J.D. Chandler's Blog

February 28, 2017

The Wisdom Light Murder: Alternative Possibilities in the 1946 Torso Case

My co-author of Portland on the Take, JB Fisher, has been re-evaluating the 1946 Torso Case for a new project we are doing with KOIN TV. Slabtown Chronicle is proud to present his findings here.

Although the 1946 Torso Murder victim was never identified, the investigation turned up the disappearances of several women in the Portland area.

Although the 1946 Torso Murder victim was never identified, the investigation turned up the disappearances of several women in the Portland area.

In their 2016 book, Murder and Scandal in Prohibition Portland , JD Chandler and Theresa Griffin Kennedy make a compelling case for the idea that the unidentified torso victim that washed up on the banks of the Willamette River in April 1946 was Portland’s own AnnaSchrader. Schrader’s history with the Portland Police Bureau including her knowledge of the department’s inner workings as a private investigator and her tumultuous affair with PPB Lt. Bill Breuning would help explain both why she disappeared and why the torso case was left unsolved.

While the Anna Schrader hypothesis is intriguing and highly plausible, it is interesting to acknowledge other leads that the investigators were following in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Oregon State Police files shed light on a number of other missing persons who potentially matched the torso victim. While most of these were ruled out decisively (either because the missing persons were located or some identifying mark, feature, or condition determined them incompatible), several other subjects remained highly compelling potential matches to the torso victim. Although not officially involved in the Torso Murder investigation, Police Chief Leon V. Jenkins did handle some of the leads and may have had a motive to keep the case from being solved.

Although not officially involved in the Torso Murder investigation, Police Chief Leon V. Jenkins did handle some of the leads and may have had a motive to keep the case from being solved.

Bessie Carol Nevens

On April, 16, 1946, less than a week after the torso discovery, a hand-written letter was received by Acting Chief L. V. Jenkins at the Portland Police Bureau from Mrs. J. L. Wilson of Los Angeles. Numerous such letters were received in the days and weeks after the torso turned up, but most were quickly ruled out and the concerned parties notified. This one was different.

Mrs. Wilson explained that she was worried about her sister, Bessie Carol Nevens who had left Los Angeles July 10th, 1943 and had not been heard from since. At that time, a man had called at Nevens' home saying he was a cousin and that he was taking her up to Oregon to work on a ranch. Prior to this, a friend of Nevens' husband had contacted Mrs. Wilson requesting her sister's address. He explained that the husband was interested in sending an allotment to her. Nevens' husband was serving in the Navy as a pharmacist's mate and had never paid his wife a cent since breaking from her in 1937.

Upon learning that her sister had left with a stranger headed to Oregon, Mrs. Wilson contacted the party that had requested Nevens' address just days before she was taken to Oregon. In response, "all I got was that her husband is in the South Pacific and was not the one who called. I know that, but it could have been someone he knew."

Mrs. Wilson confirmed in the letter that her sister was in her early fifties, thus matching the age of the torso victim. She also described her sister's hair as gray, which would eventually prove a match when the head was discovered that October. She pointed out to investigators that the family had no cousins in Oregon and that she was uncertain as to the identity of her abductor.

Chief Jenkins' reply back to Mrs. Wilson was standard. He encouraged her to contact local authorities in Los Angeles to initiate a missing persons search. He reassured Mrs. Wilson that the letter would be passed along to the State Police since the crime happened outside the jurisdiction of Portland. While Captain Vayne Gurdayne of the OSP wrote back a few days later, no further follow up reports or letters exist in the file which suggests that Bessie Carol Nevens was never ruled out as the torso victim.

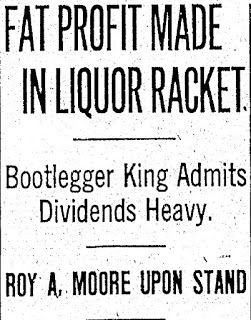

It should also be pointed out that in the mid-twentieth century, a number of ranches in central and eastern Oregon were owned by vice racketeers and corrupt cops the likes of Jim Elkins, Al Winter, Portland chief "Diamond Jim" Purcell and Earl Bush. The association of these ranches with gambling, money laundering, prostitution, and other vice is widely established. If Bessie Carol Nevens was abducted to Oregon for criminal purposes, it would be likely that law enforcement would cover the tracks since there were strong ties between racketeers and local police agencies involved in pay offs and protection.

Nevertheless, there is nothing more to determine whether Bessie Carol Nevens was in fact the torso victim. During WWII the Portland shipyards employed thousands of women. At least one of them was investigated as a potential victim in the Wisdom Light Murder.Eva Linder Panko

During WWII the Portland shipyards employed thousands of women. At least one of them was investigated as a potential victim in the Wisdom Light Murder.Eva Linder Panko

During World War Two, Eva Linder worked in the Portland shipyards building the Liberty ships that would help ensure the Allies' victory in the war. There she met fellow ship worker Tony Panko and the two were married January 29, 1944. The couple then moved to a small farm near Oregon City that Tony had acquired before the war.

Very quickly, the marriage deteriorated. Genevieve Baldwin, a friend of Eva's, would later tell the Oregon State Police that she "heard Tony threaten to kill Eva, that he was very jealous and hot tempered."

Within ten months, the marriage was over and a divorce was filed October 17, 1944. Eva then purchased a house in Southeast Portland with another shipyard worker, Herbert Troy Dennis.

Then, on November 21, 1944 the house burned down and Eva Linder Panko disappeared. She was described as in her 50s, grey hair originally brown, 5' 3" and 140 pounds with false teeth and a glass eye.

Efforts to track down Eva proved futile but investigators did locate Herbert Troy Dennis living in Seneca, Illinois. They learned that he had a brother in St. Louis and that both Dennis brothers were ex-cons with a record of forgery and burglary. It was also determined that the house fire in southeast Portland had been intentionally started for insurance purposes although no claim was ever realized.

By April 1945, Herbert Troy Dennis disappeared after violating parole and Eva Linder Panko was never found, Dr. Richardson who had performed the autopsy on the torso victim and the head ruled out Panko as the victim simply because he was confident that the torso victim had had both of her eyes at the time of death (although the head was eyeless when it was discovered).

Whether or not Eva Linder Panko could be ruled out confidently as the torso victim, she most certainly met with foul play and her ice-cold case would be long forgotten if not for the files of the torso murder.

Marian Coffey

Marian Coffey was fond of hanging out at taverns and bars with various men, despite the fact that she was married to Alton Coffey, "an insanely jealous man" who had several times tried to kill her. One of the places that Marian had frequented was the Tillicum Tavern on the Beaverton-Bertha Highway (now known as the Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway). On April 16, 1946 Alton Coffey came to the Tillicum Tavern and showed the tavern's owner Claude Clark a newspaper article about the torso discovery. "Have you seen the latest?" he asked Clark. "I think this is Marian."

In an Oregon State Police report dated April 26, 1946, Vayne Gurdayne had this to say about Alton Coffey:

“Mr. Coffey came to the Milwaukie office [of the Oregon State Police] to look at the clothing found with the torso…and stated from the description appearing in the papers he believed this subject likely to be his wife; that she disappeared on March 18, 1946; that he left for work and on his return that evening she was missing and no word had been received from her since that time. He stated they had been married at Newark, N. J. five years ago; that they came from Newark to Portland about two years ago…He stated since their marriage his wife has disappeared at least ten times; that she associated with other men and frequented beer parlors, and that he had reported her missing a number of times to the Portland Police, and at one time had located her at the Tillicum Tavern…

“Coffey described his wife as 50 years old, 5 feet 41/2 inches, 140 pounds, very dark brown hair almost black, brown eyes, dark complexion, wore glasses, false teeth. He states she had been suffering with a tumor of the womb and that part of her uterus had been removed and at one time she had had a Caesarian operation. That while employed at the Tillicum Tavern she had associated with a party by the name of Willis Baker who…lived near Oregon City; that he had checked near Oregon City trying to locate this subject without success…

“Coffey denied ever having abused his wife or having struck her but did state several times she had returned home badly bruised, etc.”

