Mark Canter's Blog: Selling Storytelling

December 2, 2014

Openings

A recent poll conducted on behalf of Romance Writers of America found that the chief factor that motivates book browsers to choose a particular romance novel is attraction to the story (outranking other draws, such as author and reviews).

Equipped with this information, I observed shoppers browsing in a Tallahassee book store and watched how they pick a book. In every case they first read the story blurb on the book flap or back cover and then read the first couple pages before either returning the book to the shelf or heading off to the cashier with their prize.For you as a writer this means you’ve got to deliver a dynamite opening sentence and first chapter. No long wind-ups, but bang!—straight into the heart of your story. So if you reread your first draft and realize that the story doesn’t kick in until page twelve, that’s twelve pages too late! Ditch those warm-up pages. If they contain important information or character development, salvage it for insertion elsewhere in your novel, perhaps as back-story. Even as long ago as the First Century BCE, the Roman poet Horace (best known for his poem Carpe Diem—“Seize the Day”) recommended that literature begin in media res—“in the midst of things.” In other words, with characters already engaged in dramatic action.Study how the masterful Nora Roberts opens the door to her novel Witness with a sentence that immediately conveys both character and the threat of violence:

Elizabeth Fitch’s short-lived teenage rebellion began with L’Oreal Pure Black, a pair of scissors and a fake ID. It ended in blood.

Maxine Hong Kingston begins The Woman Warriorwith this hook:

“You must not tell anyone,” my mother said, “what I am about to tell you.”

The first paragraph of Diana Gabaldon’s blockbuster, Outlander, economically conveys intrigue and setting and characterization:

It wasn’t a very likely place for disappearances, not at first glance. Mrs. Baird’s was like a thousand other Highland bed-and-breakfast establishments in 1945; clean and quiet, with fading floral wallpaper, gleaming floors, and a coin-operated hot-water geyser in the lavatory. Mrs. Baird herself was squat and easygoing, and made no objection to Frank lining her tiny rose-sprigged parlor with the dozens of books and papers with which he always traveled.

Patricia Briggs begins Moon Called, the first book in her paranormal romance series starring the shape-shifter, Mercy Thompson, with a scene that introduces the heroine as an auto mechanic—with an extraordinary sense of smell.

I didn’t realize he was a werewolf at first. My nose isn’t at its best when surrounded by axle grease and burnt oil—and it’s not like there are a lot of stray werewolves running around. So when someone made a polite noise near my feet to get my attention I thought he was a customer.

Here are opening sentences from a few of my own short stories and novels.

Mason Drake awoke and saw the pilot burning. Flames climbed up the dead man’s flight jacket and the red nylon melted.

If Tom Harding had been paying attention to his fingertips when they began to tingle, the strangest encounter of his life would not have happened.

When my transition drew near, an Unsurpassable Lover came to my door, her puffy-eyed silence foretelling terrible news.

“Where were you last night?”I rolled onto my side and a headache thunder-clapped through my skull. A nude woman occupied with me a bed so broad it seemed a landscape of satin sheets. “Where did you go last night?” she said again. Whoever she was, she was royalty. A holo-tattoo of the Imperial Dragon coiled around the pupil of her left eye, shimmering iridescently.

Once you’ve crafted enticing opening sentences, your readers need to be told within the next two or three pages:

· WHO is the story’s hero?· WHERE does the story take place?· WHAT conflict does the hero face?· WHY should we care? (Hint: because the hero is likable.)

All of the above does not imply slaving over your first paragraphs, insisting that they be perfect before you can move on with writing your story. If you feel stuck on the opening scene, plunging deeper into the tale might be your best strategy. After fifty or a hundred pages, when your characters and their struggles to find love have become real and alive for you, you’ll probably have a strong idea how to go back and rewrite the beginning.

Published on December 02, 2014 06:39

Opening Sentences

A recent poll conducted on behalf of Romance Writers of America found that the chief factor that motivates book browsers to choose a particular romance novel is attraction to the story (outranking other draws, such as author and reviews).

Equipped with this information, I observed shoppers browsing in a Tallahassee book store and watched how they pick a book. In every case they first read the story blurb on the book flap or back cover and then read the first couple pages before either returning the book to the shelf or heading off to the cashier with their prize.For you as a writer this means you’ve got to deliver a dynamite opening sentence and first chapter. No long wind-ups, but bang!—straight into the heart of your story. So if you reread your first draft and realize that the story doesn’t kick in until page twelve, that’s twelve pages too late! Ditch those warm-up pages. If they contain important information or character development, salvage it for insertion elsewhere in your novel, perhaps as back-story. Even as long ago as the First Century BCE, the Roman poet Horace (best known for his poem Carpe Diem—“Seize the Day”) recommended that literature begin in media res—“in the midst of things.” In other words, with characters already engaged in dramatic action.Study how the masterful Nora Roberts opens the door to her novel Witness with a sentence that immediately conveys both character and the threat of violence:

Elizabeth Fitch’s short-lived teenage rebellion began with L’Oreal Pure Black, a pair of scissors and a fake ID. It ended in blood.

Maxine Hong Kingston begins The Woman Warriorwith this hook:

“You must not tell anyone,” my mother said, “what I am about to tell you.”

The first paragraph of Diana Gabaldon’s blockbuster, Outlander, economically conveys intrigue and setting and characterization:

It wasn’t a very likely place for disappearances, not at first glance. Mrs. Baird’s was like a thousand other Highland bed-and-breakfast establishments in 1945; clean and quiet, with fading floral wallpaper, gleaming floors, and a coin-operated hot-water geyser in the lavatory. Mrs. Baird herself was squat and easygoing, and made no objection to Frank lining her tiny rose-sprigged parlor with the dozens of books and papers with which he always traveled.

