Richard Denning's Blog

July 6, 2019

The Franks Casket

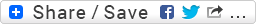

The Franks or Auzon Casket is an 8th century Anglo-saxon casket of probably Northmbrian origin. Its is a whalebone casket completely decorated on its 4 sides and the lid with runic inscriptions as well as images which portray both Christian and Pagan stories. The casket is about 23cmx 19cm x 11cm ins size. Its age has been deduced from the language used on the script that accompanies the illustrations. These are Latin as well as old English and the Futhorc runic script.

The panels that make up the casket were donated by a Sir Augusts Wollaston Franks to the British Museum in 1867. He was an antiquarian and a collector and considered one of the great Victorian collectors whose finds benefited the British Museum. Franks himself found the panels in an antique shop in Paris in 1857.

We know virtually nothing about the origins of the casket. It is believed to have probably been made in a monastery in Northumbria in the 8th century. What then happened to it is a mystery but it probably belonged to a church at some point before being looted in the French Revolution. It eventually turns up in the possession of a family in Auzon in the upper Loire which is why it is sometimes called the Auzon casket. It is thought it had been used as a sewing basket for some time. The casket was originally held together by hinges of silver which have been lost or sold as have the lock and some of the lid panels which may also have been silver. Without these the box was just loose panels. These turned up (minus one side panel) in an antique shop in Paris which is where Franks found them.

The missing panel was found in 1890 by the Auzon family who then sold it to a museum in Florence.

Thus the casket on display in the British Library consists of the 3 of the original panels, what is left of the lid and a cast of the missing panel.

Front panel of the casket

The front panel of the Franks casket shows two legends. On the left is the pagan Germanic myth of Wayland the Smith. Elements that can be made out include Wayland aparently crippled by his captor king Niohad working in the forge. At his feet is the body of the king’s son who Wayland kills. On the right Wayland captures birds whose feathers he uses to escape.

On the right is the Christian story of the Adoration of the Magi. Three kings/wisemen can be seen bearing gifts approaching the stable wherein a manger can be recognised and overhead a star is visible

The writing around the edge is a riddle about whale bone from which the casket is made.

The flood cast up the fish on the mountain-cliff

The terror-king became sad where he swam on the shingle.

Whale’s bone.

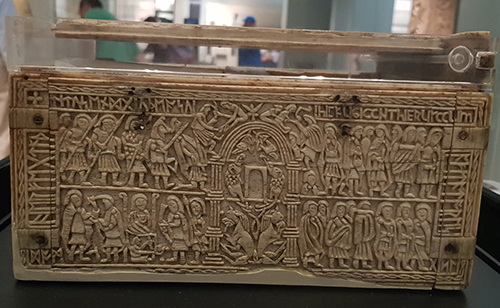

The rear panel.

The rear panel of the Franks casket shows the capure of Jerusalem by the Romans under Titus in AD 70. This event occured as part of the Roman-Jewish wars that followed an uprising by the Jews against Roman rule and eventually ends with destruction of their Temple. Why the panel shows this scene is unknown.

Left side panel.

The left side panel of the casket portrays the legend of Romulus and Remus and the she wolf. In the centre we can see the two boys being suckled by the she-wolf. She also is seen at the top protecting them from a hunting party. The text translates as:

Romulus and Remus, two brothers, a she-wolf nourished them in Rome, far from their native land.

Romulus and Remus go on to found Rome. There are paralells with Hengist and Horsa who found the first Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Kent. Thus it is thought by some that this scene is saying something about the destiny of the Anglo-Saxon invaders ruling Britain.

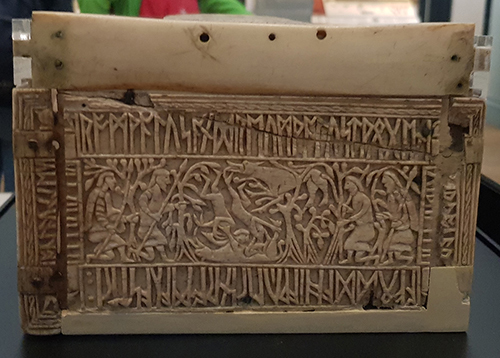

Right side panel

The right side panel of the Franks casket is the most confusing. At the far left a animal figure sits on a small hill or mound, and is approached by a warrior. In the centre is a horse and another figures. Finally on the right are three figures. Two of them seem to be holding the third captive. The text has never been entirely understood. It has elements that say something like:

Here sits Hos on/in the hill/barrow. She suffers distress as ??Ertae had imposed it upon her. A wretched den of sorrows and torments… wood/rushes.

Theories abound about this image. One idea is that this might be be a reference to the death of Horsa (often associated with the horse image), the brother of Hengist. He died in battle with the British. Is the text a reference to his mother mourning him? Is that warrior we can see his brother visiting his grave?

Other ideas are that ii is a now lost Pagan tale, others that it refers to Satan and hell.

We probably will never know.