At the end of the report, Captain Gurdayne has this to say about Alton Coffey:

“Coffey was very nervous while talking to the writer and I was not too much impressed with his appearance and actions so assigned Sergeant Genn to check further as to whether or not Mrs. Coffey bore the surgical scars, etc.”

No follow-up reports survive in the OSP file regarding Marian Coffey. Much like Bessie Carol Nevens and Eva Linder Panko, there is no evidence to suggest that Marian Coffey was ever decisively ruled out as the torso victim, nor is it clear whether her whereabouts were ever determined.

The investigation of the Torso Murder case sheds a great deal of light on the lives of women in the 1940s and the prevelance of domestic violence at that time.Marie Diffin

The investigation of the Torso Murder case sheds a great deal of light on the lives of women in the 1940s and the prevelance of domestic violence at that time.Marie Diffin

On March 2, 1950, nearly four years after the torso discovery, George Alvin Diffin reported to authorities in Hood River, OR that he had important information pertaining to the case. His wife Marie Diffin had been missing since September 1944 when she left him and their four children in Springfield, OR. According to Diffin, he had heard rumors that she was in Portland and emphasized that "she was a great man chaser and hung around bars in order to get free drinks."

The fact that her parents in Klamath Falls had not heard from her made Diffin convinced that she had met at some point with an unfortunate end.

Diffin explained that in the early 1940s the couple began to have marital problems and his wife left periodically with several different men including Carl Schultz and George Hart. Although Diffin offered few specifics, he suggested that both Schultz and Hart had been involved in robberies in various parts of Oregon and that both had spent time in the State Penitentiary.

When George Diffin was asked by investigators why he had waited so long to come to authorities concerning his wife’s disappearance, he simply explained that he had visited with his daughter recently and she stated that she was going to report it if he didn’t. Even then, he waited an additional two months before reporting the situation to police in Hood River.

In closing the report, Oregon State Police private Robert Wampler offers the following remarks on George Diffin:

“It is apparent that George Diffin is not telling the whole story concerning the disappearance of his wife. Therefore, it is respectfully requested that the relatives and friends listed in this report be contacted for any information they might have concerning the above Marie Diffin and other subjects reportedly involved. It is possible that Marie Diffin is alive and her parents know of her whereabouts…

“In the event it is learned that Marie is definitely missing, it could be easily possible that George Diffin himself could be implicated. However, it is merely a supposition.”

When investigators followed up with Marie Diffin’s family members, they learned that she was indeed missing. Daughter Coleen Mae Downend (19) said that she strongly suspected that her mother was dead, “stating that the mother thought an awful lot of the younger child who was at the time the mother left three years of age and if not dead or forcible [sic] detained would have gotten some word to them for the boy’s sake.”

The daughter also explained that in addition to an operation for “female trouble” back in 1942, her mother had “a large bump on the upper right shoulder in which [she] had been advised that it might be cancerous unless attended to.”

When they spoke to George Diffin’s sister Mrs. Robert Jenkins in Hood River, investigators learned that “she was positive Marie Diffin was dead but had no idea what had happened to her or how it had come about. That the last time she had seen her in the latter part of 1943 she had had a growth on her shoulder which looked cancerous and that there was a good chance that that killed her.”

Mrs. Jenkins went on to describe her brother as “a liar and very mean,” saying that “he had a terrible temper and at one time in years gone by had threatened her, his own sister.”

Marie Diffin’s parents similarly confided to investigators that George Diffin was mean and violent and that on several occasions he told Marie that if she left he would kill her. They also confirmed that she had left with George Hart and Carl Schultz back in 1944.

While Carl Schulz was not located, the Oregon State Police spoke with George Hart who explained that he last saw Carl Schulz and Marie Diffin in late September 1944 when the two told him that they were “going so far that no one would find them…she suggested that they might go to Mexico.”

There is no follow-up report on the Marie Diffin case after March 30, 1950 when investigators spoke with George Hart. Unlike the other possible victims discussed above, there is no clear evidence that Marie Diffin fit the profile of the torso. She was (as of 1944) 35 years old, 5’2” and 140 pounds, dark brown hair, “very large rump…” However, once again, the case was never conclusively pursued and the victim is most likely missing to this day. One connection that was never investigated by the Torso Murder detectives was the possibility that the murder was connected to the nefarious actions of the Portland Police Bureau.The Wisdom Light Killer

One connection that was never investigated by the Torso Murder detectives was the possibility that the murder was connected to the nefarious actions of the Portland Police Bureau.The Wisdom Light Killer

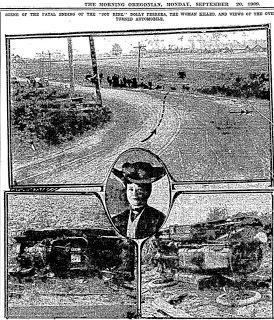

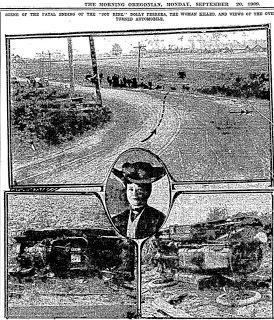

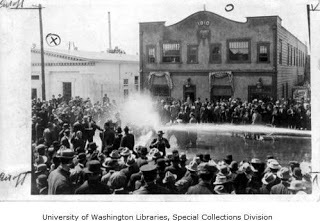

While most mentions of the 1946 discovery of a middle-age female body in the Willamette River refer to this as “the Torso murder,” Oregon State Police reports and other references in the late 1940s call the case “the Wisdom Light murder.” This is likely referring to the place where the torso was discovered—a small moorage on the Willamette River below Oregon City known at the time as Wisdom Island Moorage. Perhaps there was a light on the moorage so that the name would more closely specify the location of that grisly discovery.

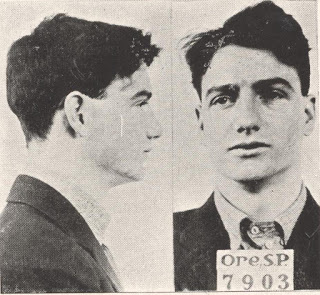

None of the cases discussed above yielded any suspects in the torso murder. George Diffin, Herbert Troy Dennis, Alton Coffey, Willis Baker, Tony Panko—none of these were pursued far enough to become suspects. Other names did come up in the investigation as potential suspects: Donald A. Benson, Richard Purnell, Russell Frederick Purnell, Carl Christian Roth alias Carl James Parnell, James Louis Purcell.

Yet no one was ever apprehended as an actual suspect in the case and the Wisdom Light killer has faded into the darkness of the long forgotten and elusive past. But if the torso was indeed Anna Schrader, then we know who killed her and why those individuals were never pursued. -- JB Fisher.

While it is not possible to say with certainty that Anna Schrader was the victim of the Torso Murder, there is compelling circumstantial evidence to support that conclusion. The evidence is laid out in my 2016 book Murder and Scandal in Prohibition Portland. We will be exploring that evidence and the case in a special KOIN TV event on Facebook on March 1st at 7pm. Please join us. content (c) jd chandler

Although the 1946 Torso Murder victim was never identified, the investigation turned up the disappearances of several women in the Portland area.

Although the 1946 Torso Murder victim was never identified, the investigation turned up the disappearances of several women in the Portland area.In their 2016 book, Murder and Scandal in Prohibition Portland , JD Chandler and Theresa Griffin Kennedy make a compelling case for the idea that the unidentified torso victim that washed up on the banks of the Willamette River in April 1946 was Portland’s own AnnaSchrader. Schrader’s history with the Portland Police Bureau including her knowledge of the department’s inner workings as a private investigator and her tumultuous affair with PPB Lt. Bill Breuning would help explain both why she disappeared and why the torso case was left unsolved.

While the Anna Schrader hypothesis is intriguing and highly plausible, it is interesting to acknowledge other leads that the investigators were following in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Oregon State Police files shed light on a number of other missing persons who potentially matched the torso victim. While most of these were ruled out decisively (either because the missing persons were located or some identifying mark, feature, or condition determined them incompatible), several other subjects remained highly compelling potential matches to the torso victim.

