Gordon Leidner's Blog

February 19, 2018

Presidential Humor

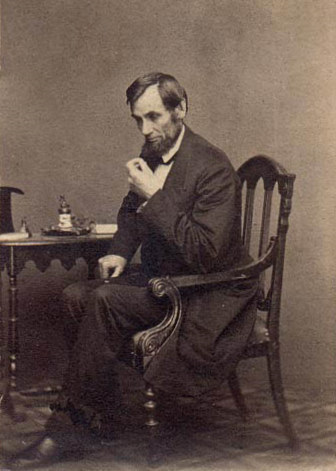

In honor of President's Day, here's a short introduction to Abraham Lincoln's humor:

Today we think of Abraham Lincoln as a great leader—perhaps our greatest. We recall his eloquent speeches, his dedication to the Union, and his superior leadership. We honor his devotion to duty, sacrifice, and honesty.

What we don’t think of today when we think of Abraham Lincoln is "a good joke." In Lincoln’s day, however, he was a well known humorist and story teller. The anecdote about two Quaker women discussing Lincoln and Confederate president Jefferson Davis at the beginning of the Civil War is illustrative: The first Quaker lady said, after some contemplation, that she believed the Confederacy would win the war because "Jefferson Davis is a praying man." “But Abraham Lincoln is a praying man too,” the second Quaker lady protested. "Yes," the first admitted, "but the Lord will think Abraham is joking."

Lincoln inherited his penchant for jokes and story telling from his father, Thomas Lincoln. When Abe was a child he loved to listen to his father and other men swap yarns around the woodstove. As he grew older he became increasingly adept at telling and re-telling humorous stories, frequently modifying them to accommodate each situation. When Lincoln became a lawyer, he used his jokes and stories to gain the good will of juries, and more than once his opposing counsel would complain to the judge that Lincoln’s stories were irrelevant and distracting to the jury. The trouble for them was that Eighth Circuit Judge David Davis loved Lincoln’s jokes more than anyone else in the court room.

Typical of a joke Judge Davis loved was one which Lincoln told to poke fun at himself: I feel like I once did when I met a woman riding horseback in the woods. As I stopped to let her pass, she also stopped, and, looking at me intently, said: "I do believe you are the ugliest man I ever saw." Said I, "Madam, you are probably right, but I can’t help it!" "No," said she, "you can’t help it, but you might stay at home!"

Another one of Lincoln’s 8th Circuit yarns was the one about a man in Cortlandt county who had raised a hog of such tremendous size that people came from miles around to see it. One of the people saw the hog’s owner and inquired about the animal. "W’all, yes," the old fellow said: "I’ve got such a critter, mighty big un, but I guess I’ll have to charge you about a dollar for lookin’ at him." The stranger glared at the old man for a minute or so, handed him the desired money, and started to walk away. "Hold on," said the old man, "don’t you want to see the hog?" "No," said the stranger. "Lookin at you, I’ve seen as big a hog as I ever want to see!"

He told another story of a time he was splitting rails when a man carrying a rifle walked up to him and demanded that Lincoln look him directly in the eye. Lincoln stopped his work and obliged the man, who continued to silently stare at him for some minutes. Finally the man told Lincoln that he "had promised himself years ago that if he ever met a man uglier than himself, he would shoot him." Lincoln looked at the man’s rifle mischeviously and said nothing. Finally Lincoln pulled open his shirt, threw out his chest, and exclaimed, "If I am uglier than you, go ahead and shoot—because I don’t want to live!"

LIncoln continued to use humor throughout his life, often to illustrate political points he wanted to make or to lift himself out of a melancholy mood.. He genuinely enjoyed laughter, and sharing stories with friends.

Unlike humor that is so commonly used today, however, Lincoln rarely used his wit to insult or injure his opponents. We could all learn a lot from this example!

FOR FURTHER READING:

See my latest book on Lincoln's Humor: Lincoln's Gift: How Humor Shaped Lincoln's Life and Legacy by web author Gordon Leidner.

December 9, 2017

Where are the Founding Fathers When You Need Them? Part 3: George Washington

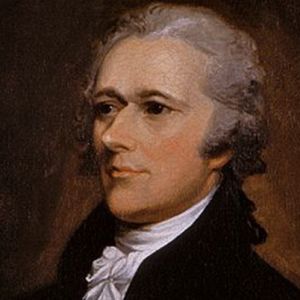

In Part 2 of “Where are the Founding Fathers When You Need Them?” we considered Alexander Hamilton’s impact as a leader. In this, Part 3, we will consider the leadership of the most famous of the Founding Fathers, George Washington.

