Zoë Tavares Bennett's Blog

November 7, 2025

why dune is really for the girls

I posted this to my TikTok, but I fear this 14-minute video will not be fully appreciated on there, and given that Substack is usually kinder to long-form content, I thought I would post this here, since it is very much like a reflection post I would write out.

One note: I mention in this video that there are no SFF female-written novels that explicitly have an all-female governing body. There is a high chance it exists, but I do not know of any among the major franchises, which, I think, is telling in itself.

However, after making this video, I recalled Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, which centers around a planet with androgynous beings who only physically express one of two genders (either male or female, and this seems to be up to chance) in certain contexts. I don’t think this counts as an explicit female-governing body, though. Instead, I view it as an interesting exploration of gender, sexuality, and social politics. For instance, the protagonist ends up falling in love with one of these androgynous natives when he visits their planet, but as a male human, he struggles to accept that the person he loves contains both the male and female within them.

In Dune, on the other hand, the governing bodies by book 6 are explicitly female, and must be biologically female to become pregnant, which is a major part of their governing strategy, namely controlling their “breeding program.” Many readers criticize the fact that queer sexualities are entirely absent from the Dune series. I agree that it would have been interesting to include this, since Herbert does seem to analyze every other aspect of human nature and society, and it could introduce thought-provoking complications.

But putting that aside, I do appreciate what he does explore, and taking seriously the possibility of an all-female governing body whose strategies of power, control, and governing are different from the previous all-male governing bodies. If we compare other SFF series, like Game of Thrones, for instance, or even Star Wars, where women are never entirely in power—inevitably situated in patriarchal, male-dominated worlds—or if they are in power, are just as psychotic, violent, conniving, and sometimes downright evil as their male counterparts and/or eventually killed off to leave room for the male hero, the conclusion of the Dune series is refreshing.

Nevertheless, I hope you all enjoy this video. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

Vale!

Zoë

November 3, 2025

why I don't read mythological retellings

>why I don’t read mythological retellingsFrom the Writer’s Desk:

>New Releases

>Current Projects

>What I’m ReadingIn Other News:

>A QuoteMy Books (where to buy)

My Podcast (where to listen)

why I don’t read mythological retellings: Persephone & Hades as romance

As someone who studied Classics and loves the ancient world, people are always surprised to discover that I don’t read Ancient Greek mythological retellings. I hesitate to admit I haven’t read Percy Jackson either. While I did read Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles and Circe when they were published, I fear those novels have opened the floodgates of less researched, rather hollow mythological retellings, like the various iterations of the Persephone and Hades myth that slip into romantasy (aka ‘romance with a side of fantasy’) territory.

This isn’t hate or censorship! Let me be clear. I love that people enjoy ancient myths in all their forms, and that so many people are still fascinated by the ancient world, their mythologies, and their stories. I love that people are reading at all. But personally, I cannot enjoy these kinds of novels—specifically the blatant romanticizing and eroticisation of previously religious myths—and there are a few reasons why.

Let us take the Persephone and Hades “myth,” which is a regrettable misnomer the modern world has imposed on ancient religions that mastered the art of storytelling to breathe life into the inanimate as well as divine realm.

The story of Persephone’s marriage to Hades, lord of the Underworld, comes from the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. Unlike the modern romanticized retellings, the original version is anything but romantic. Persephone, for one, is named for most of the hymn as κόρη (korē), literally a maiden or virgin, and thus unmarried. As the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, she is a goddess and immortal, but in the story, she is depicted nevertheless as a young girl. In that time, girls could be as young as twelve (if not younger) when they were married, most likely to a man twice or even thrice their age, and certainly not willingly or chosen. Like Zeus, fathers would give their daughters away in marriage, as property that would then become the property of their husbands.

To make matters worse, the depiction of Persephone, the korē, given to Hades in marriage, is blatantly violent. While picking flowers in a field with her friends, she reaches for a narcissus grown to deceive her. As she does so, the earth beneath her gapes open. Hades rushes out on his chariot and seizes her, carrying her down into the Underworld. The much-discussed verb used for this ‘siezing’ act is ἁρπάζω, meaning ‘to snatch away, carry off, or seize,’ but with such an underlying violence that many scholars will translate it as ‘rape.’ As she’s being carried away, she cries out to Zeus, claiming the union as unjust and lamenting her fate.

When Demeter, Persephone’s mother, hears the cry of her daughter on the wind, she immediately rushes to find her. The grief of losing her daughter in marriage to Death sends Demeter into a wrathful revenge. She punishes the earth, rendering fields and farms barren. This motif is found in many other cultures and is closely associated with the cycles of the seasons, more so than the dying-and-rising god archetype, like that of Persephone. Even so, the hymn to Demeter has much less to do with explaining the four seasons than ritualizing the cycles of a woman’s life, from girlhood (or maidenhood) to womanhood, marked in those days by being a wife, mother, and even grandmother, represented in the lineage of Persephone as the korē, Demeter as mother and wife, and Rhea, mother of Demeter, as the head of the matriarchy.

In the Underworld, Persephone famously eats pomegranate seeds—a trick by Hades, supposedly, though many a scholar has debated the willingness of Persephone in this exchange (which could perhaps be the seed, if you will, for the modern, more romantic retellings). Metaphorically, the consumption of food in the Underworld is related to the consummation of marriage and the loss of the korē’s virginity. The idea of eating food and becoming trapped in some kind of dead or undead realm is not unique to the Ancient Greeks; a parallel can be found in Celtic and Germanic traditions, for instance, with the land of faerie, where maidens were snatched away to marry the faerie King in an underworld realm.

Therefore, the reason I struggle to romanticize, let alone eroticize, this relationship between Persephone and Hades is because of the inherent violence and weight of the original myth. The fact that Ancient Greeks equated a woman’s marriage to literal Death is profound and worth contemplating, even if most of our lives today do not look like theirs. Marriage, after all, is a kind of Death, whether of the self, childhood, our past life, innocence, or the final separation from our mothers. Even the ancients recognized a level of injustice to it all, whether you romanticize marriage or not.

Some may argue it is empowering, on a certain level, for modern women to retell the story and allow Persephone to fall in love, to take charge of her fate, and most importantly, her sexuality, which has so often been weaponized against women or controlled. And I respect and support our modern right to do so. But the intense eroticism of modern romantasy retellings (and perhaps more to the point, the various erotic iterations of the “trope” girl x immortal male Death figure in romantasy) often obscures the complexities inherent in the original myth, which point to the brutal realities of womanhood in that time (and for some women in our time too), as well as meaningful, enduring truths about marriage that may surprise us, given the archaic nature of these stories.

It is important, ultimately, to recall that these myths, especially those centered around gods, like the myth of Persephone and Hades in the Hymn to Demeter, were ultimately religious hymns. They would have been sung in ritualistic contexts, most likely in spaces made up entirely of women, honoring as well as lamenting the stages of life, from maidenhood to the full maturation of womanhood, our entangled relationship with Death and immortality, and the contradictions of marriage and power which we still must grapple with today.

If we lose sight of the original context, we risk not only forgetting this ancient wisdom but also overshadowing the lives of women in the past, who were already so overlooked and forcibly eroticized, just as Persephone in the myth.

From the Writer’s DeskI’m focusing most of my attention on illustrating a poetry book inspired—not coincidentally—by the myth of Persephone, and her marriage/death as a korē and resurrection as a woman, when she is reunited with her mother. In my poem book, the korē figure is named Sofia, like the Greek word for wisdom, before she was “loved” by philosophers, alluding to the wisdom carried maternally and rarely given such a prestigious name as philosophy. Here is a look at the first poem in the book (almost all of which is written in meter!), called Ode to Sofia:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedOde to SofiaI used to sleep under the starsWhen gods kept watch at nightAnd Sun chased Moon across the skyLike two love birds in flight.If then my Fate is bound to EarthAnd Spring and Winter herald Death,Why calls Eternity my nameAn icy wind Her divine breath?Please tell me, Mother, who am IWhen snow buries me deepAnd Time is a forgotten nameI dream of in my sleep?Then will you hold me in your armsAnd whisper in my ear goodnight?Can then you call me Daughter andsay everything will be alright?I used to sleep under the starsBefore the taste of Love.My body knew without Him allthe deathless gods above.In the meantime, if you missed my interview about my ancient myth-inspired portal fantasy novel, THE SONG OF GAIA, check it out on YouTube below:

NEW RELEASES: LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:BOOK 3 REALM OF EMMESON - Third draft

SOFIA BEFORE LOVE (a book of poetry) - Illustrations

Iliad by Homer (in Ancient Greek!)

