Peter Vronsky's Blog

January 9, 2019

FINDING A SERIAL KILLER’S SECRET LAIR FROM THE 1970s

[image error]I had one of strangest experiences ever in New York this week as convicted serial killer Richard Cottingham, the “Times Square Torso Killer” guided me along its streets from his cell in Trenton via the Department of Corrections-approved app JPAY. It wasn’t instant because JPAY/DOC reviews all the communications, but it was relatively interactive. I could send him pictures from the street, also subject to the same review.

He described the location of the “secret” apartment he kept in New York in the 1970s while living in New Jersey with his wife and three children. He said it was a super dirt-cheap tenement house “directly across First Avenue from the United Nations Headquarters.” I first thought, “Bullshit, even in the 1970s that would have been valuable high-rent space. But no way today would it still be around!”

But what ya’ know! Directly across First Avenue from the United Nations Headquarters today is this rotting tooth of a five story apartment house, just as he described it, still there, all fucked up and frozen in time from the 1970s, like one those woolly Mammoth Mastodons they find encased in Siberian glacial ice – a creep hole of a place, stuck in a dark time tunnel – a serial killer’s secret lair – where the Times Square Torso Killer rested and recuperated, where he kept his stuff, his straps and gags, where he drank and dreamt, from where he sallied into the streets and bars to bring back his roofied nighttime catch, to do with anything he wanted, to torture, to keep or kill.

December 20, 2017

The True Story of Elizabeth Báthory “The Blood Countess”

Abridged from Female Serial Killers: How and Why Women Become Monsters by Peter Vronsky.

Transylvanian Countess Elizabeth Báthory “The Blood Countess” (1560-1614) is often described as the first atypical and very rare, pathological hedonist lust female serial killer, as opposed to the more typical profit-motivated “black widows” or “poisoner care-giver” female serial killers. Her victims were not her political rivals or intimates but innocent peasant girls employed in her service or daughters from minor declining aristocratic families put in her charge.

At the center of the Báthory story and her nickname “Blood Countess” were allegations that she bathed in the blood of virgin girls in a deluded belief that it nourished the beauty of her aging skin. She was accused of having killed as many as 650 girls—many tortured to death in the most savage and cruel manner before being drained of their blood for the Countess to bath in.

Early Life

Elizabeth was born in 1560 in Hungary into the Transylvanian branch of the powerful and wealthy Báthory family which dominated the eastern regions of the Holy Roman Empire (today Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia, Austria, Romania, Germany and Poland.

Surviving portraits of Countess Elizabeth in her youth show a beautiful woman with her hair pulled back from a high intelligent looking forehead, smoky almond shaped eyes and sensually pouting lips. Yet there is a cruel curve to her mouth and her face exudes a sullen petulance that betrays an underlying rage.

[image error]Elizabeth Báthory the “Blood Countess” circa. 1580

She was married by arrangement at the age of fifteen in 1575 to a wealthy Hungarian Count, Ferenc Nadasdy, five years her elder. The marriage was a happy match. The “power couple” lorded over a vast network of castles, country manor houses and palaces in Prague and Vienna and other cities. At their country estates and inside the walls of their castles they had life and death power over their servants and peasants. Elizabeth was often left alone in charge as her husband was away for years at a time fighting the Turks in the south, where he developed a distinguished reputation as a fierce warrior until his death in 1604 from disease.

[image error]Traditional Portrait of Elizabeth Báthory as a young woman.

According to the story, beginning as an adolescent, Elizabeth used her power to torture to death in the most horrific and sadistic ways her servants, mostly peasant girls; burning their genitals with a candle; biting them to death; ripping their mouths open with her own hands; burning them with heated metal rods and rivets; beating them with whips, clubs or iron bars; cutting and stabbing; throwing them naked into the snow and pouring freezing water over them; pouring boiled water on them and tearing away their skin; hauling them up in suspended barrels spiked inside and rocking and rolling them while showering and bathing in their blood below; or closing them in spiked Iron Maidens like in a garlic press to extract their blood.

[image error]Batory by Hungarian artist István Csók – circa 1893

It was alleged that as many as 650 girls and young women were murdered over a thirty-five year period—and at least between 37 and 51 in the last decade before Elizabeth’s arrest in 1610 at the age of fifty, when she started killing not only peasant girls, but girls of noble birth as well. This is said to have led to her downfall.

In the wake of multiple complaints and accusations, when her castle was raided by authorities during the Christmas holidays of 1610, it was reported that mutilated corpses of girls were found strewn in the courtyard and in the basement of the tower. When the arresting party burst into her chambers, according to legend, she was found sitting on a stool chewing on the mutilated dying body of a girl prostrate before her. The Hungarian authorities ordered that Elizabeth be walled-in for the rest of her life in a castle apartment with only a small open port for food. After four years she died at the age of fifty-four still preserving her legendary cruel beauty.

The true story of Elizabeth Báthory, however, is slightly more complicated, but horrific nonetheless in its details.

The Back Story

We actually came very close to never having heard of Elizabeth Báthory because her trial was held in secret in a remote Slovakian town in 1611 and her powerful family immediately sealed its records. There were no newspapers, pamphlets or broadsides to report on it. None of the ruling families wanted the details of the horrendous charges against their relative released to public scrutiny—nor did they want Elizabeth’s estates confiscated by the crown or the crown’s debts to her family cancelled. Elizabeth was not even allowed to appear at the trial and instead of a public execution, she was walled-in alive, in a room in one of her remote castles. Her servants and accomplices took her place on the executioner’s block while the Countess herself survived in anonymity in her bricked-in apartment until the summer of 1614 when she was discovered dead on the floor.

While her family greedily divided up Elizabeth’s property among themselves after her death, the details of her crimes and trial vanished from the public record. The indictments, trial transcripts and judgments were hidden away in closed archives. Her name was forgotten. Only legends and folktales of a blood-drinking female vampire circulated in the Transylvanian mountains until they were picked up two centuries later by authors like Bram Stoker and given a new life in the form of Dracula—inspired by another Transylvanian despot—Vlad “The Impaler” Tepes—Dracul. (To whose ancestors Elizabeth was actually remotely related through marriage.)

