Grace Lees-Maffei's Blog

January 16, 2025

The Design History Reader, Second Edition (2025)

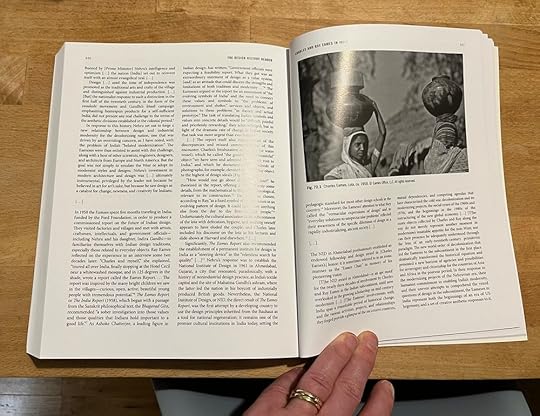

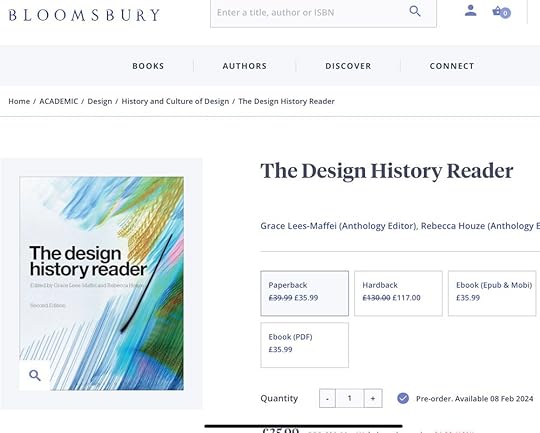

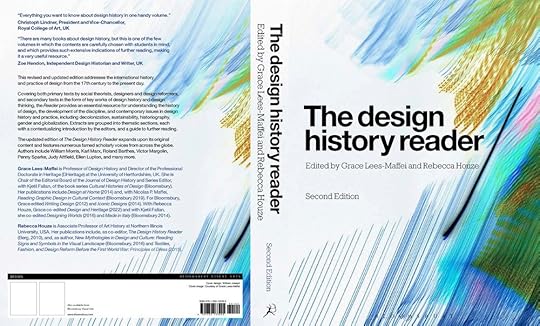

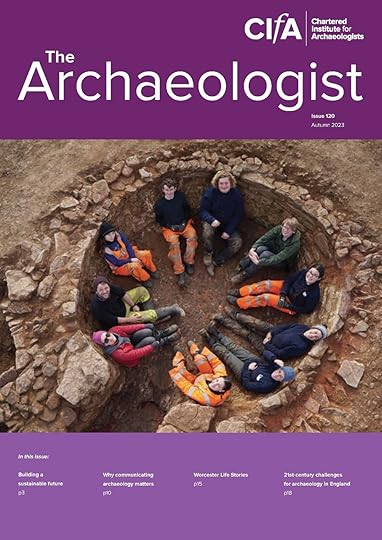

Along with my co-editor Prof Rebecca Houze (Northern Illinois University, USA), I am delighted to introduce the second edition, fully revised and expanded, of our book, The Design History Reader, which is published by Bloomsbury (2025). Thanks to all those who read the first edition, cited it, and added it to course curricula internationally, we are now able to launch a second, updated, edition. You might recognise the cover, a colour inversion of the photograph I took for first edition.

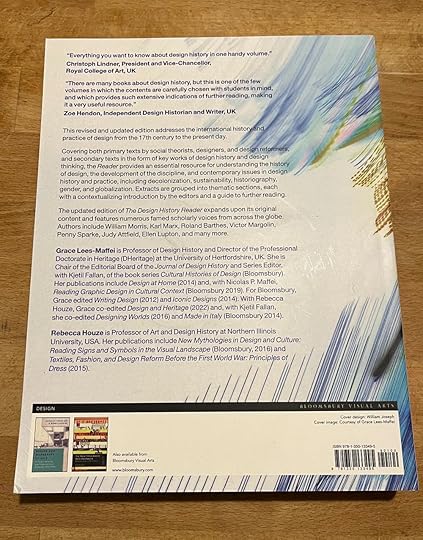

The first edition was published way back in 2010. Thie new edition is revised and updated in myriad ways, including through the addition of texts published since 2010, and a new structure. Like the first edition, this new edition addresses the international history and practice of design from the 17th century to the present day. Covering both primary texts by social theorists, designers and design reformers, and secondary texts in the form of key works of design history and design thinking, the Reader provides an essential resource for understanding the history of design, the development of the discipline, and contemporary issues in design history and practice, including decolonization, sustainability, historiography, gender and globalization. Extracts are grouped into thematic sections, each with a contextualising introduction by the editors, and guides to further reading. The revised and expanded second edition offers more coverage of, for example, digital design, decolonising design, sex, gender, sexuality and design, and environmental histories of design.

EventsWe will be introducing the second, revised and expanded, edition of The Design History Reader, including details about our editorial approaches and difficult decisions at the following events:

Thursday 13th February 2025, 4.30 pm: Bloomsbury launch reception at the College Art Association annual conference book fair, New York City, USA

Saturday 15th February 2025, 9 am to 10.30 am: Talk by the editors at the Design History Society panel, ‘Teaching Design History’, College Art Association annual conference book fair, New York City, USA

10-12 October 2025, time TBC: Talk by the editors at ‘Cultures of Design’, ICDHS conference, Department of Design, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, India.

Praise for the Second Edition

Everything you want to know about design history in one handy volume.

Christoph Lindner, President and Vice-Chancellor, Royal College of Art, UK

There are many books about design history, but this is one of the few volumes in which the contents are carefully chosen with students in mind, and which provides such extensive indications of further reading, making it a very useful resource.

Zoe Hendon, Independent Design Historian and Writer, UK

Read more here!

The new edition of The Design History Reader is available now from Bloomsbury, and from your favourite bookseller.

ContentsList of Illustrations

Notes on Contributors

Preface to the Second Edition

Acknowledgements

General Introduction, Grace Lees-Maffei

Part One: Histories

Introduction to Part One

SECTION 1: NEW DESIGNERS 1676-1820

Introduction

1. An Indian Basket, Providence, Rhode Island, 1676, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

2. A Slipware Dish by Samuel Malkin: An Analysis of Vernacular Design, Darron Dean

3. Of The Division of Labour, from An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith

4. The Wedgwood Slave Medallion: Values in Eighteenth-century Design, Mary Guyatt

5. Manufacturing, Consumption and Design in Eighteenth-century England, John Styles

Guide to Further Reading for Section 1

SECTION 2: DESIGN REFORM 1820-1910

Introduction

6. Science, Industry, and Art, Gottfried Semper

7. The Nature of Gothic, John Ruskin

8. The Ideal Book, William Morris

9. The 'American System' and Mass-Production, from Industrial Design, John Heskett

10. The 1900 Paris Exposition, from Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France, Debora Silverman

11. The Art and Craft of the Machine, Frank Lloyd Wright

Guide to Further Reading for Section 2

SECTION 3: MODERNISMS 1908-1950

Introduction

12. Introduction to Modernism in Design, Paul Greenhalgh

13. Ornament and Crime, Adolf Loos

14. Werkbund Theses and Antitheses, Hermann Muthesius and Henry van de Velde

15. The Modern Movement before Nineteen-fourteen, from Pioneers of Modern Design, Nikolaus Pevsner

16. From Workshop to Laboratory, from The Bauhaus Reassessed, Gillian Naylor

17. Ambiguously Modern: Art Deco in Latin America, Rafael Cardoso

18. The Search for an American Design Aesthetic: from Art Deco to Streamlining, Nicolas P. Maffei

Guide to Further Reading for Section 3

SECTION 4: WAR, RECOVERY, AND DECOLONIZATION 1943-1970

Introduction

19. Gandhi and Khadi, the Fabric of Indian Independence, Susan S. Bean

20. Progress through Prosthetics, Bess Williamson

21. 'Here Is the Modern World Itself': The Festival of Britain's Representations of the Future

Becky Conekin

22. Isotype in Africa: Gold Coast, Sierra Leone, and the Western Region of Nigeria, 1952-8, Eric Kindel

23. The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution

Susan E. Reid

24. All That Glitters is Not Stainless, Peter Reyner Banham

Guide to Further Reading for Section 4

SECTION 5: POSTMODERNISMS 1967-2006

Introduction

25. A Significance for A & P Parking Lots, or Learning from Las Vegas, from Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form, Robert Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown and Steven Izenour

26. The Ecstasy of Communication, Jean Baudrillard

27. There is No Kitsch, There is Only Design! Gert Selle

28. Deconstruction and Graphic Design: History Meets Theory, Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller

29. What was Philippe Starck thinking of? Peter Lloyd and Dirk Snelders

30. Fabricating Identities: Survival and the Imagination in Jamaican Dancehall Culture, Bibi Bakare-Yusuf

Guide to Further Reading for Section 5

SECTION 6: SUSTAINABLE DESIGN 1960-2020

Introduction

31. Spaceship Earth, from Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, R. Buckminster Fuller

32. Do-It-Yourself Murder: the Social and Moral Responsibility of the Designer, from Design for the Real World, Victor Papanek

33. The Hannover Principles. Design for Sustainability, William McDonough and Michael Braungart

34. Material Doubts and Plastic Fallout, from American Plastic, Jeffrey L. Meikle

35. Redefining Rubbish: Commodity Disposal and Sourcing, from Second-Hand Cultures, Nicky Gregson and Louise Crewe

36. Green Marketing on the Go: A Cup of Coffee Opening Up Vistas on a Train Journey, Karin Wagner

37. Environmental Histories of Design: Towards a New Research Agenda, Kjetil Fallan and Finn Arne Jørgensen

Guide to Further Reading for Section 6

Part Two: Methods and Themes

Introduction to Part Two

SECTION 7: FOUNDATIONS, DEBATES, HISTORIOGRAPHY, 1980-1995

Introduction

38. Taking Stock in Design History, Fran Hannah and Tim Putnam

39. The State of Design History, Part I: Mapping the Field, Clive Dilnot

40. Design History and the History of Design, John A. Walker

41. Design History or Design Studies: Subject Matter and Methods, Victor Margolin

42. Resisting Colonization: Design History Has Its Own Identity, Jonathan M. Woodham

Guide to Further Reading for Section 7

SECTION 8: MODES OF PRODUCTION

Introduction

43. Faith, Form and Finish: Shaker Furniture in Context, Jean M. Burks

44. How the Refrigerator Got Its Hum, Ruth Schwartz Cowan

45. 'Mass Customization' and 'Flexible/Agile Manufacturing', from Designing Things: A Critical Introduction to the Culture of Objects, Prasad Boradkar