Lyra Mystica by Charles Albertson

Messenger of Olympus MJ Pankey

My other Substack, The Fellowship of the Readers, is slow-reading The Silmarillion over the next year. Join at any time if you are interested in reading or just following along with the occasional quote excerpts that I’ll send out to mark our journey!

A QUOTE:

Δήμητρ᾽ ἠύκομον, σεμνὴν θεόν, ἄρχομ᾽ ἀείδειν,

αὐτὴν ἠδὲ θύγατρα τανύσφυρον, ἣν Ἀιδωνεὺς

ἥρπαξεν, δῶκεν δὲ βαρύκτυπος εὐρύοπα Ζεύς,

I begin to sing of rich-haired Demeter, holy goddess,

of her and her trim-ankled daughter, whom Aidoneus

rapt away, given to him by loud-thundering, all-seeing Zeus.

―Homeric Hymn to Demeter, 1-3

Vale!

-Zoë

The Sun of God — an epic historical novel set in Ancient Rome

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, discount special edition hardcover, audiobook)

Imagining the Roman Empire: Essays on Travel & Antiquity in the Mediterranean

(Buy on Amazon coffee table book)

The Song of Gaia (Book #1)

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover, special dust jacket hardcover)

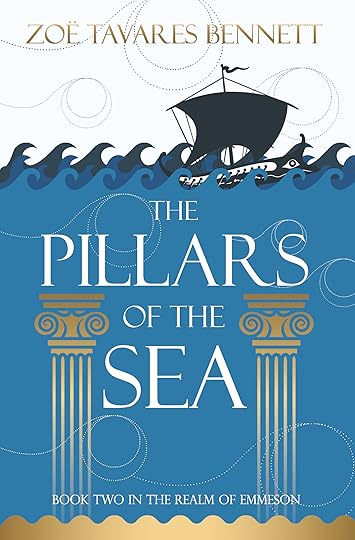

The Pillars of the Sea (Book #2)

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover)

My Sister’s Best Friend (Book #1)

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Best Friends & Their Exes (Book #2)

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Hot takes on the ancient world by two grad students and dead language fanatics!

Listen to our latest episode:“WORD You Rather: Germanic vs Romance Descendants in English”

Find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and most other podcast streaming services!

MEDITERRA is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

October 18, 2025

luwian hieroglyphs, written art, and permanence

>luwian hieroglyphs, written art, and permanenceFrom the Writer’s Desk:

>New Releases

>Current Projects

>What I’m ReadingIn Other News:

>A QuoteMy Books (where to buy)

My Podcast (where to listen)

Luwian hieroglyphs, written art, and permanence

Learning how to read Luwian hieroglyphs is not for the faint of heart. Mostly inscribed on monuments of religious and political significance, these carved signs may symbolize an entire word, a phonetic syllable, or something less clear. The same sign can be used in different ways, either standing in as a logogram in one context and a sound in another, not to mention that the same sign can be drawn in a monumental style or in a more abstract, cursive style, or in different ways altogether. Spellings can vary across inscriptions, across time and place, as well as layout, neatness, and genuine scribal errors.

In other words, Luwian hieroglyphs stand at a crossroads of language and artistry, and remind us of the very human impulse to strive for permanence in an impermanent world; each hieroglyph is at once self-confirming, an artistic expression, and a continuous dialogue with all those who have laid their eyes upon the drawn symbols—whether they understood their meaning or not.

A classic kind of monumental inscription dedicates itself to a god, as we see in part of BABYLON 3:

"Runtiyas placed these bowls before the Halabean Tarhunt.”

Runtiyas, the person who donated this large stone bowl (along with other objects) to the god Tarhunt, is an Iron-Age man, unknown to us now save by name. The scribe used cursive instead of highly stylized monumental hieroglyphs, dating the object later to the 8th century BC. We know Aleppo was a major cult center for Tarhunt, the Storm-God, which is likely where this bowl was originally placed. Yet the bowl was discovered in Babylon, as its name indicates, suggesting that the bowl was taken as booty during western campaigns to fill the royal collection of Nebuchadrezzar.

Unlike writing on other perishable surfaces, carving hieroglyphs into stone takes time and skill, even a certain artistry, as we will see especially below. This ritualistic form of artistic writing does not feel very different from prayer or penance, the repeated actions, the cost, the communication between a mortal and a divinity. What strikes me the most is his name—Runtiyas—the only other name in the inscription besides that of the god Tarhunt, and which had been carved directly before the god’s name. Though he honors a god, still, he desires his own name to be inscribed beside him. A very human impulse, isn’t it? How often is prayer truly selfless? How often do we look up at the sky and ask, Why me? Who am I? Can you hear me?

Another inscription more blatantly concerned with the monument’s creator is HAMA 2, one of the first Luwian hieroglyphic inscriptions found in the Syrian city of Hama:

“I (am) Uratamis, Urahilina’s son, Hamathite king. And I myself built this fortress, which the Lakaean river-land made, and the Land Nikima too.

Here we can see that stylistically the hieroglyphs have been carved in greater relief than the previous inscription. That is unsurprising given that a king had it made. This monument surely served many purposes, though it is impossible to know how the public viewing this monument would react. On the one hand, King Uratamis boasts of his royal lineage and brags about building a fortress; on the other hand, the Lakaean river-land and the Land Nikima are mentioned alongside him, and could be a source of regional pride.

I imagine a subject of the king reading this much like I read signs or campaigns about my local mayor constructing new public transit or a large building; the knowledge of its boasting nature, and yet, I cannot help but identify with my community and the fact that by extension, I am responsible for the new construction. While most of the Luwian citizens would have been illiterate, the beauty of hieroglyphs is that certain signs would have made their meaning obvious, and points to the irrefutable power of images (as we see every day with posterboards and media advertisements). And of course, by essentially putting his name on it, Uratamis takes on the permanence and grandeur of the fortress itself. Ironic that nearly three thousand years later and though the fortress has not survived, this inscription has, along with his name and his deed!

The last monument I will mention touches a more personal sphere of life: grief. Taken from Karkamis, the single site with the largest number of hieroglyphic inscriptions found, where this stele was dedicated by Suhis to his wife:

“I (am) BONUS-tis, the dear wife of the Country-Lord Suhis. Wheresoever my husband honors his own name, he shall honor me with goodness.”

Here we see a beautiful blend of art and language, where the first sign is actually the large carving of his wife, whose raised arm forms the shape of the logogram (called ‘EGO’ by standard practice) standing for the word I (in Luwian spelled out as amu). Sadly, we don’t actually know how her name was pronounced, since the logogram BONUS, which serves as part of her name, is still ambiguous as to its underlying sound in this context. But what does survive is the intricate relief of her with a spindle, used to weave, and the honor done for her in death.

Even though the Country-Lord Suhis has also put his name alongside hers, his wife has left her own mark, not only on this monument but on his name; absolutely nowhere—the repeated signs spelling out kwita kwita ‘wheresoever’ are as emphatic as it gets—shall his name be honored where hers is not also honored. And sure enough, millennia later, here she stands both literally and figuratively, her name a mystery, yes, but which somehow only makes me want to know her name even more.

From the Writer’s DeskI have finished the first draft and first round of edits on The Realm of Emmeson’s Book #3! After I get some feedback on it, I’ll dive into a few more rounds of intense editing before I begin the long formatting process. I hope to publish it mid to late next year. In the meantime, if you missed my interview about my ancient myth-inspired portal fantasy novel, THE SONG OF GAIA, check it out on YouTube below:

NEW RELEASES: LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:BOOK 3 REALM OF EMMESON - Second draft

SOFIA BEFORE LOVE (a book of poetry) - Illustrations

Iliad by Homer (in Ancient Greek!)

Lyra Mystica by Charles Albertson

My other Substack, The Fellowship of the Readers, is slow-reading The Silmarillion over the next year. Join at any time if you are interested in reading or just following along with the occasional quote excerpts that I’ll send out to mark our journey!

