Mark Chadbourn's Blog: Jack of Ravens

October 18, 2025

The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke -Out Now

It’s been a long time coming, but I’ve finally got my British Fantasy Award-winning story The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke back into print as an affordable paperback and ebook.

The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke painting hangs in the Tate in London and was created by Richard Dadd while he was incarcerated in the notorious asylum Bedlam. The story tells of Danny who goes on a quest to discover if it’s a portal to Faerie, as some say, only to find himself opening up another door, one that leads to memory and madness.

It’s available in all territories, but here are links to the UK and US editions.

July 22, 2025

Everything Is Connected

You’re floating along a broad, slow-moving river. The landscape on either side is familiar, peaceful, with outcrops of wildness. Suddenly you flow into a gorge where the furious whitewater threatens to flip over your raft and drown you.

Between those towering walls of stone, you have no idea where you are. You just know that if you want to survive you have to cling on for dear life.

This is where we are now. The world is nothing but turbulence as every unresolved issue of the twentieth century plays out at once. And we have no idea where we are going until the river opens out again into the new, flat countryside.

I first came across that analogy years ago in The Meaning Of The 21st Century: A Vital Blueprint For Ensuring Our Future, a prescient book by the technologist James Martin. It perfectly encapsulated the upheavals that were coming as the twin Ages of Digital Technology and Communication disrupted everything.

That turbulence isn’t getting any less. If anything our pitiful raft looks like it might not make it past those jagged rocks to find the promised land of abundance that allegedly lies ahead.

I’ve started writing on Substack every Friday in an attempt to drain a little of the terror out of our current situation by empowering people with news and information in a dangerous and confusing world. If we can peer through the spray and see the obstacles ahead, there’s a chance…a chance…we might be able to navigate a safe path until we’re out of this mess.

The more you know, the safer you are.

As my pinned post on Bluesky says: “The theme…is Everything is Connected. The posts cover news and politics from all over the world, things that I think it’s worth paying attention to but which may not always get priority in other media.

“Even if it happens five thousand miles away it can still roll up on your doorstep.”

Protests in Tbilisi in Georgia. A conflict between nuclear rivals India and Pakistan. The endless, bewildering upheavals of the Trump administration. The war in Ukraine. Death and destruction in the Middle East. Industrial sabotage in Germany. Warships in the South China Sea. Fascists in Brazil. Russian mercenaries in Mali.

Seemingly disparate events. But if you look closely you can see the strands that connect them all.

On Substack I’m going to be looking to the horizon to highlight flashpoints around the world. In the process this will bring into relief the interconnectedness of everything and will, hopefully, start to reveal what lies behind it all, like one of those Magic Eye pictures.

Not all the bad actors in the world stand centre-stage. The ones you really need to be concerned about are off in the wings, in the shadows, directing what’s going on under the spotlight.

They can’t stay hidden forever, though. The more information you have about global events, the more the light gets in.

Who really pushed for Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2023 which prescribes life imprisonment for sex between two people of the same biological sex and the death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality”, legislation that is now being copied in other African nations? And how are those same people flooding cash into the US, UK and EU to influence local politics?

Everything is Connected.

It isn’t the place to come for deep dives into policy on single issues. There are plenty of excellent academics and journalists giving that intensity of detail. It is the place to try to make sense of the big picture, delivered in an accessible style. Communication is key. Language is important.

A little about me: I trained as an economist. When I left university I immediately became a journalist, working on the big metropolitan newspaper in Birmingham, England, before moving to London to ply my trade in the large media organisations. There I started out as an undercover crime journalist before eventually reporting from around the world.

When my first novel was published, I quit my staff job, but kept all my contacts and my passion for journalism. That meant a few more bylines here and there, but my focus was on books and screenwriting.

Now though, the world is in a mess everywhere. The media we’ve trusted for decades is dying; not enough readers, not enough viewers, and it’s easy to see a day when it might not be around. Into the growing vacuum, those who seek power and money are flooding lies and deepfakes and propaganda to advance their agenda.

It felt an important time to me to use what skills and contacts I have to get important information out there. Hence my recent activity on social media and here on Substack.

Over the coming weeks I’ll be globetrotting. There may well be a lot of stuff about Trump America because that’s one of the prime sources of global disruption at the moment, but there will be plenty of other news from corners of the world where you may not be paying attention. The big picture will begin to appear.

The aim here, then, is to keep everyone on the raft.

