Jason J. Stellman's Blog

October 7, 2012

"Add to Your Faith"

The second part of Lane Keister's response to me concerns II Peter 1:3ff. I wrote, "All the elements of Jesus’ and John’s and Paul’s paradigm are there: God’s divine power causes us to partake of the divine nature (Peter’s way of talking about what Paul speaks of in terms of the indwelling of the Spirit of the risen Christ). He then says that our faith, far from being alone, is supplemented with spiritual virtues, the final and greatest of which is 'love.' Finally, he says that we must 'practice these qualities,' for 'in this way' we will gain our eternal inheritance."

The second part of Lane Keister's response to me concerns II Peter 1:3ff. I wrote, "All the elements of Jesus’ and John’s and Paul’s paradigm are there: God’s divine power causes us to partake of the divine nature (Peter’s way of talking about what Paul speaks of in terms of the indwelling of the Spirit of the risen Christ). He then says that our faith, far from being alone, is supplemented with spiritual virtues, the final and greatest of which is 'love.' Finally, he says that we must 'practice these qualities,' for 'in this way' we will gain our eternal inheritance."Lane responded:

Jason says something with which I agree, but maybe not with the same slant. He says that faith must be supplemented. I agree. But doesn’t that mean that faith is one thing, and the things that accompany it are other things, at least distinct, even if not inseparable?Yes, faith is "one thing" that must be supplemented with "other things," and as James says, "faith alone" (or, faith without those other things) is insufficient. So Peter's insistence that we "add to our faith" the Spirit-wrought qualities he lists in vv. 5-7 (virtue, knowledge, self-control, steadfastness, godliness, brotherly affection, and love) is similar to that of James's point about "faith alone, apart from works" not justifying. Paul makes a similar point (albeit in a poetic context) when he says that if he has "all faith" so that he could move mountains "but has no love," it profits nothing.

The fact that these three writers insist that faith must be "supplemented" with other spiritual fruit causes me to scratch my head at Lane's question about these things being "inseparable" from faith. If they were inseparable, then it seems to me somewhat superfluous for Paul, James, and Peter to insist that those who have faith strive to also have these other things.

Lane continues:

Lastly, what is the way in which we obtain the eternal inheritance? The immediate context of the statement is not the virtues that Peter listed, but rather the idea of not falling. The passive voice of “will be supplied” in 2 Peter 1:11 is important here, as well. It is probably a divine passive, with God the implied subject. And who makes the calling and the election? We can add to our assurance, but not to our hope, for as 1 Peter says, we were born again to a living hope. We do not give ourselves the new birth any more than we gave ourselves physical birth.There's a clear progression in Peter's thought in vv. 3-11 to which I am not sure Lane is doing justice. I will try to elucidate that progression by working backwards from the end to the beginning and asking a series of questions taken directly from the text:

How will we be richly provided our entrance into the eternal kingdom? By not falling. How do we not fall? By confirming our calling and election. How do we confirm our calling and election? By not being unfruitful. How do we not be unfruitful? By adding to our faith the spiritual fruit Peter lists.

Thus Peter is saying the same things that Jesus, Paul, James, and John said, namely, that it is by living out the Spirit-wrought life of Christ that we will enter heaven, which power we have because of Jesus' death and resurrection.

Lane concludes:

We enter into the eternal state not because of our works, but not without our works, since they are the inevitable result of God’s grace. 2 Peter is not saying that we gain an entrance into the eternal state because of what we do. Otherwise, why would he write 2 Peter 1:3, wherein ALL things necessary for life and godliness are given to us as a gift?Yes, we enter not by works nor without works. But Lane's statement that these works are "the inevitable result of God's grace" is incorrect. In Gal. 5 (which we discussed in my prior response to Lane), Paul explicitly tells the Galatians that if they seek justification by circumcision instead of by faith working through love, they have "fallen from grace" and "severed themselves from Christ." These kinds of warnings would not arise from an inevitable result or foregone conclusion.

Finally, in my opinion Lane is forcing a false dilemma upon Peter by insisting that either his own Reformed understanding of the passage is true, or else salvation is "by works," "because of what we do," and earned rather than gifted. But the problem for Lane is that the Catholic position is not found in either of these options, meaning that he is responding to a position that no one has even suggested.

To be as clear as I possibly can, the sinner is saved by God's grace alone, and not because of his own works (of the law or otherwise). However, once a child of God who "partakes of the divine nature," the believer must do all the things Peter says to do in this passage, for "if he does this" then by God's grace "he will never fall."

