Elliott Hall's Blog

July 14, 2015

Canton: The European Reservation

Cross-posted from Unbound, where the Devil and the Hindmost needs your support to be published.

Working abroad was a very different prospect in the age of steam. Circumstances had vastly improved since the beginning of the century: steamships were much faster and more reliable than the packets that had relied on the fickle winds. The expanding telegraph network allowed communications to be measured in days rather than weeks. Yet the best recorded time between Southampton and Calcutta in 1856 was 37 days, and there was still no telegraph link between Canton and Hong Kong, which meant despatches had to travel the last mile by boat. For all the dramatic shrinking of the world that happened in the middle of the 19th century, it was still a very big world indeed.

Noah, the hero of the Devil and the Hindmost, is sent forth from England to make his fortune. The irony of his great adventure, and all those who went to work in the Far East at that time, was that his world-spanning journey ended with him confined to a space smaller than the Northern village where he grew up.

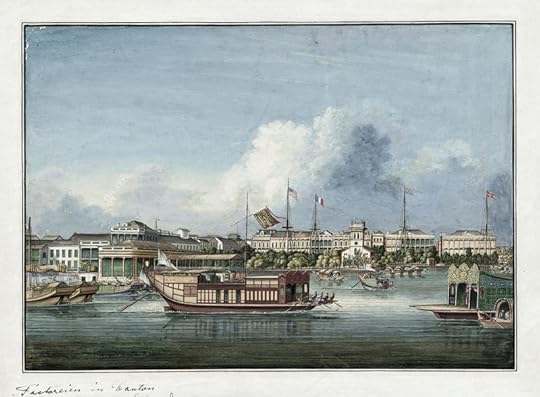

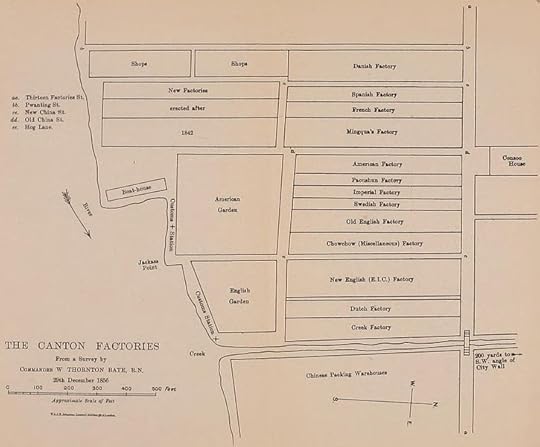

Imperial China had always sought to manage contact with Europe as one would an infectious disease. At the beginning of the 19th century, Westerners were permitted only on a thin strip of waterfront outside the walled city of Canton (actually Guangzhou, but the British preferred to use a Portuguese word rather than the Chinese name.) All trade was conducted through a guild of merchants, the Hong. Westerners were forbidden from going anywhere else in China, or even bringing their families with them to Canton.

The Europeans lived and worked in the thirteen factories, divided by nationality. The factories were more properly warehouses, two stories high on the waterfront, three in the rear. Inside, they were divided into contiguous apartments, storerooms, and offices. Merchants and their clerks slept on either hard rattan mats or mattresses filled with bamboo shavings. The bigger factories had billiard rooms and libraries, but beyond them and the two tiny gardens, diversion was in short supply. The foreign district was tiny – one resident estimated the whole sector as approximately 270 steps East to West, and even less North to South. Leaving this European reservation , or trying to enter Canton itself, was forbidden on pain of death.

The First Opium War changed this peculiar arrangement. The British seized Hong Kong, and other ports were opened by the treaty that ended the war. Yet when Noah arrives in 1856, the gates of Canton remained closed to Westerners, who were still confined to their factories and forbidden on pain of death from travelling inland. This threat by the Qin was not an idle one: missionaries regularly flouted it in their pursuit of souls, and were as regularly executed for the transgression. To work in the factories of Canton in 1856 was to be confined to an industrial estate on the other side of the world, surrounded by people whose language you could not understand.

It was no surprise then how much hostility there was around this little European nature preserve. Most of the businessmen and officials were there only for the money, felt themselves superior to every Chinese no matter their rank within their own society, and were anxious to leave as soon as possible. They regarded the closed gates of Canton as a personal affront from lesser beings. The Chinese, for their part, considered their English trading partners uncultured barbarians, arrogant and dangerous. This mutual contempt was kept in check by mutual greed for a time. But the British knew their strength, and when the Qin refused to open the country to further trade, Her Majesty’s servants decided to accomplish it by force.

February 9, 2015

The Devil and the Hindmost

I am currently funding my new book, the Devil and the Hindmost, at Unbound.

I’ll be cross-posting between here and the Shed blog. It’s an experiment I’m really excited about. Most books are published on bets made two steps from the action – an editorial and sales team both punting on the possibility that someone will read what they’re publishing. It leads to a very conservative mindset and misses a lot of good books and readers lost in the race for those few, massive hits. Unbound asks the important person in this equation – the reader – directly whether this book is something they’re interested in.