Calmer waters lie somewhere ahead.

We just need to find the channels that will get us there.

June 23, 2025

Dancing While The World Burns

I’m back. You didn’t notice I was gone, did you?

Took a brief sabbatical because life is short and the world is an amazing place and sometimes you really need to disconnect from the grind to appreciate what we all have.

It seemed an important time to come back. Things are a mess right now. Science has been forging ahead and we’re on the brink of an amazing golden age of health breakthroughs. There’s enough money in the world to solve every problem in the world. The climate crisis can be met head on.

Instead we’ve got a small group of people in charge who are happy to sacrifice all that for their own gain. Power. Cash. That’s all that matters. Charlatans everywhere.

It would be easy to turn away and imagine you have no agency in the face of everything. Muddle on through the mundane things. But everyone has a voice and the only way things will change is if there’s a chorus that will drown out the authoritarian bleatings.

You stand for Life or you stand for the Void, as readers of my Age of Misrule books know too well.

I’ll be celebrating Life.

On the personal front, a major broadcaster has greenlit the adaptation of one of my books. More when I’m allowed. I’ve written a new novel. Two short stories are going to be out in a little while. And I’ve completed the pilot script for a TV series.

I guess the sabbatical is over.

Keep dancing, even if the world is burning.

April 7, 2025

De-Extinction

The dire wolf has been extinct for more than 10,000 years. No longer.

Now two wolves have been brought back from extinction using genetic edits derived from a complete dire wolf genome, reconstructed by Colossal Biosciences from ancient DNA found in fossils dating back 11,500 and 72,000 years.

The company says: “This moment marks not only a milestone for us as a company but also a leap forward for science, conservation, and humanity.

“From the beginning, our goal has been clear: To revolutionize history and be the first company to use CRISPR technology successfully in the de-extinction of previously lost species.

“By achieving this, we continue to push forward our broader mission on—accepting humanity’s duty to restore Earth to a healthier state.”

November 27, 2024

Why Labour Should Legalise Weed.

The New European asked me to write this piece (£££) on why the UK’s Labour government should legalise weed – to raise billions for public services, for social justice and for public health.

August 25, 2024

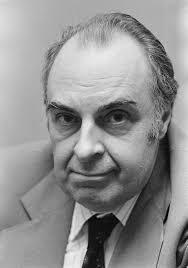

The King of Hauntology

Here’s a piece I wrote about the acclaimed screenwriter Nigel Kneale for the book We Are the Martians: The Legacy of Nigel Kneale.

‘Hauntology is not just a symptom of the times, though: it is itself haunted by a nostalgia for all our lost futures.’ ~ Andrew Gallix

‘To tell a story is always to invoke ghosts, to open a space through which something other returns.’ ~ Julian Wolfrey

The future is being forged on the west coast of England. Arcs of promethean fire cut through the dark of a long, long night. Hammers pound iron, tolling the end of one age, heralding the arrival of a new one. In the Vickers yards of Barrow-in-Furness, they are building sleek machines to probe the inhospitable reaches. Their conical noses and fins, their missions into silent darkness, these things will soon find an echo in the works of the British Experimental Rocket Group.

But for now it is 1922, and the vessels are submarines. Their promised future of technological marvels is just beginning to take hold. King George V is on the throne, David Lloyd George is in Downing Street, and Nigel Kneale is being born within the sound of those shipyard hammers, born into a liminal zone, between the sea and the land, between a past that is still clinging on, and a shining future, between superstition and science. It is a place he will inhabit for the rest of his days.

In the midst of life, it’s impossible to see the connections, the patterns. But rise above and look down and all becomes clear. Nigel Kneale is a baby. Nigel Kneale is an old man, acid and angry in public, kind in private to friends and family. He writes, books and TV and movies. He acts and marries and has children, thinks and complains and inspires. Somehow he finds a way to listen to the voices haunting his unconscious, and through their guidance manages to articulate a particular time and place, as all the best writers do. He doesn’t see that, of course. Hanging in the amniotic fluid as he focuses on this moment, and then the next one, and then the next, he hears only the distant boom and the thrum without realizing the invisible forces that pull and shape. But at the end, rising above it, looking down, we can see, we can understand.