During the American Revolutionary War, Congress gave George Washington the most difficult task of all the Founding Fathers when they commissioned him as Army Commander-in-Chief on June 19, 1775. His task was to lead the fight against the occupying armies of Great Britain—the most powerful military force on earth—and somehow win victory in the face of nearly impossible odds.

The British had large, well-disciplined armies of professional, battle-hardened soldiers stationed in key cities of the American colonies. Washington had to challenge the Redcoats with his smaller, loosely-organized forces that consisted of poorly trained militia  and unreliable volunteers. The British Army had a well-organized system of logistics that could deliver ample supplies of weapons and food, backed by a strong navy that could provide rapid transport. Washington had to count on whatever supplies that could be conjured up by an inept Congress, small businessmen, and local farmers. Whereas the British were well-fed and well-supplied, Washington’s army was in short supply of uniforms, warm clothing, food, and shoes. The British officer corps was well-trained, highly disciplined, and proficient in the art of war. Most of Washington’s officers had no formal training, little regard for discipline, and had never led men in battle.

and unreliable volunteers. The British Army had a well-organized system of logistics that could deliver ample supplies of weapons and food, backed by a strong navy that could provide rapid transport. Washington had to count on whatever supplies that could be conjured up by an inept Congress, small businessmen, and local farmers. Whereas the British were well-fed and well-supplied, Washington’s army was in short supply of uniforms, warm clothing, food, and shoes. The British officer corps was well-trained, highly disciplined, and proficient in the art of war. Most of Washington’s officers had no formal training, little regard for discipline, and had never led men in battle.

Why was George Washington chosen to be the leader of the American Continental forces?

There were several obvious reasons, such as the combat experience he had gained during the French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763. Fighting on the side of the British in that conflict, he became a capable officer that demonstrated admirable leadership skills in battle. In addition to this military experience, Washington was also a well-known civic leader, an influential resident from the important state of Virginia, and the wealthy owner of a large tobacco plantation.

Even though combat and civic experience were important reasons, Congress needed more than these to put the nation’s fate in Washington’s hands.

The “clincher” for the choice of Washington was this: More than any other leader of his time, George Washington was recognized as a man of unquestioned moral integrity. He was universally acknowledged to be honest, patient, trustworthy, and of sound judgement. Taken together, these qualities and character traits made Washington “the unanimous choice” of Congress for the critical role of Commander-in-Chief.

Although political leaders such as Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin would later give the new nation the inspiring vision defined in the Declaration of Independence, Congress discerned that in 1775, at the beginning of the war, it was the army that would decide America’s future. Knowing that they could provide the army little in the way of supplies or wages, Congress recognized it was of ultimate importance that the soldiers have a respected commander to follow.

According to modern leadership theory, moral integrity is an essential quality for a leader. As explained in Part 1 of this blog series, Historians and leadership theorists today recognize the Founders as “transformational” leaders. Transformational leaders are the best kind to have around when you happen to have a war that needs winning or a new nation that needs establishing. They display the unique ability to inspire followers to make personal sacrifices and go beyond their own self-interests for the good of the larger group (the “group,” in Washington’s case, was the entire American people). Transformational leaders are inspirational because they recognize and communicate “the right thing to do.” With their moral integrity and inspirational leadership, they earn the trust, loyalty, and respect of their followers.

Ultimately, transformational leaders inspire their followers to “go above and beyond” in their cause, and they in turn become inspired by the dedication and leadership their followers develop. Both leaders and followers—according to leadership theorist James MacGregor Burns—raise one another to “higher levels of morality and motivation” in pursuit of their righteous cause.

My book The Leadership Secrets of Hamilton: 7 Steps to Revolutionary Leadership from Alexander Hamilton and the Founding Fathers illustrates several additional transformational leadership skills that the Founders employed to motivate the American people to persevere in the Revolutionary War and establish the world’s first successful democratic nation. In addition to “exemplify moral integrity,” the book discusses the transformational leadership skills of “go beyond self-interest,” “establish clear goals,” “respect your people,” and “convey an inspiring vision.” The Founders’ techniques in using these skills are brought out with historical anecdotes, biographical sketches, and inspirational quotes.

February 4, 2017

Where are the Founding Fathers When You Need Them? Part 2: Alexander Hamilton

Most of America’s Founding Fathers were raised in either stable or advantaged families in the American colonies. George Washington and James Madison, like several other Founders, grew up on their families’ large plantations. Thomas Jefferson once said that his earliest memory was being carried, while lying on a pillow, by one of his father’s slaves.

Not so, Alexander Hamilton. He was born out of wedlock, raised in a disadvantaged family in the Caribbean, and orphaned when thirteen years of age.