Elizabeth Báthory would have remained merely an anonymous monster had not a Jesuit scholar, Father Laszlo Turoczy, discovered in 1720 the trial records, about one hundred years after her death. Turoczy restored the legendary female vampire to human form with a name, identity, a history and detailed descriptions of her crimes in an ecclesiastical book published only in Latin. (Laszlo Turoczy, Ungaria suis cum regibus compendio data, Nagyszombat: 1729.)

The blood bathing myth

In 1796, Michael Wagener, in a book entitled Anthropological Philosophy, was the first to widely publicize the story of Elizabeth’s alleged bathing in blood as a skin-care obsession, stating that after a chambermaid noted some hairs out of place in Elizabeth’s coiffure, the Countess struck her so hard on the ear that the girl’s nose spurted blood into Elizabeth’s face. When Elizabeth wiped the blood away from her face, according to Wagener, she discovered that her skin seemed rejuvenated. From then on she would bathe her entire body in fresh blood and had some 650 girls murdered for this purpose, Wagener claimed. (Michael Wagener, Beiträge zur Philosophischen Anthropologie (Articles on Philosophical Anthropology) Vienna: 1796.)

[image error]

The problem is that when one reads all the other literature on Báthory, the blood bathing story morphs into different versions, the most common of which states that Elizabeth’s handmaiden was struck because she pulled a few strands of the Countess’s hair while combing it, resulting in her being struck directly in the face and blood from her nose spurted onto the Countess’s hand, who saw her skin become more translucent and young after wiping it away. Moreover, the girls had to be virgins or of aristocratic origins before Elizabeth would believe in the renewing power of bathing in their blood. Something was not quite right with the story.

Nor were the bio-mechanics of bathing in blood adequately explained considering the tendency of liquid blood to rapidly coagulate into a chucky-sticky matter not exactly suitable for bathing.

Rediscovering the Blood Countess

It was not until the 1970s that Boston College Professor and Fulbright scholar Raymond T. McNally, along with his colleague Radu Florescu, established rare access to Hungarian and Romanian archives (then still behind the Iron Curtain) that led to their hugely popular book, In Search of Dracula, a history of the Transylvanian prince Vlad Tepes, nicknamed Dracul (“Devil” or “Dragon”)—the historical figure who inspired a Bran Stoker’s decision to name his fictional vampire “Dracula” and situate him in a Transylvanian castle.

In the wake of the success of In Search of Dracula, McNally returned to the archives in Transylvania and discovered an abundance of original documents from the trial of Elizabeth Báthory.( Raymond T. McNally, Dracula Was A Woman: In Search of The Blood Countess of Transylvania, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983.)

[image error]

It was not until 1983, that we began to get a more accurate glimpse of what crimes the Blood Countess was actually charged with, and the blood bathing became the first myth to fall. Nowhere in the trial record was there any mention of bathing in blood. It was local gossip and folklore picked up by writers in the 18th century and injected into the sordid history. But still, the likely explanation for how this myth took root bodes darkly for what Elizabeth was really into: she was thought to have bathed in blood because she was so covered in it after torturing her victims, it appeared as if she had bathed in it.

Her arrest

Denunciations and complaints of girls going missing in Elizabeth’s employ had been coming in to the Royal authorities for decades. Numerous parents who had sent their daughters to work at Elizabeth’s castles lodged official complaints that the Countess unsatisfactorily explained their daughters’ disappearances. While reports of the cruel torture deaths of peasant girls in Elizabeth’s employ circulated for years, nobody was overly-concerned. Disciplining one’s servants to death was in the 1600s was perceived as excessively cruel and ‘impolite’ but nonetheless it remained an aristocrat’s prerogative should they choose to do so. But now reports began to filter in from other aristocratic families, about their daughters’ disappearances while in the care of Elizabeth Báthory. These could not be ignored as easily.

[image error]Julie Delpy as Bathory in the 2009 French-German film The Countess

The year before her arrest, some twenty-five young women from declining minor noble families were invited to stay at Elizabeth’s castle. Some of these minor aristocratic families were happy to send their daughters to Elizabeth, hoping somehow to raise the prestige of their family through an association with the Countess. But during their stay, several of the girls vanished. When concerned parents began to inquire into the fates of their daughters, the Countess reported that one of the other girls had murdered the girls for their jewels and committed suicide. When her family demanded that the body of the girl be returned, Elizabeth refused, stating a suicide fatality had to be immediately buried unmarked on unconsecrated ground. She explained other multiple deaths as being caused by outbreaks of disease, and citing the fear of an epidemic panic as the reason for secretly burying those victims.

The final events that precipitated Elizabeth’s arrest in 1610 began when a Lutheran Reverend Janos Ponikenusz was assigned to take charge of a church in the Slovakian village of Cachtice (Cséjthe), where the widowed Elizabeth lorded in a castle overlooking the village below. Reverend Janos was sent to replace the previous pastor who had recently died. On his journey, just like in a horror movie, the closer he came to Cachtice, the more Janos began to hear peasants’ mutterings of vampires and mutilations of young women in the town and guarded warnings of evil deeds in the castle.

According to the legend, Janos investigated the reports of murdered girls, carefully collected evidence and eventually denounced the Countess to his church superiors who finally called in the civil authorities.

In the 1970s, Professor McNally discovered a letter in the Hungarian archives from Janos to his superior describing how she Elizabeth the night before sent six invisible black cats and dogs to attack him in his home in the middle of the night. As he beat back the attack, screaming, “You devils go to hell”, none of his servants could observe any of the animals. “As you can see,” Janos wrote, “this was the doing of the devil.” (McNally, p. 66.)

While complaints from peasant families were largely ignored, the reports of missing girls of noble birth were investigated by the Hungarian parliament, situated in Bratislava at that time (the capital Budapest was under Turkish occupation). Throughout 1610 the parliament’s investigators had been gathering depositions against the Countess from numerous witnesses of both noble and common rank.

On December 27, 1610, spurred forward by urgent reports from Reverend Janos and news that four corpses of young women were recently dumped over the castle wall in full view of the village, the parliament ordered Elizabeth’s superior (and relative through marriage) Prince George Thurzo to ride to Cachtice and raid Elizabeth’s castle and manor house and arrest the Countess.

