Wynton Marsalis's Blog

October 13, 2025

Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis to premiere “Wave the Wheat Suite” honoring 15 KU icons

LAWRENCE, Kan. — The Lied Center of Kansas has commissioned the world-renowned Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis (JLCO) to compose a new work, “Wave the Wheat Suite,” which will be premiered at the Lied Center on Nov. 6, 7:30 p.m. The 15 movements in the suite, each composed by a different JLCO member, capture the spirit of 15 seminal figures throughout KU’s history, acknowledging great accomplishments in a variety of fields and athletics.

“Wave the Wheat Suite” is the second original work the Lied Center has commissioned of the JLCO. The first, Rock Chalk Suite, honored 15 KU basketball legends and premiered at the Lied Center in 2018, with a recording that was released in 2020. “Rock Chalk Suite” was the first time JLCO was commissioned to create a new work as a collective.

“We are so excited to build upon the incredible success of ‘Rock Chalk Suite’ with another musical work celebrating 15 KU luminaries in collaboration with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis. The KU legends who inspired this work range from a Nobel Prize winner and astronaut to a four-time Olympic Gold Medalist and founding member of the LPGA. The best part of the project is that sponsorship proceeds will establish an endowed fund to cover bus costs for Lawrence Public School students to attend age-specific performances annually at the Lied Center for free, in perpetuity—something that is truly unique to our community,” said Lied Center Executive Director Derek Kwan.

Each movement is sponsored by individual donors, and the KU legends highlighted in the suite are:

KU HONOREES, COMPOSERS AND MOVEMENT SPONSORS

Ochai Agbaji (men’s basketball); movement composed by Abdias Armenteros; sponsored by Jon & Vicki Jamison Jim Bausch (men’s track & field, football); movement composed by Marcus Printup; sponsored by an anonymous donor in honor of Tom Rupp Ray Evans (football, basketball); movement composed by Victor Goines; sponsored by Janis Bulgren Barney Graham (vaccine pioneer, immunologist, virologist and clinical-trials physician); movement composed by Alexa Tarantino; sponsored by KU’s Office of the Chancellor John Hadl (football); movement composed by Paul Nedzela; sponsored by Steve & Chris Edmonds Ainise Havili & Kelsie Payne (volleyball); movement composed by Dan Nimmer and arranged by Sherman Irby; sponsored by Martha Gage in honor of Ralph Gage Frank Mason III (men’s basketball); movement composed by Elliot Mason; sponsored by Dr. Larry Weeda Jr. & Sharon L. Polk John McLendon (men’s basketball coach, Naismith Hall of Famer, inventor of the fast break); movement composed by Vincent Gardner; sponsored by John & Rosy Elmore Billy Mills (men’s track & field); movement composed by Kenny Rampton; sponsored by Dave & Libby Domann Al Oerter (men’s track & field); movement composed by Chris Crenshaw; sponsored by Bill & Marlene Penny Loral O’Hara (NASA astronaut); movement composed by Sherman Irby; sponsored by Dr. Jim & Vickie Otten Juan Manuel Santos (former President of Colombia, Nobel Peace Prize winner); movement composed by Carlos Henriquez; sponsored by Jeff & Mary Weinberg Gale Sayers (football); movement composed by Wynton Marsalis; sponsored by Beverly Smith Billings in honor of Bob Billings Marilynn Smith (women’s golf); movement composed by Obed Calvaire; sponsored by an anonymous donor in honor of Sue Mango Marian Washington (women’s basketball coach); movement composed by Chris Lewis; sponsored by Miles & Paula SchnaerLed by Managing/Artistic Director and nine-time Grammy-winner Wynton Marsalis, the JLCO comprises 15 of the finest jazz soloists and ensemble players today. The group has been the resident orchestra of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City (Frederick P. Rose Hall, “The House of Swing”) since 1988, and the orchestra spends over a third of the year on tour across the world.

Tickets to the world premiere of “Wave the Wheat Suite,” composed and performed by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis, on Nov. 6 can be purchased at lied.ku.edu or the Lied Center Ticket Office.

October 1, 2025

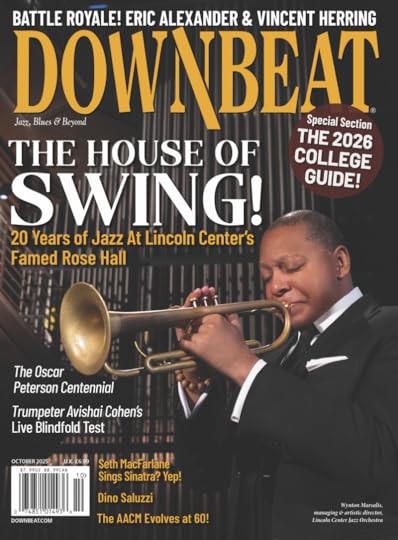

The House That Jazz Built

Cover image: Downbeat October 2025

20 years after the launch of Rose Hall, Home to Jazz At Lincoln Center

“People are still swinging in the United States of America!”

With those telling words, Wynton Marsalis closed the first of two concerts that, on consecutive June nights, brought to a rousing and defiant end the 20th season of Rose Theater — the most jazz-centric concert hall in New York.

Declaiming from a top-tier seat on an onstage platform — his chair, that is, in the trumpet section of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra — Marsalis, who in addition to his playing role is JALC managing and artistic director, delivered his message with the authority of an exalted member-cum-leader of the band.

Even before the October 2004 opening of the theater and its sister stages, the Appel (then Allen) Room and Dizzy’s Club — a landmark event that gave Lincoln Center jazz a brick-and-mortar home on par with those of the center’s other performing arts — Marsalis enjoyed the status of a singular cultural figure.

Then, as now, he has deployed the attendant power strategically, by turns absorbing and repelling the slings and arrows that come with occupying the most visible leadership position in a fractious field of artistic endeavor. But he has also been remarkably resolute in maintaining his programming vision.

And what, in essence, is that vision?

“Actual jazz,” he asserted during a March interview. “Swinging, playing the blues, being able to improvise on changes and form: actual jazz music. That’s the genre we need to concentrate on.”