46. Imagined Machines, from Delete: A Design History of Computer Vapourware, Paul Atkinson.

47. Susan Kare: Design Icon, Eric S. Hintz

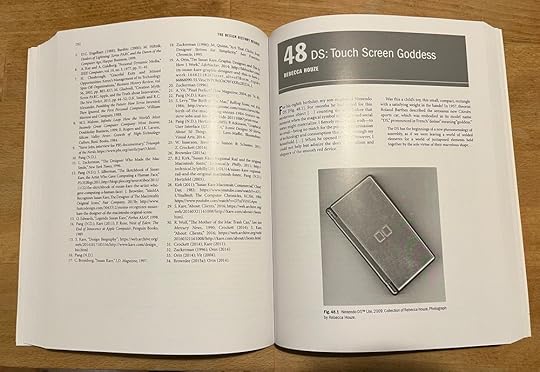

48. DS Touch Screen Goddess, from New Mythologies in Design and Culture: Reading Signs and Symbols in the Visual Landscape, Rebecca Houze

Guide to Further Reading for Section 8

SECTION 9: PRACTICES OF CONSUMPTION

Introduction

49. The Fetishism of the Commodity and its Secret, from Capital. A Critique of Political Economy, Karl Marx

50. Conspicuous Consumption, from The Theory of the Leisure Class, Thorstein Veblen

51. Myth Today and The New Citroën, from Mythologies, Roland Barthes

52. Introduction and The Sense of Distinction, from Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Pierre Bourdieu

53. 'Parties Are the Answer': The Ascent of the Tupperware Party, Alison Clarke

54. The Revolution Will Be Marketed: American Corporations and Black Consumers during the 1960s, Robert E. Weems, Jr.

55. Object as Image: The Italian Scooter Cycle, Dick Hebdige

56. Integrative Practice: Oral History, Dress and Disability Studies, Liz Linthicum

Guide to Further Reading for Section 9

SECTION 10: CHANNELS OF MEDIATION

Introduction

57. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin

58. Advertising, Mother of Graphic Design, Steven Heller

59. 'Decorators May Be Compared to Doctors' An Analysis of Rhoda and Agnes Garrett's Suggestions For House Decoration In Painting, Woodwork And Furniture (1876), Emma Ferry

60. The Production-Consumption-Mediation Paradigm, Grace Lees-Maffei

61. A Design for the Real World? (1968-1974), from Designing Disability: Symbols, Space, and Society, Elizabeth Guffey

Guide to Further Reading for Section 10

SECTION 11: NEGOTIATING GENDER, SEXUALITY AND DESIGN

Introduction

62. FORM/female FOLLOWS FUNCTION/male: Feminist Critiques of Design, Judy Attfield

63. The Architect's Wife, Introduction to As Long As Its Pink, Penny Sparke

64. Self-Made Motormen: The Material Construction of Working-class Masculine Identities through Car Modification, Andrew Bengry-Howell and Christine Griffin

65. Screening Sexuality: Eileen Gray and Romaine Brooks, from Eileen Gray and the Design of Sapphic Modernity, Jasmine Rault

66. 'The Pink Elephant in the Room: What Ever Happened to Queer Theory in the Study of Interior Design 25 Years on?' John Potvin

Guide to Further Reading for Section 11

SECTION 12: LOCAL/REGIONAL/NATIONAL/GLOBAL: DECOLONIZING DESIGN

Introduction

67. Towards Global Design History, Sarah Teasley, Giorgio Riello, and Glenn Adamson

68. Furniture Design and Colonialism: Negotiating Relationships between Britain and Australia, 1880-1901, Tracey Avery

69. “From Baby's First Bath:” Kao Soap and Modern Japanese Commercial Design, Gennifer Weisenfeld

70. Land Rover and Colonial-Style Adventure, Jeanne Van Eeden

71. Swoosh Identity: Recontextualizations in Haiti and Romania, Paul B. Bick and Sorina Chiper72. Charles and Ray Eames in India, Saloni Mathur

73. The Decolonized Quadruple Bottom Line: A Framework for Developing Indigenous Innovation, Fonda Walters and John Takamura

74. 'The Portable Flush Toilet: From Camping Accessory to Protest Totem', Nadine Botha.

Guide to Further Reading for Section 12

Bibliography

Index

January 10, 2025

Goodbye 2024, Hello 2025

At the beginning of 2024, I was wrestling with health complications arising from cancer treatment in 2023. My experience has placed wellbeing and quality of life at the top of my agenda. During the year, I developed encouraging new patterns of productivity that will stand me in good stead for 2025 and beyond.

2024 in RetrospectThe professional doctorate in heritage, DHeritage, which I direct at the University of Hertfordshire, celebrated its tenth anniversary in 2024. I blogged about this early in the year here, and in October, I convened a 10th anniversary DHeritage symposium. It began with talks explaining the genesis of the programme and then showcased a wide range of student research before moving to snapshots of staff research and a wrap-up discussion. It is so important to reflect on and celebrate such milestones.

In February 2024, I attended a moving celebration of the life and work of design historian Charlotte Benton, convened by Emeritus Professor Tim Benton at the University of Cambridge. I reflected on Charlotte’s life there and here and Jonathan Woodham did so in the pages of the Journal of Design History, to which Charlotte contributed so much as a founder, editor and author. As current Chair of that journal, I am glad to have appointed Dr Harriet Atkinson (University of Brighton) as its first Obituaries Editor. Harriet has worked with tact and sensitivity on a series of obituaries which recognise that after half a century of design history, we are and will be saying goodbye to an increasing number of design historians. Recognising their achievements and legacies is vital.

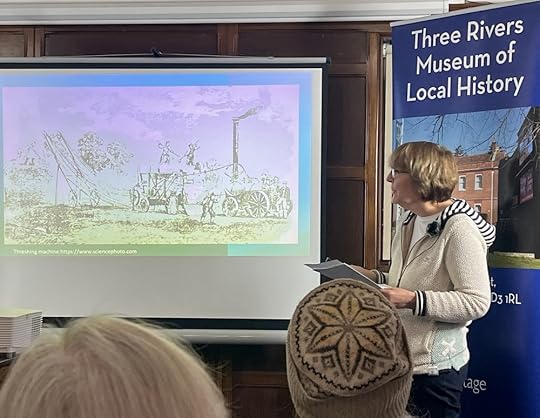

I hope this blog makes clear the fact that I really like my job. Even so, how refreshing it is to escape desks and books for study visits with the DHeritage students and staff, learning together in the field! In April 2024, I was delighted to attend a launch symposium for Dr Sue Davies’ HARVEST project on farming, food and sustainability at the Three Rivers Museum in Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire. In May we visited Chiltern Open Air Museum, for a day organised by DHeritage student Sarah Fitzpatrick who has links with COAM as a Trustee. The heritage experience at COAM begins with the Victorian cast iron toilet block and continues over many acres of parkland populated with historic buildings from a recreated Iron Age house to a prefabricated bungalow. The DHeritage visit focussed on COAM’s wellbeing walks in which the act of moving together through the landscape and buildings creates a context for conversation. We learned a great deal from undertaking the guided wellbeing walks: the walking, the landscape, the buildings and the conversation are all beneficial to wellbeing. COAM’s wellbeing walks were devised and managed by Jacqui Gellman. Jacqui was kind enough to join us later for a workshop on heritage and wellbeing.

Attending the Design History Society annual conference in September always offers a great start to the academic year. The 2024 conference, Border Control, was convened by a team at the University for the Creative Arts, Canterbury. As well as listening to and enjoying many talks, I chaired a meeting of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Design History, gave a well-received paper about gloves, chaired the DHS AGM and a meeting of the DHS Executive Committee in place of DHS Chair, Dr Sally-Anne Huxtable, and hosted a reception for the Journal. I also enjoyed a walking tour of the city, and a visit to the amazing Cathedral.

Across the autumn months, I drafted an article that I had been invited to contribute to a special issue in progress. The article picks up where my 2008 article on histories of the professionalisation of interior design left off, and develops a talk I gave in 2023 at the University of Antwerp. I am expecting to revise it for publication early this year.

Also in the autumn, I focussed on two PhD examinations, one in the UK and one in Ghent. I can’t share the work examined at this point, but I can say that I very much enjoyed visiting Ghent, meeting with colleagues there and seeing the Museum of Industry among other, older, sights. I am looking forward to returning to Ghent for a public defence in March when I hope to say more about the research examined. Also in March, I have been invited to examine a PhD in the US. Examining doctoral research is a highlight of my work, as each project is unique and fascinating.