It was the Christmas season and the Countess was celebrating the holiday in her manor house in the town when on the evening of December 29 one of her servants, a young girl named Doricza from the Croatian town of Rednek, was discovered stealing a pear. Enraged, Elizabeth ordered that the girl be taken to the laundry room, stripped naked and tied. Elizabeth and her female servants took turns attempting to beat Doricza to death with a club. Elizabeth was reported to be so soaked in blood that she had to change her clothes. Doricza was a strong girl and did not die in the beating. It was getting late into the night when Elizabeth tired of beating the girl and had one of female servants finally stab Doricza to death with a pair of scissors. The girl’s corpse was dragged out and left by a doorway in courtyard for disposal the next morning. At almost exactly that same moment, after traveling two days from Bratislava, Prince Thurzo’s raiding party arrived at the house and ordered the servants to stand aside. As the party burst into the courtyard they immediately came upon the bloody, battered, and still warm body of the murdered girl. A search of the premises revealed the body of two more brutally murdered girls in the manor house. Reportedly, a further search of the castle on the hill revealed numerous decaying bodies hidden at the bottom of the tower, which Reverend Janos had earlier refused to bury.

Elizabeth Báthory was detained in her castle at Cachtice, but four of her servants—three elderly females and a young manservant—were taken away by Thurzo to his seat of power in the nearby larger Slovakian town of Bytca and there they were questioned and charged for their complicity in the murders. Here the story of Elizabeth Báthory’s trial becomes conspiratorial.

[image error]Elizabeth Batory’s torture castle in Cachtice, present-day Slovakia. After her trial, the Blood Countess will end up being walled up in the castle for the remainder of her life.

Prince Thurzo and Elizabeth Báthory’s trial

Prince Thurzo was related by marriage to Báthory’s powerful family who were all aware of the deliberations taking place in parliament. (As was Elizabeth, who believed she was beyond the reach of the law.) Aside from their reputation, much was at stake for the family if Elizabeth ended up being convicted for murder or witchcraft—which the rumors of the blood bathing suggested. Elizabeth’s wealth and properties would have been seized by the Hungarian crown if she was to be put to death under those circumstances.

Moreover, the Hungarian king had borrowed money from Elizabeth’s husband when he was still living, and as his widow, the debt was still owed to her. If she was executed, the crown debt would be cancelled instead of being paid out to her surviving family members. Prince Thurzo had the title of Lord Palatine—meaning that he had the King’s judicial powers in his regional principality—and it is there that Thurzo would stage the trials in his own jurisdiction in such a way as to ensure that Elizabeth’s property and the debts to her remain payable to all the surviving relatives.

There emerged a vast literature in Hungary, particularly in the heady nationalist periods of the 20th century, suggesting that Elizabeth Báthory was entirely innocent and a victim of a family plot to seize her wealth. Since the discovery of more court transcripts and witness statements, Thurzo’s correspondence and other archival records in the 1970s, the real story of Elizabeth Báthory is now better known.

The news of Elizabeth arrest and charges did not become widely known. A priest’s diary from the period, with detailed descriptions of events, only provides this short matter-of-fact notation: “1610. 29 December. Elizabeth Báthory was put in the tower behind four walls, because in her rage she killed some of her female servants.”

The secret trial began within three days of Báthory’s arrest, at Thurzo’s courts of justice in Bytca on January 2, 1611. All the court officials and jury members owed their allegiance to Prince Thurzo. The plan apparently was to quickly sentence the Countess to life imprisonment (in perpetuis carceribus—“perpetual incarceration”) in a fait accompli while the parliament was on holiday to ensure that her properties are not seized or debt to her cancelled.

While the countess was locked away back in Cachtice, four of her servants were questioned at Bytca, including a session under torture to clear away any loose ends. Using the methodology developed by the Inquisition, which is said to be the first in history to use relational databases in investigative procedure, the same questions were put separately to each prisoner, and then their answers carefully cross-indexed and compared. At the end of the interrogations, the servants were charged as Báthory’s accomplices despite their pleas that they had no choice but to obey the Countesses orders.

The trial testimony

The four servants were put on trial three days later, on January 2 , 1611. Their testimony was entered as evidence against Elizabeth. According to the defendants, the Countess tortured her female servants for the slightest mistake. With her own hands, she tore apart the mouth of one servant girl who had made an error while sewing. Everyday, young servant girls, who had committed some infraction, would be assembled in the basement of the castle for brutal torture. Elizabeth delighted in the torture of the young women and never missed a session.

While torture of one’s servants in seventeenth century Hungary was not a crime, it was by then considered ‘impolite.’ Thus when traveling and visiting other aristocrats, the first thing the Countess would do is to have a private room secured where she could torture her servants in privacy without offending her hosts. It was noted that the girls chosen for “punishment” seemed to be always those with the biggest breasts and they would be stripped naked prior to the torture beginning.

The four accomplices testified:

The Countess stuck needles into the girls; she pinched the girls in the face and in other places, and pierced them under their fingernails. Then she dragged the tortured girls naked out into the snow and had the old women pour cold water over them. She helped them with that until the water froze on the victim, who then died as a result… Her Ladyship beat the girls and murdered them in such a way that her clothes were drenched in blood. She often had to change her shirt…she also had the bloodied stone pavement washed… She had the girls undress stark naked, thrown to the ground, and she began to beat them so hard that one could scoop up the blood from their beds by the handfuls… It also happened that she bit out individual pieces of flesh from the girls with her teeth. She also attacked the girls with knives, and she hit and tortured them generally in many ways…her Ladyship singed the private parts of a girl with a burning candle. One time her Ladyship lay sick and therefore could not beat anyone herself, so a servant was compelled to bring the victims to the Countess’ bed whereupon she would rise up from her pillow and bite pieces of flesh from the girls’ neck, shoulders and breasts.