The lid

Most of the lid of the Franks casket is missing. It is believed that panels of perhaps silver laid here above and below the remains. What is left is thought to show another Pagan legend. Again there are arguments as to what is protrayed. The only word visible is Egil. So many believe that this time it shows an archer, Aegil brother of Wayland the Smith defending a fortress from an attacking horde of giants (shown on the left). Other ideas is that Egil refers to Achilles in which case is this the scene where Achilles is shot by an arrow in his heel? If so this could be the fall of Troy which fits in which the panel showing Romulus and Remus who, exiled from Troy, go onto found Rome.

The Franks casket is a remarkable object. We may never know its full story – niether what happened to it in those missing centuries or exactly what it all means but if you are ever in the British Museum be sure to visit the Anglo-Saxon room as it and many other wonders are on display there.

News about my books

I am currently working on the 5th Northern Crown book which continues the story of Cerdic and his brother Hussa whose rivalry mirrors that between the Kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira over the destiny of one of the greatest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms: Northumbria. It was that land at the height of its power in the 7th to 8th Century that led to a treasures like the Franks Chest and was home to Bede and the site of the important Synod of Whitby. But the Northern Crown series tells the story not of those glory days but of that earlier struggle that created that kingdom. Explore the darkest years of the dark ages with Cerdic and Hussa. My next book will be out spring 2020.

[image error]

June 17, 2019

Writing – Making your Mark

Today I visited the British Library and before going to the reading room to work on my next Northern Crown Novel I stuck my head into the special exhibitions room. Last time I was here it was full of Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts such as Beowulf and early law codes and maps. This has now been replaced by two exhibits. There is one on Leonardo’s notebooks I may return to but the one that caught my eye, me being in a literary mood, was entitled ‘Writing – Making your Mark’ which is an exhibition all about the written form.

This exhibition is split into 5 sections.

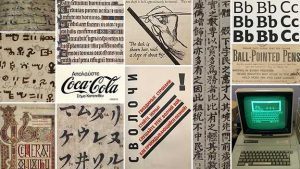

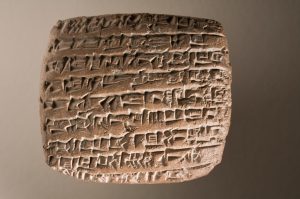

The Origins of Writing charts the development of letters and writing from the earliest scripts. Exhibits shown include Sumerian Cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphics (both 3rd millennia b.c.) and Shang Dynasty Chinese characters engraved on oracle bones. I particularly found it fascinating how letters evolved from shapes. So the Latin letter A was originally a stylised ox head (look at an ‘A’ and turn it upside down and you will see).

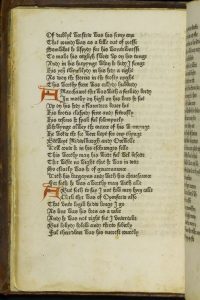

Writing Systems and Styles looks at how letters were put together in various ways to create writing systems. This includes oriental and Arabic scripts and the evolution of the Latin script and how it is represented through the centuries from its earliest origins as an off shoot of Egyptian hieroglyphics, through the development of Roman letters and on through medieval Gothic Script and monastic traditions.

Materials and Technology examines the tools used to create writing from clay and wax tablets, through to paper, styluses and pens including goose feather nibs, biros and fountain pens. There is also a look at printing technology and some examples of early printed books such as Canterbury Tales.

People and Writing covers the craft of writing, engraving, pen-man ship and even such skills as shorthand. This section featured examples of instruction manuals and books and how to guides for typists etc.

The Future of Writing discusses how technology has already and may effect writing in the future. Will emoji’s and audio/ video messages replace the written form. Will be still be writing anything decades from now? Or will the form just change?

An interesting exhibition. It is not a large exhibition – maybe 150 or so exhibits but some you can study for quite a while. If you like the appearance of ancient manuscripts and enjoy exploring the evolution of one of the key elements of what make us human, it is a pleasant way to spend an hour or so.

The exhibition runs until 27th August 2019. Find out more…

Images from Wikipedia Commons or British Library shared images.

[image error]

September 14, 2018

Xmas Day 1914: where was the Truce?

I was recently in Belgium for a holiday. My son has been studying World War 1 history at school so we decided to visit the locations around Ypres that featured in the war. One site everyone was keen to see was the location of the Xmas day truce of 1914.

What was the truce?

By Christmas 1914, World War 1 was 4 months old. The front in Flanders around Ypres was pretty static with the race for the sea that established the salient at Ypres in the past and the great battle of Passchendaele in the future. That Christmas for the only time in the war a brief truce occured up and down the line. It did not occur everywhere and was definately not official but, in a few locations, tentative ceasefires were agreed formally or informally and soldiers emerged cautiously to search no-mans-land for the dead. In some places exchanges of conversation started up, food was passed around and then alcohol, carols were sung and then …somewhere… maybe in several places… someone got out a football!

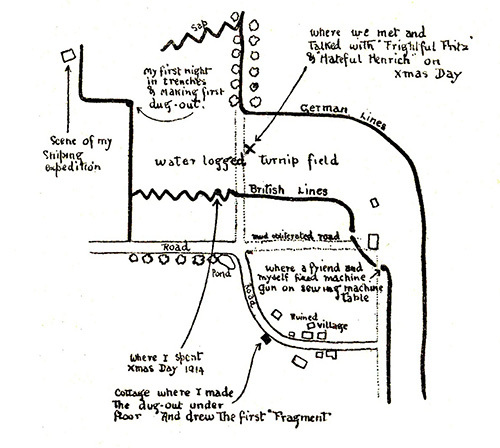

Bruce Bairnsfather’s map showing the turnip field where he met Germans on Christmas Day 1914.