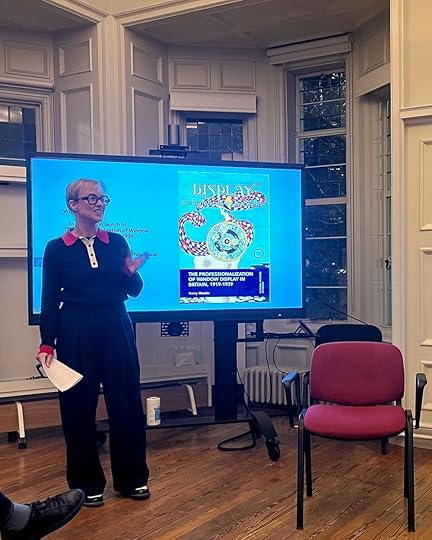

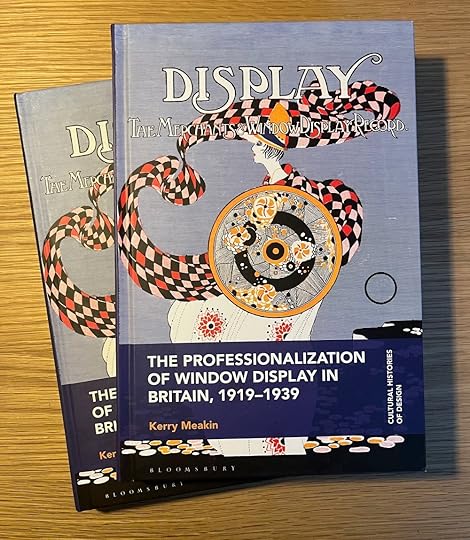

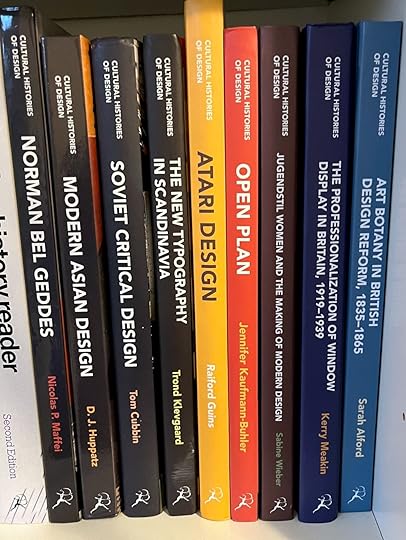

That is also true of the books that I help develop in Cultural Histories of Design, a series for Bloomsbury that I co-edit with Prof Kjetil Fallan (University of Oslo). I was delighted to attend a book launch for Dr Kerry Meakin’s CHoD book The Professionalisation of Window Display, 1919-1939 hosted by Dr Vanessa Vanden Bergh at Chelsea College of Arts, University of the Arts London. CHoD was conceived in 2013 and saw its first books published in in winter 2017/18. I will reflect more on its development here in due course.

My working year ended on high when I gave an invited talk, ‘Pugin to Papercuts’, for The Pugin Society annual general meeting, which took place at the Art Workers’ Guild in Queen Square, London. In my talk, I shared part of a chapter of The Hand Book, on the ways in which we can read contemporary fine art and craft practice through the ideas of the 19th-century design reformers, Pugin, Ruskin and Morris.

The Year Ahead

2025 looks very promising across all my areas of activity. In February, I will give a talk at the College Art Association annual conference in New York. My talk is a joint presentation, with Rebecca Houze, about the process of editing our revised and expanded second edition of The Design History Reader. Our talk is part of a panel about teaching design history, sponsored by the CAA affiliate, the Design History Society. Based on my experience of meeting delegates at several previous CAA conferences, I know this is a topic of interest to many of them who may not be trained as design historians but nevertheless find themselves charged with teaching design history.

DHeritage will return to Three Rivers Museum in February for a study visit in preparation for Dr Sue Davies’ workshop on using archives to address contemporary issues, as she has done in her HARVEST project. In April, DHeritage will enjoy a visit led by DHeritage student Claire Slack with Dr Ceri Houlbrook and Prof Owen Davies to Wiltshire Museum. We will see the Wessex Folk touring exhibition that Claire has worked on and make an afternoon trip to Avebury to experience the stones and discuss site management and folk belief. This is in preparation for a workshop on Folklore and Tourism in June.

This year’s DHS conference is planned to take place in September in Ankara, Turkey. The DHS conference is usually a highlight of my working year, in which I often share my research as a speaker, Chair a meeting of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Design History, meet readers, authors and potential authors at a reception sponsored by our publishers, Oxford University Press, and share my work as Trustee of the Design History Society with members at the AGM. Also on the conference circuit this year, I have served on the Scientific Committee of ‘Cultures of Design’, the 2025 ICDHS conference. I hope to be able to attend the conference in New Delhi, India in October.

Closer to home, I continue working on The Hand Book, a long-standing, frankly overdue task that continues to absorb me. I will finish it one day, soon! I start 2025 feeling energised and optimistic; I can ask for nothing more.

December 10, 2024

Pugin to Papercuts: A Talk for the Pugin Society

I’m delighted to have been invited by the Pugin Society to give its 2024 AGM lecture at the Art Workers’ Guild, 6 Queen Square, London. I last met up with the Pugin Society when its committee member for Web and Print Design, Dr Jamie Jacobs, gave a lecture at the Palace of Westminster drawing on her PhD on Pugin at the University of Kent, which I supervised. I wrote about Dr Jacob’s talk here. Dr Jacobs has now kindly suggested me as a speaker, for the Pugin Society. She and secretary David Bushell felt I might have something up my sleeve that I could share with the Society and they were right. I am grateful for this opportunity to talk about an aspect of my research for The Hand Book, a design history of hands, with a group of Pugin experts.

The title for my talk is “Pugin to Papercuts, Ruskin to Ryan, Walthamstow to Wandsworth: Design Reform and Socially-Engaged Contemporary Art Practice.” While this title displays perhaps too much enthusiasm for alliteration, it at least communicates the links I’m making. My talk draws on the ideas of three influential nineteenth-century design reformers, AWN Pugin, John Ruskin and William Morris, to examine two instances of 21st century creative practice: the socially and politically engaged papercuts of Rob Ryan, and the Wandsworth Quilt, made by prisoners for the V&A collection. The location for the lecture is extremely fitting because two of the figures that I will discuss, William Morris and Rob Ryan, were/are Masters of the Art Workers Guild.

Pugin Society members will know better than most that Pugin was an early critic of the effects of industrial manufacture on design. He dictated that only the ‘essential form be decorated,’ that flat patterns should be used instead of illusionistic representations.[1] Although Ruskin claimed never to have read Pugin, and criticised him in print, his influence on Ruskin’s thinking is clear.[2] Ruskin’s ‘On the Nature of the Gothic’ (1853) decried the dehumanising effects of industrialisation. Ruskin responds directly to Adam Smith’s writing on the division of labor: ‘It is not, truly speaking, the labour that is divided; but the men: Divided into mere segments of men – broken into small fragments’.[3] Morris followed Pugin and Ruskin in ascribing a moral value to the applied arts. He set an agenda for the Arts and Crafts movement, championing the applied arts and crafts as being equal to fine arts, in the medieval tradition, and seeing art and design as a social salve.

Installation view of Rob Ryan's Papercut "Let People Live! Cap Rents in London" hung on the stairwell of the William Morris Gallery, Lloyd Park, Walthamstow on the occasion of Ryan's 2019 exhibition there. Photograph: Grace Lees-Maffei.

The Morrissian legacy in papercut artist Rob Ryan’s work is seen in the messages communicated through practice which melds art, design and craft. As I’ve said, Morris was Master of the Art Workers’ Guild in 1892, while Ryan is Master for 2024. Although papercuts were not among Morris’s extraordinary creative range, he is described as a printer among several other areas of practice in his AWG listing, and Ryan is a fine art printmaker as well as a papercut artist. Ryan explicitly addresses making in his work thematically and demonstratively through his command of paper cutting and silkscreen printing. Ryan’s 2019 exhibition at Walthamstow’s Morris Gallery, which I wrote about here, tackled housing inequality in London, a political stance appropriate to the setting and to Morris’s social and political concerns about poverty and the place of the artist-designer in society.[4]

In 1851, the year that the vast Great Exhibition spearheaded by Prince Albert and Henry Cole at what became known as the “Crystal Palace” designed by Joseph Paxton, architect of the greenhouses at Chatsworth in Derbyshire, in London’s Hyde Park — HMP Wandsworth was built as one of the largest prisons in Europe. The V&A is part of the Albertopolis cultural quarter on South Kensington’s Exhibition Road, named for the Great Exhibition and leading up to its site in Hyde Park. The South Kensington Museums were developed in part with profits and objects from the Exhibition, with the V&A having its first incarnation as the teaching collection of the South Kensington School of Art. In 2010, around 40 inmates from Wandsworth’s Onslow wing participated in the HMP Wandsworth Quilting Group, led by the social enterprise Fine Cell Work, to produce a contribution to the V&A exhibition ‘Quilts 1700-2010’ curated by Sue Prichard, then curator of contemporary textiles at the museum. The HMP Wandsworth Quilt (top) gives voice to prisoners, and describes their experiences, thoughts and feelings about incarceration, about their prison, and about stitching.

These two creative examples differ in important respects: one is a solo creation, the other is a group effort; one is paper-based, the other is stitched into fabric; one is the output of a professional papercut artist, the other is the result of a project with amateurs. But, each of the outputs foregrounds the process of making by hand within the context of socially-engaged progressive politics. The lecture draws on part of a chapter on Handicrafts that I’ve written for The Hand Book, my current project, which seems from ym vantage point as writer in progress, almost as vast as the Crystal Palace. I hope the members of the Pugin Society will enjoy my lecture for the links it makes across centuries and media.

Pugin Society webpage promoting the 2024 AGM, Lecture and Festive Tea. Web design by Dr Jamie Jacobs.

References[1] AWN Pugin, The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture. London: John Weale, 1841, p. 1, p. 8, p. 28.

[2] Conner, Patrick R. M. 1978. “Pugin and Ruskin.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 41: 344-350, p. 344.

[3] John Ruskin, ‘The Nature of the Gothic’ (1853), The Stones of Venice, vol. 2, The Sea Stories, in The Complete Works of John Ruskin, vol. 10, edited by E.T. Cook and A. Wedderburn, pp. 180-269, London: George Allen, 1904, reproduced in The Design History Reader, ed. Grace Lees-Maffei and Rebecca Houze, pp. 60-64, Oxford: Berg, 2010, (reprinted London: Bloomsbury 2013), p. 63.

[4] ‘Rob Ryan’, William Morris Gallery, Walthamstow, London, 20 October 2018 to 27 January 2019.