Published on October 07, 2012 21:08

October 4, 2012

Whose Bible Is It Anyway?

As online discussion and debate about Catholic/Protestant issues have been pretty abundant of late, I wanted to share a frustration that I have been feeling.

As online discussion and debate about Catholic/Protestant issues have been pretty abundant of late, I wanted to share a frustration that I have been feeling.If a Catholic argues with a Protestant based upon the infallible pronouncements of some ecumenical council or another, he will be immediately told that such a tactic is out-of-bounds since Protestants don't consider Tradition or Church dogma to be infallible. So, we're told, in order to fairly engage the Protestant, the Catholic must do so on the basis of what they both believe is infallible revelation, namely, the Bible.

This is why I have made it my aim to try to make a case for some basic Catholic positions from Scripture here and elsewhere. But when I do, here're the responses I get:

Jason, ever since you resigned from the PCA I knew it was too late to debate with you on these issues.... Now it is way too late to bring up counter-arguments. I just want to point out that the answer that you gave to my question still sounds Protestant to me.My point in adducing these responses is to point out that this seems like a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don't type of situation. If we argue with Catholic presuppositions we are begging the question, but if we argue from Scripture, we are dismissed for sounding too Protestant.

Why didn't you include in your answer the many requirements of the Roman Catholic Church?

You still sound Protestant to me.

Maybe the problem is that we are only talking about Scripture, but that's only part of the original revelation that God has given to us. Wouldn't you now as a Roman Catholic (you are for all intents and purposes all the way across now I believe) affirm that the deposit of faith is that which is laid down in Scripture but also that which has been passed down via oral tradition?

I don’t really know why you are shying away from including the very clear statements of Trent on justification.

Come back to us when you have considered what Trent said on justification (and related concepts like the sacraments) in light of the Scriptures.

Now what I’m suggesting is that you move onto Trent where we really get into the distinctions between Catholic and Protestant formulations of justification.

Jason has made so many statements that do not set apart Roman Catholicism by appealing to Scriptures that could be taken either to support Catholic or Protestant understandings of justification. My suggestion was to go to Trent because here you have statements that stand in stark contrast to Protestant dogma.

So if we are going to discuss justification and related concepts, don't you want to challenge us with this other infallible source on the matter? Shouldn't we be exegeting the extra-biblical infallible sources with the same intensity as the biblical infallible sources on what we are to believe concerning justification and salvation?

There is so much interesting material in the history of justification. It's just a shame to leave that alone since there are so many Catholic "infallible" statements on justification which stand in such stark contrast to Protestant dogma. IOW, between Catholics and Protestants, there is far less debate on what Trent says about justification than on what Paul and James say on it.

As a Catholic you cannot argue solely on the basis of Scripture. We can.

Yet despite these kinds of objections, I plan to continue to argue from Scripture -- not for every single technical aspect of Catholic dogma (for not even all Protestant formulations can be prooftexted with explicit statements from the Bible), but rather for the basic elements of Catholic soteriology. As I have been attempting to demonstrate, things like the progressive nature of justification, the efficacy of baptism, and the contributory nature of Spirit-wrought works of love are clearly taught in the New Testament. And I will also continue to maintain that, often times, the reasons for rejecting these ideas appear to be ones that have little to do with the biblical texts under consideration, but have much more to do with prior-held systematic paradigms that stifle the Scriptures and prohibit them from speaking for themselves.

I know a lot of you will think I am dead wrong on this. Fine. Then let's return to the source of infallible revelation that we all agree is primary and seek to discern together the gospel contained therein.

Published on October 04, 2012 15:28

September 30, 2012

Divine Delight in the Useless and Unnecessary

Later in the week I hope to publish the second installment of my response to Lane Keister, but before I do I wanted to pass along something I read the other day that really bore witness to what I've been thinking about for a while, and which was written in much better prose than I'll ever pull off.

Later in the week I hope to publish the second installment of my response to Lane Keister, but before I do I wanted to pass along something I read the other day that really bore witness to what I've been thinking about for a while, and which was written in much better prose than I'll ever pull off.But first I need to back up a bit....