Patricia Briggs begins Moon Called, the first book in her paranormal romance series starring the shape-shifter, Mercy Thompson, with a scene that introduces the heroine as an auto mechanic—with an extraordinary sense of smell.

I didn’t realize he was a werewolf at first. My nose isn’t at its best when surrounded by axle grease and burnt oil—and it’s not like there are a lot of stray werewolves running around. So when someone made a polite noise near my feet to get my attention I thought he was a customer.

Here are opening sentences from a few of my own short stories and novels.

Mason Drake awoke and saw the pilot burning. Flames climbed up the dead man’s flight jacket and the red nylon melted.

If Tom Harding had been paying attention to his fingertips when they began to tingle, the strangest encounter of his life would not have happened.

When my transition drew near, an Unsurpassable Lover came to my door, her puffy-eyed silence foretelling terrible news.

“Where were you last night?”I rolled onto my side and a headache thunder-clapped through my skull. A nude woman occupied with me a bed so broad it seemed a landscape of satin sheets. “Where did you go last night?” she said again. Whoever she was, she was royalty. A holo-tattoo of the Imperial Dragon coiled around the pupil of her left eye, shimmering iridescently.

Once you’ve crafted enticing opening sentences, your readers need to be told within the next two or three pages:

· WHO is the story’s hero?· WHERE does the story take place?· WHAT conflict does the hero face?· WHY should we care? (Hint: because the hero is likable.)

All of the above does not imply slaving over your first paragraphs, insisting that they be perfect before you can move on with writing your story. If you feel stuck on the opening scene, plunging deeper into the tale might be your best strategy. After fifty or a hundred pages, when your characters and their struggles to find love have become real and alive for you, you’ll probably have a strong idea how to go back and rewrite the beginning.

Published on December 02, 2014 06:39

October 5, 2014

Dialogue

Let’s talk about talking. The three different types of dialogue are 1) direct, 2) indirect, and 3) mixed.

Direct dialogue is the most dramatic form. By convention, direct dialogue requires quotation marks and each speaker gets his or her own paragraph. At the end of each speaker’s part, simple attributions (he said, she said) are best, and even they can be omitted when it’s clear who is speaking.

“You?” she said. “No way.”“Trust me,” he said, “in a big way.”“That’s just it; I don’t trust you.”

While “he said, she said” are virtually silent and invisible to the reader, the menagerie of other attributions (asked, answered, replied, retorted, added, commented, snarled, whined, etc.) draw attention to themselves and, like blush, should be used sparingly. Also, resist the urge to glom adverbs onto the attributions (she said grudgingly, he said wolfishly, etc.). Adverbs are not needed and are often used to explain what is already obvious to the reader (“I despise you!” she said angrily).Using indirect dialogue can summarize a conversation in a brief report that, without quoting, still conveys richness:

Sheryl said that going to bed with David was selfish, crazy and impossible to resist.

Mixed dialogue, the third type, is a hybrid of direct and indirect:

Rob told Trisha she was narcissistic. That she paid no attention to what was right for him. Their pink bedroom with the four-poster bed and lace curtains was a good example. He told her, “I don’t want frills and flowers!” He said it two or three times.

People speak variously and dialogue is an effective way to establish unique characters. A common critique in writing circles is that a story’s characters all talk alike. Hear the difference in the diction of these two speakers:

“I’m not a forensic scientist, but it appears to me the bullet entered her body from behind.”“Hell, you don’t need to be no expert on this stuff. Sure as hell she got offed from the back.”

When we converse, we communicate not just with words but with our bodies. Realistic dialogue is more than a sequence of quotations; it includes nervous grins, fiddling with fingernails, lowered eyes, raised eyebrows: our whole human language. Such details and actions that punctuate dialogue are called “beats.” Writing good beats makes for vivid conversations that your readers can readily follow, and allows you to show which character is speaking without using attributes.

“Sorry, but that’s not what we agreed to.” Johnny tapped the contract on his desk, then flipped to the last page and held it up. “This is your signature, right?I was doomed. I nodded and stood to leave.“Just a sec.” He opened a drawer and took out a Glock handgun. “Take this. It goes along with the envelope.”

Beats are also used for conveying a realistic rhythm of speech. Instead of writing “he paused,” toss in a beat:

“Divorce?” He dragged on his Camel. “Really?” He screwed his mouth to the side and blew out smoke. “How long you been married, four, five months?”“One hundred forty one days.” She glanced at her watch. “And eight hours, fifteen minutes.” She gave an unhappy laugh. “But who’s counting?”

Also consider using sound effects as a rhythmic element in your beats:

“A hundred dollars.” He stacked a log vertically on the stump. “What you mean is…” He swung the axe and the wood split halfway with a loud crack! “…a hundred more.” He swung again. Crack! The split halves fell onto piles on either side of the stump. “That makes a couple hundred.” He stacked another log without looking at his son. “I got to ask myself if you’re worth it.”

Lastly, keep in mind that the words in a dialogue reveal only the surface. Like icebergs, most of a conversation’s weight is hidden below. You can create tension between what is visible and what is submerged by keeping the dialogue evasive, filled with unspoken feelings.

If he used one more French phrase tonight, she was going to spit out the Bordeaux he ordered for her and get a pitcher of Bud. Why was he showing off? He grew up right here in Burnt Mill, same as her. He worked at the lumberyard, like her dad and brothers, and he drove a Ford pick-up, not a Lamborghini. “J'aime vos beaux yeux verts.”She smiled. “Oui, monsieur!” She had no idea what he said. By now any other guy would have said something sweet, maybe complimented her on her green eyes. How do you say in French, “Billy Ray, just be yourself!”

