Anthony Metivier's Blog

November 14, 2025

How to Approach Learning in the Age of AI (Without Harming Your Memory)

Everywhere you turn, someone’s either hyping up AI or panicking about it.

Everywhere you turn, someone’s either hyping up AI or panicking about it.

But if you’re a lifelong learner, you can’t afford to miss one simple fact:

The real danger isn’t the technology itself.

No, the major problem we all face is how other people’s thoughts about AI quietly and constantly reshape our thinking.

Pretty much on a daily basis, we undergo a whiplash of influence as one person plays prophet of doom and another froths with unhinged praise.

If you don’t study memory and its relationship to thinking as much as I do, you might not notice this shift happening.

But I do, and am concerned that many people can’t see why the disconnected dialog about artificial intelligence is so corrosive.

Perhaps most alarmingly of all is how many people adopt new tools unthinkingly and try to move faster, consume more and mistake speed for substance.

Little by little, they come to rely on the dopamine hits created by endless summaries instead of doing the critical thinking work that leads to synthesis and understanding.

The solution for you so that you don’t burn out and wind up forgetting everything you try to learn?

Slow down.

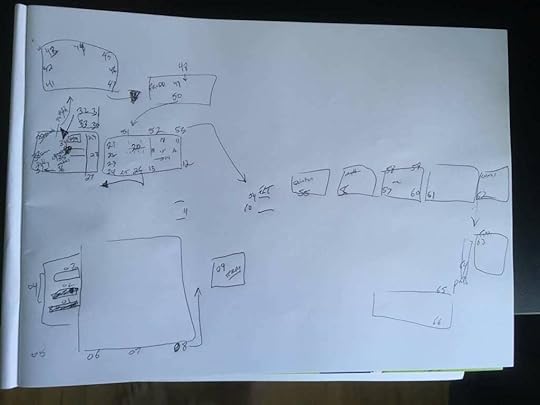

Continue using notebooks, sketches, mind maps and time with physical books.

As I’ll show you in a moment, the best AI innovators are doing just that.

And it’s smart because these simple activities will help build your memory, preserve your thinking and ensure you get the most out the new tools. While continuing to enjoy the benefits of ancient memory techniques.

To help you find the balance, in the video below and various resources I’ve shared on this page, I’ll help you explore AI technologies while creating a brain that no technology can imitate.

Let’s get started.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XOiu...

How to Use AI as a Lifelong Learner (Without Harming Your Memory)The first strategy is to keep using physical notebooks.

You might think that sounds old fashioned, but it’s not.

For example, David Perell recently had Sam Altman on his podcast to discuss his method for clear thinking.

It’s very similar to the journaling method I’ve been teaching myself for years. It involves pen, paper and the mind. Nothing more.

If the CEO of OpenAI operates this way, why wouldn’t you?

I think this example, amongst the journaling habits of other top performers is great. It helps us completely sidestep yet another paranoid conspiracy that suggests the moment you stop writing by hand, you start letting machines dictate how you think.

It’s the other way around:

The humans shaping the way artificial intelligence platforms operate regularly journal.

Why Analog Tools and Slow Reading Matter More Than EverTheir example is also useful because it highlights the relationship between the medium you use to assist your thinking, what you think about, and how you think.

And I believe it’s beyond obvious that many people mistake how fast they consume information as an accomplishment, when far too often it’s really just busy work. Little more than activity.

This confusion of activity as accomplishment isn’t a new problem. Speed reading gurus have duped people for years with the fantasy that speed is a kind of substance.

And the few good ideas you might find in speed reading books and courses? They tend to be borrowed from somewhere else.

Skimming and scanning books, for example?

Many, much better tactics existed decades before mass market speed reading books started teaching such tactics. Many ultimately wound up watering the strategy down.

These days, the entire speed reading industry is obsolete. And the reading approaches I’ve advocated since my university teaching days has never been more important.

I’m talking about my realistic approaches to reading faster, finding the main points and memorizing what matters in textbooks.

It’s more important than ever before because now, the real skill is knowing when to use shortcuts and when to apply reflective thinking so that books have time to settle in.

Sometimes it makes sense to take a second pass through courses and books. This is one reason I developed a personal re-reading strategy.

Even though I use zettelkasten and the Memory Palace technique, reviewing both your notes and the source material often gives you additional insight that you cannot get any other way.

Yet, we live in an “efficiency” focused culture where the speed of AI summaries create an illusion of depth, when in fact they are actually prompts to get back to traditional reading tactics and techniques.

The Real Meaning of Artificial IntelligenceAs you can tell by now, I’m not at all saying to avoid using AI.

Rather, I believe that the best way to protect your lifelong learning goals must involve learning to use it through experimentation.

But not without acknowledging the strange paradox we all face. Various AIs can now summarize any book you feed them. In all kinds of flavors depending on their training.

In other words, if you want to know how a celebrity would criticize a book, there’s an AI that can approximate their response for you.

Yet, despite this wealth of textual production, very few people can remember what they read last week. Some people can’t even remember what they read an hour ago.

Adding to the confusion is the fact that many people are using chatbots and calling them artificial intelligence, when they are anything but.

Unless we actively approach the learning process differently, we will continue living in a world where increased volumes of content decrease retention.

So how do we reverse the trend?

One of the best critical thinking exercises you can conduct is to think much more deeply about what this term “artificial intelligence” means.

In my view, many people use “artificial intelligence” far too loosely, almost the way we use terms like “automobile” or “vehicle.”

Rather than do that, try and stop yourself and drill down into specifics.

To that end, let’s look at some interesting authors and creative people who can help you form better definitions for the various aspects of what AI is (and is not).

Four Books That Show What Real Thinking About Artificial Intelligence Looks LikeIf you want to see what real thinking about AI and its relation to learning looks like in practice, you won’t find it summaries.

You’ll find it in the work of people who engage the physical world, wrestle with complexity, and use tools, both analog and digital.

The following authors show, each in their own way, what disciplined perception and deep understanding actually produce.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iS_Bg...

Andrew MayneAndrew Mayne is a polymathic inventor, author, magician and multi-media talent.

I recently heard him talking on a podcast he co-hosts called Weird Things about how important memory training and using physical notebooks is to him.

The episode is called Robots, AI, and the Future of Work: A Deep Dive.

In this dynamic discussion, Andrew also talks about various angles on robotics and how important human connections still remain to him… even though he is deep into multiple areas of artificial intelligence and generative chatbots.

He’s also the host of the Open AI podcast, a role that started not long after he appeared on this episode of the Magnetic Memory Method Podcast.

One thing you might notice in that episode is that Mayne is surrounded by interesting physical objects. He loves new technologies and the world they can potentially help us create, but not at the expense of the immediate, physical world.

He’s a huge fan of memory techniques too, but at this moment, I’d like to highlight one of his most interesting novels: The Naturalist.

On top of being excellent genre fiction, it’s also a very interesting meditation on the nature of the physical world, new technologies and the role of expertise.

The tactile world is everywhere in the novel and Mayne expertly conveys the raw sensory foundation true expertise requires.

Although technology is involved, the role of observation as a mental discipline shines through. Essentially, you’re reading about the human training of perception itself based on the mind’s ability to track multiple data points in both the physical and technological worlds.

In order to think about them and solve problems in both the immediate world and the digital, Mayne’s hero needs to rely on critical thinking muscles AI can never replace.

That’s why it’s ultimately a book about the kinds of computational thinking humans have done for a long time in collaboration with our technologies.

Here’s a key example, probably my favorite part of the book:

“Our war on cancer has been filled with countless maybes. Billions of dollars and millions of human hours have been spent chasing after a pattern we can’t even begin to guess at.

Even still, we’ve made some progress. Many of these maybe have panned out. People live longer than before because not all that effort was wasted. And for every maybe that turns out to be a no, we still move forward.”

Don’t mistake this for romanticism. It’s more like cognitive realism.

Our brains evolved to think through contact with the world. Digital tools can extend that process, but when we allow our fears about technology to replace our common sense, comprehension collapses.