At the age of 14, Hamilton became a clerk at a local import-export firm on the island of St. Croix. Hamilton’s employer soon learned that his young clerk was “a quick study,” and by the age of 17 Hamilton had learned all aspects of running the business. He was put in complete charge of the company for months when the owner put out to sea.

When not clerking, Hamilton voraciously devoured books on a wide variety of subjects, and wrote poetry and articles for a local newspaper. Municipal leaders on St. Croix decided that this talented, amiable youth should be given an opportunity to improve himself. They pooled their resources and sent Alexander Hamilton to New York to pursue a college education.

Hamilton was formally enrolled in New York’s King’s College (now Columbia University) in 1774. At King’s College, Hamilton’s powerful mind, exceptional work ethic, and agreeable personality soon earned him the respect and friendship of both peers and professors. Hamilton became supportive of the movement for America’s independence from Great Britain, and he wrote articles in support of the actions of a patriot organization known as the Sons of Liberty. He supplemented his academic pursuits with studies in the military arts, and after the first shots of the rebellion were fired in 1775, twenty-year-old Hamilton joined a New York volunteer militia company.

Hamilton’s natural leadership abilities earned him the rank of captain of artillery, and his courage and good judgement in battle soon gained the attention of general George Washington. Recognizing Hamilton’s leadership qualities, Washington asked Hamilton to join his staff. The young officer was soon writing orders, substituting for Washington in meetings, and dealing with Congress on the general’s behalf. Washington depended on Hamilton’s judgement and gave him responsibilities that were far beyond what most young men his age could ever expect to receive. In the last major battle of the Revolutionary War, Hamilton led a charge against the British ramparts at Yorktown, and was credited with taking a fort that soon forced the British army’s surrender, and the end of the war.

Eight years later, when George Washington became president, he asked 34-year old Alexander Hamilton to become the first Secretary of the Treasury. It was in this role that Hamilton’s powerful mind was fully utilized. He proposed to Congress several brilliant plans for a complete overhaul of the struggling American economy. He proposed a national bank, a system of collecting revenue via taxation, a method of relieving the country’s overwhelming debt, and a plan for building a new American economy based on manufacturing of goods.

Hamilton founded the nation’s first indigenous political party, the Federalist, and led the fight against Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party. The ideological battles these two men fought—one favoring a strong central government, powerful banking system, and strong manufacturing economy and the other favoring a weak central government, state rights, and agricultural economy—formed the basis for the two-party American political structure that has survived to the present day.

Hamilton was a brilliant visionary but he had an aristocratic leadership style, was highly impetuous, and usually impatient with his political foes. He openly waged an intellectual and ideological war with Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had a strong mind also and was no less aristocratic than his opponent from New York, but as a Virginia plantation owner he had subtle (some would say underhanded) ways of fighting back. Jefferson became America’s third president, but we shall never know how far Hamilton would have gone politically. He was shot and killed in a duel by an equally impetuous man—Thomas Jefferson’s Vice President Aaron Burr—when Hamilton was only 49 years old.

Interesting topics for students to consider in regards to Alexander Hamilton are what would have happened if he had lived longer. Hamilton was adamantly opposed to slavery, and Thomas Jefferson in favor of it. Would Hamilton have had an interest in halting slavery’s expansion? If Hamilton had lived, would the South’s economy have become less agriculturally-centric? Or would the North’s economy have overwhelmed and diminished the political influence of the South? If Hamilton’s Federalist Party had survived longer, would Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party have lost power? Would a Federalist have become president in 1809 instead of Democratic-Republican James Madison? Would the American Civil War have ever happened?

For a brief introduction to Hamilton and the Founding Fathers as leaders, I suggest my new book Leadership Secrets of Hamilton: 7 Steps to Revolutionary Leadership from Alexander Hamilton and the Founding Fathers, published by Simpletruths.com. But for a more in-depth study of Hamilton, Washington, and Jefferson I recommend Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America by Stephen F. Knott and Tony Williams.

January 14, 2017

Where are the Founding Fathers when you need them?

The Broadway play “Hamilton” is all the rage now, highlighting with song and dance the life and accomplishments of the Founding Father whose portrait graces the American $10 bill–Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton has, for the last few decades, been one of the less famous of the Founders—several paces behind George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams. But why? After all, it was Hamilton that was George Washington’s “right hand man” during the Revolutionary War, it was Hamilton who was largely responsible for the ratification of the US Constitution by the states, it was Hamilton who laid the foundation of the powerful United States economy, and it was Hamilton who formed the first American political party, the Federalist Party.