Published on October 05, 2014 13:50

August 6, 2014

Reinventing Reality

Unless the plot of your romance absolutely demands a real-life locale, you’ll do yourself a favor by inventing your setting—but not out of whole cloth. For authenticity, it’s best to thoroughly research factual models for the fictional elements that you create.

For example, most of the action in my first novel, Ember from the Sun, takes place in the Pacific Northwest among a contemporary Native American tribe. I used as my model the Haida tribe who live on Haida Gwaii (the Queen Charlotte Islands, Canada). I studied the Haida Indians in depth, learning about their history, language, customs, religion, art, clothing, housing, and methods of fishing and whaling. I also researched the Queen Charlotte Islands’ flowers and trees, birds and mammals, topography and climate. Then, after two months of research, I named my fictitious tribe the Quanoot, and its imaginary homeland, Whaler Bay Island. Studying the real tribe and its actual territory enabled me to enhance the novel with authentic particulars. For instance, the story included a scene in which modern Quanoot men build a war canoe by the ancient, traditional method of the Haida.

On the other hand, creating an imaginary tribe gave me the wiggle room to focus on the needs of my narrative without stressing about getting facts wrong, and I was free to invent a Quanoot legend that was central to my plot without feeling that I was appropriating a real people’s culture.At first glance, it may seem that this advice mostly pertains for authors of historical romances, but it is at least as relevant for authors of contemporaries. Consider that while there are many readers who are experts on various historical periods, there are probably far more who know about whatever contemporary reality you plan to describe. They’ll be swift to notice errors of fact. Therefore, unless your story utterly requires an actual place, set it an apocryphal locale.

Let us say that your love story involves a hero who was once a logging crew foreman, but now he’s seeking employment because the logging industry has collapsed. For authenticity, find a real town that fits your story’s needs and use it as the pattern for your research. Read everything you can find about the town and the logging industry; study maps and nature guides; visit the area and interview loggers and the mayor, and so forth. But when your research is done, don’t write about the actual town; make up your own.

I’m currently researching a YA novel whose heroine is the Eastern Surfing Association Junior Women’s Champion. This is a case of writing what I know: I grew up in the surfer subculture in Melbourne Beach, Florida, and I once dated the current ESA Junior Women’s champion (back in the Pleistocene Era). I’m going to return to my favorite surf spots and interview surfers there and at the local surf shops. Nonetheless, I’m not going to set the novel in my real hometown. There are thousands of people living there now and some readers will balk at any detail I change or simply get wrong. But no one ever gets upset and slings a book across the room just because she suspects that such-and-such a town can’t be found on any map; so I’ll set my story in “Satellite Shores”—population zero, because the place does not exist.

The beauty of this research-and-switch method of creating fiction is that you can convey the genuine ambience of a real setting—Florida’s east coast, or an economically depressed logging town in Oregon—without trapping your plot in specifics. Remember the motto of tabloid journalists: “Never let the facts get in the way of a good story!”

Published on August 06, 2014 21:09

June 13, 2014

Making Full Use of Setting

If a detective snooped through your residence while you were away, chances are he or she could construct a fairly detailed and reliable profile of your personality, based on your environment (your setting). That’s because your character is revealed not only by what you say and do, but also by the food in your pantry, the clothes in your closet, the artwork on your walls, the knick-knacks lining your mantle, your movie and music collection, the titles filling your bookshelves, and so forth.

As writers we can use the specific setting in which we place a scene to show the inner workings of our fictional characters. An effective way to do this is to describe setting subjectively through the character’s senses, emotions and memories, rather than neutrally, through a “camera lens” of objective narration. This technique accomplishes a few things:

1. It keeps the writer invisible. The information arrives through the character’s perceptions, not from a disembodied narrator. 2. It saves time and thus moves the story faster. Readers get necessary descriptions of your character’s surroundings while simultaneously learning about their personalities.3. It’s a handy way to weave in backstory, without resorting to flashbacks elsewhere that can break up the immediacy of the action and dialog.

You can show contrasting personalities and reveal backstories by having more than one character react to the same environment, or to the same object within it. For example, a time-worn baseball glove might evoke nostalgia in an old man, who as a gifted pitcher once made it as far as the minor leagues; while the same glove elicits anger in his adult son, who resents that his father forced him to endlessly practice pitching in the hope the boy would fulfill the father’s dreams and one day pitch for a major league team.

A further use of setting is to establish the mood or tone of your overall story or of a particular scene. Notice how movie directors often open a scene with an “establishing shot” to set up the context and mood for the action that is about to occur. Films must accomplish this while relying on only two senses, vision and sound. The beauty of a written story is that you can convey the setting and mood of a scene through all five senses. Make it a habit to exploit this advantage by including more than just seeing and hearing in your scenes. Give your reader plenty of smells, textures, and flavors. (Also, notice that verbs can perform double-duty as sounds: the bullet chunked into the wall… the arrow thwacked the target.)

Pay special attention to the sense of smell. Neuroscience confirms what you may have discovered in your own experience: aromas trigger memories and emotions more strongly than any of the other senses. It’s easy to imagine a character going through the personal belongings of her late grandfather, feeling a mix of happiness and sorrow when looking at photos of the grizzled man in his wide-brimmed fishing hat. But when she actually smells his faithful hat—its familiar mix of cigarette smoke, hair oil, and a hint of fishing bait—that’s when the tears finally flow.

The more vividly you convey the setting of each scene, the better chance you have of accomplishing the writer’s goal of implanting your readers inside your story. On the other hand, some settings are so familiar (for example, the interior of a MacDonald’s restaurant) that description should be kept to a minimum. Set the stage with just a couple details that readers will instantly recognize.