While Marsalis offers a view of an art form whose definition is eternally up for debate, his achievement is not. As the Frederick P. Rose Hall’s three stages enter their third decade — and the jazz project at Lincoln Center nears its fifth — the institution remains vibrant and prepared to take on the future, even at a time when the slings and arrows are coming from new directions.

For evidence of the institution’s vibrancy — and of the Marsalis programming philosophy in action — one need look no further than that June concert. Playing to a packed house, the concert, tagged with the deceptively banal banner Best of the JLCO, was a stylistic smorgasbord that, for all its diversity, had the crowd’s heads bobbing in unison.

The offerings impressed, from the opening tune, a piquant mambo-and-guajira-traversing “Two-Three’s Adventure” by the prolific JLCO bassist Carlos Henriquez, to the closer, JLCO trombonist Vincent Gardner’s delectably disorienting “Up From Down.” Equally impressive was the sense of thematic unity, each of the 11 numbers on the program serving up a distinct but authentic flavor of swing.

When in the middle of the program Gardner suddenly appeared as vocalist, on JLCO saxophonist Sherman Irby’s sly throwback of a take on the century-old “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby,” the contrast with the fiercely contemporary material surrounding it only highlighted swing’s range of expression. That the arrangement was cooked up casually and was now a durable part of the JLCO book was no surprise, according to Gardner.

“We have so much faith in just what the music is about that you can do things on the fly,” he said in a post-concert Zoom interview. “Anything within the jazz context has a chance to be appealing to anybody at any time.”

Broad appeal is a factor in programming artists at a 1,200-seat theater like the Rose. But even with an exceptional donor base — and guest musicians occasionally willing to work for a reduced fee, according to Marsalis — merely filling seats is not enough to keep the boat afloat.

“We pretty much have always had a break-even budget,” Marsalis said. “We have to work, we have to make money, we have to raise money — what all institutions do and should have to do.”

As an independent corporation within Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, JALC, according to Lincoln Center VP of Programming Jordana Leigh, must raise the “very big bulk” of its own funds. So architects designed a theater space flexible enough to attract non-jazz events and generate revenue from them. An adjustable orchestra pit and multiple onstage seating towers, for example, allow seating to be added or reconfigured depending on an organization’s needs.

The theater’s relative intimacy facilitates the performance of jazz but also of other types of presentations; no seat in the house is more than 90 feet from the stage. More salient to jazz audiences may be the acoustical feature that affords the bass unusual clarity.

Of course, the most jazz-friendly aspect of the theater remains the roster of artists, and it casts a surprisingly wide net. Some are even outside the jazz orbit. But no matter where artists come from, they will, once committed to rehearsing and performing with the JLCO, be meeting jazz more than halfway — consenting, in effect, to a merging of styles that consists of an orchestra member writing a jazz arrangement of his music, according to Jason Olaine, JALC vice president of programming.

“In an ideal sense,” Olaine said as he sat in a Rose Theater dressing room on a June aernoon, “it’s not jazz reaching out to other genres but other genres coming to jazz.”

JLCO trumpeter Marcus Printup, standing outside the JALC West 60th Street stage door during a break one mild day in July, recalled a 2011 gig in which Eric Clapton was collaborating on a show with an ensemble drawn from players inside and outside the orchestra. The guitar king of swinging ’60s London, Printup said, had admitted, during the days of pre-concert preparation, to being “nervous.”

But once Clapton and the band launched into his “Layla,” any jitters seemed to subside. While Marsalis’ arrangement bore little resemblance to Clapton’s standard hard-driving rendition — it opened cacophonously before yielding to a steamy dirge straight out of New Orleans — it gave a jazz voice to Clapton’s blues-tinged theme of unrequited love, and he adjusted seamlessly.

Another classic-rock guitarist, Steve Miller, has developed an ongoing relationship with JALC. Introduced to Marsalis by Olaine, who engaged him in conversation aer spying him in the Dizzy’s audience, Miller has since taken the Rose stage at least six times. Though specializing in the blues — Miller is developing a course on the subject for JALC — he is scheduled for a November concert celebrating Eddie Harris and Chico Hamilton. He has grown so tight with JALC o&cials that he now sits on the Board of Trustees.

That development has sparked interest but hardly eclipsed the buzz created when, in a 2006–07 season otherwise marked by an a&rmation of the JALC identity — it retired the “Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra” moniker — avant-garde icons Cecil Taylor and John Zorn crashed the House of Swing in a double bill and, on another night, Joe Zawinul, in a concert titled Fusion Revolution, rocked the bank of synthesizers he famously used to great effect with Weather Report.

This year, Weather Report material surfaced in a May concert, titled JLCO Plays the ’70s, that included Zawinul’s hit “Birdland.” Arranged by JLCO trombonist Chris Crenshaw, the newly expanded version deepened the already rich palette of the original and, powered by Irby’s eerie evocation of Wayne Shorter’s soaring soprano saxophone, recalled its electrifying sound and feel.

Similarly charged programming has intermittently popped up in the smaller venues. In the Appel (then Allen) Room — whose steep, flexible seating of up to 500 and panoramic view of Manhattan invite audaciousness — an interactive presentation in 2013 featured the Sun Ra Arkestra complete with real-time digital projections and cartwheeling acrobats. Olaine likened it to a “threering circus.”

Six years later, trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith brought to the room his suite America’s National Parks — a sprawling work that might not have met the letter of Marsalis’ “actual jazz” (Smith once told this writer, with little apparent irony, that he “never played a change”) but, in its searing impression of the American landscape, captured the yearning for freedom inherent in the spirit of jazz.

This past June, in the 140-seat Dizzy’s, Immanuel Wilkins went even further afield with his striking new suite for saxophone and string quartet, Ethnic Cleansing–An American Tradition. Chatting before the performance, the alto player noted that the work, a collaboration with Poland’s Lutoslawski Quartet conceived in the mode of 12-tone classical composition, was a risk for both him and the venue.

“It’s going to be interesting how it lands,” he said as he busily organized the extensive score on his music stand. He need not have worried; the music landed well, though, apart from an improvised cadenza of Wilkins’ that had the logical development if not the fully syncopated rhythm for which he is known, it fell outside even the broadest definition of jazz performance. Such presentations are infrequent enough to qualify as exceptions. And while they certainly lend credence to Olaine’s argument that “we’re less quote-unquote conservative than people think we are,” some exceptions, he acknowledged, could be a bridge too far: “Maybe we’re not going to see the blend of hip-hop or neo-soul with jazz.”