Not many of you know this, but I am working on a novel called That's Me in the Corner, and a week or so ago I wrote the following passage:

"I don't drink to get drunk or have coffee to wake myself up. I just do these things because I like to, for their own sake, even if there's no tangible benefit. In fact, even though I can't explain it, the pointlessness of much of what I do is precisely why I like doing it so much."A day later I came across a statement from Aristotle in which he said that the best activities are the most useless. "Hmm," I thought, "apparently I'm an Aristotelian. Who knew?" Then, just yesterday I was reading the first volume of Mark Shea's Mary, Mother of the Son, in which Shea was responding to those who would ask why Mary is "necessary" and the saints "useful" for us today. He writes that God sees fit to work in the way he does simply because he lovingly feels like it:

"This leads to some startling realizations. For example, it leads to the realizations that life is as much about play as it is about work. It leads to the subversive possibility that God is not a human resources manager fretting about economic theory, parsimonious allocation of limited glory resources and the need to eliminate an oversized workforce of saints who are making his job unnecessary. It leads to the possibility that eternal confusion awaits all those with the notion that the glory of God is a zero-sum game."Shea then goes on to cite Robert Farrar Capon's The Supper of the Lamb: A Culinary Reflection, in which the author insists that "the world will always be more delicious than it is useful." Creation is "the orange peel hung on God's chandalier, the wishbone in his kitchen closet. He likes it; therefore it stays." Shea concludes:

"In Mary, the whole of God's delight in us could be seen at its most playful and at its most solemn, involving us in his life and work, not because he needed us, but because he rejoiced to have it so.In short, God chose Mary as he chose us: not because he needed her, but because he loved her freely."Who, Catholics denyers of divine sovereignty?

Published on September 30, 2012 20:36

September 25, 2012

On Faith, Hope, and Love

Over at Green Baggins, Lane Keister has published the second part of his response to me, which I will interact with here (although my reply will deal with the Galatians, II Peter, and James sections in three distinct posts). In the comment to which Lane is responding I cited Paul:

Over at Green Baggins, Lane Keister has published the second part of his response to me, which I will interact with here (although my reply will deal with the Galatians, II Peter, and James sections in three distinct posts). In the comment to which Lane is responding I cited Paul: You are severed from Christ, you who would be justified by the law; you have fallen away from grace.... For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision counts for anything, but only faith working through love.... For the whole law is fulfilled in one word: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” ... But I say, walk by the Spirit, and you will not gratify the desires of the flesh.... But the fruit of the Spirit is love.... the one who sows to the Spirit will from the Spirit reap eternal life. (vv. 5:4, 6, 14, 16, 22; 6:8)And then wrote:

Here we see Paul echoing Christ by saying that love of God and neighbor fulfills the law, but also adding that this is only possible through the NC gift of the Spirit, which he calls “walking in the Spirit.” This fruit-bearing, far from being a veiled attempt at self-righteousness, is the very “sowing to the Spirit” that will enable us to “reap eternal life.”Lane responds:

By way of response, I would point to Galatians 3:1-6, which proves that the gift of the Spirit comes by faith through hearing.Of course, there is no disagreement here. Paul is clear that the gift of the Spirit comes not from the works of the Mosaic law, but through hearing with faith. He continues:

And what IS the gift of the Spirit? Well, it has several components to it. Union with Christ is the over-arching category (see Ephesians 1:3-14). Within that category is justification and sanctification. With that structure in mind, we ask this question: for what does “faith working through love” avail? While Jason does not specifically answer this question, he does seem to point in the direction that it avails for obtaining eternal life. I would answer that the text is saying that faith working through love avails for the hope of righteousness. The hope means that it is something we do not have yet. What is the hope of righteousness? It is the thing for which righteousness hopes. This implies that we have the righteousness now, but we do not have the thing for which righteousness hopes, which is glorification.Lane is correct, I am saying that faith working through love avails for final justification and our ultimate entrance into eternal life. When Paul insists to the Judaizers that "circumcision avails nothing," he is explicitly addressing those who would be "justified by the [Mosaic] law," and further, his formula of faith working through love is, as I argued, synonymous for him with the "sowing to the Spirit" which, he says in the next chapter, will result in our "reaping eternal life" (6:8).