Even if you’re writing historical fiction or placing a scene in an exotic locale, it’s best not to slow down the story with pages of description. Instead, interweave bits of description into the forward-moving action. Think of particulars (sights, sounds, smells, tastes, flavors, and textures) that exactly define the setting. These are called “telling details”.

Forty years ago I stood in freezing air-conditioning under banks of surgical lamps in the cadaver dissection room of a medical school. A dozen aluminum exam tables held male and female corpses draped to their chests in blue plastic sheets, the right sides of their necks and faces cut down to the white bones. The sharp reek of formaldehyde filled my nostrils and mouth.

If I used the above setting in a fictional scene, I would insert these telling details into the dialog and action a piece at a time to paint a clear picture without slowing the story’s momentum.

As writers we can use the specific setting in which we place a scene to show the inner workings of our fictional characters. An effective way to do this is to describe setting subjectively through the character’s senses, emotions and memories, rather than neutrally, through a “camera lens” of objective narration. This technique accomplishes a few things:

1. It keeps the writer invisible. The information arrives through the character’s perceptions, not from a disembodied narrator. 2. It saves time and thus moves the story faster. Readers get necessary descriptions of your character’s surroundings while simultaneously learning about their personalities.3. It’s a handy way to weave in backstory, without resorting to flashbacks elsewhere that can break up the immediacy of the action and dialog.

You can show contrasting personalities and reveal backstories by having more than one character react to the same environment, or to the same object within it. For example, a time-worn baseball glove might evoke nostalgia in an old man, who as a gifted pitcher once made it as far as the minor leagues; while the same glove elicits anger in his adult son, who resents that his father forced him to endlessly practice pitching in the hope the boy would fulfill the father’s dreams and one day pitch for a major league team.

A further use of setting is to establish the mood or tone of your overall story or of a particular scene. Notice how movie directors often open a scene with an “establishing shot” to set up the context and mood for the action that is about to occur. Films must accomplish this while relying on only two senses, vision and sound. The beauty of a written story is that you can convey the setting and mood of a scene through all five senses. Make it a habit to exploit this advantage by including more than just seeing and hearing in your scenes. Give your reader plenty of smells, textures, and flavors. (Also, notice that verbs can perform double-duty as sounds: the bullet chunked into the wall… the arrow thwacked the target.)

Pay special attention to the sense of smell. Neuroscience confirms what you may have discovered in your own experience: aromas trigger memories and emotions more strongly than any of the other senses. It’s easy to imagine a character going through the personal belongings of her late grandfather, feeling a mix of happiness and sorrow when looking at photos of the grizzled man in his wide-brimmed fishing hat. But when she actually smells his faithful hat—its familiar mix of cigarette smoke, hair oil, and a hint of fishing bait—that’s when the tears finally flow.

The more vividly you convey the setting of each scene, the better chance you have of accomplishing the writer’s goal of implanting your readers inside your story. On the other hand, some settings are so familiar (for example, the interior of a MacDonald’s restaurant) that description should be kept to a minimum. Set the stage with just a couple details that readers will instantly recognize.

Even if you’re writing historical fiction or placing a scene in an exotic locale, it’s best not to slow down the story with pages of description. Instead, interweave bits of description into the forward-moving action. Think of particulars (sights, sounds, smells, tastes, flavors, and textures) that exactly define the setting. These are called “telling details”.

Forty years ago I stood in freezing air-conditioning under banks of surgical lamps in the cadaver dissection room of a medical school. A dozen aluminum exam tables held male and female corpses draped to their chests in blue plastic sheets, the right sides of their necks and faces cut down to the white bones. The sharp reek of formaldehyde filled my nostrils and mouth.

If I used the above setting in a fictional scene, I would insert these telling details into the dialog and action a piece at a time to paint a clear picture without slowing the story’s momentum.

Published on June 13, 2014 12:36

May 3, 2014

Pictures from Home (a short story first published in Aboriginal Science Fiction magazine)

Twelve left.

Twelve left.Twelve out of 968, homeward bound.

Eleven, really, because Lt. Brye isn’t going to last much longer.

About a hundred beds failed outright when the system crashed. Those in stasis slipped into death; not too far to fall from minimally alive—and no pain. Those were the lucky ones. Other beds partly revived us survivors.

Obviously nobody made it to normtemp or he’d have done an M.O. on the program and thawed the rest of us: eleven trapped in sub-wake; Brye fading so fast now I don’t count her.

“Bingo. Got an open channel on a recon-sat above the Florida Keys.” The lieutenant is whispering hoarsely into her com, slurring her words. Her voice is weakening, though her jaw muscles and tongue are probably long past the stage of searing pain.

“Magnificent,” she says. “The Keys are shimmering white like a string of pearls against the blue Atlantic. Hold for zoom. Ah… I see a boat… yes, locked on a dive boat; she’s heading out to a coral reef. Looks like seven, make that eight divers aboard. What a day. Golden sun, water so clear I can make out a school of barracudas. I dove this reef myself, many years ago. Got a sunken hydrofoil lying on its side, home to a nurse shark named Mighty Mom.”

She’s talking about Sugar Reef, where she made her first open-water dive. I’ve heard this story. I’m amazed she was able to find the very reef. Mighty Mom. How her buddies laughed their butts off when she scrambled back on deck. Ow, it really burns when I smile. Tough it out, limber up—I’m next on the intercom.

Brye is good. For a few moments I had forgotten the constant, bottomless cold. What the oldspacers call white pain. Like my brain is floating in a bucket of CryoGen and my spinal cord is a branching tree of ice. Can’t move a stiff finger without feeling the scorching lava of a thousand cell walls bursting. But as soon as the burning subsides, the infinite chill swallows the site where the fire flared, and all is uniformly frigid again, a polar ocean.