Michael ConnellyThe second book I suggest you check out is The Proving Ground by Michael Connelly.

In this legal thrillers Connelly delivers a courtroom narrative where truth itself is on trial. Following the death of a young student prompted by a young man’s exchange with an inappropriately trained chatbot, you as the reader explore how quickly a legal team has to learn to use multiple technologies.

In the story, data gets forged, evidence gets erased, and reality itself gets imitated, messing with the procedural mechanics that both the legal thriller and crime novel rely upon. It’s like the nature of proof becomes entirely psychological as the characters feel the need to train themselves faster than the latest LLM.

But another reason I think of Connelly is interesting for those of us interested in learning memory is that he’s built an entire paracosm around a character named after Hieronymous Bosch. This is an allusion to the painter of astonishing works like The Garden of Earthly Delights and The Last Judgment.

These are fairly highbrow references in so-called popular fiction, but my point is that Connelly’s productivity is hardly the antithesis of algorithmic creativity.

It’s referential.

Plus, Connelly was a crime reporter before succeeding with fiction. And it was observing real life detectives while reading other writers in the crime genre that led him to finding the missing ingredient that brought his own stories to life.

It was literally seeing a detective put the arm of his glasses into his mouth while crouching over a victim’s body that he found what he needed to make his fiction seem real.

How is that not training in a way that reflects how AIs work to produce their outputs?

How I Trained On Connelly to Produce My Memory Detective SeriesOne reason I’m excited by some of the generative text AIs is that I’ve written many books. Some of them are memory training guides in the style of Tony Buzan’s The Memory Book.

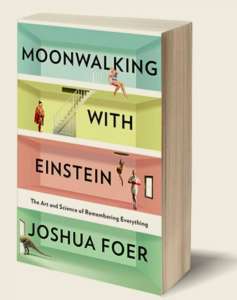

Others are more personal, like The Victorious Mind. I was influenced (or trained and prompted) by the stories shared in Moonwalking with Einstein and Ultralearning.

Yet other works are translations from the ancient memory tradition by people like Peter of Ravenna and Jacobus Publicius.

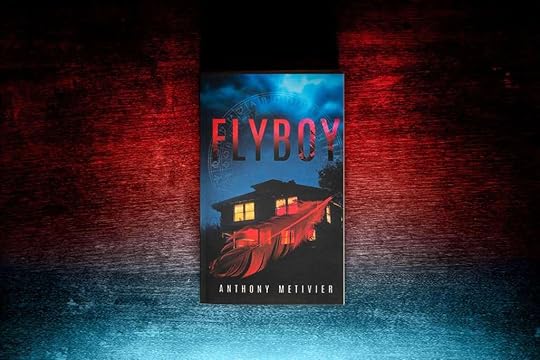

But Connelly holds a special place in my personal writing within the memory improvement niche because his books helped spawn my Memory Detective series.

There’s a long story behind how exactly Connelly arrived in my one, one I shared with Guru Viking on this episode of his podcast.

But the key point is this:

When Connelly originally inspired me to produce “Magnetic Fiction” that uses the detective genre to teach memory techniques, I originally considered reworking Sherlock Holmes stories that were in the public domain.

But that didn’t seem quite right, especially since I had written many novels before and worked in the film industry.

As I shared in How to Remember a Story, I spent years as a Film Studies professor and wound up working on a few movies as a story consultant. I even have a .

So although I could have used ChatGPT to write Flyboy, the first novel in the series, I decided to study Connelly novels even further and write the book on my own.

But it was also my memory of how stories work that I drew upon to produce the text, almost like an AI draws upon training. In fact, I would go so far as to say that everything I produced could only come from the training of what I’d previously read.

The point I’m trying to make might sound abstract, but what I’m trying to suggest is that my works are compressions of what I’ve studied. As are Connelly’s.

Speaking of “compression,” the next book I’d like to recommend takes the idea of learning and memory through training to an astonishing level.

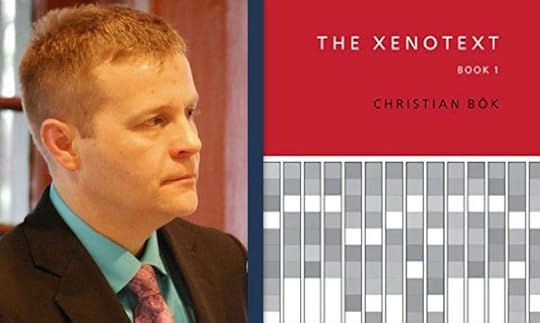

The Radical Compression of Poetry Into Living Matter:Christian Bök & The Xenotext Project

Christian Bök’s Xenotext project is the most literal act of intellectual preservation imaginable. It is a decades-long attempt to encode a poem into the DNA of a radiation-resistant bacterium called Deinococcus radiodurans so that two poems can endure for thousands, even millions of years.

As another genuinely polymathic thinker, Bök spent years shaping The Xenotext through a combination of computational tools and deeply human expertise. His work exemplifies the point I’m trying to make about learning and memory because Bök successfully managed to:

Commemorate meaning in our brave new world of big data and new interactions between biology and technologyEncode human thought in a way that resists much of the ephemeral thinking of our timesCounterbalance computational art with the AI-generated noise and “slop” we are now regularly navigating onlineApproach learning through research, endurance, patience and the materialization of conceptual ideas that anyone can enjoyTo accomplish all of this, Bök studied molecular biology, worked alongside geneticists, and carved a poem out of thousands of biochemical possibilities until it could survive as both literature and living organism. It is a fusion of the ancient ambition to become immortal with the rigor of modern science.

So when people claim that creativity ends the moment machines can mimic art, I point them to The Xenotext as an image of what books will be like in the future and in some ways have already become thanks to AI.

As quoted in a Stanford University article, we are facing the possibility of working regularly with books that “no longer take on the form of codices, scrolls, or tablets, but instead [….] become integrated into the very life of their readers.”

When you can carry not only entire libraries in your smartphone, but actually talk to them and get a response, it’s my view that we’re already living in this world.

But equally interesting to me is how Bök’s project reveals what true interdisciplinarity looks like. It’s not chasing new tools for their novelty, but extending a lineage that runs from Homer to the present on a quest to create beautiful works that endure.

Bök’s success isn’t a story of speed. It’s a story of patience, constraint, and the willingness to make thought incarnate even at a microscopic scale. The smaller the medium, the more pressure it places on the idea. Which is why the central vision of The Xenotext feels cosmically large.

The Ancient Connection Between Compressing Ideas Into Matter and Human MemoryFans of memory techniques will recognize the name instantly, but they might not have heard some of the lesser known tales of Simonides of Ceos.

I’m referring to the ancient poet credited with inventing the Memory Palace technique, or method of loci as it’s also known.

Simonides was also known to carve epitaphs in stone.

Once, on the way to catch a ship for a long, oceanic journey where he would work on writing epic poems in praise of the finest achievers of his time, he came across a dead body. So Simonides gave the abandoned man a proper burial and carved into the stone epitaph:

οἱ μὲν ἐμὲ κτείναντες ὁμοίων ἀντιτύχοιεν, Ζεῦ ξένι᾿, οί δ᾿ ὑπὸ γᾶν θέντες ὄναιντο βίου.

I pray those who killed me get the same themselves, O Zeus of guest and host, I pray those who put me in the ground enjoy the profit of life.

“Enjoy the profit of life.”

Before we continue with the story, think about what just happened.

Simonides encoded his wish for a reward by programming it into stone.

Is this act really that different than Bök encoding a poem into a deathless bacterium in the hopes that a few of our words might enjoy the profit of life beyond the death of our sun?

Later that night, the ghost of the dead man appeared to Simonides in a dream.

“Don’t get on that ship,” the ghost said.

Simonides warned his fellow travelers the next morning about the ghost’s message, but they would not listen. Everyone but Simonides got on board and the ship sank.

In response, Simonides returned to the epitaph and wrote,

οὗτος ὁ τοῦ Κείοιο Σιμωνίδου ἐστὶ σαωτήρ, ὃς καὶ τεθνηὼς ζῶντι παρέσχε χάριν

This is Simonides’ savior who even though dead, has bestowed on the living a grace.