In one location near the vilage of St Yvon a certain (then) Seargent Bruce Bairnsfather of the Warwickshires was posted. He was injured not long after Christmas and took up drawing cartoons which in time became a definitive account of life in the trenches. He also drew a map of the exact location of the truce he was part of and recorded much of what went on.

“Christmas morning I awoke very early, and emerged from my dug-out into the trench. It was a perfect day. A beautiful, cloudless blue sky. The ground hard and white, fading off towards the wood in a thin low-lying mist. It was such a day as is invariably depicted by artists on Christmas cards—the ideal Christmas Day of fiction.

“Fancy all this hate, war, and discomfort on a day like this!” I thought to myself. The whole spirit of Christmas seemed to be there, so much so that I remember thinking, “This indescribable something in the air, this Peace and Goodwill feeling, surely will have some effect on the situation here to-day!” And I wasn’t far wrong; it did around us, anyway, and I have always been so glad to think of my luck in, firstly, being actually in the trenches on Christmas Day, and, secondly, being on the spot where quite a unique little episode took place

“Everything looked merry and bright that morning—the discomforts seemed to be less, somehow; they seemed to have epitomized themselves in intense, frosty cold. It was just the sort of day for Peace to be declared. It would have made such a good finale…”

“Walking about the trench a little later, … we suddenly became aware of the fact that we were seeing a lot of evidences of Germans. Heads were bobbing about and showing over their parapet in a most reckless way, and, as we looked, this phenomenon became more and more pronounced.

“A complete Boche figure suddenly appeared on the parapet, and looked about itself. This complaint became infectious. It didn’t take “Our Bert” long to be up on the skyline (it is one long grind to ever keep him off it). This was the signal for more Boche anatomy to be disclosed, and this was replied to by all our Alf’s and Bill’s, until, in less time than it takes to tell, half a dozen or so of each of the belligerents were outside their trenches and were advancing towards each other in no-man’s land.”

“A strange sight, truly!”

“I clambered up and over our parapet, and moved out across the field to look. Clad in a muddy suit of khaki and wearing a sheepskin coat and Balaclava helmet, I joined the throng about half-way across to the German trenches.“

An incident from the truce recorded by the cartoonist.

The turnip field where he met Germans on Christmas Day 1914.

Bairnfather’s map is so accurate and detailed that it is easy with a good map to locate the spot where this all happened. Indeed today (unlike 10 years ago when I visited before) the spot is marked on google maps.

This is the cottage built on the site of the original building where Bainfather lived.

The same road exists as did in 1914 with a bend in it and on the bend is a cottage located exactly where the one where Bairnfather lived.

The pond on the map still exists.

The map recorded a pond and that is still there.

The UEFA monument to the Christmas Day football of 1914 at St Yvon. There is much debate as to actually where the football occured with various locations mentioned by various soldiers. On his original map of the truce location, Bairnsfather did not mention football but later in interviews just before he died said they did occur here. His maps give us a firm location of the truce so UEFA decided it was a fair choice for their memorial to the football that occured this day somewhere in the area.

I recreate the incident with the help of my father.

Near to the location of the truce is the town of Mesen that was occupied by the Germans for much of the period. Another memorial to the incident is located in the square there. As we left the area we stopped briedly there and somehow this photo happened!

[image error]

June 25, 2018

Where’s the Hill? The Mystery of Abingdon

Abingdon is a small town in rural Oxfordshire that is tucked into the confluence of the River Thames and the River Ock. It is a pretty town of medieval Abbey ruins, half timbered houses and a stone bridge and has a strong claim to be oldest continually inhabited settlement in England with archaeological evidence of an ongoing population here from the Iron Age onwards. Unlike other places which have periods of abandonment, here one period of history seems to blend into the next – Iron Age to Roman, Roman to Saxon and on into Medieval period.

Yet in the name of the place there is a bit of a mystery. The name is of Old English in origin and seems to mean ‘Hill of a man named Æbba”

This then generates two questions. Who was Aebba and where is the hill?

You see, Abingdon stands in a valley. It is right next to the River Thames and certainly not on a hill.

So how did the town come by its name? To try and answer this we have to delve into legends, myths and what exist of records relating to the founding of an Abbey in this town as well as to the earliest years of Anglo-Saxon Britain.

Amongst the early manuscripts and charters recorded by the monks of Abingdon several survive in the volumes of the Cotton Manuscripts now in the British Library. Cotton was a 16th to 17th century collector whose Library preserved many of the early documents that are critical evidence in piecing together these earlier years. Many of the Cotton Manuscripts were named after Emperors. One of the manuscripts named after Claudius -Claudius C tells us about the founding of an Abbey at Abingdon in the 7th century.