Yes—this was the Alexander Hamilton who grew up in poverty on the island of St. Croix, was orphaned and working as a clerk at the age of 13, who immigrated (alone) to New York at the age of 17, and was a college student in New York when the Revolutionary War began.

In my upcoming book, The Leadership Secrets of Hamilton: 7 Steps to Revolutionary Leadership from Alexander Hamilton and the Founding Fathers (published by Simpletruths.com, and on bookshelves February 7, 2017) I discuss the leadership skills of Hamilton and six other Founders (Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Adams, Franklin, and Henry). The book serves as a brief introduction to the most significant accomplishments of the Founders: winning the Revolutionary War, writing the Declaration of Independence, the writing and ratification of the US Constitution, and the establishment of the first surviving democratic government. But more than that, Leadership Secrets of Hamilton uses modern leadership theory to illustrate how the Founders accomplished these tasks.

Historians and leadership theorists today acknowledge that the Founders were “transformational” leaders. Transformational leaders, it turns out, are the best kind to have around when you have a war to win or a new nation to establish. This is because transformational leaders are known for their ability to inspire followers to make personal sacrifices and go beyond their own self-interests for the good of the larger group (which in the Founders case, was the entire American people). Transformational leaders are inspirational because they recognize and communicate “the right thing to do” and by exemplary leadership earn the trust, loyalty, and respect of their followers.

Ultimately, the transformational leaders not only inspire their followers, but by turning their followers into leaders they become inspired by their followers too. Both leaders and followers—according to leadership theorist James MacGregor Burns—raise one another to “higher levels of morality and motivation” in pursuit of their righteous cause.

So, how did the Founders earn the trust and respect of their followers? Why were thousands of Americans willing to fight and die in the Revolutionary War? Why did they support their new government and ratify their new, controversial US Constitution? Even more important, where are the leaders today like Hamilton and Washington that can inspire the trust, loyalty, and respect of the American people?

To begin to answer these questions, something I will do in future blog posts, we will first look more closely at the leadership skills of Alexander Hamilton and the Founding Fathers.

June 28, 2013

Is the Abraham Lincoln quote from the movie “White House Down” accurate?

In the new Columbia Pictures movie, White House Down starring Channing Tatum and Jamie Foxx, Lincoln was alleged to have said "America will never be destroyed from the outside. If we falter and lose our freedoms, it will be because we destroyed ourselves." Is it correct?

No, Lincoln did not say that, but he did say something similar—which is apparently the statement on which Hollywood has based their mis-quote. In 1838, the 28-year old Lincoln said the following in a speech in Springfield, IL: “If destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.”

[image error]

This is an excerpt of a speech entitled “The Perpetuation of our Political Institutions: Address Before the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois” January 27, 1838. The full quote regarding this subject is below:

“Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant to step the ocean and crush us at a blow? Never! All the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest, with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not by force take a drink from the Ohio or make a track on the Blue Ridge in a trial of a thousand years. At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer. If it ever reach us it must spring up amongst us; it cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.” (from Basler, Collected Works of Lincoln, v. 1, p. 108)

In this speech Lincoln was warning his listeners of the threats of lawlessness to America. He saw slavery as an instigator of lawlessness, and also feared the rise of a tyrant or dictator that would be allowed by the people to place himself above the law. Lincoln believed that respect for the laws, adherence to the political principles espoused by the Founding Fathers, and reliance on reason would help prevent this failure “from within.” Many times he warned Americans that it was up to them, as citizens, to keep destruction of America “by suicide” from happening.

Here is another example of what Lincoln said in regard to his fear of the rise of a tyrannical leader:

“While the people retain their virtue and vigilance, no administration by any extreme of wickedness or folly can very seriously injure the government in the short space of four years.” (First Inaugural Address, Abraham Lincoln, March 4, 1861).

So, how virtuous and vigilant are the American people today??

See another GAH article on Lincoln quotes and misquotes here.

March 27, 2013

Why all the confusion about Abraham Lincoln’s religious beliefs?

So, why is there so much confusion about Abraham Lincoln’s religious beliefs? Was Lincoln a Christian? Was Lincoln an atheist? Did he believe in the truth of the Bible? It seems that everyone tries to prove their viewpoint of Lincoln's religious beliefs by pointing to one or two of their favorite Lincoln quotes.

This really shouldn’t be that difficult. Like most people, Lincoln’s religious beliefs evolved  over his lifetime. After all, who maintains the exact same religious beliefs all their lives? In his youth, Lincoln attended with his parents what was called a “hardshell” Baptist church. Typical of children everywhere, he went to church and listened to the lessons and sermons. Atypical of children everywhere, he sometimes memorized them.

over his lifetime. After all, who maintains the exact same religious beliefs all their lives? In his youth, Lincoln attended with his parents what was called a “hardshell” Baptist church. Typical of children everywhere, he went to church and listened to the lessons and sermons. Atypical of children everywhere, he sometimes memorized them.