A QUOTE:

“Everything you do, everything you sense and say is experiment. No deduction final. Nothing stops until dead and perhaps not even then, because each life creates endless ripples. Induction bounces within and you sensitize yourself to it. Deduction conveys illusions of absolutes. Kick the truth and shatter it!”

― Frank Herbert, Chapterhouse: Dune

Vale!

-Zoë

The Sun of God — an epic historical novel set in Ancient Rome

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, discount special edition hardcover, audiobook)

Imagining the Roman Empire: Essays on Travel & Antiquity in the Mediterranean

(Buy on Amazon coffee table book)

The Song of Gaia (Book #1)

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover, special dust jacket hardcover)

The Pillars of the Sea (Book #2)

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover)

My Sister’s Best Friend (Book #1)

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Best Friends & Their Exes (Book #2)

(Buy on Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Hot takes on the ancient world by two Classics students and dead language fanatics!

Listen to our latest episode:“WORD You Rather: Germanic vs Romance Descendants in English”

Find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and most other podcast streaming services!

MEDITERRA is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

September 29, 2025

Tune in! The Song of Gaia goes live!

This Sunday, October 5th, Save the Ancient Studies Alliance, or SASA, will interview me about the first novel in my ancient mythology-inspired fantasy trilogy, The Realm of Emmeson! If you are interested in learning more about my book and the writing process, RSVP below:

Here is a summary of the novel for those interested:

A diary. A silver dagger. An ancient Greek text encased in gold.

These were the only belongings left behind by Alex’s mother, shoved in a box with her name on it—Elena de la Fuente—and forgotten for ten years.

On the surface, Alex Montgomery has it all. She grew up in the manicured suburbia of New York. She has Warren, a Prince-Charming boyfriend who wants to marry her. And she goes to Harvard, her father’s alma mater. But there is one blemish on her otherwise perfect life: the night before her tenth birthday her mother disappeared into thin air, leaving no trace or means of contacting her.

Silenced by shame and anger at a mother who abandoned her husband and daughter, Alex shut out every memory she had of her. But opening the box with her mother’s name on it awakens all the old doubts she had buried inside, along with the most burning question: Why did her mother leave?

Following the clues in her mother’s diary, Alex abandons her studies and drives across the country to Tierra del Sol, a small town surrounded by California’s mystical southern deserts, where her mother had attended the New Academy. There, Alex meets the young, charming Classics professor, Ari, the booksmart romantic, Penélope, and the moody, black-clad Zeb. But as the mystery of her mother’s disappearance unfolds, Alex stumbles upon a hidden door to a magical city where a tyrant King stifles the once-vibrant streets and harbors.

The hunt for her mother’s fate entangles Alex and her friends in the political turmoil of the city as they piece together the fragments of an age-old prophecy and the forgotten myth of the Emerald Stone. According to a lost hymn to Hermes, legend tells that the Emerald Stone contains the secret of the universe, which has the power to overthrow Zeus, the King of the Gods, and restore Gaia, Mother Earth, as Queen. But not everyone wishes to see the Old Faith restored.

On the run from hidden enemies—not all of them mortal—and chasing the ghost of her mother, Alex realizes that the prophecy runs deeper than mere myth and that her mother might not be who Alex thought she was. But in confronting her mother’s precarious past, Alex must face the doubts in her own life, such as her strained relationship with Warren, her secret attraction to the older, dark-haired Ari, and the possibility that she, like her mother, will leave it all behind.

Paralleled with the ancient, recurring story of Helen of Troy leaving her husband and daughter for love, The Song of Gaia tells a two-fold tale of womanhood as its own ancient legacy and the forging of a new one.

From the Writer’s DeskGood news from the writer’s desk! I have finished the first draft of the third Realm of Emmeson novel, and am already halfway through a round of edits. I’ve also begun my first week of grad school, so I’m feeling the pressure to have at least a revised draft completed as soon as possible. From there it will take time to get the details put together, but at least the novel will have a more holistic feel.

I’m also hoping to return to the illustrations of my poetry book, SOFIA BEFORE LOVE, which I would love to publish before the end of this year, if possible, though early next year feels more likely. We shall see!

I’ve also gotten more active on Instagram (@zoe.tavares.bennett) and TikTok (@zoetbennett)—*sigh*—but it can occasionally be fun. Engagement with my novels, even just on social media, is sometimes fun for an author, and it’s always good to see what people are reading (or not reading) these days. If you are on either of these platforms, check them out here.

Otherwise, I will be preparing for my SASA book club on Sunday, and studying for classes when I’m not editing my novel.

NEW RELEASES: LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:BOOK 3 REALM OF EMMESON - First revision

SOFIA BEFORE LOVE (a book of poetry) - Illustrations

Dune: Chapterhouse by Frank Herbert

Iliad by Homer (in Ancient Greek!)

Lyra Mystica by Charles Albertson

In keeping with my recent crochet craze, I had the idea of doing an ancient-inspired bag charm, so here’s a crochet amphora!

My other Substack, The Fellowship of the Readers, is slow-reading The Silmarillion over the next year. Join at any time if you are interested in reading or just following along with the occasional quote excerpts that I’ll send out to mark our journey!

A QUOTE:

The world is wonderful and beautiful and good beyond one’s wildest imagination. Never, never, never could one conceive what love is, beforehand, never. Life can be great—quite god-like. It can be so. God be thanked I have proved it.

—D.H. Lawrence, Letter to Mrs. S. A. Hopkin, 1912

Vale!

-Zoë

The Sun of God — an epic historical novel set in Ancient Rome

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount special edition hardcover, audiobook)

Imagining the Roman Empire: Essays on Travel & Antiquity in the Mediterranean

(Amazon paperback)

The Song of Gaia (Book #1)

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover, special dust jacket hardcover)

The Pillars of the Sea (Book #2)

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover)

My Sister’s Best Friend (Book #1)

(Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Best Friends & Their Exes (Book #2)

(Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Hot takes on the ancient world by two Classics students and dead language fanatics!

Listen to our latest episode:“WORD You Rather: Germanic vs Romance Descendants in English”

Find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and most other podcast streaming services!

MEDITERRA is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

September 16, 2025

machine-think, Dune, & our phone problem

>machine-think, Dune, & our phone problemFrom the Writer’s Desk:

>New Releases

>Current Projects

>What I’m ReadingIn Other News:

>A QuoteMy Books (where to buy)

My Podcast (where to listen)

machine-think, Dune, & our phone problem

“The devices themselves condition the users to employ each other the way they employ machines.”

This line shows up in the fifth book of Dune, a series most people know thanks to the blockbuster movies starring celebrity actors and emphasizing landscapes, aesthetics, and shock-value battle scenes over the information-dense ecology and nuanced political intrigue that make the novels so compelling to readers. As someone succinctly said to me a few days ago, the movies successfully capture “the vibes” of the books, but nothing much deeper than that.

This isn’t criticism per se, but more of a commentary on the importance of medium in dictating the creation, form, and reception of art, and how those media have shaped us in turn. A book has room for a page-long deep dive into the ecology of the planet Dune, or a sparse dialogue with an underlying, unspoken tension discerned only from their thoughts, reachable by the author but hidden on a movie screen. Yet a movie can add music, sounds, minute facial expressions, and body language that only human actors and cameras can capture, which otherwise would be imagined by the reader—but it has also made most people unable to read the six 500+ page novels the movies were based on. In this way, media, or “devices,” condition the user to create a certain way, to tell a certain story, and as is the case with the movie, for instance, to filter the story to better suit the device and thereby our own expectations of how a story should be told.

The quote, spoken by the God Emperor Leto, is not talking about the written word or films, but machines in general (we would more aptly call them computers). In the Dune universe, humans already waged a war against “machines” that could think, defeating and outlawing them before Paul Atreides was even born. It’s not hard to imagine a path leading to that stage of war if we look at our own world, where the phone dominates every aspect of our lives, AI can do jobs that humans used to profit from (not to mention artwork based on human artwork), and weaponry has advanced to the level of mass destruction. Luckily for now, machines have yet to achieve any likeness to true human consciousness.