Although not officially involved in the Torso Murder investigation, Police Chief Leon V. Jenkins did handle some of the leads and may have had a motive to keep the case from being solved.

Although not officially involved in the Torso Murder investigation, Police Chief Leon V. Jenkins did handle some of the leads and may have had a motive to keep the case from being solved.Bessie Carol Nevens

On April, 16, 1946, less than a week after the torso discovery, a hand-written letter was received by Acting Chief L. V. Jenkins at the Portland Police Bureau from Mrs. J. L. Wilson of Los Angeles. Numerous such letters were received in the days and weeks after the torso turned up, but most were quickly ruled out and the concerned parties notified. This one was different.

Mrs. Wilson explained that she was worried about her sister, Bessie Carol Nevens who had left Los Angeles July 10th, 1943 and had not been heard from since. At that time, a man had called at Nevens' home saying he was a cousin and that he was taking her up to Oregon to work on a ranch. Prior to this, a friend of Nevens' husband had contacted Mrs. Wilson requesting her sister's address. He explained that the husband was interested in sending an allotment to her. Nevens' husband was serving in the Navy as a pharmacist's mate and had never paid his wife a cent since breaking from her in 1937.

Upon learning that her sister had left with a stranger headed to Oregon, Mrs. Wilson contacted the party that had requested Nevens' address just days before she was taken to Oregon. In response, "all I got was that her husband is in the South Pacific and was not the one who called. I know that, but it could have been someone he knew."

Mrs. Wilson confirmed in the letter that her sister was in her early fifties, thus matching the age of the torso victim. She also described her sister's hair as gray, which would eventually prove a match when the head was discovered that October. She pointed out to investigators that the family had no cousins in Oregon and that she was uncertain as to the identity of her abductor.

Chief Jenkins' reply back to Mrs. Wilson was standard. He encouraged her to contact local authorities in Los Angeles to initiate a missing persons search. He reassured Mrs. Wilson that the letter would be passed along to the State Police since the crime happened outside the jurisdiction of Portland. While Captain Vayne Gurdayne of the OSP wrote back a few days later, no further follow up reports or letters exist in the file which suggests that Bessie Carol Nevens was never ruled out as the torso victim.

It should also be pointed out that in the mid-twentieth century, a number of ranches in central and eastern Oregon were owned by vice racketeers and corrupt cops the likes of Jim Elkins, Al Winter, Portland chief "Diamond Jim" Purcell and Earl Bush. The association of these ranches with gambling, money laundering, prostitution, and other vice is widely established. If Bessie Carol Nevens was abducted to Oregon for criminal purposes, it would be likely that law enforcement would cover the tracks since there were strong ties between racketeers and local police agencies involved in pay offs and protection.

Nevertheless, there is nothing more to determine whether Bessie Carol Nevens was in fact the torso victim.

During WWII the Portland shipyards employed thousands of women. At least one of them was investigated as a potential victim in the Wisdom Light Murder.Eva Linder Panko

During WWII the Portland shipyards employed thousands of women. At least one of them was investigated as a potential victim in the Wisdom Light Murder.Eva Linder PankoDuring World War Two, Eva Linder worked in the Portland shipyards building the Liberty ships that would help ensure the Allies' victory in the war. There she met fellow ship worker Tony Panko and the two were married January 29, 1944. The couple then moved to a small farm near Oregon City that Tony had acquired before the war.

Very quickly, the marriage deteriorated. Genevieve Baldwin, a friend of Eva's, would later tell the Oregon State Police that she "heard Tony threaten to kill Eva, that he was very jealous and hot tempered."

Within ten months, the marriage was over and a divorce was filed October 17, 1944. Eva then purchased a house in Southeast Portland with another shipyard worker, Herbert Troy Dennis.

Then, on November 21, 1944 the house burned down and Eva Linder Panko disappeared. She was described as in her 50s, grey hair originally brown, 5' 3" and 140 pounds with false teeth and a glass eye.

Efforts to track down Eva proved futile but investigators did locate Herbert Troy Dennis living in Seneca, Illinois. They learned that he had a brother in St. Louis and that both Dennis brothers were ex-cons with a record of forgery and burglary. It was also determined that the house fire in southeast Portland had been intentionally started for insurance purposes although no claim was ever realized.

By April 1945, Herbert Troy Dennis disappeared after violating parole and Eva Linder Panko was never found, Dr. Richardson who had performed the autopsy on the torso victim and the head ruled out Panko as the victim simply because he was confident that the torso victim had had both of her eyes at the time of death (although the head was eyeless when it was discovered).

Whether or not Eva Linder Panko could be ruled out confidently as the torso victim, she most certainly met with foul play and her ice-cold case would be long forgotten if not for the files of the torso murder.

Marian Coffey

Marian Coffey was fond of hanging out at taverns and bars with various men, despite the fact that she was married to Alton Coffey, "an insanely jealous man" who had several times tried to kill her. One of the places that Marian had frequented was the Tillicum Tavern on the Beaverton-Bertha Highway (now known as the Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway). On April 16, 1946 Alton Coffey came to the Tillicum Tavern and showed the tavern's owner Claude Clark a newspaper article about the torso discovery. "Have you seen the latest?" he asked Clark. "I think this is Marian."

In an Oregon State Police report dated April 26, 1946, Vayne Gurdayne had this to say about Alton Coffey:

“Mr. Coffey came to the Milwaukie office [of the Oregon State Police] to look at the clothing found with the torso…and stated from the description appearing in the papers he believed this subject likely to be his wife; that she disappeared on March 18, 1946; that he left for work and on his return that evening she was missing and no word had been received from her since that time. He stated they had been married at Newark, N. J. five years ago; that they came from Newark to Portland about two years ago…He stated since their marriage his wife has disappeared at least ten times; that she associated with other men and frequented beer parlors, and that he had reported her missing a number of times to the Portland Police, and at one time had located her at the Tillicum Tavern…

“Coffey described his wife as 50 years old, 5 feet 41/2 inches, 140 pounds, very dark brown hair almost black, brown eyes, dark complexion, wore glasses, false teeth. He states she had been suffering with a tumor of the womb and that part of her uterus had been removed and at one time she had had a Caesarian operation. That while employed at the Tillicum Tavern she had associated with a party by the name of Willis Baker who…lived near Oregon City; that he had checked near Oregon City trying to locate this subject without success…

“Coffey denied ever having abused his wife or having struck her but did state several times she had returned home badly bruised, etc.”

At the end of the report, Captain Gurdayne has this to say about Alton Coffey:

“Coffey was very nervous while talking to the writer and I was not too much impressed with his appearance and actions so assigned Sergeant Genn to check further as to whether or not Mrs. Coffey bore the surgical scars, etc.”

No follow-up reports survive in the OSP file regarding Marian Coffey. Much like Bessie Carol Nevens and Eva Linder Panko, there is no evidence to suggest that Marian Coffey was ever decisively ruled out as the torso victim, nor is it clear whether her whereabouts were ever determined.

The investigation of the Torso Murder case sheds a great deal of light on the lives of women in the 1940s and the prevelance of domestic violence at that time.Marie Diffin

The investigation of the Torso Murder case sheds a great deal of light on the lives of women in the 1940s and the prevelance of domestic violence at that time.Marie Diffin On March 2, 1950, nearly four years after the torso discovery, George Alvin Diffin reported to authorities in Hood River, OR that he had important information pertaining to the case. His wife Marie Diffin had been missing since September 1944 when she left him and their four children in Springfield, OR. According to Diffin, he had heard rumors that she was in Portland and emphasized that "she was a great man chaser and hung around bars in order to get free drinks."

The fact that her parents in Klamath Falls had not heard from her made Diffin convinced that she had met at some point with an unfortunate end.

Diffin explained that in the early 1940s the couple began to have marital problems and his wife left periodically with several different men including Carl Schultz and George Hart. Although Diffin offered few specifics, he suggested that both Schultz and Hart had been involved in robberies in various parts of Oregon and that both had spent time in the State Penitentiary.