December 1, 2024

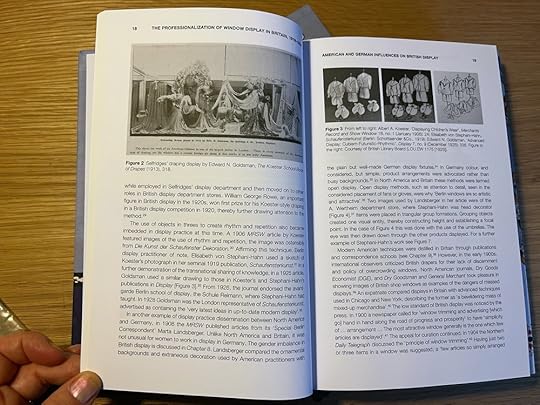

Launching The Professionalisation of Window Display in Britain, 1919-1939

This week, I was delighted to attend a book launch for Dr Kerry Meakin’s new book, The Professionalisation of Window Display in Britain, 1919-1939, part of Bloomsbury’s Cultural Histories of Design book series which I founded and co-edit with Prof Kjetil Fallan (University of Oslo). The launch was hosted by Dr Vanessa Vanden Berghe at Chelsea College of Arts, University of the Arts London, at its elegant site next to Tate Britain by the Thames on Millbank. During the launch, Dr Meakin made clear that her approach to researching the history of window display arose from her own work over several decades as a window display professional. She read from her book, accompanied by a slide show of fascinating images from her book of shop window installations and designs. A panel discussion followed in which Kerry answered questions from Professor Penny Sparke, Dr Vanden Berghe and Dr Harriet Atkinson, before the questions were opened to the floor. The evening closed with a convivial drink, where I was delighted to distribute flyers for the Cultural Histories of Design series, and catch up with our super publisher, Suzie Nash and other guests as well as, chiefly, celebrating Kerry’s book.

Although I felt that having worked closely with the text as a co-series editor I should not have any questions, in fact I had several. As well as being interested in Dr Meakin’s book as series co-editor, I am also interested in her topic as it relates to my own work on the professionalization of interior design. So, I was interested in the relationship between window design and retail design in the stores, and whether the latter was led by the former or vice versa, and whether the latter was undertaken by interior designers and the wider relationship between the professionalisation of interior design and window display. Kerry answered that the window displays she studied were reflected in displays throughout the stores, and that interior designers lack the skills possessed by window display designers. I also asked about whether Dr Meakin considered moving from the archival research that underpinned this book to oral history for a future project, in order to capture the rich professional expertise that she and several of her audience members shared during the discussion. Kerry agreed that an oral history of windows display is urgently needed to capture the history of practice in the 1980s.

Reflecting on Cultural Histories of Design

I conceived the idea for the book series Cultural Histories of Design in 2013 when Prof Fallan and I developed it as a home for design histories which extend their reach into and across the humanities. The intention for the series is that it should seek out, foster and publish rigorous original research on the role and significance of design in society and culture, past and present from a vantage point at the heart of the humanities. It has been successful in this, producing a collection of books which explore design as the most significant manifestation of modern and contemporary culture. Cultural Histories of Design is distinguished by an interdisciplinary approach to design, including, but not limited to, design history, cultural studies, history, art history, business history, history of technology, anthropology, material culture studies, archaeology, geography, sociology, media studies and visual culture studies.

Bloomsbury was an obvious home for this series, not only because it has developed the dominant design list internationally, but also because it has grown its academic coverage in the arts and humanities through acquisitions, for instance, of Berg, Continuum, Fairchild, AVA and I.B. Tauris. The series contract was signed in 2015, and after much work and preparation, Cultural Histories of Design launched in December 2017 with two titles published at the start of 2018: Modern Asian Design by Dr Daniel Huppatz and Norman Bel Geddes: American Design Visionary by Dr Nicolas P Maffei. Later that year, Dr Thomas Cubbin’s Design on the Soviet Critical Design: Senezh Studio and the Communist Surround joined the series.

A second pair of titles, published in 2020, comprised Dr Trond Klevgaard’s The New Typography in Scandinavia: Modernist Design and Print Culture, and Prof Raiford Guins’ Atari Design: Impressions on Coin-Operated Video Game Machines. Klevgaard’s book also extended the existing geographical range of the series of the USA, Asia and Russia, into Scandinavia, providing new knowledge and understanding of how modernism was negotiated in that region. Guins examines video games as emplaced objects, the result of combined efforts in not only game design and interaction design but also product and furniture design, interior design, retail design and even airport design.

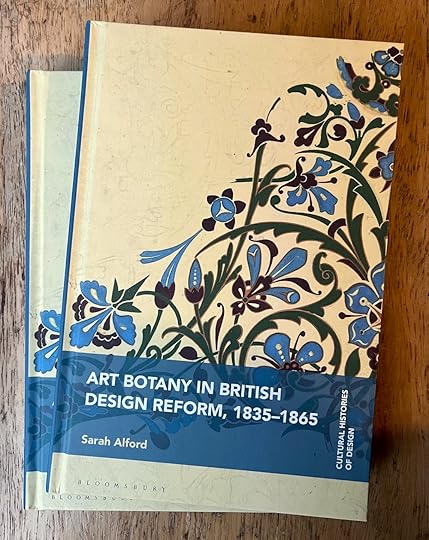

The editorial team noted that the calls for submissions had attracted a varied range of titles, but that we needed to work harder to encourage proposals from women authors. Our efforts have been successful, with the four most recent titles being Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler’s Open Plan: A Design History of the American Office (2021) a timely reflection on the history of proximity in the very spaces that working from home kept distant during the Covid-19 pandemic; Sabine Wieber’s Jugendstil Women and the Making of Modern Design (2023), and 2024’s pair of contributions, Kerry Meakin’s The Professionalization of Window Display in Britain, 1919-1939 and Sarah Alford’s Art Botany in British Design Reform 1835-1865.

Art Botany in British Design Reform, 1835-1865

Sarah Alford’s new book meets the brief for the Cultural Histories of Design series, of engaging design history with the wider arts and humanities, by combining design history and the history of science. Alford looks anew at the history of design in the middle of the nineteenth century (specifically 1835-1865) informed by knowledge and understanding of the development of botanical science, its incorporation into contemporary design philosophies, and popular enthusiasm for botany. Alford traces the ways in which 'art botany' was promoted in new design schools as a disciplined approach to decoration informed by natural science, by leading designers such as Owen Jones and Christopher Dresser among others.

There are several forthcoming titles in the pipeline, about which more here soon. We are open to proposals which features excellent research and we are keen to encourage submissions on any topic which centres design, including for instance decolonizing design, environmental histories of design, gender studies, and histories of digital design. We are proud of the work we, and the authors and the publisher have done with the series, and we are very positive about its future.

November 22, 2024

DHeritage 10th Anniversary Symposium

Last month, the professional doctorate in heritage at the University of Hertfordshire, DHeritage, celebrated its first decade. In celebration, I convened a symposium for current students, graduates, staff across the university, and friends of the programme both internal and external.

DHeritage Foundations and ContextsFollowing a welcome from Dr Stephen Partridge, Dean of the School of Creative Arts, the opening panel ‘DHeritage Foundations and Contexts’ examined the genesis and context of the programme in two pairs of talks. The first two talks examined the development of this innovative programme with recollections from two of the people who built it.

Dr Susan Grey, Director of the Doctoral College reflected on DHeritage as one of a suite of professional doctorates introduced in each School of the University. The first to launch was the EngD (Engineering) in 1999, and the following year, the Doctorate in Management (DMan). There followed professional doctorates in Clinical Psychology, Business Administration, Education (2005), Health Reserch, Medicine, Fine Art and Design (2011) and DHeritage in 2014, then Cyber Security, Public Health, Health and Social Care and Clinical Medicine. 40% of Hertfordshire’s postgraduate research students are registered for a professional doctorate. Professor Owen Davies took up the story with his account of leading the development of DHeritage in the School of Humanities. In 2010, the VC decided to develop the professional doctorates at Hertfordshire and in the same year, the Heritage Hub was founded by Owen and Professor Sarah Lloyd. Consequently, a decision was made to introduce a Heritage doctorate. Owen, Sarah and Dr Alix Green - who was Director of DHeritage in its first semester before I took up the role at the beginning of 2015 - garnered support from a wide range of stakeholders, including research leaders in several other Schools and the library, before the programme launched in 2014.

A Distinctive DegreeDHeritage is distinctive, not to say unique, in several ways.

As a professional doctorate, rather than a traditional PhD, it attracts an international community of practitioners currently working (usually full time) in the heritage field broadly defined including planning, museums, archives, community history and engagement, archaeology, social and cultural sustainability and funding. Applicants must have at least five years’ experience of working in heritage, as well as a master’s degree, and a compelling research proposal which shows the potential to make an original contribution to knowledge.

DHeritage provides a rich, multi-disciplinary academic context for our students’ research into issues and questions thrown up in their professional heritage work. We reflect on and contribute to the latest thinking in a dynamic and ever-changing sector crucial to local and national identities and economies. Supervisory teams are composed according to students’ needs with experts drawn from across the University, working in History, Business and Tourism, Education, Literature, Creative Arts and Design, Architecture, and Urbanism, among other fields.

Our students follow the programme as part of a cohort, supported by bespoke training workshops on core topics in methodology, project development and presentation, and an ever-changing array of thematic workshops which keeps pace with the development of critical thinking in heritage. Workshop topics have included professional ethics, heritage and sustainability, cultural memory, heritage policy, dark and difficult heritage, natural heritage, and LGBTQ+ heritages, to name but a few. DHeritage students and staff benefit from study visits, such as to the (now closed) Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture (MoDA) at the University of Middlesex for a workshop on design and heritage, to Soho, London, in preparation for our workshop on LGBTQ+ heritages and to Chiltern Open Air Museum (COAM). In addition, our university-wide Researcher Development Programme offers a wide range of research skills training and provides opportunities to study alongside research students working in other disciplines.

For their professional doctorates, DHeritage students produce work which will directly impact heritage practice. Students can support their dissertations with an equivalent portfolio that may take any form that demonstrates the thesis including, for example, policy documents, toolkits, documentary films, exhibitions, catalogues, or heritage trails.