In that Lancashire town, in 1922, those submarines are the future to all who lay eyes upon them. Yet still they are christened for luck, in the same way that the Babylonians did five thousand years before, and the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Vikings. Five thousand years of blood and wine to buy the fortunes of the gods. They will never begin their journey on a Friday, the day of the crucifixion. No women can sail with them, for fear they will bring bad luck. Every man who steps on board is drilled in the forbidden words, the words of power that were never to be uttered. Goodbye and drowned. Good luck brings only bad luck. The only way to break the spell is a punch that draws blood. Another sacrifice for the gods.

The submarines sail off into the future, one that comes hard on October 2nd 1925. John Logie Baird is successfully transmitting the first television picture. In the laboratory, the greyscale image is chilling, the head of a ventriloquist’s dummy named Stooky Bill. Silent, staring, jaw agape at what the world is coming to. Baird drags office worker William Edward Taynton into the experiment because he wants to see what a human face would look like. Taynton enters history. Baird enters the offices of the Daily Express, seeking fame. The terrified news editor thinks this is a madman. “Get rid of the lunatic,” he tells one of his reporters. “He says he’s got a machine for seeing by wireless. Watch him – he may have a razor on him!” Baird flies out of history, but only for a while. The future is coming, faster by the day. The future is here.

But still there is no escape from what was. High over Barrow-in-Furness looms the Giant’s Grave, two standing stones raised five thousand years ago in the shadow of the brooding Black Combe Hill. Now, this is a place of legend, of giants in the earth, and ghosts seen on moonlit nights. But the men who set those stones were the first men of science, mapping the stars and creating a network of old straight paths, leys, marked by these stones, by age-old religious sites, and wells, and cairns.

Ley comes from an old English word meaning fire. Paths of flickering blue flame, traversing the land, crossing time, reaching into the imagination, linking us to the home of the gods, to dreams, creating patterns and structures that envelop everything. We learn this as we walk them, as we rise above them and look down upon the weft and weave of life. Look: there is Nigel Kneale aged six, leaving Barrow with his family, in the past, in the eternal now, inadvertently following one of those leys, across the sea, west to where the dead go, west to the Isle of Man, the old Kneale home. It is 1928, and Frederick Griffith has just discovered the proof that DNA is genetic code material.

The Isle of Man, in the Irish Sea midway between Britain and Ireland, still holds tight to the passing age. It is a place of stories. At the other end of that ley lies the Meayll Circle of standing stones, where the sound of a tolling bell rings out on lonely nights and travellers mysteriously lose their way. On the Castletown Road out of Douglas, where the Kneale family is moving, young Nigel crosses the Fairy Bridge. It is the home of the Mooinjer Veggey, the Manx term for the little people. Never call them fairies. Never speak their name. The Mooinjer Veggey are mischievous, spiteful. Around two feet tall, they look like mortals. They wear red caps and green jackets and often ride horses followed by packs of little hounds. Like the wild hunt of the mainland, the wish-hounds hunt souls. The Mooinjer Veggey are Manx, but they have counterparts everywhere in the mainland. You cannot escape them. Nigel greets them as all who cross the Fairy Bridge must greet the Mooinjer Veggey, with Laa Mie – Good day – or risk bad luck. Before the annual TT races, which have claimed many a life, the motorcyclists visit the bridge to make a plea for good luck, like ancient pilgrims.

Nigel Kneale writes stories, by day, while his father is editing The Herald newspaper in Douglas, and by night, by candlelight. He hears stories too, everywhere. The doors open, bringing things in. The demonic black dog that stalks Peel Castle. Gef, the talking mongoose, which haunts a mountain farmhouse. On the eve of May Day, Walpurgis Night, Nigel’s neighbours fix a wooden cross bound with sheep wool on the inside of their doors. It will ward off the Mooinjer Veggey. And on Peel Hill that same night, horns blow to banish evil spirits. The old world stays and stays.

In his home, Nigel understands the darkness. Since childhood, he has suffered from photophobia, an intolerance to light. Imagine: to sit on sunlit days, when the light dapples the grass beneath the trees in the garden, and yet you seek out only shadows for comfort. Sunglasses in the day, the world darkens around you. Turn inwards, where the light does not hurt. Turn to the stories that burn brighter than anything. Nigel writes.

At school, he is apart, as all boys who read are apart, but more so. The photophobia draws him away, draws him in. After St Ninian’s High School in Douglas, he seeks solace in books and a small world, an office. The law seems a solid profession, ordering a world that cannot be ordered, through a precise arrangement of words and ideas. Kneale is an advocate at the Manx bar. But the order he prefers to impose comes from his own mind, his own ideas, his own words. This is not a profession for a man who opens doors to ghosts.