When George Diffin was asked by investigators why he had waited so long to come to authorities concerning his wife’s disappearance, he simply explained that he had visited with his daughter recently and she stated that she was going to report it if he didn’t. Even then, he waited an additional two months before reporting the situation to police in Hood River.

In closing the report, Oregon State Police private Robert Wampler offers the following remarks on George Diffin:

“It is apparent that George Diffin is not telling the whole story concerning the disappearance of his wife. Therefore, it is respectfully requested that the relatives and friends listed in this report be contacted for any information they might have concerning the above Marie Diffin and other subjects reportedly involved. It is possible that Marie Diffin is alive and her parents know of her whereabouts…

“In the event it is learned that Marie is definitely missing, it could be easily possible that George Diffin himself could be implicated. However, it is merely a supposition.”

When investigators followed up with Marie Diffin’s family members, they learned that she was indeed missing. Daughter Coleen Mae Downend (19) said that she strongly suspected that her mother was dead, “stating that the mother thought an awful lot of the younger child who was at the time the mother left three years of age and if not dead or forcible [sic] detained would have gotten some word to them for the boy’s sake.”

The daughter also explained that in addition to an operation for “female trouble” back in 1942, her mother had “a large bump on the upper right shoulder in which [she] had been advised that it might be cancerous unless attended to.”

When they spoke to George Diffin’s sister Mrs. Robert Jenkins in Hood River, investigators learned that “she was positive Marie Diffin was dead but had no idea what had happened to her or how it had come about. That the last time she had seen her in the latter part of 1943 she had had a growth on her shoulder which looked cancerous and that there was a good chance that that killed her.”

Mrs. Jenkins went on to describe her brother as “a liar and very mean,” saying that “he had a terrible temper and at one time in years gone by had threatened her, his own sister.”

Marie Diffin’s parents similarly confided to investigators that George Diffin was mean and violent and that on several occasions he told Marie that if she left he would kill her. They also confirmed that she had left with George Hart and Carl Schultz back in 1944.

While Carl Schulz was not located, the Oregon State Police spoke with George Hart who explained that he last saw Carl Schulz and Marie Diffin in late September 1944 when the two told him that they were “going so far that no one would find them…she suggested that they might go to Mexico.”

There is no follow-up report on the Marie Diffin case after March 30, 1950 when investigators spoke with George Hart. Unlike the other possible victims discussed above, there is no clear evidence that Marie Diffin fit the profile of the torso. She was (as of 1944) 35 years old, 5’2” and 140 pounds, dark brown hair, “very large rump…” However, once again, the case was never conclusively pursued and the victim is most likely missing to this day.

One connection that was never investigated by the Torso Murder detectives was the possibility that the murder was connected to the nefarious actions of the Portland Police Bureau.The Wisdom Light Killer

One connection that was never investigated by the Torso Murder detectives was the possibility that the murder was connected to the nefarious actions of the Portland Police Bureau.The Wisdom Light KillerWhile most mentions of the 1946 discovery of a middle-age female body in the Willamette River refer to this as “the Torso murder,” Oregon State Police reports and other references in the late 1940s call the case “the Wisdom Light murder.” This is likely referring to the place where the torso was discovered—a small moorage on the Willamette River below Oregon City known at the time as Wisdom Island Moorage. Perhaps there was a light on the moorage so that the name would more closely specify the location of that grisly discovery.

None of the cases discussed above yielded any suspects in the torso murder. George Diffin, Herbert Troy Dennis, Alton Coffey, Willis Baker, Tony Panko—none of these were pursued far enough to become suspects. Other names did come up in the investigation as potential suspects: Donald A. Benson, Richard Purnell, Russell Frederick Purnell, Carl Christian Roth alias Carl James Parnell, James Louis Purcell.

Yet no one was ever apprehended as an actual suspect in the case and the Wisdom Light killer has faded into the darkness of the long forgotten and elusive past. But if the torso was indeed Anna Schrader, then we know who killed her and why those individuals were never pursued. -- JB Fisher.

While it is not possible to say with certainty that Anna Schrader was the victim of the Torso Murder, there is compelling circumstantial evidence to support that conclusion. The evidence is laid out in my 2016 book Murder and Scandal in Prohibition Portland. We will be exploring that evidence and the case in a special KOIN TV event on Facebook on March 1st at 7pm. Please join us. content (c) jd chandler

Published on February 28, 2017 10:56

August 24, 2016

No Time to Learn

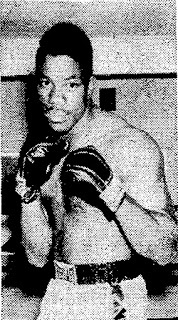

Joe Hopkins won the National Golden Gloves Middleweight Championship in 1963 when he was 17. His pro career was short-lived and the injury-prone boxer was banned by the Portland Boxing Commission in 1973 to prevent further injury. Something happened to Joe Hopkins. The young boxer, who had been a Golden Gloves champion as a teenager, described by Portland fight promoter, Sam Singer, as “a gentle, simple kid… [without] a mean bone in his body” was suddenly frantic. Convinced that his neighbors had stolen a litter of kittens from his front porch, on the afternoon of October 8, 1974, he began shooting a handgun at their house. A few days later the Portland Boxing Commission insisted that there was no brain damage that could explain his erratic behavior on the day he died, but he had been suspended from boxing the year before for fear of further injury. No one was ever able to explain what happened to Joe. In 1974, before police officers received training in how to deal with people in mental and emotional crisis, they were aware of the problem and they approached the troubled young man carefully. Officer William DeBellis, first on the scene, approached Hopkins on the front porch of his house and tried to talk with him. Hopkins, yelling that he would kill DeBellis if he came any closer ran into his house and slammed the door. DeBellis, and other officers who arrived quickly, kept watch on the house and soon found out that Hopkins had been in treatment at University Hospital’s North Psychiatric Unit. Three officers watched the house while waiting for help to arrive, but none of them noticed when Hopkins slipped out the back door and made his way downtown. Hopkins had been in trouble before; arrested in 1971 for frequenting a gambling house, he had been in and out of the Psychiatric Unit and was currently being supervised by the Metropolitan Public Defenders (MPD) office. From his house he went to the MPD office on SW 5th Avenue, and told them about the confrontation with the police. It is not clear whether his supervisor there knew that he was still armed, but he called the police to report that the young man was there and should be picked up. Hopkins, still very restless, left the office before the police arrived. When Officer Gene Maher arrived at the MPD office, employees pointed out Hopkins walking down the street. Maher and Officer Eugene Francis approached Hopkins, planning to take him into custody. Officer Bruce Harrington watched the three men from a nearby patrol car. Hopkins was still very agitated and he resisted when the two officers tried to arrest him. He pulled a .38 revolver from under his jacket and fired a shot, before Harrington shot him in the chest, killing him instantly. The death of the agitated young black man, the first suspect killed by Portland police since 1971, was considered an inexplicable tragedy, but it was the beginning of a series of shootings that enflamed community feeling and heightened tensions between African-American Portlanders and the police. Over time the shooting of Joe Hopkins would be seen as the impetus for a new round of community organizing that would uncover serious problems within the police bureau.