The Abbey was founded by a certain Hean under the supervision of a sub king of Wessex called Cissa who was uncle to Hean. The Abbey was founded circa 680 A.D. The Abbey was later sacked by the Vikings but then in 954 King Eadred appointed Æthelwold, as abbot. He was a very significant figures in the English Benedictine Reform, and so under his leadership Abingdon became one of the most important Abbeys in England. Here it was that the Chronicle of the Monastery of Abingdon was written in the 12th century. Most of what we know including the Cotton manuscripts comes originally from that chronicle.

The chronicles record the history of the Abbey very well from the 10th century but the original founding of the abbey and how the town got its name requires us to dig a bit deeper.

The Treachery of the Long knives

There is a tale recorded in 9th century Historia Brittonum attributed to the Welsh historian Nennius and later elaborated upon by Geoffrey of Monnouth in his 12th century Historia regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain). The historical reliability of these accounts is debatable – particularly in the case of Monmouth’s work which is basically historical fiction. Never -the-less given the paucity of documentation these are all we have to go on for some of the event. The sections relevant to Abingdon relate to the so called ‘Treachery of the long Knives’ or the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ which was an occasion when Hengist and the first Saxon lords to come to Britain were invited to dine with Vortigern, High King of Britain. The Saxons were invited in peace but each took a knife hidden upon them. When the British were drunk, Hengist called on his men to pull out their blades and the result was the massacre of the nobles and leaders of the British. Vortigern was spared both as he was married to Hengist’s daughter and probably in order to be ransomed.

The traditions of the founding of the Abbey of Abingdon, mostly recorded in the medieval period contain a story that a young man survived the massacre and fled north from the scene of the atrocity (Stonehenge) and up the Thames valley. There he retreated to a hill which became a holy site and according to the legend the beginnings of a monastery. The man’s name was Aebba and so it was that the hill upon which he created the hermitage became the ‘Hill of a man named Æbba”

Another account in another manuscript about the founding of Abingdon Abbey talks about a monastery being founded by an Irish monk called Aben who came to the area “before the Saxons came to Britain”.

Whether our man is a British nobleman or an Irish Monk we have a man called Aebba or Aben coming to the area and setting up a retreat or monastery around the time the first Saxons are coming to Britain – so some time in the 5th century.

What about the Hill?

So if we have the origins of the Aebba or Aben in Abingdon, what then of the hill? Where did that come from? Abingdon lies on a flat valley bottom along the Thames with no obvious hill close at hand.

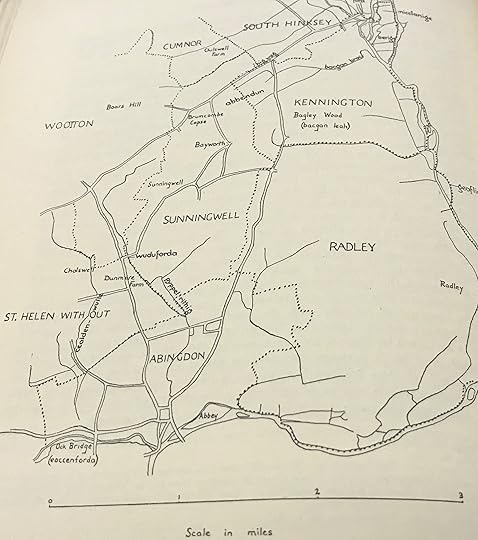

In the Cotton Manuscripts (Claudius C) there is talk of land being granted to the monastery officially in the form of a deed. The deed contains the bounds of the land in the form often used in these documents – it literally describes a particular stream, a hollow, a road and a place where two parish boundaries meet at a hill. That hill is called Abbendun. Historians have examined this description and located the spot described. The map below is a suggested location in Biddle, M, Lambrick, G, and Myres, J N L, 1968 The Early History of Abingdon,

Berkshire, and its Abbey, Medieval Archaeology XII, 26-6.

It is now believed that a hill once called Abbendum can be identified as Boars Hill some miles north and west of Abingdon. I visited the hill recently. Apparently in the last century or so the formerly bare hill side which afforded great sweeping views across the countryside has become a popular location for building on and along with the buildings have come trees. Thus it is difficult to both see the hill and get an idea what it would have one looked like.

We did locate a mound built on Boars Hill to allow views across the area but alas the view is blocked by trees! It is still pleasant area for a walk on a walk summer’s day however.

So what happened?

If a man called Aebba came to a hill now called Boar’s Hill in what is now Oxfordshire and made a monastery there and left his name as the name of the hill – Abbendun, how did that become the name of a town a few miles away? This raises another question. What in fact was the settlement called originally?

There is a manuscript (MSS 933) at Trinity College Cambridge which contains entries about the year 688 which refer to the foundation of the Abbey at Abingdon.

This talks about Hean under Cissa’s command bringing the abbey of Abbendun down from a hill to a village called Souekesham.

Can we be sure that Abingdon was once called Souekesham? Souekesham would mean the dwelling of a person called Soueke. There is another other place name in the area with a similar origin – the modern day Seacourt (Old English Seuecurda) – so maybe evidence of a couple of locations named after the same figure. Maybe Soueke was a 5th century Saxon who settled in the area. We know from the archaeology of the Saxton Road side at Abingdon that this place was settled by Saxons as early as the mid 5th century. the Thames river provided an easy route for Saxons to migrate into the heart of Britain and many Thames valley locations show early evidence of this settlement.