Whatever the programming limits, he ventured, “Jazz at Lincoln Center is presenting a lot of diversity within the jazz canon.” In the realm of trumpeters alone, the programming routinely mines a long lineage of players, from Louis Armstrong to Roy Eldridge to Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and, well, plenty of Marsalis.

But arguably no one better embodies the JALC ethos than pianist Bill Charlap, whose choice was a “no brainer” when, in 2004, the organization was seeking the person to open Dizzy’s, said Roland Chassagne, the club’s general manager and a member of the team that, 25 years ago, developed the JALC complex.

Nursing a glass of water in Dizzy’s on a June afternoon, Chassagne elaborated: “I will sum up Bill Charlap in two words — unapologetic swing. He swings so hard and he’s so dedicated to jazz music and swing in general on a spiritual level that it made tremendous sense.”

Charlap, who was honored at the JALC gala in 2024, has since that festive opening day directed at least seven shows for JALC. The shows, on all three stages, have explored subjects ranging from the birth of the cool to great American songwriters.

As far as it goes, Chassagne’s Charlap profile is accurate. But, along with his hard swing and faithfulness to form, Charlap’s choice of interpretive devices and the spontaneity with which he employs them at the piano can be as breathtakingly radical as, say, Taylor. He thus seems predisposed toward skepticism about siloing in the jazz community.

“It’s silly it should get so fractious because ultimately it’s not like that,” he said in a phone interview. “I really don’t think that the factions are so divided as people think — not within the family of musicians.”

Silly or not, a certain self-segregation persists, with more-overtly “experimental” players and their audiences often gravitating toward venues that, compared with those of JALC, are less opulent and more dedicated to their styles.

For others, though, JALC is, as younger musicians in the band call it, “the fort”: a guardian of classic works, yes, but also a conduit for new ones, some so distinctive they become part of the canon. Darcy James Argue’s hyperkinetic dance number “SingleCell Jitterbug,” performed at a JLCO concert in April confidently titled Contemporary Jazz Masterpieces, may be one.

In a few cases, canonization can co-exist with subversion of at least some elements of “actual jazz.” Ornette Coleman, who upended harmonic orthodoxy, nonetheless donned a hard hat and, like Charlap and Tony Bennett, was invited for a rare tour of the JALC complex while it was being built. He was inducted into the JALC’s Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame in 2008, played a greatest-hits set at Rose Theater in 2009 and received a JLCO retrospective in 2018.

“I would consider him a mainstream artist for us,” Chassagne said, “just because of his commitment to jazz music his entire life.”

As the canon grows and morphs, so does the JALC brand. And as it does, collaborations with other Lincoln Center arts groups have perhaps become less urgent, if no less of an occasion. (Details of a major one being planned are, as of this writing, embargoed.)

Precisely what all that portends for JALC programming is an open question. Looking beyond his tenure, the 63-year-old Marsalis noted: “It’s going to be up to the younger musicians now to determine that. They’re going to define what it is going into the future, and how they choose to deal with it in the halls.”

One musician he looked to was 25-yearold drummer Domo Branch. A JLCO sub, Marsalis small-group sideman and community activist, Branch has joined the JALC artist advisory council and written an essay in the organization’s 2024 annual report. In it, he identified a “new dimension for jazz,” which, in a July interview, he clarified as a post-pandemic, post-George Floyd generational shi from “singing about love” to reflecting “a lot of pain.”

“Jazz at Lincoln Center,” he said, “has an opportunity to truly show their integrity, an opportunity to truly show what they are about. In these times, you have to show that you don’t bend and break.”

If in these times democracy is bending under pressure, it is, in JALC corridors, unbroken. A Rose Theater rehearsal the day before the JLCO’s first-ever late-July concert, Reflections on Africa, proved a model of democratic process as Irby, front and center in the saxophone section, waved a hand to lead the band through the lush opening of Randy Weston’s “Bantu.” Trombonisttubist Gardner, the concert’s designated music director, refereed the ample giveand-take. And bassist Henriquez offered supportive commentary paralleling his role as musical anchor.

The rehearsal offered a glimpse of how the band might function post-Marsalis, as well as of the upcoming season, themed Mother Africa. “Bantu” was heavily invested in authentic African grooves supplied by guest percussionists Iyedun Ince and Chief Baba Neil Clarke (who played with Weston). But in the melding of those grooves with the jazz influences in the Melba Liston chart, more than a hint of Marsalis lingered.

Henriquez, chatting during a rehearsal break, noted the leader’s impact. While Marsalis’ “musical ideology can be subjective,” Henriquez said, his single-minded codification of the jazz classics had helped cement their standing among the wider public. And he had done so against the run of play.

“Everybody’s trying to push the envelope,” Henriquez said. “He’s trying to do the preservation, which is the hardest part.”

In fact, Marsalis’ preservationist instinct and provocative pen have combined to push against cultural amnesia and create something new. From his Blood On The Fields to The Ever Fonky Lowdown, he has over the past 30 years drawn a direct line from works like Duke Ellington’s Black, Brown And Beige: fashioning the most potent critiques from the stuff of swing and expanding its scope.

He has also beat the system in a business sense, marshalling an improbably diverse set of New York players and driving to unlikely completion — from concert series to co-equal constituent of Lincoln Center — a visionary jazz institution.

Speaking by phone, Bob Mintzer, chief conductor of Germany’s WDR Big Band, praised the JLCO for its sound, to be sure, but also for its organization: one, common in Europe but lacking stateside, in which a jazz orchestra functions like a symphony orchestra, with a season and a steady job for all its musicians.

Great things can happen when you have that situation,” he said.

Great things have happened, but Marsalis takes it all in stride.

“For us,” he said, “it was a public service.”

By Phillip Lutz

Source: Downbeat (October 2025)

August 25, 2025

Wynton Marsalis to Premiere New Work, ‘Afro!,’ to Open Jazz at Lincoln Center’s ‘Mother Africa’ Season, Followed by Tour

Jazz at Lincoln Center launches its Mother Africa season with the world premiere of Afro!, a new commission by Managing and Artistic Director Wynton Marsalis, on Sept. 18–20 at 7:30 p.m. in Rose Theater at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s home, Frederick P. Rose Hall, located at Broadway at 60th St. in NY, NY.