Lane then says that what faith working through love avails for is the "hope of righteousness," or, glorification. But I do not necessarily disagree with him here. The believer, as he lives a life of living faith which works through love, will thereby be granted on the last Day to enter fully into the eternal inheritance that Jesus won for him by his cross and resurrection. Perhaps Lane's disagreement with me stems from his idea that justification is a once-for-all event rather than something that we receive initially, grow in, and then are fully granted on the last Day. But I would suggest that the more fully-orbed understanding of justification (one with initial, ongoing, and future elements) will better allow Paul to simply speak for himself in this text. After all, it is pretty obvious that the apostle's formulation, "faith working through love avails for ________" should end with the word "justification," since he just finished telling "those who would be justified by the law" that "circumcision avails nothing."

Lane continues:

The thing that counts is faith. It is gratuitous to assume here that “faith working through love” is actually just one idea. As Phil Ryken says in his commentary, “faith is faith and love is love.” The passage certainly says that you cannot separate faith and love.This is extremely confusing. On the one hand Lane is insisting that we must not assume that faith and love are one idea, but then in the next breath says that "you cannot separate faith and love." This is odd, since it is those who hold Lane's position, and not me, who insist that true faith inevitably issues forth in works of love as a matter of course. I, on the other hand, have been arguing all along that faith is one thing, and works of love are another (seemingly following Ryken). This is why (1) James can say that "faith alone" cannot justify if works of love are not also present, (2) Paul can say that if he has faith without love, it profits him nothing, and (3) Peter can say that we must "add to our faith... love." So it would seem to me that it is Lane who imports works of love into his definition of saving faith, such that the latter necessarily includes the former, whereas I have been saying all along that faith alone is dead, unless it is "active along with works" of love (to borrow James' phrase).

But that does not mean that we are justified by faith formed by love.Not to belabor the point, but Paul is addressing those who would be "justified by the law," and who express that desire by "accepting circumcision." He then says that "circumcision avails nothing, but faith working through love." There is absolutely no textual reason to deny that what circumcision avails nothing for, but what faith working through love does avails for, is justification. And as I said above, Lane's insistence that what faith working through love avails for is the hope of righteousness is a false dilemma.

The thing that avails is faith, and that faith, in addition to justifying by its instrumentality, also works through love. Why, then, did Paul add the phrase “working through love?” It is because he is opposing the idea of faith working through love to the idea of circumcision in verses 3, 6, and verse 7 (through the implied antagonists). In other words, Paul adds the thought of faith working through love in order to tell us that it must be a genuine faith, not one that relies on external things like circumcision, or baptism, hem, hem.Lane here is altering Paul's actual words in order to make them fit with his theology. Paul does not say, "Circumcision avails nothing for glorification, but faith does, since it alone justifies. But after we are once-for-all justified, we do works of love as a matter of course, which works play no role in our receiving eternal life." That is at best a strained example of exegetical gymnastics.

What Paul in fact says, is this: "You who want to be justified by the law by receiving circumcision are severing yourselves from Christ. Circumcision avails nothing for attaining our inheritance, but faith working through love does. This love fulfills the law and is the fruit of the Spirit, and if you sow to the Spirit, you will reap eternal life."

In a word, one of us is torturing the text. I'll let you decide which reading of Paul is less violent to his actual words. My hope is that through these kinds of exchanges we may all grow into a deeper understanding of the gospel as announced in Holy Scripture.

Published on September 25, 2012 12:45

September 15, 2012

The Walls of a Playground

Whenever I am in Europe my reading always gravitates toward Chesterton. At the moment I am in Barcelona (whose nightlife is a delicate balance between anarchy and revelry on the one hand, and, umm... that's pretty much it), and I have been reading and reflecting on Chesterton's ideas about asceticism and conditional joy.

Whenever I am in Europe my reading always gravitates toward Chesterton. At the moment I am in Barcelona (whose nightlife is a delicate balance between anarchy and revelry on the one hand, and, umm... that's pretty much it), and I have been reading and reflecting on Chesterton's ideas about asceticism and conditional joy.It is quite popular among many Christians to insist that any works done by believers, even if they are Spirit-wrought, cannot contribute to our receiving our eternal inheritance, for if they did, we would be robbing God of the glory due him for our redemption from sin and death. Chesterton rightly rejected this inverse porportionality between God's work and ours, as though God's glory were a zero-sum game according to which anything we contribute necessarily diminishes his divine contribution. Rather, he insisted, the key to asceticism (which comes from the word denoting the practice of an athlete for his sport) is the paradox that the man who knows he can never repay what he owes will be forever trying, and "always throwing things away into a bottomless pit of unfathomable thanks."

In a word, the key to asceticism is love.