Sub-wake under normal conditions is no joy drug. I hated it when it lasted, what?—all of ten minutes? A freezing zone to be endured while dropping to the blank night of stasis, and suffered again on the rise back to normtemp.

“A controlled cooling to near-death,” instructor Barnes had said. Right. More like the science of turning blood to slush. “The ache is minimized by remaining perfectly motionless,” he said in my earpiece on that first drop. “Fight it, and it will injure or even kill you. You must lie absolutely still and let the freeze take you—in which case, deaths are rare.” Bastard loved to scare us.

We’d learned in lectures that the early crews used anesthesia to skip the agony phase of cryostasis. But the failure-to-wake ratio was around eight percent then; more for long trips, New Beijing and farther. They found out when you bypass the pain of freezing, the body and brain don’t adjust as efficiently to stasis as when you consciously penguin down through the stages. Full penguin knocks the deadsleeps to less than one-tenth of one percent.

Cold or old, they say. Wish now I had chosen to age. Some manage okay on shorter treks. Mostly married crew who want to have the same number of wrinkles as their mates when they get home. Or brainiacs who spend the trek studying—three or four Ph.D.’s and counting. But a seven-year roundtrip is definitely pushing it; I’ve never heard of anyone who could live in a tin can that long and not start clawing at the air locks.

We all chose stasis. Colonists dropped in the first week. Crew two weeks later. System crashed almost immediately, less than a month out-trek. Eighteen initial survivors of the 32-person crew, but not one of the more than 900 colonists. Twelve—minus one—crewmembers now remaining, damned to icy purgatory. Not the hot bliss of hell where red coals bake your bones, but this blue-black arctic winter without a sun. And you can’t just pass out and sleep through it; sub-wake stims the brain so that sleep is physiologically impossible. Great gimmick for a horror sensum, right? But the holo-theaters would have to carry medical insurance, like for xenoporn; only in this case, the audience would get psychosomatic frostbite, not cardiac arrest from climaxing with a nerve-orchid.

Five weeks since Capt. Ochiba sub-woke and died the same day, a mayfly. But she lived long enough to get a fix on our position and lock the navcom on Earth base. The ship immediately began decelerating, but it took a couple weeks to reverse course without pulling too many G’s or expending too much fuel. Now we’re accelerating toward home and of course we’ll have to brake again when we get there.

The captain announced she had opened an omni-channel link and the bright blue curve of Earth filled her screen. The captain is a hero. No question. She had to have struggled in excruciating pain; just moving her fingers over the armrest keys must have felt like napalm bubbling her flesh. If she hadn’t laid in a course for home, I’m sure I’d be dead by now in my freezing coffin. She transferred the satellite link to Rudd’s screen and said something in Japanese—I caught “Sayonara”—before the tissue damage finished her.

My guess is Christian terrorists planted a timed virus in our A.I. mainframe. Whatever crashed the system screwed the com network—the satellite omni-link can display on only one computer at a time. So everybody has to wait in line to view home from his own screen. The obvious way to take turns is by rank, since we’re all in about the same state medically: stuck in our glacial beds, envisioning in our mind’s eye the scenes the person with the active screen describes.

Cmdr. Rudd didn’t last a week. I’d never say it aloud, but I was glad in a selfish way, because his reports were lackluster. Probably knew he wasn’t going to make it, so the sat-views of Earth didn’t inspire any hope in him.

For me, the only thing that makes the white pain bearable is the certainty that I’m heading home. Got to hang on a few more days. They’ll spot us approaching earth orbit, wonder why we don’t answer trafcon, and when they dock to investigate, they’ll find eleven popsicles. Or whoever’s left. And they’ll bring us up to normtemp and I swear I’ll kiss the tech, I’ll kiss the trafcop, I’ll kiss the warmth. I’ll make love to it.

After Cmdr. Rudd, came Lt. Vidyananda’s turn to see Earth. He just groaned a lot. Too sick to work the optics. He passed the viewer on to Abdullah, and the old imam was wonderful. A real poet. I loved his stories of history and literature from peoples of different lands as he aimed the telescopes down from high above. He got to be a master at it, zooming in on details, even describing the architecture: Stonehenge, Angkor Wat, New Los Angeles. It really helped—I never thought religion and mythology could be so moving. My eyes froze shut with tears and I had to blink to break the ice—sizzling skewer blinks.

Next up was Clewiston, who surprised me. Always thought the guy was about as interesting as a meteoroid drill, but he Q-leaped as he described the wildlife he surveyed on magniview. I learned that a giraffe and a rizora don’t just vaguely look alike; except for brain size, their internal structures are nearly congruent, an example of convergent evolution.

“It is not entirely incorrect to think of rizorae as distant genetic cousins to Terran giraffes, but of course, with an intelligence approaching that of Homo sapiens,” he said. Then he launched into an explanation of natural selection on Proxima A that would account for a population of intelligent giraffe-analogs. That led into his DNA-as-God metaphysics, and for the first time the Cult of the Cosmic Seed made sense to me. “And the Code became flesh…the Instructions lie within…A-T-G-C spells LIFE,” and the rest. If you ignored his pompous diction—who but a prof says “not entirely incorrect”?—Clewiston was inspiring. Guess he felt energized knowing his audience was captive.

Next was Bosch, the geologist. Land masses and planetary forces and the runaway greenhouse effect. Told about Manhattan sinking and the destruction of L.A., but his vocal cords were frost damaged and I couldn’t make out most of it.

And now, Brye. Was hoping she’d make it home, get to know her. I’ve enjoyed her vivid descriptions of sea life that she’s managed to track on sonar-view. Learned more in a week listening to her than on two short treks studying oceanography on my own. Homeworld, I’ll take up diving, like we talked about—but scuba, no artificial gills. Sorry, but I think it makes her throat a bit creepy.