The evidence of St Helens.

Cotton Claudius C and Cotton Vitellius A tell of the founding of not just a single monastery but a joint monastery and nunnery. Hean was to found the monastery and his sister – a certain Cilla a nunnery. The name for the site of the nunnery was Helenstowe. Cilla is recorded as having made a small black cross of iron made (from one of the nails from the true cross) and was to be buried with it. Aethelwold’s monks digging in the area of what today is called St Helen’s church in Abingdon were supposed to have found the cross so it seems that Cilla built here nunnery on eth spot of what today is the church of St Helen’s and Hean his monastery or Abbey were the medieval Abbey would later stand.

Putting it all together

So the story might go like this – a man called Aebba fleeing from the masacare of the long knives, or alternatively an Irish monk called Aben come to a remote hill in Oxfordshire in the 5th century and found a retreat or monastery. In time it is named after him. Thus Abbendum is named.

Two centuries later a brother and sister are given instructions to found a joint monastery and a nunnery in the area. There is already perhaps a religious community at Abbendum of sufficient significance for Hean to want to use the name. Yet the location is not ideal. A small river side village nearby called Souekesham is far better suited. There is a river for a mill and fish aplenty. There is space for both his sister’s nunnery and his monastery there.

So the existing name was taken and in time Souekesham as a name passed into legend and was forgotten – preserved only in an ancient manuscript in the early records of the Abbey.

Souekesham took the name Abbendum which in that form or as Abingdon is now the name it has been known as for over 13 centuries.

I find these origin stories of places fascinating. Often we walk about seeing names of places and are unaware what the story is behind them. What’s in a name? Often quite a lot.

[image error]

January 21, 2018

Glendalough: The valley of two lakes

In the summer of 2017 we spent our holidays in Ireland and staying near Dublin. One day we headed up into the Wicklow hills and visited Glendalough. The name Glendalough comes from the Irish Gleann Dá Loch which means “Valley of two lakes.” It is a “does what it says on the tin” type of name as it is a glacial valley with an upper and lower lake. It is area of great natural beauty and at least before the pilgrims and later the tourists came would have been a very peaceful spot. Small wonder then that it is the site of an Early Medieval monastic settlement which was founded in the 6th century by St Kevin.

The life of St Kevin is not well documented and in fact no records survive from his life time or even close to it. So as with many cases in this period we have to turn to the often unreliable saint’s life accounts. In the case of St Kevin there is a late medieval Latin Vita found in the records of the Franciscan Convent in Dublin. According to this account, Kevin’s name was Coemgen (anglicized to Kevin. He was of noble birth. He was the son of Coemlog of Leinster and was born (according to the tales) in 498 at the Fort of the White Fountain. The account also goes on to relate miracles and other events. One example was the legend that a white cow visited every morning and evening and supplied the milk for the baby.

The upper lake at Glendalough and the site of St Kevin’s bed.

In time Kevin was ordained and according to the Vita was led by an angel to the remote location of the upper lake at Glendalough where he lived as a hermit in a cave (the cave is actually a former Bronze Age tomb which after Kevin’s time was known as St. Kevin’s Bed). Here, so the tales go, Kevin’s companions were the animals and birds. For seven years he live alone, sleeping on stones, wearing skins and eating little and praying.

In time he began to attract followers who built the first monastery on the shores of the upper lake. Having established a thriving community, Kevin retired into solitude again in 544 but was persuaded to rejoin his followers by 550. The tales then say he presided over the monastery until his death in 618 at the extreme age of 120! Today Kevin is one of the patron saints of the diocese of Dublin.

The monastery as seen from the visitor centre.

In the centuries after Kevin’s death, Glendalough became one of the main pilgrimage attractions of medieval Ireland. It was said that to be buried in Glendalough was as good as being buried in Rome. It was also the case that several trips there equated to the much longer pilgrimage to Rome. Thus many Kings and Queens and bishops were buried here.

The golden age at Glendalough was between 1000 and 1150AD during the reigns of the Irish kings Muirchertach Ua Briain (of Munster), Diarmait mac Murchada (of Leinster) and Toirdelbach Ua Conchobair (of Connacht). The most famous abbot of Glendalough Lorcán Ua Tuathail (Laurence O’Toole) went on to be the first archbishop of Dublin. He died in 1180. These kings and bishops and others were involved in constructing the stone buildings that survive to the present day and which are there for the visitor to enjoy. The site of the medieval period monastery was near the lower lake.

Today there is a visitor’s centre at the site which includes a small museum and videos of the history of the monastery. From the visitors centre it is a 5 minute walk over fairly easy ground to the site.

We were lucky that after a day or two of rain the sun came out for our visit. Here you can see me posing with St Kevin’s chapel in the background.

Inside the cathedral looking west.

The largest building at Glendalough is the cathedral. The earliest parts of this actually come from an earlier church – the stones being reused in the west doorway seen above.

Inside the cathedral looking east

The chancel and sacristy are later and date from the late 12th and early 13th centuries. The chancel arch can be seen above with the east window beyond.