Performed by the world renowned Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis, djembefola (master of the djembe drum) Weedie Braimah, and vocalist Shenel Johns, Afro! opens Jazz at Lincoln Center’s 2025-26 season of concerts, education programs, and other events celebrating Africa’s influence on jazz.

In 2006, Marsalis premiered Congo Square which evoked the spirit of the historic New Orleans site—then the only place in America where African slaves were allowed to dance and play drums. Composed for the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra and Odadaa!, a nine-piece Ghanaian percussion and vocal ensemble, the piece celebrated the cultural roots and mythic birthplace of jazz. Nearly 20 years later, Marsalis, the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Ghanaian djembefola Braimah, and vocalist Johns premiere Afro! inspired by Marsalis’ ruminations on Africa.

Afro! may explore the deep and enduring ties between jazz, the African continent, and its diaspora, a leitmotif that the Orchestra previously addressed in such past Marsalis opuses as Blood on the Fields (1996), Congo Square (2007), Ochas (2014), and the fresh big band arrangements comprising JLCO’s The South African Songbook concert (2019).

Tickets for Wynton Marsalis’ Afro! with Weedie Braimah and Shenel Johns: The Ertegun Jazz Concert include access to a pre-concert lecture in the The Agnes Varis and Karl Leichtman Studio at 6:30 p.m. on Sept.18-20. Audiences are welcome to a free performance by the Zwelakhe-Duma Bell le Pere Quartet in the Ertegun Atrium at 6:30 p.m. and during intermission on Sept.18 and 19.

Ticket prices begin at $30.00. For more information or to purchase tickets, visit jazz.org/afro

The September 20 performance will live stream exclusively on jazzlive.com

Following its Jazz at Lincoln Center premiere, the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis alongside drummer Herlin Riley, Braimah, and Johns will take Afro! and other selections from its celebrated repertoire on the Orchestra’s first multi-city tour of Africa. From September 26 to October 11, 2025, the group will perform in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Lagos, Nigeria; and Accra, Ghana.

In addition to concerts in convention centers and open-air venues, the Orchestra will perform or collaborate with local musicians in each city, and host education initiatives —a pillar of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s mission— at local schools.

“The earliest and most fundamental human mythology is African,” Marsalis says. “From Venda to Igbo to a host of other belief systems across the continent, there are viable solutions to today’s challenges.”

“Our ancestors had cogent and powerful thoughts on who we are as individuals as we pass through the natural cycles of life, how we should relate to one another socially, and how to be one with the universal spirit that inhabits all,” he continues. “In their globally influential music and dance concepts, we can perceive how to find harmony and balance with nature, how to perceive and interact with the supernatural, and how to create endless variations on fundamental themes in pursuit of a good time.”

Jazz at Lincoln Center’s 38th season, Mother Africa, delves into the creative spirit that unites African and American musical traditions, and runs from July 24, 2025 to June 20, 2026. The organization’s 2025-26 season includes 19 unique weekends of Jazz at Lincoln Center concerts in the 1233-seat Rose Theater, nine concerts in the 467-seat Appel Room, and more than 350 nights of music at Dizzy’s Club, in addition to webcast performances and in-person and virtual education programs. The 2025-26 season also features tour dates worldwide by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis, an ensemble of 15 virtuoso instrumentalists, unique soloists, composers, arrangers, and educators whose mandate is to coalesce and animate an unprecedented variety of styles and genres, in collaboration with noted guest artists and appearances by major figures in jazz and its related genres.

Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis Tour Dates

Thurs., Sept. 18 – Sat., Sept. 20, 2025

Rose Theater in Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall

New York, NY

Fri., Sept. 26, 2025

Standard Bank Joy of Jazz

Johannesburg, South Africa

Sun., Sept. 28, 2025

Standard Bank Joy of Jazz

Johannesburg, South Africa

Wed., Oct. 1, 2025

BC International Jazz Festival

Tamarind Tree Hotel: Misumi Garden

Nairobi, Kenya

Thurs., Oct. 2, 2025

BC International Jazz Festival

Tamarind Tree Hotel: Misumi Garden

Nairobi, Kenya

Sun., Oct. 5, 2025

Landmark Centre

Presented by Runway Jazz

Lagos, Nigeria

Fri., Oct. 10, 2025

+233 Jazz Bar and Grill / Ghana Jazz Foundation

Accra, Ghana

Sat., Oct. 11, 2025

+233 Jazz Bar and Grill / Ghana Jazz Foundation

Accra, Ghana

July 22, 2025

Behind the Scenes: Wynton Marsalis & The Democracy! Suite on BBC World Service

BBC World Services – Wynton Marsalis: The sound of democracy

Check out this exclusive BBC interview by Leo Hornak, who went behind the scenes with Wynton and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra as they got ready for the European premiere of The Democracy! Suite last March.

Listen now on BBC

June 24, 2025

Jazz at Lincoln Center’s 38th Season to Unite African, American Traditions

The concerts of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s 2025–’26 season, adhering to a theme of “Mother Africa,” will delve into the creative spirit that unites African and American musical traditions. Running from July 24, 2025, to June 20, 2026, and featuring 30% more shows than its last run, the organization’s 38th season includes 19 unique weekends of Jazz at Lincoln Center concerts in the 1,233-seat Rose Theater, nine concerts in the 467-seat Appel Room and more than 350 nights of music at Dizzy’s Club, in addition to webcast performances and in-person and virtual education programs.

The 2025–’26 season also features tour dates worldwide by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis in collaboration with noted guest artists and appearances by major figures in jazz and related genres.

Dominating Jazz at Lincoln Center’s 38th season are concerts that explore the deep and enduring ties between jazz, the African continent and its diaspora, a leitmotif that the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis previously addressed in such past Marsalis opuses as Blood On The Fields (1996), Congo Square (2007), Ochas (2014) and the fresh big band arrangements comprising JLCO’s The South African Songbook concert (2019). The season highlights new works, commissioned by Jazz at Lincoln Center, from jazz artists in the organization’s new The Commission Series. The new season also includes celebratory concerts to honor the centennials of three towering figures in jazz — Miles Davis, Oscar Peterson and Celia Cruz — further illuminating the far-reaching legacy of Afro-American and the African diaspora musical expression.