Peer down, now, on 1938. Ignore the distant tramp of boots, the harsh voices in the night, and watch the new world begin to take shape as it emerges from the dark. Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman have discovered nuclear fission of heavy elements. The hiss of science begins to match the chant of prayer and spell. In his small office, Nigel is bored. When war breaks out, he tries to enlist in the army. But a man who shies away from the light is no use to them.

The fighting makes the world too big a place. Through the headlines, barely-recognised locales become as familiar as the fields outside Douglas. A small island tossed by storms in the Irish Sea is claustrophobic, even with leys radiating out across the globe, into the deep past, into the imagination. When Kneale broadcasts a reading of his short story Tomato Cain on the BBC’s North of England Home Service, it opens a door for him too, and he darts through it, to a new home, and a bigger world.

London is “an enormous anthology of possibilities”, Iain Sinclair says. Stories are the city’s bones. They thrum through its arteries. They join then and now, day-city and night-city, science and superstition. Though the stories abide, Kneale finds a city trapped in the post-war stasis, like the rest of the UK. Beige light, ration book hunger and near-horizons. Rubble and bomb craters and the fading strains of Glenn Miller, who himself has been cut adrift from time and space. There are no dreamers here, only sharp elbows, only gutter eyes. The nation needs strong arms to rebuild, strong hearts. But that is the least of it, though it does not yet know it. Britain needs a clearly-imagined future, one filled with hope, possibilities, but it also needs to remember who it was and from where it came.

Here, Kneale can tap into the deep past, where the stories are formed, and use those bones to help shape his view into days yet to come. Beneath the streets, lies Londinium where Boudicca led the Iceni to crush their oppressors. Londinium, burned to the ground, only to rise again. Here, the world turns. Here, Brutus of Troy defeated the giants Gog and Magog a thousand years before the Christian era and founded New Troy, Caer Troia. Here, King Lud ruled, and here, too, the Trinovantes tribe renamed the town Caer Ludein. These are all stories. Historians know nothing of these things. And so they are more potent than facts. London is founded on stories. The ghosts were let through a long time ago.

London is the most haunted capital city in the world, filled with old ghosts, and new. As Kneale begins to study acting at the Royal Academy of the Dramatic Arts, an underground worker finishes some paperwork at Bethnal Green Station. All his colleagues have gone, the last train has left. In the lonely silence, he hears children sobbing. Then women’s voices, and screams, and panicked cries. The station is empty, and he runs into the night. During the blitz, sixty-two children and eighty-four women suffocated there while they were sheltering from German bombs. The screams are heard again and again, and are still heard.

All around, the future is coalescing, part-myth, part-mundane, as all times are. It is 1947 and Kenneth Arnold sees nine flying saucer aircraft over the Cascade Mountains in Washington State. Two weeks later, Roswell shudders. It is 1948. Richard Feynman forms an idea of a new reality and quantum electrodynamics emerges into the light. Later, Feynman takes LSD, marijuana and ketamine and floats in sensory deprivation tanks to understand consciousness. He wonders if he can somehow reach the deep unconscious, beyond the mind that he knows.

Kneale graduates from RADA and takes an appointment as a professional actor in Stratford upon Avon. Heading north out of London to his new place of work, he passes the Rollright Stones, a three thousand five hundred year old stone circle where many leys converge. Once these pitted stones were alive, a king and his army marching across the Cotswolds, so the stories tell. The monarch met a witch, who said, “Seven long strides, thou shalt take, and if Long Compton thou canst see, king of England thou shalt be.” Though the king marched forward, on his seventh stride, the ground rose up in a long mound, hiding any sight of the village ahead. The witch turned them all to stone, with the king overlooking Long Compton, his men standing in a circle not far away, and five knights whispering treachery further off. They stand there to this day.

‘Ley line’ came into common usage in 1921, one year before Nigel Kneale starts his journey. The historian Alfred Watkins reads a paper to the Woolhope Club in Herefordshire, expounding his theory about ‘the old straight track’ – prehistoric trading routes based on straight lines between sighting points, standing stones, religious sites, barrows, wells.

Dragon Lines, they are sometimes called, mythological beasts, real and unreal and symbolic. For centuries, it was believed that there was a power in the land beneath these routes and that strange things happened on them. Others call them death roads and spirit paths, to mark the route taken by funerary parties to bury the dead. And the path the soul takes when it journeys back. Ghosts walk these roads.