My turn coming soon. My “show.” Don’t want to let the other 10 down. Seeing Earth through each pair of eyes has kept us going. Thing is, I’m no scholar or scientist or philosopher. I’m a techie. Photovoltaic super-conductive paints—hell, half the time the data bores me. I’ll go with what I decided when I listened to the imam. The way he made me feel each scene.

I’ll talk about sonic ball. Not profound, I know, but when the televiewer pops up on my screen I’ll tap TV satellites until I find a game in action. I want to tell the others exactly how it feels to play sonic ball on a glowing summer afternoon, on the warm, green Earth. How my dad was second hover-man for the Nukes, twice MVP in the Central American League, Dome-of-Fame nominee. I’ll share my joy from 86 years ago, long forgotten.

“And that, friends…” Brye is barely audible. “…is why I call her Planet Ocean…mother of all the loves of my life.”

She’s wheezing. Get set. I’m next.

“My time is up… entering the water for one last dive… Godspeed to you all. Transferring viewer to techmaster Ortega.” ______________________________________________________

Absolute shock.

That was first. Then terror and rage erupted in a scream that scorched my lungs. Finally, helplessness swallowed me, snuffed my grief under a blanket of snow.

Not till then did I begin to understand the beauty of it, the artistry of human kindness.

I worked my jaw. Shooting flames. But now I can talk clearly enough to be understood with a molten tongue, and the flames die as I die, but the images remain vivid and whole.

“I can see the sweat dripping off Manny O’s cheekbones. He’s brandishing the sonic as if he’s challenging the sun that glares so hot and bright on this perfect Panamanian afternoon. Left turbo fires the ball—BLAM!—Ortega knocks it high over the second buoy. It’s up, up—a hoverman streaks up to intercept—no, folks, it’s outathere! Ortega is rounding buoy three, taking his time now, gliding down to home, wearing that famous solar smile. Keep your eye on him, watch for—Ho!—his victory roll.”

The pictures from home are lit up like noon in the tropics, even with my eyelids frozen shut. I can see the veins bulging on the backs of my dad’s big hands, the gnats he sweeps away from his green eyes.

Navcom data shows we’re still out-trekking, away from Earth; nothing on the view screen but the clear black void of space. Yet the memories are flowing. I can see fine.

* * *

Published on May 03, 2014 19:45

Pictures from Home

Twelve left.

Twelve left.Twelve out of 968, homeward bound.

Eleven, really, because Lt. Brye isn’t going to last much longer.

About a hundred beds failed outright when the system crashed. Those in stasis slipped into death; not too far to fall from minimally alive—and no pain. Those were the lucky ones. Other beds partly revived us survivors.

Obviously nobody made it to normtemp or he’d have done an M.O. on the program and thawed the rest of us: eleven trapped in sub-wake; Brye fading so fast now I don’t count her.

“Bingo. Got an open channel on a recon-sat above the Florida Keys.” The lieutenant is whispering hoarsely into her com, slurring her words. Her voice is weakening, though her jaw muscles and tongue are probably long past the stage of searing pain.

“Magnificent,” she says. “The Keys are shimmering white like a string of pearls against the blue Atlantic. Hold for zoom. Ah… I see a boat… yes, locked on a dive boat; she’s heading out to a coral reef. Looks like seven, make that eight divers aboard. What a day. Golden sun, water so clear I can make out a school of barracudas. I dove this reef myself, many years ago. Got a sunken hydrofoil lying on its side, home to a nurse shark named Mighty Mom.”

She’s talking about Sugar Reef, where she made her first open-water dive. I’ve heard this story. I’m amazed she was able to find the very reef. Mighty Mom. How her buddies laughed their butts off when she scrambled back on deck. Ow, it really burns when I smile. Tough it out, limber up—I’m next on the intercom.

Brye is good. For a few moments I had forgotten the constant, bottomless cold. What the oldspacers call white pain. Like my brain is floating in a bucket of CryoGen and my spinal cord is a branching tree of ice. Can’t move a stiff finger without feeling the scorching lava of a thousand cell walls bursting. But as soon as the burning subsides, the infinite chill swallows the site where the fire flared, and all is uniformly frigid again, a polar ocean.

Sub-wake under normal conditions is no joy drug. I hated it when it lasted, what?—all of ten minutes? A freezing zone to be endured while dropping to the blank night of stasis, and suffered again on the rise back to normtemp.

“A controlled cooling to near-death,” instructor Barnes had said. Right. More like the science of turning blood to slush. “The ache is minimized by remaining perfectly motionless,” he said in my earpiece on that first drop. “Fight it, and it will injure or even kill you. You must lie absolutely still and let the freeze take you—in which case, deaths are rare.” Bastard loved to scare us.

We’d learned in lectures that the early crews used anesthesia to skip the agony phase of cryostasis. But the failure-to-wake ratio was around eight percent then; more for long trips, New Beijing and farther. They found out when you bypass the pain of freezing, the body and brain don’t adjust as efficiently to stasis as when you consciously penguin down through the stages. Full penguin knocks the deadsleeps to less than one-tenth of one percent.

Cold or old, they say. Wish now I had chosen to age. Some manage okay on shorter treks. Mostly married crew who want to have the same number of wrinkles as their mates when they get home. Or brainiacs who spend the trek studying—three or four Ph.D.’s and counting. But a seven-year roundtrip is definitely pushing it; I’ve never heard of anyone who could live in a tin can that long and not start clawing at the air locks.