There are other smaller churches on the site including St Kevin’s chapel (above). The church also has a belfry with a conical cap and four small windows at the west end of the roof that looks rather like a miniature round tower.

Apart from the churches and cathedral, the site has evidence of a number of buildings including a reconstructed ‘Priests’ House.’ It is not known what the original purpose of the building was – possibly housing relics. It gets its modern name from the practice of interring priests there in the 18th and 19th centuries.

To me the jewel in the crown was the round tower at Glendalough. It is considered to be one of the most finely constructed and beautiful towers in Ireland. The tower is over 30m high (just under 100 feet). The body of the tower is original although the roof was rebuilt in 1876 using original stones. The tower has 6 timber floors, connected by ladders. The four storeys above the entrance feature a small window with the top having four windows. The door is about 3.5 meters or 10 feet from the ground. It is clearly designed for defence. Refuge seekers could retire inside then raise the ladder making it very hard to attack. The tower was built in the years after centuries of Viking raids so this was an sensible decision and wise precaution.

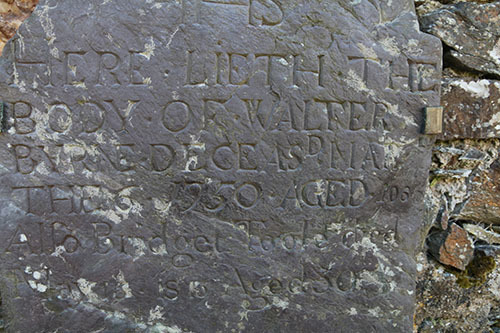

The site is now dotted with gravestones of varying age – many (as above) in a state of disrepair. One caught my eye. You may recall that St Kevin was supposed to have lived until the age of 120. That might seem far fetched and yet I found this below engraving recording the death in 1950 of a Walter Byrne aged 106! Maybe there is something in the air or water here.

Glendalough was for centuries a centre of learning. The monks and scholars produced many manuscripts in Irish and Latin, including astronomical and mathematical texts and chronicles. One of the most famous manuscripts is the 12th century book of Glendalough which is now preserved in the Bodleian library in Oxford.

In 1214, the dioceses of Glendalough and Dublin were united which led to a decline in the cultural and ecclesiastical status of Glendalough. Finally in 1398 the valley was attacked by English forces and settlement destroyed which left the site a ruin although still seen as a place of pilgrimage.

For more details on the Glendalough Visitor Centre click here.

[image error]

November 26, 2017

Place of the Caves – beneath the City of Nottingham

Many people are unaware that beneath the modern city of Nottingham are hundreds of caves, carved into the soft sandstone upon which the city stands. Yet it is the case that the city has a complex of over 500 caves. Many of these date back as far as the Dark Ages. More recent ones were used for industrial purposes and even as bomb shelters in the 1940s. It is claimed that Nottingham has more man-made caves than anywhere in the UK and nowadays the cave network has Ancient Monument Protection status.

My wife and I in the caves

So significant a feature were the caves that one of the earliest descriptions of the city in The Life Of King Alfred, by Welsh monk and historian, Asser, following a visit by him in about the year 900 calls the areas Tiggua Cobaucc which meant ‘Place of Caves’. These ancient caves were eventually used by the poor for housing for centuries and certainly throughout the entire medieval period. Eventually this practice came to and end around 1845, when the St. Mary’s Enclosure Act made the rental of cellars and caves as homes illegal.

Heading down into the caves you find areas where brickwork is replaced with the sandstone.

In the caves you can find man made features such as a well leading down from higher up, through the caves and down further.

A well.

And Cess pits carved out of the bedrock.

Cess Pit

Other caves contain underground tanneries where hides would be treated in beds filled with urine.

Tannery

Here is a cave used as a tavern cellar. The ledges would be where the beer would be stored – off the ground.

Tavern Cellar

Some of the cellars were later used to house machinery during the industrial revolution. The Luddites objected to the machines which they saw a threat to the traditional labour force and so they sabotaged the machines. Often the machinery was in the caves and so they would sneak in and do their damage. Someone kept watch above ground and if the authorities turned up they would drop coins through small holes to warn those below to flee. It is possibly a source of the phrase “the penny has dropped”.

In the Second World War Nottingham was raided by the Luftwaffe and the city used the caves as shelters.

Today you can visit the caves either on tour or self guided. Find out more…

[image error]

September 20, 2017

To chance your arm – the door of reconciliation

This summer I visited Dublin Cathedral and as we were walking around I came across a door standing in the middle of the floor. It is a very old wooden door with a curious hole in the middle. Drawing closer we realized it was not only a door of significance but in fact is the door behind the phrase “to chance your arm.”

It seems that in the year 1492 the Butlers of Ormonde and the FitzGeralds of Kildare were rivals families locked in a longstanding dispute over who should be the Lord Deputy. No resolution was reached and in that year the dispute became violent and a small battle occurred outside Dublin city walls.

The fight did not go well for the Butlers and so, realizing fortune had turned against them, they fled to St Patrick’s Cathedral where they took refuge. Their enemies pursued them to the cathedral and asked them to open the door and come out and agree to a peace.