The Incas had these lines too. So did the Egyptians, and the nomadic tribes of North Africa. In Australia, the aboriginal people walk the lines they call turingas to keep the world alive. Formed by the creative gods, the paths connect the waking world with the dream-time, the source of everything. For those who understand the secrets, messages can be communicated along them over great distance, and at certain times of the year, energies flow through them to bring the countryside alive. All stories come from the dream-time, even this one.

There is no escape from ghosts. In Nigel Kneale’s new home, the Stratford Ripper haunts the White Lion inn, and a dead pilot from the war wanders into the Dirty Duck pub for yet another last drink. Stories are published, a collection of them, and Kneale begins to understand who he is and what he must do. He sees the world around him, still drained of blood by the teeth of the war. He senses a need throbbing in the chests of the men and women at the Lyons tea shop. His publishers tell him, write a novel, people like novels. But Kneale likes the cinema and its flickering spectral lights. Human faces reveal stories better than words, he says. He wants to write television. In book-lined offices, faces crumple in horror. He does not tell his publishers that he has never seen any television.

But first: radio drama, a story that formed on the Isle of Man, a story that was real, that was in his head, a mining disaster. And then he knows he can do this thing, and he should be doing it, and he signs a contract to be one of the first staff writers for BBC Television. He learns the basics, one foot in front of the other. Adaptations of books and stage plays, scripts for light entertainment, children’s shows. Sharpening the words, understanding how to open doors.

Years later, Princeton University physicist Dean Radin examines a mountain of date published in scientific journals and says, “Reality built out of imagination, which in turn is a manifestation of a primordial ‘substance’ that is both mind and matter? It sounds like science fiction. But there is evidence that this may be so, and if true, it might explain a number of persistent puzzles, from legends of the siddhis, to psi in life and the laboratory, and even, as unlikely as it may seem, to ‘unidentified flying objects’.”

It is 1951. High in the Himalayas, the air carves into the lungs and Eric Shipton takes a photo of a footprint in the snow. It is massively bigger than any human footprint. The photo travels around the world. People think, we live in a strange place. Is it real, this Abominable Snowman? Is it just a story?

It is1952. In the New Forest, in Hampshire, John and Christine Swain are driving through the back lanes with their two sons. They chance upon a lake swathed with mist, not far from Beaulieu Abbey. In the middle of the lake, there is a rock with a sword embedded in it. Awed, the family whisper about the legend of King Arthur. A memorial to him, they say, it must be. Once every three weeks, for the next seventeen years, the Swains drive from their home in Somerset to the New Forest to find the lake, and the stone, and the sword again. They never do. It is not there.

Now, here in 1952, it is time. Kneale has work to do. Writer’s work. This world he sees is threadbare and dreary, still clinging on to the deprivations and spiritual destruction of the war. There is not enough humanity. But beneath the surface, other worlds exist, truer worlds, he knows this to be true. We all do. Kneale creates a character with one foot in the past but a gaze turned high, and to the future. In this story, Professor Bernard Quatermass of the British Experimental Rocket Group supervises the first manned flight into space. BERG is informed by the peculiarly-British sensibilities of the civil service and government ministries, and of how public service by committed individuals of the kind that worked so well in the war years could lead to a new common good. The design of its rockets harks back to those sleek machines of the future that slipped from their moorings beneath the black waves off Barrow-in-Furness.

Professor Quatermass, though, is something different, something new. He is a dreamer and a man who sees hope for humanity by shackling science to that common good. He looks up and out, always. Through Quatermass, Kneale believes, the public will find an antidote to the benighted years of the recent past in this new vista that science is rapidly opening up. Quatermass can conquer the fear within us that is the legacy of that dark, superstitious past.

It is one year later, as the six-part BBC series airs in a sweltering summer, and a huge proportion of the TV viewing audience tunes in at some point across the run. The Quatermass Experiment is a success. But its prescient underlying message that new threats to Britain’s security will come with this new openness is already finding an echo in the wider world. The public is struggling to comprehend the ramifications of President Truman’s announcement that the hydrogen bomb has been developed. As Quatermass speaks, Russia announces that it, too, has the bomb.

The world is in upheaval now. New myths are emerging. Crick and Watson have already published Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleice Acid. Aldous Huxley is hard at work opening The Doors of Perception after trying hallucinogens. The spirit of exploration that Kneale tapped into continues, out into the universe, into the very fabric of existence, into the architecture of the mind.