Chesterton illustrates his point by considering the romantic love between a man and a woman. If an alien culture were to study us, they might conclude that women are the most harsh and implacable of creatures since they demand tribute in the form of flowers, or exceedingly greedy for demanding a sacrifice of pure gold in the form of a ring. What such an assessment obviously fails to see is that, for the man, the love of the woman cannot be earned or deserved, and this, ironically, is why he will be forever attempting to do so.

When it comes to our relationship with God, it is equally wrong (indeed infinitely more so) to think that we by our acts of love and sacrifice can somehow buy his favors or earn his eternal smile. But this does not preclude our good works. In fact, our own asceticism and love are conditions, but only in a nuanced sense. They are not conditions in a quid pro quo, I'll-scratch-your-back-since-you-scratched-mine kind of way, but rather they are the wondrous and mysterious conditions attached to a wondrous and mysterious gospel.

As expected for those who know Chesterton, he appeals to myths and fairy tales to substantiate his point. If, when Cinderella's fairy godmother told her that she must leave the ball by midnight, the princess had objected to such an arbitrary demand, the answer she would have received would have been, "If you want an explanation for that, you may also want one for the fact that you get to attend the ball at all (and that, my dear, is something better enjoyed than studied)." In other words, with extraordinary blessings come ordinary conditions, and meeting those conditions is not a bribe, but is simply the context in which those blessings are to be experienced. Exhibiting the proper traits, or meeting the stipulated conditions, out of love to the giver of the blessings promised, is the most natural thing in the world. And contrariwise, the joyful asceticism that exults in sacrifice for one's lover or benefactor is never done as a begrudging form of extortion. In one of my favorite passages of Chesterton's he says:

"Surely one might pay for extraordinary joy in ordinary morals. [The notorious libertine] Oscar Wilde said that sunsets were not valued because we could not pay for sunsets. But Oscar Wilde was wrong; we can pay for sunsets. We can pay for them by not being Oscar Wilde."

Likewise (to quote Chesterton again), "we can thanks God for beer and burgundy by not drinking too much of them."

My point in all this is to say that any understanding of the Christian life that sees the believer's Spirit-wrought works of sacrifice as being necessarily non-contributory (since otherwise we would run the risk of robbing God of glory) is an understanding of the Christian life that fails to understand love as the fulfillment of the law, and which instead sees law-keeping as a purely external work of the letter rather than an internally-wrought fruit of the Spirit. And perhaps worse, such a suspicion of the valuable and contributory nature of our works of love and sacrifice runs the risk of seeing God as merely a Judge, and not as a Father.

Yes, Chesterton says, Christianity has walls. But those walls are not those of a prison, but rather are the walls of a playground.

Published on September 15, 2012 05:57

August 26, 2012

The Destiny of the Species: The Chicken and the Egg

In the third chapter of The Destiny of the Species I argue that the only clear vantage point from which man can be understood is that of the future. It is not enough to long for heaven merely as a coping device designed to take our minds off how much we lament our earthly lot. No, a legitimate otherworldliness must arise not only from an appreciation of the badness of this age (or for that matter, the goodness of the next), but from the fact that eternal blessedness is what we are uniquely designed for. In other words, heaven is meant to be just as attractive a goal for the one who enjoys his present life as it is for the one who wants to escape it. To see ourselves as we are meant to be seen, therefore, we must run on ahead of ourselves, as it were, and then look back.

In the third chapter of The Destiny of the Species I argue that the only clear vantage point from which man can be understood is that of the future. It is not enough to long for heaven merely as a coping device designed to take our minds off how much we lament our earthly lot. No, a legitimate otherworldliness must arise not only from an appreciation of the badness of this age (or for that matter, the goodness of the next), but from the fact that eternal blessedness is what we are uniquely designed for. In other words, heaven is meant to be just as attractive a goal for the one who enjoys his present life as it is for the one who wants to escape it. To see ourselves as we are meant to be seen, therefore, we must run on ahead of ourselves, as it were, and then look back.The way G.K. Chesterton illustrates this point is by considering anew the famous quandary, “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” As anyone who has considered the dilemma knows, if we say that the chicken came first we cannot answer where it came from, and if we say that the egg came first then we are faced with the question of what laid it. Chesterton’s solution is to reword the problem altogether. The bigger issue, he says, is not which came first, but which comes last:

Leaving the complications of the human breakfast-table out of account, in an elemental sense, the egg only exists to produce the chicken. But the chicken does not exist only in order to produce another egg. He may also exist to amuse himself, to praise God, and even to suggest ideas to a French dramatist. Being a conscious life, he is, or may be, valuable in himself.In other words, regardless of what may come at the beginning of the pattern, it is certain what comes at the end of it, and that is a chicken. While chickens indeed lay eggs as one of their many functions, eggs only do one thing, and that is produce chickens. “One is a means,” he says, “and the other an end.”