Yet I am hesitant to criticize technological advances, being reliant on so many that I would never willingly give up—like electricity, cars, landline phones, televisions, even washing machines—which, at some point or another, were as loudly criticized as phones today as ushering in a worse era, criticism I’m sure many of us would laugh at now. But perhaps their criticisms held some truth, in that those new machines would permanently alter how human society functioned, whether for good or ill.

Electricity changed sleeping and waking habits, reduced fire risks but hid stars from densely populated areas; cars bulldozed their multi-lane highways and wide streets through historic urban centers and beautiful natural landscapes alike, but gave the average person access to countless resources, places, and people that would have taken days to months on horse, wagon, or foot; televisions simultaneously raise awareness of global issues, can change lives and cultures with art, while also becoming the new focal point of the home instead of a living room geared for conversation and familial convivium; and lastly, washing machines—well, I’d like someone to criticize those (which I’m sure someone in history has!), but nonetheless they freed our time and minds from chores, so that we can come up with more convenient machines at best and at worst, well, just take a scroll through TikTok. The “devices” rewire our brains, to use a machine-friendly metaphor, to become totally dependent on their convenience and uses, in some ways like them, to the point that most of us alive today cannot imagine a life without them.

This brings us to the phones, and more specifically, handheld phones and smartphones, which we can more generally call computers. Setting aside the novelty of AI and (somehow less impressive) self-driving cars, computers were the latest major and global technological revolution that has altered every aspect of human society, not unlike agriculture for making humans sedentary, although this change occurred and evolved rapidly over the last century instead of millennia. Many people (even me!) can recall a time when the internet or smartphones did not exist—no Google, instantaneous texts, casual tracking devices, FaceTime, let alone social media—yet I would wager almost none of those people (also including me) would give up their phones and return to the ‘good old days.’

Again, this is not a criticism, exactly, but rather an observation, and one that has become even more apparent to me in light of recent extreme events. Every aspect of human life, from dating, parenting, working, vacationing, dying, mental health, trauma, crime, politics, war, etc., is digested and regurgitated (often flagrantly distorted and misinformed) on social media platforms, especially TikTok, so that most people shamelessly receive news from Instragram reels and admit to being ‘influenced’ to buy or do something they saw on TikTok. But the rewiring has done more than that. Besides the egregiously addictive nature of these “devices,” humans are starting to become more like them. More black and white thinking, less literate and more screen orientated, quicker to use labels, less willing to engage in nuanced dialogue or debates, more self-image focused…the list goes on, but these come to mind as the most dangerous. In other words, I find machines, like AI, becoming more “human” to be far less terrifying than the thought of humans becoming more like “machines.”

I’m sure many of us have already seen the effects of this. Photoshopping tools, image and body-focused cameras, and the ability to constantly share your “brand” have led to plastic surgery and Ozempic frenzies, skyrocketing mental illnesses like eating disorders, anxiety, and depression, and a complete rewiring of how people make friends, date, hang out, and generally socialize (or don’t…). Younger generations reared on computers, especially the small ones they keep in their pocket all day and by their bedside at night, have a compulsion to label every aspect of themselves, from personality types, sexuality, horoscopes, diagnoses, etc. One could argue that the more granular labels of, say, sexuality or mental health, empower those who often feel unseen by the majority of the population, which can be true at the same time that these machines have rewired us to view ourselves through the language of computers (see? that’s called nuance). But labeling, while helpful and convenient as so much technology is on the surface, is a slippery slope. If you label yourself X, it means Y, but then you can’t be Z because that conflicts with Y and all Y’s are X’s but not all X’s can be Z’s…you get the point. Computers simply cannot deal with the gray area, the contradictions and multitudes of human emotion, the messy reality of mortal life on earth—and we are beginning to be unable to as well.

By constantly using machines, people have slipped into a pattern of black and white thinking. Like labeling, black and white thinking also leads to rewiring how we process the world around us, like catastrophizing or reacting to situations extremely. Dialogue and conversation are rendered nearly obsolete in the ping-pong framework of computers, which cannot process information, be interrupted, pivot conversation, swallow their pride, all while taking into account interpersonal relationships, emotions, and past experiences, quite like a human being can. It shouldn’t come as a surprise given that computer code boils down to a string of zeroes and ones, this or that, true or false, black or white. This lack of dialogue, however, then bleeds into real life, where even in person, we struggle to communicate with people who are different from us. It also frames relationships into a me vs. you dynamic, and on a large scale, the world into us vs. them, making it easier for humans to take antagonistic and extreme actions against the ‘other,’ inevitably leading to violence, which, if you think about it, is the most efficient way to end an argument.

Human interactions on screen, especially social media, are limited to that fraction of a moment and someone’s equally diced and packaged response, not to mention the ironic game of telephone that all information is channeled through before it reaches your carefully curated feed. There is the viewer and the viewed, the user and the using, the screen and the human…but the longer the human peers into the screen, much like a mirror, they will begin to reflect one another, which leads us back to Dune’s warning, which I encourage you to read again before setting your screen aside:

From the Writer’s Desk“The devices themselves condition the users to employ each other the way they employ machines.”

Finishing up the last seven chapters of ‘The Realm of Emmeson Book #3,’ which I have likened to a tennis match: sometimes the hardest part is ending it, and that goes for winning or losing, the former choking and the latter finally playing not-to-lose…

Similarly, I find myself unwilling to finish, especially given it’s the last book of the trilogy. It’s an ending of the ending, so it makes it twice as hard to wrap up, even though I know exactly what is going to happen. In many ways, my books are like my children, and it’s always hard to watch them leave the nest.

I also recently won an award for Save the Ancient Studies Alliance’s ancient historical fanfiction contest. My story, Servilia’s Pearl, is about the rare black pearl that Julius Caesar gifted his mistress, Servilia, costing him 6 million sesterces (which some have estimated would be about 1.5 billion US dollars). You can read it for free here, and in the meantime, here’s an excerpt:

NEW RELEASES:

“A black pearl,” Caesar explained. “They are very rare.”

I know how rare they are, she wanted to snap back, but her voice was caught in her throat, unwillingly stunned. She had received many gifts, from her husbands and from Caesar, but none had ever been so wantonly precious. The pearl was the largest she had ever seen, the light from a nearby lamp flickering blue and violet across its swollen surface. Its rarity and beauty prevented her from touching it, her hands clutching the box as if she hardly believed it existed.

“How much did it cost?” she finally asked.

He nearly smiled. “Ever practical you are.”

“How much?”

“Whatever figure you have in your head,” he said slowly, his smile growing into a smirk, “is not even a third of it.”

Her voice shook. “How. Much.”

“The price does not concern you. It is a gift.”

“Five hundred thousand sesterces?” she guessed, refusing to let it go, though there was a warning in her heart.

He was silent.

“Eight hundred thousand?”

His smirk widened.

“Not a million!”

“As I said before: not even a third.”

“By Hercules.” Her vision wavered. She was faint. The words fell from her mouth in a whisper. “Two million?”

“More.”

“Three and a half—you can’t be serious—four—more than four? You are lying—”

He shook his head, exasperated. “It was six million, if you must know.”

“Julius,” she whispered. He met her gaze, held it meaningfully, all fiery passion, drunk on his own wealth, his own power. “Six million sesterces,” she repeated, unable to stifle her awe. It was an outrageous sum, a price she would not have paid for anything, let alone a gem. Her fingertip grazed the smooth surface of the pearl at last, then dared to pick it up, cradling it in her palm. “Six million sesterces.”

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:BOOK 3 REALM OF EMMESON - First draft

SOFIA BEFORE LOVE (a book of poetry) - Illustrations

Heretics of Dune by Frank Herbert

Iliad by Homer (in Ancient Greek!)

Lyra Mystica by Charles Albertson

With school right around the corner, I’ve been squeezing in some last-minute crafts, like beaded bracelets themed for my mom’s Emmy party, others to track the phases of the moon, which I’ve given to family and friends, as well as crocheting a big Portuguese sardine plushie to decorate my purses!

My other Substack, The Fellowship of the Readers, is slow-reading The Silmarillion over the next year. Join at any time if you are interested in reading or just following along with the occasional quote excerpts that I’ll send out to mark our journey!

A QUOTE:

All truth—and real living is the only truth—has in it the elements of battle and repudiation. Nothing is wholesale. The problem of truth is: How can we most deeply live? And the answer is different in every case.