When Lincoln left home at the age of twenty-one, he went through a period of skepticism towards Christianity. While he was in New Salem, Illinois he pursued intellectual arguments of individuals like Thomas Paine (who was a deist) and openly questioned the validity of the Bible. Some scholars believe that this was a result of his desire to distance himself from the Calvinist faith of his Father, with whom Lincoln had developed an estranged relationship. Some think it was just a natural result of Lincoln’s intellectual development, as evidenced by his studying of law, Euclid’s theorems, and logic.

It is the skeptical Lincoln of his twenties and thirties that atheists like to point to in their efforts to claim him as their own. They, as well as many scholars, seem to have difficulty looking beyond this phase of Lincoln’s life.

But as Lincoln grew older, got married, and raised children, his skepticism diminished. He had always read the Bible, even during his cynical years, and when the Abraham and Mary Lincoln experienced the tragic death of their second son Eddy in Springfield, they sought solace from the message of love and hope of the Bible. Lincoln developed a close relationship with the minister of the First Presbyterian Church in Springfield, Dr. James Smith, and began attending this church with Mary.

Skeptics of Lincoln’s Christianity make a big deal of the fact that Lincoln never “officially joined a church," although by the time he was President he attended services frequently. This is hardly proof that he had no faith. Many Christians today are not formal members of a church.

It was when Lincoln became president that the most significant change seemed to happen regarding his religious beliefs. His writings, while President, are the obvious evidence of his deepening faith in God. Additionally, there are testimonies of people that knew him while he was in the White House, who describe his increasing faith. The Civil War, and the associated deaths of hundreds of thousands of soldiers, was a constant torment to him. The loss of a second son, Willie, while in the White House caused Lincoln to draw closer to Phineas Gurney, his pastor at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church. The fact that Lincoln prayed and read the Bible regularly while President is well documented. In 1862 he pondered God’s purpose for the Civil War in his “Meditation on Divine Will.” By the time he wrote his famous Second Inaugural Address, something any minister of the Bible would be proud of, he had reached his conclusions about how God was using the war. He believed that God allowed the Civil War as punishment for the nation’s sin of slavery. He quoted from scripture in the Second Inaugural, “The judgements of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

So even though Lincoln had deistic and atheistic sympathies when he was a young man, he had clearly changed by the time he became President. President Lincoln not only believed in God, but he also believed that God answered prayer. He believed that God intervened in American history. So he was clearly a Theist rather than Deist or Atheist. To say that Lincoln was a born-again Christian, however, goes beyond the evidence. This would have required him to make statement of personal faith, and there is no reliable evidence that Lincoln ever accepted Christ as his personal savior. By the time he was President, Lincoln is most accurately categorized as a “believer” in Christianity. It is known that he read the Bible regularly, he prayed, and he talked about “the Savior" (but not “his Savior"). Some believe that if had Lincoln lived, his intention was to join a church and formally declare his faith in Christ. We will never know. What his exact relationship with God was at the time of his death, “the Lord only knows.”

For more on Lincoln’s faith, including his writings about God, go to Great American History's Lincoln’s Faith.

The two best books I know of on the subject of Lincoln’s faith are Allen Guelzo's Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (Library of Religious Biography) and Stephen Mansfield’s Lincoln's Battle with God: A President's Struggle with Faith and What It Meant for America Both cogently discuss Lincoln's evolving faith.

and Stephen Mansfield’s Lincoln's Battle with God: A President's Struggle with Faith and What It Meant for America Both cogently discuss Lincoln's evolving faith.

December 31, 2012

The religious beliefs of America’s Founding Fathers: Christians or deists?

The religious beliefs of the Founding Fathers is one of the most widely misunderstood characteristics of early America’s leaders. Today, they are usually declared to have been either deists or Christians, but in actuality, most of them were neither.

Although the vast majority of the 55 members of the Constitutional Convention were affiliated with the major Christian churches of their day (and would have probably have considered themselves Christian), the number of them that fully accepted the major tenets of the Christian faith is uncertain. A careful reading of many of the Founders’ public and private communications demonstrates they had the following in common: (1) belief in a personal God, (2) familiarity with the Bible, and (3) belief in prayer. But acknowledgement of Christ as their personal Savior and acceptance of the other commonly held Christian beliefs is less manifest.