Joe Hopkins won the National Golden Gloves Middleweight Championship in 1963 when he was 17. His pro career was short-lived and the injury-prone boxer was banned by the Portland Boxing Commission in 1973 to prevent further injury. Something happened to Joe Hopkins. The young boxer, who had been a Golden Gloves champion as a teenager, described by Portland fight promoter, Sam Singer, as “a gentle, simple kid… [without] a mean bone in his body” was suddenly frantic. Convinced that his neighbors had stolen a litter of kittens from his front porch, on the afternoon of October 8, 1974, he began shooting a handgun at their house. A few days later the Portland Boxing Commission insisted that there was no brain damage that could explain his erratic behavior on the day he died, but he had been suspended from boxing the year before for fear of further injury. No one was ever able to explain what happened to Joe. In 1974, before police officers received training in how to deal with people in mental and emotional crisis, they were aware of the problem and they approached the troubled young man carefully. Officer William DeBellis, first on the scene, approached Hopkins on the front porch of his house and tried to talk with him. Hopkins, yelling that he would kill DeBellis if he came any closer ran into his house and slammed the door. DeBellis, and other officers who arrived quickly, kept watch on the house and soon found out that Hopkins had been in treatment at University Hospital’s North Psychiatric Unit. Three officers watched the house while waiting for help to arrive, but none of them noticed when Hopkins slipped out the back door and made his way downtown. Hopkins had been in trouble before; arrested in 1971 for frequenting a gambling house, he had been in and out of the Psychiatric Unit and was currently being supervised by the Metropolitan Public Defenders (MPD) office. From his house he went to the MPD office on SW 5th Avenue, and told them about the confrontation with the police. It is not clear whether his supervisor there knew that he was still armed, but he called the police to report that the young man was there and should be picked up. Hopkins, still very restless, left the office before the police arrived. When Officer Gene Maher arrived at the MPD office, employees pointed out Hopkins walking down the street. Maher and Officer Eugene Francis approached Hopkins, planning to take him into custody. Officer Bruce Harrington watched the three men from a nearby patrol car. Hopkins was still very agitated and he resisted when the two officers tried to arrest him. He pulled a .38 revolver from under his jacket and fired a shot, before Harrington shot him in the chest, killing him instantly. The death of the agitated young black man, the first suspect killed by Portland police since 1971, was considered an inexplicable tragedy, but it was the beginning of a series of shootings that enflamed community feeling and heightened tensions between African-American Portlanders and the police. Over time the shooting of Joe Hopkins would be seen as the impetus for a new round of community organizing that would uncover serious problems within the police bureau.

The shooting of Joe Hopkins while in a violent psychotic episode in October 1974 was seen as an inexplicable tragedy, but his death was the first in a series of events that led to a new period of community activism in Portland. In 1974 there was little oversight for police shootings. The Homicide Division conducted investigations and often they were cursory. Not since the 1945 shooting of Ervin Jones had there been major controversy or community protest over a police shooting. The shooting of Joe Hopkins was ruled justified because of his earlier violent behavior and his firing a shot while resisting arrest. Just a few weeks later though, the shooting of a second black man raised questions about how the police were being regulated. The second shooting occurred on October 27 and again it involved a young man with a police record. Kenneth “Kenny” Allen, 27, was a familiar figure on the streets of Northeast Portland. Allen, an intravenous drug user, prowled the streets looking for opportunities among the prostitutes, drug dealers and their customers; he had a long arrest record. On the night of his death two undercover police officers, John Hren, 26, and Ed May, 28, were also prowling in an unmarked car looking for prostitutes to arrest. Allen was talking with two women on the sidewalk when he saw the car with two white men pass by. He flagged the car down and asked if the men were looking for drugs. Hren told him they weren’t interested in drugs, but they were looking for women, indicating the women that Allen had been talking to. Kenny said he could take them to a brothel and climbed into the backseat of the car. Allen directed the two undercover officers to an address on N. Congress Street, but when they arrived he produced a handgun and stuck it in Hren’s left ear. He said it was a holdup and he wanted their cash. According to Hren, Allen seemed very nervous and began to pat Hren down, discovering his shoulder holster under his jacket. At that moment, Ed May, who was in the driver’s seat, pulled his weapon and fired at the man in the back seat. Both officers emptied their weapons and then jumped out of the car. Allen, who also went by the name of Kenny Nommo, was hit by six bullets which penetrated several internal organs and killed him within seconds. Hren related a dramatic tale for the Oregonian and Mayor Neal Goldschmidt praised the shooting, implying it was a good idea to shoot the “crazies with guns.” Some felt that the whole story had not been told, but a cursory investigation again ruled that the shooting was justified and there was little community outcry.

The shooting of Joe Hopkins while in a violent psychotic episode in October 1974 was seen as an inexplicable tragedy, but his death was the first in a series of events that led to a new period of community activism in Portland. In 1974 there was little oversight for police shootings. The Homicide Division conducted investigations and often they were cursory. Not since the 1945 shooting of Ervin Jones had there been major controversy or community protest over a police shooting. The shooting of Joe Hopkins was ruled justified because of his earlier violent behavior and his firing a shot while resisting arrest. Just a few weeks later though, the shooting of a second black man raised questions about how the police were being regulated. The second shooting occurred on October 27 and again it involved a young man with a police record. Kenneth “Kenny” Allen, 27, was a familiar figure on the streets of Northeast Portland. Allen, an intravenous drug user, prowled the streets looking for opportunities among the prostitutes, drug dealers and their customers; he had a long arrest record. On the night of his death two undercover police officers, John Hren, 26, and Ed May, 28, were also prowling in an unmarked car looking for prostitutes to arrest. Allen was talking with two women on the sidewalk when he saw the car with two white men pass by. He flagged the car down and asked if the men were looking for drugs. Hren told him they weren’t interested in drugs, but they were looking for women, indicating the women that Allen had been talking to. Kenny said he could take them to a brothel and climbed into the backseat of the car. Allen directed the two undercover officers to an address on N. Congress Street, but when they arrived he produced a handgun and stuck it in Hren’s left ear. He said it was a holdup and he wanted their cash. According to Hren, Allen seemed very nervous and began to pat Hren down, discovering his shoulder holster under his jacket. At that moment, Ed May, who was in the driver’s seat, pulled his weapon and fired at the man in the back seat. Both officers emptied their weapons and then jumped out of the car. Allen, who also went by the name of Kenny Nommo, was hit by six bullets which penetrated several internal organs and killed him within seconds. Hren related a dramatic tale for the Oregonian and Mayor Neal Goldschmidt praised the shooting, implying it was a good idea to shoot the “crazies with guns.” Some felt that the whole story had not been told, but a cursory investigation again ruled that the shooting was justified and there was little community outcry.

Career-criminal Kenny Allen drew little sympathy from the public when he was shot by two police officers. Mayor Neal Goldschmidt characterized him as a "crazy with a gun." Less than one month later another black man, Charles Menefee, 26, was shot to death by the police after a high speed car chase. Questions raised by the Portland chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Albina Ministerial Alliance motivated District Attorney Harl Haas to put the case before a Multnomah County Grand Jury, which again ruled that the shooting was justified. The death of Menefee certainly seems to have been justified, but the sudden frequency of police shootings and the death of three black men at the hands of police raised community awareness and the issue of police accountability became a serious issue for organizing in Portland’s African American community. Charles Menefee had a record for burglary and was most likely up to no good as he cruised the small suburban town of Canby on the night of November 20, 1974. In Canby a black man driving around was considered suspicious in itself and soon the local police approached Menefee’s car. The young man attempted to evade the police and drove north at high speed. It must have been an exciting chase as Canby, Milwaukie, Oregon City, Clackamas County, Portland and State police joined in the pursuit on Highway 99E, up Grand Avenue, across both the Hawthorne and Steel Bridges. By the time the speeding car reached Williams Avenue in Northeast Portland, not far from Menefee’s house, there were fourteen officers involved. Menefee’s car was finally forced out of control near Sacramento Street. Menefee fired at least one shot from a rifle, wounding Portland Officer Kent Perry before dying in a hail of bullets. More than fourteen officers fired dozens of bullets in the exchange of fire and Portland Officer John Murchison was struck by a ricocheting bullet and slightly wounded.