—D.H. Lawrence, Letter to Earl Brewster, 20 August 1926

Vale!

-Zoë

The Sun of God — an epic historical novel set in Ancient Rome

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount special edition hardcover, audiobook)

Imagining the Roman Empire: Essays on Travel & Antiquity in the Mediterranean

(Amazon paperback)

The Song of Gaia (Book #1)

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover, special dust jacket hardcover)

The Pillars of the Sea (Book #2)

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover)

My Sister’s Best Friend (Book #1)

(Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Best Friends & Their Exes (Book #2)

(Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Hot takes on the ancient world by two Classics students and dead language fanatics!

Listen to our latest episode:“WORD You Rather: Germanic vs Romance Descendants in English”

Find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and most other podcast streaming services!

MEDITERRA is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

August 17, 2025

A Summer of Dune (the books!)

Divine Chance, Human Emotion, & Faith in DuneFrom the Writer’s Desk:

>New Releases

>Current Projects

>What I’m ReadingIn Other News:

>A QuoteMy Books (where to buy)

My Podcast (where to listen)

Divine Chance, Human Emotion, & Faith in Dune

As someone who watched the Dune movies before reading the book, I was pleasantly surprised by the deeply intellectual and often meandering, philosophizing nature of the novels in comparison.

Battle scenes, strategic warfare, massive explosions—those are all side notes in the grand scheme of the political intrigue, religious maneuverings, and true spirital quests which are told through multiple complex storylines. And as one continues reading the series, the politics, philosophy, and religion of the characters and times evolves with evolution itself, turning and twisting in convoluted, contradicting truths.

After finishing the fourth novel, I closed the book and paused. What had I just read? Just when I think I am beginning to grasp the Dune series and the author’s many intended messages, it seems I fall short of their intended meaning, just as many do when conversing with the God Emperor, the main character of the fourth novel in many ways. In particular, the fourth book branches off from political intrigue at the mortal level and contemplates what a government would like like if it was controlled from a central religious power that lived virtually forever, since the God Emperor, Leto, part human and part Sandworm, is closer to a divine figure than any, and rules as such, a fusion of religious and political power that transcends merely the pharoic or tyrannical type as seen in Ancient Egypt and Greece.

At the outset we learn that the God Emperor has lived three thousand and five hundred years. His humanity, trapped in a Sandworm body (the beasts of the desert on Arrakis which we see dramatically devouring people in the movies), has dwindled to no more than his face, hands, and his brain, which already is undergoing changes. This religious-empire, with its all-female army entirely devoted to Leto, is superficially, as I have mentioned, a thought expirement of another kind of government. But in the end, due to the Emperor’s near-divinity, I was more struck by the questions this novel uncovered about the nature of Infinity and Chance than about the possibilities of human government. In Leto, we get the closest to a rationlized divine state, by living for longer than any known human and having the prescient ability to know all of the past, present, and future, which produces this fascinating excerpt from Leto’s ‘Stolen Journals’:

“I assure you that the ability to view our futures can become a bore. Even to be thought of as a god, as I certainly was, can become ultimately boring. It has occurred to me more than once that holy boredom is good and sufficient reason for the invention of free will.”

Fascinating, right? The idea that if a God exists, He creates out of boredom? But this boredom is not the kind of boredom we might suspect, like the kind we see with the Greek pantheon of conniving and vengeful gods, who enjoy taking sides in mortal wars and breeding with them to make other gods jealous. This boredom is more accurately described as the opposite of surprise, the repetitive patterns of genetics in contrast with new inventions and genetic abnormalities, the very difference between Fate and Chance, which we find most poignantly expressed in this dialogue between Leo and one of his most faithful servants:

“You will think it strange that I, with my powers, can speak of luck and chance,” Leto had said.

The Duncan had been angry. “You leave nothing to chance! I know you!”

“How naive. Chance is the nature of our universe.”

“Not chance! Mischief. And you’re the author of mischief!”

“Excellent, Duncan! Mischief is a most profound pleasure. It’s in the ways we deal with mischief that we sharpen creativity.”

The often moody God Emperor Leto, who has already lived countless lives through his ancestral memories, loves to be surprised, and hates when he can predict what will happen next. This ability to surprise is the creation-impulse at its heart, the ever-constant temporary state of the universe—which is the only constant thing about it—as Leto describes in another excerpt of his Stolen Journals, which often grace the beginning of the chapters:

“In all of my universe I have seen no law of nature, unchanging and inexorable. This universe presents only changing relationships which are somtimes seen as laws by short-lived awareness. These fleshy sensoria which we call self are ephemera withering in the blaze of infinity, fleetingly aware of temporary conditions which confine our activities and change as our activities change. If you must label the absolute, use its proper name: Temporary.

—The Stolen Journals”

At its heart, the novel (like every novel) struggles to find a place for the brief mortality of Man within this vast Infinity. The human race expands across space, traveling to new planets, violently and peacefully through various forms of government, but still there is a question of the cost of survival, the meaning of Life.

An interesting fact of history in Dune, which is mentioned as happening early on the history of humanity, is the war against the Machine. Due to their power, there was a great revolt known as the Butlerian Jihad against computers, thinking machines, and conscious robots. And unlike the first three novels, where machines were still firmly outlawed, this novel is the first time we are seeing true evidence of this problem surfacing, producing this poignant warning:

“The devices themselves condition the users to employ each other the way they employ machines.”

To combat this, it seems, is through emotions. For instance, Leto claims: “If we deny the flesh, we unwheel the vehicle which bears us. But if we deny emotion, we lose all touch with our internal universe.”

In many ways, this is a reminder that emotion, the ‘internal universe’ as Leto calls it, is precisely what differentiates Human from Machine, the same difference between boredom and surprise, for while the Machine can only act regularly based on a pre-determined, rationalized set of data, humans act on the spontaneity of emotion, the irrationality inherent in that first creation-impulse. No wonder the Greeks believed that first of all there was Chaos!

We see this culminate in the strange relationship between the God Emperor and Hwi Noree, which cannot be physical (Leto no longer has that essential human anatomy) and so is necessarily a sharing of their souls. She perceives the entirety of the God Emperor’s soul and claims that she knows the only thing he understands in the face of all his ancestral memories and the certain knowledge of the future:

“Love, that is what you understand,” she said. “Love, and that is all of it. (…) You have faith in life.…I know that the courage of love can reside only in this faith.”

Thus the condition of humanity, of creation too, is Love, which may be further distilled to this faith in Life, in creation itself. And it takes courage to believe in Life, as Hwi remarks, to believe in this Infinity which we cannot fully understand, nor this strange god of Chance which follows no law, reigning by the lawlessness of Chaos. Yet it is this very Love which, unlike machines, creates that special relationship between humanity and the Infinity, between mortal and divine, that still fascinates us despite all we have “learned” as a species.

Ultimately, the Dune series does not speak to my soul like Tolkien’s novels, where religion is rarely if ever explicitly mentioned, but where nonetheless a particular religiosity resonates inherently through the story and Middle-earth itself. On the other hand, the novels of Frank Herbert, certainly a genius in his own right, stir the intellect of modern Man to see the spirit where there is only cold, dead science—or rather, they remind us of science’s limitations to reach understanding, the beauty of Chance, and the inevitable Mystery of the universe.

Now on to the next!

From the Writer’s DeskI’ve been writing away in my free time, as usual, trying to finish the first draft of the third book in the Realm of Emmeson trilogy before the end of the month. I’d like to get a few revisions done during the beginning of September if I can. This final book has a dragon-god, oracular visions, and a mysteriously unraveling prophecy that has everything and nothing to do with ancient Alchemy, primeval forces, and love…Needless to say, I’m having fun writing it!