The Butlers did not believe that they could trust the Fitzgeralds and so refused to open the door as they feared they would be killed.

So it was that Gerald FitzGerald asked for an axeman to chop a hole in the door. When this was done he pushed his hand through the door as a gesture of peace. The head of the Butler family took this as a sign of good faith and shook hands with Gerald. The fighting was over and peace restored.

Here I am chancing my arm but Jane, my wife, did not have any weapons!

The door is known today as the “Door of Reconciliation”. It is believed then that this story was the origin of a commonly used Irish phrase “To chance your arm” or to take a risk.

[image error]

September 3, 2017

The Galloway Hoard – the Viking treasure trove

In August 2017 I visited Edinburgh and saw that there was an exhibition of the Galloway Hoard in the Museum of Scotland and decided to visit.

The Galloway Hoard is considered to be the richest hoard of unusual and rare Viking objects ever recovered in the British Isles.

In the 10th century an unknown individual buried a treasure trove in what today is Dumfries and Galloway. There it lay for over a thousand years until a party of metal detectorists located it about 3 years ago in 2014 on land that belongs today to the Church of Scotland. The group called in the county archaeologists who started up a dig on the land, which revealed a number of artefacts. One of the early objectives located was a silver christian cross.

Further investigation was undertaken – including digging a trench. Concern over possible vandalism or theft led to the local farmer stationing a large bull in the field as a body guard at night! The efforts were not in vain as this activity led to the discovery of an even deeper stash of treasure – meaning that the treasure has been buried into two layers or maybe at two different times.

In addition evidence was unveiled about the presence of a building. Perhaps the horde had been buried inside, or near to or under a monastic building.

In the past large finds such as the Staffordshire Hoard have amazed archaeologists and the wider world. The Galloway Hoard has a special significance because many of the objects show connections between peoples right across Europe. In addition normally perishable objectives like leather, wood and textile has survived allowing their study

This discovery comprises more than 100 objects. One of the finest pieces is a unique gold bird-shaped pin.

There are also Anglo-Saxon disc brooches of a kind not found in Scotland before:

The presence of these articles raise questions. Could these represent Viking booty from raids in England or maybe there were gifts or simply traded? We do not know.

Other brooches of interest are two examples of a quatrefoil brooch: an usual design.

Several of the objects have clear signs of Viking runes (the script that the Viking Norse and Danes used..

There are also gold arm rings. Warlords and Vikings of rank rewarded loyalty by handing out precious arm rings to followers.

The exhibit includes a short video and explanatory panels.

There is currently an appeal to raise just under £2 million in order that the horde can be preserved and studied further and its secrets discovered.

[image error]

August 2, 2017

A visit to Bletchley Park

In July I paid a visit to the Bletchley Park Museum.

During the war this housed the code breakers of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) which after the war became GCHQ.

This was the place where the boffins who cracked the Enigma and Lorenz codes and other codes and cyphers worked in conditions of great secrecy. It also was home to scores of mainly female workers who ran the bombes that analysed the settings of Enigma, as well as translators who would convert the German messages (and other languages) into English, intelligence officers who would interpret the reports and many other specialists. Their story was not told until decades after the war. Yet their work may have been the single most important action in the war – saving countless lives and shortening the war by perhaps 2 years. It was here that the location of German U-boats were determined – helping win the Battle of the Atlantic. They were able to find out the targets of bombing raids, the locations of enemy units and even the progress of the V weapons projects. Their contribution to the planning of the land campaigns in Africa, Italy and Normandy was pivotal. This museum is a superb place to find out all about that.

Several of the Huts are available to visit. Many have the offices setup as they were during the war.

The museum occupies the very huts and Mansion the code breakers worked in. The different huts had different functions. So those working in Hut 8 (like Alan Turing) invented methods and machines to be used to analyse the settings of the code machines, Hut 11 housed the bombes that they designed, Hut 6 actually deciphered the Enigma code and Hut 3 would then take the messages which were in German and translate them into English. (The messages being pushed between the two huts, along a wooden shut by a broom handle – such are the small details of such significant activities). Hut 4 housed analysts who worked out what the messages meant and their significance.

The Mansion was the original house of the estate and the first part of the base to become operational when the government took it over.

The lake and gardens of Bletchley Park became important as the code breakers would take breaks in the grounds and in the winter skate on the frozen lake. Unable to discuss their work the workers filled their free time with pursuits like concerts, dances, chess competitions, rugby games and dozens of other activities – many of the programmes and records of which still exist in an exhibit on life at the park..

The lake which would freeze over in the winter.

There were many codes and cyphers in use but two machines in particular became the focus of much of the activity at Bletchley Park.

Enimga

Enigma was used to send generally shorter messages like weather reports and orders to U-boats. An operator could type in a message, then scramble it by using three to five notched rotors, which displayed different letters of the alphabet. This would then be transmitted over wireless by simple morse code to a receiving station. The receiver needed to know the exact settings of these rotors in order to unscramble the text. Otherwise it was just a string of meaningless letters.