The girls would be beaten so long that the soles of their feet and the surfaces of their hands bristled. They were beaten so long that each one, without interruption, suffered over five hundred blows from the women accomplices. If the folds of the Countess’ clothing were not smoothed out, or if the fire had not been brought up, or if the outer garments of the Countess were not pressed, the girls responsible were at once tortured to death. It happened that the noses and lips of the girls were burned with a flat-iron by her Ladyship herself or by the old women. The countess also stuck her own fingers into the mouths of the girls and ripped their mouths and tortured them in this way. If the girls had not finished their obligatory sewing chores by ten o’clock at night, they were immediately tortured… Her Ladyship with her own hands had keys heated red-hot and then burned the hands of the girls with them.

[image error]Version of Báthory by István Csók – circa 1893

While at first it was believed that Elizabeth began her killing spree after her husband’s death, witnesses testified that the murders began while her husband was still alive and with his knowledge and participation. This is typical of sadistic female serial killers today who target victims for sexual motive; they are almost always accompanied by a male partner–usually dominant–which the female serial killer partner mimics.

According to the testimony:

At Sarvar during summer his Lordship Count Ferenc Nadasdy had a young girl undressed until stark naked, while his Lordship looked on with his own eyes; the girl was then covered over with honey and made to stand throughout a day and a night [so that she’d be covered in insect bites. She collapsed into unconsciousness.] His Lordship taught the Countess that in such a case one must place pieces of paper dipped in oil between the toes of the girl and set them on fire; even if she was already half dead, she would jump up.

The accused servants who were in the Elizabeth’s service for a period ranging from sixteen to five years, testified that they personally witnessed from a total of thirty-six to as many as “fifty-one, perhaps more” girls killed.

The downfall of the countess

Elizabeth’s mistake was to start killing girls in 1607 from privileged minor aristocratic families. It is unclear exactly why she took this path but possibly because her reputation had spread by word-of-mouth among the peasants and few dared to come into her domestic service. Indeed her last victims were girls recruited from the distant Croatia where nobody had heard of Elizabeth. With aristocratic families she used a different approach, always selecting victims from minor and impoverished noble families, offering their daughters opportunities to raise the status of their families through Elizabeth’s superior status and contacts. But even this theory is cloudy as there was testimony stating that the servants sometimes washed, groomed and tutored peasant girls to behave as noble ladies when presented to the Countess. For some reason Báthory was specifically targeting nobles at that point. That of course led to speculation that she believed only the blood of noble girls would serve the purpose of restoring her skin. Only problem with that theory is that the bathing in blood story does not appear in any of the affidavits or in the testimony at the trial. It might be entirely the stuff of peasant folklore picked up a hundred years later and reproduced in pamphlets and books dealing with Elizabeth.

Elizabeth became brazen and careless towards the end of her killing career. While staying in Vienna, she ordered a renowned choir singer from the Church of Holy Mary, Ilona Harczy, to perform privately for her at her apartments in the city on Augustinian Street. The girl was never seen again and witnesses claimed Elizabeth killed her when she could not sing for her either out of fright or shyness.

As common practice in those days, the trial lasted only for a day. At the end of the trial two female servants were sentenced to have their fingers torn away with hot pincers before being thrown alive into a fire. The male servant, because his youth was to sentenced to decapitation and his body also thrown on the fire. The fourth defendant was acquitted and vanished from the record. A few months later another of Báthory’s female servants was charged, tried and sentenced to death.

The case against Elizabeth Báthory herself was reviewed by a higher court four days later, on January 7, and Prince Thurzo himself testified before some twenty judges and jurors. Unlike the January 3rd lower court trial, the records of which were kept in Hungarian, the high court trial was transcribed in Latin. Thurzo and members of his raiding party described finding the still warm battered corpse of Doricza “ex flagris et torturis miserabiliter extinctam.” Depositions from thirteen witnesses were heard. It is here that a witness identified only as “the maiden Zusanna” testified that a register was discovered in Elizabeth’s chest of drawers listing her victims and that it totaled 650 names. Zusanna testified that in the four years she was in Báthory’s service, she witnessed the murder of eighty girls. The hearing was presided over by the King’s judge, and it purpose appeared to gather sufficient evidence to sentence the Countess to death and confiscate her properties and cancel the crown’s debt to her. Thus the testimony of Zusanna might have been entirely contrived for that purpose. Báthory desperately petitioned the court to make an appearance to defend herself, but her family blocked those attempts. The high court held:

At the very entrance to the manor house they came upon things pertinent to this case. There was a certain virgin named Doricza who had been miserably extirpated by pain and torture, two other girls were found murdered in similar agonizing ways with that very manor house in the town of Cachtice, which was under the control of the widow Nadasdy. His illustrious Highness [Prince Thurzo], witnessing this evident and ferocious tyranny, having caught the bloody, and godless woman, the widow Nadasdy, in flagranti of her crime, placed her under immediate perpetual imprisonment in Castle Cachtice…

The Countess remained imprisoned at Cachtice. Despite the crown’s attempt to hold a retrial of Báthory and condemn to death, the agreement between Thurzo and Elizabeth’s family prevailed. When she attempted to challenge Thurzo authority, he condemned her in front of several of her relatives, saying, “You, Elizabeth, are like a wild animal. You are in the last months of our life. You do not deserve to breathe the air on earth, nor to see the light of the Lord. You shall disappear from this world and shall never reappear in it again. The shadows will envelop you and you will find time to repent your bestial life. I condemn you, Lady of Cachtice, to lifelong imprisonment in your own castle.”

Elizabeth Báthory was walled-in her castle apartment. The exterior windows were bricked up and only several small opening for ventilation and food gave her the only contact she had with the outside world. On August 21, 1614 one of the jailers observed the Countess collapsed on the floor. She died at the age of fifty-four. All mention of her name in Hungary was prohibited for the next one hundred years and the memory of her faded behind the mists of vampire and monster legends of Transylvania until her identity was rediscovered in 1720.

The Cult of the Blood Countess

From the Hungarian impressionist István Csók (1855-1961) lurid paintings depicting Báthory torturing her servants to a spate of movies, books and novels, the legend of the Blood Countess has resulted in a huge body of work celebrating her blood-bathing, even though its unlikely to have actually occurred as described.