Many secularists today claim that instead of being Christians, the Founders were deists. But there is even less support for mere deism than there is for Christianity. Deists believe in the existence of a creator God, but do not believe He intervenes in human affairs. Contrary to believing in an indifferent Creator, most of the Founders took the position of the Theist—that prayer is important because God intervenes in the affairs of mankind. Even a casual reading of the writings of Founders such as George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams demonstrates this.

It is true that a few of the Founders (such as Thomas Paine) were deists, and that some of the Founders (such as Alexander Hamilton) were Christians. But the majority of the Founders were somewhere in between. Their beliefs were, in fact, in line with something that is becoming increasingly described as theistic rationalism.

According to scholar Gregg L. Frazer, theistic rationalists “believed in a powerful, rational, and benevolent creator God who established laws by which the universe functioned. Their God was a unitary personal God who was present and active and who intervened in human affairs. Consequently, they believed that prayers were heard and effectual. They believed that the main factor in serving God was living a good and moral life, [and] … morality was central to the value of religion.” Most of the Founding Fathers read, referred to, and/or believed in (to varying degrees), the Bible. Instead of accepting the entire Bible as divinely inspired, however, many believed that “reason” was the ultimate standard for determining which parts of the Bible was legitimate revelation from God.

Theistic rationalism is a belief system, not a religion. As mentioned previously, most of the Founders were associated with and/or attended Christian churches. But the Founders were a product of not only Christianity, but also the political ideologies of the Enlightenment. They read scripture, but they also read the philosophies of John Locke, Voltaire, and Montesquieu. As Frazer says in his book The Religious Beliefs of America’s Founders, theistic rationalism was “a belief system for the educated elite.” Educated elite describes not only founders such as Jefferson, Adams, and Madison, but also many of the Revolutionary Era’s preachers and seminary professors.

Personally, I would have had a hard time believing these conclusions if I had not researched the religious beliefs of the Founders for my upcoming book The Founding Fathers: Quotes, Quips, and Speeches, (to be published by Sourcebooks in May of 2013). I examined a great deal of biographical material and writings of Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Hamilton, Henry, Paine, Madison, Franklin, and others. Being a Christian, I had hoped to demonstrate that they were not deists, which—with the exception of Thomas Paine—was easily done. But I had also hoped to find evidence that they were truly Christian—a conclusion that proved elusive. The internet has many quotes that would lead one to believe that the Founders were Christian, but after thorough examination I found that most of those quotes are not among the Founders’ original papers or traceable further back than the late 1800’s—long after the Founders had died.

For most of America’s Founding Founders, their religious writings support two primary positions: (1) The God of the Bible governs the affairs of mankind, and (2) each person should have the freedom to worship Him as he or she sees fit. Although these beliefs are more than deism, they are not, by themselves, sufficient for Christianity. Theistic rationalism is a reasonable description of the Founders' beliefs.

November 29, 2012

The REAL Leadership Lesson for Obama from Abraham Lincoln

If President Barack Obama, or anyone else for that matter, wants to learn Lincoln’s leadership skills, he’ll need to do more than watch the two and a half hour Spielberg movie, Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln’s most enduring leadership skills were transformational—the ability to inspire—rather than transactional—the ability to trade. Spielberg’s movie primarily highlights Lincoln’s transactional skills, so the Hollywood pundits and political bloggers, armed with their new-found expertise on Lincoln, tell Obama that Lincoln’s message on leadership involves simply “procuring votes” or “making it happen.” They pick their favorite topic—such as environmental legislation—and tell Obama to ignore the protests of congress and force things through.

But historians that have studied Lincoln know that the presidential leadership style displayed in Spielberg’s brilliant movie was only one of the leadership methods employed by the 16th president. It was rare that Lincoln simply used his “horse trading” skills and his “immense power” as president to lead. If his leadership skills had been as one dimensional as that, he would have failed to either free the slaves or keep the Union together. Today we would not be the “united” states.

As can be seen from this previously published article on his transformational leadership skills, Lincoln used more than one management style during his years in the White House. It is true that Lincoln frequently used “transactional” leadership, where the leader “procures” a follower’s support (as he did with several holdout Democrats in the movie). But Lincoln’s true genius was his use of “transformational” leadership to change the hearts and minds of millions.

Transformational leadership motivates followers by activating their “higher order” needs—such as their sense of justice and equanimity. Followers are challenged to look beyond how they can personally benefit, and to make personal sacrifices in order to do something for the greater good of society. As can be seen in this article on the comparison of Lincoln’s leadership skills to Jefferson Davis’s, Lincoln’s use of transformational leadership is what inspired many, including millions of Union soldiers, to be willing to risk their lives to (first) preserve the Union, and (second) to free the slaves.