The University of Hertfordshire is uniquely well equipped to host DHeritage. Our students draw on the rich research contexts of our Schools, our research cluster Heritage, Cultures and Communities, the University-wide collaborative expertise of our Heritage Hub, our regional UHArts centre, and the Doctoral College. In 2021, we were ranked 10th globally for overall student satisfaction. The University of Hertfordshire’s main campus straddles the A1(M), twenty minutes north of London, UK and benefits from excellent public transport links. DHeritage is offered through distance learning for international students and we are committed to hybrid and online delivery for all, making DHeritage a convenient degree for those outside of the region, and indeed the country, those working full time and/or with significant other responsibilities. We extend our commitment to accessibility with a competitively awarded annual DHeritage bursary, which covers fees for six years and a modest annual study allowance for books, travel, etc.

Change and DevelopmentAt the half-way point in the programme’s development to date, I led DHeritage through a Periodic Review, which is the University’s way of evaluating the currency and usefulness of its programmes in consultation with external industry professionals and colleagues across the institution. In 2019, external assessor Professor Paul Ward (now retired) was very positive about DHeritage:

The DHeritage at the University of Hertfordshire is an innovative and well thought out programme […] from induction through to completion. In particular, the desire for a cross-cohort identity and the methods to instil it among a part-time cohort across various years of the programme is commendable. The workshop materials/assignments and virtual learning environment (Canvas) content was excellent. In each case, there were clear signs of leadership for staff involved, ensuring an admirable ethos and style in the programme, to the benefit of the students.

Ward additionally noted ‘the richness of research strength and the variety of disciplines that are accommodated within the DHeritage's offer’ and concluded that ‘this is an excellent and coherent programme with many innovative features and commendable learning resources to develop heritage professionals as researchers.’ Our second Periodic Review will take place during this academic year and we welcome the opportunity to reflect and benefit from further evaluation of our programme.

DHeritage has of course experienced some changes across its decade of existence:

Workshop delivery has developed to better recognise students as experts in their fields through their professional careers, as well as becoming experts academically as their doctorates progress. Having taught undergraduates and master’s students, alongside some doctoral delivery and supervision, for the two decades prior to taking on the Directorship of DHeritage, this has been a rewarding pedagogical challenge for me.

Our student group has grown steadily to form a rich learning set in which peer interactions are as important as the bespoke workshop training we offer. This networking and peer learning is a crucial dimension of the programme. One challenge is to foster this in online workshops.

Workshops shifted from in person events to wholly online in March 2020 due to the closure of the University in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since 2022/3, we have delivered hybrid workshops to offer students a choice of campus and online participation. The latter is useful for our overseas students and those who cannot travel to Hatfield due to work commitments, access requirements, etc.

Research Contexts for DHeritageThe second pair of talks for the first panel of the symposium were delivered by those leading on elements of the research context which has enabled DHeritage to flourish. Inna Allen and Elizabeth Murton from UH Arts + Culture discussed the ways in which it has contributed to the research culture of the university. UH Arts + Culture collaborates with the university’s researchers and many external creatives:

UH Arts + Culture is the public-facing arts centre of the University of Hertfordshire. Established in 1994 to raise the cultural profile of the University, UH Arts + Culture provides inspirational arts and cultural experiences to students, staff and regional communities. Celebrating its 30th Anniversary this year, the arts centre delivers a relevant, ambitious and innovative cross-arts programme which includes: visual arts exhibitions and projects (campuses + local areas); live arts events, including performances, dance and music (campuses + pop-ups); UH Art Collection of over 500 works, dispersed across campuses; Resident orchestra: de Havilland Philharmonic; outreach + public engagement projects (campuses + local areas).

Inna and Elizabeth shared a video portrait of the past 30 years of UH Arts + Culture:

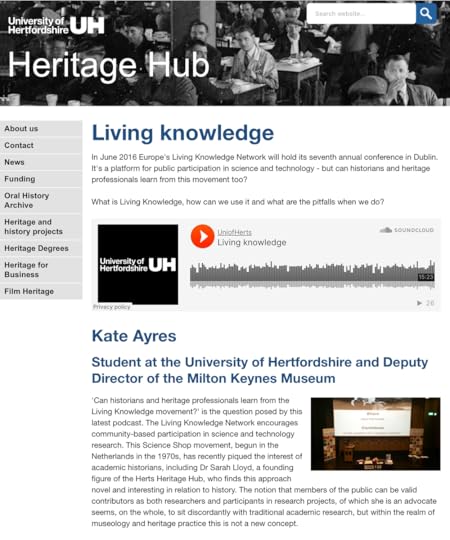

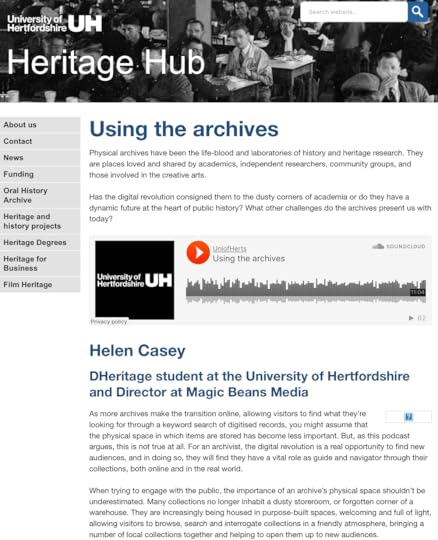

The final talk in the opening panel was given by Professor Katrina Navickas, who leads the Heritage Hub. It was conceived by Prof Owen Davies and Prof Sarah Lloyd as “an organised, unified, outward-facing identity for the University's heritage engagement activities with community groups, heritage institutions and museums, local authorities and businesses”. Engaging with all the Schools of the University, and staff members whose work relates to heritage in various ways, and students, especially those taking the Doctorate of Heritage (DHeritage), the Hub’s activities are all participatory and involve community co-production research in heritage. Katrina highlighted the Hub’s AHRC-funded Everyday Lives in War First World War engagement centre in collaboration with the Universities of Essex, Northampton, Lincoln, Central Lancashire and West of England (2014-2019), which involved working closely with the Heritage Lottery Fund. She also mentioned the current activity centred on an AHRC Impact Acceleration Award and the Oral History Archive, and finally new work in Film Heritage.

DHeritage Doctoral Research: Completed and Completing

L-R: Grace Lees-Maffei, Nick Thomas, Sarah-Jane Harknett, Sarah Fitzpatrick, Helen Casey, Sarah Buckingham

Panel 2 showcased original and cutting-edge research from some of our graduates and students nearing completion. Dr Helen Casey was a member of the first DHeritage cohort and experienced its development as she progressed with her academic research. She was attracted to the programme because her twenty years of experience in the field was respected. Dr Casey’s candid talk about ‘How Not to Do a Doctorate’ shared what she had learned about academic writing as distinct from her background in journalism, as well as independent study, self-belief etc. Sarah Buckingham chose a research topic based on what she would ideally like to have been working on in the field. In her talk, ‘Should historic sites or places be reconstructed after substantial loss or damage brought about by conflict? And if so, how?’ she noted that ‘in reflexive practice, the subject matter is everywhere!’ There are practical challenges too: Sarah has changed jobs four times during the course of her doctoral study. Like Helen, Sarah highlighted the process of adopting an academic writing style as key, and time management too.

Janine Marriott , who works in Public Engagement at Arnos Vale Cemetery in Bristol (and is (shown here conducting a tour) was often asked for advice about doing public engagement from other historic cemeteries. She decided to do a professional doctorate on the topic as a result of the discussions she had with wider colleagues. Janine discussed heuristic research as embedded with an insider perspective, and the context of death studies. Janine has been an energetic conference participant; giving conference papers has been a great way to test ideas, as has writing book chapters along the way. Janine’s research has built connections and community. Sarah Fitzpatrick gave a talk titled ‘The Museum Trustee: exploring theory, policy and practice in governance at small museums’’. In discussing ‘The impact of museum displays: improving the evaluation of permanent exhibitions,’ Sarah-Jane Harknett explained that the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology has 100,000 visitors each year, but that the evaluation activity concerning their responses tends to ignore the permanent displays (shown here in a gallery of photographs I took in October 2024) .

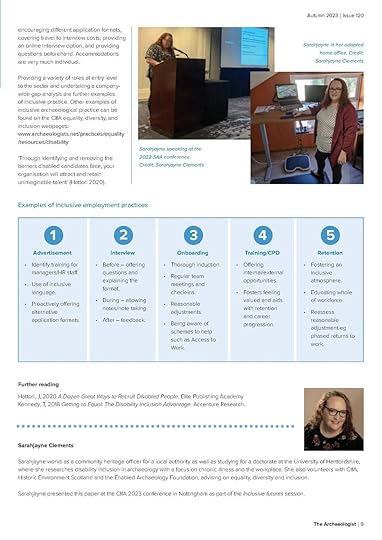

Panel 3, the second of two student panels, introduced work from students in the first half of their degrees, including one new entrant. Zana Lloncari Osmani discussed ‘Janjeva’s Heritage: Balancing Inclusion in Heritage-Led Regeneration’; Christine Kimbriel engaged the audience with props in her talk ‘What's in the wielding of a swabstick? On the tacit knowledge of the conservator’. Claire Slack painted a vivid picture of her research methods and fieldwork including ‘Following Druids to the Pub’. Sarahjayne Clements introduced her work on ‘Breaking Down Barriers: Disability inclusion in Archaeology & Heritage’. Finally, one of our newest students, Ian Sudlow-McKay, introduced his research into ‘Heritage Collections in Higher Education - Purpose, function and future’.