Unanswered questions

A number of questions remain—and oddly enough the same kind of question haunts several cases of high-profile convicted female serial killers like Aileen Wuornos and Nazi concentration camp monster Ilsa Koch, the “Bitch of Buchenwald.” Were the identities of these women as serial killers constructed from social, political or propagandistic exigencies?

The attempts of the Hungarian Crown to seize Báthory’s property were evident. Moreover, Báthory was a Protestant when the Counter-Reformation and restoration of Catholic power became the priority of the Hungarian parliament. Religious sectarian politics exposed the Báthory family to all manner of hostility during that period.

Moreover, Europe was in the throes of a paranoid witchcraft crisis, with thousands of women being accused of heretical and satanic crimes and burned at the stake or hung. Yet at the same time, witchcraft was not one of the charges brought against Báthory. The rumors of her bathing in virgin girls’ blood were never introduced in any of the court proceedings simply because there was no evidence nor any testimony attesting to it.

Nonetheless, when we narrow down the charges to the murder of approximately fifty girls, there is a logical consistency to the descriptions of the offenses from many different witnesses. In the 1970s, two new archival sources were discovered in the Hungarian state archives. One source, dating from September 16, 1610—four months prior to Elizabeth’s arrest contained thirty-four affidavits describing Elizabeth Báthory’s torture and murder of “many girls and virgins.”(State Archives of Hungary, Budapest, Thurzo, F.28, Nr. 19 ) A second source is dated July 26, 1611 and is from the Crown’s attempt to retry Elizabeth. In it is a massive collection of testimony from 224 witnesses attesting to the “diabolical impulses” of the Countess who murdered “many innocent virgins of noble and non-noble birth.” (State Archives of Hungary, Budapest, Thurzo, f.28, 2.19)

If indeed Elizabeth Báthory was addicted to committing sadistic acts of torture since her adolescent years then 650 victims over a thirty-five year period works out roughly to a “mere” 19 victims a year. It is entirely conceivable with the power of life and death she had over her servants to have committed that many murders at that pace.

The descriptions of the alleged tortures she inflicted on her victims pathologically fit a sadistic power-control or sexual lust murderer—particularly in her choice of young female victims and her desire to bite them on the shoulder and breasts. What makes Báthory unique as a lust-hedonist female serial killer is that she continued to perpetrate the murders long after she lost her male partner. In recent history, when female lust serial killers are separated from their male partner after arrest, they frequently testify against the partner and earn a less severe sentence, as in the notorious cases of Charlene Gallago or Karla Homolka. In both cases, the women did not re-offend after their release from prison.

November 11, 2017

My Second Close Encounter With a Serial Killer: Andrei Chikatilo.

My first random encounter with a serial killer (Richard Cottingham) in 1979 was a hell of a story and I told it over drinks and dinners for a long time, long after I had met, but did not know it, yet another serial killer—one for the record books, the Ukrainian cannibal Andrei Chikatilo, who killed and mutilated an extraordinary fifty-three victims in the Soviet Russia.

In October 1990 I was shooting a television documentary in Moscow about the changes taking place there as the Soviet communist system was collapsing. One day we came upon an extraordinary sight. A tent city with about five hundred protestors had been spontaneously erected on the front lawn of a hotel immediately behind the Red Square beneath the domes of St. Basil’s Cathedral. The demonstrators seemed to have come in from all parts of the country and were mostly aged pensioners protesting Stalinist abuses of the past. They had bizarre placards attached to their tents and shelters. Some pasted to their foreheads little slips of paper protesting strange things written in broken English, such as “Lenin is bonehead.” Others held up placards with elaborately laid-out documents, letters, and photographs documenting their complaints.

I waded into the crowd with my cinematographer, Tony Wannamaker, and started speaking with some of the people, seeking out possible interviews to film. It seemed that almost everybody there was somehow traumatized or mentally ill, and considering what had happened to them during the Stalin era, it was understandable.

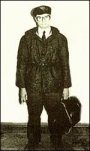

Suddenly I spotted a small stand decorated with the white, blue, and red of the old Imperial Russian tricolor flag. In 1990 it was still a rare thing to see those colors in the USSR. It belonged to a gaunt man with graying hair and big framed glasses. His other features I cannot recall, other than his being closely shaved and dressed relatively well (for Soviet-era Russia) in a cheap mid-length winter jacket, clean shirt, and neatly knotted tie. He looked to be maybe in his late forties or early fifties and stood out with his neat dress and younger age when compared to the many raggedy-scruffy bearded Russian pensioners occupying the tent city around him. There was something refined about him—perhaps even delicate or prissy. Next to him was a typical battered leather briefcase like those that almost every Soviet bureaucrat and office worker carried.

He introduced himself, but I forgot his name later and where he said he came from. At first he spoke quietly, calmly, and in a highly educated manner. The few phrases he attempted in English were well pronounced and grammatical. He reminded me of a librarian. He explained that he held several university degrees and was “not like” the rest of the rabble there. As his story began to pour out, he gradually was overcome with emotion; his eyes welled up with tears and his glasses actually fogged up. But his story was so absurd that I would never forget it: He was here in Moscow, he told me, to see President Gorbachev to complain that somebody was building an illegal garage and toilet beneath the windows of his son’s apartment in Rostov. It was a conspiracy, he wailed.

[image error]

I had just interviewed an old woman a few rows away who had told me she was dying of cancer and fifty years earlier had been arrested and put in the Gulag slave labor camp system while her children were sent to a state institution. She had not seen them since and was desperate to find them before she died, but the authorities were not helping. This neatly dressed man’s prissy complaints about some garage seemed to me petty and stupid in comparison—and worse: boring television.

Broadcast videotape was precious and difficult to find in Russia back then, and I did not want to waste it on this guy. Tony and I had a codeword: “this is a Kodak moment.” It meant, don’t waste videotape recording this; let’s move on. Searching for somebody else to interview, we drifted away from him as fast as we politely could, not even listening to the last few things he had to say, and quickly forgot all about him.

That is how I missed filming an interview with Andrei Romanovich Chikatilo—the “Red Ripper”—“Citizen X”—”The Butcher of Rostov”–three weeks before his capture—one of the most prolific serial killers in modern history.