Whether it’s Simonides chiseling an epitaph or Christian Bök encoding poetry into biological matter, the impulse is the same:

To ensure that meaning endures beyond the noise of the moment. Thought becomes durable when it is fused with matter.

This is where your learning habits matter.

Because in an age where AI can generate interpretations, summaries, and opinions at scale, it is dangerously easy to adopt other people’s conceptions of AI without realizing it.

Those impressions don’t just stay on the surface. They settle into implicit memory, the form of memory that shapes your assumptions and decisions beneath conscious awareness.

The only antidote to the harm that passive acceptance creates is deliberate, embodied thought and regular acts of memory-based learning.

This means:

Reading widely.

Thinking slowly.

Taking physical notes that force your mind to engage with the material rather than passively absorb someone else’s framing.

That’s how you prevent your implicit memory from being silently steered by the loudest or fastest voice in the room. Human or machine.

And if you want to build a system that protects your ability to learn in this way, especially now, then I strongly encourage you to go through my Self-Education Blueprint:

It’s designed to help you construct a learning philosophy grounded in clarity, embodiment, and intellectual autonomy.

If you’ve already completed it, revisit it now with the lenses we’ve explored today.

You’ll see new pathways you missed before.

And you’ll be ready for whatever comes next.

Because whatever it is, it’s coming.

And where preparation meets opportunity, there is no ceiling.

October 27, 2025

Master the Link Method to Memorize Details Fast and Recall More

The link method is a powerful memory technique that will help you learn faster and remember more.

The link method is a powerful memory technique that will help you learn faster and remember more.

You can rest assured that learning how to use it is worth your time because it has been used for thousands of years and studied by scientists.

We know how and why it works.

And one reason the technique has continually improved over the years is simple:

Many people have worked to ensure that proper mnemonic linking helps you build instant associations.

In other words, well-linked associations can help you memorize certain kinds of information within seconds.

You just have to learn it properly.

Sometimes, this particular learning strategy lets you retain information you’ve heard just once for the long-term without needing any repetition.

For example, as a memory educator, I give a lot of demonstrations in the community. I remember the names of people from live classes I’ve given decades ago.

And once you master basic linking for simple information like names, you can use the technique in more elaborate ways.

Everything from language learning to complex mathematical formulas.

The problem is…

Even simple versions of the technique can confuse people new to the link method.

This is not your fault. The confusion creeps in because different memory teachers use the term in several different ways.

In fact, the sheer number of definitions is enough to melt your mind.

Well, never fear. On this page, I’m going to do my best to reduce the confusion.

Because the reality is this:

Linking really can help you learn faster and remember more.

You just need to apply this mnemonic device in the right way and in the specific situations where it’s useful.

So if you want to master linking for faster and more thorough learning, let’s look at exactly how linking works.

And when to combine it with other memory techniques for even stronger recall.

What Is The Linking Method?In the world of memory training, we use the word “link” because this technique creates a kind of chain between what you want to remember and something you already know.

You can think of it like a gold necklace. Each loop links to the next one until the circle is completed by a clasp.

Except in memory, each mental image or association is the link that helps you find your way back to the target information.

This is part of where confusion about the technique comes in.

Is Linking Different Than the Chain Method?Memory educators often use the word link to create the mental image of a chain, as in a chain of associations.

Everyone from Bruno Furst to Harry Lorayne present the technique in this way.

This means that there’s no particular difference between linking and the chain method.

The key is that you mentally “link” or attach one item in a list to the next item. That’s why most memory trainings will present a list of words with which to practice. For example:

HeroDrillSpacecraftMusicThen most memory guides will suggest that you:

Create an image that reminds you of the first word in the chain, and“Link” the next word to the first.In the case of the example list above, you would imagine that your hero uses a drill on a spacecraft that is blasting out music.

This way of using linking sounds a bit like a story, doesn’t it?

The story is a kind of chain that you follow, and each action or action and reaction is the link that helps you “trigger” the next word.

Many people successfully use this form of linking to memorize lists, something I discuss with more depth in this tutorial on how to memorize a list.

Pros and Cons of The Link MethodLinking works well for when you need to memorize simple lists.

The approach also has its weaknesses, though, problems we’re about to fix.

What are those problems?

For one thing, if you can’t remember how the first part of your narrative chain started, you’ll struggle to trigger the next part.

It’s also possible that an individual link in your chain will go “missing.”

One key solution is called deliberate practice.

And although most memory improvement guides do give you words to practice, I’m a critic of them and here’s why:

It’s very rare in real life that we have to memorize random words.

A rare case is when you go shopping and need to get tomatoes, carrots, celery, and bread. In such a case, it does make sense to use linking to quickly imagine a tomato stabbing celery and bread with a carrot.

Even so, as a person who loves using memory techniques for large learning goals, I have to ask?

Why waste time on memorizing a shopping list when you could just write it down? That lets you save your energy for memorizing vocabulary or technical terms related to your profession.

How to Practice Mnemonic LinkingAnd that’s how I suggest that you practice. With important information that you can’t just write down.

Here’s one fruitful practice:

If you’re going to memorize your shopping list, at least get a bang for your buck by memorizing it in a foreign language.

Then, apply the linking technique to memorizing more complex terms, like:

Medical definitionsMusical termsNames you repeatedly forgetGeographical factsBasically, learn to get really good at linking by practicing with useful information that will improve your life.

Then, once you’ve got a handle on the basics, take things to the next level using the process we’ll discuss next.

From Linear Linking to Spatial Linking: The Memory Palace AdvantageAs you’ve seen, the linking method can be powerful for chaining together lists of information.

But it’s mostly linear. That means, if you can’t remember the first part of the chain, or drop one of the links, you’re in trouble.

The Memory Palace technique fixes this quirk.

If you’re not familiar with the term, sometimes it’s called the Method of Loci or the Roman Room Method.

No matter what you call it, a Memory Palace provides your brain with the ultimate, non-linear linking system for a few reasons.

Why the Memory Palace Technique is the Ultimate Linking StrategyThink back to necklace example. We’re about to expand it.

Rather than having every link in the chain dependent on the previous link, a Memory Palace lets you place each link securely in its own display case.

Each case is itself linked naturally by your familiarity with the locations you use to place them. When you have a series of locations strung together in a chain, this is called the journey method.

For more on how this technique works, watch the video below and read my full Memory Palace guide.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l5-Yr...

In sum, you’re using familiar locations as a foundational link.

Then, on each spot within the Memory Palace, you use the story method to establish a link on each and every station of the Memory Palace.

This approach helps with recall for a few reasons.

First, you don’t have to think back to how the story started or do anything elaborate to kick off the first link. You can simply think back to where you placed the first link, which gives you two chances to kickstart your list of associations.

Second, the Memory Palace technique allows for spaced repetition. This non-linear form of review means you can quickly make sure each item in your list enters long-term memory.

True, in some cases you won’t need to review the information. But it’s the missing step many of the most popular books like The Art of Memory completely miss.

Applied Example:Remembering Names Using Linking with a Memory Palace

One of the most direct ways to see linking and the Memory Palace technique at work in combination is to join me at one of my events.

As you can see in the photo above, I’m at the head of the room.

I’ve just finished memorizing the names of everyone in attendance.

To do this, I used the room itself as a kind of Memory Palace.

Exactly where Alan was sitting, I imagined a giant Allen key. He used this to open a door on the ear of Sharon, who was sitting next to him. But to remember that her name was Sharon, I pretended she was the very famous Sharon Osbourne.

Later that day, I wrote out all of the names, revisiting each one from the exact location where I’d placed the association in that room.

In some cases, I had used the bodies of the attendees as mini-Memory Palaces.

For example, Martin had mentioned a friend named Eloise was an author of thrillers. I placed an association that helped me remember this fact on his chest.

You can learn the body Memory Palace technique yourself in my tutorial on the most important ancient memory techniques.

And for another dedicated example, check out my full tutorial on .