Kneale is not blind to the threats that lie in the future. He writes an adaptation of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four which cements his reputation. And when he turns his attention once again to the British Experimental Rocket Group in Quatermass II, one of the themes is a conspiracy corrupting the political establishment.

New myths, and old. Kneale has seen Eric Shipton’s photo taken high in the Himalayas, and writes his teleplay, The Creature, about the Abominable Snowman. It is a seemingly simple story about a monster, yet one which is infused with both a belief that the universe offers hope, and a fear that humanity will never claw its way out of its self-destructive state. Afterwards, Kneale wants freedom for himself. He does not seek renewal of his BBC contract, stating, “Five years in that hut was as much as any sane person could stand.”

Set free, Kneale begins writing what many, including the BBC itself, consider his greatest work, and one of the best works of TV drama. Quatermass and the Pit is also the point where Kneale forges perhaps his most powerful idea. He remembers that fairy bridge on the Isle of Man, those stone circles with their millennia-old legends. He understands how myth has shaped every aspect of human development, but he also understands people. They see strange things, lights in the sky, footprints in the snow, shadows with no source. But they are not liars. They are not fools.

The world seems caught between a misty shape in the shadowed ruins of an old church and the ghostly blips on a radar screen, each summoning their own form of existential dread. Perhaps there are demons, perhaps there are Martians, perhaps we are both of them. Everything is connected, lines running through the world, through space, through history, through the human mind.

It is 1957. Analytical psychologist Carl Jung publishes Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Sky. He explores the theme of myth manifesting as real and suggests that experiences of angels, aliens, fairies, sprites, elves and demons, all may be psychophysical, a blurring of conventional boundaries between objective and subjective realities. The imaginal and the real are not as separate as they seem. It is 1957, and Kneale starts to write this new story, Quatermass and the Pit, developing his life’s philosophy – that science underpins the strange. We do not throw away all those centuries of accumulated experiences of the bizarre, we do not dismiss the people who claim these things. We understand them in the fierce light of this new world.

And in Quatermass and the Pit, everything is connected. Not only scientific exploration and age-old legends, but also the world that is unfolding all around, the racial tensions that had been building across the decade, the cloying bureaucracy that still lingered after the war, the politics as the military tries to lay claim to the British Experimental Rocket Group in this developing Cold War.

It is 1960. Near Otterburn in Northumberland, at the site of a fourteenth century battlefield, the engine of a taxi dies. As silence falls on the lanes, the driver and passengers see a phantom army marching towards them. As the soldiers close on the car, they fade away.

It is 1961. There are aliens, we know that now. Betty and Barney Hill told us. In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a reporter interviews them about how they were abducted by beings from another world as they drove home from a vacation in Niagara Falls. They are taken aboard a flying saucer, they say. Ten days later, Betty starts to experience vivid dreams of small men with dark eyes and grey skin who took them away. They look like the fairies of the Isle of Man, and act like them too.

Kneale has already imagined the future, and found the lines that join it to the past. For the sixties, he takes a long holiday, adapting plays and novels for the cinema. He earns a BAFTA nomination. He has a comfortable family life, a wife Judith Kerr, children Matthew and Tacy.

It is 1964. Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson provide experimental evidence of the Big Bang. Now we start to understand how the biggest story of all was created. It is 1967 and Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish discover the first pulsar. In the Cairo suburb of Zaitoun, at the same time, crowds witness the first of many visions of the Virgin Mary appearing over the Coptic Church.

Yet the Britain of the 1970s seems to be going backwards. After the collapsing boundaries of the sixties, the white heat of technology, the rushing torrent of optimism and change, all that is left is the mud-flats of political strife, ugly fashions, collapsing economies and corruption. “Without You’ by Nilsson is on the radio, the soundtrack of loss. So is Take Me Back’Ome by Slade, and Alice Cooper’s rebellious School’s Out. History seems to be ending. The future has been stolen, and Britain is haunted by the ghosts of those promises made only a few years ago.

It is 1972. After a grey autumn, Britain lumbers into a cold December. The air reeks of coal fires, everywhere. Saturdays are long treks home from the football, through dark terraced streets throbbing with the threat of violence. Bovril, flat caps on old men, piss beer and nicotine-stained fingers. Somewhere a government ad-man is conjuring up a campaign to terrify children with a public information film, The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water. The hooded figure of Death stalks kids at play near a lake. It is thought that this ad is a good idea.