A brief glimpse of Lincoln’s transformational leadership skill is shown in the movie, when he talks to Congressman George H. Yeaman of Kentucky about supporting the Thirteenth Amendment to free the slaves. Lincoln does not offer anything that would personally benefit the congressman, but instead appeals to his sense of justice. Lincoln tells Yeaman why he had always believed slavery was a moral wrong, and asks the congressman to “disenthrall” himself with the slave powers to support the passage of the amendment. He ends his plea to the congressman with a simple request to “see what you can do.” Later, in one of the most emotional scenes of the movie, the congressman—who had formerly been the Democratic Party’s floor leader in the opposition to the Thirteenth Amendment—changes his mind and votes in its favor.

The final scene of Spielberg’s’ movie shows Lincoln the transformational leader at his pinnacle—presenting the concluding lines of his second inaugural address: “With malice toward none, with charity for all …” This was Lincoln’s final plea to the war-ravaged nation to “seek a lasting peace” with all nations and “to care for him who shall have born the battle” on both sides. This speech, along with the Gettysburg Address, is the hallmark of Lincoln’s leadership.

So the Lincoln leadership message to Obama is not simply one of partisan politics, or buying votes, or getting your political party’s way on a particular act of legislation. It involves, instead, looking into the future towards “the millions yet unborn,” and pursuing their greater good. It is true that there will always be people that are only motivated by personal benefit, or party politics, or opinion polls. But Abraham Lincoln is remembered for how he inspired millions of followers to go beyond their own self-interest and make sacrifices for the benefit of mankind, not on how good he looked in the morning newspapers.

October 26, 2012

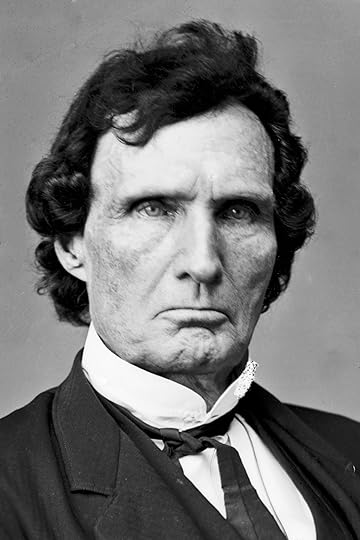

Civil War Term Paper Topic: Abraham Lincoln, Thaddeus Stevens, and Passage of the Thirteenth Amendment

An interesting research paper topic is Abraham Lincoln, Thaddeus Stevens, and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. Abraham Lincoln, as President of the United States, and Thaddeus Stevens, as the leader of the “radical” Republicans and Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, both had an interest in abolishing slavery. The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment was their mutual goal. But Stevens and Lincoln had radically different personalities, as well as radically different methods of leadership, and were in frequent conflict. In the end, they successfully worked together to pass the 13th Amendment and put an end to slavery in the United States, but how they did this, and the obstacles they faced, is a fascinating story.

Thaddeus Stevens, Republican from Pennsylvania, was the undisputed leader of the radical Republicans that wanted slavery terminated immediately at the beginning of the Civil War. Unfortunately for Stevens and other abolitionists, they did not have sufficient political clout to do this. The majority of the Democrats in congress opposed the abolishment of slavery, and the majority of the soldiers that had enlisted in northern armies did not believe, at least at the war’s inception, in risking their lives for the slaves. They were fighting to “preserve the Union.”

Stevens, the only member of the House of Representatives to ever be known as “dictator,” did not care if he was popular or respected. But his methods of intimidation had less influence across the aisle with the Democrats. His inability to impose his will with the opposing party frustrated him almost as much as his inability to intimidate Abraham Lincoln—whom Stevens perceived as “tardy” on the slavery issue. Lincoln, as leader of the entire country, understood that it would take cooperation among both political parties, as well as the support of soldiers and citizens of the North, to build the sort of consensus that would pass the Thirteenth Amendment in Congress and then attain its ratification by two-thirds of the state legislatures. To do this, Lincoln had to not only transform the war’s purpose from preserving the Union to freeing the slaves, but he also had to use all his political skill to convince enough congressional Democrats to switch sides in the slavery debate.

When the Thirteenth Amendment was brought to a vote in Congress in April 1864, it was passed by the Senate with a vote of 38 to 6. But the required two-thirds majority was defeated in the House of Representatives by a vote of 93 to 65. The attempt to abolish slavery in 1864 was almost exclusively a Republican Party effort–only four Democrats voted for it.