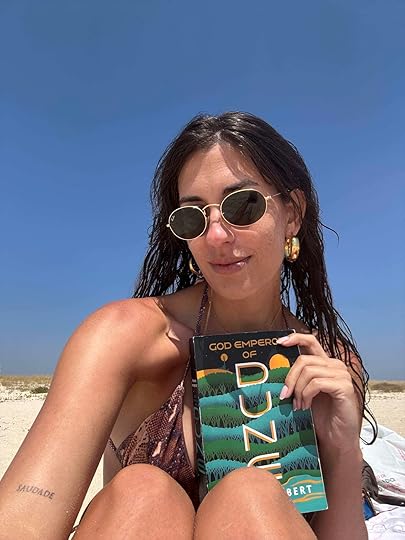

When I’m not writing, I’ve been lounging on the beautiful beaches of Portugal, knee-deep in the Dune series (as can be seen above), which has encouraged me to write without holding back from my intellectual curiosities and philosophical musings:

NEW RELEASES:

NEW RELEASES:

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:BOOK 3 REALM OF EMMESON - First draft

SOFIA BEFORE LOVE (a book of poetry) - Illustrations

Heretics of Dune by Frank Herbert

Iliad by Homer (in Ancient Greek!)

The Gnostic by Jacques Lacarrière

Lyra Mystica by Charles Albertson

Here’s a photo of traditional Portuguese pastries (top: pasteis de nata; bottom left: palmier coberto; bottom right: palmier recheado)!

My other Substack, The Fellowship of the Readers, is slow-reading The Silmarillion over the next year. Join at any time if you are interested in reading or just following along with the occasional quote excerpts that I’ll send out to mark our journey!

A QUOTE:

οἵη περ φύλλων γενεὴ τοίη δὲ καὶ ἀνδρῶν.

φύλλα τὰ μέν τ' ἄνεμος χαμάδις χέει, ἄλλα δέ θ' ὕλη

τηλεθόωσα φύει, ἔαρος δ' ἐπιγίνεται ὥρη:

ὣς ἀνδρῶν γενεὴ ἣ μὲν φύει ἣ δ' ἀπολήγει.

As is the generation of leaves, so is that of humanity.

The wind scatters the leaves on the ground, but the living wood

blossoms with leaves again in the season of spring returning.

So one generation of men will grow while another dies.

—Iliad, Homer, 6.146-9

Vale!

-Zoë

The Sun of God — an epic historical novel set in Ancient Rome

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount special edition hardcover, audiobook)

Imagining the Roman Empire: Essays on Travel & Antiquity in the Mediterranean

(Amazon paperback)

The Song of Gaia (Book #1)

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover, special dust jacket hardcover)

The Pillars of the Sea (Book #2)

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover)

My Sister’s Best Friend (Book #1)

(Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Best Friends & Their Exes (Book #2)

(Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Hot takes on the ancient world by two Classics students and dead language fanatics!

Listen to our new episode:“WORD You Rather: Germanic vs Romance Descendants in English”

Find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and most other podcast streaming services!

MEDITERRA is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 25, 2025

One Hundred Years of D.H. Lawrence

On the eleven-hour and five-minute flight from Los Angeles to Lisbon, I finished reading a collection of D.H. Lawrence’s letters1, and I admit I shed a tear or two. You might know him as the infamous author of several novels, like Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which were banned in England for their “erotic” content and even put on trial. He would be laughing to see the kinds of novels written under the misleading term ‘romantasy’ that now plague the book industry.

But what you might not know about D.H. Lawrence can be gleaned from his letters: that he had an affair with an aristocratic, married German woman, Frieda, that he was mistakenly suspected of being a German spy during the First World War, that he wrote novels and short stories as well as poems, plays, essays, and painted quite well too, and that he traveled not only to Italy (of which he wrote many travel books) but also to parts of the Middle East, Asia, Australia, South America, and the USA and Mexico, even buying a ranch in New Mexico and living there for some time, and lastly, that he died at 44 years old of tuberculosis having published a total of 12 novels, along with around 76 short stories and novellas, as well as countless poems, essays, plays, travel books, and even translations of Italian and Russian works.

Lawrence was born in 1885 and died in 1930, so his collection of letters, along with his other writings, has fermented for one hundred years, and its age, like a rare bottle of wine, shows in the most delightful ways. First of all, he wrote letters. This slow-paced form of communication, which died out with the invention of email, is my favorite way to learn about a time period or historical figure. Letters are intimate and lengthy, relaying gossip, detailed life updates, work feuds, apologies, declarations of love, and recent political news, sometimes all in the same letter. Each recipient (and in some collections, sender) is like a character of a story coming to life between the lines. In Lawrence’s case, many of the friends he wrote to ended up as actual characters in his novels, with one Lady Ottoline Morrell even ceasing to speak with him for ten years because of it. Letters remind us that human nature has not really changed a smudge compared with technological innovations, though some of our customs certainly have (again, cf. the genre of romantasy).

The second tell of his time is that Lawrence traveled by ship and train, made even more obvious while reading his letters on my direct, trans-Atlantic flight. Despite the ease of planes today, Lawrence managed to travel to at least three times as many countries and cities as I have, documenting rural and urban scenes with an attention to detail that either suggests the slow, steady pace of life during that time or my modern, distracted gaze always being pulled to a smartphone screen instead of wandering to the nearest tree or building, even if only out of boredom—or a bit of both, perhaps. By the last letter, written a month before his sudden death, I was flying over the Atlantic Ocean with only a few hours left before landing, and I felt strangely ashamed, knowing I had wasted so much of my time already. I thought that I would be lucky to travel and write half as much as D.H. Lawrence had, even if I live to see twice as many years.

Staying with my grandparents in Portugal reminds me that I can choose to live a slower life. I don’t need to revert to letter writing (although I have tried to keep a letter correspondence with a long-distance friend and found it a much harder task than expected, a skill to be cultivated and admired when done well), but I can put my phone away while on public transit or a walk and look around me instead (you will then notice just how many people are glued to their phone), taking note of the different kinds of trees lining the sidewalk, the color of the sky, the variety of people surrounding me.

My grandparents, who traveled by ship between Portugal and Angola in their younger years, have the patience of a mountain weathering the wind, and on a stroll, they can identify a tree or flower instantly and explain if it can be brewed for tea, or used medicinally, or the fruit it grows. And beyond the local flora and fauna, they have a keen eye when it comes to picking people to keep in their lives and have a broad network of colleagues, friendships, and distant family that were formed in a time without emails, let alone phone calls or text messages. My life would feel very full indeed if I had but a slice of their social life at that age—no, at my age!

So, although I am grateful for the ease and speed of an airplane, I lament the loss of slow living, even letter writing, for it reflects a time when basic communication could be considered an art form, not flat, emotionless phrases that leave us farther apart than ever. Jet lag is the physical reminder that traveling fast is, in many ways, unnatural, but the distance we cover with our bodies does not always translate to how far our minds and souls have traveled, especially if we are always sucked into the void of our handheld screens. For in the time we gain with our modern technology, it seems we lose something vital about living, that human instinct and sensuality which D.H. Lawrence always encouraged to the day he died, which can be found even in the most mundane and earthly. So get out, take a walk, and look around you, lest life, real life, pass you by as quickly as the airplanes in the sky.

Vale!

-Zoë

A view from the Parque dos Poetas in Oeiras, PortugalFrom the Writer’s Desk

A view from the Parque dos Poetas in Oeiras, PortugalFrom the Writer’s DeskStill working on the last book of my fantasy series, The Realm of Emmeson, though it goes in fits and starts instead of smooth and steady while I travel and spend time with family abroad. It fits the feel of the story anyhow, which switches perspective every other chapter, and includes traveling scenes as well, if only to the Netherworld…

I’m a bit sad that I don’t have enough time at the moment for the illustrations of my poetry book, since it’s nearly ready to publish otherwise, cover and formatting and all. At some point I’ll do a cover release, maybe once I have the drawings done. I fear this is a harbinger of the future, though, when I will have to juggle school, writing, and my personal life again—and writing is often the first to go. Still, I hope to have the book published early next year at the very latest!

NEW RELEASES: LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:BOOK 3 REALM OF EMMESON - First draft

SOFIA BEFORE LOVE (a book of poetry) - Illustrations

Iliad by Homer (in Ancient Greek!)

The Gnostic by Jacques Lacarrière

Lyra Mystica by Charles Albertson

Here’s a photo of my Portuguese grandmother, Maria dos Anjos, and me!

My other Substack, The Fellowship of the Readers, will start slow-reading The Silmarillion on July 29th. Check it out if you are interested in reading or just following along with the occasional quote excerpts I’ll send out to mark our journey!