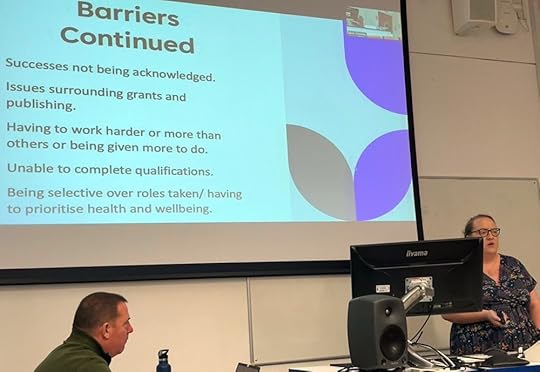

Sarahjayne Clements examining barriers to professional practice for disabled archaeologists

We have very much enjoyed celebrating the successes of our students, including our graduates, and the contributions all of the students have made to knowledge and understanding of the field through publications, podcasts, national radio appearances, various symposia, including one sponsored by the Design History Society, the Design Museum and UH, and conference contributions, from the international Association of Critical Heritage Studies conference, to the convening and hosting of a student-led conference in 2023. I was delighted to include DHeritage student Barbara Wood’s work in a co-edited book, which - prompted by my experience as a design historian directing DHeritage - explores the relationship between design and heritage, as I discussed in the following panel. I couldn’t be prouder of the the students. It was such a pleasure listening to them talk about their heritage studies research.

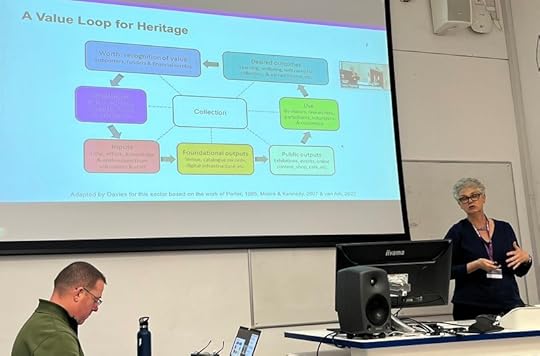

DHeritage Staff Research: Disciplinary Dialogues and ImpactColleagues from several Schools contribute very generously to the programme. Two of the afternoon panels provided snapshots of their heritage research. In the first of these, three staff members explored their heritage research in dialogue with the fields of design history, art history and urbanism respectively. I began with an account of co-edting a book, Design and Heritage, with Professor Rebecca Houze (Northern Illinois University, USA), and particularly the way in which we innovated by bringing together ‘Design (History) and Heritage (Studies)’, as the title of my introduction to the book puts it. Next. Associate Professor Dr Steven Adams shared his work on ‘Art History, Trauma and the Reconstruction of Heritage’. Finally, Associate Professor Dr Susan Parham discussed her work ‘Exploring heritage from an urbanism perspective’. The second staff panel reflected the programme's strengths in research impact, by offering snapshots of work in heritage which engages with wider communities. Professor Jonathan Morris discussed his research and collaborations in researching Global Coffee Heritage. Dr Susan Davies’s talk proposing a ‘value loop’ for heritage organisations had the remarkable title ‘A Bushel of Beauty and an Acre of Awe: Performance Indicators in Heritage’. Having profiled the Heritage Hub in the morning, Professor Katrina Navickas discussed her own heritage research. Finally, Anna Hammerin shared her work funded by an Impact Acceleration Award, including a very moving clip about community co-production in her film about the Swedish women’s potato revolution of 1917.

Dr Sue Davies proposes a ‘value loop’ for heritage.

DHeritage, the Next Ten YearsThe symposium was capped with a plenary discussion in which participants were invited to respond to the day’s discussions and to forecast what might be on the horizon for DHeritage, and heritage more broadly in the next decade. In-person attendees moved to the University’s Chapman Lounge for a farewell glass of wine and cheeseboards. The mood really was celebratory, even after a long, intense day of sharing, talking and listening.

Thank you to Nick Thomas, event manager for this symposium, who made it possible with his expertise, practicality, organisational skills and wonderfully positive disposition. Thank you to the School of Creative Arts, our Dean, Dr Stephen Partridge, and Associate Dean Research Associate Professor Dr Steven Adams for their support of this event, and for delicious catering from our Hospitality team. I am grateful to the wider University, the Doctoral College, the Research Office, the School of Creative Arts, the Heritage Hub, UH Arts + Culture, and the Heritage, Cultures and Communities research cluster, for providing a research context in which the programme can flourish. Thank you to all the students who are at the core of all of the programme’s activities. I am grateful to my colleagues who contribute to the programme in so many enriching ways and really make it possible. We owe a great debt to external friends of the programme who join us to generously inform our curriculum, and to the hosts at various places where we have enjoyed study visits. Finally, thank you to all of symposium attendees, online and in person for their attention and questions.

This academic year, the DHeritage will undergo its second five-year Periodic Review, and will be part of a university-wide review of the professional doctorates. Both of these reviews are well timed to fit with and continue the process of reflection that underpinned the 10th Anniversary Symposium.

August 30, 2024

Exciting Review of Design and Heritage

This morning I was delighted to read a review in the journal Design and Culture of Design and Heritage, which I co-edited with Prof Rebecca Houze. The review is by Anmol Shrivastava, Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at Illinois State University. A non-binary designer and educator from India, Shrivastava works on ‘cultural and social awareness, with the aim of broadening the scope of design beyond traditional Western norms.’ Shrivastava’s inclusive research methodology involves ‘collaboration, particularly with craftspeople’. This reviewer is kind enough to praise Design and Heritage:

SequencesThis scholarly work will captivate design researchers, anthropologists, educators, and graduate students eager to delve deeper into diverse heritage narratives, as well as topics such as colonization, identity, and culture. […] Together, the essays speak to a newly acknowledged “shared ancestry” (6) between design (history) and heritage (studies), sparking important analysis of the political and ethical dimensions of heritage practices in global spaces and communities.

I must admit to a wry smile when Shrivastava suggested that ‘the volume might have benefitted from providing readers with alternative ways of knitting the diverse material together’ because I devised no fewer than five potential sequences for the book’s chapters, as follows:

Thematic - with sections on Definitions and Concepts of Design and Heritage; Design and Tangible/Intangible Cultural Heritage; and The Politics of Design and Heritage.

Chronological - the book spans two hundred years, from Barbara Wood’s account of the UK National Trust’s Wellington Monument (1815) to Peder Valle’s analysis of a twenty-first century legal challenge involving a ceramic manufacturers in Norway and Denmark.

Geographical - with chapters grouped into three sections addressing Europe, the Americas, and Asia, Australisia and Africa respectively. Read more about this approach below.

Place, Spaces and Things - divided into two sections, examining Places and Spaces in the first and Things in the second.

Design Field - beginning with Monuments and Memorials; then Landscape, Place and Visitor Experience; Craft and Industrial Design; Textiles and Dress; and finally, Graphic Design Information Design and Typography.

We opted for the latter arrangement in order to clarify design and its sub-fields for the heritage studies readership which formed an important part of the target market for the book. Feedback we received on the proposal and manuscript let Rebecca and I know that we should be careful to avoid assuming the readership is conversant with design, as we might do for our other publications.

In fact, the various sequences for the material listed above are discussed in detail in a dedicated section, ‘Chronology and Geography’ pp. 13-15 of my Introduction, but Shrivastava makes the excellent suggestion of inserting ‘a map to put subject matter in spatial relation or a visual timeline to temporally situate it’. Such diagrammatic apparatus could certainly have made the points more vividly.

Geographical and Cultural DiversityThe review begins with praise for the fact that ‘The book includes viewpoints from a range of geographic, cultural, and social contexts. While contributors are predominantly from Europe and North America, some are based in Asia (India, Honk Kong, and Burma), Africa (South Africa), South America (Brazil), and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand).’ In this it follows my previous book, Designing Worlds: National Design Histories in an Age of Globalization, co-edited with Kjetil Fallan (Berghahn 2016, 2018) available Open Access here. That book is arranged geographically, taking readers on an international tour, beginning with three chapters about Africa, by African authors, before moving to New Zealand, Japan, India, Lebanon, Czechia, Denmark, Norway and Sweden, the UK, USA, Jamaica, Latin America and Brazil.

Shrivastava judges that athough it is ‘still predominantly Eurocentric’, Design and Heritage ‘excels in presenting unacknowledged perspectives on colonization, from the perspective of both the colonizers and the colonized, and its relationship to heritage.’ They cite chapters by Carmín Berchoilly, and Mandy Nicholson and David S. Jones as examples. Chapters by Vanessa Nicholson and Rebecca Houze are mentioned by the reviewer for the ways in which they ‘critique projects with heritage status and reveal their bloodstained colonial origins’, exemplifying how ‘each case study offers distinct perspectives on identity and belonging’. Also mentioned is Suchitra Balasubrahmanyan’s chapter on the India–Pakistan border and identity, for its ‘nuanced analyses of re-choreographed colonial military rituals, newly invented public events, and curated tours, demonstrating how the designed experience of these “border ceremonies” (53) give relevance to the past in the present.’

I am heartened by Shrivastava’s sensitive summary of the book, and by their conclusion that:

Design and Heritage serves as a solid foundation for fostering more geographically and culturally diverse studies of critical heritage and design history. Each essay challenges the reader to question the political and social implications of design in new and meaningful ways, reflecting on who designs our heritage (objects and experiences) and for whom, as well as whose narratives are used to create national identities. Design and heritage are inherently political; history shows that both can be used to cultivate respect for cultural and social diversity, foster exclusion and misrepresentation, or promote political agendas that lead to ethnic cleansing. This book connects these ideas, highlighting the serious implications of practices of design and heritage that aspire towards creating equitable futures or perpetuate contemporary versions of societal horrors like neocolonization and classism.

Read Shrivastava’s review in Design and Culture here. Read more about the book on my blog here, and the project which produced it here.

May 23, 2024

New Review of Illustration and Heritage

Readers of this blog will be aware that my book Design and Heritage: The Construction of Identity and Belonging, co-edited with Rebecca Houze, was published in 2021 by Routledge in its Key issues in Cultural Heritage series. If not, you can read more about its development on the project page and in this blog post on the book’s publication, and read a preview on the book page and more on design and heritage here. I have been pleased and interested to see the publication of two related books by Bloomsbury.

