by separatists and could not support us as he had when I first met him. But he was strong and made of polycarbonate steel, and he walked bravely into the elevator that took us to the lower levels. And the air was thin, without the air-scrubbers functioning, and there were aliens in the tunnels. And the plan was to send the android in first, all his glitches be damned, and if he could just hold it together long enough for the heavy bolters to get into position, we could eliminate the first wave of xenomorphs and give the rest of us a fighting chance.

I posted this to Facebook way back when I still worked an office job, and it still makes me giggle every time it shows up in my memories. Aliens style xenomorphs really are just zombies, after all. They come in swarm and they reproduce using the people they capture.

They’re just faster and freakier.

Either way, the idea lodged into my head, which is why I occasionally produce projects like a zombie series written in the style of realist literary authors like Raymond Carver.

Now I’m pondering whether it’s time to do a Hemmingway-style sci-fi series to go with it once all the GenrePunk titles are live on the Brain Jar site…

The post How I Got From Hemmingway And Space Marines to Carver and Zombies appeared first on Peter M. Ball.

July 16, 2025

Well, That Didn’t Work (Or, The State of GenrePunk Ninja in 2025)

So, yesterday I transferred the GenrePunk Ninja newsletter and the associated blog to their new homes. I fired up the new system and sent out a new update, and… well, the long-dreaded “something is going to go wrong with all these changes” feeling finally came true.

About half of the subscribers lost access to the newsletter and the sign-up forms no longer work on the GenrePunk.Ninja homepage.

So, less “wrong” and more “disasterous” on the GenrePunk Ninja front.

Most of the methods of fixing it will mean upgrading tools I’d planned to use to paid plans. This is particularly ironic given yesterday’s newsletter was all about the complications of covering expenses that occur every month/year when your writing income is asynchronus and slow building.

So I’ve implemented some quick fixes.

I stopped using Patreon in mid 2024 because I’d overcommitted myself and had some quibbles with the platform. This new iteration is very stripped back–there’s a free tier and a “chip in a few bucks to support Peter” tier, and they’re both exactly the same. There’s no expectation to pay for any of this.

Patreon also now cross-posts everythign to wordpress, which means content is no longer siloed away into their platform and doing me no good elsewhere. Patreon will also email you new installments as they go live, if you prefer to cover things in email.

This one gives you a copy of Loose Threads, the writing book I wrote by accident when I got every into Threads back in January of 2024 and wrote about 20,000 words of writing and publishing related advice on the platform.

It was the month after I submitted my PhD, so I was feeling punchy.

This one will put you into the new Newsletter system, but isn’t yet connected to a welcoming sequence, so it will basically pick up right where you are now.