We all chose stasis. Colonists dropped in the first week. Crew two weeks later. System crashed almost immediately, less than a month out-trek. Eighteen initial survivors of the 32-person crew, but not one of the more than 900 colonists. Twelve—minus one—crewmembers now remaining, damned to icy purgatory. Not the hot bliss of hell where red coals bake your bones, but this blue-black arctic winter without a sun. And you can’t just pass out and sleep through it; sub-wake stims the brain so that sleep is physiologically impossible. Great gimmick for a horror sensum, right? But the holo-theaters would have to carry medical insurance, like for xenoporn; only in this case, the audience would get psychosomatic frostbite, not cardiac arrest from climaxing with a nerve-orchid.

Five weeks since Capt. Ochiba sub-woke and died the same day, a mayfly. But she lived long enough to get a fix on our position and lock the navcom on Earth base. The ship immediately began decelerating, but it took a couple weeks to reverse course without pulling too many G’s or expending too much fuel. Now we’re accelerating toward home and of course we’ll have to brake again when we get there.

The captain announced she had opened an omni-channel link and the bright blue curve of Earth filled her screen. The captain is a hero. No question. She had to have struggled in excruciating pain; just moving her fingers over the armrest keys must have felt like napalm bubbling her flesh. If she hadn’t laid in a course for home, I’m sure I’d be dead by now in my freezing coffin. She transferred the satellite link to Rudd’s screen and said something in Japanese—I caught “Sayonara”—before the tissue damage finished her.

My guess is Christian terrorists planted a timed virus in our A.I. mainframe. Whatever crashed the system screwed the com network—the satellite omni-link can display on only one computer at a time. So everybody has to wait in line to view home from his own screen. The obvious way to take turns is by rank, since we’re all in about the same state medically: stuck in our glacial beds, envisioning in our mind’s eye the scenes the person with the active screen describes.

Cmdr. Rudd didn’t last a week. I’d never say it aloud, but I was glad in a selfish way, because his reports were lackluster. Probably knew he wasn’t going to make it, so the sat-views of Earth didn’t inspire any hope in him.

For me, the only thing that makes the white pain bearable is the certainty that I’m heading home. Got to hang on a few more days. They’ll spot us approaching earth orbit, wonder why we don’t answer trafcon, and when they dock to investigate, they’ll find eleven popsicles. Or whoever’s left. And they’ll bring us up to normtemp and I swear I’ll kiss the tech, I’ll kiss the trafcop, I’ll kiss the warmth. I’ll make love to it.

After Cmdr. Rudd, came Lt. Vidyananda’s turn to see Earth. He just groaned a lot. Too sick to work the optics. He passed the viewer on to Abdullah, and the old imam was wonderful. A real poet. I loved his stories of history and literature from peoples of different lands as he aimed the telescopes down from high above. He got to be a master at it, zooming in on details, even describing the architecture: Stonehenge, Angkor Wat, New Los Angeles. It really helped—I never thought religion and mythology could be so moving. My eyes froze shut with tears and I had to blink to break the ice—sizzling skewer blinks.

Next up was Clewiston, who surprised me. Always thought the guy was about as interesting as a meteoroid drill, but he Q-leaped as he described the wildlife he surveyed on magniview. I learned that a giraffe and a rizora don’t just vaguely look alike; except for brain size, their internal structures are nearly congruent, an example of convergent evolution.

“It is not entirely incorrect to think of rizorae as distant genetic cousins to Terran giraffes, but of course, with an intelligence approaching that of Homo sapiens,” he said. Then he launched into an explanation of natural selection on Proxima A that would account for a population of intelligent giraffe-analogs. That led into his DNA-as-God metaphysics, and for the first time the Cult of the Cosmic Seed made sense to me. “And the Code became flesh…the Instructions lie within…A-T-G-C spells LIFE,” and the rest. If you ignored his pompous diction—who but a prof says “not entirely incorrect”?—Clewiston was inspiring. Guess he felt energized knowing his audience was captive.

Next was Bosch, the geologist. Land masses and planetary forces and the runaway greenhouse effect. Told about Manhattan sinking and the destruction of L.A., but his vocal cords were frost damaged and I couldn’t make out most of it.

And now, Brye. Was hoping she’d make it home, get to know her. I’ve enjoyed her vivid descriptions of sea life that she’s managed to track on sonar-view. Learned more in a week listening to her than on two short treks studying oceanography on my own. Homeworld, I’ll take up diving, like we talked about—but scuba, no artificial gills. Sorry, but I think it makes her throat a bit creepy.

My turn coming soon. My “show.” Don’t want to let the other 10 down. Seeing Earth through each pair of eyes has kept us going. Thing is, I’m no scholar or scientist or philosopher. I’m a techie. Photovoltaic super-conductive paints—hell, half the time the data bores me. I’ll go with what I decided when I listened to the imam. The way he made me feel each scene.

I’ll talk about sonic ball. Not profound, I know, but when the televiewer pops up on my screen I’ll tap TV satellites until I find a game in action. I want to tell the others exactly how it feels to play sonic ball on a glowing summer afternoon, on the warm, green Earth. How my dad was second hover-man for the Nukes, twice MVP in the Central American League, Dome-of-Fame nominee. I’ll share my joy from 86 years ago, long forgotten.

“And that, friends…” Brye is barely audible. “…is why I call her Planet Ocean…mother of all the loves of my life.”

She’s wheezing. Get set. I’m next.

“My time is up… entering the water for one last dive… Godspeed to you all. Transferring viewer to techmaster Ortega.” ______________________________________________________

Absolute shock.

That was first. Then terror and rage erupted in a scream that scorched my lungs. Finally, helplessness swallowed me, snuffed my grief under a blanket of snow.

Not till then did I begin to understand the beauty of it, the artistry of human kindness.

I worked my jaw. Shooting flames. But now I can talk clearly enough to be understood with a molten tongue, and the flames die as I die, but the images remain vivid and whole.