What is Chesterton’s point? Well, when we are seeking to understand the human condition we must first consider what lies at the end of the road rather than merely considering what was there at the beginning of it. “The only way to discuss the social evil is to get at once to the social ideal.... I have called this book What’s Wrong with the World?, and the upshot of the title can be easily and clearly stated. What is wrong is that we do not ask what is right.” As C.S. Lewis used to say, before we can recognize a crooked line as crooked, we must first have some idea of what a straight one would look like.

The point here is simply that we mustn’t lose sight of our divinely-ordained destiny amid the dust and dirt and distraction of this passing age. Yes, the chicken is indeed produced by the egg, and, likewise, we are the product of our ancestry in some respect. But all of that pales in light of the deeper question of what the chicken is for. And likewise with us. Just as the chicken wasn’t made to be a mere egg-layer, so you were not designed to dutifully play the role and follow the script that those in power are so willing to dole out to their subjects. There is one Playwright and Casting Director, who alone reserves the right to tell you who you are and where you fit into the story he is telling. And in this divine tale, saying that “They lived happily ever after” is a horrendous understatement.

Published on August 26, 2012 20:15

August 16, 2012

The Destiny of the Species: The Jagged Little Red Pill

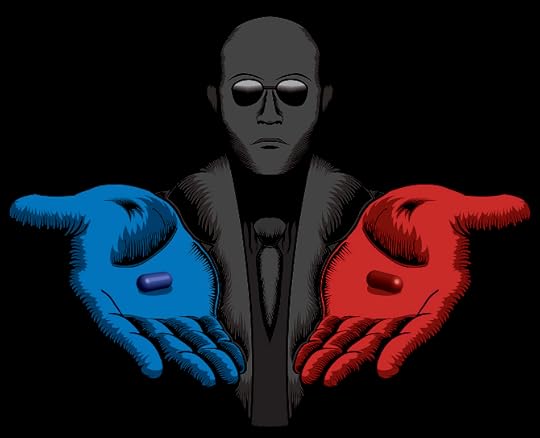

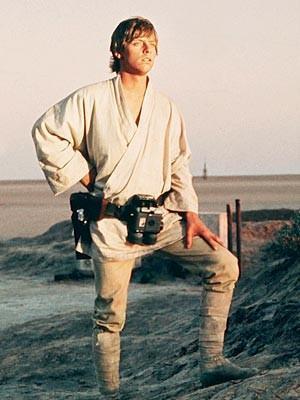

The second chapter of The Destiny of the Species argues that once we understand and accept our future-oriented identity, we must make the conscious decision to take off the blinders and reckon with what this demands of us, namely, a radical posture of questioning the powers that be, rather than simply resigning ourselves to a life defined by the status quo.

The second chapter of The Destiny of the Species argues that once we understand and accept our future-oriented identity, we must make the conscious decision to take off the blinders and reckon with what this demands of us, namely, a radical posture of questioning the powers that be, rather than simply resigning ourselves to a life defined by the status quo.“Propaganda,” writes Thomas Merton:

… makes up our mind for us, but in such a way that it leaves us the sense of pride and satisfaction of men who have made up their own minds. And in the last analysis, propaganda achieves this effect because we want it to. This is one of the few real pleasures left to modern man: this illusion that he is thinking for himself when, in fact, someone else is doing his thinking for him.David Dark (who in addition to being an author teaches high school English) says the following of his students' attitudes toward the loss of control over their own thoughts:

They take personally the apocalyptic significance of films whose protagonists discover themselves in carefully scripted, immersive environments which create the illusion of freedom while using inhabitants to fuel their own death-dealing machinery. They know the joke’s on them when a voice says, “Because we value you, our viewers/customers/clients....” And the bright colors, earnest-sounding voices, and lively music only serve to remind that someone (or something) is trying to create demand and move product…. The sense that they’ve been playing roles in a vast formula of market research, while occasionally consoling themselves with a packaged rebellion, isn’t a realization anyone can sustain for long without becoming depressed. But there is something powerfully invigorating about imagining, especially in the company of young people, what it might mean to take the red pill of reality on a regular basis or to weather the storm to the limits of one’s bubble and to break on through to the other side.It is the ability to see through what’s see-through, to penetrate the façade and steal a glimpse of the worldly wizard behind the curtain, that Dark and others refer to as “apocalyptic living.” As I will argue in subsequent chapters, our native eyes and tainted perspective can only take us so far, and that ultimately God alone can provide for us the lenses through which we can truly behold the depths and degree of our servitude. For our present purposes, though, it’s enough to note that, despite the world’s pomp and promises, the emperor is wearing no clothes. And many of us know it.

The objection has been raised that man’s need to pursue the destiny of the species reflects a kind of wacky mysticism, but this objection falls flat. In fact, I would go so far as to insist upon the very opposite, namely, that until man embraces his identity as one created for everlasting glory, he will never be truly sane. Being willing to take the red pill, jagged though it may be, is precisely what will unlock the door into a strange new world that, though it will never be fully understood, will nonetheless provide the light by which we may understand everything else.

Published on August 16, 2012 21:28

August 5, 2012

The Destiny of the Species: Pushed or Pulled?

As some of you know, I have a manuscript due to Wipf and Stock in a couple months titled The Destiny of the Species, a blurb for which says:

As some of you know, I have a manuscript due to Wipf and Stock in a couple months titled The Destiny of the Species, a blurb for which says:Intended as a counter-point to Darwin’s famous work (which just celebrated its 150-year anniversary), The Destiny of the Species is a simple, provocative, and easy-to-read treatment of the fact that all people—whether they are believers or not—are uniquely hardwired for heaven. What distinguishes us from the animals is our being pulled rather than pushed, drawn by our future rather than driven by our past. Part and parcel of our being made in God’s image is our inevitable frustration with things as they are. It is Christianity alone that can make sense out of man’s homesickness for a place he has never been.In a nutshell, the book is intended to unpack (for both believers and non-believers) the biblical idea that God has placed eternity in the hearts of his creatures, as well as a corresponding frustration with all things earthly when treated as ends in themselves. I still have a few chapters left to complete, but I would like to "leak" a bit of what I have written from each chapter over the course of a handful of posts.

In Chapter 1 I argue that man's bearing the imago Dei means that he has a destiny greater than that of the animals to which he is pulled, rather than pushed. It's our future that makes us what we are in the present, and not our past. This is intended as a challenge to Darwin's theory:

Despite the occasional bit of comfort Darwin's theory of origins may offer, and despite the hook off of which it seems to let us, we humans just can’t seem to escape the nagging feeling that life, at the end of the day, is not completely pointless. Sure, we can fool ourselves with clichés such as “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die,” but the thought of death inevitably causes one to question the morality of his merriment. In a word, beneath the surface we all know that “You only live once” is bad news rather than good, and that what happens in Vegas doesn’t stay there.To bolster the idea that our destiny shapes us more than does our origin, I cite David Brooks's idea that man has always lived in the future tense:

People have a different sense of place. They don’t perceive where they live as a destination, merely as a dot on the flowing plane of multidirectional movement.I think Wendell Berry says it better:

As a people, wherever we have been, we have never really intended to be. The continent is said to have been discovered by an Italian who was on his way to India....For this reason, it seems to me that the all-too-popular approach of preparing people for the gospel by trying to convince them of how unhappy they are is not only completely wrongheaded, but will inevitably create a bunch of Christian consumers who fashion a god after their own image.

Once the unknown geography was mapped, the industrial marketplace became the new frontier, and we continued, with largely the same motives and with increasing haste and anxiety, to displace ourselves—no longer with unity of direction, like a migrant flock, but like the refugees from a broken anthill. In our time we have invaded foreign lands and the moon with the high-toned patriotism of the conquistadors, and with the same mixture of fantasy and avarice.

Instead of appealing to people's sense of personal fulfillment, what we ought to be doing is granting them their happiness (when they claim it), but all the while reminding them that this present age is not ultimate, and dying with the most toys doesn't win us anything beyond the divine rebuke of "Thou fool! This night is your soul required of you, then whose will be those things you have accumulated?"

Man is an eschatological creature, is what I'm saying. And the sooner we appreciate the dynamic relationship between the already and the not-yet, the sooner we will transcend our own earthly-mindedness, as well as helping others do so too.