[image error] [image error]

Between 1978 and 1990, Chikatilo murdered, mutilated and cannibalized 53 women, male and female youths and children. (He confessed to 56 and was convicted for 52.) He killed women, girls, boys, and youths indiscriminately, almost always luring them either to a killing shack he kept in a seedy part of town or to isolated fields or woods. He used his refined and educated persona to seduce his victims into trusting him. Often preying on the destitute, the mentally handicapped, the lost, and the young, he offered food, sex, shelter, or directions to entice his victims to accompany him to their deaths. Once he had his victims isolated, he would brutally attack and mutilate them using a “killing kit” of various knives and sharp instruments he carried with him in his briefcase.

Within days of my brief conversation with him in the Moscow tent city, he would return to his home in Rostov in the Ukraine to kill his fifty-first known victim. Riding on a local train, he convinced a sixteen-year-old mentally handicapped boy to accompany him to his “cottage” with the promise that there were girls there. The two got off the train and Chikatilo walked the boy into a dense wood, where he suddenly forced him to the ground and ripped off his trousers. He tied the boy with a rope that he carried with him in his briefcase just for that kind of occasion and then rolled him over and removed the rest of his clothes. (Was it the same briefcase I saw that day in the tent city?) He molested him and then bit off the tip of the boy’s tongue and stabbed him repeatedly in the head and stomach. Afterward he cut off the boy’s genitals and threw them into the bushes. After dragging the body into some thick undergrowth he recovered the rope and wiped the blood off himself and his knife with the boy’s clothes. He straightened out his own clothing (and was it the same shirt and tie I saw him in?) and then calmly returned to the nearby railway station and took the train home.

Ten days later at a different railway station, Chikatilo killed another sixteen-year-old boy, mutilating him in a similar fashion, his fifty-second victim.

A week later, behind the same station where he killed the mentally handicapped youth, he murdered his fifty-third and final victim, a twenty-two-year-old woman. He cut off the tip of her tongue and both her nipples after mutilating her genitals. After he emerged from the bush with blood smeared on his face, he was washing up at a platform water tap when a police officer, on the lookout for a killer, briefly questioned Chikatilo and recorded his identification. He was allowed to continue on his way—the police officer later stated that he had no way of determining that the smear on Chikatilo’s face was actually blood. Gorbachev’s new rules of civil society strictly regulated police conduct toward citizens—everything was to be done by the book now. The police officer let Chikatilo go, but for the next few days he was put under surveillance.

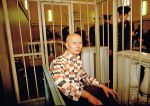

When the body of the female victim was eventually discovered near the station where he was questioned, Chikatilo was immediately arrested.

The following year I watched the Chikatilo trial broadcast on Russian television and saw photographs of him in the press. By the time the trial began, Chikatilo’s head was shaved and he appeared quite mad, exposing himself and howling at the courtroom spectators from within a specially built cage.

But even seeing the earlier photographs of him in the press, I never recognized him from that day I met him in the Moscow tent city. I still occasionally told my Richard Cottingham story, never realizing what punchline lurked beyond it. It was only years later that I came across a transcript of Chikatilo’s police interrogation in which he complained about the conspiratorial attempt to build a garage and toilet behind his son’s apartment and his intention to meet with Gorbachev in Moscow. I was transfixed in horror—could it possibly be the same guy? It had to be—the story was just too eccentric, and even the Russian investigator remarked on Chikatilo’s emotional peaks when he began to speak of the garage. Indeed, after some further research I uncovered an account of Chikatilo’s visit to Moscow in October 1990 just before he committed his last three murders.

Of Chikatilo himself, I have no memory—just that of his ridiculous story in the tent city and fragmentary glimpses of the monster: glasses, the knot of his tie, a clean-shaven cheek, a briefcase lying in the grass by his feet—but of him . . . nothing. This invisibility let him kill fifty-three people and almost walk away untouched, with blood on his face, from a police officer looking for him. What manner of ghoulish monsters were these?

I came to realize that in my life I had met not one, but two serial killers—unidentified and out there killing—and for the longest time I had not even known it. How many more could there be? And where the hell were they coming from?

I was puzzled by the conventional backgrounds of these two killers—both gainfully employed family men: Cottingham, a New York City computer operator with a house and three kids in the suburbs; and Chikatilo, a university-educated schoolteacher, father of two children, writer of political essays for Soviet publications, and, later, factory materials purchaser. These two were not grizzled glassy-eyed drifters or twitchy recluses—types we frequently associate with serial killers. They were ordinary.

Most of all, I was fascinated with their invisibility—their forgettability. Apparently, they stalked and killed like evil transparent ghosts. Even when I had run into Cottingham, presumably carrying two severed heads and having just set fire to a hotel I was checking into, I would forget him within seconds of the encounter. Cottingham was so forgettable that after leaving behind a mutilated corpse under a motel bed, he checked back into the very same motel a mere eighteen days later, and nobody recognized him.

While Richard Cottingham I remembered, I forgot everything about Chikatilo other than the neatness of his dress and the banality of his complaint. I do not remember his eyes, other than the tears in them and the fogged veil of the lenses in his glasses; nothing of his face other than it was clean shaven. He remains but a softly spoken shadowy politeness in my memory—but in my nightmares, he stills comes to me as a monstrous geek with eyeless sockets spewing tears.

[image error]

All of this led me to contemplate how Cottingham and Chikatilo came to exist—where had they sprung from and by what means and paths did they move about for me to so randomly stumble across these two homicidal monsters, roaming free in the wild among us?

In my attempt to map the primordial substance from which they rose, I came to write Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters, and in a way, map my own substance as well. Was there something about me that led me to cross the paths of these two serial killers so seemingly at random? I learned that many victims of serial killers “facilitate” their own deaths by their choice of lifestyle or behavior—hitchhikers, runaways, street hookers. While not a victim, I perhaps facilitated my meeting with Cottingham by my choice of hotels near a hookers’ stroll. I strayed into a serial killer’s hunting grounds as a trespasser and got a bump from a monster.