“The earliest and most fundamental human mythology is African,” JALC’s Managing and Artistic Director Wynton Marsalis said. “From Venda to Igbo to a host of other belief systems across the continent, there are viable solutions to today’s challenges.”

Several of the performances on the season address the creative sensibilities that enslaved Africans applied in embedding the rhythms, timbres and melodies from their religious-cultural traditions into the DNA of Black American Music — Negro spirituals, the blues and early jazz — in the United States. Another cohort of concerts home in on the Afro-diasporic vernacular and popular musical genres that evolved in the Caribbean, Central American and South American diasporas and permeated jazz expression from early 20th century New Orleans origins through the first quarter of the 21st century. Others focus on the African consciousness of such modern North American jazz masters as Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Max Roach, Randy Weston, Oscar Peterson, Charles Mingus and Horace Silver, and the musical production of African jazz musicians after 1945, when the African nations were established and the United Nations was formed.

“Our ancestors had cogent and powerful thoughts on who we are as individuals as we pass through the natural cycles of life, how we should relate to one another socially, and how to be one with the universal spirit that inhabits all,” Marsalis said. “In their globally influential music and dance concepts, we can perceive how to find harmony and balance with nature, how to perceive and interact with the supernatural, and how to create endless variations on fundamental themes in pursuit of a good time.”

View full details of Jazz at Lincoln Center’s 2025–’26 season concert schedule

A Father’s Day to Remember: Wynton Marsalis & The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra Light Up Philadelphia

This past Father’s Day in Philadelphia, the Kimmel Center’s newly named Marian Anderson Hall was alive with the electrifying spirit of jazz. Presented by Ensemble Arts Philly, the legendary “Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra”, led by the incomparable Wynton Marsalis, delivered a concert that was nothing short of extraordinary—a soulful celebration, a history lesson, and a masterclass all in one.

Wynton Marsalis, globally revered trumpeter, composer, educator, and champion of jazz, brought his signature brilliance to the stage alongside a powerhouse ensemble. From beloved jazz standards to rare historic gems and newly commissioned works, the evening was a dynamic journey through the genre’s deep and diverse legacy.

The orchestra, featuring a stellar lineup including Philadelphia native Joe Block on piano providing some stellar runs on the 88’s, delivered breathtaking arrangements of classics by Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Fletcher Henderson, Thelonious Monk, Mary Lou Williams, Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, and Charles Mingus, to name just a few. Their interpretations were bold, elegant, and bursting with soul—showcasing the precision, swing, and expressive power that Marsalis and his orchestra are known for worldwide.

A highlight of the night was Marsalis’s moving tribute to mentorship and youth. Known for his deep commitment to nurturing the next generation, he praised the importance of passing the torch: “Part of the continuum of our music is standing on the shoulders of those before us, while recognizing the brilliance of younger musicians.” He also gave special recognition to Mr. Lovett Hines of the Philadelphia Clef Club, honoring his decades-long dedication to teaching and inspiring young jazz talent in the city.

The setlist was both powerful and poignant. The orchestra’s rendition of John Coltrane’s “Alabama” was hauntingly beautiful, while “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby” (featuring warm, witty vocals from trombonist Vincent Gardner) brought the crowd to life. The finale, “Up From Down,” a Gardner original, earned a well-deserved standing ovation.

Marsalis also delighted the audience with personal stories—like performing in Spain at a soulful ice-skating rink arena where he debuted his vibrant “Medearaza Swing.” His humor and heart added another layer of connection between the music and the audience.

For the encore, the orchestra brought the house down with a stunning rendition of the spiritual “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho,” sending the audience home with full hearts and rhythmic feet.

The evening was more than a concert—it was a gift, a celebration of fatherhood, mentorship, and the enduring power of Jazz. Wynton Marsalis continues not only to preserve the genre but to expand it, inspire with it, and pass it on.

Source: ThisisRnB.com

May 23, 2025

Review | Lively History Lesson in Houses of Assorted Repute

At the post-performance reception for last week’s appearance by Wynton Marsalis and ensemble, providing a thrilling live accompaniment to the modern silent film LOUIS, an embellished and sometimes racy tale of Louis Armstrong’s formative years, the famed trumpeter was addressing the gathering in the Arlington court and paying props to his collaborators. He pointed out the stellar pianist Cecile Licad, whose playing of early 20th-century music by Louis Gottschalk is a key component of the project, and had words of praise for director and collaborator Daniel Pritzker, who first approached Marsalis about the film/performance concept in 2005.

“I liked him right away,” Marsalis effused, “because he could name all the members of Buddy Bolden’s band.” Bolden is the enigmatic legend of early New Orleans jazz, considered a pioneering force in the birth of jazz as we know it, but who never recorded and spent his later years in a psychiatric facility. Pritzker ended up directing the biopic Bolden in 2019, an interesting but flawed film, with a chronologically circular and dizzy structure.

But LOUIS, a kind of “prequel” biopic about the childhood of Armstrong, came first. The unique end result, which premiered in 2010 and had its West Coast premiere at the Arlington Theatre on Saturday (hosted by UCSB Arts & Lectures), is a contemporary silent film in which the musical component is very much live, alive and kicking and riffing in real time. Watching the film in streaming mode only goes so far: As experienced at the Arlington, the full effect is exponentially more engaging with Marsalis and his 13-piece big band onstage and in the shiver-some moment.

It makes perfect sense that both Pritzker and Marsalis would rally around the subject, and the seminal era in jazz. Over the course of 40-ish years, Marsalis has expressed his deep love for and preservationist’s advocacy for jazz of the pre-mid-1960s sort, with special reverence for Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. Not incidentally, in LOUIS, Marsalis’s powerful and pitch-perfect trumpet work often stole the show and our sensory attentions and affections.

Pritzker’s obsession with silent film is funneled into a project which adheres to tropes and tics of the silent genre/era, using overly copious degrees of melodrama (including an arch villain resembling Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator), slapstick shtick, and iris shots galore.