Your Turn (Test This Linking Process)For a fun example that will improve your life immediately, go to your bookshelf or glance through your preferred e-reader.

Jot down a list of names you continually forget but would find helpful if you could remember them.

Then, create a quick Memory Palace. Let’s say you use your kitchen.

On the counter, create an association for the first nameUse the fridge door to stick an association for the second name in placePlace an association in the sink for the third nameMake sure to link each name to a distinctive association.

If name one is Lars, for example, make sure it’s Lars from Metallica pounding the counter with his drum sticks.

If name two is Lucas, have a Star Wars character like Luke Skywalker carving his name into your fridge.

If the third name is Jerry, imagine Jerry Seinfeld dancing in your sink, etc.

Later, revisit the kitchen in your imagination.

Bring each station to mind and simply ask what it was you imagined taking place on each location.

I suggest writing down your answers. Soon you’ll see exactly why I consider the Memory Palace the ultimate link:

Not only does each association help you recall the names on your list. The Memory Palace journey itself links you to the next item in the list in a logical formation.

One that is already in your memory. This fact reduces cognitive load and makes the learning process faster, more interesting and fun.

More Practical Link Method Examples You Can Try TodayOne of the first ways to use the more advanced version of linking you’ve just discovered is to your studies.

In my full guide to studying faster, I share how I used the technique as part of earning my PhD and passing various certification exams.

Another favorite example is in giving a speech from memory.

In 90 BCE, the unknown author of Rhetorica Ad Herennium created an incredible guide that I used to help me memorize this popular TEDx Talk.

Here are some other example tutorials where I walk you through various goals for which linking is helpful:

How to Memorize the Presidents

How to Build Your Own Linking System (Step-by-Step)It’s one thing to read about how others use linking.

The key is to develop your own linking system.

My favorite way to do this is to develop a mnemonic alphabet.

To do this, you simply associate (i.e. link) each letter of the alphabet with a famous figure, pop-culture icon or familiar person in your life.

Here’s a video where I dive deep into how and why this simple exercise is so important for enjoying better recall:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=caCUF...

If you think about it, the alphabet is the ultimate mnemonic chain!

To ensure that you always have mnemonic links ready for use, here’s what to do:

Get out a piece of paper and write out associations for each letter of the alphabet. Like this:

Z = ZorroY = Yankovich (Weird Al)X = XenophonW = Will SmithEtc…Once you’ve completed a list of people coded to the alphabet, create a second list filled with objects.

For example:

AppleBiscuitCameraDollEtc.

Ideally, all of your objects will connect with people or places in some way.

For example, I don’t just think of a weathervane in an abstract way. I’m thinking specifically about weathervane for W as an abstract object. No, I think about how it was used as a weapon in the movie Warlock.

Likewise, with Zorro. I don’t think abstractly about him as a pop culture character.

I focus specifically on Antonio Banderas’ performance of this character. Drawing upon him specifically was particularly helpful when I was learning German, a language packed with Z words.

For example, “zerbrechlich” means “fragile.” I simply saw Banderas as Zorro at a Berlin movie theatre with a few other images to help me memorize the sound and meaning of this word.

To be clear, the link is not just the letter “Z,” but all of the many multi-sensory sensations Banderas as Zorro helps me bring into the Memory Palace.

Multi-Sensory Linking is the KeyThe next step is to make sure the “links” are always multi-sensory.

When I say that this is the key, that’s not a simplistic cliche. The renaissance memory master Giordano Bruno often used the Latin term “clavis magnus” or “great key” in his memory training books.

To make all of your links multi-sensory, I use the eight main Magnetic Modes: KAVE COGS:

KinestheticAuditoryVisualEmotionalConceptualOlfactoryGustatorySpatialFor more ideas, The Memory Book has a broader system of multi-sensory elaborations. It has SEM3, which is based on the linking strategies of Bruno, Peter of Ravenna and Jacobus Publicius.

A Myth About Mnemonic Linking You Can Safely ForgetThe KAVE COGS model will sound like it’s missing something to people already familiar with linking.

Often memory teachers say that you have to make the associations in your links strange, crazy and bizarre.

Although that additional layer of mnemonic encoding certainly helps many of us, this study on “Bizarreness as a nonessential variable in mnemonic imagery” confirms that it’s simply not true.

In fact, one of the reasons I worked to develop KAVE COGS is that many people told me that they don’t want their minds cluttered with strange images.

Me neither, quite frankly. And now you have an alternative.

That said, memory competitors like Nelson Dellis are not wrong when they embrace the vigorously strange while memorizing.

As he shared in our discussion of extreme imagery for competition purposes, he imagines whatever is necessary to help him win.

The point is that you have options. You can safely remember more by using multi-sensory links. Or you can explore bizarre imagery.

You should just know that scientists have found that adding weirdness simply isn’t necessary in order to get great results.

Link Method Psychology: The Mindset of a Memory MasterPhew — that was quite a deep dive into linking!

And if I’ve succeeded, you’ve seen how even a simple chain of associations can serve as a portal to the larger memory arts used by our ancestors for more ambitious learning goals than memorizing lists.

You’ve also learned more about how advanced mental imagery is multi-sensory.

This means that your memory is not limited by space.

The only limits you face come down to strategy and deliberate practice.

That’s why my message always involves the core suggestion that before you practice with a meaningless list of words, you take a moment to define why you’re memorizing.

Then practice with information that gets you closer to your goal.

That way you can improve your memory while learning in ways that help you experience accomplishment every time you use linking.

So what do you say? Are you ready to put linking to work? If you’d like to go deeper into memory improvement you’ll find more step-by-step exercises inside my free Memory Improvement Kit.

I hope you enjoyed this tutorial, and please remember:

Every link you create is more than a memory trick.

It’s a step toward mastering your mind and experiencing learning as a lifestyle and an art.

October 13, 2025

How to Get Rid of Brain Fog (Fast Relief + 7-Day Plan)

Today I’m going to show you how to get rid of brain fog based on the research I’ve done to handle the problem for myself.

Today I’m going to show you how to get rid of brain fog based on the research I’ve done to handle the problem for myself.

I knew I had to take decisive action because when left untreated, brain fog is likely to get worse.

That means, your focus could continue to fade.

You may fail exams you want to pass.

And learning that language you dream about speaking fluently? It will continue to feel like a slog.

Worse, remembering the names of new people and even loved ones will potentially get harder and harder to retrieve.

But here’s the very good news:

You can reduce the impact of brain fog.

Possibly even eliminate it.

On this page, I’m going to share with you exactly how I resolved my brain fog in a step-by-step manner. And give you a 7-day routine you can start benefiting from immediately.

Important: The experience I’m sharing is educational and not medical advice. If your symptoms are new, severe, or worsening, see a clinician and discuss any changes before you try any of these suggestions.

As discussed in my book, The Victorious Mind, getting proper medical advice while researching solutions is what I’ve always done.

So, if you’re ready to reduce the impact of brain fog on your life, keep reading.

We’re taking a deep dive into what brain fog is and how to beat it.

What Is Brain Fog?Brain fog is defined as mental fuzziness. Its symptoms include:

Mental exhaustionReduced cognitive abilityLack of concentrationFeeling “spaced out”Foggy headLong-term memory lossAnother way to define it comes from the scientist Karan Kverno, who says that it is “the subjective experience of neuroinflammation.”

Just as important as the definition, we have to take note of this condition.

For example, mental fog has only gotten worse since the pandemic. Studies show that Long Covid Syndrome (LCS) can create or aggravate it.

People undergoing chemotherapy may also suffer increased incidences of mental fog.

With its ongoing evolution in mind, let’s look deeper at these symptoms.

SymptomsMental exhaustion can be defined as everything from lack of motivation to irritability. It can have short-term or long-term effects.

Reduced cognitive ability can involve things like struggling to complete tasks that should be deep in your procedural memory.

Poor concentration is not only about focus. It can involve difficulties in sitting still. You might also notice that you lose things more often.

Being spaced out involves mind wandering or feeling disconnected with reality.