While my Cottingham encounter in New York was one of those experiences that one can easily write off as coincidence, my second encounter with a serial killer made me wonder. I questioned the mathematical odds of running into two killers in that manner. One killer I could easily understand, but two made me ask, how many more might there be out there that I did not know about? I wondered what the odds were of walking by a serial killer without ever finding out about it—on the street, waiting in line for a burger, browsing for books in a true-crime section, or sitting next to one on a train or bus? I shuddered when I heard somebody explain that serial killers might be strangers—but only to you. They become very familiar with you if they pick you as their target—you are no stranger to them.

It seemed to me that millions of people move about their daily lives without meeting a serial killer—or at least, without finding out they had met one. Perhaps that is precisely what makes me different from you—that I have uncovered the transparent monsters who had tramped across my path—my serial killers—while you perhaps have not uncovered yours. I pray you never will.

Andrei Chikatilo was executed in 1994.

From Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters

[image error]

November 8, 2017

The origin of the term “serial killer”: a History.

When I encountered “my” first serial killer – Richard Cottingham, the “Times Square Torso Ripper” in December 1979, I had never heard of the term “serial killer.” Although the term “serial killing” had been occasionally used during the 1970s in the law enforcement community, in popular media it was called by a host of different labels like “stranger-on-stranger murder,” “recreational killing,” “pattern murder,” “thrill killing,” “multicide,” “psycho murder,” “sequential homicide,” “compulsive murder,” “multiple murder,” “motiveless killing,” “lust murder,” “spree killing” or confusingly “mass murder,” which today we define as a single rampage of multiple murders. Nobody agreed on a single term for it or what defined it nor did anybody assemble all those different multiple killer profiles and their characteristics into named constellations or categories.

To me, Cottingham was some kind of Alfred Hitchcock movie monster, and when in 1980 I bought my first book on the subject to try to understand better what it was I had encountered, Ann Rule’s seminal book on Ted Bundy, The Stranger Beside Me, the term “serial killer” did not appear anywhere in the pages of her book.

[image error]It was only on May 3, 1981 that the serial killer and serial murderer constructs first began appearing in the New York Times when referring to Wayne Williams, suspected in the murders of thirty-one children in Atlanta between 1979 and 1981. The New York Times wrote

The incident underscored the belief of many law-enforcement officials and forensic scientists in Atlanta that only some of the killings are the result of a “serial” or “pattern” murderer. . . .

If the New York Times is America’s national “paper of record,” then Wayne Williams is America’s first “serial killer of record.”

There is no one single story as to who coined the term ‘serial killer’ and it is entirely plausible that several people independently proposed the term. According to Ann Rule, California detective Pierce Brooks first coined it. True crime author Michael Newton points out the term is used by author John Brophy in 1966 in his book The Meaning of Murder. Author Howard Schechter and criminal deviance scholar Lee Mellor discovered that Ernst August Ferdinand Gennat, the Chief of the Berlin Police, used the term serienmörder (serial murder) in the 1930s to describe the crimes of Peter Kürten.

The earliest English language use of the term “serial killings” I could find in print was by the Biblical scholar, historian, and concentration camp survivor Robert Eisler, in his annotations to a lecture he gave on sadism and anthropology to the Royal Society of Medicine in London in 1948. The lecture was published posthumously in 1951 as a heavily footnoted book entitled Man Into Wolf: An Anthropological Interpretation of Sadism, Masochism, and Lycanthropy. In describing innate infantile sadism, Eisler wrote

The serial killings in the ‘Punch and Judy’ plays for children are so enjoyable because the puppets are of wood and the beaten skulls sound so wooden and insensitive. Nevertheless, this enjoyment is certainly the harmless ‘abreaction’ of the cruel urges of infancy.

Even earlier possibly, the words “Whitechapel serial killer” apparently are used in a newspaper article in the November 9, 1888 edition of the London Daily Post’s coverage of Jack the Ripper. The words appear in a stock house montage of Victorian-era newspaper clippings, the authenticity of which I was not able to confirm before this book went to press. See the end of the first paragraph in the second column of the newspaper in the image: http://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-the-londonpost-november-9th-1888-clippings-of-the-fifthand-final-52938673.html

While perhaps various people proposed it, I personally believe the most plausible coiner of the term serial killer as we are familiar with it today is FBI agent and behavior sciences profiler Robert K. Ressler. He felt the popular term for serial murder, “stranger killings,” was inappropriate because not all victims of serial killers were strangers. Ressler was lecturing at a police academy in England in 1974 when he heard the description of some crimes as occurring in “a series”—a series of rapes, arsons, burglaries, or murders.

Ressler said that the description reminded him of the movie-industry term for short episodic films shown on Saturday afternoons during the 1930s and 1940s: “serial adventures.” Audiences were lured back to movie theaters week after week by the inconclusive ending of each episode—the so-called “cliff-hanger.” Instead of providing a satisfying conclusion, these endings increased rather than decreased the tension in the audience. Likewise, Ressler felt, serial killers experience a ‘cliffhanging’ tension and desire after every murder to commit a more perfect murder than before, one that is closer to their fantasy. Rather than being satisfied when they murder, serial killers are instead addictively compelled to repeat their killing in an often-unending cycle; a pattern of serial movie-like ‘cliff hanger’ murders. Serial killing, Ressler argued, was a very appropriate description of the compulsive multiple homicides that he believed he was dealing with.

November 2, 2017

Was H.H. Holmes the First American Serial Killer?

[image error]

There has been a lot of nonsense recently featured on History Channel’s American Ripper, suggesting that H.H. Holmes was not only the “first American serial killer” but also Jack the Ripper who committed a series of infamous unsolved murders in the Whitechapel district of London in the summer and autumn of 1888.

In my forthcoming book Sons of Cain, I ‘rip’ into the bullshit claims made in American Ripper.

Who is considered the “first” American serial killer depends on the ‘flavor of the month’ in literature, film and other popular media. At this writing, Herman Webster Mudgett, also known as Dr. Henry Howard Holmes or simply H. H. Holmes is often called America’s “first modern serial killer.”

Recently film director Martin Scorsese announced he is making a film, with Leonardo DiCaprio as Holmes, based on the Erik Larson bestseller, The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America. Hollywood’s publicity machine went into action to tout Holmes as “America’s first serial killer” as a prelude to the upcoming movie.