The film doesn’t shy away from the sordid environment Armstrong grew up around, in the red light “Storyville” district of New Orleans, reputedly the very seedbed of jazz’s birthing process.

From a more contemporary perspective, LOUIS may be the raciest silent film to date, but for a logical contextual reason. Breasts are bared, hedonistic abandon is afoot in the “house,” business transpires upstairs, and a key dance sequence oozes with sensual sex work excess while the band plays on and Marsalis issues muted trumpet shouts.

One intriguing footnote with the film is the all-important visualization of the famed cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond, in one of his last projects before his 2016 death. His deft and roaming camerawork gives the film an admirable sheen and shimmer. A clever cameo footnote finds Zsigmond in the brief role as a still photographer who is brusquely kicked out of the room by our resident arch villain character Judge Perry.

At some points, we drift away from the filmic dimension and get lost in the music onstage, an amalgam of original material and rearranged music by Armstrong, Ellington, and Jelly Roll Morton, and the dazzling jazz-cum-classical piano interludes of Gottschalk, courtesy of Licad’s limber virtuosity.

In this latest of many Marsalis performances in Santa Barbara (watch for the return of his brilliant Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra next February), the filmic context represented a valiant new twist on the ongoing agenda of shedding light on jazz historical loam. A highlight of the night at the Arlington actually came in the pre-screening performance by the band, and as it stretched out during and after the end credits. It’s always a pleasure to hear Marsalis and his top-notch allies in action, in any setting.

A special shoutout goes to a new member of Marsalis’s Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra clan, potently gifted saxophonist/clarinetist/flutist Alexa Tarantino — who replaces the departing Ted Nash as the first female musician in the ranks, a long-awaited gender-leveling gesture. Tarantino made a powerful impact with her imaginative and spidery alto sax solo at evening’s end. Louis would approve.

By Josef Woodard

Source: Santa Barbara Independent

May 16, 2025

Wynton Marsalis leads live jazz score for ‘Louis’ in Bay Area

Jazz history will come to life in the Bay Area when the black-and-white silent film “Louis” is paired with a live musical score by famed trumpeter Wynton Marsalis.

The 2010 feature by director Dan Pritzker imagines the early life of pioneering trumpeter and vocalist Louis Armstrong, and boasts such acting talent as Anthony Mackie (“Captain America: Brave New World”) and Jackie Earle Haley (2009’s “Watchmen”).

But Marsalis is the main attraction of an upcoming West Coast concert tour of the film, which kicks off this month. It makes a stop at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland on Saturday, May 24, presented by SFJazz. Local fans can also catch it the following night at Santa Rosa’s Luther Burbank Center for the Arts. He and an 11-piece band plan to perform his original music plus a few jazz standards, while classical pianist Cecile Licad has been tapped to play solo works by 19th century American virtuoso Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

“In the 1990s, I took my mom to see ‘City Lights,’ (Charlie) Chaplin’s movie, with the Chicago Symphony playing the score, and it just blew me away,” recalled the filmmaker, who grew up in Chicago and is an heir of the Pritzker family, known for their ownership of Hyatt Hotels. “I had seen silent films and always liked them, but I was not a buff.

“So I decided I was going to do this the right way. I wrote (a) script based on the story of a boy in New Orleans in the early 1900s who wants to play trumpet, and then I started really watching silent films, maybe two or three a day, for years.”

A Marin County resident for more than two decades, Pritzker first made his mark on popular culture as leader of the 1990s alternative rock and soul band Sonia Dada. But it was his deep knowledge of Armstrong and another seminal horn player, Buddy Bolden, that impressed Marsalis. This expertise was key to the director successfully recruiting Marsalis in 2005 over a seafood dinner in New York to score “Louis” and also “Bolden,” a more traditional color feature that was filmed concurrently but not released until 2019.

“It’s the only time I’ve ever met with a person who wasn’t a historian who had that level of understanding,” Marsalis told the Chronicle by phone from his home in New York City, where he serves as managing and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center.

Soon after that dinner, Marsalis delved into the meticulous process for putting together the “Louis” score.

“All of it is composed — even ‘improvised’ parts,” he said in explaining how the project is uniquely “through-composed,” meaning every note of it is written.

He added that for the live performances, Andy Faber, a frequent collaborator with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, conducts to a click track.

JLCO mainstays like alto saxophonist Alexa Tarantino and bassist Carlos Henriquez, as well as other notables like baritone saxophonist James Carter and drummer Jason Marsalis, the trumpeter’s youngest brother, are among the 11 members of the live ensemble.

Licad anchors the other end of the score. Born in Manila, Philippines, and trained at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music, she was introduced to the works of New Orleans native Gottschalk in 2000.

“He was snubbed a lot by East Coast people who didn’t take him seriously at the time, but he was just so incredible,” she said by phone from her Manhattan home.

That admiration comes through in Licad’s performances, according to Pritzker.

“As I was researching Gottschalk, arguably the first American piano virtuoso, I started listening to current players of his music,” he said. “I thought Cecile was the best person playing that material.”

That lasting impression had everything to do with Licad hitting on the right interpretation. “She’s also Chopin-esque, like he was,” Pritzker said, referencing Frédéric Chopin, the Romantic-era composer and pianist. “Other players were playing it more in a Scott Joplin style with no dynamics.”

While she’d never embarked on such a project, her grand-uncle, Francisco Buencamino, was a pianist who wrote scores for Filipino silent films, so she said there was a feeling of familiarity. But when Licad joined the team in the mid-2000s, she was wholly unaware she’d also be collaborating with Marsalis.

As it turned out, Licad and Marsalis weren’t exactly strangers.

“Cecile and I were signed to CBS Masterworks around the same time in the early 1980s, when we were in our late teens, early 20s,” the trumpeter revealed.

“We went to a concert together to hear (conductor) Claudio Abbado, and we ate dinner together with Claudio too,” Licad added. “Wynton was wearing this really shiny suit, and I’d never seen anyone so young and so confident. I was very shy socially — very much the opposite.”

Since then, Marsalis’ projects, from quartets to a big band, have left an indelible mark on generations of musicians and educators. Combined with initiatives like the Lincoln Center’s WeBop program, which introduces children as young as 8 months to the art form, and its comprehensive collegiate curriculum, he has particularly become a defining voice for jazz education and advocacy.