Career-criminal Kenny Allen drew little sympathy from the public when he was shot by two police officers. Mayor Neal Goldschmidt characterized him as a "crazy with a gun." Less than one month later another black man, Charles Menefee, 26, was shot to death by the police after a high speed car chase. Questions raised by the Portland chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Albina Ministerial Alliance motivated District Attorney Harl Haas to put the case before a Multnomah County Grand Jury, which again ruled that the shooting was justified. The death of Menefee certainly seems to have been justified, but the sudden frequency of police shootings and the death of three black men at the hands of police raised community awareness and the issue of police accountability became a serious issue for organizing in Portland’s African American community. Charles Menefee had a record for burglary and was most likely up to no good as he cruised the small suburban town of Canby on the night of November 20, 1974. In Canby a black man driving around was considered suspicious in itself and soon the local police approached Menefee’s car. The young man attempted to evade the police and drove north at high speed. It must have been an exciting chase as Canby, Milwaukie, Oregon City, Clackamas County, Portland and State police joined in the pursuit on Highway 99E, up Grand Avenue, across both the Hawthorne and Steel Bridges. By the time the speeding car reached Williams Avenue in Northeast Portland, not far from Menefee’s house, there were fourteen officers involved. Menefee’s car was finally forced out of control near Sacramento Street. Menefee fired at least one shot from a rifle, wounding Portland Officer Kent Perry before dying in a hail of bullets. More than fourteen officers fired dozens of bullets in the exchange of fire and Portland Officer John Murchison was struck by a ricocheting bullet and slightly wounded.

Charles Menefee was probably up to no good the night he died in November, 1974, but the overwhelming violent response to his crimes made Portland's black community nervous. Three black men dead at the hands of the police in one month created a big stir in the African American community. Besides the NAACP and the Urban League a new organization, the Black Justice Committee (BJC) was formed. Charlotte Williams, daughter of Otto Rutherford, an important leader of the NAACP, became the most visible spokesperson for the BJC and soon the host of a weekly Public TV program, Black on Black, focused on issues in the black community. Things cooled down between the police and Portland blacks, but when the next shooting occurred, in March, 1975 the BJC was well organized and vocal about their demands for police accountability. The killing of 17-year-old Rickie Johnson on March 14, 1975 by North precinct officer Ken Sanford combined with Police Chief Bruce Baker’s confrontational stone-walling attitude was the last straw. Johnson, a junior at Washington High School, had obviously fallen in with a bad crowd. His father, Oscar, warned him just weeks before his death that if the police ever caught him they would “blow his brains out.” Any parent of a teenager knows the fear that Oscar Johnson must have felt at the poor choices his son was making, but only an African American parent knows the life threatening danger presented by the police. A danger Rickie Johnson had “no time to learn” according to an Oregonianletter-to-the-editor published in the aftermath of the young man’s death. It started on March 12 when Radio Cab driver Marvin F. Zamzow was called to pick up an order of Chinese food from the Pagoda Restaurant in the Hollywood district and deliver it to a house on North Gantenbein Street. When he arrived a young black man, later identified as Homer Zachery, another Washington High School student, held the door open for the cabdriver with a box of food. Zamzow stepped into the house and Zachery closed the door behind him, guarding it with a baseball bat. Another young man, who was probably Rickie Johnson, pointed a handgun at the driver and demanded money. Zamzow handed over about twelve dollars in cash along with the box of food. The two young men were angry at the small amount of money and ordered Zamzow into a closet where they told him to wait for ten minutes. After Zamzow reported the robbery, Officer Ken Sanford went to the vacant house to investigate and familiarized himself with the layout. Two days later when Zamzow received a call to pick up food at the Pagoda and deliver it to the same house in North Portland he called Officer Sanford. Donning Zamzow’s pants and sweater, Sanford carried a box that looked like it was full of food; it actually contained his pistol which he held through a hole in the back of the box. Zachery again held the door and Rickie Johnson waited inside. Most witnesses claimed there was an unidentified third robber in the house who escaped and wasn’t pursued, but no testimony about a third person appeared after the initial report. According to both Zachery and Sanford, Rickie Johnson pointed a handgun at Sanford’s face. Zachery ran when Sanford displayed his weapon and yelled, “Police. Drop it.” Sanford said that he was “afraid for his life” when he fired two shots. One went into the wall above Johnson’s head, the second entered the back of his skull, passed through his brain and lodged in his cheek. Another officer, hiding nearby, fired a shot at Zachery, who was running through the yard. It was never determined where the third bullet landed, but Zachery surrendered.

Charles Menefee was probably up to no good the night he died in November, 1974, but the overwhelming violent response to his crimes made Portland's black community nervous. Three black men dead at the hands of the police in one month created a big stir in the African American community. Besides the NAACP and the Urban League a new organization, the Black Justice Committee (BJC) was formed. Charlotte Williams, daughter of Otto Rutherford, an important leader of the NAACP, became the most visible spokesperson for the BJC and soon the host of a weekly Public TV program, Black on Black, focused on issues in the black community. Things cooled down between the police and Portland blacks, but when the next shooting occurred, in March, 1975 the BJC was well organized and vocal about their demands for police accountability. The killing of 17-year-old Rickie Johnson on March 14, 1975 by North precinct officer Ken Sanford combined with Police Chief Bruce Baker’s confrontational stone-walling attitude was the last straw. Johnson, a junior at Washington High School, had obviously fallen in with a bad crowd. His father, Oscar, warned him just weeks before his death that if the police ever caught him they would “blow his brains out.” Any parent of a teenager knows the fear that Oscar Johnson must have felt at the poor choices his son was making, but only an African American parent knows the life threatening danger presented by the police. A danger Rickie Johnson had “no time to learn” according to an Oregonianletter-to-the-editor published in the aftermath of the young man’s death. It started on March 12 when Radio Cab driver Marvin F. Zamzow was called to pick up an order of Chinese food from the Pagoda Restaurant in the Hollywood district and deliver it to a house on North Gantenbein Street. When he arrived a young black man, later identified as Homer Zachery, another Washington High School student, held the door open for the cabdriver with a box of food. Zamzow stepped into the house and Zachery closed the door behind him, guarding it with a baseball bat. Another young man, who was probably Rickie Johnson, pointed a handgun at the driver and demanded money. Zamzow handed over about twelve dollars in cash along with the box of food. The two young men were angry at the small amount of money and ordered Zamzow into a closet where they told him to wait for ten minutes. After Zamzow reported the robbery, Officer Ken Sanford went to the vacant house to investigate and familiarized himself with the layout. Two days later when Zamzow received a call to pick up food at the Pagoda and deliver it to the same house in North Portland he called Officer Sanford. Donning Zamzow’s pants and sweater, Sanford carried a box that looked like it was full of food; it actually contained his pistol which he held through a hole in the back of the box. Zachery again held the door and Rickie Johnson waited inside. Most witnesses claimed there was an unidentified third robber in the house who escaped and wasn’t pursued, but no testimony about a third person appeared after the initial report. According to both Zachery and Sanford, Rickie Johnson pointed a handgun at Sanford’s face. Zachery ran when Sanford displayed his weapon and yelled, “Police. Drop it.” Sanford said that he was “afraid for his life” when he fired two shots. One went into the wall above Johnson’s head, the second entered the back of his skull, passed through his brain and lodged in his cheek. Another officer, hiding nearby, fired a shot at Zachery, who was running through the yard. It was never determined where the third bullet landed, but Zachery surrendered.

Charlotte Williams, daughter of Otto Rutherford, was a prominent activist in the PSU Black Studies Program and became the popular host of Public Broadcasting's Black on Black program. She was the most visible spokesperson for the Black Justice Committee. Community response was instant. Questions about the shooting: Why was he shot in the back of the head? Why wasn’t he given the opportunity to drop the pistol before shots were fired? Inconvenient facts: Johnson had a non-functioning, unloaded weapon; There were seven officers on the scene, most never named, and none pursued the “third suspect". A “blue wall” of resistance to any investigation; a general distrust of the Police Bureau as well as the unsympathetic government of Mayor Neal Goldschmidt; along with a simmering anger in the black community in the aftermath of two uprisings in Albina in 1967 and 1969. All these elements combined to create a legal case that would become a sort of racial Rorschach test for the city of Portland.