And having a foggy head gets that term because you might feel like your mind is cluttered with dense clouds. You may be easily distracted or confused.

When I was still on the hunt for a brain fog cure, I experienced all of the above symptoms. In my case, each symptom was exaggerated by taking lamotrigine for manic depression.

Fortunately, I asked my doctor about alternatives (just like you should do). We found that a complete dietary overhaul enabled me to stop taking this medication.

Now all of the brain fog issues it caused are over now and I find it easier to concentrate on demand.

All the more reason to regularly visit your doctor and discuss everything.

In my case, it’s clear that a medication that was no longer needed was a huge driver of the symptoms. But many people don’t get regular medical reviews, which are so needed in our era of automated prescription renewals.

Beyond medication, there are many lifestyle culprits you can eliminate to deal with brain fog and other aspects of cognitive decline. These include:

Lack of exerciseComputer use in bed (instead of using this reading before bed protocol)Poor diet, especially from eating foods that harm the brainDehydrationInsufficient sleepUndiagnosed health issuesStress and anxietyDepressionChronic painGut healthAging (especially when chemotherapy is in use)NeuroinflammationEven air pollution has been studied for how it contributes to brain fog in different parts of the world. So if you can’t find other reasons behind why you keep forgetting things, consider getting air filtration systems where you work and sleep.

Even air pollution has been shown to contribute to brain fog.Quick Relief

Even air pollution has been shown to contribute to brain fog.Quick ReliefNow that you know some of the core causes, here are a few things you can do right now that will help:

HydrateAnalyze your diet and reduce caffeineTake a 5-10 minute walk (or if you want to be as polymathic as Thomas Jefferson, he would suggest at least 2 hours of exercise daily)Practice box breathingOpen any curtains so you’re exposed to more daylightMake a plan for an improved bedtime routine you can follow tonightComplete one of the memory drills I teachPlease don’t underestimate these simple steps.

While my wife was away recently, I fell out of my usual bedtime reading habits and started watching a series.

Brain fog quickly crept back into my life. But by catching myself in this habit and returning to my bedtime reading protocol, it quickly receded.

7-Day RoutineAgain, the following suggestion is educational only and not medical advice. Always see a clinician.

Day 1: Reset Your System & Get Some Simple WinsMake an appointment to see your doctorHydrate upon waking, ideally with room temperature waterPlace a book you plan to read on your pillowKeep hydrating throughout the dayGet 5-10 minutes of morning light on as much of your skin as possibleTake a morning walkCut off caffeine at least eight hours before sleepJournal your day, repeating in your own words what you’ve learned the way Benjamin Franklin formed long-term memoriesRead the physical book you’ve already prepared in the evening instead of looking at any kind of screenDay 2: Fuel Review & RhythmRepeat the hydration and daylight protocolsAdd hip and shoulder circles to your morning walkRun a Magnetic Alphabet drill using the pegword method for your memory exerciseContinue the caffeine cutoffContinue journaling, adding some of my journaling protocol for more winsRead a physical book before bedDay 3: Expand Your FocusContinue all of the hydration, daylight and walking protocols and learn the mnemonic linking methodApply it to learning a fact, such as a nutritional detail that will help motivate any dietary changes recommended by your doctorWhile journaling, jot out the dietary fact you learned and use reflective thinking to expand your plans for self improvementDay 4: Bump Up Your Movement ProtocolContinuing your morning protocols, start to walk more brisklyLook for an outdoor gym or tree branch where you can hang to improve your shoulder mobilityUse the memory techniques you’ve studied so far to Wind down with journaling and reading in a device-free zoneDay 5: Reduce Cognitive LoadFollowing your morning protocols, declutter one area that drains your attentionStudy how to reset your dopamine levels and memorize a fact about this area of self improvementCall a friend just to chat and reminisce for an easy and fun memory exerciseClose the day with journaling and readingDay 6: Add a Meaningful ChallengeAfter completing your morning hydration, sunlight and exercise protocol, write a list of meaningful skills you’ve always wanted to learnCommit in writing to tackling one of them for the next 90-days (a musical instrument, learning a language, memorizing poetry, etc.)Revisit the commitment in the evening and spend 10-15 minutes preparing Memory Palaces for your new learning challengeSelect a book you already own related to the challenge (or order one before starting your computer curfew)Day 7: Review & AdjustAfter completing your morning protocol, write in your journal about what you feel helped the most over the past six daysIdentify one thing you can change over the week to comeShare your biggest win with someoneWind down early and practice a concentration meditation after readingTreatmentsI know it can be frustrating looking to doctors and science to cure your brain fog. Often doctors don’t have enough time to go through your entire history and look at all aspects of your lifestyle.

You should still consult them, however. And insist that they take the time.

In fact, talk to as many people as you can.

As Dr. Raphael Kellman talks about in his Whole Brain Diet book, people need “will” to fix their brain fog issues and the best way to get this is by tapping into the largest community possible.

In addition to consulting medical professionals, you should discuss treatment options with family and friends who can support you.

And the good news is that there are a number of powerful ways to cure your brain fog.

We’ve covered some already, but let’s look at each in greater detail, along with some research resources I think you’ll find useful. I know I sure did.

DietAccording to Dr. Kellman, a “whole brain diet” should be one’s first line of attack. The core of his idea involves the role of healthy bacteria in your gut. As many people have discussed, your digestive system is like a “second brain” connected via the vagus nerve, so it’s important to feed it correctly.

SleepDiet and sleep go together in many ways.

For example, Dr. Kellman shows how preservative dyes can interrupt sleep. Since both the dye and the lack of sleep contribute to brain fog, people who react to the dyes suffer twice as much.

In addition to checking your sleep rituals and making sure you’re getting enough, do a thorough dietary analysis for ingredients that could be robbing you of rest.

There are many dietary and lifestyle choices that could be robbing you of the precious sleep needed to keep foggy head symptoms at bay.Fitness

There are many dietary and lifestyle choices that could be robbing you of the precious sleep needed to keep foggy head symptoms at bay.FitnessPhysical activity and brain health are well-studied.

The good news is that you don’t need much. Even just a short, brisk walk every day provides tremendous health benefits for both your body and brain.

However, I’d suggest regularly adding more challenges to your fitness routine. It’s easy to get complacent and bored, but if you keep researching physical fitness and adding new things, you’ll be more motivated and encouraged.

Above all, exercise as a treatments is preferable to something like taking supplements. This is because many issues can arise from mixing off-the-counter substances.

For example, someone might say that Vitamin B12 is the ultimate weapon against brain fog.

However, you could easily overdose on it. Or, a supplement might interfere with some other absorption process in your body, especially if it’s already adequately covered by your diet.

Always see your doctor and ask for a full blood panel before taking any advice – including the advice on this page.

Get More LightI mentioned getting more light in my quick fix and 7-day routine sections.

For some people, this will be easy.

But if you live in an area with constant bad weather or your home has poor access to outdoor light, discuss getting a light box or similar device with your clinician.

During the years I lived in Germany, which is notorious for its long and dark periods, I used a variety of lamps to help reduce the impact of poor weather days.

Another thing that helped, which is something to explore if you’re able, is planning travel in advance. I used to anticipate bad weather in northern Europe and make sure I was already booked at my favorite hotels in Greece and Spain.

How to Fix Brain Fog: My Personal Secret WeaponsFor me, the solution to my brain fog was not knowledge.

Most of what cures brain fog boils down to common sense.

The problem is in remembering to put the information into action.

To make sure that I reached my life improvement goals, I did a few things. Here are those steps:

One: Make A Goal and Journal About ItFirst, I used The Freedom Journal to set a 100 day goal. It’s a great tool because it’s big and visually striking. That makes it hard to miss.

For each of the brain fog treatments above, I made a handwritten commitment.

I recommend you do the same. There’s something deeply personal about writing intentions out by hand.

Richard Wiseman collects some of the scientific evidence around why writing by hand works in his book, 59 Seconds: Think A Little, Change A Lot.

Two: Connect With A Larger VisionSecond, I wrote a “Magnetic Vision Statement” around the exact nature of my brain health goals.