Yet, even with an accomplished career spanning more than 40 years, the Grammy-winning trumpeter is keenly aware of the opportunities that remain.

“There’s more types of gravity than physical,” he reflected. “And you just start to understand what can be done with the amount of time you have.”

This understanding fuels his creative drive. In addition to his early compositional career writing pieces firmly rooted in jazz forms, Marsalis’ output in recent decades has extended to the classical world. His new Concerto for Orchestra is slated to receive its U.S. premiere from the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl in September. He’s also currently working on a cello concerto and his Fifth Symphony.

“That’s the fun of being in a field like music, where you don’t time-out,” the 63-year-old said. “If you’re an athlete, at a certain point you can’t play anymore. But in music, you can play.”

by Yoshi Kato

Suurce: San Francisco Chronicle

May 14, 2025

Silent film and live jazz come together in Santa Barbara for a show about music legend Louis Armstrong

Louis is a modern-day silent film, complete with a sepia tone. It tells the story of a young Louis Armstrong in New Orleans and features a soundtrack performed live by Pulitzer Prize-winning jazz musician Wynton Marsalis.

The trumpeter and composer admits that, as a young teenage musician, like many of his age, he wasn’t a fan of Armstrong.

“I grew up in the civil rights movement,” said Marsalis. “We didn’t like his [style of] talking, singing, and all that. He seemed like he was from the minstrel era. But also, we didn’t listen to his music. We didn’t actually know who he was.”

Marsalis said the Armstrong hit song Jubilee helped change his mind about the legend.

“My father (who was a well-known musician) knew a lot about the history, and taught it,” said Marsalis.

“When I moved to New York (to study music), I was 17. He sent me a tape and said, ‘learn some of these solos.’ That night, I’ll never forget, I started with a song called Jubilee. [It] was so complex I couldn’t play it. It gave me instantly another level of understanding and respect. After that, I got into his music.”

In 2006, Marsalis brought together some of the biggest names in contemporary jazz to record a version of the classic 1920s Armstrong Hot Fives and Sevens collection.

“It was more like a modern take using his orchestration concepts, to do it the way we would do it,” Marsalis said. “It would be interesting to listen to what we did in relation to the way they did it.”

Now, the 90-minute silent film Louis, accompanied by a live jazz ensemble, brings Armstrong to life again in a different way.

The movie, directed by Dan Pritzker, is loosely based on Armstrong’s childhood. Pianist Cecile Licad and an 11-piece all-star jazz ensemble accompany Marsalis.

He said one of the special things about the project is that as it tours, it’s always different. It’s live jazz, and they’re always improvising.

“They’re going to hear authentic music from a time period that they haven’t heard,” said Marsalis. “We bring these historical things together. It’s very unusual.”

UC Santa Barbara Arts and Lectures presents Louis Saturday, May 17 at 7:30 p.m. at Santa Barbara’s Arlington Theater.

By Lance Orozco

Source: KCLU Radio

Why Wynton Marsalis will never be over the transcendent genius of Louis Armstrong

Wynton Marsalis is on his way to Chandler Center for the Arts with Cecile Licad and an all-star jazz ensemble to perform the score to “Louis,” a silent film telling a mythical tale of a young Louis Armstrong in the cradle of jazz, New Orleans, on Thursday, May 22.

Marsalis will play a score comprising primarily his own compositions with a 13-member jazz ensemble while Licad will play the music of 19th century American composer L.M. Gottschalk.

Marsalis spoke with The Arizona Republic about his involvement in the movie, which grew out of a conversation with filmmaker Dan Pritzker about American cornetist Buddy Bolden, a key figure in the development of a New Orleans style of ragtime music that became what we now know as jazz.

Here’s what he had to say.

How Wynton Marsalis got involved in the silent film ‘Louis’How did you come to get involved in this “Louis” project?

(Pritzker) was talking about making a film on Buddy Bolden. Well, it was the first time in my life I had ever been approached to do anything about Bolden, and just sitting down with him, he knew all the people in the bands and had a sense of the connection to American history of that time.

So the original talks were about Buddy Bolden, and then the silent film came after that. And that was just a kind of mythic, nonfactual thing that dealt with life in New Orleans around Louis Armstrong’s time with little Pops as a character from a mythological standpoint.

All of these were Dan’s ideas. He had seen a Charlie Chaplin film with the Chicago Symphony backing the film and he thought it would be a good idea to do a contemporary silent film.

What was the appeal of the project to you?

Well, one was to recreate Bolden’s style for me as a trumpet player, because I had always heard that he played less than the people who came after him, you know? And I always thought that was kind of curious, because most of the people, the people who invent styles, always played much better than the ones who followed them.

If you take Charlie Parker, he played his style better than anybody who played it. You take the style Louis Armstrong invented, many trumpet players came out of his style, but his style was the prototype. Generally, the prototypical style is an amalgamation of all the styles that came before it.

If you take what Beethoven combined to follow Haydn, and then, even though he wasn’t trained in that when he was younger, as a much older man, he began to try to write fugues and other things that were much more the provenance of Bach in the earlier era.

I just feel in the arts, that’s just how it always works. The person who brings together the styles influences other people with aspects of their personality, and then eventually another person comes that amalgamates all those styles. So I was really interested in that.

And with the silent film, he was talking about Gottschalk and that kind of New Orleans music — piano music, parlor music. I thought that was a good idea. And once again, I mean, how many times you ever talk to anyone about Gottschalk’s music? In my life, that’s maybe one of two conversations I’ve had. And I’m not a spring chicken, you know what I mean?

And the piano player he wanted to play with was Cecile Licad, and just ironically, she and I were signed to CBS Masterworks at the same time when we were young people. In 1982, ’83, we were 21, 20 years old. So I was very familiar with Cecile, because we had the same product manager, Miss Christine Reed. So I knew all of Cecile’s early records and had heard a lot about Cecile from Christine.

I thought, What’s the chances of this, 20-something years later, to meet somebody talking about Gottschalk, Louis Armstrong, Buddy Bolden’s band and knows Cecile. So you know, yeah, I had to say yes to it.

And when you play in Chandler, you’re providing the score live?