“I can see the sweat dripping off Manny O’s cheekbones. He’s brandishing the sonic as if he’s challenging the sun that glares so hot and bright on this perfect Panamanian afternoon. Left turbo fires the ball—BLAM!—Ortega knocks it high over the second buoy. It’s up, up—a hoverman streaks up to intercept—no, folks, it’s outathere! Ortega is rounding buoy three, taking his time now, gliding down to home, wearing that famous solar smile. Keep your eye on him, watch for—Ho!—his victory roll.”

The pictures from home are lit up like noon in the tropics, even with my eyelids frozen shut. I can see the veins bulging on the backs of my dad’s big hands, the gnats he sweeps away from his green eyes.

Navcom data shows we’re still out-trekking, away from Earth; nothing on the view screen but the clear black void of space. Yet the memories are flowing. I can see fine.

* * *

Published on May 03, 2014 19:45

April 17, 2014

Well, What Do You Know?

Beginning writers repeatedly encounter the advice, “Write what you know.” Of course, if writers heeded this counsel narrowly and reported only what they have directly experienced, historical fiction and fantasy tales would vanish along with the best of the world’s literature.

Beginning writers repeatedly encounter the advice, “Write what you know.” Of course, if writers heeded this counsel narrowly and reported only what they have directly experienced, historical fiction and fantasy tales would vanish along with the best of the world’s literature. After all, Jamie McGuire is not an alpha male and should not be privy to the secret emotions of her tattooed bad boy (Beautiful Disaster); Arthur Golden is not a Japanese woman and should not have given us his intimate portrait of “the floating world” (Memoirs of a Geisha); and Stephen Crane, who never fought on a Civil War battlefield, should not have penned his tale of cowardice and heroism—acclaimed for its realism (The Red Badge of Courage).

Furthermore, “Write what you know” might even be bad advice. Fiction by students in MFA writing programs is notoriously autobiographical or even narcissistic, starring penniless grad students awkwardly exploring their sexuality and the meaning of adult life.So let’s take a closer look at the truism, “Write what you know.”

To begin, what do you know? Well, you know yourself. And you are already a complex of selves. You play plenty of roles in the daily theater of your life, such as daughter, sister, friend, lover, worker, soccer mom. But are you not also the 8-year-old who wanted to be a cowgirl, the high school bookworm who hung out with the misfits, the college sophomore who read Sylva Plath, the woman who fantasizes what it would be like to spend a weekend in Paris with that hunky guy in line for a latte? Without being overtly nuts, you manage to include all these characters, like the population of a small town. A Jungian psychologist would say you contain everyone you have ever been, as well as everyone you have tried to be. You are, in this sense, even the person you avoided becoming or the one you are scared of being. All of these characters are “you”—and you know them intimately.

Secondly, the idea “to know” takes on broader meaning when you consider that you “know” in wide-ranging ways. You know in your head, through education; you know in your body, through living; you know in your heart, through empathy. You know how people walk and talk and laugh and interact because you are a seasoned people watcher and eavesdropper (and, if not, please take up those vices).

To know is a matter of paying attention. Being the kind of observer who misses nothing is an essential habit for writers. A person might sleepwalk through life, and having lived for ten years in Istanbul, be unable to offer a vivid description of the unique sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures of the ancient Turkish city, while a more perceptive person could visit the city for a week and then write a scene that makes you feel as if you are standing under the car-sized stones of the Roman aqueduct.

Research is another valid way of knowing. You can convincingly place a scene within a detailed setting that you have never even visited—let’s again say Istanbul—but you must first familiarize yourself with Istanbul through its history and culture, economics, statistics, street maps, photos, travel and restaurant and night life guides, and nature guides.

Of course, research has its limits. I once began writing a novel about a woman who flew a Mustang in the Reno Air Races. I did my research, including studying a mechanical manual and building a large-scale model of the Mustang. But it finally came down to this: I am not a pilot. A few chapters into the story, I realized it was not going to feel authentic. The project is on hold (at least until I can get out to Reno and actually ride with a pilot in an air race).

What my story would have lacked is the sense of immediacy revealed by little details that only experts know. Every sport and occupation, from ice skating to brain surgery, has these bits of arcana, beginning with a peculiar jargon. If you conduct interviews as part of your research (always recommended), ask your sources to provide you with these revealing particulars: “Please take a moment to think of something special you know about [skydiving, bronco riding, performing a C-section] that the rest of us couldn’t even begin to guess.”

So “Write what you know” remains good advice when it is not interpreted narrowly. Mine the deep strata of what you already know and what you can learn. And if you are an expert in a particular field, consider how you might exploit your hard-won knowledge in your fiction.

Published on April 17, 2014 08:11

February 24, 2014

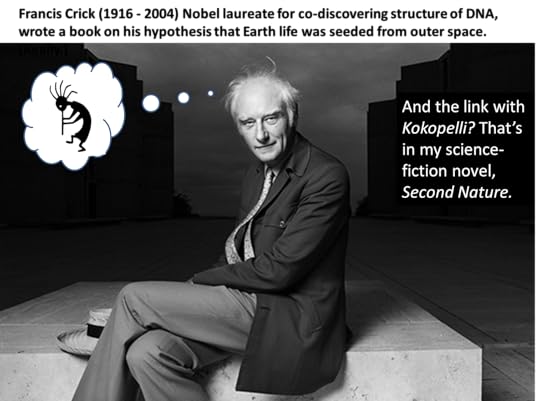

Second Nature: a love story with the heart of a fairy ta...

Published on February 24, 2014 11:40

Selling Storytelling

A smattering of notes and advice on the craft of writing stories that sell.

- Mark Canter's profile

- 16 followers