This is all part of establishing the mental strength needed to stick with the lifestyle changes – which are admittedly hard to consistently pursue.

One great thing about this activity is that it gets you more into your body and out of your head (where the problem lives).

Here’s a tutorial on creating a vision statement for your memory. In your case, you’ll want to focus specifically on your vision for tackling your cognitive dysfunction.

If you prefer, you can also explore mind mapping as an alternative to writing your vision statement in a journal.

I’ve built a business through many mental challenges even more difficult than brain fog, and keep this business-development mind map in sight all the time so I don’t forget my mission and my goals:

Vision statements and mind maps are not magic bullets.

But the great thing about the mind map technique is that you can do it purely on the basis of images. I don’t have to read anything and am reminded of my goals by engaging images that are easy to understand at a glance.

And because they’re deeply personal and connected to a variety of memories, they quickly inspire me, even on the foggiest of days.

Three: Memorize The Steps You’ve IdentifiedEverything worth doing involves multiple moving parts.

And anything modular can essentially be memorized as a list.

For example, I was overweight when I first tackled my brain fog in earnest. I got a health coach and a personal fitness coach.

To help me remember the choreography of various stretches at the gym, I used a Memory Palace. I used the same memory techniques to help me deeply internalize information about how to eat better.

Four: Get Plenty of Brain ExercisePeople are currently stretching the limits of their minds with more information than ever before.

But constant exposure to the Internet is not necessarily exercising your cognitive functions.

You need real brain exercise, the kind that occurs offline and truly challenges your mind. There are many brain games for adults, but I strongly advise you favor the offline versions for best results.

Personally, I work a lot with playing cards.

You can see one of the challenges I complete in this video if you want to adopt a simple and fun brain-maintenance exercise for yourself:

Five: Take On Meaningful ChallengesAs human knowledge grows, meaning seems to diminish. We now understand so much about how the universe functions that we’re living in an age of anxiety.

Why?

Because few can agree on the fundamental reasons why anything exists at all.

And as more voices crowd online to argue about how things should be going forward, it can be hard for people to feel like they’re anchored to a solid position that makes sense for them.

The solution?

Create your own meaning.

There are many ways to do this, such as studying:

PhilosophyMusicArtLanguagesCulture

I recommend you take on long form learning projects by designing your own 90-day learning missions.

I’ll be sharing how I do this for myself in my popular Read with Momentum program.

This form of self-study is powerful for fending off brain fog because it defeats the despair that leads to depression – a common cause of mental fuzziness.

Although I haven’t tried any of the following personally, I’m a keen reader of as much memory science as I can find.

Here are some of the more radical and interesting approaches you likely haven’t heard of before:

Transcranial PhotobiomodulationAs you can see in this scientific study, researchers are studying various headsets and goggles to help the brain combat neuroinflammation.

The light-based procedure directly stimulates cellular energy production in the brain.

Researchers expect that, upon further validation, the technique will succeed because it can be conducted at home. It should be relatively inexpensive too.

Stimulating NeurogenesisThe death of brain cells could be a major cause of brain fog, along with the struggle to learn new things quickly.

These researchers are identifying various genes to help identify methods that will help the brain create new neural pathways. Although they are currently focused on people with Alzheimer’s disease, the findings could well help others who suffer brain fog for a variety of reasons.

Minimizing Electronic ExposureAlthough some people criticize concerns about our constant exposure to computers and cell phones, these researchers have explored the role of electromagnetic pollution.

The major challenge they point out is that proper measurements aren’t always possible.

But the data they have been able to gather suggests that it should be possible to not only reduce the amount of energetic pollution to which we’re all exposed. It should be possible to reduce the energy costs we pay too.

Sound TherapyI’ve been listening to a lot of singing bowl sound therapy sessions lately. Particularly via a YouTube channel called Mindful Melodies:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nodOE...

As these researchers note, the relaxation benefits are often profound.

Although I can’t find any studies that state directly that singing bowls specifically help with brain fog, this study found many benefits for overall well-being.

And there’s solid scientific evidence that sound therapy helps with other cognitive issues.

My acupuncturist uses sound therapy a lot in her clinic.

But she also told me that she recently bought a CD player so she can listen to music offline.

Sure, there are still electronics involved. But she’s able to use a long headphone cable and reduce the time exposed to any device while still listening to music that could be helping modulate various brain wave patterns.

In all things, the future holds many exciting options, so watch this space for updates as I continue to explore new research as it arises.

How To Fix Brain Fog PermanentlyAs you can see, there are clear causes and solutions when it comes to brain fog.

But the final bit of common sense we need is this:

Rinse and repeat.

Your brain is a living organ.

You don’t get to stop solving the problem of brain fog.

You need to think and act like a gardener of your mind.

Keep tilling the soil.

Keep planting seeds.

Keep fertilizing, watering and clearing away the weeds.

You’ll be glad you did!

And if you’d like help with remembering everything involved, grab my FREE Memory Improvement Kit now:

It will teach you to use the same Memory Palace technique that helped me remember the self care needed on a daily basis to keep brain fog at bay.

So what do you say?

Are you ready to take care of that brain of yours?

Never forget:

You’re the only one who can!

October 6, 2025

Long-Term Memory Loss: 5 Proven Ways to Stop It

Worried that you might be suffering long-term memory loss?

See if you can relate to a scenario like this:

I have come to this area a hundred times before.

Yet, I’m lost in this maze of streets now.

Where’s my schoolmate’s house?

Wait, schoolmate, or was she my colleague at work?

If an inner voice like that sounds familiar, it could indeed be your long-term memory acting up.

The question is, what causes long-term memory loss? What are its symptoms? And, how do you treat or prevent it?

In this article, I’m drawing upon my fifteen years experience as a memory improvement teacher to help you understand and avoid long-term memory loss.

You’ll discover how to identify it, and get proper treatment if needed.

I’ll also show you a powerful, “magnetic” way to improve your memory so it stays intact even as you age.

Better than that, I’ll show you some simple memory exercise routines I practice myself to keep sharp as I approach my fifties.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

What is Long-Term Memory?What is Long-Term Memory Loss?Symptoms of Long-Term Memory LossWhat Causes Long-Term Memory Loss?How is Long-Term Memory Loss Diagnosed?How to Treat Long-Term Memory Loss5 Ways to Boost Memory and Prevent Long-Term Memory LossLet’s start with a quick look at long-term memory. Definitions are important because often people don’t stop to consider exactly what this type of memory really is.

Long-term memory is how your brain encodes and remembers events, facts, and how to do things.

For example, if you can remember your high school teacher’s name or the route to the house you stayed in 20 years ago, that’s information stored in your long-term memory.

How is it different from short-term memory?

Short-term memory (or working memory) is how your brain stores things temporarily. Examples include a grocery list, or what you had for lunch earlier today.

How do short-term memories wind up in long-term memory?

Usually through some kind of repetition or process of learning that leads to what memory scientists call “consolidation.’

In other words, the more you deliberately recall memories, the better they get consolidated into permanent, long-term memories.

So, how are these memories stored in the brain?

Assuming your brain is free from any memory disorders, short-term memory activates your prefrontal cortex, frontal lobe, and the parietal lobe of your brain.

The hippocampus brain region is responsible for the consolidation of info from short-term to long-term memory.

And, your long-term memory is associated with the prefrontal cortex, cerebrum, frontal lobe, and medial temporal lobe.

Types of Long-Term MemoryI mentioned the recall of a teacher’s name or a street address. Those two details are actually a kind of information called “semantic.”

Overall, your brain stores many types of long-term memories, not just semantic memory.

You also store episodic memory, procedural memory, implicit memory (non-declarative memory), and explicit memory (declarative memory).

For example, if your teacher’s name is a semantic memory, remembering the time your teacher gave you an A+ is an episodic memory. It is literally an episode from your life.

Your ability to effortlessly jot out the alphabet with a pen or pencil? The same teacher may have given you the skill, but it’s a procedural memory that helps you remember how to recreate your semantic memory of what letters the alphabet contains.