We play the score live, yeah, with a click track (a metronome, used to keep the live performance synced up with the film). A lot of the music is written, but some of it is improvised, too. Andy Farber is the conductor, the same conductor we had originally.

I was wondering how much would be improvised.

Well, you figure, the rhythm section is improvising almost all the time. I would say 50% of it, probably? Fifty-five? But we have a click track, and we have to stay on cue.

Building the score for a silent film about young Louis ArmstrongHow did you go about writing the score?

Well, in the case of this score, Dan used different musics, and he put them together the way he wanted to. And whenever he needed some new music, he said, I need music from this time to that time. But he’s a musician, so he has a good sense of it. I like the way he uses the music. He picked some difficult music to play, too.

Was the idea to capture the spirit of Armstrong’s work, or the music that inspired him, or something different altogether?

Well, to say that it’s all a continuum. We represent the continuum. So this is all a part of the table we can set and the menu we can serve. It includes Gottschalk. It’s about Louis Armstrong. It has him, but it also has songs that sound like (Arizona native Charles) Mingus wrote them, or something that nobody at any time has done.

Was the film what you imagined it would be when Dan approached you with the concept?

I didn’t really think about what it would be. We kind of learn playing jazz, if me and you were playing together, I can’t have a picture of what you’re gonna play in my mind, because if I do that, then I’m gonna start judging what you play.

And many times, when you hear a take of something, or you hear a tape back of a piece that you thought sounded a certain way, it doesn’t sound like you thought it sounded. And that’s because your perspective when you’re listening to it is prejudiced by what you expect to hear.

I didn’t have a vision for a silent film, of a contemporary film set in that time. And it had all the kind of fundamentals, mythological things, a lot of American mythology.

Like, the judge has the baby with the mulatto girl, and there’s political corruption in the police and the younger person in that environment trying to make his way, and the kind of moral decisions people have to make, and some make moral decisions and some don’t. And young genius and virtuosity and the upper class and the lower class, all these kind of grand themes that run throughout all of our mythology.

Wynton Marsalis: Louis Armstrong’s ‘genius was transcendent’Could you talk about how Armstrong has remained such an iconic figure in the history of jazz, in the history of music?

He was just that great. It’s like how Bach has remained. Bach just consolidated the 10-finger way of playing the keyboard. Louis Armstrong taught us how to improvise coherent solos. He was a master of the blues. He could play tangos and things in the Afro-Latin diaspora. Many times, people in those cultures would say, ‘Man, who the hell is that playing our music that well?’

He was an unbelievable singer. He influenced everybody. Even Frank Sinatra said about him, ‘He’s the beginning and the end of it.’ And everybody from Frank to you-name-it, whoever was great, they loved him. Billie Holiday.

People might not have necessarily liked his demeanor because he had an element that came from that minstrel era. But his genius was transcendent.

And if you’re a trumpet player, man, you know…. (laughs) What can you say? Whatever he played on our instrument, it was never played like that before or since. I mean, at this point, you can’t imagine anybody playing with the type of human depth that he played our instrument with, especially when he became an older man.

Some of Louis Armstrong’s playing in the ’60s doesn’t even sound like a trumpet. It’s like a person talking to you.

So his genius has merited that type of attention. And even with all the kind of ‘yuck-yuck’ entertainment stuff that he did, that was required of him to do — and it was something he did willingly — even that has not been able to obscure the actual depth of his genius.

So the contemporary student today, when confronted with Louis Armstrong playing, if they’re a trumpet player, believe me, they say, ‘Damn, what in the world could I do to play like this man plays?’

How New Orleans shaped the musician Louis Armstrong becameCould you talk about the role New Orleans played in shaping the musician Armstrong became?

Well, you got to figure it was French. It was Spanish between 1750-something and 1800. It was at the mouth of the Mississippi, so you had all the riverboat Americana people there. It was the largest Southern port. It was a center of legal prostitution, so all the sailors were down there coming from the Caribbean. You had all that influence.

You had all the stevedores and people working on the levees and their songs. You had the blues coming from Mississippi, and all those people down below sea level in the capital of malaria and diphtheria and typhoid, all the stuff we had that would ruin our population from time to time.

They were hot-blooded people who were always ready to enter into a duel. And the slave population was much freer than it was in other places. Then you had an influx of Haitians after the Haitian Revolution. So it was and unlike any other place in the United States. It was Catholic and it wasn’t Protestant because of the French. And it had Santeria, and all the kind of European traditions were still down there.

So it’s all of these types of things that took place in New Orleans that didn’t take place anywhere else. The Mexican pop exposition brought an influx of Mexican musicians and the style of music that they played. Manuel Perez was a great cornetist who came out of that influx and so on and so forth.

You had the French music and the kind of parlor music that Gottschalk’s music represents. You had the bands used for advertisements. You had white, Black and Creole, a three-strata caste system that was not the way it was in the rest of the United States. I could go on and on.

And all the people at the bottom of society, all the people in the clubs, the sporting houses, people involved in prostitution, gambling, all those people always had an equality you didn’t find anywhere else in the world, right? Because when you’re down there, you’re with everybody else, you know? Jelly Roll Morton actually said that.

Wynton Marsalis: ‘I’m still trying to learn and become better’What’s been the best part of being involved with this project for you?

It’s all the music I learned and had the opportunity to play, especially if you combine it with Bolden, you know? I got to study styles of people like Freddie Keppard and Manuel Perez and Bunk Johnson and King Oliver, and look at their styles and just learn more about our instrument, more about playing jazz.

That’s an important history that I knew and was familiar with, coming from New Orleans, but to really study it helped my musicianship at that time, I think.

It’s great to hear someone who’s done as much, accomplished as much, as you talk about this as a learning experience. It’s great that you’re still learning.

Hey, man, I appreciate you saying that. Yeah, I’m still trying to learn and become better, more knowledgeable.

‘Louis’: A Silent Movie with Live Accompaniment by Wynton Marsalis and Cecile Licad

When: 7 p.m. Thursday, May 22.

Where: Chandler Center for the Arts, 250 N. Arizona Ave.

Admission: $62 and up (fees included).

Details: 480-782-2680, chandlercenter.org

by Ed Masley

Source: The Arizona Republic

Wynton Marsalis's Blog

- Wynton Marsalis's profile

- 52 followers