I released the Strange Trilogy out into the wild, and then the only record I had of my readers were royalty statements that would baffle a theologian. With Unbound, I hope I can at least meet more of the people who are reading The Devil and The Hindmost.

So I’d be grateful if you went over and checked out the synopsis and excerpt, and if you should happen to trip over one of the pledge buttons…

June 26, 2014

The Strange Files Out Today

Hodder released The Strange Files today, an omnibus edition of the Strange Trilogy with the Fall and a brand new story, The Promised Land.

As part of the bundle I wrote a few articles about where the inspiration for the trilogy came from, and how things have and haven’t changed since I finished The Children’s Crusade almost five years ago. Then ISIS invaded northern Iraq and what I’d written became accidentally prescient.

The campaign of outright fabrication that led to the invasion of Iraq haunts the conscience of the UK and the US, a shadow that rightfully hangs over both nations when viewed by the rest of the world. But it also haunts us in a more literal form: the war criminals and their enablers are still part of the respectable establishment, still talking about what we should do about the country they threw against the wall and then pretended had put itself back together.

Paul Bremer, the viceroy of the Green Zone and the man responsible for disbanding the Iraqi army, is being given space in The Wall Street Journal. Tony Blair and Dick Cheney are on TV, and not in live updates from The Hague where they belong. They blame the current president for their own crimes and mistakes, which in any civilised world would have resulted in ostracism if not prison. Every hack and apparatchik from those bad years has come crawling out of the woodwork, so far from repentance that they won’t even recognise they were wrong in the first place.

It is this weaponised self-delusion that formed the core of Strange’s world. The foundations of democracy in America were relentlessly undermined by a clique that did not believe the peasants had a right to question their foreign adventures. The Neocons belief in an Imperial Presidency opened the door to authoritarianism, but in my world it was their allies, the Religous Right, that seized power and stepped through. The laws and powers they had created so the president had an unlimited scope to wage war were turned against the American people.

Cheney and his thinktank spawn may have been pushed to the margins during the Obama years, but they are still there, still pushing on that door. Unless they face the consequences of their actions, sooner or later it will open.

June 25, 2014

Big Brother has Always Known You

My blog about surveillance, state oppression and puppies is up at Hodderscape:

By carrying around GPS-enabled smartphones, we are effectively spying on ourselves, a Stasi for a GDR of one. We ignore this fact most of the time, because the present convenience of not getting lost outweighs the potential harms of this self-surveillance in the future.

The surveillance program that forms part of The Promised Land was inspired by the actual NYPD Intelligence Division’s Muslim Surveillance Program. Hundreds of Americans in New York and New Jersey were secretly filmed and spied upon by the police solely because they were Muslim, the unit going so far as placing moles in mosques to keep tabs on what was being said.

Read the whole thing, etc.

May 11, 2014

Bleeding Edge

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I always have the highest of expectations for any Pynchon novel. He has been a massive influence on me: The Crying of Lot 49 helped me figured out what I wanted to write. He is the master of literary pulp, blending the two in a way I have tried but failed to do.

This weight of expectation has the accidental effect of making me an unusually harsh critic, which I’ve tried to counterbalance a bit here. This is an incredible book, and if I say I didn’t like it as much as Inherent Vice, it’s only because I love that book so much.

The post-crash, pre-9/11 New York of Bleeding Edge is one I’m a little familiar with from visits during that time. Pynchon’s recreation of the time is almost pathological in its accuracy, with its Zima and Kozmo jokes (I remember my brother telling me about them with a shake of the head; everyone thought it was crazy even when they were in business) and web that now seems almost quaint in retrospect. It is playful, very funny, and dense in the best possible way: there are so many interesting things on each page I know I’m always missing at least half of what is going on.

I think it cast less of a spell than Inherent Vice because I actually remember that time. Wandering around in Pynchon’s painstaking recreation had an uncanny valley effect, whereas his sixties California was to me pure fantasia, a world I’d visited only through other people’s stories.

The book explores that penumbra between myth and reality, fact and belief, using conspiracy theory, espionage and the deep web. Being a Pynchon novel it promises no answers; the lack of any effective resolution is one of its points. If Inherent Vice was his noir, this is his paranoid thriller, and both excel at turning the rules of their respective genres in on themselves.

There is a famous Ross Suskind interview where a Bush aide calls their opponents “The Reality-based Community” and says that, as an empire, they made their own reality now. This withdrawal into magical thinking is an idea I’ve long been fascinated with: it was one of the reasons I wrote The Strange Trilogy. New York of that time is the fracture point, the crack in the ice of reality that spreads and spreads throughout the decade to come. Pynchon depicts this unraveling with incredible wit and a sort of dry terror: not the screaming, paranoid fear of 24, but a queasy feeling in the pit of the stomach, that after 9/11 nearly any nightmare is possible.

View all my reviews

April 26, 2014

Belated thoughts on speaking with Brian Aldiss

Despite being badly under the weather, I had a great time speaking with Brian Aldiss at the Idler on Tuesday. We had a great turnout and nobody threw anything, so I think they enjoyed themselves.