A QUOTE:MY BOOKS“I got the blues thinking of the future, so I left off and made some marmalade. It’s amazing how it cheers one up to shred oranges or scrub the floor.”

—D.H. Lawrence to A.W. McLeod, 17 January 1913.

The Sun of God — an epic historical novel set in Ancient Rome

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount special edition hardcover, audiobook)

Imagining the Roman Empire: Essays on Travel & Antiquity in the Mediterranean

(Amazon paperback)

The Song of Gaia (Book #1)

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover, special dust jacket hardcover)

The Pillars of the Sea (Book #2)

(Amazon, discount paperback, discount hardcover)

My Sister’s Best Friend (Book #1)

(Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Best Friends & Their Exes (Book #2)

(Amazon, discount paperback, audiobook)

Hot takes on the ancient world by two Classics students and dead language fanatics!

Listen to our new episode:“WORD You Rather: Germanic vs Romance Descendants in English”

Find it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and most other podcast streaming services!

MEDITERRA is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

1Thank you to my friend, fellow Classicist, and co-author Grace DeAngelis for this lovely gift!

July 20, 2025

Where are All the Women in Middle-earth?

Anyone who has read Tolkien (or watched the movie adaptions, especially) often comes away with the idea that women are largely absent from Middle-earth save for three major characters—Galadriel, Éowyn, and Arwen (the latter playing a greater role in the movies than the books)—whose special powers and heroic attributes do not, however, make up for how few they are in number.

As much as I appreciate why recent Tolkien “media” (Rings of Power and the War of the Rohirrim, which I cannot in good conscience call adaptations) attempts the female warrior trope—ironically not done so authentically as Éowyn in the original books and movies—I think we are missing a glaring point that Tolkien makes about the role of women in Middle-earth, that has its echoes in the ancient societies and mythologies he channeled into his storytelling.

We shouldn’t feel too bad about our ignorance on the subject of women in Middle-earth. Many of the great men in the story make the same mistake, though swiftly corrected by an Elf or Wizard with much more wisdom than them. For instance, when Boromir doubts the stories told about Fangorn Forest, which he brushes aside as old wives’ tales told to children, Celeborn tells him not to “despise the lore that has come down from distant years; for oft it may chance that old wives keep in memory word of things that once were needful for the wise to know.”

King Théoden makes a similar mistake about the Ents, disbelieving their existence as mere legends in songs and stories taught to children, to which Gandalf gently berates him:

“‘…Is it so long since you listened to tales by the fireside? There are children in your land who, out of the twisted threads of story, could pick the answer to your question. You have seen Ents, O King, Ents out of Fangorn Forest, which in your tongue you call the Entwood. Did you think that the name was given only in idle fancy?’

After the Battle of Pelennor Fields, when Aragorn is tending to Éowyn and the other wounded, we see this ignorance in the learned Healer, who scoffs at his request for kingsfoil. Ultimately, only an old housewife recalls the lore of Athelas as a healing plant in the hands of the king, thanks to an old rhyme:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedWhen the black breath blows, And death's shadow grows, Come Athelas! Come Athelas! Life to the dying, In the king's hand lying!In these glimpses behind the male-dominated warfront, we see a more textured Middle-earth, where women as wives, mothers, and nurses keep all of the legends that we read about alive by telling stories to children by the fireside, a role Tolkien valued so much that The Hobbit was born out of all the fireside stories he would tell his children as they were growing up. In his essay “On Fairy Stories,” Tolkien further claims that nurses “were sometimes in touch with rustic and traditional lore forgotten by their ‘betters.’” As an orphan at the age of thirteen, Tolkien must have felt keenly the missing lore and legend that was usually passed down from mother to child, and regretted that England itself had no body of legends comparable to other ancient cultures, like the Greek, Italic, or Nordic epics.

This is not to say that women’s only role in Middle-earth was the traditional housewife and mother, or that by being one, they could not be the other. Galadriel, we may remember, is a wife and mother, but she is also arguably the most powerful Elf in all of Middle-earth, Queen of Lórien and one of the three Ringbearers; Éowyn is charged with the care of the elderly, women, and children instead of fighting, but even when she disobeys this duty, she fulfills an age-old prophecy and defeats the Witch King of Angmar, which no man (or wizard!) had been able to kill; and even Arwen, who neither fights nor carries much apparent power, is just as necessary for restoring the line of Kings to the throne of Gondor as Aragorn is, and has the same illustrious lineage, if you trace it far back enough, to Beren and Lúthien.

Lastly, I might note here that both Aragorn and Faramir, the lead captains of the armies battling Sauron, ultimately settle in domestic settings equal to that of their wives, Arwen and Éowyn; Tolkien understood the nobler state of men and women as residing in the peace of the home, not at war, and rewards his heroes (both men and women) with marriage and posterity, not merely glory and renown.

Weaving as MagicAs much as I can say that at the heart of Tolkien’s stories are women, war in Middle-earth is very much ‘the province of men,’ as Éomer succinctly tells Éowyn in the movie adaptation just before her valiant deeds in battle. Therefore, much of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit (centered around two major wars) revolve around men and their storylines. Yet as we saw with the various reminders to heed old wives’ tales, women have their own provinces of wisdom and power in addition to their capabilities in untraditional settings.

Along with nursing children and telling stories by the fire, women were also traditionally responsible for weaving all the clothing worn by the household, a skill that manifests to varying degrees of magical effect in Middle-earth. Even Galadriel, as powerful as she is, wove the Elven cloaks which were given to the members of the Fellowship, a sign of her favor for them, and which contain marvelous Elvish “magic”:

“They are Elvish robes certainly, if that is what you mean. Leaf and branch, water and stone: they have the hue and beauty of all these things under the twilight of Lórien that we love; for we put the thought of all that we love into all that we make. Yet they are garments, not armour, and they will not turn shaft or blade. But they should serve you well: they are light to wear, and warm enough or cool enough at need. And you will find them a great aid in keeping out of the sight of unfriendly eyes, whether you walk among the stones or the trees.”

Weaving as “magic” occurs elsewhere in Tolkien’s stories: in the Tale of Tinúviel, about the love between Elf maiden Lúthien and mortal Man Beren, weaving and an accompanying song are used by Lúthien to escape imprisonment. After mixing water and wine while singing a song to lengthen her hair, she “laboured with the deftness of an Elf, long was the spinning and longer weaving still,” until “of that cloudy hair Tinúviel wove a robe of misty black soaked with drowsiness more magical far than even that one that her mother had worn and danced in long ago.”

Interestingly, this enchantment of an Elf maiden’s hair is seen elsewhere. In The Unfinished Tales, we are told of Galadriel’s golden hair, of which “the Eldar said that the light of the Two Trees had been snared in her tresses.” This gave way to the rumor that Galadriel’s hair had given Fëanor himself the idea of imprisoning and blending the light of the Two Trees, which led to the creation of the Silmarils. Fëanor indeed asked Galadriel for strands of her hair three times, to which each time she refused. What a lovely nod to the secret power of her hair and its entanglement with the history of the Silmarils that Galadriel gave Gimli three strands!

But to return to the idea of women weaving, Tolkien is not the first to light upon the “magic” of a loom and thread. In the Homeric world, there are several instances of weaving as a form of enchantment. Both Circe and Calypso, goddesses renowned for deceiving and entrapping men on their islands, are depicted as weaving and singing to lure men into their homes. And of course, Penelope, wife of Odysseus, keeps her greedy suitors at bay by weaving a shroud for Laertes during the day and unraveling it by night, promising only to wed one of them when she finishes the shroud. And in Ancient Greek religion, it was the three Fates, the Moirai (Μοῖραι), who spun the fates of mortals: one spun the thread from the spindle, the other measured the length, and the last cut it, a metaphor for the creation, allotment, and ending of a mortal life.

The Fabric of StorytellingAs a scholar of ancient cultures and one who was able to read the Odyssey in Ancient Greek at an early age, Tolkien was certainly aware of the magic of weaving, the power of song, and the wisdom inherent in old wives’ tales. For example, Tolkien surely knew that although Odysseus was the one to go off to war and devise tricks against the Trojans (and we might add that Odysseus strongly resisted going to war, given that his son, Telemachus, was just born), Penelope must do her duty as well and fight her own battles, using her own tricks and deceptions, a fitting match for her husband of many wiles.