Craft and HeritageFirstly, in the same year that Design and Heritage appeared, so did Craft and Heritage, edited by Susan Surette and Elaine Cheasley Paterson who both work at Concordia University in Canada (Bloomsbury 2021). This collection of 19 essays considers ‘how heritage and craft institutions, policies, practices and audiences encounter the constraints and opportunities of production, recognition and exhibition.’ The opening section explores ‘citizenship and identity, section two sustainability and section three dynamic craft in cultural institutions’.

Based on my experience as Book Reviews Editor for the Journal of Design History (2002-6), I expected — and hoped — to see joint reviews of Design and Heritage and Craft and Heritage appear in the journal literature, but sadly this has not happened.

I am grateful that the JDH did publish a very positive review of Design and Heritage by Gabriele Mentges in which the reviewer concludes that:

All of the contributions in this volume are extremely informative and instructive, both in content and at the conceptual level, because of their thorough interrogation of the respective historical context. They thus provide an in-depth insight into the history and genesis of design as part of heritage issues. For design and heritage researchers, this volume is essential reading. For others, it provides an exciting introduction to the subject.

Mentges does mention one related title in the review — Stefan Willer, Sigrid Weigel, and Bernhard Jussen (eds.). Erbe. Übertragungskonzepte zwischen Natur und Kultur. (Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag, 2013) — but not Craft and Heritage.

Illustration and HeritageThree years after both Design and Heritage and Craft and Heritage appeared, this year Rachel Emily Taylor’s Illustration and Heritage was published by Bloomsbury. According to the book’s blurb:

Rachel Emily Taylor uses her own work and other illustrators' projects as case studies to explore how the making of creative work – through the exploration of archival material and experimental fieldwork – is an important investigative process and engagement strategy when working with heritage.

Out of interest, I have reviewed this title for the International Journal of Heritage Studies. Read my review here or access a free pdf here (fifty are available so apologies in advance if you follow this link and they have run out). I note of the book’s structure that it ‘begins with a brief introduction and a more substantial first chapter, bringing together illustration and heritage. The remaining three chapters examine illustration and historical voices, collections, and landscapes, respectively. The text closes with a conclusion, interview glossary (short biographies of Taylor’s interviewees), bibliography and index.’ I then explore the chapter content before concluding that: ‘Illustration and Heritage will interest and inform those curious about the role and capacity of illustrators in heritage contexts, and the ways in which heritage inspires and stimulates illustration practice. I hope, with Taylor, that her book will prompt new projects and collaborations between these complex, immensely rich and related areas of cultural endeavour.’

Comparative ContextPerhaps too many years have elapsed for there to be a joint review of Design and Heritage and/or Craft and Heritage with Illustration and Heritage or a review essay of all three, but I remain interested in this. While I cannot — obviously! — write such a review, I do plan to convene a workshop in future for the research students enrolled on the Professional Doctorate in Heritage (DHeritage) programme I direct at the University of Hertfordshire which addresses all three books together. I am sure they will provide food for thought and a rich comparative experience and I look forward to hearing what the students think.

April 25, 2024

HARVEST at the Three Rivers Museum

Much as I love my work, some days are more fun than others. I had fun last week, when I left my office to jump on a minibus with my colleague on the Professional Doctorate in Heritage (DHeritage) Dr Sue Davies, Dr Derek Ong and a group of their Hertfordshire Business School (HBS) students, to travel to Three Rivers Museum in Rickmansworth for the launch workshop of Sue and Derek’s HARVEST project.

Front façade, c. 1740, Three Rivers Museum, Rickmansworth.

Three Rivers MuseumThe volunteer-run museum was founded in 1987 in its current premises of Basing House in the town. Architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner describes Basing House as ‘a red brick house with a five-bay front range of c. 1740 extended to left and right in the late C19, and C17 timber-framed parts to the rear. It was the home of William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania, 1672-7’.* A plaque by the front door shown in the photo, top, details the Penn connection. Three Rivers District Council occupied Basing House from 1930 until 1991. The museum, and the District Council, are named after the rivers Colne, Gade and Chess. Pevsner describes Rickmansworth as follows:

The area immediately south of the town is a patchwork of lakes (former gravel pits), bisected by the Grand Union Canal. Although the Watford and Rickmansworth Railway had opened in 1862 (line to Rickmansworth closed in 1967), it was the Metropolitan Railway (now London Underground) that helped form the character of the modern town; the station opened in 1887 and enabled easy commuting to the City. The result was a great deal of new housing north and west of the old centre, including some characteristic Metroland estates.*

The Chairman at the Three Rivers Museum Trust, Fabian Hiscock, is a friend of DHeritage since he completed a Masters by Research in the History department and attended History Department conferences with DHeritage students at Cumberland Lodge, Windsor Great Park. We visited the museum for the launch of Sue and Derek’s project with Fabian called Hertfordshire Archival Research into Victorian Enterprise for a Sustainable Tomorrow (HARVEST).

HARVESTThe HARVEST project is funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) via the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Economic & Social Research Council (ESRC)’s Impact Accelerator Account (IAA). More than £1.7m was awarded to the University of Hertfordshire to accelerate the impact of the University’s world-leading research. Read more here.

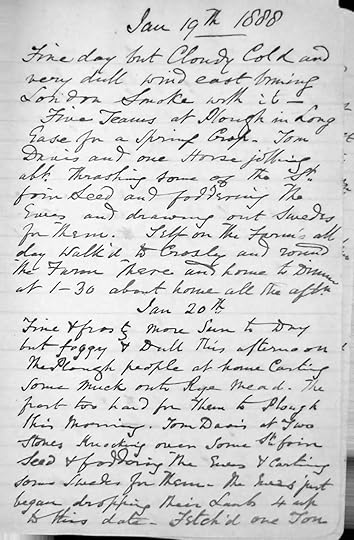

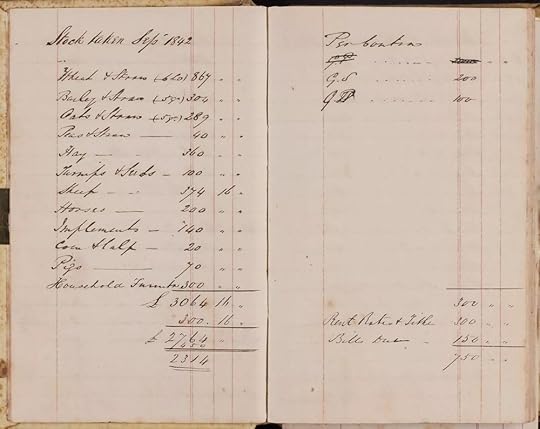

HARVEST centres on the detailed diaries and financial records of south-west Hertfordshire farmer John White (1813–1904) held at the Three Rivers Museum. White farmed Parsonage Farm for sixty years from 1839, and kept his diary for fifty years from his marriage in 1841 to 1896. White still wrote his diary when he was away from his farm, based on information provided by his foreman. He stopped writing his diary when his wife died. Volunteers at the Museum are digitising these holdings, and transcribing the archival materials to make them easier and quicker to read. Volunteer Pauline Szelewski has put the financial records into a spreadsheet for the HBS students to analyse. The core questions underpinning the project are how might White’s diaries and financial records evidence the farming and management practices that enabled him succeed during a time of terrible challenges in farming, and what can we learn from this which might be useful in ensuring sustainable practices today. The images below of White and his wife Sophie, his diary and his financial records, are published on the Three Rivers Museum website gallery.

HARVEST Launch Workshop

Following an introduction by Dr Davies, the programme combined talks from Dr Julie Moore about Hertfordshire agriculture and Fabian Hiscock about the diaries, framed by two interactive sessions led by Dr Derek Ong.

Drawing on her University of Hertfordshire doctoral dissertation ‘The Impact of Agricultural Depression and Land Ownership Change on the County of Hertfordshire, c.1870-1914’, Dr Moore made clear that farming was undergoing tremendous change in the nineteenth century. In 1846, the Corn Laws, which kept farmer’s prices buoyant but were unpopular with a hungry mass population, had been repealed. The development of fertilisers, new strains of wheat, the use of steam engines for threshing, all required farmers to respond in an agile way in order to ensure the survival and competitiveness of their businesses. A swathe of extremely bad weather across the seasons from 1874 to 1895 put many farmers out of business resulting in a national agricultural crisis. John White’s diary entries start with a weather report. In 1879, the US market opened up, bringing wheat imports into the UK to the extent that 80% of wheat here was imported so only one loaf in five was made from British-grown wheat. In 1880, farm bankruptcies peaked as farmers had not been able to sustain five years of losses.

But the period in which White farmed also included the arrival of the railway and resultant expansion of the town. Julie explained that south Hertfordshire farmers whose crops and dairy produce could be quickly and cheaply transported to London on the train were less vulnerable to threats from the weather and market fluctuations, because they had a ready, and massively expanding, buying public for their products. The stables of London also assisted the in the farming effort by providing the large amounts of manure needed to farm crops successfully. For White the railway was a mixed blessing: the Metropolitan Railway crossed his land, so his rent was reduced, and he was able to use the railway to visit London. However, it also brought day-trippers to his farm, trampling his crops.

Another key to sustainable farming at this time might be found in White’s records. The situation was so difficult that the farmer of one of Hertfordshire’s largest farms did not keep financial records because he did not want to know how bad things were. While some farmers might be accused of poor record keeping, White was exceptional for the detail and longevity of his records and this is likely to have assisted in the survival of his business and in the livelihood of his employees, whose wellbeing concerned him greatly. In the 1872 census, White was recorded as farming 300 acres with 14 men, 4 boys and some casual staff workers. Unlike the ‘dirty boot’ farmers who typically worked on smallholdings and lacked capital, White was a ‘clean boot’ farmer, who rode his horse around his farm organising and supervising the work of his labourers.

Agricultural Interest

Julie explained the concept of ‘agricultural interest’ as extending beyond the financial bottom line into an, albeit idealised, sense of mutual dependence and shared responsibility:

The landowner, such as Lord Cecil at Hatfield, and Lytton at Knebworth, bore the capital expenditure needed to develop farming, and maintain the buildings. Dairy farming is resilient in terms of market competition but it requires capital investment in the provision of milking parlours which not all landowners would have wanted to provide. Larger landowners would employ an agent to manage their multiple farms, while others were more hands-on, for instance insisting farmers grew specific crops. Some landowners had made their fortunes in the professions and on moving to the country they romanticised the paternalism of the landowner.