Published on August 05, 2012 19:50

June 8, 2012

Time to Go Dark

Dear CCC readers and lurkers,

Dear CCC readers and lurkers,The firestorm caused by my resignation has become much larger than I anticipated. I was braced for the initial explosion, but I am finding it harder and harder to deal with the blowback in a godly way. Therefore I think it best to just step away from the blog for a while for the sake of my own sanity and sanctification.

The only thing I would want to say, not so much to my detractors as to those who have expressed genuine love and concern for me, is that I still love the Lord Jesus Christ with all my heart and hunger to read and meditate upon his Word to the end of my days. None of the decisions I have recently made stemmed from anything but a desire for the glory of Christ and a respect for the PCA, for the sake of whose purity and peace I stepped down.

You may see me pop up here and there in other forums, and Creed Code Cult may eventually resurface in a new way with new emphases and features. But for now, my family and I just need a little less noise.

Love in Christ,

Jason

Published on June 08, 2012 11:39

June 6, 2012

Evangelium et Ecclesia

Many of you have surely read Carl Tueman's article about my resignation, in which he opined:

Many of you have surely read Carl Tueman's article about my resignation, in which he opined:

Jason Stellman was a man with a high ecclesiology; and high ecclesiology is important.... Having said this, however, there is a breed of Christian out there for whom the doctrine of the church and 2K are all they ever seem to talk about. They are, it appears, the number one priorities for Christians. Such advocates often seem, at least on the surface, to disdain the basic elements of Christian discipleship - fellowship, loving one's neighbor, protecting and honoring the poor and weak - and spend a disproportionate amount of time talking about their pet ecclesiological and 2K projects.He then substantiated his charge by appealing to the Preaching page on Exile Presbyterian Church's website and the fact that the first thing one sees are lectures from a few years ago on Amillennialism and the Two Kingdoms, noting:

We can end up thinking that the doctrine of the church is more important than the gospel or, worse still, that the doctrine of the church is the gospel. The tendency to make our issues - of which ecclesiology and 2K are just two examples -- into the gospel is always a danger.Now, I initially considered issuing a full-blown response to Trueman, but I have decided against it. Trueman doesn't know me, and I highly doubt he has ever listened to a single sermon I have ever preached or consulted a single person in my church before determining that ecclesiology is "all I ever talk about." There have been enough staunch Reformed brothers who have dismissed Trueman's psychoanalysis of me as hasty and uncharitable that I will forego a real response and instead use his article as a springboard to talk about a related topic: the gospel and its relationship to the church.

Much of the pushback I have gotten in the past few days has sprung from the supposed need to subordinate the church to the gospel. But is this really a wise and biblical expectation?

First, consider the implications of the idea that a true church can only be identified by its faithful preaching of the gospel. While this sounds reasonable at first glance, when we think about it more deeply it begins to appear severely individualistic. The reason for this is that such an idea necessarily removes the church from having any role whatsoever in teaching the believer what the gospel actually is, since the believer's proper understanding of the gospel needs to exist already as a litmus test for determining whether a church is true or not. In other words, before a church-search can begin, the individual believer must be soteriologically armed with an already-intact understanding of the gospel, and the role of the church is simply to agree with his prior-held conclusions, thereby proving itself to be true.

And secondly, consider the message of Paul in the book of Ephesians, particularly chapter 3 (which I touched upon here). The "mystery" which the apostle was ordained to proclaim, which he calls in 6:18 "the mystery of the gospel," is that "the Gentiles might be fellow-heirs and members with the Jews of the same body" whose mystical Head is Christ (v. 6). In other words, there is a sense in which, when we step outside of the solely individual applications of the gospel and see it from Paul's cosmic perspective, the gospel is the church, and the church is the gospel.

Therefore the charge that I am in danger of subordinating the gospel to the church trades upon a false dilemma. The creation of a mystical Body comprised of all tribes, peoples, and nations is itself central to the gospel message and called by Paul "the mystery of Christ" and "mystery of the gospel." So in a sense Trueman has a point when he charges me with closely identifying ecclesiology with soteriology, but it has nothing to do with personal hobby-horses, and everything to do with Pauline theology. And since the apostle refuses to divorce gospel and church, so should we.

After all, we're not evangelicals.

Published on June 06, 2012 23:00

Jason J. Stellman's Blog

- Jason J. Stellman's profile

- 5 followers

Jason J. Stellman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.