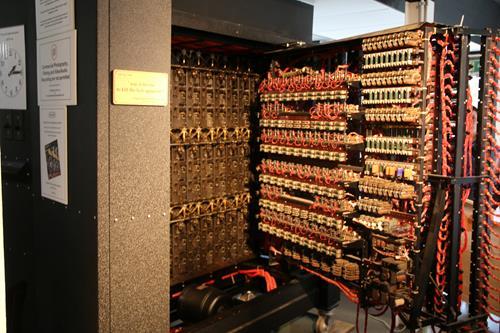

These settings changed each day and with several wheels, in various orders with multiple ways of configuring each cog there were believed to be hundreds of trillions of combinations. Over the years the basic machine became more complicated as German code experts added plugs with electronic circuits. Breaking this code needed machines and humans to work together. The machines- called bombes could analyse possible settings and see if they were the right ones. Yet humans had to devise a short list of possible settings to test and that is where the genius of the code breakers came in. They would make a guess as what part of the message might be (Maybe “weather report Atlantic” )and then suggest settings that would work with that message.

One of the bombes that could test Enigma settings. This one is an working replica at the museum. All the originals were destroyed.

Lorenz was even more complicated than Enigma and was used for longer messages. It was sent by teleprinter and generated electronically. The Lorezne machines changed the text so anyone intercepting it would not understand it.

Analyzing the Lorenz machine settings required machines even more advanced than the bombes that cracked Enigma. The earliest computers, called Colossus were actually developed to work out the Lorenz setting once a break through by an accademic called Bill Tutte was made. He worked out that the pattern used to scramble the text was actually a repeating cycle. There is a replica of Colossus in the adjacent National Museum of Computing which is work seeing to get the full picture. It is fascinating to consider how much he efforts in Bletchley kickstarted the whole computer revolution.

Colossus

One of the great code breakers was of course Alan Turing who was massively involved in cracking enigma. There is a fantastic statue of him at the museum

You can also visit his office. Its amazing to be able to stand in the very place that Enigma was cracked. As with most of the offices it is pretty plain and simple. Many of the offices are created like this – often with videos of actors playing the roles of the code breakers and snippets of conversations can be heard in he rooms.

Alan Turing’s office

The National Museum of Computing on the same site (not open every day) has working originals or replicas of the early computers (including Colossus) and the chance to try out the earliest computer games and do some coding if you can remember how to do it or ever could! If you are looking to visit allow a full day for both sites.

Find out more about Bletchley Park here.

With the family outside the mansion.

[image error]

July 11, 2017

Visit to Birsay – one time capital of the Orkneys

In the summer of 2016 I visited the Orkney Islands off the coast of Scotland. It is an archipelago teeming with historical sites of great significance. The summer in Orkney is not very long and many locations are not easy to get to apart from a few weeks in the year. Indeed one site that is quite restricted is the island called the Brough of Birsay which you can only visit between mid-June and the end of September.

This windswept island was however once a focal point in the islands. It features remains of both Pictish and Viking settlements and was perhaps even the capital of the Viking Earls such as Thorfinn ‘the Mighty’, Earl of Orkney. The words ‘brough’ and ‘birsay’ are very descriptive as they seem to derive from the Old Norse borg or ‘fort’. ‘Brough’ implies a naturally defensive island fortress. ‘Birsay’ relates to the fact it is only accessible by a narrow neck of land.

Today the Brough of Birsay is still a tidal island – connected to the mainland via a causeway. It is therefore important to check tide tables when visiting so as to not get cut off. Even during our hour or so on the island we noticed the sea rising quickly. I can also see why the island is only open at certain times of year. Even in August the weather can be mixed. Indeed the day we visited it was very windy and at times rather wet!

The Brough is well worth the effort of a visit though as it has a well preserved ruins of a Viking settlement and useful information displays. This one talks about Earl Thorfinn one of the most powerful of the Viking Earls who died circa 1065. The Orkneyingas Saga says Birsay was his home (although it might mean the mainland opposite the island, no one knows) and also records he was buried here:

Earl Thorfinn retained all his dominions to his dying day, and it is truly said that he. was the most powerful of all the Earls of the Orkneys. He obtained possession of eleven Earldoms in Scotland, all the Sudreyar (Hebrides), and a large territory in Ireland. … Earl Thorfinn was five winters old when Malcolm the King of Scots, his mother’s father, gave him the title of Earl, and after that he was Earl for seventy winters. He died towards the end of Harald Sigurdson’s reign. He is buried at Christ’s Kirk in Birgishrad (Birsay), which he had built.

The Brough of Birsay was settled from the 7th to the 13th centuries AD. Today there are remains comprising of a 9th-century Viking-Age settlement as well as of the later 12th-century monastery and some evidence of the earlier pre Viking Pictish settlement of the 7th to 8th centuries.

This is the hearth found in a Norse house towards the east side of the island and reconstructed at the main site.

It is very easy to see the outlines and foundations of a dozen or so houses – some with multiple interior rooms. The Vikings here had some home comforts. There is even evidence of under floor heating and a smithy.

Birsay’s glory days of the 11th century soon passed however when the focal point of the Island shifted to Kirwall where the cathedral of St Magnus took over as the religious seat for the island in the 12th century.

Today Birsay remains a beautiful, striking location that was fun to visit – even on wet and windy day.

[image error]