Charlotte Williams, daughter of Otto Rutherford, was a prominent activist in the PSU Black Studies Program and became the popular host of Public Broadcasting's Black on Black program. She was the most visible spokesperson for the Black Justice Committee. Community response was instant. Questions about the shooting: Why was he shot in the back of the head? Why wasn’t he given the opportunity to drop the pistol before shots were fired? Inconvenient facts: Johnson had a non-functioning, unloaded weapon; There were seven officers on the scene, most never named, and none pursued the “third suspect". A “blue wall” of resistance to any investigation; a general distrust of the Police Bureau as well as the unsympathetic government of Mayor Neal Goldschmidt; along with a simmering anger in the black community in the aftermath of two uprisings in Albina in 1967 and 1969. All these elements combined to create a legal case that would become a sort of racial Rorschach test for the city of Portland.COMING SOON: PART TWO – Racial Rorschach Testcontent (c) jd chandler

Published on August 24, 2016 16:31

No TIme to Learn

Joe Hopkins won the National Golden Gloves Middleweight Championship in 1963 when he was 17. His pro career was short-lived and the injury-prone boxer was banned by the Portland Boxing Commission in 1971 to prevent further injjury. Something happened to Joe Hopkins. The young boxer, who had been a Golden Gloves champion as a teenager, described by Portland fight promoter, Sam Singer, as “a gentle, simple kid… [without] a mean bone in his body” was suddenly frantic. Convinced that his neighbors had stolen a litter of kittens from his front porch, on the afternoon of October 8, 1974, he began shooting a handgun at their house. A few days later the Portland Boxing Commission insisted that there was no brain damage that could explain his erratic behavior on the day he died, but he had been suspended from boxing the year before for fear of further injury. No one was ever able to explain what happened to Joe. In 1974, before police officers received training in how to deal with people in mental and emotional crisis, they were aware of the problem and they approached the troubled young man carefully. Officer William DeBellis, first on the scene, approached Hopkins on the front porch of his house and tried to talk with him. Hopkins, yelling that he would kill DeBellis if he came any closer ran into his house and slammed the door. DeBellis, and other officers who arrived quickly, kept watch on the house and soon found out that Hopkins had been in treatment at University Hospital’s North Psychiatric Unit. Three officers watched the house while waiting for help to arrive, but none of them noticed when Hopkins slipped out the back door and made his way downtown. Hopkins had been in trouble before; arrested in 1971 for frequenting a gambling house, he had been in and out of the Psychiatric Unit and was currently being supervised by the Metropolitan Public Defenders (MPD) office. From his house he went to the MPD office on SW 5th Avenue, and told them about the confrontation with the police. It is not clear whether his supervisor there knew that he was still armed, but he called the police to report that the young man was there and should be picked up. Hopkins, still very restless, left the office before the police arrived. When Officer Gene Maher arrived at the MPD office, employees pointed out Hopkins walking down the street. Maher and Officer Eugene Francis approached Hopkins, planning to take him into custody. Officer Bruce Harrington watched the three men from a nearby patrol car. Hopkins was still very agitated and he resisted when the two officers tried to arrest him. He pulled a .38 revolver from under his jacket and fired a shot, before Harrington shot him in the chest, killing him instantly. The death of the agitated young black man, the first suspect killed by Portland police since 1971, was considered an inexplicable tragedy, but it was the beginning of a series of shootings that enflamed community feeling and heightened tensions between African-American Portlanders and the police. Over time the shooting of Joe Hopkins would be seen as the impetus for a new round of community organizing that would uncover serious problems within the police bureau.

Joe Hopkins won the National Golden Gloves Middleweight Championship in 1963 when he was 17. His pro career was short-lived and the injury-prone boxer was banned by the Portland Boxing Commission in 1971 to prevent further injjury. Something happened to Joe Hopkins. The young boxer, who had been a Golden Gloves champion as a teenager, described by Portland fight promoter, Sam Singer, as “a gentle, simple kid… [without] a mean bone in his body” was suddenly frantic. Convinced that his neighbors had stolen a litter of kittens from his front porch, on the afternoon of October 8, 1974, he began shooting a handgun at their house. A few days later the Portland Boxing Commission insisted that there was no brain damage that could explain his erratic behavior on the day he died, but he had been suspended from boxing the year before for fear of further injury. No one was ever able to explain what happened to Joe. In 1974, before police officers received training in how to deal with people in mental and emotional crisis, they were aware of the problem and they approached the troubled young man carefully. Officer William DeBellis, first on the scene, approached Hopkins on the front porch of his house and tried to talk with him. Hopkins, yelling that he would kill DeBellis if he came any closer ran into his house and slammed the door. DeBellis, and other officers who arrived quickly, kept watch on the house and soon found out that Hopkins had been in treatment at University Hospital’s North Psychiatric Unit. Three officers watched the house while waiting for help to arrive, but none of them noticed when Hopkins slipped out the back door and made his way downtown. Hopkins had been in trouble before; arrested in 1971 for frequenting a gambling house, he had been in and out of the Psychiatric Unit and was currently being supervised by the Metropolitan Public Defenders (MPD) office. From his house he went to the MPD office on SW 5th Avenue, and told them about the confrontation with the police. It is not clear whether his supervisor there knew that he was still armed, but he called the police to report that the young man was there and should be picked up. Hopkins, still very restless, left the office before the police arrived. When Officer Gene Maher arrived at the MPD office, employees pointed out Hopkins walking down the street. Maher and Officer Eugene Francis approached Hopkins, planning to take him into custody. Officer Bruce Harrington watched the three men from a nearby patrol car. Hopkins was still very agitated and he resisted when the two officers tried to arrest him. He pulled a .38 revolver from under his jacket and fired a shot, before Harrington shot him in the chest, killing him instantly. The death of the agitated young black man, the first suspect killed by Portland police since 1971, was considered an inexplicable tragedy, but it was the beginning of a series of shootings that enflamed community feeling and heightened tensions between African-American Portlanders and the police. Over time the shooting of Joe Hopkins would be seen as the impetus for a new round of community organizing that would uncover serious problems within the police bureau.

The shooting of Joe Hopkins while in a violent psychotic episode in October 1974 was seen as an inexplicable tragedy, but his death was the first in a series of events that led to a new period of community activism in Portland. In 1974 there was little oversight for police shootings. The Homicide Division conducted investigations and often they were cursory. Not since the 1945 shooting of Ervin Jones had there been major controversy or community protest over a police shooting. The shooting of Joe Hopkins was ruled justified because of his earlier violent behavior and his firing a shot while resisting arrest. Just a few weeks later though, the shooting of a second black man raised questions about how the police were being regulated. The second shooting occurred on October 27 and again it involved a young man with a police record. Kenneth “Kenny” Allen, 27, was a familiar figure on the streets of Northeast Portland. Allen, an intravenous drug user, prowled the streets looking for opportunities among the prostitutes, drug dealers and their customers; he had a long arrest record. On the night of his death two undercover police officers, John Hren, 26, and Ed May, 28, were also prowling in an unmarked car looking for prostitutes to arrest. Allen was talking with two women on the sidewalk when he saw the car with two white men pass by. He flagged the car down and asked if the men were looking for drugs. Hren told him they weren’t interested in drugs, but they were looking for women, indicating the women that Allen had been talking to. Kenny said he could take them to a brothel and climbed into the backseat of the car. Allen directed the two undercover officers to an address on N. Congress Street, but when they arrived he produced a handgun and stuck it in Hren’s left ear. He said it was a holdup and he wanted their cash. According to Hren, Allen seemed very nervous and began to pat Hren down, discovering his shoulder holster under his jacket. At that moment, Ed May, who was in the driver’s seat, pulled his weapon and fired at the man in the back seat. Both officers emptied their weapons and then jumped out of the car. Allen, who also went by the name of Kenny Nommo, was hit by six bullets which penetrated several internal organs and killed him within seconds. Hren related a dramatic tale for the Oregonian and Mayor Neal Goldschmidt praised the shooting, implying it was a good idea to shoot the “crazies with guns.” Some felt that the whole story had not been told, but a cursory investigation again ruled that the shooting was justified and there was little community outcry.