The farmer paid for his stock, animals and feed. After World War I, there was a shift to owner occupiers who combined the responsibilities previously attributed to landowners and farmers.

The labourer, whether more or less skilled, could experience either a reliable income or uncertain casual labour. They were better paid according to how close they were to London, because the city offered a range of jobs that a labourer might take over farming the land. John White had a reputation for fair dealing with his labourers who lived in with him and his family at Parsonage Farm.

Contractors moved from farm to farm with their traction engines and threshing machines. In 1879, Mr Clark brought his machinery to John White’s farm.

In that year, White was growing oats, wheat, barley, turnips and swedes and kept animals for market, so he had a monthly income year-round. Hertfordshire farmers grew crops such as straw plait for the hat industry in Luton and for the local paper industry. The difficulties sketched above led in some cases to what was called ‘low farming’, characterised by farmers keeping their farms just about productive but poorly maintained, which elicited complaints in the press.

Learning from the PastThe programme for the launch made clear the team’s commitment to promoting the power of historic collections to teach us about the past, and the present. In addition, the HARVEST project demonstrates the benefits of venturing off campus, to create non-academic impact in a co—produced project.

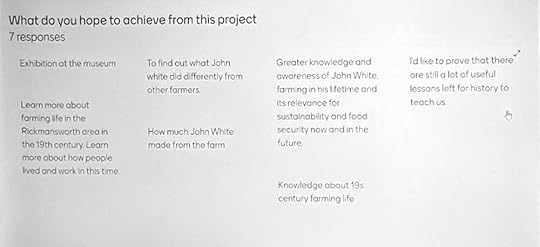

Some responses to Dr Derek Ong’s interactive session with workshop participants identifying their hopes for the project.

In between the launch sessions, a break for tea, biscuits and delicious homemake flapjack saw me sitting on a bench with DHeritage student Sarah Fitzpatrick catching rays in the museum’s suntrap courtyard and planning another off-campus excursion for next month, our DHeritage study visit to Chiltern Open Air Museum (COAM) to examine it’s approach to wellbeing.

Sincere thanks to Sue for inviting me and the DHeritage team to the HARVEST launch, and to Derek, Fabian and Julie for their contributions to the afternoon’s programme. Best of luck to them and all of the students, and I look forward very much to hearing more about it at the next workshops taking place on 12th June and 26th September.

*James Bettley, Nikolaus Pevsner and Bridget Cherry. 2019/1953. Hertfordshire, The Buildings of England, London: Yale University Press, p. 440, p. 436.

March 21, 2024

Remembering Charlotte Benton (1944-2024)

Last month I attended a memorial celebration for design historian Charlotte Benton who died on 22nd January 2024. Charlotte was a pivotal design historian who worked in several ways to advance the field.

Charlotte’s Memorial Celebration at Murray Edwards College, CambridgeThe memorial celebration was hosted on 9th February 2024 by Professor Emeritus Tim Benton at Murray Edwards College, Cambridge University, with the support of Mary Ann Steane, Director of Studies in Architecture there. The college was founded in 1954 as New Hall, to tackle the fact that Cambridge had one of the lowest rates of women students in the UK. The land was donated by Charles Darwin’s descendants. The main building was designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, and built by W. C. French Ltd., who constructed the first motorway bridges on the M1. It opened in 1964. The college was renamed following a donation of £30 million by alumna Dr Ros Edwards and her husband Steve, in their honour and for the college’s first president Dame Rosemary Murray. On the day of my visit, in February, the grounds were scattered with flowering bulbs including some very happy hellebores.

View fullsize

View fullsize

Two views of the main building, Murray Edwards College, Cambridge University, designed by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon (1964). Photographs by Grace Lees-Maffei, 9th February 2024.

At the memorial, Tim showed a beautiful carousel of photographs of Charlotte throughout her life (including the portraits which top and tail this post), and he gave a PowerPoint presentation about her life and work. We listened to a ‘radio vision’ recording of her voice for the Open University course A305, and a recording of her interviewing another Charlotte, Charlotte Perriand, in French. As the current Chair of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Design History, I said a few words about Charlotte’s generosity as an editor, and remembered spending a charming evening at her house in Cambridge with my husband, Nic Maffei. Nic had recently written a chapter about American Art Deco and streamlining for the book Charlotte and Tim edited with Ghislaine Wood, Art Deco 1910-1939, to accompany a blockbuster V&A exhibition. Ghislaine also gave a speech at the memorial, about curating the V&A’s Art Deco exhibition with Charlotte and Tim, and Charlotte’s kindness to her. Finally, Stephen Bayley remembered Charlotte as a friend and colleague during the early days of the Open University course. All of us attested to Charlotte’s expertise and generosity.

Open University Course A305A305 was a landmark in the development of design history. Open University films aired on the BBC, so anyone could watch them. Some of the A305 films are available as a playlist made available by the Canadian Centre for Architecture, which in 2018 hosted an exhibition about the course called ‘The University Is Now on Air: Broadcasting Modern Architecture’, and which also published some related oral history interviews. A305 extended beyond film to textbooks, slide collections and audio recordings.

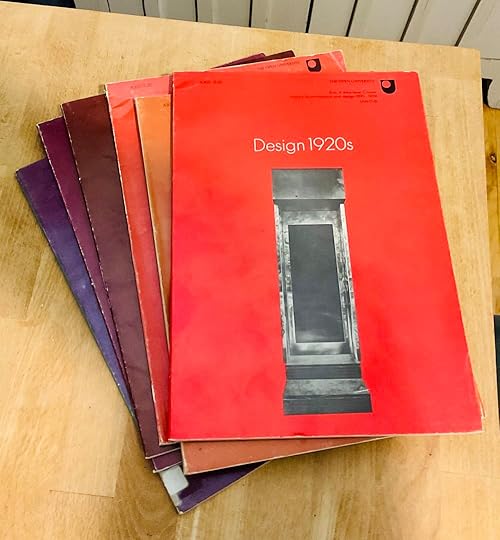

Some of the Open University course books for A305 in my collection, including Design 1920s prepared by Tim Benton, Charlotte Benton and Aaron Scharf (1975). Photograph by Grace Lees-Maffei, 21st March 2024.

My knowledge of the A305 course is based from course books I have collected and read, and from a conference commemorating the course ‘40 Years On: The Domain of Design History Looking Back Looking Forward’ which I attended on 22nd May 2015, at the Open University campus in Milton Keynes. Charlotte was involved in the organisation of the conference, advising Professor (now Emerita) Elizabeth McKellar. I was struck by the enthusiasm and even fondness for A305 displayed by the design historians assembled there, many of whom - like me - had neither attended nor worked at the Open University, but had read the course books, used them in teaching, watched the films and learned a lot in the process.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

My snapshots from the conference ‘40 Years On: The Domain of Design History Looking Back Looking Forward’: tulips welcome visitors to the Open University campus, Church Lane, Milton Keynes; Prof Elizabeth McKellar opens the conference with Profs Penny Sparke and Christopher Breward in the audience; courtyard topiary in two colours in the shape of the Open University logo. 22nd May 2015.

Attendees of the memorial celebration at Murray Edwards College were given a pamphlet, prepared by Tim Benton, about Charlotte’s life and work. I was happy to write a text remembering Charlotte’s immense contribution to the development and first decade of the Journal of Design History, as follows.

Charlotte Benton and the Journal of Design HistoryFrom 1984-7, Charlotte was a member of the Design History Society sub-committee tasked with setting up what became the Journal of Design History. From 1987, she was a member of both the DHS Executive Committee and the first Editorial Board of the JDH. As Production Editor for the journal’s first decade, Charlotte supported hundreds of authors in facing what she vividly described as ‘the inexorable guillotine of the publisher's deadline’.[i] They included Christopher Breward, who remembered that Charlotte was assigned editor for his ‘first and only article in the JDH - a truly formative experience! One I'm very grateful for.’[ii]

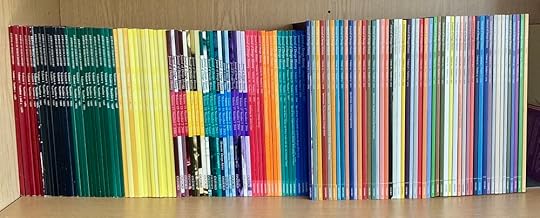

My near-complete run of the Journal of Design History, with the first ten volumes produced by Charlotte Benton. Photograph by Grace Lees-Maffei, 8th June 2023.

Among Charlotte’s publications is the aforementioned monumental co-edited book, Art Deco, 1910-1939, published by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2003 to accompany its exhibition on Art Deco,[iii] and a range of contributions to the JDH. These include reports on events such as a forum on reproduction fees, regular reviews, resources,[iv] and an obituary for fellow JDH Editorial Board member and Open University colleague in the creation of landmark course A305, Anthony Coulson.[v] Charlotte’s research articles for the JDH are:

‘Le Corbusier: Furniture and the Interior’,[vi]

A two-part article about Daniel Libeskind’s unbuilt extension for the V&A,[vii]

‘From Tubular Steel to Bamboo: Charlotte Perriand, the Migrating Chaise-longue and Japan’.[viii]

I saw a bamboo chaise-longue, of the kind analysed by Charlotte Benton, on display in an enormous retrospective exhibition, ‘Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World’ at Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris, which ran from 2nd October 2019 to 24th February 2020. Photograph by Grace Lees-Maffei, 1st November 2019.

One function of academic journals is, as the word ‘journal’ implies, to serve as a record of current knowledge and awareness in a field, but it is also important that the journal editors catalyse the research agenda. Charlotte’s 1988 Editorial for the Journal’s first special issue, on German design, called for:

‘systematic examination and analysis of the careers of individual designers, the history of institutions (schools of art and design, museums, professional groups), and of particular sectors in which design plays a significant part (such as the automobile, furniture, and printing industries) during the period 1933-45.’[ix]