Brian and I turned into an accidental double act: I was Lemsipped up to the eyeballs and giving short, focused answers to make sure I was coherent, while he was wandering around whatever question he was asked, though always being very entertaining.

It was a great honour to meet a writer as talented as him (read Greybeard if you haven’t) but it is the sheer breadth of his career that is really startling. He’s 89 this year, and The Friday Project will be putting out stories he wrote when he was 14. He explained the origin of several of his best-known works that evening, from Greybeard to the Helliconia trilogy and many others, and I couldn’t count the number of times he said of various books “the agent didn’t think it would sell” or “I left it in a drawer for ten years” etc. Yet he kept writing through it all, and still is.

It’s an easy thing to forget in our goldfish-memory culture, where someone can be massive, the butt of “where are they now?” jokes, and then forgotten with blinding speed. Almost all artists are discovered, forgotten, (re)discovered, and then fall out of fashion once more. The only real marker of success is that you’re still doing it, whether anyone is paying attention or not.

April 1, 2014

Social media addiction, writing, and the importance of boredom

There was an interesting piece on the last Newsnight about social media addiction. It was thankfully not sensational, but tried to look at the existing scientific evidence, especially how the brain’s reward areas being stimulated by likes/retweets etc. might cause addictive behaviour. It’s not a crazy idea, since that’s exactly what happens to gamblers, who are addicted to a specific behaviour that has no physical chemical component. The evidence is still too sparse to make any informed decision.

What interested me was less the addiction question than the social media behaviour breaks up something essential to my work: boredom. There is always another post to read, another picture to laugh at, something to like or retweet or comment on. Then of course your own contributions are skipped along and reflected back. It is the reason it is so appealing to people, and why it’s dangerous to writing.

Writing requires long, blank mental spaces, and it is a part of the work few of us enjoy. Hang around writers long enough (five minutes) and someone will complain about the crazy-making effects of the blank page. Yet it is a necessary pain, and leads to the most remarkable thing about our work: the wrestling of people, of whole worlds, into being though sheer force of will.

Yet, now that all writers are supposed to be social media experts, we are expected to stay connected to this vast sea of distraction. It’s a balance that isn’t easy to strike. For now I keep them separate, closing everything down except my work, knowing my brain will run for the first shiny object it sees to escape the empty space I’m forcing it to be in.

So, instead of staring at my browser, I stare out the window.

February 21, 2014

Alone in Berlin, by Hans Fallada

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Fallada’s book begins when the Nazis are at the height of their power: France has surrendered, and the English expeditionary army has been thrown into the sea. The worst of German society is now ascendant. In the Quangel’s apartment block they take the form of the Persickes,a working-class family headed by a drunk tavern keeper, have through their membership in the party been elevated to positions, especially their poisonous son Baldur who is tipped for great things in the Hitler Youth. The portrait Fallada paints of a society utterly corrupted by violence and betrayal is as horrifying as it is compelling.

We want the good guys to win. Even more than true love or great adventure, the idea of good triumphing over evil is part of the wish fulfilment of literature. The problem is that this relentless parade of unusual stories can lead you to think that good winning is the rule, not the exception. In Fallada’s Berlin, resistance against the Nazis feels not just doomed, but quixotic.

Yet the novel is almost as redemptive as it is harrowing (and that “almost” is one of its most interesting parts.) It is ultimately about the cost of preserving your dignity in the face of overwhelming evil, and the Quangel’s story is more powerful than a hundred pat tales of heroes overcoming obstacles we already know will fall.

View all my reviews

November 7, 2013

The Fall, and when the dystopia comes to you

A while ago I wrote a short story set in the Strange world called The Fall. You can now read it for free on Hodderscape today.

The premise is that a woman is indicted for murder when she has a miscarriage after falling down a flight of stairs. It takes place in an America that has been governed by religous fundamentalists for several years, where a fetus is now a person under law. The extremists I was writing about propose these laws all the time as a way of making abortion illegal. When I wrote The Fall I thought I was extending that thinking to its predictably ludicrous conclusion, where every miscarriage would have to be investigated just as every death was, to determine if there was foul play.

Then they go and call my bluff.

The man who may be the next Attorney General in Virginia, Mark Obershain (The result is so close there may be a recount), once tried to do this:

Outrageously, Mr. Obenshain sought to force women to report miscarriages to the authorities. His explanation — that he was doing the bidding of a prosecutor who sought to protect newborn babies and that he withdrew the bill when he grasped its flaws — casts doubt on his basic legal competence and qualification for the office he now seeks.

Maybe I should sue.

October 31, 2013

Next week is Strange Week on Hodderscape

I’m delighted that next week there will be a series of posts about The Strange Trilogy over at Hodderscape. There will be a post by me on noir and science fiction, a Strange short story plus a discussion about dystopias by the Hodderscape team.

So stop by Hodderscape next week for all your noir dystopia needs. You know you have them.