Fascinating, isn’t it?

Yes, and these differences in the various types of memory and kinds of information really matter. That’s because they make the deep-dive into all things related to long-term memory loss we’re about to discuss much more valuable.

What is Long-Term Memory Loss?When you find it difficult to remember any of the information types we just discussed, provided that you learned it in the past, we call the failure to retrieve these details or skills long-term memory loss.

Is long-term memory loss the same as dementia?

No. Long-term memory impairment isn’t the same as dementia. Not even close.

However, it can be a sign of dementia.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, dementia is an umbrella term for “diseases and conditions characterized by a decline in memory, language, problem-solving, and other thinking skills.”

Alzheimer’s disease specifically is a kind of cognitive impairment that progressively destroys your episodic memory, thinking abilities, and the ability to do even simple tasks like writing.

Around 10% of Americans above 65 years of age are said to have Alzheimer’s disease. And Alzheimer’s disease happens to be the most common cause of dementia.

How does Alzheimer’s disease affect long-term memory?

The first symptom of Alzheimer’s disease is short-term memory impairment. Long-term memory impairment follows, along with other symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia.

So even though you’re probably not suffering any kind of dementia if you can read this page, if your memory is currently affecting your ability to perform daily chores, it’s worth checking things out with a doctor.

Doing so is critically important because many people diagnose themselves. But as we’ve seen there are different kinds of information and various brain problems influence them differently.

Different types of dementiaThat’s why it’s important to understand the many types of dementia. Beyond Alzheimer’s, these varieties include:

Lewy body dementia: This is an umbrella term for Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia — both characterized by abnormal deposits of the alpha-synuclein protein in the brain.

It usually sets in after the age of 50. Dementia symptoms are episodic loss of long-term memory, movement problems, and decision-making difficulties.

Frontotemporal dementia: This dementia is caused by progressive degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobe of the brain. It usually starts with behavior changes, and could eventually lead to severe memory impairment.

Vascular dementia: This is caused by reduced blood flow to the brain due to stroke or any other vascular brain damage. It causes progressive memory impairment and affects your attention and problem-solving abilities.

Remember, while memory impairment is a symptom of dementia, having long-term memory impairment doesn’t always mean you have dementia.

Also, note that dementia is often confused with cognitive impairment conditions like amnesia. One way that professionals test to make sure the diagnosis is correct is to have the patient play games that help identify dementia.

People with amnesia find it tough to form new memories. Others are unable to recall facts or past experiences. The two main types of amnesia are anterograde amnesia (characterized by short-term memory loss), and retrograde amnesia (inability to recall long-term memories that happened before developing amnesia).

So, is long-term memory loss different from Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)?

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is the intermediate stage between normal age-related memory difficulties and dementia.

People diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment have significant short-term memory impairment. But, for some people, it will eventually progress to severe long-term memory impairment and even dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease.

How is long-term memory loss different from short term memory loss?You’d be able to remember incidents from 15 years ago when you experience short-term memory loss, but you’d forget details of what happened 15 minutes ago.

Tests for short-term memory impairmentYour doctor will probably start with a medical history. This initial investigation may be followed by cognitive function tests, blood tests, MRI or CT scans, or cerebral angiography.

Please don’t try and test yourself.

As I discuss in my books on learning tutorial, there’s something the brain does called predictive processing.

If you determine on your own that you have short-term memory loss when you actually don’t, this process can cause you to create problems you don’t actually have.

Or it can make a mild memory impairment worse because you start focusing on it in a negative manner, rather than in a positive and preventative way.

How do you prevent short-term memory loss?The simplest way to prevent short-term memory impairment is to combine plenty of physical fitness with a good diet, sleep and various memory games, crossword puzzles, or sudoku.

I also suggest spending time with activities like the neurobic exercises I share in this video tutorial:

By exercising your eyes, ears and your mind at the same time, your memory gets a full workout that transfers to other types of learning and memory tasks.

Please don’t skip this kind of activity. Get in at least a little practice daily, everything from juggling, writing with your non-dominant hand and memorizing playing cards.

You won’t regret it.

Now, let’s look at the ways long-term cognitive impairment like Alzheimer’s disease manifests itself.

The main symptom of long-term memory impairment is forgetfulness of important things or events that happened earlier in your life.

Here are some examples:

Forgetting the name of the countries you’ve lived inMixing up names of people and wordsForgetfulness of common wordsLosing your way in familiar placesConfusion about time and datesRepeating the same questions or personal stories frequentlyDifficulty following instructionsIrritability and other mood changesAll of these signs and symptoms should be reviewed with a doctor.

Checking in with a medical professional is important because early intervention makes a big difference when it comes to long-term brain health.

You’ll also enjoy better piece of mind merely by taking steps to educate yourself with qualified help.

Now let’s look at some of the factors that might cause the symptoms we’ve just discussed.

Long-term memory problems could occur due to several reasons:

Anxiety and depressionSide effects of prescription drugsVitamin B-12 deficiencyFatigue and sleep deprivationThyroid problemsDrug and alcohol misuseChemotherapyTraumatic Brain Injury (TBI)Brain tumor, encephalitis, stroke, epilepsy, transient ischemic attack, transient global amnesiaSleep apneaKidney and liver disordersMild Cognitive ImpairmentDementia and Alzheimer’s disease

You may also wonder:

Does aging lead to memory loss?Yes, your long-term memory can get weaker as you get older. So, occasional forgetfulness – or memory lapses like forgetting your new neighbor’s name – is normal.

This kind of forgetfulness is just a part of normal aging, and won’t affect your daily routines or the quality of your life.

But how do you know whether you should get medical help or not?

Let’s see.

When should you see a doctor?Visit a doctor if:

Your memory problems start affecting your day-to-day activitiesYou had a head or brain injuryYou’re disoriented or experience deliriumYou have other symptoms like headaches, sluggishness, or vision problemsWhy is it essential to diagnose long-term memory impairment?Some people hide their memory problems due to fear of social rejection or family issues.

But, you should get any memory troubles diagnosed by a doctor, because in most cases it can be treated partially or entirely.

Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia will help you sensitize yourself and loved ones about the illness, get proper care at home or at a facility, and get support from organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association.

So, how can it be diagnosed and treated?

To evaluate long-term memory problems, doctors typically perform the following steps:

Medical history, including your family history, and any medications you take.Physical exam to check for symptoms like muscle weakness.Neurologic exam and questions to check for signs of cognitive impairment. (For example, basic calculations, naming common items, and writing short sentences.)

Depending on the results, your doctor would prescribe some or all of the following:

A blood test to check for vitamin deficienciesUrine testsNerve testsBrain imaging tests like computerized axial tomography (CAT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)Neuropsychological testing to find the exact reason for memory problems like Alzheimer’s diseaseA holistic examination and the results of these tests will help your doctor make a correct diagnosis.

Based on the diagnosis, your doctor might refer you to a geriatrician, neurologist, or psychiatrist to medically manage the condition. Or they may refer you to a psychologist to help you cope with memory problems.

The treatment of long-term memory impairment will depend on the underlying reason for your mental condition.

For instance, if cognitive impairment is due to vitamin B12 deficiency, the doctor could prescribe vitamin B12 injections. Or, if the underlying cause of your forgetfulness was a brain tumor, then you’ll need surgery to remove the tumor.

But, think about this:

Wouldn’t it be better if you could prevent memory problems instead of seeking treatment after it reaches advanced stages like Alzheimer’s disease?

5 Stimulating Ways to Boost Memory and Prevent Long-Term Memory LossThese simple yet powerful activities will help you boost your mental function.

They work by strengthening connections between your nerves, helping compensate for any cognitive impairment due to changes in your brain.

Building Memory Palaces is one of the easiest and most powerful mnemonic techniques to improve your long-term memory.

It allows you to develop your spatial memory while exercising your episodic memory, procedural memory, semantic memory, and more.

When combined with Recall Rehearsal, you’ll be able to move information into long-term memory faster — and with predictable and reliable permanence.