If you accept the FBI’s new 2005 definition of a serial killer as somebody who has murdered two or more victims in separate incidents for any reason (supplanting the old three or more victims threshold) then I can reference five serial killers who murdered two or more victims before or contemporary to H.H. Holmes:

◦Jesse Pomeroy “The Boy Fiend”—Boston, 1874 who abducted and tortured a series of children, and is known to have murdered two of them.

◦Joseph Lapage “The French Monster”—Vermont/New Hampshire, 1875 who is known to have murdered at least two women.

◦Thomas W. Piper “The Bat” and “Boston Belfry Murderer”—Boston, 1875 who murdered three victims, 2 women and a girl.

◦The Servant Girl Annihilator—Austin, Texas, 1885 who murdered seven women.

◦Theodor ‘Theo’ Durrant “The Demon of the Belfry”—San Francisco, 1895, a necrophile serial killer with two confirmed victims, arrested the same year that H.H. Holmes was arrested.

And that’s without naming notorious American frontier serial killers like the Harpe Brothers in Tennessee in the 1790s or the Bloody Benders and their “murder inn” in Kansas, 1869-1872.

All these cases I describe in detail in Sons of Cain and all of them fall into the current FBI definition of what constitutes a serial killer.

In fact, H.H. Holmes officially was convicted of only one murder: of his employee and insurance fraud co-conspirator, Benjamin F. Pitezel; but the evidence is persuasive that Holmes took custody of three of Pitezel’s children and later murdered them as well, for a total of four victims. That does indeed make him a serial killer, but not necessarily the first in America.

After his conviction, H.H. Holmes in a series of paid newspaper articles claimed to have murdered twenty-seven people. But “only” nine of the twenty-seven murders that Holmes confessed to were actually found to have occurred, and none were ever conclusively linked to Holmes.

[image error]

At the center of the H.H. Holmes myth is his elaborate “Murder Castle”, a hotel with alleged secret rooms, gas connections and chutes in which he was said to have murdered guests during the Chicago World’s Fair in 1883. There is no evidence that anybody had been murdered at his premises or that they even served as a hotel during the World’s Fair. As Adam Selzer points out in his deeply researched and definitive H. H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil, “Many of the stories of him and his “Castle” are pure fiction. The castle never for one day truly functioned as a hotel, and the actual number of World’s Fair tourists he’s suspected of killing there has remained the same since 1895—a single woman, Nannie Williams. The hidden rooms were almost certainly used more for hiding stolen furniture than for destroying bodies.”

[image error]

As for H.H. Holmes being Jack the Ripper, there is not a shred of evidence that H.H. Holmes visited Britain at any time. For one thing, he spent that year in Chicago supervising the complex construction of the Castle with its hidden passageways and secret rooms (apparently firing workers and contractors every few weeks so that nobody could get a full picture of the architecture and its sinister purpose). Secondly, there are absolutely no profiling ‘signature’ similarities between the highly pathological murders of prostitutes by Jack the Ripper and the known murders committed by H.H. Holmes of Benjamin F. Pitezel and his three children.

The rest, is entertaining “conspiracy theory” television. Fun but nothing to do with the truth about the history of serial murder in the USA.

November 1, 2017

My First Close Encounter with a Serial Killer: How and Why I Began Writing About Monsters

[image error]On the morning of December 2, 1979, when I was 23-years-old, I briefly and completely at random, encountered a serial killer in the lobby elevator doors of a seedy hotel that I was attempting to check into on W 42nd Street in New York.

He had raped, tortured, mutilated, murdered and beheaded two prostitutes in his room upstairs, set their torsos on fire and fled with their heads, which remain missing to this day. One of the victims would be later identified as 22-year old Deedeh Goodarzi, while the other still remains a “Jane Doe” today.

[image error]

We briefly stared at each other in the elevator doors in the lobby. I had given him a close and hard “you jerkoff” look because I was annoyed that he had held up the elevator I had been impatiently waiting for. I would remember his strange “haircut” (he was apparently wearing a wig as a disguise), his lightly chubby face glowing with a sheen of perspiration and blank eyes that seemed to stare through me, as if he was stoned or in some kind of daze.

As he got off the elevator past me, actually walking through me as if I was not there, he bumped me on the shins with a soft bag that felt as if it contained bowling balls.

As the fire set off alarms and was evacuated, I never ended up staying at the hotel and only learned what had caused the fire the next morning when I read about it in the newspapers. Even then, I did not immediately associate the “jerkoff” with the “bowling balls” on the elevator with the killer. It was only some six months later, when he had been arrested and charged and his picture appeared in the newspapers that I recognized Richard Cottingham, the “Times Square Torso Ripper” as he became known.

[image error]

Richard Cottingham, who upon his arrest told police, “I have problems with women”, had been raised in a stable, upper-middle-class strict Catholic family in New Jersey. Mom was a housewife while dad was an insurance company executive in Manhattan. “Richie” had been a high school athlete, and when arrested was still living in New Jersey. He was married and a father of three children and was gainfully and lucratively employed for over a decade as a computer console operator at the offices of Blue Cross Insurance in mid-Manhattan. He also had two mistresses, nurses, who did not know about each other. Working a shift from 4 P.M. to midnight, Cottingham would commit his savagely sadistic murders in Manhattan and New Jersey between dates with his mistresses, his hours at Blue Cross and his commute home to his wife and kids in Lodi, New Jersey.

Cottingham was eventually convicted for five mutilation rape torture murders of women and recently (in 2010) he suddenly pleaded guilty to a sixth earlier murder in 1967. He is suspected in an additional thirty to fifty unsolved murders in New York and New Jersey between 1967 and 1980.

Cottingham would be the first of two serial killers that I would encounter, completely at random between 1979. In both cases I did not know at the time I was encountering a serial killer.

As a historian I became curious about where these monsters I had encountered sprang from and it inspired a life-long interest in their nature and origin, which culminated with my first book on their history published in 2004: Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters.

Recently, I published a more extensive account of my encounter and the Richard Cottingham case in Times Square Torso Ripper: Sex and Murder on The Deuce.