The shooting of Joe Hopkins while in a violent psychotic episode in October 1974 was seen as an inexplicable tragedy, but his death was the first in a series of events that led to a new period of community activism in Portland. In 1974 there was little oversight for police shootings. The Homicide Division conducted investigations and often they were cursory. Not since the 1945 shooting of Ervin Jones had there been major controversy or community protest over a police shooting. The shooting of Joe Hopkins was ruled justified because of his earlier violent behavior and his firing a shot while resisting arrest. Just a few weeks later though, the shooting of a second black man raised questions about how the police were being regulated. The second shooting occurred on October 27 and again it involved a young man with a police record. Kenneth “Kenny” Allen, 27, was a familiar figure on the streets of Northeast Portland. Allen, an intravenous drug user, prowled the streets looking for opportunities among the prostitutes, drug dealers and their customers; he had a long arrest record. On the night of his death two undercover police officers, John Hren, 26, and Ed May, 28, were also prowling in an unmarked car looking for prostitutes to arrest. Allen was talking with two women on the sidewalk when he saw the car with two white men pass by. He flagged the car down and asked if the men were looking for drugs. Hren told him they weren’t interested in drugs, but they were looking for women, indicating the women that Allen had been talking to. Kenny said he could take them to a brothel and climbed into the backseat of the car. Allen directed the two undercover officers to an address on N. Congress Street, but when they arrived he produced a handgun and stuck it in Hren’s left ear. He said it was a holdup and he wanted their cash. According to Hren, Allen seemed very nervous and began to pat Hren down, discovering his shoulder holster under his jacket. At that moment, Ed May, who was in the driver’s seat, pulled his weapon and fired at the man in the back seat. Both officers emptied their weapons and then jumped out of the car. Allen, who also went by the name of Kenny Nommo, was hit by six bullets which penetrated several internal organs and killed him within seconds. Hren related a dramatic tale for the Oregonian and Mayor Neal Goldschmidt praised the shooting, implying it was a good idea to shoot the “crazies with guns.” Some felt that the whole story had not been told, but a cursory investigation again ruled that the shooting was justified and there was little community outcry.

Career-criminal Kenny Allen drew little sympathy from the public when he was shot by two police officers. Mayor Neal Goldschmidt characterized him as a "crazy with a gun." Less than one month later another black man, Charles Menefee, 26, was shot to death by the police after a high speed car chase. Questions raised by the Portland chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Albina Ministerial Alliance motivated District Attorney Harl Haas to put the case before a Multnomah County Grand Jury, which again ruled that the shooting was justified. The death of Menefee certainly seems to have been justified, but the sudden frequency of police shootings and the death of three black men at the hands of police raised community awareness and the issue of police accountability became a serious issue for organizing in Portland’s African American community. Charles Menefee had a record for burglary and was most likely up to no good as he cruised the small suburban town of Canby on the night of November 20, 1974. In Canby a black man driving around was considered suspicious in itself and soon the local police approached Menefee’s car. The young man attempted to evade the police and drove north at high speed. It must have been an exciting chase as Canby, Milwaukie, Oregon City, Clackamas County, Portland and State police joined in the pursuit on Highway 99E, up Grand Avenue, across both the Hawthorne and Steel Bridges. By the time the speeding car reached Williams Avenue in Northeast Portland, not far from Menefee’s house, there were fourteen officers involved. Menefee’s car was finally forced out of control near Sacramento Street. Menefee fired at least one shot from a rifle, wounding Portland Officer Kent Perry before dying in a hail of bullets. More than fourteen officers fired dozens of bullets in the exchange of fire and Portland Officer John Murchison was struck by a ricocheting bullet and slightly wounded.

Career-criminal Kenny Allen drew little sympathy from the public when he was shot by two police officers. Mayor Neal Goldschmidt characterized him as a "crazy with a gun." Less than one month later another black man, Charles Menefee, 26, was shot to death by the police after a high speed car chase. Questions raised by the Portland chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Albina Ministerial Alliance motivated District Attorney Harl Haas to put the case before a Multnomah County Grand Jury, which again ruled that the shooting was justified. The death of Menefee certainly seems to have been justified, but the sudden frequency of police shootings and the death of three black men at the hands of police raised community awareness and the issue of police accountability became a serious issue for organizing in Portland’s African American community. Charles Menefee had a record for burglary and was most likely up to no good as he cruised the small suburban town of Canby on the night of November 20, 1974. In Canby a black man driving around was considered suspicious in itself and soon the local police approached Menefee’s car. The young man attempted to evade the police and drove north at high speed. It must have been an exciting chase as Canby, Milwaukie, Oregon City, Clackamas County, Portland and State police joined in the pursuit on Highway 99E, up Grand Avenue, across both the Hawthorne and Steel Bridges. By the time the speeding car reached Williams Avenue in Northeast Portland, not far from Menefee’s house, there were fourteen officers involved. Menefee’s car was finally forced out of control near Sacramento Street. Menefee fired at least one shot from a rifle, wounding Portland Officer Kent Perry before dying in a hail of bullets. More than fourteen officers fired dozens of bullets in the exchange of fire and Portland Officer John Murchison was struck by a ricocheting bullet and slightly wounded.

Charles Menefee was probably up to no good the night he died in November, 1974, but the overwhelming violent response to his crimes made Portland's black community nervous. Three black men dead at the hands of the police in one month created a big stir in the African American community. Besides the NAACP and the Urban League a new organization, the Black Justice Committee (BJC) was formed. Charlotte Williams, daughter of Otto Rutherford, an important leader of the NAACP, became the most visible spokesperson for the BJC and soon the host of a weekly Public TV program, Black on Black, focused on issues in the black community. Things cooled down between the police and Portland blacks, but when the next shooting occurred, in March, 1975 the BJC was well organized and vocal about their demands for police accountability. The killing of 17-year-old Rickie Johnson on March 14, 1975 by North precinct officer Ken Sanford combined with Police Chief Bruce Baker’s confrontational stone-walling attitude was the last straw. Johnson, a junior at Washington High School, had obviously fallen in with a bad crowd. His father, Oscar, warned him just weeks before his death that if the police ever caught him they would “blow his brains out.” Any parent of a teenager knows the fear that Oscar Johnson must have felt at the poor choices his son was making, but only an African American parent knows the life threatening danger presented by the police. A danger Rickie Johnson had “no time to learn” according to an Oregonianletter-to-the-editor published in the aftermath of the young man’s death. It started on March 12 when Radio Cab driver Marvin F. Zamzow was called to pick up an order of Chinese food from the Pagoda Restaurant in the Hollywood district and deliver it to a house on North Gantenbein Street. When he arrived a young black man, later identified as Homer Zachery, another Washington High School student, held the door open for the cabdriver with a box of food. Zamzow stepped into the house and Zachery closed the door behind him, guarding it with a baseball bat. Another young man, who was probably Rickie Johnson, pointed a handgun at the driver and demanded money. Zamzow handed over about twelve dollars in cash along with the box of food. The two young men were angry at the small amount of money and ordered Zamzow into a closet where they told him to wait for ten minutes. After Zamzow reported the robbery, Officer Ken Sanford went to the vacant house to investigate and familiarized himself with the layout. Two days later when Zamzow received a call to pick up food at the Pagoda and deliver it to the same house in North Portland he called Officer Sanford. Donning Zamzow’s pants and sweater, Sanford carried a box that looked like it was full of food; it actually contained his pistol which he held through a hole in the back of the box. Zachery again held the door and Rickie Johnson waited inside. Most witnesses claimed there was an unidentified third robber in the house who escaped and wasn’t pursued, but no testimony about a third person appeared after the initial report. According to both Zachery and Sanford, Rickie Johnson pointed a handgun at Sanford’s face. Zachery ran when Sanford displayed his weapon and yelled, “Police. Drop it.” Sanford said that he was “afraid for his life” when he fired two shots. One went into the wall above Johnson’s head, the second entered the back of his skull, passed through his brain and lodged in his cheek. Another officer, hiding nearby, fired a shot at Zachery, who was running through the yard. It was never determined where the third bullet landed, but Zachery surrendered.