Christmas Day, and children awake and rush to the tree to tear cheap paper off Action Man and Sindy, Space Hoppers and roller skates. Their parents think it is a good idea to let them stay up to watch some festive BBC programming, The Stone Tape by Nigel Kneale. There are a lot of nightmares in the seventies.

The Stone Tape is a nerve-jangling ghost story that is the purest evocation of Kneale’s evolving philosophy. The tradition was old – a ghost story for Christmas, another example of the writer drawing on the past and finding its relevance to the modern. In the story, an electronics company research team descends on a haunted mansion. Science collides with the supernatural as the team starts to realize that stone is a recording medium for moments of heightened emotion. Ghosts are no more than a replaying of what has been, preserved forever in the environment. Old stories flickering into life again and again and again.

The production is a masterpiece. Kneale’s tale reaches out across the years, influencing new generations of writers. It reaches out across the world, too. In America, the horror director John Carpenter sees it and dreams up his film, Prince of Darkness.

Kneale has had his fill of the BBC. The corporation has rejected several of his scripts and plans for a new Quatermass serial. But he still has much to say about the confluence of myth and science, and how those dark supernatural beliefs still shape the modern mind. He moves to ITV and writes Beasts, where horrors that would have been at home in medieval times find a new place in the kitchen sink seventies.

ITV also produces Kneale’s final Quatermass story, one centred on the megalithic sites that surrounded his childhood homes. It is loaded with the writer’s distaste for the hippie movement and the occult beliefs they had made common currency, perhaps even a dislike for young people in general. Nigel Kneale has no truck with ley lines. Woolly-headed New Age thinking sets his blood pumping. His Neolithic standing stones are not nodes of earth energy, but markers for beacons left by an alien force. The four-part serial is not critically well-received.

Kneale does not see himself as a science fiction writer, he tells people. He does not really seem to enjoy the genre. He has nurtured a loathing for Doctor Who. “It sounded a terrible idea and I still think it was,” he says. “The fact that it’s lasted a long time and has a steady audience doesn’t mean much. So has Crossroads, and that’s a stinker.” It is the tail end of the twentieth century and Kneale is asked to write an episode of The X-Files. He turns it down. No one is surprised. He has a lot of anger in him, Nigel Kneale. He does not seem to like the light very much. He simmers and carps and pokes sticks. So what? No one wants a writer to be their friend. They want them to see things that no one else can see.

Jeffrey Kripal, professor at Rice University, says the mystical, the paranormal, the supernatural may be thought of as symbols that illustrate “the irruption of meaning in the physical world via the radical collapse of the subject-object structure itself. They are not simply physical events. They are also meaning events.” Writers know everything.

Writers know nothing. J R R Tolkien thought The Lord of the Rings was not a reflection of the Great War. J R R Tolkien thought he was writing from a Christian perspective while creating a sprawling, powerful evocation of the pagan greenwood. Writers know their conscious mind, which is next to nothing. Stories are made in the unconscious mind, where the ghosts live. They come through doors, unbidden. No one knows the unconscious mind, what works are done there. Not even writers.

It is 1993 and Jacques Derrida is finishing his work, Spectres of Marx, in which he discusses an idea within the philosophy of history. Hauntology is “the paradoxical state of the spectre, which is neither being nor non-being.” Derrida is intrigued by this idea, which suggests that the present exists only with respect to the past, and that society will eventually begin to form itself around the “ghost of the past”, or, seen in another light, the ghost of imagined futures that never materialized. In his book of essays, Ghosts of my Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Mark Fisher says hauntology is a “refusal to give up on the desire for the future”.

Nigel Kneale never did give up on that desire, and his visions still haunt the world of today. We dream of the British Experimental Rocket Group that we never got, and the aesthetic design sensibility of his sleek 1950s-finned vessels. We yearn for the wide-eyed sense of hope that we need to be looking ‘out there’. Nigel Kneale captured an idealized view of what could have been, should have been but never was. But he also delineated a darkness that itself haunted the human condition, one that was perhaps always self-inflicted and which would prevent us reaching those great heights he imagined. Hauntology, the first new critical theory of the twenty-first century, exists in this tension between two poles.

The past and the future. Science and the supernatural. Myth and the mundane.

Kneale may not have known his own deep mind, but he mapped Britain’s unconscious at a time in our history when all sorts of lines were blurring. He understood, instinctively perhaps, how everything was connected, and by doing so, he started to sketch out new myths that owed everything to what had gone before, but were relevant to the way we live our lives now.