Consequently, many influential members of congress argued that Lincoln should wait until the next congress was elected and re-submit the Thirteenth Amendment, hoping for success with it then. But Lincoln would have none of it. He was convinced that he at last had an opportunity to end slavery—an institution that he had deplored since he was a young man—and did not want to take chances. He personally led the fight to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, and used all of his political skills to change the mind of reluctant Democrats.

Consequently, the 38th Congress—the same congress that had rejected the Thirteenth Amendment less than 9 months earlier, passed it on January 31, 1865 and sent it to the states for ratification. The vote in the House of Representatives was 119-56. All 86 republicans voted for it, along with 15 democrats and 18 members of the Union Party. 50 Democrats still opposed it, but Lincoln—and Stevens—had succeeded in their goal.

The details of how they did this—their personal relationship, their correspondence, their political maneuvers—is highly illustrative of how the American political process is supposed to work. Interesting research questions on this subject include: (1) Would Lincoln have acted as quickly on the emancipation issue if Thaddeus Stevens had not been so adamant about its immediate passage? (2) Was Lincoln’s sense of timing for the abolition of slavery better than Stevens’s? (3) What if Lincoln had waited for the 39th Congress to address the passage of the 13th Amendment—would it have successfully passed? (4) Who were the democrats that Lincoln swayed to support the 13th amendment and what political deals did he offer? (5) Why was the Democratic party so adamantly against freeing the slaves?

Worthwhile places to start your research are the Outline of the Civil War and the Thirteenth Amendment.

October 8, 2012

Research paper topic for the Civil War: Abraham Lincoln and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment

Abraham Lincoln and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States, is a dramatic chapter of American history. The US Constitution, when it went into effect in 1789, had guaranteed the institution of slavery in America. In the early to mid-1800's, slavery became an increasingly divisive force in the country, with virtually the entire southern populace and many northern Democrats supporting it; and much of the North, particularly the Republican Party, opposing it. When Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the South decided to secede from the Union rather than risk the potential loss of slavery.

The only way slavery could be permanently ended was via passage of an amendment to the Constitution. But when Lincoln took office in 1861, the passage of an amendment to end slavery was an extremely remote possibility. Even with the departure of the South’s elected representatives from the US Congress, and the election of a Republican president that opposed slavery, the anti-slavery forces in Congress still had an uphill fight. Not only did a large percentage of northern Democrats support the continuation of slavery, but the majority of northern soldiers did not want to risk their lives for freedom for the slaves. Many had enlisted to fight for the Union, and no more.

Although he hated slavery, Lincoln recognized how most of the northern people felt about slavery when he took office, and made the primary purpose of the war effort to put down the rebellion and preserve the union of the states. But he watched for an opportunity to end slavery as well.

Ending slavery would require all of Lincoln’s leadership skills. First of all, he had to convince thousands of northern soldiers to be willing to fight, suffer, and possibly die to end slavery. He had to convince the northern public that freedom for the slaves was worth the potential sacrifice of the lives of their sons, fathers, and husbands. He had to convince the northern congressional democrats to go against their own reluctance to end slavery. He had to do all of this in the course of the most costly, bitterly-fought war the nation would ever endure.

After the Battle of Antietam, nearly eighteen months after the war began, Lincoln saw his opportunity. He decided to make use of his war powers as president to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which promised freedom to slaves in the southern states. How he gained support for this is an interesting story in itself. He had to not only to secure the support of the soldiers, but also overcome the doubt of many of the influential members of his own political party.

Lincoln's issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation was a huge step towards freedom for the slaves, but the amendment was still necessary to guarantee it. Surprisingly, the first effort to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, ending slavery, suffered a defeat in the House of Representatives by a vote of 93 to 65. Only four democrats voted in favor of eliminating slavery.

After this defeat, Lincoln took personal charge of the effort to reverse the vote of the reluctant democrats, and managed to sway enough votes that the Thirteenth Amendment succeeded in Congress the second time. It was passed in January, 1865 by a vote of 119-56 and sent to the states for ratification.

Questions that could be researched on the subject of Lincoln and the Thirteenth Amendment are: (1) Why did northern democrats oppose the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, and who were the democrats that switched their vote? (2) How did Lincoln convince them to change sides? (3) What would have happened if Lincoln had not quickly intervened, or had been assassinated before the Thirteenth Amendment passed–would slavery have been left intact at the war’s close? (4) Finally, and this is probably the most complicated, how did Lincoln convince the northern soldiers and northern people to lay aside their personal interests and make the sacrifices necessary to free the slaves?

Great American history has numerous resources on these subjects, including The Thirteenth Amendment, Lincoln the Transformational Leader, and the Outline of the Civil War.