We can imagine that in Middle-earth, just as in the ancient cultures of our world, women are responsible for clothing, feeding, and rearing, and yet that these skills, which we might call knowledge, harbor deeper dimensions of power and subtle magic: songs sung while weaving or nursing by the fire keep the legends and history of the past alive in the present. Although Tolkien often follows the warriors into battle (he went to battle himself and lived to tell the tale), he gently reminds us, like Celeborn with Boromir and Gandalf with Théoden, that there is a secret world of magic and power to be found among those who are so often left out of the epic songs, since they are usually the ones singing them. Thus, women are to thank for preserving the hard-earned wisdom of ages past, for weaving the tapestry of our stories into song—and by extension, Tolkien’s own story, the story we love so much today, in part because it may just remind us of the wonder we found in stories told to us as children.

Perhaps, then, we can understand why Tolkien assigns the song of Lúthien as the most fair to be ever sung, an enchantment woven like the threads of a loom, and which has the greatest power of all: to bring the dead back to life…

“The song of Lúthien before Mandos was the song most fair that ever in words was woven, and the song most sorrowful that ever the world shall hear. Unchanged, imperishable, it is sung still in Valinor beyond the hearing of the world, and listening the Valar are grieved. For Lúthien wove two themes of words, of the sorrow of the Eldar and the grief of Men, of the Two Kindreds that were made by Ilúvatar to dwell in Arda, the Kingdom of Earth amid the innumerable stars. And as she knelt before him her tears fell upon his feet like rain upon stones; and Mandos was moved to pity, who never before was so moved, nor has been since.”

MEDITERRA is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

July 10, 2025

Father Sky, Mother Earth

Did you know the word for God in many Indo-European languages—deus in Latin, devás in Vedic, día in Old Irish, dievas in Lithuanian—once meant ‘shine’?

Those elusive ancestors of the cross-continental cultures we know today as many different peoples once looked up to the sky shining with light and saw irrefutable power, something to be revered and feared.

As this ‘shining’ (from the root *dyew-) bound itself with the light of day—or the winking light of nightly stars—it took on another shade of meaning: sky, or heaven. Much like German’s Himmel does not differentiate between heaven and sky, long ago the Proto-Indo-Europeans gazed up at both a heaven and a sky.

In my divided, modern mind, I wonder which, truly, came first: a word to describe the physical aspects of photons streaking across the aether, or a recognition of divinity in that celestial gleam, same as how consciousness alights in the eye of a living being. Perhaps neither. Or rather, both. To gaze upon any light, whether it be the sunlight or the stars, was to know a god. It is not a coincidence, after all, that the PIE root *weyd- ‘to see’ developed the significance ‘to know’ in many daughter languages. Thus, the root *dyew-, that glittering firmament, was god.

Later (how much later cannot be well ascertained behind the veil of prehistory), this *dyew- ‘god,’ ascended cosmic supremacy, perhaps around the same time as a patriarchal system was established in society, and accepted the title of *ph₂tḗr, ‘father.’ Not, in our limited modern view, merely to suggest paternity of the universe (which, after all, included many other productive agents), but to establish the head of a family, much like the Ancient Roman pater familias.

As the Indo-Europeans branched off and spread throughout the far reaches of Europe and Asia, they took this Father Sky with them, imposing both a patriarchal religion and society upon those even more mysterious ‘indigenous’ civilizations, theorized to be matriarchal. But these cultures left their mark, not just genetically through forced, gradual intermarrying, but also in religion. Almost all daughter languages have a ‘Mother Earth’ (a concept not restricted to these cultures but found all over the world), yet it is difficult to trace the name of such a goddess back to a specific PIE root. Still, we find in archeological digs countless Mother figurines—symbols of fertility and earth, we guess—and massive womb-shaped tombs that suggest these people worshipped a goddess.

I saw one of these womb-shaped tombs in Évora, Portugal, the Great Dolmen of Zambujeiro. Over time, those monolithic stone slabs were overgrown with grass and appeared as a large hill in the landscape for centuries and centuries. Archaeologists and tourists have beaten dirt from the stones underfoot, and the tomb resurfaced—surely before it had been meant to—for us to wonder at its significance.

The dead were buried inside in the fetal position alongside objects necessary for daily life—ceramic, jewelry, weapons, sewing materials, and the like—preparations for the journey ahead. The opening of the womb-shaped tomb faced the east and the rising sun, but also where the first full moon after the spring equinox appears on the horizon during the moon’s metonic cycle. Clearly, they believed in an afterlife, maybe even rebirth, the soul’s ability to traverse the Land of the Dead and ascend once more.

Later (again, allow me to brush aside millennia and tenuous evidence with this one word), a reluctant partnership seems to have arisen between Father Sky and Mother Earth. In Ancient Greece, for example, we see various iterations of this cosmic marriage in Ouranos and Gaia, Cronos and Rhea, Zeus and Demeter. Thus, modern science confirms what the ancients already knew: photons and oxygen swirling in the shining sky marry with plants and animals bound on Earth to create life.

As earth-bound creatures, our lingering worship of Mother Earth in the face of the powerful Father Sky should not come as a surprise. One may gaze at the sky and trace patterns of Fate across the shining stars, but it is to the bosom of the earth we shall ultimately return.

Autorae EpistulaI have decided to try something new: blend my author website’s newsletter with my personal blog, MEDITERRA, here on Substack. From now on, my goal is to send out reflective pieces on writing, books, Tolkien, Classics, language, and more, while also including author updates, personal news, what I’m reading, and quotes that I included in my other newsletter.

The website newsletter, on the other hand, will be reserved for those who want explicit updates about new book releases, interviews, discounts, and other relevant author information, rather than regular updates or blog posts. I hope you enjoy this new phase of MEDITERRA as my Autorae Epistula, or ‘Author’s Letter’!

FROM THE WRITER’S DESK:Currently, I am writing the third book of my ancient Mediterranean mythology-inspired portal fantasy series, The Realm of Emmeson, and I’ve enjoyed the amount of research going into this one. My interests in Ancient Greek and Egyptian myth, their eventual mingling and cross-breeding in the ancient city of Alexandria, and the related Hermetic and gnostic philosophies entangled with the mysterious study of alchemy, which could only have been produced in such an intellectual, cosmopolitan scene steeped in a long, solemn religious history.

Each novel in this series has brought out a different atmosphere—The Song of Gaia sought inward, both in the main character, Alexandria, and the city she discovers; The Pillars of the Sea explored outward, traversing the realm of Emmeson through familiar and new landscapes of Homeric and Egyptian mythology; lastly, the third book will turn intellectual and mystical at the same time as it extends the quick-paced, action-packed storyline of the second book into the culmination of the illusive prophecy.

NEW RELEASES: LEARN MORE

LEARN MORE

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:

LEARN MORECURRENT PROJECTS:BOOK 3 REALM OF EMMESON - First draft

SOFIA BEFORE LOVE (a book of poetry) - Illustrations

Iliad by Homer (in Ancient Greek!)

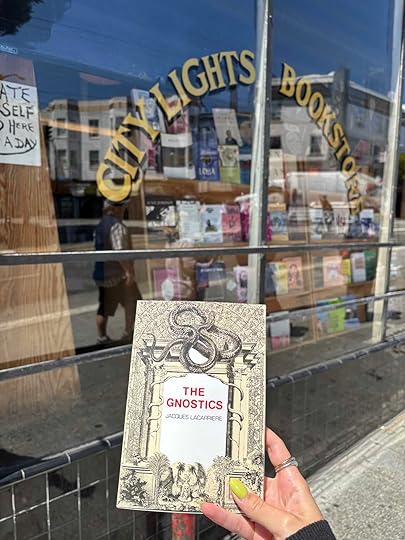

The Gnostic by Jacques Lacarrière

Lyra Mystica by Charles Albertson

I recently visited San Fransico and went to City Lights Bookstore. Usually, I prefer used bookstores, but I found an intriguing copy actually printed by the bookstore, which I could not resist buying, if only as a memento of my visit:

My other Substack, The Fellowship of the Readers, will start slow-reading The Silmarillion on July 29th. Check it out if you are interested in reading or just following along with the occasional quote excerpts I’ll send out to mark our journey!