It is 2015 and Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Bradford Skow publishes his book, Objective Becoming. Skow talks about the Block Universe theory, and that all time exists simultaneously. Rise above it, look down, he says, and you will see what was, what is, what will be, all happening in an ever-present instant. It is 2006 and Nigel Kneale is gone. And it is now, always now, and there is Nigel Kneale, striding across the land, across time, from the real world in to dreams, into the world of ghosts, shaking his fists, flickering with blue fire.

“If the evolution of knowledge in this century exceeds that of the last, which seems likely, then we can look forward to a future that’s likely to redefine our concepts of reality far beyond any of the stranger concepts we’ve encountered so far.” ~ physicist, Dr Dean Radin

June 29, 2024

Bluesky – Join The Conversation

For anyone looking to get involved in the conversation on Bluesky, here’s my starter pack to get you set up with friends to populate your feed.

writing and creativity, art, news, politics, foreign affairs all leavened with snarky humour.May 7, 2024

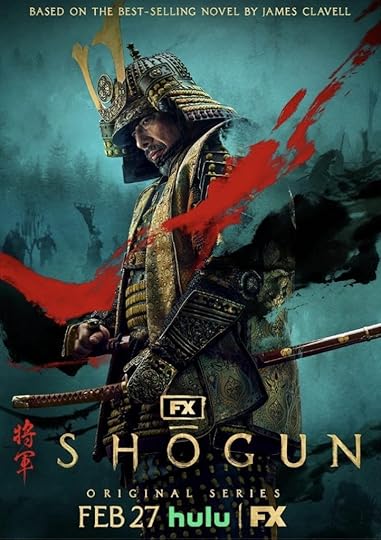

Shogun

Only two episodes in and Shogun is already one of the best things I’ve seen in a long time.

An adaptation of James Clavell’s best-selling novel, it’s rich, meaty, measured, with a lush production design and first-rate scripts and direction,

It tells the tale of John Blackthorne, an English sailor who rolls up in feudal Japan on a secret mission and instantly plunges into the culture clash between East and West.

The political chicanery and treachery are interspersed with astonishing set pieces that have you on the edge of your seat.

And the acting by a predominantly Japanese cast is excellent. Disney obviously spent a lot of money on this and it shows.

Lots of good lines, but I enjoyed: “Two baths in one week? Do you want me to catch the flux?”

March 21, 2024

3 Body Problem

Thoroughly enjoyed the first episode of Netflix’s 3 Body Problem.

I have a feeling this one is going to be massively divisive. Fans of the original novels will probably be furious it steps away from the books’ cold abstraction to attempt a more human connection, something that is absolutely necessary to reach the broader audience required for a TV adaptation.

But those coming expecting Netflix’s own Game of Thrones via the rep of showrunners Benniof and Weiss will also be disappointed because it brings from the books the need for an at least rudimentary understanding of science, scientific terms, even the Cultural Revolution. The pacing is also glacial.

And unlike GoT you don’t get any tits and knobs to break up the exposition.

But somewhere in the great Venn diagram there’s a little segment which appreciates the changes made and that’s where I slot in.

The vastness of the universe, mysterious countdowns, the fifth generation of Apple’s Vision Pro, puzzles and conundrums and a climate crisis analogy coupled with some solid history rarely seen in the West made for an intriguing watch.

I also saw someone complaining that all the key scientists were good-looking which is Nerd-Rage at its finest.

January 21, 2024

Running For Creativity

I’m a runner. Nothing extreme or competitive. No marathons. But I do about 7km a day, most days, and have done since I was at university.

Over the years I’ve found it’s the greatest source of creativity – many ideas have come to me while I’ve been out in the greenery. It’s also deeply meditative, cleaning out the detritus of daily life.

Which brings me to the Tendai Buddhist monks in the mountains of Japan. In a practice started 1200 years ago, they run the Kaihogyo, a seven year ultramarathon which they see as the path to enlightenment.

During that time, a monk must run:

*25 miles a day for 100 days for the first three years

25 miles a day for 200 days for years four and five37 miles a day for 100 days in year six52 miles a day for 100 days, then 25 miles a day for 100 days in the final yearThat takes them a distance greater than the earth’s circumference and they do it in sandals made from woven rope.

Just in case you were looking for a new fitness challenge.

Jack of Ravens

- Mark Chadbourn's profile

- 220 followers