You can also use any other memory technique inside of Memory Palaces (but not the other way around).

Here’s how to use it:

Imagine you need to understand DNA sequencing techniques and be able to recall them later.

Mentally walk through a familiar place like your home or office. Place the facts related to one DNA technique in your entrance hall, all facts related to the next technique in your bedroom cupboard, and so on.

As for remembering complex DNA-related words, associate them with everyday words already in your memory — e.g., to remember Cytosine, associate it with cycle.

Later, take a mental walk through your home, and you’ll easily recall all the DNA techniques.

And, the more you recall (recall rehearsal), the better you’ll commit this information to your long-term memory.

Regular physical workouts are proven to enhance the development of new brain cells in the brain. Exercise lowers the risk of age-related brain impairment and protects the brain against degenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s or Mild Cognitive Impairment.

In a study, a few participants were subject to MRI scans and a series of cognitive tests before and after a physical workout over a period of 12 weeks.

Researchers found that those who exercise regularly could remember things long after the workout was over.

So, set aside at least 30 minutes of your day to walk briskly, run, dance, or cross-country bike.

3. Eat a Healthy DietConsume a nutrient-rich, healthy diet to strengthen your long-term brain function.

Some of the best brain-boosting foods are:

Fatty fish (like salmon and mackerel)TurmericDark chocolateBerries like strawberries and blueberriesNuts and seeds like sunflower seeds and almondsWhole grains like brown rice and oatmealEggsVegetables like broccoli and kaleGreen teaAlso, stay away from a high-calorie diet. Research shows that a high-calorie diet can impair memory if it causes inflammation in certain parts of the brain. In a 2009 study, women above the age of 60 who reduced their calorie intake by 30% showed significant improvement in their verbal memory scores.

A study showed that older people who learned a new skill showed a significant improvement in memory even when tested a year later.

A seemingly simple activity like knitting is a complex one for someone new to it. So learning it from scratch will boost your brain by strengthening the connections between various parts.

You could try to learn anything unfamiliar to you — digital photography, speaking a foreign language, playing a musical instrument, or even how to fix a motorbike.

There’s also the power of relearning skills you’ve lost.

Technically, this problem is called deskilling, something I’ve gone through personally with both languages I’ve learned and skills like driving.

To explore how I re-learned those lost skills, check out this video tutorial where I take you out on the road with me for a drive here in Australia:

5. Explore Targeted Strategies For Older Adults to Manage Memory ImpairmentAgain is a challenge, no doubt about it.

When I was younger, I thought I would be fine. But as I’m approaching my fifties, I’m starting to accelerate my use of these memory strategies for coping with forgetfulness and better preventing memory decline, including stopping Alzheimer’s disease in its tracks:

Get enough sleepMake shopping lists and memorize them using this list memorization techniqueKeep a detailed calendar for the weekPlay board games and card games regularlyPay focused attention to one thing at a timeKeep all your things organized, like car keys and stationeryRegularly spend time learning new languagesUse external memory aids like ZettelkastenStay socially active and maintain meeting new people as a regular routineI know that all of these activities can sound like a lot.

In fact, some people suffering long-term memory loss will likely find so many suggestions a bit overwhelming.

The best thing is to pick just one or two things and take action.

Choosing something over nothing is key because it will promote stress reduction. Since we know that stress itself can cause memory loss, just by picking one or two activities, you stand a chance to enjoy a memory boost.

Take Control Of Your Memory LifestyleYour long-term memory is bound to decline with age and due to several other factors.

But memory loss doesn’t have to take over your life. And long-term memory impairment is often preventable.

If you’ve already got it, it’s certainly manageable. In many cases, such as with my student Matt Barclay, it’s reversible. He literally went through cardiac arrest, lost his memory and did everything we discussed above. In short order, he was able to recite a Psalm from the Bible in front of his congregation along with getting his memory back.

It’s success stories like his that make me so passionate about teaching the Magnetic Memory Method.

It’s an approach that taps into your brain’s natural ability to store and retrieve information.

And you can grab your free copy of the training now:

Enjoy taking your first step towards strengthening all aspects of your memory today.

Remember:

You don’t have to wait for forgetfulness to become frustrating.

You can start strengthening your memory today and safeguard your wisdom, your stories and your skills.

They’re what make life meaningful, so power to your progress and I can’t wait to hear your memory improvement story soon.

October 3, 2025

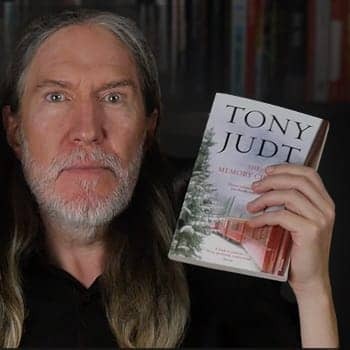

The Learning System Hidden Inside Tony Judt’s Memory Chalet

What does learning look like when your body has stopped cooperating?

What does learning look like when your body has stopped cooperating?

For many people, paralysis would mean the end of studying.

But for the historian Tony Judt, who found himself immobilized by ALS, his condition became the beginning of something unexpected: a new way of thinking about memory, language, and the act of learning itself.

Even more astonishing, he found it within himself to write a book using dictation technology while he was still able to use his mouth.

The Memory Chalet is often read as memoir, and it is.

It’s also a poignant farewell by a brilliant European historian.

But hidden in its pages is something more enduring: a learning system disguised as autobiography.

And as I’m about to explain, part of this book’s value comes from the fact that it was forged under constraint.

This isn’t just a book review. It’s an excavation of the intellectual architecture and learning models Judt left behind for any autodidact can use.

And the tools and mindsets he shared matter now more than ever.

Let’s dig in.

Nostalgia as a Learning ToolEarly in The Memory Chalet, Judt wrote something that feels like a manifesto:

“Nostalgia makes a very satisfactory second home.”

It’s a striking claim.

Especially in our world of digital amnesia, where nostalgia is often dismissed as weakness, sentimental indulgence and a way of avoiding reality. We’re told to “live in the present,” to stop romanticizing the past.

Judt thought otherwise. For him, nostalgia wasn’t a trap. It was architecture.

Unable to write notes or type a single sentence, he turned memory itself into a private study where he composed his final lessons.

Why Judt’s Take On Nostalgia Matters for LearningPsychologists like Endel Tulving have shown that deliberately engaging in autobiographical recall strengthens encoding and retrieval.

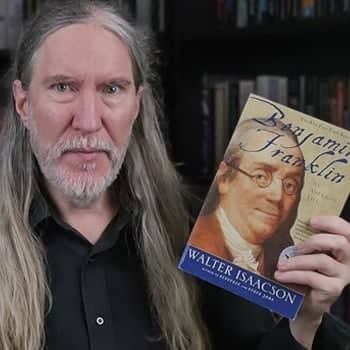

Many self-taught geniuses seem to have known this well, such as Benjamin Franklin who wrote extensively about his life and the lessons he learned along the way.

When we connect new information to vivid, personal memories, it sticks.

And we know that Judt was doing this based on his knowledge of memory techniques.

So his choice to write about his life was not nostalgia as escapism, but as construction material. And his choice to use a reframed version of the Memory Palace technique also helped him reinforce the present.

What does this suggest for you, practically speaking?

Your own history is not dead weight. It can be turned into a system for thought.

The hallway of your old school can become a place to rehearse arguments.

The kitchen you grew up in can help you memorize a list.

Even a remembered teacher’s voice can become a tool for mental rehearsal.

So Judt’s first lesson is simple but radical:

Don’t dismiss your past. Use it.

Nostalgia, when harnessed correctly, is not regression. It is forward motion.

The Autodidact’s Secret: CommunityJudt described himself as an “isolated autodidact.”

It’s an evocative phrase, but it’s only half true.

The deeper truth is this:

Judt engineered his learning life so that he still encountered other minds.

When he set out to teach himself Czech, for example, he didn’t bury himself in a textbook or trust an app to drip-feed him vocabulary.

He sought out what he called “linguists of talent.” He placed himself in the company of sharp, demanding speakers.